Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a progressive disease with studies of disease progression generally focusing on measures of airflow and mortality. In nonsmokers, maximal lung function is attained around age 15 to 25 years, and after a variable plateau phase, subsequently declines at approximately 20 to 25 ml/year. Smoking may reduce the maximal FEV1 achieved, shorten or eliminate the plateau phase, and may accelerate the rate of decline in lung function in a dose-dependent manner. Some smokers are predisposed to more rapid declines in lung function than others, and recent reports suggest that females may be at higher risk of lung damage related to smoke exposure than males. Progressive deterioration in dyspnea, functional status, and health-related quality of life (HRQL) in patients with COPD is well known, but the magnitude and rate of decline and its association with severity of airflow obstruction remains poorly defined. Many studies have identified pulmonary function, in particular the FEV1, as the single best predictor of survival. An impaired diffusing capacity and overall impairment in functional status have also been associated with impaired survival in COPD. The National Emphysema Treatment Trial has provided additional insight into these features in a large, well-characterized group of patients with severe airflow obstruction and structural emphysema.

Keywords: emphysema, natural history, survival, pulmonary function, quality of life

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) has been variously defined by the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society (1) and the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) (2). These definitions emphasize that airflow limitation hallmarks COPD, which is characterized as partially reversible, usually progressive, associated with abnormal lung inflammation in response to noxious particles or gases, and most importantly, preventable and treatable. Current COPD guidelines define airflow limitation as being present when the ratio between forced expiratory flow in one second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC) is less than 70% (1, 2). This definition is easy to remember, although there is concern that the use of a “fixed” ratio may lead to under- and over-estimation in younger and older populations, respectively (3, 4). Although earlier definitions included segregation of patients into different phenotypes, including chronic bronchitis and emphysema (5), more recent guidelines have moved away from this artificial separation, favoring the more descriptive term, COPD (1, 2). In this article we have tried to focus on the emphysematous phenotype when data are available.

PREVALENCE

Higgins and Thom reported (6) that the prevalence of emphysema ranges from 4 to 6% of adult white males and 1 to 3% of white females, whereas Bang reports a prevalence of COPD of 3.7% in African American males and 6.7% in African American females (7). A recent meta-analysis by Halbert and colleagues suggests that the prevalence of COPD is higher among males than females, among smokers and former smokers than nonsmokers, and among those over 40 years old than those under 40 (8). However, the prevalence of COPD can vary significantly for a given population, depending upon which definition is used (3, 9).

PROGRESSION OF EMPHYSEMA: NATURAL HISTORY AND RISK FACTORS

As noted by international guidelines, COPD is a progressive disease (1, 2). Studies of disease progression have generally been limited to measures of airflow and mortality. Increasingly, worsening of symptoms or health status, as well as the appearance of co-morbidities, have been investigated.

Spirometric Progression

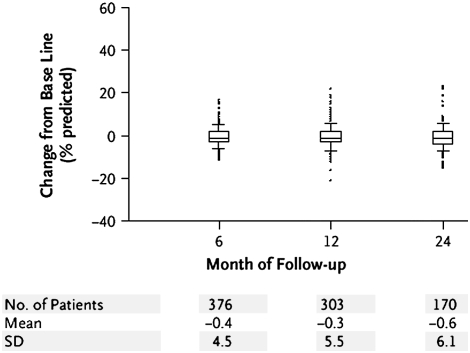

Numerous studies have focused on FEV1 decline over time. Once maximal lung function is attained around age 15 to 25 years (10–15), it remains relatively constant for approximately a decade (the “plateau phase”). In nonsmokers, lung function subsequently declines by approximately 20 to 25 ml/year (16), and roughly 1 liter is lost over the next five decades. Reports differ on whether this decline is linear, and it has been suggested that the decline may accelerate with age (13, 15, 17, 18). Smoking impacts the natural history of pulmonary function in numerous ways. Several lines of evidence suggest that smoking may reduce the maximal FEV1 achieved, including passive smoking, which may begin in utero (19, 20) or early childhood (21–24), as well as smoking during adolescence (25–27). Smoking may shorten the plateau phase (11, 28–30) or, in some instances, completely eliminate it (28). Finally, smoking accelerates the rate of decline in lung function (10, 14–17, 28, 31), as extensively reviewed elsewhere (32). Fletcher and coworkers (16) demonstrated that smokers have a steeper decline in pulmonary function than nonsmokers. The results of the Lung Health Study confirmed in a large, longitudinal study that smoking was associated with an accelerated decline in lung function (33). Interestingly, some smokers are predisposed to more rapid declines in lung function (“rapid decliners”) than others (“slow decliners”) (34), with large inter-individual differences in the rates of FEV1 decline. Those with pre-existing airways obstruction have been suggested to be at the highest risk of “accelerated decline” (the so called “horse racing effect”) (16, 35). Further, it has been suggested that there is a “dose–response” relationship between the number of “pack-years” smoked and lung function decline (16, 36–38). It is also not clear whether the decline is linear in smokers or whether it occurs in a step-wise manner. Data on disease progression specific to emphysema are few, although the National Emphysema Treatment Trial (NETT) provides some insight with respect to deterioration in FEV1 (Figure 1) (48). A deterioration over 2 years is notable, with significant inter-individual variability.

Figure 1.

Change from baseline in FEV1% predicted in non–high-risk medically treated patients in the National Emphysema Treatment Trial (NETT) who completed the procedure after 6, 12, or 24 months of follow-up (Reprinted by permission from 48).

Whether consequences of smoke exposure are influenced by sex remains controversial (25, 36, 39–41), as recently reviewed (35). Recent reports suggest that females are at higher risk of lung damage related to smoke exposure than males (25, 42–44). The responsible physiological mechanisms are felt to be related to the structural development of lungs or hormonal homeostasis. Reports have suggested that females exposed to smoke during adolescence may be at an increased risk of having a lower maximal FEV1 (25), developing early onset COPD because of a more rapid decline in FEV1 (42, 43), and having a higher rate of bronchial hyperreactivity (44). Underlying genetic susceptibility has been touted as a possible reason to explain the fact that only 10 to 20% of smokers develop significant obstructive airways disease (45). However, other than α1-antitrypsin deficiency, there are no other convincing genetic associations (46). Since the prevalence of the relevant α1-antitrypsin variants is low, the proportion of emphysema attributable to this gene is approximately 1% (47).

Acute exacerbations of COPD are associated with significant reductions in pulmonary function, which may not completely resolve (49), and when recurrent, exacerbations have been associated with a more rapid decline in FEV1 (50–52). Whether these concepts apply to a predominantly emphysematous population is not clear. The medically managed patients in the NETT experienced quite a bit of health care utilization, including hospitalizations and emergency room visits (53).

Exercise Capacity

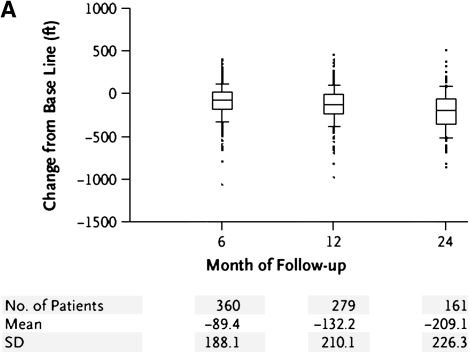

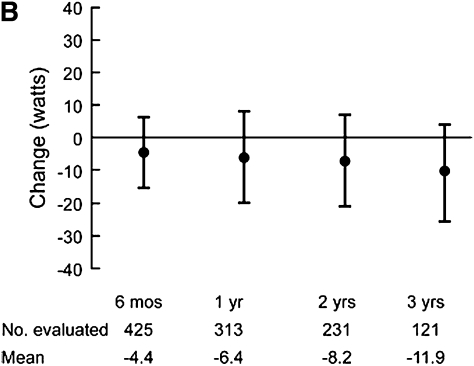

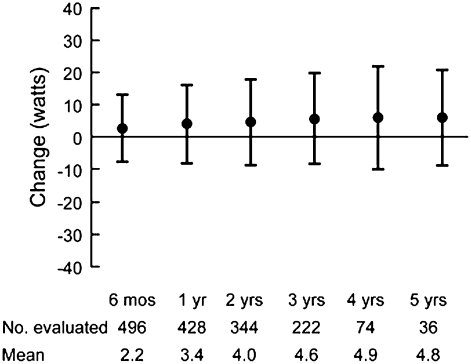

Progressive deterioration in the functional status of patients with COPD is well known. How this translates to decreased exercise capacity, however, is less well studied. Peak oxygen uptake was reported to decline at a slope similar to the loss in FEV1 in 137 males (mean age 69 years at initial testing) with moderately severe airflow obstruction (mean FEV1 45.9% predicted) (54) undergoing 5 years of sequential cardiopulmonary exercise testing (54). A different group examined long-term change in six-minute walk distance in a cohort of 294 patients with COPD (55). Over 5 years of follow-up the proportion of patients with a decline of greater than or equal to 54 m walked was higher in patients with worse airflow obstruction. The decline in FEV1 over time was higher in those with milder airflow obstruction at baseline when compared with those with more severe obstruction. In patients with predominantly emphysematous disease, loss of exertional capacity has also been reported. The NETT investigators performed six-minute walk and maximal exercise testing using well defined methodology (56). Figure 2 illustrates change in six-minute walk in non–high-risk medically treated patients during early follow-up (Figure 2A) (48); a general decrease is noted, although significant heterogeneity is evident. Similar results are seen for changes in maximal watts achieved during longer term follow-up in all medically treated patients (Figure 2C) (57). It is evident that the natural history of exercise capacity is to decrease, particularly in patients with worse airflow obstruction, but the magnitude and rate of decline remains poorly defined.

Figure 2.

(A) Change from baseline in maximal achieved six-minute walk test distance in non–high-risk medically managed patients in the NETT who completed the procedure after 6, 12, or 24 months of follow-up (48). (B) Longer-term change from baseline in maximal achieved watts during oxygen supplemented cardiopulmonary exercise testing in medically managed patients in the NETT (Reprinted by permission from 57).

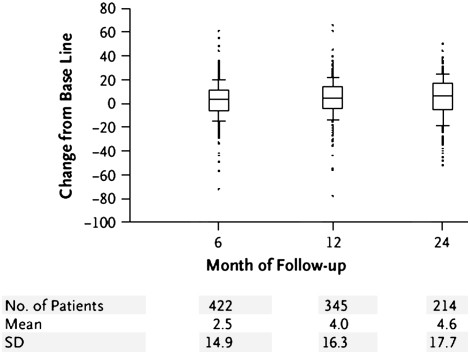

Symptoms

Shortness of breath is a cardinal and often presenting symptom of COPD, particularly in those with emphysema (58). Dyspnea is typically progressive, has a complex relationship with severity of airflow obstruction, but only weakly correlates with FEV1 (59). NETT investigators described that females exhibited greater breathlessness compared with males (60) as measured by the University of California, San Diego Shortness of Breath Questionnaire (UCSD SOBQ) (61). In medically managed NETT patients, breathlessness has been shown to increase over 2 years of follow-up (Figure 3) (48).

Figure 3.

Change from baseline in the University of California, San Diego Shortness of Breath Questionnaire (UCSD SOBQ) among non–high-risk, medically managed NETT patients (Reprinted by permission from 48). A minimal clinically important improvement is a decrease in UCSD SOBQ of 5 points or more.

Most patients with COPD develop cough and phlegm production at some point. Where that point lies along the COPD symptom continuum and whether it varies among different patients or populations in less clear. It is now better understood that the decline in FEV1 and degree of mucus hypersecretion do not always parallel one another (62, 63). It has been reported that approximately 20 to 25% of smokers with chronic productive cough may have normal a FEV1 and a similar proportion of smokers with low FEV1 may not present with chronic productive cough (16). Patients with mucus hypersecretion may be at risk of more frequent COPD exacerbations (64, 65), which may lead to a more rapid decline in FEV1 (30), and may be associated with more hospital admissions (66). In smokers without COPD, cough is associated with a greater impairment in quality of life (67) as well as greater mortality (68). Data assessing cough in COPD with more clearly defined clinical phenotypes are limited. Recently, one group has suggested that patients with emphysema with more bronchial wall abnormality on CT are more likely to complain of cough (69). The natural history of cough in patients with COPD remains unclear, although young adults with cough are more likely to be diagnosed with COPD over time (70).

Health Status

Increasing evidence suggests that health-related quality of life (HRQL) deteriorates with advancing COPD (71), although most studies have typically focused only on patients with advanced disease. Although data on patients with emphysema are more limited, it has been suggested that HRQL in patients with emphysema relates to the degree of airflow obstruction, the level of dyspnea, and capacity of effort and respiratory muscle pressures (72). NETT investigators examined HRQL and its predictors in randomized patients (73). In general HRQL was low and correlated weakly with the level of airflow obstruction, maximum work during exercise testing, and six-minute walk distance. Longitudinal data from the ISOLDE study demonstrated that patients with moderate and severe COPD had impairment in baseline HRQL that worsened during 3 years of follow-up (74). These investigators and others have suggested that recurrent exacerbations lead to worsened impairment (75). Longitudinal data on patients with well-defined emphysema are scanty. The NETT investigators have provided preliminary insight on this topic (Figures 4A and 4B) (48, 57). It is evident that a worsening of disease-specific HRQL was noted in patients with severe emphysema. Furthermore, the magnitude of rise is higher than the widely accepted minimally accepted clinical difference in the St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire. The determinants of worsened disease-specific HRQL in severe emphysema remain unclear.

Figure 4.

Change in St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire in all patients randomized to the medical arm of the NETT during 5 years of follow-up (Reprinted by permission from 57).

Emphysema Severity

It is evident that emphysema is a progressive disease, as attested to by worsening pulmonary function, exercise capacity, symptoms, and HRQL. A key question is the relationship of these parameters to structural markers of disease. The availability of imaging techniques has allowed assessment of progression in structural abnormalities. An early study in 22 patients with α1-antitrypsin deficiency related emphysema quantified lung density over 30 months (76). Lung density changes correlated with changes in health status but not FEV1 or DlCO. More recently, a prospective study of 87 patients with emphysema (24 current smokers) examined over a thirty month period with quantitative chest computed tomography (77) found that changes in FEV1 or DlCO did not correlate with changes in lung density over time, and the authors concluded that change in lung density was a more sensitive measure of emphysema progression than changes in pulmonary function parameters. More recently, the methodology to assess serial changes in lung density have been better defined (78). Future studies should provide a better sense of anatomical disease progression.

Mortality

Mortality, a key feature of disease progression, has been rising in COPD over the past three decades (79), during which time many authors have examined the natural history of COPD in an attempt to identify prognostic factors (80, 81). The vast majority of these studies have identified pulmonary function, in particular the FEV1, as the single best predictor of survival (80–82). In the Intermittent Positive Pressure Breathing Trial (IPPB), in which a wide spectrum of patients with COPD without hypoxemia were recruited, baseline prebronchodilator FEV1 and patient age were the best predictors of mortality (83, 84); survival was worst in patients with a postbronchodilator FEV1 less than 30% predicted. An impaired diffusing capacity has been suggestive of a decreased survival in some studies (80). Overall impairment in functional status has been associated with impaired survival in COPD, with numerous investigators reporting worse survival in patients with COPD with a lesser exercise capacity (80, 85).

Pulmonary hypertension is present in a significant proportion of patients with advanced COPD and, although severe pulmonary hypertension is unusual (86, 87), it appears to independently influence survival (88). Nutritional status also strongly influences COPD prognosis (81). Recently, investigators have incorporated the multitude of clinical abnormalities in COPD into multidimensional indices (89). The most compelling of these, published by Celli and colleagues, is the BODE index, which reflects the body mass index (B), the degree of airflow obstruction (O), dyspnea (D), and the exercise capacity measured by the six-minute walk test (89).

The impact of the diagnosis of emphysema on prognosis in COPD has received limited attention. Burrows and colleagues studied 117 subjects with chronic airflow limitation (FEV1 47.1–51.3% predicted) and characterized subjects as “asthmatic bronchitis” if they were atopic and had a minimal smoking history (< 10 pack-years), “typical COPD” if there was no asthma or atopy history along with a greater than 10 pack-year smoking history, and “mixed” if these features were not met (90). A significant difference in survival was noted favoring patients with asthmatic bronchitis. Mortality data specific to emphysema has been best characterized in the setting of α1-antitrypsin deficiency associated COPD. Three-year mortality has been reported to be less than 40% in those with an initial FEV1 less than 30% predicted, compared with 93% when the FEV1 was between 30 and 65% predicted in one early study (91). Separate analyses support that prognosis in emphysema associated with α1-antitrypsin deficiency worsens when the FEV1% predicted falls below 25 to 30% (92, 93).

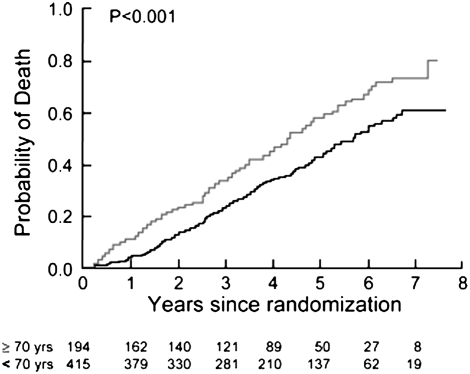

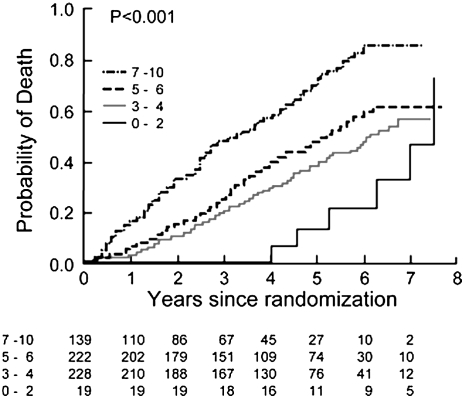

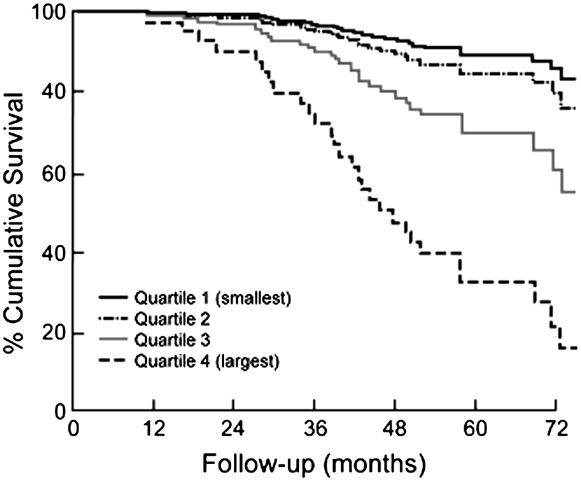

NETT investigators have recently published mortality models examining the survival characteristics of the medically treated patients (94). Table 1 enumerates the factors associated with survival in severe emphysema. These data support the notion that many of the factors prognostic in COPD are also prognostic in patients with emphysema. Age is a strong predictor (Figure 5), as are numerous physiological features. Importantly, the BODE index is strongly predictive in this population (Figure 6), even with the more severe baseline level of airflow obstruction noted in the NETT patients (95). The amount of emphysema and its distribution were also independent prognostic factors, as was the maximal exercise capacity. A subanalysis of mortality as a function of structural features in histologic samples from NETT patients confirms that airway mucous is a strong factor influencing long-term survival (Figure 7) (95).

TABLE 1.

SIGNIFICANT PREDICTORS IN MULTIVARIATE MORTALITY MODELS IN PATIENTS (n = 609) WITH SEVERE EMPHYSEMA (94)

| Model 1*

|

Model 2*

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | Hazard Ratio | (95% CI) | P Value | Hazard Ratio | (95% CI) | P Value |

| Age, yr | ||||||

| 70–83 | 1.64 | (1.23–2.18) | 0.001 | 1.72 | (1.31–2.26) | < 0.001 |

| 40–69 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||||

| High (> 28.1) | 0.86 | (0.62–1.21) | 0.40 | Not applicable | ||

| Medium | Reference | (BODE component) | ||||

| Low (< 21.4) | 1.32 | (0.98–1.78) | 0.06 | |||

| Oxygen use (rest, exercise, or sleeping) | ||||||

| Yes | 1.46 | (1.02–2.10) | 0.04 | 1.40 | (0.98–2.01) | 0.07 |

| No | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | ||||||

| 9.1–13.3 | 1.34 | (0.97–1.85) | 0.08 | 1.38 | (1.00–1.89) | 0.05 |

| 13.4–19.1 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| SOBQ score | ||||||

| 79–109 | 1.39 | (0.98–1.97) | 0.06 | Not applicable | ||

| 9–78 | Reference | (BODE component) | ||||

| Total lung capacity (% predicted) | ||||||

| 140–203 | 0.68 | (0.46–1.00) | 0.05 | 0.69 | (0.47–1.01) | 0.06 |

| 95–139 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Residual volume (% predicted) | ||||||

| 262–412 | 1.57 | (1.03–2.39) | 0.04 | 1.56 | (1.04–2.37) | 0.03 |

| 97–261 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| DlCO | ||||||

| 6–21 | 1.34 | (0.99–1.82) | 0.06 | 1.36 | (1.01–1.84) | 0.04 |

| 22–68 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Maximal CPET workload (W) | ||||||

| Low† | 1.54 | (1.17–2.03) | 0.002 | 1.48 | (1.12–1.94) | 0.006 |

| High† | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Difference in % emphysema (upper lung-lower lung) | ||||||

| −40.4 to −0.8 | 1.74 | (1.19–2.57) | 0.005 | 1.80 | (1.22–2.66) | 0.003 |

| −0.7 to 63.6 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Missing | 0.84 | (0.55–1.28) | 0.41 | 0.86 | (0.57–1.31) | 0.49 |

| Perfusion ratio | ||||||

| 0.04–0.14 | 1.57 | (1.13–2.17) | 0.007 | 1.53 | (1.11–2.12) | 0.01 |

| 0.15–3.13 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Modified BODE index‡ | ||||||

| 7–10 | Not applicable‡§ | 1.48 | (1.07–2.05) | 0.02 | ||

| 1–6 | Reference | |||||

Definition of abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; CI = confidence interval; CPET = cardiopulmonary exercise testing; DlCO = diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide; SOBQ = University of California, San Diego Shortness of Breath Questionnaire.

Results are shown for those variables that were significant predictors at the P ⩽ 0.05 level in either model. Model 2 was the same as Model 1 except that the modified BODE index replaced its components.

All variables include BMI; kg; m2; St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire; SOBQ; FEV1; ratio of inspiratory capacity to total lung capacity; DlCO; maximum inspiratory pressure; maximum expiratory pressure; PaO2; PaCO2; six-minute walk test; and CPET.

Low exercise is defined as a maximal workload at or below the sex-specific 40th percentile (25 W for females and 40 W for males; high exercise is defined as a workload above this threshold).

Components of the modified BODE index are: BMI, FEV1, UCSD SOBQ score, and 6MWT distance.

P = 0.012 for the four components for the modified BODE index.

Figure 5.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of the probability of death as a function of number of years after randomization for medically treated patients segregated by age. The P value was derived by the log rank test for the comparison between subgroups over a median follow-up period of 3.9 years (Reprinted by permission from Reference 94).

Figure 6.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of the probability of death as a function of number of years after randomization for medically treated patients segregated by modified BODE index. The P value was derived by the log rank test for the comparison between subgroups over a median follow-up period of 3.9 years (Reprinted by permission from Reference 94).

Figure 7.

Kaplan Meier survival plot of the 101 cases of severe (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease [GOLD] stage 3) and very severe (GOLD stage 4) chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, indicating that median survival was shortened in the quartile with the most severe occlusion of the fully expanded lumen (HR [hazard ratio], 3.28; 95% confidence interval, 1.55 to 6.92; P = 0.002) (Reprinted by permission from Reference 95).

CONCLUSIONS

COPD is a progressive disease with one of its pathophysiologic bases reflecting emphysematous destruction. Review of the data suggests that emphysema is a similarly progressive disorder associated with spirometric progression, symptomatic worsening, health status worsening, and impaired survival. The NETT has provided additional insight into these features in a large, well-characterized group of patients with severe airflow obstruction and structural emphysema.

The National Emphysema Treatment Trial (NETT) was supported by contracts with the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (N01HR76101, N01HR76102, N01HR76103, N01HR76104, N01HR76105, N01HR76106, N01HR76107, N01HR76108, N01HR76109, N01HR76110, N01HR76111, N01HR76112, N01HR76113, N01HR76114, N01HR76115, N01HR76116, N01HR76118, and N01HR76119), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS; formerly the Health Care Financing Administration); and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).

Conflict of Interest Statement: None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Celli BR, MacNee W. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J 2004;23:932–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. The GOLD global strategy for the management and prevention of COPD: Executive summary 2006. [Accessed 2007 Jul 21]. Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org.

- 3.Celli BR, Halbert RJ, Isonaka S, Schau B. Population impact of different definitions of airway obstruction. Eur Respir J 2003;22:268–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kohler D, Fischer J, Raschke F, Schonhofer B. Usefulness of GOLD classification of COPD severity. Thorax 2003;58:825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Thoracic Society. Standards for the diagnosis and care of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995;152:S77–S121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higgins MW, Thom T. Incidence, prevalence, and mortality: intra and inter-country differences. In: Hensley MJ, Saunders NA, editors. Clinical epidemiology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. New York: Marcel Dekker Inc.; 1989. pp. 23–42.

- 7.Bang KM. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in blacks. J Natl Med Assoc 1993;85:51–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halbert RJ, Natoli JL, Gano A, Badamgarav E, Buist AS, Mannino DM. Global burden of COPD: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 2006;28:523–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Viegi G, Pedreschi M, Pistelli F, Di Pede F, Baldacci S, Carrozzi L, Giuntini C. Prevalence of airways obstruction in a general population: European Respiratory Society vs. American Thoracic Society definition. Chest 2000;117:S339–S345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knudson RJ, Lebowitz MD, Holberg CJ, Burrows B. Changes in the normal maximal expiratory flow-volume curve with growth and aging. Am Rev Respir Dis 1983;127:725–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Pelt W, Borsboom GJJM, Rijcken B, Schouten JP, van Zomeren BC, Quanjer PH. Discrepancies between longitudinal and cross-sectional change in ventilatory function in 12 years of follow-up. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994;149:1218–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morris JF, Koski A, Johnson LC. Spirometric standards for healthy non-smoking adults. Am Rev Respir Dis 1971;103:57–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burrows B, Lebowitz MD, Camilli AE, Knudson RJ. Longitudinal changes in forced expiratory volume in one second in adults. Methodologic considerations and findings in healthy nonsmokers. Am Rev Respir Dis 1986;133:974–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crapo RO, Morris AH, Gardner RM. Reference spirometric values using techniques and equipment that meet ATS recommendations. Am Rev Respir Dis 1981;123:659–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brandli O, Schindler C, Kunzli N, Keller R, Perruchoud AP. Sapaldia team. Lung function in healthy never smoking adults: reference values and lower limits of normal of a Swiss population. Thorax 1996;51:277–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fletcher CM, Peto R, Tinker CM, Speizer FE. The natural history of chronic bronchitis and emphysema. An eight-year study of early chronic obstructive lung disease in working men in London. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976.

- 17.Glindmeyer HW, Lefante JJ, McColloster C, Jones RN, Weill H. Blue-collar normative spirometric values for Caucasian and African American men and women aged 18 to 65. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995;151:412–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ware JH, Dockery DW, Louis TA, Xu XP, Ferris BG Jr, Speizer FE. Longitudinal and cross-sectional estimates of pulmonary function decline in never-smoking adults. Am J Epidemiol 1990;132:685–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tager IB, Ngo L, Hanrahan JP. Maternal smoking during pregnancy: effects on lung function during the first 18 months of life. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995;152:977–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Young S, Le Souef PN, Geelhoed GC, Stick SM, Turner KJ, Landau LI. The influence of a family history of asthma and paternal smoking on airway responsiveness in early infancy. N Engl J Med 1991;324:1168–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang X, Wypij D, Gold DR, Speizer FE, Ware JH, Ferris BG Jr, Dockery DW. A longitudinal study of the effects of parental smoking on pulmonary function in children 6–18 years. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994;149:1420–1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tager IB, Weiss ST, Munoz A, Rosner B, Speizer FE. Longitudinal study of the effects of maternal smoking on pulmonary function in children. N Engl J Med 1983;309:699–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cook DG, Strachan DP, Carey IM. Health effects of passive smoking. 9. Parental smoking and spirometric indices in children. Thorax 1998;53:884–893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cook DG, Strachan DP. Summary of effects of parental smoking on the respiratory health of children and implications for research. Thorax 1999;54:357–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gold DR, Wang X, Wypij D, Speizer FE, Ware JH, Dockery DW. Effects of cigarette smoking on lung function in adolescent boys and girls. N Engl J Med 1996;335:931–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lebowitz MD, Holberg CJ, Knudson RJ, Burrows B. Longitudinal study of pulmonary function development in childhood, adolescence, and early adulthood: development of pulmonary function. Am Rev Respir Dis 1987;136:69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tager IB, Munoz A, Rosner B, Weiss S, Carey V. Effect of cigarette smoking on the pulmonary function of children and adolescents. Am Rev Respir Dis 1985;131:752–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tager IB, Segal MR, Speizer FE, Weiss ST. The natural history of forced expiratory volumes: effect of cigarette smoking and respiratory symptoms. Am Rev Respir Dis 1988;138:837–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Samet JM, Lange P. Longitudinal studies of active and passive smoking. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996;154:S257–S265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sherrill DL, Lebowitz MD, Knudson RJ, Burrows B. Smoking and symptom effects on the curves of lung function growth and decline. Am Rev Respir Dis 1991;144:17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dockery DW, Ware JH, Ferris BG Jr, Glicksberg DS, Fay ME, Spiro A 3rd, Speizer FE. Distribution of forced expiratory volume in one second and forced vital capacity in healthy, white, adult never-smokers in six US cities. Am Rev Respir Dis 1985;131:511–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kerstjens HAM, Rijcken B, Schouten JP, Postma DS. Decline of FEV1 by age and smoking status: facts, figures, and fallacies. Thorax 1997;52:820–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anthonisen NR, Connett JE, Kiley JP, Altose MD, Bailey WC, Buist AS, Conway WA Jr, Enright PL, Kanner RE, O'Hara P, et al. Effects of smoking intervention and the use of an inhaled anticholinergic bronchodilator on the rate of decline of FEV1: the Lung Health Study. JAMA 1994;272:1497–1505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gottlieb DJ, Stone PJ, Sparrow D, Gale ME, Weiss ST, Snider GL, O'Connor GT. Urinary desmosine excretion in smokers with and without rapid decline of lung function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996;154:1290–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Han MK, Postma D, Mannino D, Giardino ND, Buist S, Curtis JL, Martinez FJ. Gender and COPD: why it matters. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:1179–1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu S, Weiss ST, Rijcken B, Schouten JP. Smoking, changes in smoking habits, and rate of decline in FEV1: new insight into gender differences. Eur Respir J 1994;7:1056–1106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burchfiel CM, Marcus EB, Curb JD, MacLean CJ, Vollmer WM, Johnson LR, Fong KO, Rodriguez BL, Masaki KH, Buist AS. Effects of smoking and smoking cessation on longitudinal decline in pulmonary function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995;151:1778–1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lange P, Groth S, Nyboe J, Mortensen J, Appleyard M, Jensen G, Schnohr P. Effects of smoking and changes in smoking habits on the decline of FEV1. Eur Respir J 1989;2:811–816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lange P, Groth S, Nyboe J, Mortensen J, Appleyard M, Jensen G, Schnohr P. Decline of the lung function related to the type of tobacco smoked and inhalation. Thorax 1990;45:22–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Camilli AE, Burrows B, Knudson RJ, Lyle SK, Lebowitz MD. Longitudinal changes in forced expiratory volume in one second in adults. (Effects of smoking and smoking cessation). Am Rev Respir Dis 1987;135:794–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu X, Li B, Wang L. Gender differences in smoking effects on adult pulmonary function. Eur Respir J 1994;7:477–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Silverman E. Gender-related differences in severe, early-onset COPD. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;162:2152–2158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prescott E, Bjerg AM, Andersen PK, Lange P, Vestbo J. Gender difference in smoking effects on lung function and risk for hospitalization for COPD: results from a Danish longitudinal population study. Eur Respir J 1997;10:822–827. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paoletti P, Carrozzi L, Viegi G, Modena P, Ballerin L, Di Pede F, Grado L, Baldacci S, Pedreschi M, Vellutini M, et al. Distribution of bronchial responsiveness in a general population: effect of sex, age, smoking, and level of pulmonary function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995;151:1770–1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith CA, Harrison DJ. Association between polymorphism in gene for microsomal epoxide hydrolase and susceptibility to emphysema. Lancet 1997;350:630–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Silverman EK, Palmer LJ, Mosley JD, Barth M, Senter JM, Brown A, Drazen JM, Kwiatkowski DJ, Chapman HA, Campbell EJ, et al. Genome wide linkage analysis of quantitative spirometric phenotypes in severe early-onset chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Hum Genet 2002;70:1229–1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Anto JM, Vermeire P, Vestbo J, Sunyer J. Epidemiology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J 2001;17:982–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fishman A, Martinez F, Naunheim K, Piantadosi S, Wise R, Ries A, Weinmann G, Wood DE, for the National Emphysema Treatment Trial Research Group. A randomized trial comparing lung-volume-reduction surgery with medical therapy for severe emphysema. N Engl J Med 2003;348:2059–2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Seemungal TA, Donaldson GC, Bhowmik A, Jeffries DJ, Wedzicha JA. Time course and recovery of exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;161:1608–1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Makris D, Moschandreas J, Damianaki A, Ntaoukakis E, Siafakas NM, Milic Emili J, Tzanakis N. Exacerbations and lung function decline in COPD: new insights in current and ex-smokers. Respir Med 2007;101:1305–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kanner RE, Anthonisen NR, Connett JE; Lung Health Study Research Group. Lower respiratory illnesses promote FEV(1) decline in current smokers but not ex-smokers with mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results from the Lung Health Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;164:358–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Donaldson GC, Seemungal TA, Bhowmik A, Wedzicha JA. Relationship between exacerbation frequency and lung function decline in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 2002;57:847–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ramsey SD, Berry K, Etzioni R, Kaplan RM, Sullivan SD, Wood DE; National Emphysema Treatment Trial Research Group. Cost effectiveness of lung volume reduction surgery for patients with severe emphysema. N Engl J Med 2003;348:2092–2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oga T, Nishimura K, Tsukino M, Sato S, Hajiro T, Mishima M. Exercise capacity deterioration in patients with COPD: longitudinal evaluation over 5 years. Chest 2005;128:62–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Casanova C, Cote CG, Marin JM, de Torres JP, Aguirre-Jaime A, Mendez R, Dordelly L, Celli BR. The 6-minute walk distance: long-term follow-up in patients with COPD. Eur Respir J 2007;29:535–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sciurba F, Criner GJ, Lee SM, Mohsenifar Z, Shade D, Slivka W, Wise RA; National Emphysema Treatment Trial Research Group. Six-minute walk distance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: reproducibility and effect of walking course layout and length. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;167:1522–1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Naunheim KS, Wood DE, Mosenifar Z, Sternberg AL, Criner GJ, DeCamp MM, Deschamps CC, Martinez FJ, Sciurba FC, Tonascia J, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients receiving lung-volume-reduction surgery versus medical therapy for severe emphysema by the National Emphysema Treatment Trial Research Group. Ann Thorac Surg 2006;82:431–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Barr RG, Celli BR, Martinez FJ, Ries AL, Rennard SI, Reilly JJ Jr, Sciurba FC, Thomashow BM, Wise RA. Physician and patient perceptions in COPD: the COPD resource network needs assessment survey. Am J Med 2005;118:1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wolkove N, Dajczman E, Colacone A, Kreisman H. The relationship between pulmonary function and dyspnea in obstructive lung disease. Chest 1989;96:1247–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Martinez FJ, Curtis JL, Sciurba F, Mumford J, Giardino ND, Weinmann G, Kazerooni E, Murray S, Criner GJ, Sin DD, et al.; National Emphysema Treatment Trial Research Group. Sex differences in severe pulmonary emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:243–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Eakin EG, Resnikoff PM, Prewitt LM, Ries AL, Kaplan RM. Validation of a new dyspnea measure: the UCSD Shortness of Breath Questionnaire. Chest 1998;113:619–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Clement J, van de Woestjne KP. Rapidly decreasing forced expiratory volume in one second or vital capacity and development of chronic airway obstruction. Am Rev Respir Dis 1982;125:553–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Higgins MW, Keller JB, Becker M, Howatt W, Landis JR, Rotman H, Weg JG, Higgins I. An index of risk for obstructive airways disease. Am Rev Respir Dis 1982;125:144–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Seemungal TA, Donaldson GC, Paul EA, Bestall JC, Jeffries DJ, Wedzicha JA. Effects of exacerbation on quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;157:1418–1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Foreman MG, Demeo DL, Hersh CP, Reilly JJ, Silverman EK. Clinical determinants of exacerbations in severe, early-onset COPD. Eur Respir J 2007;22. (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 66.Vestbo J, Prescott E, Lange P. Association of chronic mucus hypersecretion with FEV1 decline and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease morbidity. Copenhagen City Heart Study Group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996;153:1530–1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Heijdra YF, Pinto-Plata VM, Kenney LA, Rassulo J, Celli BR. Cough and phlegm are important predictors of health status in smokers without COPD. Chest 2002;121:1427–1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ekberg-Aronsson M, Pehrsson K, Nilsson JA, Nilsson PM, Lofdahl CJ. Mortality in GOLD stages of COPD and its dependence on symptoms of chronic bronchitis. Respir Res 2005;6:98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fujimoto K, Kitaguchi Y, Kubo K, Honda T. Clinical analysis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease phenotypes classified using high-resolution computed tomography. Respirology 2006;11:731–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.de Marco R, Accordini S, Cerveri I, Corsico A, Anto JM, Kunzli N, Janson C, Sunyer J, Jarvis D, Chinn S, et al. Incidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a cohort of young adults according to the presence of chronic cough and phlegm. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;175:32–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jones P, Quirk FH, Baveystock CM, Littlejohns P. A self-complete measure of health status for chronic airflow limitation: The St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire. Am Rev Respir Dis 1992;145:1321–1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gonzales E, Herrejon A, Incahurraga I, Blanquer R. Determinants of health-related quality of life in patients with pulmonary emphysema. Respir Med 2005;99:638–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kaplan RM, Ries AL, Reilly J, Mohsenifar Z. Measurement of health-related quality of life in the national emphysema treatment trial. Chest 2004;126:781–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Spencer S, Calverly PMA, Burge PS. Jones PW on behalf of the ISOLDE study group. Health status deterioration in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;163:122–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Niewoehner DE. The impact of severe exacerbations on quality of life and the clinical course of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Med 2006;119:38–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stolk J, Ng WH, Bakker ME, Reiber JH, Rabe KF, Putter H, Stoel BC. Correlation between annual change in health status and computer-tomography derived lung density in subjects with alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency. Thorax 2003;58:1027–1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stolk J, Putter H, Bakker EM, Shaker SB, Parr DG, Piitulainen E, Russi EW, Grebski E, Dirksen A, Stockley RA, et al. Progression parameters for emphysema: a clinical investigation. Respir Med 2007;101:1924–1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gietema HA, Schilham AM, van Ginneken B, van Klaveren RJ, Lammers JW, Prokop M. Monitoring of smoking-induced emphysema with CT in a lung cancer screening setting: detection of real increase in extent of emphysema. Radiology 2007;244:890–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jemal A, Ward E, Hao Y, Thun M. Trends in the leading causes of death in the United States, 1970–2002. JAMA 2005;294:1255–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Martinez FJ, Kotloff R. Prognostication in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: implications for lung transplantation. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2001;22:489–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cote CG. Surrogates of mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Med 2006;119:54–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hodgkin JE. Prognosis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin Chest Med 1990;11:555–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Anthonisen NR, Wright EC, Hodgkin JE. Prognosis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am Rev Respir Dis 1986;133:14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Anthonisen NR. Prognosis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results from multi-center clinical trials. Am Rev Respir Dis 1989;140:S95–S99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pinto-Plata VM, Cote C, Cabral H, Taylor J, Celli BR. The 6-minute walk distance: change over time and value as a predictor of survival in severe COPD. Eur Respir J 2004;23:28–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fisher MR, Criner GJ, Fishman AP, Hassoun P, Minai OA, Scharf SM, Fessler AH, et al. for the National Emphysema Treatment trial Research Group. Estimating pulmonary artery pressures by echocardiography in patients with emphysema. Eur Respir J 2007;30:914–921. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 87.Scharf SM, Iqbal M, Keller C, Criner G, Lee S, Fessler HE, for the National Emphysema Treatment trial Research Group. Hemodynamic characterization of patients with severe emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:314–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Oswald-Mammosser M, Weitzenblum E, Quoix E, Moser G, Chaouat A, Charpentier C, Kessler R. Prognostic factors in COPD patients receiving long-term oxygen therapy: importance of pulmonary artery pressure. Chest 1995;107:1193–1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Celli BR, Cote CG, Marin JM, Casanova C, Montes de Oca M, Mendez RA, Pinto Plata V, Cabral HJ. The body mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity index in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2004;350:1005–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Burrows B, Bloom JW, Traver GA, Cline MG. The course and prognosis of different forms of chronic airways obstruction in a sample from the general population. N Engl J Med 1987;317:1309–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Brantly ML, Paul LD, Miller BH, Falk RT, Wu M, Crystal RG. Clinical features and history of the destructive lung disease associated with alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency of adults with pulmonary symptoms. Am Rev Respir Dis 1988;138:327–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Seersholm N, Dirksen A, Kok-Jensen A. Airways obstruction and two year survival in patients with severe alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency. Eur Respir J 1994;7:1985–1987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Stoller JK, Aboussouan LS. Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Lancet 2005;365:2225–2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Martinez FJ, Foster G, Curtis JL, Criner G, Weinmann G, Fishman A, DeCamp MM, Benditt J, Sciurba F, Make B, et al.; NETT Research Group. Predictors of mortality in patients with emphysema and severe airflow obstruction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;173:1326–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hogg JC, Chu FS, Tan WC, Sin DD, Patel SA, Pare PD, Martinez FJ, Rogers RM, Make BJ, Criner GJ, et al. Survival after lung volume reduction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: insights from small airway pathology. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:454–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]