Abstract

The Hedgehog (Hh) signaling pathway plays an important role in prostate development and appears to play an equally important role in promoting growth of advanced prostate cancer. During prostate development, epithelial cells in the urogenital sinus (UGS) express Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) and secrete Shh peptide. The secreted Hh peptide acts on adjacent mesenchymal cells to activate the Hh signal transduction pathway and elicit paracrine effects on epithelial proliferation and differentiation. To identify mesenchymal targets of Shh signaling, we performed microarray analysis on a Shh-responsive, immortalized urogential sinus mesenchymal cell line. We found 68 genes that were up-regulated by Shh and 21 genes that were down-regulated. Eighteen of those were selected for further study with Ptc1 and Gli1 serving as reference controls. We found 10 of 18 were also Hh-regulated in primary UGS mesenchymal cells and 13 of 18 in the cultured UGS. Seven of 18 exhibited Shh-regulated expression in both assays (Igfbp-6, Igfbp-3, Fbn2, Ntrk3, Agpt4, Dmp1, and Mmp13). Three of the 18 genes contained putative Gli binding motifs that bound Gli1 peptide in electrophoretic mobility shift assays. With the exception of Tiam1, target gene expression generally showed no differences in the concentration dependence of ligand-induced expression, but we observed strikingly different responses to direct pathway activation by transfection with activated Smo, Gli1, and Gli2.

Sonic Hedgehog (Shh)2 is a secreted signaling protein that regulates epithelial-mesenchymal interactions during embryonic development in a variety of organs (1). During fetal prostate development, Shh is expressed and secreted by the epithelium of the urogenital sinus (UGS) and acts on the surrounding mesenchyme (2–5). Binding of Hh ligand to its receptor Patched 1 (Ptc1), a 12-span transmembrane protein, activates an intracellular signal transduction mechanism involving a second transmembrane protein Smoothened (Smo), and results in changes in transcriptional regulation of specific target genes through the coordinated activities of three highly related Gli transcription factors (Gli1, Gli2, and Gli3) (6). The transcriptional changes not only affect proliferation and differentiation of UGS mesenchyme but elicit paracrine signals that regulate proliferation and differentiation of the adjacent UGS epithelium (3, 7–9). Emerging evidence suggests that proper spatial and temporal patterns of Hh signaling are required for normal prostate ductal development (1, 10).

Although the diversity of Shh effects is clear, molecules that function downstream of Shh in different contexts remains incompletely characterized. Gli1, Ptc1, and Hedgehog interacting protein are the canonical targets of Hh signaling expressed in nearly all cell types examined to date (11). However, other target genes regulated by the Shh signaling pathway likely vary between tissues and cell types, influenced by the state of differentiation and the presence or absence of co-regulators (1, 12). A number of target genes have been described. The actin-binding protein Missing in Metastasis (MIM) has been identified as a Shh-responsive gene that potentiates Gli-dependent transcriptional activation in skin development and tumorigenesis (13). The forkhead transcription factor Foxe1 was established as a downstream target of the Shh pathway in hair follicle morphogenesis (14). Other Hh target genes include Foxa2 (Hnf-3β) and Coup-Tfii during floor plate development (15, 16), Foxd2 (Mf-2) during somitogenesis (17), Foxm1 in basal cell carcinoma (18), and Foxf1 (Freac-1 or Hfh-8) during lung and foregut organogenesis (19). Other identified target genes include SFRP1, SFRP2, Igfbp-6, and Sil (1, 20–23). For the developing prostate, however, the only target gene identified thus far is Igfbp-6 (24).

We performed a microarray analysis to identify Shh-induced transcriptional changes in a previously characterized, immortalized UGS mesenchymal cell line, UGSM-2 (9). We identified a combination of previously described and novel Shh targets, some of which appear to be prostate selective. The novel Shh-responsive genes provide insight into the molecular mechanism of Shh-regulated prostate development, suggesting roles in cell growth regulation as well as in providing cross-talk with the Wnt and Notch signaling pathways.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Microarray Cell Growth and RNA Isolation—UGSM-2 cells, an immortalized mouse E16 prostate mesenchymal cell lines (10), were set at confluence and allowed to attach overnight in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F-12 containing 10% fetal bovine serum. The next day cells were treated with Shh (R&D Systems 1845-SH/CF) or vehicle in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F-12 containing 0.1% fetal bovine serum. Following 24 h treatment total RNA was isolated using the Qiagen RNeasy RNA isolation kit with on column DNase treatment and eluted in nuclease-free water.

Microarray cDNA Synthesis—First strand synthesis was performed using the SuperScript Choice system (Invitrogen). The manufacturer's protocol was modified by using a high performance liquid chromatography purified T7-(dT)24 primer (Genset Corp.) and incubating at 42 °C. The 20-μl first-strand reactions consisted of 100 pmol of T7-(dT)24 primer, 10 μg of total RNA, 1× first-strand buffer, 10 mm dithiothreitol, 500 μm each dNTP, and 400 units of Superscript II reverse transcriptase. The 150-μl second-strand reactions included 1× second-strand reaction buffer, 200 μm each dNTP, 10 units of DNA ligase, 40 units of DNA polymerase I, and 2 units of RNase H. A phenol/chloroform extraction using phase lock gels (Eppendorf-5 Prime, Inc.) and ethanol precipitation were used to purify the double-stranded cDNA.

Microarray Synthesis of Biotin-labeled cRNA—An in vitro transcription reaction was performed starting with 5 μl of purified cDNA using the Enzo BioArray high yield RNA transcript labeling kit (Affymetrix). The in vitro transcription product was purified using RNeasy spin columns (Qiagen). 20 μg of cRNA was fragmented (0.5 μg/μl) according to Affymetrix instructions.

Microarray Hybridization—Quantification of the cRNA was adjusted to reflect carryover of unlabeled total RNA with an equation provided by Affymetrix: adjusted cRNA yield = cRNA measured after in vitro transcription (μg) – (starting amount of total RNA) × (fraction of cDNA reaction used in in vitro transcription). 20 μg of adjusted fragmented cRNA was added to 300 μl of hybridization mixture that included 0.1 mg/ml herring sperm DNA (Promega/Fisher), 0.5 mg/ml acetylated bovine serum albumin (Invitrogen), and 2× MES hybridization buffer (Sigma). The mixture also contained the following hybridization controls: 50 pm oligonucleotide B2 (Genset Corp.) and 1.5, 5, 25, and 100 pm cRNA BioB, BioC, BioD, and Cre, respectively (ATCC). 200 μl of this mixture was hybridized to the chips (mouse genome 430 2.0 Array) with 24 × 24-μm probe cells for 16 h according to Affymetrix procedures. The 50 × 50-μm test chips were hybridized with 80 μl for 16 h.

Microarray Washing, Staining, and Scanning—The probe arrays were washed with stringent (100 mm MES, 0.1 m [Na+], 0.01% Tween 20) and non-stringent (6× SSPE, 0.01% Tween 20, 0.005% antifoam) buffers in the Affymetrix GeneChip Fluidics station using pre-programmed Affymetrix protocols. The probe arrays were then stained with streptavidin phycoerythrin, and the signal amplified using an antibody solution. The streptavidin stain contained 2× stain buffer (final 1× concentration 100 mm MES, 1 m [Na+], 0.05% Tween 20, 0.005% antifoam, 2 μg/μl acetylated bovine serum albumin, and 10 μg/ml streptavidin (Molecular Probes)). The antibody amplification solution contained 2× stain buffer, 2 μg/μl acetylated bovine serum albumin (Invitrogen), 0.1 mg/ml normal goat IgG (Sigma), and 3 μg/ml biotinylated antibody (Vector Laboratories). Staining was done in the GeneChip fluidics station using pre-programmed Affymetrix protocols. The probe arrays were scanned in the Affymetrix GeneChip scanner.

Microarray Data Analysis—Microarray analysis using Affymetrix mouse 430 2.0 chip was performed in triplicate using RNA from Shh-treated and control cells. Six data files (triplicate of control and Shh-treated samples) were uploaded into Affymetrix Suite 5.0 (MAS5) software. Unknown expressed sequence tags were identified by searching human genome databases. Genes whose signal intensity were lower than 40 were eliminated from further analyses because the signal was not significantly different from base line (no signal). Data with more than 2 present calls in either the control or Shh-treated group were selected for further analysis. Mean signals of the controls and Shh-treated samples were calculated and compared. Student's t tests were performed and genes with p < 0.05 were selected for further analysis. Fold change was calculated by comparing signals from the Shh-treated group with signals from the control group. Genes showing fold changes greater than ±2 were selected.

Cell Treatment for Array Gene Validation—To validate the array data and to examine the Shh response of the array-identified genes several cells lines were used. All cells were treated at confluence for 24 h ±50 nm Shh (R&D Systems catalog number 1845-SH/CF) and ±5 μm cyclopamine (Toronto Research Chemicals) as described above for the microarray. Following treatment, RNA was isolated with Qiagen RNeasy kit with on-column DNase treatment as per the manufacturers protocol. UGSM-2 cells were grown and treated as described above for the array. Mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) were isolated and grown as previously described (25, 26). Balb/c 3T3 fibroblast were obtained from ATCC and grown according to ATCC protocols. Primary UGM cells were made from the mouse E16 mesenchyme, as described (9). Primary cells were in culture for 1 week to expand them before exposure to Shh and cyclopamine. All experiments were performed in triplicate and reported differences were statistically significant (p < 0.05; Student's t test).

Prostate Organ Culture—E16 UGS tissues were isolated from CD-1 mice (Charles River) placed on Millicell-CM filters (Millipore) and grown in serum-free media with supplements as described (26). Tissues were incubated for 3 days ±10 μm cyclopamine; RNA was harvested with Qiagen RNeasy columns as per the manufacturers recommendations.

Effect of Gli1, Gli2, Smo Overexpression, and Forskolin Treatment—UGSM-2 cells were infected with retrovirus that expressed green fluorescent protein alone or co-expressed green fluorescent protein and Gli1, Gli2, or Smo. Cells overexpressing green fluorescent protein were identified by flow cytometry and analyzed for expression of the gene of interest. These cells were grown to confluence, maintained at confluence for 24 h, and RNA harvested as described above. To examine the effect of forskolin, UGSM-2 cells were treated with or without 50 μm forskolin (LC Laboratories, Woburn, MA) during the 24-h period of confluence.

Gene Expression Analysis by Reverse Transcriptase-PCR—Following RNA isolation reverse transcriptase-PCR was performed with gene specific primers (supplemental data Table S1) with normalization to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase for each sample. Total RNA was reverse transcribed with Moloney murine leukemia virus-reverse transcriptase following standard protocols followed by real time PCR. PCR products were detected with Power SYBR Green (Applied Biosystems) using a Bio-Rad iCycler thermocycler.

Immunofluorescence Staining—UGS and prostate tissue sections were fixed with 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin, and processed for immunofluorescence staining (27). The following antibodies were used: rabbit anti-Tiam1 polyclonal antibody (1:250, Calbiochem) and mouse anti-smooth muscle actin (1:200, Sigma). Sections were 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole counterstained, coverslipped, and imaged.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays—Electrophoretic mobility shift assays were performed as previously described (21), using purified Gli1 protein (amino acids 211–1106) or PinPoint protein (Promega, Madison, WI) fused to Gli1 amino acids 879–1106, lacking the zinc finger DNA binding domain. Probes were designed using MacVector software (MacVector, Inc., Cary, NC). Probe sequences are shown, listing the sense sequence (5′→3′) followed by the antisense sequence (5′→3′) used to produce the double-stranded probe: Artn, TTGGGTCCTGGAACCCCCAACTCCCCACA, TGTGGGGAGTTGGGGGTTCCAGGACCCAA; Dner, AGACCAGGCTGACCTCCAACACTGCCTCT, AGAGGCAGTGTTGGAGGTCAGCCTGGTCT; Fbn2, CCATCTCTCTGACCACCAAGTTTCCTCAC, GTGAGGAAACTTGGTGGTCAGAGAGATGG; Hsd11b1, TATACAAACTCACCTCCCAGAAAAGAACT, AGTTCTTTTCTGGGAGGTGAGTTTGTATA; Igfbp-3, TGCGCCGGCCCACCCCCCACCCTCGCCGT, ACGGCGAGGGTGGGGGGTGGGCCGGCGCA; Mmp13, ACCATGAGATGACCACCAAGAGCATCAGC, GCTGATGCTCTTGGTGGTCATCTCATGGT; Plxna2, CAATACAAGGGACCTCCCACTTGGTAAAG, CTTTACCAAGTGGGAGGTCCCTTGTATTG; Rgs4, CCTCCCACTCCACCACCAAGGACAGCTCT, AGAGCTGTCCTTGGTGGTGGAGTGGGAGG; Tiam1, CCGATCCACAGACCACCCAGCACCAGAGC, GCTCTGGTGCTGGGTGGTCTGTGGATCGG; Tnmd-1, GTGTTGTGGTGACCACCAAACATAAAAT, AATTTTATGTTTGGTGGTCACCACAACAC.

Mutant probe sequences are shown, listing the sense sequence (5′→3′) followed by the antisense sequence (5′→3′): Artn, TTGGGTCCTGGAAGGGGGAACTCCCCACA, TGTGGGGAGTTCCCCCTTCCAGGACCCAA; Dner, AGACCAGGCTGACGAGGTACACTGCCTCT, AGAGGCAGTGTACCTCGTCAGCCTGGTCT; Fbn2, CCATCTCTCTGACGTGGTAGTTTCCTCAC, GTGAGGAAACTACCACGTCAGAGAGATGG; Hsd11b1, TATACAAACTCACCTCCCAGAAAAGAACT, AGTTCTTTTCTGGGAGGTGAGTTTGTATA; Igfbp-3, TGCGCCGGCCCACGGGGGACCCTCGCCGT, ACGGCGAGGGTCCCCCGTGGGCCGGCGCA; Mmp13, ACCATGAGATGACGTGGTAGAGCATCAGC, GCTGATGCTCTACCACGTCATCTCATGGT; Plxna2, CAATACAAGGGACGAGGGACTTGGTAAAG, CTTTACCAAGTCCCTCGTCCCTTGTATTG; Rgs4, CTCCCGAAGAAGTGGGACAATGATGGTTC, GAACCATCATTGTCCCACTTCTTCGGGAG; Tiam1, CCGATCCACAGACGTGGGAGCACCAGAGC, GCTCTGGTGCTCCCACGTCTGTGGATCGG; Tnmd, GTGTTGTGGTGACGTGGTAACATAAAATT, AATTTTATGTTACCACGTCACCACAACAC.

Whole Mount in Situ Hybridization—The following cDNAs were used as probes: Igfbp-3 (accession number BC058261), Timp3 (accession number BC014713), Plxna2 (accession number BC051045), Cxcl14 (accession number BC0799661), and Dner (accession number BC034634). Those plasmids were linearized, and digoxigenin-labeled probes were prepared by transcription using T7 or T3 RNA polymerase in the presence of DIG RNA labeling mixture. In situ hybridizations were performed as previously described (3). The stained tissues were incubated with 30% sucrose at 4 °C overnight, embedded in Tissue-Tek OCT compound and cryosectioned at 10 μm.

RESULTS

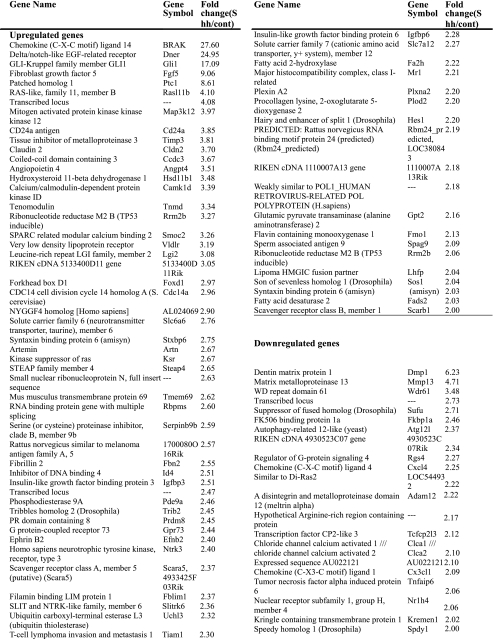

Identification of Shh Target Genes in UGS Mesenchyme—To identify Shh target genes in the mesenchyme of the developing prostate, we performed microarray analysis in triplicate using RNA from UGSM-2 cells cultured for 24 h in the presence or absence of Shh. Genes showing significantly different signal intensities (p < 0.05) and fold changes greater than ±2 following treatment with Shh were selected. A total of 89 genes were identified by the array: 68 were up-regulated by Shh and 21 were down-regulated (Table 1). Eighteen of the genes whose transcription was significantly altered by Shh in UGSM-2 cells, including 14 up-regulated genes and 4 down-regulated genes, were selected for further study (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Genes regulated by Shh in UGSM-2 cells after 24 h treatment

89 genes changed at least 2-fold between the 24-h control sample and 24-h Shh treatment samples listed according to fold change.

TABLE 2.

Shh-regulated expression in primary UGM cells and UGS tissues

|

Gene

|

Gene

expressiona

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Response to Shh

|

Response to cyclopamine

|

||

| Array | Primary UGM | UGS organ culture | |

| Gli1 | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ |

| Ptc1 | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ |

| Igfbp-6 | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ |

| Igfbp-3 | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ |

| Fbn2 | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ |

| Ntrk3 | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ |

| Agpt4 | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ |

| Dner | ↑ | ↑ | 0 |

| Hsd11b1 | ↑ | ↑ | 0 |

| Artn | ↑ | ↑ | 0 |

| Tnmd | ↑ | 0 | ↓ |

| Timp3 | ↑ | 0 | ↓ |

| Tiam1 | ↑ | 0 | ↓ |

| Plxna2 | ↑ | 0 | ↓ |

| BRAK | ↑ | 0 | ↓ |

| Fgf5 | ↑ | 0 | 0 |

| Dmp1 | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ |

| Mmp13 | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ |

| Rgs4 | ↓ | 0 | 0 |

| Sufu | ↓ | 0 | ↑ |

Note: gene expression induced by Shh (↑) is expected to be inhibited by cyclopamine (↓). ↑, increased expression; ↓, decreased expression; 0, no significant change. ↑ or ↓ signifies at least 2-fold statistically significant (p < 0.05) change in expression in replicate experiments.

Shh-regulated Expression in Primary Mesenchymal Cells and the UGS—To evaluate how well the target gene profile of the UGSM-2 cell line represents the general population of mesenchymal cells in the UGS, we isolated primary mesenchymal cells from the separated E16 UGS mesenchyme and cultured them in the presence or absence of Shh for 24 h. We then analyzed expression of Gli1, Ptc1, and the 18 validated target genes by reverse transcriptase-PCR. Of the 18 genes, 10 demonstrated Shh-regulated expression in the primary UGS mesenchyme cells (Table 2). We then analyzed expression of the 18 genes in intact E16 UGS cultured in serum-free media ± cyclopamine (28), an inhibitor of Hh signaling, to identify those genes whose expression is regulated by Hh signaling during prostate development. Thirteen exhibited significantly altered expression when Hh signaling was inhibited with cyclopamine. In each case, genes induced by Shh in the microarray (n = 10) showed repression when the UGS was exposed to cyclopamine and genes repressed by Shh (n = 3) were induced by exposure of the UGS to cyclopamine (Table 2).

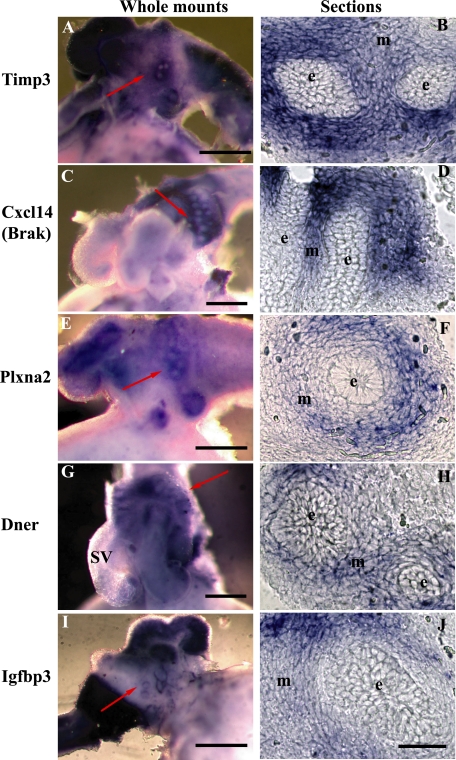

Hedgehog Target Gene Expression in the Newborn Prostate—We performed in situ hybridization to examine the expression of selected Hedgehog target genes in the newborn (P1) prostate. This time point was selected because of the robust and distinctive pattern of Shh and Gli1 expression in the nascent buds and adjacent mesenchyme, respectively (3). Expression of all five target genes examined (Timp3, Plxna2, Dner, Cxcl14, and Igfbp-3) exhibited mesenchyme-specific expression localized around the nascent buds, mimicking the expression of Ptc1 and Gli1 (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Localization of target gene expressions in the newborn prostate. Whole-mount in situ hybridization reveals focused domains of Timp3 (A), Cxcl14 (C), Plxna2 (E), Dner (G), and Igfbp3 (I) expression in the mesenchyme surrounding the nascent prostate buds. Sectioning confirms the expression of Timp3 (B), Cxcl14 (D), Plxna2 (F), Dner (H), and Igfbp3 (J) localized to the mesenchyme (m) surrounding the epithelial buds (e). Scale bar = 500 μm for A, C, E, G, and I. Scale bar = 40 μm for B, D, F, H, and J. Data are representative of 3 specimens per gene analyzed.

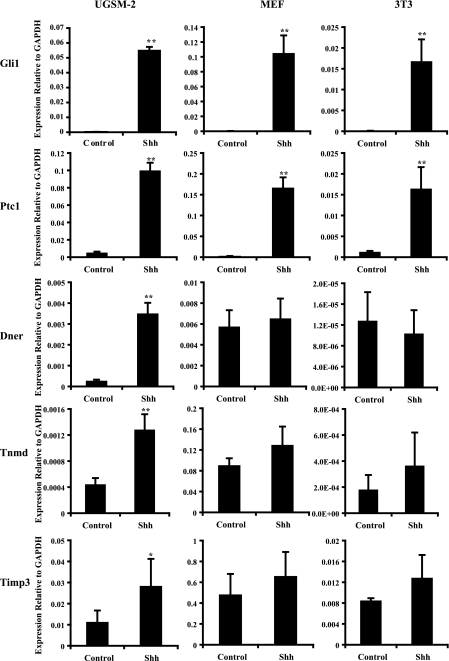

Prostate Selective Expression—To determine whether any of the 18 identified target genes exhibit prostate selective Hh-regulated expression, we examined their Shh-dependent expression in primary E13 WT MEFs and NIH3T3 cells. The cells were cultured with and without Shh, and expression of Gli1, Ptc1, and the 18 target genes was examined. Both Ptc1 and Gli1 exhibited robust Shh-induced expression in MEFs and NIH3T3 cells (Fig. 2). Fifteen of the 18 genes demonstrated Shh-regulated expression in MEFs and/or NIH3T3 cells (data not shown). One gene (Dner) that exhibited Shh-induced expression in both UGSM-2 cells and primary UGS mesenchymal cells was not responsive to Shh in either MEFs or NIH3T3 cells. Two additional genes (Tnmd and Timp3) that showed Shh-regulated expression in UGSM-2 cells but not in primary UGS mesenchymal cells also did not show significant Shh-induced change in expression in MEFs or NIH3T3 cells (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

UGSM-2 cells, MEF cells, and 3T3 cells were treated with 50 nm Shh. Gene expression was analyzed by real time PCR analysis on total RNA extracted after 24 h treatment. Gli1 and Ptc1 were induced in cell lines tested. Three genes (Dner, Tnmd, and Timp3) showed induced expression after Shh treatment in UGSM-2 cells, but not in MEF cells or 3T3 cells (n = 3; **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05).

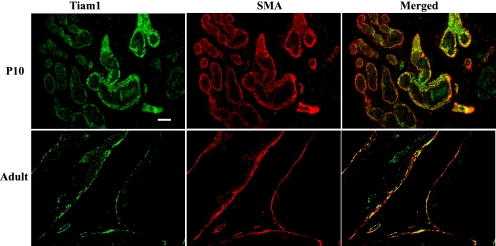

Differential Regulation of Shh-responsive Genes—Direct regulation of Shh target genes is believed to result from the combined activities of Gli1, Gli2, and Gli3. Smo regulates the activities of all three Gli genes by mechanisms that remain incompletely understood. To understand the convoluted actions of Hh signaling in simultaneously regulating proliferation, differentiation, and morphogenesis during development, there is considerable interest in determining the mechanisms by which differential regulation of Shh target genes is achieved in different cells. We first examined the concentration dependence of Shh-induced changes in expression of several of the newly identified Hh target genes and found that most followed the same pattern as Gli1 and Ptc1 with a dose-dependent expression that reached a plateau and remained elevated even with additional ligand (supplemental data Figs. S1 and S2). Tiam1 exhibited a uniquely different concentration dependence of expression. Expression increased to a maximum at 10–50 nm Shh and then progressively decreased to uninduced levels at higher concentrations (supplemental data Fig. S1). Localization of Tiam1 in the P10 and adult prostate by immunofluorescence staining shows expression co-localizing with smooth muscle actin in stromal cells surrounding the prostatic ducts (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3.

Tiam1 expression in the developing prostate. Immunofluorescence staining of Tiam1 and smooth muscle actin (SMA) were performed on sections of P10 and adult prostate. Expression of Tiam1 (green) co-localized with smooth muscle actin (red) expression. Scale bar = 100 μm.

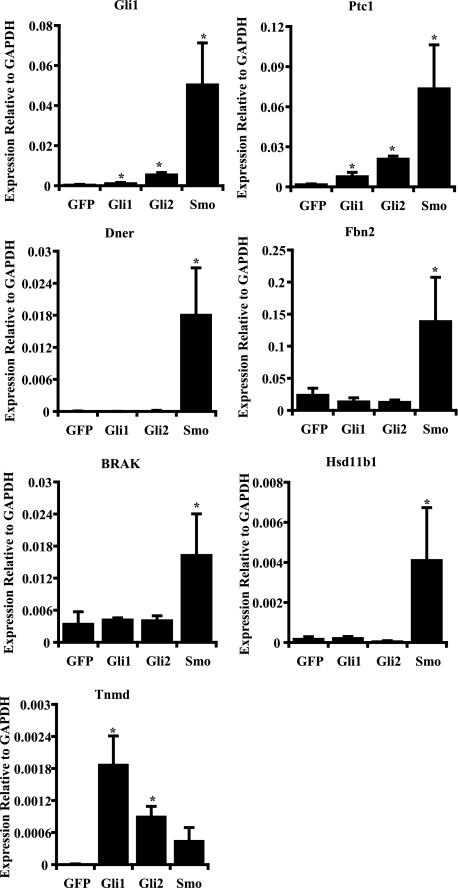

We next assayed the transcriptional response by transfecting UGSM-2 cells with an activated form of Smo, full-length Gli1, or an activated form of Gli2. All three manipulations would generally be considered methods of achieving Hh target gene activation and, indeed, the canonical target genes Gli1 and Ptc1 exhibited significantly increased expression in response to transfection with all three constructs. Overall, induced increases in expression were lowest following Gli1 transfection and greatest after Smo transfection. When we assayed for changes in expression of the 18 target genes using the same cDNA made from those cells, most of the genes exhibited consistent induction or repression by the three manipulations. This included Igfbp-6, Igfbp-3, Ntrk3, Agpt4, Artn, Timp3, Tiam1, Plxna2, Fgf5, Dmp1, Mmp13, Rgs4, and Sufu (data not shown). However, we uncovered some intriguing differences. Some of the target genes (Dner, Fbn2, Brak (Cxcl14), and Hsd11b1) were not induced by either Gli1 or Gli2 transfection, but were induced by Smo transfection. In striking contrast, Tnmd showed the highest level of induced expression with Gli1 transfection and the lowest level of induced expression with Smo transfection (Fig. 4).

FIGURE 4.

Target gene expression in UGSM-2 cells transfected with Hh pathway components. UGSM-2 cells were transfected with Gli1, activated Gli2, activated Smo, or green fluorescent protein alone. Expression of the selected 18 genes was analyzed by real time PCR on the extracted RNA from transfected cells (*, p < 0.05, n = 3). GFP, green fluorescent protein; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogeanse.

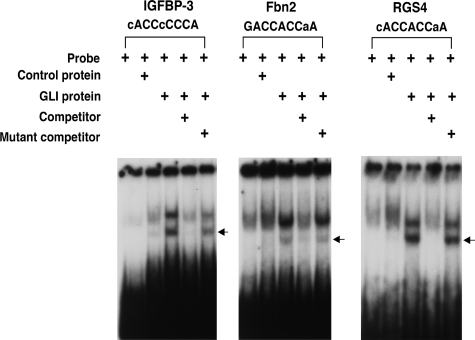

Gli Binding Elements in the Promoters of Shh Target Genes—The three Gli proteins share a 9-bp consensus binding sequence (GACCACCCA) (29). We performed in silico analysis of the remaining validated target genes and identified putative Gli-binding sites upstream of the promoter in 10 additional genes (Tnmd, Tiam1, Fbn2, Mmp13, Plxna2, Dner, Artn, Hsd11b1, Rgs4, and Igfbp-3). Each of the putative Gli binding sites contains at least 7-bp homology with the 9-bp consensus (GACCACCCA) (supplemental data Fig. S3). Electrophoretic mobility shift assays were performed to determine the ability of these 10 putative binding sites to interact with the DNA binding motif of Gli protein. The putative Gli-binding elements from the promoter region of target genes Igfbp-3, Fbn2, and Rgs4 bound Gli protein specifically (Fig. 5).

FIGURE 5.

Identification of Gli1-binding motifs in the 5′ region of the Shh target genes. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays demonstrated two shifted bands (arrows) in Igfbp-3, Fbn2, and Rgs-4 genes. Specific shifted bands were abrogated by non-radiolabeled oligonucleotide specific to each gene. Control protein or a mutant oligonucleotide DNA did not affect the mobility shift, indicating the specificity of the Gli binding interaction.

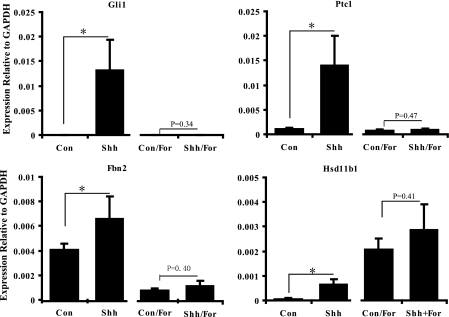

Unique Target Gene Response to PKA Activation—Fbn2 contains a bona fide Gli binding element but neither Gli1 nor an activated form of Gli2 is able to activate Fbn2 expression (Fig. 6). Because gene activation can be achieved by alleviating repression by Gli3 and Gli3 processing is regulated by PKA (30, 31), we examined the effect of the PKA activator forskolin on Shh-induced Fbn2 expression. Forskolin reduced basal expression and blocked Shh-induced expression of Fbn2, consistent with its regulation by Gli3 (Fig. 6). Hsd11b1 is another identified target gene that exhibits activation by Smo but not by either Gli1 or activated Gli2. Forskolin increased basal expression of Hsdllb1 but no further increase in expression was induced by Shh (Fig. 6).

FIGURE 6.

Regulation of target gene expression by forskolin treatment. UGSM-2 cells were treated with Shh in the presence or absence of forskolin. RNA were extracted after 24 h, followed by performing real time PCR to analyze selected gene expression (*, p < 0.05, n = 3). GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

DISCUSSION

We used RNA microarray analysis of an immortalized mesenchymal cell line to identify Shh-responsive genes in the fetal prostate. We could not perform a direct analysis of the cultured E16 UGS because the endogenous Hh ligand would obscure the effect of exogenous Shh peptide and the use of a chemical inhibitor such as cyclopamine could be complicated by nonspecific effects. We are able to isolate and culture the E16 UGS mesenchyme (3), but the yield of RNA from this is extremely low and would have required an amplification step before array analysis. We considered using freshly isolated E16 UGS mesenchymal cells cultured in monolayer, but our studies of freshly isolated cells suggest that there is significant variability in the growth and behavior of these mixed cell populations that could make validation of the array analysis problematic. Ultimately, we elected to use the previously characterized UGSM-2 cell line that we have shown recapitulates the androgen and Hh responsiveness of the normal UGS mesenchyme and can participate in glandular morphogenesis of the developing prostate (9). The time point selected for analysis of the transcriptional response to Hh ligand was based on our previously published studies characterizing the kinetics of induction of Ptc1, Gli1, and Hip in Shh-treated cells and on preliminary studies examining the expression of known target genes such as Igfbp-6 (25). These studies suggested that 24 h after Shh stimulation was the earliest time point that we could expect a robust transcriptional response of novel Hh target genes, a time point that might include both primary and secondary response genes.

To the extent that the UGS mesenchyme is a heterogeneous tissue layer, we expected that the transcriptional response of the UGSM-2 cells might not accurately represent the response of the intact UGS mesenchyme. We were surprised to find that 16 of 18 genes identified in the microarray as putative Hh target genes exhibited Hh-regulated expression in either primary UGS mesenchyme cells, the intact UGS or both. Even more remarkable, all five genes (Timp3, Plxna2, Dner, Igfbp-3, and Cxcl14) selected for analysis of expression in vivo exhibited mesenchyme-specific expression adjacent to sites of robust Shh expression reminiscent of the distribution of Gli1 and Ptc expression in the newborn prostate (3, 29). One explanation is that UGSM-2 cells faithfully represent the dominant Hh-responsive cell type in the E16 UGS mesenchyme. However, another possibility is that the target genes identified in the array are generic Hh target genes and not specific to the mesenchyme of the developing prostate. Several previous studies used microarrays to investigate the target genes of Shh signaling: Ingram et al. (32) identified 11 induced genes and 4 repressed genes in Shh-treated C3H/10T1/2 cells; Yoon et al. (21) identified Gli1-regulated genes in RK3E cells; Oliver et al. (33) identified 134 genes regulated by Shh in granule cell precursors; and Hochman et al. (34) treated C166 endothelial cells with Shh and identified 54 genes exhibiting at least 1.5-fold induction. Indeed, several genes shown to be targets of Hh regulation here were previously identified as Hh target genes in other cells or tissues. These include Camk1d, Foxd1, Igfbp-3, Igfbp-6, Trib2, Mr1, and Rgs4 (34). However, our studies identified several genes that had not been previously identified as Hh targets.

To identify genes for which regulation by Hh signaling is prostate selective, we examined expression of the validated genes in MEFs and NIH3T3 cells. Three genes (Dner, Tnmd, and Timp3) that exhibited a diminished response to Shh treatment in both cell lines may be considered as potentially prostate-selective Hh target genes, but this remains to be established by further studies.

Dner, Tnmd, and Timp3 have been studied in other contexts and have all been shown to have roles in growth regulation. Tnmd is a regulator of tenocyte proliferation (35); Timp3 has been shown to regulate cell proliferation, inflammation, and innate immunity; both Tnmd and Timp3 function as angiogenesis inhibitors (35–38). Dner has been previously characterized as a neuron-specific Notch ligand and is essential for precise cerebellar development by stimulating morphological differentiation of Bergmann glia (39). Our study provides the first evidence for its expression in the developing prostate.

Among the other putative target genes newly identified on the array but not necessarily prostate selective are genes related to Notch and Wnt signaling. Hes1 and Efnb2 are both known targets of Notch signaling, with the expression of Hes1 also having been shown to be dependent on Shh in tissues such as retina and cerebellum (40, 41). Another gene, Kremen1, is a Dickkopf receptor that negatively regulates the Wnt signaling pathway (42). These findings suggest previously unrecognized cross-talk or points of conversion between Hh signaling and the Wnt and Notch signaling pathways during prostate development. Another notable feature in the genes identified here are three involved in regulating angiogenesis, including Efnb2, Rgs4, and Angiopoietin-4 (Agpt4) (43–45).

Hh regulation of early target gene transcription is thought to be mediated by the activities of the three members of the Gli family whose combined activities are regulated by Smo and perhaps other members of the mammalian Hh signal transduction machinery by a combination of phosphorylation events, protein processing, and nuclear translocation. In previously published studies, we examined the transcriptional regulation of the canonical Hh target genes Gli1, Ptc1, and Hip in wild type, single Gli allele mutant, and double Gli allele mutant MEFs (25). Those studies demonstrated similar patterns of Hh ligand-induced transcription of Gli1 and Ptc1 in the different mutant cells, arguing for a common mechanism of regulation. But it is clear that other target genes are differentially regulated. How is this achieved? Presumably, a major mechanism of regulation is dependence on specific, albeit as yet unidentified transcriptional cofactors working in combination to influence the transcriptional machinery and produce a unique pattern of target gene activation. However, other mechanisms for differential gene regulation exist. In Drosophila, selective gene activation results from a differential responsiveness of target genes to a concentration gradient of Hh ligand. Our studies identify Tiam1 (T lymphoma invasion and metastasis 1), a guanine nucleotide exchange factor, as a gene whose Hh-regulated expression may be gradient dependent and it is notable that Tiam1 expression is found in a restricted zone of stroma around the ducts of the developing prostate. Expression of Hh target genes in the periductal stroma is not unexpected because Shh is expressed by the epithelium of the developing ducts, but co-localization with the band of smooth muscle actin expression around the ducts suggests the intriguing possibility that a restricted band of Tiam1 expression induced by the gradient of secreted Shh ligand plays a role in radial patterning of the duct and determining the location of smooth muscle induction.

Differential target gene regulation in mammals can also occur from varying affinities of the three different Gli factors for Gli binding sites in different promoter regions. Indeed, recent studies have shown a differential regulation of Ptc1 and Bcl2 in human epidermal cells that is attributed to relative affinities of Gli1 and Gli2 for the Gli binding sites in the promoters of the two genes (46, 47). Here we tested whether Gli1, Ptc1, and the non-canonical Hh target genes identified in our array are similarly responsive to retroviral transfection of UGSM-2 cells with activated Smo, Gli1, or activated Gli2. The data show that this is clearly not the case and, furthermore, reveal three distinctive response patterns among the genes tested. 1) Genes that are induced (or repressed) by all three constructs. Genes in this category include Gli1 and Ptc1 as well as Igfbp-6, Igfbp-3, Ntrk3, Agpt4, Artn, Timp3, Tiam1, Plxna2, Fgf5, Dmp1, Mmp13, Rgs4, and Sufu. 2) Genes that are induced by Smo but not by either Gli1 or Gli2. These genes include Dner, Fbn2, Brak, and Hsd11b1. 3) Genes such as Tnmd that are induced by Gli1 and Gli2 transfection but not by Smo.

There are likely a variety of reasons for the different patterns of response, but the data presented here provide a starting place for functional studies to examine this issue. Indeed, we explored the role of Gli3-mediated regulation in expression of two genes, Fbn2 and Hsd11b1, which exhibited Smo-induced expression but were not activated by either Gli1 or activated Gli2. The PKA activator forskolin enhances the proteolysis of Gli3 to generate a repressor form. As would be expected for a gene regulated by Gli3, Fbn2 induction by Shh was blocked by forskolin treatment. The induction of Hsd11b1 by Shh was also blocked by forskolin, whereas constitutive expression was increased, suggesting multiple roles for PKA in the regulation of Hsd11b1.

In previously published studies Igfbp-6 and Foxd1 have been shown to have conserved Gli1 binding motifs that were confirmed by gel shift binding assays (21). To determine whether any of our identified target genes might be regulated directly by Gli proteins, we examined the promoter regions of those genes. Putative Gli binding motifs were found in 10 of them. Functional Gli binding sites were found in 3 of them after performing gel shift assay.

Identification of mesenchymal target genes of Hh signaling in the developing prostate was undertaken to advance our studies of how Hh signaling regulates prostate budding and ductal morphogenesis. In addition to identifying specific Hh target genes, these studies provide the first evidence to our knowledge for cross-talk and/or convergence between Hh signaling and the Wnt and Notch pathways in the fetal prostate and offer novel opportunities to begin elucidating the importance of these connections in regulating growth. These findings are particularly relevant to ongoing studies of Hh signaling in prostate cancer. We have previously shown that paracrine Hh signaling occurs in human prostate cancer and can promote tumor growth in a xenograft model (8). In more recent studies, we have shown that expression of multiple target genes identified here correlate significantly with Hh signaling in specimens of human prostate cancer, but not benign prostate tissue, suggesting a re-activation of fetal signaling mechanisms in cancer.3 It is hoped that identification of these Hh target genes and the connections of Hh signaling with the Wnt and Notch pathways, both implicated in prostate cancer, will advance the effort to devise new targeted therapies for advanced disease not amenable to ablative therapy.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants P50 DK065303 and RO1 DK056238. This work was also supported by the Robert and Delores Schnoes Chair in Urologic Research. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement”in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Table S1 and Figs. S1–S3.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: Shh, Sonic Hedgehog; UGS, urogential sinus; MES, 4-morpholineethanesulfonic acid; Ptc1, Patched 1; MEF, mouse embryonic fibroblast; Smo, smoothened; PKA, protein kinase A; IGFBP, insulin-like growth factor binding protein.

A. Shaw, J. Gipp, and W. Bushman, unpublished observations.

References

- 1.Ingham, P. W., and McMahon, A. P. (2001) Genes Dev. 15 3059–3087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Podlasek, C. A., Barnett, D. H., Clemens, J. Q., Bak, P. M., and Bushman, W. (1999) Dev. Biol. 209 28–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lamm, M. L., Catbagan, W. S., Laciak, R. J., Barnett, D. H., Hebner, C. M., Gaffield, W., Walterhouse, D., Iannaccone, P., and Bushman, W. (2002) Dev. Biol. 249 349–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freestone, S. H., Marker, P., Grace, O. C., Tomlinson, D. C., Cunha, G. R., Harnden, P., and Thomson, A. A. (2003) Dev. Biol. 264 352–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berman, D. M., Desai, N., Wang, X., Karhadkar, S. S., Reynon, M., Abate-Shen, C., Beachy, P. A., and Shen, M. M. (2004) Dev. Biol. 267 387–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hooper, J. E., and Scott, M. P. (2005) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 6 306–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang, B. E., Shou, J., Ross, S., Koeppen, H., De Sauvage, F. J., and Gao, W. Q. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 18506–18513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fan, L., Pepicelli, C. V., Dibble, C. C., Catbagan, W., Zarycki, J. L., Laciak, R., Gipp, J., Shaw, A., Lamm, M. L., Munoz, A., Lipinski, R., Thrasher, J. B., and Bushman, W. (2004) Endocrinology 145 3961–3970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaw, A., Papadopoulos, J., Johnson, C., and Bushman, W. (2006) Prostate 66 1347–1358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaw, A., and Bushman, W. (2007) J. Urol. 177 832–838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chuang, P. T., and McMahon, A. P. (1999) Nature 397 617–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ingham, P. W., and Placzek, M. (2006) Nat. Rev. Genet. 7 841–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Callahan, C. A., Ofstad, T., Horng, L., Wang, J. K., Zhen, H. H., Coulombe, P. A., and Oro, A. E. (2004) Genes Dev. 18 2724–2729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eichberger, T., Regl, G., Ikram, M. S., Neill, G. W., Philpott, M. P., Aberger, F., and Frischauf, A. M. (2004) J. Investig. Dermatol. 122 1180–1187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roelink, H., Porter, J. A., Chiang, C., Tanabe, Y., Chang, D. T., Beachy, P. A., and Jessell, T. M. (1995) Cell 81 445–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krishnan, V., Pereira, F. A., Qiu, Y., Chen, C. H., Beachy, P. A., Tsai, S. Y., and Tsai, M. J. (1997) Science 278 1947–1950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu, S. C., Grindley, J., Winnier, G. E., Hargett, L., and Hogan, B. L. (1998) Mech. Dev. 70 3–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teh, M. T., Wong, S. T., Neill, G. W., Ghali, L. R., Philpott, M. P., and Quinn, A. G. (2002) Cancer Res. 62 4773–4780 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahlapuu, M., Enerback, S., and Carlsson, P. (2001) Development 128 2397–2406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Izraeli, S., Lowe, L. A., Bertness, V. L., Campaner, S., Hahn, H., Kirsch, I. R., and Kuehn, M. R. (2001) Genesis 31 72–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoon, J. W., Kita, Y., Frank, D. J., Majewski, R. R., Konicek, B. A., Nobrega, M. A., Jacob, H., Walterhouse, D., and Iannaccone, P. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 5548–5555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gaur, T., Rich, L., Lengner, C. J., Hussain, S., Trevant, B., Ayers, D., Stein, J. L., Bodine, P. V., Komm, B. S., Stein, G. S., and Lian, J. B. (2006) J. Cell. Physiol. 208 87–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.He, J., Sheng, T., Stelter, A. A., Li, C., Zhang, X., Sinha, M., Luxon, B. A., and Xie, J. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 35598–35602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lipinski, R. J., Cook, C. H., Barnett, D. H., Gipp, J. J., Peterson, R. E., and Bushman, W. (2005) Dev. Dyn. 233 829–836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lipinski, R. J., Gipp, J. J., Zhang, J., Doles, J. D., and Bushman, W. (2006) Exp. Cell Res. 312 1925–1938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doles, J. D., Vezina, C. M., Lipinski, R. J., Peterson, R. E., and Bushman, W. (2005) Prostate 65 390–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garrett, W. M., and Guthrie, H. D. (1998) Biochemica 1 17–20 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cooper, M. K., Porter, J. A., Young, K. E., and Beachy, P. A. (1998) Science 280 1603–1607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kinzler, K. W., and Vogelstein, B. (1990) Mol. Cell. Biol. 10 634–642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang, B., Fallon, J. F., and Beachy, P. A. (2000) Cell 100 423–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dai, P., Akimaru, H., Tanaka, Y., Maekawa, T., Nakafuku, M., and Ishii, S. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274 8143–8152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ingram, W. J., Wicking, C. A., Grimmond, S. M., Forrest, A. R., and Wainwright, B. J. (2002) Oncogene 21 8196–8205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oliver, T. G., Grasfeder, L. L., Carroll, A. L., Kaiser, C., Gillingham, C. L., Lin, S. M., Wickramasinghe, R., Scott, M. P., and Wechsler-Reya, R. J. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100 7331–7336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hochman, E., Castiel, A., Jacob-Hirsch, J., Amariglio, N., and Izraeli, S. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 33860–33870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Docheva, D., Hunziker, E. B., Fassler, R., and Brandau, O. (2005) Mol. Cell. Biol. 25 699–705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gill, S. E., Pape, M. C., and Leco, K. J. (2006) Dev. Biol. 298 540–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spurbeck, W. W., Ng, C. Y., Strom, T. S., Vanin, E. F., and Davidoff, A. M. (2002) Blood 100 3361–3368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shukunami, C., Oshima, Y., and Hiraki, Y. (2005) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 333 299–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eiraku, M., Tohgo, A., Ono, K., Kaneko, M., Fujishima, K., Hirano, T., and Kengaku, M. (2005) Nat. Neurosci. 8 873–880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang, Y., Dakubo, G. D., Thurig, S., Mazerolle, C. J., and Wallace, V. A. (2005) Development 132 5103–5113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dakubo, G. D., Mazerolle, C. J., and Wallace, V. A. (2006) J. Neurooncol. 79 221–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mao, B., Wu, W., Davidson, G., Marhold, J., Li, M., Mechler, B. M., Delius, H., Hoppe, D., Stannek, P., Walter, C., Glinka, A., and Niehrs, C. (2002) Nature 417 664–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gerety, S. S., and Anderson, D. J. (2002) Development 129 1397–1410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Albig, A. R., and Schiemann, W. P. (2005) Mol. Biol. Cell 16 609–625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Olsen, M. W., Ley, C. D., Junker, N., Hansen, A. J., Lund, E. L., and Kristjansen, P. E. (2006) Neoplasia 8 364–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Regl, G., Kasper, M., Schnidar, H., Eichberger, T., Neill, G. W., Philpott, M. P., Esterbauer, H., Hauser-Kronberger, C., Frischauf, A. M., and Aberger, F. (2004) Cancer Res. 64 7724–7731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bigelow, R. L., Chari, N. S., Unden, A. B., Spurgers, K. B., Lee, S., Roop, D. R., Toftgard, R., and McDonnell, T. J. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 1197–1205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.