Abstract

Prompted by a recent report of the possible carcinogenic effect of shiftwork focusing on the disruption of circadian rhythms, we review studies involving shifts in schedule implemented at varying intervals in unicells, insects and mammals, including humans. Results indicate the desirability to account for a broader-than-circadian view. They also suggest the possibility of optimizing schedule shifts by selecting intervals between consecutive shifts associated with potential side-effects such as an increase in cancer risk. Toward this goal, marker rhythmometry is most desirable. The monitoring of blood pressure and heart rate present the added benefit of assessing cardiovascular disease risks resulting not only from an elevated blood pressure but also from abnormal variability in blood pressure and/or heart rate of normotensive as well as hypertensive subjects.

In a Policy Watch report published in the December 2007 issue of The Lancet Oncology, the WHO International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working Group concluded: “Shiftwork that involves circadian disruption is probably carcinogenic” (1). Human life is also potentially carcinogenic and involves disruptions of a much broader-than-circadian time structure that can be optimized, although generalizations are best qualified. In our hands (2, 3) and in those of Kort et al. (4), a temporal disorder can be carcinostatic, as also found by Carlebach and Ashkenazi (5), and can even prolong lifespans (3, 6, 7), thorough adverse reports on humans notwithstanding (8).

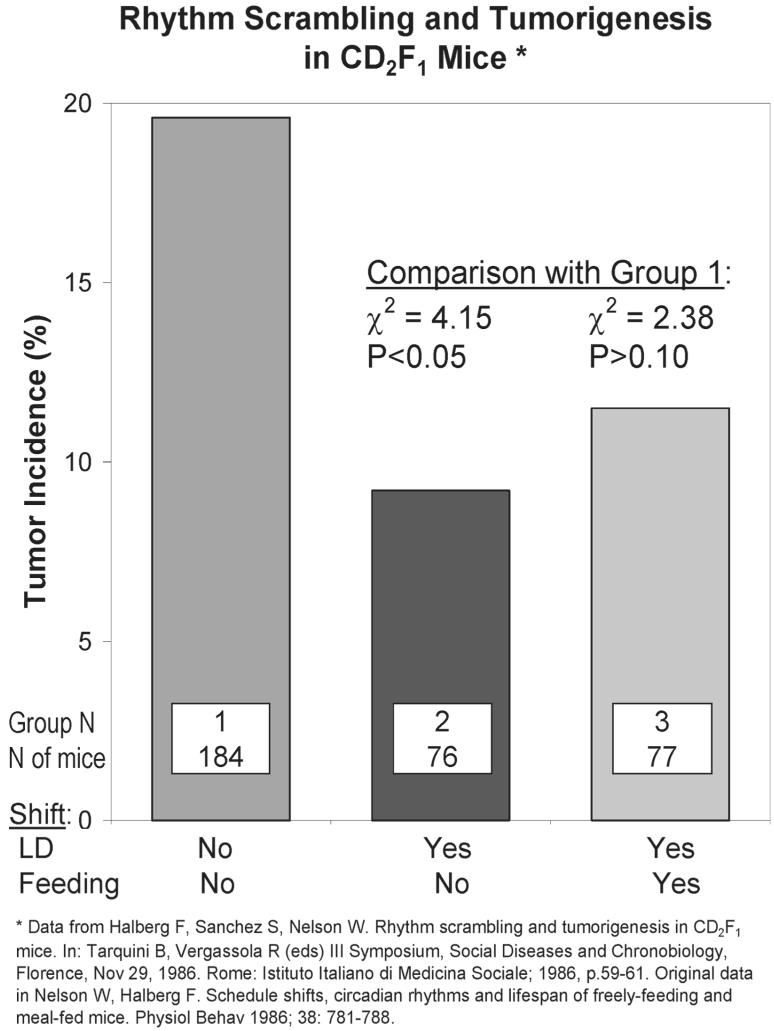

Effects of competing photic and nonphotic synchronizers of circadian rhythms were tested in lifetime studies on mice subjected to calorie restriction and/or to weekly shifts of the lighting regimen, repeatedly reviewed (6, 7). A prolongation of tenth-decile survival time beyond that achieved by calorie restriction alone was observed among mice subjected to shifts in lighting but not in feeding, so that in alternate weeks, food was offered during the rest (light) span. Murine mammary carcinogenesis, under controlled conditions, was reduced in this group (χ2 = 4.15, P<0.05) (2), Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Tumor incidence is here shown to be statistically significantly less among mice subjected to weekly shifts of the lighting but not of the feeding regimen by comparison with mice kept on a fixed lighting and feeding regimen. No statistically significant difference in tumor incidence was found between this reference group and a group of mice subjected to weekly shifts of both the lighting and feeding schedules, yet numerically tumor incidence was reduced in this group as well. Shifts can thus be beneficial, e.g., carcinostatic under certain circumstances, when they may enhance the effect of calorie restriction; food consumption was strictly controlled (3). © Halberg.

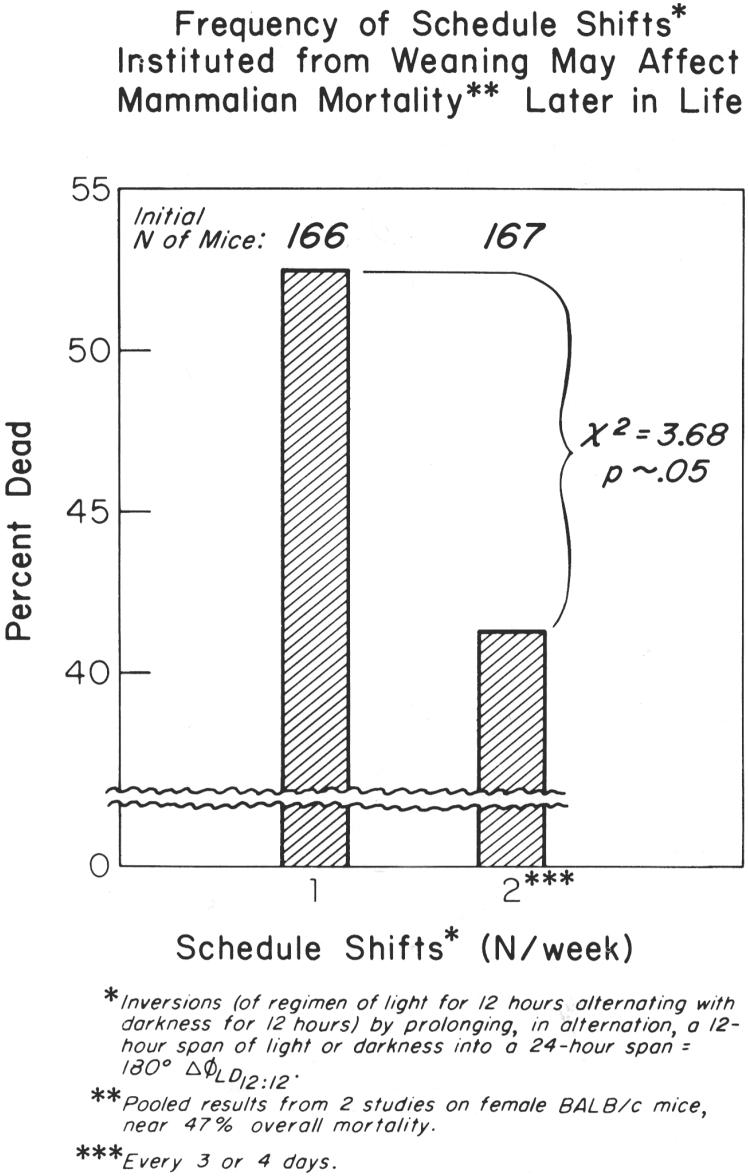

Mortality of mice was reduced by an increase in the frequency of changes in lighting schedule from weekly to twice-weekly, possibly by virtue of a more direct manipulation of half-weekly rhythms (6), Figure 2. At about 50% overall mortality, only 41% of mice shifted twice a week were dead versus 53% of mice shifted weekly (χ2 = 3.68, P∼0.05). Beyond circadians, this result led to decades-long studies of infradians in some insects and unicells as well as in rodents and humans. In cooperation with Dr. Mirian David Marques (9) (of the Museu de Zoologia, Universidad de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil), the late Dr. Laurence K. Cutkomp (at the Department of Entomology, University of Minnesota, St. Paul, Minnesota, USA), Dr. Dora K. Hayes (10) (at the US Department of Agriculture, Beltsville, Maryland) and the late Dr. Hans-Georg Schweiger (11) (at his Max-Planck-Institute for Cell Biology in Ladenburg, near Heidelberg, Germany), we found that shifts can be favorable, notably in Acetabularia, a unicell from which the nucleus can be removed, and thus intracellular mechanisms can be studied.

Figure 2.

Studies on BALB/c mice showed that schedule-shifts implemented twice weekly were associated with longer survival than weekly shifts, suggesting the importance of a structured (nonlinear) role played by the interval between consecutive shifts, which finding then led to a long series of systematic studies on insects with Dr. Dora K. Hayes of the US Department of Agriculture in Beltsville, MD, USA, and with the entomology department of the University of Minnesota, and on unicells with Dr. Sigrid Berger, Max-Planck-Institute on Cell Biology, Ladenburg bei Heidelberg, Germany (see Figures 3-5). Shifts every 3 or 4 days probably involve about half-weekly (circasemiseptan) rhythms more directly than weekly shifts and may offer a slight advantage, also insofar as the adjustment of some circadian rhythms, notably that of mitotic activity, is as yet in an early, slow stage. © Halberg.

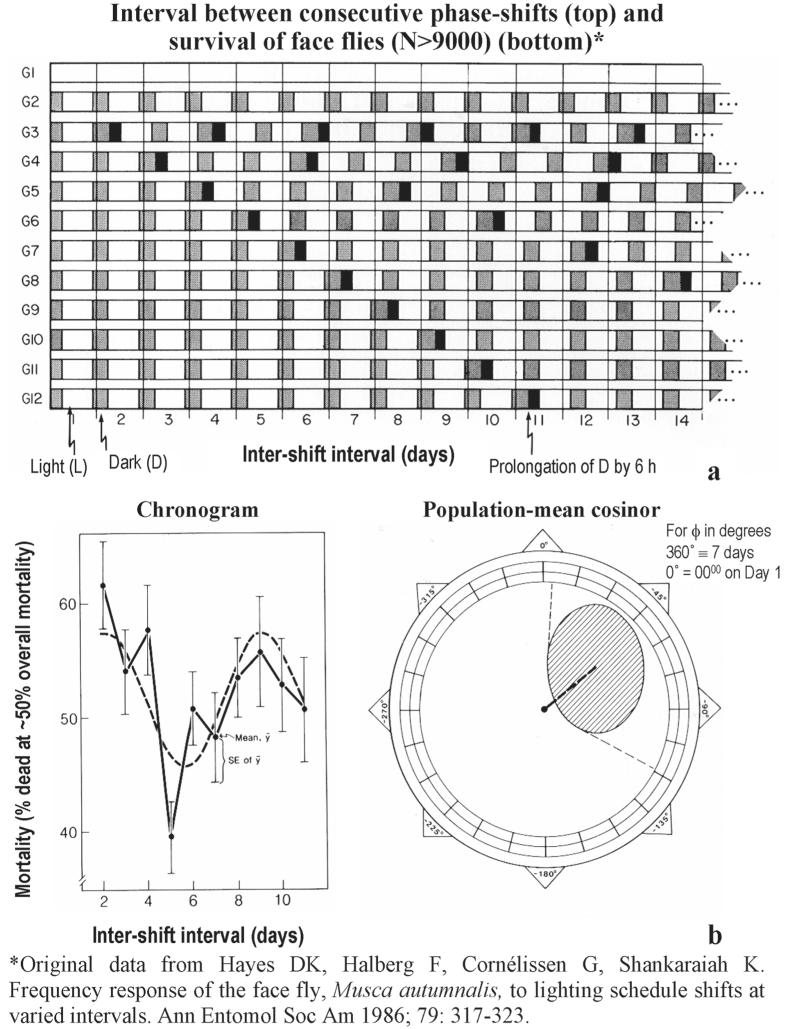

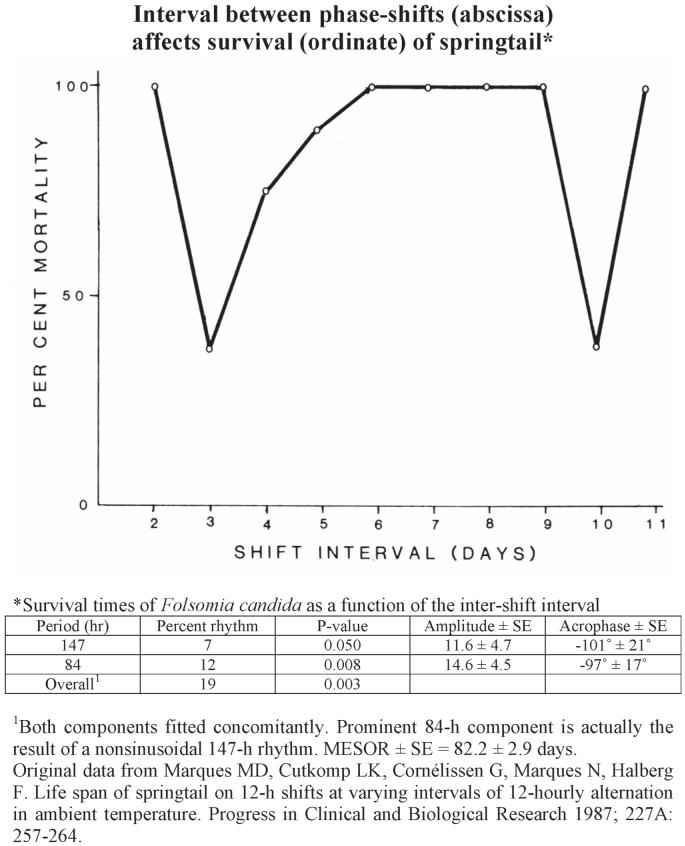

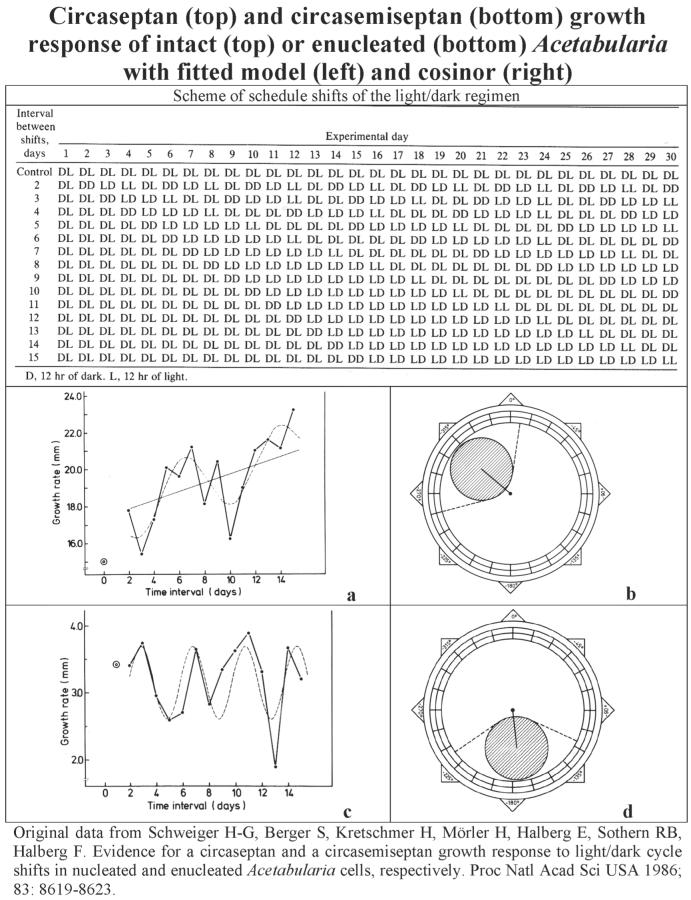

These investigations were summarized for face flies (10), Figure 3, springtails (9), Figure 4, and unicells, Acetabularia (11), Figure 5. At overall 50% mortality, the number of deaths was highest in face flies shifted every 2 or 9 days. Mortality also differed as a function of the shift interval in springtails. For unicells subjected to 14 different patterns of shifts differing by 1 day between consecutive shifts of the lighting regimen (implemented either every 2, 3, …, or 15 days), growth rates differed in a seemingly about-weekly (circaseptan) pattern, rather than outcomes being better or worse, depending linearly on the length of the inter-shift interval, suggesting the desirability to account for circaseptans in studies of schedule shifts.

Figure 3.

With an experimental design shown on top, 29 experiments were carried out by Dr. Dora K. Hayes over 18 months on 7,835 adult face flies kept at 26 ± 1°C. When overall mortality reached about 50% in each separate experiment, groups of face flies subjected throughout a lifespan to shifts of a photoperiod of 16 hours of light alternating with 8 hours of darkness (as a 6-hour prolongation of the dark span) at varying intervals (every 2, 3, …, or 11 days) had different outcomes. Their summary is shown as means ± standard errors as a function of shift interval, to which a 7-day cosine curve is fitted by cosinor (bottom left). The extent of reproducibility (and the uncertainty) of the circaseptan response across the 29 experiments is illustrated by the statistically significant population-mean cosinor summary of the individual results (bottom right). The amplitude and phase of the response pattern are shown by the length and angle of a directed line (vector). Non-overlap of the center (pole) by the 95% confidence ellipse of the vector indicates that the zero-amplitude (no-rhythm) assumption is rejected, attesting to the statistical significance of the model. These results on face flies and those on springtails (Figure 4) and unicells (Figure 5) indicate that the role of the interval is structured by the stages of multi-frequency rhythms, rather than being better (or worse), depending linearly and solely upon the length of the inter-shift interval as a function only of the speed and phase relations of circadian rhythm-adjustments and hence on internal circadian phase relations, some of which may constitute circadian rhythm disruption (cf.1). © Halberg.

Figure 4.

Mortality differs as a function of shift interval in the springtail (Folsomia candida). At different intervals (every 2, 3, …, or 11 days), a regimen of quasi-optimal and non-optimal ambient temperatures (alternating at 12-hour intervals) was shifted. Lifespan was lengthened rather than shortened by comparison with unshifted controls in association with shifts every 3 or 10 days, a desirable effect like that in Figure 1. Table demonstrates a desynchronized about-weekly (147-hour) but synchronized half-weekly (84-hour) pattern (9). © Halberg.

Figure 5.

Acetabularia growth rate was assessed as the change in the length of cells measured on days (10, 20 and) 30 as compared to their length at the start of the experiment, when they averaged about 30 mm. The response pattern in the growth rate of intact (middle) or enucleated (bottom) cells differs in groups of these unicells shifted at varying intervals ranging from 2 to 14 days, plotted on the abscissa as differing by 1-day between consecutive shifts implemented either every 2, 3, …, or 15 days (top). A 7-day (middle) or 3.5-day (bottom) cosine curve is fitted to growth rate, using the interval between shifts as the time scale (left, middle and bottom). Polar plot (right, middle and bottom) shows amplitude and phase as the length and angle, respectively, of a directed line (vector). Elliptical 95% confidence regions attest to the statistical significance of the fitted model by their non-overlap of the pole (center of circle) whereby the zero-amplitude or no-rhythm assumption is rejected (11). © Halberg.

Circaseptan gating had been found earlier in the effect of manipulating environmental temperature on oviposition by springtails (12). In a unicell, a circaseptan pattern becomes circasemiseptan (about half-weekly) after its enucleation (11). This finding suggested the operation of a built-in circasemiseptan cytoplasmic mechanism in its own right. It is frequency-demultiplied by the nucleus to a circaseptan pattern. Longitudinal series analyzed by signal averaging of several cells document the partly endogenous nature of the circaseptan component by its free-run and that of the also-present circasemiseptan component, the about-weekly rhythm being more prominent than the concurrently assessed free-running circadian rhythm characterizing Acetabularia’s electrical activity after release into continuous light (13). Extrapolating to mammals, are nuclear and cytoplasmic infradian mechanisms (in mammals’ pineal or hypothalamus) subtractively coupled in frequency while the circadians of the suprachiasmatic nuclei are subtractively coupled in amplitude (14)?

Melatonin suppression by increased light exposure of night-shift workers is putatively associated with increased cancer risk (1). Ultradian-to-infradian components are in this vitamin/hormone’s chronome (15, 16) that is affected by exposure to magnetic fields (17). Magnetic storms (18) depress the circadian amplitude of melatonin in human saliva. The amplitude and MESOR (midline estimating statistic of rhythm, a rhythm-adjusted mean) of the rats’ circadian rhythms of melatonin in the first 3 (disturbed) vs. the last 3 (quiet) days of a 7-day experiment were higher in the hypothalamus and lower in the pineal (19). There is no consensus regarding magnetic effects on cancer risk (20-22). At the wrong circadian stage, melatonin can enhance tumor growth, as found first in vitro by Bartsch and Bartsch (23), reducing lifespan (24-26).

Whether melatonin supplementation reduces any increased cancer risk among night-shift workers remains to be determined, abiding by “First do no harm” when the same dose of melatonin given at different circadian stages can either reduce or increase tumor growth and survival. Cancer itself can be associated with a desynchronized circadian system (27-29). Nonphotic infradian cycles coded in our genes coexist, compete and sometimes dominate over central and peripheral circannual systems, prompting a time structural approach including focus upon (age and other) trends, (deterministic) chaos and a rhythm spectrum with feedsideward interactions among these elements that underlie different effects in different cycles’ stages (30, 31).

Schedule shifts may be “good” (prolonging the life of an enucleated single cell) (32), neutral or “bad”. This applies to effects on growth, Figure 5, including carcinogenesis, Figure 1, and survival (3, 9, 10). Chronomics — investigating multi-frequency interactions among time structures in and around us, societal and climatic, including space weather — is indicated for shiftwork studies.

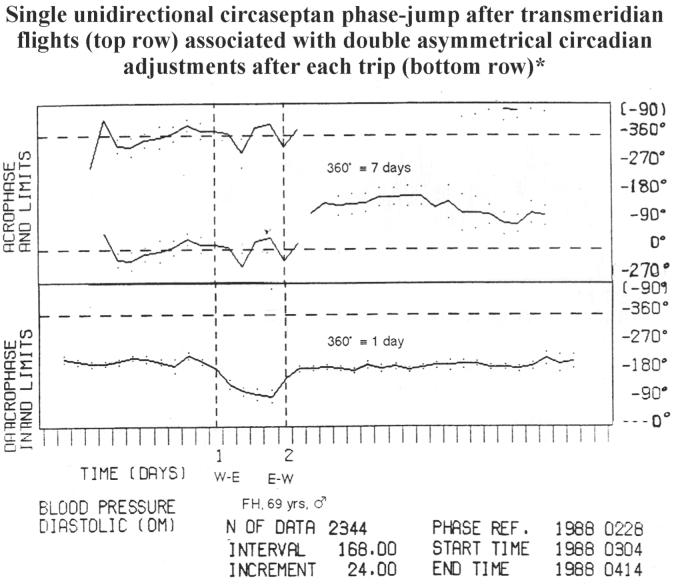

Subjects monitoring blood pressure around-the-clock for decades reveal differences in circadian vs. circaseptan phase-behavior, Figure 6. The circadian amplitude of blood pressure but not of heart rate is reduced and the circadian acrophase is delayed in night-shift workers (33-35). Table 1 summarizes results of a 24-hour study (a severe limitation in length) and shows a sensitivity of a chronobiologic approach more generally.

Figure 6.

Adjustments after human transmeridian flights constitute a confounded, yet available model for the study of shifts in about 7-day (circaseptan) as well as circadian rhythms. A single circaseptan acrophase jump (upper row) is seen for the diastolic blood pressure of a 69-year-old man (FH) following a trip of 5 days from Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA, to Nice, France (W-E; vertical dashed line 1), and back to Minnesota (E-W; vertical dashed line 2). This pattern was also seen in a woman (EH), again with a lack of return of the circaseptan acrophase to the original phase position after round-trip transmeridian flights (not shown).

The circadian acrophase (lower display) shows a) a gradual change after the trip from W-E and b) asymmetry with a slower phase advance (after W-E) and rapid adjustment (resynchronization) after the return flight from E-W. A similar finding was also made when the initial flight away from home was from east to west and further, in the case of a man (EH) with a home on both continents, so that any effect of “from home to abroad” vs. “from abroad to home” was controlled. Note the 1-week interval used for analysis that shows a spurious anticipation of the rapid circadian adjustment after the return flight, an artifact due to the fact that results are plotted at the midpoints of a 7-day interval progressively displaced throughout the time series, thereby including data before and after each shift into the 1-week intervals overlapping the days of flights.

The shift in routine also involves circannual and other rhythms (not shown). The human immune system, in many of its components, is organized in a multi-frequency time structure (circadian, circaseptan, circannual) (43) and other (44) rhythms. To be investigated further are different adjustment rates and sometimes different directions of shifts (polarity) of various circadian rhythms and by gating or modulation by rhythms with lower-than-circadian (infradian) frequencies, about half-weekly (circasemiseptan), circaseptan, circannual and other (44, 45). The literature on signatures in human psychophysiology and pathology of a wide spectrum of transdisciplinarily novel spectral components is here illustrated by a representative single figure involving only two spectral components. © Halberg.

Table 1.

Effect of Shiftwork on Blood Pressure (BP) and Heart Rate (HR) in Bulgarian Air Traffic Controllers*.

| Endpoint | Systolic BP | Diastolic BP | HR | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | P | F | P | F | P | ||||

| Single ∼18:00 value | 0.372 | 0.692 | 0.282 | 0.757 | 0.199 | 0.820 | |||

| Standard deviation | 1.380 | 0.267 | 4.290 | 0.023 | 1 | 0.479 | 0.624 | ||

| MESOR | 0.158 | 0.854 | 0.068 | 0.934 | 2.141 | 0.135 | |||

| 24-hour amplitude | 4.700 | 0.017 | 1,2 | 7.521 | 0.002 | 1,2 | 0.356 | 0.704 | |

| 24-hour acrophase | 3.975 | 0.029 | 3 | 6.663 | 0.004 | 3 | 7.914 | 0.002 | 3 |

Shift schedules being compared: Afternoon, Morning, or Night

Reduced in night-shift workers

Largest in afternoon-shift workers

Delayed in night-shift workers

“With an ambulatory monitor from Colin Medical Instruments, 33 male air traffic controllers working at one of 3 airports (Varna, Burgos or Sofia, Bulgaria) measured their BP and HR mostly at 30-minute intervals for 24 hours. Their age ranged between 25 and 56 years; they had been on the job for 2 to 26 years. At the time of monitoring, 10 worked morning shifts, 9 afternoon shifts and 14 night shifts. Only one air traffic controller had a hyperbaric index greater than 50 mm Hg × h during 24 h for systolic (S) BP. A statistically significant circadian population rhythm was demonstrated for each variable in each shift group (P < 0.05). The effects of shift work on the BP and HR rhythm characteristics (MESOR, circadian amplitude and acrophase) were assessed, as were any effects on the 24-h standard deviation and on the measurements at a single timepoint (18:00). Whereas no difference among the three shift groups was found in the case of a single timed measurement or for the MESOR, a reduced circadian amplitude on night shift was documented for both SBP (P = 0.017) and diastolic (D) BP (P = 0.002) but not for HR (P > 0.20). The circadian amplitude is more sensitive than the standard deviation since in the latter case a difference is found only for DBP (P = 0.023), the night shifters having the smallest variation. A later acrophase is also found in night shift workers (SBP: P = 0.029; DBP: P = 0.004; HR: P = 0.002), which is likely brought about by differences in rest-activity schedule.”

Different variables and different spectral components in the same variable of the same organism can adjust at different rates, abruptly or gradually, even in opposite directions. A broader-than-circadian clock perspective on longer than 24-h records (34, 35) thus seems warranted.

Discrepancies among diverse shiftwork studies could relate in part to intervals between shifts. These intervals should be invariably stated (for eventually comparing studies in epidemiology) and should be optimized based on one or several proxy endpoints, such as those available by vascular monitoring, which, as a dividend, will detect any increase in the cardiovascular disease risk of shiftworkers (35). It will reveal the presence of any vascular variability disorders (VVDs) that carry a risk of morbid events greater than hypertension (36-42). Infradians are involved in shiftwork, as in transmeridian flights (43-46), Figure 6. Optimizing the interval between shifts in mammals, including humans, remains a practical challenge, in order to attempt to allay any worry about carcinogenicity on the part of shiftworkers. The step from unicellulars and insects to rodents can never replace now-feasible human ambulatory physiologic (including motor activity, core and surface temperature and vascular) and performance monitoring on a larger scale — in keeping with Pope’s “the proper study of Mankind is Man” (47), in keeping with Charron’s “la vraye science et le vray estude de l’homme, c’est l’homme” (48).

Acknowledgments

Support: GM-13981 (FH), University of Minnesota Supercomputing Institute (GC, FH).

REFERENCES

- 1.Straif K, Baan R, Grosse Y, Secretan B, El Ghissassi F, Bouvard V, Altieri A, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Cogliano V, WHO International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working Group Carcinogenicity of shiftwork, painting, and fire-fighting. The Lancet Oncology. 2007;8:1065–1066. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70373-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halberg F, Sanchez S, Nelson W. Rhythm scrambling and tumorigenesis in CD2F1 mice. In: Tarquini B, Vergassola R, editors. III Int. Symposium, Social Diseases and Chronobiology; Florence. Nov. 29, 1986; Rome: Istituto Italiano di Medicina Sociale; 1986. pp. 59–61. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson W, Halberg F. Schedule-shifts, circadian rhythms and lifespan of freely-feeding and meal-fed mice. Physiol Behav. 1986;38:781–788. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(86)90043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kort WJ, Zondervan PE, Hulsman LOM, Weijma JM, Westbroek DL. Light-dark-shift stress, with special reference to spontaneous tumor incidence in female BN rats. JNCI. 1986;76:439–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlebach R, Ashkenazi IE. Temporal disorder: therapeutic considerations. Chronobiologia. 1987;14:162. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halberg F, Nelson W. Some aspects of chronobiology relating to the optimization of shift-work. In: Rentos PG, Shepard RD, editors. Shift-Work and Health. NIOSH Research Symposium, Shift-Work and Health; Cincinnati. June 12-13, 1975; Washington DC: US Department of Health, Education and Welfare; 1976. pp. 13–47. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halberg F, Nelson W, Cornélissen G, Chibisov S. (presenter). Beyond circadian system and age-related optimization in models of jet lag and shiftwork Proceedings, International Symposium, Problems of ecological and physiological adaptation, People’s Friendship University of Russia 2007538–542.Moscow30-31 Jan 2007People’s Friendship University of Russia; Moscow [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pati AK, Achari KV. Shift work adversely affects human longevity. Current Science. 2007;92:890–891. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marques MD, Cutkomp LK, Cornélissen G, Marques N, Halberg F. Life span of springtail on 12-h shifts at varying intervals of 12-hourly alternation in ambient temperature. Progress in Clinical and Biological Research. 1987;227A:257–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayes DK, Halberg F, Cornélissen G, Shankaraiah K. Frequency response of the face fly, Musca autumnalis, to lighting schedule shifts at varied intervals. Ann Entomol Soc Am. 1986;79:317–323. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schweiger H-G, Berger S, Kretschmer H, Mörler H, Halberg E, Sothern RB, Halberg F. Evidence for a circaseptan and a circasemiseptan growth response to light/dark cycle shifts in nucleated and enucleated Acetabularia cells, respectively. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:8619–8623. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.22.8619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cutkomp LK, Halberg F, Cornélissen G. Temperature effect on infradian oviposition rhythms in the springtail, Folsomia candida (Willem) In: Haus E, Kabat H, editors. Chronobiology 1982-1983. S. Karger; Basel: 1984. pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halberg F, Cornélissen G, Katinas G, Hillman D, Schwartzkopff O. Season’s Appreciations 2000: Chronomics complement, among many other fields, genomics and proteomics. Neuroendocrinol Lett. 2001;22:53–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halberg Franz, Cornélissen G, Katinas G, Syutkina EV, Sothern RB, Zaslavskaya R, Halberg Francine, Watanabe Y, Schwartzkopff O, Otsuka K, Tarquini R, Perfetto P, Siegelova J. Transdisciplinary unifying implications of circadian findings in the 1950s. J Circadian Rhythms. 2003;1(2):61. doi: 10.1186/1740-3391-1-2. www. JCircadianRhythms.com/content/pdf/1740-3391-2-3.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Halberg F, Cornélissen G, Conti A, Maestroni G, Maggioni C, Perfetto F, Salti R, Tarquini R, Katinas GS, Schwartzkopff O. The pineal gland and chronobiologic history: mind and spirit as feedsidewards in time structures for prehabilitation. In: Bartsch C, Bartsch H, Blask DE, Cardinali DP, Hrushesky WJM, Mecke W, editors. The Pineal Gland and Cancer: Neuroimmunoen docrine Mechanisms in Malignancy. Springer; Heidelberg: 2001. pp. 66–116. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cornélissen G, Halberg F, Zeman M, Jozsa R, Tarquini R, Perfetto F, Salti R, Bakken EE. Toward a chronome (time structure) of melatonin. In: Pandi-Perumal SR, Cardinali DP, editors. Melatonin: From Molecules to Therapy. Nova Biomedical Books; New York: 2007. pp. 135–176. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burch JB, Reif JB, Yost MG, Keefe TJ, Pitrat CA. Reduced excretion of a melatonin metabolite in workers exposed to 60 Hz magnetic fields. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150:27–36. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weydahl A, Sothern RB, Cornélissen G, Wetterberg L. Geomagnetic activity influences the melatonin secretion at latitude 70°N. Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy. 2001;55:57–62. doi: 10.1016/s0753-3322(01)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jozsa R, Halberg F, Cornélissen G, Zeman M, Kazsaki J, Csernus V, Katinas GS, Wendt HW, Schwartzkopff O, Stebelova K, Dulkova K, Chibisov SM, Engebretson M, Pan W, Bubenik GA, Nagy G, Herold M, Hardeland R, Hüther G, Pöggeler B, Tarquini R, Perfetto F, Salti R, Olah A, Csokas N, Delmore P, Otsuka K, Bakken EE, Allen J, Amory-Mazaudier C. Chronomics, neuroendocrine feedsidewards and the recording and consulting of nowcasts -- forecasts of geomagnetics. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2005;59(Suppl 1):S24–S30. doi: 10.1016/s0753-3322(05)80006-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosch PJ, Markov MS, editors. Bioelectromagnetic Medicine. Marcel Dekker; New York: 2004. p. 850. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adair RK. Constraints on biological effects of weak extremely low-frequency electromagnetic fields. Physical Reviews A. 1991;43:1039–1048. doi: 10.1103/physreva.43.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bennett WR. Cancer and power lines. Physics Today. 1994;24(4):23–29. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bartsch H, Bartsch C. Effect of melatonin on experimental tumors under different photoperiods and times of administration. J Neur Trans. 1981;52:269–279. doi: 10.1007/BF01256752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wrba H, Dutter A, de la Peña S Sanchez, Cornélissen G, Halberg F. Secular or circadian effects of placebo and melatonin on murine breast cancer? Progress in Clinical and Biological Research. 1990;341A:31–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de la Peña S Sánchez. The feedsideward of cephalo-adrenal immune interactions. Chronobiologia. 1993;20:1–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cornélissen G, Halberg F, Perfetto F, Tarquini R, Maggioni C, Wetterberg L. Melatonin involvement in cancer: methodological considerations. In: Bartsch C, Bartsch H, Blask DE, Cardinali DP, Hrushesky WJM, Mecke W, editors. The Pineal Gland and Cancer: Neuroimmunoendocrine Mechanisms in Malignancy. Springer; Heidelberg: 2001. pp. 117–149. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gautherie M, Gros Ch. Circadian rhythm alteration of skin temperature in breast cancer. Chronobiologia. 1977;4:1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Halberg E, Halberg F, Cornélissen G, Garcia-Sainz M, Simpson HW, Taggett-Anderson MA, Haus E. Toward a chronopsy: Part II. A thermopsy revealing asymmetrical circadian variation in surface temperature of human female breasts and related studies. Chronobiologia. 1979;6:231–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang ZR, Wan CM, Lei Y, Cornélissen G, Halberg F. Phase-zero trial of clinical chronoradiotherapy of lung cancer. Chronobiologia. 1994;21:155–157. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Halberg F, Cornélissen G, Otsuka K, Watanabe Y, Katinas GS, Burioka N, Delyukov A, Gorgo Y, Zhao ZY, Weydahl A, Sothern RB, Siegelova J, Fiser B, Dusek J, Syutkina EV, Perfetto F, Tarquini R, Singh RB, Rhees B, Lofstrom D, Lofstrom P, Johnson PWC, Schwartzkopff O, International BIOCOS Study Group Cross-spectrally coherent ∼10.5- and 21-year biological and physical cycles, magnetic storms and myocardial infarctions. Neuroendocrinol Lett. 2000;21:233–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Halberg F, Cornélissen G, Regal P, Otsuka K, Wang ZR, Katinas GS, Siegelova J, Homolka P, Prikryl P, Chibisov SM, Holley DC, Wendt RW, Bingham C, Palm SL, Sonkowsky RP, Sothern RB, Pales E, Mikulecky M, Tarquini R, Perfetto F, Salti R, Maggioni C, Jozsa R, Konradov AA, Kharlitskaya EV, Revilla M, Wan CM, Herold M, Syutkina EV, Masalov AV, Faraone P, Singh RB, Singh RK, Kumar A, Singh R, Sundaram S, Sarabandi T, Pantaleoni GC, Watanabe Y, Kumagai Y, Gubin D, Uezono K, Olah A, Borer K, Kanabrocki EA, Bathina S, Haus E, Hillman D, Schwartzkopff O, Bakken EE, Zeman M. Chronoastrobiology: proposal, nine conferences, heliogeomagnetics, transyears, near-weeks, near-decades, phylogenetic and ontogenetic memories. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2004;58(Suppl 1):S150–S187. doi: 10.1016/s0753-3322(04)80025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berger S, Schweiger HG, Halberg F. Lighting schedule shifts prolong survival of enucleated Acetabularia. Progress in Clinical and Biological Research. 1990;341B:699–705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fritz MJ, Cornélissen G, Stoynev A, Ikonomov O, Minkova NK, Holte J, Halberg F. Blood pressure monitoring in a population of air traffic controllers working different shifts; Proc. XX Int. Conf. Chronobiol; Tel Aviv, Israel. June 21-25, 1991.p. 14.9. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Halberg J, Halberg E, Cornélissen G, Hillman D, de la Peña S Sanchez, Wu J, Otto S, Halberg F. Chronobiologically deviant blood pressure in shift working police on metropolitan street duty. Progress in Clinical and Biological Research. 1990;341B:281–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Halberg J, Halberg E, Cornélissen G, Wu JY, de la Peña S Sanchez, Hillman D, Zhou SL, Otto S, Halberg F. Cardiovascular rhythms, their adjustment to schedule change and shift work; Proc. 2nd Ann. IEEE Symp. on Computer-Based Medical Systems; Minneapolis. June 26-27, 1989; Washington DC: Computer Society Press; 1989. pp. 260–266. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Halberg F, Cornélissen G, International Womb-to-Tomb Chronome Initiative Group Resolution from a meeting of the International Society for Research on Civilization Diseases and the Environment (New SIRMCE Confederation) Brussels, Belgium, March 17-18, 1995: Fairy tale or reality? Medtronic Chronobiology Seminar #8, April 1995, 12 pp. text, 18 figures. http://www.msi.umn.edu/∼halberg/ [Google Scholar]

- 37.Otsuka K, Cornélissen G, Halberg F. Predictive value of blood pressure dipping and swinging with regard to vascular disease risk. Clinical Drug Investigation. 1996;11:20–31. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Otsuka K, Cornélissen G, Halberg F, Oehlert G. Excessive circadian amplitude of blood pressure increases risk of ischemic stroke and nephropathy. J Medical Engineering & Technology. 1997;21:23–30. doi: 10.3109/03091909709030299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cornélissen G, Halberg F, Bakken EE, Singh RB, Otsuka K, Tomlinson B, Delcourt A, Toussaint G, Bathina S, Schwartzkopff O, Wang ZR, Tarquini R, Perfetto F, Pantaleoni GC, Jozsa R, Delmore PA, Nolley E. 100 or 30 years after Janeway or Bartter, Healthwatch helps avoid “flying blind”. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2004;58(Suppl 1):S69–S86. doi: 10.1016/s0753-3322(04)80012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cornélissen G, Delcourt A, Toussaint G, Otsuka K, Watanabe Y, Siegelova J, Fiser B, Dusek J, Homolka P, Singh RB, Kumar A, Singh RK, Sanchez S, Gonzalez C, Holley D, Sundaram B, Zhao Z, Tomlinson B, Fok B, Zeman M, Dulkova K, Halberg F. Opportunity of detecting pre-hypertension: worldwide data on blood pressure overswinging. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2005;59(Suppl 1):S152–S157. doi: 10.1016/s0753-3322(05)80023-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cornélissen G, Halberg F, Otsuka K, Singh RB, Chen CH. Chronobiology predicts actual and proxy outcomes when dipping fails. Hypertension. 2007;49:237–239. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000250392.51418.64. doi:10.1161/01. HYP.0000250392.51418.64.

- 42.Halberg F, Cornélissen G, Halberg J, Schwartzkopff O. Pre-hypertensive and other variabilities also await treatment. Am J Medicine. 2007;120:e19–e20. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.02.045. doi:10.1016/ j.amjmed.2006.02.045.

- 43.Haus E, Smolensky MH. Biologic rhythms in the immune system. Chronobiology International. 1999;16(5):581–622. doi: 10.3109/07420529908998730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Halberg F, Cornélissen G, Katinas GS, Watanabe Y, Otsuka K, Maggioni C, Perfetto F, Tarquini R, Schwartzkopff O, Bakken EE.Conti A, Maestroni GJM, McCann SM, Sternberg EM, Lipton JM, Smith CC.Feedsidewards: intermodulation (strictly) among time structures, chronomes, in and around us, and cosmo-vasculoneuroimmunity. About ten-yearly changes: what Galileo missed and Schwabe found Neuroimmunomodulation (Proc. 4th Int. Cong. International Society for Neuroimmunomodulation, Lugano, Switzerland, September 29-October 2, 1999). Ann NY Acad Sci 2000917348–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Halberg F, Cornélissen G, Schack B, Wendt HW, Minne H, Sothern RB, Watanabe Y, Katinas G, Otsuka K, Bakken EE. Blood pressure self-surveillance for health also reflects 1.3-year Richardson solar wind variation: spin-off from chronomics. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2003;57(Suppl 1):58s–76s. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2003.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marques N, Marques MD, Marques RD, Marques LD, Maerz W, Halberg F. Delayed adjustment after transequatorial flight of circannual blood pressure variation in 4 family members. Policlinico Sez Med. 1995;102:209–214. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pope A.An Essay on Man Originally published 1732-1734. http://classiclit.about.com/library/bl-etexts/apope/bl-apope-essay-1.htm

- 48.Charron P.De la sagesse 1604742.David Douceur; Paris: Seconde reu. et augm. [Google Scholar]