Abstract

We have characterized the antibody-antigen binding events of the prion protein (PrP) utilizing three new PrP-specific monoclonal antibodies (Mabs). The degree of immunoreactivity was dependent on the denaturation treatment with the combination of heat and SDS resulting in the highest levels of epitope accessibility and antibody binding. Interestingly however, this harsh denaturation treatment was not sufficient to completely and irreversibly abolish protein conformation. The Mabs differed in their PrP epitopes with Mab 08-1/11F12 binding in the region of PrP93–122, Mab 08-1/8E9 reacting to PrP155–200 and Mab 08-1/5D6 directed to an undefined conformational epitope. Using normal and infected brains from hamsters, sheep and deer, we demonstrate that the binding of PrP to one Mab triggers PrP epitope unmasking, which enhances the binding of a second Mab. This phenomenon, termed positive immunocooperativity, is specific regarding epitope and the sequence of binding events. Positive immunocooperativity will likely increase immunoassay sensitivity since assay conditions for PrPSc detection does not require protease digestion.

Keywords: Prion protein, Monoclonal antibodies, Epitope recognition, Immunocooperativity

1. Introduction

Prion diseases, also known as transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs), are invariably fatal neurodegenerative disorders affecting a broad spectrum of host species and arise via genetic, infectious, or sporadic mechanisms. In humans, prion diseases consist of various forms of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (sporadic, familial, iatrogenic, variant), Gerstmann-Straussler-Scheinker syndrome, Kuru and Fatal Familial Insomnia Prion diseases in animals include scrapie in sheep, bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) in cattle and chronic wasting disease (CWD) in deer and elk. (Glatzel et al., 2003; Collins et al., 2004; Prusiner, 1998; Abid and Soto, 2006; Wadsworth and Collinge, 2007)

Regardless of the data supporting or refuting the prion (Prusiner, 1982), virino (Dickinson and Outram, 1988) and virus (for review see Manuelidis, 2007) theories of the nature of the infectious agent, a key event in prion diseases is the accumulation of an abnormal isoform (PrPSc) of a host-encoded protein, termed prion protein (PrPC), predominantly in the nervous system of the infected host (Stahl et al., 1993). Structurally, PrP consists of a disordered, flexible amino terminal region comprising approximately residues 23–124 and a globular carboxyl terminal domain (approximately residues 125–231). The carboxyl terminal region is directly associated with the formation of fibrils and aggregates associated with the disease. The amino terminal region is involved in protein structural stability and the folding of PrPC to PrPSc (Cordeiro et al., 2005). PrPC and PrPSc differ in their sensitivities to proteinase K (PK) with PrPC being completely digested and PrPSc converted to a protease resistant core (PrP27-30) comprising approximately the PrP residues 90–231. PrPC and PrPSc also differ in their secondary and tertiary structures (Basler et al., 1986; Caughey et al., 1991; Stahl and Prusiner, 1991; Caughey and Raymond, 1991; Pan et al., 1993; Kocisko et al., 1994; 1995). Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) and circular dichroism spectroscopy studies indicate that PrPC is highly helical (42%) with little β-sheet structure (3%) (Pan et al., 1993). In contrast, PrPSc contains less helical structure (30%) and a large amount of β-structure (43%). PrPC can be converted to the lethal PrPSc conformation on contact with PrPSc(Horiuchi and Caughey, 1999; Safar et al., 1998; Caughey, 2001). Several mechanisms have been proposed for the spontaneous and/or assisted conversion of endogenous PrPC to PrPSc (Caughey, 2001). A confounding factor in conversion is that PrPSc is conformationally heterogeneous (Cohen and Prusiner, 1998) which suggests a degree of structural flexibility.

PrPSc represents the only disease-specific macromolecule identified to date, and the majority of testing procedures are based on the proteolytic removal of endogenous PrPC followed by the immunological detection of PrPSc. The degree of resistance of PrPSc to proteolysis is likely related to the amount of PK used for digestion as well as factors associated with PrPSc including concentration, state of aggregation, unique conformation and other molecules. Such assays become problematic when PrPSc is present only in low amounts as the enzyme may digest it. On the other hand, it is important to use sufficient PK to digest all of the PrPC that is present to eliminate the possibility of false positive results. Confounding this issue is the concept of PK-sensitive PrPSc (sPrPSc) (Safar et al., 1998) that has been reported to constitute the majority of PrPSc in the brains of individuals who had died from CJD (Safar et al., 2005). Therefore, the use of PK likely results in an underestimate of the total PrPSc present in a sample. This becomes an important issue in the development of a prion disease-specific ante-mortem assay using biological fluids where the levels of PrPSc are presumably very low. The development of diagnostic assays that do not require proteolytic treatment of samples would eliminate the issues associated with proteolytic digestion and reduced assay sensitivity.

Molecular dynamic simulations provide information about the conversion process as well as possible PrPSc models and illustrate the complexities involved in the conversion of PrP and in developing diagnostics for PrPSc (Alonso et al., 2001; 2002). In extreme examples the surface of one form of the protein can change dramatically so that epitopes found in one form of PrP are unavailable for binding in another form (e.g., the monoclonal antibody [Mab] 3F4 epitope is less accessible in the PrPSc form; Peretz et al., 1997).

Furthermore, previous studies have shown that the binding of an antibody specific for the N terminus of PrPC can block the recognition of another antibody that normally binds to a conformational epitope located within the C terminus. It is likely that the binding of the first antibody causes a specific, but subtle, conformational change within the C terminus resulting in a loss or masking of the epitope of the second antibody (Li et al., 2000). This concept, which we refer to as negative immunocooperativity, describes the loss of antibody binding to its epitope resulting from a change in the antigen which was induced by the initial binding of a different antibody to its specific epitope.

In this paper, we describe dynamic antibody-antigen interactions resulting in positive prion protein immunocooperativity. We hypothesize that this event consists of PrPSc spatial rearrangement, which may also be associated with non-PrP macromolecular denaturation, resulting in PrP epitope unmasking. This finding has important implications for PrP structural analysis, detection of PrPSc without proteolysis resulting in enhancing PrPSc assay sensitivity, and targeting specific PrP sites for therapeutics.

2. Materials and Methods

Animals and TSE Agents

Hamster-adapted scrapie strain 263K was originally obtained from Dr. Richard Kimberlin (SARDAS, Edinburgh, Scotland) and the ME7 mouse-adapted scrapie strain was originally supplied by Dr. Alan Dickinson (ARC and MRC Neuropathogenesis Unit, Edinburgh, Scotland). Both of these scrapie strains were provided by Dr. Richard Carp (NYS Institute for Basic Research, Staten Island, NY). Strains ME7 and 263K were used to infect CD-1 mice and LVG/LAK hamsters (Charles River Breeding Laboratories, Wilmington, MA, USA), respectively. Preparation of inoculum, injection and sacrificing of animals were performed as previously described (Carp and Callahan, 1981; Carp et al., 1990). The mice were observed daily to detect the onset and progression of clinical signs. Behavioral analysis included evaluation for posture, balance, coordination, and the presence of tremors. Brains from sheep infected with scrapie and white-tailed deer infected with CWD were harvested at the time of clinical disease and frozen at −80o C. Brains from uninfected animals were similarly harvested and frozen.

Generation of Monoclonal Antibodies

PK-treated PrPSc, which consists of the core protein containing amino acids (aa) 90–231 (PrP90–231), was isolated from the brains of 263K infected hamsters using a procedure originally reported by Hilmert and Diringer (1984) and modified by Rubenstein et al. (1994). This material was solubilized using guanidine hydrochloride extraction and methanol precipitation as previously described (Kang et al., 2003) and used as the immunogen. PrP−/− mice were immunized and their immune responses monitored by ELISA as previously described (Kascsak et al, 1987). One of the immunized mice was used to produce hybridomas. The mouse received a final immunization of antigen by the intravenous route in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) 4 days before fusion. Spleen cells were fused to an SP2/0 myeloma cell line expressing reduced levels of cell surface PrPC (Kim et al., 2003). The hybridomas were screened by ELISA as previously described (Kascsak et al., 1987) and the resulting cells were cloned three times by limiting dilution. Large scale Mab production was carried out using disposable bioreactor flasks (Integra Biosciences, Switzerland) and antibody was purified from media using protein G immunoaffinity chromatography (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Protein was determined by the micro BCA protein assay (Pierce) and isotyping was performed using the mouse monoclonal antibody isotyping kit (Pierce). Each of the Mabs was biotinylated using the EZ-link biotinylation kit (Pierce).

Immunoassays

For the preparation of 10% brain homogenates, brain tissues were homogenized in 10 vol. of ice-cold lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Igepal CA-630 (Nonidet P-40), 0.5% deoxycholate, 5 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) in the presence of 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) (if the homogenate was to be treated with PK, PMSF was omitted from the lysis buffer). After centrifugation at 1,000 x g for 10 min, the supernatants were aliquoted and stored at −80° C.

For the indirect ELISA, brain homogenates were centrifuged at 1,000 x g for 2 min. Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) was added to 1 ml of the supernatants to a final concentration of 1%, heated at 100° C for 10 min and centrifuged at 16,000 x g for 5 min. The supernatants were diluted 10-fold in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and added to 96-well Costar microtiter plates in a volume of 100 μl per well. After incubation overnight at 4°C, the wells were emptied and washed three times with PBST (PBS containing 0.2% Tween 20). Primary antibodies were diluted to 5 μg/ml, 100 μl is added per well, and the plates were incubated at room temperature for 60 min. The wells were then washed three times with PBST. One hundred microliters (1:1000) of goat anti-mouse lgG (Fab fragments) conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (Sigma Chemical Co.) was added to each well and incubated at room temperature for 60 min. The wells were washed three times with PBST followed by the addition of 100 μl PNPP (4-Nitrophenyl phosphate disodium salt hexahydrate, Sigma) substrate solution. The OD405 was measured after a 37o C incubation for 60 min.

For the capture ELISA assay, 96-well plates were coated with affinity-purified capture Mab (5 μg/ml) at room temperature for 2–3 hrs. The coated wells were blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin (Sigma) in PBS overnight at 4° C. The wells were washed three times with PBST. The antigen was either non-PK or PK (100 μg/ml PK at 50 °C for 30 min) treated brain lysates to which was added a final concentration of 1% PMSF. All samples were treated with 1% SDS (final concentration), heated at 100o C for 10 min. and centrifuge at 16,000 x g for 5 min. The supernatants were diluted 10-fold and 100 μl was added to each well. The plates were incubated at 37o C for 1 hr. The wells were washed three times with PBST and 100 μl of the biotinylated detector antibody (5 μg/ml) was added. After 60 min the wells were washed with PBST and 100 μl streptavidin conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (!:5,000) was added for 60 min at 37o C. PNPP (4-Nitrophenyl phosphate disodium salt hexahydrate) (Sigma) substrate solution was added to each well (100 μl) and after 60 min, product was measured with an ELISA reader (Bio-Tek, Vermont, NY) at OD405.

In experiments where samples were eluted for Western blot analysis, following the incubation of detection Mab, 1% SDS (final concentration) was added to the wells followed by heating at 100o C for 10 min.

Western Blotting

Ten percent brain homogenates were prepared in lysis buffer as described above. Proteins were subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) using 12% acrylamide gels, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and immunostained using either streptavidin-conjugated to alkaline phosphatase with NBT and BCIP as the substrate (Kascsak et al., 1986) or horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Pierce) with super signal west femto maximum sensitivity substrate (Pierce) as previously described (LaFauci et al., 2006). For samples that were PK digested prior to SDS-PAGE, treatment involved incubation with 100 μg/ml PK for 30 min at 50o C followed by the addition of 1% PMSF, 1X SDS-PAGE sample buffer and heating at 100o C for 5 min.

3. Results

Numerous Mabs were generated using the solubilized PrPSc as immunogen and the low PrP expressing SP2/0 myeloma cell line. Three of these Mabs, 08-1/5D6 (5D6), 08-1/11F12 (11F12) and 08-1/8E9 (8E9) were selected for this study and have been isotyped as IgG1, IgG2b and IgG2b respectively. Mapping studies indicated that 5D6 reacts with an, as yet, undefined PrP~90–231-specific conformational epitope while 11F12 binds to a region of PrP spanning aa 93–122 and 8E9 reacts within the region of aa 155–200. Individually, all three Mabs react with both the normal and disease associated PrP isoforms.

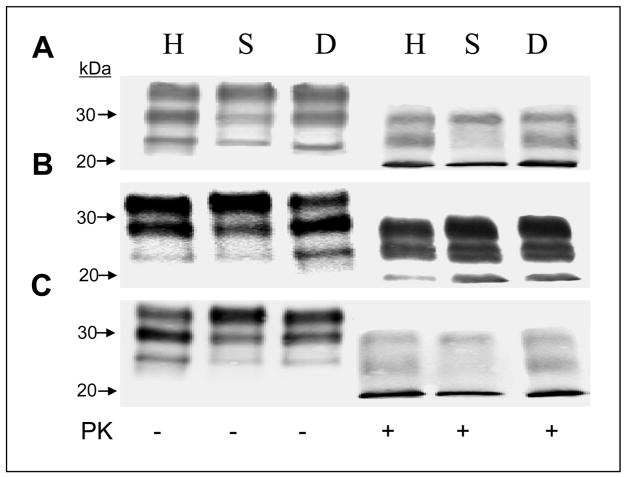

Western blotting of total brain lysates (Figure 1) demonstrated that all three Mabs were reactive against PrP from non-protease treated brain samples and PK-treated PrPSc from 263K-infected hamsters, scrapie-infected sheep and CWD-infected deer (Figure 1). Similar results were observed using untreated and PK-treated partially purified PrPSc preparations (data not shown). These Mabs were also immunoreactive against the normal and abnormal PrP isoforms and PK-treated PrPSc isolated from mouse brains infected with the ME7, 139A and 22L mouse-adapted scrapie strains and CJD-infected human brain as well as PrPC derived from uninfected brain material from all the species tested including cattle (data not shown). The diglycosylated, monoglycosylated and unglycosylated PrPSc forms are immunodetected (albeit to different degrees) in all samples regardless of the Mab used. Mabs 5D6 and 8E9 show similar glycosylation patterns of immunostaining with the monoglycosylated band from hamsters and the diglycosylated bands in sheep and deer being the most reactive. Mab 11F12 immunostains the di-and mono-glycosylated hamster PrP similarly while reacting mainly with the diglycosylated sheep PrP and monoglycosylated deer PrP.

Figure 1.

Western blot analysis of untreated and PK treated total brain lysates from 263K-infected hamsters (H), scrapie-infected sheep (S) and CWD-infected deer (D) using Mabs 08-1/5D6 (A), 08-1/11F12 (B), and 08-1/8E9 (C).

By indirect ELISA, the three Mabs were immunoreactive to PK-treated PrPSc purified from 263K-infected hamster brains. The degree of reactivity was dependent on the extent of the denaturation treatment. Either heat or SDS treatment alone increased immunoreactivity but a combination of the two treatments resulted in the highest levels of antibody binding and immunoreactivity (Table 1) approximating an additive effect of the two treatments and suggesting that epitope exposure is a multi-mechanistic process. Interestingly, although 5D6 binds to a conformational epitope, reactivity of this Mab is not lost, but rather enhanced upon PrP denaturation. It has previously been reported (Tayebi et al., 2004) that heat denaturation is not sufficient to disrupt the polymeric structure of PrPSc. Furthermore, the Mabs were equally immunoreactive by ELISA to both PrPC from uninfected brains and total PrP (normal and abnormal PrP isoforms)in non-denatured brain homogenate. Immunoreactivity was equally enhanced approximately 2-fold following denaturation with SDS and heat. Following PK treatment and denaturation, the immunoreactivity of PrPSc was increased an additional 3-fold due to the presence of less exogenous brain protein binding as a result of the proteolytic digestion (data not shown).

Table 1.

Comparision of Denaturation Treatments on PrPSc Immunoreactivity1.

| Treatment | Signal Intensity2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 5D6 | 11F12 | 8E9 | |

| Untreated | 0.214 ± 0.017 | 0.339 ± 0.009 | 0.303 ± 0.110 |

| SDS3 | 1.229 ± 0.019 | 1.599 ± 0.182 | 1.324 ± 0.251 |

| Heat4 | 1.228 ± 0.018 | 1.085 ± 0.124 | 1.427 ± 0.331 |

| SDS + Heat | 2.232 ± 0.008 | 2.548 ± 0.112 | 2.821 ± 0.252 |

PrPSc was purified from the brains of clinical hamsters infected with the hamster adapted 263K scrapie strain and PK treated as described in Materials and Methods.

Signal intensity was measured by indirect ELISA assay at OD405.

SDS was added to a final concentration of 1%.

Samples were heated at 100o C for 5 min.

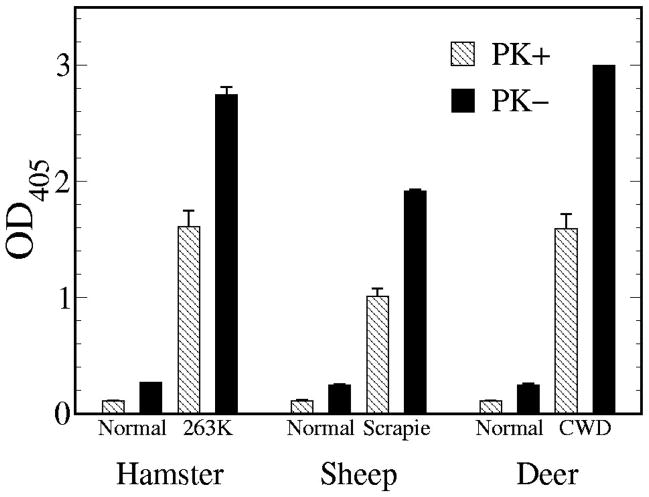

To increase specificity and sensitivity for PrP detection, we utilized a capture ELISA assay incorporating a biotinylated detection antibody. As expected, for each of the Mabs biotinylated, 5–6 biotins were bound to each antibody molecule. Further, the biotinylation of the Mabs did not interfere with or reduce their immunoreactivity as assessed by indirect ELISA using partially purified PK-treated PrPSc (data not shown). Therefore, any differences in the binding and reactivity of the detection antibodies are not the result of the physical biotinylation process. Using PK-treated PrPSc that had been denatured with SDS and heat, several Mab combinations were examined and each antibody was assessed both as the capture reagent and as the detection reagent (Table 2). Only one of the antibody combinations, Mab 11F12 as the capture reagent and biotinylated 5D6 as the detector, was successful in binding to and identifying PrPSc. The results were the same regardless of whether the PrPSc was derived from 263K-infected hamsters, scrapie sheep or CWD-affected deer. The capture ELISA assay utilizing the 11F12-5D6 Mab combination was next assessed for its ability to detect PrP in total and PK-treated brain homogenates from uninfected and infected hamsters, sheep and deer (Figure 2). Similar to the results described above for the indirect ELISA assay on purified hamster brain PrPSc, the detection of PrP in the capture ELISA assay was also dependent on epitope availability and determined by the initial treatment of brain lysate. Untreated brain lysate from infected animals showed a slight (1.5-fold) increase in signal intensity compared to uninfected brain material whereas either detergent or heat denaturation alone resulted in a 4 to7-fold increase. Not surprisingly, the highest levels (greater than 10-fold) of PrPSc detection were achieved when a combination of SDS and heat treatment were used. Furthermore, increasing the concentration of SDS above 1% reduced PrPSc detectability most likely due to an inhibition and/or reversal of antibody-antigen binding. This harsh denaturation treatment, as will be seen below, was not sufficient to completely destroy PrP conformation. It has previously been reported that scrapie infectivity, and presumably some degree of PrPSc conformation, could be maintained in purified PrPSc preparations following treatment with SDS, heat and SDS-PAGE (Brown et al., 1990; Rubenstein et al., 1994).

Table 2.

Analysis of Mab Pairs for Capture ELISA Assay1.

| Capture Mab | Detection Ab (biotinylated) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 11F12 | 5D6 | 8E9 | |

| 11F12 | − | + | − |

| 5D6 | − | − | − |

| 8E9 | − | − | − |

Mab pairs were analyzed using PK-treated PrPSc purified from 263K-infected hamster brains. PrPSc was treated with SDS and heat prior to the capture ELISA assay. All Mabs were diluted to a concentration of 5 μg/ml before use.

Figure 2.

Capture ELISA assay using Mabs 11F12 as the capture reagent and biotinylated 5D6 as the detection reagent. Brain tissue homogenates from normal and infected hamsters, sheep and deer were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. The capture ELISA assay was performed on non-PK and PK-treated brain lysates. Antibody binding was measured colorimetrically at OD405. Each value is based on triplicate readings for six individual samples for each species and expressed as the mean ± standard deviation.

PrPC could be detected in non-PK treated normal brain homogenates by capture ELISA from all three species. In all cases, the signal intensity (~0.25–0.3) was no greater than twice above background (~0.12–0.15). This material was eluted from the wells and examined by Western blotting. In contrast to the results described above where PrPC was detected directly from non-PK-treated brain homogenates, Western blotting of eluted samples resulted only in the detection of IgG light and heavy chains. PrPC was not detectable due to the low levels of bound material. Following PK digestion, ELISA values were reduced to background levels indicating the elimination of PrPC. PrPSc could readily be detected by the capture ELISA assay in PK-treated brain homogenates from 263K-infected hamsters, sheep scrapie and CWD. Interestingly, capture ELISA assays performed on non-PK treated brain homogenates, which contain both PrPC and PrPSc, showed signal intensities higher than what could be attributed to the PrPC (determined from the non-PK normal tissue) and PrPSc (determined from the PK-treated infected tissue) aggregate (Figure 2). It is possible that the increased signal intensity is due to the presence and binding of sPrPSc. An alternative explanation is that the binding of the protein, presumably full-length PrPSc, to the capture Mab induces a spatial change in the antigen which results in the epitope for the second Mab becoming more accessible. We refer to this process as positive immunocooperativity.

With the given set of Mabs used in this study, the degree of positive immunocooperativity, as shown in Figure 2, was species dependent. PrPSc from CWD-infected deer showed the greatest levels with a 58% increase in 5D6 binding beyond that calculated solely from the combination of PrPC and PrPSc, while sheep scrapie PrPSc showed a 46% increase. PrPSc from 263K-infected hamsters exhibited the least, but still significant, with 40%.

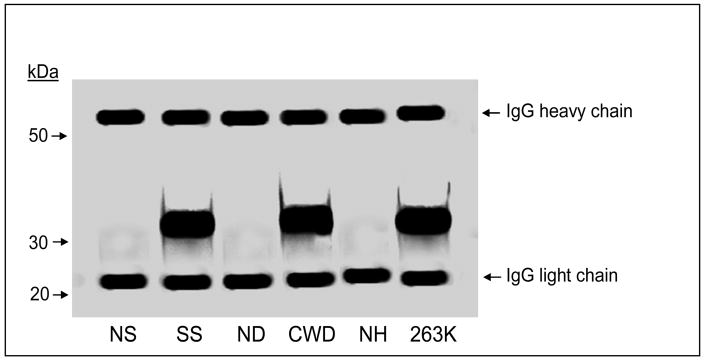

An antibody-induced spatial rearrangement and/or conformational change in PrPSc can be demonstrated by showing that the 11F12-5D6 captured material has altered the epitope for another PrP-specific Mab. The capture assay was performed on non-PK-treated, SDS and heat denatured PrPSc. This was followed by incubation with biotinylated Mab 8E9, streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase and substrate. The lack of a signal above background indicated that the epitope for Mab 8E9 was either no longer available or accessible. However, elution of the 11F12-5D6 captured material from the microtiter wells followed by Western blotting and immunostaining with Mab 8E9 demonstrated robust PrPSc staining indicating that the Mab 8E9 epitope was once again available (Figure 3). Presumably treatment with SDS-PAGE sample buffer, along with electrophoresis in the presence of SDS, alters the 11F12-5D6 binding to PrPSc and reverses the antibody-induced PrPSc changes to once again enable 8E9 binding.

Figure 3.

Western blot analysis of non-PK treated brain homogenates following capture ELISA assay. The capture ELISA assay was carried out on normal sheep (NS), scrapie-infected sheep (SS), normal deer (ND), CWD-infected deer (CWD), normal hamster (NH) and 263K-infected hamsters (263K) under the same conditions as described for Figure 2 using a non-biotinylated detection reagent. The material was eluted from the microtiter plate as described in Materials and Methods and Western blotted. Immunostaining was carried out using Mab 8E9.

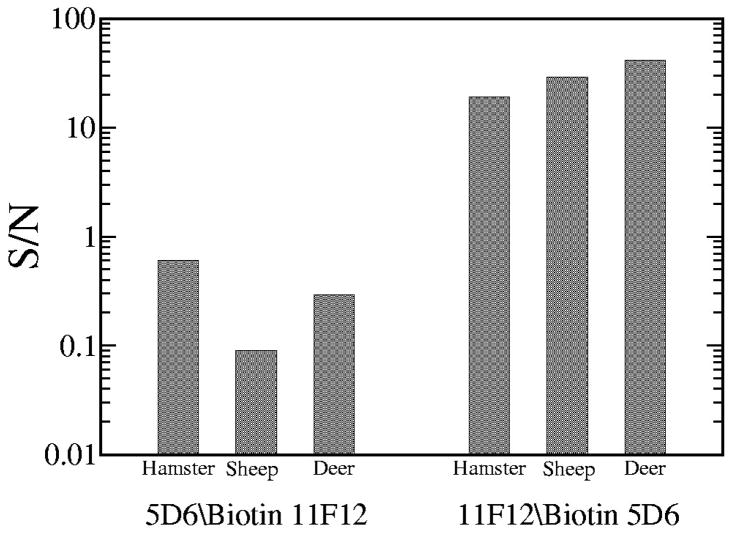

Although Mab 8E9 was able to bind to PrPC and PrPSc directly on Western blots and indirect ELISA assays, replacing 5D6 with 8E9 in the capture ELISA assay resulted in no detectable PrP indicating the absence of biotinylated 8E9 binding to the antigen. Furthermore, the PrPSc specificity of the 11F12–5D6 antibody pair was not only due to the presence of these specific Mabs but also to the sequence of the binding events. Reversing the antibodies by utilizing 5D6 as the capture reagent and biotinylated 11F12 as the detection reagent (5D6/Biotin 11F12) resulted in minimal PrPSc binding from non-PK treated brain lysates when compared to the 11F12-biotinylated 5D6 combination (11F12/Biotin 5D6) (Figure 4). A signal to noise (S/N) ratio was obtained by comparing the PrP signal obtained with the capture assay using infected brain lysates with the variance in the background signal obtained from uninfected material from hamster, sheep and deer brain tissue (S/N = (S-S0)/(3σS0); where S=signal, S0=mean background signal, σS0 = standard deviation of the background signal). A S/N ratio of less than 1 indicates that a binding of the Mab is sufficiently weak that the signal measured contains a significant amount of noise. On the other hand, a S/N of 1 or greater indicates that the noise in the measurement is not significant indicating that most of the power in the measurement results from specific Mab binding. The confidence level increases exponentially as the S/N ratio increases. For the 5D6/Biotin 11F12 pair, the S/N ratios were approximately 0.6, 0.1 and 0.3 for hamster, sheep and deer, respectively, indicating that the Mab binding was nonspecific. However, with the 11F12/Biotin 5D6 combination the S/N ratios were approximately 19 (hamster), 28 (sheep) and 42 (deer). These ratios are indicative of the highly significant nature of the specific Mab binding.

Figure 4.

Comparison of reversing the capture and detection reagents in the capture ELISA assay using brain lysates from uninfected and infected hamsters, sheep and deer. Studies using 5D6 as the capture reagent and 11F12 as the biotinylated detection reagent (5D6/Biotin 11F12) are compared to using 11F12 as the capture reagent and 5D6 as the biotinylated detection reagent (11F12/Biotin 5D6). Each assay was performed in triplicate on six individual samples for each species and the ELISA results calculated as the mean ± standard deviation. The increased antibody binding from infected samples (based on the OD405) are compared to the uninfected controls. Plotted on a logarithmic scale is the signal to noise ratio (S/N) as calculated from the signal power of the infected samples to the power in the control samples (noise).

4. Discussion

The diagnosis of prion diseases, such as scrapie and BSE, has traditionally relied upon the identification of the disease-associated form of the prion protein, PrPSc, based on its resistance to digestion by PK. Studies have reported on the use of differential solubility with chaotropic agents in the absence of, or in combination with, PK along with phosphotungstic precipitation for the detection of PrPSc using the time-resolved fluorescence (DELFIA) reporter system (Barnard and Sy, 2003; Dabaghian et al., 2005; Safar et al., 1998, 2002). However, these extraction protocols still suffer from the possibility of selective loss of soluble forms of PrPSc (Muramoto et al., 1996). A distinct approach, one that circumvents protease digestion, is the conformation-dependent immunoassay (Safar et al., 1998, 2002) that takes advantage of the differential availability of sequestered antibody epitopes between PrPC and PrPSc. An antibody is used which recognizes a central epitope with differential accessibility between PrPC (available) and PrPSc (not accessible until thermal or chemical denaturation).

Circumvention of the differential solubilities and protease digestion step might theoretically yield increased sensitivity of PrPSc-based detection methods and make these methods more amenable to high-throughput technologies. However, it has proved difficult to discriminate between PrPC and PrPSc with antibodies, despite some early reports (Korth et al., 2003; Paramithiotis et al., 2003; Moroncini et al., 2004). Interestingly, tyrosine-tyrosine-arginine (YYR) motifs (Paramithiotis et al., 2003) were reasoned to be more solvent-accessible in the pathological isoform of PrP, and a monoclonal antibody directed against these motifs was reported to be capable of selectively detecting PrPSc across a variety of platforms. However, YYR motifs are certainly not unique to pathological prion proteins, and it remains to be determined whether this reagent can really improve the sensitivity of detection of prion infections.

Our studies indicate that antibody binding to PrP in total brain homogenates can induce epitope unmasking. Whether these changes cause PrP conformational alterations, refolding of PrPC into PrPSc and/or changes in the PK-resistant or sPrPSc forms to make them more accessible to additional antibody binding is uncertain. Regardless of the mechanism, the dynamics of the antibody-antigen interaction results in an increase of PrPSc detection beyond what one would expect from simply an additive effect of the total PrP present. These findings point to the ability to increase the sensitivity of PrPSc detection without the need to proteolytically digest the PrPC.

Most proteins assume a distinct three-dimensional structure in vivo and in vitro, and this native structure is necessary for function. A protein’s structure is determined by its amino acid sequence and the surrounding environment and as a protein unfolds, interactions are disrupted and both secondary and tertiary structure can be lost. In addition, the folded and unfolded states of proteins are in equilibrium. Even under conditions that favor the folded state, a protein is not locked into a single conformation. The amino acids are free to interact and move according to the forces placed on them by neighboring atoms and the solvent, producing many conformations that may differ only very slightly (conformers). Even slight changes in binding epitopes attributable to either localized or more dramatic conformational changes of a protein can have profound effects on antibody-based diagnostic tests. Protein motion can have dramatic effects on protein-protein interactions, specifically antibody-epitope recognition (Kimmermann et al., 2006; Jimenez et al., 2004). For the prion protein, the same amino acid sequence can produce different folded structures, which can hide or create new epitopes. PrPSc is intrinsically polymorphic and heterogeneous with respect to conformation (Tzaban et al., 2002). Using an array of PrP-specific antibodies, Novitskaya et al (2006) studied the conformation of multimeric PrP within a single fibril or particle without PK pretreatment of the sample on amyloid fibrils prepared from full-length recombinant PrP. This revealed conformational heterogeneity of PrP fibrils as measured for either the entire fibrillar population or even within individual fibrils.

TSE agent pathogenesis and propagation may occur through PrPC-PrPSc interactions in association with additional macromolecules (nucleic acids, proteins, lipids, etc) resulting in PrPSc directed conversion of PrPC into new PrPSc. This process has been modeled in cell-free reactions (Horiuchi et al., 1999, 2001; Kocisko et al., 1994; Saborio et al., 2001). The sequence- and strain-specificities of these reactions suggest that such interactions between the normal and abnormal isoforms play important roles in the propagation and pathogenesis of TSE diseases (Caughey et al., 2001).

It has previously been reported (Li et al., 2000) that binding of Mabs to the N-terminus of recombinant PrP (in the region of aa 23–145) could block the recognition of another antibody that normally binds to a conformational epitope located within the C terminus. The mechanism responsible for this negative immunocooperativity is not clear but probably involves an N-terminus binding-induced conformational change in the C-terminus, resulting in the loss of the C-terminus antibody epitope. Such a conformational change is probably subtle and limited to specific regions of the PrP (Li et al., 2000). In addition, it has been reported that together with the highly flexible aa 90–123 tail, the aa 132–160 PrP segment participates in the structural reorganization to PrPSc (Torrent et al., 2004). Our studies are in agreement with those findings since 11F12 binds in the region of aa 93–122 and leads to a refolding event resulting in epitope modifications. Furthermore, it is interesting to speculate that although the Mabs in the present study were all raised to PK-treated PrPSc which is devoid of the first approximately 90 aa at the N-terminus, this region could nevertheless play a role in the full-length PrPSc positive immunocooperativity we observed following antibody binding at a distant epitope.

The PrPSc-induced transformation of PrPC into protease-resistant forms can be separated kinetically and biochemically into two different steps: first, the binding between PrPC and PrPSc, and second, the conversion of the bound PrPC to PrPSc. Thus, the generation of protease-resistant PrP can be affected either at the binding or conversion steps. Data indicate that the inhibition of PrPSc formation by the PrP synthetic peptides 109–141, 166–179 and 200–223 is due to interference with the initial binding between the two PrP isoforms as a result of the peptide directly binding to PrPC (Horiuchi et al., 2001). This binding could physically block the PrPSc binding site and/or alter the conformation of PrPC making it incapable of binding to PrPSc. On the other hand, our data using native PrP suggests that targeting other regions of the PrP molecule (i.e. aa 93–122) is likely capable of augmenting the initial PrPC-PrPSc interaction. Previously, antibody binding studies have suggested that PrP aa residues 90–120 are likely to be critical for the conversion of PrPC to PrPSc (Peretz et al., 1997). Since the conversion of PrPC to PrPSc involves conformational changes in the prion protein, it is likely that some of the PrP-specific antibody binding epitopes will be altered. Furthermore, denaturation of sPrPSc with chaotropes enhances its immunoreactivity toward certain antibodies, due to exposure of partially buried epitopes, which are equally available in native PrPC (Safar et al., 1998). These changes in epitope availability can be used to study the PrP folding/unfolding process during the course of infection and may be used to alter agent propagation. Studies using Mabs have indicated that residues 93–102 are exposed in PrPC but are buried upon conversion to the PrPSc isoform. Furthermore, PrP103–107 residues are partially buried in PrPSc while only the PrP107–112 epitope remains exposed, suggesting that the region PrP93–112 undergoes conformational changes during its conversion to PrPSc (Yuan et al., 2005). Further, studies performed using different combinations of anti-PrP Mabs with mice affected with various mouse-adapted scrapie strains found that some PrP conformational changes, as assessed by PrP antibody epitope availability, could be common while others are specific for the various scrapie strains (Pan et al., 2004).

The infectious agent is detected in lymphoid tissue prior to the onset of clinical signs associated with replication in the central nervous system. Chronic inflammatory conditions involve various cell types of the immune system (including B and T lymphocytes, follicular dendritic cells (FDCs), dendritic cells and macrophages), some of which have been associated with replication of the infectious agent (Kitamoto et al., 1991; Brown et al., 1999; Klein et al., 2001; Prinz et al., 2003). It is possible that these cells might release factors, including antibodies, which induce PrP conformational alterations. In addition, activated B lymphocytes express lymphotoxins which stimulates FDC differentiation and PrPC up-regulation in stromal FDC precursors which, in turn, appear to confer infectious agent replication competence to sites of inflammation in otherwise agent-free organs (Heikenwalder et al., 2005).

Defining the influence of antibody binding on PrP conformational alterations and agent replication would facilitate studies interrogating the entire protein for the sites that are necessary for the conversion process to occur. This, in turn, would have implications into the identification of therapeutic target sites on the protein that could be manipulated to prevent disease progression and subsequent neuropathogenesis..

Acknowledgments

We are appreciative to Dr. Thomas Wisniewski (New York University) for synthetic peptides. This work was supported in part by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (1RO1 HL63837), Health Science Center Research Initiative and US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command (DAMD17-03-1-0368).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abid K, Soto C. Biomedicine and diseases: Review the intriguing prion disorders. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:2342–2351. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6140-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso DOV, An C, Daggett V. Simulations of biomolecules: characterization of the early steps in the pH-induced conformational conversion of the hamster, bovine, and human forms of the prion protein. Philos Trans R Soc Lond A. 2002;360:1–13. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2002.0986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso DOV, DeArmond SJ, Cohen FE, Daggett V. Mapping the early steps in the pH-induced conformational conversion of the prion protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:2985–2989. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061555898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard G, Sy MS. The diagnosis of transmissible spongiform encephalopathies using differential extraction and DELFIA. In: Krull I, editor. Prions and Mad Cow Disease. Marcel Dekker; New York: 2003. pp. 277–315. [Google Scholar]

- Basler K, Oesch B, Scott M, Westaway D, Wälchli M, Groth DF, McKinley MP, Prusiner SB, Weissmann C. Scrapie and cellular PrP isoforms are encoded by the same chromosomal gene. Cell. 1986;46:417–428. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90662-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KL, Stewart K, Ritchie DL, Mabbott NA, Williams A, Fraser H, Morrison WI, Bruce ME. Scrapie replication in lymphoid tissues depends on prion protein-expressing follicular dendritic cells. Nature Med. 1999;5:1308–1312. doi: 10.1038/15264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown P, Liberski PP, Wolff A, Gajdusek DC. Conservation of infectivity in purified fibrillary extracts of scrapie-infected hamster brain after sequential enzymatic digestion or polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:7240–7244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.18.7240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carp RI, Callahan SM. In vitro interaction of scrapie agent and mouse peritoneal macrophages. Intervirology. 1981;16:8–13. doi: 10.1159/000149241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carp RI, Kim YS, Callahan SM. Pancreatic lesions and hypoglycemia-hyperinsulinemia in scrapie-infected hamsters. JInfect Dis. 1990;161:462–466. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.3.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrell RW, Gooptu B. Conformational changes and disease—serpins, prions and Alzheimer’s. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1998;8:799–809. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(98)80101-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caughey B. Interactions between prion protein isoforms: the kiss of death? Trends Biochem Sci. 2001;26:235–242. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01792-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caughey B, Raymond GJ. The scrapie-associated form of PrP is made from a cell surface precursor that is both protease- and phospholipase-sensitive. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:18217–18223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caughey B, Raymond GJ, Callahan MA, Wong C, Baron GS, Xiong L. Interactions and conversions of prion protein isoforms. Adv Prot Chem. 2001;57:139–169. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(01)57021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caughey B, Raymond GJ, Ernst D, Race RE. N-Terminal truncation of the scrapie-associated form of PrP by lysosomal protease(s)-implications regarding the site of conversion of PrP to the protease-resistant state. J Virol. 1991;65:6597–6603. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.12.6597-6603.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen FE, Prusiner SB. Pathologic conformations of prion proteins. Ann Rev Biochem. 1998;67:793–819. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins PS, Lawson VA, Masters PC. Transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. Lancet. 2004;363:51–61. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro Y, Kraineva J, Gomes MPB, Lopes MH, Martins VR, Lima LMTR, Foguel D, Winter R, Silva JL. The amino-terminal PrP domain is crucial to modulate prion misfolding and aggregation. Biophys J. 2005;89:2667–2676. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.067603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabaghian RH, Barnard G, McConnell I, Clewley JP. An immunoassay for the pathological form of the prion protein based on denaturation and time resolved fluorometry. J Virol Methods. 2005;132:85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson AG, Outram GW. Genetic aspects of unconventional virue infections: the basis of the virino hypothesis. Ciba Found Symp. 1988;135:63–83. doi: 10.1002/9780470513613.ch5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glatzel M, Ott PM, Linder T, Gebbers JO, Gmür A, Wüst W, Huber G, Moch H, Podvinec M, Stamm B, Aguzzi A. Human prion diseases: epidemiology and integrated risk assessment. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:757–763. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00588-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heikenwalder M, Zeller N, Seeger H, Prinz M, Klohn PC, Schwarz P, Ruddle NH, Weissmann C, Aguzzi A. Chronic lymphocytic inflammation specifies the organ tropism of prions. Science. 2005;307:1107–1110. doi: 10.1126/science.1106460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiuchi M, Baron GS, Xiong LW, Caughey B. Inhibition of interactions and interconversions of prion protein isoforms by peptide fragments from the C-terminal folded domain. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:15489–15497. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100288200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiuchi M, Chabry J, Caughey B. Specific binding of normal prion protein to the scrapie form via a localized domain initiates its conversion to the protease-resistant state. EMBO J. 1999;18:3193–3203. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.12.3193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez R, Salazar G, Yin J, Joo T, Romesberg FE. Protein dynamics and the immunological evolution of molecular recognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:3803–3808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305745101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kascsak RJ, Rubenstein R, Merz PA, Carp RI, Robakis NK, Wisniewski HM, Diringer H. Immunological comparison of scrapie-associated fibrils isolated from animals infected with four different scrapie strains. J Virol. 1986;59:676–683. doi: 10.1128/jvi.59.3.676-683.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kascsak RJ, Rubenstein R, Merz PA, Tonna-DeMasi M, Fersko R, Carp RI, Wisniewski HM, Diringer H. Mouse polyclonal and monoclonal antibody to scrapie-associated fibril proteins. J Virol. 1987;61:3688–3693. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.12.3688-3693.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JI, Kuizon S, Rubenstein R. Comparison of PrP transcription and translation in two murine myeloma cell lines. J Neuroimmunol. 2003;140:137–142. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(03)00181-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamoto T, Muramoto T, Mohri S, Doh-Ura K, Tateishi J. Abnormal isoform of prion protein accumulates in follicular dendritic cells in mice with Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. J Virol. 1991;65:6292–6295. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.11.6292-6295.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein MA, Kaeser PS, Schwarz P, Weyd H, Xenarios I, Zinkernagel RM, Carroll MC, Verbeek JS, Botto M, Walport MJ, Molina H, Kalinke U, Acha-Orbea H, Aguzzi A. Complement facilitates early prion pathogenesis. Nature Med. 2001;7:410–411. doi: 10.1038/86567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocisko DA, Come JH, Priola SA, Chesebro B, Raymond GJ, Lansbury PT, Caughey B. Cell-free formation of protease-resistant prion protein. Nature. 1994;370:471–474. doi: 10.1038/370471a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocisko DA, Priola SA, Raymond GJ, Chesebro B, Lansbury PT, Jr, Caughey B. Species specificity in the cell-free conversion of prion protein to protease-resistant forms: a model for the scrapie species barrier. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3923–3927. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korth C, Stierli B, Streit P, Moser M, Schaller O, Fischer R, Schulz-Schaeffer W, Kretzschmar H, Raeber A, Braun U, Ehrensperger F, Hornemann S, Glockshuber R, Riek R, Billeter M, Wüthrich K, Oesch B. Prion (PrPSc)-specific epitope defined by a monoclonal antibody. Nature. 1997;390:74–77. doi: 10.1038/36337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFauci G, Carp RI, Meeker HC, Ye X, Kim JI, Natelli M, Cedeno M, Petersen RB, Kascsak R, Rubenstein R. Passage of chronic wasting disease prion into transgenic mice expressing Rocky Mountain elk (Cervus elaphus nelsoni) PrPC. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:3773–3780. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82137-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Liu T, Wong BS, Pan T, Morillas M, Swietnicki W, O’Rourke K, Gambetti P, Surewicz WK, Sy MS. Identification of an epitope in the C terminus of normal prion protein whose expression is modulated by binding events in the N terminus. J Mol Biol. 2000;301:567–573. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manuelidis L. A 25 nm virion is the likely cause of transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. J Cell Biochem. 2007;100:897–915. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moroncini G, Kanu N, Solforosi L, Abalos G, Telling GC, Head M, Ironside J, Brockes JP, Burton DR, Williamson RA. Motif-grafted antibodies containing the replicative interface of cellular PrP are specific for PrPSc. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:10404–10409. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403522101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muramoto T, Scott M, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB. Recombinant scrapie-Like prion protein of 106 amino acids is soluble. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:15457–15462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novitskaya V, Makarava N, Bellon A, Bocharova OV, Bronstein IB, Williamson RA, Baskakov IV. Probing the conformation of the prion protein within a single amyloid fibril using a novel immunoconformational assay. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:15536–15545. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601349200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan KM, Baldwin M, Nguyen J, Gasset M, Serban A, Groth D, Mehlhorn I, Huang Z, Fletterick RJ, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB. Conversion of -helices into β-sheets features in the formation of the scrapie prion proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10962–10966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.10962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan T, Li R, Kang SC, Wong BS, Wisniewski T, Sy M-S. Epitope scanning reveals gain and loss of strain specific antibody binding epitopes associated with the conversion of normal cellular prion to scrapie prion. J Neurochem. 2004;90:1205–1217. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paramithiotis E, Pinard M, Lawton T, LaBoissiere S, Leathers VL, Zou WQ, Estey LA, Lamontagne J, Lehto MT, Kondejewski LH, Francoeur GP, Papadopoulos M, Haghighat A, Spatz SJ, Head M, Will R, Ironside J, O’Rourke K, Tonelli Q, Ledebur HC, Chakrabartty A, Cashman NR. A prion protein epitope selective for the pathologically misfolded conformation. Nature Med. 2003;9:893–899. doi: 10.1038/nm883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peretz D, Williamson RA, Matsunaga Y, Serban H, Pinilla C, Bastidas RB, Rozenshteyn R, James TL, Houghten RA, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB, Burton DR. A conformational transition at the N terminus of the prion protein features in formation of the scrapie isoform. J Mol Biol. 1997;273:614–622. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinz M, Heikenwalder M, Junt T, Schwarz P, Glatzel M, Heppner FL, Fu YX, Lipp M, Aguzzi A. Positioning of follicular dendritic cells within the spleen controls prion neuroinvasion. Nature. 2003;425:957–962. doi: 10.1038/nature02072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusiner SB. Novel proteinaceous infectious particles cause scrapie. Science. 1982;216:136–144. doi: 10.1126/science.6801762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusiner SB. Prions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13363–13383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein R, Carp RI, Ju W, Scalici C, Papini M, Rubenstein A, Kascsak R. Concentration and distribution of infectivity and PrPSc following partial denaturation of a mouse-adapted and a hamster-adapted scrapie strain. Arch Virol. 1994;139:301–311. doi: 10.1007/BF01310793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safar JG, Geschwind MD, Deering C, Didorenko S, Sattavat M, Sanchez H, Serban A, Vey M, Baron H, Giles K, Miller BL, DeArmond SJ, Prusiner SB. Diagnosis of human prion disease, Proc. Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:3501–3506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409651102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safar JG, Scott M, Monaghan J, Deering C, Didorenko S, Vergara J, Ball H, Legname G, Leclerc E, Solforosi L, Serban H, Groth D, Burton DR, Prusiner SB, Williamson RA. Measuring prions causing bovine spongiform encephalopathy or chronic wasting disease by immunoassays and transgenic mice. Nature Biotechnol. 2002;20:1147–1150. doi: 10.1038/nbt748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safar J, Wille H, Itri V, Groth D, Serban H, Torchia M, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB. Eight prion strains have PrP(Sc) molecules with different conformations. Nature Med. 1998;4:1157–1165. doi: 10.1038/2654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saborio GP, Permanne B, Soto C. Sensitive detection of pathological prion protein by cyclic amplification of protein misfolding. Nature (London) 2001;411:810–813. doi: 10.1038/35081095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl N, Baldwin MA, Teplow DB, Hood L, Gibson BW, Burlingame AL, Prusiner SB. Structural studies of the scrapie prion protein using mass spectrometry and amino acid sequencing. Biochemistry. 1993;32:1991–2002. doi: 10.1021/bi00059a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl N, Prusiner SB. Prions and prion proteins. FASEB J. 1991;5:2799–2807. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.5.13.1916104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tayebi M, Enever P, Sattar Z, Collinge J, Hawke S. Disease-associated prion protein elicits immunoglobulin M responses in vivo. Mol Med. 2004;10:104–111. doi: 10.2119/2004-00027.Tayebi. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrent J, Alvarez-Martinez MT, Liautard JP, Balny C, Lange R. The role of the 132–160 region in prion protein conformational transitions. Prot Sci. 2004;14:956–967. doi: 10.1110/ps.04989405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzaban S, Friedlander G, Schonberger O, Horonchilk L, Yedidia Y, Shaked G, Gabizon R, Taraboulos A. Protease-sensitive scrapie prion protein in aggregates of heterogeneous sizes. Biochemistry. 2002;41:12868–12875. doi: 10.1021/bi025958g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadsworth JDF, Collinge J. Update on human prion disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1772:598–609. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan FF, Biffin S, Brazier MW, Suarez M, Roberto CC, Hill A, Collins SJ, Sullivan JS, Middleton D, Multhaup G, Geczy AF, Masters CL. Detection of prion epitopes on PrPc and PrPsc of transmissible spongiform encephalopathies using specific monoclonal antibodies to PrP. Immunol Cell Biol. 2005;83:632–637. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2005.01384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann J, Oakman EL, Thorpe IF, Shi X, Abbyad P, Brooks CL, III, Boxer SG, Romesberg FE. Antibody evolution constrains conformational heterogeneity by tailoring protein dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:13722–13727. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603282103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]