Abstract

It is clear that being underweight is a poor prognostic sign in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). It is also clear that undernutrition is at least in part associated with the severity of airflow obstruction. While both weight and body mass index are useful screening tools in the initial nutritional evaluation, fat-free mass (FFM) may be a better marker of undernutrition in patients with COPD. The causes of cachexia in patients with COPD are multifactorial and include decreased oral intake, the effect of increased work of breathing due to abnormal respiratory mechanics, and the effect of chronic systemic inflammation. Active nutritional supplementation in undernourished patients with COPD can lead to weight gain and improvements in respiratory muscle function and exercise performance. However, long-term effects of nutritional supplementation are not clear. In addition, the optimal type of nutritional supplementation needs to be explored further. The role of novel forms of treatment, such as androgens or appetite stimulants designed to increase FFM, also needs to be further studied. Thus, in the absence of definitive data, it cannot be said that long-term weight gain, either using enhanced caloric intake, with or without anabolic steroids or appetite stimulants, offers survival or other benefits to patients with COPD. However, there are indications from single-center trials that this is an avenue well worth exploring.

Keywords: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, nutrition, cachexia, testosterone, megace

It is recognized that chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a systemic disease whose manifestations extend beyond the pathophysiologic consequences of airflow obstruction and hyperinflation. Malnourishment and cachexia are particularly serious problems. While reduction in caloric intake may contribute in some patients, factors such as increased work of breathing, systemic inflammation, and specific therapeutic interventions are being investigated. Here we discuss these issues with some emphasis on the type of patient evaluated in the National Emphysema Treatment Trial (NETT) (1).

NUTRITIONAL STATES

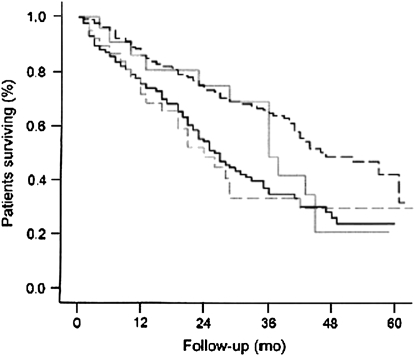

Common definitions of malnutrition include weight less than 90% of the predicted value as given by the Metropolitan Insurance Company, and/or body mass index (BMI) of less than 18.4 kg/m2 (2–6). The terms “malnutrition” and “cachexia” are often used interchangeably and defined by BMI. However, there are different states of low weight. For example, a patient with low body weight may have normal muscle (fat-free) mass for height, but decreased fat stores. Patients who are starving will first lose fat, preserving muscle mass. Only as caloric restriction becomes severe will they lose muscle. On the other hand, certain conditions (including COPD) can lead to cachexia, in which muscle and fat mass are lost in spite of adequate caloric intake. Thus, when assessing the nutritional state, simple measures of weight, even adjusted for height (BMI), may not characterize the overall nutritional state. Accordingly, in a large study of patients with COPD, Schols and coworkers distinguished three different types of impaired nutrition: semistarvation (low BMI with normal or above normal fat-free mass [FFM] index), muscle atrophy (low FFM index and normal or above-normal BMI), and cachexia (low BMI and low FFM index). Interestingly, patients with muscle atrophy and those with cachexia had similar outcomes. On the other hand, the groups with normal or above-normal BMI (semistarvation or no impairment) had better survival. Thus the groups with low FFM had greater mortality than the others, and it would appear that low FFM is a better predictor of mortality than low BMI (Figure 1) (2). Clearly, it was the type of low body weight, not low body weight per se, that predicted mortality.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves in different body composition categories in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Solid black line = cachexia (Category I; n = 117); solid gray line = semistarvation (Category 2; n = 23); dashed gray line = muscle atrophy (Category 3; n = 40); dashed black line = no impairment (Category 4; n = 232). Median survival was significantly (P < 0.001) less in patients with cachexia (26 months) and muscle atrophy (24 months) than patients with semistarvation (36 months) or no impairment (44 months). There was no significant difference between semistarvation or no impairment for the first 3 years. Reprinted by permission from Reference 1.

Body composition may also be used to assess undernutrition. Muscle atrophy occurs in patients with COPD. FFM, representing primarily muscle mass, has greater prognostic significance than either percentage of ideal body weight or BMI (2). FFM can be measured using different techniques, including hydrodensitometry and isotopic dilution methods. A simpler method is to use bioelectrical impedance, assuming three body compartments of different impedances. Schols and colleagues (7) demonstrated excellent correlation between FFM measurements by impedance and deuterium dilution in COPD. Finally, skin fold thickness is often used to estimate FFM; however, these estimates overestimate FFM compared to deuterium dilution.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND PROGNOSTIC SIGNIFICANCE OF UNDERNUTRITION IN COPD: COHORT STUDIES

From the late 1950s, it has been observed that many patients with COPD have low body weight. Further, patients who are underweight or are losing weight involuntarily have a higher mortality rate than other patients with COPD (3). The incidence of undernutrition in patients with COPD depends on disease severity and the methods used to define nutritional status. When defined as less than 90% of ideal body weight, 20 to 50% of patients with COPD are underweight. In the Intermittent Positive-Pressure Breathing (IPPB) Trial (4), 24% of the patients were underweight. Among patients with FEV1 of less than 35% predicted, 50% were undernourished. Thus, severity of airway obstruction increases the risk of undernutrition. In a negative pressure ventilation study, Gray-Donald and coworkers (5) showed that 18% of a cohort of 348 patients with COPD was underweight.

Marquis and colleagues (8) showed that among 142 patients with COPD, FEV1 and mid-thigh cross-sectional area by CT scan were independent and additive predictors of mortality. FFM, estimated anthropometrically, failed to predict mortality, showing that nutritional status assessed from precise measurements of FFM is more sensitive than anthropocentricity in reflecting the true nutritional deficit in COPD.

Other studies have examined the relationship between nutritional status and long-term outcome in COPD using the easily available metrics of weight and BMI. Landbo and coworkers (9) studied a cohort of 2,132 patients with COPD in the Copenhagen City Heart Study. As in smaller studies, they found increased mortality in patients with low BMI compared with subjects of normal weight. Further stratification showed that in severe COPD, BMI was a significant independent predictor of all-cause mortality. However, in patients with mild to moderate COPD, the association between mortality and BMI did not reach statistical significance. Interestingly, there was a U-shaped relationship between BMI and mortality, with increased mortality at high as well as low BMI levels, suggesting that malnutrition either manifested as obesity or cachexia increases all-cause mortality in mild to moderate COPD. In patients with severe COPD (requiring O2 supplementation), Chailleux and colleagues (10) demonstrated that BMI was positively correlated with FEV1 as well as vital capacity (VC) and arterial Pco2. The risk of death relative to patients with BMI over 30 kg/m2 was 1.4 for BMI 25 to 29 kg/m2, 1.8 for BMI 20 to 24 kg/m2, and 2.4 for BMI less than 20 kg/m2. In the IPPB trial, Wilson and coworkers (4) demonstrated a correlation between decreasing body weight and mortality. However, this relationship did not reach statistical significance in the most severely obstructed patients (FEV1 < 35% predicted). These different conclusions about the relationship between nutritional status, mortality, and severity of airflow obstruction highlight the need for agreed-upon definitions and accurate assessment of nutritional status. However, it is clear that patients with severe airflow obstruction who are also “underweight” have an increased mortality risk. Indeed, BMI is a component in the calculation of the BODE index (11), a prognostic indicator of mortality. Future stratifications by such measures as fat-free or muscle mass, systemic inflammation status, and markers of catabolism may more precisely stratify prognosis in future studies.

Acute exacerbations are a major component in the decrement of quality of life, increased mortality, and health care–related costs in COPD, and nutritional status may influence the occurence of acute exacerbations. Among 41 patients with COPD, only initial low BMI and weight loss during the 12-month follow-up period were independent risk factors for acute exacerbations (12).

MECHANISMS FOR WEIGHT LOSS IN COPD

Weight loss results from negative net energy balance, that is, less energy intake than energy output. Daily energy expenditure is composed of three parts: resting energy expenditure (REE) accounting for about 60%; diet-induced thermogenesis, accounting for less than 10%; and energy consumed for physical activity making up the rest. REE is elevated (∼120% normal) in patients with COPD. Donahoe and colleagues (13) studied 10 malnourished and 9 normally nourished patients with COPD and 7 control subjects. In malnourished patients, the oxygen cost of breathing was significantly higher than in the normally nourished and control group subjects. Therefore, it has been postulated that increased REE in undernourished patients with COPD is in part due to increased oxygen cost of breathing. However, increased work of breathing (WOB) cannot completely explain low body weight in patients with COPD. First, it would be expected that the more severe the obstruction, the greater would be WOB and REE. In 36 stable patients with COPD, Nguyen and coworkers (14) showed that REE did not correlate with the oxygen cost of breathing, FEV1, RV, or TLC. Another reason that WOB cannot completely explain the nutritional deterioration in patients with COPD is that treatment with noninvasive positive pressure ventilation, which decreases WOB, did not reduce REE to normal.

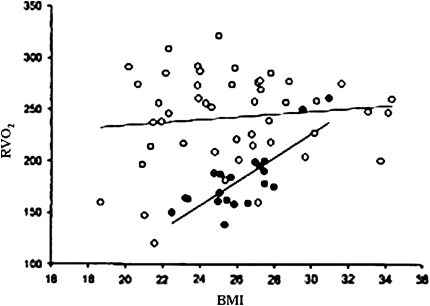

In patients with severe emphysema being evaluated for participation in the National Emphysema Treatment Trial, Cohen and colleagues (15) investigated the metabolic status of 79 weight and clinically stable patients compared with 20 healthy nonsmoking, age- and weight-matched control subjects. They measured lung function, body composition, serum leptin, and soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor concentration (sTNF-R), as well as resting O2 consumption (Rvo2). With increasing BMI, RVO2/kg body weight remained the same in control subjects but decreased in patients (Figure 2). The same relationships were found normalizing VO2 to FFM. There was no correlation between TLC and Rvo2. The latter findings contrast with those of Cruetzberg and coworkers (16), who found that the lower the TLC, the higher the REE. Different findings might be explained by the fact that Cruetzberg and colleagues did not distinguish between patients with and without emphysema, whereas by study design the patients of Cohen and coworkers all had severe emphysema.

Figure 2.

Relation between body mass index (BMI) and resting O2 consumption (Rvo2) in normal subjects (solid circles) and patients with emphysema (open circles). While there was a clear association between Rvo2 and BMI in normal subjects, this was not the case in patients with emphysema. The difference in slopes was significant (P < 0.01). Reprinted by permission from Reference 14.

Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) is a key proinflammatory cytokine associated with weight loss in malignancy, infections, inflammatory diseases, and severe heart failure. Di Francia and colleagues (17) found that TNF-α levels are elevated in underweight compared to normal-weight patients with COPD, after excluding infection, renal failure, or heart failure. Mean TNF-α levels in the underweight group were tenfold higher than in the normal weight group. In the NETT study (15), sTNF-R levels were elevated in patients compared with control subjects. However, there was no correlation between sTNF-R levels and Rvo2, BMI, or corticosteroid use. Thus, being underweight per se was not a predictor of systemic inflammation in these patients with emphysema. In contrast, Nguyen and colleagues (14) demonstrated a correlation between TNF-α levels and REE. The difference between these two studies might be explained by the methodology in estimating the secretion of TNF-α. TNF-α release is intermittent, whereas its receptors are an index of overall integrated TNF-α release over time. Possibly, it is peak levels of TNF-α that are the determinants of REE, rather than the overall integrated secretion over time as assessed by sTNF-α levels. It is also possible that patients with active airways inflammation (i.e., chronic bronchitis—less likely in the Cohen study because of NETT selection criteria) generate more systemic inflammation, resulting in higher REE. Finally, DiFrancia and coworkers (17) showed that some underweight patients with COPD had normal and some had elevated TNF-α levels, suggesting the need for careful phenotypic characterization.

TNF-α may also mediate muscle wasting by stimulating catecholamine secretion and muscle protein lysis. TNF-α causes an increase in REE even in normal subjects. However, the inconsistency of TNF-α levels in COPD suggests that this cytokine cannot be the only culprit leading to weight loss. It appears that the mechanisms for weight loss in COPD, and specifically in patients with emphysema, are multifactorial, and that the factors may affect different COPD phenotypes differently. In addition, chronic inflammation can lead to oxidant stress, which in turn leads to cell damage and drop-out (apoptosis) (18). However, oxidant stress can be modulated by the presence of inducible endogenous antioxidants. The degree to which oxidant stress occurs in any one patient could vary according to variations in genes responsible for these phenomena.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

The question naturally arises as to whether it is possible for patients with COPD to gain weight with adequate nutrition and if this makes a difference to respiratory function or survival. We will briefly review two approaches to facilitate weight gain in underweight patients with COPD: (1) nutritional supplementation programs and (2) novel approaches using anabolic compounds and appetite stimulants.

Nutritional Interventions

The first question is whether nutritional repletion can in fact lead to weight gain in patients with COPD. Wilson and colleagues (19) succeeded in increasing body weight in six underweight patients with COPD. They calculated the basal metabolic rate (BMR), and caloric goals were set at 150% of the BMR. If the subject did not reach that goal with daily diet, a nutritional supplement was given. Patients gained 3 kg in the 4-week study period on average and demonstrated an increase in the maximal inspiratory mouth (MIP) and transdiaphragmatic pressures, suggesting improved respiratory muscle function. No significant change occurred in lung function. Efthimiou and coworkers (20) randomized 14 underweight patients with COPD into a control and a nutritional supplementation group. Subjects were followed for 9 months. The intervention group received 3 months of “buildup” diet, increasing their daily calorie intake to 2,300 to −2,500 kcal/day and protein intake 80 to 90 g/day. Nutritional repletion increased body weight by 4 kg and resulted in improved respiratory muscle function. General sense of well being, breathlessness, and 6-minute walk were improved during the buildup diet. Following return to regular diet, well being and breathlessness remained improved. However, the 6-minute walk returned to the pre-intervention levels.

Because single-center trials appeared promising, Ferreira and colleagues (21) performed a meta-analysis of nutritional support in COPD on 277 patients from nine randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Unfortunately, the meta-analysis could not identify clinically significant consistent improvements in weight, arm muscle circumference, triceps skin fold thickness, 6-minute walk distance, FEV1, or maximum inspiratory and expiratory mouth pressure. Ferreira and coworkers concluded that nutritional supplementation has not yet been demonstrated to be effective in COPD. Of course, all meta-analyses suffer from inconsistencies in study design, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and outcomes that make interpretation at this early stage difficult.

The specific type of nutritional supplement might also be an important factor. Vermeeren and coworkers (22) examined the differences between a fat-rich versus carbohydrate-rich diet on exercise performance in COPD. They hypothesized that a fat-rich diet would be better tolerated than a carbohydrate-rich diet due to a lower Respiratory Quotient and thus lower CO2 production. Unexpectedly, they found that the fat-rich diet was associated with increased dyspnea. The authors attributed these findings to the fact that glucose is rapidly available and easily oxidized. Patients with COPD have lower oxidative capacity in respiratory muscles (23), which may make it more difficult to extract ATP from fats, since they require greater oxidative capacity and energy input before entry into the Krebs cycle.

Combining nutritional supplementation with pulmonary rehabilitation, Steiner and colleagues (24) found that a carbohydrate-rich dietary supplement of 570 kcal failed to improve exercise performance in patients with COPD. However, this program prevented weight loss, whereas the placebo group did lose weight. Interestingly, the subgroup of patients in the nutritional supplement group who had a normal BMI on entry did have significantly improved exercise performance.

Overall, it would appear that a carefully planned nutrition program can reverse undernutrition in patients with COPD, at least over the short term. Successful nutritional repletion in these patients can lead to improvement in exercise performance and respiratory muscle function. Future trials will need to standardize definitions of “underweight,” “malnourished,” and “cachectic.” Outcomes defined as “successful” will need to be carefully defined. For example, while weight gain could be a defined successful outcome, for this to be useful to the patient, the weight gain would need to lead to improved mortality and/or quality of life. It is clearly desirable to perform multicenter randomized clinical trials to help answer this important question.

Novel Interventions

The goal of muscle mass rebuilding should aim to enhance both strength and endurance. Testosterone and its derivatives are known to increase muscle mass. They lead to increased muscle cross-sectional area without much increase in capillary or aerobic enzyme concentration (25). Androgen supplementation has been shown to be successful in improving FFM in patients with COPD, but so far this treatment has failed to show improvements in muscle strength or endurance. To date, two small trials have investigated androgen supplementation combined with a pulmonary rehabilitation program.

Casaburi and colleagues (26) studied 47 patients with COPD with below-average testosterone levels. Patients were enrolled without regard to their weight status. Patients were randomized into four groups: (1) placebo injections and no exercise training, (2) placebo injections and exercise training, (3) testosterone enanthate 100 mg injected weekly and no exercise training, and (4) testosterone enanthate 100 mg injected weekly with exercise training. Both groups receiving testosterone demonstrated small increases in weight and lean body mass and decreased body fat. There was a significant improvement in quadriceps muscle fatigability in the testosterone and exercise training groups. The combination group (testosterone and exercise training) demonstrated greater improvement than the single-intervention groups. Only the combined therapy group showed small improvements in maximum exercise tolerance. It was also found that testosterone could reverse corticosteroid-induced respiratory muscle weakness (26), suggesting a role in patients being chronically treated with corticosteroids.

Creutzberg and coworkers (27) randomized 63 patients with COPD to four biweekly injections of 50 mg nandrolone decanoate or placebo. They found an increase in FFM but did not observe improvement in exercise tolerance. Nandrolone was associated with increased erythropoesis, and MIP, peak workload rate, and isokinetic legwork correlated positively with erythropoietin levels, suggesting that improvement with testosterone is due to increased peripheral oxygen delivery.

While these small single-site studies indicate that androgens may have some promise in COPD, especially for patients on corticosteroids or in conjunction with rehabilitation, large multisite studies of androgen supplementation are needed.

Progestational agents are known to increase body weight, appetite, and a sense of well being in underweight chronically ill patients, and they have also been studied in COPD. Weisberg and colleagues (28) studied 128 patients with COPD receiving 800 mg/day of megestrol acetate, a progestational agent, or placebo. After 8 weeks, the megestrol group gained 3.2 kg on average, as opposed to 0.7 in the placebo group. However, the change in weight was mainly due to fat and not muscle. There was no difference in maximal exercise performance between the two groups, although there was a small but significant decrease in 6-minute walk distance in the megestrol group.

Finally, Schols and colleagues (29) performed a retrospective evaluation of predictors of mortality in 400 patients and then prospectively validated the results. During the retrospective study, they found that low BMI, age, and hypoxemia were independent predictors of mortality. In the prospective trial, four groups were treated for 8 weeks: (1) no treatment, (2) nutritional support, (3) androgen treatment, and (4) both nutritional support and androgen treatment. Follow-up lasted 48 months. A significant increase in weight, FFM, and MIP were noted in all the treatment groups relative to the no-treatment group. However, among the three treatment groups, there were no significant differences. For all the treatment groups, weight gain and increased MIP were significant predictors of survival.

Based on the above, we believe it worthwhile to consider nutritional supplementation, possibly with the addition of anabolic agents (testosterone) or appetite enhancers (megestrol), in combination with a pulmonary rehabilitation program, in patients who fail to maintain normal weight. More studies are needed to characterize dose response, effects on exercise performance, duration of effect, and side effects. A large-scale trial would have to be performed under carefully controlled conditions. Nevertheless, given the poor prognosis of loss of muscle and FFM in these patients, these novel approaches could prove to be a valuable adjunct in the management of underweight patients with COPD.

CONCLUSIONS

Being malnourished is a poor prognostic indicator in COPD. Mechanisms for this, however, are not clear. The long-term effects of nutritional repletion, as well as anabolic and appetite-stimulating interventions, need to be evaluated in multisite, well-controlled clinical studies.

The National Emphysema Treatment Trial (NETT) is supported by contracts with the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (N01HR76101, N01HR76102, N01HR76103, N01HR76104, N01HR76105, N01HR76106, N01HR76107, N01HR76108, N01HR76109, N01HR76110, N01HR76111, N01HR76112, N01HR76113, N01HR76114, N01HR76115, N01HR76116, N01HR76118, and N01HR76119), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).

Conflict of Interest Statement: None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.The National Emphysema Treatment Trial Research Group. Rationale and design of the national emphysema treatment trial: a Prospective randomized trial of lung volume reduction surgery. Chest 1999;116:1750–1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schols AM, Broekhuizen R, Weling-Scheepers CA, Wouters EF. Body composition and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Clin Nutr 2005;82:53–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vandenbergh E, Van de Woestijne KP, Gyselen A. Weight changes in the terminal stages of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: relation to respiratory function and prognosis. Am Rev Respir Dis 1967;95:556–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson DO, Rogers RM, Wright EC, Antonesin NR. Body weight in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The National Institutes of Health Intermittent Positive-Pressure Breathing Trial. Am Rev Respir Dis 1989;139:1435–1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gray-Donald K, Gibbons L, Shapiro SH, Macklem PT, Martin JG. Nutritional status and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996;153:961–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harrison GG. Height-weight tables. Ann Intern Med 1985;103:989–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schols AM, Wouters EF, Soeters PB, Westerterp KR. Body composition by bioelectrical-impedance analysis compared with deuterium dilution and skinfold anthropometry in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Clin Nutr 1991;53:421–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marquis K, Debigaré R, Lacasse Y, LeBlanc P, Jobin J, Carrier G, Maltais F. Midthigh muscle cross-sectional area is a better predictor of mortality than body mass index in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:809–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Landbo C, Prescott E, Lange P, Vestbo J, Almdal TP. Prognostic value of nutritional status in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;160:1856–1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chailleux E, Laaban JP, Veale D. Prognostic value of nutritional depletion in patients with COPD treated by long-term oxygen therapy: data from the ANTADIR observatory. Chest 2003;123:1460–1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Celli BR, Cote CG, Marin JM, Casanova C, Montes de Oca M, Mendez RA, Pinto Plata V, Cabral HJ. The body-mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity index in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2004;350:1005–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hallin R, Koivisto-Hursti UK, Lindberg E, Janson C. Nutritional status, dietary energy intake and the risk of exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Respir Med 2006;100:561–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donahoe M, Rogers RM, Wilson DO, Pennock BE. Oxygen consumption of the respiratory muscles in normal and in malnourished patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am Rev Respir Dis 1989;140:385–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nguyen LT, Bedu M, Caillaud D, Beaufrère B, Beaujon G, Vasson M, Coudert J, Ritz P. Increased resting energy expenditure is related to plasma TNF-alpha concentration in stable COPD patients. Clin Nutr 1999;18:269–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen RI, Marzouk K, Berkoski P, O'Donnell CP, Polotsky VY, Scharf SM. Body composition and resting energy expenditure in clinically stable, non-weight-losing patients with severe emphysema. Chest 2003;124:1365–1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Creutzberg EC, Schols AM, Bothmer-Quaedvlieg FC, Wouters EF. Prevalence of an elevated resting energy expenditure in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in relation to body composition and lung function. Eur J Clin Nutr 1998;52:396–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Di Francia M, Barbier D, Mege JL, Orehek J. Tumor necrosis factor-α levels and weight loss in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994;150:1453–1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Venardos KM, Kay DM. Myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury, antioxidant enzyme systems, and selenium: a review. Curr Med Chem 2007;14:1539–1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson DO, Rogers RM, Sanders MH, Pennock BE, Reilly JJ. Nutritional intervention in malnourished patients with emphysema. Am Rev Respir Dis 1986;134:672–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Efthimiou J, Fleming J, Gomes C, Spiro SG. The effect of supplementary oral nutrition in poorly nourished patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am Rev Respir Dis 1988;137:1075–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferreira IM, Brooks D, Lacasse Y, Goldstein RS. Nutritional support for individuals with COPD: a meta-analysis. Chest 2000;117:672–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vermeeren MA, Wouters EF, Nelissen LH, van Lier A, Hofman Z, Schols AM. Acute effects of different nutritional supplements on symptoms and functional capacity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Clin Nutr 2001;73:295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maltais F, Simard AA, Simard C, Jobin J, Desgagnés P, LeBlanc P. Oxidative capacity of the skeletal muscle and lactic acid kinetics during exercise in normal subjects and in patients with COPD. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996;153:288–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steiner MC, Barton RL, Singh SJ, Morgan MD. Nutritional enhancement of exercise performance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomised controlled trial. Thorax 2003;58:745–751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sinha-Hikim I, Artaza J, Woodhouse L, Gonzalez-Cadavid N, Singh AB, Lee MI, Storer TW, Casaburi R, Shen R, Bhasin S. Testosterone-induced increase in muscle size in healthy young men is associated with muscle fiber hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2002;283:E154–E164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Casaburi R, Bhasin S, Cosentino L, Porszasz J, Somfay A, Lewis MI, Fournier M, Storer TW. Effects of testosterone and resistance training in men with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004;170:870–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Creutzberg EC, Wouters EF, Mostert R, Pluymers RJ, Schols AM. A role for anabolic steroids in the rehabilitation of patients with COPD? A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Chest 2003;124:1733–1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weisberg J, Wanger J, Olson J, Streit B, Fogarty C, Martin T, Casaburi R. Megestrol acetate stimulates weight gain and ventilation in underweight COPD patients. Chest 2002;121:1070–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schols AM, Slangen J, Volovics L, Wouters EF. Weight loss is a reversible factor in the prognosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;157:1791–1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]