Abstract

The progesterone receptor (PR) plays a pivotal role in proper development and function of the mammary gland and has also been implicated in mammary tumorigenesis. PR is a ligand-activated transcription factor; however, relatively, little is known about its mechanisms of action at endogenous target promoters. The aim of our study was to identify a natural PR-responsive gene and investigate its transcriptional regulation in the mammary microenvironment. Our experiments revealed FKBP5 as a direct target of the PR, because it exhibited a rapid activation by progestin that was cycloheximide independent and correlated with recruitment of RNA polymerase II to the promoter. Site-directed mutagenesis and chromatin immunoprecipitation assays showed that progestin responsiveness is mediated through a composite element in the first intron, to which the PR binds concomitantly with GATA-2. Mutational analysis of the element revealed that the GATA-2 site is essential for progestin activation. Direct binding of PR to DNA contributes to the efficiency of activation but is not sufficient, suggesting that the receptor makes important protein-protein interactions as part of its mechanism of action at the FKBP5 promoter. Using chromatin immunoprecipitation assays we also determined that the intronic region is in communication with the promoter, probably via DNA looping. Time course analysis revealed a cyclical pattern of PR recruitment to the FKBP5 gene but a persistent recruitment to the mouse mammary tumor virus promoter, indicating that receptor cycling is a gene-specific phenomenon rather than a characteristic of the receptor itself. Our study offers new insight in the nature of PR-regulated transcription in mammary cancer cells.

Progesterone receptor cooperates with GATA-2 to activate the FKBP5 gene in a cyclic fashion through a composite element located in the first intron.

The diverse biological effects of progesterone are mediated by the progesterone receptor (PR) and are exerted predominantly in the female reproductive system (uterus and ovary), in the mammary gland, and in the brain (1). Generation of the PR knockout mouse proved that the progesterone-proliferative signal is essential for the normal morphogenesis and function of mammary tissue, but also contributes to the high incidence of tumors observed in the carcinogen-induced murine mammary tumor model (reviewed in Ref. 2). Among the growing number of reports showing an association between PR and breast cancer, of primary interest are the results of a large clinical study that concluded that administration of estrogen plus progestin, as a hormonal replacement therapy to postmenopausal women, increases breast cancer risk above that of estrogen alone (3). Furthermore, recent in vitro and in vivo studies demonstrated a functional relationship between PR and expression of BRCA1 (4,5), suggesting that increased progestin activity, caused by loss of function of the tumor suppressor gene, may be one mechanism that leads to increased breast cancer risk in carriers of BRCA1 mutations. All these findings strongly support the idea that progestins, through PR, play an important role in the etiology and/or progression of breast cancer.

The PR, along with the glucocorticoid, mineralocorticoid, and androgen receptors (GR, MR, and AR, respectively), is a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily of transcription factors. According to established models, these receptors dissociate from a multiprotein chaperone complex upon ligand binding, homodimerize, and accumulate in nucleus, where they bind to palindromic hormone response elements (HREs) within the promoter of target genes. The bound receptors recruit cofactors that interact with components of the general transcriptional machinery and/or facilitate local chromatin remodeling, resulting in the formation of productive transcription initiation complexes at the target promoter (6). However, recent studies using techniques of genome-wide analysis indicate that this is an oversimplified model. Binding sites of estrogen receptor (ER), AR, and GR defined by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-chip analysis (7,8,9) do not uniformly consist of classically defined palindromic HREs. Many receptor-binding regions contain only half-sites or atypical HREs and binding sites for other transcription factors, some of which have been shown to be necessary for full steroid responsiveness (10,11,12). This is not necessarily surprising, because, to mediate a plethora of physiological processes, steroid receptors must regulate diverse promoters in a variety of cell types. Consequently, it is logical to assume that they exploit different mechanisms to control transcription, depending on the cellular and promoter context.

An appreciation of the central role of PR in mammary tissue biology has motivated several efforts to identify direct PR target genes (13,14,15), but very few studies have followed through in examining the mechanisms PR employs to regulate these genes. To fully elucidate PR function in the mammary tissue, a more comprehensive knowledge of the mechanisms it uses to modulate the expression of different target genes in the mammary microenvironment is needed. As a matter of fact, most of our current knowledge regarding the PR-regulated transcription is based on in vitro experiments using synthetic promoter constructs containing multimerized, idealized progesterone response elements (PREs) (1), or on studies with the mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) promoter, a model system that has been widely used to study chromatin dynamics after steroid hormone induction (16,17,18). Even though the MMTV promoter has proven to be an invaluable tool in elucidating the action of steroid receptors in transcriptional regulation, it may represent only one class of target promoters that contain well-defined, independently functioning HREs. Thus, the mechanisms by which PR acts on endogenous mammalian promoters with distinct promoter characteristics remain largely uninvestigated.

To address this issue, we undertook the study of the PR-regulated expression of an endogenous target gene, FKBP5, in a mouse mammary adenocarcinoma cell line. FKBP5 encodes a 51-kDa immunophilin that functions as a chaperone for the unliganded GR and PR (19,20) and has been reported to be induced by several steroid hormones (19,20,21). Its proximal promoter had been reported to be progestin responsive but does not contain canonical PREs (22). We determined that PR activates the FKBP5 gene from an intronic composite PRE that includes a binding site for GATA factors. PR and GATA-2 co-occupy this element and contact the proximal promoter, probably through a looping mechanism. GATA-2 binding to the composite element is essential for progestin responsiveness, whereas PR binding contributes to its efficiency but is not sufficient. We also show that PR and GATA-2 associate with the FKBP5 gene in a cyclic fashion and recruit a variety of coactivators with distinct kinetics. Our study has disclosed a previously unrecognized synergism between PR and GATA-2 and documented PR cycling on a target gene, a phenomenon that has been observed for several other nuclear receptors (23,24,25).

Results

Progestin regulation of FKBP5 in 3017.1 cells

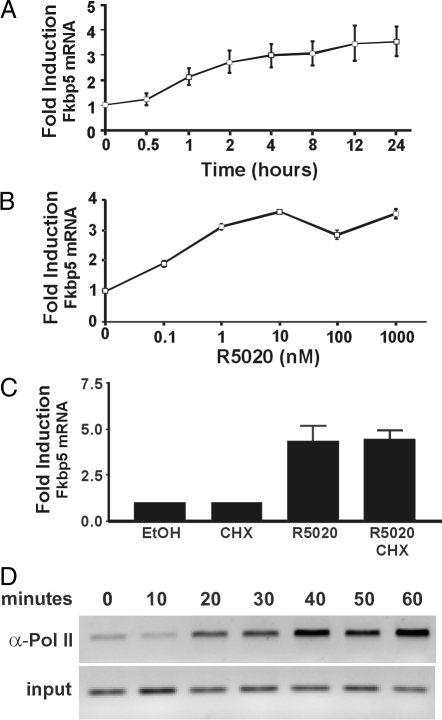

FKBP5 has been reported to be up-regulated by progestins in several cell lines (13,14). To confirm that this is the case in our cell system, we performed a time-course study, in which 3017.1 cells, a mouse mammary adenocarcinoma-derived cell line stably expressing chicken PR, were exposed to R5020, a synthetic progestin, for up to 24 h (Fig. 1A). Total RNA was collected and RT-PCR was used to evaluate the level of FKBP5 mRNA relative to the expression level of β-actin. Induction occurred rapidly because an increase in FKBP5 mRNA levels was observed just 60 min after R5020 treatment. Induction peaked at 3.5-fold between 8–12 h, and FKBP5 mRNA levels remained elevated for at least 24 h. In addition, Western blot analysis showed R5020-induced increases in FKBP5 protein levels that corresponded to the changes in the mRNA levels (data not shown). The effect of R5020 was dose dependent (Fig. 1B), and cycloheximide treatment had no effect on the accumulation of FKBP5 mRNA in R5020-treated cells, indicating that the FKBP5 gene is a direct, transcriptional target of progestin signaling (Fig. 1C). We also performed ChIP analysis to monitor the time course of progestin-dependent loading of RNA polymerase II on the FKBP5 promoter in 3017.1 cells (Fig. 1D). Association of RNA polymerase II increased gradually starting at 20 min of R5020 treatment (Fig. 1D). Taken together, these data indicate that the FKBP5 gene is transcriptionally up-regulated by PR, consistent with a previous report of the progestin regulation of the gene in human breast cancer cells (22).

Figure 1.

Progestin regulation of FKBP5. Time course (panel A) and dose-response curves (panel B) of FKBP5 mRNA levels in 3017.1 cells. Cells were treated with 10 nm R5020 for different time points up to 24 h (A) or with 0.1 nm to 1 μm R5020 for 24 h (B). Total RNA was isolated and RT-PCR was performed as described in Materials and Methods. The FKBP5 mRNA levels were evaluated relative to vehicle-treated cells and normalized to β-actin mRNA levels. C, Cells were treated with EtOH or cycloheximide (CHX) (1 μg/ml) for 6 h or pretreated with CHX for 2 h and then treated with 10 nm R5020 for 4 h. RNA was isolated and analyzed as described above. Results in panels A–C are presented as the mean ± se of two to four independent experiments. D, Temporal occupancy of the FKBP5 promoter by RNA polymerase II as measured by ChIPs. Chromatin was prepared from 3017.1 cells treated with R5020 for the indicated time points and immunoprecipitated with antibodies against polymerase II (α Pol II). Purified DNA was amplified using primers that span approximately 300 bp of the promoter region.

Identification of a functional PRE by ChIPs and reporter assays

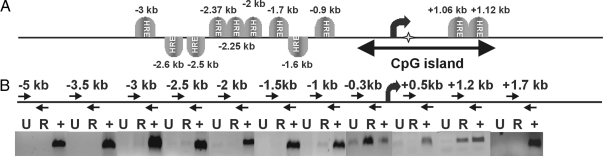

An earlier study of the human FKBP5 gene demonstrated weak progestin responsiveness (∼2-fold) mediated through the first 500 bp of proximal promoter sequences upstream of the transcription start site (TSS), a region without obvious PREs but rich in conserved Sp1 sites (22). The authors speculated that these sites might mediate indirect PR binding to the promoter given previously documented cross talk between Sp1 and PR (26). However, when we transfected a reporter construct containing a fragment of the mouse FKBP5 gene that spanned from −1455 to +242 bp, it failed to show progestin responsiveness in either 3017.1 or Hela cells (data not shown). Therefore, we performed in silico analysis to better define the murine FKBP5-regulatory regions. We investigated a region of approximately 7 kb flanking the TSS. Using the MatInspector program by Genomatix, we identified several potential PREs scattered throughout this region (Fig. 2A). We also found a long CpG island extending from the proximal promoter through the 5′-region of the first intron (−400 bp to +1200 bp) (Fig. 2A). These islands have been found to predict the location of functional regulatory elements, suggesting that the FKBP5-regulatory regions may extend downstream of the TSS. As it has been described before for the GR (27), we used a ChIP scanning assay to identify genomic segments occupied by PR in vivo. We designed 10 sets of primers (see Table 2) spanning the 7-kb sequence and used them to amplify DNA immunoprecipitated through ChIP assay with an antibody against the B isoform of PR (PRB). Our results showed PR occupancy on the proximal promoter (centered around −300 bp), as well as in the first intron, about 1.2 kb downstream of the TSS (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, our computer analysis revealed the absence of PREs in the first 1000 bp, 5′ to the TSS, but had predicted two potential PREs in the same downstream region (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

ChIP scanning of an FKBP5 genomic fragment reveals PR loading on two regions. A, In silico analysis of the murine FKBP5 gene. Positions of the TSS (large curved arrow), CpG island, first noncoding exon/intron boundary (asterisk), and potential PREs are shown. B, ChIP scanning analysis of the 5′-region of the FKBP5 gene. Primers (small arrows) designed to span small subregions of a 7-kb fragment flanking the TSS were used to amplify DNA derived from chromatin immunoprecipitated with an antibody against the PR. Results of a representive ChIP analysis are shown. U, Untreated; R, treated with 30 nm R5020 for 1 h; +, input DNA, used as a PCR-positive control. Three independent experiments generated the same results.

Table 2.

Primers used for ChIPs

| Primers | Position | Sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| −5.0 kb | ||

| (f) | (−4961/−4938) | aggtctgtgtgcctcatgagctc |

| (r) | (−4545/−4569) | ccaccaaatccacctatcctcgatc |

| −3.5 kb | ||

| (f) | (−3510/−3490) | gagaccttgactgccctaccc |

| (r) | (−3160/−3183) | tggaggaggtactgtaggaggagt |

| −3.0 kb | ||

| (f) | (−2972/−2951) | gaagtgtgtgtgtgtttggggg |

| (r) | (−2610/−2631) | gtctttttgtgcccaggtttgc |

| −2.5 kb | ||

| (f) | (−2499/−2479) | catggggcctttctcagtgtg |

| (r) | (−2127/−2146) | atcccaggagacagccaggc |

| −2.0 kb | ||

| (f) | (−1968/−1945) | aagtgctactatcccttgccacat |

| (r) | (−1616/−1632) | ctgttcgctaatgccagttgg |

| −1.5 kb | ||

| (f) | (−1455/−1428) | cttttctgtagaggtctttgaggatagg |

| (r) | (−980/−1003) | gaggggaggagaaactataaaagt |

| −1.0 kb | ||

| (f) | (−1004/−980) | gacttttatagtttctcctcccctc |

| (r) | (−632/−654) | ctgggtgactcctatagacgctc |

| −0.3 kb | ||

| (f) | (−273/−256) | gagctccatccctcttctccg |

| (r) | (+45/+28) | aacgcacgctcggtcgct |

| +0.5 kb | ||

| (f) | (+326/+325) | ctcttctccagcgtctccct |

| (r) | (+641/+622) | tcagccacctccgagacaac |

| +1.2 kb | ||

| (f) | (+910/+931) | ccagcattttgtgtgtgtgtgt |

| (r) | (+1133/+1116) | caccctgtctcgagcccc |

| +1.7 kb | ||

| (f) | (+1522/+1544) | atcctcatttgcctgactttttg |

| (r) | (+1840/+1820) | tggtggggcccgcctttaatc |

Primers are shown along with their binding sites relevant to the TSS and the length of the amplified fragment. f, Forward; r, reverse.

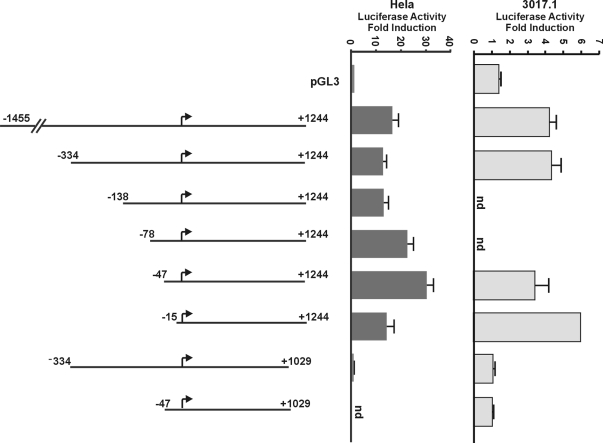

To determine which of the identified PR-binding regions in the Fkbp gene mediate progestin-responsiveness, we generated a luciferase reporter construct containing approximately 2.7 kb of the FKBP5 gene, extending from the promoter through the first intron (−1455 to +1244 bp). In transfected HeLa cells, treatment with R5020 strongly induced luciferase expression (∼15-fold over control) (Fig. 3), indicating that the progestin response element(s) are contained within this region. A number of 5′-deletions revealed that sequences upstream of the TSS are largely dispensable for progestin responsiveness; the sequence from −1455 to −15 can be deleted without loss of R5020-induced luciferase activity, although the magnitude of the induction was somewhat variable in Hela cells as more of the promoter was deleted. We also mutated transcription factor-binding sites in the proximal promoter region, individually or in combination, including the Sp1 sites, and found that they did not abrogate progestin responsiveness (data not shown). In contrast, within the first intron of the gene, deletion of the region between +1244 and +1029 results in a complete loss of R5020 induction, clearly showing that there are cis-regulatory elements in this region responsible for the progestin responsiveness of the gene. Most of the same constructs were also tested in the 3017.1 cells. The magnitude of progestin induction was lower in these cells but consistent with induction of the endogenous gene (Fig. 1A). Importantly, the reporters tested in 3017.1 cells showed the same pattern of progestin responsiveness with the proximal promoter region being largely dispensable and the intronic region being critical. When combined with the results of the in vivo ChIP experiments, the transfection experiments indicate an important PR-binding site in the first intron, 1.2 kb downstream of the TSS.

Figure 3.

The PR-responsive region of FKBP5 is located approximately 1.2 kb downstream of the TSS. An approximately 2.6-kb genomic fragment (−1455 to +1244 bp) was cloned into the promoterless luciferase reporter vector pGL3-basic. A number of 5′- and 3′-deletion constructs were generated as described in Materials and Methods and transfected into either HeLa cells along with PR or 3017.1 cells. After 24 h of R5020 treatment, cells were harvested and lysed, and whole-cell extracts were assayed for luciferase and β-galactosidase activity. The values were normalized for β-galactosidase and are expressed as fold luciferase activity with respect to vehicle-treated cells. Data shown here represent the mean ± se of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. nd, Not determined.

Mutational analysis of intronic PREs

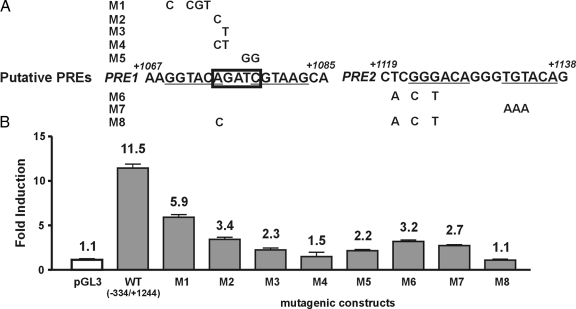

The consensus sequence for binding of GR, PR, AR, and MR is an inverted repeat with a three-nucleotide spacer region: AGAACAnnnTGT TCT, where the underlined nucleotides are most important for receptor binding (28). As described above, we had identified, by in silico analysis, two potential PREs in the +1029 to +1244 intronic region, namely PRE1 and PRE2 (Fig. 4). To confirm these results we used several other algorithms that predict potential transcription factor-binding sites using either the Transfac or the Jaspar database, and all predicted one or both of the above PREs (data not shown). Finally, we applied a program called Tiger HRE Finder (29) that specifically predicts de novo steroid hormone response elements (SREs) using two different methods, and both predicted only PRE2.

Figure 4.

Mutational analysis of two potential PREs in the first intron of FKBP5. A, Computer analysis of the mouse FKBP5 gene predicted two potential PR-binding sites, PRE1, located at +1069 to +1087 bp, and PRE2, located at +1122 to +1138 bp, as well as a GATA site (in box) in the first intron. B, A series of constructs (M1–M8) were generated by mutating the wild-type murine FKBP5 intronic sequences at the positions depicted (see Materials and Methods for details) and were transfected into HeLa cells along with PR. After 24 h of R5020 treatment, cells were harvested and lysed, and whole-cell extracts were assayed for luciferase and β-galactosidase activity. The values were normalized for β-galactosidase and are expressed as fold luciferase activity with respect to vehicle-treated cells. Data shown here represent the mean ± se of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. Fold inductions are denoted over each bar. WT, Wild type.

To determine which of the putative PREs might be functional, we carried out mutational analysis in the context of the (−334/+1244)FKBP5-luc construct, as depicted in Fig. 3. Mutation of PRE1 resulted in a 50% reduction of luciferase activity (construct M1; Fig. 4B). However, PRE1 overlaps with a potential GATA-binding site (boxed sequence in Fig. 4, A and B), which was predicted by MatInspector and also found by screening the Jaspar database (30). Mutation of either the first A or G of the putative GATA site (constructs M2 and M3; Fig. 4B) results in a dramatic reduction in progestin responsiveness, whereas mutation of both (construct M4; Fig. 4B) eliminates it. Mutation of the TC dinucleotide in the potential GATA site also leads to a severe loss of progestin induction (construct M5; Fig. 4B). These results are consistent with those of Ko and Engel (31), who identified AGATCTTA as a sequence that is recognized well by GATA-2 and -3, with the first three nucleotides being the most critical determinants of recognition specificity and affinity and the other positions playing an important contributing role. Several of the nucleotides mutated in these constructs, particularly the first G of the potential GATA site (construct M3), fall within the spacer between the putative PRE half-sites. Because it is the number of spacer nucleotides rather their identity that is important (28), mutation of these nucleotides would not be predicted to have a dramatic effect on PR binding. These results raise the possibility that GATA binding may be important for progestin responsiveness of the gene. The 50% loss of progestin responsiveness we observe when we mutate sequences 5′ to the GATA site (construct M1) may be due to alteration of the flanking sequence known to affect factor binding (32).

Mutation of either half of PRE2 led to a 70% loss of activity (constructs M6 and M7; Fig. 4B), suggesting that it is a functional PR-binding site. When mutations were introduced into both the putative GATA site (first A nucleotide) and PRE2 (construct M8; Fig. 4B), progestin responsiveness was completely eliminated, indicating the importance of both elements. An in silico search for transcription factor-binding sites in the human long isoform of FKBP5 (ENST00000337746) identified a putative GATA binding site and three potential PREs, two of which are shown in supplemental Fig. 1A, published as supplemental data on The Endocrine Society’s Journals Online web site at http://mend.endojournals.org. Notably, these elements are located in the first intron, and the relative positions of the GATA site and the PREs are also conserved with the former located about 50 bp 5′ to the latter in both the human and mouse genes.

To determine whether these PREs are functional, we cloned this region into a luciferase reporter construct containing the MMTV core promoter (supplemental Fig. 1B). Although the core promoter alone was not induced by progestins (data not shown), the intronic region from the human FKBP5 gene conferred progestin responsiveness to the core promoter in both Hela and T47D cells (supplemental Fig. 1C). ChIP assays carried out on chromatin from T47D cells showed that progestins strongly induce the association of RNA polymerase II with the TSS upstream of the human intronic PRE in response to R5020 treatment (supplemental Fig. 2A). Also, in ligand-dependent fashion, the PR strongly associates with the intronic PRE region (supplemental Fig. 2B). These data indicate that the intronic PRE region is functional in the human FKBP5 gene.

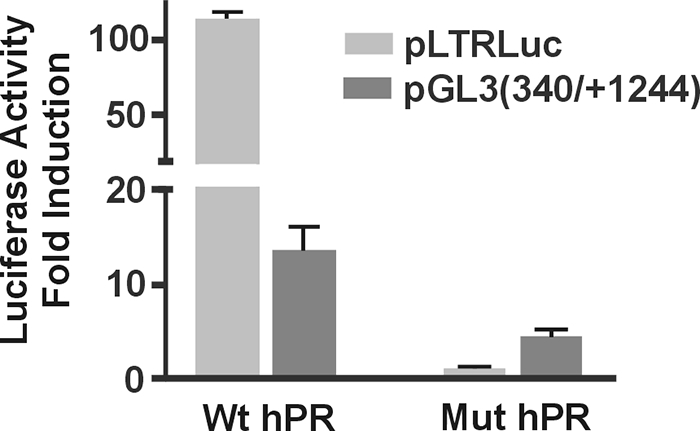

DNA binding of the PR is important, but not absolutely necessary, for FKBP5 regulation

The mutational analysis shown in Fig. 4 revealed that when the GATA site is mutated, progestin responsiveness is completely abolished, suggesting that the binding of a GATA factor is critical. However, mutation of PRE2 reduces progestin responsiveness but does not eliminate it (Fig. 4B). It is possible, therefore, that DNA binding of PR contributes to the full progestin response but is not sufficient for it. To test this hypothesis, we transfected HeLa cells with either wild-type human PRB (hPRB) or a mutant hPRB that has been modified in its DNA-binding domain, so as not to bind to PREs but to estrogen response elements (EREs) (33). The pLTRLuc plasmid (34), which contains the MMTV promoter, was used as a control. The MMTV promoter contains several PREs, which are required for activation by progestins through the direct binding of PR (35). As expected, the wild-type hPR efficiently activated the MMTV promoter upon exposure to R5020, but the mutant hPR was completely inactive, confirming that it has indeed lost its ability to recognize and bind to PREs (Fig. 5). In contrast, both the wild-type PR and the DNA binding mutant were able to transactivate the FKBP5 reporter construct, pGL3(−340/+1244) (Fig. 5). Relative to the wild type, however, the mutant was about 70% less effective, which correlates very well with the effect of mutating PRE2 (constructs M6, M7; Fig. 4B) Similar transfections using an expression vector for hERα showed that the ER cannot induce the pGL3(−340/+1244) construct in response to estrogen treatment (data not shown), indicating that the ability to bind EREs does not contribute to the ability of the PR mutant to transactivate the FKBP5 promoter. Consistent with this finding, in silico analysis of this region of the FKBP5 gene did not reveal any EREs (data not shown).

Figure 5.

DNA binding of the PR is important but not absolutely necessary for progestin regulation of FKBP5. HeLa cells were transfected with either the wild type (Wt) hPRB or a DNA-binding mutant (Mut) hPRB along with either an MMTV promoter-containing plasmid (pLTRLuc) or an FKBP5 construct (pGL3(−340/+1244). Cells were harvested 24 h after R5020 treatment and assayed for luciferase activity, and results were normalized for β-galactosidase activity. Data are presented as fold induction over vehicle-treated cells. Results are presented as the mean ± se of duplicates of three independent experiments.

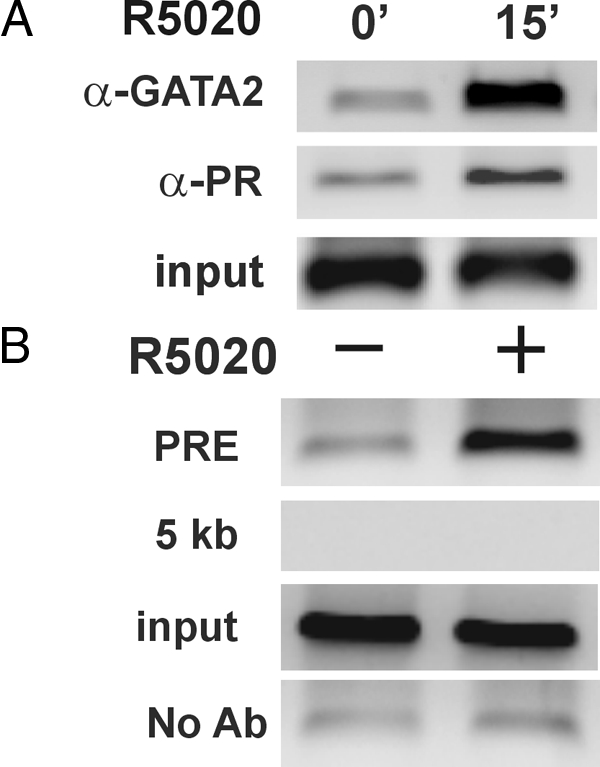

Association of GATA-2 with the intronic PRE

A previous study had shown that, in contrast to GATA-1, GATA-2 and -3 bind strongly to an AGATC motif (31). mRNA and Western blot expression analyses showed that only GATA-2, -3, and -4 are expressed in the 3017.1 cells and that Hela cells express GATA-2 but not GATA-3 (data not shown). To determine whether GATA factors bind to the intronic PRE, we carried out ChIP assays. The results in Fig. 6A show that GATA-2 recruitment is induced in the presence of the progestin. ChIP assays performed with antibodies against GATA-3 and GATA-4 were negative for FKBP5 DNA (data not shown). To determine whether the two factors co-occupy the composite PRE, we performed a sequential ChIP experiment (Fig. 6B), in which chromatin complexes precipitated with the PR antibody were then precipitated with either a GATA-2 antibody or no antibody at all. The results clearly confirm that PR and GATA-2 are concomitantly bound to FKBP5 intronic chromatin. To explore the possibility that PR and GATA-2 physically associate before DNA binding, we performed coimmunoprecipitation assays (co-IPs) but were unable to demonstrate an interaction between them (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Simultaneous binding of GATA-2 and PR on the intronic PRE. A, Chromatin was prepared from 3017.1 cells treated with R5020 for 15 min and immunoprecipitated with antibodies against GATA-2 (α-GATA2) or PR (α-PR). B, Chromatin was prepared from 3017.1 cells treated with R5020 for 1 h and immunoprecipitated with an antibody against the PR. The eluted immunocomplexes were used in a second ChIP with an antibody against GATA-2 or no antibody (No Ab). Purified DNA was amplified with primers spanning the PRE or a control region located 5 kb upstream of the TSS. Ab, Antibody.

Communication between the Intronic PRE and the promoter

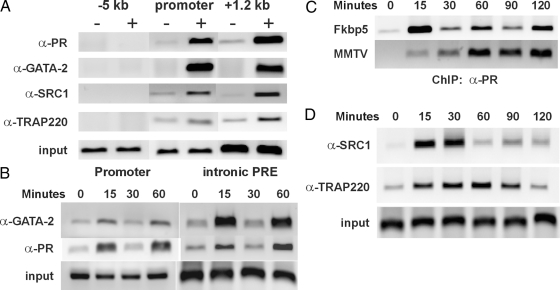

Our ChIP scanning assay had shown loading of the PR not only on the intronic PRE but on the proximal promoter as well (Fig. 2B). In silico analysis (Fig. 2A) and transfections with deletion constructs (Fig. 3) proved that the proximal promoter does not contain PREs or other sequences that are essential for progestin responsiveness; therefore, we hypothesize that the intronic region comes in close proximity to the promoter region upon progestin exposure. If so, PR and GATA-2 may be detected at both genomic segments, even if they are directly bound to intronic DNA, due to the formaldehyde cross-linking that precedes the ChIP assay. Therefore, we performed ChIPs using primers for both the intronic and the promoter region and antibodies against PR, GATA-2, steroid receptor coactivator (SRC)-1, a well-known coactivator of PR, and thyroid hormone receptor-associated protein (TRAP)220, a component of the mediator complex that is known to interact with nuclear receptors and facilitate their communication with the basal transcription machinery (36). Our results showed R5020-inducible association of all four proteins with the downstream, composite PRE region as well as the proximal promoter (Fig. 7A). As a negative control we assayed a region 5 kb upstream of the TSS. None of these factors associated with this region. These results indicate that the two regions interact in some way during PR-mediated transcription of the mouse FKBP5 gene. It should also be noted that the PR associates with both the human FKBP5 TSS region and intronic PRE in a ligand-dependent fashion (supplemental Fig. 2B), indicating some mechanistic similarity between progestin activation of the mouse and human genes.

Figure 7.

Dynamics of PR transcription complex assembly on the intronic PRE. Chromatin was prepared from 3017.1 cells untreated or treated with R5020 for various times and immunoprecipitated with antibodies against PRB, GATA-2, SRC-1, or TRAP220, as shown. Purified DNA was amplified using primers that span various regions of the FKBP5 gene or the MMTV promoter. Results from one representative experiment are shown. All ChIP assays were repeated at least twice with similar results. A, Communication of the promoter with the intronic PRE (+1.2 kb) as shown by the recruitment of PR, GATA-2, SRC-1, and TRAP220 on both genomic fragments 15 min after R5020 treatment. The primers used to detect promoter sequences were the same used to detect PR binding to the region centered around −300 bp in Fig. 2, and those used to detect the intronic PRE were the same as those used to detect PR binding centered around +1200 bp (listed in Table 2). B, Cyclical recruitment of GATA-2 and PR on the promoter and on the intronic PRE after R5020 addition. C, The cyclic recruitment of PR is a gene-specific phenomenon, because the association of the receptor with the MMTV promoter appears to be constant for up to 2 h after R5020 treatment. D, Kinetic analysis of the recruitment of SRC-1 and TRAP220 to the intronic PRE.

Cyclic recruitment of PR, GATA-2, and coactivators on the intronic PRE

Other steroid receptors and their coactivators have been shown to cycle on and off target promoters. We carried out ChIP assays to kinetically monitor association of the various factors with the Fkbp gene. The results of Fig. 7B show that both PR and GATA-2 have a cyclic association with the intronic PRE of the FKBP5 gene. In fact, they cycle on and off the promoter with the same periodicity, further supporting the idea of a direct interaction between the promoter and intron. To establish whether the cycling of the receptor is a gene-specific effect, which may be determined by the nature of the PRE, we compared the kinetics of PR binding at the FKBP5 and MMTV promoters for a longer time course (Fig. 7C). For up to 2 h after hormonal treatment, the PR continually cycled on and off the Fkbp 5 intronic PRE with a periodicity of 30 min after the initial loading at 15–20 min post-R5020 exposure. In contrast, recruitment of the receptor to the MMTV promoter was persistent rather than cyclic in nature. Thus, the periodic association of steroid receptors may be a gene-specific event, rather than an inherent feature of the receptors. To define the temporal recruitment of PR coactivators on the intronic PRE, we performed an extended time-course analysis using ChIP assay, as shown in Fig. 7D. Interestingly, SRC-1 and TRAP220 are loaded shortly after hormonal treatment but follow different patterns of recruitment and release. SRC-1 peaks at 30 min and then dissociates and starts a new cycle of recruitment 60 min later, whereas TRAP220 persists for up to 90 min and is then cleared from the gene.

Discussion

Emerging evidence of an important role for PR in mammary tumorigenesis makes it a priority to investigate the array of mechanisms that PR and related cofactors employ to regulate gene expression in this cellular context. Comprehensive knowledge of the mechanisms through which PR exerts its actions is the key to understanding progesterone effects in normal and cancerous mammary cells. We have addressed this critical issue, under biologically relevant conditions, by studying the progestin induction of FKBP5 in mouse mammary adenocarcinoma cells. Our findings reveal a novel mechanism employed by PR to regulate gene expression through a composite response element located downstream of the TSS in the first intron. At this composite element the PR binds DNA but also makes protein-protein interactions essential for activation. The likely target of these interactions is GATA-2, which co-occupies the element with the PR and is also essential for progestin responsiveness of the gene. These factors also contact the proximal promoter and associate with both intron and promoter in a cyclic fashion. These results expand our current knowledge on PR-mediated transcription, which has been largely based on studies with promoters containing classical PREs upstream of the TSS.

In the current study we took three approaches to identify PR-binding regions in the FKBP5 gene. First, our in silico analyses identified a long CpG island extending from the TSS to approximately 1.2 kb downstream, suggesting that the first exon/intron region may contain regulatory elements (37), as well as several potential PREs in a fragment extending from −5 kb to +2 kb (Fig. 2A). Second, we scanned the same fragment by ChIP assay using an antibody against the PR (Fig. 2B). These experiments demonstrated progestin-inducible receptor occupancy of two regions, one located in the proximal promoter and the other in the first intron, approximately 1.2 kb downstream of the TSS. Finally, transient transfection experiments with a series of deleted constructs of the murine FKBP5 gene showed that the region that mediates PR responsiveness is the intronic one. Using site-directed mutagenesis we identified a functional PRE that, according to in silico analysis, appeared to be conserved in the first intron of the human long isoform of FKBP5. We cloned this region and found it to confer progestin responsiveness to a core promoter. In addition, we found by ChIP assay that PR strongly associated with this region in a progestin-dependent fashion (supplemental Figs. 1 and 2). Thus, both the mouse and human FKBP5 genes contain an intronic PRE.

The human FKBP5 gene has been reported to be up-regulated by glucocorticoids (19), androgens (21), and progestins (13) in different cell lines, but there is conflicting data about the mechanisms that mediate its regulation by steroids. Previously, it was reported that regulation of progestin and glucocorticoid was mediated through the proximal promoter (22), albeit rather weakly; later, the same group identified potential HREs 65 kb downstream of the FKBP5 TSS, and showed, using in vitro assays with synthetic gene constructs, that they are responsive to glucocorticoids and progestins, but not androgens (38). However, a later study, using an in vivo approach, proved that, in the tissues examined, the AR occupies this distal enhancer, but not the GR (39). The authors emphasized the importance of confirming in vitro hypotheses in an in vivo setting. We agree with this assessment, because, in the course of our ChIP experiments, we did not observe any PR binding at the distal enhancer (∼+65 kb) in 3017.1 cells (data not shown). Thus, our study has revealed a previously uncharacterized HRE in the FKBP5 gene. The choice of elements used may be specific to receptor or cell type.

For the last two decades the traditional view has been that steroid receptors bind to their cognate response elements, in the proximal promoter or a few kilobases upstream of the TSS, and regulate transcription of their target genes. A first new insight that invokes revision of the classical model comes from genome-wide analyses of steroid receptor binding sites (Refs. 7,8,9; and John, S., and G. L. Hager, personal communication) that reveal that only 4–9% of HREs are actually located in the promoter, whereas 35–45% of them are located in introns. Thus, our results showing the intronic location of a PRE regulating the expression of FKBP5 fit well with the new, emerging model about gene regulation by steroid receptors. Furthermore, steroid receptor-binding sites are often enriched in motifs for the binding of other transcription factors, suggesting that most HREs are composite in nature, at which the receptor synergizes with other factor(s) to efficiently drive gene expression. For example, ER binding sites on chromosomes 21 and 22 were found enriched in Forkhead sites, and the authors experimentally verified that FoxA1 is essential for ER binding, as well as ER-mediated gene transcription (12). So et al. (8) reported enrichment of glucocorticoid response elements with activator protein 1 (AP1)and CCAAT enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP) sites, two factors previously shown to be crucial for GR gene regulation (10,11).

Even though genome-wide mapping of PR-binding sites has not been reported, it is logical to predict similar findings for this receptor as well. Our data, on a single-gene level, support this prediction. In the course of our experiments, we identified a GATA-binding site close to the PRE in the mouse FKBP5 gene that, when mutated, abolished progestin responsiveness of FKBP5 reporter constructs (Fig. 4B). We identified GATA-2 as the factor that binds to this site (Fig. 6). This transcription factor was originally identified as a master activator in hematopoietic cells during differentiation (40); however, it is now known to be expressed in a wide variety of tissues (41,42,43,44,45). A time-course ChIP analysis showed that the dynamics of GATA-2 occupancy on the intronic PRE resemble those of the PR (Fig. 7B), and a sequential ChIP experiment confirmed that the two factors co-occupy the PRE region (Fig. 6B). Interestingly enough, a DNA-binding mutant of hPRB was able to transactivate the FKBP5 promoter, but not the MMTV promoter, which is strictly dependent on direct binding of the PR to DNA (Fig. 5). However, the mutant did not activate the FKBP5 gene as efficiently as the wild-type PR. In addition, mutation of the PR-binding site in the composite element did not eliminate progestin responsiveness of the FKBP5 gene. Together these results show that PR contacts the FKBP5 gene through both DNA and protein-protein interactions and support the contention that PR responsiveness is mediated through a composite element rather than a simple PRE. Given the concomitant presence of both PR and GATA-2 on the PRE and the loss of progestin induction when the GATA site is mutated, we speculate that the two factors form a stabilized complex that can tether PR to chromatin, even when its DNA-binding capability is impaired. We were unable to demonstrate physical interaction between GATA-2 and PR in cellular extracts with co-IPs (data not shown); it is thus possible that stable association occurs in the context of the composite element.

Mutation of the GATA site leads to a complete loss of PR responsiveness, even when the PR-binding site remains intact (Fig. 4B), suggesting a primary role for GATA-2 in the regulation of the gene. In recent years a growing number of studies show a functional relationship between steroid receptors and members of the GATA family. GATA-3 is required for normal mammary gland development (46,47), and its expression is highly correlated with estrogen receptor α (ERα) in human breast tumors (48,49). Genome-wide analyses of ER-binding sites and ChIP experiments in breast cancer cells have shown that these sites are enriched in GATA-3-binding sites (7). Recently, the same group reported GATA-3 and ER to the same region of the ERα gene and, similar to our findings, did not observe a physical interaction between the two using co-IPs (50). While this manuscript was under preparation, the same group reported the mapping of AR-binding sites in chromosomes 21 and 22 in human prostate cancer cells (9). These sites were found enriched in GATA-2-binding sites, and the authors went on to show a functional relationship between AR and the GATA factor. They found that GATA-2 regulates androgen-dependent transcription and they proposed that it acts as a master activator in prostate cancer cells, where its role is to alter chromatin and make it accessible for AR binding (9). This model fits well with our data about PR and GATA-2 regulation of FKBP5. Still, the mechanism by which GATA-2 synergizes with steroid receptors remains undetermined. In fact, relatively little is known, in general, about the mechanisms of action of the GATA factors. Previous studies have found that other GATA factors can open compact chromatin (51), participate in the formation of DNA loops (52), and regulate chromatin conformation (53).

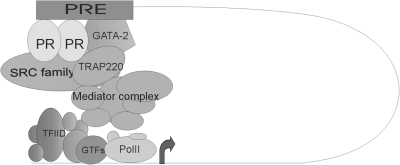

We speculate that the association of PR, GATA-2, and transcriptional cofactors SRC-1 and TRAP220 with both the intronic PRE and the FKBP5 promoter reflects the formation of a loop driven by protein-protein interactions. Based on the aforementioned studies (51,52,53), GATA-2 may have a role in stabilizing the loop that brings the two regulatory regions in close proximity and/or in altering the chromatin as to make it accessible to PR binding. In Fig. 8 we present a model in which PR, GATA-2, and their associated coregulators participate in a multiprotein complex that serves as the bridge that stabilizes the physical interaction between promoter and composite PRE. This model is in line with the results of several recent reports showing that ER bound to distant sites relative to the TSS of a target gene is able to induce loop formation to activate transcription (12,60,61).

Figure 8.

PR transcription complex assembly. After ligand activation, PR binds to a composite PRE in the first intron of the FKBP5 gene along with GATA-2. This regulatory region communicates with the promoter via DNA looping that is stabilized by a protein complex comprised of PR cofactors components of the mediator complex and, most likely, other transcription factors also. GTF, GATA transcription factor; PolII, polymerase II; TFIID, transcription factor IID.

SRC-1 is a well known coactivator of PR with an intrinsic histone acetyltransferase activity (reviewed in Ref. 54). TRAP220 is a component of the Mediator complex that anchors nuclear receptors to the basal transcriptional machinery (36) and has also been reported to interact with GATA-2 (45). The early recruitment of SRC-1 and TRAP220 (15 min after hormonal treatment) confirms their important role in receptor-mediated transcriptional activation and suggests that they facilitate the formation of the loop. However, our ChIPs also showed that SRC-1 and TRAP220 have kinetic patterns of association with the FKBP5 gene that are distinct from those of PR and GATA-2 (Fig. 7B). This observation suggests that other factors also participate in the protein complex that forms the loop and may be involved in maintaining it, even as PR and GATA-2 cycle on and off.

In recent years, the conventional view that receptors remain stably bound to their DNA response elements has been challenged. Kinetic analyses of promoter occupancy by steroid receptors have shown that the binding of the receptor to DNA is characterized by cycles of recruitment and release (23,24,25). Here, we report for the first time that PR is also capable of such a cyclical pattern of recruitment. In the course of 2 h, there are at least three cycles of sequential recruitment and release of the receptor on the FKBP5 PRE. It has been suggested that the continual cycling of nuclear receptors and their associated complexes on inducible promoters represents a way to monitor the environment, thus allowing tighter control of hormonally regulated gene expression (55). In contrast to FKBP5, ChIP assays showed that PR was persistently associated with the MMTV promoter (Fig. 7C). This may be due simply to the fact that the multiple copies of MMTV promoter in 3017.1 cells are out of synch and make cycling difficult to measure. Alternatively, it could be a promoter-specific property of receptor binding. The two promoters are fundamentally different in that the FKBP5 promoter produces mRNA as long as steroid is present (Fig. 1A), whereas the MMTV promoter is transiently activated; transcription declines even in the continued presence of steroid due to receptor-independent events (56). Thus, receptor cycling may not be necessary at the MMTV promoter to monitor the cellular hormonal environment.

In summary, we have identified and characterized a composite element for PR binding in the first intron of FKBP5. The receptor binds to DNA along with GATA-2 and forms a multiprotein complex that communicates with the promoter to induce transcription of the gene. We speculate that GATA-2 plays an essential role in bringing the two regulatory regions in close proximity via DNA looping. Given that most steroid receptor binding occurs in distal sites, such looping mechanisms seem to be an integral part of gene regulation by the receptors and should be investigated; it is likely that other, adjacently bound factors will facilitate this interaction. It will be interesting to determine in future studies whether the intronic element in the human gene is dependent on GATA factor binding given the presence of two PR-binding sites compared with the one present in the mouse element. As has been the case for the ER, a global analysis of PR-binding sites will provide additional insight into the role of the receptor in the genesis and promotion of breast cancer by revealing novel progesterone target genes, as well as accessory factors that are indispensable for long and short distance regulation. Although genome-wide approaches certainly provide valuable insights into mechanisms of steroid receptor action, they do not supplant the requirement to test, on a single-gene level, the functionality of binding sites and to dissect precise mechanisms by which various factors synergize to regulate gene expression, as was done in this study.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Antibodies used were purchased from the following manufacturers: α-PR (MA1-411) from Affinity Bioreagents, Inc. (Golden, CO); α-GATA-2 (H-116) (catalog no. sc-9008), α-GATA-3 (H-48) (catalog no. sc-9009), α-GATA-4 (C-20) (catalog no.sc-1237), α-SRC-1 (M-341) (catalog no. sc-8995), α-TRAP220 (S-19) (catalog no. sc-5335) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA); α-SRC-1 (clone 1135) from Upstate Biotechnology, Inc. (part of Millipore, Billerica, MA); α-RNA polymerase II (8WG16) from Covance Laboratories, Inc. (Madison, WI). A α-GATA-2 rabbit polyclonal antibody as well as G1E whole-cell extract (positive control for GATA-2 detection) were generous gifts from Dr. Emery H. Bresnick (University of Wisconsin, School of Medicine, Madison, WI). The DNA-binding mutant of the hPR was a kind gift from Drs. K. Horwitz and G. Takimoto (University of Colorado, Health Sciences Center, Denver, CO).

Cell culture

The cell line 3017.1 was derived from C127 mouse mammary adenocarcinoma cells and contains stable replicating copies of BPV-MMTV LTR fusions as well as stably expressed chicken PR (35). All cells, including Hela and T47D, were grown in DMEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and glutamine (Life Technologies), at 37 C under 5% CO2. When an experiment involved hormonal treatment, cells were plated in DMEM/charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum, either 24 h (RNA isolation, transfections) or 3 d (ChIP assays) before harvesting.

RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from the cells using the Trizol reagent (Invitrogen), and 2.5 μg of RNA was reverse transcribed using the SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. cDNA (1 μl) was amplified with the QIAGEN Taq polymerase following the manufacturer’s protocol (QIAGEN, Chatsworth, CA). A 28-cycle PCR was carried out for the amplification of a 747-bp FKBP5 fragment and a 19-cycle PCR was performed for the amplification of a 511-bp actin fragment. Both sets of primers had an annealing temperature of 58 C and their sequences were as follows: FKBP5 forward, 5′-CAAGGCCAGGTTATCAAAGC-3′; FKBP5 reverse, 5′-TCGGAGCTTCAGGTAGCACA-3′; actin forward, 5′-TGTGATGGTGGGAATGGGT-3′ and actin reverse, 5′-GATGTCACGCACGATTTC-3′.

Quantitative RT-PCR was carried out to analyze immunoprecipitated chromatin in studies with T47D cells. After purification, immunoprecipitated DNA was assayed for the presence of human FKBP5 gene sequences using the Maxima SYBR green qPCR master mix (Fermentas, Inc., Glen Burnie, MD) and an ABI 7000 qPCR machine (ABI Advanced Biotechnologies, Columbia, MD). Primers for the human long-form TSS region were as follows: forward, 5′-TCCCTCCGAGGAGGAAATCTTCA-3′; and reverse, 5′-AAAGAGGGACATAGGGCAAGAGGA-3′. Primers for the human intronic PRE region were as follows: forward, 5′-TAATAGAGGGGCGAGAAGGCAGA-3′; and reverse, 5′-GGTAAGTGGGTGTGCTCGCTCA-3′.

In silico analysis

The Genomatix software (57) was used to define the mouse FKBP5 promoter, align human and mouse sequences, and predict for transcription factor-binding sites. The TSS was annotated based on the Refseq NM_010220 and the database of TSSs (DBTSS) (58). Another program, called Tiger HRE Finder (29), which draws from a database of more than 650 validated SREs, was used to predict for de novo SREs. CpG islands were identified using the CpG island searcher (59). The sequence of the 7-kb fragment that was scanned for potential PREs was deduced by comparison between the genomic sequences NT_039649 (the contig that contains the gene) and AY113161 (GenBank entry of the promoter and the first noncoding exon of the gene).

Plasmid construction

Genomic DNA was isolated from 3017.1 cells and used as a template for PCRs using HotStarTaq polymerase (QIAGEN) and primers that contained restriction sites (Table 1). Individual PCR products were cloned into PCR2.1-TA vector (Invitrogen), sequenced in both directions, excised with appropriate restriction enzymes, and directionally subcloned into a promoterless pGL3-basic vector unmodified or modified as to contain a linker with the following restriction sites: KpnI, XbaI, MluI, XhoI, and BglII. The primers that were used are shown in Table 1, along with their binding sites relevant to the TSS and the length of the amplified fragment. The longest construct pGL3(−1455/+1244) was prepared with successive cloning of the fragments (−1455/−332) and (−340/+1244) into the same vector. Construct pGL3 (−334/+1029) was generated from the ligation of fragment (−334/+1029), previously excised from the cloned fragment (−340/+1244) with the enzymes MluI and DraI, into pGL3 digested with MluI and SmaI. Site-directed mutagenesis (as described below) was used to insert restriction sites in the pGL3(−334/+1029) plasmid to prepare deletion constructs of the promoter. DNA fragments were excised using appropriate enzymes and subcloned into pGL3-basic. The mutagenic oligonucleotides that were used for the generation of each construct are described in Table 1. Sequencing and restriction analysis confirmed mutagenized sites.

Table 1.

Primers used for preparation of constructs

| Primers | Amplified fragment (bp) | Sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| 1F (−1455 to −1428) | 1122 | cttttctCtagaggtctttgaggatagg |

| 2R (−332 to −353) | attacgcGtctgccttgcctgt | |

| 3F (−340 to −318) | 1585 | cagacgcGtgtctggtcagtatt |

| 4R (+1244 to +1220) | gaaacacactcGAgaaagaagaagaa |

| Mutagenic oligonucleotides | pGL3 construct generated | |

|---|---|---|

| 5F (−157/−127) | (−138/+1244) | gccaccaatcgggacgCgTggagcgacagcc |

| 6R | ggctgtcgctccAcGcgtcccgattggtggc | |

| 7F (−97 to −66) | (−78/+1244) | cccgtggccctatgggaCgCgTgtcctgcggc |

| 8R | gccgcaggacAcGcGtcccatagggccacggg | |

| 9F (−63 to −29) | (−47/+1244) | gggggcgggacgacgCGTggcgctgcccggcgc |

| 10R | gcgccgggcagcgccACGcgtcgtcccgccccc | |

| 11F (−30 to +1) | (−15/+1244) | gcactagcggctCgAgggcgctgccagtctc |

| 12R | gagactggcagcgcccTcGagccgctagtgc |

Primers are shown along with their binding sites relevant to the TSS and the length of the amplified fragment. Capitalized are depicted the nucleotides that were changed from the original sequence to generate restriction sites (underlined). F, Forward; R, reverse. For more details see Materials and Methods.

Cloning of the reporter containing the intronic PRE region from the human long isoform of the FKBP5 gene was carried out as follows. First, this region was amplified using PCR with primers containing sites for restriction enzymes at their 5′-ends. The amplified fragment contained the putative PR- and GATA-binding sites along with sequences on either side comprising a small CpG island. This was inserted into a luciferase reporter containing the MMTV core promoter from the TATA box to the initiator element.

Site-directed mutagenesis of PRE and GATA sites

The QuikChange II Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) was used for mutating individual sites according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The pGL3(−334/+1244) plasmid, containing the PR-responsive region of FKBP5, was used as a template. The potential PR-binding sites PRE1 and PRE2 (Fig. 5A) were mutated as follows (mutated nucleotides are shown capitalized): The oligonucleotides forward, 5′-ccatggcgaaagcgttggaaCgCGTagatcgtaagcagagcgtgc-3′, and reverse, 5′-gcacgctctgcttacgatctACGcGt tccaacgctttcgccatgg-3′, were used to mutate PRE1 and generate construct M1 (Fig. 5B). The first half-site of PRE2 was mutated by using the oligonulceotides: forward, 5′-ccctcggcggggcAcgCgT cagggtgtacagc-3′, and reverse, 5′-gctgtacaccctgAcGcg Tgccccgccgaggg-3′, generating construct M6 (Fig. 5B). The second half-site of PRE2 was mutated by using the oligonucleotides: forward, 5′-ggg ctcgggacagggAAAaca gcgcttggccgc-3′, and reverse, 5′-gcggccaagcgctg tTTTccctgtcccgagccc-3′, generating construct M7. Using the mutated construct M6 as a template, we also mutated the first A of the AGATC site (oligonucleotides described below) to generate construct M8 carrying double mutations in PRE2 and GATA sites (Fig. 5B). To generate a number of constructs with the GATA site (shown underlined) mutated at different positions, we used the oligonucleotides 5′-cgaaagcgttgga aggtacagatcgtaagcagagc-3′ and 5′-gctctgcttacgatctgtaccttccaacgctttcg-3′ mutated as follows: first A→C (construct M2), G→T (construct M3), AG→CT (construct M4), TC→GG (construct M5). Sequencing analysis confirmed mutagenized sites. Mutated DNA was transfected into HeLa and 3017.1 cells as described below.

Transfections

Progestin responsiveness of FKBP5 reporter constructs were tested in 3017.1 and HeLa cells with transient transfection assays. Cells were seeded in six-well plates and transfected with Superfect (3017.1) or Polyfect (HeLa) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (QIAGEN), using 1–2 μg of each FKBP5 construct. Hela cells were also transfected with pcPRO (chicken PR expression vector) for experiments with FKBP5 promoter deletions and mutations, or with expression vectors for wild-type hPR or a DNA-binding mutant (kind gift from Dr. Kathryn Horwitz, University of Colorado Health Sciences Center). pCMV-β-galactosidase was used as an internal control. T47D cells were transfected by electroporation using a Squareporator (Harvard Apparatus, Inc., South Natick, MA). Cells were treated with EtOH or 30 nm R5020 and harvested 24 h later. Cell lysis was achieved by three cycles of freezing and thawing, and cell extracts were assayed for luciferase and β-galactosidase (Galacto-Light kit; Tropix, Inc., Bedford, MA) activity. All transfections were done in duplicate at least three times.

ChIPs

ChIPs were performed with modifications of the procedure described by Metivier et al. (25), using 2 × 107 cells cultured for 3 d in DMEM/charcoal-treated fetal calf serum cells and then treated with 30 nm R5020. Before cross-linking, media without serum were added to the cells followed by formaldehyde to a final concentration of 1%. Fixation proceeded for 10 min at 37 C and was stopped by the addition of glycine to a final concentration of 0.125 m. Cells were placed on ice for 5 min and rinsed twice with ice-cold PBS. Cells were than scraped from the plates, collected by centrifugation, and resuspended in lysis buffer [50 mm Tris/HCl (pH 8), 10 mm EDTA, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)]. After 10 min incubation on ice, nuclei were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in lysis buffer. Chromatin solution was generated through sonication five times for 10 sec with 1 min cooling between pulses using a Misonix sonicator. Samples were centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 15 min. After centrifugation, 60 μl of the supernatants was saved to be used as input, and the remainder was diluted in ChIP dilution buffer (1.2 mm EDTA; 167 mm NaCl; 16.7 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8; 1.1% Triton X-100; and 0.01% SDS). After preclearing for 2 h at 4 C with salmon sperm DNA/Protein A+G agarose beads (Upstate Biotechnology), 10 μg of each antibody was added to the precleared, diluted chromatin solution, which was then rotated overnight at 4 C. Complexes were recovered by incubation for 3 h at 4 C with salmon sperm DNA/Protein A+G agarose beads. Precipitates were serially washed with 1 ml of each of the following buffers for 10 min with rotation at 4 C: washing buffer I (2 mm EDTA; 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0; 0.1% SDS; 1% Triton X-100; 150 mm NaCl), washing buffer II (2 mm EDTA; 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0; 0.1% SDS; 1% Triton X-100; 500 mm NaCl), washing buffer III (1 mm EDTA; 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0; 1% Nonidet P-40; 1% Deoxycholate; 0.25 m LiCl) and then twice with 1 mm EDTA, 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0. Precipitated chromatin complexes were removed from the beads through two 15-min incubations with 100 μl of 1% SDS, 0.1 m NaHCO3. All buffers contained 1× protease inhibitors cocktail (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA). Cross-linking was reversed by an overnight incubation at 65 C, and the samples were incubated with proteinase K at 45 C for 2 h. DNA was extracted with phenol-chloroform and precipitated with the addition of EtOH overnight at −20 C. Samples were analyzed by 28 cycles of PCR, using HotStar Taq DNA polymerase and the primers listed in Table 2. For sequential ChIPs, 3017.1 cells were treated with R5020 for 1 h, and chromatin was prepared, as described above, and was immunoprecipitated with an antibody against the PR. The eluted immunocomplexes were used in a second ChIP with an antibody against GATA-2.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. G. L. Hager, E. Soutoglou and S. John (Laboratory of Receptor Biology and Gene Expression, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health), for their support, helpful discussions, and critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Ms. Lucina Lizarraga Zazueta and Ms. Erin Acino for excellent technical assistance. We also thank Dr. E. H. Bresnick (University of Wisconsin, School of Medicine, Madison, WI) for providing the α-GATA-2 rabbit polyclonal antibody and Drs. K. Horwitz and G. Takimoto (University of Colorado, Health Sciences Center, Denver, CO) for the DNA-binding mutant of the hPR.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online November 26, 2008

Abbreviations: AR, Androgen receptor; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; co-IP, coimmunoprecipitation assay; ER, estrogen receptor; ERE, estrogen response element; GR, glucocorticoid receptor; HRE, hormone response element; MMTV, mouse mammary tumor virus; MR, mineralocorticoid receptor; PR, progesterone receptor; PRB, B isoform of PR; PRE, progesterone response element; SDS, sodium dodecyl sulfate; SRC, steroid receptor coactivator; SRE, steroid hormone respone element; TRAP, thyroid hormone receptor-associated protein; TSS, transcription start site.

References

- Graham JD, Clarke CL 1997 Physiological action of progesterone in target tissues. Endocr Rev 18:502–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail PM, Amato P, Soyal SM, DeMayo FJ, Conneely OM, O'Malley BW, Lydon JP 2003 Progesterone involvement in breast development and tumorigenesis—as revealed by progesterone receptor “knockout” and “knockin” mouse models. Steroids 68:779–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML, Jackson RD, Beresford SA, Howard BV, Johnson KC, Kotchen JM, Ockene J 2002 Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 288:321–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Katiyar P, Jones LP, Fan S, Zhang Y, Furth PA, Rosen EM 2006 The breast cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1 regulates progesterone receptor signaling in mammary epithelial cells. Mol Endocrinol 20:14–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole AJ, Li Y, Kim Y, Lin SC, Lee WH, Lee EY 2006 Prevention of Brca1-mediated mammary tumorigenesis in mice by a progesterone antagonist. Science 314:1467–1470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards DP 2000 The role of coactivators and corepressors in the biology and mechanism of action of steroid hormone receptors. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 5:307–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll JS, Meyer CA, Song J, Li W, Geistlinger TR, Eeckhoute J, Brodsky AS, Keeton EK, Fertuck KC, Hall GF, Wang Q, Bekiranov S, Sementchenko V, Fox EA, Silver PA, Gingeras TR, Liu XS, Brown M 2006 Genome-wide analysis of estrogen receptor binding sites. Nat Genet 38:1289–1297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So AY, Chaivorapol C, Bolton EC, Li H, Yamamoto KR 2007 Determinants of cell- and gene-specific transcriptional regulation by the glucocorticoid receptor. PLoS Genet 3:e94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Li W, Liu XS, Carroll JS, Janne OA, Keeton EK, Chinnaiyan AM, Pienta KJ, Brown M 2007 A hierarchical network of transcription factors governs androgen receptor-dependent prostate cancer growth. Mol Cell 27:380–392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann E, Dittrich-Breiholz O, Holtmann H, Kracht M 2002 Multiple control of interleukin-8 gene expression. J Leukoc Biol 72:847–855 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund A, Jolivel V, Durand S, Kersual N, Chalbos D, Chavey C, Vignon F, Lazennec G 2004 Mechanisms underlying differential expression of interleukin-8 in breast cancer cells. Oncogene 23:6105–6114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll JS, Liu XS, Brodsky AS, Li W, Meyer CA, Szary AJ, Eeckhoute J, Shao W, Hestermann EV, Geistlinger TR, Fox EA, Silver PA, Brown M 2005 Chromosome-wide mapping of estrogen receptor binding reveals long-range regulation requiring the forkhead protein FoxA1. Cell 122:33–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kester HA, van der Leede BM, van der Saag PT, van der Burg B 1997 Novel progesterone target genes identified by an improved differential display technique suggest that progestin-induced growth inhibition of breast cancer cells coincides with enhancement of differentiation. J Biol Chem 272:16637–16643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richer JK, Jacobsen BM, Manning NG, Abel MG, Wolf DM, Horwitz KB 2002 Differential gene regulation by the two progesterone receptor isoforms in human breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem 277:5209–5218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan Y, Nordeen SK 2002 Overlapping but distinct gene regulation profiles by glucocorticoids and progestins in human breast cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol 16:1204–1214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez S, Beato M 1997 Nucleosome-mediated synergism between transcription factors on the mouse mammary tumor virus promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:2885–2890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher TM, Ryu BW, Baumann CT, Warren BS, Fragoso G, John S, Hager GL 2000 Structure and dynamic properties of a glucocorticoid receptor-induced chromatin transition. Mol Cell Biol 20:6466–6475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayasam GV, Elbi C, Walker DA, Wolford R, Fletcher TM, Edwards DP, Hager GL 2005 Ligand-specific dynamics of the progesterone receptor in living cells and during chromatin remodeling in vitro. Mol Cell Biol 25:2406–2418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baughman G, Wiederrecht GJ, Campbell NF, Martin MM, Bourgeois S 1995 FKBP51, a novel T-cell-specific immunophilin capable of calcineurin inhibition. Mol Cell Biol 15:4395–4402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair SC, Rimerman RA, Toran EJ, Chen S, Prapapanich V, Butts RN, Smith DF 1997 Molecular cloning of human FKBP51 and comparisons of immunophilin interactions with Hsp90 and progesterone receptor. Mol Cell Biol 17:594–603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amler LC, Agus DB, LeDuc C, Sapinoso ML, Fox WD, Kern S, Lee D, Wang V, Leysens M, Higgins B, Martin J, Gerald W, Dracopoli N, Cordon-Cardo C, Scher HI, Hampton GM 2000 Dysregulated expression of androgen-responsive and nonresponsive genes in the androgen-independent prostate cancer xenograft model CWR22–R1. Cancer Res 60:6134–6141 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubler TR, Denny WB, Valentine DL, Cheung-Flynn J, Smith DF, Scammell JG 2003 The FK506-binding immunophilin FKBP51 is transcriptionally regulated by progestin and attenuates progestin responsiveness. Endocrinology 144:2380–2387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang Y, Hu X, DiRenzo J, Lazar MA, Brown M 2000 Cofactor dynamics and sufficiency in estrogen receptor-regulated transcription. Cell 103:843–852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Z, Pirskanen A, Janne OA, Palvimo JJ 2002 Involvement of proteasome in the dynamic assembly of the androgen receptor transcription complex. J Biol Chem 277:48366–48371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metivier R, Penot G, Hubner MR, Reid G, Brand H, Kos M, Gannon F 2003 Estrogen receptor-α directs ordered, cyclical, and combinatorial recruitment of cofactors on a natural target promoter. Cell 115:751–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen GI, Richer JK, Tung L, Takimoto G, Horwitz KB 1998 Progesterone regulates transcription of the p21(WAF1) cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor gene through Sp1 and CBP/p300. J Biol Chem 273:10696–10701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JC, Derynck MK, Nonaka DF, Khodabakhsh DB, Haqq C, Yamamoto KR 2004 Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) scanning identifies primary glucocorticoid receptor target genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:15603–15608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordeen SK, Suh BJ, Kuhnel B, Hutchison CD 1990 Structural determinants of a glucocorticoid receptor recognition element. Mol Endocrinol 4:1866–1873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepanova M, Lin F, Lin VC 2006 Establishing a statistic model for recognition of steroid hormone response elements. Comput Biol Chem 30:339–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelin A, Alkema W, Engstrom P, Wasserman WW, Lenhard B 2004 JASPAR: an open-access database for eukaryotic transcription factor binding profiles. Nucleic Acids Res 32:D91–D94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko LJ, Engel JD 1993 DNA-binding specificities of the GATA transcription factor family. Mol Cell Biol 13:4011–4022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartzbauer G, Schlesinger K, Evans T 1992 Interaction of the erythroid transcription factor cGATA-1 with a critical auto-regulatory element. Nucleic Acids Res 20:4429–4436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takimoto GS, Tasset DM, Eppert AC, Horwitz KB 1992 Hormone-induced progesterone receptor phosphorylation consists of sequential DNA-independent and DNA-dependent stages: analysis with zinc finger mutants and the progesterone antagonist ZK98299. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89:3050–3054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre P, Berard DS, Cordingley MG, Hager GL 1991 Two regions of the mouse mammary tumor virus long terminal repeat regulate the activity of its promoter in mammary cell lines. Mol Cell Biol 11:2529–2537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CL, Archer TK, Hamlin-Green G, Hager GL 1993 Newly expressed progesterone receptor cannot activate stable, replicated mouse mammary tumor virus templates but acquires transactivation potential upon continuous expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90:11202–11206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan CX, Ito M, Fondell JD, Fu ZY, Roeder RG 1998 The TRAP220 component of a thyroid hormone receptor-associated protein (TRAP) coactivator complex interacts directly with nuclear receptors in a ligand-dependent fashion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:7939–7944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner-Garden M, Frommer M 1987 CpG islands in vertebrate genomes. J Mol Biol 196:261–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubler TR, Scammell JG 2004 Intronic hormone response elements mediate regulation of FKBP5 by progestins and glucocorticoids. Cell Stress Chaperones 9:243–252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee JA, Chang LW, Stormo GD, Milbrandt J 2006 Direct, androgen receptor-mediated regulation of the FKBP5 gene via a distal enhancer element. Endocrinology 147:590–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai FY, Keller G, Kuo FC, Weiss M, Chen J, Rosenblatt M, Alt FW, Orkin SH 1994 An early haematopoietic defect in mice lacking the transcription factor GATA-2. Nature 371:221–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorfman DM, Wilson DB, Bruns GA, Orkin SH 1992 Human transcription factor GATA-2. Evidence for regulation of preproendothelin-1 gene expression in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 267:1279–1285 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jippo T, Mizuno H, Xu Z, Nomura S, Yamamoto M, Kitamura Y 1996 Abundant expression of transcription factor GATA-2 in proliferating but not in differentiated mast cells in tissues of mice: demonstration by in situ hybridization. Blood 87:993–998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma GT, Roth ME, Groskopf JC, Tsai FY, Orkin SH, Grosveld F, Engel JD, Linzer DI 1997 GATA-2 and GATA-3 regulate trophoblast-specific gene expression in vivo. Development 124:907–914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umeoka K, Sanno N, Osamura RY, Teramoto A 2002 Expression of GATA-2 in human pituitary adenomas. Mod Pathol 15:11–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon DF, Tucker EA, Tundwal K, Hall H, Wood WM, Ridgway EC 2006 MED220/thyroid receptor-associated protein 220 functions as a transcriptional coactivator with Pit-1 and GATA-2 on the thyrotropin-β promoter in thyrotropes. Mol Endocrinol 20:1073–1089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouros-Mehr H, Slorach EM, Sternlicht MD, Werb Z 2006 GATA-3 maintains the differentiation of the luminal cell fate in the mammary gland. Cell 127:1041–1055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asselin-Labat ML, Sutherland KD, Barker H, Thomas R, Shackleton M, Forrest NC, Hartley L, Robb L, Grosveld FG, van der Wees J, Lindeman GJ, Visvader JE 2007 Gata-3 is an essential regulator of mammary-gland morphogenesis and luminal-cell differentiation. Nat Cell Biol 9:201–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoch RV, Thompson DA, Baker RJ, Weigel RJ 1999 GATA-3 is expressed in association with estrogen receptor in breast cancer. Int J Cancer 84:122–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh P, Palazzo JP, Rose LJ, Daskalakis C, Weigel RJ 2005 GATA-3 expression as a predictor of hormone response in breast cancer. J Am Coll Surg 200:705–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eeckhoute J, Keeton EK, Lupien M, Krum SA, Carroll JS, Brown M 2007 Positive cross-regulatory loop ties GATA-3 to estrogen receptor α expression in breast cancer. Cancer Res 67:6477–6483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirillo LA, Lin FR, Cuesta I, Friedman D, Jarnik M, Zaret KS 2002 Opening of compacted chromatin by early developmental transcription factors HNF3 (FoxA) and GATA-4. Mol Cell 9:279–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vakoc CR, Letting DL, Gheldof N, Sawado T, Bender MA, Groudine M, Weiss MJ, Dekker J, Blobel GA 2005 Proximity among distant regulatory elements at the β-globin locus requires GATA-1 and FOG-1. Mol Cell 17:453–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spilianakis CG, Flavell RA 2004 Long-range intrachromosomal interactions in the T helper type 2 cytokine locus. Nat Immunol 5:1017–1027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perissi V, Rosenfeld MG 2005 Controlling nuclear receptors: the circular logic of cofactor cycles. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6:542–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowan BG, O'Malley BW 2000 Progesterone receptor coactivators. Steroids 65:545–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CL, Wolford RG, O'Neill TB, Hager GL 2000 Characterization of transiently and constitutively expressed progesterone receptors: evidence for two functional states. Mol Endocrinol. 14:956–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartharius K, Frech K, Grote K, Klocke B, Haltmeier M, Klingenhoff A, Frisch M, Bayerlein M, Werner T 2005 MatInspector and beyond: promoter analysis based on transcription factor binding sites. Bioinformatics 21:2933–2942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Yamashita R, Sugano S, Nakai K 2004 DBTSS, DataBase of Transcriptional Start Sites: progress report 2004. Nucleic Acids Res 32:D78–D81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takai D, Jones PA 2003 The CpG island searcher: a new WWW resource. In Silico Biol 3:235–240 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan YF, Wansa KD, Liu MH, Zhao B, Hong SZ, Tan PY, Lim KS, Borque G, Liu ET, Cheung E 2008 Regulation of estrogen receptor-mediated long-range transcription via evolutionarily conserved distal response elements. J Biol Chem 283:32977–32988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett DH, Sheng S, Charn TH, Waheed A, Sly WS, Lin CY, Liu ET, Katzenellenbogen BS 2008 Estrogen receptor regulation of carbonic anhydrase XII through a distal enhancer in breast cancer. Cancer Res 68:3505–3515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.