Abstract

Context: Parenteral administration of peptide GnRH analogs is widely employed for treatment of endometriosis and fibroids and in assisted-reproductive therapy protocols. Elagolix is a novel, orally available nonpeptide GnRH antagonist.

Objective: Our objective was to evaluate the safety, pharmacokinetics, and inhibitory effects on gonadotropins and estradiol of single-dose and 7-d elagolix administration to healthy premenopausal women.

Design: This was a first-in-human, double-blind, placebo-controlled, single- and multiple-dose study with sequential dose escalation.

Participants: Fifty-five healthy, regularly cycling premenopausal women participated.

Interventions: Subjects were administered a single oral dose of 25–400 mg or placebo. In a second arm of the study, subjects received placebo or 50, 100, or 200 mg once daily or 100 mg twice daily for 7 d. Treatment was initiated on d 7 (±1) after onset of menses.

Main Outcome Measures: Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and serum LH, FSH, and estradiol concentrations were assessed.

Results: Elagolix was well tolerated and rapidly bioavailable after oral administration. Serum gonadotropins declined rapidly. Estradiol was suppressed by 24 h in subjects receiving at least 50 mg/d. Daily (50–200 mg) or twice-daily (100 mg) administration for 7 d maintained low estradiol levels (17 ± 3 to 68 ± 46 pg/ml) in most subjects during late follicular phase. Effects of the compound were rapidly reversed after discontinuation.

Conclusions: Oral administration of a nonpeptide GnRH antagonist, elagolix, suppressed the reproductive endocrine axis in healthy premenopausal women. These results suggest that elagolix may enable dose-related pituitary and gonadal suppression in premenopausal women as part of treatment strategies for reproductive hormone-dependent disease states.

Oral administration of the nonpeptide GnRH antagonist, elagolix, to premenopausal women results in transient suppression of gonadotropins and more sustained suppression of estradiol.

Peptide analogs of GnRH are now widely used in a variety of clinical applications for suppression of the reproductive endocrine axis (1,2,3). Continuous administration of peptide agonists (typically as depot formulations) cause the down-regulation of pituitary gonadotropin secretion and profound suppression of gonadal function after a stimulatory phase of 1–2 wk (4,5). Although complete gonadal suppression is desirable for treatment of sex steroid-dependent cancers of the prostate or breast, nonmalignant conditions (such as endometriosis or uterine fibroids) can be treated by maintaining estrogen at low, but not necessarily menopausal, levels (6). Accordingly, various add-back strategies have been successfully employed where GnRH agonist gonadal suppression is accompanied by coadministration of estrogens, progestins, or combinations to relieve menopausal symptoms (such as hot flashes) and prevent bone loss (7,8). However, although add-back hormonal levels can be controlled, agonist-induced down-regulation offers limited opportunity to control the degree of hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) suppression, although some range of suppression has been achieved with draw-back approaches (9).

Peptide GnRH antagonists immediately reduce gonadal steroid levels (10) and avoid the initial stimulatory phase of the agonists, eliminating the flare in symptoms (11,12) and resulting in more rapid onset of therapeutic effect (13,14). When used as part of in vitro fertilization protocols, frequency of injection and duration of treatment are reduced compared with peptide agonists (2). Varying the dose of an antagonist may also enable a degree of control over the extent of pituitary suppression and hence control over circulating levels of estrogens (15,16).

However, because of their peptide structure, existing GnRH antagonists require frequent injections or implantation of long-acting depots. Drawbacks include injection site reactions and inability to discontinue therapy should tolerability or safety concerns arise. To develop orally active GnRH antagonists, several groups have explored nonpeptide, small molecule structures with high affinity for the GnRH receptor (for a recent review see Ref. 17). We have previously described gonadotropin suppression in postmenopausal women by oral administration of a first-generation nonpeptide GnRH antagonist, NBI-42902 (18). However, in subsequent studies, this compound showed inhibition of the liver P450 enzymes CYP3A4 and CYP2C19 leading to discontinuation of its clinical development. This liability was overcome with a second-generation nonpeptide GnRH antagonist, elagolix, R-(+)-4-{2-[5-(2-fluoro-3-methoxy-phenyl)-3-(2-fluoro-6-trifluoromethyl-benzyl)-4-methyl-2,6-dioxo-3,6-dihydro-2H-pyrimidin-1-yl]-1-phenyl-ethylamino}-butyrate (19). It is a highly potent (KD = 54 pm) antagonist of the human GnRH receptor and suppresses LH in castrated macaques after oral administration. In the present study, we evaluate the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and effect on gonadotropins and estrogen of this compound after oral administration to premenopausal women in midfollicular phase of the menstrual cycle.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

All subjects participating in the study gave written informed consent before screening for eligibility. The study was approved by the local ethics committee, and clinical procedures were performed at MDS Pharma Services (Phoenix, AZ). Subjects were required to have a history of regular menstrual cycles (28 ± 2 d) for at least 2 yr and a positive ovulation test between d 11 and 16 of the menstrual cycle immediately preceding dosing. Each participant underwent a physical examination, including a pelvic examination.

A summary of subject demographics is provided in Table 1. Thirty healthy premenopausal female subjects participated in and completed the single-dose escalation phase of this study. Subject ages and weights ranged from 18–37 yr (mean ± sd = 27.8 ± 6.1 yr) and 50.4–76.0 kg (mean ± sd = 61.6 ± 6.2 kg), respectively. Body mass index (BMI) ranged from 19.5–27.4 kg/m2 (mean ± sd = 23.6 ± 2.1 kg/m2).

Table 1.

Selected demographic characteristics of subjects

| Study cohorts

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Single dose, n = 30 | Multiple dose, n = 25 | |

| Age (yr) | 27.8 ± 6.1 (18.0 – 37.0) | 25.6 ± 4.7 (19.0 – 39.0) |

| Height (cm) | 162 ± 7 (146 – 177) | 162 ± 7 (150 – 181) |

| Weight (kg) | 61.6 ± 6.2 (50.4 – 76.0) | 58.8 ± 7.7 (44.7 – 76.2) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.6 ± 2.1 (19.5 – 27.4) | 22.3 ± 2.2 (18.0 – 26.2) |

Data are presented as mean ± sd (range).

25 healthy premenopausal female subjects participated in, and 24 of these subjects completed, the multiple dose-escalation phase of this study. Subject ages and weights ranged from 19–39 yr (mean ± sd = 25.6 ± 4.7 yr) and 44.7–76.2 kg (mean ± sd = 58.8 ± 7.7 kg), respectively. BMI ranged from 18.0–26.2 kg/m2 (mean ± sd = 22.3 ± 2.2 kg/m2).

Study design

This was a phase I, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, sequential dose escalation study. Five cohorts of six subjects each received a single dose of elagolix (25, 50, 100, 200, or 400 mg) or placebo (elagolix/placebo = 5:1). An additional three cohorts, each comprising six subjects, received once-daily doses of elagolix (50, 100, or 200 mg) or placebo (elagolix/placebo = 5:1) for 7 d. The final cohort of seven subjects received elagolix (100 mg) or placebo twice daily (elagolix/placebo = 5:2) for 7 d. The first multiple-dose cohort was enrolled after satisfactory safety results were observed for the first three single-dose cohorts. Initial administration was 7 ± 1 d after the onset of menstruation. Antagonist (or placebo) was administered at 0800 h after an overnight fast. Blood samples were collected at the indicated time points for serum hormone or plasma antagonist measurements.

Adverse events (AEs), including hot flashes, were characterized as mild, moderate, or severe: mild, causing no limitation of usual activities, and the patient may experience slight discomfort; moderate, causing some limitation of usual activities, and the patient may experience annoying discomfort; severe, causing inability to carry out usual activities, and the patient may experience intolerable discomfort or pain.

Assays

Plasma concentrations of elagolix and metabolite NBI-61962, R-(+)-4-{2-[5-(2-fluoro-3-hydroxy-phenyl)-3-(2-fluoro-6-trifluoromethyl-benzyl)-4-methyl-2,6-dioxo-3,6-dihydro-2H-pyrimidin-1-yl]-1-phenyl-ethylamino}-butyrate, were determined by a validated method (Neurocrine Biosciences, Inc., San Diego, CA) based on liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectroscopy. The lower and upper limits of quantification were 0.50 and 250.0 ng/ml, respectively. The precision (coefficient of variation) for elagolix ranged from 3.0–5.6% and for NBI-61962 ranged from 4.7–6.7% across concentrations and analytical batches. Mean accuracy (expressed as percent bias) for elagolix ranged from 0.8–0.9% and for NBI-61962 ranged from 0.5–0.7% across concentrations and analytical batches. Concentrations of elagolix are typically expressed as nanograms per milliliter of the free acid and can be converted to nanomoles per liter by multiplying by 1.58.

Serum concentrations of LH and FSH were determined by validated immunoassay methods using chemiluminescence (MDS Pharma Services, Lincoln, NE). The lower and upper limits of quantification for LH were 1.01 and 50.5 mIU/ml, respectively. The lower and upper limits of quantification for FSH were 2 and 49 mIU/ml, respectively.

Serum concentrations of estradiol (E2) were determined by a validated method (MDS Pharma Services, Montreal, Quebec, Canada) based on liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectroscopy. The lower and upper limits of quantification were 2.50 and 500 pg/ml, respectively.

Data analysis

Derived plasma and urine pharmacokinetic parameters were determined using standard noncompartmental methods from the available plasma and urine data of parent drug (elagolix) and metabolite (NBI-61962) from each individual subject. Parameter calculations were performed using WinNonlin Professional version 4.1 (Pharsight Corp., Mountain View, CA), with any values below the limit of quantitation set to zero before calculation.

This was a phase I safety and tolerability study without prespecified statistical tests or formal hypothesis testing. Post hoc analysis of serum hormone concentrations was carried out by ANOVA-based comparisons of mean values and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for comparisons of median values. Differences between elagolix dose groups and placebo at selected time points were tested for significance using a two-tailed t test. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS release 8.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Differences were considered significant if P < 0.05.

Results

Side effect and safety profile

A total of 55 healthy, regularly cycling women ranging in age from 18–39 yr were enrolled in the study. There were no relevant differences in the mean age, height, weight, or BMI among cohorts (Table 1).

Elagolix was well tolerated during both the single-dose escalation up to 400 mg and the multiple-dose escalation up to 200 mg once daily (qd) and 100 mg twice daily (bid) for 7 d. There were no clinically significant safety findings across dose groups, between single- and multiple-dose cohorts, or between elagolix and placebo treatments. One subject experienced a serious AE after a single dose of 25 mg elagolix (pelvic abscess, which was surgically drained at a hospital and not considered drug related). All subjects completed the study protocol with the exception of one who terminated before collection of d-9 samples due to family relocation.

Among the single-dose cohorts, the most frequently experienced AEs were headache (four of 25 elagolix and one of five placebo) and nausea (two of 25 elagolix and two of five placebo). Among the multiple-dose cohorts of the study, the most frequently experienced AEs overall were headache (15 of 20 elagolix and three of five placebo), abdominal pain (six of 20 elagolix and zero of five placebo), and hot flashes. The majority of AEs were reported as mild in intensity and a few as moderate; none was reported as severe. Because of the prior history of histamine-related AEs associated with peptide antagonists, it is interesting to note that the nonpeptide, elagolix, showed little evidence of similar problems. The only AE that could remotely be attributed to a histamine effect was one subject reporting a small rash on left arm shortly after oral administration of a single dose of elagolix (100 mg). Other nonpeptide GnRH antagonists do not exhibit histamine-releasing activity using in vitro rat mast cell assays (17,20), and elagolix is inactive in this assay as well (unpublished observation).

Hot flashes were reported by subjects as AEs as described above. Six subjects receiving elagolix experienced hot flashes (all mild, except one moderate) during the treatment period. These appeared to be dose related (100 mg, one subject; 200 mg, two subjects; 100 mg bid, three subjects) and more prevalent in subjects with the lowest estrogen levels. Two subjects (both in the 100-mg bid group) experienced hot flashes on more than one treatment day (subject 61, six events on 5 d; subject 62, four events on 3 d). Elagolix was not associated with the high-intensity hot flashes that commonly occur with profound E2 suppression such as is achieved with GnRH agonist depots (21).

Elagolix plasma concentrations and pharmacokinetic parameters

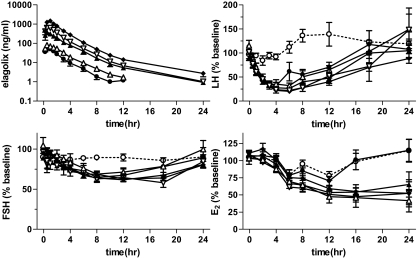

Mean elagolix plasma concentration-time profiles by dose group for the single-dose cohort are shown in Fig. 1. Summary statistics of plasma pharmacokinetic parameters by dose group for the single-dose cohort are provided in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Time course of plasma elagolix and serum gonadotropin and estrogen levels in the single-dose cohorts. Subjects were administered 25 (•), 50 (▵), 100 (▴), 200 (▿), or 400 (♦) mg elagolix or placebo (○) at time zero. Data shown are mean (± sem). Changes in LH, FSH, and E2 are shown as the mean percentage of each individual’s average predose serum concentration measured 24 h before and immediately before administration of antagonist.

Table 2.

Pharmacokinetic parameters in single-dose cohorts

| Parameter | 25 mg, n = 5 | 50 mg, n = 5 | 100 mg, n = 5 | 200 mg, n = 5 | 400 mg, n = 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC0-t (ng · h/ml) | 142 ± 65 | 242 ± 80 | 1062 ± 601 | 1793 ± 408 | 3770 ± 1502 |

| AUC0-∞ (ng · h/ml) | 146 ± 67 | 249 ± 81 | 1069 ± 603 | 1798 ± 407 | 3778 ± 1505 |

| Cmax (ng/ml) | 55.5 ± 23.8 | 86.3 ± 42.9 | 397 ± 241 | 707 ± 211 | 1504 ± 492 |

| Tmax (h) | 0.5 (0.5–1.0) | 0.5 (0.5–1.0) | 0.5 (0.3–1.0) | 0.5 (0.5–1.5) | 1.0 (0.5–1.1) |

| t1/2 (h) | 2.4 ± 0.7 | 2.6 ± 1.1 | 6.1 ± 2.1 | 5.4 ± 1.4 | 6.3 ± 2.3 |

| MRT (h) | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 3.0 ± 0.4 | 3.2 ± 0.3 | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 2.9 ± 0.5 |

Data are presented as mean ± sd, except for Tmax, which is presented as median (range). MRT, Mean residence time.

Elagolix was rapidly absorbed after oral administration, with median time of maximum plasma concentration (Tmax) values ranging from 0.5–1 h and reaching peak plasma concentrations from 55.5 ± 23.8 to 1504 ± 492 ng/ml (88 nm to 2.4 μm) in the 25- and 400-mg groups, respectively. Dose-dependent increases in both maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) and total [area under the curve (AUC)] exposure measures were observed.

Summary statistics of elagolix plasma pharmacokinetic parameters by dose group for the multiple dose cohort are provided in Table 3. The exposure of the 50- and 200-mg groups were comparable to those obtained in the corresponding single-dose cohorts. The 100-mg group showed lower exposure (AUC0-∞ = 466 ± 150 ng · h/ml) compared with the corresponding 100-mg group in the single-dose cohort (AUC0-∞ = 1069 ± 603 ng · h/ml). Little or no plasma accumulation and apparent time-invariant pharmocokinetics were observed over the 7 d of dosing for both the qd and bid regimens.

Table 3.

Pharmacokinetic parameters in multiple-dose cohorts

| Parameter | 50 mg, n = 5 | 100 mg, n = 5 | 200 mg, n = 5 | 100 mg (bid), n = 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | ||||

| AUC0-t (ng · h/ml) | 276 ± 102 | 458 ± 152 | 1554 ± 284 | 675 ± 131 |

| AUC0-∞ (ng · h/ml) | 283 ± 104 | 466 ± 150 | 1560 ± 285 | 685 ± 128 |

| Cmax (ng/ml) | 103 ± 52 | 205 ± 90 | 721 ± 121 | 281 ± 93 |

| Tmax (h) | 0.5 (0.5 – 2.0) | 0.5 (0.4 – 1.0) | 0.5 (0.3 – 0.5) | 0.7 (0.5 – 1.0) |

| t1/2 (h) | 5.7 ± 3.1 | 4.8 ± 2.6 | 4.2 ± 0.6 | 2.4 ± 0.6 |

| MRT (h) | 3.9 ± 1.1 | 3.2 ± 0.3 | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 2.5 ± 0.5 |

| Day 7 | ||||

| AUC0-t (ng · h/ml) | 305 ± 154 | 497 ± 115 | 1513 ± 199 | 690 ± 168 |

| AUC0-∞ (ng · h/ml) | 314 ± 162 | 507 ± 113 | 1530 ± 201 | 704 ± 169 |

| Cmax (ng/ml) | 112 ± 59 | 228 ± 96 | 626 ± 195 | 250 ± 72 |

| Tmax (h) | 0.6 (0.5 – 1.0) | 0.5 (0.5 – 0.5) | 0.5 (0.5 – 1.1) | 0.5 (0.5 – 1.0) |

| t1/2 (h) | 8.2 ± 6.9 | 7.0 ± 4.3 | 10.8 ± 14.0 | 2.2 ± 0.5 |

| MRT (h) | 4.1 ± 0.9 | 3.1 ± 0.8 | 3.3 ± 1.0 | 2.9 ± 0.3 |

Data are presented as mean ± sd, except for Tmax, which is presented as median (range). Pharmacokinetics parameter values for the 100-mg bid dose group were determined from data in the first 12 h after administration of compound and reflect the morning dose (100 mg) only. Most of the AUC from the afternoon dose would not have been measured due to the lack of blood samples between 12 and 24 h. MRT, Mean residence time.

Overall, exposure to high concentrations of elagolix in plasma was relatively brief. In the single-dose arm, mean plasma t1/2 ranged from 2.4–6.3 h. Generally comparable concentration-time profiles were observed across all qd dose levels tested on either d 1 or 7. Relatively low mean renal clearance of NBI-56418 was observed (range, 2.1–3.0 liters/h), with less than 3% of the administered doses excreted intact in urine.

The primary metabolite identified by in vitro microsomal studies was NBI-61962. This compound appeared in the systemic circulation rapidly after elagolix administration. However, relatively low plasma exposure to NBI-61962 was observed, with mean peak (Cmax) and total (AUC) exposure measures being 3% or less of the corresponding values for the parent drug. Because of its reduced potency (Ki = 3.5 nm) and relatively low plasma exposure, this metabolite is unlikely to contribute significantly to the biological activity of elagolix in this study.

HPG suppression in single-dose cohorts

Responses of LH, FSH, and E2 to oral administration of elagolix in the single-dose cohorts are shown in Fig. 1. At the lowest dose evaluated (25 mg), plasma concentrations of elagolix rapidly reach 55.5 ± 23.8 ng/ml (mean ± sem or 89 nm) which are more than 1000-fold excess of the affinity of the antagonist for the GnRH receptor (KD = 54 pm). Accordingly, LH concentrations begin to decline almost immediately. The rates of decline of all elagolix dose groups are similar and consistent with the rate of clearance of LH from the circulation (22). These data suggest that all dose groups achieve immediate blockade of the GnRH receptor. By 4 h after antagonist administration, LH levels of 22–35% of predose baseline are achieved in all groups receiving antagonist (P < 0.0001 vs. placebo). In contrast, LH levels of subjects receiving placebo are relatively unchanged. After 4–6 h, serum LH levels begin to recover with higher doses of antagonist resulting in more prolonged suppression. However, all groups return to approximately baseline levels by 24 h, consistent with reduced plasma levels of the antagonist. Thus, a transient suppression of LH is achieved, and varying the dose of antagonist controls the duration of suppression throughout the day.

FSH levels follow a similar pattern to LH although suppressed to a lesser extent and declining more slowly. All groups receiving antagonist show reduced FSH (62–71% of baseline) between 8 and 12 h (P < 0.02 vs. placebo). This is consistent with slower removal of FSH from the circulation and has been observed repeatedly with peptide GnRH antagonists (23).

In contrast to gonadotropins, E2 in the elagolix-treated subjects receiving 50, 200, or 400 mg remains partially suppressed (42–65% of baseline) at 24 h (P < 0.02 vs. placebo). Suppression of E2 in the 100-mg group does not quite reach statistical significance (P = 0.057 vs. placebo). Differences from placebo in these groups were no longer apparent by 48 h (data not shown). Mean E2 concentrations of the 25-mg group appeared similar to placebo. Although it appears that LH may begin to break through antagonist blockade at the 6-h time point in this dose group and has returned to normal by 18 h, the basis for the difference in E2 suppression between these subjects and those receiving higher doses of elagolix remains unclear. Likely, additional studies involving larger numbers of subjects and possibly more frequent blood sampling will be required to characterize the pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic relationships between antagonist and gonadotropin concentrations and the resulting suppression of E2.

HPG suppression in multiple-dose cohorts

Data from the single-dose cohorts suggested that transient suppression of gonadotropins by oral administration of at least 50 mg elagolix could result in more prolonged suppression of estradiol synthesis. Accordingly, as safety data from the single-dose escalation became available, subjects were initiated in the multiple-dose cohorts.

Median gonadotropin and E2 levels on the day before and during the 7-d treatment and subsequent follow-up periods are shown in Fig. 2. Similar to the single-dose cohorts, LH is rapidly suppressed, reaching a nadir between 4 and 6 h after administration of the compound (Fig. 2, right). At these times, LH levels frequently approached the limit of detection of the assay (1 mIU/ml) in the treated groups. However, LH levels return to predose levels (or above) by the next morning in the qd cohorts as illustrated by mean individual LH values of 103 ± 12 to 149 ± 23% in these cohorts compared with 98 ± 4% in placebo. The 100-mg bid cohort continued to show some level of suppression at this time point (77 ± 13%). FSH levels after initial antagonist administration are similarly suppressed and recover, with the exception of the 100-mg bid cohort where subjects continued to show suppression of FSH (74 ± 7% of individual baselines) compared with placebo (105 ± 9%) in the predose serum sample the following morning. All cohorts and all individuals receiving elagolix (with the exception of one subject receiving 200 mg qd who will be discussed below) showed a reduction from baseline E2 concentrations on the first day after administration of elagolix.

Figure 2.

Effect of elagolix on serum gonadotropin and estrogen levels over 7 d of treatment. Subjects were administered 50 (▵), 100 (▴), or 200 (▿) mg elagolix qd, 100 mg (▾) bid, or placebo (○) for 7 d beginning around 0800 h on d 0. Subjects were scheduled such that d 0 was 7 ± 1 d after onset of spontaneous menstruation. Median hormone levels of each dose group are shown (error bars indicate interquartile range). Right panels show the same data as left panels but with an expanded x-axis to see dynamics of hormonal responses on d 1 and 2. Some points are slightly offset along the x-axis for clarity.

Less frequent sampling data are available for d 2–7 of treatment. Although samples at 6 h (E2) and 12 h (LH and FSH) were obtained on d 2, sampling frequency for hormones was reduced to once daily (immediately before treatment) for the remaining treatment and follow-up period. Hence, daily hormone values during this period were obtained at a time when antagonist concentrations are at a minimum, and the transient daily excursion to reduced gonadotropin levels would not be observed based on the more frequent sampling data from d 1. Thus, although d 1 suppression of LH and FSH is apparent in all cohorts, further suppression in d 2–7 of treatment is not observed (Fig. 2). Rather, the 50- and 100-mg cohorts may show some apparent elevation of predose LH and FSH levels, respectively.

In contrast, E2 levels appear suppressed in the 50- and 200-mg qd and 100-mg bid cohorts, whereas E2 levels in the placebo cohort continue to rise, consistent with follicular development. However, only the 100-mg bid group showed consistent statistically significant suppression compared with placebo for most of the treatment period (P < 0.05 for d 2–7). Despite an initial decline in E2 levels of subjects in the 100-mg qd cohort, median levels tended to rise in parallel with the placebo group, albeit perhaps somewhat delayed. After elagolix discontinuation, serum E2 levels rose in all dose groups over the course of d 8–10. All evaluable subjects menstruated within 35 d of initial elagolix (or placebo) administration.

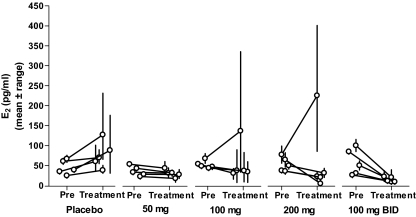

Figure 3 shows mean (± range) E2 levels before and during treatment for all individuals in the multiple-dose arm of this study. Individuals receiving placebo started with plasma E2 concentrations between 24 and 75 pg/ml, and all reach higher concentrations over the next 7 d, consistent with normal progression of the menstrual cycle. However, in all four elagolix-treated groups, most women maintained or lowered mean E2 levels during the 7 d of treatment. Furthermore, variability in E2 was greatly diminished by elagolix treatment, and high plasma concentrations consistent with a midcycle estrogen surge were not observed in most subjects. In the 100-mg bid cohort, mean morning E2 levels for d 1–7 reached 17 ± 3 pg/ml, indicating a high degree of gonadal suppression. In the qd cohorts, mean E2 levels during the treatment period ranged from 34 ± 4 to 68 ± 46 pg/ml, although the higher end of this range is skewed by two subjects who escaped suppression (one each in the 100- and 200-mg qd groups). The escape subject in the 100-mg qd cohort (subject 51) entered with relatively high plasma E2 (83 pg/ml at 24 h before dosing) and, after a decrease upon initial administration of elagolix, continued to progress to even higher levels, reaching 342 pg/ml on the morning of d 7 (14 d after onset of menstruation). This was followed by an LH/FSH surge on d 8. The escape subject in the 200-mg qd cohort (subject 55) also showed high E2 (102 pg/ml) and FSH (12.1 mIU/ml) immediately before administration of elagolix. Despite initial decreases in LH, FSH, and E2, she also progressed to increasingly higher E2 concentrations followed by an LH/ FSH surge on d 8 (15 d after onset of menstruation). Plasma elagolix concentrations of both these subjects were consistent with other subjects receiving the same dosage.

Figure 3.

Individual serum E2 concentrations before and after elagolix administration. Data shown are mean ± range for each individual subject. Predose mean concentrations were calculated from the serum samples taken 24 h and immediately before initial administration of elagolix or placebo. Postdose concentrations are the mean of samples taken at 24-h intervals for 7 d after initial administration of elagolix or placebo (corresponding to d 1–7 in Fig. 2).

Discussion

These results provide the first demonstration of the suppression of the reproductive endocrine axis in premenopausal women by an oral GnRH antagonist. Oral administration of a second-generation nonpeptide GnRH antagonist, elagolix, to healthy premenopausal women results in its rapid absorption and immediate suppression of LH and FSH, followed by a somewhat delayed dose-related suppression of E2. Because of its relatively rapid clearance and short plasma residence time (2.5–4.1 h), pituitary suppression is maintained for only a portion of the day (25–400 mg), and baseline gonadotropin levels return by 24 h. However, suppression of E2 is more prolonged at doses of 50 mg and higher. Daily (50–200 mg) or twice-daily (100 mg) administration for 7 d during midfollicular phase results in a prevention of high midcycle E2 levels in most subjects. Overall, the compound was safe and well tolerated.

Previous reports of daily sc administration of the peptide GnRH antagonists cetrorelix and ganirelix to cycling premenopausal women showed results similar to those presented here, including a more pronounced suppression of circulating LH than FSH (16,24). This is also consistent with our previous report of another nonpeptide GnRH antagonist (NBI-42902) in postmenopausal women (18). The daily excursions to reduced gonadotropin levels and partial suppression of E2 observed with once-daily elagolix administration is in marked contrast to the continuous and profound suppression observed with peptide agonist depots (3).

As illustrated by the two escape subjects, the timing of onset of antagonist exposure during the menstrual cycle may contribute to the subsequent E2 response. The developing ovarian follicle varies in its tolerance to gonadotropin withdrawal, and the dominant follicle becomes increasingly controlled by local factors during late follicular phase and more resistant to short-term gonadotropin deprivation (25,26). This variability in follicular response to gonadotropin suppression may explain the two escape subjects (one in the 100-mg qd group and one in the 200-mg qd group) who showed progression to high E2 levels despite gonadotropin suppression by elagolix. Although ultrasound observation of follicular status was not made, both subjects started treatment with somewhat higher E2 levels than others in the cohort, consistent with a more advanced stage of follicular development. Thus, a more consistent response might be expected with onset of treatment earlier in the menstrual cycle.

Overall, these data indicate that oral administration of a nonpeptide GnRH antagonist can produce dose-related suppression of the reproductive endocrine axis. Studies in larger numbers of subjects are required to determine the reliability of gonadal suppression by this compound. In addition, at the once-daily doses studied, gonadotropins undergo excursions to reduced serum levels for a portion of the day, resulting in a partial suppression of ovarian estradiol secretion. The effect of this regimen on progression of the overall menstrual cycle is unknown and requires longer-term studies. The overall safety profile and endocrine responses in this first-in-human phase I study supports additional clinical studies to characterize these longer-term responses in larger groups of women. These studies, as well as exploratory studies of efficacy for pain relief in patients with endometriosis, have been completed and will be described in detail elsewhere.

Acknowledgments

We thank France La Pierre-Holme, Chris O'Brien, Josh Burke, the Clinical Operations, Data Management, Biostatistics, and Regulatory groups, and other members of the Neurocrine GnRH Development Team for their helpful advice, discussions, and nonclinical work that enabled this study. We thank Dr. Mark Allison and co-workers at MDS Pharma Services (Phoenix, AZ) for their assistance in the conduct of this study.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants 1-R43-HD38625-01 and 2-R44-HD38625-02.

Disclosure Summary: R.S.S., A.J.N., J.G., T.C., R.J., and H.P.B are, or were, employees of Neurocrine Biosciences and have, or had, equity interests in the company. S.C.C.Y. consulted for, and had equity interests in, Neurocrine Biosciences.

First Published Online November 25, 2008

Abbreviations: AE, Adverse event; AUC, area under the curve; bid, twice daily; BMI, body mass index; Cmax, maximum plasma concentration; E2, estradiol; HPG, hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal; qd, once daily; Tmax, time of maximum plasma concentration.

References

- Engel JB, Schally AV 2007 Drug insight: clinical use of agonists and antagonists of luteinizing-hormone-releasing hormone. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab 3:157–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huirne JA, Lambalk CB 2001 Gonadotropin-releasing-hormone-receptor antagonists. Lancet 358:1793–1803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn PM, Crowley Jr WF 1991 Gonadotropin-releasing hormone and its analogues. N Engl J Med 324:93–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemay A, Maheux R, Faure N, Jean C, Fazekas AT 1984 Reversible hypogonadism induced by a luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LH-RH) agonist (Buserelin) as a new therapeutic approach for endometriosis. Fertil Steril 41:863–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belchetz PE, Plant TM, Nakai Y, Keogh EJ, Knobil E 1978 Hypophysial responses to continuous and intermittent delivery of hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone. Science 202:631–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri RL 1992 Hormone treatment of endometriosis: the estrogen threshold hypothesis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 166:740–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surrey ES 1995 Steroidal and nonsteroidal “add-back” therapy: extending safety and efficacy of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists in the gynecologic patient. Fertil Steril 64:673–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedaiwy MA, Casper RF 2006 Treatment with leuprolide acetate and hormonal add-back for up to 10 years in stage IV endometriosis patients with chronic pelvic pain. Fertil Steril 86:220–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahara M, Matsuoka T, Yokoi T, Tasaka K, Kurachi H, Murata Y 2000 Treatment of endometriosis with a decreasing dosage of a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist (nafarelin): a pilot study with low-dose agonist therapy (“draw-back” therapy). Fertil Steril 73:799–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cetel NS, Rivier J, Vale W, Yen SS 1983 The dynamics of gonadotropin inhibition in women induced by an antagonistic analog of gonadotropin-releasing hormone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 57:62–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod D, Zinner N, Tomera K, Gleason D, Fotheringham N, Campion M, Garnick MB 2001 A phase 3, multicenter, open-label, randomized study of abarelix versus leuprolide acetate in men with prostate cancer. Urology 58:756–761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trachtenberg J, Gittleman M, Steidle C, Barzell W, Friedel W, Pessis D, Fotheringham N, Campion M, Garnick MB 2002 A phase 3, multicenter, open label, randomized study of abarelix versus leuprolide plus daily antiandrogen in men with prostate cancer. J Urol 167:1670–1674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felberbaum RE, Germer U, Ludwig M, Riethmuller-Winzen H, Heise S, Buttge I, Bauer O, Reissmann T, Engel J, Diedrich K 1998 Treatment of uterine fibroids with a slow-release formulation of the gonadotrophin releasing hormone antagonist cetrorelix. Hum Reprod 13:1660–1668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettel LM, Murphy AA, Morales AJ, Rivier J, Vale W, Yen SS 1993 Rapid regression of uterine leiomyomas in response to daily administration of gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist. Fertil Steril 60:642–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto VY, Monroe SE, Nelson LR, Downey D, Jaffe RB 1997 Dose-related suppression of serum luteinizing hormone in women by a potent new gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist (ganirelix) administered by intranasal spray. Fertil Steril 67:469–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson LR, Fujimoto VY, Jaffe RB, Monroe SE 1995 Suppression of follicular phase pituitary-gonadal function by a potent new gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist with reduced histamine-releasing properties (ganirelix). Fertil Steril 63:963–969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz SF, Zhu YF, Chen C, Struthers RS 2008 Non-peptide gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor antagonists. J Med Chem 51:3331–3348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struthers RS, Chen T, Campbell B, Jimenez R, Pan H, Yen SS, Bozigian HP 2006 Suppression of serum luteinizing hormone in postmenopausal women by an orally administered nonpeptide antagonist of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor (NBI-42902). J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:3903–3907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Wu D, Guo Z, Xie Q, Reinhart GJ, Madan A, Wen J, Chen T, Huang CQ, Chen M, Chen Y, Tucci FC, Rowbottom MW, Pontillo J, Zhu YF, Wade W, Saunders J, Bozigian H, Struthers RS 12 November 2008 Discovery of sodium R-(+)-4-{2-[5-(2-fluoro-3-methoxyphenyl)-3-(2-fluoro-6-[trifluoromethyl]benzyl)-4-methyl-2,6-dioxo-3,6-dihydro-2H-pyrimidin-1-yl]-1-phenylethylamino}butyrate (elagolix), a potent and orally available nonpeptide GnRH antagonist. J Med Chem 10.1021/jm8006454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struthers RS, Xie Q, Sullivan SK, Reinhart GJ, Kohout TA, Zhu YF, Chen C, Liu XJ, Ling N, Yang W, Maki RA, Bonneville AK, Chen TK, Bozigian HP 2007 Pharmacological characterization of a novel nonpeptide antagonist of the human gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor, NBI-42902. Endocrinology 148:857–867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFazio J, Meldrum DR, Laufer L, Vale W, Rivier J, Lu JK, Judd HL 1983 Induction of hot flashes in premenopausal women treated with a long-acting GnRH agonist. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 56:445–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen SS, Llerena O, Little B, Pearson OH 1968 Disappearance rates of endogenous luteinizing hormone and chorionic gonadotropin in man. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 28:1763–1767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreyko JL, Monroe SE, Marshall LA, Fluker MR, Nerenberg CA, Jaffe RB 1992 Concordant suppression of serum immunoreactive luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating hormone, α-subunit, bioactive LH, and testosterone in postmenopausal women by a potent gonadotropin releasing hormone antagonist (detirelix). J Clin Endocrinol Metab 74:399–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duijkers IJ, Klipping C, Willemsen WN, Krone D, Schneider E, Niebch G, Hermann R 1998 Single and multiple dose pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the gonadotrophin-releasing hormone antagonist Cetrorelix in healthy female volunteers. Hum Reprod 13:2392–2398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JE 1993 Gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonists: effects on the ovarian follicle and corpus luteum. Clin Obstet Gynecol 36:744–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JE, Bhatta N, Adams JM, Rivier JE, Vale WW, Crowley Jr WF 1991 Variable tolerance of the developing follicle and corpus luteum to gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist-induced gonadotropin withdrawal in the human. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 72:993–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]