Abstract

Serotonin (5-HT) is known to play a role in the suppression of the lordosis response in males. We have previously shown that there is a sex difference in the density of 5-HT immunoreactive (5-HT-ir) fibers in the ventrolateral division of the adult ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus (VMNvl) and that neonatal administration of estradiol (E2) increases 5-HT-ir in the female VMNvl to male-typical levels. Here we demonstrate that postnatal administration of the ERα agonist 1,3,5-tris(4-Hydroxyphenyl)-4-propyl-1H-pyrazole (PPT), but not the ERβ agonist diarylpropionitrile (DPN), also masculinizes 5-HT-ir in the female VMNvl, suggesting a mechanistic role for ERα in this process. Sexual receptivity, as ascertained by the lordosis quotient, was unaffected by either PPT or DPN treatment but nearly abolished by estradiol benzoate (EB), a synthetic estrogen with high affinity for both ERα and ERβ. Collectively, these observations show that postnatal estrogens increase the density of 5-HT projections to the VMNvl via an ERα dependent mechanism, but that this increased inhibitory input is not sufficient to suppress the lordosis response.

Keywords: estrogen, development, hypothalamus, serotonin, sex differences, estrogen receptor, DPN, PPT

The ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus (VMN) is a critical component of multiple neuroendocrine and behavioral systems. The ventrolateral division of the VMN (VMNvl) is essential for the regulation of lordosis, a reflexive posture indicative of female sexual receptivity in rodents, as lesions to this nucleus severely impair or eliminate this behavior [25,31,41]. The steroid hormones 17β-estradiol (E2) and progesterone (P) play an essential role in facilitating the display of this behavior, but the neurotransmitter serotonin (5-HT) can also modulate lordosis [4,45,52]. We have recently shown that the density of serotonergic fibers projecting to the VMNvl is sexually dimorphic in adult rats, with males having a higher density than females. We also found that this sex difference can be eliminated by exposing females to 17β-estradiol (E2) during the neonatal period, demonstrating that this sex difference is organized by neonatal estrogens [38]. These observations led us to hypothesize that increased serotonergic input to the VMNvl may be a mechanism by which neonatal estrogen exposure results in impaired lordosis behavior in adulthood. The goals of the present study were to (1) identify which ER subtype mediates this robust increase in serotonergic VMNvl inputs by neonatally exposing female rats to agonists selective for each of the two major ER subforms (ERα and ERβ) and (2) to ascertain whether or not this elevated level of 5-HT innervation is concomitant with impaired lordosis behavior.

Serotonergic projections originating from the dorsal raphe nucleus in the brainstem (DRN) to forebrain nuclei, including the VMN actively suppress lordosis in males [13,14,29]. Lesions to this or an alternate pathway projecting through the lateral septum (LS) to the midbrain central gray (MCG) [6,16,51] can restore lordosis in males. Similarly, ablation of 5-HT inputs to the VMN from the DRN enhances the lordosis response in females [13,22]. Neonatal estrogens, aromatized from testicular androgens, have long been known to facilitate the masculinization of the male hypothalamus such that a lordosis response cannot be induced [8,48,55]. Similarly, neonatal estrogen administration functionally masculinizes the female rodent brain, thus rendering the female incapable of generating lordosis responses in adulthood [5,7,54]. Therefore, one mechanism by which lordosis might be actively suppressed in females neonatally exposed to estrogen is through increased inhibitory serotonergic input to the VMNvl from the DRN. The functional roles each of the two major ER subtypes, ERα and ERβ play in the organization of the serotonergic lordosis inhibiting pathway is not known.

There is growing support for the hypothesis that ERα and ERβ act sequentially during development to first, defeminize, then masculinize the male brain [44]. In this model, agonism of ERβ during the neonatal period defeminizes the male such that potential to generate a lordosis response in adulthood is eliminated. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that male mice lacking ERβ can be stimulated to engage in a low level of lordosis by the sequential administration of E2 and P [19], indicating that lordosis inhibition may not be properly developed in these animals. Similarly, neonatal administration of the ERβ selective agonist diarylpropionitrile (DPN) to female mice impairs the lordosis response [20]. These data support our hypothesis that ERβ plays a critical role in the organization of the lordosis inhibiting circuits in males. The mouse DRN contains more ERβ than ERα and over 90% of these ERβ neurons are co-localized with tryptophan hydroxylase, the rate-limiting enzyme for 5-HT synthesis [32]. Therefore it appears that ERβ agonism could influence both the development of the DRN derived lordosis-inhibiting circuit, and the functional activation of this circuit during adulthood.

The facilitatory effects of estrogens on the lordosis response in adult females appear to be exerted exclusively through ERα, as ERα knockout mice do not display lordosis, even after steroid hormone administration [33]. Prior work has also shown that administration of the ERα selective agonist 1,3,5-tris(4-Hydroxyphenyl)-4-propyl-1H-pyrazole (PPT) to adult ovariectomized females elicits both receptive and proceptive sexual behavior [27] while administration of the ERβ selective agonist DPN does not. An activational role for ERα is also supported by the observation that ERα is densely expressed in adult VMNvl while ERβ is not [46,47]. However, a role for ERα in the defeminization of lordosis behavior is suggested by the observation that neonatal administration of 3 mg coumestrol, a steroid-like phytoestrogen with a higher affinity for ERα than ERβ [11,21], ultimately suppresses lordosis behavior in the adult female rat [18]. In contrast, administration of 1 mg genistein, a phytoestrogen with a higher affinity for ERβ [21,39], did not affect lordosis behavior [18].

To delineate the relative roles ERα and ERβ play in the organization of serotonergic inputs to the VMNvl, female rats pups were administered either the synthetic estrogen estradiol benzoate (EB), which has a similar affinity for both ERα and ERβ, the ERα specific agonist PPT, the ERβ specific agonist DPN or a sesame oil vehicle daily for the first four days of life and raised to adulthood. The animals were then ovariectomized (OVX) as adults and sequentially administered estradiol benzoate (EB) and P. This treatment paradigm has previously been shown to effectively restore lordosis behavior in OVX females but not in females masculinized by neonatal exposure to estradiol or in males [30,36,48]. We therefore hypothesized that lordosis behavior would be impaired in the animals neonatally exposed to EB, DPN and/or PPT compared to the vehicle treated controls. Following the completion of behavioral testing, the animals were again hormone replaced and sacrificed to quantify 5-HT fiber density in the VMNvl using immunofluorescent techniques. Serotonergic projections to the VMNvl were hypothesized to be higher in the animals neonatally exposed to EB, DPN and/or PPT compared to the vehicle treated controls.

Experimental procedures were carried out in accordance with the applicable portions of the Animal Welfare Act and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” and approved by the North Carolina State University (NCSU) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Timed pregnant Long Evans rats (n = 10; Charles River, NC) were individually housed in a humidity and temperature controlled room with a standard 12-h light cycle at NCSU and maintained on a phytoestrogen-free diet (AIN-93G, Test Diet, Richmond, IN). Female pups were cross fostered on the day of birth and treated within 4-6 hours of birth. All female pups within a cross fostered litter were given the same treatment to avoid cross contamination. Some of the females were used for the present study (n = 6 - 9 per treatment group), and others were used for additional experiments [1].

Beginning on the day of birth, females were subcutaneously (sc) injected daily over 4 days with vehicle (0.05 ml), EB (50 μg, Sigma), the ERα agonist PPT (1 mg/kg bw, Tocris Biosciences, Ellisville, MS), or the ERβ agonist DPN (1 mg/kg bw, Tocris Biosciences). Doses were consistent with prior studies examining the effects of ER agonists on sexually dimorphic behavior and physiology in rodents [1,3,10,23]. All compounds were dissolved in ethanol, and then sesame oil (Sigma) at a ratio of 10% EtOH and 90% oil as we have done previously [37]. The vehicle was also prepared with this ratio. We have found that both DPN and PPT dissolve easily and stay in solution with this method and that this vehicle causes less skin irritation than DMSO. DPN has a 70-fold greater relative binding affinity and 170-fold greater relative potency in transcription assays for ERβ than ERα [28]. PPT has a 400-fold preference for ERα and minimal binding to ERβ [49,50]. At three weeks of age, all pups were weaned into littermate pairs, ear tagged, and maintained on a reverse light schedule (lights off from 10:00 to 22:00).

Animals were then OVX’d under isoflurane anesthesia on postnatal day 146, allowed 3 weeks to recover, and tested for sexual receptivity as described previously [36,39]. To induce sexual receptivity, the OVX females were sc injected with 10 μg EB, followed 48 hours later by a sc injection of 500 μg P (same vehicle as above) and paired with vigorous males four hours after P administration. All testing was conducted under red light, videotaped, and scored from the videotape using Stopwatch (courtesy of David A. Brown, Center for Behavioral Neuroscience, Emory University). Lordosis quotient was calculated by dividing the number of lordosis responses in each trial (10 min) by the number of mount attempts then multiplying the result by 100. Testing was then repeated after a two week recovery period. In five pairings (2 in round 1, 3 in round 2), the male made no attempt to mount the female. These trials were not included in the analysis. Differences in LQ were compared using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Fisher’s post hoc tests.

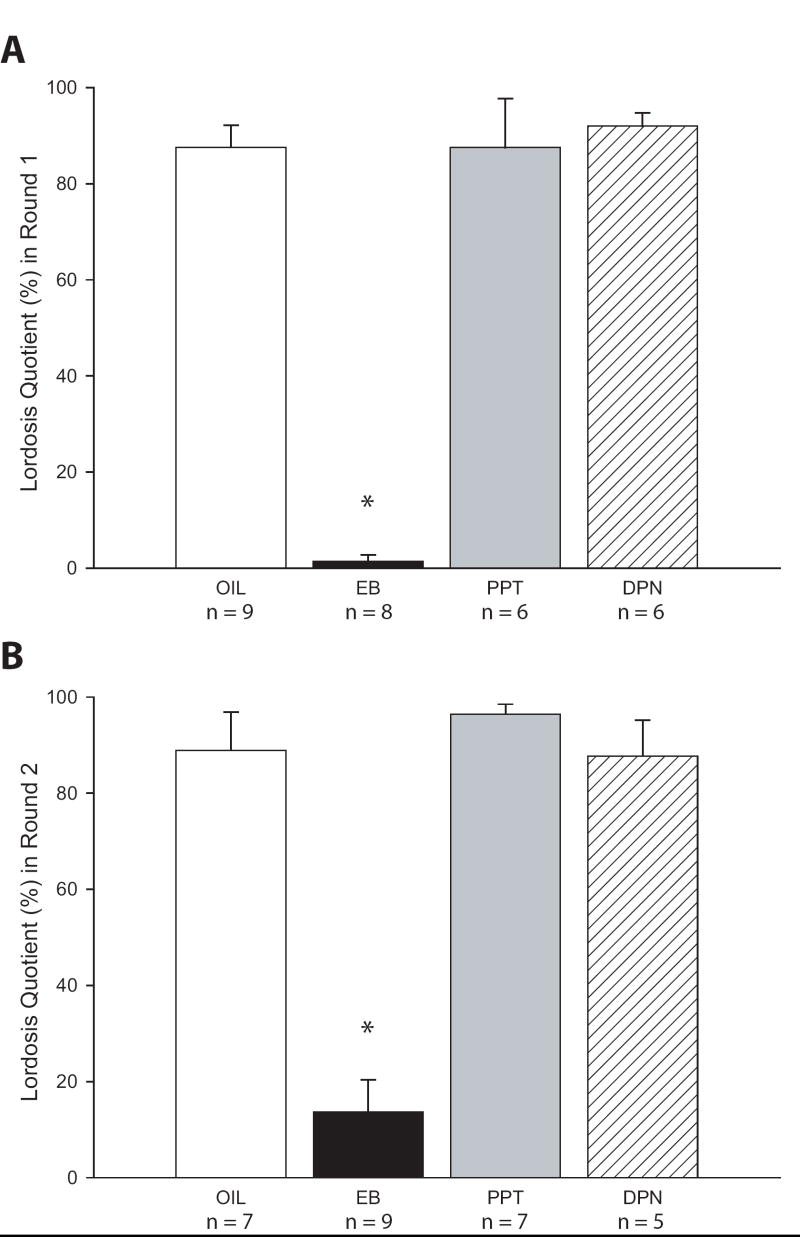

There was a significant main effect of treatment in the first (F(3,25) = 74.14, P ≤ 0.001) and second round of testing (F(3,24) = 14.052, P ≤ 0.001; Fig. 1). In both rounds, LQ was significantly lower in the EB treated group compared to the oil treated controls (P ≤ 0.001 in both rounds) but not significantly affected in either the PPT or DPN treated groups.

Figure 1.

Lordosis quotient, an indicator of female sexual receptivity, in the first (A) and second (B) round of behavioral testing. Lordosis behavior was significantly lower in the females neonatally treated with EB but unaffected by either of the ER selective ligands.

Two weeks after the second round of behavioral testing concluded, all animals were again sequentially injected with EB and P then sacrificed by transcardial perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde 6-8 hours after the P injection. Brains were removed, post-fixed, cryoprotected overnight, rapidly frozen, and stored at -80°C as described previously [38]. Brains were then sliced into 35 μm coronal sections, and divided into two series of alternating, free-floating alternating sections. One set of alternating sections from each female, comprising the entire length of the VMNvl along with anatomically matched sections collected from six untreated, age matched Long Evans males (obtained from other experiments [35]) were immunolabeled for 5-HT as we have done previously [38]. Briefly, the sections were incubated for 72 h at 4°C in a cocktail of primary antibodies directed against 5-HT (goat anti-serotonin, 1:6000 ImmunoStar, Hudson, WI), ERα (rabbit polyclonal anti-ERα C1355, 1:20,000, Upstate Biotechnology, Waltham, MA) and HuC/D (mouse anti-HuC/HuD 16A11, 1:500 Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in LKPBS. ERα was used to help define the borders of the VMNvl. HuC/D was used to visualize the borders of neuronal cell bodies [42]. After incubation and rinsing, the sections were then placed for 2 h in a cocktail of donkey secondary antibodies (1:200) generated against goat, rabbit and mouse IgGs (Alexa-Fluor donkey anti-goat 488, Alexa-Fluor donkey anti-rabbit 568, Alexa-Fluor donkey anti-mouse 647; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The sections were then rinsed, mounted onto slides (Superfrost Plus, Fisher) and coverslipped using a standard glycerol mountant.

Quantification of 5-HT immunostaining within one, midlevel section of the VMNvl per animal, was conducted as described in detail in our prior experiment [38]. Breifly, all selected sections were anatomically matched using a brain atlas [40] and only sections with consistent staining throughout the entire thickness were included in the analysis (n = 4-7 per group). 5-HT immunoreactivity (5-HT-ir) was visualized using a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta confocal microscope (housed at the Hamner Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC) fitted with a 63X oil-corrected objective lens. A set of serial image planes (z-step distance = 1 μm) was collected through the entire thickness of each section and analyzed using Image J (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). To control for variations in tissue thickness that would result in unequal numbers of image planes, substacks of 25 consecutive image planes were created for each set of scans. Using methods consistent with those described previously [38,43], individual images contained within each substack were binarized to a threshold selected to optimize visualization of the signal. Single pixels were removed to further reduce background influence. Fibers were then skeletonized to a thickness of one pixel to compensate for differences in individual fiber thickness and brightness. The number of bright pixels in each plane of the substack was then quantified using the Image J Voxel Counter plug-in. The voxel counts were then averaged within the substack to obtain a single measure that was used as a quantitative representation of the average density of labeling within the volume sampled.

To compare differences in 5-HT fiber density within the VMNvl, each treatment group (including the male group) was assigned a group number and analyzed using a one-tailed, ANOVA with the hypothesis that treatment would increase 5-HT-ir in the VMNvl and followed up with Fisher’s post hoc test.

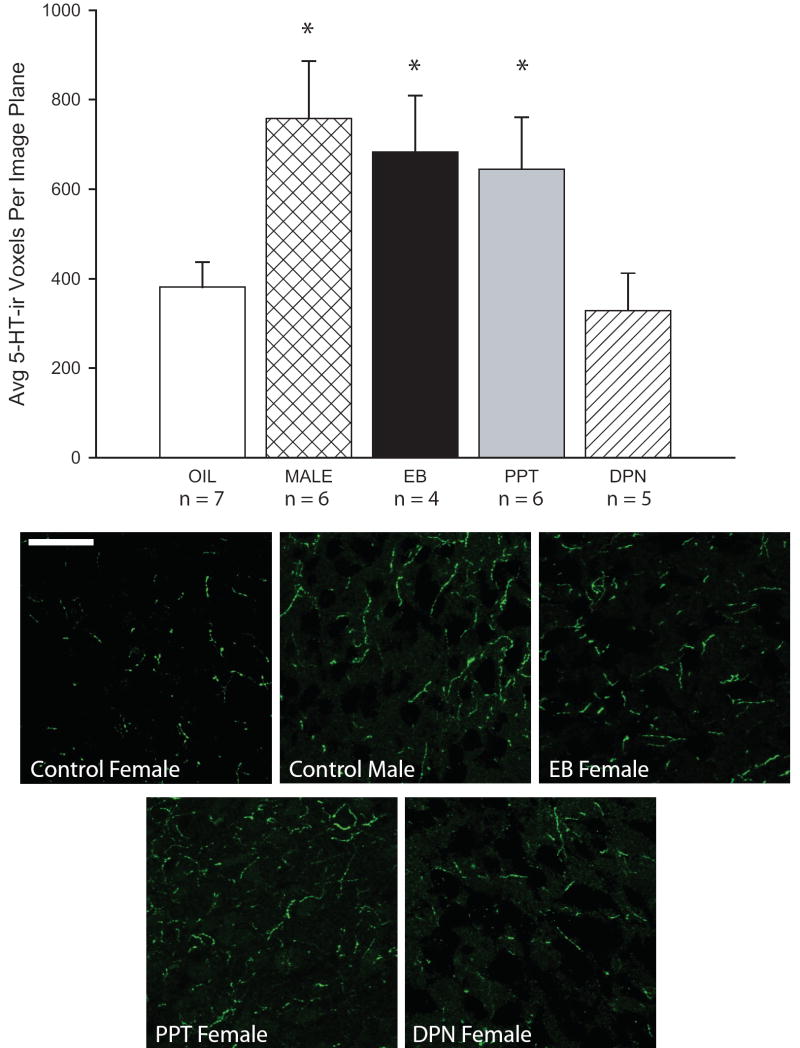

There was a main effect of treatment group (F(4,23) = 3.534, P ≤ 0.01) on 5-HT fiber density in the VMNvl (Fig. 2). 5-HT-ir was significantly higher in the control males (n = 6) compared to the control females (n = 7; P ≤ 0.01), a sex difference we have reported previously [38]. As expected, 5-HT-ir was significantly higher in the females postnatally treated with EB (n = 4) compared to the control females (P ≤ 0.03) and was not statistically different from the control males (P = 0.64). Females postnatally treated with the ERα agonist PPT (n = 6) had significantly more 5-HT-ir in the VMNvl than the control females (P ≤ 0.03), an amount that did not statistically differ from the control males (P ≤ 0.43). In contrast, postnatal treatment with DPN (n = 5) did not significantly affect 5-HT-ir (P = 0.72)

Figure 2.

Confocal images (4 merged optical planes) depicting 5-HT fiber content in the VMNvl. 5-HT labeling was readily observed within extended lengths of fibers. 5-HT immunoreactivity was significantly higher in the males than the control females and significantly increased in the females neonatally treated with EB or the ERα agonist PPT but not the ERβ agonist DPN. (*P ≤ 0.03; Scale bar (white) = 20 μm)

Our results clearly show that ERα, but not ERβ, plays a mechanistic role in the masculinization of 5-HT-ir in the VMNvl by postnatal estrogens. Intriguingly, increased VMNvl 5-HT-ir in the PPT treated females was not accompanied by a concomitant decrease in lordosis behavior. This disconnect between neuroanatomy and behavior could signify that the 5-HT immunolabeled fibers within the VMNvl of the PPT treated females are not a component of the DRN derived lordosis inhibiting circuit. Because, in both sexes, 5-HT projections principally originate from the DRN, it is reasonable to assume that the observed VMNvl 5-HT-ir fibers project from cell bodies within the DRN. However, it has recently been shown that the VMNvl also receives serotonergic inputs from the median raphe nuclei (MRN) [15], the functional significance of which remains to be determined. The increased density of 5-HT-ir fibers in the EB and PPT treated females could result from either increased axonal branching, leading to the formation of denser terminal fields in the VMNvl, or from an increased number of 5-HT cell bodies in the DRN or the MRN. Our data support the first of these possibilities because, of the two ER subtypes, the rodent raphe nuclei contain primarily ERβ while the VMN contains primarily ERα [32,46,47]. It is possible that neonatal administration of PPT stimulated branching of VMNvl serotonergic fibers in general, regardless of their functional role, or fibers that comprise a different pathway.

An alternative possibility is that the 5-HT-ir fibers in the masculinized females are indeed a component of the DRN derived lordosis inhibiting circuit but are not functionally inhibitory. This may be because the facilitative effects of ERα activation in the adult animal can not be overcome, or that the net effect of increased serotonergic projections to the VNMvl differs between males and females, a condition that may depend upon which 5-HT receptors are present. The modulation of serotonergic input to the VMNvl has previously been shown to influence the lordosis response in females, but this influence can be either facilitative or inhibitory depending on which 5-HT receptor system is activated. For example, 5-HT1A receptors exert an inhibitory influence [53], while the 5-HT2A/2C and 5-HT3 receptor systems enhance the intensity of the lordosis response [24,52,56]. Presumably, increased 5-HT-ir in the VMNvl indicates elevated 5-HT release, a possibility supported by a prior study which showed that extracellular VMN 5-HT levels are significantly higher in intact males compared to estrous females [9]. Therefore it is plausible that, although the density of serotonergic projections to the VMNvl was masculinized by neonatal PPT administration, the female-typical distribution or density of 5-HT receptors in the VMNvl was not, and thus the increased extracellular 5-HT actually acted to facilitate rather than inhibit the intensity of the lordosis display.

Neonatal administration of DPN did not affect either lordosis behavior or 5-HT-ir in the VMNvl. Therefore our findings do not support an organizational role for ERβ in the masculinization of lordosis inhibition in rats. This observation is consistent with a previous study, also in rats, which showed that administration of either 5 μg or 12.5 μg (approximately 0.6 and 1.6 mg/kg) of the ERβ selective agonist ZK 281738 (Schering AG, Berlin, Germany) every other day for the first 12 days of life did not affect lordosis in adulthood [34]. Collectively these data suggest that neonatal agonism of ERβ alone is insufficient to suppress lordosis in females. However, this does not rule out the possibility that an interaction between ERβ and ERα is required for effective suppression, a concept that has been recently reviewed in detail [26,44]. It is also plausible that agonism of ERβ in adulthood is needed to maintain lordosis inhibition in both sexes. Mazzucco and colleagues have shown that administration of the ERα agonist PPT, followed by P, to OVX females restores LQ to levels typically observed in gonadally intact females but DPN can damped this effect if given in conjunction with PPT [27]. An activational role of ERβ in the lordosis inhibiting system could also explain why mice lacking ERβ can be induced to lordose [19].

The lack of a PPT or DPN effect on lordosis could also signify that either the dose or the timing of administration was inadequate. Of these, inappropriate timing is unlikely because EB, given over the same time period, produced a robust effect on LQ. Equivalent (1 mg/kg) doses of PPT and DPN have been successfully used to affect estrogen sensitive physiology and behavior in adults [1,3,10,23] and we have recently reported that the same PPT and DPN neonatal administration paradigm used in the present study impairs other reproductive endpoints including the maintenance of a regular estrous cycle and the capacity to stimulate GnRH neuronal activation in response to EB and P priming [1]. The null effect of PPT on LQ conflicts with one prior study by Patchev and colleagues [34] which found that LQ was significantly lower in animals dosed with either 5 μg or 12.5 μg of the ERα selective agonist ZK281471 (Schering AG, Berlin, Germany) every other day for the first 12 days of life. The discrepancy in lordosis behavior between this prior study and the current study may be due to differences in the region-specific activity of the different ERα selective compounds within the brain, dose, or duration of exposure. It is also possible that neonatal exposure to PPT or DPN affects how sensitive the animal is to stimulation by estrogens and/or progesterone in adulthood. Similar studies using phytoestrogens have likewise yielded inconsistent results [2,12,17,18]. Further studies comparing different ERα and ERβ selective agonists over a range of doses in a consistent time frame are necessary to definitively determine if and when ERα and ERβ agonism in the neonatal period can impair female sexual receptivity, and uncover the specific mechanisms by which this occurs. However, it is clear from our data that enhanced serotonergic input to the VMNvl cannot be the mechanism by which neonatal agonism of ERα suppresses lordosis in females.

We have previously shown that there is a sex difference in the density of 5-HT-ir fibers in the adult VMNvl and that neonatal administration of E2 increases 5-HT-ir in the female VMNvl to male-typical levels [38]. Here we have replicated that finding, and further demonstrated that postnatal administration of the ERα agonist PPT, but not the ERβ agonist DPN, also masculinizes 5-HT-ir in the female VMNvl, suggesting a mechanistic role for ERα in this process. Collectively, these observations demonstrate that postnatal estrogen exposure increases the density of sexually dimorphic 5-HT projections to the VMNvl via an ERα dependent mechanism, but that this enhanced serotonergic input to the female VMNvl may not be functionally inhibitory or at least is not sufficiently effective to suppress sexual receptivity.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Victoria Wong for her assistance with the confocal microscopy at the Hamner Institute in Research Triangle Park, NC. We also greatly appreciate the work of Linda Hester and Barbara J. Welker and the entire animal care staff at the Biological Research Facility at NCSU for their outstanding support with animal husbandry and care. This work was supported by NIEHS grant 1R01ES016001-01 to H.B. Patisaul.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bateman HL, Patisaul HB. Disrupted female reproductive physiology following neonatal exposure to phytoestrogens or estrogen specific ligands is associated with decreased GnRH activation and kisspeptin fiber density in the hypothalamus. Neurotoxicology. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2008.06.008. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Csaba G, Karabelyos C. Effect of single neonatal treatment with the soy bean phytosteroid, genistein on the sexual behavior of adult rats. Acta Physiol Hung. 2002;89:463–70. doi: 10.1556/APhysiol.89.2002.4.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frasor J, Barnett DH, Danes JM, Hess R, Parlow AF, Katzenellenbogen BS. Response-specific and ligand dose-dependent modulation of estrogen receptor (ER) alpha activity by ERbeta in the uterus. Endocrinology. 2003;144:3159–66. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-0143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frye CA. The role of neurosteroids and non-genomic effects of progestins and androgens in mediating sexual receptivity of rodents. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2001;37:201–22. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00119-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerall AA. Effects of early postnatal androgen and estrogen injections on the estrous activity cycles and mating behavior of rats. Anat Rec. 1967;157:97–104. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091570114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gordon JH, Nance DM, Wallis CJ, Gorski RA. Effects of septal lesions and chronic estrogen treatment on dopamine, GABA and lordosis behavior in male rats. Brain Res Bull. 1979;4:85–9. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(79)90062-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gorski RA. Modification of ovulatory mechanisms by postnatal administration of estrogen to the rat. Am J Physiol. 1963;205:842–4. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1963.205.5.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gorski RA. Sexual dimorphisms of the brain. J Anim Sci. 1985;61(Suppl 3):38–61. doi: 10.1093/ansci/61.supplement_3.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gundlah C, Simon LD, Auerbach SB. Differences in hypothalamic serotonin between estrous phases and gender: an in vivo microdialysis study. Brain Res. 1998;785:91–6. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01391-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris HA, Katzenellenbogen JA, Katzenellenbogen BS. Characterization of the biological roles of the estrogen receptors, ERalpha and ERbeta, in estrogen target tissues in vivo through the use of an ERalpha-selective ligand. Endocrinology. 2002;143:4172–7. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacob DA, Temple JL, Patisaul HB, Young LJ, Rissman EF. Coumestrol antagonizes neuroendocrine actions of estrogen via the estrogen receptor α. Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. 2001;226:301–306. doi: 10.1177/153537020122600406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jefferson WN, Padilla-Banks E, Newbold RR. Disruption of the female reproductive system by the phytoestrogen genistein. Reprod Toxicol. 2007;23:308–16. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2006.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kakeyama M, Umino A, Nishikawa T, Yamanouchi K. Decrease of serotonin and metabolite in the forebrain and facilitation of lordosis by dorsal raphe nucleus lesions in male rats. Endocr J. 2002;49:573–9. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.49.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kakeyama M, Yamanouchi K. Two types of lordosis-inhibiting systems in male rats: dorsal raphe nucleus lesions and septal cuts. Physiol Behav. 1994;56:189–92. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)90278-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kanno K, Shima S, Ishida Y, Yamanouchi K. Ipsilateral and contralateral serotonergic projections from dorsal and median raphe nuclei to the forebrain in rats: immunofluorescence quantitative analysis. Neurosci Res. 2008;61:207–18. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kondo Y, Shinoda A, Yamanouchi K, Arai Y. Role of septum and preoptic area in regulating masculine and feminine sexual behavior in male rats. Horm Behav. 1990;24:421–34. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(90)90019-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kouki T, Kishitake M, Okamoto M, Oosuka I, Takebe M, Yamanouchi K. Effects of neonatal treatment with phytoestrogens, genistein and daidzein, on sex difference in female rat brain function: estrous cycle and lordosis. Horm Behav. 2003;44:140–5. doi: 10.1016/s0018-506x(03)00122-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kouki T, Okamoto M, Wada S, Kishitake M, Yamanouchi K. Suppressive effect of neonatal treatment with a phytoestrogen, coumestrol, on lordosis and estrous cycle in female rats. Brain Res Bull. 2005;64:449–54. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kudwa AE, Bodo C, Gustafsson JA, Rissman EF. A previously uncharacterized role for estrogen receptor beta: defeminization of male brain and behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:4608–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500752102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kudwa AE, Michopoulos V, Gatewood JD, Rissman EF. Roles of estrogen receptors alpha and beta in differentiation of mouse sexual behavior. Neuroscience. 2006;138:921–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuiper GGJM, Lemmen JG, Carlsson B, Corton JC, Safe SH, Van Der Saag PT, Van Der Berg B, Gustafsson JA. Interaction of estrogenic chemicals and phytoestrogens with estrogen receptor β. Endocrinology. 1998;139:4252–4263. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.10.6216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luine VN, Frankfurt M, Rainbow TC, Biegon A, Azmitia E. Intrahypothalamic 5,7-dihydroxytryptamine facilitates feminine sexual behavior and decreases [3H]imipramine binding and 5-HT uptake. Brain Res. 1983;264:344–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90839-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lund TD, Rovis T, Chung WC, Handa RJ. Novel actions of estrogen receptor-beta on anxiety-related behaviors. Endocrinology. 2005;146:797–807. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maswood N, Caldarola-Pastuszka M, Uphouse L. Functional integration among 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor families in the control of female rat sexual behavior. Brain Res. 1998;802:98–103. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00554-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mathews D, Greene SB, Hollingsworth EM. VMN lesion deficits in lordosis: partial reversal with pergolide mesylate. Physiol Behav. 1983;31:745–8. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(83)90269-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matthews J, Gustafsson JA. Estrogen signaling: a subtle balance between ER alpha and ER beta. Mol Interv. 2003;3:281–92. doi: 10.1124/mi.3.5.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mazzucco C, Walker H, Pawluski J, Leiblich S, Galea L. ERalpha, but not ERbeta, mediates the expression of sexual behavior in the female rat. Behav Brain Res. 2008;191:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meyers MJ, Sun J, Carlson KE, Marriner GA, Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA. Estrogen receptor-beta potency-selective ligands: structure-activity relationship studies of diarylpropionitriles and their acetylene and polar analogues. J Med Chem. 2001;44:4230–51. doi: 10.1021/jm010254a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moreines J, Kelton M, Luine VN, Pfaff DW, McEwen BS. Hypothalamic serotonin lesions unmask hormone responsiveness of lordosis behavior in adult male rats. Neuroendocrinology. 1988;47:453–8. doi: 10.1159/000124949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moreines J, McEwen B, Pfaff D. Sex differences in response to discrete estradiol injections. Horm Behav. 1986;20:445–451. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(86)90006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nance DM, Christensen LW, Shryne JE, Gorski RA. Modifications in gonadotropin control and reproductive behavior in the female rat by hypothalamic and preoptic lesions. Brain Res Bull. 1977;2:307–12. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(77)90087-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nomura M, Akama KT, Alves SE, Korach KS, Gustafsson JA, Pfaff DW, Ogawa S. Differential distribution of estrogen receptor (ER)-alpha and ER-beta in the midbrain raphe nuclei and periaqueductal gray in male mouse: Predominant role of ER-beta in midbrain serotonergic systems. Neuroscience. 2005;130:445–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ogawa S, Eng V, Taylor J, Lubahn DB, Korach KS, Pfaff DW. Roles of estrogen receptor-alpha gene expression in reproduction- related behaviors in female mice. Endocrinology. 1998;139:5070–81. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.12.6357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patchev AV, Gotz F, Rohde W. Differential role of estrogen receptor isoforms in sex-specific brain organization. Faseb J. 2004;18:1568–70. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1959fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patisaul HB, Bateman HL. Neonatal exposure to endocrine active compounds or an ERbeta agonist increases adult anxiety and aggression in gonadally intact male rats. Horm Behav. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patisaul HB, Dindo M, Whitten PL, Young LJ. Soy isoflavone supplements antagonize reproductive behavior and ERα- and ERβ- dependent gene expression in the brain. Endocrinology. 2001;142:2946–2952. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.7.8241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patisaul HB, Fortino AE, Polston EK. Neonatal genistein or bisphenol-A exposure alters sexual differentiation of the AVPV. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2006;28:111–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patisaul HB, Fortino AE, Polston EK. Sex differences in serotonergic but not gamma-aminobutyric acidergic (GABA) projections to the rat ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus. Endocrinology. 2008;149:397–408. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patisaul HB, Melby M, Whitten PL, Young LJ. Genistein affects ERβ- but not ERα-dependent gene expression in the hypothalamus. Endocrinology. 2002;143:2189–2197. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.6.8843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates : [the new coronal set] London: Elsevier Academic; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pfaff DW, Sakuma Y. Deficit in the lordosis reflex of female rats caused by lesions in the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus. J Physiol. 1979;288:203–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Polston EK, Gu G, Simerly RB. Neurons in the principal nucleus of the bed nuclei of the stria terminalis provide a sexually dimorphic GABAergic input to the anteroventral periventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. Neuroscience. 2004;123:793–803. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Polston EK, Simerly RB. Sex-specific patterns of galanin, cholecystokinin, and substance P expression in neurons of the principal bed nucleus of the stria terminalis are differentially reflected within three efferent preoptic pathways in the juvenile rat. J Comp Neurol. 2003;465:551–9. doi: 10.1002/cne.10841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rissman EF. Roles of oestrogen receptors alpha and beta in behavioural neuroendocrinology: beyond Yin/Yang. J Neuroendocrinol. 2008;20:873–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01738.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rissman EF, Wersinger SR, Fugger HN, Foster TC. Sex with knockout models: behavioral studies of estrogen receptor alpha. Brain Res. 1999;835:80–90. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01452-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shughrue P, Merchenthaler I. Distribution of estrogen receptor beta immunoreactivity in the rat central nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 2001;436:64–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shughrue PL, Lane MV, Merchenthaler I. Comparative distribution of estrogen receptor α and β mRNA in the rat central nervous system. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1997;388:507–525. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19971201)388:4<507::aid-cne1>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sodersten P. Effects of anti-oestrogen treatment of neonatal male rats on lordosis behaviour and mounting behaviour in the adult. J Endocrinol. 1978;76:241–9. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0760241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stauffer SR, Coletta CJ, Tedesco R, Nishiguchi G, Carlson K, Sun J, Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA. Pyrazole ligands: structure-affinity/activity relationships and estrogen receptor-alpha-selective agonists. J Med Chem. 2000;43:4934–47. doi: 10.1021/jm000170m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sun J, Huang YR, Harrington WR, Sheng S, Katzenellenbogen JA, Katzenellenbogen BS. Antagonists selective for estrogen receptor alpha. Endocrinology. 2002;143:941–7. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.3.8704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tsukahara S, Yamanouchi K. Neurohistological and behavioral evidence for lordosis-inhibiting tract from lateral septum to periaqueductal gray in male rats. J Comp Neurol. 2001;431:293–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Uphouse L. Female gonadal hormones, serotonin, and sexual receptivity. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2000;33:242–57. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(00)00032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Uphouse L, Montanez S, Richards-Hill R, Caldarola-Pastuszka M, Droge M. Effects of the 5-HT1A agonist, 8-OH-DPAT, on sexual behaviors of the proestrous rat. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1991;39:635–40. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(91)90139-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Whalen RE, Nadler RD. Suppression of the development of female mating behavior by estrogen administered in infancy. Science. 1963;141:273–4. doi: 10.1126/science.141.3577.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Whales RE, Gladue BA, Olsen KL. Lordotic behavior in male rats: genetic and hormonal regulation of sexual differentiation. Horm Behav. 1986;20:73–82. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(86)90030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wolf A, Caldarola-Pastuszka M, Uphouse L. Facilitation of female rat lordosis behavior by hypothalamic infusion of 5-HT(2A/2C) receptor agonists. Brain Res. 1998;779:84–95. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01082-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]