Abstract

Confinement of the obligate intracellular bacterium Chlamydia trachomatis to a membrane-bound vacuole, termed an inclusion, within infected epithelial cells neither prevents secretion of chlamydial antigens into the host cytosol nor protects chlamydiae from innate immune detection. However, the details leading to chlamydial antigen presentation are not clear. By immunoelectron microscopy of infected endometrial epithelial cells and in isolated cell secretory compartments, chlamydial major outer membrane protein (MOMP), lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and the inclusion membrane protein A (IncA) were localized to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and co-localized with multiple ER markers, but not with markers of the endosomes, lysosomes, Golgi nor mitochondria. Chlamydial LPS was also co-localized with CD1d in the ER. Since the chlamydial antigens, contained in everted inclusion membrane vesicles, were found within the host cell ER, these data raise additional implications for antigen processing by infected uterine epithelial cells for classical and non-classical T cell antigen presentation.

Keywords: Chlamydia trachomatis, Inclusion membrane protein (Inc), lipopolysaccharide (LPS), Endoplasmic reticulum, Antigen presentation

1. Introduction

Chlamydia trachomatis serovars D-K are the leading cause of bacterial sexually transmitted disease (STD) in the USA and worldwide. Chlamydial infection and propagation rely upon a developmental cycle during which an extracellular, infectious form termed the elementary body (EB) gains entry into the host genital mucosal epithelial cell before differentiating into an intracellular, metabolically-active reticulate body (RB). Inside the host cell, RB replicate by binary fission within a membrane-bound vacuole termed an inclusion. Redifferentiation of RB back into EB prepares the infectious progeny for release, through a mechanism recently shown to involve two pathways: host cell lysis and inclusion extrusion [1,2].

Vital to chlamydial pathogenesis is the establishment of an intracellular niche that avoids immune detection for the duration of host cell occupancy. To achieve this residency, the chlamydial EB-containing endosome quickly dissociates from the endocytic-lysosomal pathway and intersects the exocytic pathway, during which Chlamydia exploits numerous intracellular trafficking pathways to acquire amino acids, nucleotides and lipids from the host cell. The late endocytic pathway has been implicated in the delivery of biosynthetic precursors to the chlamydial inclusion via multivesicular bodies [3] and lipid droplets have been shown to translocate to the inclusion lumen to associate with RB [4]. Finally, Al Younes and colleagues [5] have proposed an association between Chlamydia and the autophagic pathway.

Epithelial cells in the genital tract are gaining recognition for their innate immune capabilities [6]. Human endometrial cells exhibit both MHC Class I (MHC-I) and Class II (MHC-II) expression and antigen presentation, secrete and respond to cytokines, and express Toll-like receptors. While chlamydial infection induces adaptive immune protection that involves both humoral and cellular responses [7], C. trachomatis also employs several strategies to evade the immune system. Our laboratory previously reported the formation of chlamydial antigen-containing vesicles everting from the inclusion [8]. These everted vesicles were identified as arising from the inclusion membrane by the presence of the Chlamydia-specific incorporated IncA and absence of markers specific for Golgi, lysosomes or endosomes and they contained several selected immunodominant chlamydial antigens, including the MOMP, LPS and chlamydial heat shock protein 60 (cHsp60) homologs 2 and 3 but not 1 nor histone protein 1 (HC-1). Conversely, Golgi vesicles were devoid of IncA markers and chlamydial envelope blebs. While some of these extra-inclusion antigen vesicles traffic to the host cell surface, others remain intracellular where they may influence vital host functions and antigen trafficking and presentation. Interestingly, elegant studies in the Subtil laboratory have implied the possibility of fusion events between the ER and the inclusion membrane via the SNARE-like fusion properties of IncA [9]. Since the ER is central to antigen processing and presentation and has been linked experimentally to chlamydial IncA, this organelle is an intriguing destination for chlamydial antigens.

The present study examines the host cellular localization of chlamydial antigens, particularly MOMP, LPS and IncA, within C. trachomatis-infected human endometrial epithelial cells. Using density gradient centrifugation for isolation of epithelial secretory pathway compartments and high resolution immunoelectron microscopy, the study associates these chlamydial antigens with the ER of infected endometrial epithelial cells, a finding that has implications for host cell antigen processing and presentation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell culture systems, growth of Chlamydia and chlamydial infection of polarized cells

The human endometrial carcinoma subclone 1B cell line (HEC-1B; HTB-113; ATCC) was maintained at 37 °C in Minimal Essential Medium (MEM) containing Hank’s salts (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Hyclone) and 2mM glutamine. The HEC-1B cells were grown to polarization in two culture systems: (i) on extracellular-matrix (ECM) coated filters (BioCoat Matrigel Invasive Chambers, 0.3 cm2, BD Biosciences) cultivated in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle MEM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.3 (DMEM) and maintained at 35 °C in an atmosphere of 5% carbon dioxide, and (ii) on collagen-coated DEAE-Sephadex beads (Cytodex 3 microcarrier beads; Sigma) in 500mL spinner flasks as described previously [10].

A human urogenital isolate C. trachomatis E/UW-5/CX was used in these experiments. Standardized inocula of C. trachomatis infectious EB were prepared from HEC-1B cells grown on Cytodex microcarrier beads. Progeny EB were harvested, titrated for infectivity, and stored at -80 °C. Polarized HEC-1B cell monolayers on ECM-coated filters and on beads were inoculated with C. trachomatis EB as described previously [8]. For experiments in the present study, host cells were infected for 48 hours in the absence of antibiotics.

2.2. Endoplasmic reticulum isolation

Major intracellular organelles of the secretory pathway, including Golgi, smooth ER and rough ER were separated using an Endoplasmic Reticulum Isolation Kit (Sigma). Briefly, uninfected and C. trachomatis-infected HEC-1B cells grown in bead culture were dounce homogenized and subjected to a series of centrifugation steps to pellet the beads, cell nuclei, mitochondria and microsomes. In infected cells, removal of intact EB and RB was confirmed by (i) Western blot antibody probing for HC1 and cHsp60-1 and (ii) the absence of chlamydial forms in the fractions processed for transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The microsomal fraction was separated into Golgi, smooth ER and rough ER using the gradient medium Iodixanol. Sixteen 500 μl fractions were collected from the top of the gradient downward with a syringe.

2.3. Western immunoblotting

Fractions from the Iodixanol gradients were solubilized in Laemmli buffer with protease inhibitors (Sigma) and equal amounts of protein were determined by the RC/DC assay (Bio-Rad). Fractions were paired and proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE using 4-12% Bis-Tris gradient gels and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes for Western blot analysis. The membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) before primary antibody incubation. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse, goat anti-rabbit and rabbit anti-goat second-affinity antibodies (Pierce) were used prior to chemiluminescent detection (Pierce). Standard protein size markers (Bio-Rad) were used to confirm molecular weights of target proteins.

2.4. Antibodies

Chlamydial markers used in this study included (1) monoclonal antibodies directed against IncA (Dr. Dan Rockey, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR), MOMP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and LPS (Virostat); (2) rabbit polyclonal antibodies directed against cHsp60-1 (Dr. Jane Raulston, East Tennessee State University, Johnson City, TN), IncA (via Dr. Rockey), HC1 (Dr. Ted Hackstadt, Rocky Mountain Laboratories, MT) and LPS (Cortex Biochem) and (3) goat polyclonal antibodies directed against MOMP (Biodesign International). Eukaryotic host cell markers used in this study included (1) monoclonal antibodies directed against Pan-cadherin (Abcam), EEA-1, LAMP1, PDI, GM130, BiP/GRP78 (BD Biosciences), MTC02 (Novus Biologicals), calnexin (Chemicon International), ERp57 (Novus Biologicals) and (2) rabbit polyclonal antibodies directed against calnexin (Dr. Daniel Hebert, Yale University, New Haven, CT), Sec61 alpha, ERp57, LAMP2 (Affinity Bioreagents), TAP I (Novus Biologicals), TGN38 and CD1d (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

2.5. Transmission electron microscopy

The C. trachomatis-infected HEC-1B cell monolayers grown on filters were processed and embedded in Epon-araldite for high contrast or in Lowicryl resin (Polysciences) for immunoelectron microscopy [8]. The crude microsomal pellet was resuspended in isolation buffer (Sigma) for negative staining. A volume of 5 μl was pipetted onto formvar-coated copper grids and allowed to adhere for 2 min before excess sample was removed by touching the grid with filter paper. The grids were washed three times with 10μl distilled water and air-dried. Then, 10 μl of 2% phosphotungstic acid was pipetted onto each grid, which was allowed to stand for 30 sec before the excess was removed using filter paper. For gradient section preparation, gradient fractions 7-10 were combined, mixed with 5 vol of PBS and pelleted by centrifugation at 150,000 g for 90 min at 4 °C. The pellets were processed and embedded by the same procedure used for filters [8]. Ultrathin sections were prepared using a Reichert Ultracut S microtome (Leica). For immunoelectron microscopy, 80-nm-sections were blocked with 1% ovalbumin/0.01M glycine in PBS for 5 min and incubated with the primary antibody for 40 min at 37 °C. Sections were washed with PBS and probed with the appropriate 5 or 15 nm colloidal gold-conjugated second-affinity antibody (Amersham Biosciences) for 30 min at 37 °C. Sections were washed with PBS and distilled water prior to staining with 4% uranyl acetate prepared in 50% ethanol. For double labeling, the second primary antibody was administered following the last PBS wash and the procedure was repeated. All labeling experiments were conducted in parallel with controls using an irrelevant primary antibody or a gold-labeled second-affinity antibody alone to determine background cross-reactivity. All chlamydial antigens were tested on uninfected cells to determine cross-reactivity. Thin sections on grids were examined in a Phillips Tecnai-10 electron microscope (FEI) operated at 80 kV. For quantitation of the immuno-EM data, multiple images (>600 total in this study; >50 per comparison; 50-100 gold particles per comparison) were captured, converted to TIFF files and printed; randomly selected 4-μm square fields containing infected host cell cytosol or isolated microsomes were scored positive or negative based on localization/co-localization of designated marker(s). Only fields containing morphologically identifiable organelles were scored, with a positive score requiring presence of both chlamydial and organelle markers within/on the distinguishable organelle. In total, over 600 micrographs were analyzed and more than 800 gold particles were counted. P values were obtained using the Student’s t-test and the data were converted to percentages for graphical representation.

3. Results

3.1. Ultrastructural localization of chlamydial antigens within tracts of ER

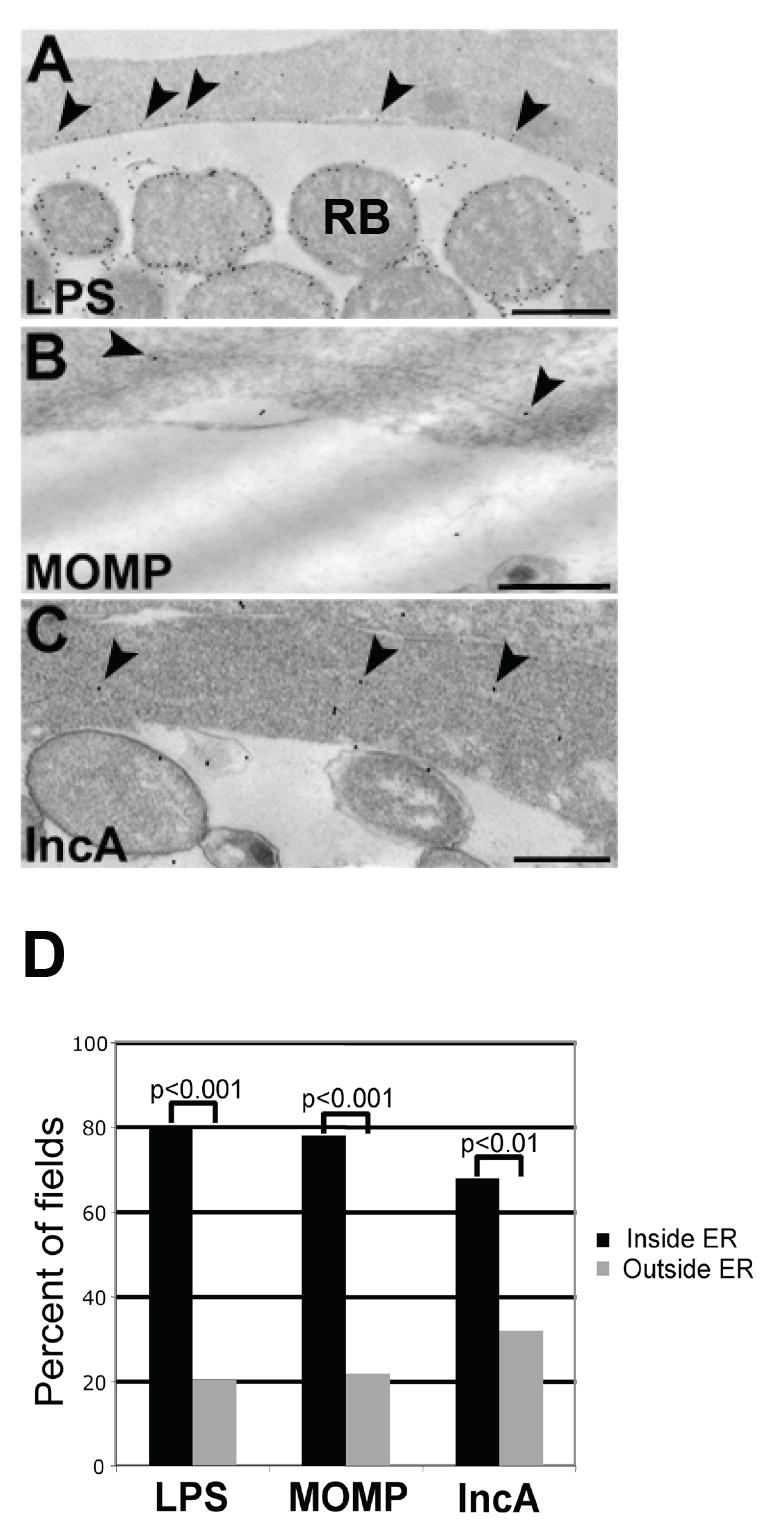

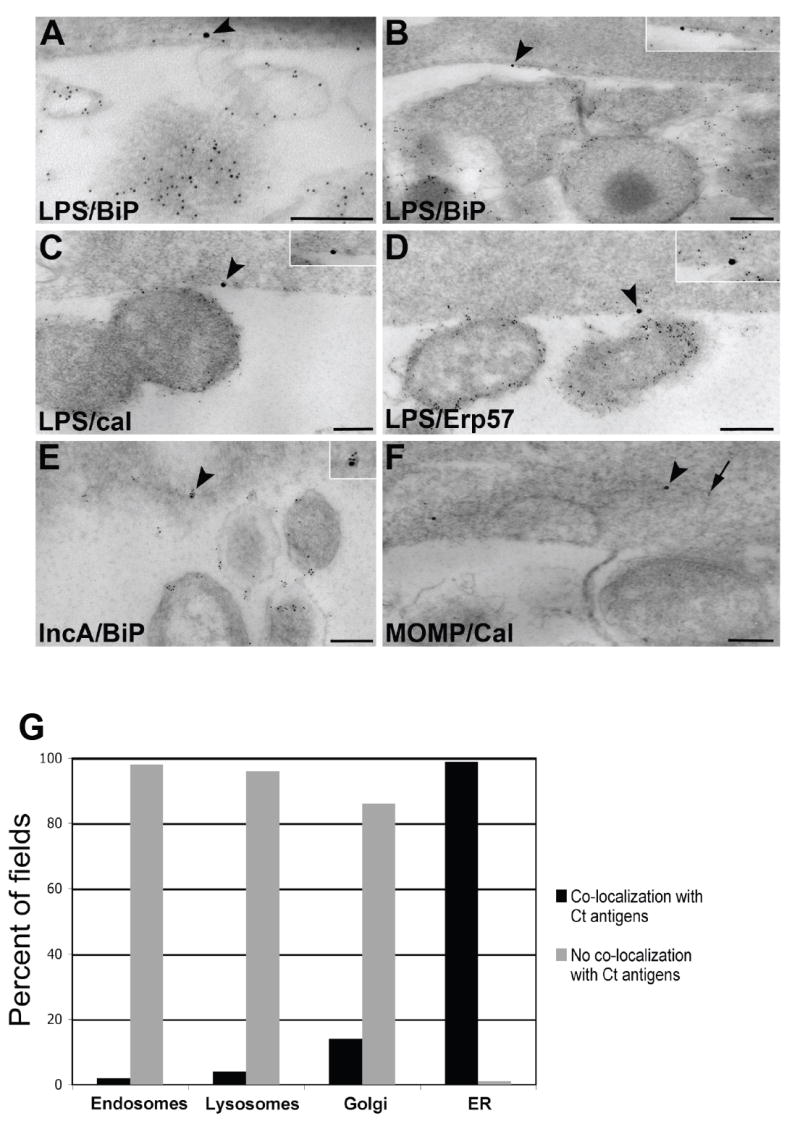

In-depth immunoelectron microscopic examination of C. trachomatis-infected polarized HEC-1B cells at 48 hours post-infection (hpi) revealed the presence of chlamydial antigens localizing along the exterior of the inclusion and, in some cases, within host cell cytosolic tracts morphologically distinctive of the ER. Second affinity gold-conjugated antibodies detected primary anti-IncA polyclonal antibodies, anti-LPS polyclonal antibodies and anti-MOMP monoclonal antibodies localizing their respective antigens adjacent to the chlamydial inclusion membrane, frequently appearing in tracts of ER (Fig. 1A-C). Quantitation analysis corroborated a strong association between finding chlamydial antigens within visible ER tracts versus elsewhere in the infected host cell cytosol, as indicated by the statistical significance (p<0.01; Figure 1D). Similarly, the ER luminal markers BiP/GRP78, ERp57 and calnexin all displayed a propensity for labeling at or near the inclusion membrane region in multiple samples and were often observed in areas positive for chlamydial LPS, MOMP and IncA (p<0.001); because ER tracts are commonly convoluted, representative high resolution examples are illustrated in Figure 2. Importantly, additional numerous control double-labeling experiments revealed no co-localization (p<0.001) between chlamydial LPS, MOMP and IncA with endosomes (EEA-1), lysosomes (LAMP1 and LAMP2) and Golgi (GM130 and TGN38) (Figure 2G).

Fig. 1.

Ultrastructural localization of chlamydial antigens to the host cell endoplasmic reticulum (ER). HEC-1B cells infected with C. trachomatis serovar E for 48 hr were prepared for post-embedding immunoelectron microscopy. (A-C) Chlamydial LPS (A), MOMP (B) and IncA (C) were detected in host cell cytosolic tracts characteristic of ER (arrowheads). Scale bars, 500 nm. (D) Multiple images (>50 fields per chlamydial antigen) of infected cells with visible ER tracts were examined for the presence or absence of each chlamydial marker. Percentages were calculated for graphical representation and levels of significance are indicated by p-values.

Fig. 2.

Ultrastructural co-localization between chlamydial antigens and host cell ER markers. HEC-1B cells infected with C. trachomatis E for 48 h were prepared for post-embedding immunoelectron microscopy. (A-D) Co-localization between chlamydial LPS (5 nm gold; arrow) and the ER markers BiP/GRP78 (A and B), calnexin (C) and Erp57 (D; 15 nm gold; arrowheads; magnified in insets). Scale bars, 200 nm. (E) Co-localization between chlamydial IncA (5 nm gold) and the ER marker BiP/GRP78 (15 nm gold; arrowhead, magnified in inset). Scale bar, 200 nm. (F) Co-localization between chlamydial MOMP (5 nm gold; arrow) and the ER marker calnexin (15 nm gold; arrowhead). Scale bar, 200 nm. (G) Quantitation of the co-localization between chlamydial antigens and host cell organelles. Multiple images (>50 fields per host cell organelle) were examined and percentages calculated for graphical representation. Levels of significance (all p-values<0.001) indicate co-localization of chlamydial antigens with the ER, but not with endosomes, lysosomes nor Golgi.

3.2. A potential mechanism of delivery for chlamydial antigens to the host cell ER

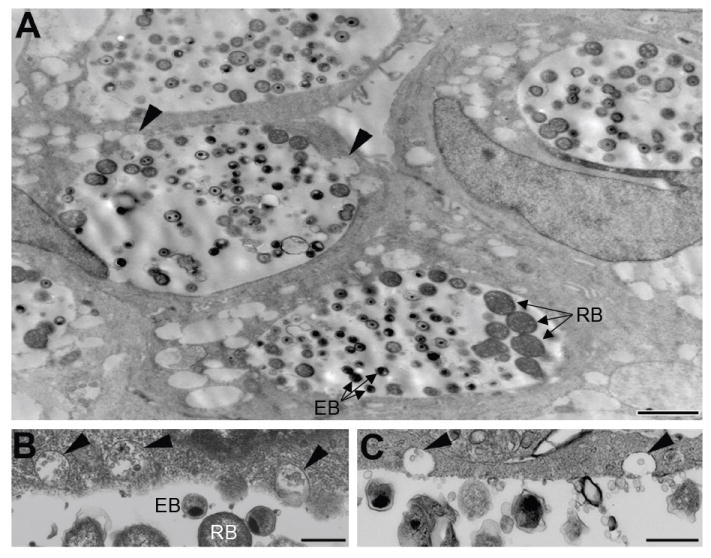

Previous studies in our laboratory noted numerous vesicles exterior to the chlamydial inclusion within the host cell cytosol in infected HEC-1B cells; these vesicles contained chlamydial outer membrane vesicles (OMV) that labeled positive, by immunoelectron microscopy, for several chlamydial antigens including MOMP and LPS [8]. It was discovered that these vesicles originated by eversion or pinching off from the inclusion membrane as they contained IncA. Since these vesicles were also prevalent in the present study (Fig. 3), it was hypothesized these chlamydial antigen OMV-containing (Fig. 3B and C) everted inclusion membrane vesicles (Fig. 3A, arrowheads) might traffic to and fuse with the ER, thereby delivering the cytosolic protease-protected antigens directly into the ER. To test this hypothesis, cytosolic vesicles and secretory components were isolated from infected cells and examined for co-localization with chlamydial IncA, MOMP and LPS.

Fig. 3.

Ultrastructural identification of extra-inclusion vesicles in C. trachomatis-infected human endometrial epithelial cells. (A) The appearance of extra-inclusion vesicles within the infected HEC-1B cell cytosol at 48 h. Some vesicles were observed everting from the inclusion (arrowheads). Scale bar, 2 μm. (B and C) The contents of the extra-inclusion vesicles (arrowheads) resemble outer membrane blebs found within the inclusion. Scale bars, 500 nm.

3.3. Co-localization of chlamydial antigens and ER markers following ER isolation

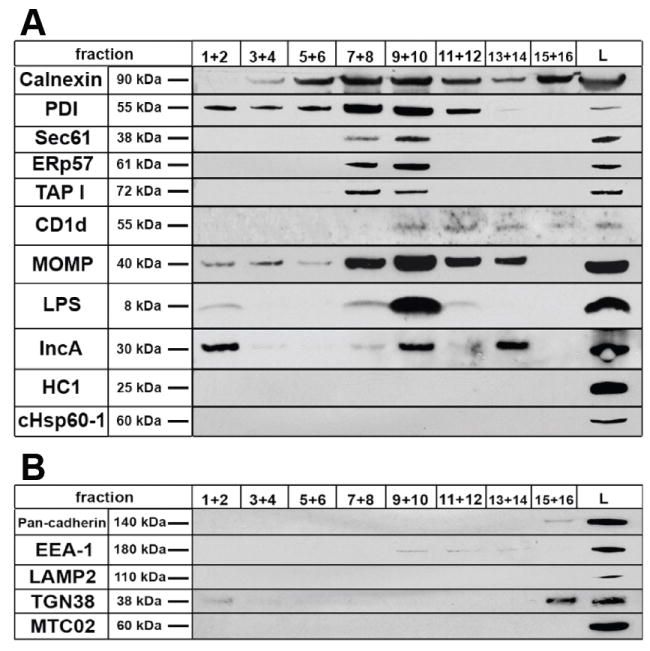

Organelles of the secretory pathway were isolated from uninfected control and C. trachomatis-infected HEC-1B cells using Iodixanol (Optiprep) gradients and the resultant fractions were subjected to Western blot analysis by probing with antibodies to the ER and chlamydiae (Fig. 4). Several ER membrane (TAP-I and Sec61) and luminal (calnexin, ERp57, PDI and CD1d) markers positively labeled fractions 7-10, defining the ER-containing fractions. These results match those of Plonne and colleagues [11] who found, through enzymatic assays, the ER to occupy the same area in the gradient. Chlamydial LPS, MOMP and IncA were found in the ER-containing fractions. The abundant detection of these antigens in the ER-containing fractions compared to the cell lysate is attributed to enrichment of the ER and therefore the associated chlamydial antigens. The positive control markers for intact EB and RB, chlamydial HC1 and cHsp60-1, were detected only in the infected cell lysate (Fig. 4, column L), indicating that the presence of LPS, MOMP and IncA in fractions 7-10 could not be attributed to contaminating whole chlamydial forms. Indeed, probing of the mitochondrial pellet yielded reactivity to all chlamydial antibodies (data not shown), suggesting that EB and RB were pelleted with the mitochondria, which is routine. Fractionation and Western blot of uninfected cells yielded a similar detection pattern of host proteins compared to infected cells (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Western blot analysis of gradient fractions with antibodies specific for ER components and chlamydial antigens from C. trachomatis-infected HEC-1B cells. Serial fractions were pooled and ten micrograms of protein was separated on 4-12% gradient gels using SDS-PAGE prior to immunoblotting. The positive control ER markers calnexin, PDI, Sec61, Erp57 and TAP-I displayed strong detection in fractions 7-10, defining the ER-containing fractions. CD1d, an MHC-like glycoprotein resident of the ER, was found primarily in fractions 9-12. Chlamydial MOMP, LPS and IncA were strongly detected in the ER-containing fractions. The positive control chlamydial markers HC1 and cHsp60-1, known to be restricted to intact chlamydial EB and RB, were only detected in the infected cell post-nuclear lysate (L). (B) Antibodies to host plasma membrane, endosomes, lysosomes, Golgi and mitochondria indicate no contamination of ER-containing fractions with other host cell organelles.

Chlamydial membranes from RB and/or the inclusion membrane would account for the presence of LPS, MOMP and IncA detected in membrane fractions 1 and 2 but absent in other fractions. As controls, antibodies to host cell plasma membrane (pan-cadherin), endosomes (EEA-1), lysosomes (LAMP2), Golgi (TGN38) and mitochondria (MTC02) confirmed the absence of these organelles in ER-containing fractions (Figure 4B).

Fractions 7-10 represent smooth ER, where antigens are transported into and loaded onto MHC-I molecules. Fractions 11 and 12 are likely rough ER/smooth ER transitional regions while fractions 13 and 14, which were positive for MOMP and IncA, appear to represent a subfraction of vesicles derived from rough ER, as shown by Plonne and colleagues [11]. These fraction isolation data strongly support the presence of important chlamydial antigens in the ER of infected endometrial cells.

3.4. Examination of the isolated ER/chlamydial antigen-containing fractions by TEM

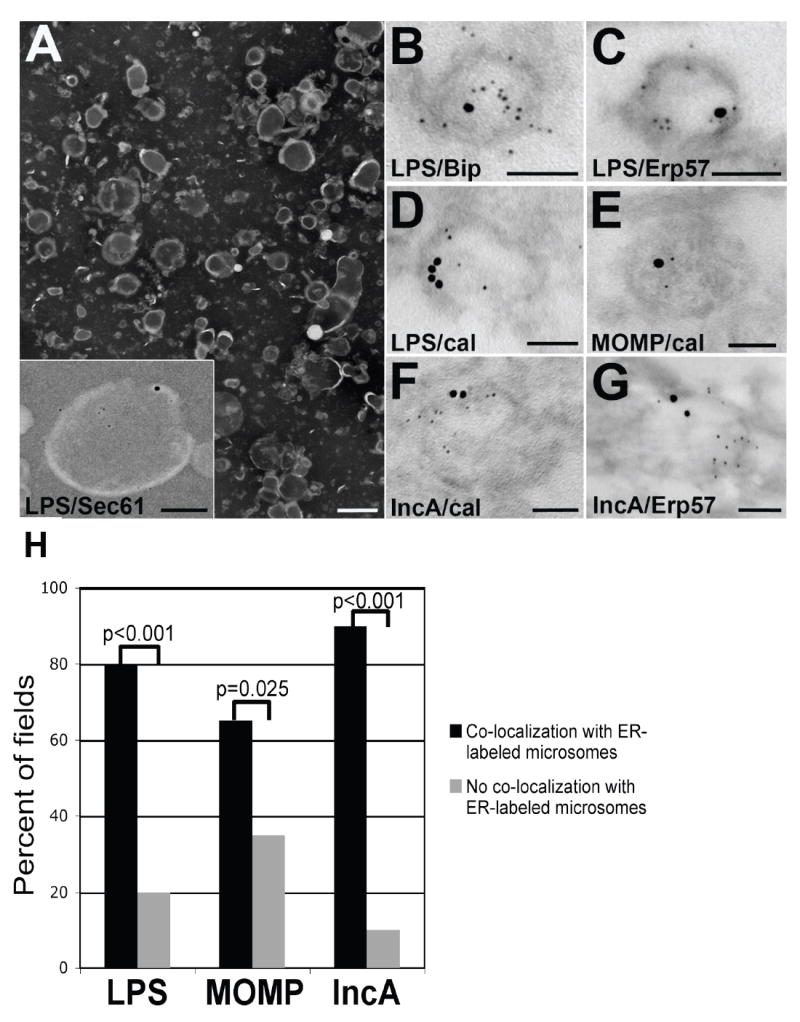

For additional confirmation that the isolated gradient fractions 7-10 were ER vesicles containing chlamydial antigen, pooled gradient fractions were viewed by negative stain and processed for post-embedding immunoelectron microscopy. The crude microsomal fraction contained numerous vesicles ranging from 100-500 nm in size (Fig. 5A), representing a typical vesicle preparation. Immunostaining of the crude microsomal fraction revealed vesicles co-labeling for chlamydial LPS and Sec61, an ER membrane marker (Fig. 5A, inset). Closer examination of the ER/chlamydial antigen-containing fractions 7-10 by double-label immunoelectron microscopy revealed a subset of vesicles which displayed co-localization between chlamydial LPS, MOMP and IncA and a variety of ER markers (Fig. 5B-G). LPS was detected within vesicles co-labeling for the ER luminal markers BiP/GRP78, Erp57 and calnexin (Fig. 5B-D). MOMP also localized to vesicles containing calnexin (Fig. 5E). IncA was associated with vesicles positive for calnexin and Erp57 (Fig. 5F and G). All vesicles exhibiting co-localization were approximately 100-200 nm in size, a morphological trait characteristic of isolated ER microsomes. As negative controls, antibodies to endosomes, lysosomes and Golgi did not label any vesicles within the ER/chlamydial-containing fractions (data not shown). Quantitation revealed statistical significance for the co-localization of chlamydial antigens with ER markers, particularly for LPS, MOMP and IncA (Fig. 5H).

Fig. 5.

Examination of ER/chlamydial antigen-containing isolated density gradient fractions by TEM. (A) Representative negative stain of the crude ER microsomal fraction from C. trachomatis-infected HEC-1B cells. Scale bar, 500 nm. The inset represents double-label immunogold electron microscopy co-localizing chlamydial LPS (5 nm gold) and the ER membrane marker Sec61 (15 nm gold) to an ER microsomal vesicle. Scale bar, 100 nm. (B-D) Double-label immunogold electron microscopy revealed co-localization between chlamydial LPS (5 nm gold) and three ER markers (15 nm gold): BiP/GRP78 (B), Erp57 (C) and calnexin (cal; D). Scale bars, 100 nm. (E) Co-localization between chlamydial MOMP (5 nm gold) and the ER marker calnexin (15 nm gold). Scale bar, 100 nm. (F and G) Co-localization between chlamydial IncA (5 nm gold) and the ER markers (15 nm gold) calnexin (cal; F) and Erp57 (G). Scale bar, 100 nm. Chlamydial antibodies were detected with 5 nm-gold-conjugated secondary antibodies. ER antibodies were detected with 15 nm-gold-conjugated secondary antibodies. (H) Multiple images (>50 fields per chlamydial antigen) containing isolated ER microsomes were assessed for co-localization and converted to percentages for graphical representation. Levels of significance are indicated by p-values comparing the co-localization versus non-co-localization between each chlamydial antigen and ER-labeled microsomes.

3.5. Ultrastructural association between chlamydial LPS and CD1d, a lipid antigen presenting MHC-like glycoprotein

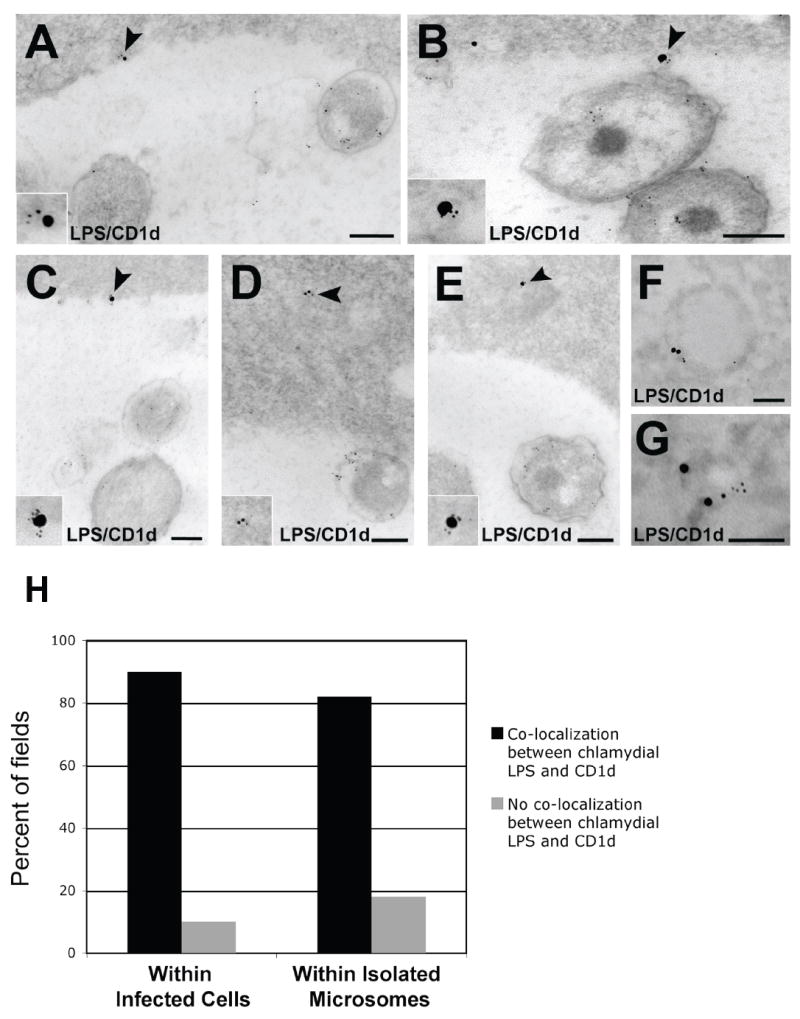

The localization of chlamydial LPS in the ER of infected cells was a surprising finding. Exogenous LPS activates the TLR 4 pathway, but the fate of intracellular LPS is unclear. CD1d molecules, which present lipids derived from intracellular sources, specifically signal natural killer T (NKT) cells. That CD1d is proposed to bind endogenous lipid within the ER and traffic to the plasma membrane for T cell recognition led to an investigation on potential interaction between chlamydial LPS and CD1d. HEC-1B cells were found to possess CD1d following Western blot of uninfected HEC-1B lysate (data not shown). Immunoelectron microscopy of C. trachomatis-infected HEC-1B cells revealed co-localization between chlamydial LPS and CD1d at the inclusion membrane (Fig. 6A-C) and in tracts and vesicular structures within the host cell cytosol (Fig. 6D and E). Following ER isolation, examination of ER-containing fractions by post-embedding immunoelectron microscopy indicated co-localization of chlamydial LPS and CD1d within the same vesicles (Fig. 6F and G). The association between chlamydial LPS and CD1d was supported by statistical analysis (p<0.001) of multiple images from both infected cells and isolated microsomes (Fig. 6H).

Fig. 6.

The MHC-like glycolipid-binding protein CD1d co-localizes with chlamydial LPS in the ER during C. trachomatis-infection of polarized human endometrial epithelial cells. (A-C) Co-localization between CD1d (15 nm gold) and chlamydial LPS (5 nm gold) at the inclusion membrane (arrowheads; magnified in insets). Scale bars, 200 nm. (D and E) Co-localization between CD1d (15 nm gold) and chlamydial LPS (5 nm gold) within vesicles present in the infected host cell cytosol (arrowheads; magnified in insets). Scale bars, 200 nm. (F and G) Co-localization between CD1d (15nm gold) and chlamydial LPS (5 nm gold) within vesicles isolated from ER-containing fractions (see Fig. 5). Scale bars, 100 nm. CD1d antibodies were detected with 15 nm-gold-conjugated second-affinity antibodies. LPS antibodies were detected with 5 nm-gold-conjugated secondary antibodies. (H) The extent of chlamydial LPS/CD1d co-localization was assessed quantitatively by examining multiple images (>50 fields from infected cells and >50 fields from isolated microsomes) to obtain percentages for graphical representation. Levels of significance (all p-values<0.001) indicate co-localization of chlamydial LPS with CD1d within both infected cells and isolated microsomes.

4. Discussion

There have been some intriguing observations hinting towards interaction between Chlamydia and the ER, an association now recognized as important for other intracellular microorganisms [12]. The inclusion membrane has been shown to acquire ER composition in the form of host cell phospholipids [13]. Majeed and colleagues [14] observed the ER proteins SERCA2 and calreticulin closely associated with chlamydial inclusions using confocal microscopy. Since these events can occur early-mid developmental cycle, it is clear that the juxtaposition of the ER with the inclusion membrane is due to active recruitment by Chlamydia rather than the result of chlamydial inclusion expansion within the host cell resulting in organelle crowding around the inclusion. Most intriguing are the recent reports of chlamydial inclusion membrane proteins (IncA, Cpn0146 and Cpn0147) co-localizing with the ER when expressed via transgenes in HeLa cells [9,15] as well as the colocalization of two C. pneumoniae proteins (Cpn0809 and Cpn1020) and several C. trachomatis D Inc proteins (CT 115-119, 223, 225, 226, 232 and 442) with the ER marker calnexin by indirect immunofluorescence [16,17]. Our data strengthen and extend the observations of involvement of the ER during chlamydial infection.

There are three known ways by which chlamydial proteins traverse the inclusion and reach the ER of infected epithelial cells. Zhong and colleagues [18] were the first to show that a chlamydial protease-like activity factor (CPAF) appeared in the cytosol of infected cells. Subsequently, an apoptosis-modulating chlamydial protein, CADD [Chlamydial protein Associating with Death Domains], was also found in the infected cell cytosol [19]. The identification of host cell cytosolic IncA-laden fibers containing chlamydial antigens represents another incidence of directed chlamydial antigen escape from the inclusion [20]. How these proteins are transported across the inclusion membrane is unknown. Secondly, intracellular chlamydiae can inject effector proteins into the host cytosol via T3S machinery[21]. In these cases, any chlamydial protein reaching the host cytosol would be presumed subject to classical MHC-I processing and presentation. Thirdly is the aforementioned eversion of inclusion membrane-derived vesicles containing chlamydial OMVs positive for LPS, MOMP and IncA [8]. If these vesicles do fuse with the ER via IncA, such a delivery of presumably native chlamydial protein into the ER would require intra-ER peptide trimming [22] and/or Sec61/chaperone retrotranslocation into the cytosol for proteasomal degradation [23] for antigen presentation to occur.

Epithelial cells typically express high levels of MHC-I compared to MHC-II, underscoring the important role for CD8+ T cells in the recognition of C. trachomatis-infected genital mucosa [24]. The presence of chlamydial protein either in the host cell cytosol or integrated into the inclusion membrane does not go unnoticed, as indicated by the identification of specific antigen epitopes that are T cell targets of cell-mediated immune response [25]. MOMP cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitope clusters have been identified and MOMP-specific CD8+ T cells can be detected during Chlamydia infection [26]. Despite its low endotoxic potency, chlamydial LPS can signal via TLR2 and TLR4, molecules recently shown to be recruited to the inclusion during Chlamydia infection [27].

While numerous studies have examined the immunological effects of exogenous LPS, only a few studies have addressed the handling of LPS released intracellularly. CD1d possesses deep independent hydrophobic pockets for anchoring long fatty acyl chains, such as the C22-C24 (versus C12-C14) of chlamydial lipid A. Bilenki and colleagues [28] reported evidence for the involvement of NKT cells during chlamydial infection in mice and suggested that CD1d-restricted NKT cells can affect the immune response to Chlamydia infection and play a role in pathological outcome. More recently, chlamydial CPAF activity was shown to down regulate CD1d surface expression and CD1d-mediated cytokine production on human penile urethelial cells [29,30]; both consequences may reduce interaction with invariant NKT cells and aid chlamydiae in escaping detection by innate immune cells. While CD1d was detected in and on the surface of our HEC-1B cells, we observed by Western blot a similar pattern of CD1d degradation during C. trachomatis infection as reported previously [30]. Further, our findings of co-localization of CD1d and chlamydial LPS in the infected cell ER is consistent with the ER-associated degradation pathway of CD1d heavy chains in C. trachomatis-infected epithelia [30].

In summary, our data support a greater role for the ER during chlamydial infection in polarized human endometrial epithelial cells. Considering the escapability and immunogenic properties possessed by chlamydial LPS, MOMP and IncA, the trafficking of chlamydial lipids and proteins to the ER is likely to affect ER functions, through ER stress, and/or provide antigens for MHC-I and CD1d presentation. Whether or not the results serve a protective role or an immuno-destructive role for chlamydiae is yet to be determined. Ongoing studies are exploring whether or not bulk flow of secreted chlamydial antigens to the ER serves as a pathway for presentation of chlamydial proteins and lipids on host MHC molecules.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a Public Health Service grant from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases R01-AI13446.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hybiske K, Stephens RS. Mechanisms of host cell exit by the intracellular bacterium Chlamydia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:11430–11435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703218104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Todd WJ, Caldwell HD. The interaction of Chlamydia trachomatis with host cells: ultrastructural studies of the mechanism of release of a biovar II strain from HeLa 229 cells. J Infect Dis. 1985;151:1037–1044. doi: 10.1093/infdis/151.6.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beatty WL. Trafficking from CD63-positive late endocytic multivesicular bodies is essential for intracellular development of Chlamydia trachomatis. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:350–359. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cocchiaro JL, Kumar Y, Fischer ER, Hackstadt T, Valdivia RH. Cytoplasmic lipid droplets are translocated into the lumen of the Chlamydia trachomatis parasitophorous vacuole. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712241105. manuscript in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Younes HM, Brinkmann V, Meyer TF. Interaction of Chlamydia trachomatis serovar L2 with the host autophagic pathway. Infect Immun. 2004;72:4751–4762. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.8.4751-4762.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wira CR, Grant-Tschudy KS, Crane-Goudreau MA. Epithelial cells in the female reproductive tract: a central role as sentinels of immune protection. Am J Reprod Immun. 2005;53:65–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2004.00248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roan NR, Starnbach MN. Immune-mediated control of Chlamydia infection. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:9–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giles DK, Whittimore JD, LaRue RW, Raulston JE, Wyrick PB. Ultrastructural analysis of chlamydial antigen-containing vesicles everting from the Chlamydia trachomatis inclusion. Microbes Infect. 2006;8:1579–1591. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delevoye C, Nilges M, Dautry-Varsat A, Subtil A. Conservation of the biochemical properties of IncA from Chlamydia trachomatis and Chlamydia caviae: oligomerization of IncA mediates interaction between facing membranes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:46896–46906. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407227200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guseva NV, Dessus-Babus S, Moore CG, Whittimore JD, Wyrick PB. Differences in Chlamydia trachomatis serovar E growth rate in polarized endometrial and endocervical epithelial cells grown in three-dimensional culture. Infect Immun. 2007;75:553–564. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01517-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Plonne D, Cartwright I, Lin W, Dargel R, Graham JM, Higgins JA. Separation of the intracellular secretory compartment of rat liver and isolated rat hepatocyted in a single step using self-generating gradients of iodixanol. Anal Biochem. 1999;276:88–96. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roy CR, Salcedo SP, Gorvel JP. Pathogen--endoplasmic-reticulum interactions: in through the out door. Nature Rev Immunol. 2006;6:136–147. doi: 10.1038/nri1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wylie JL, Hatch GM, McClarty G. Host cell phospholipids are trafficked to and then modified by Chlamydia trachomatis. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7233–7242. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.23.7233-7242.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Majeed M, Krause K-H, Clark RA, Kihlstrom E, Stendahl O. Localization of intracellular Ca2+ stores in HeLa cells during infection with Chlamydia trachomatis. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:35–44. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luo J, Liu G, Zhong Y, Jia T, Liu K, Chen D, Zhong G. Characterization of hypothetical proteins Cpn0146, 0147, 0284 and 0285 that are predicted to be in the Chlamydia pneumoniae inclusion membrane. BMC Microbiol. 2007;7:38. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-7-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Z, Chen C, Chen D, Wu Y, Zhong Y, Zhong G. Characterization of fifty putative inclusion membrane proteins encoded in the Chlamydia trachomatis genome. Infect Immun. 2008;76:2746–2757. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00010-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muller N, Sattelmacher F, Lugert R, Gross U. Characterization and intracellular localization of putative Chlamydia pneumoniae effector proteins. Med Microbiol Immunol. doi: 10.1007/s00430-008-0097-y. manuscript in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhong G, Liu L, Fan T, Fan P, Ji H. Degradation of transcription factor RFX5 during the inhibition of both constitutive and interferon gamma-inducible major histocompatibility complex class I expression in Chlamydia-infected cells. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1525–1534. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.9.1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stenner-Liewen F, Liewen H, Zapata JM, Pawlowski K, Godzik A, Reed JC. CADD, a Chlamydia protein that interacts with death receptors. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:9633–9636. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100693200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown WL, Skeiky YA, Probst P, Rockey DD. Chlamydial antigens colocalize within IncA-laden fibers extending from the inclusion membrane into the host cytosol. Infect Immun. 2002;70:5860–5864. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.10.5860-5864.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fields KA, Fischer ER, Mead DJ, Hackstadt T. Analysis of putative Chlamydia trachomatis chaperones Scc2 and Scc3 and their use in the identification of type III secretion substrates. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:6466–6478. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.18.6466-6478.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paz P, Brouwenstijn N, Perry R, Shastri N. Discrete proteolytic intermediates in the MHC class I antigen processing pathway and MHC I-dependent peptide trimming in the ER. Immunity. 1999;11:241–251. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80099-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiertz EJ, Tortorella D, Bogyo M, Yu J, Mothes W, Jones TR, Rapoport TA, Ploegh HL. Sec61-mediated transfer of a membrane protein from the endoplasmic reticulum to the proteasome for destruction. Nature. 1996;384:432–438. doi: 10.1038/384432a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roan NR, Starnbach MN. Antigen-specific CD8+ T cells respond to Chlamydia trachomatis in the genital mucosa. J Immunol. 2006;177:7974–7979. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.7974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Starnbach MN, Loomis WP, Ovendale P, Regan D, Hess B, Alderson MR, Fling SP. An inclusion membrane protein from Chlamydia trachomatis enters the MHC class I pathway and stimulates a CD8+ T cell response. J Immunol. 2003;171:4742–4749. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.9.4742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim SK, DeMars R. Epitope clusters in the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia trachomatis. Curr Opin Immunol. 2001;13:429–436. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(00)00237-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mackern-Oberti JP, Maccioni M, Cuffini C, Gatti G, Rivero VE. Susceptibility of prostate epithelial cells to Chlamydia muridarum infection and their role in innate immunity by recruitment of intracellular Toll-like receptors 4 and 2 and MyD88 to the inclusion. Infect Immun. 2006;74:6973–6981. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00593-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bilenki L, Wang S, Yang J, Fan Y, Joyee AG, Yang X. NK T cell activation promotes Chlamydia trachomatis infection in vivo. J Immunol. 2005;175:3197–3206. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.3197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kawana K, Matsumoto J, Miura S, Shen L, Kawaana Y, Nagamatsu T, Yasugi T, Fujii T, Yang H, Quayle AJ, Takatain Y, Schust DJ. Expression of CD1d and ligand-induced cytokine production are tissue-specific in mucosal epithelia of the human lower reproductive tract. Infect Immun. 2008;76:3011–3018. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01672-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawana K, Quayle AJ, Ficarra M, Ibana JA, Shen L, Kawana Y, Yang H, Marrero L, Yavagal S, Greene SJ, Zhang Y-X, Pyles RB, Blumberg RS, Schust DJ. CD1d degradation in Chlamydia trachomatis-infected epithelial cells is the result of both cellular and chlamydial proteasomal activity. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:7368–7375. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610754200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]