Abstract

Perirectal sepsis is a potentially severe complication which may follow minor anorectal intervention and be slow to be diagnosed and treated. We report the presentation and outcome of three patients with perirectal sepsis of differing aetiologies. Awareness of the possible diagnosis, urgent investigation with cross-sectional imaging and immediate treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics is vital. However, radical surgical intervention may be necessary. This report highlights the importance of investigating patients with persistent pelvic pain after minor anorectal procedures or trauma and maintaining a high index of suspicion for this important complication.

Keywords: Haemorrhoids, Lateral anal sphincterotomy, Perirectal sepsis

Perirectal sepsis is a potentially severe complication which may follow minor anorectal intervention and be slow to be diagnosed and treated. We report the presentation and outcome of three patients with perirectal sepsis of differing aetiologies.

Case histories

Case report 1

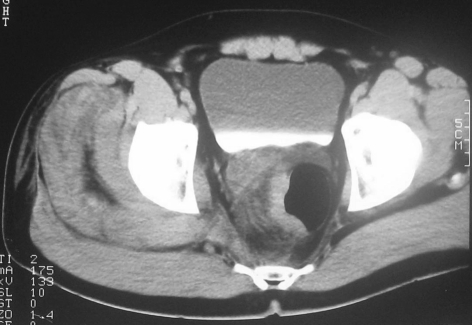

A 42-year-old fit man with no significant past medical history presented acutely to the orthopaedic department (10 days after suffering a low-impact fall off the tailgate of a truck) with progressive and constant pain within the right buttock which radiated along the distribution of sciatic nerve and was associated with rigors. On examination, he was pyrexial (38.5°C) and had marked right-sided gluteal induration extending onto thigh. Digital rectal examination was normal. He had a leukocytosis of 25 × 109/l, and renal impairment with serum creatinine of 185 μmol/l and urea of 12.5 mmol/l. CT scan examination revealed ill-defined inflammatory changes extending from the right side of the rectal wall at the level of mid-rectum and which continued through the sciatic notch into the buttock and thigh (Fig. 1). A discrete fluid collection between the gluteal muscles was subsequently aspirated and revealed β-haemolytic streptococcus. Triple antibiotic therapy was commenced (penicillin, metronidazole and gentamycin) and the patient referred to general surgery. At this point, digital rectal examination and sigmoidoscopy revealed pus within the rectum with thickening of the right side wall, from which biopsy demonstrated non-specific inflammation. The patient's general condition deteriorated with established renal failure and escalating oxygen requirements over the next 72 h and laparotomy was performed. A loop sigmoid defunctioning stoma was fashioned through an oblique incision in the LIF, which revealed oedematous retroperitoneal and pelvic tissue with omental adherence to pelvic colon. The thigh collection was also openly drained. Despite this, the patient continued to deteriorate, was ventilated, and dependent on high-dose adrenaline and noradrenaline. Repeat CT 48 h later showed persistent perirectal inflammation and the decision was then made to perform low Hartmann's procedure including perirectal fat, presumed to be the source of persisting sepsis. This intervention coincided with a slow, but steady, recovery. First attempt at reversal of Hartmann's procedure 9 months later was rewarded with stricture; however, subsequent revisional surgery proved successful at restoring continuity.

Figure 1.

Contrast-enhanced CT shows ill-defined inflammatory changes extending from the right side of rectal wall at the level of mid-rectum.

Case report 2

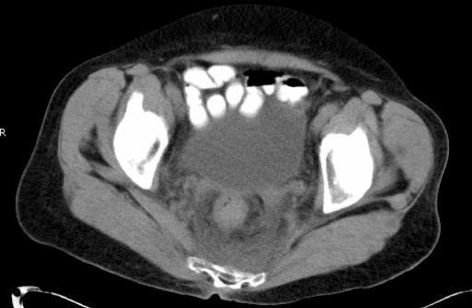

A 69-year-old woman, presenting with a long history of prolapsing haemorrhoids, underwent routine Milligan Morgan haemorrhoidectomy, and was discharged home the next morning on a 5-day course of metronidazole (400 mg, three times daily) and laxatives. On the fourth postoperative day, she was re-admitted with severe pelvic pain associated with constipation and purulent rectal discharge including fresh blood. On admission, she appeared well, was apyrexial and digital rectal examination was well tolerated with no evidence of abscess. White cell count was slightly raised (13.5 × 109/l). She settled after opening her bowels but re-presented to the accident and emergency department a few weeks later following collapse at home. At this admission, she had deep-seated rectal pain radiating to pelvis and associated with bloody loose stool. She was apyrexial with lower abdominal tenderness and guarding in the right iliac fossa. Rectal examination there was painful but otherwise unremarkable. White cell count was 18.9 × 109/l and plain abdominal X-ray was unremarkable. CT scan examination revealed extensive inflammatory changes around a thickwalled rectum (Fig. 2). A diagnosis of perirectal sepsis was made, and the patient commenced on intravenous cefuroxime and metronidazole. She improved and follow-up CT scan 4 weeks later confirmed the inflammatory changes around the rectum to have normalised.

Figure 2.

Contrast-enhanced CT shows extensive inflammatory changes around a thick-walled rectum.

Case report 3

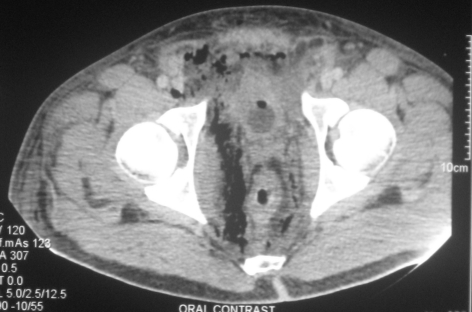

A 34-year-old man admitted with peri-anal pain underwent examination under anaesthesia the following day. This demonstrated an acute posterior anal fissure, and lateral anal sphincterotomy was performed. Postoperatively, he developed right iliac fossa pain associated with fever and rigors. Laparoscopy was performed and revealed turbid fluid within the lower peritoneal cavity associated with an ‘injected-look’ to the appendix, which although removed was subsequently proven to be normal. He remained unwell developed acute renal failure and was transferred acutely to intensive care for assessment and dialysis. In view of his recent history, the surgical team arranged CT scan examination, which demonstrated retroperitoneal free gas tracking along the right psoas muscle and down to the rectum, which itself was markedly thickened along with the right obturator muscle and perirectal fat. As a result, the rectum and urinary bladder had shifted to the left side (Fig. 3). The patient deteriorated markedly over the space of a few hours and was now anuric, septic and hypoxic. Blood cultures revealed Staphylococcus aureus. A diagnosis was made of possible rectal perforation. Emergency laparotomy revealed perirectal purulent fluid tracking up into the anterior abdominal wall with marked perirectal and mesorectal induration. Gas was present within the tissues but no obvious rectal perforation seen. In view of the patient's perilous state, experience of case 1 and the lack of obvious rectal perforation, the decision were made to remove the rectum along with the macroscopic perirectal fat involvement (Hartmann's procedure). There was transient improvement in the patient's condition; however, re-laparotomy was performed 10 days later as the patient remained septic. A further collection in the right perirectal area, which extended into the right groin, was drained. Although the patient drained copious amounts of pus through the groin wound for weeks, he made slow, but steady, recovery and was discharged 8 weeks later.

Figure 3.

Contrast-enhanced CT shows retroperitoneal free gas to the right of rectum, which was markedly thickened along with the right obturator muscle and perirectal fat. As a result, the rectum and urinary bladder had shifted to the left side.

Discussion

These three cases describe differing aetiologies but a similar, and potentially lethal, clinical scenario that by its insidious onset can be slow to diagnose and, therefore, institute timely treatment. The clinical picture is consistent with a spreading inflammatory process in soft tissue commencing from the point of injury and presumably infective in origin but different to necrotising fasciitis, which spreads to involve superficial layers. Patients' reaction to the same infective insult will differ. What was striking about both patients who underwent surgery was the rapid development of multi-organ failure (associated with spreading inflammatory changes but no abscess) as well as the postoperative course, in which both patients produced large volumes of pus per drain over weeks, presumably from residual necrotic fat, rather akin to that seen after pancreatic debridement for sepsis. The post-haemorrhoidectomy patient had similar CT appearances and may have pursued a different course if not recognised and treated aggressively with parenteral antibiotics. Failure to respond to rectal defuncting in the first case no doubt influenced the decision to move straight to rectal excision in the third case. Whilst this ran the risk of over-treatment, both patients were young, in multi-organ failure and on increasing inotrope requirements. Resolution of their illness may well have been in part down to excision of the infected perirectal tissue, which had been infiltrated by gas-forming organisms along with the site of presumed microperforation. There was no obvious macroscopic rectal perforation or, indeed, faecal contamination and we feel that the clinical picture in all three patients fits best with a spreading infection of soft tissue but without any obvious superficial signs. This latter point is important, as the only clue may be the apparent severity of the rectal/perineal discomfort and associated pyrexia.

Perirectal sepsis has been associated with a number of different treatments of haemorrhoids such as rubber band ligation, injection sclerotherapy,1,2 and following stapled haemorrhoidectomy.3 The cause of sepsis remains uncertain although rectal perforation causing faecal contamination of the sterile perirectal space has been demonstrated after stapled haemorrhoidectomy.4 Relatively innocuous surgical intervention, such as open haemorrhoidectomy or lateral anal sphincterotomy, may provide a portal of entry for bacteria that could explain local or indeed distant sepsis (e.g. infective endocarditis following rubber band ligation).5 Following haemorrhoidectomy, persistent postoperative pelvic pain for more than few weeks is rare4 and should be investigated thoroughly as it may be a manifestation of serious complication. In our third case, the patient re-presented, after open lateral sphincterotomy, complaining of pelvic pain radiating to the abdomen on the fourth postoperative day, which led to laparoscopy and appendicectomy. A subsequent CT examination revealed the perirectal source. Similar presenting symptoms have been reported by others.6 Pelvic pain following minor anorectal intervention associated with systemic signs of fever, rigor or leukocytosis, may suggest perirectal sepsis. Abdominal plain X-ray demonstrates soft tissue gas6 in 57% of cases.7 CT scan examination demonstrates the presence of sepsis (as retroperitoneal free gas or changes in mesorectal fat) in nearly all cases.8 Antimicrobial therapy should be initiated immediately and directed against both aerobes and anaerobes, as study of the aerobic and anaerobic microbiology of 23 retroperitoneal pelvic sepsis patients revealed that in 50% of cases both aerobes and anaerobes were recovered.9 This may explain why the patient in case 2 developed sepsis in spite of receiving postoperative metronidazole.

Drainage of any collection together with controlling the source of contamination is an essential part of management and the radicality of surgery decided upon on an individual basis. However, draining the thigh sepsis without removing the primary source of infection proved to be an ineffective strategy as the patient's condition (case 1) continued to deteriorate until the rectum, and crucially the perirectal fat, was excised also allowing adequate drainage. The response to anti-microbial therapy depends on many factors including the early recognition of sepsis and initiation of therapy, persistent source of contamination and, whilst not a factor in this series, the patient's immune status (presence of diabetes mellitus, steroid therapy, immunosuppression and HIV infection will increase susceptibility).

Conclusions

Although rare, perirectal sepsis is a potentially grave complication following minor anorectal procedures or trivial trauma. Presentation may be subtle and a history of severe perineal or pelvic pain should prompt urgent cross-sectional imaging.

References

- 1.Quevedo-Bonilla G, Farkas AM, Abcarian H, Hambrick E, Orsay CP. Septic complications of hemorrhoidal banding. Arch Surg. 1988;123:650–1. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1988.01400290136024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barwell J, Watkins RM, Lloyd-Davies E, Wilkins DC. Life-threatening retroperitoneal sepsis after hemorrhoid injection sclerotherapy: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:421–3. doi: 10.1007/BF02236364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cotton MH. Pelvic sepsis after stapled hemorrhoidectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;200:983. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herold A, Kirsch JJ. Pain after stapled haemorrhoidectomy. Lancet. 2000;356:2187. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)67258-3. author reply 2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tejirian T, Abbas MA. Bacterial endocarditis following rubber band ligation in a patient with a ventricular septal defect: report of a case and guideline analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1931–3. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0769-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maw A, Eu KW, Seow-Choen F. Retroperitoneal sepsis complicating stapled hemorrhoidectomy: report of a case and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:826–8. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6304-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marron CD, McArdle GT, Rao M, Sinclair S, Moorehead J. Perforated carcinoma of the caecum presenting as necrotising fasciitis of the abdominal wall, the key to early diagnosis and management. BMC Surg. 2006;6:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-6-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Makino K, Morikawa M, Mori M, Kohzaki S, Amamoto Y, Matsuoka Y, et al. [CT findings of non-traumatic colorectal perforation] Nippon Igaku Hoshasen Gakkai Zasshi. 1999;59:510–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brook I, Frazier EH. Aerobic and anaerobic microbiology of retroperitoneal abscesses. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:938–41. doi: 10.1086/513947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]