Abstract

In addition to increasing insulin sensitivity and adipogenesis, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-γ agonists cause weight gain and hyperphagia. Given the central role of the brain in the control of energy homeostasis, we sought to determine whether PPARγ is expressed in key brain areas involved in metabolic regulation. Using immunohistochemistry, PPARγ distribution and its colocalization with neuron-specific protein markers were investigated in rat and mouse brain sections spanning the hypothalamus, the ventral tegmental area, and the nucleus tractus solitarius. In several brain areas, nuclear PPARγ immunoreactivity was detected in cells that costained for neuronal nuclei, a neuronal marker. In the hypothalamus, PPARγ immunoreactivity was observed in a majority of neurons in the arcuate (including both agouti related protein and α-MSH containing cells) and ventromedial hypothalamic nuclei and was also present in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus, the lateral hypothalamic area, and tyrosine hydroxylase-containing neurons in the ventral tegmental area but was not expressed in the nucleus tractus solitarius. To validate and extend these histochemical findings, we generated mice with neuron-specific PPARγ deletion using nestin cre-LoxP technology. Compared with littermate controls, neuron-specific PPARγ knockout mice exhibited dramatic reductions of both hypothalamic PPARγ mRNA levels and PPARγ immunoreactivity but showed no differences in food intake or body weight over a 4-wk study period. We conclude that: 1) PPARγ mRNA and protein are expressed in the hypothalamus, 2) neurons are the predominant source of PPARγ in the central nervous system, although it is likely expressed by nonneuronal cell types as well, and 3) arcuate nucleus neurons that control energy homeostasis and glucose metabolism are among those in which PPARγ is expressed.

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ, a key regulator of adipogenesis and insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues, is also expressed in neurons involved in body weight control.

The nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-γ is a ligand-activated transcription factor that promotes adipogenesis and insulin sensitivity (1,2). PPARγ is expressed in several tissues and cell types including white and brown adipocytes, macrophages, skeletal muscle, liver, pancreatic β-cells, and other tissues (3,4,5). The thiazolidinedione (TZD) class of synthetic PPARγ agonists is used widely in diabetes treatment to increase insulin sensitivity, and although mechanisms underlying these TZD effects are complex and incompletely understood, induction of genes involved in glucose and lipid metabolism in macrophages, muscle, and adipose tissue is thought to play a role (5,6). Countering the impressive metabolic benefits of TZDs in patients with type 2 diabetes are weight gain and fat accumulation (7). Although effects on adipocytes may play a role (e.g. PPARγ mediated stimulation of adipocyte differentiation and lipid storage), TZDs also induce hyperphagia in rodent models, which contributes to the weight gain induced by these drugs (8,9,10).

These observations, combined with recent evidence of effects of TZDs on autonomic function (11) raise the possibility that in addition to its actions in peripheral tissues, PPARγ plays a role in neuronal systems governing energy balance and insulin sensitivity. This hypothesis is at odds with a recent paper (12) reporting undetectable levels of PPARγ mRNA in mouse hypothalamus, whereas an earlier paper reported limited evidence of PPARγ immunoreactivity in rat hypothalamus (13). Whether PPARγ is expressed in brain areas important in the control of energy balance and insulin action therefore remains controversial.

The control of energy balance involves central nervous system integration of both satiety signals, which are released after a meal and signal through afferent fibers of the vagus nerve to the nucleus tractus solitarius in the hindbrain, and adiposity signals (e.g. leptin and insulin) acting in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus (ARC) (14) among many other brain areas. One key subset of ARC neurons produces the orexigenic molecules neuropeptide Y (NPY) and agouti-related peptide (AgRP) (15,16), whereas another produces anorexigenic peptides cleaved from the proopiomelanocortin (POMC) precursor (17). In addition to participating in the control of food intake, these ARC neurons transduce circulating hormonal and nutrient-related inputs into changes of autonomic function and insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues (18). Adiposity-related hormones such as leptin also act on dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) of the midbrain, ultimately influencing the reward value associated with food consumption (19). Other brain areas involved in the control of energy balance and autonomic function include the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN) and the lateral hypothalamic area (LHA) (14). Here we sought to resolve the existing controversy over whether PPARγ is expressed in key brain areas and neurons that regulate energy homeostasis.

Materials and Methods

Immunohistochemistry

Adult male Wistar rats (Charles River, Wilmington, MA) were used for histochemical studies. Tissue preparation for staining was as previously described (20). Briefly, coronal sections were taken from paraffin-embedded brain tissue and stained separately with five different antibodies raised against PPARγ: a rabbit polyclonal (no. 07-466; Chemicon, Temecula, CA), a rabbit polyclonal (no. ab19481; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), a rabbit polyclonal (catalog no. GTX19481; Genetex, San Antonio, TX), a rabbit polyclonal (no. sc-7196; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), and a mouse monoclonal (no. sc-7273; Santa Cruz). All PPARγ antibodies were diluted to a final concentration of 1:500. Detection of primary antibody binding was accomplished through a secondary Alexa 488-labeled antirabbit antisera diluted 1:800 from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA) or through a biotin/strepavidin/horseradish peroxidase amplification system (ABC Elite kit; Vector Laboratories) with diaminobenzidine (Vector Laboratories).

For colocalization studies, primary antibody incubations were performed using a cocktail of anti-PPARγ and one of the following antibodies at the indicated dilutions: α-MSH, 1:10,000 (Chemicon); AgRP, 1:2000 (U.S. Biological, Swampscott, MA); neuronal nuclei (NeuN), 1:500 (Chemicon); melanin-concentrating hormone, 1:10,000 (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Phoenix, AZ); or TH, 1:1000 (Chemicon). Slides were incubated with a combination of Alexa 488-labeled antirabbit, Alexa Fluor 594 donkey antisheep, or Alexa Fluor 594 donkey antigoat secondary antibodies. All fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies were from Vector Laboratories and diluted 1:800. After washing, slides were incubated with 4′,6′-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) to identify cell nuclei. Control sections were stained by substituting normal rabbit serum for primary antibody.

Generation and characterization of conditional PPARγ-deficient mice

Neural deletion of PPARγ was achieved by crossing mice with a floxed PPARγ allele [TgH(PPARg lox)1Mgn, TgH(PPARγ del)2Mgn] as previously described (21) (a generous gift from M. A. Magnuson; Center for Stem Cell Biology, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, TN 37232-0225) with Nestin-Cre mice [B6.Cg-Tg(Nes-cre)1Kln/J], purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). All mice were fully backcrossed to a C57/BL6 genetic background.

RT-PCR analysis of gene deletion

RNA was extracted from whole brain and hypothalamus as well as liver and adipose tissue, using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and subjected to quantitative RT-PCR as previously described (22) to quantify PPARγ mRNA levels. PPARγ primer sequences for quantitative PCR were: CCACTCGCATTCCTTTGACATC (forward) and TTGATCGCACTTTGGTATTCTTGG (reverse).

Immunostaining

Immunofluorescence on NesKO and NesWT mice was performed using the Santa Cruz (catalog no. sc-7196) antibody as described above.

Food intake and body weight measurements

Male NesKO and NesWT littermate mice (aged 40 d, n = 5/group) were housed singly on a 12-h dark, 12-h light cycle and provided ad libitum access to standard laboratory chow (PMI Nutrition International Inc., Brentwood, MO). Food intake and body weight were measured daily over a 4-wk period.

Statistical analysis

Variation in PPARγ mRNA levels in NesWT, NesHet, and NesKO mice was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc analysis. Variation in food intake and body weight between NesWT and NesKO mice was determined by Student’s t test. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Detection of PPARγ in brain regions involved in regulation of energy homeostasis, insulin sensitivity, and autonomic function

The pattern of immunoreactivity detected after staining coronal rat brain sections was similar when stained separately with each of five different commercially available antibodies recognizing PPARγ (Fig. 1 and data not shown). PPARγ immunoreactivity was detected in the majority of cells in the ventromedial nucleus (VMN) and ARC and was detected in a smaller percentage of cells in the LHA and PVN (Fig. 1, A–C). PPARγ immunoreactivity was also detected in the VTA (Fig 1D) but not nucleus tractus solitarius (data not shown). At the single-cell level, PPARγ immunoreactivity was localized primarily to the cell nucleus, as revealed by DAPI costaining (Fig. 1E). Colocalization of PPARγ in neurons with immunoreactivity for the neuronal marker NeuN was ubiquitous in the mediobasal hypothalamus (Fig. 1F). In the ARC, for example, nearly all PPARγ-positive cells expressed NeuN, whereas approximately 70% of PPARγ-positive cells in the VMN expressed NeuN (Fig. 1F). Although PPARγ was also occasionally present in NeuN-positive cells elsewhere, such colocalization was absent in thalamus and most other brain areas (Fig. 1F and data not shown). Control sections stained either with normal rabbit serum or without primary or secondary antibody showed no detectable staining (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Expression of PPARγ in rat brain areas involved in the control of energy homeostasis and insulin sensitivity. Hypothalamic distribution of PPARγ immunostaining in the hypothalamus using the Upstate antibody (A), including the ARC and VMN (B), PVN (C), LHA (A), and VTA (D). Colocalization of PPARγ immunoreactivity (green) with DAPI labeling (blue) was performed to visualize PPARγ nuclear distribution (blue-green) (E). Costaining of PPARγ (green) with NeuN (red) (F) shows that in the ARC and VMN, most neurons express PPARγ, whereas in the thalamus, PPARγ is absent from most neurons. 3v, Third ventricle; MBH, mediobasal hypothalamus.

To determine whether hypothalamic PPARγ gene expression is subject to regulation by changes of energy balance, we subjected normal mice and rats to fasting for periods of up to 48 h. Unlike what has been reported in adipose tissue (23), we observed no effect of fasting on hypothalamic PPARγ mRNA levels as measured by quantitative PCR in either species (data not shown).

Detection of PPARγ immunoreactivity in specific neuronal subsets involved in metabolic regulation

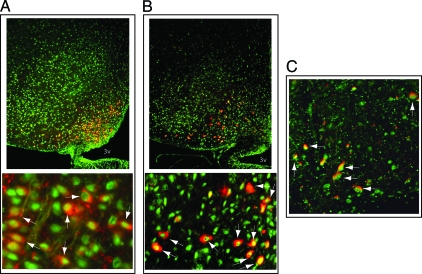

To identify ARC neuronal subsets that express PPARγ, coronal rat brain sections were coimmunostained to detect PPARγ and either AgRP or αMSH (a melanocortin peptide cleaved from POMC). As shown in Fig. 2, A and B, whereas AgRP and αMSH immunoreactivity were detected in cell cytoplasm, as expected, PPARγ immunoreactivity was present in the nucleus of most of these two subsets of neurons. In the VTA, colocalization of PPARγ and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH; a dopaminergic neuronal marker) was commonplace (Fig. 2C). By comparison, although PPARγ immunoreactivity was detected in the LHA, colocalization with melanin-concentrating hormone was not detected (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Expression of PPARγ in distinct neuronal subsets. Detection of PPARγ (green) in ARC neurons containing either (A) AgRP (red) or (B) αMSH (red) (bottom panels taken at higher magnification), as indicated by arrows using the Upstate antibody. PPARγ (green) was also colocalized with TH (red) in VTA neurons (C). 3v, Third ventricle.

PPARγ mRNA and protein levels in neuron-specific PPARγ knockout mice

To definitively ascertain whether PPARγ mRNA and protein are expressed in neurons, and investigate whether PPARγ is also expressed in nonneuronal cell types in the brain, we generated mice in which the enzyme cre recombinase is expressed specifically in neural precursor cells under the control of the nestin promoter-enhancer (crenes). These mice were crossed with PPARγflox/flox mice to generate three genotypes of mice: crenesPPARγ flox/flox (NesKO), crenesPPARγflox/+ (NesHet), and crenesPPARγ+/+ (NesWT) mice. Genomic DNA extracted from whole brain was analyzed by PCR to verify deletion of PPARγ. A 551-bp band corresponding to the deleted PPARγ allele (21) appeared in the PCR analysis of brain DNA from NesKO mice but not in the DNA from NesWT (Fig. 3A). As expected, PPARγ mRNA levels were much lower in brain than either liver or adipose tissue of NesWT mice (Fig 3B). Compared with NesWT mice, PPARγ mRNA levels were reduced by more than 90% in whole brain (Fig. 3B) [main effect of genotype: F(2,10) = 9.85, P < 0.005] and by 80% in the hypothalamus of NesKO mice (Fig. 3C) [main effect of genotype: F(2,10) = 13.01, P < 0.01]. Whereas NesHet mice tended to display intermediate PPARγ mRNA expression levels, values were not significantly different from either NesWT or NesKO mice after Tukey post hoc analysis. As expected, PPARγ mRNA levels in peripheral tissues did not differ by genotype (Fig. 3C). PPARγ immunostaining was also dramatically reduced in the hypothalamus of NesKO mice compared with NesWT mice (Fig. 3D). Differences of average body weight and daily food intake were not detected between NesKO and NesWT mice fed a chow diet over a 4-wk study period (Fig. 3E). Together, these results validate both the Cre-Loxp strategy used to delete PPARγ in neurons of NesKO mice and the technique we used to detect PPARγ immunoreactivity. Furthermore, they establish that in mouse brain, PPARγ mRNA and protein are expressed predominantly in neurons, although expression is also present in nonneuronal cells.

Figure 3.

Generation, validation, and body weight of neuron-specific PPARγ knockout mice. A, PCR analysis of genomic DNA from brain revealing the presence of floxed, wild-type (WT), deleted, and cre alleles. B, Expression of PPARγ mRNA in whole brain, liver (Liv), and white adipose tissue (WAT) and in the hypothalamus of NesWT, NesKO, and NesHet mice measured by quantitative RT-PCR (C). D, PPARγ immunoreactivity in coronal hypothalamic sections sampled from NesWT and NesKO mice using the sc-7196 antibody. E, Average body weight and daily food intake of NesWT and NesKO mice over a 4-wk study period. Values are expressed as ± sem. *, P < 0.01 for NesWT vs. NesKO by one-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc analysis.

Discussion

In addition to affecting adipocyte differentiation, insulin sensitivity and other metabolic parameters, effects of TZD drugs on food intake (8,9,10) and sympathetic outflow (11) suggest a central site of action. Although PPARγ immunoreactivity has been reported in mammalian brain (13), a recently reported survey of nuclear receptors in mouse brain concluded that the PPARγ gene is expressed at undetectable levels in most brain areas, including hypothalamus (12). Thus, controversy surrounds the general question of whether PPARγ is present in hypothalamus and, more specifically, whether it is present in hypothalamic areas and neuronal subsets involved in the control of energy homeostasis and glucose metabolism. Here we provide evidence that PPARγ is expressed in brain, including hypothalamic neurons controlling energy balance, autonomic function and glucose metabolism. Among these are NPY/Agrp and POMC neurons in the ARC, a majority of neurons in VMN, and more occasional cells in the PVN and LHA. We also identified PPARγ expression in dopaminergic neurons of the VTA, a brain area that helps to establish the rewarding properties of food and other stimuli (19).

To definitively establish whether PPARγ is expressed in neurons and estimate its abundance in neurons relative to other cell types in the brain, we generated neuron-specific PPARγ knockout mice. Our finding of markedly reduced PPARγ mRNA and protein levels in both whole brain and hypothalamus of these animals establishes neurons as the primary source of PPARγ in mouse brain.

As in adipocytes (1), PPARγ staining was detected in the cell nucleus, consistent with its role as a nuclear receptor, whereas neuropeptide immunoreactivity, as expected, was observed largely in neuronal cytoplasm. Within the hypothalamus, the majority of PPARγ immunopositive cells were neurons, based on colocalization with the neuronal marker NeuN. Because PPARγ transcriptional activity requires dimerization with the retinoid X receptor (RXR) (24), the hypothesis that PPARγ regulates neuronal gene transcription presumes that PPARγ and RXR are expressed in the same cells. Although this hypothesis is as yet untested, RXR isoforms are widely distributed in the brain, including the ARC and other hypothalamic areas (12).

Among neuronal subsets with nuclear PPARγ immunoreactivity are ARC NPY/AgRP and POMC cells, both of which play fundamental roles to sense humoral signals regarding nutritional state (e.g. leptin, insulin, ghrelin, glucose, and free fatty acids) and transduce them into adaptive changes of food intake, energy expenditure, and insulin sensitivity (25). In light of growing evidence that PPARγ adjusts cellular substrate metabolism and energy storage in response to changes of nutrient availability in peripheral tissues (23), our findings raise the possibility of a comparable role for PPARγ in the nutrient-sensing function of key neurons.

As a first step to investigate whether neuronal PPARγ signaling is required for normal control of energy balance, we compared mean food intake and body weight of male NesKO mice and their male NesWT littermates fed standard chow over a 4-wk study period. Because this preliminary study revealed no differences between genotypes, neuronal PPARγ signaling does not appear to be required for normal body weight regulation under these relatively narrowly defined conditions (e.g. relatively young male animals fed standard chow). More definitive studies of the effects of neuronal PPARγ deletion on energy balance and body weight under a variety of conditions (e.g. during high fat feeding or in response to TZDs) are currently underway.

In conclusion, we report that PPARγ is expressed in key brain areas and specific neuronal subsets involved in the control of energy balance, insulin sensitivity and autonomic function.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Loan Nguyen and Miles Matsen for their expert technical assistance.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK52989 (to M.W.S.), DK68340, and NS32273; a mentor-based fellowship from the American Diabetes Association; the Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center Grant P30 DK-17047; and Clinical Nutrition Research Unit of the University of Washington Grant P30 DK035816. Additionally, this material is the result of work supported with resources of the Tennessee Valley Healthcare System (Nashville, TN) and by Grants DK064857 (to K.D.N.) and DK069927 (to K.D.N.), Vanderbilt Diabetes Research and Training Center Grant DK20593; and Vanderbilt Mouse Metabolic Phenotyping Center Grant DK59637.

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online October 9, 2008

Abbreviations: ARC, Arcuate nucleus; AgRP, agouti-related peptide; DAPI, 4′,6′-diamino-2-phenylindole; LHA, lateral hypothalamic area; NeuN, neuronal nuclei; NPY, neuropeptide Y; POMC, proopiomelanocortin; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor; PVN, paraventricular nucleus; RXR, retinoid X receptor; TH, tyrosine hydroxylase; TZD, thiazolidinedione; VMN, ventromedial nucleus; VTA, ventral tegmental area.

References

- Rosen ED, Sarraf P, Troy AE, Bradwin G, Moore K, Milstone DS, Spiegelman BM, Mortensen RM 1999 PPARγ is required for the differentiation of adipose tissue in vivo and in vitro. Mol Cell 4:611–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegelman BM 1998 PPAR-γ: adipogenic regulator and thiazolidinedione receptor. Diabetes 47:507–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escher P, Braissant O, Basu-Modak S, Michalik L, Wahli W, Desvergne B 2001 Rat PPARs: quantitative analysis in adult rat tissues and regulation in fasting and refeeding. Endocrinology 142:4195–4202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen ED, Kulkarni RN, Sarraf P, Ozcan U, Okada T, Hsu CH, Eisenman D, Magnuson MA, Gonzalez FJ, Kahn CR, Spiegelman BM 2003 Targeted elimination of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ in β cells leads to abnormalities in islet mass without compromising glucose homeostasis. Mol Cell Biol 23:7222–7229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hevener AL, Olefsky JM, Reichart D, Nguyen MT, Bandyopadyhay G, Leung HY, Watt MJ, Benner C, Febbraio MA, Nguyen AK, Folian B, Subramaniam S, Gonzalez FJ, Glass CK, Ricote M 2007 Macrophage PPARγ is required for normal skeletal muscle and hepatic insulin sensitivity and full antidiabetic effects of thiazolidinediones. J Clin Invest 117:1658–1669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard F, Auwerx J 2002 PPARγ and glucose homeostasis. Annu Rev Nutr 22:167–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asnani S, Richard BC, Desouza C, Fonseca V 2003 Is weight loss possible in patients treated with thiazolidinediones? Experience with a low-calorie diet. Curr Med Res Opin 19:609–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickavance LC, Buckingham RE, Wilding JP 2001 Insulin-sensitizing action of rosiglitazone is enhanced by preventing hyperphagia. Diabetes Obes Metab 3:171–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaput E, Saladin R, Silvestre M, Edgar AD 2000 Fenofibrate and rosiglitazone lower serum triglycerides with opposing effects on body weight. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 271:445–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Dryden S, Frankish HM, Bing C, Pickavance L, Hopkins D, Buckingham R, Williams G 1997 Increased feeding in fatty Zucker rats by the thiazolidinedione BRL 49653 (rosiglitazone) and the possible involvement of leptin and hypothalamic neuropeptide Y. Br J Pharmacol 122:1405–1410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festuccia WT, Oztezcan S, Laplante M, Berthiaume M, Michel C, Dohgu S, Denis RG, Brito MN, Brito NA, Miller DS, Banks WA, Bartness TJ, Richard D, Deshaies Y 2008 PPARγ-mediated positive energy balance in the rat is associated with reduced sympathetic drive to adipose tissues and thyroid status. Endocrinology 149:2121–2130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gofflot F, Chartoire N, Vasseur L, Heikkinen S, Dembele D, Le Merrer J, Auwerx J 2007 Systematic gene expression mapping clusters nuclear receptors according to their function in the brain. Cell 131:405–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno S, Farioli-Vecchioli S, Ceru MP 2004 Immunolocalization of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and retinoid X receptors in the adult rat CNS. Neuroscience 123:131–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton GJ, Cummings DE, Baskin DG, Barsh GS, Schwartz MW 2006 Central nervous system control of food intake and body weight. Nature 443:289–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalra SP, Horvath TL 1998 Neuroendocrine interactions between galanin, opioids, and neuropeptide Y in the control of reproduction and appetite. Ann NY Acad Sci 863:236–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ollmann MM, Wilson BD, Yang YK, Kerns JA, Chen Y, Gantz I, Barsh GS 1997 Antagonism of central melanocortin receptors in vitro and in vivo by agouti-related protein. Science 278:135–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cone RD 1999 The central melanocortin system and energy homeostasis. Trends Endocrinol Metab 10:211–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konner AC, Janoschek R, Plum L, Jordan SD, Rother E, Ma X, Xu C, Enriori P, Hampel B, Barsh GS, Kahn CR, Cowley MA, Ashcroft FM, Bruning JC 2007 Insulin action in AgRP-expressing neurons is required for suppression of hepatic glucose production. Cell Metab 5:438–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figlewicz DP, MacDonald Naleid A, Sipols AJ 2007 Modulation of food reward by adiposity signals. Physiol Behav 91:473–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardini AW, Nguyen HT, Figlewicz DP, Baskin DG, Williams DL, Kim F, Schwartz MW 2006 Distribution of insulin receptor substrate-2 in brain areas involved in energy homeostasis. Brain Res 1112:169–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JR, Shelton KD, Guan Y, Breyer MD, Magnuson MA 2002 Generation and functional confirmation of a conditional null PPARγ allele in mice. Genesis 32:134–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton GJ, Blevins JE, Williams DL, Niswender KD, Gelling RW, Rhodes CJ, Baskin DG, Schwartz MW 2005 Leptin action in the forebrain regulates the hindbrain response to satiety signals. J Clin Invest 115:703–710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal-Puig A, Jimenez-Linan M, Lowell BB, Hamann A, Hu E, Spiegelman B, Flier JS, Moller DE 1996 Regulation of PPARγ gene expression by nutrition and obesity in rodents. J Clin Invest 97:2553–2561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman AI, Mangelsdorf DJ 2005 Retinoid X receptor heterodimers in the metabolic syndrome. N Engl J Med 353:604–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MW, Porte Jr D 2005 Diabetes, obesity, and the brain. Science 307:375–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]