Abstract

Gene activation in eukaryotes involves the concerted action of histone tail modifiers, chromatin remodelers, and transcription factors, whose precise coordination is currently unknown. We demonstrate that the experimentally observed interactions of the molecules are in accord with a kinetic proofreading scheme. Our finding could provide a basis for the development of quantitative models for gene regulation in eukaryotes based on the combinatorical interactions of chromatin modifiers.

How genes are activated in eukaryotic genomes is not yet fully understood, but it is becoming increasingly clear that the modulation of chromatin structure plays a crucial role. There is mounting experimental evidence that a strong correlation exists between histone tail modifiers, nucleosome remodelers, and transcription factors (Strahl and Allis, 2002; Horn and Peterson, 2002; Schreiber and Bernstein, 2002; Cosgrove et al. 2004; Lue, 2005; Giresi et al., 2006). A quantitative (i.e., mathematical) description of the how these factors combine to address and activate genes is not presently available; but many qualitative models have been and are being deduced from experimental observations, as to be found in the above cited papers. Clearly, the three kinds of molecules known to intervene in chromatin regulation can be combined in various ways, and a specific experimental context may hide an underlying scheme in details specific to this particular biological model.

Our intention in this paper is twofold: (i) to present a mechanism which may play a relevant role in the orchestration of chromatin regulators; and (ii) to postulate a model which is sufficiently quantitative to validate or rule out some of the experimentally proposed scenarios. Motivated by experimental findings but abstracting from them, we have observed that the combined action of histone tail modifiers, chromatin remodelers, and transcription factors allows for a kinetic proofreading scheme much akin to the originally proposed scheme (Hopfield, 1974), as we describe below. In the context of chromatin remodeling, such a scheme would allow to discriminate “right” from “wrong” genes to be activated for transcription at a pretranscriptional level.

ANALYSIS

Starting point for our model is the sequence of actions

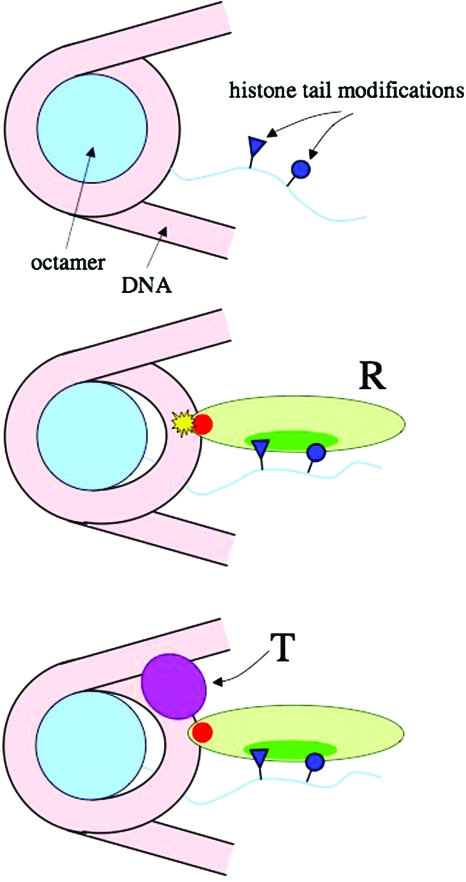

as displayed schematically in Fig. 1. Throughout this paper we focus on acetylated nucleosomes, but this is no restriction; in reality much more complex histone tail modifications may be involved, and they can likewise be integrated into our model.

Figure 1. The sequence of regulatory events supposed in our model (schematic).

Top: nucleosome with one histone tail carrying amino acid modifications. Middle: recruitment of a remodeling complex (R) with a histone modifier recognition unit (dark green) and the ATP-active domain (red). The DNA is partially loosened from the histone octamer. Bottom: recruitment of a transcription factor (T).

The sequence of activation steps we selected represents one example of several schemes discussed in the literature. It corresponds essentially to the scenario of Fig. 1(C) in Eberharter et al. (2005), with the difference that we have placed the transcription factor at the end of the gene activation process; we comment on this difference at the end of the paper. For simplicity we only consider a two-state case, a fully acetylated and a fully deacetylated nucleosome.

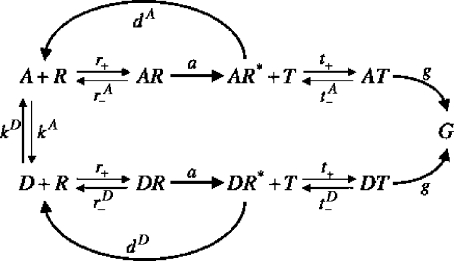

The overall reaction scheme we propose is presented in Fig. 2.

Figure 2. Kinetic proofreading scheme for the regulation of transcription initiation in chromatin.

Each kinetic proofreading scheme is based on equilibrium and nonequilibrium reactions (Eberharter et al., 2005). For chromatin, the equilibrium step is provided by the association of an acetylated nucleosome of concentration [A] with a remodeler [R] via the reaction [A]+[R]↔[AR] with the on rate r+ and the off-rate . Second, we assume that the kinetics of the nonequilibrium remodeling reaction is governed by the scheme [AR]↔[AR*]→[A]+[R] with reaction rates a and dA, respectively. The ∗− symbol indicates the activated, let’s say more mobile nucleosome. Here, a and dA are the rates of nucleosome activation and of dissociation of the activated complex, respectively. The main input for postulating these two reactions is the knowledge that chromatin remodelers in general have different domains interacting with tail modifications and allowing for the processing of ATP (adenosine 5′-triphosphate). ATP is involved in our scheme both in fueling the nucleosomal mobility and in the proofreading discrimination mechanism.

In a quasisteady state assumption, the ratio of concentrations of activated and nonactivated nucleosomes is given by [AR*]∕[AR]=a∕dA. In the final step, a transcription factor T can associate itself with the activated nucleosome with the reaction [AR*]+[T]↔[AT] with on-rate t+ and off-rate .

For the deactylated nucleosome of concentration [D] we postulate a corresponding set of reactions (see Fig. 2) with the same on-rates r+ and t+ for binding of the remodeler and the transcription factor as for the acetylated complex. Also, the rate a for the remodeling reaction is the same. However, we assume that the off rates are different and indicate those of the deacetylated complex by an upper index D, , dD, and , as compared to the rates , dA, and of the acetylated nucleosome.

As a measure of the efficiency of the proofreading scheme we consider the rate of formation of the final product, the accessibility of the readout gene G. For the acetylated case we assume this to be [AT]g and for the deacetylated case [DT]g, cf. Fig. 2. We thus have to evaluate the ratio

| (1) |

Here, in the last step, the kinetics for the formation of the acetylated complex has been added, cf. Fig. 2. Equation 1 is our central result. It describes the discrimination power of nucleosome activation associated with two different histone-modified states.

The discrimination of the acetylated state A and the deacetylated state D would be relatively small if it would rely only on the simple difference ΔUT in binding energies of the transcription factor. Suppose that this affects its off rates as

| (2) |

Then the ratio R=[AT]∕[DT] acquires a factor exp(ΔUT∕kBT). This factor alone would usually be not sufficient for discrimination.

The main effect of the proposed scheme lies in the recruitment of the remodeler and the nonequilibrium reaction, as is common for the kinetic proofreading scheme. We have

| (3) |

and

| (4) |

where ΔUR denotes the energetic difference between the acetylated and deacetylated nucleosome-remodeler complexes. This means that the remodeling step leads to an extra factor exp(2ΔUR∕kBT) for the ratio R=[AT]∕[DT], Eq. 1. Combining these expressions we find

Suppose one has only moderate effects of the acetylation on the binding energies, e.g., ΔUT=ΔUR=2kBT. Then we find nevertheless that the expression level of the acetylated region as compared to that of the deacetylated is dramatically enhanced by a factor exp(2UR+ΔUR)∕kBT≈400. Without the remodeling step, however, one would only have exp(ΔUT∕kBT)≈7.

APPLICATION TO THE RSC REMODELING SYSTEM

We finally confront our model with recently obtained experimental results on the remodels the structure of chromatin (RSC) chromatin remodeling complex in yeast (S. cerevisiae). This complex is an especially well-characterized remodeling system to which a variety of techniques from molecular biology, biochemistry, single-molecule analysis, and electron microscopy have been applied, particularly by the Kornberg and Cairns groups (Asturias et al., 2002; Saha et al., 2002; Kasten et al., 2004; Chai et al., 2005; Leschziner et al., 2007). Since structural knowledge of the remodeler-nucleosome interaction is becoming available recently (Asturias et al. 2002; Leschziner et al., 2007) we expect that an integrated model combining the effects of enzymatic modifications and the mechanistic aspects of chromatin remodeling may become available in the near future for this exemplary case.

A recent detailed biochemical analysis of the role of histone tail aceylation in chromatin remodeling in this system studied the interaction between the Rsc4 tandem bromodomain and the histone H3 tail acetylated at lysine 14 (Kasten et al., 2004). The authors studied in particular the role of bromodomain modifications and H3 Lys 14 substitutions. The authors considered their findings paradoxical: the presence of functional bromodomains turned out to be essential, while Lys 14 – acetylation was not, since substituted H3 Lys14 were viable. Two interpretations were offered for this result: (i) Rsc4 bromodomain mutants may have a reduced binding interaction with both Lys 14 and flanking residues, so that acetylation at H3 Lys 14 may be needed for a sufficient binding level; (ii) Rsc4 bromodomains may bind two different targets on the nucleosome, one of which being H3 Lys 14Ac while the other is unknown. Both targets then together should provide sufficient binding energy.

We believe that these findings are much simpler to explain in the context of our model. The explanations of the authors of the study rely on the equilibrium binding energy of the remodeler only. It is clear from our model derived in the previous section that the main contribution in discrimination is due to the presence of the remodeling step, while changes in mere equilibrium binding matter considerably less. Therefore, the experimental observation can easily be interpreted by noting that the changes in binding energy due to the mutations brings the discrimination ratio minimally down for the mutant case, while the remodeling step itself still remains intact, and hence the cells viable.

The fact that also in the case of H3 Lys 14 substitutions cells are still viable (for the intact remodeler) raises the interesting question whether discrimination between acetylated and deacetylated nucleosomes is really crucial. But if the bromodomains in the absence of Lys 14 bind to other acetylated lysines as alternative targets, then a rather high discrimination ratio can still be achieved, again due to the presence of the remodeling step.

A fully quantitative application (and thereby validation) of our model necessitates a more complete knowledge of both the intervening molecular partners and their reaction rates, however, even in the absence of such knowledge it already puts constraints on the comparison of alternative scenarios. As such, it may also guide experimentation towards a verification of particular remodeling schemes.

DISCUSSION

The kinetic proofreading scenario for chromatin remodeling presented here shows that chromatin remodeling based on histone tail modifiers, chromatin remodelers, and transcription factors allows to discriminate right from wrong genes to be activated. While in our example we have distinguished between an acetylated versus a deacetylated state, other covalent modifications and their combinations [the “histone code,” (Strahl and Allis, 2000)] can clearly be included since their presence affects the off-rates kD, , dD and . For each existing gene/promoter there is a combination of remodeling events which promotes gene access with the highest possible discrimination. We further stress that how these factors are scheduled is less essential: note that the final result Eq. 1 does not change if the transcription factor is placed at the start of the initiation process. Finally, we note that eukaryotic transcriptional activation usually involves a large number of transcription factors and gene regulatory proteins. Any component that is sensitive to histone modifications constitutes an additional factor in the discrimination power of Eq. 1. The coupling of a remodeling step to any of those components, as exemplified above in our paper, leads to a dramatically increased sensitivity of that component to histone modifications.

References

- Asturias, F J, Chung, W H, Kornberg, R D, and Lorch, Y (2002). “Structural analysis of the RSC chromatin-remodeling complex.” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 10.1073/pnas.162504299 99, 13477–13480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai, B, Huang, J, Cairns, B R, and Laurent, B C (2005). “Distinct roles for the RSC and Swi/Snf ATP-dependent chromatin remodelers in DNA double-strand break repair.” Genes Dev. 10.1101/gad.1273105 19, 1656–1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove, M S, Boeke, J D, and Wolberger, C (2004). “Regulated nucleosome mobility and the histone code.” Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 10.1038/nsmb851 11, 1037–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberharter, A, Ferreira, R, and Becker, P (2005). “Dynamic chromatin: concerted nucleosome remodeling and acetylation.” Biol. Chem. 10.1515/BC.2005.087 386, 745–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giresi, P G, Gupta, M, and Lieb, J D (2006). “Regulation of nucleosome stability as a mediator of chromatin function.” Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 10.1016/j.gde.2006.02.003 16, 171–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopfield, J J (1974). “Kinetic proofreading: a new mechanism for reducing errors in biosynthetic processes requiring high specificity.” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 10.1073/pnas.71.10.4135 71, 4135–4139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn, P J, and Peterson, C L (2002). “Chromatin higher-order folding: wrapping up transcription.” Science 10.1126/science.1074200 297, 1824–1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasten, M, Szerlong, H, Erdjument-Bromage, H, Tempst, P, Werner, M, and Cairns, B R (2004). “Tandem bromodomains in the chromatin remodeler RSC recognize acetylated histone H3 Lys 14.” EMBO J. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600143 23, 1348–1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leschziner, A E, Saha, A, Wittmeyer, J, Zhang, Y, Bustamante, C, Cairns, B R, and Nogales, E (2007). “Conformational flexibility in the chromatin remodeler RSC observed by electron microscopy and the orthogonal tilt reconstruction method.” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 10.1073/pnas.0700706104 104, 4913–4918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lue, N F (2005). “Chromatin remodeling.” Sci. STKE 294, tr20. 10.1126/stke.2942005tr20 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Saha, A, Wittmeyer, J, and Cairns, B R (2002). “Chromatin remodeling by RSC involves ATP-dependent DNA translocation.” Genes Dev. 10.1101/gad.995002 16, 2120–2134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber, S L, and Bernstein, B E (2002). “Signaling network model of chromatin.” Cell 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)01196-0 111, 771–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strahl, B D, and Allis, C D (2000). “The language of covalent histone modifications.” Nature (London) 10.1038/47412 403, 41–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]