Abstract

Hyperoxic acute lung injury (HALI) is characterized by a cell death response that is inhibited by IL-6. Suppressor of cytokine signaling-1 (SOCS-1) is an antiapoptotic negative regulator of the IL-6–mediated Janus kinase–signal transducer and activator of transcription signaling pathway. We hypothesized that SOCS-1 is a critical regulator and key mediator of IL-6–induced cytoprotection in HALI. To test this hypothesis, we characterized the expression of SOCS-1 and downstream apoptosis signal–regulating kinase (ASK)-1–Jun N-terminal kinase signaling molecules in small airway epithelial cells in the presence of H2O2, which induces oxidative stress. We also examined these molecules in wild-type and lung-specific IL-6 transgenic (Tg+) mice exposed to 100% oxygen for 72 hours. In control small airway epithelial cells exposed to H2O2 or in wild-type mice exposed to 100% oxygen, a marked induction of ASK-1 and pJun N-terminal kinase was observed. Both IL-6–stimulated endogenous SOCS-1 and SOCS-1 overexpression abolished H2O2-induced ASK-1 activation. In addition, IL-6 Tg+ mice exposed to 100% oxygen exhibited reduced ASK-1 levels and enhanced SOCS-1 expression compared with wild-type mice. Interestingly, no significant changes in activation of the key ASK-1 activator, tumor necrosis factor receptor-1/tumor necrosis factor receptor–associated factor-2 were observed between wild-type and IL-6 Tg+ mice. Furthermore, the interaction between SOCS-1 and ASK-1 promotes ubiquitin-mediated degradation both in vivo and in vitro. These studies demonstrate that SOCS-1 is an important regulator in IL-6–induced cytoprotection against HALI.

Keywords: IL-6, apoptosis signal–regulating kinase-1, suppressor of cytokine signaling-1, lung injury, tumor necrosis factor receptor-1

CLINICAL RELEVANCE

These studies demonstrate, for the first time, that IL-6–induced protection against hyperoxic acute lung injury works through suppressor of cytokine signaling-1–induced apoptosis signal–regulating kinase-1 ubiquitin-mediated degradation.

Hyperoxia, which enhances oxygen delivery, is a necessary part of therapy for cardiopulmonary diseases. Unfortunately, the delivery of supplemental oxygen at a high fraction (> 65%) of inspired air for prolonged periods has deleterious effects, and may even cause acute lung injury (ALI). In fact, lung injury is associated with epithelial and endothelial cell necrosis and apoptosis (1, 2). Earlier reports indicated that IL-1 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α induce tolerance. In addition, antioxidants play an important role in protective responses against hyperoxic ALI (HALI) (3, 4); however, antioxidants alone do not reverse or prevent the entire spectrum of HALI (2, 4). Recent studies from our laboratory and others have shown that cytokines, such as IL-11 and IL-6, confer significant protection in HALI, and that this response is the result of the ability of IL-11 and IL-6 to inhibit hyperoxia-induced cell death without causing major alterations in lung antioxidants (1, 2). The molecular mechanisms of these protective effects have not yet been clearly elucidated. IL-6 is a proinflammatory cytokine secreted during inflammation. Clara cell 10 kD protein (CC10)–IL-6 lung-specific overexpression transgenic (IL-6 Tg+) mice demonstrated significant enhanced survival in 100% oxygen compared with wild-type animals. IL-6–type cytokines decrease oxygen-induced cell death, DNA fragmentation, and granulocyte infiltration (1).

Suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS)-1 is a member of the suppressor of cytokine signaling family of proteins. This protein inhibits IL-6 via inhibition of the Janus kinases (Jaks) (5, 6). SOCS-1 exerts protective effects in a variety of settings, including apoptosis induced by TNF-α (7), LPS (8, 9), and IFN-γ (10, 11). The protective effects of SOCS-1 during oxidative stress have not been revealed.

SOCS-1 inhibits TNF-α–mediated p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) (7). Apoptosis signal–regulating kinase-1 (ASK-1), an upstream component of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, is a pivotal regulator of oxidative stress–induced cell death (12). Proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-1, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) activate ASK-1 and Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling in endothelial cells (13–15). Furthermore, MEFs isolated from ask1−/− mice were resistant to H2O2 and TNF-α–induced cell death (16). SOCS-1 can degrade ASK-1, thereby inhibiting TNF-α–induced activation of ASK-1/JNK signaling (17); however, the role of SOCS-1 in the oxidative stress–induced apoptotic signaling in HALI has not been studied.

Thus, we hypothesized that SOCS-1 is a critical regulator of HALI and a key mediator of IL-6–induced cell death protection. To test this hypothesis, we characterized the expression of SOCS-1 and the downstream ASK-1/JNK signaling pathway in small airway epithelial cells (SAECs) with and without H2O2, an agent that mimics oxidative stress, as seen in HALI. In addition, wild-type and IL-6 Tg+ mice were exposed to 72 hours of 100% oxygen, and the expression patterns of SOCS-1 and the ASK-1/JNK signaling molecules were determined. These studies demonstrate, for the first time, that IL-6–induced protection against HALI occurs via SOCS-1–induced ASK-1 ubiquitin-mediated degradation. These studies also demonstrate that either hyperoxia- or H2O2-induced ASK-1 is a key event in oxidative stress–induced apoptosis. Both IL-6–induced SOCS-1 and SOCS-1 overexpression were associated with diminished caspase activation during oxidative stress. Finally, no significant change in TNF receptor (TNFR)-1/TNFR–associated factor (TRAF)-2 activation was observed between wild-type and IL-6 Tg+ mice exposed to 100% oxygen. The interaction of TRAF-2 and ASK-1 is important in oxidative stress–induced apoptosis. Taken together, these results demonstrate that, under high-oxygen conditions, IL-6–induced SOCS-1 expression, or overexpression of SOCS-1, is cytoprotective via interaction and degradation of ASK-1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies and Reagents

The following antibodies were obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN): recombinant human IL-6, monoclonal anti–human IL-6R, anti–signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)-3, anti–phospho–STAT-3, anti–TNFR-1, anti–TRAF-2, and anti-TNFR-associated death domain protein (TRADD). Phospho–ASK-1, caspase-3, cleaved caspase-3, caspase-8, and cleaved caspase-8 antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Beverly, MA). SOCS-1 and SOCS-3 antibodies were purchased from Immuno-Biological Laboratories (Minneapolis, MN). ASK-1, p-JNK, and JNK antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). All other reagents were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Mice

IL-6 Tg+ mice were generated as previously described (2). In all cases, transgene− littermates served as controls. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Massachusetts General Hospital at Harvard Medical School approved all mouse work.

Oxygen Exposure

Mice (4 to 6 wk old) were placed in cages in an airtight chamber (50 × 50 × 30 cm) and exposed to 100% oxygen for 72 hours. The oxygen concentration in the chamber was monitored with an oxygen analyzer (Vascular Technology, Inc., Chelmsford, MA), as described previously (1, 2, 18, 19).

Cell Culture

Because cytoprotection plays an important role in IL-6–induced protection from oxidant-mediated cellular injury, a biologically relevant system in which cytoprotective effects could be evaluated independently of inflammation and other host responses is important. Thus, we characterized the effects of H2O2 on cultured cells. We have shown previously that, compared with microvascular cells, SAECs have a dramatic response to hyperoxia and oxidant stress (20). Primary human SAECs (Cambrex) from two individuals were grown in Small Airway Cell Basal Medium supplemented with growth factors and antibiotics according to the manufacturer's instructions. Confluent cultured cells were treated with IL-6, as described previously (21). Briefly, cells were treated with IL-6 every 3 hours at 37°C, and then the medium was removed and replaced with standard growth medium containing 80 μM H2O2. After an additional 1-hour incubation, the cells were evaluated by Western blot analysis.

Trypan Blue Exclusion

Cell viability assays were performed as described previously (21). SAECs in culture suspension were exposed to Trypan blue dye (0.04% in PBS) after exposure to H2O2 for 1 hour, placed on a hemocytometer, and cells were examined using a light microscope. A total of 200 random cells were counted after each treatment, and the percentage of blue (dead) cells was expressed as the percentage of viable cells for any given condition.

Propidium Iodide and Annexin V Staining

Floating and adherent cells were harvested 24 to 48 hours after treatment, washed once with 1 ml PBS with 5 mM EDTA, and fixed with 1 ml of 70% ethyl alcohol while vortexing gently. Fixed cells were stored at 4°C from 1 hour to several days. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation, washed once with 1.0 ml PBS with 5 mM EDTA, and resuspended in 0.3 to 1.0 ml propidium iodide (PI) mix (250 μg/ml PI, 5 μg/ml RNase A, 1× PBS, and 5 mM EDTA). After incubation in the dark for 1 hour at room temperature, the cells were analyzed on a FACscan (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ), and apoptotic (sub-G1 population) and necrotic cells were quantified as described previously (21).

Plasmid Constructs

Mammalian expression plasmids for wild-type and mutant ASK-1 and mutant SOCS-1 were provided by Dr. Wang Min of Yale University (17). The wild-type SOCS-1 expression plasmid was provided by Dr. Tadamitsu Kishimoto (7) from Osaka University, Japan. Green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter construct for transfection efficiency was purchased from Genlantis, Inc. (San Diego, CA).

Transfection

SAECs were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000-plus according to the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Cells were cultured to 90% confluence in six-well plates and then transfected with a total of 4 μg of plasmid DNA. The medium was changed every 12 hours after transfection. SAECs were transfected with nontargeted β-Gal small interfering RNA (siRNA) as a control (sense sequence, UUAUGCCGAUCGCGUCACAUU) or SOCS-1 siRNA (sense sequence, GCAUCCGCGUGCACUUUCAUU) using DharmaFECT (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO) following the manufacturer's protocol. Cells were harvested 36–48 hours after transfection, and cell lysates were used for protein assays. Transfection efficiency was determined using real-time PCR analysis (see Figure E1 in the online supplement) and by using a plasmid expressing the reporter protein, GFP, and quantifying the percentage of immunoflurescent cells (Figure E2). Transfection conditions were exactly the same for all transfection experiments. We observed 73–87% of transfection efficiency in SAECs. Protein expression was confirmed by Western blot.

Western Blot Analysis

After stimulation of SAECs with IL-6 (100 ng/ml), cells were lysed in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris HCl [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, 100 μM sodium vanadate, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 5 mg/ml leupeptin, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride), and centrifuged at 15,000 × g at 4°C for 15 minutes. Protein from mouse lungs was extracted, as described above, after homogenization of the whole lung. Supernatants were boiled in 6× SDS reducing sample buffer, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes, as described previously (2, 18, 21). After blocking in Tris-buffered saline (TBS)–Tween (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20) containing 5% dry skim milk, the membranes were probed with the appropriate primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. The following antibodies were used: anti–STAT-3, anti–phospho–STAT-3, anti–cleaved caspase-3, anti–SOCS-1, anti–SOCS-3, anti–ASK-1, anti–pASK-1, anti-TRADD, anti–TNFR-1, anti–TRAF-2, anti-Ub, and anti-GAPDH. The membranes were washed with TBS and incubated with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated anti-rabbit (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), anti-mouse, or anti-goat secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc, West Grove, PA) for 1.5 hours at room temperature. The membranes were washed twice with TBS–Tween for 15 minutes. Blots were visualized with the 20× LumiGLO reagent and 20× peroxide according to the manufacturer's instructions (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) on Kodak Biomax MR film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY).

Immunoprecipitation

Immunoprecipitation was performed using the Seize Classic Mammalian Immunoprecipitation kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Inc., Rockford, IL). Approximately 100 μg of protein from SAECs or lung homogenates was incubated with goat anti–SOCS-1, anti–TNFR-1, or anti–ASK-1 antibody (3–5 μg) at 4°C overnight with agitation. The protein–antibody complex was further incubated with protein A/G-agarose gel (35 μl) for 2 hours. After the samples were washed with the immunoprecipitation buffer (50 mM sodium acetate buffer [pH 5.0], 500 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 1% NP-40, and 0.02% sodium azide), the protein bound to the beads was eluted with 0.1 M glycine-HCl buffer (pH 2.5) and then neutralized to pH 7.5 with 1.0 M Tris (pH 7.5). The eluted protein was then subjected to Western blot analysis as described previously (17, 22).

Statistical Analysis

Data sets were examined by one- and two-way analysis of variance, and individual group means were then compared with Student's unpaired t test. The levels of statistical significance are indicated in the figures.

RESULTS

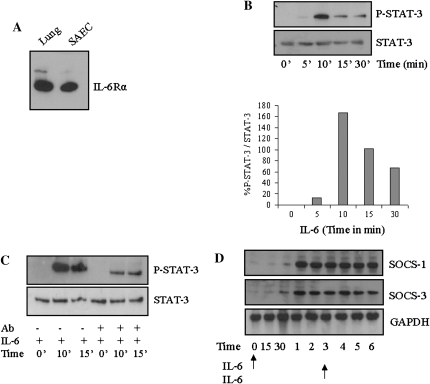

IL-6 Induces Phosphorylation of STAT-3 and Expression of SOCS-1 in SAECs

The presence of functional IL-6 receptors in SAEC was verified by Western blot analysis (Figure 1A). Treatment of SAECs with recombinant human IL-6 led to increased phosphorylation of STAT-3 (Figure 1B). Western blotting of the same samples with anti–STAT-3 demonstrated that the total levels of STAT-3 were not altered by treatment with IL-6. In addition, pretreatment of SAECs with anti–IL-6Rα inhibited IL-6–induced STAT-3 phosphorylation (Figure 1C), indicating an essential role of IL-6Rα in this activation. IL-6 treatment also led to increased SOCS-1 and SOCS-3 expression. Because SOCS proteins have a short half-life, and to mimic the conditions in the overexpression transgenic mice, we treated the cells with IL-6 twice. With chronic exposure to IL-6, SOCS-3 expression was maintained, and SOCS-1 levels increased to maximal levels of expression (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

IL-6 induces phosphorylation of signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)-3 and suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) expression in small airway epithelial cells (SAECs). (A) Freshly obtained SAEC lysates or whole-lung homogenates were assessed for protein expression of IL-6Rα by Western blot. (B) STAT-3 is activated by IL-6 in SAECs. SAECs were treated with IL-6 (100 ng/ml) for the indicated time periods. Lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with specific antibodies to either p-STAT-3 or STAT-3. The graph depicts the ratio of phospho–STAT-3 to total STAT-3. (C) Anti-human IL-6Rα antibody blocks IL-6–induced STAT-3 phosphorylation in SAECs. SAECs were treated with IL-6Rα (1 μg/ml) for 90 minutes. After incubation, cells were either treated with media alone (control) or media containing IL-6 (100 ng/ml) for the indicated time intervals. Lysates were resolved on SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with specific antibodies to p-STAT-3 or STAT-3. (D) SAECs were treated with IL-6 at Hour 0 and Hour 3 (arrows), and then analyzed for SOCS-1 and SOCS-3 protein expression at different time periods. These experiments are representative of a minimum of four similar evaluations.

IL-6 Suppresses the ASK-1/JNK Signaling Pathway via Expression of SOCS-1

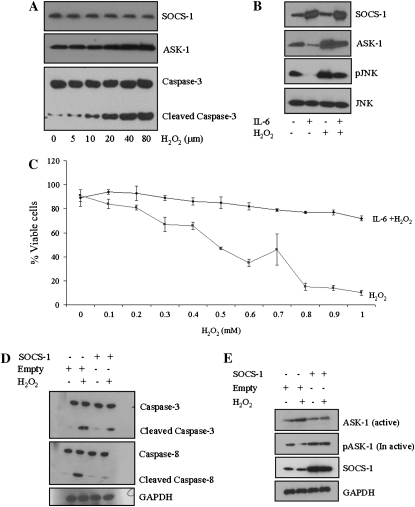

ASK-1 is induced by inflammatory cytokines, H2O2, and other stress-related stimuli involved in the regulation of diverse physiological functions, including apoptosis (12–16). To examine whether H2O2 activated ASK-1 and mediated apoptosis in SAECs, we assessed the levels of cleaved caspase-3 after H2O2 treatment. A clear activation of the apoptotic signaling intermediates, caspase-3 and ASK-1, was observed, and this activation occurred in an H2O2 dose–dependent manner (Figure 2A). To determine whether protection from oxidant-mediated cell death by IL-6 occurred, in part, via suppression (or interruption) of the ASK-1/JNK signaling pathway, SAECs were incubated in the presence and absence of IL-6 after 3 hours for a period of 1 hour and then exposed to 80 μM H2O2 for another hour. Exposure of control SAECs to H2O2 resulted in significant activation of ASK-1 and phosphorylation of JNK. When cells were pretreated with IL-6, however, suppression of both ASK-1 activation and phosphorylation of JNK was observed compared with baseline and exposure to H2O2 (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

IL-6 suppresses the apoptosis signal–regulating kinase (ASK)-1/Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling pathway via expression of SOCS-1. (A) Dose-dependent activation of caspase-3 and ASK-1 by H2O2 in SAECs. SAECs were incubated with media alone (control) or media containing H2O2 at various concentrations (μm). Lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with specific ASK-1 or caspase-3 antibodies. (B) IL-6 diminishes H2O2-induced ASK-1 levels. (C) IL-6 inhibits H2O2-induced cell death at concentrations of H2O2 from 0.1 to 1 mM. (D) SOCS-1 overexpression reduces H2O2-induced cleaved caspase-3 and caspase-8 in SAECs. (E) SOCS-1 overexpression diminishes H2O2-induced ASK-1 in SAECs. In both (D) and (E), SAECs were transfected with SOCS-1 expression plasmid or empty vector and then exposed to H2O2 (80 μm). Cell lysates were then subjected to Western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies. (F) Comparison of the survival rate of cells with SOCS-1 overexpression, SOCS-1 silence (SOCS-1 small interfering RNA [siRNA]), and control siRNA in the presence and absence of H2O2 with or without IL-6. In each case, survival was determined by Trypan blue exclusion staining. ¶SOCS-1 overexpression or IL-6 treatment protects H2O2-induced cell death. IL-6 fails to protect against H2O2-induced cell death after SOCS-1 silencing via siRNA. In all cases, the asterisk indicates significantly enhanced survival compared with H2O2 treatment and appropriate controls (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01). (G) SOCS-1 siRNA was transfected into SAECs using Lipofectamine 2,000. SOCS-1 expression was analyzed by Western blot using a SOCS-1 antibody and compared with nontarget β-galactosidase siRNA and untreated SAECs. (H) Exposure to H2O2 (80 μm) induces apoptosis. Annexin V staining and propidium iodide (PI) incorporation were measured by flow cytometry to assess the mode of cell death. Relative fluorescence units represent the intensity of annexin V incorporation (x axis) and PI incorporation (y axis). The noted experiments are representative of a minimum of four similar evaluations.

SOCS-1, which is a known inhibitor of IL-6 that functions via inhibition of the Jaks (5, 6, 23, 24), has been shown to induce ASK-1 degradation (17). Therefore, we investigated whether SAECs preconditioned with IL-6 followed by exposure to H2O2 exhibited altered SOCS-1. A significant increase in SOCS-1 expression was noted (Figure 2B), suggesting a concomitant reduction of ASK-1 expression. To verify that IL-6 protects SAECs from oxidant-mediated cell death, SAECs were grown to confluence in medium containing 2% serum, treated with IL-6 (100 ng/ml), and exposed to varying concentrations of H2O2 (0.1–1.0 mM) for 1 hour. H2O2 induced cell death in a dose-dependent manner, and IL-6 significantly inhibited this H2O2-induced cell death (Figure 2C).

To better understand whether IL-6 protection is mediated by SOCS-1, SAECs were transfected with a SOCS-1 overexpression plasmid. After 24 hours, the transfected cells were exposed to H2O2. SOCS-1 overexpression, which was confirmed by Western blotting (Figure 2E), inhibited H2O2-induced cleavage of caspase-3 (Figure 2D). In addition, overexpression of SOCS-1 resulted in coincident suppression of the active form of ASK-1 and increased expression of the inactive form of ASK-1 (pASK-1967) (Figure 2E). Taken together, these findings suggest that increased IL-6 results in increased SOCS-1, which, in turn, suppresses the active form of ASK-1.

To better understand the role of SOCS-1 in IL-6–induced cell protection, we employed siRNA to block endogenous SOCS-1 expression (Figure 2G). Cells were treated with SOCS-1 siRNA for 24 hours and then exposed to H2O2. Cells cultured in the presence of SOCS-1 siRNA alone were not protected from oxidant-mediated cell death. With the addition of IL-6, H2O2-treated SOCS-1 siRNA–cultured cells exhibited statistically significant (P < 0.05) improved survival, albeit less dramatic than the control cells or cells treated with IL-6 alone (Figure 2F). To further assess the cytoprotective effects of SOCS-1 and oxidant-induced cell death on SAECs in culture, we assessed annexin V levels and PI incorporation by flow cytometry in SAECs transfected with SOCS-1 or control vector. H2O2 increased the number of SAECs undergoing apoptosis (Figure 2H, lower right quadrant of each panel) or necrosis (Figure 2H, upper left quadrant of each panel). Some cells had features of both apoptosis and necrosis (Figure 2H, upper right quadrant of each panel). When compared with cells transfected with the control vector, cells stably transfected with SOCS-1 showed a significant decrease in H2O2-induced apoptosis, and mixed death responses. When viewed in combination, these studies demonstrate that SOCS-1 is a potent inhibitor of oxidant-induced lung epithelial cell death in vitro.

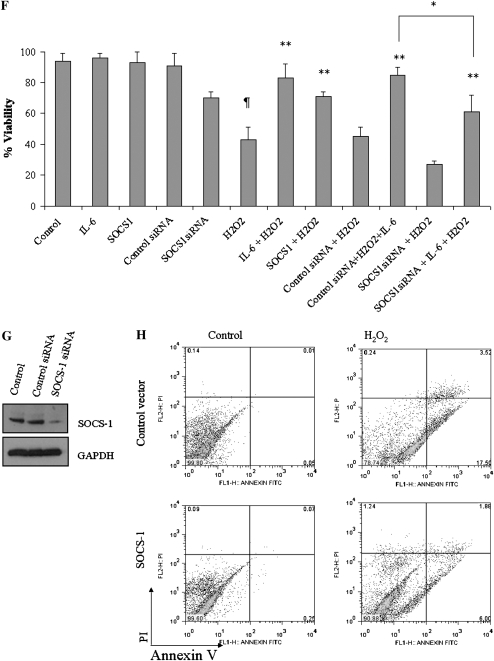

The Protective Effects of IL-6 Involve the Interaction of ASK-1 and SOCS-1

To better understand the mechanism by which IL-6 treatment results in the degradation of ASK-1, SAECs were treated with IL-6 and then exposed to H2O2. The lysates were then immunoprecipitated with an anti–ASK-1 antibody and immunoblotted with anti–SOCS-1 and anti–ASK-1 antibodies. ASK-1 coprecipitated with SOCS-1, confirming the interaction of SOCS-1 with ASK-1 (Figure 3A). SAECs were then transfected with wild-type or mutant (ASK-1-YF, a mutant that lacks the tyrosine phosphorylation site essential for SOCS-1 binding) ASK-1 in the presence or absence of a SOCS-1 construct. The interaction between SOCS-1 and ASK-1 was observed in cells cotransfected with wild-type ASK-1 and SOCS-1, but was eliminated when cells were cotransfected with the mutant ASK-1 and SOCS-1 (Figure 3B). To determine whether SOCS-1 affects ASK-1 protein stability, SAECs were cotransfected with SOCS-1 and either wild-type or mutant (ASK-1-YF) ASK-1 and assessed for ubiquitination/degradation of ASK-1 by Western blotting. Overexpression of SOCS-1 reduced the overall protein level of ASK-1 with a concomitant increase of ASK-1 high–molecular weight bands (Figure 3C). Immunoprecipitation of protein from SAEC lysates that overexpressed wild-type ASK-1 and SOCS-1 with anti–ASK-1 demonstrated the presence of high–molecular weight bands, consistent with ubiquitination and degradation of ASK-1 (Figure 3C). Immunoprecipitating these same samples with anti–ASK-1 and immunoblotting for ubiquitin confirmed that these high–molecular weight proteins were polyubiquitinated (Figure 3C). No ubiquitination of ASK-1 was detected (Figure 3C, lane 5), however, when SAECs were transfected with SOCS-1 and the ASK-1-YF mutant, presumably due to the lack of binding between SOCS-1 and the mutant ASK-1 protein. In addition, a mutant SOCS-1 that lacks the SH2 domain failed to induce ASK-1 degradation (Figure 3D). Together, these results indicate that SOCS-1 overexpression in SAECs induced ASK-1 ubiquitination and degradation. Furthermore, the data suggest that the association of SOCS-1 with ASK-1 is required for SOCS-1–induced ASK-1 ubiquitination and degradation, and that the SH2 domain in SOCS-1 is critical for ASK-1 binding.

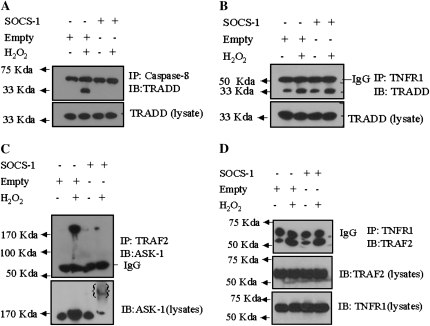

Figure 3.

SOCS-1 interacts with ASK-1 and induces ASK-1 degradation in vitro. (A) Total lysates treated with H2O2 (80 μm) and IL-6 were used as the positive control (+VE); lysates immunoprecipitated with anti-ASK-1 antibodies are marked as IP; and lysates immunoprecipitated with rabbit IgG were used as the negative control (−VE). (B) SOCS-1 interaction with ASK-1 is important for ASK-1 degradation. SAECs were cotransfected with SOCS-1 cDNA and either wild-type or mutant ASK-1. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with SOCS-1 antibodies (left panels) and probed for the presence of SOCS-1 and ASK-1 via Western blot. (C) SOCS-1 promotes ASK-1 ubiquitination and degradation. SAECs were cotransfected with SOCS-1 and either wild-type or mutant ASK-1 or a control vector. ASK-1 polyubiquitination was determined by immunoprecipitation with anti–ASK-1 followed by Western blot with anti-Ub. The poly-Ub chains are indicated in braces (lane 4). SOCS-1 does not induce ubiquitination and degradation of the ASK-1 mutant (lane 5). (D) The SH2 domain in SOCS-1 is critical for ASK-1 ubiquitination. SAECs were cotransfected with either wild-type or mutant SOCS-1 and ASK-1 expression constructs, or with a control vector. The lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti–ASK-1 antibody, and then ubiquitinated ASK-1 was determined by Western blot analysis. (E) SOCS-1 inhibits ASK-1–induced activation of caspase-3 in SAECs. Transfection of wild-type ASK-1, but not mutant ASK-1, permitted inhibition by SOCS-1. (F) Expression of ASK-1, ASK-1 mutant vector, and empty vector in the presence and absence of SOCS-1. The noted experiments are representative of a minimum of three similar evaluations.

To further examine the effect of SOCS-1 on the stability of ASK-1 and its role in apoptosis, we evaluated cleaved caspase-3 in cells cotransfected with SOCS-1 and either the wild-type or mutant (ASK-1-YF) ASK-1. Overexpression of either wild-type or mutant ASK-1 alone induced cleavage of caspase-3. In contrast, overexpression of SOCS-1 along with wild-type ASK-1 inhibited ASK-1–mediated caspase-3 cleavage, whereas overexpression of SOCS-1 with the ASK-1-YF mutant did not alter the ASK-1–mediated caspase-3 cleavage (Figure 3E). Expression of SOCS-1 and ASK-1 in the transfected cells was confirmed by Western blotting (Figure 3F). These observations suggest that, in SAECs, SOCS-1 serves to protect cells by minimizing ASK-1–mediated caspase-3 cleavage via degradation of the active form of ASK-1.

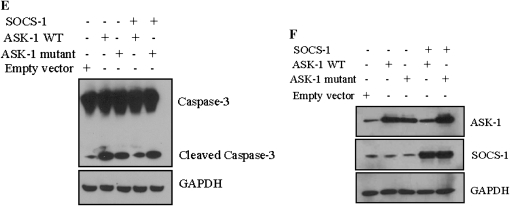

SOCS-1 Interrupts the H2O2-Induced Interaction between TRADD and Caspase-8

TNFR-1 binding with TRADD recruits TRAF-2, Fas-associated death domain protein, and caspase-8, to form the death-inducing signaling complex (DISC) and induce apoptosis under stress conditions (25). To investigate whether SOCS-1 affects DISC formation in SAECs exposed to H2O2, we examined the interaction between caspase-8 and TRADD. Lysates from SAECs that had been transfected with either the SOCS-1 overexpression vector or empty vector and then treated with H2O2 were immunoprecipitated with anti–caspase-8 antibodies and analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-TRADD antibody. In cells that were transfected with the empty vector, H2O2 exposure induced the interaction between caspase-8 and TRADD. In contrast, overexpression of SOCS-1 resulted in no interaction between caspase-8 and TRADD (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Effect of SOCS-1 overexpression on the interactions between tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor (TNFR)-1 signaling moieties in SAECs. For all experiments, SAECs were transfected with SOCS-1 or empty vector and then treated with H2O2 (80 μm) or medium alone. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with the indicated antibody (IP) and then subjected to Western blotting with the indicated antibody (IB). (A) SOCS-1 overexpression interrupts the H2O2-induced interaction between TNFR-associated death domain protein (TRADD) and caspase-8. (B) SOCS-1 overexpression has no effect on the H2O2-induced interaction between TNFR-1 and TRADD. (C and D) SOCS-1 interrupts the interaction between ASK-1 and TNFR-associated factor (TRAF)-2, but not between TNFR-1 and TRAF-2. The noted experiments are representative of a minimum of three similar evaluations.

Similarly, we examined the interaction between TNFR-1 and TRADD in SAECs that had been transfected with SOCS-1 or empty vector and then exposed to H2O2. SAEC lysates were immunoprecipitated using an anti–TNFR-1 antibody, and samples were analyzed by Western blotting with an anti-TRADD antibody. Exposure to H2O2 induced the interaction between TNFR-1 and TRADD, and SOCS-1 overexpression did not affect the interaction between these proteins (Figure 4B). These data suggest that SOCS-1 inhibits the H2O2-induced DISC formation via alteration of the TRADD/caspase-8 interaction, but not via alteration of the TNFR-1/TRADD interaction.

Following oxidative stress, TRAF-2 binds and thereby activates ASK-1, leading to cell death (26–28). To examine the effects of SOCS-1 on ASK-1–mediated apoptosis, we first examined the interaction between ASK-1 and TRAF-2 in SAECs that overexpressed SOCS-1 after exposure to H2O2 for 1 hour. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated using an anti–TRAF-2 antibody, and samples were analyzed by Western blotting using an anti–ASK-1 antibody. Exposure of control SAECs that had been transfected with empty vector to H2O2 resulted in an enhanced interaction between TRAF-2 and ASK-1, whereas overexpression of SOCS-1 in these cells resulted in a marked reduction in this interaction due to reduced levels of ASK-1 (Figure 4C). To examine the interaction between TNFR-1 and TRAF-2, cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with a TNFR-1 antibody and subjected to Western blotting using an anti–TRAF-2 antibody. As expected, treatment with H2O2 resulted in enhanced interactions between TNFR-1 and TRAF-2 in SAECs transfected with either SOCS-1 or empty vector (Figure 4D). The levels of TNFR-1 and TRAF-2 were stable under all conditions (Figure 4D).

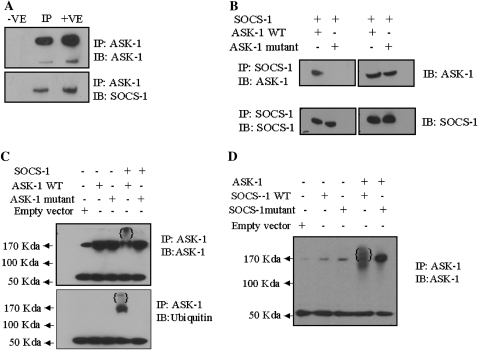

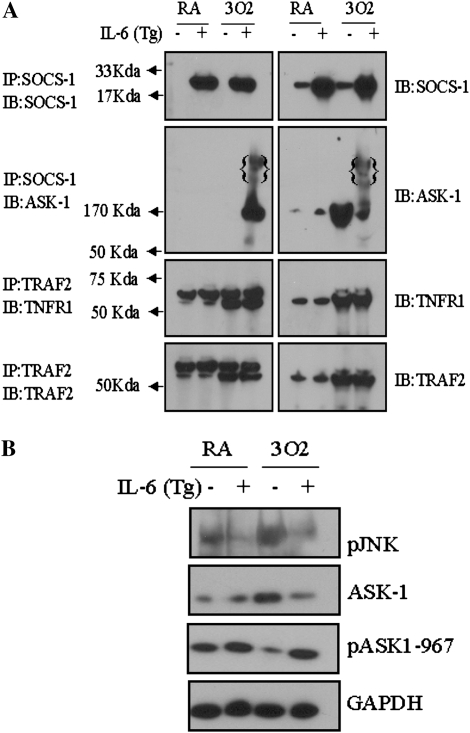

SOCS-1 Degrades Activated ASK-1 in CC10–IL-6 Overexpression Mice in Hyperoxic Conditions

The in vitro results suggest that IL-6–induced protection may be mediated via the interaction between ASK-1 and SOCS-1. Thus, CC10–IL-6 overexpression–transgenic mice were used to compare the expression of ASK-1 and SOCS-1 before and after exposure to 100% oxygen. Impressive differences in the levels of SOCS-1 in wild-type and IL-6 Tg+ mice were noted (Figure 5A). At baseline, the levels of SOCS-1 were significantly greater in IL-6 Tg+ mice than in wild-type mice. Exposure to 100% O2 for 72 hours did not significantly alter these levels. In contrast, the levels of the active form of ASK-1 increased with exposure to 100% oxygen in the wild-type mice, but not in the IL-6 Tg+ mice (Figure 5A). Additionally, degradation of ASK-1 was enhanced in the IL-6 Tg+ mice after exposure to 100% oxygen (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

SOCS-1 degrades activated ASK-1 in IL-6 Tg+ mice, but has no effect on the interaction between TNFR-1 and TRAF-2 in hyperoxia. (A) Total lung homogenates were assessed for expression of TNFR-1, ASK-1, TRAF-2, and SOCS-1 in wild-type and IL-6 Tg+ mice before (RA) and after (3O2) exposure to 100% oxygen. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with the indicated antibody (IP) and then subjected to Western blot analysis with the indicated antibody (IB). (B) ASK-1 and pJNK expression in wild-type and IL-6 Tg+ mice before (RA) and after (3O2) exposure to 100% oxygen. The noted experiments are representative of a minimum of four similar evaluations.

TRAF-2, an adapter protein that is recruited to TNFR-1 after exposure to oxidative stress, binds to and activates ASK-1 (22). Thus, we more thoroughly investigated the role of the TNFR-1/TRAF-2 and JNK pathways in IL-6–mediated protection. No significant differences were observed in the expression levels of either TNFR-1 or TRAF-2 in wild-type or IL-6 Tg+ mice under normal conditions. In both IL-6 Tg+ and wild-type animals, however, exposure to 100% oxygen for 72 hours led to a significant increase in both TNFR-1 and TRAF-2 (Figure 5A). To determine whether hyperoxic conditions alter the recruitment of death receptor proteins to TNFR-1 and TRAF-2, we immunoprecipitated cell lysates from IL-6 Tg+ and wild-type mice using an anti–TRAF-2 antibody. These precipitates were analyzed for expression of TNFR-1. Although no differences were observed in the interaction between TNFR-1 and TRAF-2 in IL-6 Tg+ or wild-type mice before exposure to 100% O2, a significant increase in this interaction was apparent in both IL-6 Tg+ and wild-type mice after exposure to 100% oxygen for 72 hours (Figure 5A). This increase was coincident with increased expression of TNFR-1 and TRAF-2 (Figure 5A).

JNK-mediated apoptosis is activated by oxidative stress via phosphorylation of JNK (28). As a result, the possible role of JNK in IL-6–mediated protection in hyperoxic lung injury was examined. In the absence of 100% oxygen exposure, the levels of p-JNK were significantly higher in the wild-type mice than in the IL-6 Tg+ mice. After exposure to 100% oxygen, the levels of p-JNK increased even further in the wild-type mice (Figure 5B); however, no increases of the already low levels of p-JNK in the IL-6 Tg+ mice were observed. These results suggest that IL-6–induced cell protection may be due, in part, to significant inactivation of JNK and subsequent apoptotic pathways.

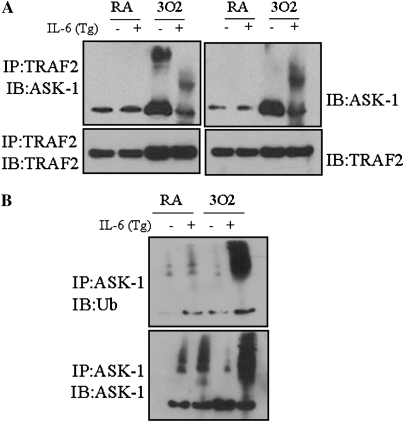

IL-6 Affects the Interaction between ASK-1 and TRAF-2, but Not between TNFR-1 and TRAF-2

Because oxidative stress is known to induce ASK-1 binding to TRAF-2, and eventual progression to apoptosis (28–30), the interaction between ASK-1 and TRAF-2 was examined in IL-6 Tg+ and wild-type mice before and after exposure to 100% oxygen. Lysates of whole-lung homogenates were immunoprecipitated using an anti–TRAF-2 antibody, and samples were analyzed by Western blotting using an anti–ASK-1 antibody. Exposure to 100% oxygen enhanced the interaction between TRAF-2 and ASK-1 in wild-type mice, but not in IL-6 Tg+ mice (Figure 6A). Immunoprecipitation of these same samples with an anti–ASK-1 antibody, followed by immunoblotting for ubiquitin, confirmed that the ASK-1 protein was indeed polyubiquitinated (Figure 6B, lane 4). In contrast, no ubiquitination of ASK-1 was detected in wild-type mice (Figure 6B, lane 3). Thus, induction of SOCS-1 in IL-6 Tg+ mice induced ASK-1 ubiquitination and degradation, and, in effect, diminished activation of the apoptotic pathway to protect cells from death.

Figure 6.

IL-6 affects the interaction between ASK-1 and TRAF-2 in CC-10/IL-6 overexpression mice under hyperoxic conditions, and IL-6 overexpression promotes ASK-1 ubiquitination and degradation under hyperoxic conditions. (A) Lung protein homogenates were extracted from mice, both before (RA) and after (3O2) exposure to 100% oxygen. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti–TRAF-2 and assessed for the interaction between ASK-1 and TRAF-2 by immunoblotting with anti–ASK-1 and anti–TRAF-2 antibodies. (B) Lung protein homogenates were immunoprecipitated with anti–ASK-1, and ubiquitination of ASK-1 was assessed by probing with an antibody to ubiquitin. Homogenates were obtained from wild-type and IL-6 Tg+ mice before (RA) and after (O2) exposure to 100% oxygen. Each panel is representative of a minimum of three similar evaluations.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we characterized the expression of SOCS-1 and the downstream ASK-1/JNK signaling pathway in vitro in SAECs with and without H2O2, and in vivo by exposing wild-type and CC10–IL-6 lung-specific transgenic mice to 100% oxygen. These studies demonstrate that SOCS-1 is an important regulator in IL-6–induced cell protection against oxidant-mediated lung injury, and that SOCS-1 functions by facilitating degradation of ASK-1 through ubiquitination. Furthermore, ASK-1 was induced by hyperoxia, and this induction was a key event in hyperoxia-induced apoptosis. The protective effects of either IL-6–induced SOCS-1 expression or SOCS-1 overexpression were associated with diminished caspase and ASK-1 activation. Lastly, no significant difference in TNFR-1/TRAF-2 activation was observed between wild-type and IL-6 Tg+ mice upon exposure to 100% oxygen, but the interaction between TRAF-2 and ASK-1 was diminished in the IL-6 Tg+ mice compared with the wild-type mice. Taken together, these studies clearly underscore the cytoprotective role of IL-6–induced endogenous SOCS-1 or overexpressed SOCS-1 during oxidative stress.

IL-6 treatment of SAECs resulted in enhanced SOCS-1 and SOCS-3 expression, as well as increased phosphorylation of STAT-3, in accord with previous reports in other cell systems (31, 32). H2O2 exposure increased the protein levels of ASK-1, p-JNK, and cleaved caspase-3 in SAECs. In contrast, the detrimental effects of H2O2, including ASK-1 and p-JNK activation, were abolished with preincubation of the cells with IL-6. Decreased levels of ASK-1 correlated with increased SOCS-1 expression in the presence of IL-6 and H2O2. Based on these results, we conclude that IL-6 suppresses the ASK-1/JNK signaling pathway via increased SOCS-1 expression.

ASK-1 undergoes ubiquitination and degradation in resting endothelial cells. Thioredoxin has been implicated in the promotion of ubiquitination and degradation of ASK-1 (15). In IL-6 Tg+ mice, ASK-1 degradation was induced. These observations are in accord with a previous study showing that phosphorylation of Jak2 and insulin receptor substrate-1/2 is a critical step in degradation of these proteins by SOCS-1 (33). In addition, TNF-α, a proinflammatory cytokine, has been shown to induce ASK-1 deubiquitination and stabilization, as well as activation. In addition, SOCS-1 functions as a negative regulator of TNF-α–induced ASK-1 activation (17). Therefore, these results clearly demonstrate that IL-6 induces SOCS-1, and that this induction is associated with a significant reduction in ASK-1 protein both in vivo and in vitro. Overexpression of both SOCS-1 and ASK-1 in SAECs promoted ASK-1 ubiquitination and degradation. Overexpression of SOCS-1, along with an ASK-1 mutant that lacks the tyrosine phosphorylation site essential for SOCS-1 binding, did not induce such degradation of ASK-1. Based on these results, we conclude that the interaction between SOCS-1 and ASK-1 is required for SOCS-1–induced ASK-1 degradation. Previous studies have demonstrated a protective role of SOCS-1 against cell death induced by TNF (7), LPS (8, 9), and IFN-γ (10, 11). Our results extend these findings by establishing SOCS-1 as a protector against oxidant-induced apoptosis via alterations in the levels of active ASK-1.

In support of these findings, previous studies have reported that some stress response pathways are regulated by ubiquitination (34). In fact, ubiquitination of IκB kinase (35) and transforming growth factor-β–activated kinase 1 (36) have been shown to regulate these proteins. Our data imply that ASK-1 is another signaling molecule regulated by cytokine-induced ubiquitination, and that degradation of ASK-1 may be an important mechanism for SOCS-1–induced protection against oxidant-induced stress. Alternatively, SOCS-1–induced ubiquitination of ASK-1 may alter cellular localization of ASK-1 or the association of ASK-1 with a signaling complex, such as TRAF-2. Further investigation into how the SOCS-1/ASK-1 interaction triggers ASK-1 ubiquitination and degradation is warranted.

TNFR signaling serves as a molecular switch for death or cell activation (37–39). TNF binding of TNFR-1 recruits TRADD and TRAF-2, and activates the ASK-1/JNK pathway. TNF binding of TNFR-2, however, activates the NF-κB cell survival pathway. In addition, oxidants activate TNFR-1 signaling by recruitment of TRADD and TRAF-2 (22, 25). TRADD interacts with TRAF-2 and Fas-associated death domain protein, and recruits both of these molecules to TNFR-1 and caspase-8 to form the DISC, which leads to apoptosis (22). Similarly, our results show that H2O2 enhanced the recruitment of TRADD and TRAF-2 to TNFR-1. Interestingly, SOCS-1 overexpression interrupted the H2O2-induced association between TRADD and caspase-8, but did not alter the H2O2-induced interaction between TNFR-1 and TRADD, or between TNFR-1 and TRAF-2. Thus, SOCS-1 interrupts oxidant-induced DISC formation by inhibiting the interaction between TRADD and caspase-8. Interestingly, SOCS-1 diminished the H2O2-induced interaction between ASK-1 and TRAF-2. This reduction may have been due to reduced levels of ASK-1 as a result of SOCS-1–induced ubiquitin-mediated degradation of ASK-1. Overall, these studies demonstrate that SOCS-1 overexpression reverses ROS-induced TRAF-2 activation of the ASK-1/JNK pathway.

These studies reveal that SOCS-1 functions as a negative regulator in ROS-induced apoptotic responses by inducing ASK-1 degradation and diminishing phosphorylation of caspases; however, the molecular mechanism by which SOCS-1 interrupts the H2O2-induced ASK-1/TRAF-2 interaction is still unclear. Additional experimentation is required to define the SOCS-1–dependent regulation of TRAF-2/ASK-1 complex under oxidative stress conditions. Although previous work has demonstrated that TRAF-2 overexpression leads to NF-κB activation (29), and that SOCS-1 exerts a potentially inhibitory effect on NF-κB activation (32), further studies are needed to elucidate the mechanism whereby SOCS-1 balances the prosurvival NF-κB pathway and the apoptotic ASK-1/TRAF-2 pathway.

To further examine the role of SOCS-1 in cytoprotection in vivo, we analyzed the TNFR/ASK-1/JNK signaling pathway in IL-6 Tg+ mice before and after exposure to 100% oxygen. These studies demonstrate that hyperoxia activates the TNFR-1 signaling pathway by recruiting both TRADD and TRAF-2, and this finding is consistent with earlier reports in rats (40). In mice, exposure to 100% oxygen induced the interaction between TRAF-2 and TNFR-1. Interestingly, IL-6 overexpression did not alter the TRAF-2/TNFR-1 interaction. On the other hand, ASK-1 was activated through TNFR-1/TRAF-2 signaling in wild-type mice exposed to 100% oxygen, but not in IL-6 Tg+ mice. Interestingly, p-JNK was selectively increased in hyperoxia-exposed wild-type mice in agreement with earlier reports (41). This increase may be due to activation of ASK-1, which phosphorylates JNK and results in synergistic apoptosis. Conversely, p-JNK protein levels were low in IL-6 Tg+ mice, as overexpression of IL-6 induced SOCS-1 expression, which stimulates ASK-1 degradation, likely due to ubiquitination (discussed above).

Another possible mechanism of IL-6–induced SOCS-1 may be via inhibition of the damaging effects of the inflammatory cytokines, IFN-γ, IL-1β, and TNF-α. Cells treated with the combination of IL-6, H2O2, and siRNA for SOCS-1 are also protected, although to a lesser, albeit statistically significant, extent than cells treated with IL-6 plus H2O2. This suggests that IL-6 may also exert its protective function through an increase in antiapoptotic proteins, such as Bcl-2 and TIMP1, as seen in IL-6 Tg+ mice (2). Finally, the protective functions of SOCS-1 may stem from inhibition of the expression of proapoptotic proteins, such as BAX. The antiapoptotic role of IL-6, which has been studied in various experimental settings, including liver regeneration and injury, involves increased expression of downstream antiapoptotic proteins, such as Bcl2 and Bcl-xl (43, 44). Thus, IL-6–induced protection may, in fact, be mediated via a number of different mechanisms, due to the complex nature and diverse functions of this cytokine.

SOCS-1 exhibits potent antiinflammatory effects (45), and thus inhibits the effects of various inflammatory cytokines that activate the Jak-STAT signaling pathway, including IFN-γ (11). Loss of SOCS-1 expression has been associated with the conversion of the antiapoptotic properties of STAT to a proapoptotic function (46). As a result, SOCS proteins have been considered as an antiinflammatory and antiapoptotic treatment (47). Based on our findings, SOCS-1 may be used in potential therapy for ALI and oxidant-mediated cell injury.

Recent studies suggest the possibility that ASK-1 inhibitors and regulators may have potential benefits in the management of acute respiratory distress syndrome (48, 49). Thioredoxin, a redox protein that protects against lung injury (50), is one such inhibitor of ASK-1 (15). The relationship between thioredoxin and SOCS-1 is not known; therefore, further investigation of a potential interaction between these two proteins and downstream regulation of ASK-1 in oxidative stress and related diseases may offer additional insight into pathogenesis and therapeutic intervention.

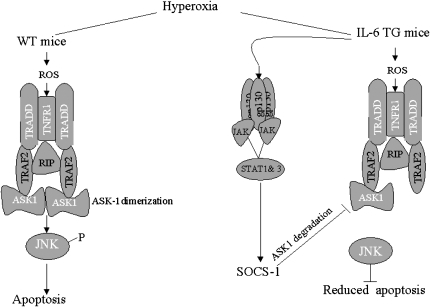

In summary, our findings indicate that the TNFR-1/TRAF-2/ASK-1 signaling pathway is activated in response to hyperoxia and oxidant-mediated stress (Figure 7). In addition, IL-6–induced SOCS-1 activation accounts, in part, for the protection against HALI and cell death. These studies are the first to demonstrate that SOCS-1 is an important regulator of oxidant-induced apoptosis. Because oxidative stress plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of many diseases (18), SOCS-1 may provide a novel therapeutic approach to treat oxidant-mediated cellular injury, such as that specifically seen in ALI. Taken together, our results suggest the intriguing possibility that regulators or inhibitors of ASK-1 and its signaling pathways may serve as potent treatment targets for HALI.

Figure 7.

Proposed scheme for regulation by SOCS-1 in IL-6–induced protection against oxidative stress–induced acute lung injury in wild-type and IL-6 Tg+ mice. In wild-type mice, hyperoxia-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) activates TNFR-1 signaling, which, in turn, recruits TRADD and TRAF-2. This step ultimately leads to ASK-1/JNK–induced apoptosis. In IL-6 Tg+ mice, ROS activates TNFR-1 signaling, which recruits TRADD and TRAF-2. IL-6–induced SOCS-1, however, degrades ASK-1, resulting in reduced apoptosis. RIP, receptor-interacting protein.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Kathryn Steiner and Stephen L. Hasak for their critical reading of this manuscript.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant RO1HL074859 (A.B.W.).

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0287OC on September 5, 2008

Conflict of Interest Statement: None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Waxman AB, Einarsson O, Seres T, Knickelbein RG, Warshaw JB, Johnston R, Homer RJ, Elias JA. Targeted lung expression of interleukin-11 enhances murine tolerance of 100% oxygen and diminishes hyperoxia-induced DNA fragmentation. J Clin Invest 1998;101:1970–1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ward NS, Waxman AB, Homer RJ, Mantell LL, Einarsson O, Du Y, Elias JA. Interleukin-6–induced protection in hyperoxic acute lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2000;22:535–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White CW, Ghezzi P, Dinarello CA, Caldwell SA, McMurtry IF, Repine JE. Recombinant tumor necrosis factor/cachectin and interleukin 1 pretreatment decreases lung oxidized glutathione accumulation, lung injury, and mortality in rats exposed to hyperoxia. J Clin Invest 1987;79:1868–1873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsan MF, White JE, Santana TA, Lee CY. Tracheal insufflation of tumor necrosis factor protects rats against oxygen toxicity. J Appl Physiol 1990;68:1211–1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Croker BA, Krebs DL, Zhang JG, Wormald S, Willson TA, Stanley EG, Robb L, Greenhalgh CJ, Forster I, Clausen BE, et al. SOCS3 negatively regulates IL-6 signaling in vivo. Nat Immunol 2003;4:540–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lang R, Pauleau AL, Parganas E, Takahashi Y, Mages J, Ihle JN, Rutschman R, Murray PJ. SOCS3 regulates the plasticity of gp130 signaling. Nat Immunol 2003;4:546–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morita Y, Naka T, Kawazoe Y, Fujimoto M, Narazaki M, Nakagawa R, Fukuyama H, Nagata S, Kishimoto T. Signals transducers and activators of transcription (STAT)–induced STAT inhibitor-1 (SSI-1)/suppressor of cytokine signaling-1 (SOCS-1) suppresses tumor necrosis factor α–induced cell death in fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000;97:5405–5410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kinjyo I, Hanada T, Inagaki-Ohara K, Mori H, Aki D, Ohishi M, Yoshida H, Kubo M, Yoshimura A. SOCS1/JAB is a negative regulator of LPS-induced macrophage activation. Immunity 2002;17:583–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakagawa R, Naka T, Tsutsui H, Fujimoto M, Kimura A, Abe T, Seki E, Sato S, Takeuchi O, Takeda K, et al. SOCS-1 participates in negative regulation of LPS responses. Immunity 2002;17:677–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marine JC, Topham DJ, McKay C, Wang D, Parganas E, Stravopodis D, Yoshimura A, Ihle JN. SOCS1 deficiency causes a lymphocyte-dependent perinatal lethality. Cell 1999;98:609–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alexander WS, Starr R, Fenner JE, Scott CL, Handman E, Sprigg NS, Corbin JE, Cornish AL, Darwiche R, Owczarek CM, et al. SOCS1 is a critical inhibitor of IFN-γ signaling and prevents the potentially fatal neonatal actions of this cytokine. Cell 1999;98:597–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ichijo H, Nishida E, Irie K, ten Dijke P, Saitoh M, Moriguchi T, Takagi M, Matsumoto K, Miyazono K, Gotoh Y. Induction of apoptosis by ASK1, a mammalian MAPKKK that activates SAPK/JNK and p38 signaling pathways. Science 1997;275:90–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamawaki H, Pan S, Lee RT, Berk BC. Fluid shear stress inhibits vascular inflammation by decreasing thioredoxin-interacting protein in endothelial cells. J Clin Invest 2005;115:733–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Y, Yin G, Surapisitchat J, Berk BC, Min W. Laminar flow inhibits TNF-induced ASK1 activation by preventing dissociation of ASK1 from its inhibitor 14–3-3. J Clin Invest 2001;107:917–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Y, Min W. Thioredoxin promotes ASK1 ubiquitination and degradation to inhibit ASK1-mediated apoptosis in a redox activity–independent manner. Circ Res 2002;90:1259–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tobiume K, Matsuzawa A, Takahashi T, Nishitoh H, Morita K, Takeda K, Minowa O, Miyazono K, Noda T, Ichijo H. ASK1 is required for sustained activations of JNK/p38 MAP kinases and apoptosis. EMBO Rep 2001;2:222–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He Y, Zhang W, Zhang R, Zhang H, Min W. SOCS1 inhibits tumor necrosis factor–induced activation of ASK1-JNK inflammatory signaling by mediating ASK1 degradation. J Biol Chem 2006;281:5559–5566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He CH, Waxman AB, Lee CG, Link H, Rabach ME, Ma B, Chen Q, Zhu Z, Zhong M, Nakayama K, et al. Bcl-2–related protein A1 is an endogenous and cytokine-stimulated mediator of cytoprotection in hyperoxic acute lung injury. J Clin Invest 2005;115:1039–1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corne J, Chupp G, Lee CG, Homer RJ, Zhu Z, Chen Q, Ma B, Du Y, Roux F, McArdle J, et al. IL-13 stimulates vascular endothelial cell growth factor and protects against hyperoxic acute lung injury. J Clin Invest 2000;106:783–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barker GF, Manzo ND, Cotich KL, Shone RK, Waxman AB. DNA damage induced by hyperoxia: quantitation and correlation with lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2006;35:277–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waxman AB, Mahboubi K, Knickelbein RG, Mantell LL, Manzo N, Pober JS, Elias JA. Interleukin-11 and interleukin-6 protect cultured human endothelial cells from H2O2-induced cell death. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2003;29:513–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pantano C, Shrivastava P, McElhinney B, Janssen-Heininger Y. Hydrogen peroxide signaling through tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 leads to selective activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase. J Biol Chem 2003;278:44091–44096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yasukawa H, Ohishi M, Mori H, Murakami M, Chinen T, Aki D, Hanada T, Takeda K, Akira S, Hoshijima M, et al. IL-6 induces an anti-inflammatory response in the absence of SOCS3 in macrophages. Nat Immunol 2003;4:551–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Starr R, Willson TA, Viney EM, Murray LJ, Rayner JR, Jenkins BJ, Gonda TJ, Alexander WS, Metcalf D, Nicola NA, et al. A family of cytokine-inducible inhibitors of signalling. Nature 1997;387:917–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsu H, Shu HB, Pan MG, Goeddel DV. TRADD–TRAF2 and TRADD–FADD interactions define two distinct TNF receptor 1 signal transduction pathways. Cell 1996;84:299–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gotoh Y, Cooper JA. Reactive oxygen species- and dimerization-induced activation of apoptosis signal–regulating kinase 1 in tumor necrosis factor-α signal transduction. J Biol Chem 1998;273:17477–17482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hino T, Nakamura H, Abe S, Saito H, Inage M, Terashita K, Kato S, Tomoike H. Hydrogen peroxide enhances shedding of type I soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor from pulmonary epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1999;20:122–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nishitoh H, Saitoh M, Mochida Y, Takeda K, Nakano H, Rothe M, Miyazono K, Ichijo H. ASK1 is essential for JNK/SAPK activation by TRAF2. Mol Cell 1998;2:389–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu H, Nishitoh H, Ichijo H, Kyriakis JM. Activation of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) by tumor necrosis factor receptor–associated factor 2 requires prior dissociation of the ASK1 inhibitor thioredoxin. Mol Cell Biol 2000;20:2198–2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nishitoh H, Matsuzawa A, Tobiume K, Saegusa K, Takeda K, Inoue K, Hori S, Kakizuka A, Ichijo H. ASK1 is essential for endoplasmic reticulum stress–induced neuronal cell death triggered by expanded polyglutamine repeats. Genes Dev 2002;16:1345–1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang JG, Farley A, Nicholson SE, Willson TA, Zugaro LM, Simpson RJ, Moritz RL, Cary D, Richardson R, Hausmann G, et al. The conserved SOCS box motif in suppressors of cytokine signaling binds to elongins B and C and may couple bound proteins to proteasomal degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999;96:2071–2076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnston JA, O'Shea JJ. Matching SOCS with function. Nat Immunol 2003;4:507–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rui L, Yuan M, Frantz D, Shoelson S, White MF. SOCS-1 and SOCS-3 block insulin signaling by ubiquitin-mediated degradation of IRS1 and IRS2. J Biol Chem 2002;277:42394–42398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laney JD, Hochstrasser M. Substrate targeting in the ubiquitin system. Cell 1999;97:427–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deng L, Wang C, Spencer E, Yang L, Braun A, You J, Slaughter C, Pickart C, Chen ZJ. Activation of the IκB kinase complex by TRAF6 requires a dimeric ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme complex and a unique polyubiquitin chain. Cell 2000;103:351–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang C, Deng L, Hong M, Akkaraju GR, Inoue J, Chen ZJ. TAK1 is a ubiquitin-dependent kinase of MKK and IKK. Nature 2001;412:346–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pimentel-Muinos FX, Seed B. Regulated commitment of TNF receptor signaling: a molecular switch for death or activation. Immunity 1999;11:783–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rothe M, Wong SC, Henzel WJ, Goeddel DV. A novel family of putative signal transducers associated with the cytoplasmic domain of the 75 kDa tumor necrosis factor receptor. Cell 1994;78:681–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith CA, Farrah T, Goodwin RG. The TNF receptor superfamily of cellular and viral proteins: activation, costimulation, and death. Cell 1994;76:959–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guthmann F, Wissel H, Schachtrup C, Tolle A, Rudiger M, Spener F, Rustow B. Inhibition of TNFα in vivo prevents hyperoxia-mediated activation of caspase 3 in type II cells. Respir Res 2005;6:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang G, Abate A, George AG, Weng YH, Dennery PA. Maturational differences in lung NF-κB activation and their role in tolerance to hyperoxia. J Clin Invest 2004;114:669–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Naka T, Matsumoto T, Narazaki M, Fujimoto M, Morita Y, Ohsawa Y, Saito H, Nagasawa T, Uchiyama Y, Kishimoto T. Accelerated apoptosis of lymphocytes by augmented induction of Bax in SSI-1 (STAT-induced STAT inhibitor-1) deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998;95:15577–15582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haga S, Terui K, Zhang HQ, Enosawa S, Ogawa W, Inoue H, Okuyama T, Takeda K, Akira S, Ogino T, et al. Stat3 protects against Fas-induced liver injury by redox-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J Clin Invest 2003;112:989–998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kovalovich K, Li W, DeAngelis R, Greenbaum LE, Ciliberto G, Taub R. Interleukin-6 protects against Fas-mediated death by establishing a critical level of anti-apoptotic hepatic proteins FLIP, Bcl-2, and Bcl-xL. J Biol Chem 2001;276:26605–26613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Egan PJ, Lawlor KE, Alexander WS, Wicks IP. Suppressor of cytokine signaling-1 regulates acute inflammatory arthritis and T cell activation. J Clin Invest 2003;111:915–924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lu Y, Fukuyama S, Yoshida R, Kobayashi T, Saeki K, Shiraishi H, Yoshimura A, Takaesu G. Loss of SOCS3 gene expression converts STAT3 function from anti-apoptotic to pro-apoptotic. J Biol Chem 2006;281:36683–36690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jo D, Liu D, Yao S, Collins RD, Hawiger J. Intracellular protein therapy with SOCS3 inhibits inflammation and apoptosis. Nat Med 2005;11:892–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li X, Shu R, Filippatos G, Uhal BD. Apoptosis in lung injury and remodeling. J Appl Physiol 2004;97:1535–1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dudek SM, Birukov KG. Apoptosis in ventilator-induced lung injury: more questions to ASK? Crit Care Med 2005;33:2118–2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tran PL, Weinbach J, Opolon P, Linares-Cruz G, Reynes JP, Gregoire A, Kremer E, Durand H, Perricaudet M. Prevention of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis after adenovirus-mediated transfer of the bacterial bleomycin resistance gene. J Clin Invest 1997;99:608–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.