Abstract

Ultrastructural observations reveal a continuous interstitial matrix connection between the endocrine and exocrine pancreas, which is lost due to fibrosis in rodent models and humans with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Widening of the islet exocrine interface (IEI) appears to result in loss of desmosomes and adherens junctions between islet and acinar cells and is associated with hypercellularity consisting of pericytes and inflammatory cells in T2DM pancreatic tissue. Organized fibrillar collagen was closely associated with pericytes, which are known to differentiate into myofibroblasts – pancreatic stellate cells. Importantly, some pericyte cellular processes traverse both the connecting IEI and the endoacinar interstitium of the exocrine pancreas.

Loss of cellular paracrine communication and extracellular matrix remodeling fibrosis in young animal models and humans may result in a dysfunctional insulino-acinar-ductal – incretin gut hormone axis resulting in pancreatic insufficiency and glucagon like peptide deficiency known to exist in prediabetes and overt T2DM in humans.

INTRODUCTION

The endocrine and exocrine pancreas has traditionally been considered to be two separate entities. However, the pancreas is usually classified as a lobulated compound endocrine tubulo-acinar gland. The endocrine (islets) secrete hormones directly into the blood (internal secretion) and the exocrine pancreas secretes enzymes and other substances into a duct system and thus to a body surface i.e. the gut (external secretion).

Embryologically, both pancreatic entities develop in a similar fashion by invaginations of epithelial cells into the connective tissue underlying an epithelial membrane. The site of original invaginations of the exocrine portion persists as a duct and acinar system; whereas, connections with the epithelial membrane are lost in the islet. Thus, islet tissue secretory products are passed into the systemic circulation as hormones (1).

The structure of the pancreas in mammals has undergone significant ontological evolution. For example, in protochordates the islet cells are distributed throughout the gut mucosa, in the Atlantic hagfish the first islet-like structure is noted and closely related to the bile duct, in cartilaginous fish (sharks and rays) the islet becomes intimately associated with the pancreatic duct and in mammals the islets and exocrine tissue are fused into one compound glandular organ functioning synergistically to aid in the digestion of oral nutrients and metabolism. Thus, evolution has lead to merging of the endocrine and exocrine pancreas into one organ allowing for improved endocrine and paracrine communication (1).

Indeed, an artificial subdivision of the pancreas precludes the study of this lobulated, compound tubuloalveolar-acinar gland and precludes the investigation of the endocrine-exocrine pancreas in its role as an interdependent synergistic system in health and disease (2). Therefore, we have chosen to focus on the cell-cell, cell-matrix, extracellular matrix (ECM), insulo-acinar-ductal-portal vascular pathway and the insulo-acinar-ductal-pancreatic enzyme-incretin-gut hormone axis communications.

Recently, we have made observations utilizing microscopy (transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and special staining with light microscope) demonstrating that many of these cell-cell, cell-matrix, vascular and ductal communications are lost or impaired in young rodent animal models of hypertension, insulin resistance (IR), oxidative stress and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) due to fibrosis (3–5).

With progressive fibrosis the normal wound healing process goes awry due to an ongoing wounding process with resulting structural alterations, which hinders proper tissue and organ function leading to tissue dysfunction and eventual organ failure. In humans with the cardiometabolic syndrome (CMS) and T2DM we have observed that these same communications are lost due to fibrosis of the peri-islet - islet exocrine interface (IEI), the endoacinar and the interlobular periacinar interstitium leading to pancreatic failure.

Endocrine/Exocrine Cell-Cell Communications: LOST

The IEI is an important anatomical and functional region allowing for cell-cell communication between the endocrine islet and exocrine acinar cells of the pancreas. Recently we have observed that desmosomes and adherens junctions exist between islet and acinar cells within the IEI. The functional communication between these two cell types have not been explored at this time but are structurally lost during the remodeling changes associated with the development of T2DM. The IEI was observed to widen at least 40 fold when comparing the 7 week old male Leprdb/db (db/db), a leptin receptor–deficient mouse model of T2DM to its aged-matched, wild type, lean C57BL/6 non-diabetic littermate controls (db/dbWT) (figure 1). Insulin and glucose levels were not available for this ultrastructural study; however it is known that the db/db model develops hyperinsulinemia within two weeks followed by obesity at three to four weeks and hyperglycemia at ages four to eight weeks of age (6). Similar remodeling changes have been noted in the Ren2 model (a rat model of hypertension, insulin resistance (IR) and oxidative stress harboring the mouse renin gene) (3, 4) and the human islet amyloid polypeptide (HIP) rat model (a Sprague Dawley rat transfected with the human amylin gene) of T2DM when compared to the age-matched male Sprague Dawley controls (SDC) (5). The loss of these cell-cell connections (desmosomes and adherens junctions) between the islet and acinar cells have not been previously described to our knowledge.

Figure 1. Cell-Cell Matrix Communications: Lost.

Panel A depicts the islet exocrine interface (IEI) (arrows) in the db/dbWT control model. ZG, zymogen granule; N, acinar cell nucleus; ER, endoplasmic reticulum. Magnification X 1,000. Bar = 2 μm. Panel B demonstrates a higher magnification X6,000 of the IEI and depicts the adherens junctions (arrows) and a representative exploded view of a desmosome insert (b). Bar = 0.2μm. Panel C depicts the IEI in the db/db WT control, which measures approximately 40 nanometers (arrows). Magnification X1300. Bar = 1 μm. Panel D demonstrates the widened IEI (approximately 4,000 nanometers) between an islet cell and acinar cell (double arrow). Note the relative hypocellularity of the islet cell as compared to the islet cell in panel A and C of the WT control model. Also note that this widening is evident at a much lower magnification X500 as compared to panel C. Magnification X500. Bar = 2 μm.

We hypothesize that increased oxidative stress may activate IEI matrix degrading proteases such as matrix metalloproteinase(s) (MMP) and result in enzymatic degradation of these cell-cell connections and thus communication between these two cell types is lost. For example, matrix degrading proteases (MMP 2 -12- 14) are upregulated in the islets of the Zucker diabetic fatty (ZDF) rat model and contribute to the development of diabetes in these models. Further, MMP inhibitors are capable of abrogating the increased remodeling fibrosis of the islet and substantially prevented diabetes in these models (7).

Cell-Matrix Communications: LOST

Pericapillary remodeling fibrosis and islet amyloid deposition have been identified in the ZDF (7), HIP (5, 8, 9) and db/db (10) models of T2DM. Deposition of collagen and/or islet amyloid in the pericapillary region may result in a diffusion barrier and lost cell-cell and cell-matrix communications to small molecules and islet secretory granules referred to as endothelial β-cell uncoupling (EβC uncoupling) (figure 2) (11).

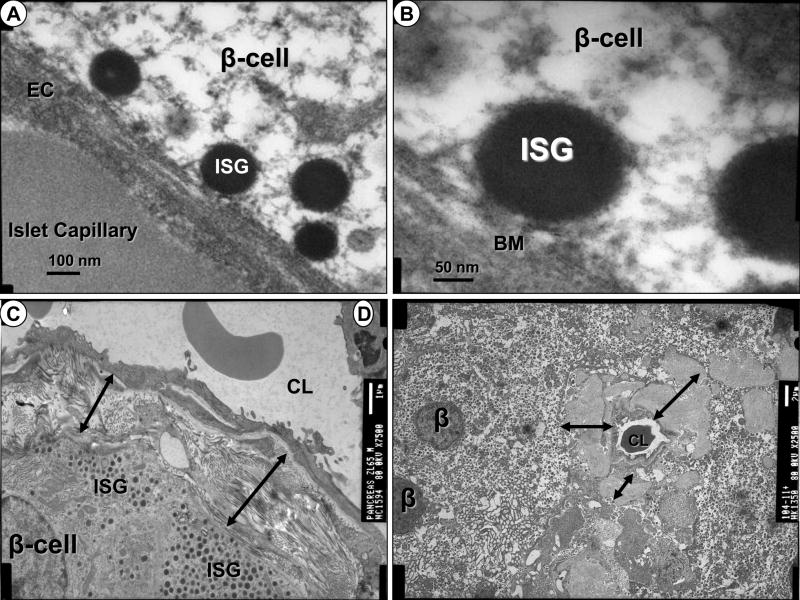

Figure 2. Cell – Matrix Communications: Lost.

Panels A and B represent the normal relationship of rolling, trafficking, tethering, docking and ultimately fusion of insulin secretory granules (ISG) between beta cells and islet capillaries in a rodent model. A. Magnification X60,000. Bar = 100nm. B. Magnification X150,000. Bar = 50nm. Panel C demonstrates pericapillary fibrosis of the islet capillary and note the fibrosis (double arrows) separates the β-cell and ISG from the capillary. Magnification X7500. Bar = 1 μm. Panel D also depicts the separation of the β-cell and ISG from the islet capillary due to islet amyloid deposition (double arrows). Magnification X2500. Bar = 2 μm. In both panels C and D the β-cell ISG appear to abruptly stop at the areas of fibrosis and islet amyloid deposition (double arrows). CL = capillary lumen.

Importantly, the cell-matrix connections – communications were observed to be lost due to widening and subsequent matrix fibrosis in the IEI of the db/db diabetic model (figure 1).

Matrix Communications: LOST

The peri-islet interstitium – IEI is a potential space that widens in db/db models resulting in the loss of cell-cell communications between islet and acinar cells in the pancreas (figure 1). In both the db/dbWT and the db/db diabetic models the IEI interstitium is continuous with the endoacinar and interlobular periacinar interstitium of the exocrine pancreas confirming an insulo – acinar - ductal connection, which may be lost due to remodeling fibrosis (figure 3).

Figure 3. Continuous Matrix Interstitium Connecting the Endocrine and Exocrine Pancreas: The Pancreatic Superhighway.

Panels A–D depict the continuous matrix connecting the islet via the islet exocrine interface (IEL) to the endoacinar interstitium (EaI) containing the microcirculation and ductal conduit structures to transport molecules and hormones supporting paracrine communication and acinar cell derived pancreatic enzymes to the gastrointestinal tract respectively in the db/dbWT control model. Note the pericyte process (Pp) traversing the IEI and the EaI in panel D, demonstrating a continuous matrix. Magnification X250 and bar = 5μm in panels A and B. Magnification X600 and Bar = 2μm in Panel C. Magnification X1200 and Bar = 1μm in Panel D.

Hypercellularity of the IEI and Early Fibrotic changes

The IEI in the db/dbWT contains a very loose areolar matrix with sparse unorganized collagen and reticular fibers, 4–5 capillaries (endothelial cells and their supporting pericytes) providing capillary connectivity and occasional unmylelinated neural cells. In contrast, the IEI in the db/db diabetic model becomes hypercellular consisting of 12–15 pericytes with their long cytoplasmic processes being the primary cell type and a few monocytic inflammatory cells (figure 4). Early organized fibrillar-banded collagen typical of early fibrosis was noted and closely associated with pericytes, which are known to be capable of differentiating into myofibroblast-like –pancreatic stellate cells in other models (3, 9) (figure 5).

Figure 4. Islet Exocrine Interface Hypercellularity with Pericytes and Inflammatory Cells in the db/db Diabetic Model.

Panels A–M demonstrate the pericyte (Pc) hypercellularity of the db/db diabetic model in the islet exocrine interface (IEI) region (14–15 Pc in the db/db diabetic model vs. 4–5 in the db/dbWT).

Panels N–Q depict the presence of inflammatory cells in the IEI. There were no inflammatory cells in the db/db WT control model. This collage of 16 images represent variable magnifications and bar measurements.

Figure 5. Islet Exocrine Interface Fibrosis.

Panels A–D depict the close association of the pericyte (Pc) to early banded fibrillar collagen formation (X) with panel D demonstrating the extrusion of a collagen fiber from a Pc. Panels E–H demonstrate early deposition of banded fibrillar collagen (X) representative of early fibrosis (X) and panel H depicts a higher magnification of this fibrosis as a representative of the fibrosis in panels E–G. Unmyelinated neural elements are represented in panels E and F. This collage of 8 images represents variable magnifications and measurements.

Pancreatic IEI and Interlobular Periacinar Interstitial Fibrosis

The IEI early fibrosis at seven weeks in the db/db diabetic model portends the development of significant fibrosis in the IEI, interlobular and endoacinar interstitium in the db/db model as it ages as well as other T2DM rodent models and humans with T2DM (figure 6). For example by 14 weeks the IEI fibrosis in the db/db diabetic model known to overexpress Angiotensin II (Ang II) was markedly increased as compared to db/dbWT controls and interestingly was abrogated with an angiotensin receptor blocker candesartan (12). Additionally, the Ren2 rat model transfected with the mouse renin gene at 9 weeks developed interlobular periacinar interstitial fibrosis while there was only early organized collagen deposition in the IEI indicating a temporal – spatial deposition of collagen and fibrosis in this transgenic model of local tissue Ang II overexpression (3, 4). The fibrosis in the Ren2 model seemed to originate in the perivascular -periductal areas of the interlobular periacinar interstitium and emanate to the surrounding loose areolar matrix of the exocrine interstitium. The involvement of a local pancreatic renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) is not to be underestimated regarding the important role it plays in oxidative stress, vasoconstriction, interlobular periacinar, IEI and eventual endoacinar interstitial remodeling fibrosis (3, 4, 8, 10–18).

Figure 6. Endocrine – Exocrine Fibrosis in Humans with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus.

Panels A–B demonstrate multiple areas of fibrosis present in the endocrine and exocrine pancreas in a 58 year old female patient with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Panel A is stained with picrosirius red and bright light imaging is represented. Panel B represents the same image viewed with crossed polarized light emphasizing types I and III collagen (gold color) with the cellular contents no longer visible. This image highlights the amount of fibrosis (gold color) as well as intra-islet fibrosis and loss of acinar-parenchymal tissue due to fibrosis and adipose replacement.

Panels C–D depict the same patient with Verhoeff Van Giesson (VVG) staining to highlight the crimson red islet exocrine interface (IEI), endoacinar interstitium (EaI) and interlobular periacinar interstitium (IPaI) fibrosis. In panel D it is apparent that the entire interstitial matrix –pancreatic superhighway is completely fibrosed including the perivascular and periductal tissue in the upper right hand corner. Also, note in addition to fibrous scarring replacement the adipose tissue replacement (adipo) also contributes to the loss of parenchymal tissue.

Pancreatic Extracellular Matrix Remodeling Fibrosis

Irrespective of the etiological agent(s), pancreatic ECM remodeling fibrosis represents a final common pathway as in most chronic diseases leading to destruction of tissue architecture, function and organ failure as in T2DM.

In the db/db obese diabetic model and in humans with T2DM there is both islet and exocrine wounding. The major offending agents responsible for this wounding in the db/db diabetic model and other obese T2DM animal rodent models are Ang II, nicotine adenine dinucleotide phosphate (reduced) NAD(P)H oxidase activation via the angiotensin type 1 receptor (At1R), including upregulation of the mineralocorticoid receptor, hyperglycemia and reactive oxygen species (ROS) – oxidative stress responsible for activating MMP and instigating remodeling fibrosis. This chronic wounding results in the persistent activation of the innate-classic tissue wound healing response characterized by inflammation, granulation tissue and matrix formation including the recapitulation of embryonic genetic memory (3, 4, 9, 13–15).

The ensuing matrix fibrosis is associated with loss of ECM elasticity and stiffening, which affects conduit structures including capillaries and exocrine ducts, impaired diffusion of molecules such as nitric oxide and hormones such as insulin, impaired cellular migration such as newly synthesized periductal β-cells, contraction and parenchymal acinar loss due to replacement fibrous and adipose tissue replacement as depicted in figure 6. These multiple changes due to the deposition of organized fibrillar-banded collagen result in lost ECM transportation and communications of the intra-islet, peri-islet – IEI, endoacinar and interlobular periacinar interstitium.

Postmortem histological changes in the pancreata of human and rodent models (db/db, ZDF, Ren2 and HIP) of T2DM typically include intra-islet, IEI, endoacinar and interlobular periacinar ECM fibrosis. Concurrently, there exists islet amyloid deposition in the human and HIP models, exocrine and endocrine adipose replacement, loss of β-cell mass due to apoptosis, replacement fibrosis and islet amyloid deposition. Contemporaneously, there is loss of the exocrine parenchyma due to apoptosis, replacement fibrosis, adipogenesis and a full spectrum of vascular remodeling changes including arteriosclerosis, arteriolosclerosis and atherosclerosis (13, 16–18) (figure 6). Importantly, when these above findings were carefully scrutinized by statistical analysis the most significant finding was pancreatic interstitial fibrosis with a p value of < than 0.001 (18).

Pancreatic Pericytes as Pancreatic Stellate Cells

The discussion of fibrosis in the pancreas would be incomplete without discussing the role of the fibrogenic pericyte cell (figure 4, 5) and its relation to the profibrogenic pancreatic stellate cell. The pancreatic stellate cell was originally described a decade ago (19, 20) and has been of topical interest regarding pancreatic fibrosis in humans and various animal models of acute and chronic pancreatitis (21, 22). These triangular cells are typically located at the base of acinar cells within the endoacinar and interlobular periacinar interstitium in contrast to their more elongated appearance within the IEI. The pericytes – pancreatic stellate cells are closely associated with endothelial cells of the microcirculation where they appear to connect capillaries within the interstitium. Once activated by injurious stimuli such as oxidative stress – ROS they differentiate into profibrotic cells capable of synthesizing collagen type 1 and III and fibronectin (figures 3, 4, 5) (3, 9, 17, 23). The pool of fibrogenic pancreatic stellate cells have classically included native fibroblasts, circulating stem cells, epithelial-acinar mesenchymal transition cells and now the proposed adult mesenchymal stem cell-like pleuripotent pericyte.

The potential role of the pericyte as a pancreatic stellate cell - myofibroblast precursor in pancreatic fibrosis is supported by a number of studies, which have highlighted the in vivo capacity of the pericyte to act as mesenchymal precursor cells (19, 24–33). These studies include liver and renal fibrosis, where resident pericyte cells have been shown to differentiate into myofibroblasts (24, 29).

The findings of IEI pericyte hypercellularity (due to hyperplasia and or migration) and the close association with early fibrillar-banded collagen in the db/db diabetic model, Ren2 (3, 4) and the HIP (9) rodent models of T2DM suggest that the pericyte is playing an important role in IEI fibrosis. In addition to being supportive mural cells of the capillary endothelium and their important role in connecting capillaries throughout the endocrine and exocrine pancreas, our recent research and observational findings presented herein, strongly suggest that pericytes may be the pancreatic stellate cell (3, 9).

These recent findings further demonstrate, that intra-islet, IEI, endoacinar and interlobular periacinar interstitial fibrosis appear to originate around capillaries in the islet (pericapillary fibrosis) (figure 2C), IEI and the triad of small arteries, veins and ducts within the interstitium. This early perivascular-periductal fibrosis appears to emanate from these regions and involve the remainder of the loose areolar interstitial matrix and progresses to remaining regions. These findings also suggest that early fibrosis in the interstitium contemporaneously involve both vascular and ductal structures. Importantly, these findings support our previously held notion that the mural pericyte may be the linchpin linking vascular oxidative stress to interstitial – organ fibrosis and pancreatic failure (3).

Insulo-Acinar-Ductal-Portal Vascular Pathway and Insulo-Acinar-Ductal-Pancreatic Enzyme-Incretin-Gut Hormone Axis Communications: LOST

The insulo-acinar-ductal-portal vascular pathway has been known and verified by matrix reconstruction studies for almost 3 decades (34, 35). The microcirculation of the endocrine and exocrine pancreas travels through the continuous loose areolar matrix of the interstitial regions. Acini secrete their digestive pancreatic enzyme(s) (PE) into a central lumen lined by centroacinar cells. These small intercalated ducts drain into the intralobular, interlobular and the main -accessory pancreatic ducts within the interstitium to deliver their PE contents to the gastrointestinal tract (gut) to aid in the digestion of oral nutrients (fat, carbohydrates and proteins). These properly digested nutrients are capable of activating the enteroendocrine L-cells of the ileum and colon to synthesize and secrete one of the incretin’s, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1).

The matrix connections are the critical structural pathways for each of these conduit systems and interstitial fibrosis has a detrimental effect not only on the microcirculation but also the ductal system resulting in impaired insulin delivery to the hepatic portal system and delivery of PE to the gut.

When pancreatic endocrine – exocrine tissue was viewed with low magnification TEM, the less electron dense matrix of the endoacinar and interlobular periacinar interstitium appeared similar to a roadmap, which we now term the pancreatic superhighway (figure 3). Further, the matrix roadmap analogy allows envisioning fibrosis as a roadblock to the pancreatic superhighway impairing cellular-molecular transportation and lost communication (figure 6).

Clinical Implications of These Findings

Pericapillary fibrosis and islet amyloid deposition in the islet capillaries and efferent islet venules could certainly interfere with the delivery of insulin and result in a delay of 1st phase insulin secretion in T2DM (36). Likewise, exocrine pancreatic periductal fibrosis could interfere with the delivery of PE to the gut and interfere with the proper digestion of orally ingested nutrients as well as interfere with the microcirculation of the pancreas. Therefore, interstitial fibrosis may result in the loss of not only the endocrine effects associated with the microcirculation but also the cross-talk paracrine effects that islet, acinar and ductal cells share (2).

The Incretin Effect: Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) - [7–36 amide]

As interstitial fibrosis progresses, there is increasing impairment of insulo-acinar-portal vascular pathway (microcirculation) and insulo-acinar-ductal-pancreatic enzyme-incretin-gut hormone axis (ductal system) transportation of cells and molecules (islet hormones including insulin and PE) and paracrine signaling communications. As a result, islet hormones including insulin’s trophic effects on acinar and ductal cells may be impaired or lost. Also, the roadblock to the pancreatic superhighway may impair PE secretion to the gut and interfere with the proper digestion of oral nutrients and may decrease the stimulatory effect on the enteroendocrine L-cells in the ileum and colon to synthesize and secrete GLP-1 (figure 7). Interestingly, GLP-1 is known to be decreased in prediabetes and overt T2DM in humans (37, 38) and recently, investigators have demonstrated an increase in GLP-1, plasma insulin, plasma C-peptide, and total insulin following PE replacement therapy. These findings suggest that the secretion of GLP-1 is under the influence of the proper digestion and absorption of nutrients in the small bowel and that PE supplementation increases GLP-1 and insulin secretion (39).

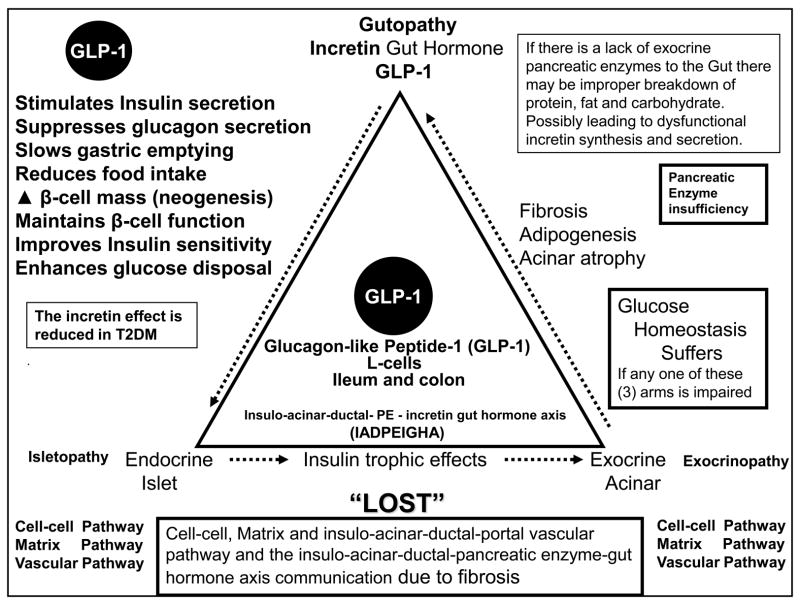

Figure 7. The Endocrine – Exocrine – Incretin Gut Hormone Axis: Gutopathy.

This image demonstrates the important interaction between the pancreatic endocrine-islet (isletopathy) – exocrine-acinar (exocrinopathy) and the incretin gut hormone axis (gutopathy) function. If anyone of these three important arms is impaired or disrupted by fibrosis, glucose homeostasis suffers. CMS = cardiometabolic syndrome; T2DM = type 2 diabetes mellitus.

The “incretin effect” is a term that has persisted in the literature for over 4 decades and was initially used to describe the finding that an oral glucose load produces a greater insulin response than an intravenous glucose infusion resulting in an equivalent glucose rise to the orally ingested glucose (40, 41). Since only the incretin hormone GLP-1 and not the glucose-dependent insulinotropic hormone (GIP) have been found to be reduced in T2DM patients following an oral glucose load we have focused our attention on the GLP-1 (42, 43). Further, GIP does not stimulate insulin secretion in T2DM patients in physiologic or pharmacological doses (43).

There are multiple defects in insulin’s secretion and signaling in T2DM; however, the reduced or absent incretin effect (contributing between 25–60% to the insulin secretory response following an oral glucose challenge) (43) has only recently become of clinical importance due to the availability of GLP-1 mimetics and dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP-IV) inhibitor therapies. These newer treatment options (incretin mimetics and DDP-IV inhibitors) have expanded the treatment modalities based on the early findings of GLP-1 being reduced in prediabetes and overt T2DM (36, 37). Importantly, these newer therapies for patients with T2DM have resulted in an increased quality of life and have allowed many patients with T2DM to achieve their HbA1C goals.

Concurrent with our recent findings there were publications that demonstrated the presence of impaired pancreatic exocrine function in T2DM as measured by fecal elastase-1 levels (44–46). Fecal elastase-1 levels (normal >200 μg/g) were decreased to less than 100 μg/g in patients with T2DM (12–20 %) and T1DM (26–44%) (44), while a different study found that fecal elastase-1 levels were decreased in 28% in the T2DM population (46). Importantly, these data support the association of T2DM with exocrine insufficiency and pancreatic diabetes or type three c diabetes mellitus (T3cDM) (44, 45).

Conclusions

These observational studies of the db/db diabetic obese mouse model coupled with findings in the Ren2, HIP and Zucker rodent models demonstrate structural changes, which likely reduce pancreatic endocrine – exocrine communication and function. Structural changes include a widening and hypercellularity consisting primarily of pericytes and occasional inflammatory cells within the IEI. Additionally, the pericyte is associated with the early formation of organized banded fibrillar collagen of early fibrosis. The pancreatic matrix is continuous and appears similar to roadmap, with the matrix representing a pancreatic superhighway. It is known that fibrosis of the IEI and panceatic interstitium develop as these animal models age and as T2DM progresses in humans (figure 6).

In summary the pancreas is connected by a continuous matrix supporting communication and transportation of molecules and cells. Interstitial matrix remodeling fibrosis creates a roadblock to this continuous pancreatic superhighway and results in lost connections and communication. The images presented make it obvious that we are dealing with a continuously integrated organ, in which, endocrine and exocrine glands are structurally and functionally interconnected with a continuous matrix supporting the microcirculation and ductal function allowing for a well-orchestrated functional response.

GLP-1 mimetics and DPP-IV inhibitors therapies act to bypass to these fibrotic roadblocks and if we can decrease the fibrotic roadblocks by decreasing the multiple metabolic toxicities including glucotoxicity, oxidative stress and restoring the incretin effect earlier in the impaired glucose tolerance – prediabetes phase we may be able to delay the natural progressive nature of T2DM. No longer can we assume that diarrhea in diabetes is due to diabetic neuropathy unless pancreatic insufficiency is shown not to be present.

We suggest the use of PE supplementation in patients who have demonstrated pancreatic insufficiency and further suggest that early PE supplementation may have a preventive effect on the natural progressive history of T2DM in patients with impaired glucose tolerance -prediabetes.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH (R01 HL73101-01A1), Veterans Affairs Merit System (0018), Novartis Pharmaceuticals (JRS) and Missouri Kidney Program and Veterans Affairs VISN 15 (AW-C).

References

- 1.Pieler T, Chen Y. Forgotten and novel aspects in pancreas development. Biol Cell. 2006;98(2):79–88. doi: 10.1042/BC20050069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertelli E, Bendayan M. Association between endocrine pancreas and ductal system. More than an epiphenomenon of endocrine differentiation and development? J Histochem Cytochem. 2005;53:1071–1086. doi: 10.1369/jhc.5R6640.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayden MR, Karuparthi PR, Habibi J, et al. Ultrastructural islet study of early fibrosis in the Ren2 rat model of hypertension. Emerging role of the islet pancreatic pericyte-stellate cell. JOP. 2007;8(6):725–738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Habibi J, Whaley-Connell A, Hayden MR, et al. Renin Inhibition Attenuates Insulin Resistance, Oxidative Stress, and Pancreatic Remodeling in the Transgenic Ren2 rat. Endocrinology. 2008 Jul 24; doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0070. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayden MR, Karuparthi PR, Manrique CM, Lastra G, Habibi J, Sowers JR. Longitudinal ultrastructure study of islet amyloid in the HIP rat model of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2007;232(6):772–779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neubauer N, Kulkarni RN. Molecular approaches to study control of glucose homeostasis. ILAR J. 2006;47(3):199–211. doi: 10.1093/ilar.47.3.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou YP, Madjidi A, Wilson ME, et al. Matrix metalloproteinases contribute to insulin insufficiency in Zucker diabetic fatty rats. Diabetes. 2005 Sep;54(9):2612–2619. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.9.2612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayden MR, Stump CS, Sowers JR. Introduction: organ involvement in the cardiometabolic syndrome. J Cardiometab Syndr. 2006;1(1):16–24. doi: 10.1111/j.0197-3118.2006.05454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayden MR, Karuparthi PR, Habibi J, et al. Ultrastructure of islet microcirculation, pericytes and the islet exocrine interface in the HIP rat model of diabetes. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2008 Jul 18; doi: 10.3181/0709-RM-251. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakamura M, Kitamura H, Konishi S, et al. The endocrine pancreas of spontaneously diabetic db/db mice: microangiopathy as revealed by transmission electron microscopy. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1995;30(2):89–100. doi: 10.1016/0168-8227(95)01155-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayden MR, Whaley-Connell A, Sowers JR. Role of Angiotensin II in Diabetic Cardiovascular and Renal Disease. Current Opinions in Endocrinology and Diabetes. 2006;13:135–140. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shao J, Iwashita N, Ikeda F, et al. Beneficial effects of candesartan, an angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker, on beta-cell function and morphology in db/db mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;344(4):1224–1233. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayden MR, Sowers JR. Pancreatic Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System in the Cardiometabolic Syndrome and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. J Cardiometab Syndr. 2008 Summer;3(3):xx–xx. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-4572.2008.00006.x. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayden MR, Sowers JR. Treating hypertension while protecting the vulnerable islet in the cardiometabolic syndrome. Journal of the American Society of Hypertension. 2008;2(4):239–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark RA. Cutaneous tissue repair: basic biologic considerations. I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13(5 Pt 1):701–725. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(85)70213-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayden MR, Sowers JR. Redox Imbalance in Diabetes. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9(7):865–857. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayden MR, Sowers JR. Isletopathy in type 2 diabetes mellitus: implications of islet RAS, islet fibrosis, islet amyloid, remodeling and oxidative stress. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9(7):891–910. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao HL, Lai FMM, Tong PC, et al. Prevalence and clinicopathological characteristics of islet amyloid in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2003;52(11):2759–2766. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.11.2759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Apte MV, Haber PS, Applegate TL, et al. Periacinar stellate shaped cells in rat pancreas: identification, isolation, and culture. Gut. 1998;43:128–33. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.1.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bachem MG, Schneider E, Gross H, et al. Identification, culture, and characterization of pancreatic stellate cells in rats and humans. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:421–32. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70209-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Omary MB, Lugea A, Lowe AW, Pandol SJ. The pancreatic stellate cell: a star on the rise in pancreatic diseases. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:50–59. doi: 10.1172/JCI30082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pezzilli R. Pancreatic stellate cells and chronic alcoholic pancreatitis. JOP. 2007;8:254–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stevens T, Conwell DL, Zuccaro G. Pathogenesis of chronic pancreatitis: an evidence-based review of past theories and recent developments. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(11):2256–2270. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmitt-Graff A, Kruger S, Bochard F, Gabbiani G, Denk H. Modulation of alpha smooth muscle actin and desmin expression in perisinusoidal cells of normal and diseased human livers. Am J Pathol. 1991;138:1233–1242. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doherty MJ, Ashton BA, Walsh S, Beresford JN, Grant ME, Canfield AE. Vascular pericytes express osteogenic potential in vitro and in vivo. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13:828–838. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.5.828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ivarsson M, Sundberg C, Farrokhnia N, Pertoft H, Rubin K, Gerdin B. Recruitment of type I collagen producing cells from the microvasculature in vitro. Exp Cell Res. 1996;229:336–349. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.0379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sundberg C, Ivarsson M, Gerdin B, Rubin K. Pericytes as collagen-producing cells in excessive dermal scarring. Lab Invest. 1996;74:452–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Richardson RL, Hausman GJ, Campion DR. Response of pericytes to thermal lesion in the inguinal fat pad of 10-day-old rats. Acta Anat (Basel) 1982;114:41–57. doi: 10.1159/000145577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hattori M, Horita S, Yoshioka T, Yamaguchi Y, Kawaguchi H, Ito K. Mesangial phenotypic changes associated with cellular lesions in primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997;30:632–638. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(97)90486-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allt G, Lawrenson JG. Pericytes: cell biology and pathology. Cells Tissues Organs. 2001;169:1–11. doi: 10.1159/000047855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sims DE. The pericyte. A review. Tissue Cell. 1986;18:153–174. doi: 10.1016/0040-8166(86)90026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shepro D, Morel NM. Pericyte physiology. FASEB J. 1993;7:1031–1038. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.7.11.8370472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li AF, Sato T, Haimovici R, Okamoto T, Roy S. High glucose alters connexin 43 expression and gap junction intercellular communication activity in retinal pericytes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:5376–5382. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yaginuma N, Takahashi T, Saito K, Kyogoku M. Reconstruction study of the structural plan of the human pancreas. (Japanese text with English abstract) Jap J Gastroenterol. 1981;78:1282–1292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ohtani O. Three-dimensional organization of the connective tissue fibers of the human pancreas: a scanning electron microscopic study of NaOH treated-tissues. Arch Histol Jpn. 1987;50(5):557–566. doi: 10.1679/aohc.50.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hayden MR. Islet Amyloid and Fibrosis in Cardiometabolic Syndrome and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. J Cardiometab Syndr. 2007;2(1):70–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-4564.2007.06159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laakso M, Zilinskaite J, Hansen T, et al. for the EUGENE2 Consortium. Insulin sensitivity, insulin release and glucagon-like peptide-1 levels in persons with impaired fasting glucose and/or impaired glucose tolerance in the EUGENE2 study. Diabetologia. 2008;51(3):502–511. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0899-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Knop FK, Vilsbøll T, Højberg PV, et al. Reduced incretin effect in type 2 diabetes: cause or consequence of the diabetic state? Diabetes. 2007;56(8):1951–1959. doi: 10.2337/db07-0100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Knop FK, Vilsbøll T, Larsen S, et al. Increased postprandial responses of GLP-1 and GIP in patients with chronic pancreatitis and steatorrhea following pancreatic enzyme substitution. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292(1):E324–E330. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00059.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Creutzfeldt W. The incretin concept today. Diabetologia. 1979;16:75–85. doi: 10.1007/BF01225454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elrick H, Stimmler L, Hlad CJ, Arai Y. Plasma insulin response to oral and intravenous glucose administration. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1964;24:1076–1082. doi: 10.1210/jcem-24-10-1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nauck M, Stockmann F, Ebert R, Creutzfeldt W. Reduced incretin effect in type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes. Diabetologia. 1986;29(1):46–52. doi: 10.1007/BF02427280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nauck MA, Heimesaat MM, Orskov C, Holst JJ, Ebert R, Creutzfeldt W. Preserved incretin activity of glucagon-like peptide 1 [7–36 amide] but not of synthetic human gastric inhibitory polypeptide in patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest. 1993;91(1):301–307. doi: 10.1172/JCI116186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hardt PD, Brendel MD, Kloer HU, Bretzel RG. Is pancreatic diabetes (type 3c diabetes) underdiagnosed and misdiagnosed? Diabetes Care. 2008;31(Suppl 2):S165–169. doi: 10.2337/dc08-s244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hardt PD. Second giessen international workshop on interactions of exocrine and endocrine pancreatic diseases. Castle of Rauischholzhausen of the Justus-Liebig-university, Giessen (Rauischholzhausen), Germany. March 7–8, 2008. JOP. 2008;9(4):541–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yilmaztepe A, Ulukaya E, Ersoy C, Yilmaz M, Tokullugil HA. Investigation of fecal pancreatic elastase-1 levels in type 2 diabetic patients. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2005;16(2):75–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]