Abstract

Biotin affects gene expression through a diverse array of cell signaling pathways. Previous studies provided evidence that cGMP-dependent signaling also depends on biotin, but the mechanistic sequence of cGMP regulation by biotin is unknown. Here we tested the hypothesis that the effects of biotin in cGMP-dependent cell signaling are mediated by nitric oxide (NO). Human lymphoid (Jurkat) cells were cultured in media containing deficient (0.025 nmol/L), physiological (0.25 nmol/L), and pharmacological (10 nmol/L) concentrations of biotin for 5 wk. Both levels of intracellular biotin and NO exhibited a dose-dependent relationship in regard to biotin concentrations in culture media. Effects of biotin on NO levels were disrupted by the NO synthase (NOS) inhibitor N-monomethyl-arginine. Biotin-dependent production of NO was linked with biotin-dependent expression of endothelial and neuronal NOS, but not inducible NOS. Previous studies revealed that NO is an activator of guanylate cyclase. Consistent with these previous observations, biotin-dependent generation of NO increased the abundance of cGMP in Jurkat cells. Finally, the biotin-dependent generation of cGMP increased protein kinase G activity. Collectively, the results of this study are consistent with the hypothesis that biotin-dependent cGMP signaling in human lymphoid cells is mediated by NO.

Introduction

The vitamin biotin plays an important role in gene regulation (1) in addition to its classical role as a covalently bound coenzyme for 5 carboxylases (2). More than 2000 biotin-dependent genes have been identified in human Jurkat lymphoma cells and HepG2 hepatocarcinoma cells (3–5); biotin-dependent genes have been clustered based on chromosomal location and molecular and biological functions (4,6–8). One common theme among these previous studies was that biotin deficiency is associated with activation of cell survival pathways in Jurkat cells and Drosophila melanogaster (9–11). Previous studies of biotin-dependent gene expression were not limited to quantification of transcript abundance but included investigations at the protein level, signaling cascades, and effects of biotin catabolites (3,5,9,12).

A number of biotin-dependent mechanisms of cell signaling have been identified. First, biotin binds covalently to histones (13,14); 11 biotinylation sites have been identified in histones H2A, H3, and H4 (15–18). Biotinylation of histones plays a role in chromatin structure and gene regulation (19). For example, biotinylation of lysine-12 in histone H4 represses genes coding for interleukin-2 and the sodium-dependent multivitamin transporter (12,19). Second, biotin deficiency causes nuclear translocation of the transcription factor nuclear factor-κB, mediating transcriptional activation of antiapoptotic genes (9). Third, biotin supplementation decreases expression of the sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum ATPase 3 gene, thereby enhancing the levels of Ca2+ in the cytoplasm and triggering the unfolded protein response (20). Fourth, biotin deficiency activates jun/fos signaling, activating AP1-dependent pathways (5). Fifth, signaling by transcription factors Sp1 and Sp3 depends on biotin (21). Sixth, the intermediate biotinyl-AMP activates soluble guanylate cyclase, increasing the synthesis of cGMP (22). This is associated with activation by cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG),3 increasing the transcription of genes coding for biotin-dependent carboxylases and holocarboxylase synthetase (22).

The early signals that mediate cGMP regulation by biotin are unknown. Here we tested the hypothesis that the effects of biotin in cGMP-dependent cell signaling are mediated by nitric oxide (NO). This hypothesis is founded in previous studies, providing evidence that NO (like biotin) activates soluble guanylate cyclase and thereby enhances the generation of cGMP (23,24).

In this study, the Jurkat lymphoma cell line was chosen as a cell model, because pathways of biotin signaling have been well characterized in this cell line and are similar to primary human lymphoid cells (3,4,9,25,26). Specifically, we determined whether the expression of NO synthases (NOS) and the synthesis of NO depend on biotin in Jurkat cells, whether biotin-dependent synthesis of NO increases the synthesis of cGMP, and whether biotin-dependent generation of cGMP increases PKG activity.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture.

Jurkat cell clone E6–1 (ATCC) was cultured in a humidified atmosphere in the following biotin-defined media for at least 5 wk prior to sample collection (25): 0.025 nmol/L of biotin (denoted “deficient”), 0.25 nmol/L of biotin (“physiological”), and 10 nmol/L of biotin (“pharmacological”). Biotin concentrations in media represent plasma concentrations in biotin-deficient individuals (>2 SD below the mean plasma concentration in normal subjects), normal subjects, and individuals taking a typical over-the-counter supplement providing 600 μg/d of biotin (i.e. 20 times the adequate intake) (27–29). Culture media were replaced with fresh media every 48 h. Media were prepared by using biotin-depleted fetal bovine serum (25); biotin concentrations in media were confirmed by avidin-binding assay (30) with modifications (25). The effect of biotin on cell growth was monitored by seeding 2 × 105 cells/mL of biotin-defined media and recounting the cells after 24 h of incubation.

Avidin blots of carboxylases.

The following mammalian carboxylases contain covalently bound biotin: acetyl-CoA carboxylases 1 and 2, pyruvate carboxylase, propionyl-CoA carboxylase (α chain), and 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase (α chain) (2). The abundance of biotinylated carboxylases is a reliable marker for intracellular biotin concentrations (2,25,31). Biotinylated carboxylases in cell extracts were resolved by PAGE and probed using streptavidin peroxidase (25). Binding of streptavidin to biotin was quantified by using gel densitometry (21).

NO.

Intracellular NO was quantified fluorometrically using 4-amino-5-methylamino-2′,7′-difluorofluorescein diacetate (Molecular Probes) as described (32). Control cultures were treated with 1 mmol/L NG-monomethyl-l-arginine (NMMA) for 1 h to inhibit NOS or with 1 mmol/L of the synthetic NO donor 3-morpholinosydnonimine for 1 h (33).

Expression of genes coding for NOS.

The following 3 forms of NOS have been detected in human cells: endothelial NOS (eNOS) and neuronal NOS (nNOS), both of which belong to the class of constitutively expressed NOS, and the inducible NOS (iNOS) (34,35). Here, the expression of genes encoding eNOS, nNOS, iNOS, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (control) was quantified using quantitative real-time PCR with SYBR Green 1 labeling in a iCycler iQ multicolor real-time detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories) (12,19). The following primers were used (Integrated DNA Technologies): 5′-CGG CAT CAC CAG GAA GAA GA-3′ and 5′-CAT GAG CGA GGC GGA GAT-3′ for eNOS (GenBank accession no. NM_000603); 5′-GGT GGA GAT CAA TAT CGC GGT T-3′ and 5′-CCG GCA GCG GTA CTC ATT CT-3′ for nNOS (GenBank accession no. NM_000620); 5′-CCA AGA GAA GAG AGA TTC CAT TGA A-3′ and 5′-TGA TTT TCC TGT CTC TGT CGC A-3′ for iNOS (GenBank accession no. AF068236); and 5′-TCC ACT GGC GTC TTC ACC-3′ and 5′-GGC AGA GAT GAC CCT TT-3′ for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GenBank accession no. NM_002046). Samples were incubated at 95°C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles, each consisting of denaturation at 95°C for 10 s and annealing plus extension at 55°C for 45 s. Fluorescence data were collected at the annealing temperature. The cycle threshold values generated were used to calculate the mRNA abundance for each sample (36).

cGMP.

NO is known to stimulate synthesis of cGMP (24,33,37). cGMP in cell lysates was quantified using the Cyclic GMP EIA kit (Cayman Chemical). 8-Bromo-guanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (8-Br-cGMP) is a nonhydrolysable analogue of cGMP; positive controls were cultured with 100 μmol/L 8-Br-cGMP for 20 min to validate the EIA kit (data not shown).

PKG activity.

cGMP is known to activate PKG (37). PKG activity in cell lysate was detected by PKG-dependent [32P]phosphorylation (γ-AT[32P]; specific activity = 370 GBq/mmol) of the peptide substrate BPDEtide (Arg-Lys-Ile-Ser-Ala-Ser-Glu-Phe-Asp-Arg-Pro-Leu-Arg) (38) and quantified by using a β counter. Cells treated with 100 μmol/L 8-Br-cGMP for 30 min served as positive controls; negative controls were produced by treating cells with 1 μmol/L of the PKG inhibitor KT5823 for 30 min.

Statistics.

Homogeneity of variances among groups was confirmed using Bartlett's test (39). Significance of differences among groups was tested by 1-way ANOVA. Fisher's protected least significant difference procedure was used for post hoc testing (39). StatView 5.0.1 (SAS Institute) was used to perform all calculations. Differences were considered significant if P < 0.05. Data are expressed as means ± SD.

Results

Biotin-dependent carboxylases.

Biotinylation of carboxylases was dose dependent upon the levels of biotin in culture media in Jurkat cells, confirming that treatment was effective. The abundance of biotinylated pyruvate carboxylase increased by 80% in cells cultured in medium containing 10 nmol/L biotin compared with physiological controls (Fig. 1); no biotinylated pyruvate carboxylase was detectable in cells cultured in medium containing 0.025 nmol/L biotin. Likewise, the abundance of biotinylated α-chains of propionyl-CoA carboxylase and 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase depended on biotin in culture media. Note that the α-chains of propionyl-CoA carboxylase (molecular mass = 80 kDa) and 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase (molecular mass = 83 kDa) were poorly resolved on the polyacrylamide gels used here and, therefore, were pooled for analysis by gel densitometry. The abundance of biotinylated propionyl-CoA carboxylase plus 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase decreased by 94% in cells cultured in medium containing 0.025 nmol/L biotin (Fig. 1) but increased by 40% in cells cultured in medium containing 10 nmol/L biotin compared with physiological controls. Acetyl-CoA carboxylases 1 and 2 were not detectable in Jurkat cell extracts, consistent with previous studies (25). Cell growth did not differ among the treated cells; when 2 × 105 cells were seeded per mL of medium and recounted after 24 h of incubation, there was an 81 ± 14% increase in the number of cells cultured in biotin-deficient medium, a 68 ± 20% increase in those in physiological medium, and an 82 ± 28% increase in cells cultured in pharmacological medium (n = 4/group).

FIGURE 1 .

The abundance of holocarboxylases in Jurkat cells depends on the concentration of biotin in culture media. Cells were cultured in biotin-defined media for 5 wk. Biotinylated carboxylases were quantified using streptavidin blots and gel densitometry; equal amounts of protein were loaded (20 μg/lane). Values are means ± SD, n = 3. Means for each variable without a common letter differ, P < 0.01. Abbreviations: MCC, 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase; PC, pyruvate carboxylase; PCC, propionyl-CoA carboxylase.

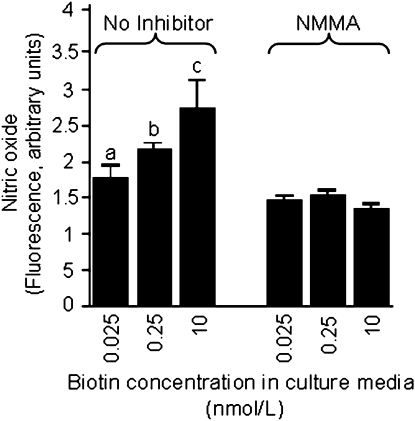

Synthesis of NO.

The concentration of NO in Jurkat cell extracts was dose dependent upon the levels of biotin in culture media. The concentration of NO decreased by 18% in cells cultured in medium containing 0.025 nmol/L biotin compared with physiological controls (Fig. 2); the concentration of NO increased by 27% in cells cultured in medium containing 10 nmol/L biotin compared with physiological controls. Differences among treatment groups were abolished if biotin-defined cells were treated with the NOS inhibitor NMMA (Fig. 2) or the NO donor SNI-1 (data not shown).

FIGURE 2 .

The concentration of NO in Jurkat cell extracts depends on the concentration of biotin in culture media. Cells were cultured in biotin-defined media for 5 wk. NO in whole cell extracts from 5 × 105 cells was quantified fluorometrically. Controls were treated with the NOS inhibitor NMMA. Values are means ± SD, n = 3. Means for each variable without a common letter differ, P < 0.01. Cells without NMMA were not compared to NMMA-treated cells.

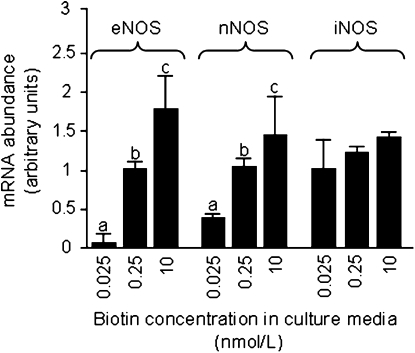

Effects of biotin on NO levels were mediated at least partially by biotin-dependent expression of eNOS and nNOS. The abundances of mRNA encoding eNOS and nNOS were dose dependent upon the levels of biotin in culture media (Fig. 3). The abundance of eNOS mRNA decreased by 95% in cells cultured in medium containing 0.025 nmol/L biotin compared with physiological controls; the abundance of eNOS mRNA increased by 78% in cells cultured in medium containing 10 nmol/L biotin compared with physiological controls. Likewise, the abundance of nNOS mRNA decreased by 64% in cells cultured in medium containing 0.025 nmol/L biotin compared with physiological controls; the abundance of nNOS mRNA increased by 41% in cells cultured in medium containing 10 nmol/L biotin compared with physiological controls. In contrast, the abundance of iNOS mRNA was not affected by biotin (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3 .

The abundance of transcripts coding for eNOS and nNOS in Jurkat cells depends on the concentration of biotin in culture media. Cells were cultured in biotin-defined media for 5 wk. mRNA coding for eNOS, nNOS, and iNOS was quantified by real-time PCR. Values are means ± SD, n = 3. Means for each variable without a common letter differ for the same transcript, P < 0.01.

Signaling by cGMP and PKG.

The activation of NO synthesis by biotin coincided with increased cGMP levels in Jurkat cells. Concentrations of cGMP differed among all treated cells and were 1.6 ± 0.05 nmol·L−1·mg of protein−1 in those cultured in biotin-deficient medium, 1.9 ± 0.05 nmol·L−1·mg of protein−1 in cells from physiological medium, and 2.3 ± 0.2 nmol·L−1·mg of protein−1 in cells from pharmacological medium (P < 0.01; n = 3/group).

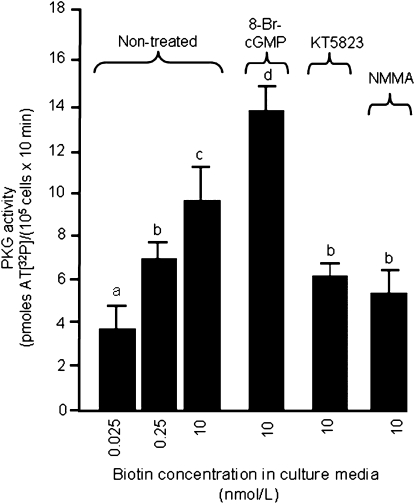

PKG activities paralleled the biotin-dependent synthesis of cGMP, as judged by phosphorylation of the synthetic PKG substrate BPDEtide in response to incubation with cell extracts. Phosphorylation of BPDEtide decreased by 16% in cells cultured in medium containing 0.025 nmol/L biotin compared with physiological controls (Fig. 4); phosphorylation of BPDEtide increased by 35% in cells cultured in medium containing 10 nmol/L biotin compared with physiological controls. PKG activity increased by 64% in 8-Br-cGMP-treated, biotin-matched (10 nmol/L) cells (positive controls); PKG activity decreased by 25 and 40% in cells treated with KT5823 and NMMA, respectively, compared with biotin-matched inhibitor-free cells (negative control). Patterns were similar for positive and negative controls at biotin concentrations of 0.025 nmol/L and 0.25 nmol/L (data not shown).

FIGURE 4 .

Phosphorylation of BPDEtide by PKG depends on the concentration of biotin in Jurkat cells. Cells were cultured in biotin-defined media for 5 wk. PKG activity in cell lysates was measured by the γ-AT[32P]-mediated phosphorylation of the peptide BPDEtide. Values are means ± SD, n = 3. Means for each variable without a common letter differ, P < 0.01.

Discussion

Previous studies provide convincing evidence that biotin and its metabolite biotinyl-AMP activate soluble guanylate cyclase, increasing the synthesis of cGMP (22,40,41). Subsequently, cGMP activates PKG, thereby increasing the transcription of genes coding for biotin-dependent carboxylases and holocarboxylase synthetase (22). However, the initial biotin-dependent steps in the cGMP pathway were not elucidated. The study presented here fills some important gaps by offering novel insights into the biotin-dependent regulation of cGMP and PKG signaling. Importantly, evidence is provided that the generation of NO depends on biotin in human lymphoid cells and that biotin-dependent generation of NO is mediated by increased expression of eNOS and nNOS. Effects of biotin are gene specific, given that iNOS mRNA levels were not altered by biotin. Biotin-dependent generation of NO increased the abundance of cGMP, consistent with previous studies revealing that NO is an activator of guanylate cyclase (23,24). Ultimately, the biotin-dependent generation of cGMP increased PKG activity. Collectively, this study is consistent with the hypothesis that biotin-dependent synthesis of NO contributes to cGMP signaling in human lymphoid cells.

Effects of biotin on the synthesis of NO are physiologically important, based on the following lines of reasoning. First, NO is a key regulator of numerous biological processes, including vasodilatation, synaptic plasticity, and immune defense (34). Importantly, NO affects the cellular abundance of the ubiquitous second messengers cGMP and cAMP (33,37), triggering downstream effects on the activity of various transcription factors and the expression of numerous genes. This is consistent with the large number of biotin-dependent genes discovered in previous studies (3–5). Second, the studies described here were conducted using biotin at concentrations that are physiologically relevant (25,27–29).

There are still some minor uncertainties associated with this regulatory pathway. First, Leon-Del-Rio et al. (22,42) suggested that holocarboxylase synthetase plays a critical role in biotin-dependent signaling by cGMP and PKG. A possible involvement of holocarboxylase synthetase in the regulation of NO and NOS has not been investigated in this study. Previous studies in our laboratory and by others revealed that holocarboxylase synthetase mediates the binding of biotin to histones (7,43,44) and that biotinylation of histones plays an important role in gene regulation (7,8,12,19). We speculate that histone biotinylation by holocarboxylase synthetase might mediate some of the effects of biotin on NOS expression.

Second, the mechanism by which biotin increases the expression of eNOS and nNOS is unknown. We speculate that one or more of the many biotin-dependent transcription factors participate in the regulation of the 2 genes (5,9,21). In addition, we propose that decreased expression of the sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum ATPase 3 in biotin-supplemented cells decreases the transport of Ca2+ from the cytoplasm into the endoplasmic reticulum, leading to increased concentrations of Ca2+ in the cytoplasm (20). Cytoplasmic free Ca2+ enhances the production of NO in Jurkat cells (45). In this study, effects of biotin on the abundance of mRNA coding for eNOS and nNOS were greater than the effects of biotin on NO levels. We cannot exclude the possibility that the unaltered abundance of iNOS mRNA in biotin-defined cells is responsible for this difference in effect.

This study is consistent with the hypothesis that some of the effects of biotin in cGMP and PKC signaling are mediated by NO and NOS. The proposed mechanisms tie in well with other biotin-dependent cell signals, e.g. transcription factor activity, calcium flux, and histone biotinylation. Given the central regulatory role of NO in metabolism, we anticipate that the observations presented here will lead to new discoveries regarding the roles of biotin in cell signaling.

Supported in part by funds provided through the Hatch Act. A contribution of the University of Nebraska Agricultural Research Division. Additional support was provided by NIH grants DK063945, DK077816, and ES015206, USDA grant 2006-35200-17138, and by National Science Foundation Experimental Program to Stimulate Competitive Research grant EPS-0701892.

Author disclosures: R. Rodriguez-Melendez and J. Zempleni, no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations used: 8-Br-cGMP, 8-bromo-guanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate; NMMA, NG-monomethyl-L-arginine; NO, nitric oxide; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; nNOS, neuronal nitric oxide synthase; PKG, cGMP-dependent protein kinase.

References

- 1.Zempleni J. Uptake, localization, and noncarboxylase roles of biotin. Annu Rev Nutr. 2005;25:175–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Camporeale G, Zempleni J. Biotin. In: Bowman BA, Russell RM, editors. Present knowledge in nutrition. 9th ed. Washington, DC: International Life Sciences Institute; 2006. p. 314–26.

- 3.Rodriguez-Melendez R, Lewis B, McMahon RJ, Zempleni J. Diaminobiotin and desthiobiotin have biotin-like activities in Jurkat cells. J Nutr. 2003;133:1259–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiedmann S, Rodriguez-Melendez R, Ortega-Cuellar D, Zempleni J. Clusters of biotin-responsive genes in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Nutr Biochem. 2004;15:433–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodriguez-Melendez R, Griffin JB, Sarath G, Zempleni J. High-throughput immunoblotting identifies biotin-dependent signaling proteins in HepG2 hepatocarcinoma cells. J Nutr. 2005;135:1659–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodriguez-Melendez R, Griffin JB, Zempleni J. The expression of genes encoding ribosomal subunits and eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5A depends on biotin and bisnorbiotin in HepG2 cells. J Nutr Biochem. 2006;17:23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Camporeale G, Giordano E, Rendina R, Zempleni J, Eissenberg JC. Drosophila holocarboxylase synthetase is a chromosomal protein required for normal histone biotinylation, gene transcription patterns, lifespan and heat tolerance. J Nutr. 2006;136:2735–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith EM, Hoi JT, Eissenberg JC, Shoemaker JD, Neckameyer WS, Ilvarsonn AM, Harshman LG, Schlegel VL, Zempleni J. Feeding Drosophila a biotin-deficient diet for multiple generations increases stress resistance and lifespan and alters gene expression and histone biotinylation patterns. J Nutr. 2007;137:2006–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodriguez-Melendez R, Schwab LD, Zempleni J. Jurkat cells respond to biotin deficiency with increased nuclear translocation of NF-κB, mediating cell survival. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 2004;74:209–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Landenberger A, Kabil H, Harshman LG, Zempleni J. Biotin deficiency decreases life span and fertility but increases stress resistance in Drosophila melanogaster. J Nutr Biochem. 2004;15:591–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Griffin JB, Zempleni J. Biotin deficiency stimulates survival pathways in human lymphoma cells exposed to antineoplastic drugs. J Nutr Biochem. 2005;16:96–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gralla M, Camporeale G, Zempleni J. Holocarboxylase synthetase regulates expression of biotin transporters by chromatin remodeling events at the SMVT locus. J Nutr Biochem. 2008;19:400–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hymes J, Fleischhauer K, Wolf B. Biotinylation of histones by human serum biotinidase: assessment of biotinyl-transferase activity in sera from normal individuals and children with biotinidase deficiency. Biochem Mol Med. 1995;56:76–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stanley JS, Griffin JB, Zempleni J. Biotinylation of histones in human cells: effects of cell proliferation. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:5424–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Camporeale G, Shubert EE, Sarath G, Cerny R, Zempleni J. K8 and K12 are biotinylated in human histone H4. Eur J Biochem. 2004;271:2257–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kobza K, Camporeale G, Rueckert B, Kueh A, Griffin JB, Sarath G, Zempleni J. K4, K9, and K18 in human histone H3 are targets for biotinylation by biotinidase. FEBS J. 2005;272:4249–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chew YC, Camporeale G, Kothapalli N, Sarath G, Zempleni J. Lysine residues in N- and C-terminal regions of human histone H2A are targets for biotinylation by biotinidase. J Nutr Biochem. 2006;17:225–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kobza K, Sarath G, Zempleni J. Prokaryotic BirA ligase biotinylates K4, K9, K18 and K23 in histone H3. BMB Rep. 2008;41:310–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Camporeale G, Oommen AM, Griffin JB, Sarath G, Zempleni J. K12-biotinylated histone H4 marks heterochromatin in human lymphoblastoma cells. J Nutr Biochem. 2007;18:760–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Griffin JB, Rodriguez-Melendez R, Dode L, Wuytack F, Zempleni J. Biotin supplementation decreases the expression of the SERCA3 gene (ATP2A3) in Jurkat cells, thus, triggering unfolded protein response. J Nutr Biochem. 2006;17:272–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Griffin JB, Rodriguez-Melendez R, Zempleni J. The nuclear abundance of transcription factors Sp1 and Sp3 depends on biotin in Jurkat cells. J Nutr. 2003;133:3409–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Solorzano-Vargas RS, Pacheco-Alvarez D, Leon-Del-Rio A. Holocarboxylase synthetase is an obligate participant in biotin-mediated regulation of its own expression and of biotin-dependent carboxylases mRNA levels in human cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:5325–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pilz RB, Suhasini M, Idriss S, Meinkoth JL, Boss GR. Nitric oxide and cGMP analogs activate transcription from AP-1-responsive promoters in mammalian cells. FASEB J. 1995;9:552–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pilz RB, Casteel DE. Regulation of gene expression by cyclic GMP. Circ Res. 2003;93:1034–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manthey KC, Griffin JB, Zempleni J. Biotin supply affects expression of biotin transporters, biotinylation of carboxylases, and metabolism of interleukin-2 in Jurkat cells. J Nutr. 2002;132:887–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodriguez-Melendez R, Camporeale G, Griffin JB, Zempleni J. Interleukin-2 receptor γ-dependent endocytosis depends on biotin in Jurkat cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;284:C415–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mock DM, Lankford GL, Mock NI. Biotin accounts for only half of the total avidin-binding substances in human serum. J Nutr. 1995;125:941–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.NRC. Dietary reference intakes for thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, vitamin B6, folate, vitamin B12, pantothenic acid, biotin, and choline. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1998. [PubMed]

- 29.Zempleni J, Helm RM, Mock DM. In vivo biotin supplementation at a pharmacologic dose decreases proliferation rates of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells and cytokine release. J Nutr. 2001;131:1479–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mock DM. Determinations of biotin in biological fluids. In: McCormick DB, Suttie JW, Wagner C, editors. Methods in enzymology. New York: Academic Press; 1997. p. 265–75. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Mock DM, Mock NI. Lymphocyte propionyl-CoA carboxylase is an early and sensitive indicator of biotin deficiency in rats, but urinary excretion of 3-hydroxypropionic acid is not. J Nutr. 2002;132:1945–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lopez-Figueroa MO, Caamano C, Morano MI, Ronn LC, Akil H, Watson SJ. Direct evidence of nitric oxide presence within mitochondria. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;272:129–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adam L, Bouvier M, Jones TLZ. Nitric oxide modulates β2-adrenergic receptor palmitoylation and signaling. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:26337–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klein C. Nitric oxide and the other cyclic nucleotide. Cell Signal. 2002;14:493–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hamad AM, Clayton A, Islam B, Knox AJ. Guanylyl cyclases, nitric oxide, natriuretic peptides, and airway smooth muscle function. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;285:L973–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)). Methods. 2001;25:402–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hofmann F, Ammendola A, Schlossmann J. Rising behind NO: cGMP-dependent protein kinases. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:1671–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gertzberg N, Clements R, Jaspers I, Ferro TJ, Neumann P, Flescher E, Johnson A. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced activating protein-1 activity is modulated by nitric oxide-mediated protein kinase G activation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2000;22:105–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.SAS Institute. StatView reference. 3rd ed. Cary (NC): SAS Publishing; 1999.

- 40.Vesely DL. Biotin enhances guanylate cyclase activity. Science. 1982;216:1329–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vesely DL, Wormser HC, Abramson HN. Biotin analogs activate guanylate cyclase. Mol Cell Biochem. 1984;60:109–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leon-Del-Rio A. Biotin-dependent regulation of gene expression in human cells. J Nutr Biochem. 2005;16:432–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Narang MA, Dumas R, Ayer LM, Gravel RA. Reduced histone biotinylation in multiple carboxylase deficiency patients: a nuclear role for holocarboxylase synthetase. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Camporeale G, Zempleni J, Eissenberg JC. Susceptibility to heat stress and aberrant gene expression patterns in holocarboxylase synthetase-deficient Drosophila melanogaster are caused by decreased biotinylation of histones, not of carboxylases. J Nutr. 2007;137:885–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Srivastava RK, Sollott SJ, Khan L, Hansford R, Lakatta EG, Longo DL. Bcl-2 and Bcl-X(L) block thapsigargin-induced nitric oxide generation, c-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase activity, and apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5659–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]