Abstract

Live imaging has gained a pivotal role in developmental biology since it increasingly allows real-time observation of cell behavior in intact organisms. Microscopes that can capture the dynamics of ever-faster biological events, fluorescent markers optimal for in vivo imaging, and, finally, adapted reconstruction and analysis programs to complete data flow all contribute to this success. Focusing on temporal resolution, we discuss how fast imaging can be achieved with minimal prejudice to spatial resolution, photon count, or to reliably and automatically analyze images. In particular, we show how integrated approaches to imaging that combine bright fluorescent probes, fast microscopes, and custom post-processing techniques can address the kinetics of biological systems at multiple scales. Finally, we discuss remaining challenges and opportunities for further advances in this field.

Over a wide range of scales, structures inside living organisms are highly dynamic. Chromatin moving inside the nucleus, morphogen diffusion, vesicle trafficking, cell migration, and organ morphogenesis are just a few key processes that span several orders of magnitude in size and speed. Although observing such processes over time has become possible in recent years, the role of biological motion in cell function remains poorly understood. Furthermore, quantitative kinetics characterization of enzymatic activity, protein maturation, or complex genetic networks, for example during cell differentiation, remains extremely scarce. Images captured over time constitute the ideal starting point to answer many of these questions. Live imaging is, however, notoriously difficult when high spatial and temporal resolutions are required.

In developmental and cell biology, an increasing body of work builds upon the availability of dynamic imaging techniques. Examples include cell motion analysis (Hass and Gilmour, 2006; Forouhar et al., 2006), cell-lineage tracing (Mathis et al., 2001; Hirose et al., 2004) or characterization of cell remodeling (Kulesa and Fraser, 2002; Kozlowski et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2007). Recently developed microscopes allow imaging of ever-faster processes and offer the possibility of studying morphogenesis and cellular dynamics at an unprecedented temporal resolution (Liebling et al., 2006). Several other fields in biology, such as high throughput imaging of cell cultures (Carpenter, 2007; Pepperkok and Ellenberg, 2006; Bakal et al., 2007) and systematic in vivo imaging of small animals for drug or phenotype screening (Starkuviene and Pepperkok, 2007; Burns et al., 2005) greatly benefit from and drive these improvements as they evolve to include more complex samples.

Imaging live samples at high speed is more demanding than imaging fixed samples. It requires a multidisciplinary approach and careful planning of the entire imaging protocol. We briefly survey the fundamental concepts and challenges that are of importance for dynamic in vivo imaging (including resolution, detectability, and vital fluorescence labeling). We then present technological developments to push resolution limits in both space and time at various levels of the imaging procedure, from sample preparation to image acquisition, processing, or analysis. Finally, we conclude by giving potential applications of the described techniques in developmental biology and biophysics and by discussing the importance of building seamless collaborations between biologists, microscopists, and engineers to take advantage of yet under-utilized paradigms in each of these fields.

IMAGING BIOLOGICAL MOTION

Scales and speed of biological motion

Dynamic processes in cellular biology span a broad range of velocities and scales. Some examples of this diversity are the speed of cell migration [140–170 μm∕h for neural crest cells (Kulesa and Fraser, 2000)], telomere motion in yeast [∼0.05 μm∕sec (Gasser, 2002)], fast calcium waves [10–50 μm∕sec (Jaffe and Créton, 1998)], red blood cell motion in the developing cardio-vascular system of rodents [1–10 mm∕s (Jones et al., 2004)], and the frequency of beating cilia [3–40 Hz (Sisson et al., 2003). Even though it is tempting to consider that the required microscope frame-rate to image motion only depends on the speed of the imaged sample, the required spatial resolution must be taken into account too. For example, the overall position of a small motile sample, say a paramecia in a dish, can be followed under a low magnification microscope even though its shape cannot be resolved. In order to observe the sample’s internal shape, however, both a higher magnification (with a higher resolution) and a higher imaging frame-rate are required. Indeed, at a high magnification, the moving sample sweeps across the field of view faster than at a low magnification. Therefore, temporal resolution (that is, the frame-rate) and spatial resolution cannot be considered independently. In the following section, we detail some guidelines on how to determine the required frame-rate in the general case of a moving sample.

Resolution and dynamic imaging

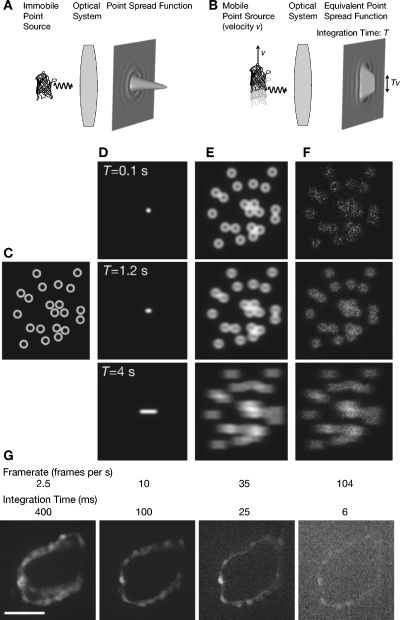

Techniques that aim at improving spatial resolution often require that the sample be (nearly) immobile. Evaluations of their performance rarely take motion into account. If we examine a moving fluorophore, we must revisit the concept of point spread function (PSF) and the resolution that it characterizes (see Table 1). In particular, we must consider the integration time—the time over which light is gathered by the detector—when modeling the image of a moving object: a new PSF, obtained through a normalized sum of PSF’s (each PSF in the sum corresponding to a different position of the sample) combines the effect of purely optical limitations with motion artifacts [Figs. 1A, 1B]. If the PSF of an immobile source has a width Δx, the width Δx′ of the point spread function corresponding to the moving source is approximately given by

| (1) |

where T is the integration time and v the velocity of the source. The second term in the sum, Tv, captures the blur induced by motion. As T or v increase, the resulting PSF can be considerably larger than its original version and effects due to motion can rapidly exceed those due to diffraction alone.

Table 1.

Spatial resolution and depth penetration in an immobile world.

| Resolution in an optical system can be gauged by examining the point spread function (PSF), the image of an idealized (infinitely small) point source, which corresponds to the system’s impulse response. In practice, the PSF can be measured by acquiring an image of a fluorescent micro-bead whose diameter is smaller than the wavelength (e.g., 10–200 nm). The image of a point does not appear as a point, but rather as a disc of approximate diameter Δx that bears additional concentric rings. An idealized PSF (an Airy disc) is depicted in Fig. 1A. When the distance between two nearby beads is decreased, the image they yield, two discs, eventually joins to become a single spot. The smallest distance for which the two discs can still be told apart is a direct measure of the microscope resolution. It should be noted that resolution, since it is measured directly on the sample, is a concept separate from magnification. Abbe’s diffraction law (Born and Wolf, 1999), | |

| Δx≈0.61λ∕(2n sin α), | (5) |

| where Δx is the achievable resolution, λ is the wavelength of light, n is the refractive index of the immersion medium, and α is half of the microscope objective angular aperture, prescribes that only details that are larger than about half the wavelength of light can be discerned with optical microscopes. For example, confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM), arguably one of the most widely used methods for in vivo imaging, has a resolution that can approach 200 nm laterally by 500 nm axially. The axial resolution follows the relation | |

| Δz≈2nλ∕(NA)2 | (6) |

| with NA=n sin α the numerical aperture of the microscope objective. Typical resolutions for several other types of microscopes are summarized in Table 3. In order to resolve single fluorescent proteins whose size can be just tens of nanometers small, higher resolution methods are required and several optical super-resolution approaches have been devised to this end. Structured illumination techniques (Gustafsson et al., 1999; Gustafsson, 2005), stimulated emission depletion microscopy (STED) (Hell, 2007), fluorescent photo-activation light microscopy (PALM) (Betzig et al., 2006; Hess et al., 2006), stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM) (Rust et al., 2006) are just some of the techniques that allow improving the spatial resolution beyond the diffraction limit [see (Haustein and Schwille, 2007) for a review]. Since their acquisition time can be prohibitively long, these techniques are, however, mostly limited to imaging fixed samples. Nevertheless, live imaging has been reported with at least one of them (Egner et al., 2002b). Although the achievable spatial resolution primarily depends on the microscope objective and its numerical aperture, all media that are on the optical path contribute to shaping the PSF (see Sec. 2.2). This includes, in particular, any coverslips, mirrors, and other optical elements. Samples whose thickness exceeds a few microns by themselves can be the most important source of image degradation: light refraction and scattering cause distortions and position changes of the illumination spot [CLSM, two-photon microscopy (TM)], loss of photons during collection, or light contributions from out of focus regions. Several animal models such as certain roundworms, sea squirts, or tropical fish (e.g., Caenorhabditis elegans, Ascidiella aspersa, and Danio rerio, respectively) are excellent animal systems for live tissue imaging since their embryos are essentially transparent thereby reducing light scattering to a minimum. For samples whose optical properties are less ideal, that require higher depth penetration, or that are extremely photo-sensitive, multi-photon microscopy (Denk et al., 1990) is a particularly attractive solution and has been used successfully for imaging live organisms (Potter, 1996; Helmchen and Denk, 2005). Also, several techniques that take advantage of adaptive optical elements to correct for aberration introduced by the sample have been developed (Kam et al., 2001; Rueckel et al., 2006; Chu et al., 2007). | |

Figure 1. Sample motion and long integration time reduce spatial resolution.

(A) When imaged through an optical system, photons emitted by a point source hit the image plane at any given position with a probability related to the point spread function. (B) When the point source is in motion (with a velocity v) it produces a smeared point spread function whose extent Tv (with T the integration time) can exceed the extent of the point spread function resulting from diffraction alone. (C) In this simulation we consider ring-like structures that are moving with a uniform velocity from left to right. (D) As the integration time T increases, the equivalent point spread function becomes more elongated. (E) When the sample is bright, it appears blurred as the integration time increases. (F) Dim, moving samples require both short integration times to limit the spread of the point spread function, but also a sufficient photon count to yield satisfying signal to noise, thereby calling for a compromise between resolution and detection. (G) Single slice of a beating embryonic zebrafish heart imaged with a spinning disc confocal microscope at increasing frame-rates and decreasing integration times. Longer integration times result in images with motion blur artifacts but higher photon counts whereas high frame-rates have lower signal to noise ratio requiring, again, a compromise. Scale bar is 50 μm. [See also Supplementary movies (EPAPS)].

Conversely, when sources separated by a distance Δx′ must be resolved in a sample that moves at a velocity v, the required frame-rate, considering a microscope that can resolve immobile sources separated by a distance Δx, is given by (assuming Δx′>Δx)

| (2) |

Clearly, when the microscope does not permit imaging immobile structures with sufficient resolution (Δx′⩽Δx) imaging the same structure as it moves is not possible.

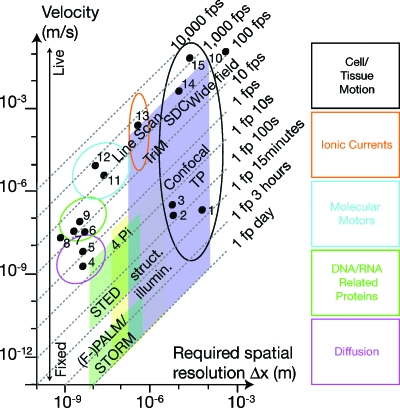

Based on Eq. 2 (and assuming Δx′⪢Δx), we considered several biological specimens (gathered in Table 2) and displayed them according to their speed and the required spatial resolution in the graph of Fig. 2. Based on their location in this graph, the required frame-rate can be deduced. The required frame-rate increases either as a consequence of increased sample speed or increased spatial resolution requirements. We superimposed the approximate frame-rates and achievable resolutions of some widespread and emerging microscopy techniques (Table 3). It is apparent that improvements of both temporal and spatial resolution are required to image many classes of biological samples.

Table 2.

Speed and scale of some biological processes. Processes are ordered according to increasing frame rates (f) that are required to image them at a resolution Δx′. We calculated f using a simplified version of Eq. 2, f=v∕Δx′ where Δx′ was taken to be 1∕10th of the imaged structure size. Note how slow processes can require high framerates since f also depends on the required imaging resolution. For example, the motion of broken DNA ends is slow (1 nm∕s, the slowest process in the table) but it ranks fourth according to required frame rate.

| # Fig. 2 | Name | Required frame ratef | Required resolution Δx′ (μm) | Size of structure (μm) | Velocityv (μm∕s) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Somite formation in chicken | 6 fph | 10 | 100 | 1.8×10−2 | (Palmeirim et al., 1997), (Kulesa and Fraser, 2002) |

| 2 | Mesodermal cell motion during chicken gastrulation | 1 fpm | 1 | 10 | 1.7×10−2 | (Zamir et al., 2006) |

| 3 | Neural crest cell migration in chicken | 2.4 fpm | 1 | 10 | 40×10−3 | (Kulesa and Fraser, 2000) |

| 4 | DNA broken ends in mammalian cells | 24 fpm | 2.5×10−3 | 25×10−3 | 10−3 | (Soutoglou et al., 2007) |

| 5 | Morphogen diffusion (drosophila Decapentaplegic) | 72 fpm | 2.5×10−3 | 25×10−3 | 3×10−3 | (Kicheva et al., 2007) |

| 6 | Ribosome translating mRNA (E. coli) | 10 fps | 4×10−3 | 40×10−3 | 4×10−2 | (Berg et al., 2001), (Alberts et al., 2002) |

| 7 | DNA Polymerase T7 Polymerizing plasmidic DNA | 15 fps | 2×10−3 | 20×10−3 | 30×10−3 | (Wuite et al., 2000) |

| 8 | Protein folding | 20 fps | 10−3 | 10×10−3 | 2×10−2 | (Cecconi et al., 2005) |

| 9 | Telomere displacement in yeast | 20 fps | 2.5×10−3 | 25×10−3 | 50×10−3 | (Gasser, 2002) |

| 10 | Flagelated cell | 100 fps | 0.1 | 1 | 10 | (Bray, 1992) |

| 11 | Microtubule polymerization of cytoplasmic extracts from xenopus eggs | 167 fps | 3×10−3 | 30×10−3 | 0.5 | (Parsons and Salmon, 1997) |

| 12 | Kinesin I on a microtubule pulling a bead | 180 fps | 5×10−3 | 50×10−3 | 0.9 | (Nishiyama et al., 2002) |

| 13 | Calcium waves during heart development | 150 fps | 5 | 50 | 103 | (Tallini et al., 2006) |

| 14 | Embryonic zebrafish beating heart | 200 fps | 5 | 50 | 103 | (Forouhar et al., 2006), this report |

| 15 | Red blood cells in the developing cardio-vascular system | 103 fps | 1 | 10 | 103 | (Jones et al., 2004) |

Figure 2. Imaging scales and speed in biology.

Each point represents one biological event placed according to the required space resolution to image it and its speed. The boxes underline the time and space resolution of several far-field microscopes available for biological imaging. Spatial resolution increases at the expense of time resolution. Oblique lines represent the required frame-rate in order to resolve the motion of objects given their velocity and the required spatial resolution. Velocities and frame-rates (with according references) are given in Tables 2, 3. TP: two-photon microscopy, SDC: spinning disk, struct. illum.: structured illumination.

Table 3.

Features of several fluorescence microscopy techniques in the light of fast imaging. The normalized dwell time is the ratio of the time a pixel is illuminated divided by the total time it takes to acquire one frame. The ratio of the collection volume to the illumination volume gives a good feel of how the system will behave in terms of bleaching. Struct. Illum.: Structured Illumination, Pt: single beam point scanner, Multipt: multi-beam, 1D: line array detector, 2D: two-dimensional array detector (CCD,…), P: point detector (PMT,…), y: yes, n: no, Pin: adjustable slit, Sli: adjustable width slit. The more * the better. †: requires additional setup. ‡: in one direction only.

| Microscope type | Illumination type | Normalized dwell time | Detector type | Sectioning capability | Penetration depth | Region of interest | Adjustable collection volume | Conventional mounting | Lateral resolution | Temporal resolution | Bleaching | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Widefield | |||||||||||||

| Conventional | Uniform | 1 | 2D | * | * | * | n | ∅ | y | ** | *** | * | (Murray et al., 2007) |

| Struct. illum. sectioning | Patterned | 1 | 2D | * | ** | * | n | ∅ | y | *** | * | * | (Neil et al., 1997) |

| Confocal | |||||||||||||

| Single beam | Pt | 10−6 | P | ** | *** | ** | y | Pin | y | **** | ** | ** | (Wilson, 1990) |

| Spinning disk | Multipt | 10−3 | 2D | ** | *** | ** | y† | ∅ | y | *** | *** | ** | (Graf et al., 2005) |

| Line scanning | Line | 10−3 | 1D | ** | *** | ** | y‡ | Sli | y | *** | **** | ** | (Wolleschensky et al., 2006) |

| Multiphoton | |||||||||||||

| Single beam | Pt | 10−6 | P | *** | *** | *** | y | ∅ | y | *** | *** | *** | (Helmchen and Denk, 2005) |

| Multi-beam | Multipt | 10−5 | 2D | *** | *** | *** | y | ∅ | y | *** | *** | *** | (Niesner et al., 2007) |

| SPIM | Sheet | 1 | 2D | *** | **** | *** | n | ∅ | n | *** | *** | *** | (Huisken et al., 2004) |

Fluorophore characteristics

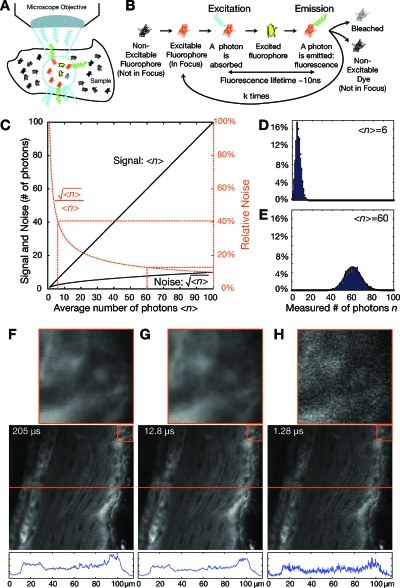

Often, the limitation to fast imaging is not the microscope but the fluorophore. Major parameters to take into account are the fluorophore brightness (which is proportional to the product of the extinction coefficient, a quantity related to the fraction of photons that are absorbed by the dye, and the quantum yield, the fraction of absorbed photons that yield fluorescence photons), its fluorescence lifetime, and the concentration. The brighter a dye, the fewer photons are required to illuminate the sample, which allows for illumination time reduction. An increased fluorophore concentration allows decreasing the excitation time significantly (while keeping the emitted photon count constant), but a higher dye concentration can increase photo-toxicity and lead to self-quenching of the dye resulting in the reduction of its quantum yield. Finally, the fluorescence lifetime corresponds to the average time between a fluorophore being excited and emitting a photon [see Figs. 3A, 3B]. It directly affects the maximal repetition rate at which images can be acquired. Since acquisition of a single image requires going through one full cycle of excitation and light emission, decreasing the time between sample excitation (e.g., by faster scanning) near the fluorescence lifetime results in the inability to determine at which cycle an emitted photon was excited (given that emission times are stochastic, see below). The optimal settings of fluorophore concentration, illumination time, and intensity must usually be determined experimentally.

Figure 3. Fluorescence, Poisson processes, and integration time.

(A) In a sample, only fluorophores in the light path and, in particular, in the focus regions are susceptible to be excited and emit photons through fluorescence relaxation. Photons are emitted in arbitrary spatial directions and only photons that are emitted in a direction covered by a cone corresponding to the objective’s numerical aperture contribute to the signal. Photons are subsequently absorbed by the optical system and the detector only captures a select fraction. (B) A single fluorophore that is illuminated can absorb a photon before eventually emitting a fluorescence photon. As long as the fluorophore is illuminated, the cycle can be repeated until the fluorophore is bleached and does not contribute to the signal anymore. A typical number of cycles is 105. (C) The absorption of a photon and the exact time at which a fluorescence photon is emitted is random and can be modeled by a Poisson process. For an average number of emitted photons ⟨n⟩, the variance is . The relative noise decreases as the number of measured photons increases. (D) For a low average count of photons, the variance of the actual measurement is high and (E) proportionally decreases with higher photon counts. (F) In order to decrease the acquisition time, the dwell time (integration time on a single pixel, indicated on slice) must be reduced. (G), (H) As the dwell time decreases, the images appear grainy due to the limited photon count and higher relative fluctuations.

In order to keep the photon count per pixel constant when increasing the frame rate, it might be tempting to simply increase the illumination power. Thereby, the probability of fluorophore excitation and the number of emitted photons would remain constant (see Fig. 3). However, a high illumination intensity increases the risk of fluorophore saturation, photo-bleaching, photo-toxicity, and photo-damage. Photo-toxicity is still poorly understood but likely involves photogenerated oxidative stress during sample illumination and fluorescence emission (Lichtman and Conchello, 2005). Setting the laser power as low as possible and using dyes with a high quantum yield allow limiting photo-toxicity. When using digital cameras, photon counts can be improved by increasing the photon collection area (pixel-binning) as an alternative to increasing illumination power. This implies, however, a decrease in spatial resolution.

When every photon counts

When increasing the frame rate while keeping every other imaging parameter unchanged, fewer photons are captured by the imaging system as the time interval between frames decreases. The PSF should merely be considered a probability density function that a photon, emitted by a fluorophore, hits the imaging surface at a given position. The higher the value of the point spread function at a given location, the higher the probability of a photon hitting there. In addition to the shape of the PSF, it is the total number of measured photons that specify the quality of the image [see Fig. 1C, 1D, 1E, 1F].

The number of photons that are emitted during a given time interval is stochastic but can be modeled, for example, by a Poisson process. If the average number of photons, N, emitted in a set time interval is given, the probability that a number, n, of photons are emitted is given by the probability function

| (3) |

Histograms showing the number of emitted photons during multiple experiments and for an average number of photons N=6 and 60 are shown in Figs. 3D, 3E, respectively. The average number of measured photons, the signal, is ⟨n⟩=N and the standard deviation, the noise, is . The ratio between the two is plotted in Fig. 3C. As the average number of measured photons increases, the relative amount of noise decreases. This is visible in Fig. 1G, where confocal images have been acquired with increasing scan speed, that is, a reduced dwell time (time corresponding to the excitation time for a given pixel) and images appear more grainy when acquisition time is decreased.

AVOIDING IMAGING ARTIFACTS RELATED TO FAST BIOLOGICAL MOTION

In addition to the traditional challenges faced when imaging fixed samples at high magnification (Stelzer, 1998; Brown, 2007), sample motion can introduce other artifacts that should be avoided at all costs. To help the reader recognize these defects and determine how to properly balance all imaging parameters, we discuss below several common, yet hard to spot, situations in which insufficient temporal resolution can lead to dramatic data misinterpretation.

Motion blur

Insufficient time-resolution (that is when the frame-rate is too low for the measured phenomenon) may lead to two main artifacts: motion blur and aliasing. Blurring arises because in order to capture a single frame, light is gathered over a certain period of time (integration time) rather than instantaneously. Particles that move too quickly under the microscope yield streaks that follow their trajectory (motion blur). Similarly, details appear blurred on photographs taken with too long an exposure time [see Figs. 1C, 1D, 1E, 1F, 1G, 5D, 5G]. Further processing and analysis, e.g., particle tracking, is difficult on such images since the objects are not well localized.

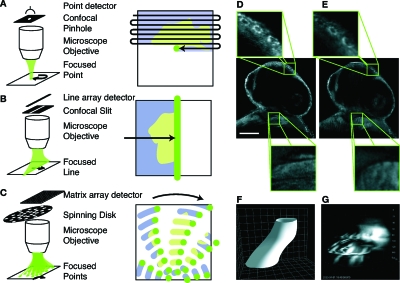

Figure 5. Fast confocal microscopy and scanning artifacts.

(A)–(C) Confocal microscopy rejects out of focus light via a pinhole aperture that is confocal with the imaging plane. (A) Point-scanning confocal microscopes require raster scanning the focused light over the whole sample to acquire an image. (B) By using light shaped to a line and a slit instead of a pinhole, superior acquisition speeds can be achieved since scanning is only required in a single direction. (C) Other ways to increase acquisition speed over point scanning is by use of multiple focused light points and pinholes, e.g., arranged on a spinning disc. (D) While point scanners provide high spatial resolution and axial selectivity (detail, top) fast moving structures such as the heart in this 30 h post fertilization (hpf) old zebrafish embryo (BODIPY FL fluorescent dye) cannot be captured with sufficient accuracy (detail, bottom). Scale bar is 100 μm. (E) With frame-rates 10–100 fold more rapid than those of point-scanning microscopes, line-scanning confocal microscopes can capture the actual structure of the beating heart (detail, bottom), while keeping good spatial resolution and optical sectioning ability (detail, top). (F) Three-dimensional cartoon of the heart-tube and (G) as measured by successively imaging planes along the Z direction of the heart in a 30 hpf transgenic Tg(cmlc2:EGFP) zebrafish. Similarly to panel D, during the time it takes for scanning along Z (2–3 s), the heart has time to beat five times resulting in a corrupted image [see also Supplementary movie (EPAPS)]. More sophisticated techniques are required to capture the actual geometry of the heart tube. Grid spacing is 20 μm.

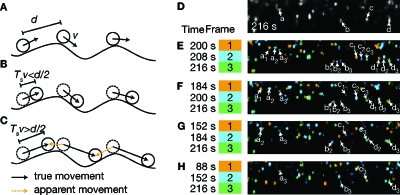

Temporal aliasing

Temporal aliasing can occur when images are acquired with a short integration time, but the time interval between two frames is too large to permit faithful replication of the original signal when it is played back. Imaging cyclic or oscillatory motion is particularly prone to this effect, which can make the motion appear to take place at a wrong frequency. A classical example of temporal aliasing is the wagon-wheel effect in motion pictures: rotating stagecoach wheels or helicopter propellers often appear to be rotating at a slow frequency or in the wrong direction. In order to avoid aliasing, the acquisition rate should be at least twice that of the highest frequency to be imaged. Conversely, for a given frame-rate, the highest frequency that may be imaged without aliasing (Nyquist frequency) is equal to half that frame-rate. For example, successful characterization of the direction of cilia rotation in the mouse node necessitates the use of high frame rate acquisition (Nonaka et al., 1998; Nonaka et al., 1999).

Often, the velocity itself is the object of study and, therefore, unknown beforehand. For example, when studying vesicular transport, an improper acquisition rate can generate spectacular artifacts with apparent changes in transport direction from anterograde to retrograde [Figs. 4D, 4E, 4F, 4G, 4H and Supplemental movie (EPAPS)]. In that case, spatial resolution and field of view extent should be sacrificed [possibly by limiting the measurements to scanning a single line (Jones et al., 2004)] in order to reach a high enough frame-rate and characterize speed and eventually the minimal frame-rate. A simplified example that illustrates this situation is depicted in Figs. 4A, 4B, 4C. Indistinguishable particles travel with a velocity, v, along a path and are separated by a distance, d. When images are acquired with a time interval, Ts, between two frames, for the particle direction and trajectory to be extracted unambiguously the distance Tsv traveled by the particles in between two frames must be less than half the distance d separating the particles, viz.,

| (4) |

Cell-lineage studies based on time-lapse image series can suffer from similar artifacts. Despite the slow cell motion, images are acquired over large fields of view and extended periods of time to get a comprehensive map of cell behavior at the scale of the embryo (Fraser and Stern, 2001). Again, the frame-rate should be such that the maximal distance traveled by any cell in the time between two frames is smaller than half the minimum distance between the centers of any two cells.

Figure 4. Frame-rates for time-lapse imaging and particle tracking.

(A) Particle trafficking along a path. The distance separating two particles is d and their velocity is v. (B) When the distance Tv traveled by the particle between two frames is smaller than d∕2, the particle direction of motion and trajectory can be extracted unambiguously. (C) When the distance traveled is larger than d∕2, apparent movement can be interpreted as the true movement (temporal aliasing). (D) Single frame detail of an 8 s interval time-lapse movie showing fast anterograde transport of peptide-conjugated beads in the squid giant axon. Four beads have been annotated a, b, c, and d [data reproduced from (Saptpute-Krishnan et al., 2006) with permission from the authors]. (B) Three frames separated by 8 s are assigned individual colors and superimposed. The motion of the cells marked in D can be followed. (F)–(H) When slower frame-rates are considered that are incompatible with the particle density, individual cells cannot be followed unambiguously. See also Supplementary movie (EPAPS).

Deformations from slow scanning

When images are raster scanned from the upper left corner to the lower right corner [see Fig. 5A], all pixels are, by definition, not acquired simultaneously. When the imaged structure moves during the scan, artifacts can appear that give the structure a deformed shape, such as for the heart illustrated in Fig. 5D. This problem not only occurs at the level of a single frame, but also when acquiring z-stacks of moving structures [Fig. 5G]. Again, increasing the scanning speed (this time in all spatial directions) would be a way to overcome this problem. In the case of a periodic motion, as discussed in the Image registration section, this problem can be overcome through sequential acquisition of slice-sequences and subsequent temporal registration (Liebling et al., 2005).

FAST MICROSCOPES: RECENT ADVANCES AND LIMITATIONS

A variety of microscopes have been developed recently to permit imaging of fluorescent samples at high speed. We concentrate on some techniques that are available commercially or that have been designed for biological in vivo imaging. The different microscopes' characteristics are given in Table 3.

Widefield fluorescence microscopy

Widefield fluorescence microscopes have largely benefited from recent advances in digital camera technology. Since the camera can capture an entire 2D field of view, this technique is potentially very fast with camera speed and sensitivity as its major limitations. Indeed, at high frame-rates, cameras require very good detection performance to capture the small number of photons emitted over a short integration times. Although widefield microscopy does not, in its simplest form, allow for optical sectioning, several modification have been proposed to improve performance in this regard. These include deconvolution microscopy (Swedlow et al., 1997), structured illumination (Neil et al., 1997), and interference-based illumination and detection (Gustafsson et al., 1999). Widefield microscopy (as opposed to confocal microscopy, see below) can yield very high signal-to-noise levels since no emitted light is rejected. It is, however, fluorescence light emitted throughout the entire sample depth that contributes to this signal. Therefore, in order to achieve optical sectioning, it is necessary to acquire multiple images and carry out time-consuming computational post-processing (structured illumination, deconvolution).

Confocal microscopy

Point scanning. Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) has long suffered from slow frame rates since a focused laser beam must be raster-scanned over the whole image in order to acquire one single frame [see Fig. 5A]. Fast raster scanning can be achieved by mounting one of the scan mirrors on a resonant scanning galvanometer. Although the speed at which the scanning itself can be carried out may be the limiting factor, it is usually not sufficient to increase scanning speed to get satisfactory images at high frame rates. Indeed, faster scanning reduces the dwell time of the laser beam on any one pixel and, as a consequence, the brightness of the sample (see Fig. 3). The use of high sensitivity detectors, typically photo-multiplier tubes (PMT) and avalanche photo-diodes (APD), can only partially compensate for these low photon counts resulting from the high scanning speed. Additionally, optimized optical paths and low-loss wavelength selection are essential features of fast point-scanning confocal microscopes. Despite the fact that scanning hampers speed, confocal laser scanning microscopy gives flexibility in terms of regional scanning and yields excellent spatial resolution.

Multi-beam scanning. Parallelization of the single beam illumination process is at the heart of several variations of CLSM. In single beam scanning, one beam is scanned over the entire sample. Laser intensity must be increased as scanning speed increases in order to retain a high fluorophore excitation probability for these short dwell times. When multiple beams are scanned, the excitation light is divided into several beams that are focused at different locations on the sample (for example, on a grid or a spiral pattern). Since there are multiple beams scanning in parallel, the dwell time for any given pixel is proportionally longer than in the case of a single scanned beam. As a consequence, for a given frame-rate, the illumination light intensity per beam can be lowered, thereby reducing the risk of phototoxicity and fluorophore saturation (Graf et al., 2005; Tadrous, 2000; Egner et al., 2002a), (see Table 3).

One example that takes advantage of multi-beam scanning is spinning disk confocal microscopy (SDC). In one configuration, two spinning conjugated disks, one bearing micro-lenses and the other confocal pinholes permit splitting the laser beam into multiple spots and acquire images at high frame-rates onto a camera as the detector (Tanaami et al., 2002). It is schematically shown in Fig. 5B. The high degree of parallelization (over 103 simultaneous beams) permits imaging at high frame-rates with a limited increase of illumination power. In addition to spinning disks, other configurations for fast multi-beam scanning exist, including geometries of oscillating pinhole arrays and spinning line arrays that produce virtual pinholes. Multiple beam confocal microscopes are popular among cell biologists due to the fact that fast imaging can be carried out with lower light intensities than with single beam confocal microscopes (for a given frame-rate).

The limitations include the fact that the pinhole size cannot be varied and, therefore, ties the microscope to a given magnification, the high sensitivity to any mismatch between disk rotation frequency and camera frame-rate as well as limited options for region of interest illumination and imaging. SDC also have lower penetration depth than single beam scanning microscopes because of crosstalk between pinholes (out of focus photons that are blocked by one pinhole can still be collected by another pinhole) due to increased light scattering when imaging thick samples (Graf et al., 2005). Frame-rates are typically limited by the maximum camera speed (see Table 3).

Line scanning. By simultaneously illuminating an entire line (line scanning) that is scanned across the sample (instead of a single point in classical CLSM), by using a slit instead of a pinhole to reject out-of-focus light, and by using a line instead of a point detector, fast confocal imaging can be achieved (Brakenhoff and Visscher, 1992; Wolleschensky et al., 2006). Similar to multiple beam confocal microscopy, this technique takes advantage of the parallel illumination and acquisition from multiple points (retaining its advantages regarding reduced illumination requirements), but the ability to adjust the slit size makes it a versatile alternative, in particular for fast imaging deep inside embryos (Liebling et al., 2006; Lucitti and Dickinson, 2006).

SPIM

An alternative to confocal microscopy is the recently proposed selective plane illumination microscope (SPIM). In SPIM, an entire plane of the sample is illuminated laterally and collection is carried out with a wide-field microscope (Huisken et al., 2004). SPIM offers two main advantages over confocal microscopes: First, since it is, in essence, a whole-field imaging technique, no light needs to be rejected in order to achieve optical sectioning and, second, photo-bleaching is limited since only the plane of interest is illuminated. Optical sectioning is achieved through excitation alone. Also, since individual slices are acquired in a single shot by a digital camera, it has the potential for high-speed imaging. SPIM has been used for the imaging of whole embryos at low magnification (Huisken et al., 2004; Verveer et al., 2007; Scherz et al., 2008) or individual structures at higher magnification. SPIM requires that sample mounting be reconsidered since the sample must be optically acces-sible both laterally and axially. This also makes imaging at very high magnifications more difficult.

Multi-photon microscopy

In two-photon microscopy, fluorophores are excited by two photons of approximately half the energy (or twice the wavelength) of the photons used in confocal microscopy. Since scattering loss is less for longer wavelengths (near infrared), two-photon excitation light can penetrate deeper into tissues. Also, photons at higher wavelengths carry less energy and are, therefore, less detrimental to the tissue outside of the excitation volume. Recent progress in laser engineering has made multi-photon microscopes as convenient to use as confocal microscopes and has contributed considerably to the expansion of live imaging to thick tissues. Yet, the high cost of the light-sources usually makes this an expensive technique. Similar to the evolution in fast confocal microscopy, parallelization has lead to new multi-photon microscopes. In multi-focal multi-photon microscopy (TriM) (Bewersdorf et al., 1998; Egner and Hell, 2000), the beam is split up as it cascades repeatedly through a beam-splitter. Since detection is carried out in wide-field, the major limitation is cross-contamination from the multiple beams at the detection level along with the necessity for a very high power laser that can be split into multiple beams of sufficient power each.

BEYOND THE MICROSCOPES: INCREASING SPEED VIA SOFTWARE SOLUTIONS AND AUTOMATION

Image processing plays a central role in fluorescence microscopy (Vonesch et al., 2006). In recent years, several groups have developed integrated imaging paradigms where experiments intrinsically combine microscopy and image processing. Such combined approaches can be very fruitful since, for example, physical limitations can be overcome via software solutions or, conversely, image analysis that requires sophisticated algorithms can be considerably simplified using alternative microscopes and help push temporal resolution.

Image restoration

Widefield microscopy allows for very fast image acquisition. In order to achieve optical sectioning, however, it requires post-processing deconvolution. Deconvolution algorithms, which are often iterative, can be extremely slow and require major computing power. For deconvolution microscopy to become as straightforward to use as confocal microscopy, algorithms several orders of magnitude faster are required. Nevertheless, since restoration often does not need to be carried out at the time of acquisition, wide-field imaging coupled to deconvolution algorithms appears as a viable alternative to overcome the slowness of traditional confocal microscopes, yet retaining optical sectioning abilities. High-speed wide-field imaging platforms coupled to off-line deconvolution computational cores have been developed for that purpose (Racine et al., 2007).

Image registration

Some biological structures are moving so fast that conventional 3D image acquisition is no longer possible. For example, in the embryonic heart, the heart wall can reach a velocity approaching 1 millimeter per second, which can create scanning artifacts that prevent proper shape characterization [see Fig. 5D, 5G]. Recently, an approach to overcome these problems has been implemented (Liebling et al., 2005, 2006). Using a fast confocal slit-scanning microscope, the focus is kept the same for a whole rapid sequence of images and then is only changed to repeat the acquisition of the next image sequence at high speed. Since the heart motion is periodic, 3D volumes can be reconstructed through temporal registration over the entire heartbeat. Through an alternative acquisition procedure and a computational reconstruction algorithm that takes advantage of the cyclical movement of the heart, one can thus overcome weaknesses in the microscope acquisition rate.

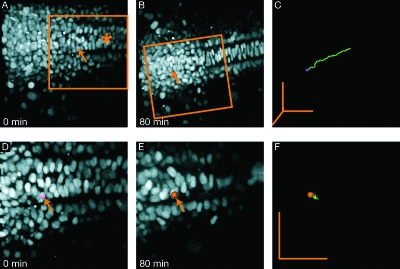

Another challenge is the imaging of structures within growing tissues over several hours, which results in large overall displacements of the region of interest. Such a situation is described in Figs. 6A, 6B, 6C, where the cells of a developing zebrafish embryo that lie on top of the yolk sack undergo tremendous displacements. The most common solution is to increase the field of view in order for the region of interest to remain in view for the whole duration of the time-lapse. Then the region of interest can be recursively aligned over the course of the time-lapse and relative cell motions (or their absence) can be revealed [Figs. 6D, 6E, 6F]. Such approaches require, however, that larger fields of view be scanned. A more desirable technique would be to adjust the imaging position adaptively, which has been implemented for simple systems (Rabut and Ellenberg, 2004). By using such an approach for in vivo imaging, the field of view could be decreased significantly and the frame-rate increased accordingly.

Figure 6. 3D Time lapse imaging of zebrafish embryo injected at one cell stage with H2B-GFP mRNA that marks the cells’ nuclei.

(A)–(C) Data before recursive registration. Global cell motion due to embryo growth makes local cell motion difficult to extract and requires large fields of view. (A) First frame of time-lapse at 11 hpf. The mid-line is visible (asterisk) and one cell has been marked with a spot (arrow). (B) At the end of the time-lapse, the cell marked in A has moved across the field of view. (C) Marked cell track. (D)–(F) After recursive registration the local, relative motions of individual cells can be analyzed. Marked cell is the same as in A. (D) Detail (3D crop) of first frame (approximate location is marked in panel A). (E) Last frame, with global cell motion subtracted (F) Marked cell track. Grid spacing is 10 μm (50 μm scalebars in all directions).

Sub-resolution tracking

To the human eye, images of small molecules acquired with wide-field fluorescent microscopes can appear to be static due to poor spatial resolution or rapidly moving due to the high level of noise. Therefore, it is very difficult to demonstrate that structures are indeed immobile or, conversely, highly motile. An interesting approach has been described (Soutoglou et al., 2007; Thomann et al., 2003) where, using sub-resolution tracking combined with a statistical framework for data modeling and analysis, significant movements and colocalization can be determined. Interestingly, the trajectory accuracy can exceed the optical resolution, even though the source images are of standard optical resolution, but provided the acquisition speed is high enough.

High-throughput imaging

High-throughput screens require the analysis of huge numbers of samples over short periods of time as well as fully automated protocols. So far, high-throughput approaches have proven successful for imaging cell morphology changes in response to drugs (Carpenter 2007) or gene knock-downs (Bakal et al., 2007). A number of plate readers allowing automated image acquisition are available on the market (Pepperkok and Ellenberg, 2006) and can be associated with computers that segment and discriminate between basic phenotypes (Bakal et al., 2007). By coupling automated stages to fast microscopes, prospects for extending such techniques to whole-animal imaging and developmental biology studies are excellent. They should, in particular, allow increasing the number of observations, to image several embryos simultaneously and to limit the time spent in front of the microscope (Megason and Fraser, 2007).

BRIGHT PERSPECTIVES FOR MULTI-DISCIPLINARY IMAGING

It is unquestionable that independent development of fluorescent probes, novel microscopes, and general-purpose image processing and analysis software will enlarge the scope of possible applications for fast imaging over the years to come. We believe that an even greater potential lies in the judicious combinations and integration of existing (as illustrated in the previous section) and upcoming methods to build novel applications. To conclude this perspective we provide several pointers to possible extensions of existing methods and interactions that we believe can tremendously improve fast imaging. Developmental biology and biophysics are likely to benefit from these advances.

Developing optimal imaging protocols

Successful imaging projects frequently depend on interactions between two or more fields. Breakthroughs in both imaging and biology were achieved by combining molecular or developmental biology with microscopy (Mathis et al., 2001; Livet et al., 2007; Scherz et al., 2008), biology with physics (Hove et al., 2003; Supatto et al., 2005), biology with image analysis (Soutoglou et al., 2007), or biology with mathematical modeling (Surrey et al., 2001). Considering the complexity of each individual technology, combined with the biological challenges of keeping the sample in optimal conditions for fast imaging, tight collaborations between biologists, chemists, computer and electrical engineers, mathematicians, and physicists are highly desirable. When each contributing party is also involved at the time of experiment planning, major hurdles in the image acquisition, processing, or analysis can be identified early on and more possibilities for alternatives can be found. Clearly, such multidisciplinary projects reach their full potential in academic environments where multiple departments are concentrated in close geographical areas, but this is by no means a requirement.

In vivo biophysics and cell biology

With the standardization of live imaging protocols and the growing accessibility to live samples, live embryos can be considered the new “test tube” for biophysicists or “culture dish” for cell biologists. Many structures that fascinate biophysicists, such as cilia, the cell membrane, the cytoskeleton, and vesicles are now accessible by dynamic imaging in live tissue. Clearly, biology is different in 2D than 3D as has been shown, for example, during cell biology experiments in 2D and 3D culture media (Griffith and Swartz, 2006) or by analyzing intracellular microtubule growth in 3D (Keller et al., 2007), demonstrating the need for finer 3D imaging methods to understand biological systems. This will be of particular interest for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine where the complex interaction between genetics and cell environment both in culture and in tissue needs to be understood. Furthermore, measurements of 3D deformation at the tissue scale with cellular resolution open new possibilities for studying tissue biomechanics and the numerous signaling pathways involved that have been proposed to be reactive to mechanical deformations (Farge, 2003; García-Cardeña et al., 2001; Nichols et al., 2007; Avvisato et al., 2007). Again, imaging deformations at microscopic scales does not only require excellent spatial but also temporal resolution.

Filling the gap between morphogenesis and genetics

A particularly challenging issue in developmental biology is the integration of genetic networks, cell identity, and cell behavior during embryonic morphogenesis and patterning. The dynamic interplay between morphogens, gene expression, cell proliferation, and tissue growth control is still poorly understood. Most of the imaging tools are now available to address these questions. On one hand, several groups succeeded in imaging morphogen spreading in live embryos (Kicheva et al., 2007; Gregor et al., 2007). On the other hand, genetic networks are being intensively studied in whole embryos, generating very precise data about the dynamics of gene activation and repression in response to morphogens (Isalan et al., 2005; Stathopoulos and Levine, 2005). Furthermore, the ability to image the dynamics of transcription factors binding DNA (Elf et al., 2007), the speed of transcription (Janicki et al., 2004), and chromatin motion (Soutoglou and Misteli, 2007) opens some unexplored areas of integrated imaging in different fields of biology, from molecular biology to embryology. Addressing these questions will require imaging at multiple scales with high temporal resolution. This is the promise for exciting interdisciplinary research and for significant progress towards a more global understanding of biological systems.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Supplemental Video S2C–F.mov

Supplemental Video S2G.mov

Supplemental Video S4D–H.mov

Supplemental Video S5G.mov

Supplemental Video S6A–C.mov

Supplemental Video S6D–F.mov

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Elaine Bearer for providing us with the squid giant axon data used in Fig. 4. We thank Willy Supatto, Thai Truong, and members of the Biological Imaging Center, Beckman Institute at Caltech for discussions and comments. M.L. received support from the Swiss National Science Foundation (Fellowship PA002-111433) and J.V. from the Human Frontier Science Program (HFSP). This work was also supported by a NIH/NICHD grant (PO1HD037105).

References

- Alberts, B, Johnson, A, Lewis, J, Raff, M, Roberts, K, and Walter, P (2002). “Molecular biology of the cell.” Fourth ed., Garland Science, New York, pp. 351–352. [Google Scholar]

- Avvisato, C L, Yang, X, Shah, S, Hoxter, B, Li, W, Gaynor, R, Pestell, R, Tozeren, A, and Byers, S W (2007). “Mechanical force modulates global gene expression and beta-catenin signaling in colon cancer cells.” J. Cell. Sci. 120, 2672–2682 10.1242/jcs.03476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakal, C, Aach, J, Church, G, and Perrimon, N (2007). “Quantitative morphological signatures define local signaling networks regulating cell morphology.” Science 10.1126/science.1140324 316, 1753–1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg, J M, Tymoczko, J L, and Stryer, L (2001). “Biochemistry.” Fifth ed., Freeman, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Betzig, E, Patterson, G H, Sougrat, R, Lindwasser, O W, Olenych, S, Bonifacino, J S, Davidson, M W, Lippincott-Schwartz, J, and Hess, H F (2006). “Imaging intracellular fluorescent proteins at nanometer resolution.” Science 10.1126/science.1127344 313, 1642–1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bewersdorf, J, Pick, R, and Hell, S W (1998). “Multifocal multiphoton microscopy.” Opt. Lett. 23, 655–657 10.1364/OL.23.000655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Born, M, and Wolf, E (1999). “Principles of optics.” 7th (expanded) ed., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K. [Google Scholar]

- Brakenhoff, G J, and Visscher, K (1992). “Confocal imaging with bilateral scanning and array detectors.” J. Microsc. 165, 139–146. [Google Scholar]

- Bray, D (1992). “Cell movements.” Garland, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, C M (2007). “Fluorescence microscopy—avoiding the pitfalls.” J. Cell. Sci. 120, 1703–1705 10.1242/jcs.03433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns, C G, Milan, D J, Grande, E J, Rottbauer, W, MacRae, C A, and Fishman, M C (2005). “High-throughput assay for small molecules that modulate zebrafish embryonic heart rate.” Nat. Chem. Biol. 10.1038/nchembio7321, 263–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, A E (2007). “Image-based chemical screening.” Nat. Chem. Biol. 10.1038/nchembio.2007.153, 461–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecconi, C, Shank, E A, Bustamante, C, and Marqusee, S (2005). “Direct observation of the three-state folding of a single protein molecule.” Science 10.1126/science.1116702 309, 2057–2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu, K K, Lim, D, and Mertz, J (2007). “Enhanced weak-signal sensitivity in two-photon microscopy by adaptive illumination.” Opt. Lett. 10.1364/OL.32.002846 32, 2846–2848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denk, W, Strickler, J H, and Webb, W W (1990). “Two-photon laser scanning fluorescence microscopy.” Science 10.1126/science.2321027 248, 73–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egner, A, Andresen, V, and Hell, S W (2002a). “Comparison of the axial resolution of practical nipkow-disk confocal fluorescence microscopy with that of multifocal multiphoton microscopy: theory and experiment.” J. Microsc. 10.1046/j.1365-2818.2002.01001.x 206, 24–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egner, A, and Hell, S W (2000). “Time multiplexing and parallelization in multifocal multiphoton microscopy.” J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 10.1364/JOSAA.17.001192 17, 1192–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egner, A, Jakobs, S, and Hell, S W (2002b). “Fast 100-nm resolution three-dimensional microscope reveals structural plasticity of mitochondria in live yeast.” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 10.1073/pnas.052545099 99, 3370–3375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elf, J, Li, G W, and Xie, X S (2007). “Probing transcription factor dynamics at the single-molecule level in a living cell.” Science 10.1126/science.1141967 316, 1191–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See EPAPS Document No. E-HJFOA5-2-003803 for supplemental material. This document can be reached through a direct link in the online article’s HTML reference section or via the EPAPS home page (http://www.aip.org/pubservs/epaps.html).

- Farge, E (2003). “Mechanical induction of twist in the drosophila foregut/stomodeal primordium.” Curr. Biol. 10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00576-1 13, 1365–1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forouhar, A S, Liebling, M, Hickerson, A, Nasiraei-Moghaddam, A, Tsai, H J, Hove, J R, Fraser, S E, Dickinson, M E, and Gharib, M (2006). “The embryonic vertebrate heart tube is a dynamic suction pump.” Science 10.1126/science.1123775 312, 751–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, S, and Stern, C (2001). “Tracing the lineage of tracing cell lineages.” Nat. Cell Biol. 10.1038/ncb0901-e216 3, E216–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Cardeña, G, Comander, J, Anderson, K R, Blackman, B R, and Gimbrone, J M A, (2001). “Biomechanical activation of vascular endothelium as a determinant of its functional phenotype.” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 10.1073/pnas.071052598 98, 4478–4485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasser, S M (2002). “Visualizing chromatin dynamics in interphase nuclei.” Science 10.1126/science.1067703 296, 1412–1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf, R, Rietdorf, J, and Zimmermann, T (2005). “Live cell spinning disk microscopy.” Adv. Biochem. Eng./Biotechnol. 95, 57–75 10.1007/b102210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregor, T, Wieschaus, E F, McGregor, A P, Bialek, W, and Tank, D W (2007). “Stability and nuclear dynamics of the bicoid morphogen gradient.” Cell 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.026 130, 141–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith, L G, and Swartz, M A (2006). “Capturing complex 3D tissue physiology in vitro.” Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 211–224 10.1038/nrm1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson, M GL (2005). “Nonlinear structured-illumination microscopy: Wide-field fluorescence imaging with theoretically unlimited resolution.” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 10.1073/pnas.0406877102 102, 13081–13086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson, M GL, Agard, D A, and Sedat, J W (1999). “I5M: 3D widefield light microscopy with better than 100 nm axial resolution.” J. Microsc. 10.1046/j.1365-2818.1999.00576.x 195, 10–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas, P, and Gilmour, D (2006). “Chemokine signaling mediates self-organizing tissue migration in the zebrafish lateral line.” Dev. Cell 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.02.019 10, 673–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haustein, E, and Schwille, P (2007). “Trends in fluorescence imaging and related techniques to unravel biological information.” HFSP J. 10.2976/1.2778852 1, 169–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hell, S W (2007). “Far-field optical nanoscopy.” Science 10.1126/science.1137395 316, 1153–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmchen, F, and Denk, W (2005). “Deep tissue two-photon microscopy.” Nat. Methods 2, 932–940 10.1038/nmeth818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess, S T, Girirajan, T PK, and Mason, M D (2006). “Resolution imaging by fluorescence photoactivation localization microscopy.” Biophys. J. 91, 4258–4272 10.1529/biophysj.106.091116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hirose, Y, Varga, Z M, Kondoh, H, and Furutani-Seiki, M (2004). “Single cell lineage and regionalization of cell populations during medaka neurulation.” Development 10.1242/dev.010694 131, 2553–2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hove, J R, Köster, R W, Forouhar, A S, Acevedo-Bolton, G, Fraser, S E, and Gharib, M (2003). “Intracardiac fluid forces are an essential epigenetic factor for embryonic cardiogenesis.” Nature 10.1038/nature01282 421, 172–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huisken, J, Swoger, J, Del Bene, F, Wittbrodt, J, and Stelzer, E H K (2004). “Optical sectioning deep inside live embryos by selective plane illumination microscopy.” Science 10.1126/science.1100035 305, 1007–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isalan, M, Lemerle, C, and Serrano, L (2005). “Engineering gene networks to emulate Drosophila embryonic pattern formation.” PLoS Biol. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030064 3, e64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe, L F, and Créton, R (1998). “On the conservation of calcium wave speeds.” Cell Calcium 10.1016/S0143-4160(98)90083-5 24, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janicki, S M, Tsukamoto, T, Salghetti, S E, Tansey, W P, Sachidanandam, R, Prasanth, K V, Ried, T, Shav-Tal, Y, Bertrand, E, Singer, R H, and Spector, D L (2004). “From silencing to gene expression: real-time analysis in single cells.” Cell 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00171-0 116, 683–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, E AV, Baron, M H, Fraser, S E, and Dickinson, M E (2004). “Measuring hemodynamic changes during mammalian development.” Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 287, H1561–H1569 10.1152/ajpheart.00081.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kam, Z, Hanser, B, Gustafsson, M G L, Agard, D A, and Sedat, J W (2001). “Computational adaptive optics for live three-dimensional biological imaging.” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 10.1073/pnas.071275698 98, 3790–3795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller, P J, Pampaloni, F, and Stelzer, E H (2007). “Three-dimensional preparation and imaging reveal intrinsic microtubule properties.” Nat. Methods 4, 843–846 10.1038/nmeth1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kicheva, A, Pantazis, P, Bollenbach, T, Kalaidzidis, Y, Bittig, T, Julicher, F, and Gonzalez-Gaitan, M (2007). “Kinetics of morphogen gradient formation.” Science 10.1126/science.1135774 315, 521–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski, C, Srayko, M, and Nedelec, F (2007). “Cortical microtubule contacts position the spindle in c. elegans embryos.” Cell 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.027 129, 499–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulesa, P M, and Fraser, S E (2000). “In ovo time-lapse analysis of chick hindbrain neural crest cell migration shows cell interactions during migration to the branchial arches.” Development 127, 1161–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulesa, P M, and Fraser, S E (2002). “Cell dynamics during somite boundary formation revealed by time-lapse analysis.” Science 10.1126/science.1075544 298, 991–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtman, J W, and Conchello, J A (2005). “Fluorescence microscopy.” Nat. Methods 2, 910–919 10.1038/nmeth817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebling, M, Forouhar, A S, Gharib, M, Fraser, S E, and Dickinson, M E (2005). “Four-dimensional cardiac imaging in living embryos via postacquisition synchronization of nongated slice sequences.” J. Biomed. Opt. 10.1117/1.2061567 10, 054001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebling, M, Forouhar, A S, Wolleschensky, R, Zimmermann, B, Ankerhold, R, Fraser, S E, Gharib, M, and Dickinson, M E (2006). “Rapid three-dimensional imaging and analysis of the beating embryonic heart reveals functional changes during development.” Dev. Dyn. 10.1002/dvdy.20926 235, 2940–2948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livet, J, Weissman, T A, Kang, H, Draft, R W, Lu, J, Bennis, R A, Sanes, J R, and Lichtman, J W (2007). “Transgenic strategies for combinatorial expression of fluorescent proteins in the nervous system.” Nature 10.1038/nature06293 450, 56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucitti, J L, and Dickinson, M E (2006). “Moving toward the light: Using new technology to answer old questions.” Pediatr. Res. 10.1203/01.pdr.0000220318.49973.32 60, 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathis, L, Kulesa, P M, and Fraser, S E (2001). “EGF receptor signalling is required to maintain neural progenitors during hensen’s node progression.” Nat. Cell Biol. 10.1038/35078535 3, 559–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megason, S G, and Fraser, S E (2007). “Imaging in systems biology.” Cell 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.031 130, 784–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray, J M, Appleton, P L, Swedlow, J R, and Waters, J C (2007). “Evaluating performance in three-dimensional fluorescence microscopy.” J. Microsc. 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2007.01861.x 228, 390–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neil, M AA, Juškaitis, R, and Wilson, T (1997). “Method of obtaining optical sectioning by using structured light in a conventional microscope.” Opt. Lett. 22, 1905–1907 10.1364/OL.22.001905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols, J T, Miyamoto, A, and Weinmaster, G (2007). “Notch signaling–constantly on the move.” Traffic 8, 959–969 10.10111/j.1600-0854.2007.00592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niesner, R, Andresen, V, Neumann, J, Spiecker, H, and Gunzer, M (2007). “The power of single and multibeam two-photon microscopy for high-resolution and high-speed deep tissue and intravital imaging.” Biophys. J. 10.1529/biophysj.106.102459 93, 2519–2529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama, M, Higuchi, H, and Yanagida, T (2002). “Chemomechanical coupling of the forward and backward steps of single kinesin molecules.” Nat. Cell Biol. 10.1038/ncb857 4, 790–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka, S, Tanaka, Y, Okada, Y, Takeda, S, Harada, A, Kanai, Y, Kido, M, and Hirokawa, N (1998). “Randomization of left-right asymmetry due to loss of nodal cilia generating leftward flow of extraembryonic fluid in mice lacking KIF3B motor protein.” Cell 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81705-5 95, 829–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka, S, Tanaka, Y, Okada, Y, Takeda, S, Harada, A, Kanai, Y, Kido, M, and Hirokawa, N (1999). “Erratum.” Cell 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80067-7 99, 116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmeirim, I, Henrique, D, Ish-Horowicz, D, and Pourquié, O (1997). “Avian hairy gene expression identifies a molecular clock linked to vertebrate segmentation and somitogenesis.” Cell 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80451-1 91, 639–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, S F, and Salmon, E D (1997). “Microtubule assembly in clarified xenopus egg extracts.” Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 36, 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepperkok, R, and Ellenberg, J (2006). “High-throughput fluorescence microscopy for systems biology.” Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 690–696 10.1038/nrm1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter, S M (1996). “Vital imaging: Two photons are better than one.” Curr. Biol. 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)70782-3 6, 1595–1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabut, G, and Ellenberg, J (2004). “Automatic real-time three-dimensional cell tracking by fluorescence microscopy.” J. Microsc. 10.1111/j.0022-2720.2004.01404.x 216, 131–137. Part 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racine, V, Sachse, M, Salamero, J, Fraisier, V, Trubuil, A, and Sibarita, J B (2007). “Visualization and quantification of vesicle trafficking on a three-dimensional cytoskeleton network in living cells.” J. Microsc. 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2007.01723.x 225, 214–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueckel, M, Mack-Bucher, J A, and Denk, W (2006). “Adaptive wavefront correction in two-photon microscopy using coherence-gated wavefront sensing.” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 10.1073/pnas.0604791103 103, 17137–17142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rust, M J, Bates, M, and Zhuang, X W (2006). “Sub-diffraction-limit imaging by stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (storm).” Nat. Methods 3, 793–795 10.1038/nmeth929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satpute-Krishnan, P, DeGiorgis, J A, Conley, M P, Jang, M, and Bearer, E L (2006). “A peptide zipcode sufficient for anterograde transport within amyloid precursor protein.” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 10.1073/pnas.0607527103 103, 16532–16537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherz, P, Huisken, J, Sahai-Hernandez, P, and Stainier, D (2008). “High speed imaging of developing heart valves reveals interplay of morphogenesis and function.” Development 10.1242/dev.010694 135, 1179–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisson, J H, Stoner, J A, Ammons, B A, and Wyatt, T A (2003). “All-digital image capture and whole-field analysis of ciliary beat frequency.” J. Microsc. 10.1046/j.1365-2818.2003.01209.x 211, 103–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soutoglou, E, Dorn, J F, Sengupta, K, Jasin, M, Nussenzweig, A, Ried, T, Danuser, G, and Misteli, T (2007). “Positional stability of single double-strand breaks in mammalian cells.” Nat. Cell Biol. 10.1038/ncb1591 9, 675–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soutoglou, E, and Misteli, T (2007). “Mobility and immobility of chromatin in transcription and genome stability.” Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 17, 435–442 10.1016/j.gde.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkuviene, V, and Pepperkok, R (2007). “The potential of high-content high-throughput microscopy in drug discovery.” Br. J. Pharmacol. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707346 152, 62–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stathopoulos, A, and Levine, M (2005). “Genomic regulatory networks and animal development.” Dev. Cell 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.09.005 9, 449–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stelzer, E HK (1998). “Contrast, resolution, pixelation, dynamic range and signal-to-noise ratio: fundamental limits to resolution in fluorescence light microscopy.” J. Microsc. 10.1046/j.1365-2818.1998.00290.x 189, 15–24. Part 1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Supatto, W, Débarre, D, Moulia, B, Brouzés, E, Martin, J-L, Farge, E, and Beaurepaire, E (2005). “In vivo modulation of morphogenetic movements in drosophila embryos with femtosecond laser pulses.” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 10.1073/pnas.0405316102 102, 1047–1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surrey, T, Nedelec, F, Leibler, S, and Karsenti, E (2001). “Physical properties determining self-organization of motors and microtubules.” Science 10.1126/science.1059758 292, 1167–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swedlow, J, Sedat, J, and Agard, D (1997). “Deconvolution in optical microscopy.” Second ed., Academic, San Diego. [Google Scholar]

- Tadrous, P J (2000). “Methods for imaging the structure and function of living tissues and cells. 3: confocal microscopy and micro-radiology.” J. Pathol. 191, 345–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallini, N, Ohkura, M, Choi, B-R, Ji, G, Imoto, K, Doran, R, Lee, J, Plan, P, Wilson, J, Xin, H-B, Sanbe, A, Gulick, J, Robbins, J, Salama, G, Nakai, J, and Kotlikoff, M (2006). “Imaging cellular signals in the heart in vivo: cardiac expression of the high signal Ca2+ indicator GCaMP2.” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 10.1073/pnas.0509378103 103, 4753–4758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaami, T, Otsuki, S, Tomosada, N, Kosugi, Y, Shimizu, M, and Ishida, H (2002). “High-speed 1-frame∕ms scanning confocal microscope with a microlens and nipkow disks.” Appl. Opt. 10.1364/AO.41.004704 41, 4704–4708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomann, D, Dorn, J, Sorger, P, and Danuser, G (2003). “Automatic fluorescent tag localization. II: improvement in super-resolution by relative tracking.” J. Microsc. 211, 230–248 10.1046/j.1365-2818.2003.01223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verveer, P J, Swoger, J, Pampaloni, F, Greger, K, Marcello, M, and Stelzer, E H (2007). “High-resolution three-dimensional imaging of large specimens with light sheet-based microscopy.” Nat. Methods 4, 311–313 10.1038/nmeth1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vonesch, C, Aguet, F, Vonesch, J L, and Unser, M (2006). “The colored revolution of bioimaging.” IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 10.1109/MSP.2006.1628875 23, 20–31. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, T, ed. (1990). “Confocal microscopy.” Academic Press, London. [Google Scholar]

- Wolleschensky, R, Zimmermann, B, and Kempe, M (2006). “High speed confocal fluorescence imaging with a novel line scanning microscope.” J. Biomed. Opt. 10.1117/1.2402110 11, 064011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuite, G J, Smith, S B, Young, M, Keller, D, and Bustamante, C (2000). “Single-molecule studies of the effect of template tension on T7 DNA polymerase activity.” Nature 10.1038/35003614 404, 103–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G, Houghtaling, B R, Gaetz, J, Liu, J Z, Danuser, G, and Kapoor, T M (2007). “Architectural dynamics of the meiotic spindle revealed by single-fluorophore imaging.” Nat. Cell Biol. 10.1038/ncb1643 9, 1233–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamir, E A, Czirok, A, Cui, C, Little, C D, and Rongish, B J (2006). “Mesodermal cell displacements during avian gastrulation are due to both individual cell-autonomous and convective tissue movements.” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 10.1073/pnas.0606100103 103, 19806–19811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Video S2C–F.mov

Supplemental Video S2G.mov

Supplemental Video S4D–H.mov

Supplemental Video S5G.mov

Supplemental Video S6A–C.mov

Supplemental Video S6D–F.mov