Summary

As stated at the 1996 Consensus Conference at Babson College, a (maxillary) sinus lift is a “safe and predictable” procedure for increasing alveolar bone height in the postero-superior alveolar regions in order to allow oral rehabilitation and restore masticatory function by means of the insertion of a dental implant even in the case of an atrophic maxilla. However, the procedure has a well-known impact on the delicate homeostasis of the maxillary sinus: the concomitant presence of systemic, naso-sinusal or maxillary sinus disease may favour the development of post-operative complications (particularly maxillary rhino-sinusitis), which can compromise a good surgical outcome. On the basis of these considerations, the management of sinus lift candidates should include the careful identification of any situations contraindicating the procedure and, if naso-sinusal disease is suspected, a clinical assessment by an ear, nose and throat specialist, which should include nasal endoscopy and, if necessary, a computed tomography scan of the maxillo-facial district, particularly the ostio-meatal complex. This first preventive-diagnostic step should be dedicated to detect presumably irreversible and potentially reversible contraindications to a sinus lift, whereas the second (preventive-therapeutic) step is aimed at correcting (mainly with the aid of endoscopic surgery) such potentially reversible ear, nose and throat contraindications as middle-meatal anatomical structural impairments, phlogistic-infective diseases and benign naso-sinusal neoplasms the removal of which achieves naso-sinusal homeostasis recovery, in order to restore the physiological drainage and ventilation of the maxillary sinus. The third (diagnostic-therapeutic) step is only required if mainly infective and sinusal complications arise after sinus lift surgery, and is aimed at ensuring early diagnosis and prompt treatment of maxillary rhino-sinusitis in order to avoid, if possible, implant loss and, in particular, the related major complications. The purpose of this report is to describe these three steps in detail within the context of a multidisciplinary management of sinus lift in which otorhinolaryngological factors may be the key to a successful outcome.

Keywords: Paranasal sinus, Sinus surgery, Sinus lift, Functional endoscopic sinus surgery, Rhino-sinusitis, ENT contraindications

Riassunto

Il rialzo del seno (mascellare), attualmente, rappresenta una tecnica diffusa e di successo per ottenere un incremento dell’altezza dell’osso alveolare nei settori postero-superiori, così da permettere la riabilitazione orale con il ripristino della funzionalità masticatoria, tramite l’apposizione di impianti dentari, anche in presenza di atrofia mascellare. Tuttavia questa procedura esercita un ben noto impatto sulla delicata omeostasi del seno mascellare e la concomitante presenza di patologie sistemiche, naso-sinusali o di processi disventilatori a carico del seno mascellare può favorire la comparsa di complicanze post-operatorie, tra cui, prima fra tutte, la rinosinusite mascellare, con possibile compromissione del buon esito della procedura. Sulla base di questa considerazione la gestione del paziente candidato al rialzo del seno dovrebbe includere l’accurata identificazione di quelle situazioni che sono state indicate come potenziali controindicazioni alla procedura e, nel sospetto di una patologia rinosinusale, una valutazione otorinolaringoiatrica comprensiva di endoscopia nasale, oltre, se indicata, l’esecuzione di una tomografia computerizzata del distretto maxillo-facciale con acquisizione del complesso ostio-meatale. Ciò si verifica durante un momento preventivo-diagnostico (primo momento), grazie al quale vengono identificate, in campo otorinolaringoiatrico, le controindicazioni presumibilmente irreversibili e potenzialmente reversibili all’esecuzione del rialzo del seno. Successivamente, il momento preventivo-terapeutico (secondo momento) prevede, per lo più attraverso il trattamento chirurgico endoscopico, la risoluzione delle controindicazioni otorinolaringoiatriche potenzialmente reversibili, quali alterazioni anatomico-strutturali della regione medio-metale, processi infettivo-flogistici e neoplasie benigne del distretto rino-sinusale la cui rimozione permetta il ritorno all’omeostasi naso-sinusale, così da ripristinare il fisiologico drenaggio e la ventilazione del seno mascellare. L’ultima situazione nella quale è richiesto il coinvolgimento dello specialista otorinolaringoiatra riguarda la gestione delle complicanze iatrogene fra cui, prima fra tutte, la rinosinusite mascellare e si esplica nel momento diagnostico-terapeutico (terzo momento). Esso è finalizzato ad ottenere una precoce diagnosi e ad instaurare un sollecito trattamento della rinosinusite mascellare, così da scongiurare, quando possibile, la perdita degli impianti e soprattutto lo sviluppo delle complicanze sinusitiche più gravi. Il presente lavoro si sofferma sui tre momenti, all’interno della gestione multidisciplinare del rialzo del seno, in cui il ruolo dello specialista in otorinolaringoiatria si rivela veramente determinante per il successo chirurgico della procedura.

Introduction

The use of dental implants is now an extremely widespread and highly successful means of ensuring oral rehabilitation. Over the last few years, these have been employed for the upper dental arch, which had, for decades, been considered inviolable by implantologists because of the nearness of the maxillary sinus and the unpleasant complications arising from its surgical assault. In this context, the surgical sinus lift introduced by Boyne and James, in 1980 1, makes rehabilitation of the upper dental arch feasible even in the case of maxillary bone atrophy 2–4 due to increased osteoclastic activity and bone resorption following the inferior expansion of the maxillary sinus after the loss of tooth roots 5. Sinus lifting involves creating a mucoperiosteal pocket over the maxillary floor and beneath the Schneider membrane in which to place graft material (allograft, xenograft, alloplast) capable of promoting bone thickening by inducing osteoinduction and osteoconduction in order to increase alveolar bone height without compromising the inter-alveolar space. On the basis of good surgical outcomes reported in the literature 2–7, which led to sinus lifting being described as an “efficacious procedure” during the Sinus Consensus Conference in 1996 8, there has been a considerable increase in the number of edentulous candidates for this procedure seeking the complete restoration of masticatory function. However, before undertaking a sinus lift, surgeons need to consider its impact on sinus physiology in order to avoid unwelcome complications that may compromise a positive outcome. An ear, nose and throat (ENT) specialist should be a primary figure in the approach to any sinus lift procedure as his/her collaboration will be precious during the various steps necessary to ensure success of surgery:

a first preventive-diagnostic step aimed at excluding any naso-sinusal diseases that may lead to failure of surgery;

a second preventive-therapeutic step aimed at correcting any pathological findings that represent reversible contraindications to a sinus lift;

a third diagnostic-therapeutic step (if necessary) aimed at ensuring the prompt diagnosis and appropriate treatment of any possible sinus lift-related naso-sinusal complications.

The management of candidates for a sinus lift should be shared by a dental surgeon and ENT specialist. Furthermore, the availability of a multidisciplinary surgical team makes it feasible to attempt experimental surgical strategies such as the combined two-steps procedure in which the ENT specialist first restores maxillary sinus ventilation endoscopically by resolving the pathological process or anatomical alteration contraindicating implant surgery, and then (after a period of at least 3-4 weeks) the oral surgeon performs the sinus lift and places the implants. As an expert in naso-sinusal physiology, the ENT specialist should also play a useful role in defining, with the implantologist, a prophylactic regimen for the candidate to sinus lift in order to reduce the risk of complications: stop smoking, avoid dehydration, pollutant inhalation, exposure to low temperature or dry air and assumption of atropine-like drugs are only a few examples of the hygienic rules indicated for the patient. This article will concentrate on the role of an ENT specialist in managing candidates for a sinus lift, and include a brief description of the anatomo-physiology of the maxillary sinus and the effect of sinus elevation on maxillary homeostasis.

Anatomo-physiology of the maxillary sinus

The maxillary sinus is the widest paranasal sinus, pyramidal in shape and varies remarkably in size, although the average in adulthood is: base 35 x 35 millimeters (mm) and height 25 mm 9; its pneumatisation is related to age of the patient and the presence of teeth. The maxillary sinus walls most involved during sinus lift surgery are the mesio-vestibular wall, the inferior wall (or floor) and the medial wall. The first consists of a thin cortical layer containing the neuro-vascular bundle; the second may present septa or ridges; and the third houses the natural ostium antero-superiorly and sometimes (25%) an accessory ostium in the mucosal area called the anterior and posterior fontanelles 10. Maxillary secretions converge into the middle meatus exclusively through the natural ostium. The maxillary ostium is a 7-11 mm long and 2-6 mm wide elliptical opening 11 that does not open directly into the nasal cavity as it is shielded medially by the uncinate process, which represents the medial bony wall of a slit called the infundibulum that extends from its inlet (the hiatus semilunaris) to the maxillary sinus. The inner layer of the maxillary sinus consists of a 0.13-0.5 mm thick mucosal membrane (Schneider’s membrane) upholstered by a multi-stratified and columnar epithelium (100-150 cilia per columnar cell, with a frequency of 1000 beats per minute) that continues into the nasal mucosa and contains basal, columnar and globet cells resting over the basal membrane 10 12 13. Some serous and mucous glands that thicken near the ostial opening are located in the underlying lamina propria. In addition to acting as an immunological barrier, directly exposed to inspired air, the ciliated respiratory epithelium transports, towards the natural ostium of the maxillary sinus, the viscous gel layer 14. The ~2 litres of maxillary secretions per day 9 consist of water (96%), glycoproteins (3-4%), immunoglobulins, lactoferrin, prostaglandins, lysozyme, leukotrienes and histamine, and are discharged into the middle meatus at a flow rate of 1 cm/min so that the antral mucous can be entirely changed in ~20-30 minutes 15. Mucous production is influenced by sympathetic and parasympathetic control, neuropeptide release, physical environmental factors, and drugs 15, and maxillary drainage depends on sinus oxygenation, which is mainly provided by direct gaseous exchange as the amount of blood oxygen is not enough 15. Maxillary secretions can only be removed via the active transport system of drainage because they cannot take advantage of the force of gravity: in fact, the natural ostium, in the adult population, is located high up in the medial wall, several millimeters over the sinusal floor. Findings emerging from some experimental studies suggest that muco-ciliar transport runs along genetically determined star-shaped pathways 16 from the maxillary floor towards the natural ostium, which is the exclusive discharge point even in the presence of other naturally or surgically made openings. Mucous flow also seems to adapt to the shape of the inside of the sinus as the secretions thicken at the rising bony edge and the gel phase slides over the serous phase in order to cross the narrowest passages by means of the so-called “bridging phenomenon” 15. The pathophysiology underlying maxillary sinus disease is impaired sinus secretion drainage related to ostial patency, impaired epithelial function or altered nasal secretions 17. Sinusal homeostasis is compromised in the presence of pathogenic noxae, such as environmental factors (pollution, impaired inspired air humidity), systemic diseases interfering with mucous composition or ciliar movements (cystic fibrosis, Kartagener’s and Mounier-Kuhn’s syndrome, dehydration, ciliostatic drugs), or anatomical variations that hinder physiological maxillary ventilation and drainage (such as a hyperplastic uncinate process, concha bullosa, maxillary ostium stenosis, septal deviations or nasal polyposis obstructing the medio-meatal region). This leads to impaired maxillary drainage and ciliar activity, with decreased oxygen and increased carbon dioxide concentrations, and is followed by epithelial dysfunction, which predisposes to infections causing oedema and mucosal hypertrophy of the ostio-meatal complex (OMC), with deterioration in sinusal ventilation and drainage 15.

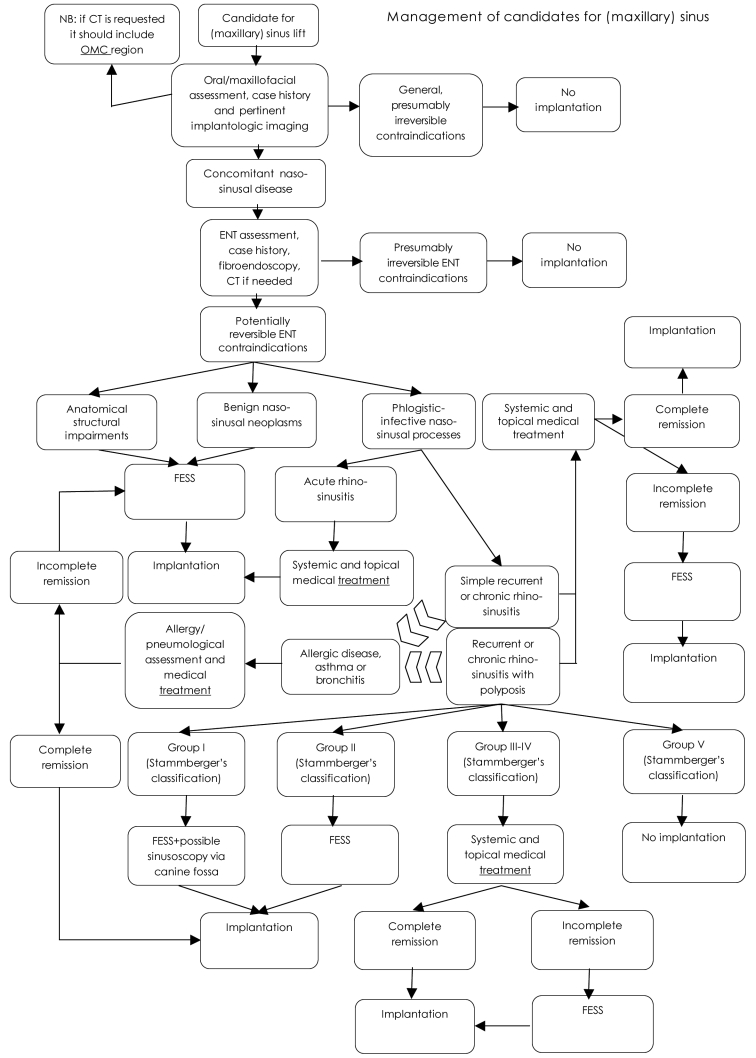

Fig. 1.

Flow chart. Management of candidates for (maxillary) sinus lifting.

Effect of sinus lifting on maxillary sinus homeostasis

Any surgical treatment of the maxillary sinus activates cellular inflammatory mediators and promotes transient sinusitis, and the larger the exposed area, the more likely it is that there will be a post-surgical inflammatory reaction. In the case of a sinus lift, the development of a secondary infection leads to possible bone graft loss 18. Maxillary sinusitis is, in fact, the most frequent post-lifting complication and, although the diagnostic criteria used are not always clear 18, it has been reported in 0-27% of cases in clinical studies 19–26. In a more recent study that used standard diagnostic ENT criteria, sub-acute maxillary sinusitis developed in 4.5% of the patients undergoing sinus lifting, and post-elevation chronic maxillary sinusitis in 1.3% 27. Sinus lifting can obstruct physiological maxillary drainage into the middle meatus in various ways. The traumatic lifting of Schneider’s membrane to above the maxillary floor may transiently and unpredictably inhibit ciliar activity 15 and also predispose to altered mucus composition due to bacterial infections 15, as may perforating the membranous sinusal lining during detachment (which may occur in up to 56% of cases) 24 25. Furthermore, OMC patency may be impaired by:

transient inflammatory peri-ostial swelling;

excessive raising of the maxillary mucosal floor, especially in the presence of antral cysts lining the sinusal floor 18, which may be observed in 1.6-22% of cases 28–32;

graft fragments passing through mucosal lacerations into the maxillary sinus and obstructing the natural ostium, especially if these are > 5 mm 15 33.

However, it is well known that the sinusal mucosa can promptly repair tears due to surgery 34, and, therefore, it must be assumed that every sinus lifting procedure temporarily impairs maxillary sinusal physiology and sometimes prevents the post-operative restoration of normal sinusal homeostasis, which can lead to maxillary bacterial sinusitis and thus compromise surgical outcome and patient well-being. In this regard, and confirming other reports 8 35, a prospective study by Timmenga et al. 36 showed that the maxillary mucosa can recover after sinus lifting, especially if sinus drainage is normal. The finding, in that study, of a mild post-operative inflammatory reaction, upon the histo-morphological examination of maxillary sinus mucosal biopsies 36, should, therefore, be interpreted as a physiological expression of the mucosal airway defense system, which can also be seen in healthy subjects who have not undergone surgery 36 37. The rapid return of the maxillary sinus to a post-operative sterile state is also well known 36 38. This intrinsic potential of the sinus mucosa to resume its homeostatic status after the surgical trauma caused by sinus lifting is known as sinus compliance: the better the starting conditions (high compliance), the lower the risk of complications. On the other hand, an excessive risk should be considered a contraindication to the procedure. An ambitious target is to identify sufficient objective parameters to create a “sinus compliance index” that could be used to assess the suitability of sinus lifting in individual patients.

Step 1. The first preventive/diagnostic ENT assessment

Given the above considerations, sinus compliance of each individual patient (or the presence of risk factors for post-elevation sinusitis) should be evaluated pre-operatively in order to define a relative risk threshold based on the probability of post-operative complications (Flow chart). This involves taking a careful case history in order to identify any previous nasal trauma or surgery, nasal respiratory obstruction, or recurrent or chronic naso-sinusal diseases 12, as well as the presence of any systemic diseases that may interfere with implant integration, such as uncompensated diabetes mellitus, immunodeficient disease, voluptuous habits (smoking, alcohol abuse, cocaine use), odontoiatric diseases (periapical diseases, parodontopathies), or maxillary irradiation 5 9 15 25. Furthermore, all patients with radiological or anamnestic evidence suggesting maxillary sinusal dysventilation should undergo otorhinolaryngological examination with nasal endoscopy and, if indicated, computed tomography (CT) of the maxillo-facial district (including the OMC) in order to identify any possible contraindications to sinus lifting. This will lessen the risk of post-operative complications, thus providing relief for the patient and a good medico-legal guarantee for the oral surgeon.

Radiological assessment

It has been shown that conventional radiographic imaging is only 73% reliable, in the case of maxillary sinus mucosal diseases 18. However, this diagnostic gap has now been filled by the introduction of high resolution axial and coronal paranasal CT 39, and pre-operative CT of the maxillo-facial district (with acquisition of the OMC), especially the new multi-slice CT with sub-millimetric acquisitions, has become almost mandatory in managing implant surgery when naso-sinusal diseases are suspected 40–42. CT imaging is extremely useful as it can assess maxillary bone height 41 and thus make it possible to determine the best surgical approach, the timing of implant placement (simultaneous vs. delayed), and the most suitable type of graft. As many implantologists routinely request CT-maxillary DENTASCAN in order to prepare the implant positioning, it is very important, in our opinion, that the radiologist studies also the OMC, if a sinus lift is programmed. It has also been suggested that maxillary sinus volume can be pre-operatively measured by means of the three-dimensional reconstruction of the CT images in order to choose the best donor site when autogenous bone grafts are needed 43, however, this application does not seem to be routinely practicable 43. CT can pre-operatively detect the presence of a narrow maxillary sinus 44, or aberrant sinus anatomy and Underwood’s septa, which have been reported in 20-58% of cases 45–48. Studying sinus morphology, by means of CT scans, provides precious information since when septa are present in the sinus floor, they can complicate sinus elevation by hampering bone plate inversion and lifting of the sinus membrane 22. CT scans with acquisition of OMC also play a primary role in managing sinus lift, from the ENT point of view, as they very precisely indicate the position and patency of the maxillary ostium, and detect any associated middle-meatal anatomical alterations or concomitant sinus diseases 12 that should be corrected before attempting sinus elevation, because the risk of developing post-operative sinusitis is increased in patients with impaired sinus clearance 3. Other radiological investigations that have become increasingly important in assessing sinus diseases include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) 49, although it is not useful for bone evaluation.

Endoscopy

Nasal endoscopy is a widely accepted means of assessing the middle meatus 3 because, by directly visualising the OMC, it can pre-operatively detect the factors impairing maxillary sinus drainage that may be responsible for a negative surgical outcome. Furthermore, it is particularly useful in managing their surgical correction before attempting sinus elevation. The main purpose of an endoscopic examination is to evaluate the condition of the infundibulo-meatal area, which is sometimes compromised by spatial competition between its foremost components (the uncinate process, the ethmoidal bulla and the agger nasi) 50 51 and other anatomical structures, such as the septal crests, the concha bullosa of the middle turbinate or its paradoxical bending, or a massive ethmoidal polyp 12. A relationship has been documented between the post-operative development of sinusitis and pre-existing maxillary sinus diseases 22 as well as a correlation between sinusitis and the size of the maxillary ostium 52. On the grounds that the cranial position of the maxillary ostium makes its mechanical blocking unlikely 3, a number of Authors 3 recommend nasal endoscopy before maxillary sinus elevation only in the case of patients with previous maxillary pathological processes or a documented history of impaired maxillary clearance, and it has also been suggested that an endoscopic finding of mild mucosal inflammation does not strictly contraindicate sinus lifting 37.

Otorhinolaryngological contraindications to a maxillary sinus lift

Any otorhinolaryngological contraindications should be detected pre-operatively and, if possible, corrected before undertaking a sinus lift procedure.

These contraindications can be divided into those presumably irreversible and those that are potentially reversible 15 53 54. The former include:

anatomic-structural permanent and not correctable impairments of the nasal walls and/or naso-sinus mucosa that may seriously interfere with normal homeostatic naso-sinusal physiology (e.g., post-traumatic or post-surgical scars, sequelae of radiotherapy);

inflammatory-infective processes, including recurrent or chronic sinusitis (with or without concomitant naso-sinusal polyps), that cannot be resolved because associated with congenitally impaired muco-ciliar clearance (e.g., cystic fibrosis, Kartagener’s syndrome, Young’s syndrome), acetylsalicylic acid hypersensitivity (as defined by the distinguishing clinical triad of naso-sinus polyposis, asthma and acetylsalicylic acid hypersensitivity), or immunological defects (e.g., acquired immunodeficiency deficit syndrome, pharmacological immunosuppression);

naso-sinusally located aspecific systemic granulomatosis diseases (e.g., Wegener’s granulomatosis, sarcoidosis);

benign naso-sinusal neoplasms (e.g., inverted papilloma, myxoma, ethmoido-maxillary fibromatosis), and malignant naso-sinus neoplasms involving the maxillary sinus and/or the adjacent anatomic structures (e.g., metastases and primary neoplasms originating from the epithelium, neuroectoderma, bone, soft tissue, dental tissue or lymphatic system tumours) that seriously interfere with naso-sinusal homeostasis, both before and after treatment.

However, there are many more otorhinolaryngological contraindications that are potentially reversible by means of appropriate medical or surgical treatment:

limited anatomic-structural impairments of the maxillary sinus drainage pathways (e.g., septal deviation, paradoxical bending of the middle turbinate, concha bullosa, hypertrophy of the agger nasi, the presence of Haller cells, post-surgical endonasal scars, synechiae of the OMC);

phlogistic-infective processes (e.g., acute viral or bacterial rhino-sinusitis, non-invasive mycotic rhino-sinusitis, recurrent and chronic rhino-sinusitis favoured by one of the above-mentioned anatomic alterations conditioning a stenosis of the maxillary drainage pathways), allergic rhino-sinusitis, naso-sinusal polyposis group I-IV (Stammberger’s classification);

antro-ethmoidal foreign bodies;

oro-antral fistula not associated with a wide bone gap and after a definitive surgical closure;

benign naso-sinusal neoplasms that impair the maxillary drainage pathways before or would do after the sinus lift procedure, removal of which can restore naso-sinusal homeostasis and not damage the muco-ciliar transport system (e.g., mucous cysts, cholesterinic granulomas, choanal polyps).

Many of these potentially reversible otorhinolaryngological sinus lift contraindications are electively amenable to functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS).

Step 2. Prevention and therapy: the role of endoscopic surgery

The potentially reversible otorhinolaryngological contraindications to sinus lift surgery need to be corrected by means of conservative medical therapy or functional endoscopic sinus surgery – FESS – (the current gold standard for many naso-sinusal conditions amenable to surgery) in order to restore physiological maxillary sinus clearance and ventilation, after which it is possible to perform the sinus lift procedure to begin oral rehabilitation. Some Authors 55–57 have also proposed endoscopically controlled sinus floor augmentation procedures in order to check the positioning of graft material intra-operatively and assess the integrity of Schneider’s membrane by directly observing its elastic deformation until the maximum elevation has been reached. However, this cannot be considered a standard procedure, the use of which should be confined to scientific trials as it is still technically demanding and requires considerable additional equipment. Furthermore, although it can promptly visualize perforations of the sinus membrane, it cannot avoid their occurrence 57.

Herewith, a brief description of the current therapeutic options for the treatment of some of the potentially reversible otorhinolaryngological contraindications to sinus lifting.

Rhino-sinusitis and benign naso-sinus neoplasms

As far as concerns acute rhino-sinusitis, which affects up to 16% of the US population 58 59 and 8% of Europeans 60, the medical treatment should be established by an ENT specialist. This may involve orally administered non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs 61 and the use of topical decongestants (for a maximum of 3 days) in order to restore sinusal ostial patency and provide symptomatic relief 61 62. If acute viral rhino-sinusitis is suspected, antibiotics are not recommended 63, and patients with non-severe acute bacterial rhino-sinusitis should be considered candidates for clinical observation if follow-up is guaranteed 64. If a patient’s condition fails to improve within 7 days of diagnosis, or worsens at any time 61, antibiotics, such as amoxicillin 65–67 or extended spectrum cephalosporins 68 should be started and given for at least 7 days 69. There is no evidence supporting the effectiveness of systemic steroids for acute rhino-sinusitis, and only weak evidence supports the use of topical nasal steroids in patients with acute viral rhino-sinusitis or allergic rhinitis (these may reduce mucosal swelling) 61 70. A number of (mainly industry supported) clinical trials have shown the efficacy of topical corticosteroids in cases of acute bacterial rhino-sinusitis 71 72, but the use of decongestants and corticosteroids in addition to saline irrigation and mucolytics has not been approved by the American Food and Drug Administration for acute rhino-sinusitis. The clinical impact of antihistamine therapy on viral rhino-sinusitis has not yet been assessed 61, but it does not seem to be substantial in non-atopic patients with acute bacterial rhino-sinusitis 64.

In addition to eliminating the infection, the current treatment of chronic rhino-sinusitis also involves identifying and correcting the underlying predisposing factor (anatomical alterations of the OMC, allergopathy, nasal polyposis). Endoscopic surgery has become the common means of ensuring functional rehabilitation as it allows precise and decisive therapeutic intervention with minimal negative effects on delicate naso-sinusal physiology 73 and good patient outcome. In the most advanced centres, the traditional approaches to maxillary sinus surgery have been replaced by endoscopic uncinectomy, middle meatal antrostomy, and anterior and posterior ethmoidectomy 73. A description of the surgical treatment of the structural anomalies conditioning impaired maxillary sinus drainage is given in the next section. In the case of allergic rhino-sinusitis or concomitant asthma, medical treatment should first be established with topical or systemic antihistamines 74, disodium chromoglycate and specific immunotherapy 73 and, if necessary, the patient should be referred for an allergy assessment. In the case of recurrent bronchitis, a pneumological evaluation may also be useful. Patients with concomitant nasal polyposis, which has a general population incidence of 0-86% among males and 0-39% among females 75 should be classified into treatment groups on the basis of the extent of the pathology. Patients in Stammberger clinical group I (with antrochoanal polyposis, ACP) 76 should undergo surgery as first-line therapy 77 78: the ACP is resected using an endoscopic trans-nasal approach, and then a middle meatal antrostomy is performed in order to remove the base from the maxillary sinus 79 80. The use of powered FESS instrumentation has also recently been described to be effective in completely removal of an ACP including its antral portion 81 82. When the antral portion cannot be reached trans-nasally, a combined approach through the canine fossa may be used 79. Any other benign naso-sinus neoplasms, such as maxillary mucous cysts, should also be surgically removed or aspirated before 33 or at the time of sinus augmentation 53. Patients in Stammberger’s group II (with spheno-choanal or ethmoido-choanal polyps) 76 should undergo polypectomy together with sphenoidotomy by means of the direct paraseptal route or selective posterior ethmoidotomy using FESS 79. Stammberger group III and IV patients (with nasal polyposis associated with chronic rhino-sinusitis without or with eosinophilia) 76 should undergo endoscopic surgical treatment if complete recovery cannot be achieved by means of medical treatment with antibiotics and systemic steroids 83, and post-operative topical steroid treatment should be used to avoid recurrences 79. In the case of non-invasive fungal sinusitis, the fungal ball should be removed by means of trans-nasal endoscopy 84, whereas the current therapy, for allergic fungal sinusitis, is endoscopic sinus surgery with topical administration of corticosteroids and antimycotic drugs 85.

Anatomical alterations of the OMC and oro-antral fistulas

In the case of sinus diseases associated with anatomical alterations that impair physiological maxillary drainage and are responsible for sinus dysventilation, FESS should be used to restore OMC patency before the sinus lifting is performed. Nasal septum deviations, which in the general population reach an incidence of 56.4% 86, are some of the most frequent findings requiring surgical correction. In addition to the traditional headlight technique, endoscopic – and now powered functional endoscopic 87 – septal surgery is considered a safe and efficacious approach, especially in the case of posterior and superior deformities which are difficult to access using the traditional technique, and can be performed at the same time as FESS 88 89. Large agger nasi cells, which are found in up to 52% of the population 86 90 91, are endoscopically opened 12, whereas true conchae bullosae or pneumatisations of the middle turbinate, with an incidence of 8.3-42.5% in the general population 86 90–94 require surgical resection of the lateral bony lamella of the pneumatised middle turbinate 12. Any other naso-sinusal anatomic variations, such as paradoxical bending of the middle turbinate (general population incidence 5.3-24.2%) 86 90–93, or infra-orbital ethmoidal (Haller) cell (general population incidence 1-9.4%) 86 90 91, as well as post-surgical synechias of the OMC, which occur in 0.4-44% of the patients undergoing nasal surgery depending on the surgical technique 95–98, need to be endoscopically corrected before attempting sinus lifting if they are associated with anamnestic, clinical or instrumental findings of sinus disease. Oro-antral fistulas, which have a reported incidence of 5-25% after upper teeth extraction 99 100 are clear contraindications to a sinus lift. They must, therefore, be treated first by means of surgical correction and adequate medical treatment 101 in order to obtain a disease-free sinus environment 102. The successful long-term closure of an oro-antral fistula depends on the physiological status of the maxillary sinus 103. Once the alveolo-antral areas have stably and completely healed, the possibility of a sinus lift can be considered depending upon the local situation and residual bone gap.

Step 3. Diagnosis and therapy: the management of post-operative complications

The postoperative complications of sinus lift may be distinguished between early and late complications: the former include tearing Schneider’s membrane, intra-surgical displacement of implants into maxillary sinus, dehiscence of the oral surgical wound with oro-antral fistula formation, hematomas and acute maxillary sinusitis; the latter include chronic maxillary sinusitis and bone sequestration sometimes leading to bone graft and implant loss 12 33. Tearing of Schneider’s membrane may occur if the pouch is overfilled, especially with sharp-angled grafting material, or if intra-operative membrane detachment is inadequate 48 104. Maxillary sinusitis is the most frequent post-operative complication 19–26, although its post-lifting occurrence is not always defined using precise ENT criteria 18. It may be caused by:

lack of asepsis during the surgical procedure 38;

dysventilation of the maxillary sinus, due to ostial obstruction, as a result of mucosal oedema 105;

infection of non-vital bony fragments floating into the sinus 106;

a previously undetected disease impairing maxillary drainage.

Small intra-operative perforations of the sinus membrane do not seem to be responsible for maxillary sinusitis in healthy subjects 18, but larger perforations expose more of the grafted bone surface to the sinusal environment, and, therefore, lead to a greater risk of penetration of bony fragments into the sinus lumen and the development of post-lifting rhino-sinusitis 18 106. The pathogenic mechanism may start with the protrusion of debris-covered implants into the sinus lumen where, as foreign bodies, they may give rise to inflammation impairing the muco-ciliar system; the subsequent mucosal swelling leads to maxillary ostial obstruction, infection, and rhino-sinusitis 107. General guidelines for the prevention of transient and chronic maxillary rhino-sinusitis, after sinus lifting, include peri-operative antibiotic prophylaxis and post-operative administration of topical corticosteroids in order to ensure the patency of the maxillary ostium 3 21 25 108 109. The use of decongestants is controversial because, by inducing vasoconstriction, they may further compromise the already low oxygen tension in the sinus 110. The role of ENT specialists, in the case of post-elevation maxillary rhino-sinusitis, is to guarantee early diagnosis and treatment. Early medical or (in advanced stages) surgical treatment, able to promptly restore maxillary sinus ventilation and drainage, would not only avoid the loss of graft and implants, but also prevent major complications, such as venous septic thrombosis, especially in the case of acute purulent events 12 34. For a correct and prompt diagnosis, in addition to nasal and sinus endoscopy, the ENT specialist can proceed with aspiration of sinus contents for cytological examination and microbiological assessment 111. CT is also an extremely useful means of detecting pathological processes. If medical therapy alone fails to control the sinus infection, the guidelines for the treatment of transient rhino-sinusitis suggest the use of trans-nasal endoscopy to establish maxillary drains for sinus irrigation and, if this fails to bring about complete recovery within three weeks (or in the presence of exposed and sequestered endosinusal grafts), surgical curettage, by means of FESS, should be taken into consideration 3 12 35 102 108 109. In the case of chronic maxillary rhino-sinusitis, endoscopic surgical treatment should be used in addition to medical treatment 3 35 102 108 109. Published data and our own experience show that infected graft material and implants should be removed because eliminating the source of infection will avoid recurrences of rhino-sinusitis 102 112; however, some Authors 107 have successfully used alternative treatments consisting of partial resection of the grafts. Inappropriate positioning or accidental displacement of dental implants, inside the maxillary sinus, have been also reported as late complications after sinus lifting 5 25. If such events are confirmed by means of diagnostic nasal endoscopy and radiology, the migrated implants should be surgically removed in order to prevent the development of rhino-sinusitis due to interrupted muco-ciliary clearance or a tissue reaction 113–115. In the case of nasal or sinusal diseases, FESS should be considered the option of choice but, in the absence of sinus infection and if the OMC is normal, the implants can be retrieved using:

the traditional Caldwell-Luc surgical approach, which consists of retrieving them through a window created in the antero-lateral maxillary sinus wall 25;

more conservative maxillary anterior wall resection 116;

the endoscopic insertion of a trocar through the canine fossa 10 11;

the endoscopic insertion of a new type of trocar that improves the ergonomy of the operation by allowing simultaneous endoscopic vision and the use of surgical instruments (e.g., aspirator, grasping forceps, etc.) (Fig. 2);

Fig. 2.

New trocar for endoscopic trans-canine approach conceived by M.M. and L.P. and presented at IV National Congress of ENT University Association (5 December 2007, Mestre, Italy).

It is worthwhile pointing out that these surgical approaches can be used under local anaesthesia if the patient is compliant and the surgeon is experienced. All the above-mentioned considerations indicate that the cooperation of an ENT specialist is also useful in the management of this post-lifting complication, as trans-nasal endoscopic retrieval of migrated implants allows the simultaneous treatment of the concomitant mucosal disease related to implant displacement and any associated ostial obstruction with minimal invasiveness and less morbidity than that related to the standard approach 119.

Conclusions

Whenever concomitant dysventilatory naso-sinusal diseases are suspected, ENT specialists are primary figures in the management of candidates for sinus lifting. Their involvement in all three preventive-diagnostic, preventive-therapeutic and diagnostic-therapeutic steps makes it possible to identify any presumably irreversible or potentially reversible contraindications to sinus lifting and resolve (when possible) the pathological processes or anatomical impairments potentially leading to surgical failure, as well as ensure the early detection and treatment of any post-operative complications that may compromise good surgical outcome. The availability of a multi-disciplinary surgical team, including a well-trained ENT specialist, not only increases the likelihood of a better procedural outcome, but also provides a good medico-legal guarantee for the oral or maxillofacial surgeons attempting a sinus lift.

References

- 1.Boyne PJ, James RA. Grafting of the maxillary sinus floor with autogenous marrow bone. J Oral Surg 1980;38:613-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raghoebar GM, Brouwer TJ, Reintsema H, Van Oort RP. Augmentation of the maxillary sinus floor with autogenous bone for the placement of endosseous implants: a preliminary report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1993;51:1198-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Timmenga NM, Raghoebar GM, Boering G, van Weissenbruch R. Maxillary sinus function after sinus lifts for the insertion of dental implants. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1997;55:936-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van den Bergh JP, ten Bruggenkate CM, Krekeler G, Tuinzing DB. Maxillary sinus floor elevation and grafting with human demineralized freeze dried bone. Clin Oral Implants Res 2000;11:487-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smiler DG, Johnson PW, Lozada JL, Misch C, Rosenlicht JL, Tatum OH Jr, et al. Sinus lift grafts and endosseous implants. Treatment of the atrophic posterior maxilla. Dent Clin North Am 1992;36:151-86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.ten Bruggenkate CM, van den Bergh JP. Maxillary sinus floor elevation: a valuable pre-prosthetic procedure. Periodontol 2000 1998;17:176-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raghoebar GM, Timmenga NM, Reintsema H, Stegenga B, Vissink A. Maxillary bone grafting for insertion of endosseous implants: results after 12-124 months. Clin Oral Implants Res 2001;12:279-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jensen OT, Shulman LB, Block MS, Iacono VJ. Report of the Sinus Consensus Conference of 1996. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 1998;13 Suppl:11-45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Small SA, Zinner ID, Panno FV, Shapiro HJ, Stein JI. Augmenting the maxillary sinus for implants: report of 27 patients. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 1993;8:523-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stammberger H. Functional Endoscopic Sinus Surgery. The Messerklinger Technique. First Edn. Philadelphia: BC Decker; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lang J, Bressel S. The hiatus semiluminaris, the infundibulum and the ostium of the sinus maxillaris, the anterior attached zone of the concha nasalis and its distance to the landmarks of the outer and inner nose. Gegenbaurs Morphol Jahrb 1988;134:637-46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Testori T, Weinstein R, Wallace S. La chirurgia del seno mascellare e le alternative terapeutiche. First Edn. Viterbo: Acme-Promoden; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stammberger H. History of rhinology: anatomy of the paranasal sinuses. Rhinology 1989;27:197-210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stammberger H. Nasal and paranasal sinus endoscopy. A diagnostic and surgical approach to recurrent sinusitis. Endoscopy 1986;18:213-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mantovani M. Implicazioni otorinolaringoiatriche nell’elevazione del seno mascellare. In: Testori T, Weinstein R, Wallace S, editors. La chirurgia del seno mascellare e le alternative terapeutiche. Viterbo: Acme-Promoden; 2005. p. 40. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Messerklinger W. On the drainage of the human paranasal sinuses under normal and pathological conditions. 1. Monatsschr Ohrenheilkd Laryngorhinol 1966;100:56-68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bailey BJ. Head and neck surgery-Otolaryngology. Second Edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buiter C. Endoscopy of the upper airways. First Edn. Amsterdam: Exerpta Medica; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Misch CE. Maxillary sinus augmentation for endosteal implants: organized alternative treatment plans. Int J Oral Implantol 1987;4:49-58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chanavaz M. Maxillary sinus: anatomy, physiology, surgery, and bone grafting related to implantology-eleven years of surgical experience (1979-1990). J Oral Implantol 1990;16:199-209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quiney RE, Brimble E, Hodge M. Maxillary sinusitis from dental osseointegrated implants. J Laryngol Otol 1990;104:333-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tidwell JK, Blijdorp PA, Stoelinga PJ, Brouns JB, Hinderks F. Composite grafting of the maxillary sinus for placement of endosteal implants. A preliminary report of 48 patients. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1992;21:204-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ueda M, Kaneda T. Maxillary sinusitis caused by dental implants: report of two cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1992;50:285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kasabah S, Krug J, Simunek A, Lecaro MC. Can we predict maxillary sinus mucosa perforation? Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove) 2003;46:19-23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Regev E, Smith RA, Perrott DH, Pogrel MA. Maxillary sinus complications related to endosseous implants. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 1995;10:451-61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaptein ML, de Putter C, de Lange GL, Blijdorp PA. Survival of cylindrical implants in composite grafted maxillary sinuses. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1998;56:1376-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Timmenga NM, Raghoebar GM, van Weissenbruch R, Vissink A. Maxillary sinusitis after augmentation of the maxillary sinus floor: a report of 2 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2001;59:200-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Casamassimo PS, Lilly GE. Mucosal cysts of the maxillary sinus: a clinical and radiographic study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1980;50:282-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Allard RH, van der Kwast WA, van der Waal I. Mucosal antral cysts. Review of the literature and report of a radiographic survey. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1981;51:2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.MacDonald-Jankowski DS. Mucosal antral cysts in a Chinese population. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 1993;22:208-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacDonald-Jankowski DS. Mucosal antral cysts observed within a London inner-city population. Clin Radiol 1994;49:195-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harar RP, Chadha NK, Rogers G. Are maxillary mucosal cysts a manifestation of inflammatory sinus disease? J Laryngol Otol 2007;121:751-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ziccardi VB, Betts NJ. Complicanze dell’incremento del seno mascellare. In: Jensen OT, editor. Gli innesti del seno mascellare in implantologia. Milano: Scienza e Tecnica Dentistica; 2000. p. 201. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zimbler MS, Lebowitz RA, Glickman R, Brecht LE, Jacobs JB. Antral augmentation, osseointegration, and sinusitis: the otolaryngologist’s perspective. Am J Rhinol 1998;12:311-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stammberger H. Endoscopic endonasal surgery: concepts in treatment of recurring rhinosinusitis. Part II. Surgical technique. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1986;94:147-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Timmenga NM, Raghoebar GM, Liem RS, van Weissenbruch R, Manson WL, Vissink A. Effects of maxillary sinus floor elevation surgery on maxillary sinus physiology. Eur J Oral Sci 2003;111:189-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Timmenga NM, Raghoebar GM, van Weissenbruch R, Vissink A. Maxillary sinus floor elevation surgery. A clinical, radiographic and endoscopic evaluation. Clin Oral Implants Res 2003;14:322-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Misch CM. The pharmacologic management of maxillary sinus elevation surgery. J Oral Implantol 1992;18:15-23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zinreich SJ. Imaging of chronic sinusitis in adults: X-ray, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1992;90:445-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tachibana H, Matsumoto K. Applicability of X-ray computerized tomography in endodontics. Endod Dent Traumatol 1990;6:16-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dula K, Buser D. Computed tomography/oral implantology. Dental-CT: a program for the computed tomographic imaging of the jaws. The indications for preimplantological clarification. Schweiz Monatsschr Zahnmed 1996;106:550-63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Besimo C, Lambrecht JT, Nidecker A. Dental implant treatment planning with reformatted computed tomography. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 1995;24:264-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Uchida Y, Goto M, Katsuki T, Soejima Y. Measurement of maxillary sinus volume using computerized tomographic images. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 1998;13:811-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van den Bergh JP, ten Bruggenkate CM, Disch FJ, Tuinzing DB. Anatomical aspects of sinus floor elevations. Clin Oral Implants Res 2000;11:256-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Underwood AS. An inquiry into the anatomy and pathology of the maxillary sinus. J Anat Physiol 1910;44:354-69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jensen OT, Greer R. Immediate placing of osseointegrating implants into the maxillary sinus augmented with mineralized cancellous allograft and Gore-Tex: second-stage surgical and histological findings. In: Laney WR, Tolman DE, editors. Tissue integration in oral orthopaedic and maxillofacial reconstruction. Chicago: Quintessence; 1992. p. 321. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Betts NJ, Miloro M. Modification of the sinus lift procedure for septa in the maxillary antrum. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1994;52:332-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ulm CW, Solar P, Krennmair G, Matejka M, Watzek G. Incidence and suggested surgical management of septa in sinus-lift procedures. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 1995;10:462-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.White SC, Pharoah MJ. Oral radiology-Principles and practice. Fourth Edn. St Louis: Mosby, Year Book Inc.; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Metha D. Atlas of endoscopic sinusal surgery. First Edn. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Watelet JB, Van Cauwenberge P. Applied anatomy and physiology of the nose and paranasal sinuses. Allergy 1999;54:14-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stierna P, Soderlund K, Hultman E. Chronic maxillary sinusitis. Energy metabolism in sinus mucosa and secretion. Acta Otolaryngol 1991;111:135-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mantovani M. Controindicazioni ORL al lifting antrale. In: XII Congresso Nazionale SICO. Montecatini Terme: 2001. p. 9-13. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sambataro G, Mantovani M, Scotti A. Rialzo del seno mascellare e implicazioni sulle sue funzioni. In: Chiapasco M, Romeo E, editors. La riabilitazione impiantivo-protesica nei casi complessi. Torino: Utet; 2003. p. 292. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Engelke W, Deckwer I. Endoscopically controlled sinus floor augmentation. A preliminary report. Clin Oral Implants Res 1997;8:527-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baumann A, Ewers R. Minimally invasive sinus lift. Limits and possibilities in the atrophic maxilla. Mund Kiefer Gesichtschir 1999;3:S70-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nkenke E, Schlegel A, Schultze-Mosgau S, Neukam FW, Wiltfang J. The endoscopically controlled osteotome sinus floor elevation: a preliminary prospective study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2002;17:557-66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Benson V, Marano MA. Current estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, 1995. Hyattsville (MD): National Center for Health Statistics; 1998 [Data from Vital and Health Statistics, series 10: data from the National Health survey, No. 199:1-428]. [PubMed]

- 59.Cherry DK, Woodwell DA. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2000 Summary. Hyattsville (MD): National Center for Health Statistics; 2000 [Advance data from Vital and Health Statistics, No. 328:1-32]. [PubMed]

- 60.Anand VK. Epidemiology and economic impact of rhinosinusitis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2004;193:3-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rosenfeld RM, Andes D, Bhattacharyya N, Cheung D, Eisenberg S, Ganiats TG, et al. Clinical practice guideline: adult sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2007;137:S1-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Caenen M, Hamels K, Deron P, Clement P. Comparison of decongestive capacity of xylometazoline and pseudoephedrine with rhinomanometry and MRI. Rhinology 2005;43:205-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arroll B, Kenealy T. Antibiotics for the common cold and acute purulent rhinitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;3:CD000247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fokkens W, Lund V, Bachert C, Clement P, Helllings P, Holmstrom M, et al. EAACI position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps executive summary. Allergy 2005;60:583-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lau J, Zucker D, Engels EA, Balk E, Barza M, Terrin N. Diagnosis and treatment of acute bacterial rhinosinusitis. Evid Rep Technol Assess 1999;9:1-5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Williams JWJ, Aguilar C, Cornell J, Chiquette ED, Makela M, Holleman DR. Antibiotics for acute maxillary sinusitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;2:CD000243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.[No authors listed]. Antimicrobial treatment guidelines for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis. Sinus and Allergy Health Partnership. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2000;123:5-31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Benninger M. Guidelines on the treatment of ABRS in adults. Int J Clin Pract 2007;61:873-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gehanno P, Beauvillain C, Bobin S, Chobaut JC, Desaulty A, Dubreuil C. Short therapy with amoxicillin-clavulanate and corticosteroids in acute sinusitis: results of a multicentre study in adults. Scand J Infect Dis 2000;32:679-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Malm L. Pharmacological background to decongesting and anti-inflammatory treatment of rhinitis and sinusitis. Acta Otolaryngol 1994;515:53-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dolor RJ, Witsell DL, Hellkamp AS, Williams JW Jr, Califf RM, Simel DL. Comparison of cefuroxime with or without intranasal fluticasone for the treatment of rhinosinusitis. The CAFFS Trial: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001;286:3097-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Meltzer EO, Bachert C, Staudinger H. Treating acute rhinosinusitis: comparing efficacy and safety of mometasone furoate nasal spray, amoxicillin, and placebo. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005;116:1289-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Passali D, Bellussi L. Revision of the European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyposis (EP3OS) with particular attention to acute and recurrent rhinosinusitis. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 2007;27:1-21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Braun JJ, Alabert JP, Michel FB, Quiniou M, Rat C, Cougnard J. Adjunct effect of loratadine in the treatment of acute sinusitis in patients with allergic rhinitis. Allergy 1997;52:650-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Larsen K, Tos M. The estimated incidence of symptomatic nasal polyps. Acta Otolaryngol 2002;122:179-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stammberger H. Examination and endoscopy of nose and paranasal sinuses. In: Mygind N, Lindholdt T, editors. Nasal polyps. An inflammatory disease and its treatment. Copenhagen: Munksgaard; 1997. p. 120. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Basak S, Karaman CZ, Akdilli A, Metin KK. Surgical approaches to antrochoanal polyps in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 1998;46:197-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Aktas D, Yetiser S, Gerek M, Kurnaz A, Can C, Kahramanyol M. Antrochoanal polyps: analysis of 16 cases. Rhinology 1998;36:81-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Castelnuovo P, De Bernardi F, Delù G, Padoan G, Bignami M, De Zen M. Rational treatment of nasal polyposis. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 2005;25:3-29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bozzo C, Garrel R, Meloni F, Stomeo F, Crampette L. Endoscopic treatment of antrochoanal polyps. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2007;264:145-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hong SK, Min YG, Kim CN, Byun SW. Endoscopic removal of the antral portion of antrochoanal polyp by powered instrumentation. Laryngoscope 2001;111:1774-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gendeh BS, Long YT, Misiran K. Antrochoanal polyps: clinical presentation and the role of powered endoscopic polypectomy. Asian J Surg 2004;27:22-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bachert C, Hörmann K, Mösges R, Rasp G, Riechelmann H, Müller R. An update on the diagnosis and treatment of sinusitis and nasal polyposis. Allergy 2003;58:176-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Grosjean P, Weber R. Fungus balls of the paranasal sinuses: a review. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2007;264:461-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Castelnuovo P, Gera R, Di Giulio G, Canevari FR, Benazzo M, Emanuelli E. Paranasal sinus mucose. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 2000;20:6-15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lerdlum S, Vachiranubhap B. Prevalence of anatomic variation demonstrated on screening sinus computed tomography and clinical correlation. J Med Assoc Thai 2005;88:S110-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sousa A, Iniciarte L, Levine H. Powered endoscopic nasal septal surgery. Acta Med Port 2005;18:249-55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Giles WC, Gross CW, Abram AC, Greene WM, Avner TG. Endoscopic septoplasty. Laryngoscope1994;104:1507-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Castelnuovo P, Pagella F, Cerniglia M, Emanuelli E. Endoscopic limited septoplasty in combination with sinonasal surgery. Facial Plast Surg 1999;15:303-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Liu X, Zhang G, Xu G. Anatomic variations of the ostiomeatal complex and their correlation with chronic sinusitis: CT evaluation. Zhonghua Er Bi Yan Hou Ke Za Zhi 1999;34:143-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mazza D, Bontempi E, Guerrisi A, Del Monte S, Cipolla G, Perrone A. Paranasal sinuses anatomic variants: 64-slice CT evaluation. Minerva Stomatol 2007;56:311-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Basic N, Basic V, Jelic M, Nikolic V, Jukic T, Hat J. Pneumatization of the middle nasal turbinate: a CT study. Lijec Vjesn 1998;120:200-1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kayalioglu G, Oyar O, Govsa F. Nasal cavity and paranasal sinus bony variations: a computed tomographic study. Rhinology 2000;38:108-13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Midilli R, Aladag G, Erginöz E, Karci B, Savas R. Anatomic variations of the paranasal sinuses detected by computed tomography and the relationship between variations and sex. Kulak Burun Bogaz Ihtis Derg 2005;14:49-56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Catalano PJ, Roffman EJ. Evaluation of middle meatal stenting after minimally invasive sinus techniques (MIST). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2003;128:875-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Anand VK, Tabaee A, Kacker A, Newman JG, Huang C. The role of mitomycin C in preventing synechia and stenosis after endoscopic sinus surgery. Am J Rhinol 2004;18:311-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lee JY, Lee SW. Preventing lateral synechia formation after endoscopic sinus surgery with a silastic sheet. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2007;133:776-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Shrime MG, Tabaee A, Hsu AK, Rickert S, Close LG. Synechia formation after endoscopic sinus surgery and middle turbinate medialization with and without FloSeal. Am J Rhinol 2007;21:174-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Del Rey-Santamaria M, Valmaseda Castellón E, Berini Aytés L, Gay Escoda C. Incidence of oral sinus communications in 389 upper thirmolar extraction. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2006;11:E334-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Rothamel D, Wahl G, d’Hoedt B, Nentwig GH, Schwarz F, Becker J. Incidence and predictive factors for perforation of the maxillary antrum in operations to remove upper wisdom teeth: prospective multicentre study. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2007;45:387-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Watzak G, Tepper G, Zechner W, Monov G, Busenlechner D, Watzek G. Bony press-fit closure of oro-antral fistulas: a technique for pre-sinus lift repair and secondary closure. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2005;63:1288-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Brook I. Sinusitis of odontogenic origin. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2006;135:349-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Güven O. A clinical study on oroantral fistulae. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 1998;26:267-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Aimetti M, Romagnoli R, Ricci G, Massei G. Maxillary sinus elevation: the effect of macrolacerations and microlacerations of the sinus membrane as determined by endoscopy. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 2001;21:581-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Aust R, Drettner B. Oxygen tension in the human maxillary sinus under normal and pathological conditions. Acta Otolaryngol 1974;78:264-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Perko M. Maxillary sinus and surgical movement of maxilla. Int J Oral Surg 1972;1:177-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Raghoebar GM, van Weissenbruch R, Vissink A. Rhino-sinusitis related to endosseous implants extending into the nasal cavity. A case report. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2004;33:312-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Schaefer SD, Manning S, Close LG. Endoscopic paranasal sinus surgery: indications and considerations. Laryngoscope 1989;99:1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Davis WE, Templer JW, LaMear WR. Patency rate of endoscopic middle meatus antrostomy. Laryngoscope 1991;101:416-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Tiwana PS, Kushner GM, Haug RH. Maxillary sinus augmentation. Dent Clin North Am 2006;50:409-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bhattacharyya N. Bilateral chronic maxillary sinusitis after the sinus-lift procedure. Am J Otolaryngol 1999;20:133-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lebowitz RA, Jacobs JB, Tavin ME. Safe and effective infundibulotomy technique. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1995;113:266-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Raghoebar GM, Vissink A. Treatment for an endosseous implant migrated into the maxillary sinus not causing maxillary sinusitis: case report. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2003;18:745-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Sugiura N, Ochi K, Komatsuzaki Y. Endoscopic extraction of a foreign body from the maxillary sinus. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2004;130:279-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Scorticati MC, Raina G, Federico M. Cluster-like headache associated to a foreign body in the maxillary sinus. Neurology 2002;59:643-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Biglioli F, Goisis M. Access to the maxillary sinus using a bone flap on a mucosal pedicle: preliminary report. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2002;30:255-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Nakamura N, Mitsuyasu T, Ohishi M. Endoscopic removal of a dental implant displaced into the maxillary sinus: technical note. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2004;33:195-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kim JW, Lee CH, Kwon TK, Kim DK. Endoscopic removal of a dental implant through a middle meatal antrostomy. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2007;45:408-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Felisati G, Lozza P, Chiapasco M, Borloni R. Endoscopic removal of an unusual foreign body in the sphenoid sinus: an oral implant. Clin Oral Implants Res 2007;18:776-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Kitamura A. Removal of a migrated dental implant from a maxillary sinus by transnasal endoscopy. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2007;45:410-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]