Abstract

The peptidase nardilysin is involved in degradation of neuropeptides and limited intracellular proteolysis. Recent reports point to an involvement of nardilysin in the pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s disease. Nardilysin enhances the α-secretase activity of the disintegrin and metalloproteases (ADAMs) 10 and 17, thereby possibly contributing to reduced generation of amyloidogenic fragments from the amyloid precursor protein. A prerequisite for the α-secretase-stimulating effect of nardilysin on the activity of ADAMs in vivo is cellular co-expression of nardilysin with ADAM10 and/or ADAM17. We immunolocalised nardilysin, ADAM10, and ADAM17 in cortical regions of normal aged brain, in Alzheimer’s disease, and in Down syndrome brains and counted the number of protease-expressing neurons. A considerable portion of neurons co-express nardilysin together with either ADAM10 or ADAM17. Compared to controls, in Alzheimer’s disease and in Down syndrome brains there is a decreased cellular expression of all three antigens, and a reduction in the number of those neurons that co-express nardilysin with ADAM10 or with ADAM17. Our data are consistent with the notion that the proposed α-secretase-enhancing activity of nardilysin might play a role in human brain pathology.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Down syndrome, Human cerebral cortex, Immunohistochemistry, Metalloprotease

Introduction

Nardilysin (N-arginine dibasic convertase, EC 3.4.24.61; NRDc) is a metalloprotease belonging to the inverzincin/M16 family of metalloendopeptidases (Rawlings and Barrett 1993; Hooper 1994). NRDc cleaves peptides such as dynorphin-A, somatostatin-28, α-neoendorphin, and glucagon at the N-terminus of arginine and lysine residues in dibasic moieties in vitro (Chesneau et al. 1994; Pierotti et al. 1994; Bataille et al. 2006). However, the enzyme is also able to cut at a single basic residue (Chow et al. 2003). The cleavage specificity suggests that NRDc may be involved in processing and degradation of certain neuroactive peptides and may contribute to limited intra- and/or extracellular proteolysis. NRDc is mainly cytosolic, but is secreted by some cells, and is also found on the cell surface (Hospital et al. 2000).

In addition to its peptidase activity, NRDc binds to heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor (HB-EGF), which is known to be a potent stimulator of cell proliferation and migration (Nishi et al. 2001). Binding of NRDc to HB-EGF modulates the HB-EGF-induced cellular response. Moreover, NRDc enhances ectodomain shedding of HB-EGF through activation of the protease tumor necrosis factor-α-converting enzyme (TACE, aka ADAM 17), without involving the endogenous proteolytic activity of NRDc (Nishi et al. 2006). Furthermore, there is evidence that HB-EGF stimulates neurogenesis in proliferative zones of the adult brain by interacting with EGF receptor/ErbB1 and, possibly, NRDc (Jin et al. 2002). Recently, the brain specific protein p42IP4/centaurin-α1, which binds phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)P3/d-inositol(1,3,4,5)P4 (Stricker et al. 1997; Aggensteiner et al. 1998), was identified as an interacting partner for nardilysin (Chow et al. 2005; Stricker et al. 2006). We demonstrated that the interaction between NRDc and p42IP4 is regulated by the cognate ligands of p42IP4, phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)P3 and d-inositol(1,3,4,5)P4, whereby the action of the ligand is stereospecific (Stricker et al. 2006).

Taking into account the putative involvement of NRDc in neuropeptide metabolism and pivotal cellular processes such as neuronal proliferation, differentiation, and migration on the one hand, and the wide neuronal distribution of the enzyme in developing and adult human brain on the other (Bernstein et al. 2007; Hiraoka et al. 2007), it is of great interest to reveal the actual functional importance of NRDc for normal and diseased central nervous systems (CNS).

Very little is yet known about possible roles of NRDc in brain diseases; nonetheless, promising concepts on NRDc implication in normal brain function are beginning to emerge. Indeed, two recent reports point to an involvement of NRDc in the pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Firstly, in microarray studies, NRDc mRNA was found to be up-regulated in blood mononuclear cells of AD patients (Maes et al. 2007). Secondly, in cell culture experiments it was shown that the enzyme is capable of enhancing the α-secretase activity of ADAMs (a disintegrin and metalloproteases) 10 and 17 (Hiraoka et al. 2007). This possibly contributes to reduced generation of amyloidogenic fragments from the amyloid precursor protein (APP). This newly discovered action of NRDc may have considerable consequences with regard to our understanding of the mechanisms leading not only to late onset AD, but also to Down syndrome (DS) brain pathology. Down syndrome, or Trisomy 21, is a result of the presence of an extra copy of all or part of human chromosome 21. The phenotype of DS is thought to result from overexpression of a gene or genes located on the triplicated chromosome or chromosome region, including APP. Several reports have shown that the neuropathology of DS comprises developmental abnormalities and Alzheimer-like lesions such as neuritic plaques (for review, see Lott et al. 2006). A reduced interaction between NRDc and the ADAMs might contribute to the decreased C-terminus levels of APP in adult patients with Down syndrome, which is apparently the result of reduced α-secretase activity in these individuals (Nistor et al. 2007).

However, an indispensible prerequisite for the physiological significance of the α-secretase (ADAM)-stimulating effect of NRDc in vivo is the cellular co-expression of NRDc with either ADAM10 and/or ADAM17 in normal human brain, and, presumably, an altered co-distribution in AD and DS brains. Although both NRDc (Bernstein et al. 2007; Hiraoka et al. 2007) and ADAM10 and ADAM17 (Marcinkiewicz and Seidah 2000; Skovronsky et al. 2001; Bernstein et al. 2003) have been demonstrated to be expressed in subsets of human cortical neurons, there is as yet no anatomical evidence supporting a co-localisation of NRDc with either of the ADAMs in human brain. Since the abovementioned assumption of altered cellular co-expression of NRDc and ADAMs in AD and DS is a testable hypothesis of considerable importance, we decided to address the following questions: (1) Does NRDc appear to be co-expressed with either ADAM10 or ADAM17 in human brain cortical neurons? (2) Are the neuronal expression patterns of the metalloproteases NRDc, ADAM10, and ADAM17 altered in AD? (3) How is NRDc expressed in DS brains, and is there altered co-expression of NRDc and ADAM10 in DS brains during aging?

Materials and methods

A total of 33 brains were investigated here. Recruitment of brain material and all subsequent manipulations were done in strict accordance with the ethics and rules outlined by the ethics commission of the University of Magdeburg.

Adult human brains, AD brains

Autopsied brain specimens (superior temporal gyrus, angular gyrus, precentral gyrus, and posterior cingulate cortex) were obtained from eight clinically demented and neuropathologically confirmed cases with AD (four males, four females, mean age 69.5 years) and seven neurologically normal subjects (three males, four females, mean age 72.7 years) matched with regard to age, gender and postmortem time (mean 15 h for AD cases, 14.6 h for controls; see Table 1). Most of the control cases were admitted to a hospital with symptoms of cardiac failure or acute pulmonary symptoms. These patients had preserved cognitive abilities and were considered non-demented (with a mean Mini Mental State Examination score at the final admission of 28.3 ± 0.9 as determined for four of the seven control persons). Patients of the AD group showed severe cognitive deterioration and were classified clinically as AD according to the Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders–IV (DSM-IV). The mean Mini Mental State Examination score of this group was 15.1 ± 4.0 (Braunewell et al. 2001). After death, all but two AD cases were neuropathologically diagnosed as definite AD according to the criteria outlined by the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Two elderly cases were diagnosed as having AD on the basis of generally accepted hallmarks of the disease (e.g. senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles; Reiser and Bernstein 2002). To reveal the influence of normal aging on the expression of NRDc in cortical neurons we also analysed a second group of non-demented individuals who were considerably younger than the age-matched controls described above (three males, aged 49, 54 and 63 years, and three females, aged 54, 55 and 61 years; see Bernstein et al. 2007).

Table 1.

Description of cases used for immunohistochemical analysis. AD Alzheimer’s disease, DS Down syndrome

| Case | Agea | Gender | Timeb | Cause of death |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADc | 78 | Female | 11 | Duodenal carcinoma |

| ADc | 70 | Male | 19 | Heart failure |

| AD | 42 | Male | 13 | Heart failure |

| AD | 76 | Female | 9 | Bronchopneumonia |

| ADc | 78 | Female | 10 | Embolism of the lung |

| ADc | 69 | Male | 20 | Heart failure |

| ADc | 73 | Female | 21 | Heart failure |

| ADc | 70 | Male | 17 | Esophageal carcinoma |

| Control | 72 | Female | 11 | Heart failure, thrombosis |

| Control | 81 | Female | 13 | Heart failure, arteriosclerosis |

| Control | 69 | Female | 11 | Bronchopneumonia |

| Control | 73 | Male | 10 | Myocardial insufficiency |

| Control | 71 | Male | 18 | Carcinoma of the stomach |

| Control | 72 | Male | 19 | Heart failure |

| Control | 71 | Female | 20 | Heart failure |

| yControld | 61 | Female | 19 | Myocardial infarction |

| yControl | 49 | Male | 12 | Pulmonary embolism |

| yControl | 54 | Male | 14 | Heart failure |

| yControl | 55 | Female | 20 | Pulmonary embolism |

| yControl | 54 | Female | 15 | Pulmonary embolism |

| yControl | 63 | Male | 11 | Heart failure |

| Fetus | 18 w | Female | 3 | Abort, clinical indication |

| Fetus | 27 w | Male | 1 | Preterm stillborn |

| Fetus | 32 w | Male | 2 | Preterm, stillborn |

| Child | 39 w | Female | 2 | Preterm, stillborn |

| Child | 41 w | Female | 1 | Term, stillborn |

| Child | 42 w | Male | 2 | Term, stillborn |

| DS fetus | 24 w | Female | 1 | Abort, clinical indication |

| DS child | 1 | Male | 8 | Heart failure |

| DS child | 6 | Male | 11 | Heart failure |

| DS adult | 42 | Male | 11 | Heart failure, coeliac disease |

| DS adult | 51 | Male | 15 | Heart failure |

| DS adult | 63 | Male | 14 | Heart failure, coeliac disease |

aAge (w week of gestation, otherwise years) of patients

bTime (h) between clinical death and fixation of the specimens

cNeuropathologically diagnosed as definite AD according to Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD)

dYounger controls

Pre-and perinatal brains, DS brains

Six brains were from subjects with genetically established Down syndrome (DS; Bernstein et al. 1996, 2003); three of these were children aged 6 months, 1 year and 6 years (two males, one female); and three brains were obtained from adult male DS patients aged 42, 51 and 63 years.

Human pre- and perinatal brains were obtained from fetuses as well as from preterm and term stillborn children (three females and three males). The ages of these fetuses and children were 18, 27, 32, 39, 41 and 42 weeks of gestation. Brains were removed as quickly as possible (less than 3 h after death) and dissected into tissue blocks of about 1 cm3. The anterior cingulate and superior temporal cortex were investigated. Further tissue processing procedures were carried out as for adult brains. All pre- and perinatal brains were seen by an experienced pediatric neuropathologist (Professor emeritus I. Röse, formerly University of Magdeburg, see Bernstein et al. 1987).

Brain tissue processing, immunohistochemistry

The brain material was removed as quickly as possible. The specimens were cut into small blocks of 1 cm3 (Bernstein et al. 1999). These blocks were rinsed with 0.05 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4) and fixed in ice-cold paraformaldehyde solution. After a fixation time of 24–72 h the brain specimens were embedded in paraffin and cut into 20 µm serial sections. Every tenth section was stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE). Selected sections were stained for Congo red, Bielschowsky, and the immunohistochemical markers Alzheimer precursor protein A4 (Boehringer Mannheim, Germany) and Alz 50 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The latter marker was used to define Braak stages in our material by a modified protocol (Bernstein et al. 2003). The cases were coded and randomised (for blinding conditions) over the different experimental protocols.

Sections were selected at intervals of about 0.8 mm. NRDc immunoreactive material was detected with a well-characterised (Bernstein et al. 2007) goat polyclonal antiserum against NRDc (N20, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). This antiserum recognises both human NRDc1- and NRDc2-isoforms (data not shown). After dewaxing, the sections were boiled in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0) and then preincubated with methanol/H2O2 to depress endogenous peroxidases. After repeated washing with PBS, the antibody was applied in a working dilution of 1:200 in PBS. Further steps involved the application of the avidin–biotin method (Vectastain-peroxidase kit) with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine as chromogen to visualise the reaction product. Control experiments to verify the specificity of the immunoreaction included replacement of the specific antibodies with buffer or normal (non-immune) serum (Bernstein et al. 2007).

ADAM10 and ADAM17 were immunolocalised by employing polyclonal antisera generated in rabbits against the cytoplasmic regions of the enzymes (anti-ADAM10 from R&D Systems, Wiesbaden-Nordenstadt, Germany; anti-ADAM17 from Biomol, Hamburg, Germany) as previously described (Bernstein et al. 2003). The protocols for immunohistochemical stainings involved preincubation of the sections with methanol/H2O2 to depress endogenous peroxidases. After repeated washing with PBS, the antisera were applied in working dilutions of 1:300 (ADAM10) or 1:200 (ADAM17) in PBS. After another washing step with PBS the sections were incubated with anti-rabbit IgG (raised in sheep; Sigma) for 2 h at room temperature, and then with the PAP-complex (Sigma) for another 2 h. Nickel ammonium sulfate-enhanced 3,3′-diaminobenzidine served as the chromogen (yielding a purplish to dark-blue colour reaction product) to visualise the immunoreaction product for both ADAMs (Bernstein et al. 1999). For purposes of control, the specific antisera were substituted either by normal rabbit serum or buffer. In addition, our NRDc and ADAM10 antisera were previously characterised in detail by Western blot analysis and immunohistochemical studies of postmortem human brain tissue (Bernstein et al. 2003, 2007).

The double immunolabelling procedure for NRDc and the ADAMs involved the use of the above described technique to immunolocalise NRDc, followed by the application of Sternberger’s unlabeled immunoenzyme (PAP) technique with nickel ammonium sulfate-enhanced 3,3′-diaminobenzidine as the chromogen (yielding a blue-violet reaction product) to co-localise ADAM10 and ADAM17, respectively. To prevent any cross-reaction between the two different polyclonal antibodies or the subsequently applied secondary antisera, the sections were incubated with non-immunised normal rabbit IgG (1:500, dilution in 2% BSA-PBS) between the incubation steps (Arvidsson et al. 1997).

Morphometric analysis

To quantitatively evaluate the cellular distribution of NRDc, ADAM10, and ADAM17, we counted the number of antigen-expressing neurons in two areas of the neocortex (cortical layers of the left hemispherical temporal and angular cortex). The section thickness after the histological procedures was 19.0 ± 0.3 µm (mean ± SD). A counting grid (square of the counting frame 0.0625 mm2) was used to define a three-dimensional (3D) box within the thickness of the section as described earlier (Bernstein et al. 1998) allowing guard zones of at least 4-µm at the top and bottom of the section, and to apply a direct 3D counting method. NRDc-, ADAM10 - and ADAM17-immunopositive neurons were counted separately in a linear probe of stacked counting boxes extending from the pial surface to the underlying white matter (Selemon et al. 2003). Laminar boundaries, which were most clearly visible at low power (6.3x), were marked on the linear probes by switching back and forth between 6.3x and 40x objectives during the analysis so that cell density for each of the six layers could be calculated. The total length of the linear probe provided a measurement of cortical thickness. Values from the 5 linear probes were averaged to obtain a mean value of neuronal density. Fifteen boxes per cortical layer were counted. We examined the densities of all (HE-stained) neurons in these areas as published (Spiechowicz et al. 2006).

Statistical analysis

Cell densities and proportionate thickness of the six cortical layers were analysed with a repeated-measurement ANOVA. A Bonferroni correction was applied to take into account the large number of comparisons. A P-value of <0.05 was regarded as significant.

Results

Cortical distribution of NRDc immunoreactive neurons in control brains

Consistent with our previous report (Bernstein et al. 2007), NRDc immunoreactive neurons were found in all cortical areas under investigation. Almost all layer III and V pyramidal neurons showed immunolabelling. Some of them stood out because of very intense staining. Numerous interneurons were also found to express the protein (Fig. 1a). The density of NRDc-containing neurons was somewhat higher in the angular gyrus than in the superior temporal cortex (Table 2).

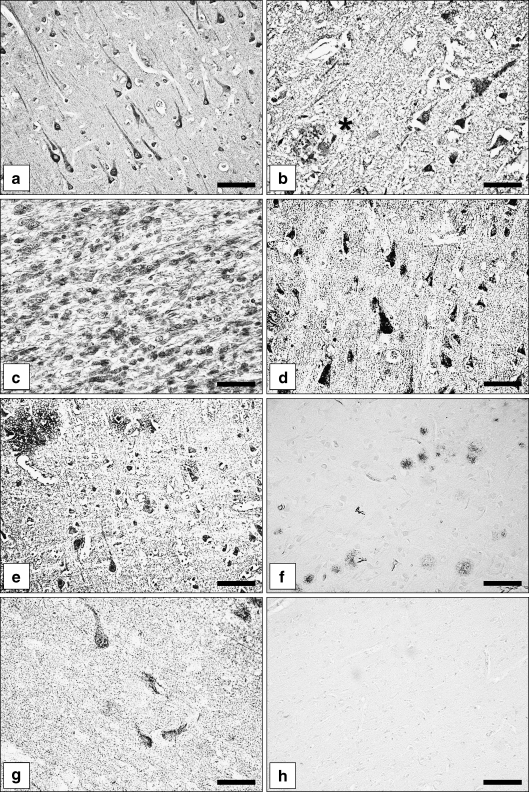

Fig. 1.

Immunohistochemical localisation of the metalloprotease nardilysin (N-arginine dibasic convertase; NRDc) in normal aged human brains, Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) brains and Down syndrome (DS) brains. a,b Expression of NRDc protein in the superior temporal cortex neurons of a control case (a) and an AD case (b). Note neuritic plaque decorated with NRDc immunoreactive material (asterisk). c NRDc immunoreactive neurons in the developing temporal cortex of a DS fetus (gestational week 24). Multiple neuroblasts express the metalloprotease. d NRDc immunoreactive pyramidal neurons in a DS child (6 years). e NRDc immunoreactive neurons and immunostained diffuse plaques in an adult DS patient. f Low power microphotograph showing multiple neuritic plaques immunolabelled with Alzheimer precursor protein A4 antibody; superior temporal cortex, AD case. g Alz 50 immunoreactive neurons in the superior temporal cortex of an AD case. h Specificity control. No immunostaining upon replacement of NRDc antiserum with normal goat serum. Bars a,d,e,g,h 50 µm; b 35 µm; c 30 µm; f 80 µm

Table 2.

Density (mean ± SD cells mm−3) × 103 of hematoxylin and eosin (HE)-stained, nardilysin (N-arginine dibasic convertase; NRDc), disintegrin and metalloproteases ADAM10 and ADAM17 immunoreactive (ir) neurons in the left hemispherical superior temporal (TC) and angular (AC) cortex in Alzheimer disease (AD) and healthy aged (C) groups

| Cortical layer | HE-staineda | NRDc-ir | ADAM10-ir | ADAM17-ir | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | AD | C | AD | C | AD | C | AD | |

| TC | ||||||||

| I | 7.3 ± 1.2 | 6.4 ± 1.6 | 2.4 ± 0.9 | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 1.7 ± 0.3 |

| II | 31.0 ± 7.5 | 28.9 ± 4.9 | 16.0 ± 3.3 | 10.2 ± 2.7* | 9.5 ± 0.6 | 7.0 ± 0.8** | 15.0 ± 1.3 | 11.9 ± 1.1* |

| III | 27.9 ± 6.1 | 24.1 ± 4.9 | 10.9 ± 3.0 | 8.9 ± 2.0 | 11.0 ± 1.5 | 8.0 ± 1.6* | 12.0 ± 2.9 | 12.3 ± 2.1 |

| IV | 32.1 ± 5.5 | 31.1 ± 7.0 | 13.3 ± 2.8 | 8.2 ± 3.0** | 14.2 ± 2.4 | 10.2 ± 1.5** | 13.0 ± 4.0 | 11.9 ± 3.4 |

| V/VI | 31.9 ± 9.2 | 26.5 ± 7.8 | 18.9 ± 4.6 | 10.9 ± 3.3** | 15.6 ± 5.0 | 12.0 ± 3.8 | 14.6 ± 3.3 | 12.0 ± 2.7 |

| AC | ||||||||

| I | 8.9 ± 2.2 | 7.9 ± 1.9 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.3 |

| II | 57.1 ± 11.1 | 56.4 ± 9.6 | 22.2 ± 5.8 | 14.0 ± 3.4* | 16.0 ± 4.1 | 13.6 ± 3.1 | 21.3 ± 5.6 | 8.8 ± 4.4 |

| III | 54.0 ± 7.7 | 51.1 ± 6.8 | 21.9 ± 3.9 | 15.2 ± 2.5* | 14.6 ± 3.0 | 9.3 ± 2.3** | 28.1 ± 4.4 | 21.5 ± 3.0* |

| IV | 52.7 ± 3.8 | 50.3 ± 5.5 | 19.0 ± 4.0 | 14.5 ± 3.2 | 14.5 ± 2.9 | 10.3 ± 2.7* | 22.2 ± 5.0 | 19.2 ± 4.3 |

| V/VI | 46.9 ± 8.8 | 47.2 ± 7.2 | 23.2 ± 3.3 | 16.0 ± 2.9** | 17.6 ± 3.2 | 15.2 ± 3.5 | 20.6 ± 6.0 | 16.7 ± 5.1 |

* P< 0.05, ** P < 0.01

aDensity of HE-stained neurons was taken from a previous paper where the same cases were studied (Spiechowicz et al. 2006)

Cortical expression of NRDc immunoreactivity during normal brain aging

Qualitatively, there was no obvious difference in the distribution of NRDc in superior temporal cortex neurons between middle-aged human controls (referred to as yControls, mean age 55 years) and aged controls (referred as to C; mean age 73 years). However, when counting the number of NRDc-expressing neurons, a small but significant reduction was found in layer IV in the aged control group (Table 3). No difference between the groups was seen with regard to the density of HE-stained neurons.

Table 3.

Density (mean ± SD cells mm−3) × 103 of HE-stained and NRDc immunoreactive (ir) neurons in the left hemispherical temporal (TC) cortex of healthy aged (C) and younger control (yControl) individuals

| Cortical layer | HE-staineda | NRDc-ir | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | yControl | C | yControl | |

| TC | ||||

| I | 7.3 ± 1.2 | 7.4 ± 1.6 | 2.4 ± 0.9 | 2.5 ± 0.6 |

| II | 31.0 ± 7.5 | 33.0 ± 5.6 | 16.0 ± 3.3 | 18.2 ± 3.0 |

| III | 27.9 ± 6.1 | 29.1 ± 5.2 | 10.9 ± 3.0 | 11.5 ± 2.0 |

| IV | 32.1 ± 5.5 | 33.1 ± 5.3 | 13.3 ± 2.8 | 18.8 ± 2.6** |

| V/VI | 31.9 ± 9.2 | 31.6 ± 4.9 | 18.9 ± 4.6 | 19.9 ± 3.8 |

** P< 0.01

aDensity of HE-stained neurons was taken from a previous paper where the same cases were studied (Spiechowicz et al. 2006)

Cortical expression of NRDc immunoreactivity in AD brains

Besides immunostained pyramidal cells and neurons, we frequently observed NRDc immunopositive plaques in AD cases (Fig. 1b). These plaques were seen in all but one AD case. Quantitatively, reduced numbers of NRDc-expressing cortical neurons were found in both cortical areas under investigation. Layer-specific analysis revealed that significant reductions appeared in cortex layers II, IV and V/VI (superior temporal cortex) and in layers II, III and V/VI (angular cortex), as can be seen in Table 2.

To demonstrate plaque and tangles pathology in our material, we made immunostainings for Alz 50 (intracellular tangle labelling) and amyloid precursor protein A4 (neuritic plaque labelling), as shown in the examples in Fig. 1f and g.

Cortical distribution of NRDc in DS brains

NRDc immunoreactive material was already detectable in DS fetal human cortex as in normal pre- and perinatal brain (Bernstein et al. 2007). Quantitative analysis of NRDc-expressing cells revealed that more than 50% of the cells present are immunolabelled at this time: both neuroblasts and non-neuronal cells (probably radial glia) were immunostained (Fig. 1c). The density of NRDc immunoreactive neurons in the cortex of DS children was 55 ± 7 × 103 cells mm−3 (1 year; data not shown) and 45 ± 9 × 103 cells mm−3 (6 years, Fig. 1d). In the brains of adult DS patients the density was well below that of controls (see Table 5). Single NRDc immunoreactive neuritic plaques were observed in adult DS cases (Fig. 1e).

Table 5.

Density (mean ± SD cells mm−3) × 103 of HE-stained, NRDc and ADAM10 immunoreactive (ir) neurons as well as of NRDc/ADAM10 co-expressing cells in the left hemispherical temporal (TC) of adult patients with Down syndrome (DS, n = 3) and younger controls (yControl, n = 5)

| Cortical layer | HE-staineda | NRDc-ir | ADAM10-ir | NRDc-ir/ADAM10-ir | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| yControl | DS | yControl | DS | yControl | DS | yControl | DS | |

| TC | ||||||||

| I | 7.4 ± 1.2 | 6.4 ± 1.6 | 2.4 ± 0.9 | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 0.7 ± 01 | 0.4 ± 0.1* |

| II | 31.0 ± 7.5 | 28.9 ± 4.9 | 16.0 ± 3.3 | 10.2 ± 2.7* | 9.5 ± 0.6 | 7.0 ± 0.8** | 5.7 ± 0.9 | 2.2 ± 0.3** |

| III | 27.9 ± 6.1 | 24.1 ± 4.9 | 10.9 ± 3.0 | 5.9 ± 2.0** | 11.0 ± 1.5 | 8.0 ± 1.6* | 6.0 ± 0.5 | 3.2 ± 0.3** |

| IV | 32.1 ± 5.5 | 30.1 ± 7.0 | 13.3 ± 2.8 | 7.2 ± 3.0** | 14.2 ± 2.4 | 10.2 ± 1.5** | 3.5 ± 0.3 | 2.3 ± 0.3** |

| V/VI | 31.9 ± 9.2 | 26.5 ± 7.8 | 18.9 ± 4.6 | 10.9 ± 3.3** | 15.6 ± 5.0 | 12.0 ± 3.8 | 6.2 ± 0.7 | 4.0 ± 0.4** |

* P< 0.05, **P < 0.01

aDensity of HE-stained neurons was taken from a previous paper where the same cases were studied (Spiechowicz et al. 2006)

Cortical expression of ADAM10 in control brains

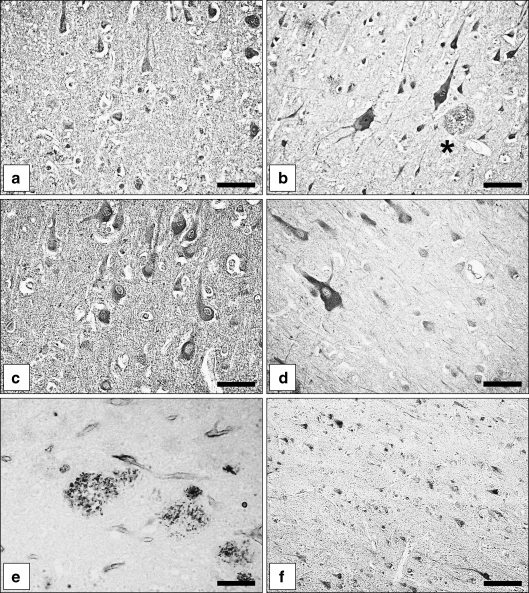

Moderately immunostained pyramidal and non-pyramidal neurons were distributed throughout layers I–VI in both cortical areas (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

Immunohistochemical localisation of ADAM10 and ADAM17 in normal brains, AD brains and DS brains. a,b ADAM10 immunoreactive angular cortex neurons in a control case (a) and an AD case (b). Besides neurons, extracellular plaques contain ADAM10 immunoreactive material (asterisk). c ADAM10 immunoreactive neurons in a DS child (1 year). d Expression of ADAM10 in neurons of an adult DS patient (51 years). e Localisation of ADAM10 immunoreactive material in neuritic plaques of an adult DS patient (42 years). f ADAM17 immunoreactive superior temporal cortex neurons (control case). Bars a,c,e 35 µm; b,d 25 µm; f 75 µm

Cortical distribution of ADAM10 in pre- and perinatal control brains

As documented previously (Bernstein et al. 2003) pre-and perinatal brains showed weak to moderate immunostaining for ADAM10 in the cytoplasm of numerous pyramidal and non-pyramidal neurons (data not shown).

Cortical expression of ADAM10 in AD brains

As reported earlier (Bernstein et al. 2003), in AD brains ADAM10 immunoreactivity was detected in many pyramidal and non-pyramidal neurons. In addition, many diffuse and neuritic plaques were immunopositive for the enzyme protein (Fig. 2b). Quantitative analysis of ADAM10 immunoreactive neurons revealed significantly fewer neurons in layers II, III, and IV in TC and layers III and IV in AC (Table 2).

Cortical expression of ADAM10 in DS brains

In postnatal and juvenile cases, the distribution pattern and the intracellular localisation of ADAM10 immunoreactivity was very similar to that seen in normal perinatal brains (Bernstein et al. 2003). A moderate to strong immunostaining was found in pyramidal cells of layers III and V as well as in some interneurons (Fig. 2c). In the three adult DS brains, numerous neurons were immunopositive for ADAM10 (Fig. 2d). In addition, ADAM10 immunoreactive material decorated multiple neuritic plaques (Fig. 2e).

Cortical expression of ADAM17 in normal brain

ADAM17 was found in neurons and glial cells. The enzyme protein was present in pyramidal and non-pyramidal cells distributed throughout all cortical layers (Fig. 2f).

Cortical expression of ADAM17 in AD brains

In comparison to controls there was no qualitative difference in the localisation of ADAM17 in AD brains. ADAM17 immunoreactive plaques were never observed, which corresponds well to earlier findings of others (Skovronsky et al. 2001). A significantly reduced density of ADAM17-containing neurons was found for cortical layers II (TC) and III (AC), as evident from Table 2.

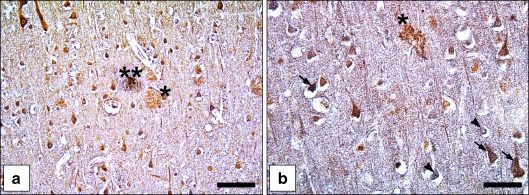

Co-expression of NRDc and ADAM10 in normal aged and AD brains

Co-labelling experiments revealed that, in control brains, depending on the cortex area and the cortical layer, 25–35% of NRDc immunoreactive neurons co-express ADAM10, and 20–25% of ADAM10-containing neurons are also immunopositive for NRDc. Furthermore, most of the diffuse and neuritic plaques were either immunoreactive for NRDc or ADAM10. Only a small percentage (about 10% in the superior temporal cortex and 12% in the angular cortex) were found to contain both antigens (Fig. 3a, Table 4).

Fig. 3.

Neuronal co-expression of NRDc, ADAM10 and ADAM17 in AD brains. a Double immunolabelling for NRDc and ADAM10 in the superior temporal cortex of an AD case. Brown-coloured neurons contain only NRDc, blue neurons contain only ADAM10, brownish-violet neurons express both antigens. One of the plaques is only NRDc immunopositive (asterisk), the other one is immunopositive for both antigens (two asterisks). b Double immunostaining for NRDc and ADAM17 in the superior temporal cortex of an AD case. Brown neurons are immunoreactive for NRDc only, blue neurons for ADAM17 only (arrowhead), and brownish-violet ones for both antigens (arrows). The plaque is immunoreactive for NRDc but not for ADAM17 (asterisk). Bars a 75 µm, b 50 µm

Table 4.

Co-localisation of NRDc with ADAM10 or ADAM17 in neurons in the left hemispherical temporal (TC) and angular (AC) cortex in Alzheimer disease (AD) and healthy aged (C) individuals. Density (mean ± SD cells mm−3) × 103 of immunoreactive (ir) neurons

| Cortical layer | NRDc-ir with ADAM10-ir | NRDc-ir with ADAM17- ir | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | AD | % of control | C | AD | % of control | |

| TC | ||||||

| I | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 100 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 100 |

| II | 4.8 ± 0.7 | 3.6 ± 0.5** | 75 | 5.0 ± 0.9 | 4.7 ± 0.8 | 94 |

| III | 5.5 ± 1.0 | 3.7 ± 0.9* | 67 | 4.3 ± 0.6 | 2.5 ± 0.8** | 58 |

| IV | 3.9 ± 0.7 | 2.0 ± 0.9* | 54 | 4.0 ± 1.0 | 3.5 ± 0.7 | 88 |

| V/VI | 6.0 ± 1.1 | 4.3 ± 0.7* | 72 | 4.2 ± 0.5 | 3.1 ± 0.5* | 74 |

| AC | ||||||

| I | 0 | 0 | - | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 50 |

| II | 5.2 ± 0.6 | 4.0 ± 0.5** | 77 | 6.0 ± 0.7 | 4.5 ± 0.6** | 75 |

| III | 6.3 ± 1.0 | 5.6 ± 0.9 | 89 | 5.5 ± 0.5 | 5.3 ± 0.7 | 96 |

| IV | 5.7 ± 0.6 | 4.4 ± 0.6** | 77 | 4.9 ± 0.8 | 4.2 ± 0.8 | 86 |

| V/VI | 8.2 ± 1.1 | 6.5 ± 0.7* | 79 | 6.2 ± 0.6 | 4.6 ± 1.0** | 74 |

* P< 0.05, **P < 0.01

Co-expression of NRDc and ADAM17 in normal aged and AD brains

In normal aged brains, the portion of NRDc immunoreactive cells co-expressing ADAM17 was roughly the same as for ADAM10, whereas only about 15% of ADAM17 immunoreactive neurons were also labelled for NRDc. In AD brains, a significant reduction of the density of double-labelled neurons was found in layers II and V/VI in both cortical areas. Identified neuritic plaques were immunoreactive for NRDc only (Fig. 3b, Table 4).

Cortical co-expression of NRDc and ADAM10 in adult DS brains

Cell counts revealed a significant reduction (up to 65% of controls) of double-labelled neurons in all six layers of the superior temporal cortex (Table 5). Neuritic plaques contained ADAM10 only, or were immunoreactive for both NRDc and ADAM10.

Discussion

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most prominent form of dementia, and numerous efforts are currently being directed towards finding disease-modifying therapies. Promotion of the non-amyloidogenic pathway through stimulation of α-secretases is a potential way to treat the disease (see Fig. 4, and Fahrenholz 2007). Activators of ADAMs are therefore potential targets for treatment (Bandyopadhyay et al. 2007; Hiraoka et al. 2007). Down syndrome provides a useful model to study important aspects of AD, since the life-long overexpression of APP in DS patients leads to a progressive accumulation of Aβ in neuritic plaques and the formation of neurofibrillary tangles, consistent with Braak stages V and VI (Lott et al. 2006). In both AD and DS, a reduced interaction between NRDc and the ADAMs might theoretically contribute to the decreased C-terminus levels of APP and soluble APPα in adult patients by lowering α-secretase activity in cells, where they are expressed together.

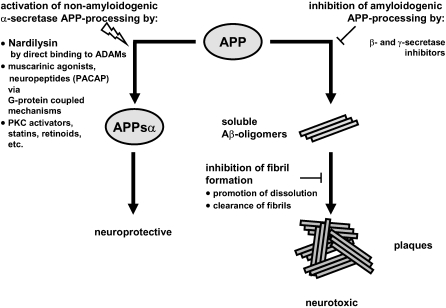

Fig. 4.

Schematic representation of activation of α-secretase as a target for the therapy of Alzheimer’s disease. The scheme is based on Fig. 3 from the excellent review by Fahrenholz (2007) on this topic. Activation of non-amyloidogenic amyloid precursor protein (APP)-processing by α-secretases prevents the generation of neurotoxic Aβ proteins. The non-amyloidogenic pathway can be enhanced by several compounds and pathways, including the direct interaction of the enzyme NRDc with α-secretase (Hiraoka et al. 2007). In addition, inhibition of amyloidogenic APP-processing and clearance of fibrils are also indicated as potential opportunities for therapeutic interventions (Skovronsky et al. 2006). In addition, Aβ peptides can be eliminated by degrading enzymes, like neprilysin or insulin-degrading enzyme (reviewed in Fahrenholz (2007)

The main finding of this study is that the metalloproteases NRDc, ADAM10, and ADAM17 are indeed co-expressed in subsets of cortical neurons in human aged brains, with a significant reduction of expression overlap in AD and an even more striking reduction in adult DS. Thus, a molecular interaction of NRDc and ADAM10 and/or ADAM17 within the same cell in human brain neurons is possible. This may result in an enhancement of ADAM-associated α-secretase activity. An NRDc/ADAM17 interaction in cultured cells has been described by Hiraoka et al. (2007), who showed that NRDc and ADAM17 can form molecular complexes. This process is promoted by phorbol esters. If we suppose that this mechanism actually functions in human brain neurons, it could contribute to a reduced amyloid load of the brain via stimulation of non-amyloidogenic APP cleavage. The observed reduction in NRDc co-localised with either ADAM10 or ADAM17 in AD and ADAM10 in DS brains might mean that, in the diseased brain, fewer neurons benefit from the α-secretase-stimulating effect of NRDc on ADAMs. This in turn might compromise the non-amyloidogenic pathway of APP. However, the question remains whether the ADAMs really need support from NRDc to work properly as α-secretases in human brain, besides their numerous other functions in the CNS (see Kieseier et al. 2003; Yang et al. 2006; Bell et al. 2008; Deuss et al. 2008). This is obviously not necessarily the case, because in the non-demented brains (in both aged and middle-aged cases) we observed numerous neurons expressing either NRDc or ADAMs without apparent co-expression. It is even possible that some cortical neurons are immunonegative for all three antigens. It is currently not known, however, whether these neurons are more prone to neurodegenerative processes than those that express ADAMs, or a combination of one or two ADAM proteases and NRDc. Furthermore, several factors have already been identified as potential enhancers of the α-secretase activity of ADAMs, such as protein kinase C-activating phorbol esters, interleukin-1 (Bandyopadhyay et al. 2007; Yang et al. 2007), muscarinic agonists, pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide, and retinoic acid, as depicted in the schematic in Fig. 4. However, their expression and activation patterns in human brain in relation to those of ADAMs are yet very poorly explored. Therapeutic intervention is also possible by avoiding the neurotoxic effects of amyloidogenic APP-processing through inhibition of β-or γ-secretase, through inhibition of fibril formation or through fibril clearance, as depicted in the alternative pathway in Fig. 4.

It should be noted, however, that, in addition, NRDc might be involved in AD and DS neuropathology in a way which is independent of its interaction with ADAMs. Maes et al. (2007) found that NRDc mRNA was up-regulated in blood cells from AD patients. We counted fewer NRDc immunoreactive cortical neurons in normal aged brains compared to non-demented middle-aged brains, and found a further reduction in AD and DS brains. The latter finding does not necessarily contradict the results of Maes and colleagues, since, in AD and DS brains, an unknown amount of NRDc protein is associated with the numerous neuritic plaques. Thus, the total amount of NRDc protein might be even higher in AD and DS brains than in the matched controls. However, the amount of neuron-associated NRDc is obviously lower in the cortices of AD and DS brains. Less neuronal NRDc might, for example, affect neuropeptide levels in AD brains. In this way, NRDc might contribute to the dysregulation of dynorphins in AD (Yakovleva et al. 2007) and, possibly, to the elevated levels of the isoform somatostatin-28 (Pierotti et al. 1994; Winsky-Sommerer et al. 2003), which appear in parallel to the well-documented general somatostatin deficit in AD (Rossor et al. 1984; Beal et al. 1987; Mouradian et al. 1991; Dournaud et al. 1995). Although there is only little, if any, overlap of NRDc and somatostatin-28 immunoreactive nerve cell bodies in human brain (Bernstein et al. 2007), a reduced somatostatin-28 metabolising function of NRDc (Csuhai et al. 1998) cannot be ruled out in AD. In addition, NRDc has been demonstrated to interact with p42IP4/centaurin-α1 (Stricker et al. 2006), which seems to play a role in AD (Reiser and Bernstein 2002, 2004). NRDc has also been reported to facilitate complex formation between mitochondrial malate dehydrogenase and citrate synthase (Chow et al. 2005). The activity of malate dehydrogenase is increased in AD brain (Bubber et al. 2005). Lastly, NRDc enhances shedding of HB-EGF (Nishi et al. 2006), which augments adult brain neurogenesis. Increased hippocampal neurogenesis was observed in AD (Jin et al. 2004).

Concerning DS, there is as yet no information at all about putative roles of NRDc. We show here that there is a strong decline of neuronal NRDc expression with age in DS brains. A reduced cellular expression of ADAM10 in the neocortex of adult DS patients has been described previously (Bernstein et al. 2003), which is in line with the recently reported reduced α-secretase activity in DS brains (Nistor et al. 2007). Again, if we suppose that the interaction of NRDc and ADAM is physiologically relevant, the observed decline in the number of cells that co-express NRDc and ADAM10 might be a morphological correlate of the reduced α-secretase activity in DS brains. In the case of DS, we did not investigate the other putative α-secretase, ADAM17, for the following reason. ADAM17 (TACE) is a major TNF-α shedding enzyme, and its shedding activity is enhanced by nardilysin (Hiraoka et al. 2008). TNF-α is well-known to be overexpressed in the thymus and other tissues of DS patients, at least of those patients suffering from coeliac disease (Murphy et al. 1992a, b, 1995; Cataldo et al. 2005). Since two of the three adult DS patients studied here had suffered from this disease, an altered expression of ADAM17 and/or its co-expression with NRDc could possibly have been the result of the immune disease-related altered TNF-α expression, and not of the life-long over-expression of APP. To avoid any misleading interpretations, we studied the co-localisation of NRDc and ADAM10 only.

A question of fundamental importance is whether reduced NRDc-ADAM co-expression in AD and DS is one of the causes or a consequence of the neurodegenerative changes in both diseases. Unfortunately, the AD cases studied here are—according to Alz 50 immunostainings—late Braak stages of the disease (IV–VI). It would be very interesting to see how NRDc and the ADAMs are located in early stages of the disease. Since we have no indication in favour of a significant cell loss in our cases (see Results), we suggest that the co-expression of NRDc and the ADAMs is reduced in still-existing neurons. In DS, we find a decrease in the number of NRDc and ADAM immunoreactive cells with age, and a reduction of co-expression in adult DS patients. The way to solve this “chicken-and egg” dilemma may be the use of knock-out mice for NRDc and ADAMs overexpressing human APP. This, however, should be a goal of forthcoming investigations.

In summary, our data suggest that NRDc may well be associated with many processes that are known to be impaired in AD and DS brains, including a role in α-secretase function. Hence, the enzyme is a potential target for drug intervention—not only with regard to its α-secretase-enhancing properties (Hiraoka et al. 2007), but possibly also for other important cerebral functions.

Conclusion

The neuroanatomical findings shown here demonstrate that, in human cerebral cortex, nardilysin and two putative α-secretases—ADAM10 and ADAM17—are co-localised in neurons in healthy aged brain, but the co-localisation is reduced in Alzheimer’s disease and Down syndrome brain. The important prerequisite that the α-secretase-stimulating effect of NRDc on the activity of ADAMs is physiologically relevant for the in vivo situation is cellular co-expression of NRDc with either ADAM10 and/or ADAM17 in normal human brain. This condition seems to be fulfilled, as we demonstrate here. Since NRDc may also be associated with other, α-secretase-independent processes, which are known to be impaired in AD and DS brains, the enzyme NRDc is a promising target for drug intervention.

Acknowledgement

The work was supported by a grant from Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF grant 01ZZ0407).

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- ADAM

A disintegrin and metalloprotease

- Alz 50

Alzheimer 50 (marker)

- ANOVA

Analysis of variance

- APP

Amyloid precursor protein

- CERAD

Consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer’s disease

- DS

Down syndrome

- DSM-IV

Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders–IV

- HB-EGF

Heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor

- HE

Hematoxylin-eosin

- IgG

Immunoglobulin G

- NRDc

Nardilysin (N-arginine dibasic convertase)

- PAP

Peroxidase-antiperoxidase

- PBS

Phosphate buffered saline

- p42IP4

Phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)P3/D-Inositol(1,3,4,5)P4-binding protein

- TNF-α

Tumour-necrosis factor-α

- TACE

Tumor necrosis factor-α-converting enzyme

References

- Aggensteiner M, Stricker R, Reiser G (1998) Identification of rat brain p42IP4, a high-affinity inositol(1,3,4,5)tetrakisphosphate/ phosphatidylinositol(3,4,5)trisphosphate binding protein. Biochim Biophys Acta 1387:117–128 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Arvidsson U, Riedl M, Elde R et al (1997) Vesicular acetylcholine transporter (VAChT) protein: a novel and unique marker for cholinergic neurons in the central and peripheral nervous systems. J Comp Neurol 378:454–467. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19970224)378:4<454::AID-CNE2>3.0.CO;2-1 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bandyopadhyay S, Goldstein LE, Lahiri DK et al (2007) Role of the APP non-amyloidogenic signaling pathway and targeting alpha-secretase as an alternative drug target for treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Med Chem 14:2848–2864. doi:10.2174/092986707782360060 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bataille D, Fontés G, Costes S et al (2006) The glucagon-miniglucagon interplay: a new level in the metabolic regulation. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1070:161–166. doi:10.1196/annals.1317.005 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Beal MF, Kowall NW, Mazurek MF (1987) Neuropeptides in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neural Transm Suppl 24:163–174 [PubMed]

- Bell KF, Zheng L, Fahrenholz F et al (2008) ADAM-10 over-expression increases cortical synaptogenesis. Neurobiol Aging 29:554–565. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bernstein HG, Schon E, Ansorge S, Rose I, Dorn A (1987) Immunolocalization of dipeptidyl aminopeptidase (DAP IV) in the developing human brain. Int J Dev Neurosci 5:237–242 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bernstein HG, Kirschke H, Wiederanders B et al (1996) The possible place of cathepsins and cystatins in the puzzle of Alzheimer disease: a review. Mol Chem Neuropathol 27:225–247 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bernstein HG, Stanarius A, Baumann B et al (1998) Nitric oxide synthase-containing neurons in the human hypothalamus: reduced number of immunoreactive cells in the paraventricular nucleus of depressive patients and schizophrenics. Neuroscience 83:867–875. doi:10.1016/S0306-4522(97)00461-2 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bernstein HG, Baumann B, Danos P et al (1999) Regional and cellular distribution of neural visinin-like protein immunoreactivities (VILIP-1 and VILIP-3) in human brain. J Neurocytol 28:655–662. doi:10.1023/A:1007056731551 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bernstein HG, Bukowska A, Krell D et al (2003) Comparative localization of ADAMs 10 and 15 in human cerebral cortex normal aging, Alzheimer disease and Down syndrome. J Neurocytol 32:153–160. doi:10.1023/B:NEUR.0000005600.61844.a6 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bernstein HG, Stricker R, Dobrowolny H et al (2007) Histochemical evidence for wide expression of the metalloendopeptidase nardilysin in human brain neurons. Neuroscience 146:1513–1523. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.02.057 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Braunewell K, Riederer P, Spilker C et al (2001) Abnormal localization of two neuronal calcium sensor proteins, visinin-like proteins (vilips)-1 and -3, in neocortical brain areas of Alzheimer disease patients. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 12:110–116. doi:10.1159/000051244 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bubber P, Haroutunian V, Fisch G et al (2005) Mitochondrial abnormalities in Alzheimer brain: mechanistic implications. Ann Neurol 57:695–703. doi:10.1002/ana.20474 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cataldo F, Scola L, Piccione M et al (2005) Evaluation of cytokine polymorphisms (TNFalpha, IFNgamma and IL-10) in Down patients with coeliac disease. Dig Liver Dis 37:923–927. doi:10.1016/j.dld.2005.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chesneau V, Pierotti AR, Barre N et al (1994) Isolation and characterization of a dibasic selective metalloendopeptidase from rat testes that cleaves at the amino terminus of arginine residues. J Biol Chem 269:2056–2061 [PubMed]

- Chow KM, Oakley O, Goodman J et al (2003) Nardilysin cleaves peptides at monobasic sites. Biochemistry 42:2239–2244. doi:10.1021/bi027178d [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chow KM, Ma Z, Cai J et al (2005) Nardilysin facilitates complex formation between mitochondrial malate dehydrogenase and citrate synthase. Biochim Biophys Acta 1723:292–301 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Csuhai E, Chen G, Hersh LB (1998) Regulation of N-arginine dibasic convertase activity by amines: putative role of a novel acidic domain as an amine binding site. Biochemistry 37:3787–3794. doi:10.1021/bi971969b [DOI] [PubMed]

- Deuss M, Reiss K, Hartmann D (2008) Part-time alpha-secretases: the functional biology of ADAM 9, 10 and 17. Curr Alzheimer Res 5:187–201. doi:10.2174/156720508783954686 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Dournaud P, Delaere P, Hauw JJ et al (1995) Differential correlation between neurochemical deficits, neuropathology, and cognitive status in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 16:817–823. doi:10.1016/0197-4580(95)00086-T [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fahrenholz F (2007) Alpha-secretase as a therapeutic target. Curr Alzheimer Res 4:412–417. doi:10.2174/156720507781788837 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hiraoka Y, Ohno M, Yoshida K et al (2007) Enhancement of alpha-secretase cleavage of amyloid precursor protein by a metalloendopeptidase nardilysin. J Neurochem 102:1595–1605. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04685.x [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hiraoka Y, Yoshida K, Ohno M et al (2008) Ectodomain shedding of TNF-alpha is enhanced by nardilysin via activation of ADAM proteases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 370:154–158. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.03.050 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hooper NM (1994) Families of zinc metalloproteases. FEBS Lett 354:1–6. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(94)01079-X [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hospital V, Chesneau V, Balogh A et al (2000) N-arginine dibasic convertase (nardilysin) isoforms are soluble dibasic-specific metalloendopeptidases that localize in the cytoplasm and at the cell surface. Biochem J 349:587–597. doi:10.1042/0264-6021:3490587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jin K, Mao XO, Sun Y et al (2002) Heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor: hypoxia-inducible expression in vitro and stimulation of neurogenesis in vitro and in vivo. J Neurosci 22:5365–5373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jin K, Peel AL, Mao XO et al (2004) Increased hippocampal neurogenesis in Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:343–347. doi:10.1073/pnas.2634794100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kieseier BC, Pischel H, Neuen-Jacob E et al (2003) ADAM-10 and ADAM-17 in the inflamed human CNS. Glia 42:398–405. doi:10.1002/glia.10226 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lott IT, Head E, Doran E et al (2006) Beta-amyloid, oxidative stress and down syndrome. Curr Alzheimer Res 3:521–528. doi:10.2174/156720506779025305 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Maes OC, Xu S, Yu B et al (2007) Transcriptional profiling of Alzheimer blood mononuclear cells by microarray. Neurobiol Aging 28:1795–1809. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Marcinkiewicz M, Seidah NG (2000) Coordinated expression of beta-amyloid precursor protein and the putative beta-secretase BACE and alpha-secretase ADAM10 in mouse and human brain. J Neurochem 75:2133–2143. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0752133.x [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mouradian MM, Blin J, Giuffra M et al (1991) Somatostatin replacement therapy for Alzheimer dementia. Ann Neurol 30:610–613. doi:10.1002/ana.410300415 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Murphy M, Friend DS, Pike-Nobile L et al (1992a) Tumor necrosis factor-alpha and IFN-gamma expression in human thymus. Localization and overexpression in Down syndrome (trisomy 21). J Immunol 149:2506–2512 [PubMed]

- Murphy M, Hyun W, Hunte B et al (1992b) A role for tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interferon-gamma in the regulation of interleukin-4-induced human thymocyte proliferation in vitro. Heightened sensitivity in the Down syndrome (trisomy 21) thymus. Pediatr Res 32:269–276. doi:10.1203/00006450-199209000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Murphy M, Insoft RM, Pike-Nobile L et al (1995) A hypothesis to explain the immune defects in Down syndrome. Prog Clin Biol Res 393:147–167 [PubMed]

- Nishi E, Prat A, Hospital V et al (2001) N-arginine dibasic convertase is a specific receptor for heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor that mediates cell migration. EMBO J 20:3342–3350. doi:10.1093/emboj/20.13.3342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nishi E, Hiraoka Y, Yoshida K et al (2006) Nardilysin enhances ectodomain shedding of heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor through activation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha-converting enzyme. J Biol Chem 281:31164–31172. doi:10.1074/jbc.M601316200 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nistor M, Don M, Parekh M et al (2007) Alpha- and beta-secretase activity as a function of age and beta-amyloid in Down syndrome and normal brain. Neurobiol Aging 28:1493–1506. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.06.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pierotti AR, Prat A, Chesneau V et al (1994) N-arginine dibasic convertase, a metalloendopeptidase as a prototype of a class of processing enzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91:6078–6082. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.13.6078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rawlings ND, Barrett AJ (1993) Evolutionary families of peptidases. Biochem J 290:205–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Reiser G, Bernstein HG (2002) Neurons and plaques of Alzheimer’s disease patients highly express the neuronal membrane docking protein p42IP4/centaurin α. Neuroreport 13:2417–2419. doi:10.1097/00001756-200212200-00008 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Reiser G, Bernstein HG (2004) Altered expression of protein p42IP4/centaurin-α1 in Alzheimer’s disease brains and possible interaction of p42IP4 with nucleolin. Neuroreport 15:147–148. doi:10.1097/00001756-200401190-00028 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rossor MN, Iversen LL, Reynolds GP et al (1984) Neurochemical characteristics of early and late onset types of Alzheimer’s disease. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 288:961–964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Selemon LD, Mrzljak J, Kleinman JE et al (2003) Regional specificity in the neuropathologic substrates of schizophrenia: a morphometric analysis of Broca’s area 44 and area 9. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60:69–77 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Skovronsky DM, Fath S, Lee VM et al (2001) Neuronal localization of the TNFalpha converting enzyme (TACE) in brain tissue and its correlation to amyloid plaques. J Neurobiol 49:40–46. doi:10.1002/neu.1064 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Skovronsky DM, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ (2006) Neurodegenerative diseases: new concepts of pathogenesis and their therapeutic implications. Annu Rev Pathol 1:151–170. doi:10.1146/annurev.pathol.1.110304.100113 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Spiechowicz M, Bernstein HG, Dobrowolny H et al (2006) Density of Sgt1-immunopositive neurons is decreased in the cerebral cortex of Alzheimer’s disease brain. Neurochem Int 49:487–493. doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2006.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Stricker R, Hülser E, Fischer J et al (1997) cDNA cloning of porcine p42IP4, a membrane-associated and cytosolic 42 kDa inositol(1,3,4,5)tetrakisphosphate receptor from pig brain with similarly high affinity for phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)P3. FEBS Lett 405:229–236. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(97)00188-9 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Stricker R, Chow KM, Walther D et al (2006) Interaction of the brain-specific protein p42IP4/centaurin-α1 with the peptidase nardilysin is regulated by the cognate ligands of p42IP4, PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and Ins(1,3,4,5)P4, with stereospecificity. J Neurochem 98:343–354. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03869.x [DOI] [PubMed]

- Winsky-Sommerer R, Grouselle D, Rougeot C et al (2003) The proprotein convertase PC2 is involved in the maturation of prosomatostatin to somatostatin-14 but not in the somatostatin deficit in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience 122:437–447. doi:10.1016/S0306-4522(03)00560-8 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yakovleva T, Marinova Z, Kuzmin A et al (2007) Dysregulation of dynorphins in Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol Aging 28:1700–1708. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yang P, Baker KA, Hagg T (2006) The ADAMs family: coordinators of nervous system development, plasticity and repair. Prog Neurobiol 79:73–94. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yang HQ, Pan J, Ba MW et al (2007) New protein kinase C activator regulates amyloid precursor protein processing in vitro by increasing alpha-secretase activity. Eur J Neurosci 26:381–391. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05648.x [DOI] [PubMed]