Abstract

Anandamide (AEA) and 2-arachidonyl glycerol (2-AG), endogenous ligands for the CB1 and CB2 cannabinoid receptors, are referred to as endocannabinoids because they mimic the actions of delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC), a plant-derived cannabinoid. The processes by which AEA and 2-AG are biosynthesized, released, taken up by cells and hydrolyzed have been of much interest as potential therapeutic targets. In this review we will discuss the progress that has been made to characterize the primary pathways for AEA and 2-AG formation and breakdown as well as the role that specialized membrane microdomains known as lipid rafts play in these processes. Furthermore we will review the recent advances made to track and detect AEA in biological matrices.

A list of key words: Cannabinoid, Anandamide, 2-Arachidonoyl glycerol, Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol, Membrane Microdomain

Introduction

Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC) is the primary psychoactive ingredient of marijuana, a plant-derived cannabinoid (Childers and Breivogel, 1998). Δ9-THC produces a range of pharmacological effects in the central nervous system and in the periphery. Currently Δ9-THC and its analogs are being used as anti-emetic agents in the treatment of nausea and vomiting induced by radio- or chemotherapy and severe anorexia (wasting syndrome) in patients with AIDS. Furthermore, Δ9-THC may also be useful for the treatment of glaucoma, spasticity, and pain, however, the beneficial therapeutic effects of Δ9-THC are hampered by the psychotropic side effects of euphoria elicited by plant-derived cannabinoids (Watson et al., 2000). Therefore, a drug target system has to be exploited that will produce the positive therapeutic effects of Δ9-THC without the undesirable side effects.

The pharmacologic properties of both plant-derived cannabinoids and endogenous cannabinoids (endocannabinoids) are similar. Since the discovery of endocannabinoids in the early 1990s, the actions of these substances have been rigorously studied. Endocannabinoids as well as Δ9-THC mediate their effects primarily via the G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) type 1 cannabinoid (CB1) and type 2 cannabinoid (CB2) (Matsuda et al., 1990; Munro et al., 1993). Additionally, two orphan G-protein coupled non-CB1/CB2 receptors have been implicated to be a part of the endocannabinoid family, GPR55 and GPR119 (Brown, 2007). Anandamide (AEA) has also been shown to have agonist activity at the vanilloid receptor (VR1) that is a member of the transient receptor potential (TRP) superfamily of ion channels (Smart et al., 2000; Zygmunt et al., 1999).

AEA and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) are the most studied members of the endocannabinoid family, although multiple pathways for endocannabinoid synthesis have been described, the prevalent pathway for in vivo biosynthesis has yet to be determined (Liu et al., 2006; Okamoto et al., 2004; Simon and Cravatt, 2006; Simon and Cravatt, 2008). The diversity of the signaling pathways in which AEA, 2-AG and other endocannabinoids partake, implies the significant roles that these molecules play in various physiological conditions. For example, endocannabinoids have been linked to retrograde signaling in various regions of the brain (Chevaleyre et al., 2006). Once released from the postsynaptic neuron, the endocannabinoid molecule travels in a retrograde fashion to transiently suppress the presynaptic neurotransmitter release through activation of the target cannabinoid receptors (Chevaleyre et al., 2006). Retrograde signaling modulated by endocannabinoids is critical for certain types of short-term and long-term synaptic plasticity at excitatory or inhibitory synapses and contributes to certain aspects of brain function including learning and memory (reviewed in Hashimotodani et al., 2007). CB1 receptor-knockout mice have been shown to exhibit behavioral abnormalities and multiple defects in synaptic plasticity, supporting the notion that endocannabinoid signaling is involved in neural function (Kishimoto and Kano, 2006; Steiner et al., 1999). The endocannabinoid system has also been linked to a variety of neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders such as anxiety, prolonged stress, depression, psychosis, Alzeimer’s, Parkinson’s, and Huntington’s Chorea disorders (reviewed in Bisogno and Di Marzo, 2007). Additionally, endocannabinoid signaling has been implicated in several physiological processes such as pain, nausea, reproduction, immune response, and cancer, indicating the diversity of biological targets that endocannabinoids modulate (Di Carlo and Izzo, 2003; Guzmán, 2003; Habayeb et al., 2002; Karsak et al., 2007; Parolaro et al., 2002; Pertwee, 2001; Tramèr et al., 2001). Characterization and pharmacologic manipulation of the endocannabinoid system is important because it may allow us to identify new drug targets and develop therapeutics for the treatment of many disorders without the undesirable side effects that plant-derived cannabinoids produce.

Biosynthesis of Endocannabinoids

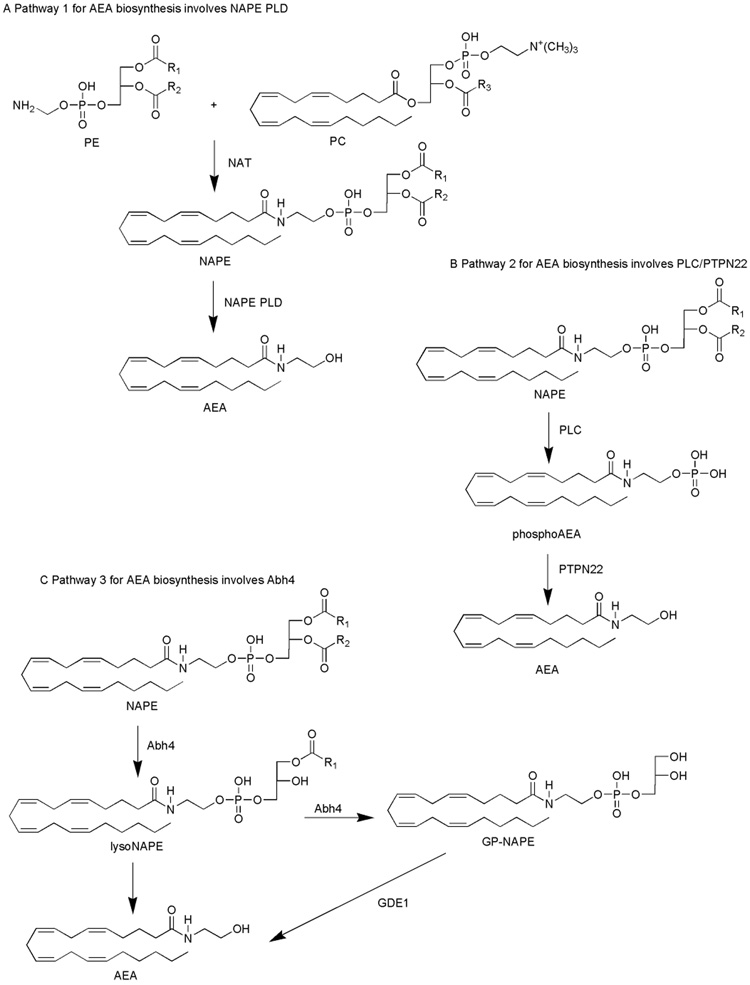

Unlike the typical neurotransmitter molecules that are stored in and recycled into vesicles, endocannabinoids are synthesized and released “on demand.” The processes that underlie the biosynthesis of endocannabinoids have been extensively studied for 2-AG and AEA. It is believed that 2-AG and AEA as well as their congeners are stored in the membrane as phospholipid precursors (Piomelli, 2003). The endocannabinoid 2-AG is synthesized from diacylglycerol (DAG) via the actions of sn1-specific DAG lipase in a calcium-dependent fashion (Bisogno et al., 2003), although PLC-independent mechanisms for 2-AG formation have also been suggested (Bisogno et al., 1999; Carrier et al., 2004). AEA is generally believed to be synthesized from a precursor, N-arachidonyl phosphatidylethanolamine (NAPE) in a calcium-dependent fashion by an enzyme NAPE phospholipase D (NAPE PLD) (Di Marzo et al., 1994; Okamoto et al., 2004). However, calcium-independent AEA biosynthesis has been described as well (Vellani et al., 2008). Two additional pathways have been suggested for the biosynthesis of AEA, and these mechanisms appear to be cell-type specific: formation of phosphoAEA by phospholipase C (PLC) and subsequent dephosphorylation of phosphoAEA by the protein tyrosine phosphatase 22, PTPN22; and α/β hydrolase 4 (Abh4)-dependent NAPE hydrolysis followed by a phosphodiesterase cleavage step modulated by glycerophosphodiesterase 1 (GDE1).

Pathway 1 for AEA biosynthesis involves NAPE PLD

N-acyl ethanolamine (NAE) synthesis has been suggested to take place in two sequential steps (Fig. 1A). The first reaction, also considered to be the rate-limiting step, involves the transfer of a fatty acyl chain from the sn-1 position of a glycerolipid to phosphatidylethanolamine in a calcium-dependent fashion by an N-acyl transferase (NAT), yielding NAPE (Okamoto et al., 2007). Unsuccessful attempts have been made to clone NAT, however, Jin and colleagues (2007) discovered an enzyme that is capable of functioning as an N-acyl transferase, and called it lecithin-retinol acyltransferase-like protein (RLP-1) (Jin et al., 2007). The reaction catalyzed by RLP-1 yielded NAPE when phosphatidylcholine (PC) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) were used as substrates (Jin et al., 2007). RLP-1, however, did not show selectivity between sn-1 and sn-2 positions of the acyl donor, was only modestly activated by calcium, and was predominantly expressed in the cytosolic fraction of the cell (Jin et al., 2007). NAT partially purified from brain tissue was specific for the sn-1 acyl group, highly calcium-dependent, and localized to the membrane fraction of the cell (Jin et al., 2007). Therefore, RLP-1 may function as a transferase in the process of AEA biosynthesis in the testis where RLP-1 is predominantly expressed, however a different NAT may be involved in the biosynthesis of AEA in the brain.

Figure 1. A schematic representation of the putative pathways implicated in the biosynthesis of AEA.

The pathways are: NAPE PLD-modulated NAPE hydrolysis to yield AEA (A); PLC-modulated cleavage of NAPE, formation of a phosphoAEA intermediate and subsequent dephosphorylation by PTPN22 (B); Abh4-dependent NAPE hydrolysis to yield AEA (C).

The second reaction in the formation of AEA is catalyzed by a calcium-dependent NAPE PLD and results in the formation of the NAE specific to its precursor. Okamoto and colleagues (2004) cloned a phospholipase D that specifically biosynthesized NAEs, including AEA (Okamoto et al., 2004). The involvement of NAPE PLD in the process of AEA biosynthesis remains unclear because the levels of polyunsaturated NAEs, including AEA remained unchanged in the brains of NAPE PLD knock-out mice (Leung et al., 2006). Also, the regional distribution of NAPE PLD does not always correlate with the distribution of the CB1 receptor and fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH), an enzyme that metabolizes AEA. NAPE PLD has been found to be highly expressed in the thalamus, the dentate gyrus, the cortex and the hippocampus, whereas the CB1 receptor and FAAH are predominantly expressed in the hippocampus, cortex, and cerebellum (Cristino et al., 2008; Egertová et al., 1998; Egertová et al., 2008; Morishita et al., 2005; Nyilas et al., 2008; Suarez et al., 2008). It appears that NAPE PLD may catalyze AEA formation in vitro, but additional enzymatic routes may prevail in vivo.

In addition, a lysoPLD enzyme, distinct from NAPE PLD, can utilize N-arachidonyl-lyso phosphatidylethanolamine as an active substrate for AEA formation (Sun et al., 2004). The involvement of lysoPLD in the processes of AEA biosynthesis in vivo remains unclear.

Pathway 2 for AEA biosynthesis involves PLC/PTPN22

An alternative route for AEA formation in mouse brain and RAW264.7 macrophages has been proposed to involve phospholipase C (PLC)-modulated hydrolysis of NAPE to generate a phosphoAEA intermediate, independent of NAPE PLD (Fig. 1B) (Liu et al., 2006). Treatment of RAW 264.7 macrophages with bacterial endotoxin lipopolysaccharide (LPS) upregulated the expression levels of a protein tyrosine phosphatase, PTPN22, which then dephosphorylated the phosphoAEA (Liu et al., 2006). Interestingly, the authors determined that treatment of RAW 264.7 macrophages with LPS caused a dramatic decrease in NAPE PLD gene expression, suggesting that AEA formation in this system does not involve NAPE PLD (Liu et al., 2006). The involvement of PTPN22 in the biosynthesis of AEA remains ambiguous because other phosphatases may be involved in the dephosphorylation of phosphoAEA as well.

Pathway 3 for AEA biosynthesis involves Abh4

An additional possible mechanism for the biosynthesis of AEA implicates double-deacylation of NAPE catalyzed by a serine hydrolase to form a glycerophospho-NAPE (GP-NAPE) molecule (Fig. 1C) (Simon and Cravatt, 2006). A new candidate for the selective hydrolysis of NAPE and lysoNAPE has been proposed to be the enzyme Abh4, a lysoNAPE lipase, isolated and identified by Simon and Cravatt (Simon and Cravatt, 2006). Activity-based proteomic analysis in concert with conventional protein chromatography characterized Abh4 as a B-type NAPE lipase that removes both O-acyl chains from NAPE to yield GP-NAE (Simon and Cravatt, 2006). Abh4 has been implicated in the catalysis of both O-deacylation steps in the generation of the GP-NAE intermediate (Simon and Cravatt, 2006). Overall, Abh4 possesses characteristics expected of an enzyme involved in the biosynthesis of AEA: expression in the CNS and testes, selectivity for NAPEs with distinct N-acyl chains, and preference for lysoNAPEs over other lysolipids (Simon and Cravatt, 2006). Once the GP-NAE intermediate is formed, a phosphodiesterase-modulated cleavage of the GP-NAE molecule takes place to generate a free NAE molecule and a glycerol-3-phosphate (Simon and Cravatt, 2006). Recently, Simon and Cravatt determined the identity of the enzyme that has robust GP-NAE phosphodiesterase activity--glycerophosphodiesterase GDE1, also known as MIR16 (Simon and Cravatt, 2008). The multistep pathway for the production of anandamide in the nervous system by the sequential actions of Abh4 and GDE1 may, in fact, turn out to be the prevalent pathway for AEA synthesis in vivo. In the future, genetic and pharmacologic approaches should be used to further characterize the roles of Abh4 and GDE1 in the biosynthesis of AEA.

The dopamingergic, cholinergic, and glutamatergic systems have also been implied in the biosynthesis of endocannabinoids. In 1999, Giuffrida and colleagues reported that the release of AEA was significantly increased after administration of D2-like dopamine receptor agonist quinpirole in the dorsal striatum (Giuffrida et al., 1999). Activation of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors with carbachol has been shown to trigger endocannabinoid synthesis and release in the hippocampus (Kim et al., 2002). Additionally, Varma and colleagues (2001) reported that the activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors in pyramidal cells may drive the release of endocannabinoids (Varma et al., 2001). Activation of both muscarinic acetylcholine and metabotropic glutamate receptors resulted in increases in depolarization-induced suppression of inhibition, confirming the role of endocannabinoids in retrograde signaling (Kim et al., 2002; Varma et.al., 2001). In the future, the specific mechanisms that underlie endocannabinoid biosynthesis in response to activation of the dopaminergic, cholinergic and glutamatergic systems should be elucidated.

The role of lipid rafts in the biosynthesis of endocannabinoids

Whereas several pathways involved with endocannabinoid biosynthesis have been described, the involvement of specialized membrane microdomains in endocannabinoid production has been proposed. The specialized microdomains within the plasma membrane that are enriched in cholesterol, sphingolipids, plasmenyethanolamine, and arachidonic acid are referred to as lipid rafts (Brown and London, 2000; Pike et al., 2002). Caveolae are characterized by a similar lipid composition as lipid rafts and express a group of structural proteins known as caveolins that promote flask-shaped invaginations in the plasma membrane (Pike et al., 2002; Razani et al., 2002).

Lipid rafts and caveolae serve as important platforms for regulation of a variety of processes linked to the endocannabinoid system (McFarland and Barker, 2005). In particular, lipid rafts/caveolae have been implicated in the modulation of the CB1 receptor binding and signaling (Bari et al., 2005). Treatment of C6 glioma cells with methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MCD), an agent that sequesters cholesterol and disrupts lipid rafts, results in an enhanced binding response of the CB1 receptor agonist CP 55940 to CB1 receptors and subsequent increase in G protein-mediated signaling through adenylate cyclase and MAPK (Bari et al., 2005). The role of lipid rafts/caveolae has also been established in the modulation of AEA uptake (McFarland et al., 2008; McFarland et al., 2004). The pharmacologic disruption of the lipid raft microorganization results in an attenuation of AEA uptake (McFarland et al., 2008; McFarland et al., 2004). These and other data suggest that lipid raft/caveolae organization may be critical in the process of AEA uptake. Furthermore, the AEA metabolites arachidonic acid (AA) and ethanolamine become enriched in the lipid raft portion of the cell (McFarland et al., 2004). These metabolites, AA and ethanolamine, can then be utilized by the cell for recycling, synthesis, and release of new AEA molecules (McFarland et al., 2006). In other words, the phenomenon of recycling implies that intact AEA molecules are taken up by the cell, metabolized into AA and ethanolamine, and then these metabolites are efficiently re-used by the cell to form new intact AEA molecules.

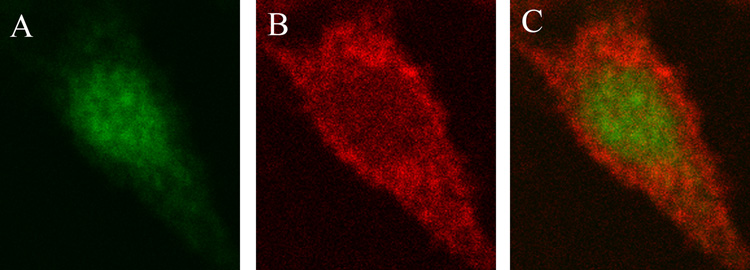

The mechanism by which the biosynthesis of AEA is modulated within the lipid rafts remains unknown. Wettschureck and colleagues (2006) determined that endocannabinoid biosynthesis was impaired in the absence of Gq/G11, G proteins that modulate various signaling events via lipid raft-dependent mechanisms (Sugawara et al., 2007; Wettschureck et al., 2006). Furthermore, we established that the cloned NAPE PLD may not be involved in the synthesis and release of AEA from the lipid rafts in RBL-2H3 cells because immunocytochemistry studies showed no overlap in the localization between NAPE PLD and flotillin-1, a marker for lipid rafts (Fig. 2). Therefore, other pathways may be involved in the biosynthesis of AEA in the lipid raft microdomains in RBL-2H3 cells. Rimmerman and colleagues (2008) reported that NAPE PLD was distributed among both the lipid raft and non-lipid raft fractions of the DRG X neuroblastoma F-11 cell line (Rimmerman et al., 2008). The finding that NAPE PLD did not localize with lipid raft markers in the cognate mast RBL-2H3 cells, and only a fraction of NAPE PLD localized to the lipid rafts in the neuroblastoma F-11 cell line may indicate that NAPE PLD has different distribution patterns that depend on the origin of the cell line. Rimmerman et. al. also discovered that the distribution of NAPE PLD and endogenous AEA was similar--in both lipid raft and non-lipid raft fractions (Rimmerman et al., 2008). The authors attributed the phenomenon of the similar distribution patterns of AEA and NAPE PLD to increased production of AEA in compartments that contain higher levels of the AEA synthetic enzyme (Rimmerman et al., 2008). It has not been established, however, that NAPE PLD is responsible for the formation of AEA in the F-11 cells. In fact, many studies report that NAPE PLD may not be involved in the biosynthesis of AEA in vivo (Leung et al., 2006; Simon and Cravatt, 2008).

Figure 2. NAPE PLD and flotillin-1 did not co-localize in RBL-2H3 cells.

Confocal microscopy analysis of RBL-2H3 cells revealed the presence of (A) NAPE PLD localization (green; primary anti-NAPE PLD polyclonal antibody: 1:1000, secondary Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody: 1:2000) and (B) flotillin-1 localization in the lipid raft microdomains (red; primary anti-flotillin-1 monoclonal antibody: 1:100, secondary Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody: 1:1000). The overlay of the red and green signal (C) revealed that the two proteins, NAPE PLD and flotillin-1 did not overlap in their cellular locations. The cell images were acquired by oil immersion confocal microscopy at × 60 magnification with a Nikon Diaphot 300 microscope. The Bio-Rad MRC1024 confocal system was used with a krypton (488 nm)/argon (568 nm) laser, a 522–535-nm band-pass filter, and a 588-nm long-pass filter. Data are representative of three separate experiments.

The deuterated AA derived from exogenously-applied deuterated AEA co-localized mostly with non-lipid raft fractions (Rimmerman et al., 2008). In these experiments, Rimmerman and colleagues only determined the population of free AA molecules, and AA that had been re-esterified and incorporated into phospholipids or other fatty acid metabolites was not taken into account. In prior studies, McFarland and colleagues did not discriminate between the populations of free AA and its metabolites and observed an enrichment of tritium derived from AEA in the lipid raft fractions (McFarland et al., 2004). Examining the localization of free AA derived from AEA may be insufficient because most of the AA derived from AEA metabolism may be re-esterified into AA-containing lipids that have been trafficked to the membrane.

The biochemical machinery for the production of 2-AG is localized within lipid rafts suggesting that 2-AG synthesis via DAG occurs within these microdomains (Rimmerman et al., 2008). The finding that 2-AG and the synthetic machinery for the production of 2-AG, DAG lipase, were localized to the lipid raft portion of the cell is consistent with the results obtained in our lab. We discovered that exogenously applied AEA may be recycled by the RBL-2H3 cells to form not only new AEA molecules (as noted above), but also new 2-AG molecules (McFarland et al., 2006).

Cannabimimetic substances, related lipids, and novel cannabinoid targets

Besides AEA and 2-AG, other members of the endocannabinoid family have been discovered. Molecules such as N-arachidonyl dopamine (NADA), noladin ether (also called 2-arachidonl glycerol ether), oleamide, and virodhamine display affinity for the cannabinoid receptors, but have been studied much less in comparison to AEA and 2-AG (Hanus et al., 2001; Huang et al., 2002; Leggett et al., 2004; Porter et al., 2002).

There are also several examples in which the observed pharmacology is not consistent with the signaling of the classical cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptors. Other lipid mediators, despite the fact that they show no appreciable affinity for the CB1/CB2 cannabinoids receptors, display cannabimimetic effects and modulate pain, immune function, reproduction, and appetite (Tan et al., 2006). For example, oleoylethanolamide (OEA) and palmitoylethanolamide (PEA), two naturally occurring acylethanolamides lack affinity for the cannabinoid CB1/CB2 receptors, and yet evoke effects consistent with cannabinoid pharmacology, such as stimulation of food intake and pain modulation, respectively (Lambert and Di Marzo, 1999; Lambert et al., 1999; Rodríguez de Fonseca et al., 2001). Accordingly, there has been a significant effort to discover the novel target(s) for cannabinoid ligands. Studies using genetic ablation of the CB1 and/or CB2 receptors in mice have confirmed the existence of additional non-CB1/CB2 receptor targets (reviewed in Brown, 2007). These targets include GPR119 and GPR55, orphan GPCRs that have been proposed to be novel receptors for fatty acid amides and endocannabinoids such as OEA and PEA, respectively (Fu et al., 2005; Lo Verme et al., 2005; Mackie and Stella, 2006; Overton et al., 2006). OEA endogenously targets GPR119 and PEA may activate GPR55 in addition to other targets, such as peroxisome proliferators activated receptors (PPARs) (Fu et al., 2005; Lo Verme et al., 2005; Mackie and Stella, 2006; Overton et al., 2006). However, further studies elucidating whether the GPR119 receptor is a true cannabinoid receptor should be conducted because OEA is not classified as a classical endocannabinoid.

Endocannabinoid lipidomics and mass spectrometry

The various endocannabinoids and related lipid mediators may function via overlapping signaling pathways and regulate the physiology of the classical cannabinoid system. In order to study the overlap between the signaling events that modulate the classical and the novel cannabinoid systems there is a need for accurate, precise, and timely detection approaches. Detection of the entire profile of endocannabinoid molecules produced in vivo is crucial for the characterization of the endocannabinoid system, and may allow us to identify other compounds that modulate the signaling of both the known endocannabinoids and the novel targets.

The sensitivity of endocannabinoid detection methods may limit the analysis of these lipids. Originally, various groups used thin layer chromatography (TLC) to detect endocannabinoid levels (Deutsch et al., 2001; Parrish and Nichols, 2006). The drawback of using the TLC method is that although the detection of AEA and 2-AG is achieved without difficulty, a profile of a range of endocannabinoids is not easily characterized and/or resolved. Detection of a variety of endocannabinoid molecules is necessary for the full characterization of the endocannabinoid system. In order to sufficiently characterize the signaling events that endocannabinoids modulate the entire endocannabinoid lipidome must be analyzed not just the two predominant species, AEA and 2-AG.

Advances in mass spectrometry (MS) allow for detection of many novel signaling lipids as well as simultaneous monitoring of the known members of the endocannabinoid family. For example, in 2002, Porter and colleagues identified a novel endocannabinoid, virodhamine, an AA molecule joined to ethanolamine by an ester linkage, in contrast to AEA that is joined by the amide linkage (Porter et al., 2002). Virodhamine displays affinity for the CB1 cannabinoid receptor and acts as a partial agonist that possesses in vivo antagonist activity, whereas at the CB2 receptor, virodhamine displays full agonist activity (Porter et al., 2002). Virodhamine was discovered unexpectedly when Porter and colleagues were measuring tissue levels of AEA using Liquid Chromatographic Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-APCI-MS-MS),and an analyte with a different retention time but the same molecular weight as AEA was detected (Porter et al., 2002). Therefore, mass spectrometry may prove to be better suited for the detection of endocannabinoids and other related compounds than previously existing methods.

A sensitive and selective method for quantitation and detection of endocannabinoids involves a single or multiple reaction monitoring (SRM or MRM) modes on a triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer (Kingsley and Marnett, 2003; Kinglsey and Marnett, 2007; Richardson et al., 2007). The sensitivity is achieved on the triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer through monitoring of a single fragment species from a single precursor ion, an approach that allows for elimination of unnecessary background noise. Recently, Richardson and colleagues reported a quantitative, validated LC-MS-MS method using a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer for simultaneous detection of AEA, 2-AG, six other endocannabinoid species, and additional related compounds (Richardson et al., 2007). The limit of detection for AEA, oleoyl ethanolamide, palmitoyl ethanolamide, 2-linoleoyl glycerol, and noladin ether was reported to be 10 pmol/g, and for 2-AG 100 pmol/g, proving the LC-MS-MS technique to be extremely sensitive and suitable for the detection of species within the endocannabinoid family (Richardson et al., 2007).

In a different study, Hardison and colleagues reported that precise and reproducible quantification of endocannabinoids can be achieved using purification with C18 solid-phase extraction prior to analysis with gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC-MS) (Hardison et al., 2006). The limit of quantification for AEA was found to be 20 pmol/g (Hardison et al., 2006). Thus, it appears that the LC-MS-MS approach allows for more sensitive quantification of AEA. Furthermore, the LC-MS-MS technique does not require sample derivatization prior to analysis, whereas the GC-MS approach does. Also, a quantitative profile of endogenous cannabinoids has not yet been characterized by GC-MS. Both approaches, LC-MS-MS and GC-MS, however permit for quantitative and reproducible detection of AEA and 2-AG.

The limit of detection for endocannabinoids may potentially be improved on the LC-MS-MS instruments by exploiting silver cation coordination to the arachidonate backbone of these eicosanoid-like molecules (Kingsley and Marnett, 2003). The π electrons in the double bonds within the arachidonate backbone of neutral molecules such as AEA and 2-AG provide binding sites for the silver cations, resulting in a [M+Ag]+ species that easily undergo conversion to the gas phase via an electrospray iononization (ESI) source. For example, Kingsley and Marnett reported a significant improvement in 2-AG detection as the [M+Ag]+ species resulted in a more intense signal than any fragment of the non-Ag+ species (Kingsley and Marnett, 2003). The authors reported that on average 13.4 nmol/g of 2-AG and 10.8 pmol/g of AEA were detected in mouse brain tissue, results consistent with previous reports (Kingsley and Marnett, 2003). The use of silver ion coordination facilitates SRM analysis for 2-AG. The ease of the analysis and specificity of the method make it ideal for endocannabinoid quantification in a range of experimental settings. In addition, the method should be readily adaptable to the analysis of other neutral lipids on other instruments including time-of-flight (TOF) mass spectrometers.

The recent advances in lipidomics and mass spectrometry analysis may allow for identification of novel endocannabinoids and related compounds that possess important biological signaling functions. Such approaches are critical to further our understanding of endocannabinoid biology. Recently, Williams and colleagues (2007) devised and validated a robust, selective, and sensitive LC-MS-MS method for analyzing a variety of endocannabinoid molecules in a biological matrix (Williams et al., 2007). The authors expanded the endocannabinoid metabolome to include six different core fatty acid molecules and their corresponding glyceride and ethanolamide derivatives that varied in size and degrees of saturation (Williams et al., 2007). In particular, the core fatty acid molecules were represented by arachidonic acid (20:4), docosahexaenoic (22:6), eicosapentaenoic (20:5), eicosenoic (20:1), oleic (18:1), and palmitic (16:0) acid species among others (Williams et al., 2007).

The structural diversity represented by the species analyzed posed two main challenges in the development of the method—the suitable chromatographic separation and the appropriate solvent system. First, the hydrophobic nature of C8 or C18 columns would have been inadequate to allow for proper separation of the endocannabinoid metabolites. Therefore, the authors used a cyano column, which was able to provide the system with sufficient resolution (Williams et al., 2007). Secondly, it was necessary to determine the proper conditions for a mobile phase that would be capable of allowing for positive ionization of the ethanolamide and glycerol derivatives to take place and negative ionization of the free acids under the APCI conditions (Williams et al., 2007). The best-suited solvent system for the resolution of the related, yet structurally diverse members of the endocannabinoid metabolome proved to be a 10 mM ammonium acetate aqueous solution (pH 7.3) and methanol as the organic phase (Williams et al., 2007). The method established by Williams and colleagues provides a way to simultaneously detect eight metabolites that possess different structures and ionization efficiencies, thus, doubling the number of endocannabinoids that can be quantified simultaneously (Williams et al., 2007). The validity of the method was confirmed when rat frontal cortex tissue was analyzed for the endocannabinoid content (Williams et al., 2007).

As our knowledge of the endocannabinoid lipidome grows, it is crucial to further develop detection approaches such as MS. The MS technology may allow us to gain insight not only into the content but also into the distribution of endocannabinoids within the membrane microdomains of the cell (Rimmerman et al., 2008). The ability to identify endocannabinoids, precursors, and corresponding metabolites in specific intracellular compartments using MS can provide new opportunities to identify pathways involved with biosynthesis and metabolism. The levels and distribution of and interplay among all the endocannabinoid family members under diverse physiological conditions may aid in the development of novel therapeutics in the treatment of pathological conditions in which endocannabinoids are involved.

Uptake of endocannabinoids

The process by which cells transport AEA is crucial to understanding the inactivation of endocannabinoids because in order to be metabolized, AEA must first be trafficked to the cellular compartments in which FAAH is located (Cravatt et al., 1996). Two known isoforms of FAAH have been discovered: FAAH-1, specific for NAEs, and FAAH-2, specific for primary fatty acid amide substrates (Wei et al., 2006). For the purpose of this review, we will only focus on the FAAH-1 isoform because it is specific for AEA hydrolysis and refer to this enzyme as FAAH throughout the article.

To date, the identity of the protein(s) involved in the uptake and transport of AEA is unknown. Prior to describing the current models of AEA uptake it should be noted that the processes of AEA uptake may be intimately linked with the processes of AEA release from the cell, indicating that the biosynthetic machinery involved in the uptake process may also play a major role in endocannabinoid release (Adermark and Lovinger, 2007; Hillard et al., 1997; Ligresti et al., 2004; Ronesi et al., 2004). The uptake of AEA, however, has been characterized as a rapid, saturable, temperature-dependent, ion gradient- and ATP-independent process that can be inhibited in a dose-dependent manner by AEA analogues or fatty acid amide derivatives (Beltramo et al., 1997; Bisogno et al., 1997; Di Marzo et al., 1994; McFarland and Barker, 2004). Based on the existing literature, there are four models of AEA uptake: 1) Carrier protein-mediated transport; 2) Facilitated FAAH-driven diffusion of AEA; 3) AEA sequestration in a saturable membrane compartment; 4) Caveolae-related endocytosis.

Pathway 1 for the uptake of AEA involves carrier protein-mediated transport

The characteristics of AEA uptake suggest a carrier-mediated process. AEA uptake is rapid (t1/2=2.5 min), temperature-dependent, saturable at 37°C, and selective (Di Marzo et al., 1994). Furthermore, Moore and colleagues identified a high-affinity, saturable anandamide transporter binding site using a potent, competitive small molecule inhibitor of anandamide transport and FAAH, LY2183240 (Alexander and Cravatt, 2006; Moore et al., 2005; Ortar et al., 2008). The model for carrier protein-mediated AEA uptake is consistent with other proposed models to describe transport for various lipophilic molecules (Kanai et al., 1995; Schaffer and Lodish, 1994).

Pathway 2 for the uptake of AEA involves facilitated FAAH-driven diffusion of AEA

The role of FAAH in the uptake of AEA has been widely investigated. Various studies have reported that FAAH operates to maintain an inward concentration gradient of AEA to facilitate its uptake into the cell, thus, acting as a saturable component of the system (Day et al., 2001; Glaser et al., 2003). Even though FAAH may facilitate the transport of AEA, FAAH is not required for AEA transport to take place (Day et al., 2001; Fegley et al., 2004; Ligresti et al., 2004). Studies performed in FAAH knockout mice have confirmed that AEA uptake appears to be modulated by both FAAH-dependent and FAAH-independent mechanisms (Ortega-Gutiérrez et al., 2004) as temperature-sensitive AEA uptake occurs in preparations from FAAH knockout mice (Fegley et al., 2004; Ligresti et al., 2004). Thus, FAAH-driven AEA uptake may be a process specific to the particular system being investigated.

Pathway 3 for the uptake of AEA involves the sequestration of AEA into a saturable membrane compartment

An intracellular compartment has been proposed to contain sequestered AEA, thus, resulting in two pools of AEA--free and sequestered (Hillard and Jarrahian, 2003). These intracellular compartments may act as reservoirs to contain AEA, and it is possible that compounds that inhibit intracellular AEA accumulation with no apparent activity to inhibit FAAH, may saturate these intracellular compartments and prevent AEA accumulation (Hillard and Jarrahian, 2003). This compartment, however, has yet to be identified by biochemical or analytical approaches.

Pathway 4 for the uptake of AEA involves caveolae-related endocytosis

Caveolae-related endocytosis is a process that has been associated with lipid rafts and takes place independent of clathrin-mediated endocytosis (Parton, 2003). Studies by our lab indicate that AEA uptake takes place via caveolae-related endocytosis (McFarland et al., 2008; McFarland et al., 2004). Both AEA uptake and caveolae-related endocytosis share the characteristics described above. Furthermore, caveolae-related endocytosis meets the characteristics of carrier protein-mediated transport, facilitated FAAH-driven diffusion of AEA, and AEA sequestration in a saturable membrane compartment. Thus, caveolae-related endocytosis appears to encompass the criteria of the other models for AEA uptake.

Breakdown of endocannabinoids

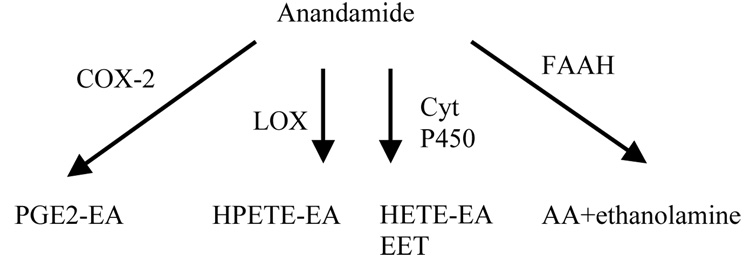

In order to terminate endocannabinoid signaling, these molecules first have to be transported into the cell. The pharmacologic profiles of AEA and 2-AG are similar, including the events that lead to uptake and signal termination of these endocannabinoids (Lambert and Fowler, 2005). Following uptake, AEA is hydrolyzed by FAAH into AA and ethanolamine (Fig. 3), whereas 2-AG may be hydrolyzed either by FAAH or a monoacylglycerol lipase (MGL) enzyme to yield AA and glycerol (Blankman et al., 2007; Cravatt and Lichtman, 2003; Deutsch and Chin, 1993; Di Marzo et al., 1998; Di Marzo and Maccarrone, 2008; Goparaju et al., 1998; Maccarrone et al., 2008; Muccioli et al., 2007). Experiments in tissue extracts indicate that potent FAAH inhibitors do not inhibit the hydrolysis of 2-AG suggesting that 2-AG inactivation may not utilize FAAH as a primary pathway for hydrolysis in vivo (Saario et al., 2004). Furthermore, observations in mice indicate that knockout of the FAAH gene does not affect 2-AG hydrolysis (Lichtman et al., 2002).

Figure 3. A schematic representation of the AEA hydrolysis pathways.

Anandamide can be metabolized by COX-2 to yield prostaglandin endoperoxide ethanolamide intermediates (PGE2-EA); by 12-LOX and 15-LOX to result in 12-hydroperoxy-5,8,10,14-eicosatetraenoylethanolamide and 15-hydroperoxy-5,8,11,13-eicosatetraenoylethanolamide (HPETE-EA) molecules; by cytochrome P450 into hydroxyeicosatetraenoic ethanolamide molecules (HETE-EA), such as 20-HETE-EA or epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) such as 5,6-, 8,9-, 11,12-, and 14,15-EET-EA; or by FAAH to convert AEA to AA and ethanolamine.

Additional pathways also exist for AEA breakdown as indicated by studies in which inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), not FAAH, prolonged anandamide-modulated depolarization-induced suppression of inhibition (DSI) (Kim and Alger, 2004). 12- and 15- lipoxygenases (LOX), that oxygenate esterified polyunsaturated fatty acids, are able to metabolize anandamide (Ueda et al., 1995). Cytochrome P450 also has been shown to metabolize AEA into hydroxyeicosatetraenoic ethanolamide (Snider et al., 2007).

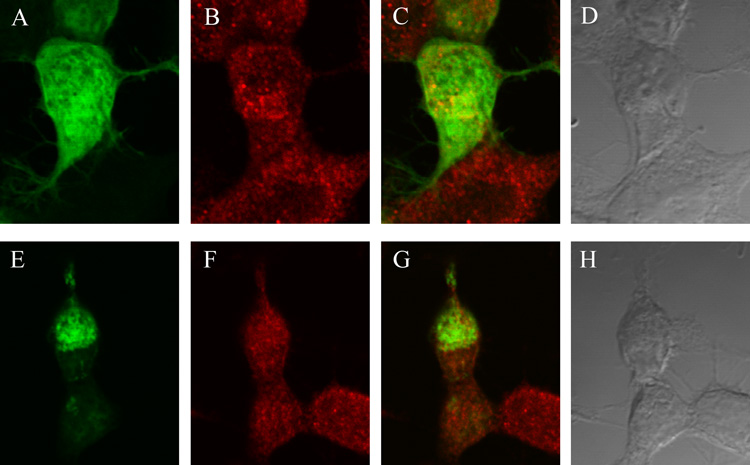

As mentioned above, the metabolites of AEA, AA and ethanolamine, are rapidly trafficked by the cell to the lipid raft region (McFarland et al., 2004). We hypothesized that NAPE PLD could be involved in the biosynthesis of AEA if it is localized in proximity to FAAH, a region of the cell where AA and ethanolamine are generated. In a study that was designed to determine the cellular location of FAAH in relation to NAPE PLD, we discovered that FAAH and green fluorescent protein (pEGFP)-tagged NAPE PLD expressed in neuronal-like CAD cells did not co-localize (Fig. 4). Therefore, we concluded that if NAPE PLD is involved in the biosynthesis of AEA in RBL-2H3 or CAD cells, this enzyme does not localize with known markers of lipid rafts or AEA metabolism—flotillin-1 and FAAH, respectively.

Figure 4. FAAH and GFP-NAPE PLD did not co-localize in CAD cells.

CAD cells were transfected with vector pEGFP-C1 (8 µg) (A–D) or (pEGFP-C1 NAPE PLD (8 µg) (E–H). A) pEGFP-C1 alone (green) revealed a diffuse signal. B) FAAH (red) localized in the perinuclear region of the cell (primary anti-FAAH polyclonal antibody: 1:500, secondary Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody: 1:1000). C) The overlay of the pEGFP-C1 (green) and FAAH (red) signal indicated that pEGFP-C1 did not localize with FAAH. D) bright-field image of the cells. E) pEGFP-C1 NAPE PLD (green) localized primarily in the nuclear area of the cell, consistent with localization in RBL-2H3 cells (Fig. 2). F) FAAH alone (red; primary anti-FAAH antibody: 1:500, secondary Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody: 1:1000). G) NAPE PLD (green) and FAAH (red) did not co-localize in CAD cells. H) Bright-field image of the cells. The cell images were acquired by oil immersion confocal microscopy at × 60 magnification with a Nikon Diaphot 300 microscope. The Bio-Rad MRC1024 confocal system was used with a krypton (488 nm)/argon (568 nm) laser, a 522–535-nm band-pass filter, and a 588-nm long-pass filter. Data are representative of three separate experiments.

Concluding remarks

Much progress has been made in recent years to characterize the processes that underlie biosynthesis, uptake, and metabolism of AEA and 2-AG. A better understanding of the mechanisms by which endocannabinoid biosynthesis and uptake take place and the role that lipid rafts play in these processes will be necessary to further characterize endocannabinoid pharmacology in terms of regulation of the immune response, pain, nausea, and cancer. This is why it is important to discover other members of the endocannabinoid family and investigate the impact of novel endocannabinoid signaling on the existing endocannabinoids. New advances in the field of mass spectrometry may allow us not only to detect and quantify the existing endocannabinoid levels in biological tissue, but also characterize the profile of related compounds.

Methods and Materials

Cell Culture

RBL-2H3 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 5% fetal clone I and 5% bovine calf serum supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. CAD cells were maintained in DMEM/F-12 (50/50) with 5% fetal clone I and 5% bovine calf serum supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were maintained in a CO2-containing (5%) humidified environment at 37°C.

Construction of the pEGFP-C1 NAPE PLD vector

A silent mutation removing the XbaI site in the NAPE PLD cDNA sequence was introduced at the position 364 from the beginning of the coding region. The sequence of pcDNA 3.1+ NAPE PLD (XbaI−) construct was verified by DNA sequencing. In order to generate pEGFP-C1 NAPE PLD construct, the pEGFP-C1 plasmid (Clonetech) and the pcDNA3.1+NAPE PLD (XbaI−) constructs were digested with XbaI and KpnI, and then the appropriate fragments were ligated together. This construct fused the pEGFP on the N-terminus of NAPE PLD, yielding pEGFP-C1 NAPE PLD.

Immunofluorescent localization of NAPE PLD and flotilin-1 in RBL-2H3 cells

RBL-2H3 cells were plated on coverslips in a 6-well plate that had been previously coated with poly-D-lysine. The next day, cells were fixed in a 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were then washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 15 min and twice for 5 min at room temperature. Next, cells were incubated in a permeabilization solution (5% fetal clone I, 5% bovine calf serum and 0.3 % Triton × 100) for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were washed again twice with PBS for 15 min and twice for 5 min. Primary antibodies directed against NAPE PLD (Cayman) and flotillin-1 (BD Biosciences) were prepared in PBS containing 5% fetal clone I and 5% bovine calf serum at dilutions of 1:1000 and 1:100, respectively, and incubated with the cells for 24 hours at 4°C. Cells were then washed with PBS five times for 5 min, and then the secondary antibodies were added, Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody at a dilution of 1:2000, and Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated goat-anti mouse antibody at a dilution of 1:1000. After incubation for 1 hour at room temperature, cells were washed five times with PBS. Coverslips were removed from the wells, mounted on slides using ProLong Antifade (Molecular Probes) and allowed to dry overnight. The cell images were acquired by oil immersion confocal microscopy at × 60 magnification with a Nikon Diaphot 300 microscope. The Bio-Rad MRC1024 confocal system was used with a krypton (488 nm)/argon (568 nm) laser, a 522–535-nm band-pass filter, and a 588-nm long-pass filter.

Immunofluorescent localization of NAPE PLD and FAAH in CAD cells

CAD cells were plated at 1.2 × 105 cells/well seeding density in a 6-well plate on coverslips, previously coated with poly-D-lysine. The cells were transfected with 8 µg of pEGFP-C1 NAPE PLD or 8 µg of pEGFP-C1 using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). The cells were cultured at 37 °C for 24 hours with one change of culture medium at 4 hours. Cells were incubated with the primary polyclonal antibody, anti-FAAH (1:500) in a PBS solution containing 5% fetal clone I and 5% bovine calf serum for 24 hours at 4°C. Cells were then washed with PBS five times for 5 min and incubated with the secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 568 (goat anti-rabbit, 1:1000) for 1 hour at room temperature. Cells were then washed five times with PBS, prepared and imaged as described above.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant R21 DA018112. We thank David Allen and Jennie Sturgis for help with image preparation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adermark L, Lovinger DM. Retrograde endocannabinoid signaling at striatal synapses requires a regulated postsynaptic release step. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20564–20569. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706873104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander JP, Cravatt BF. The putative endocannabinoid transport blocker LY2183240 is a potent inhibitor of FAAH and several other brain serine hydrolases. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:9699–9704. doi: 10.1021/ja062999h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bari M, Battista N, Fezza F, Finazzi-Agrò A, Maccarrone M. Lipid rafts control signaling of type-1 cannabinoid receptors in neuronal cells. Implications for anandamide-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:12212–12220. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411642200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beltramo M, Stella N, Calignano A, Lin SY, Makriyannis A, Piomelli D. Functional role of high-affinity anandamide transport, as revealed by selective inhibition. Science. 1997;277:1094–1097. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5329.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisogno T, Di Marzo V. Short- and long-term plasticity of the endocannabinoid system in neuropsychiatric and neurological disorders. Pharmacol Res. 2007;56:428–442. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisogno T, Howell F, Williams G, Minassi A, Cascio MG, Ligresti A, Matias I, Schiano-Moriello A, Paul P, Williams EJ, Gangadharan U, Hobbs C, Di Marzo V, Doherty P. Cloning of the first sn1-DAG lipases points to the spatial and temporal regulation of endocannabinoid signaling in the brain. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:463–468. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200305129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisogno T, Maurelli S, Melck D, De Petrocellis L, Di Marzo V. Biosynthesis, uptake, and degradation of anandamide and palmitoylethanolamide in leukocytes. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3315–3323. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.6.3315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisogno T, Melck D, De Petrocellis L, Di Marzo V. Phosphatidic acid as the biosynthetic precursor of the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol in intact mouse neuroblastoma cells stimulated with ionomycin. J Neurochem. 1999;72:2113–2119. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0722113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankman JL, Simon GM, Cravatt BF. A comprehensive profile of brain enzymes that hydrolyze the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol. Chem Biol. 2007;14:1347–1356. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AJ. Novel Cannabinoid Receptors. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2007;152:567. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DA, London E. Structure and function of sphingolipid- and cholesterol-rich membrane rafts. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:17221–17224. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R000005200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrier EJ, Kearn CS, Barkmeier AJ, Breese NM, Yang W, Nithipatikom K, Pfister SL, Campbell WB, Hillard CJ. Cultured rat microglial cells synthesize the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonylglycerol, which increases proliferation via a CB2 receptor-dependent mechanism. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:999–1007. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.4.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevaleyre V, Takahashi KA, Castillo PE. Endocannabinoid-mediated synaptic plasticity in the CNS. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2006;29:37–76. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.112834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childers SR, Breivogel CS. Cannabis and endogenous cannabinoid systems. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;51:173–187. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00075-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cravatt BF, Giang DK, Mayfield SP, Boger DL, Lerner RA, Gilula NB. Molecular characterization of an enzyme that degrades neuromodulatory fatty-acid amides. Nature. 1996;384:83–87. doi: 10.1038/384083a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cravatt BF, Lichtman AH. Fatty acid amide hydrolase: an emerging therapeutic target in the endocannabinoid system. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2003;7:469–475. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(03)00079-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristino L, Starowicz K, De Petrocellis L, Morishita J, Ueda N, Guglielmotti V, Di Marzo V. Immunohistochemical localization of anabolic and catabolic enzymes for anandamide and other putative endovanilloids in the hippocampus and cerebellar cortex of the mouse brain. Neuroscience. 2008;151:955–968. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day TA, Rakhshan F, Deutsch DG, Barker EL. Role of fatty acid amide hydrolase in the transport of the endogenous cannabinoid anandamide. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59:1369–1375. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.6.1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch DG, Chin SA. Enzymatic synthesis and degradation of anandamide, a cannabinoid receptor agonist. Biochem Pharmacol. 1993;46:791–796. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(93)90486-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch DG, Glaser ST, Howell JM, Kunz JS, Puffenbarger RA, Hillard CJ, Abumrad N. The cellular uptake of anandamide is coupled to its breakdown by fatty-acid amide hydrolase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:6967–6973. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003161200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Carlo G, Izzo AA. Cannabinoids for gastrointestinal diseases: potential therapeutic applications. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2003;12:39–49. doi: 10.1517/13543784.12.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marzo V, Bisogno T, Sugiura T, Melck D, De Petrocellis L. The novel endogenous cannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol is inactivated by neuronal- and basophil-like cells: connections with anandamide. Biochem J. 1998;331:15–19. doi: 10.1042/bj3310015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marzo V, Fontana A, Cadas H, Schinelli S, Cimino G, Schwartz JC, Piomelli D. Formation and inactivation of endogenous cannabinoid anandamide in central neurons. Nature. 1994;372:686–691. doi: 10.1038/372686a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marzo V, Maccarrone M. FAAH and anandamide: is 2-AG really the odd one out? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008;29:229–233. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egertová M, Giang DK, Cravatt BF, Elphick MR. A new perspective on cannabinoid signalling: complementary localization of fatty acid amide hydrolase and the CB1 receptor in rat brain. Proc Biol Sci. 1998;265:2081–2085. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1998.0543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egertová M, Simon GM, Cravatt BF, Elphick MR. Localization of N-acyl phosphatidylethanolamine phospholipase D (NAPE-PLD) expression in mouse brain: A new perspective on N-acylethanolamines as neural signaling molecules. J Comp Neurol. 2008;506:604–615. doi: 10.1002/cne.21568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fegley D, Kathuria S, Mercier R, Li C, Goutopoulos A, Makriyannis A, Piomelli D. Anandamide transport is independent of fatty-acid amide hydrolase activity and is blocked by the hydrolysis-resistant inhibitor AM1172. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8756–8761. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400997101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu J, Oveisi F, Gaetani S, Lin E, Piomelli D. Oleoylethanolamide, an endogenous PPAR-alpha agonist, lowers body weight and hyperlipidemia in obese rats. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48:1147–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuffrida A, Parsons LH, Kerr TM, Rodriguez de Fonseca F, Navarro M, Piomelli D. Dopamine activation of endogenous cannabinoid signaling in dorsal striatum. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:358–363. doi: 10.1038/7268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser ST, Abumrad NA, Fatade F, Kaczocha M, Studholme KM, Deutsch DG. Evidence against the presence of an anandamide transporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:4269–4274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730816100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goparaju SK, Ueda N, Yamaguchi H, Yamamoto S. Anandamide amidohydrolase reacting with 2-arachidonoylglycerol, another cannabinoid receptor ligand. FEBS Lett. 1998;422:69–73. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01603-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán M. Cannabinoids: potential anticancer agents. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:745–755. doi: 10.1038/nrc1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habayeb OM, Bell SC, Konje JC. Endogenous cannabinoids: metabolism and their role in reproduction. Life Sci. 2002;70:1963–1977. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(01)01539-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanus L, Abu-Lafi S, Fride E, Breuer A, Vogel Z, Shalev DE, Kustanovich I, Mechoulam R. 2-arachidonyl glyceryl ether, an endogenous agonist of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:3662–3665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061029898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardison S, Weintraub ST, Giuffrida A. Quantification of endocannabinoids in rat biological samples by GC/MS: technical and theoretical considerations. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2006;81:106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimotodani Y, Ohno-Shosaku T, Kano M. Endocannabinoids and synaptic function in the CNS. Neuroscientist. 2007;13:127–137. doi: 10.1177/1073858406296716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillard CJ, Edgemond WS, Jarrahian A, Campbell WB. Accumulation of N-arachidonoylethanolamine (anandamide) into cerebellar granule cells occurs via facilitated diffusion. J Neurochem. 1997;69:631–638. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69020631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillard CJ, Jarrahian A. Cellular accumulation of anandamide: consensus and controversy. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;140:802–808. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SM, Bisogno T, Trevisani M, Al-Hayani A, De Petrocellis L, Fezza F, Tognetto M, Petros TJ, Krey JF, Chu CJ, Miller JD, Davies SN, Geppetti P, Walker JM, Di Marzo V. An endogenous capsaicin-like substance with high potency at recombinant and native vanilloid VR1 receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:8400–8405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122196999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin XH, Okamoto Y, Morishita J, Tsuboi K, Tonai T, Ueda N. Discovery and characterization of a Ca2+-independent phosphatidylethanolamine N-acyltransferase generating the anandamide precursor and its congeners. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:3614–3623. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606369200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanai N, Lu R, Satriano JA, Bao Y, Wolkoff AW, Schuster VL. Identification and characterization of a prostaglandin transporter. Science. 1995;268:866–869. doi: 10.1126/science.7754369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karsak M, Gaffal E, Date R, Wang-Eckhardt L, Rehnelt J, Petrosino S, Starowicz K, Steuder R, Schlicker E, Cravatt BF, Mechoulam R, Buettner R, Werner S, Di Marzo V, Tüting T, Zimmer A. Attenuation of allergic contact dermatitis through the endocannabinoid system. Science. 2007;316:1494–1497. doi: 10.1126/science.1142265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Alger BE. Inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 potentiates retrograde endocannabinoid effects in hippocampus. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:697–698. doi: 10.1038/nn1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Isokawa M, Ledent C, Alger BE. Activation of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors enhances the release of endogenous cannabinoids in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10182–10191. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-23-10182.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingsley PJ, Marnett LJ. Analysis of endocannabinoids by Ag+ coordination tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Biochem. 2003;314:8–15. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(02)00643-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingsley PJ, Marnett LJ. LC-MS-MS analysis of neutral eicosanoids. Methods Enzymol. 2007;433:91–112. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)33005-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishimoto Y, Kano M. Endogenous cannabinoid signaling through the CB1 receptor is essential for cerebellum-dependent discrete motor learning. J Neurosci. 2006;26:8829–8837. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1236-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert DM, Di Marzo V. The palmitoylethanolamide and oleamide enigmas : are these two fatty acid amides cannabimimetic? Curr Med Chem. 1999;6:757–773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert DM, DiPaolo FG, Sonveaux P, Kanyonyo M, Govaerts SJ, Hermans E, Bueb J, Delzenne NM, Tschirhart EJ. Analogues and homologues of N-palmitoylethanolamide, a putative endogenous CB(2) cannabinoid, as potential ligands for the cannabinoid receptors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1440:266–274. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(99)00132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert DM, Fowler CJ. The endocannabinoid system: drug targets, lead compounds, and potential therapeutic applications. J Med Chem. 2005;48:5059–5087. doi: 10.1021/jm058183t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leggett JD, Aspley S, Beckett SR, D'Antona AM, Kendall DA. Oleamide is a selective endogenous agonist of rat and human CB1 cannabinoid receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;141:253–262. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung D, Saghatelian A, Simon GM, Cravatt BF. Inactivation of N-acyl phosphatidylethanolamine phospholipase D reveals multiple mechanisms for the biosynthesis of endocannabinoids. Biochemistry. 2006;45:4720–4726. doi: 10.1021/bi060163l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtman AH, Hawkins EG, Griffin G, Cravatt BF. Pharmacological activity of fatty acid amides is regulated, but not mediated, by fatty acid amide hydrolase in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;302:73–79. doi: 10.1124/jpet.302.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ligresti A, Morera E, Van Der Stelt M, Monory K, Lutz B, Ortar G, Di Marzo V. Further evidence for the existence of a specific process for the membrane transport of anandamide. Biochem J. 2004;380:265–272. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Wang L, Harvey-White J, Osei-Hyiaman D, Razdan R, Gong Q, Chan AC, Zhou Z, Huang BX, Kim HY, Kunos G. A biosynthetic pathway for anandamide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:13345–13350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601832103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Verme J, Fu J, Astarita G, La Rana G, Russo R, Calignano A, Piomelli D. The nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha mediates the anti-inflammatory actions of palmitoylethanolamide. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67:15–19. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.006353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccarrone M, Rossi S, Bari M, De Chiara V, Fezza F, Musella A, Gasperi V, Prosperetti C, Bernardi G, Finazzi-Agro A, Cravatt BF, Centonze D. Anandamide inhibits metabolism and physiological actions of 2-arachidonoylglycerol in the striatum. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:152–159. doi: 10.1038/nn2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackie K, Stella N. Cannabinoid receptors and endocannabinoids: evidence for new players. AAPS J. 2006;8:E298–E306. doi: 10.1007/BF02854900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda LA, Lolait SJ, Brownstein MJ, Young AC, Bonner TI. Structure of a cannabinoid receptor and functional expression of the cloned cDNA. Nature. 1990;346:561–564. doi: 10.1038/346561a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland MJ, Bardell TK, Yates ML, Placzek EA, Barker EL. RNAi-Mediated Knockdown of Dynamin 2 Reduces Endocannabinoid Uptake Into Neuronal dCAD Cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:101–108. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.044834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland MJ, Barker EL. Anandamide transport. Pharmacol Ther. 2004;104:117–135. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland MJ, Barker EL. Lipid rafts: a nexus for endocannabinoid signaling? Life Sci. 2005;77:1640–1650. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland MJ, Porter AC, Rakhshan FR, Rawat DS, Gibbs RA, Barker EL. A role for caveolae/lipid rafts in the uptake and recycling of the endogenous cannabinoid anandamide. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:41991–41997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407250200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland MJ, Terebova EA, Barker EL. Detergent-resistant membrane microdomains in the disposition of the lipid signaling molecule anandamide. AAPS J. 2006;8:E95–E100. doi: 10.1208/aapsj080111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore SA, Nomikos GG, Dickason-Chesterfield AK, Schober DA, Schaus JM, Ying BP, Xu YC, Phebus L, Simmons RM, Li D, Iyengar S, Felder CC. Identification of a high-affinity binding site involved in the transport of endocannabinoids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17852–17857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507470102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishita J, Okamoto Y, Tsuboi K, Ueno M, Sakamoto H, Maekawa N, Ueda N. Regional distribution and age-dependent expression of N-acylphosphatidylethanolamine-hydrolyzing phospholipase D in rat brain. J Neurochem. 2005;94:753–762. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muccioli GG, Xu C, Odah E, Cudaback E, Cisneros JA, Lambert DM, López Rodríguez ML, Bajjalieh S, Stella N. Identification of a novel endocannabinoid-hydrolyzing enzyme expressed by microglial cells. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2883–2889. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4830-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro S, Thomas KL, Abu-Shaar M. Molecular characterization of a peripheral receptor for cannabinoids. Nature. 1993;365:61–65. doi: 10.1038/365061a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyilas R, Dudok B, Urban GM, Mackie K, Watanabe M, Cravatt BF, Freund TF, Katona I. Enzymatic machinery for endocannabinoid biosynthesis associated with calcium stores in glutamatergic axon terminals. J Neurosci. 2008;28:1058–1063. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5102-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto Y, Morishita J, Tsuboi K, Tonai T, Ueda N. Molecular characterization of a phospholipase D generating anandamide and its congeners. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:5298–5305. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306642200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto Y, Wang J, Morishita J, Ueda N. Biosynthetic pathways of the endocannabinoid anandamide. Chem Biodivers. 2007;4:1842–1857. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200790155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortar G, Cascio MG, Moriello AS, Camalli M, Morera E, Nalli M, Di Marzo V. Carbamoyl tetrazoles as inhibitors of endocannabinoid inactivation: a critical revisitation. Eur J Med Chem. 2008;43:62–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2007.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Gutiérrez S, Hawkins EG, Viso A, López-Rodríguez ML, Cravatt BF. Comparison of anandamide transport in FAAH wild-type and knockout neurons: evidence for contributions by both FAAH and the CB1 receptor to anandamide uptake. Biochemistry. 2004;43:8184–8190. doi: 10.1021/bi049395f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overton HA, Babbs AJ, Doel SM, Fyfe MC, Gardner LS, Griffin G, Jackson HC, Procter MJ, Rasamison CM, Tang-Christensen M, Widdowson PS, Williams GM, Reynet C. Deorphanization of a G protein-coupled receptor for oleoylethanolamide and its use in the discovery of small-molecule hypophagic agents. Cell Metab. 2006;3:167–175. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parolaro D, Massi P, Rubino T, Monti E. Endocannabinoids in the immune system and cancer. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2002;66:319–332. doi: 10.1054/plef.2001.0355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrish JC, Nichols DE. Serotonin 5-HT(2A) receptor activation induces 2-arachidonoylglycerol release through a phospholipase c-dependent mechanism. J Neurochem. 2006;99:1164–1175. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parton RG. Caveolae--from ultrastructure to molecular mechanisms. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:162–167. doi: 10.1038/nrm1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertwee RG. Cannabinoid receptors and pain. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;63:569–611. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike LJ, Han X, Chung KN, Gross RW. Lipid rafts are enriched in arachidonic acid and plasmenylethanolamine and their composition is independent of caveolin-1 expression: a quantitative electrospray ionization/mass spectrometric analysis. Biochemistry. 2002;41:2075–2088. doi: 10.1021/bi0156557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piomelli D. The molecular logic of endocannabinoid signalling. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:873–884. doi: 10.1038/nrn1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter AC, Sauer JM, Knierman MD, Becker GW, Berna MJ, Bao J, Nomikos GG, Carter P, Bymaster FP, Leese AB, Felder CC. Characterization of a novel endocannabinoid, virodhamine, with antagonist activity at the CB1 receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;301:1020–1024. doi: 10.1124/jpet.301.3.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razani B, Woodman SE, Lisanti MP. Caveolae: from cell biology to animal physiology. Pharmacol Rev. 2002;54:431–467. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.3.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson D, Ortori CA, Chapman V, Kendall DA, Barrett DA. Quantitative profiling of endocannabinoids and related compounds in rat brain using liquid chromatography-tandem electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Anal Biochem. 2007;360:216–226. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2006.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimmerman N, Hughes HV, Bradshaw HB, Pazos MX, Mackie K, Prieto AL, Walker JM. Compartmentalization of endocannabinoids into lipid rafts in a dorsal root ganglion cell line. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:380–389. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez de Fonseca F, Navarro M, Gómez R, Escuredo L, Nava F, Fu J, Murillo-Rodríguez E, Giuffrida A, LoVerme J, Gaetani S, Kathuria S, Gall C, Piomelli D. An anorexic lipid mediator regulated by feeding. Nature. 2001;414:209–212. doi: 10.1038/35102582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronesi J, Gerdeman GL, Lovinger DM. Disruption of endocannabinoid release and striatal long-term depression by postsynaptic blockade of endocannabinoid membrane transport. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1673–1679. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5214-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saario SM, Savinainen JR, Laitinen JT, Järvinen T, Niemi R. Monoglyceride lipase-like enzymatic activity is responsible for hydrolysis of 2-arachidonoylglycerol in rat cerebellar membranes. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;67:1381–1387. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer JE, Lodish HF. Expression cloning and characterization of a novel adipocyte long chain fatty acid transport protein. Cell. 1994;79:427–436. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90252-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon GM, Cravatt BF. Endocannabinoid biosynthesis proceeding through glycerophospho-N-acyl ethanolamine and a role for alpha/beta-hydrolase 4 in this pathway. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:26465–26472. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604660200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon GM, Cravatt BF. Anandamide biosynthesis catalyzed by the phosphodiesterase GDE1 and detection of glycerophospho-N-acyl ethanolamine precursors in mouse brain. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:9341–9349. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707807200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart D, Gunthorpe MJ, Jerman JC, Nasir S, Gray J, Muir AI, Chambers JK, Randall AD, Davis JB. The endogenous lipid anandamide is a full agonist at the human vanilloid receptor (hVR1) Br J Pharmacol. 2000;129:227–230. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snider NT, Kornilov AM, Kent UM, Hollenberg PF. Anandamide metabolism by human liver and kidney microsomal cytochrome p450 enzymes to form hydroxyeicosatetraenoic and epoxyeicosatrienoic acid ethanolamides. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;321:590–597. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.119321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner H, Bonner TI, Zimmer AM, Kitai ST, Zimmer A. Altered gene expression in striatal projection neurons in CB1 cannabinoid receptor knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:5786–5790. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez J, Bermudez-Silva FJ, Mackie K, Ledent C, Zimmer A, Cravatt BF, de Fonseca FR. Immunohistochemical description of the endogenous cannabinoid system in the rat cerebellum and functionally related nuclei. J Comp Neurol. 2008;509:400–421. doi: 10.1002/cne.21774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara Y, Nishii H, Takahashi T, Yamauchi J, Mizuno N, Tago K, Itoh H. The lipid raft proteins flotillins/reggies interact with Galphaq and are involved in Gq-mediated p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation through tyrosine kinase. Cell Signal. 2007;19:1301–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun YX, Tsuboi K, Okamoto Y, Tonai T, Murakami M, Kudo I, Ueda N. Biosynthesis of anandamide and N-palmitoylethanolamine by sequential actions of phospholipase A2 and lysophospholipase D. Biochem J. 2004;380:749–756. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan B, Bradshaw HB, Rimmerman N, Srinivasan H, Yu YW, Krey JF, Monn MF, Chen JS, Hu SS, Pickens SR, Walker JM. Targeted lipidomics: discovery of new fatty acyl amides. AAPS J. 2006;8:E461–E465. doi: 10.1208/aapsj080354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tramèr MR, Carroll D, Campbell FA, Reynolds DJ, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Cannabinoids for control of chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting: quantitative systematic review. BMJ. 2001;323:16–21. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7303.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda N, Yamamoto K, Yamamoto S, Tokunaga T, Shirakawa E, Shinkai H, Ogawa M, Sato T, Kudo I, Inoue K. Lipoxygenase-catalyzed oxygenation of arachidonylethanolamide, a cannabinoid receptor agonist. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1254:127–134. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(94)00170-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varma N, Carlson GC, Ledent C, Alger BE. Metabotropic glutamate receptors drive the endocannabinoid system in hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2001;21:RC188. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-24-j0003.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellani V, Petrosino S, De Petrocellis L, Valenti M, Prandini M, Magherini PC, McNaughton PA, Di Marzo V. Functional lipidomics. Calcium-independent activation of endocannabinoid/endovanilloid lipid signalling in sensory neurons by protein kinases C and A and thrombin. Neuropharmacology. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson SJ, Benson JAJ, Joy JE. Marijuana and medicine: assessing the science base: a summary of the 1999 Institute of Medicine report. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:547–552. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.6.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei BQ, Mikkelsen TS, McKinney MK, Lander ES, Cravatt BF. A second fatty acid amide hydrolase with variable distribution among placental mammals. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:36569–36578. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606646200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wettschureck N, van der Stelt M, Tsubokawa H, Krestel H, Moers A, Petrosino S, Schutz G, Di Marzo V, Offermanns S. Forebrain-specific inactivation of Gq/G11 family G proteins results in age-dependent epilepsy and impaired endocannabinoid formation. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:5888–5894. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00397-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J, Wood J, Pandarinathan L, Karanian DA, Bahr BA, Vouros P, Makriyannis A. Quantitative method for the profiling of the endocannabinoid metabolome by LC-atmospheric pressure chemical ionization-MS. Anal Chem. 2007;79:5582–5593. doi: 10.1021/ac0624086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zygmunt PM, Petersson J, Andersson DA, Chuang H, Sørgård M, Di Marzo V, Julius D, Högestätt ED. Vanilloid receptors on sensory nerves mediate the vasodilator action of anandamide. Nature. 1999;400:452–457. doi: 10.1038/22761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]