Abstract

Aims

We previously showed that enhanced myogenic constriction (MC) of peripheral resistance arteries involves active AT1 receptors in chronic heart failure (CHF). Recent data suggest both transactivation of EGF receptors and caveolae-like microdomains to be implicated in the activity of AT1 receptors. Thus, we assessed their roles in increased MC in mesenteric arteries of CHF rats.

Methods and results

Male Wistar rats underwent myocardial infarction to induce CHF and were sacrificed after 12 weeks. The number of caveolae in smooth muscle cells (SMC) of mesenteric arteries of CHF rats was decreased by 43.6 ± 4.0%, this was accompanied by increased MC, which was fully normalized to the level of sham by antagonists of the AT1-receptor (losartan) or EGF-receptor (AG1478). Acute disruption of caveolae in sham rats affected caveolae numbers and MC to a similar extent as CHF, however MC was only reversed by the antagonist of the EGF-receptor, but not by the AT1-receptor antagonist. Further, in sham rats, MC was increased by a sub-threshold concentration of angiotensin II and reversed by both AT1- as well as EGF-receptor inhibition. In contrast, increased MC by a sub-threshold concentration of EGF was only reversed by EGF receptor inhibition.

Conclusion

These findings provide the first evidence that decreased SMC caveolae numbers are involved in enhanced MC in small mesenteric arteries, by affecting AT1- and EGF-receptor function. This suggests a novel mechanism involved in increased peripheral resistance in CHF.

Keywords: Chronic heart failure, Myogenic constriction, Caveolae, AT1 receptor, EGF receptor

Introduction

Increased peripheral resistance is a hallmark of chronic heart failure (CHF).1 Initially, increased vasoconstriction may serve as a compensatory mechanism to help maintain perfusion of vital organs by sustaining blood pressure. In the long-term, however, chronic vasoconstriction may become excessive and induce deleterious effects by augmenting work-load on the already impaired cardiac pump,1 thus contributing towards further progression of CHF. Increased vascular resistance in CHF is generally thought to be caused by stimulation of neurohumoral systems such as the renin–angiotensin system (RAS).1 The effector molecule of the RAS, angiotensin II, is a well-known vasoactive substance that acts on the AT1 receptor on vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) to cause vasoconstriction. Apart from systemic factors, local mechanisms also contribute importantly to set arterial tone. Small arteries respond to an increase in intraluminal pressure with an active constriction of VSMCs, termed myogenic constriction.2 We previously found that this response was increased in small mesenteric resistance arteries of rats with experimental CHF, but was normalized by acute AT1 receptor blockade.3 Since this was observed in the absence of exogenous angiotensin II, it was suggested that the constitutive activity of AT1 receptors in CHF mediates the increased myogenic constriction.3

Interestingly, some of the effects of angiotensin II appear to be mediated by transactivation of the epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor, including in pathophysiological conditions such as angiotensin II-induced left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy.4 Additional evidence links the AT1 receptor to transactivation of the EGF receptor in VSMCs, but also implies that caveolae-like microdomains are essential in this process.5,6

Caveolae are specific cholesterol-rich microdomains in the plasma membrane, and are considered a subcategory of lipid rafts. They harbour several receptors, G proteins, and Ca2+ channels, among others, and ensure the compartmentalization of these signalling molecules.7 The importance of caveolae in the cardiovascular system may be illustrated by the findings of Darblade et al.,8 who reported a decreased number of endothelial caveolae to be associated with impaired acetylcholine-induced relaxation in aortic preparations containing fatty streak deposits in a rabbit model of atherosclerosis. Although studies actually investigating alterations in caveolar abundance in cardiovascular disease are limited so far, emerging evidence of altered caveolin expression levels and membrane dissociation patterns in cardiomyocytes from rats with experimental CHF9 may be relevant. Finally, specific signalling processes and molecules involved in arterial myogenic constriction have been shown to be associated with caveolae or caveolar transductsome function.2,7 It may thus be hypothesized, that alterations in caveolae may underlie increased myogenic constriction in CHF, possibly by changing receptor signalling processes. To explore this, we studied the functional relationships between caveolae numbers and myogenic constriction in small mesenteric resistance arteries of normal rats and myocardial infarction (MI) rats with CHF, focusing on the role of AT1- and EGF-receptor activity.

Methods

Animals

Male Wistar rats (275–300 g, Harlan, Zeist, the Netherlands) were housed in groups of four to five rats at the animal facility of the University of Groningen with free access to food and drinking water. After a 10-day acclimatization period, rats underwent surgery for induction of experimental MI. All sham rats (n = 20) survived the surgical procedure, whereas total mortality among the MI rats was 27% (14 out of 52). All animal experimentation was reviewed and approved by the Animal Research Committee at the University of Groningen, and conducted in accordance with National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Cardiac function and infarct-size

Twelve weeks after surgery, rats were anaesthetized and the right carotid artery was cannulated with a pressure transducer catheter. Then, the haemodynamic parameters were measured.3 After haemodynamic measurements, hearts were rapidly excised and weighed. A transverse slice through the midst of the LV containing the infarcted area was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin and 10 µm slices were cut and stained for histological analysis. Infarct size was then determined by the methods described in detail elsewhere. Only MI rats with infarct-size >20% (26 out of 38) were included for analysis.

Functional analysis of mesenteric arteries

The second and third order branches of the superior mesenteric artery were isolated and prepared for EM-analysis of caveolae numbers (see in what follows) or transferred to an arteriograph system for pressurized arteries as described previously.3 Active and passive pressure-diameter curves were obtained over a pressure range of 20–160 mmHg in steps of 20 mmHg.3 Additional artery segments were used to determine pressure diameter curves in the presence of different inhibitors or appropriate vehicles administered to the Krebs solution 20 min before determination of pressure–diameter curves. The cholesterol-binding agents filipin (4 µg mL−1) and methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MCD, 1 mmol L−1) were used to study the effect of disruption of caveolae. Losartan (10 µmol L−1) and AG1478 (5 µmol L−1) were used to study the effects of AT1-receptor and EGF-receptor inhibition, respectively. In some experiments, myogenic constriction was studied in the presence of angiotensin II (10 nmol L−1) or EGF (50 ng mL−1). In some cases, the endothelium of the segments was removed by rubbing the intimal surface of the vessel segments with a hair of appropriate size. Removal of endothelium was confirmed by the absence of relaxation to 10−4 mol L−1 acetylcholine in phenylephrine (10−6 mol L−1) pre-contracted vessel segments.

Electron microscopy analysis of caveolae numbers

Small mesenteric artery segments of sham and MI rats were incubated with either filipin (4 µg mL−1) or vehicle for 20 min at 37°C in oxygenated Krebs solution, before they were fixed in 1% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 mol L−1 sodium cacodylate buffer for 24 h. Following post-fixation in 1% osmium tetroxide plus 1.5% potassium ferrocyanide in 0.1 mol L−1 sodium cacodylate buffer, artery segments were dehydrated in a graded alcohol series and embedded in Epon-812 resin. Ultrathin sections were taken perpendicular to the substrate and stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Images taken on a Philips CM100 (FEI, Eindhoven, the Netherlands) electron microscope operated at 60 kV were digitized. The images were analysed with analySIS (Munster, Germany) image software to measure the number of caveolae per micron of membrane in 30 fields from three independent sections from sham and filipin treatment segments (n = 5 rats in sham group; n = 7 in CHF group, respectively). Caveolae were defined as uncoated surface invaginations of 50–100 nm size with clear connections to the VSMC plasma membrane.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence

Caveolin-1 and caveolin-3 were detected using a two-step immunoperoxidase technique. Six cryostat sections (5 µm thickness) were cut at three different levels in the mesenteric artery, every two sections at a 50 µm interval. The sections were dried, fixed in acetone for 10 min and then treated with 0.3% H2O2 in TBS, for 30 min, to block the endogenous peroxidase (PO). Caveolin-1 and caveolin-3 were detected with a mouse anti-caveolin-1 and a mouse anti-caveolin-3 antibody, respectively (BD, Biosciences, Erembodegem, Belgium) in TBS containing 1% BSA (bovine serum albumin), followed by incubation with secondary-PO labelled antibodies. Peroxidase activity was developed in the presence of 3′, 3′-diaminobenzidine tetrachloride (DAB) and H2O2. Control sections incubated with TBS/BSA or the same isotype Ig instead of anti-caveolin antibodies were negative.

The caveolin staining was selectively measured in the vascular smooth muscle layer by computer-assisted morphometry. The total area of staining was divided by the area measured and expressed as a percentage. The average of six sections per rat was determined.

In addition, co-localization of EGF- and AT1-receptors was studied using double immunofluorescence. Frozen sections were incubated with primary antibodies (mouse anti-EGF receptor, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Heidelberg, Germany, and rabbit anti-AT1 receptor, kind gift from Dr W.W. Bakker, UMC Groningen, the Netherlands), followed by incubation with FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse and TRITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, AL, USA). Green (FITC) and red (TRITC) fluorescent signals were visualized using confocal microscopy.

Drugs

Vascular studies were performed using a Krebs bicarbonate solution with the following composition (mmol L−1): NaCl 120.4, KCl 5.9, CaCl2 2.5, MgCl2 1.2, NaH2PO4 1.2, glucose 11.5, and NaHCO3 25.0, freshly prepared daily. AG 1478 was dissolved in DMSO, filipin was prepared in 96% ethanol. All other drugs were dissolved in de-ionized water and diluted with Krebs solution. All compounds were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA).

Calculations and statistical analysis

Myogenic constriction is expressed as percent decrease in diameter from the maximally dilated (passive) diameter determined at the same pressure in calcium-free solution supplemented with EGTA (2 mmol L−1), i.e. myogenic constriction (%)=100 [(DCa-free − DCa) DCa-free−1], which D is the diameter in calcium-free (DCa-free) or calcium-containing (DCa) Krebs. On some occasions—for reasons of clarity and convenience in presenting the results—the Area Under each individual pressure–myogenic constriction Curve (AUC) was determined (SigmaPlot, Systat, Richmond, USA) and expressed in arbitrary units, and used to represent the overall myogenic response-size for a given condition. Data are expressed as mean±SEM. Comparisons were performed using Student’s t-test, or repeated measures ANOVA in case of full pressure–diameter curves. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Rat characteristics and cardiac function

At baseline, no differences in body weight were observed (data not shown). After 12 weeks, body weight was slightly lower in rats with MI compared with sham rats, but the difference did not reach statistical significance. The relative heart weight as well as LVEDP were increased in MI-rats, while systolic and diastolic dP/dt were decreased (Table 1).

Table 1.

Infarct size and cardiac function in rats at 12 weeks after myocardial infarction or sham surgery

| Sham rats (n = 20) | Heart failure rats (n = 26) | |

|---|---|---|

| Infarct size (%) | — | 39 ± 2a |

| Body weight (g) | 493 ± 7 | 481 ± 6 |

| Heart-to-body weight ratio (g/kg) | 2.9 ± 0.1 | 3.4 ± 0.1a |

| Heart rate (b.p.m.) | 359 ± 6 | 348 ± 5 |

| Systolic pressure (mmHg) | 126 ± 4 | 109 ± 2a |

| Diastolic pressure (mmHg) | 90 ± 3 | 79 ± 2a |

| Systolic dP/dt (mmHg/s) | 13 446 ± 220 | 10 073 ± 344a |

| Diastolic dP/dt (mmHg/s) | −11 653 ± 295 | −8282 ± 347a |

| LVESP (mmHg) | 132 ± 3 | 113 ± 2a |

| LVEDP (mmHg) | 10.1 ± 0.7 | 16.3 ± 1.4a |

LVESP, left ventricular end systolic pressure; LVEDP, left ventricular end diastolic pressure.

Data are expressed as mean±SEM.

aP < 0.01 for heart failure vs. sham.

Caveolae numbers and myogenic constriction

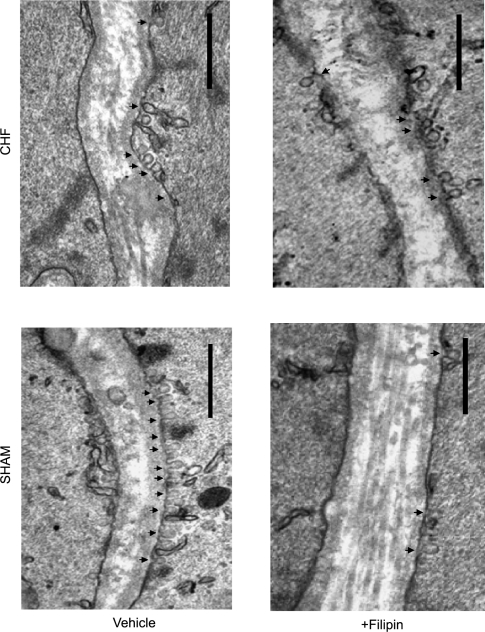

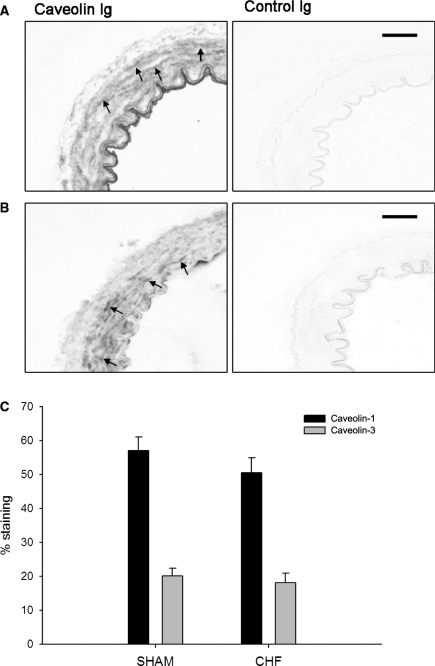

The number of caveolae in VSMCs of mesenteric arteries was measured by transmission electron microscopy. The caveolae profiles were readily visible as non-coated plasmalemmal vesicles with a round lumen of up to 50–100 nm (Figure 1). Compared with sham, the number of caveolae was markedly reduced by 43.6 ± 4.0% (P < 0.01) in VSMCs of mesenteric arteries of CHF rats. However, similar caveolin-1 and caveolin-3 expression in the VSMC layer was found in sham and CHF rats (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Visualization of caveolae in mesenteric artery vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) of sham rats and myocardial infarction rats with chronic heart failure (CHF) using transmission electron microscopy. Representative sections treated either with vehicle or with filipin are shown. Arrowheads indicate caveolae; bar, 0.5 µm in each case.

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemistry for caveolin-1 and caveolin-3. Representative pictures of sections from whole rings of mesenteric artery stained for caveolin-1 (A) and caveolin-3 (B) (bars represent 25 µm, arrows indicate positive smooth muscle cells). Left panel shows negative staining in control Ig treated sections. (C) Quantification of the caveolin-1 and caveolin-3 staining selectively in the vascular smooth muscle layer. Data are expressed as mean±SEM (n = 6 in sham and n = 4 in CHF).

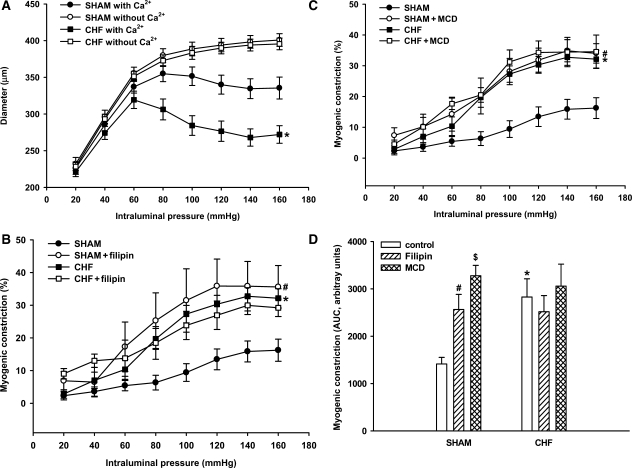

Adjacent mesenteric artery segments were additionally studied for pressure–diameter relationships in a set-up for pressurized vessels. Passive diameters did not differ between sham and CHF arteries over the whole pressure-range studied (20–160 mmHg; Figure 3A). Active diameters were significantly smaller in both groups, indicating the development of myogenic constriction. Importantly, myogenic constriction was significantly higher in arteries of CHF rats when compared with sham over the whole pressure range (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Myogenic constriction determined from pressure–diameter relationships in small mesenteric arteries of sham rats and myocardial infarction rats with chronic heart failure (n = 15 for both groups). (A) Arteries were subjected to stepwise increase in intraluminal pressure in the absence and presence of extracellular calcium (Ca2+) and the diameter was determined at each step. Active diameters in the presence of Ca2+—but not passive diameters in the absence of Ca2+—were significantly smaller in the arteries of rats with CHF (*P < 0.05 vs. sham with Ca2+ in A). (B and C) Consequently, myogenic constriction (% of passive diameter) was significantly increased in arteries of rats with CHF (*P < 0.05 vs. sham in B and C). Treatment with filipin (4 µg mL−1, n = 6) or methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MCD, 1 mmol L−1, n = 6) significantly increased myogenic constriction in arteries of sham rats (#P < 0.05 vs. sham in B and C, respectively), i.e. to levels similar as those observed in arteries of rats with CHF. (D) Similar results were obtained with endothelium-denuded arteries, indicating that the augmenting effect of filipin and MCD on myogenic constriction (represented by the AUC bar-size) of sham arteries was endothelium-independent (*,#,$P < 0.05 for CHF, sham filipin, and sham MCD, respectively, vs. sham control). Data are mean±SEM (n = 6–12 in each condition).

To further explore the relation between decreased caveolae numbers and increased myogenic constriction in CHF, the effects of an acute decrease in caveolae numbers were studied. To this end, mesenteric segments were incubated with filipin or MCD, two chemically unrelated cholesterol-binding agents that distort the structural integrity of caveolae. Treatment with filipin reduced caveolae numbers in sham arteries by ∼50%, as revealed by EM-analysis. Furthermore, in pressurized sham arteries, treatment with filipin resulted in a dramatic increase in myogenic constriction (Figure 3B). In contrast, in the arteries of CHF rats, filipin did not (further) attenuate the number of VSMC caveolae (Figure 1), nor did it (further) augment myogenic constriction (Figure 3B). Similar results were obtained with MCD (Figure 3C), suggesting that the observed effects were not molecule-related. To rule out the influence of endothelium, denuded mesenteric artery segments underwent a similar treatment with filipin and MCD. Significantly increased myogenic constriction was found in sham preparations treated with either filipin or MCD (Figure 3D); no further increase in myogenic constriction was shown in denuded arteries of CHF rats treated with filipin or MCD (Figure 3D). Thus, the reduction in the number of VSMC caveolae, either brought about by heart failure or by pharmacological disruption in sham rats, was accompanied by a marked increase in myogenic constriction. Importantly, in CHF, MCD or filipin treatment did not further reduce caveolae numbers or affect myogenic constriction.

AT1- and epidermal growth factor-receptor blockade and myogenic constriction

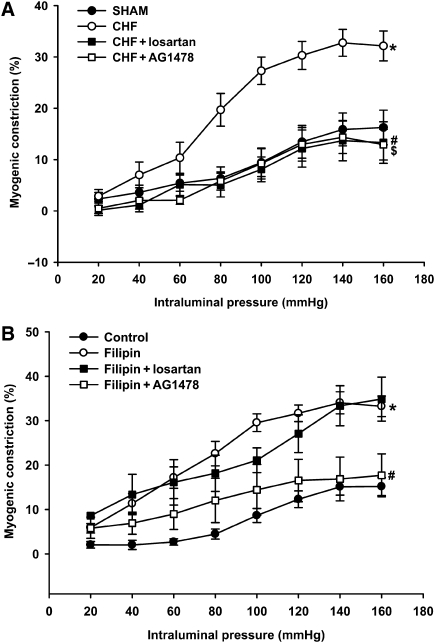

We previously showed increased myogenic constriction in CHF to be normalized by acute treatment with AT1 receptor blockers.3 In the current study, we sought to reconfirm AT1 receptor involvement and also to investigate the possible involvement of the EGF receptor in increased myogenic constriction in arteries with reduced caveolae numbers from CHF and following filipin-treatment. In accordance with our previous findings, AT1-receptor blockade with losartan normalized the increased myogenic constriction in CHF (Figure 4A). In addition, the increased myogenic response in arteries of CHF animals was also normalized by EGF-receptor inhibition using AG1478 (Figure 4A). Similar effects of losartan and AG1478 were observed on the increased myogenic constriction in endothelium denuded vessels (data not shown). In filipin-treated arteries from sham rats, however, the increased myogenic constriction was normalized solely by AG1478, but not by losartan (Figure 4B); similar results were obtained in MCD-treated arteries from sham rats (data not shown). For that matter, losartan and AG1478 had no effect on normal myogenic constriction in untreated mesenteric sham arteries (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Effect of EGF- and AT1-receptor blockade on increased myogenic constriction in mesenteric artery resulting from CHF or caveolae disruption. (A) Increased myogenic constriction in CHF (*P < 0.05 vs. sham) was fully normalized in the presence of the AT1-receptor antagonist losartan (10 µmol L−1,#P < 0.05 vs. CHF) or the EGF-receptor inhibitor AG1478 (5 µmol L−1, $P < 0.05 vs. CHF). (B) Treatment with filipin significantly increased myogenic constriction in arteries of sham rats (*P < 0.05); the EGF-receptor inhibitor, AG1478, significantly reduced myogenic constriction in filipin-treated sham arteries of sham rats (#P < 0.05 vs. filipin). In contrast, losartan did not affect enhanced myogenic constriction after filipin. Data are mean±SEM (n = 6–14 in each condition).

The potential additive effect of CHF and filipin or MCD was also studied. Addition of filipin or MCD did not further increase the myogenic constriction of CHF-artery preparations (Figure 3B and C). Moreover, the increased myogenic constriction observed under these conditions was fully normalized by treatment with either AG1478 or losartan (data not shown). Finally, the combination of losartan and AG1478 did not result in a further reduction of myogenic constriction in CHF arteries, beyond the level reached with either agent (data not shown).

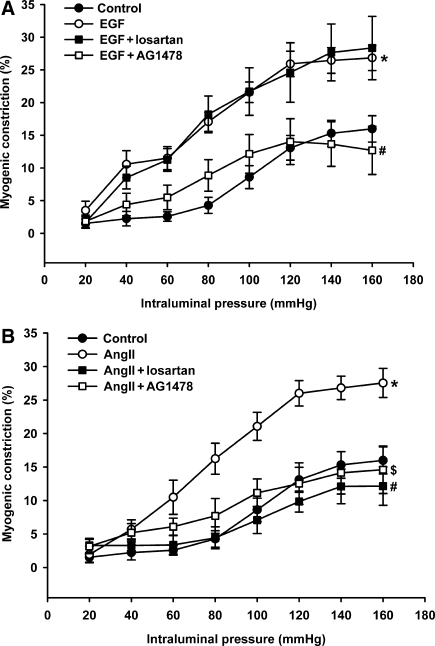

Myogenic constriction in the presence of sub-threshold concentrations of epidermal growth factor and angiotensin II

To further investigate the role of the EGF receptor and the AT1 receptor in increased myogenic constriction, pressure contraction relationships were investigated in the presence of sub-threshold concentrations of EGF and Ang II, respectively. EGF at a concentration of 50 ng mL−1 did not cause a contractile effect (data not shown), but significantly enhanced normal myogenic constriction (Figure 5A). This augmentation of myogenic constriction by EGF was prevented by AG1478, but not by losartan (Figure 5A). Incubation with a sub-threshold concentration of Ang II (10 nmol L−1) also resulted in a similar enhancement of myogenic constriction (Figure 5B). In contrast to EGF stimulation, however, the augmenting effect of angiotensin II on myogenic constriction was prevented by both losartan as well as AG1478 (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Augmentation of the myogenic response in normal mesenteric artery preparations of sham rats by sub-threshold concentrations of EGF (50 ng mL−1; *P < 0.05 vs. sham control; A) and angiotensin II (AngII, 10 nmol L−1; *P < 0.05 vs. sham control; B). (A) Enhanced myogenic constriction in the presence of EGF was selectively normalized by additional presence of AG1478 (5 µmol L−1, #P < 0.05 vs. EGF), but not by losartan (10 µmol L−1). (B) Enhanced myogenic constriction in the presence of angiotensin II was normalized both by losartan as well as AG1478 (#,$P < 0.05 for AngII + losartan and AngII + AG1478, respectively, vs. AngII only). Data are mean ± SEM (n = 6–13 in each condition).

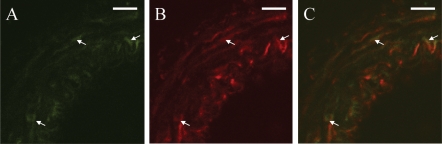

Co-localization of AT1 and epidermal growth factor receptors in vascular smooth muscle cells of mesenteric artery

Co-localization of AT1 and EGF receptors in the mesenteric arteries was investigated using double immunofluorescence for the two receptors. EGF-receptor expression was only found in VSMCs (Figure 6A), whereas AT1 receptor was expressed in VSMCs, in endothelial cells and in some cells in the adventitia (Figure 6B). EGF-receptor staining overlapped the AT1 receptor staining in VSMCs (Figure 6C), thus confirming co-localization of the two receptors.

Figure 6.

Co-localization of the EGF- and AT1-receptors. Immunofluorescent staining was performed for EGF receptor (A, green, arrows) and AT1 receptor (B, red, arrows) on mesenteric arteries and analysed with confocal microscopy. Co-localization is shown in yellow (C, arrows). Bar indicates 20 µm.

Discussion

In the present study, we provide evidence that increased myogenic constriction in CHF may be associated with a loss of plasmalemmal caveolae in mesenteric VSMCs, and postulate enhanced activity of the EGF- and AT1- receptors as a result thereof to be one of the contributing mechanisms.

To our knowledge, this is the first report on alterations in caveolae numbers in the VSMCs of resistance arteries of rats with CHF. The exact underlying cause was not a focus of this study, but the results may be in line with those of Ratajczak et al.9 Although they did not morphologically check the number of intact caveolae in the MI model, their findings of a dissociation of caveolin (i.e. the structural protein of caveolae) from the cell membrane to the cytosol of cardiomyocytes may be in keeping with our present finding that the number of plasmalemmal caveolae of VSMCs was markedly reduced (∼43%) in CHF, without a reduction in expression of caveolin-1 and caveolin-3. Whether or not this is restricted to mesenteric resistance arteries remains to be studied.

Further evidence for a relationship between caveolae numbers and myogenic constriction is provided by our present experiments with sham artery preparations treated with filipin and MCD. EM-analysis confirmed that acute treatment with these cholesterol-binding agents resulted in a marked reduction in caveolae numbers, similar to the number observed in CHF. Concomitantly, myogenic constriction was significantly increased to levels similar to those observed in CHF arteries. Thus, acute disruption of caveolae turns normal arteries into ‘CHF arteries’. Furthermore, CHF and acute treatment with cholesterol-disrupting agents seem to affect the same pool of caveolae, as the number of plasmalemmal caveolae and the level of myogenic constriction remained unchanged after treating CHF arteries with filipin or MCD. Collectively, our results provide evidence for a possible involvement of decreased caveolae numbers underlying increased myogenic constriction in mesenteric arteries in CHF.

It is interesting to compare our results on increased myogenic constriction following caveolae disruption to findings in caveolin-1 knockout mice, in which the reduction in number of caveolae leads to a decrease in myogenic constriction.10 Several mechanisms may explain this difference. First, caveolar disruption affects only about half of the caveolae, whereas no caveolae were present in the organs analysed from the knockout mice, i.e. lung, adipose tissue, diaphragm, kidney, and heart.10 Thus, the level of (particular) caveolae may be an important factor. Secondly, a major difference between the two models is the expression of caveolins. Whereas expression is absent in knock-out animals, the protein levels are unchanged when caveolae are disrupted by cholesterol depletion in cultured rat VSMCs (our unpublished data) and in tail artery,11 implying a cellular redistribution of the caveolins.12,13 Such an explanation suggests that cellular distribution of caveolin-1 might be a pivotal modulator of myogenic constriction. Additional studies need to be done to strengthen this notion.

To further investigate potential mechanisms that relate caveolae numbers with myogenic constriction in CHF, we explored the involvement of the AT1- and EGF-receptors. In CHF, the increased myogenic constriction was dependent on both AT1- and EGF-receptor activation, and the lack of a further decrease in myogenic constriction after combined blockade indicates interaction between these two receptors. Furthermore, we showed that AT1- and EGF- receptors are co-localized in the VSMCs of the mesenteric artery. This co-localization provides spatial and temporal possibility of cross-talk between these two receptors. It is widely believed that angiotensin II promotes cellular events by transactivation of the EGF-receptor through the AT1 receptor in VSMCs.14–17 We also demonstrated EGF-receptor transactivation via the AT1 receptor in increased myogenic constriction, in experiments with sub-threshold activation of AT1- and EGF-receptors. Interestingly, increased myogenic constriction in the presence of a sub-threshold concentration of EGF was selectively reversed in the present study by EGF-receptor inhibition, but not by AT1-receptor blockade. Conversely, however, increased myogenic constriction in the presence of a sub-threshold concentration of angiotensin II was reversed by both AT1- as well as EGF-receptor inhibition. Therefore, these data provide additional evidence for AT1–EGF-receptor transactivation in increased myogenic constriction in rat mesenteric artery. It could thus be assumed that increased myogenic constriction in the presence of a sub-threshold concentration of angiotensin II resembles CHF, as the effect was reversed by both AT1- as well as EGF-receptor inhibition and transactivation of EGF-receptor occurred in this process. This notion may be further strengthened by activation of downstream signals of both AT1 and EGF receptors. It has been shown that ERK exists downstream of EGF receptor transactivation induced by angiotensin II.18 Indeed, increased myogenic constriction in CHF was blocked by ERK inhibitor, suggesting that transactivation of the EGF receptor through the AT1 receptor does occur in an increased myogenic constriction in CHF (data not shown). In contrast, increased myogenic constriction in the presence of a sub-threshold concentration of EGF resembles acute disruption of caveolae, as it was solely reversed by EGF-receptor inhibition. Other evidence has also shown that caveolae-like microdomains are essential in this process of AT1-receptor transactivation of the EGF-receptor in VSMCs.5,14

One of the explanations for the discrepancy of involvement of AT1 and EGF-receptors in increasing myogenic constriction in these various experiments involves their difference in relationship to caveolae and caveolin. Whereas the inactive AT1-receptor is dispersed across caveolar and non-caveolar parts of the plasma membrane,19 and moves into caveolae upon stimulation,14,20 this translocation does not seem to govern receptor activation or internalization.21 Consequently, as observed in the present study, the effects of acute caveolar disruption on the function of the AT1-receptor are limited under normal conditions. In contrast, the EGF-receptor has been reported to be extensively localized in caveolae in non-stimulated cells22 and to autophosphorylate on caveolae disruption in the absence of the agonist,23–25 probably due to the release of EGF-receptor into small confined areas, leading to constitutive receptor activity.23 These data are in keeping with our finding that increased myogenic constriction evoked by cholesterol disrupting agents was sensitive to EGF-receptor inhibition. In addition, increased myogenic constriction due to a sub-threshold concentration of angiotensin II is sensitive to EGF receptor blockade and resembles the situation in CHF. Apparently, activation or activity of a limited number of AT1 receptors is sufficient to transactivate the EGF receptor and enhance myogenic constriction. It seems plausible, therefore, that the difference between CHF and sham arteries treated with filipin or MCD may be the AT1 receptor activity or density, giving rise to constitutive activity of the AT1 receptor in CHF. Although not studied in the vasculature in CHF as far as we know, several investigators have reported AT1 receptor density and/or expression to be increased in other tissues in different models of heart failure, including the currently employed rat MI model.26–28 Furthermore, the contribution of the reduction in caveolae numbers in CHF may be speculated upon. Caveolin is implicated in the insertion of the AT1 receptor in the plasma membrane,19 and reduction in caveolin gives rise to a reduced angiotensin II response.10 Consequently, a reduction in caveolae numbers in CHF, redistributing caveolin to the cytosol, may facilitate increased AT1 receptor trafficking to the plasma membrane,9 resulting in increased AT1 receptor surface numbers.

In summary, we found a marked decrease in VSMC plasmalemmal caveolae in mesenteric arteries of rats with experimental CHF, and propose increased AT1-receptor-mediated transactivation of the EGF-receptor as a result hereof as a contributor mechanism to increased myogenic constriction in CHF. We also showed a profound effect of acute experimental modulation of VSMC plasmalemmal caveolae numbers on the myogenic constriction response of small mesenteric artery preparations of normal rats, which involves solely EGF-receptor signalling/activity. These findings suggest a new role of caveolae in maintenance of myogenic constriction in resistance arteries, and provide a new view of caveolae as well as EGF-receptor transactivation as potential targets for therapeutic approaches in CHF. Therefore, our results have important implications in cardiovascular disease. Administration of caveolin-1 peptide has already shown cardioprotective effects in myocardial ischaemia–reperfusion and prevention of the development of pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular hypertrophy.29,30 For this reason, restoration of caveolae may indeed prove beneficial in CHF.

Funding

This study was financially supported by GUIDE (Groningen University Institute for Drug Exploration), Groningen, The Netherlands.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank B.J. Meijringh, A. van Buiten, and C.A. Kluppel for their excellent technical assistance, and E.H. Blaauw for expert electron microscopy work.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.Schrier RW, Abraham WT. Mechanisms of disease - Hormones and hemodynamics in heart failure. N Eng J Med. 1999;341:577–585. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908193410806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis MJ, Hill MA. Signaling mechanisms underlying the vascular myogenic response. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:387–423. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.2.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gschwend S, Henning RH, Pinto YM, de Zeeuw D, van Gilst WH, Buikema H. Myogenic constriction is increased in mesenteric resistance arteries from rats with chronic heart failure: instantaneous counteraction by acute AT(1) receptor blockade. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;139:1317–1325. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kagiyama S, Eguchi S, Frank GD, Inagami T, Zhang YC, Phillips MI. Angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy and hypertension are attenuated by epidermal growth factor receptor antisense. Circulation. 2002;106:909–912. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000030181.63741.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ushio-Fukai M, Hilenski L, Santanam N, Becker PL, Ma Y, Griendling KK, Alexander RW. Cholesterol depletion inhibits epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation by angiotensin II in vascular smooth muscle cells: role of cholesterol-rich microdomains and focal adhesions in angiotensin II signaling. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:48269–48275. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105901200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah BH. Epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation in angiotensin II-induced signaling: role of cholesterol-rich microdomains. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2002;13:1–2. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(01)00539-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fielding CJ. Caveolae and signaling. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2001;12:281–287. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200106000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darblade B, Caillaud D, Poirot M, Fouque M, Thiers JC, Rami J, Bayard F, Arnal JF. Alteration of plasmalemmal caveolae mimics endothelial dysfunction observed in atheromatous rabbit aorta. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;50:566–576. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00251-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ratajczak P, Damy T, Heymes C, Oliviero P, Marotte F, Robidel E, Sercombe R, Boczkowski J, Rappaport L, Samuel JL. Caveolin-1 and -3 dissociations from caveolae to cytosol in the heart during aging and after myocardial infarction in rat. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;57:358–369. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00660-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drab M, Verkade P, Elger M, Kasper M, Lohn M, Lauterbach B, Menne J, Lindschau C, Mende F, Luft FC, Schedl A, Haller H, Kurzchalia TV. Loss of caveolae, vascular dysfunction, and pulmonary defects in caveolin-1 gene-disrupted mice. Science. 2001;293:2449–2452. doi: 10.1126/science.1062688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dreja K, Voldstedlund M, Vinten J, Tranum-Jensen J, Hellstrand P, Sward K. Cholesterol depletion disrupts caveolae and differentially impairs agonist-induced arterial contraction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:1267–1272. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000023438.32585.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun RJ, Muller S, Zhuang FY, Stoltz JF, Wang X. Caveolin-1 redistribution in human endothelial cells induced by laminar flow and cytokine. Biorheology. 2003;40:31–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ballard-Croft C, Locklar AC, Kristo G, Lasley RD. Regional myocardial ischemia-induced activation of MAPKs is associated with subcellular redistribution of caveolin and cholesterol. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H658–H667. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01354.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ushio-Fukai M, Zuo L, Ikeda S, Tojo T, Patrushev NA, Alexander RW. cAbl tyrosine kinase mediates reactive oxygen species- and caveolin-dependent AT1 receptor signaling in vascular smooth muscle: role in vascular hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2005;97:829–836. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000185322.46009.F5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suzuki H, Motley ED, Frank GD, Utsunomiya H, Eguchi S. Recent progress in signal transduction research of the angiotensin II type-1 receptor: protein kinases, vascular dysfunction and structural requirement. Curr Med Chem Cardiovasc Hematol Agents. 2005;3:305–322. doi: 10.2174/156801605774322355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higuchi S, Ohtsu H, Suzuki H, Shirai H, Frank GD, Eguchi S. Angiotensin II signal transduction through the AT(I) receptor: novel insights into mechanisms and pathophysiology. Clin Sci. 2007;112:417–428. doi: 10.1042/CS20060342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohtsu H, Dempsey PJ, Frank GD, Brailoiu E, Higuchi S, Suzuki H, Nakashima H, Eguchi K, Eguchi S. ADAM17 mediates epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation and vascular smooth muscle cell hypertrophy induced by angiotensin II. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:E133–E137. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000236203.90331.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eguchi S, Dempsey PJ, Frank GD, Motley ED, Inagami T. Activation of MAPKs by angiotensin II in vascular smooth muscle cells. Metalloprotease-dependent EGF receptor activation is required for activation of ERK and p38 MAPK but not for JNK. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:7957–7962. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008570200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wyse BD, Prior IA, Qian HW, Morrow IC, Nixon S, Muncke C, Kurzchalia TV, Thomas WG, Parton RG, Hancock JF. Caveolin interacts with the angiotensin II type 1 receptor during exocytic transport but not at the plasma membrane. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:23738–23746. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212892200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ishizaka N, Griendling KK, Lassegue B, Alexander RW. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor - Relationship with caveolae and caveolin after initial agonist stimulation. Hypertension. 1998;32:459–466. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.32.3.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaborik Z, Szaszak M, Szidonya L, Balla B, Paku S, Catt KJ, Clark AJL, Hunyady L. beta-arrestin- and dynamin-dependent endocytosis of the AT(1) angiotensin receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59:239–247. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smart EJ, Ying YS, Mineo C, Anderson RGW. A detergent-free method for purifying caveolae membrane from tissue-culture cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10104–10108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.22.10104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lambert S, Vind-Kezunovic D, Karvinen S, Gniadecki R. Ligand-independent activation of the EGFR by lipid raft disruption. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:954–962. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Westover EJ, Covey DF, Brockman HL, Brown RE, Pike LJ. Cholesterol depletion results in site-specific increases in epidermal growth factor receptor phosphorylation due to membrane level effects. Studies with cholesterol enantiomers. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:51125–51133. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304332200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pike LJ, Casey L. Cholesterol levels modulate EGF receptor-mediated signaling by altering receptor function and trafficking. Biochemistry. 2002;41:10315–10322. doi: 10.1021/bi025943i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun Y, Weber KT. Angiotensin-II receptor-binding following myocardial-infarction in the rat. Cardiovasc Res. 1994;28:1623–1628. doi: 10.1093/cvr/28.11.1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoshimura R, Sato T, Kawada T, Shishido T, Inagaki M, Miyano H, Nakahara T, Miyashita H, Takaki H, Tatewaki T, Yanagiya Y, Sugimachi M, Sunagawa K. Increased brain angiotensin receptor in rats with chronic high-output heart failure. J Card Fail. 2000;6:66–72. doi: 10.1016/s1071-9164(00)00013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mento PF, Pica ME, Hilepo J, Chang J, Hirsch L, Wilkes BM. Increased expression of glomerular AT1 receptors in rats with myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:H1247–H1253. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.4.H1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jasmin JF, Mercier I, Dupuis J, Tanowitz HB, Lisanti MP. Short-term administration of a cell-permeable caveolin-1 peptide prevents the development of monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular hypertrophy. Circulation. 2006;114:912–920. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.634709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Young LH, Ikeda Y, Lefer AM. Caveolin-1 peptide exerts cardioprotective effects in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion via nitric oxide mechanism. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H2489–H2495. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.6.H2489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]