Abstract

Purpose

To assess unresolved parental grief, the associated long-term impact on mental and physical health, and health service use.

Patients and Methods

This anonymous, mail-in questionnaire study was performed as a population-based investigation in Sweden between August 2001 and October 2001. Four hundred forty-nine parents who lost a child as a result of cancer 4 to 9 years earlier completed the survey (response rate, 80%). One hundred ninety-one (43%) of the bereaved parents were fathers, and 251 (56%) were mothers. Bereaved parents were asked whether or not, and to what extent, they had worked through their grief. They were also asked about their physical and psychological well-being. For outcomes of interest, we report relative risk (RR) with 95% CIs as well as unadjusted odds ratios and adjusted odds ratios.

Results

Parents with unresolved grief reported significantly worsening psychological health (fathers: RR, 3.6; 95% CI, 2.0 to 6.4; mothers: RR, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.9 to 4.4) and physical health (fathers: RR, 2.8; 95% CI, 1.8 to 4.4; mothers: RR, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.6 to 3.3) compared with those who had worked through their grief. Fathers with unresolved grief also displayed a significantly higher risk of sleep difficulties (RR, 6.7; 95% CI, 2.5 to 17.8). Mothers, however, reported increased visits with physicians during the previous 5 years (RR, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.1 to 2.6) as well as a greater likelihood of taking sick leave when they had not worked through their grief (RR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.2 to 3.5).

Conclusion

Parents who have not worked through their grief are at increased risk of long-term mental and physical morbidity, increased health service use, and increased sick leave.

INTRODUCTION

The loss of a loved one has been described as one of the most difficult experiences an individual can encounter.1,2 Even though the grieving process is painful and requires substantial readjustments, most individuals experience a normal course of grieving and are able to come to terms with their loss with time.3 Recently, Maciejewski et al4 found that widowed individuals generally go through identified stages of grief, but the vast majority of individuals who survive widowhood from natural causes are able to come to terms with the loss within approximately 1 year. However, some evidence suggests that the grief associated with the loss of a child may be more intense and may last longer than any other types of grief.5,6 To date, the long-term consequences of grief after the death of one's child as a result of cancer have not been explored.

Bereavement in general has been associated with an increased risk of unfavorable psychological, physical, and social outcomes7-13 and even with increased mortality.14-16 Unresolved, complicated, or prolonged grief appears particularly detrimental and has been linked with even higher risks of psychological, physical, and social problems.17,18

The present report examines the consequences of unresolved grief in a national sample of Swedish parents at 4 to 9 years after the loss of their children to cancer. We compared bereaved parents who reported not having worked through their grief with those who had, and we focused on self-assessed mental and physical well-being as well as aspects of health care utilization.

METHODS

Sample

By using Sweden's National Register of Causes of Death and the National Register of Cancer, we identified all the children in Sweden who died before age 25 years between 1992 and 1997 and who had been diagnosed with a malignancy before age 17 years. We then identified the parents of these 368 children through the Swedish Population Register. Study eligibility required parents to be the guardian of the child at the time of his or her diagnosis. Parents had to be born in one of the Nordic countries, and they had to be able to speak Swedish and have a listed phone number. Before any parent was approached, the child's former physicians verified the child's diagnosis and gave their consent to contact the family. Five hundred sixty-one bereaved parents were identified and were eligible.

Survey Development and Administration

Survey items were developed on the basis of in-depth interviews with seven bereaved parents; face-to-face validity was assessed later with 15 parents to ensure correct understanding of all items. In addition, a pilot study with 45 parents was conducted before the nationwide investigation. The final version of the questionnaire comprised 365 items.

Between August 2001 and October 2001, we sent an introductory letter to all 561 bereaved parents. The letter explained the purpose of the study and invited the parents to participate. Ten days after the introductory letter was sent, we telephoned the parents to ask them if they would like to participate in the study. Parents who agreed to participate separately received a questionnaire and a response form to indicate that they sent in the questionnaire, as the questionnaire was sent in anonymously. Ten days after the questionnaire was sent out, a card was mailed to all of the parents as a thank you and a reminder. For those parents who did not return the questionnaire, an interviewer performed a follow-up call another 10 days later. Of the 561 bereaved parents who were eligible for the study, 449 (80%) completed the survey.

Measures

Our study centered on parental grief. We sought to assess parental resolution of grief with one simple question: “Do you think that you have worked through your grief?” To respond to this question, parents were asked to select between the following answers: not at all, somewhat, a lot, or completely. Parents who stated not at all or somewhat were placed in the category of those parents who had not worked through their grief, whereas parents who responded a lot or completely were regarded as having worked through their grief. Before the study, this item was tested in face-to-face interviews to assure that the item was understood by the parents as intended by the researchers. Researchers were convinced from the parents’ comments that all parents interpreted the item as an assessment of whether they had come to terms or resolved their grief.

Eight parents did not answer the question about having worked through grief. They were not included in any analyses that involved parents having worked through grief. However, whenever analyses were performed that did not include parents having worked through grief, they were included if they responded to those specific questions.

Self-assessed anxiety and depression were measured with the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-T)19 and the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D).20 In addition, the Tibblin Score21 was used to assess quality of life. Quality of life according to physical and psychological well-being was self-assessed by the parents with a seven-point Visual Digital Scale.21a Health service use was assessed by asking parents whether they had taken any medication for psychological distress or had visited a physician for psychological distress during the last 5 years. Worsening physical and health was assessed by the following questions: “Do you think that your physical health has deteriorated during the last 5 years?” and “Do you think that your mental health has deteriorated during the last 5 years?” Sick leave was measured by asking if the parent had been on sick leave for psychological distress during the last 5 years and, if so, for how many months. All other outcomes were assessed by single-item questions. Parents also were asked about marital status, age, sex, number of children, education, employment status, and region of residence.

Analysis

Analyses were conducted with the SAS statistical package (version 9; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). For outcomes of interest, we reported descriptive statistics, such as frequencies and percentages, and we calculated the relative risk (RR) ratios with 95% CIs (by using the Mantel-Haenszel formula for the variance).

To assess whether measures of anxiety and/or depression were associated with unresolved parental grief, we calculated RR ratios with 95% CIs and crude and adjusted odds ratios (ORs). We additionally adjusted for time since the loss for fathers, because it was a significant confounder.

To assess whether having worked through grief was associated with outcomes of interest independent of anxiety and/or depression, we used multivariable logistic models with forward selection (entry criteria of P < .05) to calculate adjusted ORs. To account for a shift in effect measure, we also report crude ORs.

The Regional Ethics Committee of the Karolinska Institute approved the study.

RESULTS

Participants

One hundred ninety-one (43%) of bereaved parents were fathers, and 251 (56%) were mothers; seven did not state their sex. The sociodemographic characteristics of the bereaved parents are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Parents Who Lost a Child to Cancer 4 to 9 Years Earlier

| Characteristic | Bereaved Parents

|

|

|---|---|---|

| No. | % | |

| Identified as eligible in registries | 561 | |

| Reasons for no response | ||

| Refused to participate | 30 | 5 |

| Agreed but did not participate | 59 | 11 |

| Not reachable | 23 | 4 |

| Total nonresponders | 112 | 20 |

| Participating parents | 449 | 80 |

| Biological parent | 438 | 98 |

| Nonbiological parent | 9 | 2 |

| Not stated | 2 | < 1 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 191 | 43 |

| Female | 251 | 56 |

| Not stated | 7 | 2 |

| Age, years | ||

| < 30 | 66 | 15 |

| 30-39 | 232 | 52 |

| ≥ 40 | 146 | 32 |

| Not stated | 5 | 1 |

| Marital status today | ||

| Married or living with the child's other parent | 329 | 73 |

| Married or living with another partner | 51 | 11 |

| Has a partner but lives alone | 17 | 4 |

| Single | 45 | 10 |

| Not stated | 7 | 2 |

| No. of children at child's diagnosis | ||

| 1 | 82 | 18 |

| 2 | 192 | 43 |

| 3 | 116 | 26 |

| ≥ 4 | 54 | 12 |

| Not stated | 5 | 1 |

| Level of education | ||

| Elementary school | 83 | 18 |

| Secondary school | 215 | 48 |

| University | 141 | 31 |

| Not stated | 10 | 2 |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed | 370 | 82 |

| Unemployed | 10 | 2 |

| On sick leave/retired | 36 | 8 |

| Housewife/husband | 5 | 1 |

| Home with children | 8 | 2 |

| Student | 14 | 3 |

| Not stated | 6 | 1 |

| Residential region | ||

| Rural | 99 | 22 |

| Village/town | 273 | 61 |

| Large city (> 500,000 inhabitants) | 68 | 15 |

| Not stated | 9 | 2 |

Resolution of Grief

One hundred sixteen (26%) of 449 bereaved parents reported that they had not worked through their grief at 4 to 9 nine years after the death of their children; 12 (3%) stated that they had not worked through their grief at all; 104 (23%) said that they had worked through their grief somewhat; and eight (2%) did not answer the question.

Mothers were no more likely than fathers to have worked through their grief (P < .60) The number of parents with unresolved grief did not decrease with time (P < .13).

Psychological Well-Being Associated With Unresolved Grief

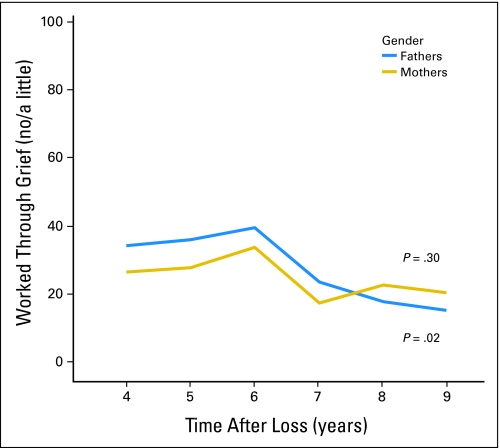

Parents who had not worked through their grief were more likely to report symptoms of anxiety, depression, and poor quality of life compared with parents who had worked through their grief (Table 2). The number of fathers with unresolved grief decreased significantly over the study period (P < 0.02). This was not seen among the mothers with unresolved grief (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Psychological Well-Being Associated With Unresolved Grief in Bereaved Parents

| Grief Response by Psychological Test* | Bereaved Parents

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fathers (n = 191)

|

Mothers (n = 251)

|

|||||||||

| No. Who Reported Given Response | Total No. of Responders | % | RR | 95% CI | No. Who Reported Given Response | Total No. of Responders | % | RR | 95% CI | |

| Tibblin score < 10%† | 4.4 | 1.7 to 11.5 | 2.7‡ | 1.2 to 6.1 | ||||||

| Not/little | 10 | 51 | 20 | 10 | 61 | 16 | ||||

| Moderate/much | 6 | 135 | 4 | 11 | 183 | 6 | ||||

| STAI-T > 90% | 4.9‡ | 2.2 to 10.8 | 3.6‡ | 2.0 to 6.5 | ||||||

| Not/little | 15 | 52 | 29 | 19 | 61 | 31 | ||||

| Moderate/much | 8 | 135 | 6 | 16 | 184 | 9 | ||||

| CES-D > 90% | 4.3‡ | 2.1 to 8.9 | 2.4‡ | 1.3 to 4.2 | ||||||

| Not/little | 16 | 50 | 32 | 17 | 62 | 27 | ||||

| Moderate/much | 10 | 135 | 7 | 21 | 181 | 12 | ||||

Abbreviations: RR, relative risk; STAI-T, Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale.

Response is to the question of whether the parent worked through grief.

Tibblin score is the score that measures quality of life.

Statistically significant results.

Fig 1.

Numbers of mothers and fathers who have not worked through their grief over the study period.

Outcomes Associated With Unresolved Grief in Fathers

Table 3 summarizes the outcomes associated with unresolved grief in fathers. In general, fathers who reported that they had not worked through their grief 4 to 9 years after the loss of the child were significantly more likely to suffer from poor physical and mental health compared with fathers who had worked through their grief. They were also more likely to report that their physical and mental health had deteriorated in the preceding 5 years. We found no significant differences in reported usage of tranquillizers, sleeping pills, or other medication for psychological distress between the groups. However, fathers with unresolved grief were more likely to report regular difficulties falling asleep and waking up with emotional distress more often than the other fathers.

Table 3.

Analyses of Outcomes Associated With Unresolved Grief in Fathers

| Grief Response by Outcome | Patients

|

Analyses*

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. Who Reported Given Response | Total No. of Responders | % | Unadjusted

|

Adjusted†

|

||||

| RR | 95% CI | OR | OR | 95% CI | ||||

| Low or moderate physical well-being | 1.5 | 1.1 to 1.9 | 2.5 | 1.6 | 0.7 to 3.5 | |||

| Little/no | 35 | 52 | 45 | |||||

| Moderate/much | 62 | 136 | ||||||

| Moderate or much worsened physical health in the last 5 years | 2.8‡ | 1.8 to 4.4 | 4.8 | 2.9‡ | 1.3 to 6.5 | |||

| Little/no | 27 | 52 | 52 | |||||

| Moderate/much | 25 | 136 | 18 | |||||

| Low or moderate psychological well-being | 2.4‡ | 1.8 to 3.1 | 7.4 | 3.0‡ | 1.2 to 7.9 | |||

| Little/no | 40 | 51 | 78 | |||||

| Moderate/much | 45 | 136 | 33 | |||||

| Moderate or much worsened psychological health in the last 5 years | 3.6‡ | 2.0 to 6.4 | 5.4 | 1.0 | 0.3 to 3.1 | |||

| Little/no | 21 | 52 | 40 | |||||

| Moderate/much | 15 | 134 | 11 | |||||

| Low or moderate quality of life | 2.1‡ | 1.6 to 2.7 | 5.7 | 2.2 | 0.8 to 5.7 | |||

| Little/no | 40 | 52 | 77 | |||||

| Moderate/much | 49 | 133 | 37 | |||||

| Visited physician because of anxiety or depression in the last 5 years | 1.8 | 0.8 to 4.1 | 2.0 | 2.2 | 0.9 to 5.8 | |||

| Little/no | 9 | 51 | 18 | |||||

| Moderate/much | 13 | 136 | 10 | |||||

| Visited physician because of other psychological distress in the last 5 years | 2.0 | 0.5 to 8.6 | 2.1 | 0.8 | 0.1 to 5.5 | |||

| Little/no | 3 | 51 | 6 | |||||

| Moderate/much | 4 | 136 | 3 | |||||

| On sick leave for psychological distress in the last 5 years | 2.1 | 0.9 to 5.0 | 2.3 | 0.7 | 0.2 to 2.5 | |||

| Little/no | 8 | 52 | 15 | |||||

| Moderate/much | 10 | 135 | 7 | |||||

| Received medication for psychological distress in the last 5 years | 1.5 | 0.5 to 4.2 | 1.5 | 0.3 | 0.1 to 1.6 | |||

| Little/no | 5 | 51 | 10 | |||||

| Moderate/much | 9 | 135 | 7 | |||||

| Regular use of tranquillizers | 1.3 | 0.1 to 13.5 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 0.0 to 5.7 | |||

| Little/no | 1 | 53 | 2 | |||||

| Moderate/much | 2 | 133 | 2 | |||||

| Regular use of sleeping pills | 2.6 | 0.4 to 18.1 | 2.6 | 0.8 | 0.1 to 8.7 | |||

| Little/no | 2 | 52 | 4 | |||||

| Moderate/much | 2 | 136 | 1 | |||||

| Regular difficulties falling asleep at night | 2.6‡ | 1.3 to 5.1 | 3.2 | 1.5 | 0.6 to 4.1 | |||

| Little/no | 14 | 52 | 27 | |||||

| Moderate/much | 14 | 136 | 10 | |||||

| Regular waking at night with emotional distress | 6.7‡ | 2.5 to 17.8 | 8.5 | 2.7 | 0.8 to 9.8 | |||

| Little/no | 13 | 53 | 25 | |||||

| Moderate/much | 5 | 136 | 4 | |||||

Abbreviations: RR, relative risk; OR, odds ratio.

Analyses of parents’ response to question of working through grief compared not/little v moderate/much answers for each outcome.

Adjusted for anxiety (with the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory), depression (with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; except for the outcome of physician visit because of anxiety or depression in the last 5 years), and time since loss.

Statistically significant results.

When analysis was adjusted for anxiety, depression, and time since loss, fathers with unresolved grief continued to have a higher likelihood of reporting greater physical and mental health problems compared with the other bereaved fathers (Table 3).

Mothers

Similar to fathers, mothers with unresolved grief 4 to 9 years after the loss of their child exhibited a significantly higher risk of poor and worsening physical as well as mental health compared with mothers who had worked through their grief (Table 4). In addition, the number of physician visits for anxiety and depression and the likelihood of taking sick leave were significantly higher among mothers who had not worked through their grief compared with the other bereaved mothers. We found no significant differences between the two groups with regard to sleep difficulties, reported use of tranquillizers, sleeping pills, or other medication for psychologicaldistress. When analysis was adjusted for anxiety and depression, bereaved mothers with unresolved grief continued to have a higher likelihood of reported worsening physical health (Table 4).

Table 4.

Outcomes Associated With Unresolved Grief in Mothers

| Grief Response by Outcome | Patients

|

Analyses*

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. Who Reported Given Response | Total No. of Responders | % | Unadjusted

|

Adjusted†

|

||||

| RR | 95% CI | OR | OR | 95% CI | ||||

| Low or moderate physical well-being | 1.5 | 1.2 to 1.7 | 3.8 | 1.5 | 0.6 to 3.5 | |||

| Little/no | 52 | 62 | 84 | |||||

| Moderate/much | 105 | 182 | 58 | |||||

| Moderate or much worsened physical health in the last 5 years | 2.3 | 1.6 to 3.3 | 3.7 | 2.2 | 1.1 to 4.5 | |||

| Little/no | 32 | 62 | 52 | |||||

| Moderate/much | 41 | 185 | 22 | |||||

| Low or moderate psychological well-being | 1.7 | 1.4 to 2.0 | 6.3 | 1.8 | 0.7 to 4.9 | |||

| Little/no | 54 | 62 | 87 | |||||

| Moderate/much | 94 | 182 | 52 | |||||

| Moderate or much worsened psychological health in the last 5 years | 2.9 | 1.9 to 4.4 | 4.7 | 2.0 | 0.9 to 4.3 | |||

| Little/no | 30 | 62 | 48 | |||||

| Moderate/much | 31 | 185 | 17 | |||||

| Low or moderate quality of life | 1.9 | 1.6 to 2.3 | 7.1 | 2.1 | 0.8 to 5.7 | |||

| Little/no | 53 | 62 | 85 | |||||

| Moderate/much | 84 | 185 | 45 | |||||

| Visited physician because of anxiety or depression in the last 5 years | 1.7 | 1.1 to 2.6 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 1.1 to 3.9 | |||

| Little/no | 22 | 61 | 36 | |||||

| Moderate/much | 39 | 183 | 21 | |||||

| Visited physician because of other psychological distress in the last 5 years | 0.8 | 0.2 to 2.8 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 0.1 to 1.4 | |||

| Little/no | 3 | 61 | 5 | |||||

| Moderate/much | 11 | 183 | 6 | |||||

| On sick leave for psychological distress in the last 5 years | 2.1 | 1.2 to 3.5 | 2.5 | 1.2 | 0.5 to 2.6 | |||

| Little/no | 18 | 62 | 29 | |||||

| Moderate/much | 25 | 178 | 14 | |||||

| Received medication for psychological distress in the last 5 years | 1.7 | 0.9 to 2.9 | 1.9 | 0.8 | 0.4 to 1.9 | |||

| Little/no | 15 | 61 | 25 | |||||

| Moderate/much | 27 | 182 | 15 | |||||

| Regular use of tranquillizers | 4.5 | 0.8 to 26.0 | 4.6 | 1.6 | 0.2 to 12.5 | |||

| Little/no | 3 | 62 | 5 | |||||

| Moderate/much | 2 | 184 | 1 | |||||

| Regular use of sleeping pills | 1.0 | 0.2 to 4.7 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 0.1 to 5.4 | |||

| Little/no | 2 | 62 | 3 | |||||

| Moderate/much | 6 | 183 | 3 | |||||

| Regular difficulties falling asleep at night | 1.4 | 0.8 to 2.6 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 0.2 to 1.6 | |||

| Little/no | 12 | 62 | 19 | |||||

| Moderate/much | 25 | 183 | 14 | |||||

| Regular waking at night with emotional distress | 1.7 | 0.7 to 3.8 | 1.8 | 0.5 | 0.1 to 1.6 | |||

| Little/no | 8 | 62 | 13 | |||||

| Moderate/much | 14 | 183 | 8 | |||||

Abbreviations: RR, relative risk; OR, odds ratio.

Adjusted for anxiety (with the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory) and depression (with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; except for the outcome of physician visit because of anxiety or depression in the last 5 years).

Statistically significant result.

DISCUSSION

Study results show that, even 4 to 9 years after the loss of a child as a result of cancer, a significant proportion of bereaved parents (26%) had not worked through their grief. Both mothers and fathers with unresolved grief are more likely to report higher levels of anxiety and depression as well as decreased quality of life compared with other bereaved parents. These comorbidities appear related to other forms of dysfunction; parents who were unable to work through their grief displayed significantly worse outcomes in various other areas of their lives. Specifically, mothers with unresolved grief were more frequently on sick leave and were more likely to have required physician visits during the last 5 years. Fathers who had not worked through their grief were more likely to experience difficulties sleeping and instances of waking up with emotional distress. Some of these outcomes, such as worsening physical health for mothers and fathers and decreased psychological health for fathers, appear attributable to unresolved grief beyond anxiety and depression.

A number of studies have reported on how the loss of a spouse affects men and women differently.7,8,22,23 A review of the literature on bereaved spouses suggests that men generally display greater risks of developing health problems as a consequence of bereavement than do women.23 Even though our findings confirm this to a certain extent, we do not believe a direct comparison can be made between different types of losses. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to highlight long-term consequences of parents who lose their child as a result of cancer, and it provides new information on the ways in which unresolved grief in bereaved parents affects fathers differently from the way it affects mothers.

In our sample, the greatest difficulties for fathers appeared to be sleep disturbances. It has been reported elsewhere that sleep disturbances are common in bereaved individuals.10,24-27 Most studies, however, have examined individuals closer to their initial period of bereavement. We find it striking that sleep disturbance can persist in bereaved fathers who have not worked through their grief even 4 to 9 years after the loss; it is particularly striking when one considers that sleep deprivation can further increase the risk of various adverse health outcomes.28 One might also wonder how sleep deprivation in fathers affects their work performance and productivity during the day. Interestingly, Germain et al29point out that sleep disturbances are not part of either of the two most commonly used criteria for complicated grief.17,30 Our study points to disturbed sleep as one of the strongest outcomes of unresolved grief, particularly for fathers. Notably, we found no evidence that parents with unresolved grief use more tranquillizers, sleeping pills, or any other medication for psychological distress than parents who have worked through their grief. Nor were these fathers more likely to have visited a physician, which suggests that their sleep difficulties are under-diagnosed and under-treated.

Different from fathers, mothers with unresolved grief appear to be at higher risk for increased health resource utilization and sick leave. Stroebe et al23 note in their review about sex differences in bereaved spouses that, although men show more relative excess of symptomatology than women, there are significant differences in the ways the two sexes cope: women are more likely to express their emotionality, vent their distress, confide in others, and use formal resources; men remain silent and keep feelings of distress and anxiety to themselves. Although no similar studies have been conducted for bereaved parents, these findings may help explain the sex differences found in the present investigation.

In this sample, no difference was found in how many parents had resolved their grief in respect to how long it had been since their child had passed away. This may be an indication that unresolved grief is quite persistent with time. However, because of the cross-sectional design of the study, no clear conclusions can be drawn in this regard. Nevertheless, Prigerson et al,4,10,25 in their longitudinal studies of bereavement, found that elevated levels of grief persist through the examined 2 years post-loss. Because these symptoms of grief appear unlikely to resolve on their own and because they significantly affect individuals’ mental and physical health,10,12,25,31 effective interventions ought to be developed. In the past, few interventions have proven effective at improving the situation of bereaved individuals.32,33 However, new interventions that specifically target individuals who had developed symptoms of complicated grief were recently tested in randomized, controlled trials. These interventions demonstrated some success at reducing a number of the symptoms associated with complicated grief.34,35 Furthermore, as shown elsewhere,3,36 support from the health care professionals directly involved in the child's care before and following the loss may have an impact on parents’ bereavement adjustment and thereby may have the potential to reduce the adverse effects associated with unresolved grief.

The findings of this study have significant implications for clinical practice: assessment of parents’ long-term resolution of grief in a simple, one-sentence question can give the provider important feedback on the parents well-being and functioning in long-term follow-up. The utilization of a simple way to ask parents is suitable for the time constraints of clinical, daily practice. Also, the question is a way to assess resolution of grief that can easily be understood by parents.

Even though this study was comprehensive in its recruitment and response rate, it still has a number of limitations. One is its cross-sectional design, which may limit the conclusions made about causality. For example, it is possible that fathers with a history of sleep problems have more difficulties working though their grief, rather than the other way around. Also, concerns may be raised about the independence of the information for mothers and fathers, because some of the individuals were parents of the same child. However, this issue should be resolved by looking at the two sexes separately, which was done in this study. Furthermore, because of the anonymous nature of the study, it was not possible to obtain objective information about health and functioning, such as medical chart extraction about health service use or clinical assessment. Instead, we had to rely solely on parents’ self-reports. In addition, the use of a single-item question to assess unresolved grief can be considered a substantial limitation. However, interviews were performed with parents to test the face-to-face validation of the item, and all parents appeared to understand the question as intended and responded to it in terms of whether they had come to terms with or had resolved their grief. Notably, the use of simple, single-item questions can even be a powerful way for the clinical practice to find out how parents are doing after the loss of their child and to detect significant complications from parent bereavement. Finally, this study was done in the cultural setting of Sweden, which has a relatively homogeneous population. The results may not be generalizable to other populations.

In conclusion, our study has shown that parents who have not worked through their grief are at increased risk of long-term psychological symptoms as well as impaired physical health, sleep disturbance, and increased health service use. Effective interventions to support this group of bereaved parents are warranted.

AUTHORS’ DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Patrizia K. Lannen, Joanne Wolfe, Holly G. Prigerson, Erik Onelöv, Ulrika C. Kreicbergs

Financial support: Ulrika C. Kreicbergs

Administrative support: Ulrika C. Kreicbergs

Provision of study materials or patients: Ulrika C. Kreicbergs

Collection and assembly of data: Ulrika C. Kreicbergs

Data analysis and interpretation: Patrizia K. Lannen, Joanne Wolfe, Holly G. Prigerson, Erik Onelöv, Ulrika C. Kreicbergs

Manuscript writing: Patrizia K. Lannen, Joanne Wolfe, Erik Onelöv, Ulrika C. Kreicbergs

Final approval of manuscript: Patrizia K. Lannen, Joanne Wolfe, Holly G. Prigerson, Erik Onelöv, Ulrika C. Kreicbergs

Acknowledgments

We thank the parents who made this study possible by bravely sharing their experiences with us.

published online ahead of print at www.jco.org on November 24, 2008

Supported by grants from the Swedish Children's Cancer Foundation, grants from the Swedish Society for Medical Research, Grant No. KLS-01645-02-2005 from the Swiss Cancer League, Grant No. CA096746 from the National Cancer Institute, and a Child Health Research Grant No. NCI 5 K07 CA096746 from the Charles H. Hood Foundation.

Authors’ disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Holmes TH, Rahe RH: The Social Readjustment Rating Scale. J Psychosom Res 11:213-218, 1967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Osterwers M, Solomon F, Green M: Bereavement Reactions, Consequences, and Care: Committee for the Study of Health Consequences of the Stress of Bereavement. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 1984 [PubMed]

- 3.Kreicbergs UC, Lannen P, Onelov E, et al: Parental grief after losing a child to cancer: Impact of professional and social support on long-term outcomes. J Clin Oncol 25:3307-3312, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maciejewski PK, Zhang B, Block SD, et al: An empirical examination of the stage theory of grief. JAMA 297:716-723, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rando TA: Parental Loss of a Child. Champaign, IL, Research Press Co, 1986

- 6.Rees W: Death and Bereavement: The Psychological, Religious, and Cultural Interfaces. London, Whurr Publisher Ltd, 1997

- 7.Bierhals AJ, Prigerson HG, Frank E, et al: Gender differences in complicated grief among the elderly. Omega (Westport) 32:303-317, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen JH, Bierhals AJ, Prigerson HG, et al: Gender differences in the effects of bereavement-related psychological distress in health outcomes. Psychol Med 29:367-380, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ott CH: The impact of complicated grief on mental and physical health at various points in the bereavement process. Death Stud 27:249-272, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prigerson HG, Bierhals AJ, Kasl SV, et al: Traumatic grief as a risk factor for mental and physical morbidity. Am J Psychiatry 154:616-623, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prigerson HG, Bridge J, Maciejewski PK, et al: Influence of traumatic grief on suicidal ideation among young adults. Am J Psychiatry 156:1994-1995, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prigerson HG, Frank E, Kasl SV, et al: Complicated grief and bereavement-related depression as distinct disorders: Preliminary empirical validation in elderly bereaved spouses. Am J Psychiatry 152:22-30, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silverman GK, Jacobs SC, Kasl SV, et al: Quality of life impairments associated with diagnostic criteria for traumatic grief. Psychol Med 30:857-862, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li J, Olsen J: Physical Health Outcomes of Psychological Stress by Parental Bereavement: National Perspective in Oxington KV (ed): Denmark, Psychology of Stress. Hauppage, NY, Nova Biomedical Books, 2005, pp 53–82

- 15.Li J, Precht DH, Mortensen PB, et al: Mortality in parents after death of a child in Denmark: A nationwide follow-up study. Lancet 361:363-367, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schaefer C, Quesenberry CP Jr, Wi S: Mortality following conjugal bereavement and the effects of a shared environment. Am J Epidemiol 141:1142-1152, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prigerson HG, Vanderwerker LC, Maciejewski PK: Prolonged grief disorder: A case for inclusion in DSM-V, in Stroebe M, Hansson R, Schut H, et al (eds): Handbook of Bereavement Research and Practice: 21st Century Perspectives. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association Press, 2008, pp 165–186

- 18.Zhang B, El-Jawahri A, Prigerson HG: Update on bereavement research: Evidence-based guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of complicated bereavement. J Palliat Med 9:1188-1203, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spielberger C, Gorusch R, Lushene P, et al: Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Form Y). Palo Alto, CA, Consulting Psychologists Press, 1983

- 20.Radloff L: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas 1:385-401, 1977 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tibblin G, Tibblin B, Peciva S, et al: The Goteborg quality of life instrument: An assessment of well-being and symptoms among men born 1913 and 1923—Methods and validity. Scand J Prim Health Care Suppl 1:33-38, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21a.Onelov E, Steineck G, Nyberg UK, et al: Measuring anxiety and depression in the oncology setting using visual-digital scales. Acta Oncologica 46:810-816, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maciejewski PK, Prigerson HG, Mazure CM: Sex differences in event-related risk for major depression. Psychol Med 31:593-604, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stroebe M: Gender differences in adjustment to bereavement: An empirical and theoretical review. Rev Gen Psychol 5:62-83, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hardison HG, Neimeyer RA, Lichstein KL: Insomnia and complicated grief symptoms in bereaved college students. Behav Sleep Med 3:99-111, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Latham AE, Prigerson HG: Suicidality and bereavement: Complicated grief as psychiatric disorder presenting greatest risk for suicidality. Suicide Life Threat Behav 34:350-362, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mack JW, Cook EF, Wolfe J, et al: Understanding of prognosis among parents of children with cancer: Parental optimism and the parent-physician interaction. J Clin Oncol 25:1357-1362, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McDermott OD, Prigerson HG, Reynolds CF 3rd, et al: Sleep in the wake of complicated grief symptoms: An exploratory study. Biol Psychiatry 41:710-716, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neubauer DN: Sleep, health, and medicine. Primary Psychiatry 13:44-45, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Germain A, Shear K, Monk TH, et al: Treating complicated grief: Effects on sleep quality. Behav Sleep Med 4:152-163, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horowitz MJ, Siegel B, Holen A, et al: Diagnostic criteria for complicated grief disorder. Am J Psychiatry 154:904-910, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK, Reynolds CF 3rd, et al: Inventory of Complicated Grief: A scale to measure maladaptive symptoms of loss. Psychiatry Res 59:65-79, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jordan JR, Neimeyer RA: Does grief counseling work? Death Stud 27:765-786, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stroebe W, Schut H, Stroebe MS: Grief work, disclosure and counseling: Do they help the bereaved? Clin Psychol Rev 25:395-414, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boelen PA, de Keijser J, van den Hout MA, et al: Treatment of complicated grief: A comparison between cognitive-behavioral therapy and supportive counseling. J Consult Clin Psychol 75:277-284, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shear K, Frank E, Houck PR, et al: Treatment of complicated grief: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 293:2601-2608, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.deCinque N, Monterosso L, Dadd G, et al: Bereavement support for families following the death of a child from cancer: Experience of bereaved parents. J Psychosoc Oncol 24:65-83, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reference deleted

- 38.Reference deleted

- 39.Reference deleted

- 40.Reference deleted

- 41.Reference deleted

- 42.Reference deleted

- 43.Reference deleted

- 44.Reference deleted