Abstract

Release of endothelial cells from contact-inhibition and cell cycle re-entry is required for the induction of new blood vessel formation by angiogenesis. Using a combination of chemical inhibition, loss of function, and gain of function approaches, we demonstrate that endothelial cell cycle re-entry, S phase progression, and subsequent angiogenic tubule formation are dependent upon the activity of cytosolic phospholipase A2-α (cPLA2α). Inhibition of cPLA2α activity and small interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated knockdown of endogenous cPLA2α reduced endothelial cell proliferation. In the absence of cPLA2α activity, endothelial cells exhibited retarded progression from G1 through S phase, displayed reduced cyclin A/cdk2 expression, and generated less arachidonic acid. In quiescent endothelial cells, cPLA2α is inactivated upon its sequestration at the Golgi apparatus. Upon the stimulation of endothelial cell proliferation, activation of cPLA2α by release from the Golgi apparatus was critical to the induction of cyclin A expression and efficient cell cycle progression. Consequently, inhibition of cPLA2α was sufficient to block angiogenic tubule formation in vitro. Furthermore, the siRNA-mediated retardation of endothelial cell cycle re-entry and proliferation was reversed upon overexpression of an siRNA-resistant form of cPLA2α. Thus, activation of cPLA2α acts as a novel mechanism for the regulation of endothelial cell cycle re-entry, cell cycle progression, and angiogenesis.

The vascular endothelium consists of a monolayer of endothelial cells that lines the luminal surface of all blood vessels in vivo. The endothelium actively participates in a variety of key vascular processes such as the regulation of vascular tone and blood fluidity. In addition, the endothelium regulates the formation of new blood vessels by the process of angiogenesis in development, tissue repair, and tumor vascularization (1, 2). The mature endothelium consists of contact-inhibited confluent monolayers of cells that reside in the G0 phase of quiescence. Upon loss of cell-cell contacts, endothelial cells re-enter the cell cycle and proliferate. This entry of endothelial cells into the cell cycle from G0 is a critical component of the angiogenic response and the formation of new capillaries from pre-existing blood vessels (1, 2). Thus, the inhibition of endothelial cell proliferation has great potential for the treatment of diseases involving unwanted blood vessel formation.

The phospholipase A2 (PLA2)3 family of enzymes hydrolyze the sn-2 group of glycerophospholipids to concomitantly release free fatty acids and lysophospholipids (3). The PLA2 family represents a diverse family of enzymes that can be divided into three main groups as follows: the group IV cytosolic PLA2 (cPLA2), the group VI Ca2+-independent PLA2 (iPLA2), and the secretory PLA2 enzymes (4). The cPLA2 group of enzymes consists of at least six members (cPLA2α,-β,-γ,-δ, -ε, and -ζ), of which cPLA2α is the most extensively characterized. cPLA2α is Ca2+-sensitive and translocates to intracellular membranes upon agonist stimulation and cytosolic Ca2+ elevation utilizing an N terminal Ca2+-dependent lipid binding (C2) domain (5-7). Upon membrane binding, cPLA2α preferentially cleaves phospholipids containing arachidonic acid (AA) at the sn-2 position to liberate free AA (3). As such, cPLA2α is seen as the rate-limiting enzyme in receptor-mediated AA release (8). Proliferating, nonconfluent endothelial cells release much greater levels of arachidonic acid and prostaglandin than quiescent confluent cells (9-11), which has been attributed to elevated cPLA2α activity. In quiescent confluent cells, cPLA2α is inactivated upon sequestration at the Golgi apparatus and is subsequently released and activated in proliferating cells (11, 12). Despite this, the actual function of this differential regulation of cPLA2α activity has not been defined.

Here we identify a novel role for cPLA2α activation in the regulation of endothelial cell cycle progression. Upon the loss of cell-cell contacts and the induction of endothelial cell proliferation, activation of cPLA2α is required for the induction of cyclin A expression and efficient progression through G1 and S phases. Our work and work by others have previously shown that the activity of iPLA2 also influences the progression of endothelial cells through S phase (13-15). Here we demonstrate that cPLA2α and iPLA2 work cooperatively to influence endothelial cell cycle progression with cPLA2α providing a stimulation- and Ca2+-dependent source of lipid metabolites required for controlling endothelial cell cycle progression in response to monolayer disruption or growth factor stimulation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture and Materials—Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were isolated from human umbilical cords as described previously (16, 17). Human dermal microvascular endothelial cells (HDMEC) were purchased from Promocell. Cells were cultured in endothelial cell basal medium supplemented with endothelial cell growth factor kit 2 (Promocell). All cells were grown on 0.1% (w/v) gelatin-coated culture-ware and were not used in excess of four passages. The following antibodies were purchased: anti-αII-spectrin (C3; sc-48382) and anti-cPLA2α (C20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology); anti-PCNA (610664), anti-cyclin A (611268), and anti-cdk2 (610145; BD Transduction Laboratories); anti-caspase-3, anti-caspase-7, anti-caspase-9, and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (Cell Signaling Technologies); horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Pierce); and Alexafluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes). Anti-GRASP55 antibodies were provided by F. Barr (University of Liverpool, UK). Arachidonyl trifluoromethyl ketone (AACOCF3) was purchased from Biomol. Pyrrolidine, AZ-1/compound 22, and Wyeth-1 were kind gifts from M. H. Gelb (University of Washington, Seattle). l-α-Phosphatidylcholine (P3841), l-α-lysophosphatidylcholine (L1381), AA (A9673), and l-α-phosphatidylethanolamine (P7693) were from Sigma. The original cPLA2α construct was obtained from M. Gelb as a GFP fusion protein. Two point mutations were introduced into the siRNA-1-binding site on cPLA2α (centered around nucleotide 774) using QuickChange III site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) and designated 774 cPLA2α. The mutant sequence was subcloned into pIRES-GFP vector and assessed by DNA sequencing, and siRNA resistance was confirmed by co-expression in HEK293 cells. All other reagents were obtained from Sigma or Invitrogen unless otherwise stated.

AA Release Assay—This assay was performed as described previously (11). Briefly, HUVECs were cultured to the required density in either 6-well or 60-mm2 dishes and labeled for 24 h with 0.5 μCi/ml [3H]AA in growth media. Subconfluent, confluent, or wounded cells were washed with PBS and incubated with cPLA2α inhibitors for 15 min or overnight as indicated. For measurement of passive AA release, media were collected following overnight incubation (18 h), cleared by centrifugation, and assayed for radioactivity by liquid scintillation counting. For ionophore-stimulated release, cells were incubated with 5 μm A23187 in HEPES/Tyrode Buffer (X) containing 2 mm CaCl2, supplemented with 0.3% (w/v) fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin for 15 min. Cleared supernatant containing released AA was assayed for radioactivity by liquid scintillation as were total cell lysates prepared by lysis of cells in 0.5% Triton X-100. AA release under each condition was expressed as a percentage of total cellular radioactivities.

Proliferation ELISA—HUVEC proliferation rates were assessed using a 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdUrd) incorporation-based ELISA (Roche Diagnostics). Cells were seeded at 1 × 103 cells per well (0.55 × 103 cells/cm2) in 96-well plates, grown for 24 h, incubated for 16 h with inhibitors and BrdUrd, and then processed according to manufacturer's instructions. Proliferation was also determined after 48 h of growth by assessing viable cell numbers using the MTS-based CellTiter® AQueous nonradioactive cell proliferation assay (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Microscopy and Quantification—Phase contrast images were acquired using an Olympus CK2 inverted microscope (10× lens) linked to an Olympus OM-1 camera. Deconvolution fluorescence microscopy was performed using an Olympus IX-70 inverted fluorescence microscope (63 × 1.5 oil immersion lens) and DeltaVision deconvolution system (Applied Precision Inc.). Individual optical sections of 0.2 μm were generated from 15 iterative cycles of deconvolution. Some images were collected using a Zeiss LSM510 META Axiovert 200 M confocal microscope. Multiple comparisons were performed using oneway analysis of variance and Tukey's post-test analysis with GraphPad Prism software.

Flow Cytometry—Subconfluent HUVECs were cultured for 16 h in the presence or absence of inhibitor. Cells were then harvested, fixed in 70% ice-cold ethanol, and incubated with propidium iodide (50 μg/ml) and RNase A (20 μg/ml) for 3 h. DNA content was then assessed using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and the percentage of cells in each phase of the cell cycle analyzed using Modfit software (Verity Software House). For some experiments G0-synchronized confluent HUVECs, serum-starved overnight, were seeded at subconfluent density in the presence or absence of inhibitors for 14 h. Cells were then either chased in fresh media containing inhibitors for various time points prior to processing as above, or siRNA-treated cells were pulsed with media supplemented with 10 μm BrdUrd for 30 min prior to harvesting, fixation, and analysis for BrdUrd incorporation.

Biochemistry—Lysate preparation and Western analysis were performed as described previously (11). Immunoprecipitations were performed overnight at 4 °C using protein G-Sepharose (Upstate Biotechnology, Inc.), 3 μg of antibody, and 500 μg of total protein in 1% Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer (50 mm Tris/HCl, 150 mm NaCl, 0.5 mm EDTA, 0.5 mm EGTA, 1% Nonidet P-40, pH 7.4). Samples (20 μg of protein or total bead volume) were resolved for 60 min at 30 mA/gel on 10% SDS-PAGE mini-gels using a discontinuous buffer system (18). For immunoblotting, protein was transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes for 3 h at 300 mA (19). Membranes were blocked in 5% (w/v) nonfat milk in PBS for 30 min and then incubated overnight with primary antibody (1:500) at room temperature. After incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-goat IgG (1:3000) for 1 h, immunoreactive bands were visualized using a West Pico enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection kit (Pierce). Images were captured on a Fuji Film Intelligent dark box II image reader. Band intensities were determined densitometrically using Aida (Advanced Image Data Analyzer) 2.11 software.

RNA Interference—HUVECs were transfected with either no siRNA (control), 10-50 nm nontargeting control siRNA (mock; D-001210-01; Dharmacon), or 10-50 nm annealed cPLA2α siRNA (siRNA-1, 30774; or siRNA-2, 30953; Ambion) for 4 h using either Lipofectamine 2000 or RNAiMAX transfection reagent (Invitrogen). siRNA against iPLA2-VIA has been described previously (15). Cells were recovered for 48 h prior to lysis. For cPLA2α supplementation experiments, cells were transfected with siRNA-1 or scrambled sequence using RNAiMAX for 24 h before harvesting and transfection with mutant 774 cPLA2 by electroporation as described previously (12). Cells were plated onto coverslips, recovered for 24 h, and processed for cyclin A, Ki67, and GFP expression analysis by immunofluorescence microscopy.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy—Immunofluorescence was performed as described previously (11). Briefly, cells grown on coverslips were fixed in 10% (v/v) formalin in neutral buffered saline (HT50-1-128; Sigma) for 5 min at 37 °C. After permeabilization with 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100 for 5 min, cells were refixed (5 min), washed with PBS, and then incubated in 50 mm ammonium chloride for 10 min. Following PBS washes, nonspecific binding sites were blocked with 5% (v/v) donkey serum for 3 h. Cells were incubated overnight with primary antibody followed by the appropriate secondary antibodies. Finally, coverslips were mounted on microscope slides in Fluoromount-G mounting medium (Southern Biotech). For analysis of BrdUrd incorporation, cells were fixed in ice-cold 80% ethanol for 20 min followed by a 20-min fixative step in 100% ethanol on ice. Cells were then incubated with 2 n HCl, 0.5% Triton X-100 for 20 min at room temperature followed by a wash in 100 mm sodium tetraborohydrate. Cells were then processed as above with the indicated antibodies.

Differentiation and Migration Assays—To assess HUVEC differentiation, 1 × 105 cells were seeded in 24-well dishes coated with 100 μl of Matrigel (BD Biosciences). Cells were incubated in the presence or absence of inhibitor for 16 h prior to imaging. Tubule length was quantified using ImageJ software (rsb.info.nih). For migration assays, HUVECs (5 × 104 cells) were seeded in serum-free media to the top chamber of 24-well modified Boyden chambers (3 μm pores; Transwell-Costar Corp.). Cells were allowed to migrate toward serum-containing media for 16 h in the presence of absence of inhibitor. Migrated cells were fixed, stained with DAPI, and then counted.

Angiogenesis Assay—Co-cultures of HUVECs seeded on a bed of human fibroblasts (TCS Cellworks) were cultured for 7 days in the presence or absence of inhibitor. Tubules were fixed, stained, and imaged by phase contrast microscopy. Tubule length was quantified using ImageJ software.

RESULTS

cPLA2α Mediates Endothelial Cell Proliferation—We have previously demonstrated a requirement for both iPLA2- and cPLA2α-mediated AA release in the regulation of HUVEC proliferation (11, 15). We sought to further examine the contribution of cPLA2α to endothelial cell proliferation by measuring BrdUrd incorporation into DNA in the presence of concentrations of inhibitors that maximally block cPLA2α activity. To initially define concentrations of inhibitors that maximally inhibited cPLA2α activity, passive AA release generated by proliferating HUVECs was quantified following 18 h of incubation with varying concentrations of the cPLA2α-specific inhibitors pyrrolidine and Wyeth-1 (Wy-1) (20, 21) or the cPLA2α/iPLA2 inhibitor AACOCF3 (22). Maximal inhibition of cPLA2α-mediated AA release was achieved with between 2.5 and 5 μm pyrrolidine and 2.5 and 5 μm Wy-1 with no further increase in inhibition observed at higher concentrations (Fig. 1A). AACOCF3 also maximally inhibited AA release at 2.5 μm, although the extent of this inhibition was much greater than with pyrrolidine or Wy-1 alone, consistent with the combined inhibition of both cPLA2α- and iPLA2 activities, which contribute to the pool of released AA by proliferating endothelial cells. The modest reduction in long term AA release following cPLA2α inhibition may reflect both the assay conditions, where radiolabeled AA may be produced by non-cPLA2α-dependent mechanisms that cannot be controlled for (such as normal membrane turnover) and the contribution of the cPLA2α-generated pool to this process.

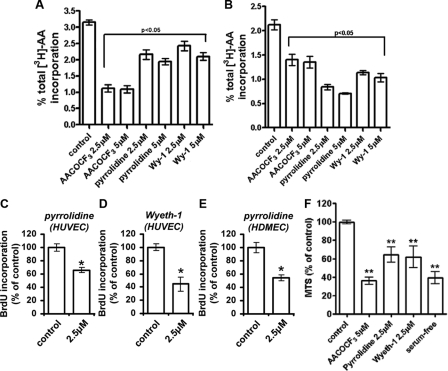

FIGURE 1.

cPLA2α mediates endothelial cell proliferation. A, passive [3H]AA release from proliferating prelabeled HUVECs was assessed by liquid scintillation counting following 18 h of growth in the presence of the indicated inhibitors. All treatments significantly reduce AA release, p < 0.05. B, A23187-induced [3H]AA release from subconfluent HUVECs following a 15-min preincubation with the indicated inhibitors was determined by liquid scintillation and expressed as a percentage of total 3H incorporation. Results are expressed as a percentage of total 3H incorporation (n = 3). Quantitation of HUVEC (C and D) and HDMEC (E) growth in the presence or absence of 2.5 μm pyrrolidine (C and E) or Wyeth-1 (D) was for 16 h (n = 6, ± S.E.). Proliferation was determined using a colorimetric ELISA based on BrdUrd (BrdU) incorporation, as described under “Experimental Procedures,” and was expressed as a percentage of proliferation in the presence of the inhibitor. F, quantification of VEGF-dependent HUVEC proliferation after 48 h in the presence of the indicated inhibitors was determined by MTS assay (n = 5). *, p < 0.01 versus control. **, p < 0.01 versus VEGF-stimulated control cells.

However, ionophore treatment selectively liberates AA derived from pools accessible to the Ca2+-dependent isoforms of PLA2 and can thus be considered selective for the activation of cPLA2α in HUVECs. Under these conditions, similar to the overnight release assay, short term (15 min) preincubation with 2.5 μm pyrrolidine or Wy-1 was also sufficient to maximally inhibit Ca2+-induced AA release induced by the ionophore A23187 (Fig. 1B). AACOCF3 appeared less effective at reducing stimulated AA release, and the varying extent of the inhibition by the various drugs may reflect the differing initial bioavailabilities of these structurally distinct compounds. A role for cPLA2α in the regulation of endothelial cell proliferation was then confirmed upon incubation of HUVECs with 2.5 μm pyrrolidine or Wy-1 (Fig. 1, C and D). Maximal inhibition of cPLA2α activity was sufficient to significantly retard HUVEC proliferation. Furthermore, incubation with 2.5 μm pyrrolidine also significantly inhibited HDMEC proliferation (Fig. 1E) suggesting that a role for cPLA2α in the regulation of cellular proliferation is common to other endothelial cell types. The anti-proliferative effect of cPLA2α inhibition could not be attributed to increased cell death as the concentration of inhibitors used did not affect cell viability (as assessed by trypan blue exclusion and annexin V binding) or caspase-3 activation and did not promote the cleavage of αII-spectrin or poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (data not shown). However, varying levels of inhibitor cytotoxicity were observed at doses exceeding those used in this study (data not shown).

Specific analysis of the vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A) pathway showed that cPLA2α activity is required for the induction of cellular proliferation by this important angiogenic stimulus. Indeed, VEGF-A-mediated cell turnover was reduced by 40-50% in the presence of the various cPLA2α inhibitors as determined by MTS-based assay of relative cell number after 48 h of growth (Fig. 1F). Furthermore, incubation with 5 μm AACOCF3 and the combined inhibition of cPLA2α and iPLA2 reduced HUVEC proliferation to levels similar to those found in the absence of growth factor and serum, suggesting that cPLA2α and iPLA2 may function cooperatively during VEGF-induced endothelial cell proliferation.

cPLA2α-mediated Proliferation Is Essential for Angiogenesis—Angiogenic tubule formation is a multistep process involving the proliferation, migration, and differentiation of endothelial cells (1, 2). Consequently, conversion of endothelial cells from quiescence to a proliferative state is vital to angiogenesis (1). As cPLA2α activity is required for endothelial cell proliferation (Fig. 1), we hypothesized that cPLA2α activity plays a key role in angiogenesis. Endothelial cell tubule formation can be assessed using co-culture assays in vitro. In this assay, HUVECs were seeded on a bed of human dermal fibroblasts and cultured for 7 days. Under these conditions endothelial cells form tubules with patent lumens, reminiscent of mature capillaries (23). Tubule formation in this assay involves the combined proliferation, migration, and differentiation of endothelial cells. Incubation with pyrrolidine reduced tubule length to 32.8 ± 4.8% of controls (Fig. 2A). Wy-1 also showed a similar ability to reduce tubule formation (Fig. 2A). Thus cPLA2α activity regulates the formation of new blood capillaries by angiogenesis in in vitro assays.

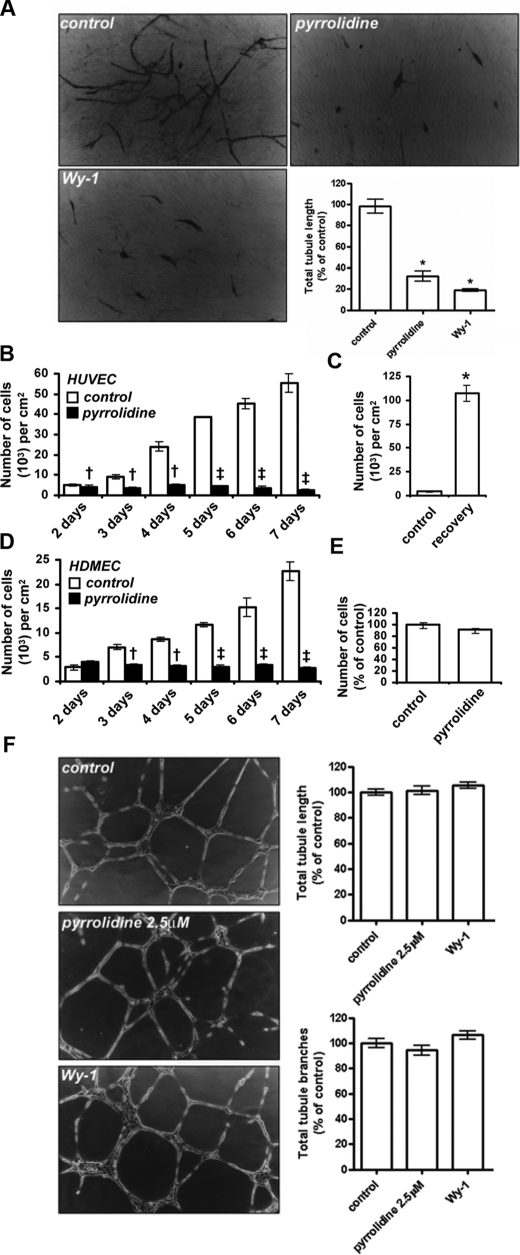

FIGURE 2.

cPLA2α mediates endothelial cell angiogenesis. A, phase contrast images of capillary-like tubules formed in co-culture assays over 7 days of growth in the presence or absence of 2.5 μm pyrrolidine or 2.5 μm Wyeth-1 (n = 3 ± S.E.) and quantification of total tubule lengths (n = 6 ± S.E.). B, quantification of HUVEC cell numbers over a 7-day growth period in the absence (empty bars) or presence (black bars) of 2.5 μm pyrrolidine (n = 3, ± S.E.) is shown. C, cells were grown in the presence of 2.5 μm pyrrolidine for 5 days and cell numbers quantified prior to inhibitor washout (control) and then after inhibitor washout and 8 days of recovery (recovery- n = 3 ± S.E.). D, quantification of HDMEC cell numbers over a 7-day growth period in the absence (empty bars) or presence (black bars) of 2.5 μm pyrrolidine (n = 3, ± S.E.) is shown. †, p < 0.05 versus uninhibited; ‡, p < 0.001 versus uninhibited; *, p < 0.01 versus control. E, quantification of serum-induced migration in the presence or absence of 2.5 μm pyrrolidine (n = 3 ± S.E.) is shown. F, phase contrast images of HUVECs incubated on Matrigel for 16 h in the presence or absence of 2.5 μm pyrrolidine or 2.5 μm Wy-1 (n = 3 ± S.E.) and quantification of total tubule lengths and total branch numbers (n = 6 ± S.E.) are shown. All results are representative of at least three separate experiments.

To further examine the importance of cPLA2α activity for endothelial cell proliferation during angiogenesis and the long term effects of pyrrolidine on cell viability, endothelial cell numbers were determined by counting over 7 days of culture (Fig. 2B). HUVECs seeded at a density of 3000 cells/cm2 were given 24 h to settle and then were cultured for 7 days in the presence or absence of 2.5 μm pyrrolidine. At 24-h intervals, cells were harvested and counted (Fig. 2B). Control cell numbers increased as a function of time, whereas cells grown in the presence of pyrrolidine remained at a constant density. Inhibition of growth was not because of cell death as incubation with pyrrolidine for 7 days did not affect cell viability, and endothelial cell morphology was unaffected by cPLA2α inhibition (data not shown). Furthermore, this block in cell proliferation was entirely reversible as cells grown in the presence of pyrrolidine for 5 days recovered upon washout of inhibitor, with a 24-fold increase in cell density after 8 days of recovery (Fig. 2C). Similarly, culture in the presence of pyrrolidine also significantly blocks HDMEC growth (Fig. 2D). Thus, long term inhibition of cPLA2α had a profound effect on cell growth and the ability of endothelial cells to form angiogenic tubules.

We also assessed the role cPLA2α in endothelial cell migration, and differentiation. HUVEC migration, as assayed using Boyden chambers (23), was not affected by incubation with pyrrolidine (Fig. 2E). In addition, pyrrolidine did not inhibit endothelial cell migration or differentiation, as studied using Matrigel assays (Fig. 2F). Here a fixed number of cells were grown on an appropriate substratum for 24 h. Sufficient cells are present to allow migration and differentiation into tubules even in the absence of cell proliferation (23). In this assay, HUVEC tubule formation, branching number, and branch length were not affected by inhibition of cPLA2α with either pyrrolidine or Wy-1 (Fig. 2F). As cPLA2α does not play a role in HUVEC migration or differentiation (Fig. 2, E and F), inhibition of endothelial cell proliferation caused by blocking cPLA2α activity (Fig. 1, C and F) must be sufficient to block angiogenic tubule formation in co-culture assays (Fig. 2A). The role of cPLA2 in mediating this proliferation defect was examined in further detail below.

cPLA2α Modulates Endothelial Cell S Phase Progression and Cell Cycle Residence—The role of cPLA2α in the regulation of cell cycle progression was assessed by analyzing the cell cycle distribution of endothelial cells using flow cytometry. Proliferating endothelial cells were cultured in the presence or absence of 2.5 μm pyrrolidine for 16 h. Cells were then stained with propidium iodide, and cellular DNA content was analyzed by FACS. As determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorter, the number of cells in S phase was markedly reduced upon cPLA2α inhibition (Fig. 3, A and B). As a result, significantly more cells resided in the G0-G1 phases of the cell cycle, suggesting that cPLA2α modulates G1 to S phase progression. To examine the rate of progression of HUVECs through the cell cycle upon cPLA2α inhibition, serum-starved, quiescent confluent cells (G0 synchronized) were trypsinized, re-seeded to subconfluent density, and allowed to re-enter the cell cycle for 14 h (optimized for maximal cell cycle re-entry, data not shown) in the presence or absence of pyrrolidine (2.5 μm). Cells were then incubated in fresh media with or without pyrrolidine for various time points (0, 3, 6, 9 h), harvested at the indicated times, ethanol-fixed, stained with propidium iodide, and analyzed by flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 3C, treatment of cells with pyrrolidine resulted in a significant increase (∼10%) in the number of cells in G0-G1 phase, despite a time-dependent reduction in the total number of cells in G0-G1. Importantly, the distribution of cells in S phase was also altered upon cPLA2α inhibition over the 9-h chase period (Fig. 3C). Pyrrolidine-treated cells displayed both reduced numbers of cells in S phase (∼5% reduction in total cell number) and a delay in reaching S phase peak (∼6 h post-chase) compared with control cells (S phase peak reached ∼3-4 h post-chase). As the total number of cells in S phase under control conditions is quite small (10-15% total cell number), this reduction following cPLA2α inhibition represents a significant decrease in proliferative potential. Additionally, the total number of BrdUrd-positive cells at time 0 (14 h after release from G0) was significantly reduced (∼33% reduction) upon treatment with pyrrolidine (Fig. 3D). Taken together, these results indicate that cPLA2α participates in the regulation of endothelial S phase progression.

FIGURE 3.

Role of cPLA2α activity in endothelial cell cycle progression. A and B, subconfluent HUVECs, grown in the presence or absence of 2.5 μm pyrrolidine for 16 h, were stained with propidium iodide and analyzed by flow cytometry to determine cellular DNA content. Cell cycle distribution was then determined using Modfit software and plotted (n = 3, ± S.E.). C, G0-synchronized HUVECs were re-seeded subconfluently and allowed to re-enter the cell cycle for 14 h in the presence or absence of 2.5 μm pyrrolidine. Cells were then processed at various subsequent time points with or without inhibitor prior to staining with propidium iodide and analysis by flow cytometry as in A. The percentage of G0-G1 (left) and S phase cells (right) was determined using Modfit and expressed as a percentage of total cell number (n = 4; *, p < 0.05 versus respective control; **, p < 0.01 versus control 0 h). D, cells prepared as in C were incubated with media supplemented with BrdUrd (Brdu, 10 μm) for 45 min, 14 h after re-seeding. This was followed by ethanol fixation, staining with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-BrdUrd antibody, and analysis by flow cytometry. BrdUrd incorporation was expressed as a percentage of total cells and compared with confluent monolayer uptake (n = 4; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01). E, subconfluent HUVECs grown in the presence or absence of 2.5 μm pyrrolidine for 18 h were analyzed for Ki67 levels. Membranes were re-probed for GRASP55 to show equal loading. Relative immunoreactivities were determined using Aida densitometry software and plotted (n = 3, ± S.E.). *, p < 0.01 versus control. F, subconfluent HUVECs grown in the presence or absence of 2.5 μm pyrrolidine for 24 h were analyzed for PCNA, cyclin A, and cdk2 levels by Western blotting. Relative immunoreactivities were determined using Aida densitometry software and plotted (n = 3, ± S.E.). All results are representative of at least three separate experiments. *, p < 0.01 versus control.

Ki67 is a nuclear protein expressed in the G1, S, G2, and mitotic phases of the cell cycle but not in the G0 phase of quiescence (24, 25). It is commonly used as a marker for identifying proliferating cells, and a decrease in its expression is indicative of reduced proliferative rates (26). Inhibition of cPLA2α significantly reduced Ki67 expression in subconfluent HUVECs (Fig. 3E), indicating that fewer cells were in the G1-M phase. Slower passage through the cell cycle may have led to the accumulation of quiescent cells displaying reduced Ki67 levels. Thus, cPLA2α activity plays a key role in G1 to S phase progression and maintenance of endothelial cell cycle residence.

Transition from G1 to S phase requires the assembly and activation of the DNA replication complex to initiate DNA synthesis. S phase entry and replication complex formation can be monitored by assessing cellular levels of the replication clamp proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA). PCNA expression is low throughout the cell cycle until early S phase and the initiation of replication complex formation (27, 28). PCNA expression was unaffected by cPLA2α inhibition (Fig. 3F), suggesting that inhibition of S phase progression was after S phase entry and replication complex formation. Activation of pre-assembled replication complexes and initiation of DNA synthesis is mediated by the cyclin A-cdk2 complex in early S phase. Mammalian cells cannot synthesize DNA nor progress through S phase in the absence of cyclin A-cdk2 activity (29, 30). Cyclin A expression increases in early S phase in conjunction with the accumulation of cdk2 in the nucleus to form active cyclin A-cdk2 complexes.

Upon cPLA2α inhibition, cyclin A levels were reduced to ∼26% of controls, potentially accounting for the block in G1-S phase progression and inhibition of DNA synthesis seen previously (Fig. 3F). Furthermore, inhibition of cPLA2α also resulted in reduced cdk2 expression levels (∼29% of control) as often occurs when S phase progression is artificially blocked (31, 32). Thus, in the absence of cPLA2α activity endothelial cells enter S phase and express similar levels of PCNA relative to control cells; however, they are unable to proceed through S phase to G2-M as efficiently, demonstrating that cPLA2α modulates the progression of endothelial cells through S phase.

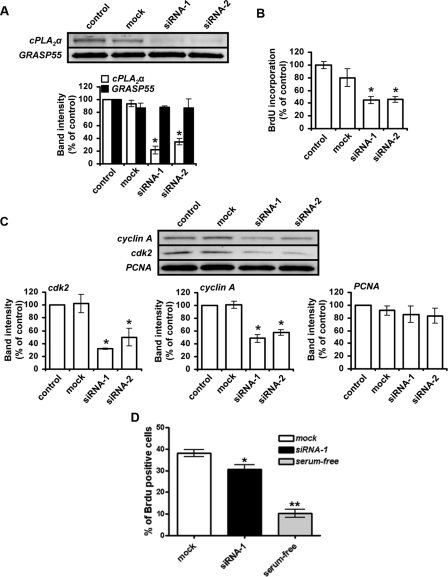

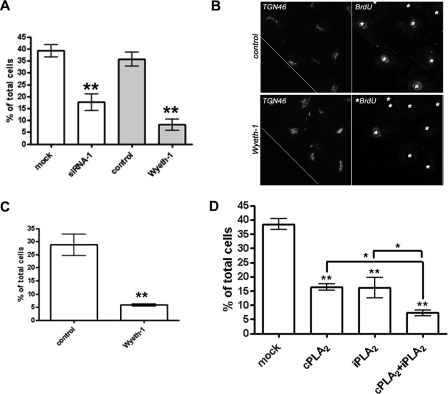

siRNA-mediated Knockdown of Endogenous cPLA2α—The previous experiments are consistent with the hypothesis that cPLA2α plays a central role in the control of endothelial cell cycle residence and S phase progression. However, to exclude the possibility that the effects of cPLA2α inhibitors were nonspecific, we used RNA interference. Consistent with the inhibitor studies, knockdown of endogenous cPLA2α by either 78 or 68% of control levels using two different cPLA2α-specific siRNA duplexes (Fig. 4A) significantly inhibited HUVEC proliferation (Fig. 4B). Relative to nontargeting siRNA controls (mock), the rate of BrdUrd incorporation into HUVEC DNA was reduced by 44 or 43% upon transfection with siRNA-1 or siRNA-2, respectively (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, the siRNA-mediated knockdown of endogenous cPLA2α also resulted in reduced cellular levels of cyclin A and cdk2 while having no effect on PCNA expression (Fig. 4C). Additionally, cell cycle progression of siRNA-treated cells was examined by measurement of BrdUrd incorporation using flow cytometry. Subconfluent siRNA-transfected cells, released from G0 14 h previously, were pulsed with BrdUrd (10 μm) for 45 min prior to fixation, allowing an indication of S phase cell numbers to be established. Under these conditions, cPLA2α siRNA-treated cells showed a significant reduction (to ∼20% of scrambled siRNA (mock) levels) in the total number of cells in S phase and in cells undergoing active cell cycle progression (Fig. 4D). Thus, cPLA2α activity plays a central role in the regulation of endothelial cell proliferation and S phase progression by modulating the expression of cell cycle proteins and influencing cell cycle residence time.

FIGURE 4.

siRNA-mediated knockdown of endogenous cPLA2α expression inhibits endothelial cell proliferation. A, HUVECs were transfected with either no siRNA (control), nontargeted control siRNA (mock), or cPLA2α-targeted siRNA (siRNA-1 and siRNA-2). 48 h after transfection, cells were seeded at a subconfluent density and allowed to proliferate for 16 h prior to lysis and analysis of cPLA2α levels by Western blotting. Membranes were re-probed for GRASP55 to show equal protein loading. Relative amounts of cPLA2α and GRASP immunoreactivity were determined using Aida densitometry software and then plotted (n = 3, ± S.E.). B, ability of transfected cells to proliferate was assessed using a colorimetric ELISA based on BrdUrd (BrdU) incorporation, as described under “Experimental Procedures” (n = 6, ± S.E.). All results are representative of three separate experiments. *, p < 0.05 versus mock. C, HUVECs were transfected with either no siRNA (control), nontargeted control siRNA (mock), or cPLA2α-targeted siRNA (siRNA-1 and siRNA-2). 48 h after transfection, cells were seeded at a lower density and allowed to proliferate for 16 h prior to lysis. The levels of cdk2, cyclin A, and PCNA expression in siRNA-transfected HUVECs were then analyzed by Western blotting, and the resulting band immunoreactivity was determined using Aida densitometry software (n = 3, ± S.E.). All results are representative of at least three separate experiments. *, p < 0.05 versus mock. D, G0-synchronized siRNA-treated (control or cPLA2α-targeted siRNA) HUVECs were re-seeded subconfluently and allowed to re-enter the cell cycle for 14 h. Cells were pulsed with BrdUrd-containing media, fixed, stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate-anti-BrdUrd, and analyzed by flow cytometry. The percentage of BrdUrd-positive cells was expressed as a percentage of the total cell number (n = 4; *, p < 0.05 versus respective control).

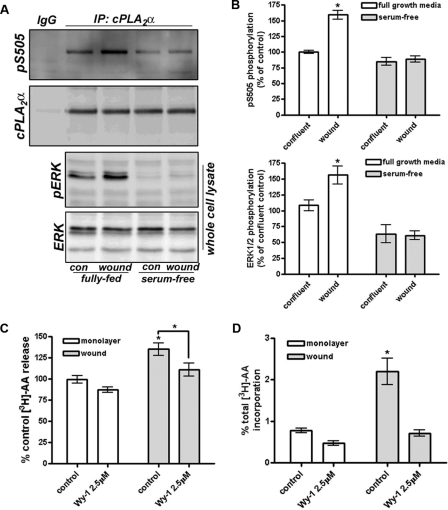

Activation of cPLA2α by Release from the Golgi Is Critical to S Phase Progression—We have previously demonstrated that cPLA2α activity is reduced in confluent monolayers of endothelial cells that are in the G0 phase of quiescence (11), and we proposed that cPLA2α is inactivated in confluent endothelial cells upon its sequestration at the Golgi apparatus and exclusion from its intracellular membrane substrate (12). Wounding of confluent monolayers provided the stimulus for cPLA2α to be released from the Golgi apparatus and allow access its phospholipid substrate (11). To confirm that cPLA2α is activated at the wound border following release from the Golgi apparatus, confluent monolayers were scratch-wounded in a grid pattern and recovered for 18 h prior to lysis. Following immunoprecipitation, the phosphorylation status of cPLA2α on serine 505 was assessed by Western blotting as cPLA2α can be activated downstream of multiple signal transduction cascades upon phosphorylation of serine 505 by ERK1/2. Wounding and recovery of HUVECs resulted in the growth factor-dependent phosphorylation of cPLA2 consistent with the increased phosphorylation and activation of ERK1/2 (Fig. 5, A and B). Serum-starved HUVECs exhibited both reduced phospho-ERK levels and reduced phosphorylation on the critical Ser-505 residue of cPLA2. Importantly, the wounding and recovery of HUVEC monolayers also resulted in the increased release of AA during the recovery period (Fig. 5C). Recovered cells also displayed a dramatically increased capacity to release AA upon stimulation with the Ca2+ ionophore A23187; this release was blocked by inhibition of cPLA2α with Wyeth-1 (2.5 μm; Fig. 5D). These results are consistent with the release of cPLA2 from the Golgi apparatus being critical for the activation of the enzyme.

FIGURE 5.

cPLA2 is activated at the wound border. A, confluent HUVEC monolayers were wounded and allowed to recover for 16 h in the presence or absence of serum and growth factors. Cell lysates were prepared and subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) of cPLA2. Bound proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and Western-blotted for phosphorylated serine 505 and total cPLA2. Lysates were also assessed for phosphorylated and total ERK1/2. con, control. B, quantification of phosphoserine 505 and phospho-ERK levels from six independent experiments. p < 0.05, n = 6. C and D, confluent HUVECs were loaded with [3H]AA overnight, wounded, and allowed to recover for 16 h in the presence or absence of 2.5 μm Wy-1. C, released [3H]AA was assessed by liquid scintillation. D, recovered cells were also stimulated with A23187 (5 μm, 15 min), and released [3H]AA was measured. *, p < 0.05, n = 3.

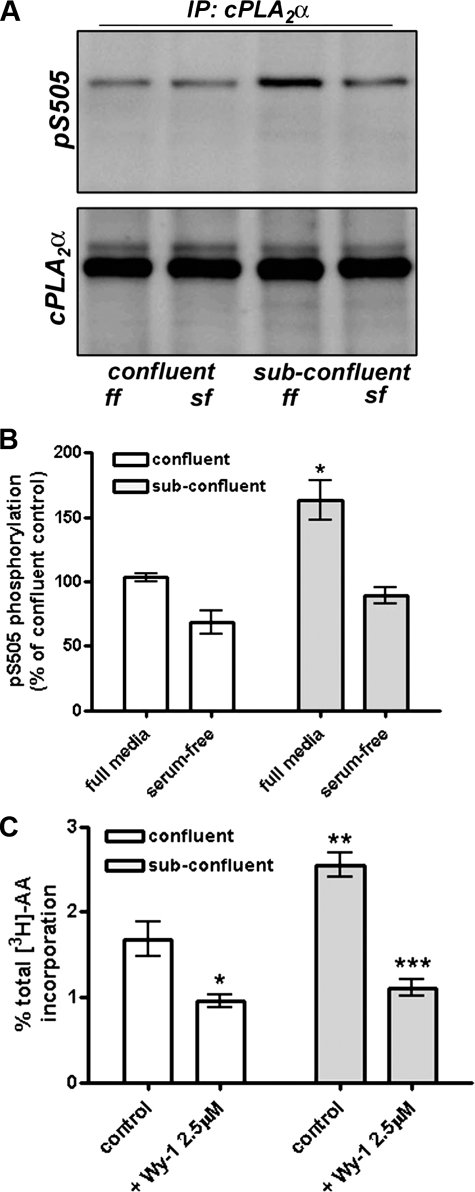

Furthermore, subconfluent, actively proliferating endothelial cells display elevated levels of activated cPLA2α compared with quiescent cells, as assessed by Western blotting of cPLA2α immunoprecipitates for phosphorylated serine 505 (Fig. 6A). Again, the elevated phosphorylation status of cPLA2α was dependent on the presence of growth factors in the media (Fig. 6, A and B). As reported previously (10), subconfluent endothelial cells also show a cPLA2α-dependent elevation in Ca2+-induced AA release compared with confluent HUVECs (Fig. 6C). Thus, cPLA2α is consistently activated in proliferating, but not quiescent, endothelial cells, and this correlates with AA release.

FIGURE 6.

The phosphorylation and activity of cPLA2 are elevated in subconfluent endothelial cells. A, confluent or subconfluent HUVECs were incubated in full growth media (ff) or under serum-free conditions (sf) for 4 h prior to lysis. Lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-cPLA2 antibody and bound proteins assessed by Western blotting for phosphorylated serine 505 or total cPLA2α. B, quantification of phosphorylated serine 505 levels from four independent levels is shown. p < 0.01, n = 4. C, A23187-stimulated (5 μm, 15 min) [3H]AA release from confluent and subconfluent cells was measured in the presence or absence or Wyeth-1 (2.5 μm, 30 min) and expressed as a percentage of total 3H incorporated. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 versus control; ***, p < 0.001 versus control subconfluent levels; n = 3.

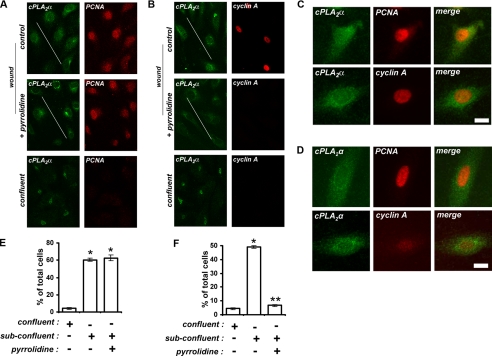

As cPLA2α modulates endothelial cell proliferation and S phase progression, we hypothesized that release from the Golgi and activation of cPLA2α would be required for re-entry of quiescent endothelial cells back into the cell cycle. Upon mechanical wounding of confluent monolayers, cells at the wound borders enter into the cell cycle from G0, proliferate, and migrate into the denuded areas. After 24 h of recovery, HUVECs at the wound border (indicated by the diagonal line) begin to express PCNA and cyclin A at high levels as they enter and progress through the cell cycle (Fig. 7, A and B). As reported previously (11), cells at the wound border underwent relocation of cPLA2α from the Golgi apparatus to the more diffuse staining of subconfluent HUVECs, indicating activation of cPLA2α (Fig. 7, A-D). This activation of cPLA2α would explain the elevated levels of AA released upon mechanical wounding of confluent endothelial cells shown in Fig. 6 (10). Importantly, release from the Golgi and activation of cPLA2α were critical to the induction of cyclin A expression (Fig. 7, A-D). In confluent HUVEC monolayers mechanically wounded and recovered for 24 h in the presence of 2.5 μm pyrrolidine, cPLA2α had relocated in cells at the wound border, similar to un-inhibited cells (Fig. 7, A-D). Quantification of the number of cells expressing high levels of nuclear PCNA revealed that inhibition of cPLA2α activity had no effect on PCNA up-regulation upon wounding (Fig. 7E), consistent with replication complex formation. However, the number of cells expressing high levels of nuclear cyclin A at the wound border fell from ∼49 to 7% (i.e. 7-fold) in the presence of pyrrolidine (Fig. 7F). Highly expressing cells were easily distinguishable as their cyclin A nuclear fluorescence intensity was consistently ∼4-fold than low expressing cells. Upon cPLA2α inhibition, the number of cells expressing high levels of cyclin A at the wound border fell to the levels seen with quiescent confluent monolayers (Fig. 7, B and F).

FIGURE 7.

Release of cPLA2α from the Golgi is critical for endothelial cell cycle entry and S phase progression. A-C, HUVECs in confluent monolayers and at wound borders (indicated by the diagonal bar) were cultured in the absence or presence of 2.5 μm pyrrolidine for 24 h prior to fixation. cPLA2α and either PCNA (A, C, and D) or cyclin A (B, C, and D) were then detected by confocal immunofluorescence microscopy. C and D show higher power images of wound border cells grown in the absence (C) or presence (D) of pyrrolidine and stained as indicated. E and F, quantification of the number of cells expressing high levels of nuclear PCNA (E) and cyclin A (F) from confluent monolayers or at wound borders upon recovery in the presence or absence of pyrrolidine. All results are representative of at least three separate experiments. *, p < 0.001 versus confluent cells; **, p < 0.001 versus uninhibited subconfluent cells.

A similar reduction in cyclin A-positive cells at the wound border was also found in cPLA2α siRNA- and Wyeth-1-treated cells (Fig. 8A). Furthermore, only cells at the wound border exhibited BrdUrd incorporation that was significantly inhibited by Wyeth-1 (2.5 μm) treatment (Fig. 8, B and C). We have previously demonstrated a role for iPLA2 in the control of HUVEC proliferation and progression through S phase. Thus, we sought to examine whether there was a cooperative role for the two phospholipases A2 in the control of S phase entry after monolayer wounding. BrdUrd incorporation was examined by immunofluorescence microscopy in wound-recovered HUVECs treated with siRNA to a scrambled sequence, cPLA2α (siRNA-1), iPLA2 (15), or cPLA2α and iPLA2 siRNA together. Consistent with previous findings, siRNA knockdown of cPLA2α reduced the number of BrdUrd-positive cells at the wound border (Fig. 8D). Treatment with the iPLA2 siRNA duplexes also resulted in an ∼55% reduction in cells incorporating BrdUrd at the wound border. Importantly, the simultaneous knockdown of both cPLA2 and iPLA2 inhibited BrdUrd incorporation by ∼80% in an additive manner (Fig. 8D). These results suggest that both Ca2+-dependent and Ca2+-independent phospholipase A2 isoforms may cooperate to coordinate the response of endothelial cells to various proliferative stimuli.

FIGURE 8.

S phase re-entry of wound border cells is dependent on cPLA2α activity. A, confluent HUVECs treated with mock siRNA or siRNA-1 were wounded, recovered for 18 h, fixed, and stained for cyclin A. Positive cells at the wound border were visualized by confocal microscopy, counted, and expressed as a percentage of total wound border cells. siRNA-treated cells were compared with wounded cells recovered in the presence or absence of Wyeth-1 (2.5 μm). Results are compiled from at least three separate experiments. **, p < 0.01. B, wounded cells recovered for 18 h in the presence or absence of Wyeth-1 (2.5 μm) were incubated with BrdUrd (BrdU, 10 μm) for 30 min prior to fixation and processing for BrdUrd incorporation, TGN46 immunoreactivity, and DAPI staining by confocal microscopy. Nuclei are indicated by *. C, quantification of the number of BrdUrd-positive cells at the wound border are expressed as a percentage of total cell number. Results are compiled from at least three separate experiments. **, p < 0.01. D, HUVECs were treated with mock siRNA alone or together with siRNA-1 (cPLA2) or iPLA2 siRNA. Indicated cells were co-transfected with siRNA to both cPLA2 and iPLA2. After 48 h, cells were wounded, recovered for 18 h, and incubated with media supplemented with BrdUrd (10 μm) for 30 min. Cells were ethanol-fixed and processed for TGN46 expression and BrdUrd incorporation before staining with DAPI. BrdUrd-positive cells at the wound border were counted and expressed as a percentage of total wound border cell number (results are taken from nine coverslips processed over three separate experiments; **, p < 0.01 versus control; *, p < 0.05 from cPLA2α or iPLA2 siRNA alone).

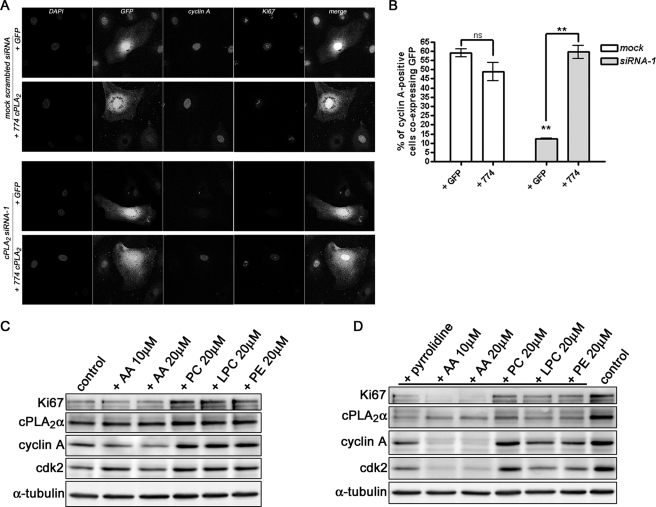

To demonstrate the specificity of the cPLA2α siRNA phenotype, the heterologous expression of an siRNA-resistant form of cPLA2α (774 cPLA2) using a vector containing an internal ribosome entry site-GFP sequence was found to rescue the proliferation deficit in siRNA-treated subconfluent HUVECs (Fig. 9A). A significant increase (∼6-fold) in the number of cyclin A-positive cells was evident upon restoration of cPLA2α levels using the expression plasmid (Fig. 9B). Ki67 levels were also elevated under these conditions (Fig. 9A).

FIGURE 9.

Overexpression of siRNA-resistant cPLA2α, but not AA addition, recovers cyclin A expression. A, HUVECs mock-or siRNA-1-transfected were electroporated with pIRES-GFP-774 cPLA2α construct (774 cPLA2) or empty vector and plated onto coverslips. 24 h later, cells were fixed and processed for GFP, cyclin A, and Ki67 expression analysis by confocal microscopy. DAPI, DAPI. B, cells positive for both cyclin A and GFP were quantified and expressed as a percentage of total GFP-positive cells. Images are representative of three separate experiments. ns, not significant. **, p < 0.01. C, subconfluent HUVECs were treated with the indicated concentrations of AA, PC, LPC, or l-α-phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) for 48 h prior to lysis and analysis of Ki67, cPLA2α, cyclin A, cdk2, or α-tubulin levels by Western blotting. D, subconfluent HUVECs were treated and analyzed as in C, except pyrrolidine was added during the 48-h incubation period. Also shown is a control, mock-treated lysate. Images are representative of at least four separate experiments.

We have previously shown that the addition of exogenous AA to pyrrolidine-treated HUVECs was able to partially rescue the proliferation defect induced by cPLA2α inhibition (11). Here we sought to assess whether AA could rescue other alterations in the cell cycle. Although re-expression of cPLA2α was able to rescue the decrease in cyclin A and Ki67 levels induced by depletion of cPLA2α, we sought to examine whether the application of the cPLA2α metabolites, AA or l-α-lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC), could similarly rescue the expression of these key cell cycle proteins. Subconfluent proliferating HUVECs were treated with pyrrolidine together with either 10 μm AA, 20 μm AA, 20 μm LPC, 20 μm l-α-phosphatidylcholine (PC), or l-α-phosphatidylethanolamine for 48 h prior to analysis of cyclin A, cdk2, and Ki67 levels by Western blotting. As shown in Fig. 9C, AA unexpectedly reduced cyclin A expression while increasing the expression of cdk2 in control cells. However, addition of either PC, LPC, or l-α-phosphatidylethanolamine also increased the basal levels of cyclin A and cdk2, together with Ki67 indicating an increase in proliferation. Interestingly, only the addition of crude brain PC could completely reverse and/or prevent the cell cycle defects induced by cPLA2α inhibition, restoring both cyclin A and cdk2 levels (Fig. 9D). Similar findings were seen with siRNA-treated HUVECs (data not shown). Why neither AA nor LPC was able to rescue the expression of these key S phase proteins remains unclear, but it may implicate a crucial role for the cPLA2α protein itself or its modulation of cellular phospholipid content, as critical to the control of cell cycle progression.

Thus, under our experimental conditions, cell cycle re-entry of endothelial cells is at least partially dependent on cPLA2α activation. The Ca2+-dependent translocation and activation displayed by cPLA2α may allow it to preferentially respond to stimuli such as vessel damage or growth factors. Indeed, the contribution of cPLA2α to regulating HUVEC proliferation appears more prominent in conditions where active detachment of cell-cell contacts is required by the cell prior to cell cycle re-entry (i.e. the ∼19% decrease in BrdUrd positive cells evident upon trypsinization and subconfluent re-seeding in Fig. 4D versus the ∼55% decrease evident following wounding in Fig. 8C). Thus, the activation of cPLA2α following monolayer disruption represents a novel mechanism mediating cyclin A-cdk2 expression and regulating S phase progression in endothelial cells. These results suggest that the Ca2+-dependent activation of cPLA2α is an important step in mediating endothelial cell proliferation in damaged blood vessels as demonstrated by the disruption of angiogenic tubule formation upon inhibition of cPLA2α.

DISCUSSION

This study shows that cPLA2α activation helps to regulate endothelial cell S phase progression and cell cycle entry. First, after mechanical wounding of confluent monolayers, endothelial cells at the wound borders release cPLA2α from the Golgi apparatus resulting in its activation. Second, cPLA2α activation is required for the elevation of cyclin A and cdk2 levels and subsequent S phase progression. Without active cPLA2α, the passage of endothelial cells through the early phases of the cell cycle (G1 through S to early M) is retarded, which is sufficient to interfere with long term angiogenic tubule formation. Thus, cPLA2α activation is a requirement for the efficient escape of quiescent endothelial cells from G0 and entry into the cell cycle. Other studies have implicated arachidonic acid metabolites in the control of G1 to S phase progression of cells (33-35); however, our findings provide the first evidence for the central role of cPLA2α itself in cyclin A expression, S phase progression, and cell cycle entry. A role for the protein itself is further validated by the failure of AA or LPC, the two major products of cPLA2α lipase function, to rescue cyclin A or cdk2 levels, despite previously being shown to partially rescue proliferation (11). Furthermore, in Chinese hamster ovary cells and neuroblastoma N2A cells, cPLA2α activity is elevated during mid/late G1 and following G1 to S phase transition (36); and in rat thyroid cells, the cPLA2α-dependent production of glycerophosphoinositol is required for receptor-mediated proliferation, independent of AA metabolism pathways (37).

In addition, we found that inhibition of cPLA2α in other cell types (saphenous vein smooth muscle cells, MCF-7 carcinoma cells, and epithelial HeLa cells) dose-dependently blocked cellular proliferation (data not shown), suggesting that the role of cPLA2α activity in S phase progression is common to other cell types. However, the precise roles of AA and its downstream products as well as lysophospholipids in regulating proliferation still require clarification. This is partially due to technical issues with lipid stability and also cellular requirements for lipid by-products to be produced close to their sites of action for efficient downstream activity (i.e. AA and cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase enzymes) (38-40). Despite this, inactivation of cPLA2α by sequestration at the Golgi apparatus is unique to endothelial cells with this phenomenon not evident in other cell types examined (e.g. HeLa, Madin-Darby canine kidney cells, A549, saphenous vein smooth muscle, and EA.hy.926 cells; data not shown).

Endothelial cells undergo the contact-inhibition of proliferation at confluence and become quiescent. As cPLA2α activity is a requirement for cell cycle re-entry, the existence of a readily releasable pool of cPLA2α in quiescent endothelial cells could be utilized to allow rapid cell cycle re-entry upon the loss of cell-cell contacts. The role that serine phosphorylation plays in regulating both cPLA2α activity and its release from the Golgi apparatus requires defining and could represent an important target for modulating phospholipid turnover. This is highlighted by the recent finding that phosphorylation of cPLA2α on serine 727 disrupted binding to p11 and annexin A2 allowing the enzyme to access its phospholipid substrate (41). Another unique function of endothelial cells is their ability to proliferate, migrate, and differentiate to form new capillaries during angiogenesis. The induction of this process is important in wound healing and critical for solid tumor growth, resulting in anti-angiogenic drugs being one of the most promising avenues of anti-cancer therapies (42-45). The re-entry of quiescent endothelial cells into the cell cycle is critical to activate the angiogenesis program (1, 2), and we have shown that inhibition of cPLA2α was sufficient to prevent angiogenic tubule formation, due solely to defects in the endothelial cell proliferation machinery. As such, targeting of endothelial cPLA2α, either alone or in combination with anti-iPLA2-VIA therapy, could represent a new approach to inhibit tumor neovascularization. Indeed, cPLA2α activity and the generation of LPC were recently identified as crucial events in the protection of endothelial cells against radiation-induced apoptosis and may represent a new target for modulating the radiosensitivity of the endothelium (46).

We had previously demonstrated that inhibition of group VIA iPLA2 (iPLA2-VIA), but not iPLA2-VIB or secretory PLA2, also blocked endothelial cell S phase progression and cell proliferation (15). Our work now suggests that both cPLA2α and iPLA2-VIA play distinct roles in the regulation of endothelial cell cycle progression. Here we show that products of both enzymes are required for the efficient release of endothelial cells from contact inhibition and re-entry into the cell cycle. Thus, in vivo, cells could sense the products (i.e. AA, lysophospholipids, or as suggested by our results, a reduction in membrane phospholipids) of multiple PLA2s to determine their readiness for progression into S phase; this would provide a mechanism to coordinate the amount of phospholipid required by a cell to successfully progress though cellular division. Previous studies have linked phosphatidylcholine metabolism to cell cycle regulation, and its incorporation is an S phase-specific event (47-49). In a recent study, changes to membrane fluidity caused by alteration to iPLA2 activities were hypothesized to be responsible for the growth defects seen upon iPLA2 inhibition; inhibition of the Ca2+-independent isoform of PLA2 led to an increase in membrane PC and resulted in G1 phase arrest (13, 14). Furthermore, it has been reported that excess PC can stimulate iPLA2-VIA activity, providing a mechanism for the ability of PC to recover the proliferation defect induced by cPLA2α inhibition (50). Additionally, in contrast to cPLA2, the activity of iPLA2-VIA appears to be required for the migration of HUVECs as well as their proliferation,4 which represents an important difference between their cellular activities and represents an area of future study. Defining how changes in phospholipase activities and the subsequent defects in phospholipid metabolism impact upon the cell cycle is crucial to utilizing this pathway as a therapeutic target.

However, it remains unclear whether cPLA2α and iPLA2-VIA regulate cellular proliferation by distinct or overlapping coordinated mechanisms. Initial studies suggest that cPLA2α and iPLA2-VIA have a synergistic effect on cell proliferation, and this may reflect both their different cellular localization (i.e. Golgi versus cytoplasm, respectively) and sites of their preferred substrates (i.e. endoplasmic reticulum/perinucleus versus plasma membrane, respectively), as well as their varied modes of activation. These variations may allow a cell to subtly coordinate its proliferative response to intracellular and extracellular cues by manipulating cellular lipids. The challenge will be to define the precise mechanisms by which cPLA2α and other phospholipase A2 enzymes regulate cell cycle progression.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. H. Gelb for kindly providing the cPLA2-GFP construct, pyrrolidine, and Wyeth-1. We also thank G. J. Howell for assistance with all aspects of bioimaging.

This work was supported by a Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council Ph.D. studentship (to S. P. H.), a Yorkshire Cancer Research pump priming grant (to S. P. H. and J. H. W.), a British Heart Foundation project grant (to S. P. and J. H. W.), a Wellcome Trust project grant (to S. P. and J. H. W.), and a Wellcome Trust equipment award to the Leeds Bioimaging Facility (to S. P.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: PLA2, phospholipase A2; AA, arachidonic acid; AACOCF3, arachidonyl trifluoromethyl ketone; cPLA2α, cytosolic phospholipase A2α; HDMEC, human dermal microvascular endothelial cells; HUVEC, human umbilical vein endothelial cell; iPLA2, calcium-independent phospholipase A2; PCNA, proliferating cell nuclear antigen; BrdUrd, 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; siRNA, small interfering RNA; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; Wy-1, Wyeth-1; GFP, green fluorescent protein; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; LPC, l-α-lysophosphatidylcholine; PC, l-α-phosphatidylcholine; MTS, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

A. F. Odell and S. P. Herbert, unpublished observations.

References

- 1.Carmeliet, P. (2000) Nat. Med. 6 389-395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carmeliet, P. (2005) Nature 438 932-936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dennis, E. A. (1997) Trends Biochem. Sci. 22 1-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akiba, S., and Sato, T. (2004) Biol. Pharm. Bull. 27 1174-1178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nalefski, E. A., Sultzman, L. A., Martin, D. M., Kriz, R. W., Towler, P. S., Knopf, J. L., and Clark, J. D. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269 18239-18249 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Channon, J. Y., and Leslie, C. C. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265 5409-5413 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evans, J. H., Spencer, D. M., Zweifach, A., and Leslie, C. C. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 30150-30160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kramer, R. M., and Sharp, J. D. (1997) FEBS Lett. 410 49-53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evans, C. E., Billington, D., and McEvoy, F. A. (1984) Prostaglandins Leukot. Med. 14 255-266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whatley, R. E., Satoh, K., Zimmerman, G. A., McIntyre, T. M., and Prescott, S. M. (1994) J. Clin. Investig. 94 1889-1900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herbert, S. P., Ponnambalam, S., and Walker, J. H. (2005) Mol. Biol. Cell 16 3800-3809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herbert, S. P., Odell, A. F., Ponnambalam, S., and Walker, J. H. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 34468-34478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang, X. H., Zhao, C., and Ma, Z. A. (2007) J. Cell Sci. 120 4134-4143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang, X. H., Zhao, C., Seleznev, K., Song, K., Manfredi, J. J., and Ma, Z. A. (2006) J. Cell Sci. 119 1005-1015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herbert, S. P., and Walker, J. H. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 35709-35716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaffe, E. A. (1984) Biology of Endothelial Cells, pp. 1-13, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, Boston

- 17.Howell, G. J., Herbert, S. P., Smith, J. M., Mittar, S., Ewan, L. C., Mohammed, M., Hunter, A. R., Simpson, N., Turner, A. J., Zachary, I., Walker, J. H., and Ponnambalam, S. (2004) Mol. Membr. Biol. 21 413-421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laemmli, U. K. (1970) Nature 227 680-685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Towbin, H., Staehelin, T., and Gordon, J. (1979) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 76 4350-4354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghomashchi, F., Stewart, A., Hefner, Y., Ramanadham, S., Turk, J., Leslie, C. C., and Gelb, M. H. (2001) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1513 160-166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ni, Z., Okeley, N. M., Smart, B. P., and Gelb, M. H. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 16245-16255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ackermann, E. J., Conde-Frieboes, K., and Dennis, E. A. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270 445-450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Staton, C. A., Stribbling, S. M., Tazzyman, S., Hughes, R., Brown, N. J., and Lewis, C. F. (2004) Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 85 233-248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gerdes, J., Lemke, H., Baisch, H., Wacker, H. H., Schwab, U., and Stein, H. (1984) J. Immunol. 133 1710-1715 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schluter, C., Duchrow, M., Wohlenberg, C., Becker, M. H., Key, G., Flad, H. D., and Gerdes, J. (1993) J. Cell Biol. 123 513-522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown, D. C., and Gatter, K. C. (2002) Histopathology 40 2-11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takahashi, T., and Caviness, V. S. (1993) J. Neurocytol. 22 1096-1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paunesku, T., Mittal, S., Protic, M., Oryhon, J., Korolev, S. V., Joachimiak, A., and Woloschak, G. E. (2001) Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 77 1007-1021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coverley, D., Laman, H., and Laskey, R. A. (2002) Nat. Cell Biol. 4 523-528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Girard, F., Strausfeld, U., Fernandez, A., and Lamb, N. J. (1991) Cell 67 1169-1179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ezan, J., Leroux, L., Barandon, L., Dufourcq, P., Jaspard, B., Moreau, C., Allieres, C., Daret, D., Couffinhal, T., and Duplaa, C. (2004) Cardiovasc. Res. 63 731-738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dormond, O., Lejeune, F. J., and Ruegg, C. (2002) Anticancer Res. 22 3159-3163 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sauane, M., Correa, L., Rogers, F., Krasnapolski, M., Barraclough, R., Rudland, P. S., and Jiménez de Asúa, L. (2000) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 270 11-16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Rossum, G. S. A. T., Bijvelt, J. J. M., van den Bosch, H., Verkleij, A. J., and Boonstra, J. (2002) Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 59 181-188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shappell, S., Gupta, R. A., Manning, S., Whitehead, R., Boeglin, W. E., Schneider, C., Case, T., Price, J., Jack, G. S., Wheeler, T. M., Matusik, R. J., Brash, A. R., and Dubois, R. N. (2001) Cancer Res. 61 497-503 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boonstra, J., and van Rossum, G. S. A. T. (2003) Prog. Cell Cycle Res. 5 181-190 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mariggio, S., Sebastia, J., Filippi, B. M., Iurisci, C., Volonte, C., Amadio, S., De Falco, V., Santoro, M., and Corda, D. (2006) FASEB J. 20 2567-2569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jiang, Y. J., Lu, B., Choy, P. C., and Hatch, G. M. (2003) Mol. Cell. Biochem. 246 31-38 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murakami, M., Nakatani, Y., Kuwata, H., and Kudo, I. (2000) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1488 159-166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scott, K. F., Bryant, K. J., and Bidgood, M. J. (1999) J. Leukocyte Biol. 66 535-541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tian, W., Wijewickrama, G. T., Kim, J. H., Das, S., Tun, M. P., Gokhale, N., Jung, J. W., Kim, K. P., and Cho, W. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283 3960-3971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carmeliet, P., and Jain, R. P. (2000) Nature 407 249-257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brem, H., Gresser, I., Grosfeld, J., and Folkman, J. (1993) J. Pediatr. Surg. 28 1253-1257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Folkman, J., and Shing, Y. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267 10931-10934 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferrara, N., and Kerbal, R. S. (2005) Nature 438 967-974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yazlovitskaya, E. M., Linkous, A. G., Thotala, D. K., Cuneo, K. C., and Hallahan, D. E. (2008) Cell Death Differ. 15 1641-1653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jackowski, S. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271 20219-20222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jackowski, S. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269 3858-3867 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jackowski, S., Wang, J., and Baburina, I. (2000) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1483 301-315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baburina, I., and Jackowski, S. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274 9400-9408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]