Abstract

Previous cell cycle studies have been based on cell-nuclear proliferation only. Eukaryotic cells, however, have double membranes-bound organelles, such as the cell nucleus, mitochondrion, plastids and single-membrane-bound organelles such as ER, the Golgi body, vacuoles (lysosomes) and microbodies. Organelle proliferations, which are very important for cell functions, are poorly understood. To clarify this, we performed a microarray analysis during the cell cycle of Cyanidioschyzon merolae. C. merolae cells contain a minimum set of organelles that divide synchronously. The nuclear, mitochondrial and plastid genomes were completely sequenced. The results showed that, of 158 genes induced during the S or G2-M phase, 93 were known and contained genes related to mitochondrial division, ftsZ1-1, ftsz1-2 and mda1, and plastid division, ftsZ2-1, ftsZ2-2 and cmdnm2. Moreover, three genes, involved in vesicle trafficking between the single-membrane organelles such as vps29 and the Rab family protein, were identified and might be related to partitioning of single-membrane-bound organelles. In other genes, 46 were hypothetical and 19 were hypothetical conserved. The possibility of finding novel organelle division genes from hypothetical and hypothetical conserved genes in the S and G2-M expression groups is discussed.

Key words: cell cycle, microarray, mitochondria–plastid division genes, organelle division genes, Cyanidioschyzon merolae

1. Introduction

Cell cycle progression is regulated and controlled by a range of mechanisms including protein modification, targeted proteolytic degradation and cell cycle-specific transcription.1 Genes whose expression levels peak at a specific event of the cell cycle are often required to regulate the processes that occur at these stages.2 In the budding yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, of ∼6000 genes, ∼400–800 have transcript levels that oscillate during the cell cycle,3,4 whereas in the fission yeast, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, of ∼5000 genes, ∼400–750 such genes have been found.5–7 In human cancer cell line (HeLa), among a total of 22 000 genes, >1000 are regulated by the cell cycle.8,9 These studies of periodic genes suggest that only the 112th orthologue group is cyclic and common among human cells, as well as budding and fission yeast cells.10 Those taking part in the cell cycle progression include the cyclin B homologs, CDC5, SCH9, DSK2 and ZPR1. Proteins involved in DNA replication include histones, some checkpoint kinases and some proteins regulating DNA damage and repair. Many groups of genes related to translation and other metabolic processes are also cyclic in all three organisms.10 In Arabidopsis thaliana, of ∼25 000 genes, ∼500 cell cycle regulated genes have been identified.11 In tobacco BY-2, of the ∼10 000 genes that could be analyzed by cDNA–AFLP-based gene profiling, ∼1300 were regulated by the cell cycle.12

Cell proliferation needs division and partitioning of organelles such as mitochondria and plastids. However, there is no information on periodic gene expressions with respect to mitochondrial division in yeast or animal cells. Furthermore, in the research of the periodic expression in A. thaliana or tobacco BY-2, mitochondrial and plastid divisions were not shown. Mammalian, plant and yeast cells contain many organelles whose divisions occur at random, cannot be synchronized and have shapes that are very diverse and complicated.13 Therefore, genes related to such organelles are not reflected in microarray analyses of the cell cycle in higher organisms. In previous cell cycle studies, the analysis has been based on nuclear proliferation only. Eukaryotic cells, however, have double-membrane-bound organelles, such as the nucleus, mitochondria and plastids, and single-membrane-bound organelle such as ER, the Golgi body, vacuoles (lysosomes) and microbodies. Organelle proliferation is very important for cell functions, as well as differentiation and cell division. However, there are few studies that have investigated the organelle proliferation cycle.

The unicellular red alga Cyanidioschyzon merolae has advantages for investigating organelle proliferation as it has a minimum set of organelles,14–16 and organelle division can be synchronized by a light/dark cycle.17 The mitochondrial and plastid division requires the FtsZ,18,19 the Dynamin20,21 and the MD/PD rings.22,23 Northern blot analysis has shown that each transcriptional level of ftsz1 for mitochondrial division, and ftsZ2 for the plastid division, has a peak per cell cycle before each division.18 Moreover, nuclear, mitochondrial and plastid genomes of C. merolae have completely been sequenced.24–27 As the nucleus genome 4775 ORF's coding protein includes 27 introns only, newly designed proteins by alternative splicing are few; therefore, the functioning protein is directly identified as the same gene. Furthermore, most ORFs do not have paralogues.24 We thought that novel organelle division-related genes like ftsZ genes could be found by genome-wide transcriptome of the cell cycle.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Synchronous culture and fluorescence microscopy

Cyanidioschyzon merolae 10D-14 were synchronized according to the method discussed in Suzuki et al.17 Cells were cultured in 2× Allen's medium at pH 2.3. Flasks were shaken under continuous light (40 W/m2) at 42°C. The cells were sub-cultured to <107 cells/mL, and then synchronized by subjecting them to a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle at 42°C while the medium was aerated. For the observation of DNA, the cells were fixed in 1% glutaraldehyde diluted with 2× Allen's medium and stained with 1 µg/mL DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole phosphate). Images were viewed using an epifluorescence microscope (BX51; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with 3CCD digital camera (C77780; Hamamatsu Photonics, Tokyo, Japan) under ultraviolet excitation. The cultures were harvested every 2 h, and indexes of organelle division were counted.

2.2. Reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction

Cells were collected by centrifuging at 1400g for 3 min and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Nuclear acid isolation buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH7.6, 100 mM EDTA, 300 mM NaCl, 4% SDS, 2% N-lauroylsarcosine sodium salt) pre-warmed at 60°C was added to the frozen cell pellets. The lysate was added to an equal volume of PCI (phenol:chloroform:isoamylalcohol = 25:24:1). The aqueous phase was recovered by centrifuging at 15 000g for 5 min at 4°C and re-extracted using PCI. Total nucleus acid was precipitated by adding an equal volume of isopropanol and recovered by centrifugation at 15 000g for 15 min at 4°C. The pellet was melted in DNase I solution (0.1 U/μL DNase I, RNase Free; Roshe, 0.4 U/μL RNase Inhibitor; Sigma, 10 mM DTT, 10 mM MgCl2) and incubated for 45 min at 37°C. Total RNA was precipitated by adding an equal volume of isopropanol and recovered by centrifugation at 15 000g for 15 min at 4°C.

The RNA samples were reverse-transcribed in 20 µL of the reaction mix comprising 1 µL of Reverse Transcriptase XL (AMV; TaKaRa Bio Inc.), 50 ng/μL of oligo(dT) primer (Novagen), 2 U/μL of RNase inhibitor and 0.5 mM dNTP mixture (TaKaRa Bio Inc.). The reaction conditions were as follows: 10 min at 25°C, 45 min at 42°C and 10 min at 70°C. Absence of genomic DNA contamination was confirmed by PCR in all the total RNA samples. In the RT–PCR assay, cDNA of ftsZ2-1, ftsZ2-2 and the housekeeping gene ef-1a were amplified by 22 PCR cycles. The quantity of PCR products was analyzed by electrophoresis in 2% agarose gel. The primers used in PCR were described in Supplementary Table S1.

All real-time PCR assay kits were purchased from Applied Biosystems, and utilized according to the manufacturer's instructions. PCR amplification of each sample was carried out using 7.5 µL of Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), 5.5 µL of distilled water, 0.3 µL of forward and reverse primer solutions (10 µM each) and 1.7 µL of cDNA template (25 ng/mL). For signal detection, an ABI Prism 7500 fast sequence detector was programmed to an initial step of 10 min at 95°C, followed by 50 thermal cycles of 10 s at 95°C and 30 s at 60°C. The mean Quantity values (Qty) were calculated from the cycle threshold (Ct) values using the SDS 3.1 software by the standard curve method (Applied Biosystems). The expression of each target gene was normalized by that of ef-1a. From the mean Qty values of the target gene and ef-1a, we calculated the relative values to show the changes in gene expression with the multiplication mean as standard 1 as follows:

All reactions were performed in triplicate for measurement of the mean Qty in each sample and in duplicate for the standard curve. The PCR primer sequences are described in Supplementary Table S1.

2.3. Microarray manufacture

On the basis of the annotated C. merolae genome, we ordered synthesis of the ORF-specific oligonucleotides for Sigam Genosys and searched a unique 50-mer sequence for each of the 4586 ORF-coding protein genes (>96% of the ORFs in the nucleus genome). In brief, 50-mer sequences were first selected from ORF sequences based on a set of criteria that included Tm of 75 ± 10°C. Ninety-eight percent of the ORFs-specific oligonucleotides were selected among 1.5 kb from the 3′ end of the ORF. All the oligonucleotides were synthesized (Sigma Genosys), resuspended into 30% (v/v) DMSO and spotted onto poly-lysine–coated glass slides, using a spotting machine (SPBIO, Hitachi Software Engineering Co.). Methods of spotting were referred to the protocol of the Brown lab in Stanford University (http://cmgm.stanford.edu/pbrown/). Spotted microarray glasses were stored at room temperature in a dry cabinet for later use.

2.4. aRNA fluorescence labeling

Amino-allyl aRNA was synthesized using an Amino-Allyl MessageAmp aRNA Kit (Ambion, TX, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. It was transcribed in the presence of amino-allyl dUTP by templating double-strand cDNA synthesized using T7 oligo(dT) primer. Cy3- or Cy5-congugated aRNA was prepared by mixing Cy (GE Healthcare 1vial/45ul dissolved in DMSO) and 5 µg amino-allyl aRNA in coupling buffer (0.1 M NaHCO3, pH 9.0), incubating for 60 min at 40°C and then purified by a Bio Spin-Column (Bio-Rad) and microcon-YM30 spin-column (Millipore).

2.5. Microarray hybridization

Hybridization solution (5× SSC, 0.5% SDS, 4× Denhalt's solution, 10% formamid, 100 ng/μL Salmon Sperm DNA) and Cy3-congugated aRNA was hybridized to spotted microarray slides covered with a coverglass (Matsunami) in a slide hybridization chamber (Sigma) for 18 h at 55°C. Hybridized slides were washed in 1× SSC/0.03% SDS for 6 min at 45°C, followed by 0.2× SSC for 5 min and 0.05× SSC for 4 min, and then spin-dried before scanning.

2.6. Microarray data mining

Microarray slides were scanned using an FLA-8000 scanner (FujiFilm) at a wavelength of 532 and 635 nm in the 5-μm resolution. Gene Spot signals on microarray images were measured by the microarray analyzing software ArrayGauge Ver.2 (FujiFilm). As for data at each time point, it was subtracted the average value from 2 to 50 h. Data were analyzed by microarray data mining software AVADIS (Hitachi software). To collect cell cycle expression genes, hierarchical clustering was performed. In hierarchical clustering analysis for gene direction, the distance metric and linkage rule were set for Euclidean and Complete, respectively. Cell cycle regulated genes collected by hierarchical clustering analysis were separated into four groups by K-means clustering. In K-Means clustering analysis for gene direction, distance metric and four number of clusters and numbers of iterations were set for Euclidean, 4 and 50, respectively.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Synchronization of the cell nucleus, mitochondrial and plastid divisions in C. merolae

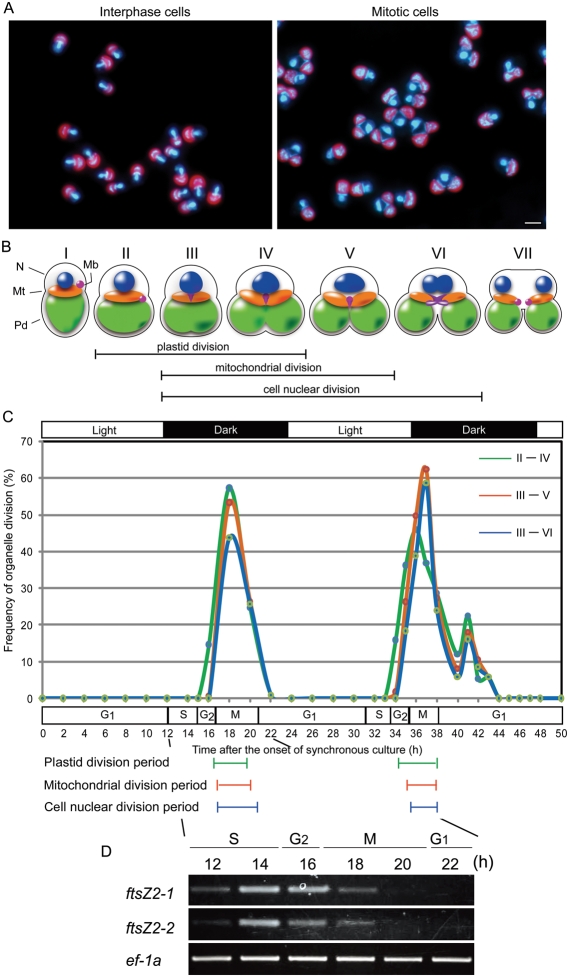

Organelle division in C. merolae can be synchronized by a light dark cycle.17 Fig. 1A shows typical interphase and mitotic cells fixed at 8 and 18 h after the start of the synchronous culture. Interphase cells had one cell nucleus, a mitochondrial nucleus (nucleoid) and one spherical plastid, whereas mitotic cells contained a dividing cell nucleus, mitochondrion and plastid. On the basis of the previous and present observations, these divisions are illustrated relative to the cell cycle in Fig. 1B. The type I cell is in the G1-phase in which the nucleus is spherical, the mitochondrion flat and the plastid (chloroplast) cup-shaped (Fig. 1BI). Type II cells in the G2-phase contain a cell nucleus that is larger than type I, and a plastid whose volume is increased, indicating that division has been initiated (Fig. 1BII). In type III cells, the M-phase is initiated and the nucleus begins to form a football-like structure. Mitochondrial division begins and plastid division is more advanced. The microbody has moved to the region of mitochondrial division (Fig. 1BIII). In type IV cells, organelle divisions are more advanced (Fig. 1BIV). In type V cells, the mitochondrion remains as a single body and its division is still not finished, while the plastid has divided in two (Fig. 1BV). In type VI cells, the cell nucleus is dividing without chromosome condensation, the mitochondrion dividing prior to cell nuclear separation, and the microbody is dividing (Fig. 1BVI). In type VII, cytokinesis has been initiated after cell nuclear separation and microbody division (Fig. 1AVII). Therefore, types II–IV, III–V and III–VI cells show plastid, mitochondrial and cell nuclear division, respectively.

Figure 1.

Synchronous culture of C. merolae. (A) Images of typical interphase and mitotic cells. The DNA of a cell nucleus, a mitochondrion and a plastid emit white-blue fluorescence stained with DAPI and plastids emit red-autofluorescent. Bar: 2 µm. (B) Schematic models for organelle division during the cell cycle. Plastid division is shown between II and IV. Mitochondrial division is shown between III and V. Chromosome segregation is shown between III and VI. N, nucleus; Mt, mitochondrion; Pd, plastid; Mb, microbody. (C) Frequencies of organelle division. The top bar indicates the 12-h light/12-h dark photoperiods and the lower bar indicates cell cycle phase. Green, orange and blue carve show the index of plastid division indicated II–IV of (B), index of mitochondrial division indicated III–V of (B) or mitotic index indicated III–VI of (B), respectively. Color bars under the graph show major periods of organelle division, green, orange and blue indicates plastid, mitochondrion and nucleus, respectively. (D) RT–PCR assay during the first synchronized organelle division.

In synchronized culture, the cells were taken at 2 h intervals for a period of 50 h to ensure that at least two complete cell cycles were covered. Fig. 1C shows the index of cell nuclear, mitochondrial and plastid division, counted according to shape of the cell in Fig 1B. The main period of plastid division took 4 h, from 16 to 20 h and from 34 to 38 h (Fig. 1C). Mitochondrial division took place about 3.5 h, from 17 to 20.5 h and from 35 to 38 h, and nuclear division took place about 3.5 h, from 17 to 21 h and 35.5 to 38 h (Fig. 1C). The mitotic cycle phase was defined by observing the change in nuclear morphology. An increase in cell nuclear volume in the S-phase occurred from 12 to 15 h and from 31 to 34 h, and the cell nuclear division period (M-phase) occurred from 17 to 21 h and 35.5 to 38 h (Fig. 2C).

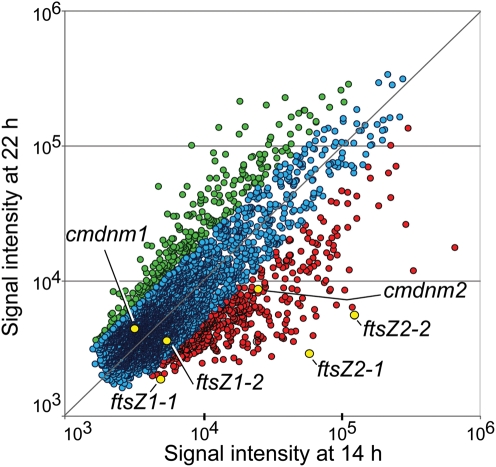

Figure 2.

Scattered plot of transcriptional levels at 14 and 22 h in microarray analysis. The color circle indicated green <0.5-fold ≤ blue < 2-fold ≤ red. The values, 0.5 and 2, is the ratio of (signal at 14 h/signal at 22 h). Red, blue and green circles showed the genes were induced, constantly expressed and suppressed at 14 h, respectively. The yellow circles indicated ftsZ1-1, ftsZ1-2, ftsZ2-1, ftsZ2-2, cmdnm1 and cmdnm2. In addition to ftsZ2-1and ftsZ2-2, cmdnm2 and ftsZ1-1 were confirmed to be induced at 14 h. ftsZ1-2 and cmdnm1 did not show changes remarkably.

To confirm whether organelle division genes were induced in the synchronous culture, the change of transcriptional level ftsZ2 was analyzed by the RT–PCR assay at 12, 14, 16, 18, 20 and 22 h during the first cell division. ftsZ2, which is involved in plastid division, is an excellent marker for timing-specific gene expression.18 There are two paralogues of ftsZ2, ftsZ2-1/CMS361C and ftsZ2-2/CMS004C, each transcriptional level of ftsZ2-1 and ftsZ2-2 had a peak at 14 h, and then was lowest at 22 h (Fig. 1D). This result showed that most genes related to organelle division were expressed synchronously at 14 h in late S-phase. Therefore, microarray analysis was performed in the synchronous culture.

3.2. Detection of organelle division genes by microarray analysis

Microarray of C. merolae can identify 4586 genes for >96% of all known and predicted C. merolae gene-coding proteins. We tested whether the microarray could analyze the induction of organelle division genes. Microarray analysis between 14 and 22 h showed that ftsZ2-1 and ftsZ2-2 were strongly induced at 14 h (Fig. 2). Moreover, expressions of cmdnm2 involved in plastid division, and ftsZ1-1 involved in mitochondrial division, were stronger at 14 h compared with 22 h. ftsZ1-2 did not show a remarkable induction, but its expression was slightly stronger at 14 h compared with 22 h. Expression of cmdnm1 that was constantly expressed during the cell cycle20 showed a constant expression and was found to be near the diagonal showing constant expression. These results were consistent with previous experiments and showed that the microarray could analyze time-specific gene expression.

3.3. Identification of genes induced during S-, G2- and M-phases by microarray analysis

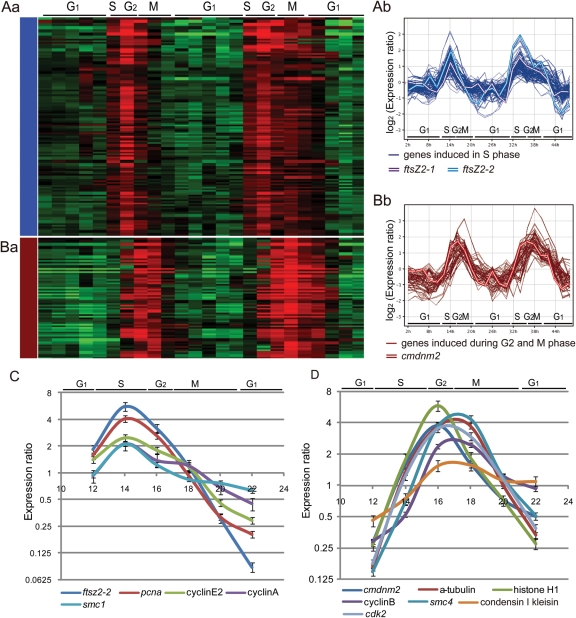

The microarray analysis of two cell cycles from 2 to 50 hrs, in addition to the previously known periodic genes such as ftsZ1 and ftsZ2, identified 358 cell cycle-regulated genes by hierarchical clustering. They were classified by K-means clustering analysis into four expression patterns, early G1 group, late G1 group, S group and G2-M group. This grouping showed that ftsZ2 and cmdnm2 were strongly induced in the S- and G2-M phases, respectively (Fig. 3A and B). Therefore, in the present study, as the genes related to cell nuclear and organelle division were induced during the S- and G2-M phases, we focused on the genes grouped into these category.

Figure 3.

Heatmaps and oscillations of genes in S or G2-M groups. (Aa) The heatmap of transcriptional levels of genes in the S-phase group. Genes correspond to the rows, and the time points form the columns. Red and green indicate induction and suppression of genes expression, respectively. (Ab) The oscillations of transcriptional levels in the S-phase group. This group contained ftsZ2-1 and ftsZ2-2. (Ba) The heatmap of transcriptional levels of genes in the G2-M-phase group. (Bb) The oscillations of transcriptional levels in the G2-M-phase group. This group contained cmdnm2. (C) Real-time RT–PCR assay of some genes in the S-phase group. ftsZ2-2, pcna, cyclin E2, cyclin A and smc1, which were assigned in the S-phase, were confirmed to have peak in S phase. (D) Real-time RT–PCR assay of some genes in the G2-M phase group. cmdnm2, a-tubulin, histone H1, cyclin B, smc4, condensing I kleisin subunit, and cdk2, which were assigned in G2-M phase, were confirmed to have peak in G2-M phase.

The S- and G2-M phase groups comprised a total of 158 genes including 95 genes (Fig. 3A) in the S-phase and 63 genes in the G2-M phase (Fig. 3B) (Table 1). Twelve genes were related to cell cycle progression such as cyclin E2/CML219C, cdk2/CMH128C and ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2/CMS304C. 51 genes were related to cell nuclear function such as DNA replication, and chromosome segregation and organization. The genes characteristically induced were: DNA replication; pcna/CMS101C, mcm3/CMH264C and mcm6/CMJ261C, chromosome segregation; α-tubulin /CMT504C,28 β-tubulin /CMN263C and γ-tubulin /CMN304C, chromosome organization; histone gene set and smc4/CME029C. In addition to the nucleus, genes related to mitochondria and plastids could be identified. 5 genes were related to mitochondrial function. ftsZ1-1, ftsZ1-2 and mda129 were involved in mitochondrial division; moreover, the outer mitochondrial membrane protein, porin/CMO111C and NADH dehydrogenase I (Complex I) beta subcomplex 7/CMC099C, were also induced. 5 genes were related to plastid function. ftsZ2-1, ftsZ2-2 and cmdnm2/CMN262C were involved in chloroplast division. 2 plastid terminal oxidases/CMI243C and CMI244C were also induced. 3 genes, including vps29/CMR405, Rab family protein/CMF181C and CMQ189C, related to vesicle trafficking were induced, and they might be involved in the partitioning of the ER, the Golgi body and endosome.

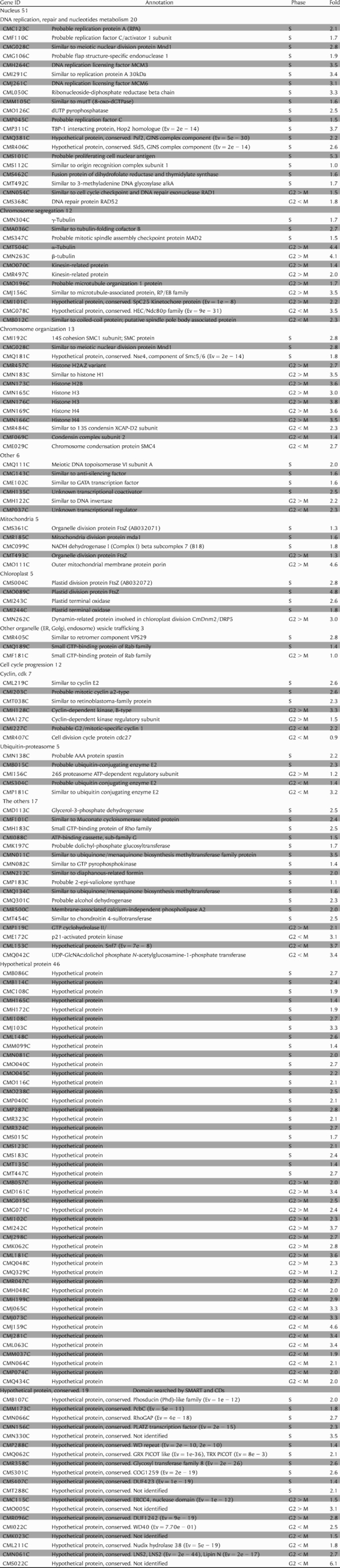

Table 1.

List of genes induced during S or G2-M phase

|

Gene ID and Annotation were shown by the C. merolae genome project. Phase refers to phase when transcriptional level had peaks in microarray analysis, Fold describes log2(max − min of transcriptional levels); Ev, expect value by SMART or Conserved domain search (CDs).

The changes in ftsZ2-1 and ftsZ2-2 transcription levels in the microarray analysis were consistent with those in the RT–PCR assay, supporting effective microarray detection of the change of gene expressions. The expression pattern of some genes, strongly induced in the S or G2-M phases, were analyzed by real-time RT–PCR assay. ftsz2-2, pcna, cyclin E2, cyclinA/CMI203C and smc1/CMI192C, which were assigned to the S-phase by microarray analysis, peaked in the late S-phase (Fig. 3C). cmdnm2, α-tubulin, histone H1/CMN183C, cyclinB/CMI227C, cdk2/CMH128C, smc4/CME029C, condensin kleisin I subunit/CMF069C, which were assigned to the G2-M phase, peaked in the G2- or M-phase (Fig. 3D). These results also supported the accuracy of microarray data in the present analysis.

In the division of the mitochondria and plastids, it is very important that ftsZ1-1, ftsZ1-2, mda1, ftsZ2-1, ftsZ2-2 and cmdnm2 have been identified in the S- or G2/M-phase groups. mdv1 and caf4, mda1 homologue in S. cerevisiae, do not show periodic expression in the cell cycle (Saccharomyces Genome Database: http://www.yeastgenome.org/). Moreover, transcriptions of ftsZ2 and cmdnm2 homologues in A. thaliana are also not considered periodic in microarray analysis11 because mitochondria in yeast and animal cells take various shapes and perform fission and fusion randomly. Similarly, synchronous division of mitochondria and plastids do not occur in higher plants. In C. merolae, as organelles divide synchronously, microarray analysis could be utilized to investigate organelle divisions. It was thought that gene expression profiles during the S- and G2-M-phases were important clues for finding novel genes related to organelle division.

3.4. Candidates for novel genes involved in organelle division

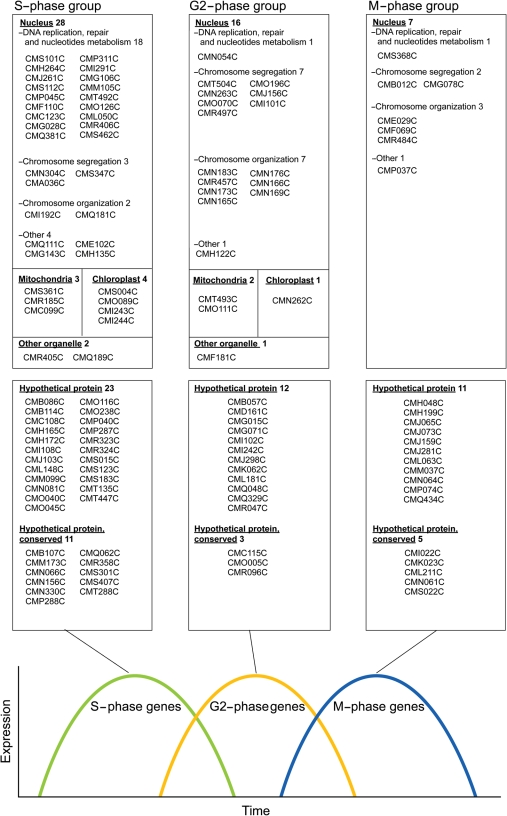

Unknown genes periodically expressed during the S- and G2-M-phase groups can be candidates for novel genes involved in cell nucleus and organelle division. The S and G2-M groups comprised a total of 158 genes including 93 known, 46 hypothetical and 19 hypothetical conserved genes. The hypothetical and hypothetical conserved genes were unknown, and searched for using BlastP, CDs: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi and SMART: http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/ (Table 1). The hypothetical genes were specific to C. merolae, the hypothetical conserved had a conserved domain that had significant hits on genes in other organisms. Therefore, the 19 hypothetical conserved genes were good candidates for novel organelle division genes because they are possible for analyzing organelle division in eukaryotes. We grouped candidate genes with known genes into the S, G2 and M phases to show a tendency of function and localization by the phase of expression peaks (Fig. 4). Genes involved in the cell nucleus were widely found among the S-, G2- and M-phase groups. The S-phase group included genes related to DNA replication, and G2- and M-phase groups included genes related to chromosome segregation and organization. The genes involved in mitochondria and plastids were mainly contained in the S group. This suggested that candidate genes contained in the S group were more related to division of organelles such as mitochondria and plastids. In the candidate, 11, 3 and 5 genes were contained in the S, G2 and M groups, respectively. Therefore, 11 genes in the S group might be more related to organelle division, while the 3 and 5 genes in the G2 and M groups might be involved in cell nucleus division.

Figure 4.

The list of genes related to the function in cell nucleus and organelle, and unknown genes in the S-, G2- or M-phase groups. Left, center and right column shows genes in the S-, G2- and M-phase groups, respectively. Functions of genes surrounded in upper squares were known, whereas those of hypothetical and hypothetical conserved genes surrounded in below squares were poorly known or entirely unknown.

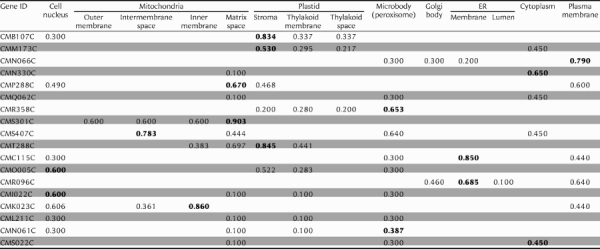

Localization of the 19 candidate genes were predicted by Psort server: http://psort.ims.u-tokyo.ac.jp/ (Table 2). The predictions of the S genes were, as expected, occupied by mitochondria and plastids. The G2 genes were predicted to relate to the cell nucleus and ER. The M genes were involved in cell nucleus and microbody and mitochondria. These predictions were consistent with the order of organelle division in C. merolae, i.e. plastid, mitochondrion, finally cell nucleus and microbody (Fig. 1B). These results must provide a tool for the analyzing the genes for organelle division.

Table 2.

Predicted localization of unknown genes by PSORT

|

Psort server; http://psort.ims.u-tokyo.ac.jp/. The numbers show certainty value in Psort server. The numbers emphasized by bold show highest certainty value among searched organelles.

4. Availability

The microarray data for the cell cycle in C. merolae have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information, Gene Expression Omnibus: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/. Accession number is GPL5399.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available online at www.dnaresearch.oxfordjournals.org.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Fellowships (no. 5061 to T.F.) and for Scientific Research on Priority Areas (no. 17051029 to T.K.) and the Frontier Project ‘Adaptation and Evolution of Extremophiles’ from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, and from the program for the Promotion of Basic Research Activities for Innovative Biosciences (PROBRAIN to T.K.).

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Edited by Katsumi Isono

References

- 1.Maqbool Z., Kersey P. J., Fantes P. A., et al. MCB-mediated regulation of cell cycle-specific cdc22+ transcription in fission yeast. Mol. Gen. Genomics. 2003;269:765–775. doi: 10.1007/s00438-003-0885-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Futcher B. Microarrays and cell cycle transcription in yeast. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2000;12:710–715. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00156-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cho R. J., Campbell M. J., Winzeler E. A., et al. A genome-wide transcriptional analysis of the mitotic cell cycle. Mol. Cell. 1998;2:65–73. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spellman P. T., Sherlock G., Zhang M., et al. Comprehensive identification of cell cycle-regulated genes of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae by microarray hybridization. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1998;9:3273–3297. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.12.3273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rustici G., Mata J., Kivinen K., et al. Periodic gene expression program of the fission yeast cell cycle. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:809–817. doi: 10.1038/ng1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peng. X., Karuturi R. K., Miller L. D., et al. Identification of cell cycle-regulated genes in fission yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;3:1026–1042. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-04-0299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oliva A., Rosebrock A., Ferrezuelo F., et al. The cell cycle-regulated genes of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho R. J., Huang M., Campbell M. J., et al. Transcriptional regulation and function during the human cell cycle. Nat. Genet. 2001;27:8–54. doi: 10.1038/83751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whitfield M. L., Sherlock G., Saldanha A. J., et al. Identification of genes periodically expressed in the human cell cycle and their expression in tumors. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2002;13:1977–2000. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02-02-0030.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dyczkowski J., Vingron M. Comparative analysis of cell cycle regulated genes in eukaryotes. Genome Inform. 2005;16:25–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Menges M., Hennig L., Gruissem W., Murray J. A. Cell cycle-regulated gene expression in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:41987–42002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207570200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Breyne P., Dreesen R., Vandepoele K., et al. Transcriptome analysis during cell division in plants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:14825–14830. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222561199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuroiwa T. The primitive red algae: Cyanidium caldarium and Cyanidioschyzon merolae as model systems for investigation the dividing apparatus of mitochondria and plastids. BioEssays. 1998;20:344–354. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Misumi O., Matsuzaki M., Nozaki H., et al. Cyanidioschyzon merolae genome. A tool for facilitating comparable studies on organelle biogenesis in photosynthetic eukaryotes. Plant Physiol. 2005;137:567–585. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.053991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miyagishima S. Y., Itoh R., Toda K., et al. Visualization of microbody division in Cyanidioschyzon merolae with fluorochrome brilliant sulfoflavin. Protoprasma. 1998;205:153–164. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yagisawa F., Nishida K., Kuroiwa H., et al. Identification and mitotic partitioning strategies of vacuoles in the unicellular red alga Cyanidioschyzon merolae. Planta. 2007;226:1017–1029. doi: 10.1007/s00425-007-0550-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suzuki K., Ehara T., Osafune T., et al. Behavior of mitochondria, plastids and their nuclei during the mitotic cycle in the ultramicroalga Cyanidioschyzon merolae. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 1994;63:280–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takahara M., Takahashi H., Matsunaga S., et al. A putative mitochondrial ftsZ gene is present in the unicellular primitive red alga Cyanidioschyzon merolae. Mol. Gen. Genet. 2000;264:452–460. doi: 10.1007/s004380000307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miyagishima S. Y., Itoh R., Aita S., et al. Isolation of dividing plastids with intact plastid-dividing rings from a synchronous culture of the unicellular red alga Cyanidioschyzon merolae. Planta. 1999;209:371–375. doi: 10.1007/s004250050645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nishida K., Takahara M., Miyagishima S. Y., et al. Dynamic recruitment of dynamin for final mitochondrial severance in a primitive red alga. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:2146–2151. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0436886100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miyagishima S. Y., Nishida K., Mori T., et al. A plant-specific dynamin-related protein forms a ring at the plastid division site. Plant Cell. 2003;15:655–665. doi: 10.1105/tpc.009373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuroiwa T., Suzuki K., Kuroiwa H. Mitochondrial division by an electron-dense ring in Cyanidioschyzon merolae. Protoplasma. 1993;175:173–177. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miyagishima S. Y., Takahara M., Kuroiwa T. Novel filaments 5 nm in diameter constitute the cytosolic ring of the plastid division apparatus. Plant Cell. 2001;13:707–722. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.3.707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsuzaki M., Misumi O., Shin-I T., et al. Genome sequence of the ultrasmall unicellular red alga Cyanidioschyzon merolae 10D. Nature. 2004;428:653–665. doi: 10.1038/nature02398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nozaki H., Takano H., Misumi O., et al. A 100%-complete sequence reveals unusually simple genomic features in the hot-spring red alga Cyanidioschyzon merolae. BMC Biol. 2007;5:28. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-5-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohta N., Sato N., Kuroiwa T. Structure and organization of the mitochondrial genome of the unicellular red alga Cyanidioschyzon merolae deduced from the complete nucleotide sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:5190–5198. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.22.5190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohta N., Matsuzaki M., Misumi O., et al. Complete sequence and analysis of the plastid genome of the unicellular red alga Cyanidioschyzon merolae. DNA Res. 2003;10:67–77. doi: 10.1093/dnares/10.2.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nishida K., Yagisawa F., Kuroiwa H., et al. Cell cycle-regulated, microtubule-independent organelle division in Cyanidioschyzon merolae. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;16:2493–2502. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-01-0068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nishida K., Yagisawa F., Kuroiwa H., et al. WD40 protein Mda1 is purified with Dnm1 and forms a dividing ring for mitochondria before Dnm1 in Cyanidioschyzon merolae. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:4736–4741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609364104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.