Abstract

This review summarizes and examines the evidence from experiments using animal models to determine the effect of exercise training on endothelium-dependent dilation in the arterial circulation. The response of the endothelium to exercise training is complex and depends on a number of factors that include: the duration of the training program, the size of the artery/arteriole, the anatomical location of the artery/arteriole, and the health of the individual. In general, evidence supports the notion that exercise training causes greater increases in endothelium-dependent dilation in various disease states than in healthy individuals. There is little evidence for a generalized effect of training on arterial endothelium in all regions of the body. Available results indicate that training duration, artery size, and anatomical location interact in ways not fully understood at this time to determine whether and to what extent endothelium-dependent dilation will be enhanced by exercise training.

Keywords: endothelium, vasodilation, skeletal muscle, arteries, blood flow

Introduction: Blood flow adaptations to training

Exercise training elicits a number of physiological adaptations, including increased maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max), increased cardiac output, and increased maximal oxygen extraction (26). Furthermore, training produces an increase in maximal skeletal muscle blood flow capacity in dogs, rats, and humans (26), increases skeletal muscle blood flow during high-intensity exercise in dogs (39), rats (26), and humans (26), but does not appear to alter total skeletal muscle blood flow under resting conditions or during submaximal exercise at similar absolute exercise intensities (26). However, despite similar total blood flow to skeletal muscle, the distribution of blood flow between different muscles and within specific regions of muscle during moderate intensity exercise is altered by training (1). Specifically, blood flow to regions composed primarily of highly oxidative muscle fibers is increased while blood flow to primarily glycolytic regions of muscle is reduced and flow to non-locomotory muscle is not altered (39). Thus exercise training causes blood flow (and oxygen delivery) to be increased to the fibers whose ATP generation is most dependent on oxygen and decreased to fibers that are less dependent on oxygen availability for ATP production.

One mechanism by which exercise training may alter blood flow is by changing either endothelial or smooth muscle control of vascular resistance. Furchgott and Zawadski (10) discovered more than two decades ago that the endothelium is an important regulator of vascular tone, and there has been much interest in the subject in years since. The endothelium is located in a strategic position, between the blood and the vascular smooth muscle, and it responds to changes in shear stress and a host of chemical signals by producing factors (nitric oxide (NO), prostacyclin (PGI2), and/or one or more endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors (EDHF)) that act on the vascular smooth muscle to regulate vascular tone (26). Exercise training-induced alterations in any of these signaling pathways would lead to changes in endothelial control of blood flow.

Recently, Moyna and Thompson (37) concluded that cross-sectional and longitudinal studies in human subjects indicate that exercise training has little effect on endothelial function in conduit arteries of normal subjects but document improved endothelial function with exercise training in subjects who had blunted endothelial function prior to training. These conclusions, combined with our experience with similar studies in animals, stimulated the question: does current literature indicate a similar interactive effect of endothelial health and exercise in animals such that exercise training has a greater effect on endothelial function in conditions of abnormal endothelial function? Therefore, this review has three purposes: 1) To evaluate the hypothesis that exercise training enhances endothelial function in normal health and preserves or restores endothelial function in animal models of disease with endothelial dysfunction., 2) Compare the effects of short (1–4 weeks) term training vs. long term training on endothelial function in animal models, and 3) Evaluate the hypothesis that exercise training has a generalized, systemic effect on endothelial health in animal models.

Endothelial adaptations to training in normal (young) healthy animals

Conduit Arteries

The most common measure of endothelial function/health is a measurement of endothelium-dependent dilation/relaxation (EDD). In 1993, Delp et al. reported that relaxation to acetylcholine (ACh), an endothelium-dependent dilator, was enhanced by 12 weeks of exercise training (8). L-NAME, an arginine analog that competitively inhibits NO production, partially inhibited EDD in aortic rings from both sedentary and trained rats, but the inhibition was greater in rings from trained rats such that L-NAME abolished the difference between groups. Furthermore, aortic contractions caused by norepinephrine (NE) were decreased by training, but contraction was similar when α2 adrenergic blockade was present in both sets of vessels, indicating that training caused an increase in endothelial cell α2 mediated dilation. Training-induced alterations appeared to be specific to the aortic endothelium since endothelium-independent dilations (to sodium nitroprusside) were not altered by training.

Examination of the time-course of training-induced increases in aortic EDD revealed no change following a single exercise bout or after training durations of less than four weeks, but aortic EDD was increased following training programs of 4 weeks and 10 weeks (7). Subsequent studies using 8–10 weeks of training in rats (5,6,61) confirmed these results (see Table 1). Also, 16–19 weeks of training in pigs (45) produce changes in aortic endothelial gene expression consistent with enhanced EDD following long term training.

Table 1.

Effect of exercise training on endothelial function in normal, healthy animals: Aorta

| Reference | Species | Method | Vessels | EDD | EID | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen et al., 1996 (5) | WKY Rat | In vitro rings | Aorta | ↑ due to BK-Ca channels | ↑ blocked by L-NAME, TTX, and CTX 8 wk training |

|

| Chu et al., 2000 (6) | Wistar Rat | In vitro rings | Aorta | ↑ Ca influx into endo cells | 10 wk training | |

| Delp & Laughlin, 1997 (7) | Rat | In vitro rings | Aorta | ↑ in 4 & 10 wk, but not shorter protocols | ↑ abolished by L-NAME eNOS also up at 4 & 10 weeks |

|

| Delp et al., 1993 (8) | Rat | In vitro rings | Aorta | ↑ ACh; ↑ blocked by L-NAME | No change | 10–12 wk training |

| Rush et al., 2003 (45) | Pig | Molecular | Aorta | ↑ SOD-1 and Cu/Zn SOD | 16–19 wk training; Overall ↓ in oxidative stress and ERK activation | |

| Yang et al., 2002 (61) | Rat | Molecular | Aorta | ↑ iNOS and eNOS ↓ PE constriction |

10 wk training ↓ PE constriction reversed w/aminoguanidine |

TTX: tetrodotoxin, CTX: charybdotoxin, eNOS: endothelial nitric oxide synthase, iNOS: inducible NOS; SOD: superoxide dismutase.

The effect of exercise training on EDD in other conduit arteries differs from the aorta (Table 2). Results of a study examining porcine femoral and brachial arteries indicate that short term training (7 days) elicits enhanced EDD in the brachial, but not the femoral artery (35). Relaxations to sodium nitroprusside (endothelium-independent) were not altered. In contrast, long term training of pigs (16–20 wks) had no effect on EDD in either the brachial or femoral arteries of male pigs (29). In female pigs, femoral artery responses were not altered with short or long term training (29,34) but EDD was improved in brachial arteries of female pigs trained for 20 weeks (29). Thus, results do not consistently reveal enhanced EDD of arteries providing blood to limb muscles of trained pigs. Indeed, in normal male and female pigs, exercise training has only moderate effects on EDD in conduit arteries, as the amount of increase in EDD is modest in normal female pigs even when statistically significantly increased. Finally, EDD in porcine renal, mesenteric, and hepatic arteries (34), and of porcine pulmonary arteries (20) is not altered by 16–20 weeks of exercise training. These data indicate that long term exercise training does not increase EDD throughout the porcine arterial tree, i.e. training does not have a generalized effect on endothelial function in conduit arteries of non-muscular vascular beds.

Table 2.

Effect of exercise training on endothelial function in normal, healthy animals: Conduit arteries

| Reference | Species | Method | Vessels | EDD | EID | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHORT-TERM TRAINING | ||||||

| Johnson et al. JAP 90:1102, 2001 (22) | Pig | In vitro rings | Pulmonary artery | ↑ EDD and ↑ eNOS ↔ SOD-1 |

No change | 7 day training |

| Laughlin et al., 2003 (28) | Pig | In vitro rings | Coronary conduit arteries | ↑, but no ↑ in eNOS | 7 day training Aorta eNOS was ↑ ed |

|

| McAllister & Laughlin, 1997 (35) | Pig | In vitro rings | Femoral & brachial | ↑ in brachial, not fem Not NO or PG’s | No change | 7 day training |

| Sessa et al., 1994 (47) | Dog | Nitrite & molecular | Coronary arteries | ↑ nitrite production & ↑ eNOS mRNA | 10 day training | |

| Wang et al., 1993 (54) | Dog | In vivo flow probe | Coronary arteries | ↑ ACh dilation abolished by L-NNA | 7 day training | |

| LONG-TERM TRAINING | ||||||

| Johnson & Laughlin, 2000 (20) | Pig | In vitro rings | Pulmonary artery | ↔ ACh | No change | 16 wk training |

| Kemi et al., 2004 (23) | Rat | In vitro rings | Carotid | ↑ ACh | No change | 10 wk training; ↑ EDD completely lost after 2 weeks detraining |

| Laughlin et al., 2001 (29) | Pig | In vitro rings | Femoral & | Male: ↔ Female: ↔ |

No change in either gender | Were other gender specific effects 16–20 wk training |

| Brachial | Male: ↔ Female: ↑ |

No change in either gender | ||||

| Laughlin et al., 2001 (27) | Pig | Molecular | Coronary | ↑ eNOS in arterioles and small arteries | 16–20 wk training No change in eNOS in conduit arteries |

|

| McAllister et al., 1996 (34) | Pig | In vitro rings | Fem., brach., renal, mes., hepatic arteries | ↔ ACh | No change | 16–20 wk training |

| Oltman et al., 1995 (42) | Pig | In vitro rings | Coronary | No change | No change | 13–20 wk training |

EDD: endothelium-dependent dilation. See Table 1 for other abbreviations.

Skeletal Muscle Resistance Vessels

Short term training consistently causes endothelial adaptations in skeletal muscle resistance vessels (Table 3). Three to four weeks of daily exercise in rats increased EDD of gracilis muscle arterioles to acetylcholine and L-arginine (51) and to increased levels of perfusate flow (24). The augmented response to flow was partially abolished by blocking eNOS or cyclooxygenase, indicating that both NO and PGI2 pathways were enhanced (24). Flow-induced dilation of arterioles from the plantaris muscle was also increased in rats by 3–4 weeks of exercise (49). Although, Massett et al. found that EDD in response to increased osmolarity in rat gracilis arterioles was not altered by four weeks of exercise training (32), available evidence generally indicates that short-term exercise training increases EDD in resistance arteries of skeletal muscle.

Table 3.

Effect of exercise training on endothelial function in normal, healthy animals: Resistance arteries and arterioles

| Reference | Species | Method | Vessels | EDD | EID | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHORT-TERM TRAINING | ||||||

| Koller et al., 1995 (24) | Rat | In vitro cannulated | Gracilis arterioles | ↑ Flow dilation; due to ↑ NO & ↑ PGI2 | 3 wk training | |

| Laughlin et al., 2003 (28) | Pig | In vitro cannulated | Coronary arterioles | no change | 7 day training | |

| Massett et al., 2000 (32) | Rat | In vitro cannulated | Gracilis arterioles | ↔ dilation to ↑ osmolarity | 4 wk training protocol; dilation to osmolarity was KOed by endothelium removal | |

| Sun et al., 1994 (51) | Rat | In vitro cannulated | Gracilis arterioles | ↑ ACh, L-Arg | No change or ↓ | 4 wk training |

| Sun et al., 1998 (49) | Rat | In vitro cannulated | Mesenteric arterioles | ↔ Flow dilation | 3–4 wks training | |

| Plantaris arterioles | ↑ Flow dilation | |||||

| LONG-TERM TRAINING | ||||||

| Jasperse & Laughlin, 1999 (17) | Rat | In vitro cannulated | Soleus feed artery | ↔ ACh ↔ Flow dilation |

No change | 12 wk training |

| Lash & Bohlen, 1997 (25) | Rat | In situ microscopy | Spinotrapezius arterioles | ↔ ACh @ 8 wks; ↑ ACh in 1A & 2A @ 16 wks | ↑ SNP in FA @ 8 wks; ↑ in FA & 1A @ 16 wks | 8 & 16 wk training ↑ functional dilation at 8 wks, but mostly gone at 16 wks |

| Laughlin et al., 2004 (30) | Rat | In situ, in vitro, and molecular | 1-3A from red G and white G | ↑ in WG 2A, ↔ in WG 3A ↔ in RG 2A | No change | Interval sprint training for 10 weeks ↑ eNOS in conduits, GFA, WG4A, RG5A ↑ SOD-1 in popliteal, WG4A |

| McAllister et al., 2005 (33) | Rat | In situ, in vitro, and molecular | Many orders of arterioles from RG and WG | ↑ in some orders from RG; | ↑ in some orders from RG | 8–12 wk training ↑ eNOS in some orders from RG |

| Muller et al., 1994 (38) | Pig | In vitro cannulated | Coronary arterioles | ↑ BK; ↑ abolished by L-NMMA | No change | 16–20 wks training |

G: gastrocnemius, R: red, W: white, FA: feed artery, SOD: superoxide dismutase; KO: knock out.

There have been only a few studies of the effects of long-term training on EDD in skeletal muscle resistance arteries (Table 3), and results are variable. For example, Lash and Bohlen (25) reported that 8 weeks of exercise training did not alter EDD in spinotrapezius muscle arteries of rats, but 16 weeks of training did elicit an increased dilation to ACh in first and second order arterioles from this muscle. However, they also reported an increased dilation to sodium nitroprusside in first order arterioles and feed arteries after 16 weeks, so it is difficult to know whether the increased dilation in first order branches was due to adaptations in the smooth muscle alone or if the endothelium also contributed. It should be noted that functional dilation (response to electrical stimulation) was increased at 8 weeks, but this augmentation was almost gone by 16 weeks of training. Thus the time course of adaptations in EDD was dissociated from the time course of adaptations in functional dilation. Although the oxidative capacity of the spinotrapezius (as measured by citrate synthase activity) was increased a small amount in this study, it should be noted that the spinotrapezius is not a primary locomotory muscle.

The soleus muscle is used extensively in posture maintenance and locomotion, and is a muscle whose blood flow is increased during exercise (1). Exercise training for 12 wks did not alter EDD in rat soleus muscle feed arteries (17). This observation may be the result of the fact that the soleus muscle is used constantly in the maintenance of posture in the standing rat. Due to this high level of recruitment, soleus muscle metabolic activity is high even in sedentary rats, as is the blood flow and shear stress through the soleus muscle feed arteries (16). Consistent with this interpretation are results of a study in which decreasing metabolic activity and blood flow of the soleus muscle via hindlimb unweighting produced a reduction in EDD (18). The conclusion of studies altering soleus activity with chronic training and chronic inactivity indicate that EDD in soleus feed arteries can be reduced, but not enhanced, by chronic alterations in soleus muscle activity. This is probably the result of the high level of metabolism and blood flow to the soleus during normal daily activity in the rat, which is sufficient to maintain EDD near optimal levels, even in untrained rats.

Another study examining long-term training used a high-intensity, sprint training protocol for 10 weeks in rats (30). Sprint training increased the hindlimb response to ACh and increased EDD in second order arterioles of the white portion of the gastrocnemius, but not in gastrocnemius feed arteries, second order arterioles from red region of gastrocnemius, or third order arterioles from the white portion. In contrast, McAllister et al. found that moderate-intensity training for 8–12 weeks resulted in enhanced EDD and increased endothelial NOS levels in arterioles from the red, but not white portion of gastrocnemius (33). Together with the data from Lash and Bohlen described above (25), these data indicate that the pattern of skeletal muscle resistance artery endothelial adaptation to exercise training is very complex, and much work still needs to be done in order to define the manner in which these adaptations occur in the skeletal muscle arteriolar network.

Coronary Vascular Bed

In larger arteries of the heart, short-term exercise training consistently increases EDD (Table 2). Studies in dogs (47) and pigs (28) report increased EDD following 7–10 days of daily exercise. Furthermore, 10 days of training in dogs increases NO production and eNOS expression in large coronary arteries (54). Interestingly, 7 days of training did not alter EDD in porcine resistance arterioles (28), indicating that endothelial adaptations appear to be limited to larger coronary vessels when the training program is short in duration. In contrast, adaptations to longer term exercise training are not observed in larger coronary arteries and appear to be limited to smaller resistance vessels. Oltman et al. (42) found that 13–20 weeks of training had no effect on EDD in porcine coronary arteries. In contrast, when porcine resistance arterioles were studied, 16–20 weeks of training resulted in an enhancement of EDD (38). Thus it appears that the smaller coronary resistance arterioles have enhanced EDD after a long-term training protocol, but enhanced EDD is observed in the larger coronary conduit arteries only after short term training.

Vascular Beds in Non-contracting Tissue

It has been proposed that there would be no training-induced adaptation in arteries of tissues that do not increase activity during exercise because these tissues have neither increased metabolism nor increased blood flow (31). Additionally, alterations in blood flow have been shown to be greatest in the specific muscle regions that have the greatest relative increase in activity during exercise training bouts (26). However, there is evidence in humans (see Maiorana et al. review (31)) that leg cycle training can elicit enhanced EDD in the forearm, tissue that would not be active during the training bouts. These data suggest that in humans exercise training may bring about systemic adaptations in endothelial function.

McAllister et al. (34) examined the responses of the porcine mesenteric, renal, and hepatic conduit arteries of pigs following long-term training and found no endothelial adaptations to exercise in these vessels. As summarized in Table 2, these data indicate that long term training in pigs does not alter EDD of non-skeletal muscle conduit arteries. Additionally, short term training does not alter flow-induced dilation of rat mesenteric arterioles (49), supporting the notion that vascular endothelium in non-active regions does not undergo adaptations to training.

As mentioned above, short term training has been reported to increase EDD in rat gracilis arterioles (24,51) and longer training protocols increase EDD in the rat spinotrapezius muscle (25). This is interesting because neither gracilis (1) nor spinotrapezius (40) have increased blood flow during exercise. Also, gracilis blood flow during exercise is not altered by training (1). Thus the fact that EDD is increased by training in these muscles suggests that training can induce adaptations in endothelial function in resistance vessels of skeletal muscle tissue that has little or no increase in activity or blood flow during training bouts. Furthermore, exercise training has been reported to enhance EDD in the rat carotid artery (23), suggesting that conduit arteries from inactive regions can also have training-induced endothelial augmentation. Thus while generalized adaptations in endothelial function do not occur in the pig model, most data from rat studies support results from human studies indicating that improved EDD can occur in resistance vessels in non-active regions of the body, and that exercise training has a non-specific, systemic effect on endothelial function. A potential explanation for improved EDD in arteries of tissue with no change or decreased blood flow during exercise is that vascular wall shear stress may increase in arteries perfusing these regions during exercise even if flow does not increase, due to decreased diameters of these arteries during exercise. During exercise there is a generalized increase in sympathetic nerve activity which causes vasoconstriction of arteries in many regions of the body. This vasoconstriction serves to shunt blood flow away from non-active regions toward the active regions that require increased oxygen and substrate delivery. It may be that vasoconstriction in non-active regions actually increases wall shear stress in the resistance vasculature of some non-active body regions, and that chronic exposure to this stimulus results in enhanced endothelial function in these regions. A second potential explanation is that some chemical mediator of enhanced endothelial function is produced in actively contracting muscle and carried via the vasculature to non-active regions.

Summary of Exercise Training in Normal Healthy Subjects

In summary, it appears that exercise training has non-uniform effects on arterial endothelium in normal healthy animals. The effects of training are determined by a number of known parameters including: the length of the training protocol, the branch order of the vasculature studied, and the specific tissue studied. Current results indicate that long term endurance exercise training induces enhanced EDD in the aorta and in resistance arteries of the heart. Short term, but not long term, training increases EDD in some other conduit arteries. Short term training also increases EDD in resistance arterioles of the gracilis and plantaris muscles. However, after long term training only modest increases in EDD are reported in the spinotrapezius and no changes are seen in soleus resistance arteries.

It may seem counterintuitive that short exposure to training causes adaptations in endothelial function while increasing the duration of exposure to the training stimulus causes a regression of these adaptations. It has been proposed that these observations reveal the sequence of adaptations in vascular control and structure throughout a training program (28,31). Increases in vascular wall shear stress produced during exercise hyperemia may be an important stimulus for augmentation of EDD (56) and subsequently for changes in vascular structure (43). Short term exercise training causes increases in shear stress, and the result is an increased expression of eNOS and possibly other proteins which help to increase EDD of arteries. As the duration of the training period increases, eNOS, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and other factors produced during exercise bouts elicit vascular remodeling, formation of new vessels and enlargement of existing vessels. These structural adaptations return vascular shear stress back to normal levels and EDD returns to normal. In support of this hypothesis, eNOS mRNA levels can be increased in as little as 2–4 hours by in vitro increases in flow (56), and increased eNOS protein expression can occur in 7–10 days (54). However, strong evidence regarding the nature and time course of structural adaptations in the arterial microcirculation is not currently available.

Endothelial Adaptations to Training in Conditions of Attenuated Endothelial Function

Aging

A number of studies have reported reduced EDD in both conduit and resistance vessels of older versus younger rats (Table 4). Sun et al. (50) found that gracilis arterioles of older rats had reduced sensitivity to wall shear stress and that an 18–20 wk treadmill training program increased sensitivity of these arterioles to shear stress. Responses to ACh were also increased by exercise training in the older rats, while responses to sodium nitroprusside were not altered. Spier et al. (48) compared EDD in first order arterioles of the soleus muscle (primarily slow-oxidative fibers) and of the white portion of the gastrocnemius muscle (primarily fast, glycolytic fibers). They found that aging reduced EDD to ACh in the arterioles of the soleus, but not the white gastrocnemius muscle, and that 12 weeks of low-intensity exercise training increased ACh-induced EDD in soleus arterioles from young and old rats and in white gastrocnemius arterioles from young, but not old rats. Both aging and exercise training effects were due to differences in NO production and training was found to increase both eNOS mRNA and eNOS protein levels in arterioles from both muscles in both age groups. Although treadmill running in old rats has been reported to reduce aortic sensitivity to lower doses of acetylcholine (10−7 M or less) (14,53) the preponderance of data, particularly in resistance vessels, indicate that exercise training in older subjects reverses the age-related decline in EDD.

Table 4.

Effect of exercise training on endothelial function in aging or pathology

| Reference | Species | Method | Vessels | EDD | EID | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGING | ||||||

| Hashimoto, 1990 (14) | Rat | In vitro rings | Aorta | ↔ max to Ach ↓ sensitivity to ACh |

12 wk treadmill training | |

| Spier et al., 2004 (48) | Fischer Rat | In vitro cannulated | SOL 1A | ↑ Ach & eNOS pro & mRNA in both O & Y | No effect of aging or ExTr | Aging ↓ Ach, NOS X abolished ExTr effect Aging ↑ eNOS, but not mRNA |

| WG 1A | ↑ Ach & eNOS in Y only, but ↑ mRNA in O & Y | No effect of aging or ExTr | Aging ↔ Ach; Aging ↔ eNOS & mRNA 12 wk ExTr at 15 m/min |

|||

| Sun et al., 2002 (50) | Rat | In vitro cannulated | Gracilis arterioles | Aging ↓ and ExTr ↑ flow-induced dilation | No change | Young and adult rats 18–20 wk training |

| Tsutsumi et al., 2001 (53) | Rat | In vitro rings | Aorta | ↓ at low doses ACh | No change | 3 month treadmill training |

| CORONARY DISEASE MODELS | ||||||

| Fogarty et al., 2004 (9) | Pig | In vitro cannulated | Coronary arterioles | ↑ VEGF in collateral dep. Only; dilation ↓ by NOS blockade | 14 wk training Ameroid occluder |

|

| Griffin et al., 1999 (12) | Pig (female) | In vitro rings | Coronary arteries | ↑ in normal and collateral-dependent | 16 wk training Ameroid occluder |

|

| Griffin et al., 2001 (13) | Pig (female) | In vitro cannulated | Coronary arterioles | Occlusion ↓ and ExTr ↑ BK dil. & eNOS | No change | 16 wk training Ameroid occluder |

| Indolfi et al., 2002 (15) | Rat | Various | Carotid arteries | ↑ eNOS & ↓ neointimal hyperplasia | Balloon angioplasty; Swim training 2 wks pre and 2 wks post injury | |

| Johnson et al., 2000 (21) | Pig (female) | In vitro rings | Pulmonary artery in ameroid occluder pigs | ↑ in NO dependent manner | No change | 16 wk training |

| Yi et al., 2000 (62) | Dog | In vivo Doppler | LCX | AA dilation ↓ by CHF, ↑ by ExTr | No change to PGI2 or NTG | Pacing-induced CHF for 4 wks or pacing + 2 hrs/d of treadmill |

| HYPERCHOLESTEROLEMIA | ||||||

| Jen et al., 2002 (19) | Rabbit | In vitro rings | Femoral | HF ↓ Ach dilation & Ca ExTr ↑ Ach & Ca |

HF ↓ and ExTr ↑ | Hypercholesterolemic 8 wk training |

| Niebauer et al., 1999 (41) | Mice | In vitro rings | Aorta | ↓ by ApoE KO & ↑ by ExTr | ↓ by ApoE KO, but ↔ to ExTr | Hypercholesterolemic (ApoE KO) Treadmill ExTr for 4 wks |

| Pynn et al., 2004 (44) | Mice | Various | Carotid artery injury in ApoE KO mice | ↑ eNOS ↓ neointimal lesions |

Hypercholesterolemic (ApoE KO); 3 wks running prior to injury & 3 wks after. | |

| Thompson et al., 2004 (52) | Pig (male) | In vitro rings | Coronary arteries | ↑ BK dilation and ↑ SOD -1 & 2; ↔ eNOS | Hypercholesterolemic 16–20 week training |

|

| Woodman et al., 2004 (57) | Pig (female) | In vitro rings | Coronary arteries | ↑ BK dilation via ↑ NO activity | ↑ in high fat and HF ExTr | Hypercholesterolemic 16–20 week training |

| Woodman et al., 2003 (58) | Pig (female) | In vitro rings | Brachial | ↓ by HF due to NO, PGI ↑ by ExTr due to other | No change | Hyperlipidemia 16 week training |

| Yang & Chen, 2003 (59) | Rabbit | In vitro rings | Aorta | ↑Ach dilation in normal, less ↑ in high chol. | Hypercholesterolemic 8 wks ExTr ↓ iNOS and adhesion molecule expression |

|

| Yang et al., 2003 (60) | Rabbit | In vitro rings | Aorta | ↑ Ach dil. in high chol. Due to ↑ NO & ↑ EDHF |

Hypercholesterolemic 2,4,6 wks ExTr; 4 & 6 wk ↓ adhesion molecule expression |

|

| HYPERTENSION | ||||||

| Arvola et al., 1999 (2) | Zucker Rats | In vitro rings | Mesenteric | ↑ ACh in Lean & Ob. | ↑ SNP in Lean & Obese | Obesity/Hypertension; 22 wks training ExTr effect KOed by L-NAME, but not COX or EDHF block |

| Carotid | ↑ ACh only in Obese | ↑ SNP in both | ||||

| Chen and Chiang, 1996 (3) | WKY & SHR Rats | In vitro rings | Aorta | ↑ PE constriction | 10 wk training ↓ PE abolished by L-NNA |

|

| Chen et al., 1996 (4) | WKY & SHR Rats | In vitro rings | Aorta Carotid |

↑ Ach due to NO ↔ ACh |

↔ SNP | 10 week training |

| Graham & Rush, 2004 (11) | WKY & SHR Rats | In vitro rings Molecular |

Aorta | ↑ Ach dilation & eNOS, ↔ SOD, catalase | No change | Hypertension 6 wk low intensity exercise |

| TYPE II DIABETES MELLITUS | ||||||

| Minami et al., 2002 (36) | OL-E Rat | In vitro rings | Aorta | D ↓ EDRF & EDHF | Diabetic Wheel running for 9 and 24 wks |

|

| Mesenteric | ExTr ↑ EDRF & EDHF | |||||

| Sakamoto et al., 1998 (46) | OL-E Rat | In vitro rings | Aorta | D ↓ Histamine | No change | Diabetic Wheel running 16 wks |

| Mesenteric | ExTr ↑ Histamine | |||||

EDD: endothelium-dependent dilation, G: gastrocnemius, R: red, W: white, ExTr: exercise training, HF: high fat, D: diabetes, KO: knock out.

Heart Disease

Griffin et al. (12) reported that 16 weeks of exercise training elicited increased EDD in coronary conduit arteries from both the collateral-dependent region and the normal region perfused by the left anterior descending artery (LAD) in a porcine model of chronic coronary occlusion. The enhanced EDD was the result of training-induced increases in production of NO and EDHF. Griffin et al. subsequently reported that coronary arterioles from the collateral-dependent region also exhibited training-induced increases in EDD and increased eNOS mRNA expression (13). Similarly, VEGF-induced EDD of coronary arterioles from the collateral-dependent region is enhanced by exercise training due to increased NO production (9). EDD of the pulmonary arteries from these coronary artery occluded pigs are also enhanced by 16 weeks of training (21), an adaptation to training that was not found in normal pigs (20). The increased pulmonary artery EDD appeared to result both from an increase in NO production and reduced production of a vasoconstrictor prostanoid. Thus in this group of studies using the coronary artery occlusion model, exercise training consistently enhances EDD in coronary and pulmonary arteries (Table 4).

There have also been some studies in which exercise training has been used in models of heart failure. In dogs with congestive heart failure induced by cardiac pacing, exercise training improved EDD (55,62). Wang et al. (55) reported that training preserved EDD of coronary arteries and increased eNOS protein expression. Yi et al. (62) reported that training preserved EDD of the left circumflex coronary artery to arachidonic acid, but that prostacyclin or nitroglycerin induced dilations were not altered by training. Thus training preserved EDD during the development of heart failure, but did not alter vascular smooth muscle function.

Hypercholesterolemia

A large number of studies have reported reduced EDD in hypercholesteremia (see Table 4) that is reversed or prevented by exercise training of mice (41,44), rabbits (19,59,60), and pigs (52,57,58). In a genetic model of mouse hypercholesterolemia, the apolipoprotein E knockout mouse, EDD of the thoracic aorta was decreased in relation to wild type mice and exercise training restored normal EDD (41). Expression of eNOS protein in the carotid artery of apolipoprotein E knockout mice was reduced, but was also restored to normal levels by exercise training (44). In rabbit aorta, hypercholesterolemia decreased EDD to ACH and this was linked to reductions in endothelial production of both NO and EDHF (59,60). Treadmill exercise training increased production of NO and EDHF and restored ACh-induced EDD. At least part of the reduction in endothelial production of NO and EDHF may result from impaired calcium signaling in endothelial cells, because hypercholesterolemia decreased the ACh-mediated elevation in endothelial cell calcium levels in rabbit femoral arteries, an alteration that was also reversed by exercise training (19). Finally, data from studies using pigs demonstrate that hypercholesterolemia decreases NO-mediated signaling in coronary and brachial arteries (52,57,58). Exercise training restored EDD of coronary arteries by increasing NO-mediated dilation and decreasing production of a prostanoid vasoconstrictor (57,58). Thus available results indicate that hypercholesterolemia reduces and exercise training restores NO-mediated EDD.

Hypertension

Studies using rings of aorta (3,4,11), carotid artery (2,4) and/or mesenteric artery (2) to examine the effects of exercise training in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) have consistently shown that EDD is reduced by hypertension and that attenuated NO production is at least partially responsible (see Table 4). Exercise training improves EDD in these arteries from SHR, and NO production is increased by training in these arteries (2,4). Additionally, exercise training increases expression of eNOS in SHR, which would explain the findings of increased NO production (11). Graham and Rush (11) also examined levels of superoxide dismutase and catalase, two enzymatic scavengers of oxygen free radicals, and found no difference in trained versus sedentary SHRs. Interestingly, levels of the pro-oxidant enzyme, NAD(P)H oxidase, were reduced by exercise training, which may have a beneficial effect on the half-life of NO in the vascular wall. Thus the improvement in EDD with training of hypertensive animals appears to result from increased NO production and availability, and not from improved free radical scavenging by anti-oxidant enzymes or from increases in other endothelium-derived dilators (2).

Type II Diabetes Mellitus

Two studies have examined the effects of exercise training on EDD in Type II diabetes mellitus. Sakamoto et al. (46) found that diabetes reduced aortic EDD in rats and that exercise training improved EDD. Training also increased insulin sensitivity and reduced plasma levels of glucose and insulin. A subsequent study of diabetic rats by Minami et al. (36) found that thoracic aorta and mesenteric artery rings from diabetic rats had reduced responses to ACh, with endothelial production of both NO and EDHF attenuated. Exercise training increased relaxation to ACh and production of both NO and EDHF was increased.

Conclusion

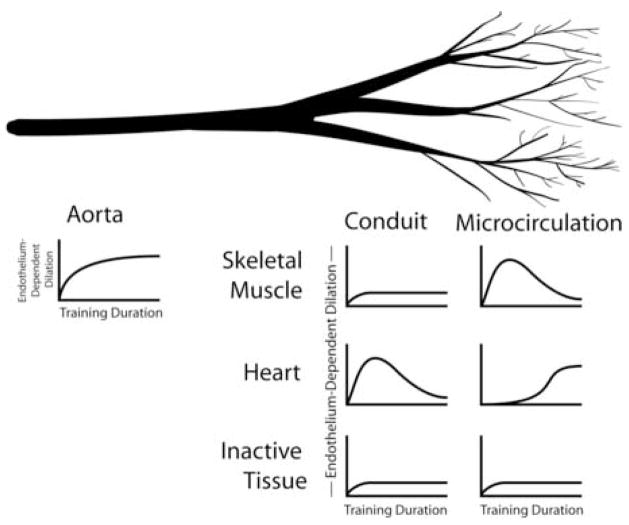

The evidence reviewed in this paper indicates that the effects of exercise training on EDD in normal animals is dependent both on the location of the arteries and on the duration of the training program (see Figure 1). In normal, healthy animals, the aortic endothelium consistently demonstrates increased EDD by the fourth week of training and this enhanced EDD persists throughout longer training protocols. In conduit arteries feeding skeletal muscle or inactive tissue, neither short term (1–4 wks) nor long term training consistently elicit increases in EDD, while coronary arteries have increased EDD following short, but not long term training. Coronary resistance arteries have increased EDD only after long term training. Resistance arteries from inactive tissues do not exhibit consistent increases in EDD after either short or long term training. In conditions in which EDD is compromised such as: aging, heart disease, hypercholesterolemia, Type II diabetes, and hypertension, results indicate that exercise training consistently preserves or restores EDD toward normal levels. The amount of increase in EDD is also greater than that seen in the few examples where EDD is improved by training in normal animals. It should be noted that almost all studies of exercise and endothelial function in pathological conditions have examined conduit arteries, so more work is needed to determine how exercise interacts with these various diseases in determining EDD and health. Finally, although some evidence indicates that exercise training can enhance EDD even in regions of the body that are not active during training bouts, evidence also indicates that some endothelial adaptations are specific to certain regions, as not all inactive body regions show this effect. Based on this body of evidence we conclude that long term exercise training does not significantly increase endothelial function of arteries in normal healthy animals, but exercise training can prevent or reverse the development of endothelial dysfunction that accompanies some diseases.

Figure 1.

Interaction between organ, vessel size, and training duration on the increase in endothelial-dependent dilation resulting from exercise training. A small deflection above baseline indicates small or inconsistent increases in endothelial function. A large deflection above baseline indicates larger and consistent increases in endothelial function.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: All manuscripts submitted to Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise® for evaluation are protected by international copyright laws. Reviewers have permission to print this manuscript on paper in their individual effort to provide a thorough critique of the scientific quality of the manuscript to the Editorial Office. Any other use of the material contained in the manuscript or distribution of the manuscript to other individuals is strictly prohibited by federal, state, and international laws governing copyright. Such actions are also in direct conflict with the professional and ethical standards of the American College of Sports Medicine and its official journal, Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise®.

The Editorial Office staff of MSSE® thanks you for participating in the review process. If you have any problems reviewing this manuscript, or you are unable to meet the deadline given, please write to the Editorial Office at msse@acsm.org.

References

- 1.Armstrong RB, Laughlin MH. Exercise blood flow patterns within and among rat muscles after training. Am J Physiol. 1984;246:H59–68. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1984.246.1.H59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arvola P, Wu X, Kahonen M, Makynen H, Riutta A, Mucha I, Solakivi T, Kainulainen H, Porsti I. Exercise enhances vasorelaxation in experimental obesity associated hypertension. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;43:992–1002. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen HI, I, Chiang P. Chronic exercise decreases adrenergic agonist-induced vasoconstriction in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:H977–H983. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.3.H977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen HI, I, Chiang P, Jen CJ. Exercise training increases acetylcholine-stimulated endothelium-derived nitric oxide release in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Biomed Sci. 1996;3:454–460. doi: 10.1007/BF02258049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen SJ, Wu CC, Yen MH. Exercise training activates large-conductance calcium-activated K(+) channels and enhances nitric oxide production in rat mesenteric artery and thoracic aorta. J Biomed Sci. 2001;8:248–255. doi: 10.1007/BF02256598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chu TF, Huang TY, Jen CJ, Chen HI. Effects of chronic exercise on calcium signaling in rat vascular endothelium. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279:H1441–1446. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.4.H1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delp MD, Laughlin MH. Time course of enhanced endothelium-mediated dilation in aorta of trained rats. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1997;29:1454–1461. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199711000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delp MD, McAllister RM, Laughlin MH. Exercise training alters endothelium-dependent vasoreactivity of rat abdominal aorta. J Appl Physiol. 1993;75:1354–1363. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.75.3.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fogarty JA, Muller-Delp JM, Delp MD, Mattox ML, Laughlin MH, Parker JL. Exercise training enhances vasodilation responses to vascular endothelial growth factor in porcine coronary arterioles exposed to chronic coronary occlusion. Circulation. 2004;109:664–670. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000112580.31594.F9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Furchgott RF, Zawadski JV. The obligatory role of endothelial cells in the relaxation of arterial smooth muscle by acetylcholine. Nature. 1980;299:373–376. doi: 10.1038/288373a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graham DA, Rush JW. Exercise training improves aortic endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation and determinants of nitric oxide bioavailability in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Appl Physiol. 2004;96:2088–2096. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01252.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griffin KL, Laughlin MH, Parker JL. Exercise training improves endothelium-mediated vasorelaxation after chronic coronary occlusion. J Appl Physiol. 1999;87:1948–1956. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.5.1948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Griffin KL, Woodman CR, Price EM, Laughlin MH, Parker JL. Endothelium-mediated relaxation of porcine collateral-dependent arterioles is improved by exercise training. Circulation. 2001;104:1393–1398. doi: 10.1161/hc3601.094274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hashimoto M. Effects of exercise on plasma lipoprotein levels and endothelium-dependent vasodilatation in young and old rats. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1990;61:440–445. doi: 10.1007/BF00236065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Indolfi C, Torella D, Coppola C, Curcio A, Rodriguez F, Bilancio A, Leccia A, Arcucci O, Falco M, Leosco D, Chiariello M. Physical training increases eNOS vascular expression and activity and reduces restenosis after balloon angioplasty or arterial stenting in rats. Circ Res. 2002;91:1190–1197. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000046233.94299.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jasperse JL, Laughlin MH. Flow-induced dilation of rat soleus feed arteries. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:H2423–2427. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.5.H2423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jasperse JL, Laughlin MH. Vasomotor responses of soleus feed arteries from sedentary and exercise-trained rats. J Appl Physiol. 1999;86:441–449. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.86.2.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jasperse JL, Woodman CR, Price EM, Hasser EM, Laughlin MH. Hindlimb unweighting decreases ecNOS gene expression and endothelium-dependent dilation in rat soleus feed arteries. J Appl Physiol. 1999;87:1476–1482. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.4.1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jen CJ, Chan HP, Chen HI. Chronic exercise improves endothelial calcium signaling and vasodilatation in hypercholesterolemic rabbit femoral artery. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:1219–1224. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000021955.23461.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson LR, Laughlin MH. Chronic exercise training does not alter pulmonary vasorelaxation in normal pigs. J Appl Physiol. 2000;88:2008–2014. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.6.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson LR, Parker JL, Laughlin MH. Chronic exercise training improves ACh-induced vasorelaxation in pulmonary arteries of pigs. J Appl Physiol. 2000;88:443–451. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.2.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson LR, Rush JW, Turk JR, Price EM, Laughlin MH. Short-term exercise training increases ACh-induced relaxation and eNOS protein in porcine pulmonary arteries. J Appl Physiol. 2001;90:1102–1110. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.3.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kemi OJ, Haram PM, Wisloff U, Ellingsen O. Aerobic fitness is associated with cardiomyocyte contractile capacity and endothelial function in exercise training and detraining. Circulation. 2004;109:2897–2904. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000129308.04757.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koller A, Huang A, Sun D, Kaley G. Exercise training augments flow-dependent dilation in rat skeletal muscle arterioles. Role of endothelial nitric oxide and prostaglandins. Circ Res. 1995;76:544–550. doi: 10.1161/01.res.76.4.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lash JM, Bohlen HG. Time- and order-dependent changes in functional and NO-mediated dilation during exercise training. J Appl Physiol. 1997;82:460–468. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.82.2.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laughlin MH, Korthuis RJ, Duncker DJ, Bache RJ. Control of Blood Flow to Cardiac and Skeletal Muscle. In: Rowell LB, Shepherd JT, editors. Handbook of Physiology: Exercise: Regulation and Integration of Multiple Systems. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. pp. 705–769. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laughlin MH, Pollock JS, Amann JF, Hollis ML, Woodman CR, Price EM. Training induces nonuniform increases in eNOS content along the coronary arterial tree. J Appl Physiol. 2001;90:501–510. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.2.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laughlin MH, Rubin LJ, Rush JW, Price EM, Schrage WG, Woodman CR. Short-term training enhances endothelium-dependent dilation of coronary arteries, not arterioles. J Appl Physiol. 2003;94:234–244. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00246.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laughlin MH, Schrage WG, McAllister RM, Garverick HA, Jones AW. Interaction of gender and exercise training: vasomotor reactivity of porcine skeletal muscle arteries. J Appl Physiol. 2001;90:216–227. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.1.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laughlin MH, Woodman CR, Schrage WG, Gute D, Price EM. Interval sprint training enhances endothelial function and eNOS content in some arteries that perfuse white gastrocnemius muscle. J Appl Physiol. 2004;96:233–244. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00105.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maiorana A, O’Driscoll G, Taylor R, Green D. Exercise and the nitric oxide vasodilator system. Sports Med. 2003;33:1013–1035. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200333140-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Massett MP, Koller A, Kaley G. Hyperosmolality dilates rat skeletal muscle arterioles: role of endothelial K(ATP) channels and daily exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2000;89:2227–2234. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.6.2227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McAllister RM, Jasperse JL, Laughlin MH. Nonuniform effects of endurance exercise training on vasodilation in rat skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:753–761. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01263.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McAllister RM, Kimani JK, Webster JL, Parker JL, Laughlin MH. Effects of exercise training on responses of peripheral and visceral arteries in swine. J Appl Physiol. 1996;80:216–225. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.80.1.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McAllister RM, Laughlin MH. Short-term exercise training alters responses of porcine femoral and brachial arteries. J Appl Physiol. 1997;82:1438–1444. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.82.5.1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Minami A, Ishimura N, Harada N, Sakamoto S, Niwa Y, Nakaya Y. Exercise training improves acetylcholine-induced endothelium-dependent hyperpolarization in type 2 diabetic rats, Otsuka Long-Evans Tokushima fatty rats. Atherosclerosis. 2002;162:85–92. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(01)00685-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moyna NM, Thompson PD. The effect of physical activity on endothelial function in man. Acta Physiol Scand. 2004;180:113–123. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6772.2003.01253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Muller JM, Myers PR, Laughlin MH. Vasodilator responses of coronary resistance arteries of exercise-trained pigs. Circulation. 1994;89:2308–2314. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.5.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Musch TI, Haidet GC, Ordway GA, Longhurst JC, Mitchell JH. Training effects on regional blood flow response to maximal exercise in foxhounds. J Appl Physiol. 1987;62:1724–1732. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1987.62.4.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Musch TI, Poole DC. Blood flow response to running in the rat spinotrapezius muscle. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:H2730–H2734. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.6.H2730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Niebauer J, Maxwell AJ, Lin PS, Tsao PS, Kosek J, Bernstein D, Cooke JP. Impaired aerobic capacity in hypercholesterolemic mice: partial reversal by exercise training. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:H1346–1354. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.4.H1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oltman CL, Parker JL, Laughlin MH. Endothelium-dependent vasodilation of proximal coronary arteries from exercise-trained pigs. J Appl Physiol. 1995;79:33–40. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.79.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prior BM, Lloyd PG, Yang HT, Terjung RL. Exercise-induced vascular remodeling. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2003;31:26–33. doi: 10.1097/00003677-200301000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pynn M, Schafer K, Konstantinides S, Halle M. Exercise training reduces neointimal growth and stabilizes vascular lesions developing after injury in apolipoprotein e-deficient mice. Circulation. 2004;109:386–392. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000109500.03050.7C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rush JW, Turk JR, Laughlin MH. Exercise training regulates SOD-1 and oxidative stress in porcine aortic endothelium. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H1378–1387. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00190.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sakamoto S, Minami K, Niwa Y, Ohnaka M, Nakaya Y, Mizuno A, Kuwajima M, Shima K. Effect of exercise training and food restriction on endothelium-dependent relaxation in the Otsuka Long-Evans Tokushima Fatty Rat, a model of spontaneous NIDDM. Diabetes. 1998;47:82–86. doi: 10.2337/diab.47.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sessa WC, Pritchard K, Sedayi N, Wang J, Hintze TH. Chronic exercise in dogs increases coronary vascular nitirc oxide production and endothelial cell nitric oxide synthase gene expression. Circ Res. 1994;74:349–353. doi: 10.1161/01.res.74.2.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spier SA, Delp MD, Meininger CJ, Donato AJ, Ramsey MW, Muller-Delp JM. Effects of ageing and exercise training on endothelium-dependent vasodilatation and structure of rat skeletal muscle arterioles. J Physiol. 2004;556:947–958. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.060301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sun D, Huang A, Koller A, Kaley G. Adaptation of flow-induced dilation of arterioles to daily exercise. Microvasc Res. 1998;56:54–61. doi: 10.1006/mvre.1998.2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sun D, Huang A, Koller A, Kaley G. Decreased arteriolar sensitivity to shear stress in adult rats is reversed by chronic exercise activity. Microcirculation. 2002;9:91–97. doi: 10.1038/sj/mn/7800124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun D, Huang A, Koller A, Kaley G. Short-term daily exercise activity enhances endothelial NO synthesis in skeletal muscle arterioles of rats. J Appl Physiol. 1994;76:2241–2247. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.76.5.2241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thompson MA, Henderson KK, Woodman CR, Turk JR, Rush JW, Price E, Laughlin MH. Exercise preserves endothelium-dependent relaxation in coronary arteries of hypercholesterolemic male pigs. J Appl Physiol. 2004;96:1114–1126. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00768.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tsutsumi K, Kusunoki M, Hara T, Okada K, Sakamoto S, Ohnaka M, Nakay Y. Exercise improved accumulation of visceral fat and simultaneously impaired endothelium-dependent relaxation in old rats. Biol Pharm Bull. 2001;24:88–91. doi: 10.1248/bpb.24.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang J, Wolin MS, Hintze TH. Chronic exercise enhances endothelium-mediated dilation of epicardial coronary artery ini conscious dogs. Circ Res. 1993;73:829–838. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.5.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang J, Yi GH, Knecht M, Cai BL, Poposkis S, Packer M, Burkhoff D. Physical training alters the pathogenesis of pacing-induced heart failure through endothelium-mediated mechansisms in awake dogs. Circulation. 1997;96:26983–22692. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.8.2683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Woodman CR, Muller JM, Rush JW, Laughlin MH, Price EM. Flow regulation of ecNOS and Cu/Zn SOD mRNA expression in porcine coronary arterioles. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:H1058–1063. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.3.H1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Woodman CR, Turk JR, Rush JW, Laughlin MH. Exercise attenuates the effects of hypercholesterolemia on endothelium-dependent relaxation in coronary arteries from adult female pigs. J Appl Physiol. 2004;96:1105–1113. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00767.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Woodman CR, Turk JR, Williams DP, Laughlin MH. Exercise training preserves endothelium-dependent relaxation in brachial arteries from hyperlipidemic pigs. J Appl Physiol. 2003;94:2017–2026. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01025.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang AL, Chen HI. Chronic exercise reduces adhesion molecules/iNOS expression and partially reverses vascular responsiveness in hypercholesterolemic rabbit aortae. Atherosclerosis. 2003;169:11–17. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(03)00013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang AL, Jen CJ, Chen HI. Effects of high-cholesterol diet and parallel exercise training on the vascular function of rabbit aortas: a time course study. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95:1194–1200. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00282.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yang AL, Tsai SJ, Jiang MJ, Jen CJ, Chen HI. Chronic exercise increases both inducible and endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene expression in endothelial cells of rat aorta. J Biomed Sci. 2002;9:149–155. doi: 10.1007/BF02256026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yi GH, Zwas D, Wang J. Chronic exercise training preserves prostaglandin-induced dilation of epicardial coronary artery during development of heart failure in awake dogs. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2000;60:137–151. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(00)00057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]