SYNOPSIS

Objective

This study examined whether youth who live in an urban, disadvantaged community are significantly more likely than youth representing the nation to engage in a range of health-compromising behaviors.

Methods

Analyses were based on the Youth Violence Survey conducted in 2004 and administered to students (n=4,131) in a high-risk school district. Students in ninth grade (n=1,114) were compared with ninth-grade students in the 2003 national Youth Risk Behavior Survey (n=3,674) and the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health conducted in 1995/1996 (n=3,523). Analyses assessed the differences in prevalence of risk and protective factors among ninth-grade students from the three studies using Chi-square tests.

Results

The results showed that youth in this urban, disadvantaged community were significantly more likely than their peers across the country to report vandalism, theft, violence, and selling drugs. Youth in this community also reported significantly less support from their homes and schools, and less monitoring by their parents. Moreover, youth in this community were significantly less likely to binge drink or initiate alcohol use prior to age 13 than youth across the U.S.

Conclusions

Youth who live in this urban, disadvantaged community reported significantly higher prevalence of some, but not all, risky behaviors than nationally representative U.S. youth. These findings highlight that some caution is justified when defining what might constitute high risk and that demographic and other characteristics need to be carefully considered when targeting certain high-risk behaviors.

Researchers and health practitioners concerned with preventing unsafe sexual behaviors, substance use, suicide attempts, unintentional injuries, and violence among youth often use the term “high risk” as a shorthand to describe adolescents who face disadvantage or adversity narrowly or broadly defined. Disadvantage and adversity are often determined through the level of poverty, unemployment, and crime in a community,1,2 living in an urban area,3–7 or being a member of a minority group.7 High-risk youth are also identified because they attend alternative high schools,8–10 have been involved, or are at risk for involvement, in the juvenile justice system,11 engage in certain behaviors such as drinking alcohol,12 participate in school dropout prevention programs,13,14 or participate in other programs or services such as youth drop-in centers.15

The term “high-risk youth” is so frequently used that an online search using Google® yielded 2.6 million hits. Likewise, a search of the PubMed database for “high-risk youth” yielded a list of 16,954 scientific publications related to this topic. In addition to the term “high-risk youth,” there are other variations such as “at-risk youth” and “problem youth” that are also commonly used. While the term high-risk youth is frequently used, it is not always clearly defined. The underlying rationale for using this shorthand to describe youth who may be high risk, at risk, or who live in high-risk communities is based on efforts to streamline resources and to maximize the effectiveness of targeted prevention programs and interventions. Nevertheless, youth who live in high-risk communities, surrounded by poverty, unemployment, and crime, may not necessarily be at higher risk of engaging in risky behaviors despite their immediate surroundings and accompanying community-level risk factors. Efforts to quantify and describe high-risk behaviors among youth who live in an urban, disadvantaged community relative to nationally representative populations are scarce. However, such studies are needed to better determine and understand risk for involvement in health-compromising behaviors and to allocate limited resources for prevention and intervention programs.

National and state-level data collection projects frequently rely on complex sampling strategies to obtain representative samples of participants. These data systems are then used to determine the burden of disease, prevalence of health-risk behaviors, trends in disease or behavior patterns over time, geographic variability in disease patterns, and behaviors and demographic characteristics or risk factors associated with disease or health-risk behaviors.16 The data obtained from these efforts are critical for health monitoring and disease prevention but are most often not available at the local level.17 Local data (e.g., data from the county, city, or community) are needed to supplement national and state-level data by providing more specific information about geographic areas of increased risk and also to provide the baseline data for targeted prevention and intervention efforts. The need for local health data has been emphasized and explained in several publications,17–20 and some large surveillance systems are now incorporating and collecting information in local areas.21

A recent study highlighted large variations in health conditions within a large city,17 suggesting that there is a need to collect data at even smaller geographic boundaries or communities. As additional data collection efforts for smaller geographic regions are implemented and data become available, the need for appropriate and relevant comparisons for disease prevalence and health-risk behaviors across topics will be desirable. So far, general comparisons of involvement in high-risk behaviors across a range of health-risk behaviors among youth who live in a defined and urban, disadvantaged community and nationally representative samples of adolescents have not, to our knowledge, been systematically reported.

This study sought to determine and statistically examine whether ninth-grade students who live in one disadvantaged, urban community (broadly defined as the catchment area of an urban school district) are significantly more likely to engage in a range of health-compromising behaviors than youth representative of the nation. Findings from this study can have implications for how we quantify and define high risk and also how we address health disparities in urban, disadvantaged communities disproportionately populated by minorities.

METHODS

The current analyses, conducted in 2005 and 2006, used data from the 2004 Youth Violence Survey: Linkages Among Different Forms of Violence (Linkages), the 2003 Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), and the first wave (1995/1996) of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health).

Linkages

The cross-sectional Linkages covered topics pertaining to delinquency, substance use, interpersonal violence, suicide, and other high-risk behaviors. The survey was administered to students in grades seven, nine, 11, and 12 from 16 schools in a high-risk school district.1,2 The high-risk community was chosen by ranking U.S. cities on several community indicators (e.g., rates of poverty, unemployment, single-parent households, and serious crimes) and determining the most appropriate school districts within those cities based on the number of students enrolled, feasibility of conducting the study, and the school district's willingness to host the study. The selected city and school district were among the highest 25 nationally in poverty, the highest 15 in single-parent families, the highest 10 in serious crime, and the highest 35 in unemployment. The selected school district was racially and ethnically diverse and located in a city with a population of less than 250,000. Per the request of the school district, its name and location are not to be disclosed. This district operated 16 schools and served students at one or more of the targeted grades. All 16 schools were invited and all 16 schools agreed to participate in the study. These included elementary, middle, and high schools, as well as alternative schools.

All eligible English-speaking students in the selected grades were invited to participate in the survey. The three grade levels were selected to assess potential age differences or developmental patterns during the transition from early to late adolescence among high-risk students. Students were identified through class lists of required core subjects (e.g., English) in the selected grades or through their homerooms.

Prior to data collection, all students younger than 18 years of age were required to obtain signed, written parental permission to participate in the study. Students who were at least 18 years of age provided written consent prior to participating in the survey. Student permission forms were provided in English, Spanish, and other major languages as requested by the schools.

Data collection occurred in April 2004. The anonymous, self-administered questionnaire was conducted by experienced field staff during a 40-minute class period. Students were ineligible to participate if they could not complete the questionnaire independently (e.g., enrolled in a special education class, required the assistance of a translator, or had cognitive disabilities that would prevent adequate understanding and responding to the survey) (n=151) or if the student had dropped out of school, had been expelled, or was on long-term out-of-school suspension (n=202). Of the 5,098 students who were eligible for participation, 4,131 participated, yielding a participation rate of 81.0%. Participants were enrolled from three grade levels: 1,491 in seventh grade, 1,114 in ninth grade, and 1,523 in 11th and 12th grades.

YRBS

The YRBS is a nationally representative, cross-sectional, school-based survey of U.S. high school students that measures risk and health behaviors among students in grades nine through 12. Details of the survey have been described elsewhere.22,23 The sampling frame for YRBS includes all public and private schools in the U.S. that have at least one grade between nine and 12. The current analyses are based on the 2003 survey administration, which was completed by 13,953 students. The overall response rate was 67.0%. Students voluntarily completed the anonymous, self-administered questionnaire in school following local parental permission procedures. The data were weighted to be representative of students in grades nine through 12 in public and private schools in the U.S.

Add Health

Add Health is a longitudinal study of health and health-related behaviors that collects information on a broad range of individual, family, school, and community factors. The first wave of data was collected from students in grades seven through 12 who attended either public or private schools during the 1994–1995 school year. Details regarding the survey methodology are described elsewhere.24 In brief, this study used a multistage probability sample design, had a response rate of 78.9%, and resulted in a nationally representative sample of adolescents (n=18,924). Students completed the 90-minute in-home interview using computer-assisted personal interviewing and audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (ACASI) for sensitive information, where participants listened to the questions through headphones and gave responses directly on a laptop computer to increase accuracy of reporting.

Analyses

The studies used for the analyses included different grade levels in their study populations. The Linkages survey included students in seventh, ninth, 11th, and 12th grades, whereas the YRBS included students in ninth through 12th grades. To allow for meaningful comparisons among students in the same grade level, all analyses were restricted to students in the ninth grade. Therefore, the numbers of participants included in the analyses from each of the three studies were: Linkages, n=1,114; YRBS, n=3,674; and Add Health, n=3,523. YRBS also included a measure of urbanicity that was used to identify participants in the ninth grade who attended school in urban areas (n=1,411).

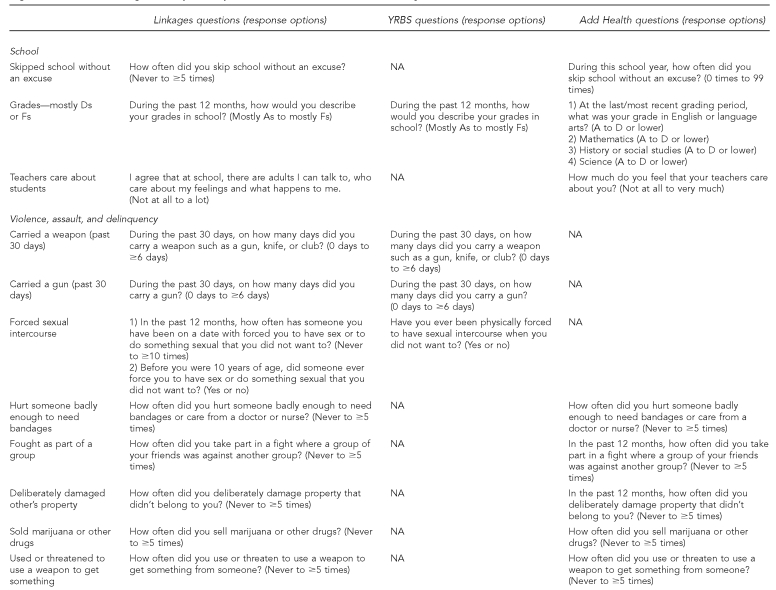

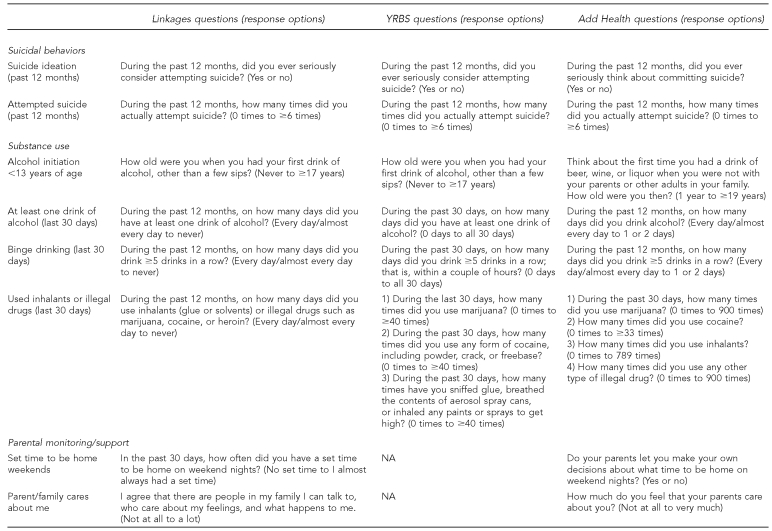

For the current analyses, measures of demographic characteristics, school performance, violence, assault and delinquency, suicidal behaviors, substance use, parental monitoring, and support were used to compare data from the three studies. For some variables, survey questions were worded slightly differently, different time periods were captured, or response options varied. In such cases, efforts were made to recode the variables, where possible, to allow for meaningful comparisons. (A description of how all the variables were recoded is available upon request from the authors.) A detailed comparison of the questions included in the comparisons as well as their response options is presented in the Figure. Analyses were conducted using SAS® Version 9.125 and SUDAAN®26 statistical software to incorporate the survey sampling designs of YRBS and Add Health. Differences in proportions were assessed using Chi-square tests.

Figure.

Question wording and response options of measures included in three youth studies

Linkages = 2004 Youth Violence Survey: Linkages Among Different Forms of Violence

YRBS = 2003 Youth Risk Behavior Survey

Add Health = National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (1995/1996)

NA = not applicable

RESULTS

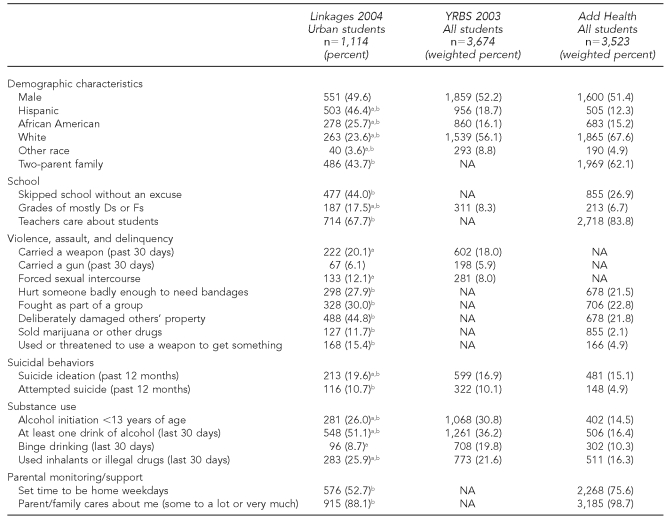

Comparisons among ninth graders in the Linkages study, YRBS, and Add Health (Table 1) showed that there were racial/ethnic differences among study participants primarily reflected by a larger proportion of Hispanic and African American participants in the Linkages study vs. the other two studies. Several significant differences in the prevalence of involvement or exposure to risky behaviors were observed. In terms of school factors, skipping school without an excuse was significantly more common among Linkages participants (44.0%) than among participants in Add Health (26.9%). Moreover, lower grades (mostly Ds or Fs) were also significantly more common among Linkages participants (17.5%) than among participants in either YRBS (8.3%) or Add Health (6.7%).

Table 1.

Comparison of demographic characteristics and involvement in risk behaviors and experiences among ninth graders

aComparison with YRBS resulted in differences significant at p≤0.05.

bComparison with Add Health resulted in differences significant at p≤0.05.

Linkages = 2004 Youth Violence Survey: Linkages Among Different Forms of Violence

YRBS = 2003 Youth Risk Behavior Survey

Add Health = National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (1995/1996)

NA = not applicable

In terms of involvement in delinquent or violent behaviors, Linkages participants (20.1%) were significantly more likely to carry a weapon than YRBS participants (18.0%), but there were no differences for carrying a gun. Using or threatening to use a weapon to get something from someone, involvement in group fighting, and having hurt someone badly enough to require bandages were significantly more common behaviors among Linkages participants than among Add Health participants. Likewise, deliberately damaging others' property and selling marijuana or other drugs were also significantly more common behaviors among Linkages participants than among Add Health participants. Significant differences were also noted for reporting suicide ideation or attempts.

Early alcohol use initiation (younger than 13 years of age) was less prevalent among Linkages participants than among YRBS participants. Also, while current binge drinking was less common among Linkages participants than among YRBS and Add Health participants, Linkages participants were more likely than YRBS or Add Health participants to report current, but less heavy, alcohol use. Inhalant and other illegal drug use was also more prevalent among Linkages participants than among YRBS or Add Health participants. Potentially protective factors for involvement in risky behaviors such as parental monitoring (time to be home on weekdays) and support in the home (parent/family cares about me) or at school (teachers care about students) were significantly less common among Linkages participants than among Add Health participants.

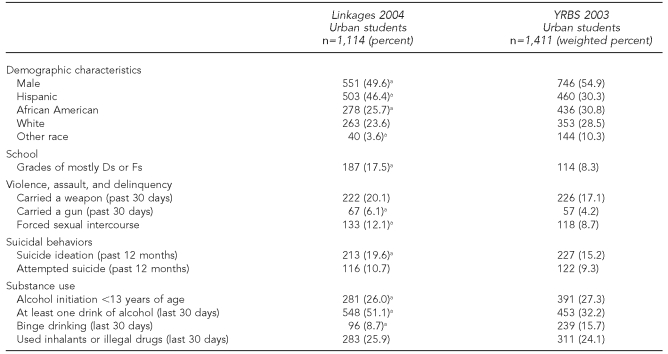

Further comparisons between Linkages participants and YRBS participants who live in an urban setting were made to determine if there were significant differences between youth in a high-risk community and nationally representative youth due to living in an urban setting (Table 2). Demographic differences were noted, and the Linkages participants included a smaller proportion of male, African American, and other minority youth and a larger proportion of Hispanic youth than the YRBS. Linkages participants relative to YRBS participants living in urban settings reported a higher prevalence of lower grades, gun carrying, forced sexual intercourse, suicide ideation, and current drinking. Linkages participants relative to YRBS participants also reported a lower prevalence of early alcohol use initiation and less prevalent binge drinking.

Table 2.

Comparison of demographic characteristics and involvement in risk behaviors and experiences among ninth graders in urban areas

aComparison with YRBS resulted in differences significant at p≤0.05.

Linkages = 2004 Youth Violence Survey: Linkages Among Different Forms of Violence

YRBS = 2003 Youth Risk Behavior Survey

DISCUSSION

The comparisons between youth who live in a high-risk community and youth from nationally representative studies revealed several important findings. Youth who live in an urban, disadvantaged community identified and defined primarily through census indicators (e.g., population below the poverty level, unemployment, single-parent households, and serious crime) were significantly more likely to engage in a range of health-risk behaviors than their peers across the U.S. While a number of statistically significant differences were observed, the largest and potentially most important differences were related to vandalism, involvement in violence including group fighting (a proxy for gang violence), weapon use, and drug selling. Further comparisons between youth in the selected high-risk community and nationally representative youth who live in diverse, urban settings revealed important, but fewer significant differences. These comparisons from our study showed that low grades, gun carrying, suicide ideation, violent sexual victimization, and current alcohol use were significantly more prevalent among youth in a high-risk community relative to urban youth in general.

The findings also showed that youth in the disadvantaged community recruited for Linkages were significantly less likely to binge drink (i.e., consume five or more drinks during the same occasion) and also less likely to initiate alcohol use prior to age 13 than youth across the U.S. In fact, while youth in an urban, disadvantaged community were more likely to report current alcohol use than urban youth across the nation, they remained less likely to report initiating alcohol use prior to age 13 or to binge drink compared with nationally representative urban youth. These findings highlight that some caution is justified when defining what may constitute high-risk youth and that demographic and other characteristics need to be carefully considered when targeting certain high-risk behaviors.

With respect to alcohol use, studies indicate that drinking prevalence and patterns vary dramatically during the adolescent years,22 and binge drinking tends to be less common among African American and Hispanic adolescents relative to white adolescents.16 These findings likely contribute to the patterns observed in the current study, in which a higher percentage of students were self-described as minorities than in the general population. Moreover, the risk factors pertaining specifically to youth alcohol initiation are relatively poorly understood and very few studies have examined alcohol initiation specifically among minority youth.27,28

Limitations

Several limitations should be noted when interpreting these findings. First, the analyses compared prevalence of health-risk behaviors between students in one urban, disadvantaged community relative to participants in two studies of nationally representative youth. The selected urban, disadvantaged community may not be representative of other urban, disadvantaged communities. However, the comparisons provided highlight that health-risk behaviors among youth within an urban, disadvantaged context, and also relative to nationally representative youth, are worth further exploration.

Second, analyses were restricted to students in the ninth grade to allow for meaningful and relevant comparisons with other data sources and also because the proportion of ninth graders who remain in school is higher than that of students in subsequent grades. Limiting analyses to ninth graders may yield findings that do not generalize to younger or older students or to youth who are no longer attending school.

Third, the Linkages and YRBS studies are the most appropriate comparisons because the survey administrations, which included anonymous paper and pencil multiple-choice survey formats, were nearly equivalent and also administered only one year apart. The Add Health study was administered in 1995 and the data were obtained through in-home interviews, mostly using ACASI. Therefore, differences noted between the Linkages and Add Health studies may be attributable, in part, to the different methodologies and the number of years between data collections. In particular, research on the effects of data collection methodology reveals that school-based surveys tend to yield higher prevalence estimates for health-risk behaviors than do household-based surveys.29 Despite these limitations, the inclusion of the Add Health data provides an additional source and useful national comparison of these risky behaviors, which are relatively stable across time and also are rarely assessed in other national studies.

Fourth, not all questions were worded identically, which may also yield differences among the studies.30 Fifth, because the purpose of the analyses was to compare urban youth relative to the U.S. representative youth, statistical analyses were conducted and presented to illustrate the similarities and differences among the groups without statistically controlling for potential factors that may explain these differences. Moreover, because the number of participants was relatively large across the studies, some of the statistical differences observed were small. Finally, all the findings were based on self-reported data without any corroboration with other sources and were, therefore, subject to reporting biases.

CONCLUSIONS

This study compared and quantified involvement in a range of health-compromising behaviors among ninth-grade students who live in an urban, disadvantaged community relative to their peers across the U.S. The findings showed that youth who may be described as high risk because they live in an urban, disadvantaged community (based on census indicators) are significantly more likely than their peers across the country to report involvement in a number of risky and criminal behaviors including vandalism, violence, and selling drugs. Moreover, the youth who live in an urban, disadvantaged community were also significantly more likely than their peers across the country to report less support from their homes and schools and less monitoring by their parents. These additional barriers in forms of lower academic achievement and less available support and structure in the home and school environments likely exacerbate the already limited opportunities for youth to engage in safe, productive, and meaningful activities within an urban, disadvantaged community and can further provide context as to why these youth engage in more high-risk behaviors.

While this study showed significantly higher involvement in many high-risk behaviors among youth in an urban, disadvantaged community compared with youth in national samples, the relative difference between youth in an urban, disadvantaged community and nationally representative youth may not be as pronounced as one would expect and may in some cases not represent meaningful differences. In fact, lower levels of involvement in some risk behaviors among youth from the high-risk community were observed. It is important to recognize, however, that the type of disadvantage can vary across communities and can also comprise different social issues and community characteristics.

Nonetheless, it is recommended that the term high risk, unless specifically quantified and described, be used with caution. There is a clear need to rethink our use of the term high risk and the impact it may have both for research and practice. Minimally, it will be important to specify if, and when, high risk refers to primarily social or environmental contextual factors such as living in an urban, disadvantaged community or when high risk refers to individual behaviors or other exposures that increase the likelihood of adverse health outcomes. However, in either case, a comparison or a reference point that quantifies the excess risk would also be helpful and meaningful. Finally, because of diminishing resources and increased demand for accountability and impact of our research and programs, providing a specific and carefully operationalized approach to identifying and quantifying youth at high risk is necessary and could greatly improve comparisons across studies as well as the identification of priorities for prevention.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the entire 2004 Youth Violence Survey: Linkages Among Different Forms of Violence team from ORC Macro, CDC, and Battelle who contributed to the planning and implementation of the Linkages Study; the school district for its enthusiasm and logistic support of this project; the students for their time and willingness to participate in this study; and the Youth Risk Behavior Survey and National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health) teams and participants in those studies.

Footnotes

Drs. Swahn and Bossarte were in the Division of Violence Prevention, the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) when this research was conducted. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of CDC.

This article used data from Add Health, a program project designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris, and funded by grant #P01-HD31921 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 17 other agencies. Special acknowledgment is due to Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. People interested in obtaining data files from Add Health should contact Add Health, Carolina Population Center, 123 W. Franklin St., Chapel Hill, NC 27516-2524; e-mail <addhealth@unc.edu>.

REFERENCES

- 1.Swahn MH, Simon TR, Arias I, Bossarte RM. Measuring sex differences in violence victimization and perpetration within date and same-sex peer relationships. J Interpers Violence. 2008;23:1120–38. doi: 10.1177/0886260508314086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swahn MH, Bossarte RM, Sullivent EE. Age of alcohol use initiation, suicidal behavior, and peer and dating violence victimization and perpetration among high-risk, seventh-grade adolescents. Pediatrics. 2008;121:297–305. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blitstein JL, Murray DM, Lytle LA, Birnbaum AS, Perry CL. Predictors of violent behavior in an early adolescent cohort: similarities and differences across gender. Health Educ Behav. 2005;32:175–94. doi: 10.1177/1090198104269516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brookmeyer KA, Henrich CC, Schwab-Stone M. Adolescents who witness community violence: can parent support and prosocial cognitions protect them from committing violence? Child Dev. 2005;76:917–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng TL, Schwartz D, Brenner RA, Wright JL, Fields CB, O'Donnell R, et al. Adolescent assault injury: risk and protective factors and locations of contact for intervention. Pediatrics. 2003;112:931–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.4.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng TL, Wright JL, Fields CB, Brenner RA, O'Donnell R, Schwarz D, et al. Violent injuries among adolescents: declining morbidity and mortality in an urban population. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;37:292–300. doi: 10.1067/mem.2001.111763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gordon-Smith D, Henry DB, Tolan PH. Exposure to community violence and violence perpetration: the protective effects of family functioning. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2004;33:439–49. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3303_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galaif ER, Sussman S, Chou CP, Wills TA. Longitudinal relations among depression, stress, and coping in high-risk youth. J Youth Adolesc. 2003;32:243–58. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rohrbach LA, Sussman S, Dent CW, Sun P. Tobacco, alcohol, and other drug use among high-risk young people: a five-year longitudinal study from adolescence to emerging adulthood. J Drug Issues. 2005;35:333–56. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sussman S, Simon TR, Dent CW, Steinberg JM, Stacy AW. One-year prediction of violence perpetration among high-risk youth. Am J Health Behav. 1999;23:332–44. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.28.2.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruffolo MC, Sarri R, Goodkind S. Study of delinquent, diverted, and high-risk adolescent girls: implications for mental health intervention. Soc Work Res. 2004;28:237. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swahn MH, Donovan JE. Correlates and predictors of violent behavior among adolescent drinkers. J Adolesc Health. 2004;34:480–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chase KA, Treboux D, O'Leary KD, Strassberg Z. Specificity of dating aggression and its justification among high-risk adolescents. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1998;26:467–73. doi: 10.1023/a:1022651818834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chase KA, Treboux D, O'Leary KD. Characteristics of high-risk adolescents' dating violence. J Interpers Violence. 2002;17:33–49. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bousman CA, Blumberg EJ, Shillington AM, Hovell MF, Ji M, Lehman S, et al. Predictors of substance use among homeless youth in San Diego. Addict Behav. 2005;30:1100–10. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Center for Health Statistics (US) Health, United States, 2005: with chartbook on trends in the health of Americans. NCHS (US): Hyattsville (MD); 2005. [cited 2008 Oct 6]. Also available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus05.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shah AM, Whitman S, Silva A. Variations in the health conditions of 6 Chicago community areas: a case for local-level data. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1485–91. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.052076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frieden TR. Asleep at the switch: local public health and chronic disease. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:2059–61. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.12.2059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simon PA, Wold CM, Cousineau MR, Fielding JE. Meeting the data needs of a local health department: the Los Angeles County Health Survey. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1950–2. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.12.1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fielding JE, Frieden TR. Local knowledge to enable local action. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27:183–4. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hughes E, McCracken M, Roberts H, Mokdad AH, Valluru B, Goodson R, et al. Surveillance for certain health behaviors among states and selected local areas—Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, United States, 2004. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2006;55(7):1–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, Ross J, Hawkins J, Harris WA, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2005. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2006;55(5):1–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grunbaum JA, Kann L, Kinchen S, Ross J, Hawkins J, Lowry R, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2003. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2004;53(2):1–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris KM, Florey F, Tabor J, Bearman PS, Jones J, Udry RJ. Add Health: study design. [cited 2006 Jul 14]. Available from: URL: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design.

- 25.SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT: Version 9.1. Cary (NC): SAS Institute Inc.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN Language Manual: Release 9.0. Research Triangle Park (NC): Research Triangle Institute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donovan JE. Adolescent alcohol initiation: a review of psychosocial risk factors. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35:7–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bossarte RM, Swahn MH. Interactions between race/ethnicity and psychosocial correlates of preteen alcohol use initiation among seventh grade students in an urban setting. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2008;69:660–5. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kann L, Brener ND, Warren CW, Collins JL, Giovino GA. An assessment of the effect of data collection on the prevalence of health risk behaviors among adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31:327–35. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00343-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brener ND, Grunbaum JA, Kann L, McManus T, Ross J. Assessing health risk behaviors among adolescents: the effect of question wording and appeals for honesty. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35:91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]