Abstract

Improving access to healthcare has been a consistent priority for Canadians. In particular, reducing patient waiting times for health services has been a prominent policy issue. Across the country, governments are using a range of strategies to reduce patient waiting times for care, with a particular focus on reducing waits for specialized services. Although information is emerging on waits for selected procedures, there is limited information on whether the utilization of services or waiting experiences of Canadians with health problems are different from those of the general population. Data from the Health Services Access Survey (2001–2005) were used to compare waiting experiences for specialized services between adults with health problems and healthier adults. The specialized services included specialist visits for a new illness or condition, non-emergency surgery and diagnostic tests. National-level estimates revealed that adults with health problems were more likely to self-report that they required specialized services. However, the median waiting times for these services were comparable to those of healthier adults.

Abstract

L'amélioration de l'accès aux services de santé est une priorité constante pour les Canadiens. Plus spécialement, la réduction des temps d'attente pour les services est une question dominante en matière de politiques. Partout au pays, les gouvernements mettent en place des stratégies pour réduire les temps d'attente, en particulier pour les services spécialisés. Bien que l'information sur les temps d'attente pour certaines interventions soit de plus en plus disponible, il existe peu d'information, au Canada, sur les différences d'utilisation des services ou des temps d'attente entre les personnes ayant un problème de santé et la population en général. Les données provenant de l'Enquête sur l'accès aux services de santé (2001–2005) ont été employées pour comparer les temps d'attente pour les services spécialisés entre les adultes ayant un problème de santé et les personnes en meilleure santé. Les services en question comprenaient les consultations auprès des spécialistes pour une nouvelle maladie ou un nouvel état de santé, les chirurgies non urgentes et les tests de diagnostic. Les estimations à l'échelle nationale révèlent que les adultes ayant un problème de santé sont plus susceptibles de déclarer volontairement qu'ils ont eu besoin de recourir à des services spécialisés. Cependant, la médiane des temps d'attente pour ces services était comparable à celle qu'on observe pour les adultes en meilleure santé.

Improving access to healthcare has been a consistent priority for Canadians. In particular, reducing patient waiting times for health services has been a prominent policy issue. In 2004, Canada's First Ministers listed timely access to high-quality care at the top of their collective agenda, committing to achieve “meaningful reductions in wait times in priority areas such as cancer, heart, diagnostic imaging, joint replacements and sight restoration” (Ontario Canadian Intergovernmental Conference Secretariat 2005). Across the country, governments are using a range of strategies to improve access to care and reduce patient waiting times.

However, limited information exists on the waiting experiences of Canadians with health problems, such as those with chronic care needs, who are often hospitalized and are heavy users of the healthcare system. Data from two Commonwealth Fund surveys raised questions about whether Canadians with health problems tended to have different waits for a doctor's appointment than their healthier counterparts. In 2005, 36% of Canadian adults with health problems reported waiting six days or longer for a doctor's appointment, while in 2004, 26% (regardless of health status) reported waiting that long (Shoen et al. 2004, 2005; Commonwealth Fund 2004). Although the questions and survey approach were similar, the surveys were conducted in two different time frames and had relatively small sample sizes (1,410 Canadians were part of the sample in 2004, and 751 in 2005). Other Canadian data, such as wait times reported for cardiac surgery in Ontario, suggest that sicker patients have shorter waits for surgery (Cardiac Care Network of Ontario 2008). This study analyzes data from a population-based Canadian survey, with a larger sample size than that of the Commonwealth Fund, to determine whether Canadians with health problems have longer or shorter waits for specialized services. A better understanding of the profile of patients who wait longer for care may allow policy makers to design more targeted wait time reduction initiatives.

In 2001, Statistics Canada first released results from the Health Services Access Survey (HSAS), designed to capture information on patients' experiences accessing healthcare, including their experiences related to waiting for specialized services (Sanmartin et al. 2002). Using 2001–2005 results from the survey, this study assesses whether waiting experiences and waiting times for specialized services – including specialist visits for a new illness or condition, non-emergency surgery and diagnostic tests (MRI, CT or angiography) – differ between adults with health problems and healthier adults.

Methods

Data

The HSAS is a population-based, cross-sectional survey with data available for 2001, 2003 and 2005 (Sanmartin et al. 2002, 2004; Statistics Canada 2006). The survey was incorporated into the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) in 2005 (Statistics Canada 2006). Respondents to the HSAS are a subsample of the CCHS, which covers Canadians who are 15 years of age or older and living in private dwellings in the 10 provinces. The data collected in the HSAS are obtained through a complex sample design involving stratification, clustering and multistage sampling. Detailed information on the sampling strategy has been discussed elsewhere (Sanmartin et al. 2002, 2004; Statistics Canada 2006). The survey includes self-reported information on service needs, difficulties accessing services and wait times for services. Key definitions appear in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Key definitions of specialized services

| Specialized service | Definition | Wait time measured |

|---|---|---|

| Specialist visit | Visit with a medical specialist to obtain a diagnosis for a new illness or condition; does not include specialist visits for ongoing care for a previously diagnosed condition | Time elapsed between point at which individuals and their doctor decided that they should see a specialist and the day of the visit |

| Non-emergency surgery | Booked or planned surgery provided on an outpatient or inpatient basis; does not refer to surgery provided through an admission to the hospital emergency room as a result of, e.g., an accident or life-threatening situation | Time elapsed between point at which individuals and their surgeon decided to go ahead with the surgery and the day of surgery |

| Diagnostic test | MRI, CT scan or angiography requested by a physician to determine or confirm a diagnosis; does not include X-rays, blood tests, etc. | Time elapsed between point at which individuals and their doctor decided to go ahead with the test and the day of the test |

Statistics Canada, Health Statistics Division. 2006. Access to Health Care Services in Canada: January to December 2005. Ottawa: Minister of Industry.

Study population

The study included respondents who were 18 years of age or older. Using available information from the HSAS, “adults with health problems” were defined using criteria similar to those used by the Commonwealth Fund survey (Shoen et al. 2004, 2005). Table 2 describes the definition applied in this study and its comparison with that used by the Commonwealth Fund. For this study, “healthier adults” were defined as those who did not meet any of the criteria established by the study definition. In 2005 the total sample of healthier adults was 24,121, while the sample for adults with health problems was 9,978.

TABLE 2.

Definition of adults with health problems

| Study definition | Commonwealth Fund definition>† | |

|---|---|---|

| Poor or fair self-rated health | Poor or fair self-rated health | |

| Had at least one chronic illness and contacted a healthcare provider* 10 times or more in the past 12 months | Had a serious or chronic illness, injury or disability requiring intensive medical care in the past two years | |

| Was an overnight hospital patient for four or more days in the past 12 months** | Had major surgery or was hospitalized for something other than a normal pregnancy in the past two years |

“Healthcare provider” includes family physician/general practitioner, eye specialist, dentist/orthodontist, chiropractor and/or other medical doctor. The 10 visits could be distributed among any of the providers listed.

The criterion for a heavy user of medical care (four or more overnight hospital days) was based on similar definitions used by investigators in the following study: Statistics Canada 1999. “Health Care Services – Recent Trends.” Health Reports 11(3): 91–112; catalogue no. 82-003-XPB.

Analysis

Weighted distributions and frequencies were used to describe baseline characteristics of the study population and assess wait times for specialist visits for a new illness or condition, non-emergency surgery and selected diagnostic tests. Data from the HSAS were weighted to account for the sampling and non-response in the survey and to reflect the demographics of the Canadian population. Wait times were compiled only for those who received a specialized health service within the preceding 12 months. Records with item non-responses were excluded from all calculations. To account properly for the complex survey design, variance estimates and 95% confidence intervals for all estimates were calculated using bootstrap survey weights. Median waiting times were age- and sex-adjusted using a direct method of standardization based on the July 1, 2001 Canadian population (excluding the territories). Statistical analyses were computed using SAS statistical software (version 9.1 SAS Institute Inc.).

Results

Baseline characteristics

In 2005, adults with health problems represented 26.6% of the study population, or approximately 6.5 million Canadians 18 years of age or older. This percentage is greater than the proportion in 2003, but similar to that reported in 2001. Compared to healthier adults, there was a greater proportion of females among adults with health problems. In 2005, 58.1% of adults with health problems and 48.3% of healthier adults were female. Furthermore, there was a greater proportion of older adults among those with health problems. The same year, those aged 65 years or older represented 25.2% of adults with health problems and 12.8% of healthier adults.

Access to specialized services

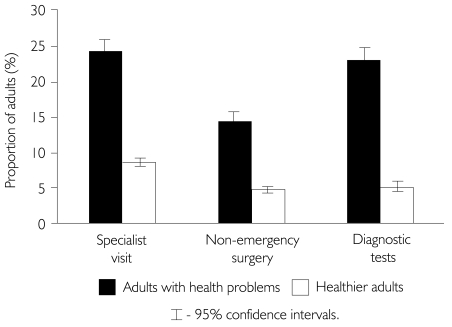

Adults with health problems were more likely to report that they required specialized health services than their healthier counterparts. In 2005, 23.1% of adults with health problems required a specialist visit for a new illness or condition, compared with 8.1% of healthier adults (Figure 1). Adults with health problems were also more likely to require diagnostic tests (21.7% versus 5.0%) and non-emergency surgery (13.8% versus 4.4%). Similar results were found in 2001 and 2003 (data not shown).

FIGURE 1.

Proportion of adults requiring specialized services, Canada, 2005

Although adults with health problems were more likely to require specialized services, the proportion of those accessing these services was similar to that of their healthier counterparts. For those both with and without health problems, nine out of 10 who said they required specialized care went on to access the service.

Some adults who received specialized health services reported difficulties in obtaining access due to a variety of reasons, including problems getting an appointment or waiting too long for an appointment. Both adults with health problems and their healthier counterparts were more likely to report difficulties in accessing a specialist visit than in accessing the other categories of specialized services. There was no significant difference between the two groups in the proportion reporting difficulties accessing specialized services.

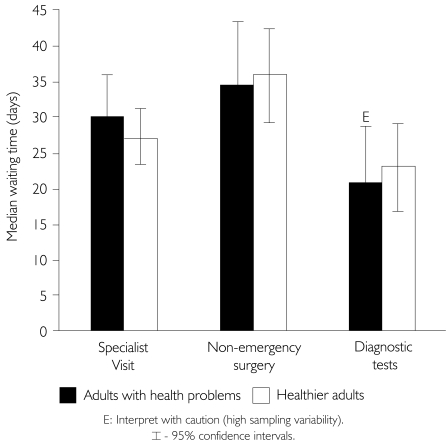

Median waiting times for specialized services

Despite the variation in the proportion of adults with health problems and healthier adults who required specialized services, the median waiting time for such care was similar between the two groups. In 2005, the age–sex standardized median waiting time for specialist visits and non-emergency surgery was approximately one month for both groups. Adjusted waiting times for diagnostic tests were shorter, with adults in both groups waiting approximately three weeks in 2005 (Figure 2). Between 2001 and 2005, the median waiting time for most specialized services remained fairly consistent for both adult groups.

FIGURE 2.

Age- and sex-standardized median waiting times for specialized services, Canada, 2005

Limitations

Owing to the cross-sectional design of the HSAS, it was not possible to establish a time relationship between health status and median wait times for specialized services. Specifically, the nature of the survey did not permit identification and tracking of a group of adults with health problems who subsequently required specialized care, establishing service use and determining waiting periods for the cohort over time. Results of the HSAS are based on self-reported information that have not been clinically validated and may be subject to recall bias (Sanmartin et al. 2002, 2004; Statistics Canada 2006). To reduce potential recall bias, survey questions repeatedly referred to services used in the past 12 months. Waiting time estimates were retrospective and included only those who completed their waiting periods and received care. Provincial-level wait time estimates were not reported for each group because sample sizes were not large enough to generate reliable estimates. The data do not reflect the waiting times of those still waiting at the time of the survey. The results are not generalizable to population groups not represented by the survey, including residents of the three territories, those living on Indian reserves or Crown lands, residents of institutions, full-time members of the Canadian Forces and residents of certain remote regions.

Conclusions

Although findings from the Commonwealth Fund surveys suggest that Canadian adults with health problems may be more likely to wait longer for some health services than healthier adults, findings from this study with a nationally representative sample indicate that this relationship may not hold for specialized services. Although Canadian adults with health problems may be more likely to require specialized health services, there were no substantial differences between the two groups regarding their access to care, such as their reported difficulties in obtaining access to specialized services. Furthermore, median waiting times for these services were similar in both adult groups and over time.

While we need to be cautious regarding the limitations of self-reported data, the large-sample HSAS data represent the most comprehensive information available on a pan-Canadian basis regarding access to a full range of non-emergency surgery, specialist visits and diagnostic tests. This study sheds light on the waiting experiences for specialized health services between adults with health problems and their healthier counterparts. Future research using longitudinal data is needed to clarify the relationship between health status and wait times for specialized services in Canada.

Contributor Information

Thi Ho, Analyst, Office of the Vice President, Canadian Institute for Health Information, Toronto, ON.

Kathleen Morris, Consultant, Canadian Institute for Health Information, Toronto, ON.

References

- Cardiac Care Network of Ontario. Cardiac Surgery Statistics. 2008 Jul 3; Retrieved July 4, 2008. <http://www.ccn.on.ca/index.cfm?fuseaction=ts&tm=17&ts=160&tsb=0>.

- Commonwealth Fund. International Health Perspectives: Results 2004. 2004 Retrieved July 4, 2008. < http://www.cmwf.org/usr_doc/IHP2004_topline_results.pdf>.

- Ontario Canadian Intergovernmental Conference Secretariat. A 10-Year Plan to Strengthen Health Care. 2005 Retrieved July 4, 2008. < http://www.scics.gc.ca/cinfo04/800042005_e.pdf>.

- Sanmartin C., Gendron F., Berthelot J.-M., Murphy K. Health Analysis and Measurement Group; Statistics Canada. Access to Health Care Services in Canada, 2003. Ottawa: Minister of Industry; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sanmartin C., Houle C., Berthelot J.-M., White K. Health Analysis and Measurement Group; Statistics Canada. Access to Health Care Services in Canada, 2001. Ottawa: Minister of Industry; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Shoen C., Osborn R., Huynh P.T., Doty M., Zapert K., Peugh J. Primary Care and Health System Performance: Adults' Experience in Five Countries. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2004 Jul–Dec;(Suppl. Web Exclusives):W4-487–503. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w4.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoen C., Osborn R., Huynh P.T., Doty M., Zapert K., Peugh J., Davis K. Taking the Pulse of Health Care Systems: Experiences of Patients with Health Problems in Six Countries. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2005;(Suppl. Web Exclusives):W5-509–525. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w5.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada, Health Statistics Division. Access to Health Care Services in Canada: January to December 2005. Ottawa: Minister of Industry; 2006. [Google Scholar]