Abstract

Converging research indicates that foster children with maltreatment histories have more behavior problems and poorer peer relations than biologically reared, nonmaltreated youth. However, little is known about whether such deficits in peer relations work independently or as a result of increased behavior problems, and whether outcomes for foster children differ by sex. To address these questions, multiagent methods were used to assess peer relations at school entry among maltreated foster children and a comparison sample of low-income, nonmaltreated, biologically reared children (N = 121). Controlling for caregiver-reported behavior problems prior to school entry, results from a multigroup SEM analysis suggested that there were significant relationships between foster care status and poor peer relations at school entry and between foster care status and the level of behavior problems prior to school entry for girls only. These Sex × Foster care status interactions suggest the need for gender-sensitive interventions with maltreated foster children.

Keywords: foster care, maltreatment, peer relations, sex differences, school entry

When children enter formal educational settings, they are expected to possess competencies that make it possible for them to respond to the demands of the school environment. Children who lack basic social skills and fail to develop successful peer relations during school entry are at greater risk for conduct problems, peer rejection, and academic failure throughout childhood and adolescence (Brendgen, Vitaro, Bukowski, Doyle, & Markiewicz, 2001; Dishion 1990; Snyder et al., 2005). Foster children are at particularly high risk for difficulties in this area. There are currently more than 500,000 foster care children in the United States, with more than 230,000 children entering foster care yearly (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2000). Beginning in early childhood, foster children show deficits on indicators of behavioral and mental health (Pilowsky, 1995). Early placement in foster care—prior to age 5—appears to be particularly detrimental to later outcomes (Keiley, Howe, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 2001). Once foster children enter school, they show more behavior problems than nonmaltreated, biologically reared children and fare worse than their peers on indicators of school performance, including achievement, peer competence, high school completion rates, and special education service needs (Wodarski, Kurtz, Gaudin, & Howing, 1990). Though extensive behavioral and educational disparities among foster children have been well documented, few studies have examined whether behavior problems that emerge during the preschool period lead to subsequent poor outcomes or whether foster care elicits unique effects on peer relations over and above those associated with behavior problems.

Two lines of evidence are relevant to understanding the disparities in outcomes for foster children: studies of maltreated youth (who may or may not be in foster care) and studies of children in foster care (who may or may not have experienced maltreatment). Studies in both areas generally reveal very high rates of behavioral maladjustment. For example, Clausen, Landsverk, Ganger, Chadwick, and Litrownik (1998) found that 50% of a representative sample of foster children had CBCL scores at or above the borderline clinical range. This rate is 2.5 times greater than the rate expected in a community sample. Similarly, in a longitudinal study of three groups of children (foster children, maltreated children who remained in the home, and nonmaltreated, biologically reared community children), Lawrence, Carlson, and Egeland (2006) found that foster children had more behavioral problems than the community comparison children. They also found that teachers rated foster children and maltreated children not placed in foster care as having significantly more externalizing problems than the community children (the foster care and maltreated groups did not differ significantly from each other). Other studies have shown greater risk for aggression, conduct disorders, and delinquency for maltreated youth (Lansford et al., 2002; Lynch & Cicchetti, 1998; Stouthamer-Loeber, Loeber, Homish, & Wei, 2001) and that the negative effects of maltreatment interact with family characteristics such as parental decision making and early stress (Lansford et al., 2006).

Studies examining peer relations in maltreated children and foster children have found a consistent association between maltreatment/foster care and poor peer relations (Bolger, Patterson, & Kupersmidt, 1998; Fantuzzo, Weiss, Atkins, Meyers, & Noone, 1998; Manly, Kim, Rogosch, & Cicchetti, 2001; Parker & Herrera, 1996; Rogosch & Cicchetti, 1994). Specific domains of peer deficits for maltreated children and foster children that have been investigated include having fewer friends and having friends that are significantly younger then they are (Salzinger, Feldman, Hammer, & Rosario, 1993), having more conflictual and less intimate peer relations (Parker & Herrera, 1996), having fewer positive and more negative peer nominations (Salzinger et al., 1993), and exhibiting disruptive social behavioral patterns that affect friendship formation (Cicchetti & Lynch, 1995). Using observational methodology, Parker and Herrera (1996) found that maltreated children displayed less intimacy and more conflict when interacting with their best friend compared to nonmaltreated children with their best friend.

One issue that has not been fully developed in prior research is whether poor peer relations are a simply a biproduct of foster children’s behavior problems, as studies of biologically reared youth would suggest (Dishion, Eddy, Haas, Li, & Spracklen, 1997). This is perhaps the most parsimonious explanation of the poor peer relations in foster children. Alternatively, some aspects of foster children’s observed difficulty with peer relationships might not be associated with behavior problems. The first aim of this study, therefore, was to examine whether being in foster care was associated with poor peer relations at school entry, controlling for behavior problems. It is important from the outset to differentiate an association between foster care and poor peer relations from a causal relationship. We did not intend to examine whether placement in foster care was the root cause of poor peer relations. Rather, we sought to begin a process of explicating foster children’s general psychosocial difficulties with greater specificity than previously attempted.

Gender-Sensitive Processes in the Development of Peer Relations

Our second goal was to examine whether the association between foster care and poor peer relations differs by sex. There is evidence that some developmental processes have a greater influence on peer relations for girls than for boys during the developmental period marking the transition to school. At school entry, affiliating with classmates who exhibit externalizing problems has been shown to lead to more problematic outcomes for girls than for boys (Hanish, Martin, Fabes, Leonard, & Herzog, 2005). Moreover, exhibiting antisocial behavior has been shown to lead to increased peer victimization for girls but not for boys (Snyder et al., 2003). Further, social status at school entry appears to mediate the association between early childhood characteristics and later conduct problems for boys; for girls, however, the effects of social status appear additive (Snyder, Prichard, Schrepferman, Patrick, & Stoolmiller, 2004).

Studies of children’s sex role development offer one explanation for why some developmental processes might have a differential impact on peer relations by sex. By age 3, boys and girls show a preference for same-sex playmates and often engage in sex-specific play activities with their peers (Jacklin & Maccoby, 1978; Maccoby, 1990). For example, boys tend to play in larger peer groups and form friendships that are based on a mutual preference for a specific activity. Conversely, girls tend to form close, intimate relationships with one or two other girls and to engage in emotion-focused play and interpersonal role-playing (Erwin, 1985; Kraft & Vraa, 1975). In addition, parents tend to reinforce young children’s sex-typed play and communication behaviors at a much greater rate than non–sex-typed play and communication behaviors (Fagot & Hagan, 1991). One consequence of these early childhood sex differences in peer play styles and peer preferences is that girls can become more attuned to emotion-based characteristics of relationships than boys. In fact, girls as young as age 3 can interpret others’ emotional states more readily than boys (Peterson & Biggs, 2001). These play preferences and interpersonal styles may make the transition to foster care more disruptive for girls than for boys.

In this paper, we test a theoretical model focusing on how foster care might differentially impact the quality of girls’ and boys’ peer relations at school entry. The study involved a sample of maltreated foster children and nonmaltreated, biologically reared community children studied pre– and post–school entry. Because behavior problems are a common precursor to peer rejection and peer difficulties (Dishion et al., 1997), and because rates of behavior problems in foster children are considerably higher than in non–foster children, we controlled for the effects of behavior problems on peer relations to examine the unique outcomes of foster care status. Given girls’ differential interaction styles, we hypothesized that foster care status would be more strongly associated with compromised peer relations for girls than for boys.

In most prior studies, foster care status and child maltreatment have not been treated as distinct phenomena. Studies of maltreated children often include some foster children, and studies of foster children typically do not include information about children’s maltreatment. In the present study, although sample size and a tendency for many children to have experienced multiple forms of maltreatment prevented an examination of the outcomes of specific types of maltreatment separately from foster care status, the foster care sample in this study is comprised of children who have all experienced maltreatment (as ascertained from child protective service records). The methodological overlap between maltreatment and foster care status in the sample is addressed in greater detail in the Discussion section.

Method

Participants

The participants were enrolled in a longitudinal study that included maltreated children who had been removed from their family of origin and placed in foster care (FC; n = 117) and a community comparison group of nonmaltreated, biologically reared children (CC; n = 60). Participants were preschool-aged at the time of enrollment into the study. Recruitment occurred over 4 years. FC families were recruited in collaboration with staff members at the Lane County Branch of the Oregon Department of Human Services, Child Welfare Division, who referred all 3- to 5-year-olds entering new foster placements in the county to the study. Caseworker (i.e., a foster child’s legal guardian in Oregon) consent and foster parent consent were obtained prior to enrolling children in the study. At entry into the study, the FC children had been in their current foster placement an average of 31 days (SD = 9). At the time the school entry data were collected, FC children had experienced an average of 3.5 nonrelative foster placements and had been in foster care an average of 515 days (SD = 324).

To verify that the FC children had been maltreated, we coded their child protective services case files using the system developed by Barnett, Manly, and Cicchetti (1991). The most prevalent maltreatment experiences included emotional maltreatment (90%), lack of supervision (89%), failure to provide (82%), physical abuse (32%), and sexual abuse (26%).

CC families were recruited via advertisements in local newspapers and newsletters and via flyers posted at local supermarkets, daycare centers, and Head Start classrooms. The CC family participation criteria were developed to match the demographic characteristics of the FC children’s biological family (excluding maltreatment) and included the following: no previous parental or child involvement with child welfare services (verified via child protective service records), child lived consistently with at least one biological parent, annual household income was less than $30,000, and parental education level was less than a 4-year college degree. No founded reports of abuse or neglect existed for the CC families.

All children were part of a randomized intervention trial examining the efficacy of a treatment foster care program (Fisher, Burraston, & Pears, 2005). In the trial, foster children were randomly assigned into treatment or services-as-usual conditions. The intervention, Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care for Preschoolers (MTFC-P) was delivered via a treatment team approach and involved providing the following: (a) support and consultation to foster parents; (b) individual and group treatment for children to address behavioral and psychosocial difficulties and to support prosocial skill development; (c) coordination with other treatment providers, educational settings, and the child welfare caseworker involved in the case; and (d) parenting support to birth and adoptive parents. No significant differences between the two foster care conditions on the behavior problem measure and the peer relations measures were observed in the data analyzed for this paper (the study is ongoing). Consequently, the children were combined into a single FC group for the present analyses. Detailed intervention outcomes can be found in Fisher et al. (2005).

One hundred and forty-one families (80% of the original sample) participated in the school entry assessment. In the present analyses, FC youth who had reunified with their biological caregiver prior to school entry assessment were excluded from analysis (n = 20). This exclusion criterion was implemented to retain a tight focus on outcomes for maltreated foster children. There were no significant differences on the measures used in this report between FC children who had reunified (and were excluded from the current analysis) and FC children who remained in foster care. The resulting sample was comprised of 65 FC children (32 boys and 33 girls) and 56 CC children (30 boys and 26 girls). The ethnic composition of the sample was representative of the geographic region from which it was drawn: 88% Caucasian (8% being of Hispanic or Latino descent), 3% African American, 8% Native American, and 1% Pacific Islander. The FC and CC samples did not differ by mean child age, girl-to-boy ratio, or ethnicity. Mean child age at the school entry assessment was 5.9 years (SD = .52).

Procedure

In the longitudinal study from which these data were drawn, children and their caregivers completed in-person assessments every 3 months over a 24-month period. The assessment protocol also included sets of two telephone interviews, collected on consecutive dates every 3 months, to measure child behavior problems and parenting stress. In addition, data were collected from the child and the child’s teacher in the fall and spring of the kindergarten year and in the spring of subsequent school years. For the present report, we focused on the first school assessment and the two telephone interviews that were conducted immediately prior to the school entry assessment. The average length of time between the set of telephone interviews and the school entry assessment was 66 days (SD = 168). For the school assessments, teachers completed a set of mailed questionnaires, and children were interviewed in person about their peer relationships and school behaviors. Teachers and caregivers were paid for their participation, and children were given small toys as prizes.

Measures

Child behavior problems

To measure child behavior problems, The Parent Daily Report checklist (PDR; Chamberlain & Reid, 1987) was administered by telephone to the child’s caregiver on two consecutive weekdays prior to the school entry assessment. The structure of the PDR (i.e., repeated administrations in which caregivers focus on the past 24 hours only) is intended to reduce systematic and random sources of measurement error to increase the validity and reliability of the caregiver-reported child problem behaviors. During each call, a trained interviewer asks, “Thinking about (child’s name), during the past 24 hours, did any of the following behaviors occur?” Caregivers are asked to respond in a Yes/No format to 52 common child behaviors (e.g., arguing, fighting, depression/sadness, sleep problems, and tantrums). The number of affirmative responses is then summed for each call, and a mean behavior problem score is computed by averaging the total number of behavior problems from both calls. The correlation between the behavior problem score in the two calls for this report was .86 (M = 5.6 behaviors, SD = 5.3 behaviors, range = 0–24 behaviors).

The concurrent validity of the PDR has been demonstrated in association with a number of measures of child and family functioning, including live observations of family interactions coded in the home (Forgatch & Toobert, 1979; Patterson, 1976) and parents’ global ratings of child behavior (Becker, Madsen, Arnold, & Thomas, 1967). In addition, the PDR has been demonstrated to be a reliable indicator of treatment outcome success (Chamberlain, Moreland, & Reid, 1992; Chamberlain & Reid, 1991).

Peer relations

Four measures of peer relations were collected: two verbally administered, child-report measures to assess peer rejection and peer loneliness and two mailed teacher-report measures to assess peer competence and peer social skills measures. The first child-report measure, the 24-item Loneliness in Children Scale (Asher & Wheeler, 1985), measures feelings of loneliness, feelings of social adequacy, subjective estimations of peer status, and beliefs about whether important peer relationship needs are being met. The 16-item School Loneliness subscale was computed for the present study by summing the scale items (α = .51). This measure has demonstrated sound reliability and predictive validity in other samples (Asher & Wheeler, 1985). Children used a 3-point Likert scale—1 (Yes), 2 (Sometimes), and 3 (No)—to respond to items such as easy to make new friends, have other kids to talk to at school, and can find a friend when you need one.

Children were also administered the Seattle Personality Inventory for Children, which was created for the Fast Track Project and was derived from items from the Seattle Personality Questionnaire for Young School-Aged Children (Kusche, Greenberg, & Beilke, 1988), the School Loneliness Scale (Asher & Wheeler, 1985), and the School Sentiment Scale (Ladd, 1990). The measure contains 44-items rated on a 3-point Likert scale—0 (No), 1 (Yes), and 3 (Don’t know). Scores of 3 were considered missing data for the purposes of scale composition. The measure is comprised of eight subscales, one of which pertains to peer loneliness and rejection at school: School Loneliness. The five items on the School Loneliness subscale were summed to create a scale score (α = .60) comprised of items such as hard to make friends at school, have kids to play with at school (reverse coded), and unhappy at school. The correlation between the two child-report measures was .48 (p < .001).

Teachers completed the Walker-McConnell Scale of Social Competence and School Adjustment, Elementary version (Walker & McConnell, 1995) using a 5-point Likert scale—1 (Never) to 5 (Frequently). This 43-item measure includes items such as compromises with peers when situations call for it, plays or talks with peers for extended periods of time, is sensitive to the needs of others, and invites peers to play or share activities. The total score was computed based on the sum of the 43 items (α = .98).

Teachers also completed the 12-item Social Competence Scale (Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 1995), which was originally adapted from instruments by Kendall and Wilcox (1979) and by Gersten (1976). This measure assesses children’s prosocial behaviors, communication skills, and self-control on a 5-point Likert scale—0 (Not at all) to 4 (Very well). We used the 6-item Prosocial/Communications Skills subscale, which summed scores on items such as the following: resolves problems with friends/siblings, shares things with others, and can give suggestions/opinions without being bossy. Inter-item consistency was very good (α = .93). The correlation between the two teacher-report measures was .87 (p < .001).

Analysis Plan

To evaluate the hypotheses that being in foster care would be associated with poor peer relations even after controlling for problem behavior and that these effects would be greater for girls than boys, we conducted a multiple groups path analysis in structural equation modeling (SEM). We chose SEM for several reasons. First, it allowed us to specify the criterion construct as a higher latent variable minimizing measurement error and reporter bias at two levels. The convergence or communality among peer relations indicators is first estimated within reporters at the first order level (e.g., a child and teacher reported latent variable). At the higher order level, the communality among child and teacher reported latent variables is estimated for peer relations partialling measurement error.

A second advantage of SEM was that it allowed us to directly test hypotheses with multiple group equality constraints. After specifying a latent variable measurement model of peer relations, the criterion variable is regressed on predictors comparing a model for boys and girls. Tests of path coefficients then examined effects of foster care by sex using equality constraint significance tests of the null hypothesis (no differences) versus the hypotheses that coefficients differ by sex (e.g., a moderating effect of sex). Equality constraints also test measurement invariance for the peer relations factor between boys and girls (see Meredith, 1993).

The third advantage of SEM was that it allowed us to use full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML) to permit missing data or partial data cases. FIML is an iterative model-based estimation procedure that allows for missingness and assumes multivariate normality that maximizes the likelihood of the model given the observed data available (Arbuckle, 1996). FIML uses all information of observed data including information about the mean and variance of missing portions of a variable based on the observed portions of other variables in the covariance matrix. Meeting assumptions of random missingness, FIML has greater statistical efficiency for computing standard errors compared to mean-imputation, list-wise, and pair-wise deletion methods (Wothke, 2000).

FIML is recommended when the data is missing at random (MAR; Schafer & Graham, 2002). MAR allows the probabilities of missingness to depend on observed data but not on missing data. A special case of MAR, missing completely at random (MCAR), occurs when the missing data distribution does not depend on the observed data as well. Therefore, MCAR data introduces no bias in estimates due to missing data (see discussion in Schafer & Graham, 2002). A missing-values analysis was conducted on the main study variables and categorical covariates. Little’s chi-square MCAR test indicated no differences between partial and complete data cases, χ2(18) = 23.11, p = .19, suggesting the appropriateness of the FIML approach.

Results

Bivariate correlations, means, and standard deviations among study variables are shown in Table 1 by sex. The correlations suggested somewhat greater cross-rater consistency for girls than for boys. As is shown in Table 1, the child- and teacher-reported measures correlated well within rater for boys, but there were no significant cross-rater associations. In contrast, all but one of the cross-rater correlations and all within-rater correlations were significant for girls. We next specified a higher order latent variable estimating convergence among reporters, controlling for measurement error. In this model, sex was coded as 1 (Boys) or 2 (Girls) and foster care status was coded as 1 (FC children) or 0 (CC children).

Table 1.

Bivariate Correlations, Means, and Standard Deviations by Sex of Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | |||||||

| 1. School lonelinessa | — | .43*** | −.081 | −.01 | .15 | 29.28 | 4.23 |

| 2. School lonelinessb | — | −.25† | −.12 | −.04 | 1.08 | 1.19 | |

| 3. Social competencec | — | .86*** | −.23† | 150.71 | 33.63 | ||

| 4. Social competenced | — | −.08 | 15.01 | 5.37 | |||

| 5. Behavior problemse | — | 5.23 | 5.41 | ||||

| Girls | |||||||

| 1. School lonelinessa | — | .56*** | −.38** | −.41** | −.03 | 28.72 | 3.96 |

| 2. School lonelinessb | — | −.25† | −.27* | .11 | 1.20 | 1.18 | |

| 3. Social competencec | — | .86*** | −.08 | 167.08 | 33.54 | ||

| 4. Social competenced | — | −.21 | 16.38 | 5.63 | |||

| 5. Behavior problemse | — | 5.97 | 5.12 | ||||

Note. Measured via Loneliness in Children Scale.

Measured via Seattle Personality Inventory for Children.

Measured via Walker-McConnell Scale of Social Competence and School Adjustment.

Measured via Social Competence Scale.

Measured via Parent Daily Report.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .05.

p < .001.

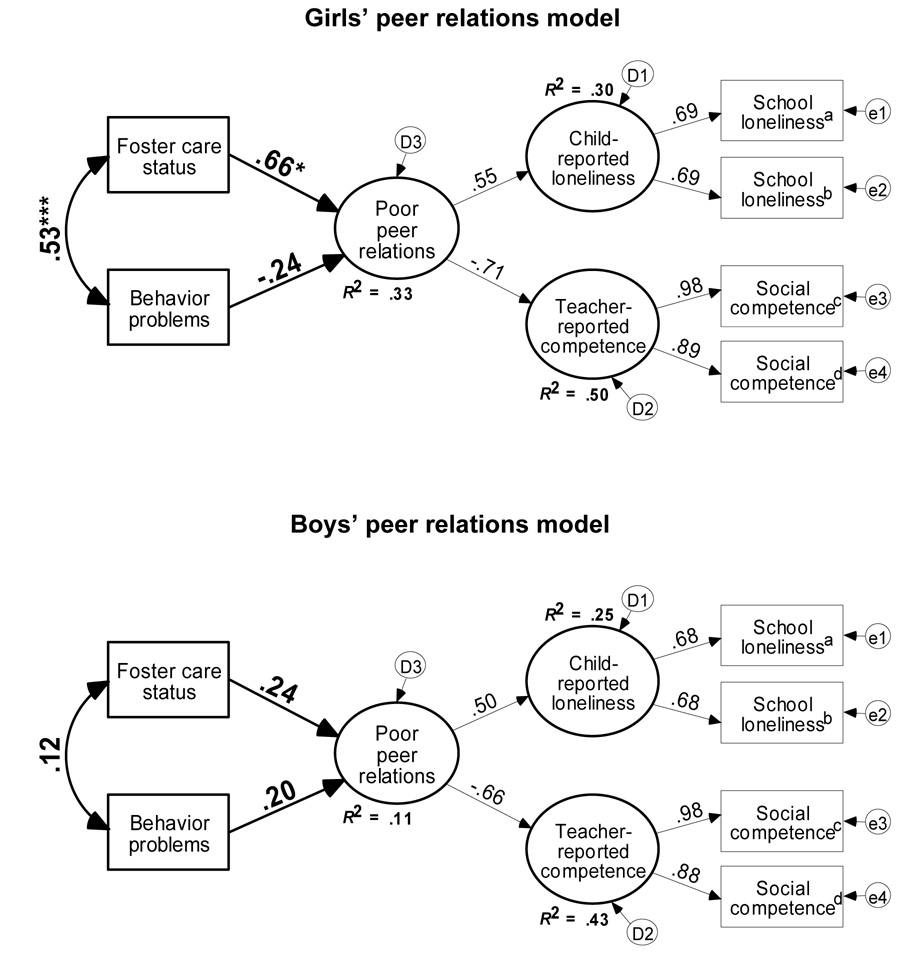

Focusing on the main hypotheses, the higher order latent variable was regressed on foster care status and behavior problems, thereby estimating the effect for foster care on peer relations while controlling for behavior problems. Multiple group models were estimated simultaneously. Equality constraints were tested by first restricting all the means, intercepts, variances, covariances, and path coefficients to be equal among boys and girls. The second step incrementally freed path coefficients that were exogenous to the dependent latent variable, thereby evaluating differential effects by sex and structural invariance for the measurement of peer relations as recommended by Meredith (1993). A full constraints model obtained adequate fit, but the chi-square minimization test was significantly different than the observed data, χ2 = 50.49(33), p = .02, χ2/df = 1.53, CFI = .91, RMSEA = .07. (This verifies that the specified theoretical associations in the model do not differ from the observed covariance matrix.) Based on a series of nested model comparisons, the best fitting model imposed equality constraints on the measurement loadings, intercepts, and variances but freed three paths among the predictors. Results are shown in Figure 1, χ2 = 40.12(30), p = .10, χ2/df = 1.33, CFI = .95, RMSEA = .05. In this model, the chi-square minimization p value was greater than .05, the comparative fit index was .95, and the overall root mean square errors were lower. The test of freeing the exogenous paths between boys and girls obtained a significant improved fit for 3 degrees of freedom, Δχ2 = 10.37(3), p = .01.

Figure 1.

Higher order structural equation path models estimating effects of foster care status on peer relations using multiple groups modeling by sex controlling for behavior problems.

Note. Paths are standardized beta coefficients using full information maximum likelihood estimates, χ2 = 40.12(30), p = .10, χ2/df = 1.33, CFI = .95, RMSEA = .05.

aMeasured via Loneliness in Children Scale. bMeasured via Seattle Personality Inventory for Children. cMeasured via Walker-McConnell Scale of Social Competence and School Adjustment. dMeasured via Social Competence Scale. eMeasured via Parent Daily Report.

*p < .05, ***p < .001.

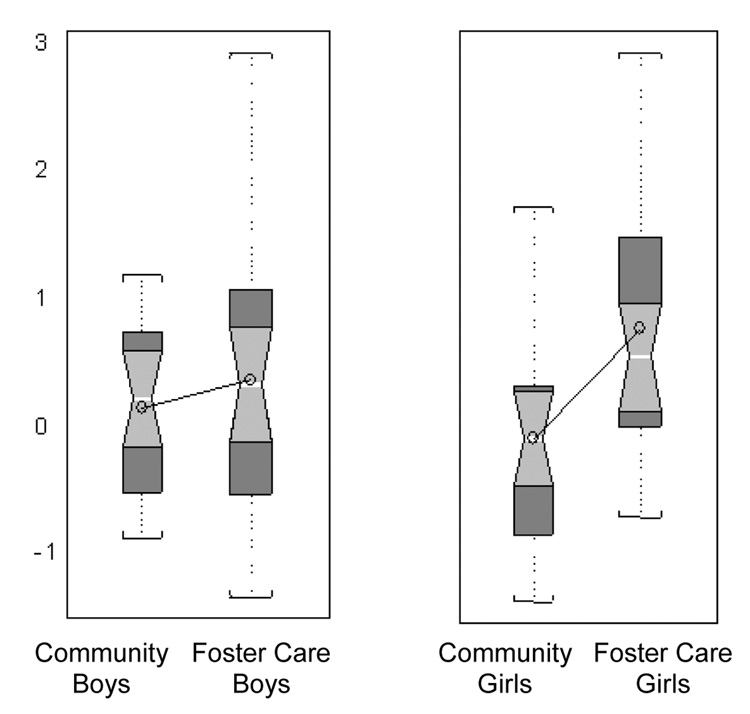

Controlling for initial behavior problems, the final model indicated that foster care had a significant association with poorer peer relations for girls, β = .66, p < .05, but not for boys; thereby supporting the hypothesis that girls’ peer relations are more vulnerable to the effects of foster care. Behavior problems were also significantly correlated with foster care status for girls, r = .53, p < .001, but not for boys. Finally, the effect of the behavior problems control variable was opposite in sign but was not significantly different from zero as a predictor for either sex. To illustrate the significant interaction effect for the vulnerability of girls, the estimated Foster care status × Sex effect for peer relations was plotted in Figure 2 using a factor score.

Figure 2.

Plot of poor peer relations by foster care status and sex.

Note. Distributions are boxplots with indented innerquartile range with white band representing the median. The lines connecting circles represent mean comparisons between the CC and FC groups.

Discussion

Prior studies have suggested that foster children fare worse than their peers across a broad spectrum of functional domains, including psychosocial adjustment, educational achievement, emotional and cognitive development, and physical health and well being (Clausen et al., 1998; Landsverk & Garland, 1999; Pears & Fisher, 2005a, 2005b). Mean level comparisons between the foster children and the community children in the present study confirmed that foster care appears to have a detrimental impact on peer relations and behavior problems: ANOVA comparisons of foster care status (not presented here) were significant for 3 of the 4 peer relations variables and for the behavior problems measure. The purpose of the present study, however, was to go further than describing a general domain of risk for foster children in two ways. First, we controlled for behavior problems when examining peer relations. Second, we examined sex differences in the effects of foster care on peer relations. Explicating the general deficit model in these two ways provided new insight about how the outcomes and processes leading to poor peer relations for youth in foster care may differ by sex.

Perhaps the most parsimonious explanation for foster children’s poorer peer relations is that their tendency to have behavior problems leads to rejection by peers. Although there is ample evidence that foster children have higher rates of behavior problems, our results suggest that there are dimensions of the foster care experience other than behavior problems that are associated with foster girls feeling, and appearing to their teachers, as socially isolated and rejected by peers. Our results support the hypothesis that maltreated foster girls show poorer peer relations than nonmaltreated community girls, even when controlling for the effects of behavior problems. In addition, foster girls had significantly more behavior problems than did community girls. In contrast, foster care status was not significantly related to boys’ peer relations or to boys’ behavior problems, and the model fit comparisons suggested that separate statistical models were required for boys versus girls because of these differences.

Without additional research, we can only speculate as to the reasons for the differential effects for girls. One possible mechanism is that maltreatment and foster care experiences have a particularly negative effect on the domain of peer relations for girls as compared to boys. Girls are more commonly the victims of sexual abuse (Walker, Carey, Mohr, Stein, & Seedat, 2004); perhaps the betrayal of trust that occurs with sexual abuse adversely affects girls’ ability to develop successful peer relations (Becker-Blease & Freyd, 2005; Freyd, 1994). The associated caregiver transitions accompanying placement in foster care might also lead to subsequent detrimental effects for girls. For example, girls are more adversely affected by disruptions in caregiving (Hetherington & Clingempeel, 1992), which might increase their difficulty in establishing successful peer relationships.

A second set of mechanisms that possibly explains this differential impact on girls involves factors such as a lack of prosocial skills, developmental delays, emotion understanding deficits, and stigmatization. Lacking adequate prosocial models, frequent school and living transitions, and lacking a sense of security and stability at home might contribute to prosocial skill deficits. In addition, foster children in this age group show high rates of developmental delays (Klee, Kronstadt, & Zlotnick, 1997; Pears & Fisher, 2005a) and deficits in emotional understanding and theory of mind (Pears & Fisher, 2005a). Difficulty reading the emotional cues of their peers could produce significant impairment in the development of foster children’s positive peer relationships. Put simply, foster girls’ lack of prosocial skills, developmental delays, and emotion understanding deficits might make them developmentally or socially unprepared to achieve positive connections with peers when they enter school. Such factors might not be as influential for foster boys in developing positive peer relationships. Other variables might have direct effects on girls’ peer relations at school entry—for example, teacher stigmatization in response to a girl’s foster care status or inadvertent events that highlight differences between a girl and her non–foster care peers (e.g., family night at school and activities that involve drawing a picture of your family). These experiences might compound foster girls’ sense of being different from others and might impact their peer relations, whereas they might be less centrally influential for foster boys.

Our results suggest the importance of examining outcomes for foster children by sex. Although we replicated a general deficit model showing that foster children have poorer peer relations than community children, the results of the multigroup analyses suggest that the relationship between foster care status and peer relations might be specific to girls during this age period. It is important not to overlook what these results suggest for boys. For example, because boys’ peer relations did not differ by foster care status, male gender could be seen as a protective factor in regard to foster boys’ peer relations. Alternatively, perhaps the same effects observed for the girls in this study occur for boys later in development. As children enter middle childhood, for example, shifts occur in the selection of friends and playmates, with personality and individual characteristics becoming more important and mutual activities becoming less important (Damon, 1977). Future research could consider whether peer relations trajectories among foster boys diverge later in childhood. If this were the case, it might be important to target boys’ peer relations at school entry (or earlier) to prevent such a divergence. In any case, this study represents a first step toward understanding sex differential outcomes for foster children; additional research is needed to replicate and extend the present findings.

Implications for Intervention

A conservative conclusion that can be drawn from the present results is that intervention efforts should consider focusing on girls in foster care. Given that the girls in foster care in this study fared worse any other group, programs that screen and provide services for these girls are clearly needed to prevent the more severe gender disparities often seen in juvenile justice youths’ peer relations (Leve & Chamberlain, 2005). Furthermore, until the underlying causes of poor peer relations among girls in foster care are specified, programming should focus on basic social skill development.

In a longitudinal study, Bolger et al. (1998) found evidence the positive effects of peer relations: Having a good friend was associated with increases in self-esteem for some maltreated children. Interventions that allow for multiple opportunities to practice peer skills with high rates of feedback from adults (praise for positive behavior and limit setting for negative behavior) could improve foster children’s social readiness for school and improve peer relations and well-being. In addition, given the likelihood of developmental delays among many foster children, interventions should initially target simple and easily acquired skills, focusing on more complex skills as competencies develop.

As with many high-risk groups, not all foster children require such interventions; many children are resilient despite their experiences. Thus, policies and programming should emphasize the development of systematic and easily implemented screening programs to identify children needing to improve their peer relations. Child welfare system staff members could administer such screening tools in the months prior to kindergarten. By identifying these children, the economic and personnel demands on the child welfare system needed to improve foster children’s peer relations could reach an obtainable range.

Limitations and Future Directions

Our results should be considered in light of several limitations. First, although the analyses benefited from the use of multimethod, multiagent data, it is possible that some children in our study did not fully comprehend the questions asked. This may have been more likely for boys, given the lower cross-rater convergence for boys than for girls. To counterbalance this potential challenge, our analysis strategy emphasized convergence between teacher and child informants, and included caregiver-reported behavior problems. Nevertheless, there are limitations to child-reported peer measures in 5- and 6-year-olds, particularly in high-risk populations. Second, the separate effects of maltreatment and placement in foster care were not examined. In our sample, all of the foster children had been maltreated; it remains for future research to disentangle these issues and to address whether the severity, type (e.g., sexual abuse or neglect), duration, and age at onset of maltreatment exert effects on foster children’s’ peer relations and whether these associations differ by sex.

Given the multiple potential explanations for the foster girls’ poorer peer relations, additional research could also focus on disentangling the underlying mechanisms of these effects. In addition to examining the differential effects of various dimensions of maltreatment (e.g., type or severity), other research has linked maltreatment to internalizing and externalizing symptomatology through its influence on social competence (Kim & Cicchetti, 2004). Although identifying the higher risk for girls might be helpful in targeting girls for assessment and intervention, a better understanding of the underlying mechanisms associated with maltreatment and other variables might help to inform a gender-sensitive intervention, thus better addressing the needs of these children.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by R01 MH059780, NIMH, U.S. PHS. Additional support was provided by the following grants: R01 MH054257, NIMH, U.S. PHS; R01 HD045894, R01 HD042608, and R01 HD042115, NICHD, U.S. PHS; P20 DA017592, NIDA, U.S. PHS; and P30 MH046690, NIMH and ORMH. The authors thank Kristen Greenley, Katherine Pears, and Sally Guyer for overseeing data collection and data management activities; Matthew Rabel for editorial assistance; and the staff, families, and community partners of the Early Intervention Foster Care Project.

References

- Arbuckle JL. Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In: Marcoulides GA, Schumaker RE, editors. Advanced structural equation modeling: Issues and techniques. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1996. pp. 243–278. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Amos user's guide (version 3.6) Chicago, IL: SmallWaters; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Asher SR, Wheeler VA. Children's loneliness: A comparison of rejected and neglected peer status. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:500–505. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.4.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett D, Manly JT, Cicchetti D. Continuing toward an operational definition of psychological maltreatment. Development and Psychopathology. 1991;3:19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Becker WC, Madsen CH, Arnold CR, Thomas DR. The contingent uses of teacher attention and praise in reducing classroom behavior problems. Journal of Special Education. 1967;1:287–307. [Google Scholar]

- Becker-Blease KA, Freyd JJ. Beyond PTSD: An evolving relationship between trauma theory and family violence research. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2005;20:403–411. doi: 10.1177/0886260504269485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger KE, Patterson CJ, Kupersmidt JB. Peer relationships and self-esteem among children who have been maltreated. Child Development. 1998;69:1171–1197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brendgen M, Vitaro F, Bukowski WM, Doyle AB, Markiewicz D. Developmental profiles of peer social preference over the course of elementary school: Associations with trajectories of externalizing and internalizing behavior. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:308–320. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.37.3.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Moreland S, Reid K. Enhanced services and stipends for foster parents: Effects on retention rates and outcomes for children. Child Welfare. 1992;71:387–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Reid JB. Parent observation and report of child symptoms. Behavioral Assessment. 1987;9:97–109. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Reid JB. Using a specialized foster care community treatment model for children and adolescents leaving the state mental hospital. Journal of Community Psychology. 1991;19:266–276. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Lynch M. Failures in the expectable environment and their impact on individual development: The case of child maltreatment. Developmental Psychopathology. 1995;2:32–71. [Google Scholar]

- Clausen JM, Landsverk J, Ganger W, Chadwick D, Litrownik A. Mental health problems of children in foster care. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 1998;7:283–296. [Google Scholar]

- Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. Teacher—Social Competence Scale. University Park: Pennsylvania State University; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Damon W. Companionship and affection: The development of friendship. In: Damon W, editor. The social world of the child. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1977. pp. 137–166. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ. The family ecology of boys' peer relations in middle childhood. Child Development. 1990;61:874–892. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Eddy JM, Haas E, Li F, Spracklen K. Friendships and violent behavior during adolescence. Social Development. 1997;6:207–223. [Google Scholar]

- Erwin PG. Similarity of attitudes and constructs in children’s friendships. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 1985;40:470–485. [Google Scholar]

- Fagot BI, Hagan R. Observations of parent reactions to sex-stereotyped behaviors: Age and sex effects. Child Development. 1991;62:617–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantuzzo JW, Weiss AD, Atkins M, Meyers R, Noone M. A contextually relevant assessment of the impact of child maltreatment on the social competencies of low-income urban children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37:1201–1208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PA, Burraston B, Pears K. The Early Intervention Foster Care Program: Permanent placement outcomes from a randomized trial. Child Maltreatment. 2005;10:61–71. doi: 10.1177/1077559504271561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, Toobert DJ. A cost-effective parent training program for use with normal preschool children. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1979;4:129–145. [Google Scholar]

- Freyd J. Betrayal trauma: Traumatic amnesia as an adaptive response to childhood abuse. Ethics and Behavior. 1994;4:307–329. [Google Scholar]

- Gersten EL. A Health Resource Inventory: The development of a measure of the personal and social competence of primary-grade children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1976;44:775–786. [Google Scholar]

- Hanish LD, Martin CL, Fabes RA, Leonard S, Herzog M. Exposure to externalizing peers in early childhood: Homophily and peer contagion processes. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:267–281. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-3564-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington EM, Clingempeel WG. Coping with marital transitions: A family systems perspective. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1992;57 (2–3, Serial No. 227) [Google Scholar]

- Jacklin CN, Maccoby EE. Social behavior at 33 months in same-sex and mixed-sex dyads. Child Development. 1978;49:557–569. [Google Scholar]

- Keiley MK, Howe TR, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. The timing of child physical maltreatment: A cross-domain growth analysis of impact on adolescent externalizing and internalizing problems. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:891–912. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Wilcox LE. Self-control in children: Development of a rating scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1979;47:1020–1029. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.47.6.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Cicchetti D. A longitudinal study of child maltreatment, mother–child relationship quality and maladjustment: The role of self-esteem and social competence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32:341–354. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000030289.17006.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klee L, Kronstadt D, Zlotnick C. Foster care's youngest: A preliminary report. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1997;67:290–299. doi: 10.1037/h0080232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraft LW, Vraa CW. Sex composition of groups and pattern of self-disclosure by high school females. Psychological Reports. 1975;37:733–734. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1975.37.3.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusche CA, Greenberg MT, Beilke R. Seattle Personality Questionnaire for Young School-Aged Children. 1988 Unpublished questionnaire. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd G. Having friends, keeping friends, making friends, and being liked by peers in the classroom: Predictors of children’s early school adjustment? Child Development. 1990;61:1081–1100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landsverk J, Garland AF. Foster care and pathways to mental health services. In: Curtis P, Dale JG, editors. The foster care crisis: Translating research into practice and policy. Lincoln: The University of Nebraska Press; 1999. pp. 193–210. [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE, Crozier J, Kaplow J. A 12-year prospective study of the long-term effects of early child physical maltreatment on psychological, behavioral, and academic problems in adolescence. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2002;156:824–830. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.8.824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Malone PS, Stevens KI, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Developmental trajectories of externalizing and internalizing behaviors: Factors underlying resilience in physically abused children. Development and Psychopathology. 2006;18:35–55. doi: 10.1017/S0954579406060032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence CR, Carlson EA, Egeland B. The impact of foster care on development. Development and Psychopathology. 2006;18:57–76. doi: 10.1017/S0954579406060044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leve LD, Chamberlain P. Association with delinquent peers: Intervention effects for youth in the juvenile justice system. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:339–347. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-3571-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M, Cicchetti D. An ecological-transactional analysis of children and contexts: The longitudinal interplay among child maltreatment, community violence, and children's symptomatology. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:235–257. doi: 10.1017/s095457949800159x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE. Gender and relationships: A developmental account. American Psychologist. 1990;45:513–520. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.4.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly JT, Kim JE, Rogosch FA, Cicchetti D. Dimensions of child maltreatment and children's adjustment: Contributions of developmental timing and subtype. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:759–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith W. Measurement invariance, factor analysis and factorial invariance. Psychometrika. 1993;58:525–543. [Google Scholar]

- Parker JG, Herrera C. Interpersonal processes in friendship: A comparison of abused and nonabused children's experiences. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:1025–1038. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. Interventions for boys with conduct problems: Multiple settings, treatments, and criteria. In: Franks CM, Wilson GT, editors. Annual review of behavior therapy: Theory and practice. New York: Brunner/Maze; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Pears KP, Fisher PA. Developmental, cognitive, and neuropsychological functioning in preschool-aged foster children: Associations with prior maltreatment and placement history. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2005a;26:112–122. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200504000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pears KP, Fisher PA. Emotion understanding and theory of mind among maltreated children in foster care: Evidence of deficits. Development and Psychopathology. 2005b;17:47–65. doi: 10.1017/s0954579405050030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson C, Biggs M. “I was really, really, really mad!” Children’s use of evaluative devices in narratives about emotional events. Sex Roles. 2001;45:801–825. [Google Scholar]

- Pilowsky D. Psychopathology among children placed in family foster care. Psychiatric Services. 1995;46:906–910. doi: 10.1176/ps.46.9.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogosch FA, Cicchetti D. Illustrating the interface of family and peer relations through the study of child maltreatment. Social Development. 1994;3:292–308. [Google Scholar]

- Salzinger S, Feldman RS, Hammer M, Rosario M. The effects of physical abuse on children's social relationships. Child Development. 1993;64:169–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder J, Brooker M, Patrick MR, Snyder A, Schrepferman L, Stoolmiller M. Observed peer victimization during early elementary school: Continuity, growth, and relation to risk for child antisocial and depressive behavior. Child Development. 2003;74:1881–1898. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-8624.2003.00644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder J, Prichard J, Schrepferman L, Patrick MR, Stoolmiller M. Child impulsiveness-inattention, early peer experiences, and the development of early onset conduct problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32:579–594. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000047208.23845.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder J, Schrepferman L, Oeser J, Patterson G, Stoolmiller M, Johnson K, et al. Deviancy training and association with deviant peers in young children: Occurrence and contribution to early-onset conduct problems. Development and Psychopathology. 2005;17:397–413. doi: 10.1017/s0954579405050194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stouthamer-Loeber M, Loeber R, Homish DL, Wei E. Maltreatment of boys and the development of disruptive and delinquent behavior. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:941–955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. The AFCARS Report #2: Current estimates as of January 2000. 2000 Retrieved April 24, 2006, from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/stats_research/afcars/tar/report2/ar0100.htm.

- Walker HM, McConnell SR. Walker-McConnell Scale of Social Competence and School Adjustment: Elementary Version. San Diego, CA: Singular Publishing Group; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Walker JL, Carey PD, Mohr N, Stein DJ, Seedat S. Gender differences in the prevalence of childhood sexual abuse and in the development of pediatric PTSD. Archives of Women's Mental Health. 2004;7:111–121. doi: 10.1007/s00737-003-0039-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wodarski JS, Kurtz PD, Gaudin JM, Howing PT. Maltreatment and the school-age child: Major academic, socioemotional, and adaptive outcomes. Social Work. 1990;35:506–513. doi: 10.1093/sw/35.6.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wothke W. Longitudinal and multigroup modeling with missing data. In: Little TD, Schnabel KU, Baumert J, editors. Longitudinal and multilevel data: Practical issues, applied approaches, and specific examples. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2000. pp. 269–281. [Google Scholar]