Abstract

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) play a crucial role in ischemia-reperfusion (IR) injury after lung transplantation. We hypothesized that NADPH oxidase derived from bone marrow (BM) cells contributes importantly to lung IR injury. An in vivo mouse model of lung IR injury was employed. Wild-type C57BL/6 (WT) mice, p47phox knockout (p47phox−/−) mice, or chimeras created by BM transplantation between WT and p47phox−/− mice were assigned to either Sham (left thoracotomy) or six study groups that underwent IR (1 h left hilar occlusion and 2 h reperfusion). After reperfusion, pulmonary function was assessed using an isolated, buffer-perfused lung system. Lung injury was assessed by measuring vascular permeability (via Evans blue dye), edema, neutrophil infiltration (via myeloperoxidase [MPO]), lipid peroxidation (via malondialdyhyde [MDA]), and expression of proinflammatory cytokines. Lung IR resulted in significantly increased MDA in WT mice, indicative of oxidative stress. WT mice treated with apocynin (an NADPH oxidase inhibitor) and p47phox−/− mice displayed significantly reduced pulmonary dysfunction and injury (vascular permeability, edema, MPO, and MDA). In BM chimeras, significantly reduced pulmonary dysfunction and injury occurred after IR in p47phox−/−→WT chimeras (donor→recipient) but not WT→p47phox−/− chimeras. Induction of TNF-α, IL-17, IL-6, RANTES (CCL5), KC (CXCL1), MIP-2 (CXCL2), and MCP-1 (CCL2) was significantly reduced after IR in NADPH oxidase–deficient mice and p47phox−/−→WT chimeras but not WT→p47phox−/− chimeras. These results indicate that NADPH oxidase–generated ROS specifically from BM-derived cells contributes importantly to lung IR injury. NADPH oxidase may represent a novel therapeutic target for the treatment of IR injury after lung transplantation.

Keywords: NADPH oxidase, lung ischemia-reperfusion injury, bone marrow transplant, reactive oxygen species

CLINICAL RELEVANCE

This study shows that NADPH oxidase–generated reactive oxygen species from bone marrow–derived cells initiates lung reperfusion injury. NADPH oxidase may be a novel therapeutic target for the treatment of reperfusion injury after lung transplantation.

Ischemia-reperfusion (IR) injury is a major cause of morbidity and mortality after lung transplantation (1, 2). Lung IR injury is associated with not only short-term but also long-term complications (3–5). Mechanisms underlying lung IR injury remain unclear, and effective treatments for prevention are lacking. Lung IR injury is associated with enhanced inflammatory responses, including formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (6–8), leukocyte activation (9), endothelial cell injury, increased vascular permeability, and complement activation (10).

Multiple lines of evidence suggest that ROS play a crucial role in the process of lung IR injury. Antioxidant therapy has shown promising results in reducing IR injury (6, 11–13). There are multiple potential enzymatic sources of ROS after IR, including nitric oxide synthase (NOS), NADPH oxidase, and xanthine oxidase. The mitochondrial respiratory chain is another potential source of oxidative stress in this setting. Although not fully understood, evidence is mounting to suggest that NADPH oxidase plays a predominant role in mediating oxidative stress during IR (6, 12–16). However, the primary cellular sources of NADPH oxidase contributing to lung IR injury remain undefined.

NADPH oxidase is ubiquitously distributed and is a unique family of enzymes whose physiologic function is the generation of ROS (17). During lung IR, likely cellular sources of NADPH oxidase–derived ROS are leukocytes, endothelial cells, epithelial cells, and dendritic cells. Hypoxia- or ischemia-induced ROS production is reportedly derived from pulmonary epithelial (18) or endothelial (6) NADPH oxidase. Although IR-induced ROS derives from multiple cellular sources, activation of NADPH oxidase in leukocytes during reperfusion also appears important in mediating lung IR injury (6, 12, 13). In the current study, p47phox−/− mice, which are deficient in the p47phox subunit of NADPH oxidase, and apocynin, a specific NADPH oxidase inhibitor, were used to demonstrate that NADPH oxidase contributes importantly to lung IR injury. Through the use of bone marrow (BM) chimeras, the role of BM- versus non–BM-derived NADPH oxidase in mediating lung IR injury was clarified.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

This study used adult (10- to 14-wk-old) male C57BL/6 wild-type (WT) mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) and p47phox−/− mice (C57BL/6J-Ncf1m1J/J; Jackson Laboratory). p47phox−/− mice, which are on a C57BL/6 background that is identical to the WT mice, are deficient in the p47phox subunit of NADPH oxidase, thus leading to inactivation of NADPH oxidase–generated ROS. Mice were assigned to six study groups that underwent left lung IR and one sham group that underwent left thoracotomy. Apocynin (10 mg/kg; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was administered via intravenous injection 5 minutes before the start of reperfusion. This study conformed to the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” published by the National Institute of Health (NIH publication No. 85-23, revised 1985) and was conducted under protocols approved by the University of Virginia's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

In Vivo Model of Lung IR

Mice were anesthetized with inhalation isoflurane, intubated with PE-60 tubing and connected to a pressure-controlled ventilator (Harvard Apparatus Co., South Natick, MA). Mechanical ventilation was performed with room air as adjusted to a rate of 120 strokes/minute, a stroke volume of 1.0 cc, and peak inspiratory pressure less than 20 cm H2O. Heparin (20 U/kg) was administered via external jugular injection. Left thoracotomy was performed by cutting the left fourth rib, and the left hilum was exposed. A 6-0 prolene suture was placed around the hilum facilitated by a tip-curved (22-G) gavage needle. Both ends of the suture were then threaded through a 5-mm-long PE-50 tubing. Occlusion was achieved by pulling up on the suture and thus pressing the tube against the hilum to initiate ischemia. A small surgical clip was applied to the suture at the end of the tube to maintain tension of the tube against the hilum. The thoracotomy was then suture-closed, and the mouse was extubated, returned to its cage, and allowed to awaken during the 1-hour hilar occlusion (ischemic) period. Animals were kept warm in the cage by using a heat lamp. The average time on the ventilator for this stage was 10 minutes for each animal. Five minutes before reperfusion, the mouse was re-anesthetized and re-intubated. Reperfusion was achieved by removing the clip, tube, and suture. Again, the chest was suture-closed, and the average time on the ventilator for this stage was 4 minutes. The mouse was extubated and returned to its cage until the end of the reperfusion period. Temperature was monitored during surgery using an anal probe and maintained at 36.5 to 37.5°C. Sham animals received a thoracotomy only without hilar occlusion.

Chimeric Mice Created by BM Transplantation

BM chimeras were produced using standard techniques as described previously (19). Briefly, donor mice (24–26 g, age 8–10 wk) were anesthetized with Nembutal (0.02 mg/g) and killed by cervical dislocation. BM from the tibia and femur was harvested under sterile conditions, yielding approximately 50 million nucleated BM cells per mouse. Recipient mice (22–25 g, age 6 wk) were irradiated with two doses of 6.00 Gy each 4 hours apart. Immediately after irradiation, 2 to 4 × 106 BM cells were injected intravenously via the tail vein under inhalational anesthesia with isoflurane. Two control mice did not receive BM transplant after the irradiations. Irradiated/transplanted mice were housed in microisolator cages for 8 to 9 weeks before experimentation. Three different chimeras were created and presented as WT→WT (BM donor→recipient), p47phox−/−→WT, and WT→p47phox−/−.

Measurement of Pulmonary Function

At the end of the scheduled reperfusion period, pulmonary function was evaluated using an isolated, buffer-perfused mouse lung system (Hugo Sachs Elektronik, March-Huggstetten, Germany) as previously described by our laboratory (20). Briefly, mice were anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine. A tracheostomy was performed, and animals were ventilated with room air at 100 strokes/minute, a tidal volume of 7 μl/g body weight with a positive end-expiratory pressure of 2 cm H2O. The animals were exsanguinated by inferior caval transection. The pulmonary artery was cannulated via the right ventricle, and the left ventricle was immediately tube-vented through a small incision at the apex of the heart. The lungs were then perfused at a constant flow of 60 μl·g body wt−1·min−1 with Krebs-Henseleit buffer containing 2% albumin, 0.1% glucose, and 0.3% HEPES (335–340 mosmol/kg H2O). The perfusate buffer and isolated lungs were maintained at 37°C throughout the experiment by use of a circulating water bath. Once properly perfused and ventilated, the lungs were maintained on the system for a 5-minute equilibration period before data were recorded for an additional 10 minutes. Hemodynamic and pulmonary parameters were continuously recorded during this period by the PULMODYN data acquisition system (Hugo Sachs Elektronik).

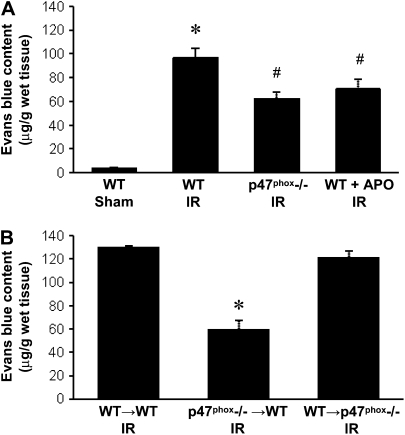

The assessment of lung function using the isolated, buffer-perfused lung system necessarily includes both right and left lungs (i.e., the left lung is not isolated). Thus the measurements of lung function actually reflect “total lung function,” and this is a limitation of the model. Isolation and perfusion of only the left lung results in induction of unacceptable (possibly ventilator-induced) injury, probably because of the small size of the left lung. In spite of this limitation, we have clearly demonstrated significantly impaired lung function after left lung IR versus Sham (see Figure 5) and are confident that any lung function deficiencies measured in this model are reflective of left lung injury.

Figure 5.

Pulmonary function after reperfusion. (A–C) Pulmonary function in WT Sham mice and after IR in WT, p47phox−/−, and APO-treated WT mice. (D–F) Pulmonary function after IR in BM chimeras (donor→recipient). Airway resistance (A and D), lung compliance (B and E), and pulmonary artery pressure (C and F) were measured. *P < 0.05 versus WT Sham, #P < 0.05 versus WT IR, §P < 0.05 versus WT→WT IR (n = 7–9/group).

Bronchoalveolar Lavage

After pulmonary function measurements, the left lungs were lavaged with 0.4 ml normal saline. A microclamp was used to occlude the right hilum before lavage. The bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid was immediately centrifuged at 4°C (500 × g, 5 min), and the supernatant was stored at −80°C until further analysis.

Lung Wet/Dry Weight Ratio

Using separate groups of animals, the left lung was harvested after reperfusion, weighed, and then placed in a vacuum oven (at 54°C) until a stable dry weight was achieved. The ratio of lung wet weight to dry weight was then calculated as an indicator of pulmonary edema.

Pulmonary Microvascular Permeability

Using separate groups of animals, microvascular permeability in the left lung was determined using the Evans blue dye extravasation technique (21). Evans blue (20 mg/kg; Sigma-Aldrich) was injected intravenously 30 minutes before the end of scheduled reperfusion. The pulmonary vasculature was then perfused with PBS for 10 minutes to remove intravascular dye. Lungs were then homogenized in PBS to extract the Evans blue and centrifuged. The absorption of Evans blue was measured in the supernatant at 620 nm and corrected for the presence of heme pigments: A620 (corrected) = A620 - (1.426 × A740 + 0.030). The concentration of Evans blue was determined according to a standard curve and expressed as μg/gram wet lung weight.

Measurement of Malondialdehyde

Malondialdehyde (MDA) was measured in BAL fluid using a commercially available assay kit (Oxis International, Inc., Foster City, CA) which is a spectrophotometric assay which measures free MDA.

Measurement of Myeloperoxidase

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) was measured in BAL fluid using a mouse MPO ELISA kit (Cell Sciences, Canton, MA).

Measurement of Cytokines and Chemokines

Cytokines and chemokines in BAL fluid were quantified using the Bioplex Bead Array technique with a multiplex cytokine panel assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) as previously performed by our laboratory (22). The samples were analyzed as instructed using the Bioplex array reader, which is a fluorescent-based flow cytometer employing a bead-based multiplex technology, each of which is conjugated with a reactant specific for a different target molecule.

Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Data were compared using one-way ANOVA followed by the Student's t test for unpaired data with Bonferroni correction.

RESULTS

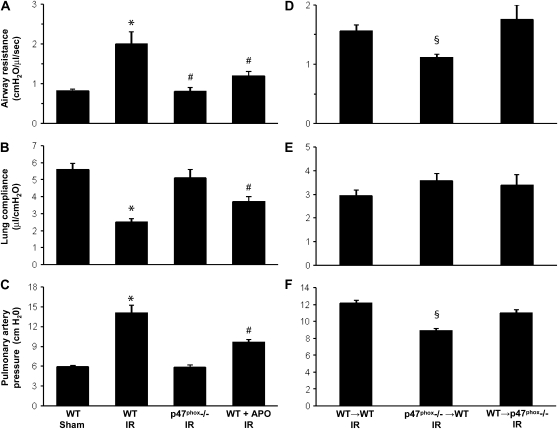

Lipid Peroxidation after IR Is Due to NADPH Oxidase Activation

Levels of MDA, an indicator of lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress, were measured in BAL fluid of left lungs. Four groups of mice (n = 4/group) underwent sham thoracotomy or IR (1 h left hilar ligation followed by 2 h reperfusion). In WT mice, MDA was significantly increased after IR compared with Sham (Figure 1A). MDA in p47phox−/− mice after IR was significantly lower than in WT IR mice and comparable to that in WT Sham (P < 0.05). Treatment of WT mice with apocynin (10 mg/kg), an NADPH inhibitor, 5 minutes before reperfusion significantly reduced MDA to levels comparable to those in p47phox−/− mice and WT Sham (Figure 1A). In BM chimeras after IR (n = 4/group), MDA was significantly reduced in p47phox−/−→WT chimeras compared with WT→WT chimeras (Figure 1B). MDA was not reduced in WT→p47phox−/− chimeras.

Figure 1.

Malondialdyhyde (MDA) level in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid after reperfusion. (A) MDA level in WT, p47phox−/−, and apocynin (APO)-treated wild-type (WT) mice after ischemia-reperfusion injury (IR) compared with WT Sham animals. (B) MDA level in BM chimeras (donor→recipient) after IR. *P < 0.05 versus WT Sham, #P < 0.05 versus WT IR (n = 4/group).

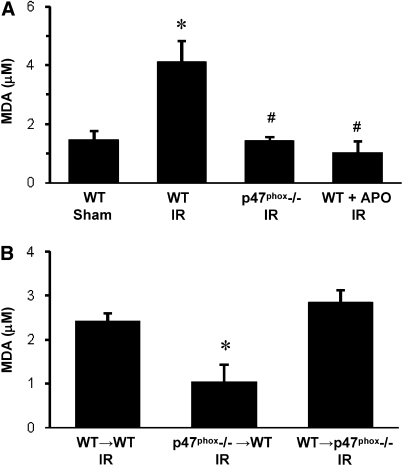

NADPH Oxidase Activity Contributes to Pulmonary Microvascular Permeability after IR

Evans blue content in left lung tissue was measured in each group (n = 4/group) to assess pulmonary microvascular leak. As expected, there was significantly higher Evans blue content in WT mice after IR versus Sham (Figure 2A). Evans blue content was partially but significantly reduced after IR in both p47phox−/− mice and apocynin-treated WT mice (Figure 2A). In BM chimeras after IR (n = 4/group), Evans blue content in WT→p47phox−/− chimeras remained elevated as in WT→WT; however, Evans blue content was significantly decreased in p47phox−/−→WT chimeras (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Microvascular permeability measured by Evans blue content in lung tissue. (A) Evans blue content in WT, p47phox−/−, and APO-treated WT mice after IR compared with WT Sham animals. (B) Evans blue content in BM chimeras (donor→recipient) after IR. *P < 0.05 versus all groups, #P < 0.05 versus WT Sham (n = 4/group).

NADPH Oxidase Activity Leads to Pulmonary Edema after IR

Lung wet/dry weight ratio was assessed as an indicator of edema (n = 4/group). Wet/dry weight was significantly increased in WT mice after IR versus Sham (Figure 3A). Importantly, wet/dry weight was not significantly elevated after IR in p47phox−/− mice or in apocynin-treated WT mice compared with WT Sham (Figure 3A). In BM chimeras (n = 4/group), lung wet/dry weight was significantly reduced in p47phox−/−→WT chimeras after IR when compared with WT→WT and WT→p47phox−/− chimeras (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Pulmonary edema measured by wet/dry weight ratio. (A) Wet/dry weight in WT, p47phox−/−, and APO-treated WT mice after IR compared with WT Sham animals. (B) Wet/dry weight in BM chimeras (donor→recipient) after IR. *P < 0.05 versus WT Sham, #P < 0.05 versus WT IR (n = 4/group).

Neutrophil Infiltration Requires NADPH Oxidase Activity after IR

MPO levels were measured in BAL fluid as an indicator of neutrophil infiltration into alveolar airspace (n = 4/group). MPO was significantly increased in WT mice after IR versus Sham (Figure 4A). MPO was significantly decreased after IR in p47phox−/− mice or in apocynin-treated WT mice compared with WT IR (Figure 4A). In BM chimeras after IR (n = 4/group), MPO was significantly reduced in p47phox−/−→WT chimeras but not in WT→p47phox−/− compared with WT→WT (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) level in BAL fluid after reperfusion as an indicator of neutrophil infiltration. (A) MPO in WT, p47phox−/−, and APO-treated WT mice after IR compared with WT Sham animals. (B) MPO in BM chimeras (donor→recipient) after IR. *P < 0.05 versus WT Sham, #P < 0.05 versus WT IR (n = 4/group).

Pulmonary Function Is Improved after IR by Inhibition of NADPH Oxidase

Pulmonary function, evaluated by measuring airway resistance (AR), lung compliance (LC), and pulmonary artery pressure (PAP) after reperfusion, was measured for each group (n = 7–9/group). Pulmonary function was significantly impaired after IR in WT mice, and lung function was significantly improved in p47phox−/− mice after IR to levels similar to those in Sham (Figures 5A–5C). In apocynin-treated WT mice, AR, LC, and PAP were all partially and significantly improved compared with WT mice after IR (Figures 5A–5C). In BM chimeras after IR (n = 7–9/group), AR and PAP were significantly reduced in p47phox−/−→WT chimeras versus WT→WT (Figures 5D and 5F). There was no significant difference in LC among the chimeric groups (Figure 5E).

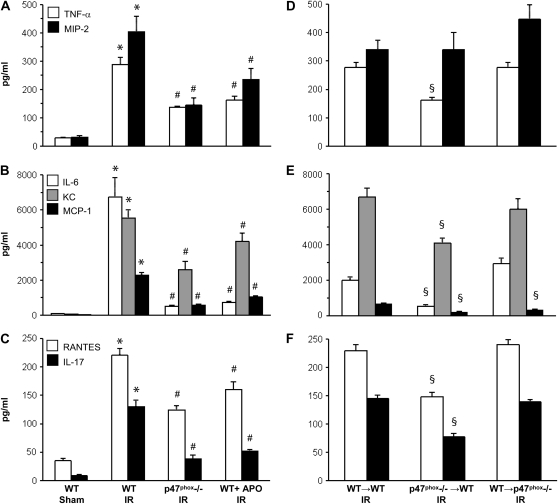

Proinflammatory Cytokine/Chemokine Production after IR

The following panel of eight proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines were measured in BAL fluid after reperfusion (n = 5/group): TNF-α, MIP-2 (CXCL2), IL-6, KC (CXCL1), MCP-1 (CCL2), RANTES (CCL5), IL-17, and IFN-γ. After IR, all but IFN-γ were significantly induced in WT IR mice compared with WT Sham (Figures 6A–6C). IFN-γ was not measurably induced after IR in any group compared with Sham (data not shown). The induction of TNF-α, MIP-2, IL-6, KC, MCP-1, RANTES, and IL-17 after IR were significantly reduced in both p47phox−/− mice and WT mice treated with apocynin compared with WT IR (Figures 6A–6C). In BM chimeras after IR (n = 5/group), the expression of TNF-α, IL-6, KC, MCP-1, RANTES, and IL-17 remained elevated in WT→p47phox−/− chimeras but were significantly reduced in p47phox−/−→WT chimeras compared with WT→WT (Figures 6D–6F). The induction of MIP-2 was not reduced in p47phox−/−→WT or WT→p47phox−/− chimeras, and the induction of MCP-1 was also significantly reduced in WT→p47phox−/− chimeras after IR.

Figure 6.

Cytokine/chemokine measurements in BAL fluid after reperfusion. (A–C) Cytokines/chemokines in WT Sham mice and after IR in WT, p47phox−/−, and APO-treated WT mice. (D–F) Cytokines/chemokines after IR in BM chimeras (donor→recipient). The following cytokines/chemokines were measured in BAL fluid: TNF-α and MIP-2 (CXCL2) (A, D); IL-6, KC (CXCL1), and MCP-1 (CCL2) (B, E); RANTES (CCL5) and IL-17 (C, F). *P = 0.001 versus WT Sham, #P = 0.001 versus WT IR, §P = 0.002 versus WT→WT IR (n = 5/group).

DISCUSSION

By using a selective NADPH oxidase inhibitor (apocynin), p47phox−/− mice, and BM chimeric mice, we have identified BM-derived cells as the cells primarily responsible for lung IR injury via production of ROS through the NADPH oxidase-dependent pathway. In WT mice, lung IR induced significant oxidative stress as indicated by elevated MDA levels, which in the end resulted in pulmonary injury and dysfunction. Although there were no direct measurements of NADPH oxidase activation performed in this study, by using the specific NADPH oxidase inhibitor and mutant mice deficient in NADPH oxidase activity, we demonstrated that NADPH oxidase contributes importantly to the oxidative stress during lung IR and is a critical mediator in the pathogenesis of lung IR injury. The conclusion was further confirmed in BM chimeras where NADPH oxidase was rendered inactive in either BM-derived cells (p47phox−/−→WT chimeras) or in non–BM-derived cells such as endothelial and parenchymal cells (WT→p47phox−/− chimeras). The results indicate that NADPH oxidase activity in BM-derived cells is critical for mediating lung IR injury.

Compelling evidence has shown that inflammatory responses mediate lung IR injury (9, 22–24). ROS have been suggested to be a critical component of this inflammatory response possibly as both a mediator and an end effector. Antioxidant therapy has been shown to be effective in reducing lung IR injury (6, 11). An increasing body of evidence suggests that NADPH oxidase plays a critical role in mediating oxidative stress during IR injury. However, the relevant cellular sources of NADPH oxidase during lung IR remain controversial (6, 12, 13). NADPH oxidase is widely distributed in both parenchymal cells (including endothelium and epithelium) and hematopoietic cells (6, 11–13, 17). Apocynin has been shown to have protective effects against lung IR injury, perhaps by inhibiting leukocyte NADPH oxidase (12, 13). However, observations by Heumüller and coworkers indicate that apocynin predominantly acts as an antioxidant in endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells by serving as a scavenger of radicals and directly inhibiting the ROS-induced signaling in vascular cells (25). This action likely requires activation by MPO and/or H2O2 to be effective (25). For this reason, the inhibitory action of apocynin for NADPH oxidase is restricted to MPO-expressing leukocytes (25, 26), and the use of apocynin in the current study likely highlights the importance of leukocyte-derived NADPH oxidase in lung IR injury. Alveolar epithelial cells are also involved in the oxidative stress response after IR (18) and apocynin is also reported to inhibit epithelial-derived ROS (26).

In light of the above information and although NADPH oxidase activity was never directly measured after administration of apocynin, the current study clearly demonstrates that NADPH oxidase plays a critical role in lung IR injury by using p47phox−/− mice. Thus, the interpretation of the conclusions of the current study cannot be based upon the use of apocynin alone, but must be evaluated by the combined results obtained with both the use of apocynin as well as the p47phox−/− mice. BM-derived cells from p47phox−/− mice fail to produce ROS (27). As a subunit of NADPH oxidase, p47phox is also present in the endothelium; however, its function is not fully understood, especially in the process of lung IR injury (6). Apocynin inhibits NADPH oxidase by acting as an irreversible inhibitor of the p47phox subunit. It prevents the translocation of cytosolic p47phox to Nox2 in the membrane of leukocytes, monocytes, and endothelial cells (25, 26, 28, 29).

We found that apocynin applied 5 minutes before reperfusion totally abolished the oxidative stress in terms of MDA levels observed in WT IR mice. In addition, p47phox−/− mice displayed significantly reduced MDA that was comparable to that of Sham (Figure 1A). Correspondingly, p47phox−/− mice and apocynin-treated WT mice had significantly improved pulmonary function and less parenchymal injury. In this study, p47phox−/− mice demonstrated slightly better pulmonary function (Figure 5) and a slightly greater decrease in cytokine/chemokine production (Figure 6) than apocynin-treated WT mice, which could not be explained by other injury parameters. This could be due to several explanations. First, apocynin could have had less than 100% pharmacologic efficacy at the dose used in this study. Second, apocynin was administered shortly before the onset of reperfusion and thus the inhibition of NADPH oxidase occurred only during reperfusion and not during ischemia. Third, as mentioned above, the inhibitory actions of apocynin may be most effective in leukocytes and may not inhibit vascular NADPH oxidase-generated ROS production (25, 30). In the p47phox−/− mice, NADPH oxidase was deficient not only during reperfusion but also during ischemia, which could contribute to the better protection in p47phox−/− mice than in apocynin-treated mice. These results clearly defined the role of NADPH oxidase in mediating IR-induced oxidative stress and lung injury. However, the identity of the cell type(s) responsible for mediating the oxidative stress could not be answered by the results obtained with p47phox−/− mice and apocynin treatment. For this purpose, BM chimeric mice were used.

We used BM transplantation technique for the creation of chimeric mice. All irradiated control mice that did not undergo BM transplant died within 2 weeks of irradiation, indicative of effective BM cell depletion by irradiation. Our previous studies showed that in BM chimeras, 98% of CD11b+ cells, 84% of CD4+ cells, and 85% of CD8+ cells are derived from donor mice (31). Eight weeks after BM transplant, peripheral blood analysis of the numbers of red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets in chimeric mice were comparable to pre-irradiation levels. No donor BM cells engrafted into the endothelium of recipient mice (19, 31). Thus, in p47phox−/−→WT chimeras, the BM-derived cell lineages (but not endothelial or epithelial cells) are replaced by cells derived from donor p47phox−/− mouse BM, which are deficient in NADPH oxidase. In the WT→p47phox−/− chimeras, only BM-derived cell lineages (not endothelial or epithelial cells) contain active NADPH oxidase, thus enabling us to investigate the role of NADPH oxidase in BM-derived cells versus non–BM-derived cells (i.e., endothelia, epithelia, and others) without interference from each other.

The results showed that IR-induced oxidative stress was significantly reduced in p47phox−/−→WT chimeras compared with WT→WT, but not in WT→p47phox−/− chimeras (Figure 1B), indicating that IR-induced oxidative stress is highly associated with active NADPH oxidase in BM-derived cells but not with that in endothelial or epithelial cells. Lung IR injury (microvascular permeability, edema, and neutrophil infiltration) was also significantly ameliorated in p47phox−/−→WT chimeras but not WT→p47phox−/− chimeras. Pulmonary function was also better preserved in p47phox−/−→WT chimeras. Taken together, these results demonstrate that NADPH oxidase is activated during IR and contributes importantly to lung dysfunction and injury. In contrast to endothelial and epithelial cells, NADPH oxidase in BM-derived cells plays the major role in mediating lung IR injury.

Our previous studies have shown that inflammatory responses during reperfusion mediates lung IR injury (20). Furthermore, we found that CD4+ T cells are activated and elaborates this inflammatory response, resulting in subsequent activation of neutrophils, an end-effector that causes lung IR injury (24). The current study demonstrates that NADPH oxidase in BM-derived cells, most likely leukocytes, is activated and mediates the oxidative stress. NADPH oxidase is essential for phagocytic function of leukocytes (27). Recently, NADPH oxidase was found to be involved in CD4+ T cell activation (32). It is not clear whether the activation of NADPH oxidase during lung IR is involved in the process of CD4+ T cell activation or neutrophil activation, or both, which leads to lung injury. Further investigation is needed in this regard.

One mechanism for the reduced IR injury in NADPH oxidase-deficient animals lies in the reduction of proinflammatory cytokine/chemokine production. The significant induction of IL-17 after IR and subsequent reduction of IL-17 in NADPH oxidase-deficient animals, especially in the p47phox−/−→WT chimeras, suggests that IL-17–producing CD4+ T cells, perhaps NKT or Th17 cells, play a major role in the induction of lung IR injury. IL-17, produced mainly by NKT and Th17 cells and somewhat by neutrophils, has proinflammatory properties and acts on a broad range of cell types to induce the expression of cytokines (IL-6, IL-8, GM-CSF, G-CSF), chemokines (CXCL1, CXCL10) as well as metalloproteinases (33). IL-17 is also a key cytokine for the recruitment, activation, and migration of neutrophils (33). It is interesting that IFN-γ was not significantly induced by IR in this study, and perhaps a longer reperfusion time may reveal elevated IFN-γ production. The significant reductions of several major neutrophil chemokines such as IL-17, KC, and MIP-2 in this study helps explain the significantly reduced neutrophil infiltration in NADPH oxidase-deficient animals after IR as measured by MPO levels. The WT→p47phox−/− chimeras were very similar to WT→WT chimeras except that MCP-1 was also significantly reduced in these mice after IR. This might be explained by the fact that we have previously shown that a major source of MCP-1 after IR is alveolar epithelial cells, and perhaps NADPH oxidase–generated ROS is important for MCP-1 induction by these cells (22).

In summary, by using an NADPH oxidase inhibitor, p47phox−/− mice, and BM chimeras, this study demonstrates that NADPH oxidase activity in BM-derived cells is a key contributor to oxidative stress during IR and plays a critical role in mediating lung IR injury. Inhibition of NADPH oxidase by apocynin during reperfusion suffices to abrogate the oxidative stress and protects the lung against IR injury. NADPH oxidase might thus represent a novel therapeutic target for the treatment of lung IR injury after transplantation.

Funding for this project was provided by NHLBI/NIH award R01 HL077301 (to V.E.L.).

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0300OC on September 11, 2008

Conflict of Interest Statement: None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Granton J. Update of early respiratory failure in the lung transplant recipient. Curr Opin Crit Care 2006;12:19–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trulock EP, Edwards LB, Taylor DO, Boucek MM, Keck BM, Hertz MI. Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: twenty-third official adult lung and heart-lung transplantation report–2006. J Heart Lung Transplant 2006;25:880–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan A, Allen R. Bronchiolitis obliterans: an update. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2004;10:133–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.King RC, Binns OA, Rodriguez F, Kanithanon RC, Daniel TM, Spotnitz WD, Tribble CG, Kron IL. Reperfusion injury significantly impacts clinical outcome after pulmonary transplantation. Ann Thorac Surg 2000;69:1681–1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fiser SM, Tribble CG, Long SM, Kaza AK, Kern JA, Jones DR, Robbins MK, Kron IL. Ischemia-reperfusion injury after lung transplantation increases risk of late bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome. Ann Thorac Surg 2002;73:1041–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisher AB, Al-Mehdi AB, Muzykantov V. Activation of endothelial NADPH oxidase as the source of a reactive oxygen species in lung ischemia. Chest 1999;116:25S–26S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kennedy TP, Rao NV, Hopkins C, Pennington L, Tolley E, Hoidal JR. Role of reactive oxygen species in reperfusion injury of the rabbit lung. J Clin Invest 1989;83:1326–1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ucar G, Topaloglu E, Kandilci HB, Gumusel B. Effect of ischemic preconditioning on reactive oxygen species-mediated ischemia-reperfusion injury in the isolated perfused rat lung. Clin Biochem 2005;38:681–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fiser SM, Tribble CG, Long SM, Kaza AK, Cope JT, Laubach VE, Kern JA, Kron IL. Lung transplant reperfusion injury involves pulmonary macrophages and circulating leukocytes in a biphasic response. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2001;121:1069–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zimmerman BJ, Granger DN. Mechanisms of reperfusion injury. Am J Med Sci 1994;307:284–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ayene IS, al-Mehdi AB, Fisher AB. Inhibition of lung tissue oxidation during ischemia/reperfusion by 2-mercaptopropionylglycine. Arch Biochem Biophys 1993;303:307–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pearse DB, Dodd JM. Ischemia-reperfusion lung injury is prevented by apocynin, a novel inhibitor of leukocyte NADPH oxidase. Chest 1999;116:55S–56S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dodd OJ, Pearse DB. Effect of the NADPH oxidase inhibitor apocynin on ischemia-reperfusion lung injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2000;279:H303–H312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen JX, Zeng H, Tuo QH, Yu H, Meyrick B, Aschner JL. NADPH oxidase modulates myocardial Akt, ERK1/2 activation, and angiogenesis after hypoxia-reoxygenation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2007;292:H1664–H1674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harada H, Hines IN, Flores S, Gao B, McCord J, Scheerens H, Grisham MB. Role of NADPH oxidase-derived superoxide in reduced size liver ischemia and reperfusion injury. Arch Biochem Biophys 2004;423:103–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakagiri A, Sunamoto M, Murakami M. NADPH oxidase is involved in ischaemia/reperfusion-induced damage in rat gastric mucosa via ROS production–role of NADPH oxidase in rat stomachs. Inflammopharmacology 2007;15:278–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krause KH. Tissue distribution and putative physiological function of NOX family NADPH oxidases. Jpn J Infect Dis 2004;57:S28–S29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Papaiahgari S, Kleeberger SR, Cho HY, Kalvakolanu DV, Reddy SP. NADPH oxidase and ERK signaling regulates hyperoxia-induced Nrf2-ARE transcriptional response in pulmonary epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 2004;279:42302–42312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang Z, Day YJ, Toufektsian MC, Ramos SI, Marshall M, Wang XQ, French BA, Linden J. Infarct-sparing effect of A2A-adenosine receptor activation is due primarily to its action on lymphocytes. Circulation 2005;111:2190–2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao M, Fernandez LG, Doctor A, Sharma AK, Zarbock A, Tribble CG, Kron IL, Laubach VE. Alveolar macrophage activation is a key initiation signal for acute lung ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2006;291:L1018–L1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reutershan J, Cagnina RE, Chang D, Linden J, Ley K. Therapeutic anti-inflammatory effects of myeloid cell adenosine receptor A2a stimulation in lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury. J Immunol 2007;179:1254–1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma AK, Fernandez LG, Awad AS, Kron IL, Laubach VE. Proinflammatory response of alveolar epithelial cells is enhanced by alveolar macrophage-produced TNF-alpha during pulmonary ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2007;293:L105–L113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gazoni LM, Tribble CG, Zhao MQ, Unger EB, Farrar RA, Ellman PI, Fernandez LG, Laubach VE, Kron IL. Pulmonary macrophage inhibition and inhaled nitric oxide attenuate lung ischemia-reperfusion injury. Ann Thorac Surg 2007;84:247–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang Z, Sharma AK, Linden J, Kron IL, Laubach VE. CD4+ T lymphocytes mediate acute pulmonary ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2009. (In Press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Heumüller S, Wind S, Barbosa-Sicard E, Schmidt HH, Busse R, Schroder K, Brandes RP. Apocynin is not an inhibitor of vascular NADPH oxidases but an antioxidant. Hypertension 2008;51:211–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lapperre TS, Jimenez LA, Antonicelli F, Drost EM, Hiemstra PS, Stolk J, MacNee W, Rahman I. Apocynin increases glutathione synthesis and activates AP-1 in alveolar epithelial cells. FEBS Lett 1999;443:235–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang CK, Zhan L, Hannigan MO, Ai Y, Leto TL. P47(phox)-deficient NADPH oxidase defect in neutrophils of diabetic mouse strains, C57BL/6J-m db/db and db/+. J Leukoc Biol 2000;67:210–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barbieri SS, Cavalca V, Eligini S, Brambilla M, Caiani A, Tremoli E, Colli S. Apocynin prevents cyclooxygenase 2 expression in human monocytes through NADPH oxidase and glutathione redox-dependent mechanisms. Free Radic Biol Med 2004;37:156–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson DK, Schillinger KJ, Kwait DM, Hughes CV, McNamara EJ, Ishmael F, O'Donnell RW, Chang MM, Hogg MG, Dordick JS, et al. Inhibition of NADPH oxidase activation in endothelial cells by ortho-methoxy-substituted catechols. Endothelium 2002;9:191–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schluter T, Steinbach AC, Steffen A, Rettig R, Grisk O. Apocynin-induced vasodilation involves Rho kinase inhibition but not NADPH oxidase inhibition. Cardiovasc Res 2008;80:271–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Day YJ, Huang L, McDuffie MJ, Rosin DL, Ye H, Chen JF, Schwarzschild MA, Fink JS, Linden J, Okusa MD. Renal protection from ischemia mediated by A2A adenosine receptors on bone marrow-derived cells. J Clin Invest 2003;112:883–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guzik TJ, Hoch NE, Brown KA, McCann LA, Rahman A, Dikalov S, Goronzy J, Weyand C, Harrison DG. Role of the T cell in the genesis of angiotensin II induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. J Exp Med 2007;204:2449–2460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kolls JK, Linden A. Interleukin-17 family members and inflammation. Immunity 2004;21:467–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]