Abstract

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) and urothelial carcinoma of the upper urinary tract are not uncommon urological malignancies. Their simultaneous occurrence in a patient is, however, extraordinarily rare. We report the case of a patient who underwent laparoscopic nephrectomy for suspected RCC. Preoperative imaging was suspicious for renal pelvic involvement, which was confirmed upon bivalving the fresh specimen at the time of surgery, with the discovery of a separate urothelium-based lesion. We discuss this rare occurrence and our management approach.

Résumé

Individuellement, l’hypernéphrome et le carcinome urothélial des voies urinaires supérieures ne sont pas des tumeurs urologiques rares. Leur survenue simultanée chez un même patient est cependant extrêmement rare. La reconnaissance préopératoire ou intra-opératoire est cruciale afin que soit effectuée la résection urétérale requise. Nous décrivons un cas d’hypernéphrome et de carcinome urothélial simultanés et homolatéraux.

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) and urothelial carcinoma (UC) of the upper urinary tract are not uncommon urological malignancies, taken individually. Their simultaneous occurrence in a patient is, however, extraordinarily rare. Pre-or intraoperative recognition is important so that ureteral resection is peformed. We report a case of synchronous RCC and UC of the ipsilateral renal unit.

Case report

The patient, an 85-year-old woman, presented to the emergency department with right-sided abdominal pain and new-onset gross hematuria. Her medical history included hypertension, hysterectomy for benign disease, and osteoporosis, with no history of smoking or chemical exposure. She was hemodynamically stable and did not require bladder irrigation. Ultrasonography suggested a right renal mass.

Subsequent investigations included urine cytology, which was atypical but not diagnostic for malignancy, normal cystoscopy and normal blood work, including liver studies and calcium. A computed tomography (CT) scan confirmed the presence of a 5.5-cm solid mass on the anterior aspect of the upper pole of the right kidney (Fig. 1). Renal vein, lymph nodes and contralateral kidney were normal. Delayed views of the collecting system were suspicious for protrusion or extension of the mass into the renal pelvis (Fig. 2). The working diagnosis based on imaging studies was RCC with invasion into the collecting system.

Fig. 1.

Computed tomography scan showing a 5.5-cm solid mass on the anterior aspect of the upper pole of the right kidney (asterisk).

Fig. 2.

Computed tomography scan with delayed pyelogram view, concerning for protrusion or extension of the mass into the renal pelvis (asterisk).

The patient was eager for definitive management of her renal mass, and so was scheduled for laparoscopic right radical nephrectomy, which was performed uneventfully. Titanium clips were placed on the distal ureter in close approximation before cutting, and there was no spillage of urine. The operating surgeon accompanied the gross specimen to the pathology department and requested that it be bivalved immediately, based on the atypical cytology and the suggestion of possible renal pelvic extension of the mass.

Upon opening the kidney, it was clear that there were 2 geographically and morphologically distinct masses in the kidney: a 5.5-cm mass corresponding clearly to the radiographic lesion, and a 2.5-cm papillary mass in the superior aspect of the renal pelvis (Fig. 3). Intraoperative frozen section of the papillary mass confirmed a UC of the renal pelvis. The surgical team was alerted, and the patient’s Pfannenstiel incision was extended to allow a right ureterectomy to be performed.

Fig. 3.

Radical nephrectomy specimen demonstrating synchronous pelvic urothelial carcinoma (long arrow) and renal cell carcinoma (arrowheads).

Final pathology confirmed the presence of 2 distinct malignancies. A cortical RCC of primarily clear cell histology was present, with Fuhrman nuclear grade 3 of 4, and no invasion of the renal capsule (Fig. 4). There was, however, microscopic invasion of a medium-sized renal vein. The second tumour was a high-grade UC with invasion through the muscularis propria of the renal pelvis and extension into renal sinus fat (Fig. 5). Surgical margins and the right ureter were negative for malignancy.

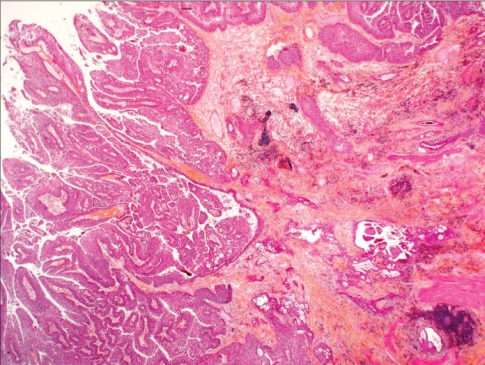

Fig. 4.

Invasive, high-grade, papillary urothelial carcinoma of the renal pelvis (hematoxylin–phloxine–saffron stain, original magnification × 40).

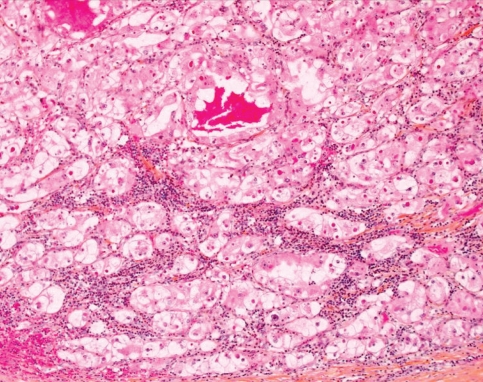

Fig. 5.

Photomicrograph of renal cell carcinoma, combined clear cell/chromophobe type (hematoxylin–phloxine–saffron stain, original magnification × 200).

Discussion

Renal cell carcinoma represents 3% of adult cancers, with 20% invading the collecting system or capsule.1 Ten percent of renal tumours arise in the renal pelvis, of which 90% are UC.2 The documented occurrence of both of these types of tumours in the same kidney is extremely rare, with the literature limited to a few small series and case reports. In the English-language literature, the first report was by Graves and Templeton in 1921 and the most recent by Demir and colleagues in 2004.3–5 A Spanish-language review and case series reported 47 described cases, and suggested no worse prognosis associated with this dual pathology.6 The authors’ review suggested that there were no readily identifiable risk factors for the simultaneous occurrence of both tumours, although 24% of the patients were smokers. Ninety percent of patients presented with hematuria, 19% with flank pain and 14% with a palpable flank mass. Twenty-four percent of patients in this review had evidence of metastatic disease at presentation (in their case report, the patient presented with intracranial metastatic disease 3 months after nephroureterectomy).

The prognosis for a patient with dual malignancies is likely most influenced by the more aggressive of the 2 tumours. Our patient’s RCC was pathologically a pT1b lesion with no evidence of metastatic disease. This was tempered by the finding of microscopic vein involvement, which has been found to be an independent negative prognostic factor for metastasis and survival at 148 months.7 Our patient’s UC was pathologically high grade and a pT3 lesion, with involvement of renal sinus fat via invasion through muscle. A renal pelvic location has improved survival in UC versus a ureteral primary,8,9 though Holmang and Johansson10 have suggested only 25% survival in high-grade pT3 upper tract UC. The UC was likely the more ominous primary lesion in this patient.

With hindsight as our guide, the area corresponding to the renal pelvic UC was still only moderately suspicious on imaging, with the main finding being the 5.5-cm renal cortical lesion. Hematuria is one of the classic findings of RCC but is usually a late symptom. Although ureteroscopy and ureteral washings would have likely found this lesion, they were declined by the patient in favour of expedited treatment. The treating physician agreed with this course of action as the CT scan was definitely more suspicious for RCC.

The patient had an uneventful in-hospital course, and was well at her first follow-up clinic visit after surgery. Further follow-up will combine aspects of recommended follow-up for both RCC and UC, as per published guidelines.11 The lessons learned in this case are to be aware of the possibility of synchronous renal tumours, as they do rarely occur, and to request intraoperative pathology consultation in the setting of nephrectomy for unusual renal lesions. In medicine, usually one explanation suffices, in this case putatively RCC with invasion into the renal pelvis. This diagnosis might have explained the hematuria, atypical cytology and large mass consistent with RCC on CT scan. In this case, 2 cancers presented together in a typical manner, but their simultaneous presence was definitely unexpected.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Novick AC, Campbell SC.Campbell M, Retik AB, Vaughan ED.Renal tumors Campbell’s urology8th edPhiladelphia: Saunders; 20022672–731. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Messing EM. Urothelial tumors of the urinary tract. In: Campbell M, Retik AB, Vaughan ED, editors. Campbell’s urology. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2002. pp. 2732–84. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graves RC, Templeton ER. Combined tumors of the kidney. J Urol. 1921;5:517–37. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Demir A, Onol FF, Bozkurt S, et al. Synchronous ipsilateral conventional renal cell and transitional cell carcinoma. Int Urol Nephrol. 2004;36:499–502. doi: 10.1007/s11255-004-0855-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee JW, Kim MJ, Song JH, et al. Ipsilateral synchronous renal cell carcinoma and transitional cell carcinoma. J Korean Med Sci. 1994;9:466–70. doi: 10.3346/jkms.1994.9.6.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernandez Arjona M, Santos Arrontes D, De Castro Barbosa F, et al. [Synchronous renal clear-cell carcinoma and ipsilateral transitional-cell carcinoma: case report and bibliographic review] [article in Spanish] Arch Esp Urol. 2005;58:460–3. doi: 10.4321/s0004-06142005000500014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lang H, Lindner V, Letourneux H, et al. Prognostic value of microscopic venous invasion in renal cell carcinoma: long-term follow-up. Eur Urol. 2004;46:331–5. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2004.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guinan P, Vogelzang NJ, Randazzo R, et al. Renal pelvic cancer: a review of 611 patients treated in Illinois 1975–1985. Urology. 1992;40:393–9. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(92)90450-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park S, Hong B, Kim CS, et al. The impact of tumor location on prognosis of transitional cell carcinoma of the upper urinary tract. J Urol. 2004;171:621–5. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000107767.56680.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holmang S, Johansson SL. Urothelial carcinoma of the upper urinary tract: comparison between the WHO/ISUP 1998 consensus classification and WHO 1999 classification system. Urology. 2005;66:274–8. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Fort Washington (PA): The Network; 2008. [(accessed 2008 Dec 11)]. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology, Bladder Cancer, Including Upper Tract Tumors and Urothelial Carcinoma of the Prostate, v.1.2006. Available: www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/bladder.pdf. [Google Scholar]