Abstract

The sleep-aids, zolpidem and eszopiclone, exert their effects by binding to and modulating GABAA receptors (GABAARs), but little is known about the structural requirements for their actions. We made 24 cysteine mutations in the benzodiazepine (BZD) binding site of α1β2γ2 GABAARs, and measured zolpidem, eszopiclone, and BZD-site antagonist binding. Mutations in γ2Loop D and α1Loops A and B altered the affinity of all ligands tested, indicating that these loops are important for BZD pocket structural integrity. In contrast, γ2Loop E and α1Loop C mutations differentially affected ligand affinity, suggesting that these loops are important for ligand selectivity. In agreement with our mutagenesis data, eszopiclone docking yielded a single model stabilized by several hydrogen bonds. Zolpidem docking yielded three equally populated orientations with few polar interactions, suggesting that unlike eszopiclone, zolpidem relies more on shape recognition of the binding pocket than on specific residue interactions and may explain why zolpidem is highly α1- and γ2-subunit selective.

Introduction

Insomnia is associated with increased morbidity and mortality resulting from accidents, cardiovascular disease, and psychiatric disorders.1 Approximately 10% of the population suffers from insomnia,2 with an estimated 2.5% using medications to aid sleep each year.1 Past pharmacological treatments have included barbiturates and benzodiazepines (BZDs), both of which promote sleep by binding to and allosterically modulating GABAA receptors (GABAARs) in the CNS. These drugs however, have several unwanted side effects including alteration of sleep architecture, nightmares, agitation, confusion, lethargy, withdrawal, and a risk of dependence and abuse.3 The newest generation of sleep-aid drugs, the non-BZD hypnotics, were developed to overcome some of these disadvantages. These drugs, which include zolpidem (ZPM) and eszopiclone (ESZ) (Figure 1), act through a similar neural mechanism as classical BZDs in that they bind to the same site in the GABAAR, but differ significantly in their chemical structures and neuropharmacological profiles. Unlike classical BZDs, the non-BZDs have minimal impact on cognitive function and psychomotor performance while facilitating more restorative sleep stages, thus inducing a pattern and quality of sleep similar to that of natural sleep.4, 5 Moreover, patients taking non-BZDs are less likely to exhibit tolerance, physical dependence, or withdrawal.4-7

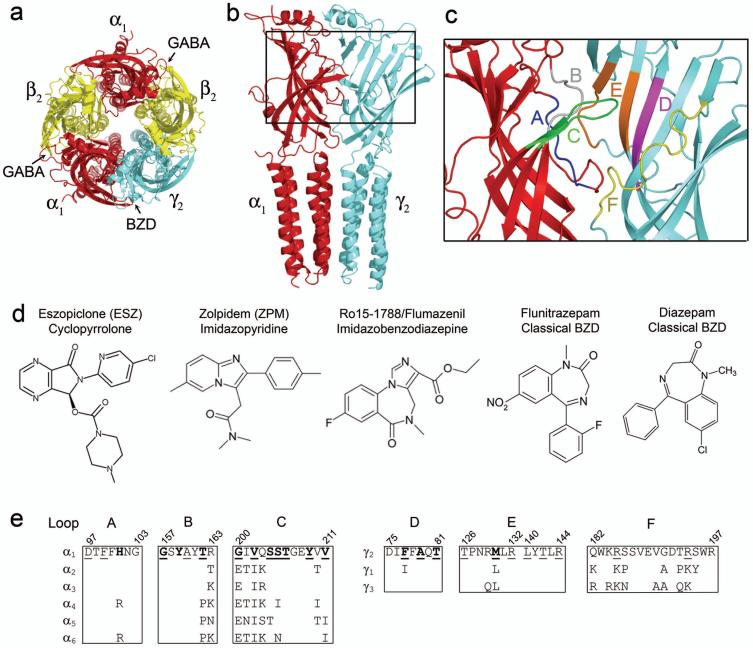

Figure 1. The GABAA receptor α1/γ2 interface and structures of benzodiazepine binding site ligands.

(a) Homology model of the α1β2γ2 GABAA receptor pentamer 36 as seen from the extracellular membrane surface. The α1, β2, and γ2 subunits are highlighted in red, yellow, and blue, respectively. Arrows indicate that GABA binds at the β2/α1 interfaces whereas benzodiazepines (BZDs) bind at the α1/γ2 interface of the receptor. (b) Side view of the α1 (red) and γ2 (blue) subunits. The region of the interface encompassing the BZD binding site is boxed and highlighted in (c), where BZD binding site Loops A-F are individually color-coded. (d) Structures of the BZD binding site ligands eszopiclone, zolpidem, Ro15-1788, flunitrazepam, and diazepam. (e) Rat GABAAR sequence alignment of Loops A, B, and C of α1-6 subunits and Loops D, E, and F of γ1-3 subunits, where only differences from α1 and γ2 are shown. Amino acid residues shown previously to be important for BZD binding are bold, residues examined in this study are underlined.

Unlike classical BZDs, the sedative/hypnotic effect of ZPM occurs at much lower doses than the other pharmacological effects attributed to BZD-site action such as muscle relaxation and anti-convulsant activity.7 This likely results from its selective binding to a specific GABAAR subtype. The GABAAR is a pentameric ligand-gated ion channel that can be formed by several different subunits (e.g. α, β, γ, etc.) and subunit isoforms (e.g. α1, α2, α3, etc.). Receptors composed of different subunits have different kinetics, cellular distributions, and pharmacological profiles. Classical BZDs bind equally well to GABAARs containing all of the α subunit isoforms except α4 and α6.8, 9 In contrast, ZPM has high affinity for receptors containing the α1 subunit, low affinity for α2- and α3-containing receptors, and no significant affinity for α5-containing receptors (Table 1).8-10 The sedative actions of BZDs have been shown to be mediated by α1-containing GABAARs, whereas BZD effects such as anxiolysis, are mediated by other α subunit isoforms.11 This helps explain why ZPM is useful as a sedative/hypnotic but is not a clinically efficacious anxiolytic, whereas classical BZDs such as diazepam are effective at treating anxiety but their use is accompanied by a myriad of adverse side effects. Interestingly, the non-BZD ESZ (and its racemate zopiclone) has similar affinity for GABA Rs containing α1, α2, α3, and α5 subunits (Table 1),10, 12 yet when taken for extended periods does not induce the adverse side effects associated with classical BZD treatment.6 Thus, the neuropharmacological properties of ESZ must stem from more than just α-subunit selectivity.

Table 1. Binding affinities of Ro15-1788, Ro15-4513, eszopiclone and zolpidem for αxβ2γ2 receptors.

Kivalues were determined by displacement of [3H] ethyl 8-fluoro-5,6-dihydro-5-methyl-6-oxo-4H-imidazo[1,5-a][1,4]benzodiazepine-3-carboxylate (Ro15-1788)52 binding (for α1, α2, α3, and α5) or [3H] ethyl-8-azido-5,6-dihydro-5-methyl-6-oxo-4H-imidazo-1,4-benzodiazepine-3-carboxylate (Ro15-4513)53 binding (for α4 and α6) and represent the equilibrium dissociation constant (apparent affinity) of the unlabeled ligand. Data represent mean +/- SD from at least 3 separate experiments; N.D.= not determined

| Receptor | Ro15-1788 Ki (nM) | Eszopiclone Ki (nM) | Zolpidem Ki (nM) | Ro15-4513 Ki (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α1 | 3.3 ± 1.3 | 50.1 ± 10.1 | 61.9 ± 7.3 | N.D. |

| α2 | 5.7 ± 0.1 | 114 ± 40.8 | 408 ± 35 | N.D. |

| α3 | 8.1 ± 0.1 | 162 ± 29.5 | 975 ± 132 | N.D. |

| α5 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 102 ± 17.9 | >15000 | N.D. |

| α4 | N.D. | >15000 | >15000 | 3.1 ± 0.1 |

| α6 | N.D. | >15000 | >15000 | 5.1 ± 0.1 |

The BZD binding site is located on the extracellular surface of the GABAAR at the interface of the α and γ subunits and is formed by residues located in at least six noncontiguous regions (historically designated Loops A-F) (Figure 1).13 Although several studies have made significant strides in uncovering the specific amino acid residues that contribute to the binding of classical BZDs (e.g. flunitrazepam and diazepam; (Figure 1)),13 complete descriptions of the residues that preferentially contribute to the binding of non-BZD ligands and the orientation of these ligands within the BZD site are relatively unknown.

In this study, we used site-directed mutagenesis, radioligand binding, and molecular docking to compare the structural requirements for ZPM and ESZ binding to α1-containing GABAARs. We found that residues in γ2Loop D, and α1Loops A and B are important for maintaining the overall structural integrity of the binding pocket whereas residues in γ2Loop E and α1Loop C are important for ligand selectivity. Molecular docking is in good agreement with the binding data and suggests that unlike ESZ, ZPM binding relies more on the overall shape of the binding pocket than on specific residue interactions within the BZD site.

Results

Effects of BZD-site mutations on [3H] Ro15-1788 binding affinity

Several residues that contribute to the binding of BZD ligands have previously been identified (Figure 1e). On the α subunit these residues include: H101 (Loop A),8, 14-19 G157, Y159, T162 (Loop B),8, 15, 20, 21 and G200, V202, S204, S205, T206, Y209, and V211 (Loop C);8, 15, 20-28 on the γ subunit these include: F77, A79, T81 (Loop D)16, 22, 29-33 and M130 (Loop E).22, 34

To help elucidate the unique structural requirements for ESZ and ZPM binding, 24 single cysteine mutations (12 each in the α1 and γ2 subunits) were made in or near the BZD binding site in the GABAAR (Figure 1e). These included all of the sites mentioned above with the exception of two residues and some new sites. We did not mutate α1H101, as it has already been shown to contribute to the high affinity binding of both zopiclone and ZPM,8, 14, 17 and α1Y159, because serine and cysteine substitutions at this site abolish [3H] Ro15-1788 and [3H] flunitrazepam binding thereby precluding further BZD affinity measurements.15, 20

The mutant subunits were co-expressed with wild-type (WT) subunits in HEK293T cells to form α1β2γ2 GABAARs and the binding of the BZD-site antagonist, [3H] Ro15-1788 (Figure 1d) was measured. The majority of mutant receptors bound Ro15-1788 with similar affinity as WT receptors (Ki = 3.3 ± 1.3 nM) (Table 2). Seven mutations caused small but significant decreases (2.0 - 4.5 fold) in Ro15-1788 affinity, whereas one mutation, α1G157C, increased the affinity over 17-fold (Table 2). For three mutant receptors (α1β2γ2F77C, α1D97Cβ2γ2, and α1Y209Cβ2γ2) specific binding of [3H] Ro15-1788 or the BZD-site agonist [3H] flunitrazepam (Figure 1d) was not measurable (data not shown), precluding any further examination.

Table 2. Binding affinities of Ro15-1788, eszopiclone and zolpidem for WT and mutant α1β2γ2 receptors.

Ki values were determined by displacement of [3H] Ro15-1788 binding and represent the equilibrium dissociation constant (apparent affinity) of the unlabeled ligand. The loop where each mutation is located inside the BZD binding pocket is indicated. The ratio of mutant to WT binding is shown and was calculated by dividing the Ki value for the mutant by the Ki value for WT. Data represent mean +/- SD from at least three separate experiments; N.B.= no binding detected; N.D.=not determined. Values significantly different from WT are indicated

| Ro15-1788 |

Eszopiclone |

Zolpidem |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loop | Receptor | Ki (nM) | mut/wt | Ki (nM) | mut/wt | Ki (nM) | mut/wt |

| WT | 3.3 ± 1.3 | 1.0 | 50.1 ± 10.1 | 1.0 | 61.9 ± 7.3 | 1.0 | |

| αβγD56C | 3.1 ± 0.2 | 0.9 | 82.4 ± 16.1 | 1.6 | 67.6 ± 8.0 | 1.1 | |

| D | αβγF77C | N.B. | N.D. | N.D. | |||

| D | αβγA79C | 9.2 ± 1.6 * | 2.8 | 393 ± 23.3 ** | 7.9 | 577 ± 64.7 ** | 9.3 |

| D | αβγT81C | 4.4 ± 1.4 | 1.3 | 75.2 ± 11.6 | 1.5 | 108 ± 9.2 * | 1.7 |

| E | αβγT126C | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 1.3 | 71.9 ± 3.5 | 1.4 | 72.7 ± 19.2 | 1.2 |

| E | αβγM130C | 13.8 ± 4.7 * | 4.1 | 102 ± 18.4 * | 2.0 | 15.5 ± 3.7 ** | 0.3 |

| E | αβγR132C | 13.0 ± 4.7 * | 3.9 | 110 ± 23.7 * | 2.2 | 35.8 ± 4.8 * | 0.6 |

| E | αβγL140C | 3.8 ± 0.1 | 1.2 | 46.3 ± 1.4 | 0.9 | 63.1 ± 1.9 | 1.0 |

| E | αβγT142C | 9.2 ± 2.0 * | 2.8 | 503 ± 89.1 ** | 10 | 1321 ± 300 ** | 21 |

| E | αβγR144C | 3.7 ± 1.1 | 1.1 | 174 ± 50.6 ** | 3.5 | 38.0 ± 11.5 | 0.6 |

| F | αβχ161 | 9.6 ± 1.5 * | 2.9 | 22.4 ± 2.6 * | 0.4 | 427 ± 44.8 ** | 6.9 |

| F | αβγR185C | 3.3 ± 0.0 | 1.0 | 70.9 ± 3.5 | 1.4 | 67.4 ± 6.8 | 1.1 |

| F | αβγR194C | 4.1 ± 0.0 | 1.2 | 67.0 ± 4.6 | 1.3 | 62.6 ± 0.7 | 1.0 |

| A | αD97Cβγ | N.B. | N.D. | N.D. | |||

| A | αF99Cβγ | 15.0 ± 0.8 ** | 4.5 | 407 ± 123 ** | 8.1 | 180 ± 35.6 * | 2.9 |

| B | αG157Cβγ | 0.19 ± 0.06 ** | 0.06 | 2103 ± 400 ** | 42 | 1252 ± 367 ** | 20 |

| B | αA160Cβγ | 4.0 ± 0.6 | 1.2 | 60.4 ± 32.2 | 1.2 | 81.4 ± 10.7 | 1.3 |

| B | αT162Cβγ | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 0.7 | 33.8 ± 5.6 | 0.7 | 109 ± 30.4 | 1.8 |

| C | αG200Cβγ | 3.0 ± 0.3 | 0.9 | 119 ± 13.8 ** | 2.4 | 598 ± 104 ** | 9.7 |

| C | αV202Cβγ | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 0.4 | 249 ± 52.9 ** | 5.0 | 556 ± 153 ** | 9.0 |

| C | αS204Cβγ | 8.8 ± 0.6 ** | 2.7 | 57.9 ± 1.6 | 1.2 | 433 ± 56.4 ** | 7.0 |

| C | αS205Cβγ | 6.5 ± 1.0 * | 2.0 | 34.9 ± 1.1 | 0.7 | 41.2 ± 7.6 | 0.7 |

| C | αT206Cβγ | 2.1 ± 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.83 ± 0.23 ** | 0.02 | 76.4 ± 23.2 | 1.2 |

| C | αY209Cβγ | N.B. | N.D. | N.D. | |||

| C | αV211Cβγ | 4.1 ± 1.4 | 1.2 | 62.4 ± 4.4 | 1.2 | 67.8 ± 22.2 | 1.1 |

p<0.05

p<0.01

Effects of γ2 subunit mutations on ESZ and ZPM binding affinity

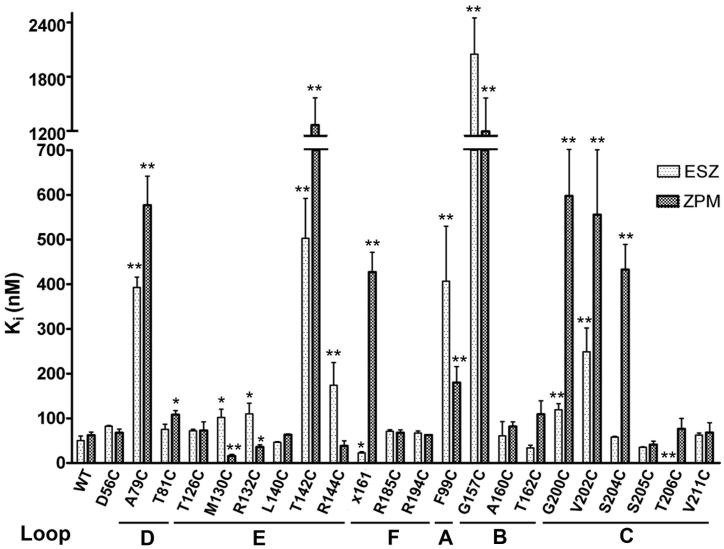

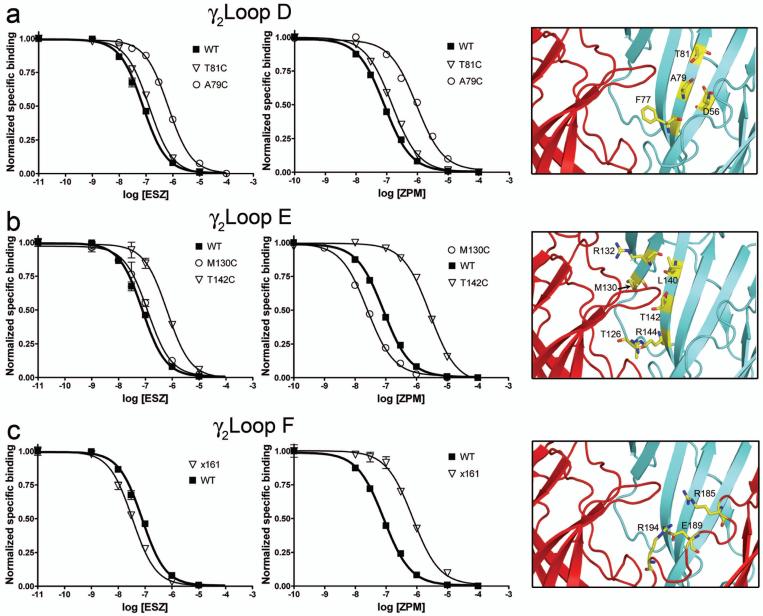

ESZ and ZPM binding affinities were determined by their ability to competitively displace [3H] Ro15-1788. In the γ2 subunit, one mutation in Loop D (β-strand 2), A79C, significantly reduced both ESZ and ZPM affinity (∼8-9 fold) compared to WT receptors (Ki ESZ = 50.1 ± 10.1 nM; Ki ZPM = 61.9 ± 7.3 nM), whereas γ2T81C located adjacent to γ2A79, had a small but significant effect on ZPM but not ESZ binding (Figures 2,3a; Table 2). γ2D56C on the neighboring β-strand (Figure 3a) had no effect on the binding of either drug (Figure 2; Table 2).

Figure 2. Cysteine mutations in the benzodiazepine binding site differentially affect eszopiclone and zolpidem affinity for the GABAA receptor.

The apparent affinity (Ki) of WT, γ2-mutant (Loops D-F) and α1-mutant (Loops A-C) receptors for ESZ (light bars) and ZPM (dark bars) is graphed and was measured as described in the Methods. x161 is the γ/α chimera where residues N-terminal to 161 are γ2 sequence and residues C-terminal to 161 are α1 sequence. Bars represent mean ± SD of at least three independent experiments. Values significantly different from WT are indicated (*p<0.05; **p<0.01).

Figure 3. Mutations in the γ2 subunit differentially affect eszopiclone and zolpidem binding to the GABAA receptor.

(a-c) Representative radioligand binding curves depict the displacement of [3H] Ro15-1788 binding by ESZ (left panels) and ZPM (middle panels) for WT α1β2γ2 receptors (filled squares) and the indicated γ2 mutant receptors (open symbols) in Loop D (a), Loop E (b), and Loop F (c), respectively. Representative binding curves are shown for a selected group of mutants. Each data point is the mean ± SEM of triplicate measurements. Data were fit by nonlinear regression as described in the Methods and Ki values are reported in Table 2. A close-up view of the benzodiazepine binding site (right panels), with the α1 subunit in red and the γ2 subunit in blue, highlights all sites where individual cysteine substitutions were introduced (yellow). For x161, residues 1-161 are γ2 sequence (blue), and residues C-terminal to 161 are α1 sequence (red). The localization of residues γ2R185, γ2E189, and γ2R194 is based on their position in the WT γ2 sequence.

γ2Loop E of the BZD binding site is composed of two adjacent β-strands (5/6) that form the back and side of the BZD binding pocket (Figure 1c). Several mutations in the middle of these β-strands differentially affected ESZ and ZPM binding (Figures 2,3b; Table 2). Whereas cysteine substitution of γ2M130 and γ2R132 each decreased ESZ affinity ∼2-fold, these mutations increased ZPM affinity ∼2-4 fold. While γ2T142C significantly reduced the affinity of both ligands, it had a larger effect on ZPM binding compared to ESZ (21-fold vs. 10-fold change). Moreover, α1β2γ2R144C receptors showed a significant reduction in ESZ affinity (3.5-fold) but no change in ZPM binding. γ2T126C and γ2L140C, located at the periphery of the BZD-site (Figure 3b) did not affect the binding of ESZ or ZPM. Overall, the data suggest that Loop E plays an important role in determining ligand selectivity of the BZD binding site.

Loop F of the γ2 subunit (∼residues 182-197) is a dynamic region of the receptor located between the BZD binding site and the transmembrane channel domain (Figure 1). Through the use of γ2/α1 chimeras, a portion of Loop F (γ2186-192) was shown to be important for high affinity ZPM binding.35 A chimeric subunit, χ161 (containing γ2 residues up to and including amino acid 161 and α1 residues C-terminal to 161), when expressed with WT α1 and β2 subunits retained WT binding affinity for flunitrazepam, but the binding affinity for ZPM decreased 8-fold. Here, we used the same chimera to test whether residues C-terminal to 161 were also important for ESZ binding. We found that χ161 slightly increased (∼2-fold) the affinity of the receptor for ESZ (Figures 2,3c; Table 2).

We noticed that in our homology model of the GABAAR36 two arginine residues and a glutamate from Loop F (γ2R185, γ2R194, and γ2E189) point toward the ligand binding pocket (Figure 3c). We individually mutated the arginine residues to cysteine and found the binding of Ro15-1788, ESZ, and ZPM to γ2R185C- and γ2R194C-containing receptors was indistinguishable from WT (Figure 2; Table 2). These data are consistent with our previous study of γ2Loop F where we demonstrated mutations in this region (γ2W183C, γ2E189C, and γ2R197C) affect modulation of GABA current by BZD agonists without affecting binding affinity of various BZD ligands including ZPM, Ro15-1788, the classical BZD, flurazepam, and the inverse agonist, DMCM.37 Overall, these results strongly suggest no one residue in γ2Loop F is critical for binding classical or non-BZDs.

Effects of α1 subunit mutations on ESZ and ZPM binding affinity

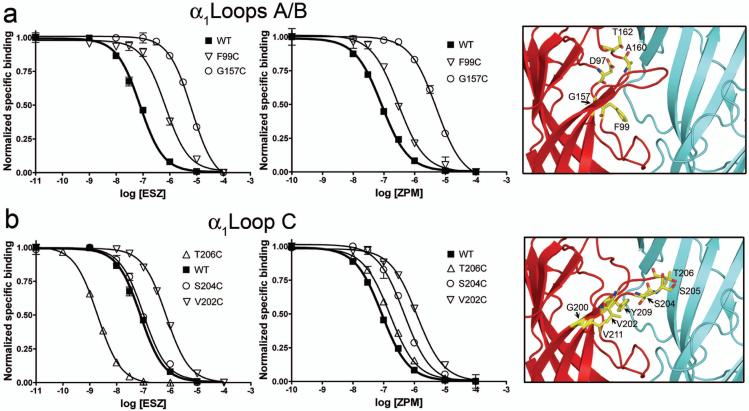

In α1 Loops A and B, cysteine substitution of two residues, α1A160 and α1T162, had no significant effect on either ESZ or ZPM binding affinity (Figure 2; Table 2). In contrast, cysteine substitution of α1F99 and α1G157, caused significant changes in the affinity of both ligands. α1F99C reduced ESZ and ZPM affinity by ∼8- and 3-fold, respectively, compared to WT receptors. α1G157C had a larger effect, with 42- and 20-fold changes in ESZ and ZPM binding affinity, respectively (Figures 2, 4a; Table 2).

Figure 4. Mutations in the α1 subunit differentially affect eszopiclone and zolpidem binding to the GABAA receptor.

(a-b) Representative radioligand binding curves depict the displacement of [3H] Ro15-1788 binding by ESZ (left panels) and ZPM (middle panels) for WT α1β2γ2 receptors (filled squares) and the indicated α1 cysteine mutant receptors (open symbols) in Loops A and B (a) and Loop C (b), respectively. Representative binding curves are shown for a selected group of mutants. Each data point is the mean ± SEM of triplicate measurements. Data were fit by nonlinear regression as described in the Methods and Ki values are reported in Table 2. A close-up view of the benzodiazepine binding site (right panels), with the α1 subunit in red and the γ2 subunit in blue, highlights all sites where individual cysteine substitutions were introduced (yellow).

Cysteine substitution of several residues in α1Loop C also significantly altered the binding affinity of both ligands. α1G200C and α1V202C reduced ESZ affinity by 2.4- and 5.0-fold, respectively, and reduced ZPM affinity 9.7- and 9.0-fold, respectively (Figures 2, 4b; Table 2). Other mutations differentially affected ZPM and ESZ affinity. α1S204C reduced ZPM affinity by 7-fold, but had no effect on ESZ binding, whereas α1T206C increased ESZ affinity over 60-fold while having no effect on ZPM binding (Figures 2, 4b; Table 2). Receptors containing α1S205C and α1V211C bound both ligands with WT affinity. These results suggest that together with γ2Loop E, α1Loop C is an important determinant for BZD-site ligand selectivity.

Molecular docking of eszopiclone and zolpidem

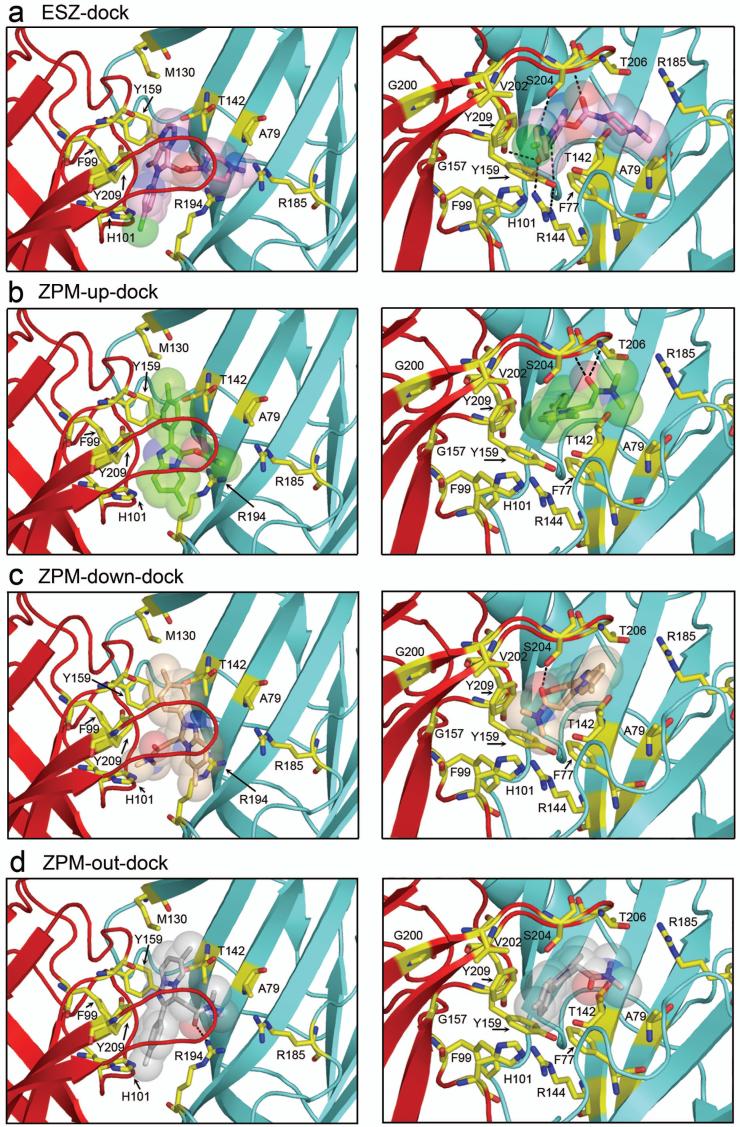

Independent of the radioligand binding experiments described above, we used our homology model of the GABAAR to dock ESZ and ZPM into the BZD binding site. ESZ docking yielded a single most populated pose with low energy (-6.61 kcal/mol). In this pose (termed ESZ-dock), the free carbonyl of ESZ is pointed up toward Loop C and the ring carbonyl is near γ2R144 (Loop E) and α1H101 (Loop A) near the base of the pocket (Figures 5a, 6a). In contrast, ZPM docking yielded three equally populated poses with similar energies (between -7.0 and -6.7 kcal/mol), one with the imidazopyridine ring under α1Loop C, the carbonyl pointed up toward the tip of α1Loop C and the dimethyl amide pointed towards γ2Loop D (ZPM-up-dock) (Figure 5b), one with the imidazopyridine ring under α1Loop C and the dimethyl amide pointed down in the pocket toward α1H101 (ZPM-down-dock) (Figures 5c, 6b), and one where the imidazopyridine ring pointed toward the back wall of the pocket, the carbonyl pointed down away from α1Loop C and the dimethyl amide positioned under the tip of α1Loop C (ZPM-out-dock) (Figure 5d).

Figure 5. Molecular docking of eszopiclone and zolpidem.

View looking down on α1Loop C (left panels) and underneath α1Loop C (right panels) of (a) ESZ and (b,c,d) ZPM docked into the benzodiazepine binding site of the GABAAR using AutoDock 4.0 software as described in the Methods. The α1 subunit is red, the γ2 subunit is blue, and residues of interest are highlighted in yellow. Docked ligands are represented as sticks with transparent space-fill. Atoms are color coded as follows: oxygen, red; nitrogen, blue; sulfur, yellow; chloride (ESZ), green. Potential hydrogen bonds are represented by dashed lines. Pdb files containing eszopiclone and zolpidem docked at the BZD site of the GABAAR are provided in the supplementary material.

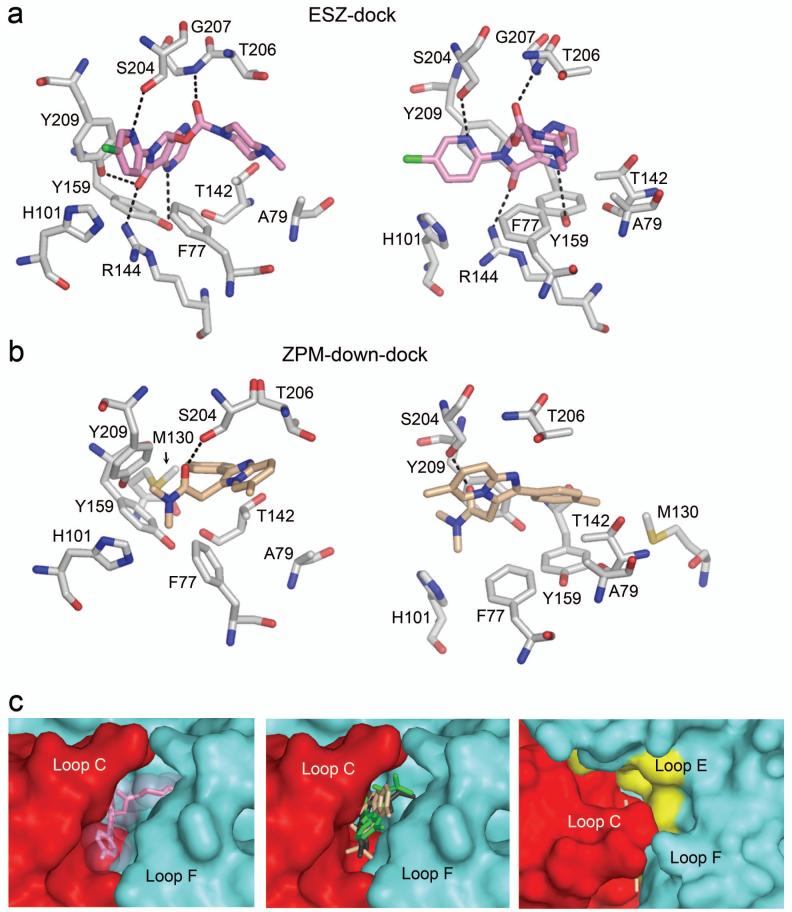

Figure 6. Eszopiclone and zolpidem in the BZD binding pocket.

Two views of ESZ-dock (a) and ZPM-down-dock (b) showing the relative orientation of ligand and residues of interest in the BZD-site. Potential hydrogen bonds are represented by dashed lines. Atoms are color coded as follows: oxygen, red; nitrogen, blue; sulfur, yellow; chloride (ESZ), green. (c) The surface of the α1 (red) and γ2 (blue) subunits near the BZD-site is shown to highlight the size of the binding pocket. Left panel: ESZ (pink) is represented as sticks with transparent space-fill. Middle panel: The three orientations of ZPM (green, tan, gray) are represented as sticks. Right panel: Surface view of ZPM-down-dock (tan, sticks) as seen looking down on α1Loop C. (Note: most of the molecule is occluded by Loop C). The surface of Loop E residues examined in this study is highlighted in yellow. Observe the large unfilled volume of space bordered by Loop E residues.

To gain insight into the potential interactions between ESZ or ZPM and the GABAAR in our docked ligand-receptor complexes, we measured the distance between atoms in each ligand and atoms in the protein, with the idea that functional groups separated by less than 7 Å have the potential to interact38 and those within 4 Å may form salt bridges or hydrogen bonds.39 In ESZ-dock, residues γ2F77, γ2A79, γ2T142, γ2R144, α1H101, α1Y159, α1T206, and α1Y209 all come within 4 Å of the ligand (Figures 5a, 6a), and when mutated alter ESZ binding (Table 2) and/or BZD binding in general. In this docking, potential polar contacts exist between ESZ and γ2R144, α1Y159, α1S204, α1Y209, and the backbone of α1Loop C (shown as dashed lines in Figures 5a, 6a). In addition, residues α1F99, α1V202, γ2M130, and γ2R132, which when mutated all adversely affect ESZ binding (Table 2), are all within 7 Å of ESZ in our model.

For ZPM, the three poses are similar in that residues including γ2F77, γ2M130, γ2T142, α1H101, α1Y159, α1S204, and α1Y209, all come within 5 Å of the ligand in each case (Figures 5, 6b). Likewise, residues α1F99, α1V202, γ2A79, and γ2R132 are within ∼7 Å or less from ZPM in each model. Thus, even though the free carbonyl of ZPM is oriented differently in each pose, the space occupied by ZPM within the binding pocket is similar. The major difference between the three models lies in the potential for hydrogen bonding. In ZPM-up-dock, potential hydrogen bonds exist between ZPM and the backbone of Loop C near α1T206/G207, in ZPM-down-dock, the free carbonyl may form a hydrogen bond with α1S204 in Loop C, and in ZPM-out-dock the carbonyl may interact with γ2R194 in Loop F (dashed lines, Figures 5, 6b).

Discussion

Although several studies have revealed important information on the amino acid side chains that contribute to classical BZD binding in the GABAAR, a complete description of the residues that participate in non-BZD binding has been lacking. Residues previously shown to participate in ZPM binding include: γ2F77, γ2M130, α1H101, α1T162, α1G200, α1S204, α1T206, α1Y209, and α1V211.8, 14, 21-25, 28, 32-34 To our knowledge, only one site, α1H101, has been identified that is important for zopiclone (the racemate of ESZ) binding.17 Here, we define receptor models for how ESZ and ZPM are oriented in the binding site, evaluate how specific residues in the binding site interact with ESZ and ZPM, and provide new insight into the pharmacophores for these drugs.

Residues in Loops A, B, and D are critical for the overall structure of the BZD site

Several lines of evidence suggest that residues in γ2Loop D and α1Loops A and B are critical to the binding of BZDs in general and thus are important for the overall structure of the BZD binding site. Mutations in these areas affect the binding affinities of a variety of structurally diverse BZD-site ligands. In γ2Loop D, we were unable to detect specific binding of BZD antagonist, [3H] Ro15-1788 or the BZD agonist [3H] flunitrazepam to F77C-containing receptors, suggesting that the native phenylalanine at this position is a key structural element in the BZD binding pocket. This is consistent with previous findings that showed a variety of substitutions at γ2F77 dramatically alter the affinity of various BZDs including Ro15-1788, diazepam, flunitrazepam, and ZPM,22, 32, 33 and where γ2F77C was shown to completely abolish flurazepam potentiation.29

Moreover, we found mutation γ2A79C reduced the binding of ESZ and ZPM to a similar extent (∼8-9-fold) (Figure 2) and the affinity of the receptor for Ro15-1788 was also significantly decreased (Table 2). Previous studies found mutation of γ2A79 was also detrimental to flunitrazepam, Ro15-4513, Ro15-1788, and diazepam binding.16, 30, 31 These results are in good agreement with cysteine accessibility studies that showed γ2A79 is part of the BZD binding pocket.29, 30

Cysteine substitution of γ2T81 had no effect on ESZ or Ro15-1788 and only a minor effect on ZPM affinity (<2-fold) (Table 2). However, larger volume BZD-site ligands such as Ro15-4513, Ro40-6129, and Ro41-3380 are affected by mutations at this site.30 Thus, even though γ2T81 may not contribute significantly to ESZ or ZPM binding, it likely forms part of the binding site for other BZDs.

In α1Loop A, we observed no specific binding of [3H] Ro15-1788 or [3H] flunitrazepam to α1D97Cβ2γ2 receptors. Functional α1D97Cβ2γ2 receptors that respond to GABA can be expressed in Xenopus oocytes.40 Thus, it is unlikely that cysteine substitution at this location impairs proper folding or expression of the receptor. Molecular docking indicates that α1D97 is within 8 Å of ESZ and ZPM. In our model, α1D97 appears part of an electrostatic network of residues that bridges the α1/γ2 subunit interface. We speculate that the lack of specific binding for this mutant is because α1D97 is important for maintaining the structural integrity of the BZD pocket.

Mutation of α1F99 in Loop A significantly reduces GABAAR affinity for ESZ, ZPM, and Ro15-1788. This may be because α1F99 participates in hydrophobic interactions with bound drug, or because mutation of α1F99 to cysteine alters the position of α1H101 (Loop A) and α1Y159 (Loop B) which lie on either side of it in the binding pocket (Figure 5). Indeed, the necessity of α1H101 in binding ZPM,8, 14 zopiclone,17 and several other BZDs16, 18, 19 has been established. The importance of α1Y159 is underscored by its potential to hydrogen bond directly with ESZ in the binding pocket (Figure 5) and the inability of [3H] Ro15-1788 or [3H] flunitrazepam to bind α1Y159C-or α1Y159S-containing receptors.15, 20

One of the most dramatic shifts in BZD binding affinity was measured for the α1Loop B mutant, G157C. This residue appears to be at the side wall of the ESZ and ZPM binding pocket (Figure 5). In our homology model of the GABAAR, a larger cysteine side chain would decrease the volume of the binding site. This may hinder occupation of the site by ZPM and ESZ and/or affect the positioning of nearby residues including α1H101 (Loop A) and α1Y209 (Loop C) (Figure 5). The fact that G157C drastically reduces ZPM and ESZ binding (Figure 2; Table 2) but increases Ro15-1788 affinity 17-fold supports the idea that G157C alters the shape of the BZD binding pocket and that imidazobenzodiazepines (i-BZDs) such as Ro15-1788, have different structural requirements than the non-BZDs. Indeed, a recent study showed that a sulfhydryl-reactive derivative of the i-BZD, Ro15-4513, was able to covalently attach to a cysteine at α1G157.15

Since mutation of residues in γ2LoopD and α1Loops A and B alter the binding affinity of a variety of structurally diverse BZD-site ligands (our work and others), we envision that these regions define the core of the binding site for BZD-site ligands. Thus, a question remains as to what defines ligand specificity at the BZD binding site.

Residues in Loops C and E determine ligand selectivity at the BZD site

Unlike residues in Loops A, B, and D, γ2Loop E residues are located at the back of the binding pocket where extra space exists for ligand placement/movement (Figure 6c, right panel). The large unfilled volume bordered by Loop E is likely ideal for accommodating ligands of different size and chemical composition. Indeed, we found mutations M130C, R132C, and R144C in γ2Loop E differentially affect ESZ, ZPM, and Ro15-1788 affinity (Table 2; Figure 2). In addition, the magnitude of the effect of the T142C mutation was different for all three ligands tested. Interestingly, previous studies have shown mutation of γ2M130 to leucine reduces ZPM affinity while having very small or no effects on the binding of several other BZDs.22, 34 Thus, substitution of native Loop E residues may cause a change in the volume of the binding site that results in altered positioning of the ligand in the pocket, thereby affecting affinity. For example, molecular docking shows the native arginine at position 144 stabilizes the ring carbonyl of ESZ in the binding pocket via a hydrogen bond (Figure 5), thus removal of this H-bond via cysteine substitution likely causes the observed reduction in ESZ affinity. In contrast, ZPM dockings show no interaction with γ2R144, explaining the lack of effect of γ2R144C on ZPM binding.

Mutations in α1Loop C also differentially affect ligand binding to the BZD-site of the GABAAR (Figure 2) suggesting that these residues also play a role in determining ligand selectivity. We found that three mutations, G200C, V202C, and S204C, had a much greater effect on ZPM affinity than ESZ or Ro15-1788, whereas T206C dramatically increased ESZ affinity without affecting ZPM or Ro15-1788 (Figure 2; Table 2). In addition, previous studies have shown mutations T206V and T206A selectively alter the affinity of diazepam, flunitrazepam, and ZPM but not that of several other BZDs.22, 25

Based on the low sequence homology of α1Loop C to other α subunit isoforms (Figure 1e), Loop C is likely a significant determinant in the α1-subunit selectivity of ZPM. This is supported by previous studies. First, replacement of α1G200 with the aligned glutamate residue present in all other α subunit isoforms reduces ZPM binding,23 whereas replacement of the glutamate in α3, α5, and α6 with glycine increases the affinity of these receptors for ZPM.8, 21, 24 Second, replacement of the threonine in α5 with the aligned serine at 204 in α1 increases the affinity of α5 for ZPM.21 Lastly, mutation of α1V211 to the aligned isoleucine in α5 and α6 decreases flunitrazepam and ZPM affinity, while increasing the affinity of α5-selective ligands.28 All of these substitutions show that α1Loop C residues promote ZPM binding whereas Loop C residues from other α subunit isoforms reduce ZPM affinity, supporting the idea that α1Loop C contributes to ZPM selectivity.

Loop C residues α1Val211, α1Val202, and α1Ser205 also appear to be especially important for i-BZD binding. A sulfhydryl-reactive derivative of Ro15-4513 has been shown to covalently attach to α1V202C and α1V211C 15, whereas α1S205C reduced the affinity for Ro15-1788 (Table 2), and replacement of α1S205 with the aligned asparagine in α6 was shown to decrease the affinity of i-BZDs and β-carbolines.27 Of the cysteine substitutions at these sites, only α1V202C had an effect on ESZ and ZPM binding (Figure 2; Table 2). Overall, mutations in γ2Loop E and α1Loop C differentially affect binding of structurally diverse classes of BZD-site ligands supporting the idea that these regions define specificity.

Zolpidem interaction with the BZD site is less specific than eszopiclone

The orientation of ESZ in the BZD binding pocket as presented in Figures 5 and 6 is supported by our mutagenesis data. This docking was the lowest energy, most highly populated pose obtained using AutoDock 4.0. A similar orientation of ESZ was observed using AutoDock 3.0 and SureFlex Dock (data not shown) and the docking is consistent with the recently described unified pharmacophore/receptor model of the BZD site.41 Essential functional groups defining the ESZ pharmacophore and its orientation in the site are its two carbonyls, which hydrogen bond with the backbone of Loop C and γ2R144 (Loop E), respectively, and two ring nitrogens, which hydrogen bond with α1S204 (Loop C) and α1Y159 (Loop B), respectively (Figure 6).

In contrast, ZPM may bind in multiple orientations in the BZD site. Our molecular docking revealed three equally populated poses with equivalent energies that occupy a similar space within the BZD site (Figures 5 and 6), but with few potential polar contacts in any orientation. Thus, the essential descriptor of the ZPM pharmacophore is likely its size and shape. ZPM has only a single carbonyl, which appears capable of interacting with several different residues in the BZD binding site (Figure 5). We found that this carbonyl could hydrogen bond with α1Loop C (at α1S204 or the backbone near α1T206/G207) or with γ2Loop F (Arg194) (Figure 5). Similar orientations were observed with Autodock 3.0 and SureFlex Dock software (data not shown). Our ZPM-up-dock pose is similar to that reported by Sancar et al, which allowed flexible movement of the side chains during docking.35 While our mutagenesis data would favor hydrogen bonding with α1S204, we cannot exclude any of the poses presented here. Overall, we believe that unlike ESZ, ZPM binding relies more on shape recognition of the binding pocket than on specific interactions in the BZD site. This would explain several observations:

First, this would account for the α1 subunit selectivity of ZPM (Table 1).8-10, 42, 43 The included volume of the BZD binding pocket for α1-containing receptors has a slightly different shape, polarity, and lipophilicity compared to α2- and α3-containing receptors,41 explaining the reduced but still measurable affinity of ZPM for α2 and α3 (Table 1). Furthermore, the included volume of α1-containing receptors is much larger than α4-, α5-, and α6-containing receptors,41 thus explaining the lack of ZPM binding at these α subtypes (Table 1). It follows that differences in the included volumes of the BZD-site for γ2- versus γ1- and γ3-containing receptors also likely play a role in ZPM selectivity.

Second, this clarifies why χ161, but not specific mutations in Loop F, specifically reduce ZPM binding (Table 2). The replacement of the entire γ2Loop F, which is poorly conserved, with the α1Loop F that is also two amino acids longer, likely changes the size of the binding pocket to the detriment of ZPM binding.

Third, shape recognition by ZPM would explain why minor mutations in Loop C like α1G200C, α1V202C, and α1S204C, affect ZPM binding to a much greater extent than ESZ (Figure 2). Loop C, which comprises the entire lid over of the BZD site (Figure 6c) is highly flexible, and is believed to move upon ligand binding.44-46 Thus, it stands to reason that mutation of α1G200, located at the hinge of Loop C (Figure 5), would change the overall flexibility of the Loop, perhaps preventing its full closure on the binding site, resulting in an altered shape of the binding pocket, which in turn precludes high affinity ZPM binding. In contrast, ESZ, which is anchored to the BZD site by multiple interactions (e.g. Arg144, Tyr209, Tyr159, etc.)(Figure 6a), is less affected by any single mutation.

Overall, this evidence suggests that ZPM binding depends largely on the size and shape of the BZD binding pocket rather than specific polar interactions.

Summary and conclusions

In summary, our data provide new insights toward defining the pharmacophore for non-BZD hypnotics as well as the structure of the BZD binding site (Figure 6). We provide a comprehensive description of the amino acid residues that contribute to the binding of these ligands and present molecular models for their orientation in the BZD binding site. We show that residues in γ2Loop D and α1Loops A and B provide the necessary framework for ligand binding in the pocket, while specific residues in γ2Loop E and α1Loop C play a key role in determining ligand selectivity. We conclude that γ2Loop F does not directly contribute to BZD binding but may serve indirectly to maintain the structural integrity of the region. We also provide evidence that the subunit selectivity of ZPM results mainly from the overall shape of the binding pocket and is based largely on its interaction with Loop C.

Thus, their footprint within the BZD binding pocket of the GABAAR may in part determine the pharmacological properties of the non-BZDs. Further experiments will be necessary to determine if specific residues in Loops C and E differentiate the efficacies of the classical and non-BZD ligands. The identification of the structural elements important for the high affinity binding and efficacy of these drugs provides insight into the unique neuropharmacological profile of ESZ and ZPM in the CNS and will be beneficial in the design and development of more pharmacologically and behaviorally selective BZD site ligands.

Experimental Section

Site-directed mutagenesis

Cysteine mutants of γ2L and α1 receptor subunits were made by recombinant PCR in the pUNIV vector47 and verified by double-stranded DNA sequencing.

Radioligand binding

HEK293T cells were grown in Minimum Essential Medium with Earle’s salts (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) containing 10% fetal bovine serum in a 37°C incubator under 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cells were plated on 100mm dishes at ∼40% confluency47 for transient transfection using a standard CaHPO4 precipitation method.48 Cells were transfected with equal ratios of α, β, and γ subunit DNA in the same vector (4 μg/subunit). For experiments involving cysteine mutants and WT α1β2γ2 receptors, cells were co-transfected with WT pUNIV-α1, pUNIV-β2, pUNIV-γ2L, or mutant subunit cDNA. For expression of α2β2γ2, α3β2γ2, and α6β2γ2 receptors, cells were co-transfected with β2-pRK5 and γ2-pRK5 and either α2-pRK5, α3-pRK5, or α6-pRK5 (constructs kindly provided by S. Dunn (Department of Pharmacology, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada)). For expression of α4β2γ2 and α5β2γ2 receptors, cells were co-transfected with α4-pUNIV, β2-pUNIV, and γ2-pUNIV or α5-pCEP4, β2-pCEP4, and γ2-pCEP4 cDNA, respectively. Cells were harvested and membrane homogenates prepared 48 hours post-transfection as described.49 Briefly, membrane homogenates (50 μg) were incubated at room temperature for 40 min with a sub-Kd concentration of radioligand ([3H] Ro15-1788, 70.7Ci/mmol; [3H] flunitrazepam, 85.2 Ci/mmol; [3H] Ro15-4513, 35.7 Ci/mmol; PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences, Boston, MA) in the absence or presence of seven different concentrations of unlabeled ligand in a final volume of 250 μL. Data were fit by non-linear regression to a one-site competition curve defined by the equation y=Bmax/[1+(x/IC50)], where y is bound [3H] ligand in disintegrations per minute, Bmax is maximal binding, x is the concentration of displacing ligand, and IC50 is the concentration of unlabeled ligand that inhibits 50% of [3H] ligand binding (Prism; GraphPad Software). Equilibrium dissociation constant values for the unlabeled ligand (Ki) were calculated using the Cheng-Prusoff/Chou equation: Ki=IC50/[1+L/Kd], where Kd is the equilibrium dissociation constant of the radioligand, and L is the concentration of the radioligand.

Statistical analysis

Binding data represent mean ± SD from three experiments performed in triplicate. The data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-test for significance of differences (StatView v.5.0.1, SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Automated ligand docking

The homology model of the GABAAR used in this study was constructed as described.36 ESZ and ZPM were built using Sybyl Modeling software (Tripos Corp., St. Louis, MO). Each of the drug structures were energy minimized using the Tripos force field, then a random search was performed for the lowest energy conformations. The single lowest energy form was placed in the GABAAR α1/γ2 interface using Sybyl and a 15 Å sphere of residues around the ligand was chosen as the starting active site. The active site was setup for docking using AutoDock 4.0 Tools, placing Gatseiger charges and desolvation parameters on the chosen 15 Å receptor sphere. Autodock 450, 51 parameters were chosen for the Genetic Algorithm (GA) to examine 150 individuals in a population with a maximum of 5 million energy evaluations, followed by 300 iterations of Solis & Wets local search (Lakmarkian algorithm). A total of 10 to 30 of these hybrid dockings were performed on each drug. The binding results were clustered based upon lowest energy, visual similarities, and the orientation in the active site. The reported binding energies in kcal/mol is the sum of the final intermolecular energy, the internal energy of the ligand, and the torsional free energy minus the unbound systems energy. The orientation with stronger binding has the lower total energy and the cluster of highest number of bindings represents a higher probability of binding. The drug was allowed to flexibly dock, but the receptor’s backbone and side chains remained rigid during docking. Each docking gave an ensemble of docking modes, with many orientations nearly identical and only differing by less than 0.1 kcal/mol.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a research grant from Sepracor Inc. to C.C. and NIH grants F32 MH082504 to S.M.H and NS34727 to C.C. E.V.M. is supported by NIH training grant GM008688. We thank Susan Dunn for GABAAR cDNA constructs and Joseph Esquibel and James Raspanti for technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- BZD

benzodiazepine

- GABAAR

γ-aminobutyric acid type-A receptor

- ZPM

zolpidem

- ESZ

eszopiclone

- WT

wild-type

- i-BZD

imidazobenzodiazepine

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: pdb files containing eszopiclone and zolpidem docked at the BZD site of the GABAAR are provided. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Balter MB, Uhlenhuth EH. New epidemiologic findings about insomnia and its treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 1992;53(Suppl):34–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohayon MM. Epidemiology of insomnia: what we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;6(2):97–111. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2002.0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramakrishnan K, Scheid DC. Treatment options for insomnia. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76:517–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Darcourt G, Pringuey D, Salliere D, Lavoisy J. The safety and tolerability of zolpidem--an update. J Psychopharmacol. 1999;13(1):81–93. doi: 10.1177/026988119901300109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scharf MB, Roth T, Vogel GW, Walsh JK. A multicenter, placebo-controlled study evaluating zolpidem in the treatment of chronic insomnia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1994;55(5):192–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krystal AD, Walsh JK, Laska E, Caron J, Amato DA, Wessel TC, Roth T. Sustained efficacy of eszopiclone over 6 months of nightly treatment: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in adults with chronic insomnia. Sleep. 2003;26(7):793–799. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.7.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanger DJ. The pharmacology and mechanisms of action of new generation, non-benzodiazepine hypnotic agents. CNS Drugs. 2004;18(Suppl 1):9–15. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200418001-00004. discussion 41, 43-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wieland HA, Luddens H. Four amino acid exchanges convert a diazepam-insensitive, inverse agonist-preferring GABAA receptor into a diazepam-preferring GABAA receptor. J Med Chem. 1994;37(26):4576–4580. doi: 10.1021/jm00052a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pritchett DB, Seeburg PH. Gamma-aminobutyric acidA receptor alpha 5-subunit creates novel type II benzodiazepine receptor pharmacology. J Neurochem. 1990;54(5):1802–1804. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb01237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benavides J, Peny B, Durand A, Arbilla S, Scatton B. Comparative in vivo and in vitro regional selectivity of central omega (benzodiazepine) site ligands in inhibiting [3H]flumazenil binding in the rat central nervous system. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;263(2):884–896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rudolph U, Mohler H. GABA-based therapeutic approaches: GABAA receptor subtype functions. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2006;6(1):18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graham D, Faure C, Besnard F, Langer SZ. Pharmacological profile of benzodiazepine site ligands with recombinant GABAA receptor subtypes. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 1996;6(2):119–125. doi: 10.1016/0924-977x(95)00072-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sigel E. Mapping of the benzodiazepine recognition site on GABA(A) receptors. Curr Top Med Chem. 2002;2(8):833–839. doi: 10.2174/1568026023393444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wieland HA, Luddens H, Seeburg PH. A single histidine in GABAA receptors is essential for benzodiazepine agonist binding. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(3):1426–1429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan KR, Gonthier A, Baur R, Ernst M, Goeldner M, Sigel E. Proximity-accelerated chemical coupling reaction in the benzodiazepine-binding site of gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptors: superposition of different allosteric modulators. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(36):26316–26325. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702153200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berezhnoy D, Nyfeler Y, Gonthier A, Schwob H, Goeldner M, Sigel E. On the benzodiazepine binding pocket in GABAA receptors. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(5):3160–3168. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311371200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davies M, Newell JG, Derry JM, Martin IL, Dunn SM. Characterization of the interaction of zopiclone with gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;58(4):756–762. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.4.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davies M, Bateson AN, Dunn SM. Structural requirements for ligand interactions at the benzodiazepine recognition site of the GABA(A) receptor. J Neurochem. 1998;70(5):2188–2194. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70052188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duncalfe LL, Carpenter MR, Smillie LB, Martin IL, Dunn SM. The major site of photoaffinity labeling of the gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor by [3H]flunitrazepam is histidine 102 of the alpha subunit. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(16):9209–9214. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.16.9209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amin J, Brooks-Kayal A, Weiss DS. Two tyrosine residues on the alpha subunit are crucial for benzodiazepine binding and allosteric modulation of gamma-aminobutyric acidA receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;51(5):833–841. doi: 10.1124/mol.51.5.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Renard S, Olivier A, Granger P, Avenet P, Graham D, Sevrin M, George P, Besnard F. Structural elements of the gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor conferring subtype selectivity for benzodiazepine site ligands. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(19):13370–13374. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sigel E, Schaerer MT, Buhr A, Baur R. The benzodiazepine binding pocket of recombinant alpha1beta2gamma2 gamma-aminobutyric acidA receptors: relative orientation of ligands and amino acid side chains. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;54(6):1097–1105. doi: 10.1124/mol.54.6.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schaerer MT, Buhr A, Baur R, Sigel E. Amino acid residue 200 on the alpha1 subunit of GABA(A) receptors affects the interaction with selected benzodiazepine binding site ligands. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;354(23):283–287. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00456-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pritchett DB, Seeburg PH. gamma-Aminobutyric acid type A receptor point mutation increases the affinity of compounds for the benzodiazepine site. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88(4):1421–1425. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.4.1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buhr A, Schaerer MT, Baur R, Sigel E. Residues at positions 206 and 209 of the alpha1 subunit of gamma-aminobutyric AcidA receptors influence affinities for benzodiazepine binding site ligands. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;52(4):676–682. doi: 10.1124/mol.52.4.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sawyer GW, Chiara DC, Olsen RW, Cohen JB. Identification of the bovine gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor alpha subunit residues photolabeled by the imidazobenzodiazepine [3H]Ro15-4513. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(51):50036–50045. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209281200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Derry JM, Dunn SM, Davies M. Identification of a residue in the gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor alpha subunit that differentially affects diazepam-sensitive and -insensitive benzodiazepine site binding. J Neurochem. 2004;88(6):1431–1438. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strakhova MI, Harvey SC, Cook CM, Cook JM, Skolnick P. A single amino acid residue on the alpha(5) subunit (Ile215) is essential for ligand selectivity at alpha(5)beta(3)gamma(2) gamma-aminobutyric acid(A) receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;58(6):1434–1440. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.6.1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teissere JA, Czajkowski C. A (beta)-strand in the (gamma)2 subunit lines the benzodiazepine binding site of the GABA A receptor: structural rearrangements detected during channel gating. J Neurosci. 2001;21(14):4977–4986. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-14-04977.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kucken AM, Teissere JA, Seffinga-Clark J, Wagner DA, Czajkowski C. Structural requirements for imidazobenzodiazepine binding to GABA(A) receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63(2):289–296. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.2.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kucken AM, Wagner DA, Ward PR, Teissere JA, Boileau AJ, Czajkowski C. Identification of benzodiazepine binding site residues in the gamma2 subunit of the gamma-aminobutyric acid(A) receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;57(5):932–939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buhr A, Baur R, Sigel E. Subtle changes in residue 77 of the gamma subunit of alpha1beta2gamma2 GABAA receptors drastically alter the affinity for ligands of the benzodiazepine binding site. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(18):11799–11804. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.18.11799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wingrove PB, Thompson SA, Wafford KA, Whiting PJ. Key amino acids in the gamma subunit of the gamma-aminobutyric acidA receptor that determine ligand binding and modulation at the benzodiazepine site. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;52(5):874–881. doi: 10.1124/mol.52.5.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buhr A, Sigel E. A point mutation in the gamma2 subunit of gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptors results in altered benzodiazepine binding site specificity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(16):8824–8829. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sancar F, Ericksen SS, Kucken AM, Teissere JA, Czajkowski C. Structural determinants for high-affinity zolpidem binding to GABA-A receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71(1):38–46. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.029595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mercado J, Czajkowski C. Charged residues in the alpha1 and beta2 pre-M1 regions involved in GABAA receptor activation. J Neurosci. 2006;26(7):2031–2040. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4555-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hanson SM, Czajkowski C. Structural mechanisms underlying benzodiazepine modulation of the GABA(A) receptor. J Neurosci. 2008;28(13):3490–3499. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5727-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schreiber G, Fersht AR. Energetics of protein-protein interactions: analysis of the barnase-barstar interface by single mutations and double mutant cycles. J Mol Biol. 1995;248(2):478–486. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(95)80064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kumar S, Nussinov R. Salt bridge stability in monomeric proteins. J Mol Biol. 1999;293(5):1241–1255. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sharkey LM, Czajkowski C. Individually monitoring ligand-induced changes in the structure of the GABAA receptor at benzodiazepine binding site and non-binding site interfaces. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:203–212. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.044891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clayton T, Chen JL, Ernst M, Richter L, Cromer BA, Morton CJ, Ng H, Kaczorowski CC, Helmstetter FJ, Furtmuller R, Ecker G, Parker MW, Sieghart W, Cook JM. An updated unified pharmacophore model of the benzodiazepine binding site on gamma-aminobutyric acid(a) receptors: correlation with comparative models. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14(26):2755–2775. doi: 10.2174/092986707782360097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Puia G, Vicini S, Seeburg PH, Costa E. Influence of recombinant gamma-aminobutyric acid-A receptor subunit composition on the action of allosteric modulators of gamma-aminobutyric acid-gated Cl- currents. Mol Pharmacol. 1991;39(6):691–696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Herb A, Wisden W, Luddens H, Puia G, Vicini S, Seeburg PH. The third gamma subunit of the gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(4):1433–1437. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.4.1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hansen SB, Sulzenbacher G, Huxford T, Marchot P, Taylor P, Bourne Y. Structures of Aplysia AChBP complexes with nicotinic agonists and antagonists reveal distinctive binding interfaces and conformations. Embo J. 2005;24(20):3635–3646. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Celie PH, van Rossum-Fikkert SE, van Dijk WJ, Brejc K, Smit AB, Sixma TK. Nicotine and carbamylcholine binding to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors as studied in AChBP crystal structures. Neuron. 2004;41(6):907–914. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gao F, Bren N, Burghardt TP, Hansen S, Henchman RH, Taylor P, McCammon JA, Sine SM. Agonist-mediated conformational changes in acetylcholine-binding protein revealed by simulation and intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(9):8443–8451. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412389200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Venkatachalan SP, Bushman JD, Mercado JL, Sancar F, Christopherson KR, Boileau AJ. Optimized expression vector for ion channel studies in Xenopus oocytes and mammalian cells using alfalfa mosaic virus. Pflugers Arch. 2007;454(1):155–163. doi: 10.1007/s00424-006-0183-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Graham FL, van der Eb AJ. Transformation of rat cells by DNA of human adenovirus 5. Virology. 1973;54(2):536–539. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(73)90163-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boileau AJ, Kucken AM, Evers AR, Czajkowski C. Molecular dissection of benzodiazepine binding and allosteric coupling using chimeric gamma-aminobutyric acidA receptor subunits. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;53(2):295–303. doi: 10.1124/mol.53.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huey R, Morris GM, Olson AJ, Goodsell DS. A semiempirical free energy force field with charge-based desolvation. J Comput Chem. 2007;28(6):1145–1152. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morris GM, Goodsell DS, Halliday RS, Huey R, Hart WE, Belew RK, Olson AJ. Automated Docking Using a Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm and an Empirical Binding Free Energy Function. J Comput Chem. 1998;19:1639–1662. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Codding PW, Muir AK. Molecular structure of Ro15-1788 and a model for the binding of benzodiazepine receptor ligands. Structural identification of common features in antagonists. Mol Pharmacol. 1985;28(2):178–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wong G, Skolnick P. High affinity ligands for ‘diazepam-insensitive’ benzodiazepine receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;225(1):63–68. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(92)90040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.