Abstract

GnRH is the main modulator of LH secretion and transcription of the LH subunit genes in pituitary gonadotropes. The LHβ gene is preferentially transcribed during pulsatile GnRH stimuli of one pulse/30 min and is thus carefully controlled by specific signaling pathways and transcription factors. We now show that GnRH-stimulated LHβ transcription is also influenced by the ubiquitin-proteasome system. GnRH-stimulated activity of an LHβ reporter gene was prevented by proteasome inhibitors MG-132 and lactacystin. Inhibition was not rescued by overexpression of two key transcription factors for LHβ, early growth response-1 (Egr-1) and steroidogenic factor-1 (SF-1). Increased endogenous LHβ transcription after GnRH treatment was also prevented by MG-132, as measured by primary transcript assays. To investigate possible mechanisms of LHβ transcriptional inhibition by proteasome blockade, we employed chromatin immunoprecipitation to measure LHβ promoter occupancy by transcription factors. Without GnRH, binding was low and unorganized. With GnRH, Egr-1 and SF-1 associations were stimulated, cyclic, and coincidental, with a period of approximately 30 min. MG-132 disrupted GnRH-induced Egr-1 and SF-1 binding and prevented phosphorylated RNA polymerase II association with the LHβ promoter. Egr-1, but not SF-1, protein was induced by GnRH and accumulated with MG-132. Egr-1 and SF-1 were ubiquitinated in gonadotropes and ubiquitinated forms of these factors associated with the LHβ promoter, suggesting their degradation may be key for LHβ proteasome-dependent transcription. Together, these results demonstrate that degradation via the proteasome is vital to GnRH-stimulated LHβ expression, and this occurs in part by allowing proper transcription factor associations with the LHβ promoter.

Proteasome activity is required for GnRH-stimulated LHβ transcription and cyclic promoter occupancy by Egr-1 and SF-1, two targets of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in gonadotropes.

The surge of LH from the anterior pituitary before ovulation is absolutely required for fertility. Pituitary gonadotrope cells synthesize and secrete LH in response to hypothalamic GnRH pulses (1). LH is a glycoprotein composed of two subunits, the common α-glycoprotein and the LH β-subunit (LHβ); each are transcribed from separate and independently controlled genes (1). In vivo, the GnRH signal must be pulsatile to stimulate both LHβ transcription and LH secretion (2,3,4). The LHβ gene responds preferentially to a GnRH pulse frequency of one pulse/30 min; however, the mechanisms of this specificity are still unclear and likely depend on multiple coordinated intracellular signals. GnRH promotes LHβ expression through protein kinase C (PKC), calcium influx, Ca/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase-II (Ca/CAMKII), and Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) (5,6,7,8). These pathways are known to impact protein synthesis in gonadotropes and may also regulate protein modification and degradation.

One of the most important events in GnRH stimulation of LHβ is the induction of early growth response-1 (Egr-1) synthesis. Egr-1 is an immediate early zinc-finger transcription factor normally present at low levels in gonadotropes, and GnRH, primarily via PKC, stimulates the Egr-1 gene and Egr-1 protein synthesis (9,10). Two Egr-1 binding sites exist on the rodent LHβ promoters, and mutation of either site results in a loss of basal expression and regulation by GnRH (11). Furthermore, Egr-1 knockout mice are infertile due to a specific lack of LHβ expression (12).

Egr-1 is thought to act cooperatively with other transcription factors and coactivators to enhance LHβ transcription. Steroidogenic factor-1 (SF-1) is an orphan nuclear receptor and key regulator of steroidogenic enzymes in many tissues, and it binds to the LHβ promoter at two sites (13). The two paired Egr-1/SF-1 sites, along with a homeodomain-transcription factor binding site form the proximal GnRH-response region on the LHβ promoter (14,15). In the rat, interaction between the proximal response region and a distal GnRH-response region comprised of two Sp1 sites and a CArG box can be mediated by the coactivator and E3 ubiquitin ligase small nuclear ring finger protein (SNURF) (16). The scaffold protein p300 is also implicated in LHβ transcription via interaction with SF-1 and Egr-1 (17), and β-catenin has been shown to accumulate in the nuclei of gonadotropes after GnRH treatment, where it can physically interact with SF-1 to modulate LHβ expression (18,19).

Binding of transcription factors to DNA is not a static event. Protein associations with promoters are influenced by hormonal stimulation and intracellular signaling pathway activity. For example, steroid hormone binding to nuclear receptors dramatically affects both the extent and pattern of their association with chromatin; similarly, phosphorylation of the transcription factor cAMP response element-binding protein by PKA greatly enhances its transcriptional activity (20,21,22). Ligand-bound estrogen receptor α (ERα) association with its target genes is characterized by cyclic binding with a period of about 45 min, and ERα coordinates cofactor recruitment and histone modification with similar cycles of association (20,21). Unliganded ERα also cycles on and off of DNA but with a faster period; without a hormonal signal, cofactors and RNA polymerase II are not recruited. Thus, gene expression is highly dependent on appropriate patterns of transcription factor occupancy, and it is likely that periodicity of binding is regulated at multiple levels in a transcription factor-specific manner.

One mechanism that may play a role in cyclic promoter associations by transcription factors is protein degradation via the proteasome. The proteasome is a group of proteases that function in an ATP-dependent fashion to degrade proteins covalently tagged with ubiquitin peptide chains (23). One hypothesis for proteasome-dependent transcription is that transcription factor degradation allows for promoter clearance for new rounds of transcription, ensuring continuous sensitivity to hormone levels (24). Indeed, the transcriptional activity of many nuclear receptors (ERα, androgen receptor, and thyroid hormone receptor) and nonreceptor transcription factors and coactivators [forkhead box O4 (FOXO4) and steroid receptor coactivator-3 (SRC-3)] is inherently linked to their degradation (20,25,26,27,28).

Ubiquitination of proteins is a highly regulated process that involves a series of three enzymes. The E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme prepares ubiquitin for ligation. E2s, or ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (ubc) transfer activated ubiquitin to the E3 ubiquitin ligase, which attaches ubiquitin molecules to lysine residues of target proteins (23). GnRH has been reported to increase levels of a specific E2 enzyme, ubc4, which also mediated the ubiquitination of ERα in gonadotropes (29). We now show that GnRH-mediated LHβ gene expression is dependent on protein degradation via the proteasome and that transcription factors Egr-1 and SF-1 are targets of the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Furthermore, proteasome activity is required for cyclic transcription factor associations with the LHβ promoter elicited by GnRH.

Results

Proteasome activity is required for GnRH stimulation of LHβ transcription

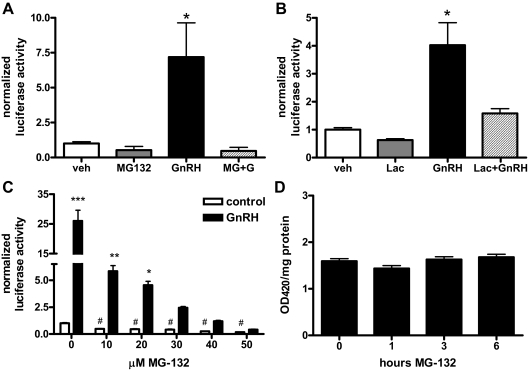

GnRH is the main stimulatory signal controlling LHβ gene expression. To assess the involvement of the ubiquitin-proteasome system in GnRH regulation of LHβ transcription, we used the peptide aldehyde MG-132 or the alternatively functioning inhibitor lactacystin to block proteasome activity in LβT2 gonadotrope cells. Lactacystin prevents degradation through a covalent link with the proteasome (30). In the absence of inhibitor, GnRH increased activity of a luciferase reporter gene driven by the rat LHβ promoter 4- to 7-fold (Fig. 1, A and B). This stimulation was completely eliminated when cells received MG-132 plus GnRH (Fig. 1A), or lactacystin plus GnRH (Fig. 1B), indicating a requirement for proteasome activity.

Figure 1.

GnRH stimulation of the rat LHβ promoter requires proteasome activity. A, LβT2 cells were transfected with a rat LHβ luciferase reporter and treated with 100 nm GnRH, 50 μm MG-132, or both (MG+G) for 6 h. *, P < 0.01 vs. vehicle control. B, LβT2 cells transfected with the rat LHβ reporter were treated with 100 nm GnRH with or without 10 μm lactacystin for 6 h. *, P < 0.01 vs. vehicle control. C, LβT2 cells were transfected as above with the rat LHβ reporter and treated with varying concentrations of MG-132 with or without 100 nm GnRH for 6 h. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 vs. matched controls; #, P < 0.001 vs. 0 μm MG control. D, LβT2 cells were transfected with a CMV-β-galactosidase reporter and treated with 50 μm MG-132 for times indicated; lysates were then assayed for β-galactosidase activity. Data are expressed as fold change vs. vehicle (veh); error bars reflect sem. Triplicate samples were analyzed for each of three experiments for A–D.

Loss of LHβ reporter activity was dependent on the dose of MG-132. Significant, but attenuated, GnRH stimulation was observed at 10 and 20 μm MG-132 but not at 30–50 μm (Fig. 1C). Because 50 μm MG-132 produced the most complete loss of GnRH-stimulated reporter activity, this dose was used in all other experiments. Basal LHβ reporter gene expression was also decreased by MG-132, with an approximate 50% decrease at the 10 μm dose and a 75% decrease with 50 μm.

To determine whether the effects of MG-132 were specific to LHβ, a cytomegalovirus (CMV)-driven β-galactosidase reporter was transfected into LβT2 cells, which were then treated with MG-132. Transcription of the β-galactosidase reporter was not affected by proteasome inhibition via MG-132 (Fig. 1D).

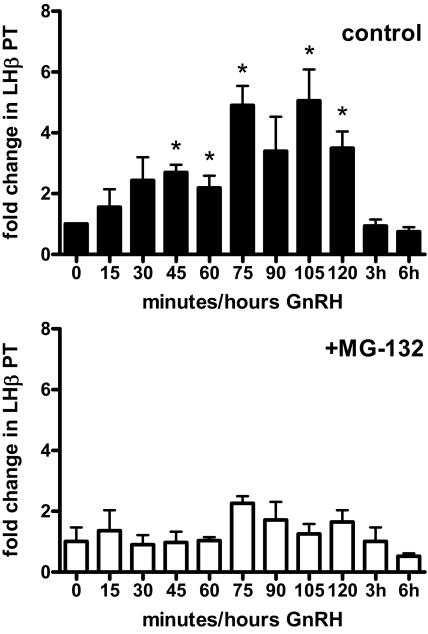

We next measured levels of LHβ primary transcript (PT) from LβT2 cells treated with a time course of GnRH with or without MG-132 to determine effects on endogenous LHβ expression. By performing quantitative real-time RT-PCR using primers spanning an intron/exon border of the mouse LHβ gene, amounts of newly synthesized LHβ mRNA were measured. We found that GnRH increased LHβ PT over time, with significant peaks at 45–75, 105, and 120 min GnRH (Fig. 2, top). PT levels returned to baseline by 3 h. Proteasome inhibition prevented significant stimulation of endogenous LHβ transcription by GnRH (Fig. 2, bottom). These results, together with the LHβ reporter assays, suggest protein degradation is critical to GnRH-stimulated transcription.

Figure 2.

GnRH-stimulated endogenous LHβ transcription is inhibited by MG-132. LβT2 cells were treated with 100 nm GnRH for times indicated, without (control, top) or with 50 μm MG-132 (+MG-132, bottom). LHβ PT were then measured using intron/exon-spanning primers and quantitative real-time PCR. Data are normalized to GAPDH mRNA levels and expressed as fold change vs. 0 min minus MG-132. Error bars reflect sem for triplicate samples in three experiments. *, P < 0.05 vs. control.

Loss of LHβ transcription during proteasome inhibition is not rescued by Egr-1 and SF-1 overexpression

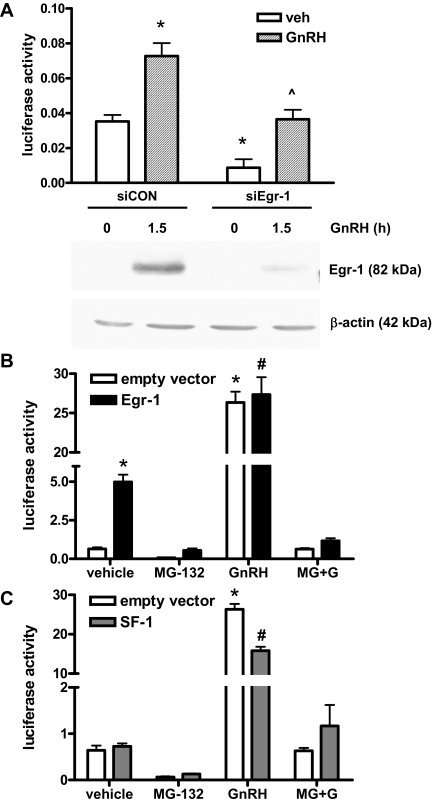

Many studies have identified Egr-1 as a key regulator of LHβ transcription. Knockout of Egr-1 in transgenic mice results in infertility due to a lack of LHβ protein (12), and mutation of the Egr-1 binding sites on the LHβ promoter greatly reduces its basal and stimulated activation (13,14,31). To further confirm the role of Egr-1 in LHβ transcription, we used small interfering RNA (siRNA) directed to mouse Egr-1 to reduce Egr-1 expression in LβT2 cells. This technique reduced Egr-1 protein levels in GnRH-stimulated cells by 65–70% (Fig. 3A). GnRH treatment increased activity of the LHβ luciferase reporter in cells transfected with a nonspecific control siRNA. In cells transfected with siEgr-1, both basal and GnRH-stimulated luciferase activity was significantly lowered, similar to previously reported results (32). Thus, levels of Egr-1 protein influence basal LHβ promoter activity and the overall GnRH response.

Figure 3.

Overexpression of Egr-1 or SF-1 cannot rescue loss of GnRH stimulation during proteasome inhibition. A, LβT2 cells were transfected with siRNA targeting Egr-1 or a nontargeting siRNA (siCON) and the rat LHβ luciferase reporter and then treated with 100 nm GnRH for 6 h (for luciferase assay) or 1.5 h (for Egr-1 immunoblotting). Immunoblots were also probed for β-actin expression for normalization. *, P < 0.05 vs. siCON vehicle; ^, P < 0.05 vs. siCON GnRH and siEgr-1 vehicle. B, LβT2 cells were cotransfected with the rat LHβ luciferase reporter and Egr-1 expression vector or empty vector and then treated with 100 nm GnRH for 6 h with or without 50 μm MG-132. *, P < 0.001 vs. vehicle with empty vector; #, P < 0.001 vs. vehicle with Egr-1. C, LβT2 cells were cotransfected with the rat LHβ luciferase reporter and SF-1 expression vector or empty vector and then treated with 100 nm GnRH for 6 h with or without 50 μm MG-132. *, P < 0.001 vs. vehicle with empty vector; #, P < 0.001 vs. vehicle with SF-1. For all panels, data are from triplicate samples from three experiments, expressed as arbitrary light units (ALU) per 100 μg protein and plotted as mean ± sem.

Both Egr-1 and SF-1 are involved in expression of LHβ in vivo, and binding sites on the LHβ promoter for these factors are well characterized, occurring at similar sites across several species (11,13,33). Because of the pivotal role these two proteins have in LHβ transcription, we tested whether overexpression of Egr-1 and/or SF-1 could overcome transcriptional inhibition during MG-132 treatment. CMV-driven expression vectors for Egr-1 and SF-1 were transfected into LβT2 cells with the rat LHβ luciferase reporter; after treatment, cell lysates were assayed for luciferase activity. Without Egr-1 or SF-1, GnRH increased transcription, and this was prevented by MG-132 (empty vector, Fig. 3, B and C). Egr-1 overexpression enhanced basal LHβ transcription 7.8-fold but did not further enhance fold GnRH stimulation, in accordance with previously published reports (13). However, GnRH was still unable to increase transcription in the presence of MG-132 with Egr-1 overexpression (Fig. 3B).

SF-1 had a less potent effect when overexpressed, increasing basal activity only 1.1-fold; again, no increase in luciferase activity was seen with MG-132 plus GnRH (Fig. 3C). Overexpression of Egr-1 and SF-1 together was also ineffective in rescuing the GnRH response of the rat LHβ luciferase reporter during MG-132 treatment (data not shown). Thus, despite increases in total transcription factor levels, LHβ transcription was still inhibited by MG-132, indicating protein turnover is a required step for GnRH-stimulated transcription.

GnRH coordinates rhythmic transcription factor associations with the LHβ promoter

To better understand the interplay between the ubiquitin-proteasome system and GnRH-stimulated transcription, we sought to determine patterns of transcription factor occupancy on the LHβ promoter in response to GnRH. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was used to identify changes in Egr-1 and SF-1 binding to the LHβ promoter in its endogenous chromatin environment. Real-time PCR with primers targeting the LHβ promoter (−102 to −1 bp) was used to quantify promoter occupancy. Data were then analyzed with the CLUSTER8 pulse detection algorithm, a statistically based program that detects peaks and nadirs in time series data (34).

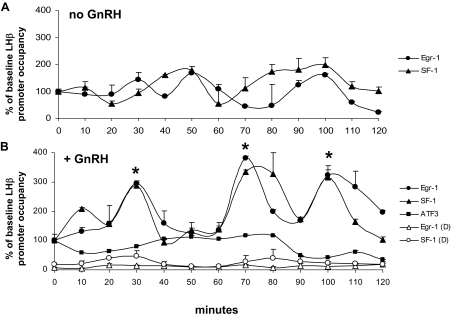

Without GnRH, no specific patterns of Egr-1 or SF-1 occupancy were observed, and associations of both proteins were generally low (Fig. 4A). However, in the presence of GnRH, we observed stimulated and cyclic association of both Egr-1 and SF-1, but not activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3), a transcription factor that has no defined binding sites on the LHβ promoter (Fig. 4B, closed symbols). Egr-1 and SF-1 binding was coordinated and had a period of approximately 30 min (mean peak interval for Egr-1 was 28.33 ± 3.1 min; 32.00 ± 2.0 min for SF-1). The degree of promoter occupancy fluctuated between experiments, but peaks of Egr-1 and SF-1 association were consistently synchronized with the same period of about 30 min. No specific LHβ promoter occupancy was measured without the addition of primary antibody (not shown). Real-time PCR using primers directed toward a distal upstream region of the LHβ gene that does not contain Egr-1 or SF-1 binding sites (−3268 to −3107 bp) (19) further demonstrated specificity of the assay (Fig. 4B, open symbols), with no protein binding observed.

Figure 4.

ChIP reveals cyclic occupancy of the LHβ promoter by Egr-1 and SF-1. A, Promoter occupancy was measured by ChIP and quantitative real-time PCR using primers for the LHβ promoter (−102 to −1 bp). LβT2 cells were pretreated with 2.5 μm α-amanitin for 1 h, washed twice, and incubated without GnRH for times indicated. B, In cells treated with 100 nm GnRH after α-amanitin treatment and washout, Egr-1, SF-1, and ATF3 occupancy of the LHβ promoter was measured (closed symbols). Specificity of Egr-1 and SF-1 occupancy was demonstrated using primers targeting a distal upstream region of the LHβ gene approximately 3000 bp from the promoter [Egr-1 (D) and SF-1 (D), open symbols]. A representative time course is shown; error bars denote sem from real-time PCR replicates. Data were normalized to the 0-min time point with the −102 to −1 bp primer set to show percent increase from baseline and then analyzed using the CLUSTER8 pulse detection algorithm to detect peaks in transcription factor occupancy. Egr-1 and SF-1 peaks are denoted by asterisks at 30, 70, and 100 m GnRH. Average interpeak interval ± sem over four experiments for Egr-1 was 28.33 ± 3.1 min; for SF-1, average interpeak interval ± sem was 32.00 ± 2.0.

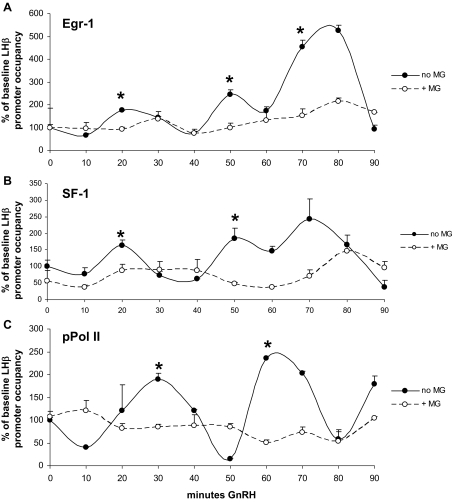

Cyclic transcription factor association with the LHβ promoter is proteasome dependent

We next wanted to determine whether the loss of LHβ transcription seen during proteasome inhibition involved alterations in the GnRH-stimulated patterns of transcription factor occupancy seen in Fig. 4. LβT2 cells were treated with GnRH with or without MG-132 and prepared for ChIP. MG-132 treatment prevented cyclic increases in Egr-1 promoter occupancy (Fig. 5A) and SF-1 promoter occupancy (Fig. 5B). Also, there was no statistically significant change in Egr-1 or SF-1 association with MG-132 treatment at the 0-min time point. In a separate experiment, we also measured association of phosphorylated RNA polymerase II (pPol II) during GnRH treatment and proteasome inhibition. The transcriptionally active form of this enzyme is phosphorylated on its C-terminal domain (35) and thus can be used as a marker of active gene transcription. pPol II association was rhythmically stimulated by GnRH and had a similar approximately 30-min period to Egr-1 and SF-1 (Fig. 5C). Proteasome inhibition resulted in a loss of GnRH-stimulated pPol II association with the LHβ promoter, further supporting the lack of transcription seen with MG-132 plus GnRH in luciferase and PT assays. Thus, proteasome activity is required for proper transcription factor cycling, recruitment of RNA polymerase II to the LHβ promoter, and consequently mRNA synthesis.

Figure 5.

MG-132 prevents cyclic transcription factor association with the LHβ promoter. ChIP was performed as in Fig. 4 except cells were treated with or without 50 μm MG-132 during the GnRH time course. A representative experiment (of at least three performed) using Egr-1 (A), SF-1 (B), or pPol II (C) antibodies is shown with error bars denoting sem from real-time PCR replicates. Data were analyzed using CLUSTER8 as in Fig. 4. Solid lines and circles show occupancy without MG-132; dashed lines and open circles show occupancy with MG-132. Peaks in transcription factor occupancy as detected by the CLUSTER8 algorithm are marked with asterisks.

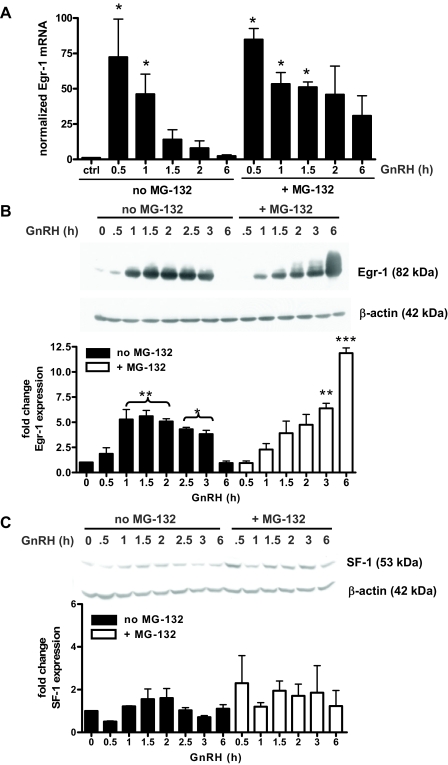

Endogenous Egr-1, but not SF-1, protein accumulates during proteasome inhibition

Because of the striking effects of MG-132 on GnRH-mediated LHβ transcription and promoter occupancy, we examined expression of endogenous Egr-1 and SF-1 during proteasome inhibition. LβT2 cells treated with GnRH showed detectable levels of Egr-1 mRNA and protein after 30 min, highest protein expression after 1.5 h, and a return to baseline levels at 6 h (Fig. 6, A and B). In the presence of MG-132, Egr-1 protein expression was slightly delayed but did occur, and resulted in accumulation of high levels of Egr-1 protein (Fig. 6B). Similar results were obtained with lactacystin (not shown). Like Egr-1 protein, Egr-1 mRNA remained elevated in the presence of MG-132 plus GnRH (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6.

Endogenous Egr-1 and SF-1 expression during GnRH and MG-132 treatment. A, Egr-1 mRNA levels in LβT2 cells treated with GnRH with or without MG-132 were measured using quantitative real-time RT-PCR. Egr-1 (B) and SF-1 (C) protein expression in LβT2 cells was measured by immunoblotting after a time course of GnRH with or without MG-132. Immunoblots pictured are representative of three separate experiments. Data from these experiments were quantified by densitometry, normalized to β-actin levels on the same blots and plotted as fold change in expression ± sem. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

It has been previously reported that pituitary SF-1 mRNA levels increase 1.5- to 1.8-fold with exogenous GnRH treatment in a GnRH-deficient rat model; however, SF-1 protein was not measured (36). We did not observe any significant GnRH-induced changes in SF-1 protein expression in LβT2 cells (Fig. 6C). In contrast to Egr-1, MG-132 plus GnRH did not lead to accumulation of SF-1 over the 6-h time course studied. Therefore, Egr-1, but not SF-1, protein synthesis is regulated by GnRH, and proteasome inhibition has dramatic effects on Egr-1 degradation.

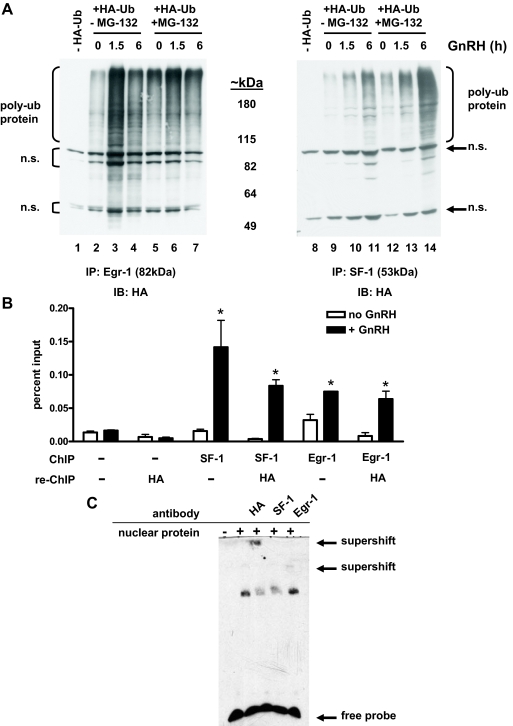

Egr-1 and SF-1 are ubiquitinated

We next examined whether Egr-1 and SF-1 were ubiquitinated in gonadotropes by transfecting LβT2 cells with a hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged ubiquitin expression vector (HA-Ub) and treating with GnRH for 0, 1.5, or 6 h, with or without MG-132. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with Egr-1 or SF-1 antibody and resolved by SDS-PAGE. HA antibody was then used for immunoblotting to detect protein covalently linked to HA-Ub. Figure 7, lane 1, shows immunopositive bands in the absence of introduced HA-Ub, whereas lanes 2–7 detect proteins containing HA-Ub immunoprecipitated by the Egr-1 antibody. For targeting to the proteasome, polyubiquitination, the addition of a chain containing four or more ubiquitin molecules, is required (37). Polyubiquitination therefore increases the molecular weight of proteins, and this corresponds to the large, slowly migrating proteins observed in our experiments.

Figure 7.

Association of ubiquitinated transcription factors with DNA. A, Cells were transfected with an HA-tagged ubiquitin expression vector and treated with 100 nm GnRH for 0, 1.5, or 6 h with or without 50 μm MG-132. For the 0-h GnRH, +MG-132 time point (lanes 5 and 12), cells were treated with MG-132 alone for 6 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with Egr-1 (left) or SF-1 (right) antibody, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and transferred to nitrocellulose. The membrane was then incubated with an anti-HA antibody to detect HA-Ub-Egr-1/SF-1 conjugates (poly-ub protein). Approximate molecular weights based on migration of a protein marker are indicated. Two sets of nonspecific bands were observed (n.s.). Representative blots from one of three separate experiments are shown. B, Re-ChIP experiments were performed using chromatin prepared from HA-Ub-transfected LβT2 cells. Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was first performed using Egr-1, SF-1, or no antibody, and complexes were eluted using dithiothreitol before a second immunoprecipitation (re-ChIP) using HA antibody to detect ubiquitinated protein associated with the LHβ promoter. Percentage of input DNA was quantified by real-time PCR. *, P < 0.05; n = 3. C, EMSA reactions were performed using a biotinylated oligonucleotide containing the proximal Egr-1 and SF-1 binding sites of the mouse LHβ promoter and nuclear protein from HA-Ub-transfected and GnRH-treated (100 nm, 1.5 h) LβT2 cells. Lanes 3–5 also contain either HA, SF-1, or Egr-1 antibody for supershift. A representative EMSA experiment is shown (n = 3).

Without GnRH, low but detectable levels of polyubiquitinated Egr-1 were present (Fig. 7, lane 2). In the absence of proteasome inhibition, total Egr-1 is decreased after 6 h GnRH (Fig. 6), and at this time, polyubiquitinated Egr-1 was also lower (Fig. 7, lane 4). GnRH stimulates Egr-1 mRNA and protein, and increased amounts of poly-Ub Egr-1 were seen after 1.5 h GnRH (Fig. 7, lane 3), in accordance with peak Egr-1 protein at 1.5 h GnRH in Fig. 6. Like Egr-1, polyubiquitinated SF-1 levels also increased with GnRH treatment (Fig. 7, lanes 10 and 11). MG-132 treatment prevents degradation of ubiquitinated protein and accordingly increased polyubiquitinated SF-1 levels (lanes 12–14) as well as levels of polyubiquitinated Egr-1 (Fig. 7, lanes 5–7).

Thus, Egr-1 and SF-1 are targets for polyubiquitination and the proteasome pathway. Although SF-1 total protein did not accumulate in the presence of proteasome inhibitor as did Egr-1, polyubiquitination of both factors increased after GnRH treatment. The stimulation of Egr-1 synthesis by GnRH and the proteasome-mediated degradation of Egr-1 and SF-1 may both be key for LHβ expression.

Ubiquitinated transcription factors bind DNA

To further probe the mechanistic interplay between transcription factor ubiquitination and transcription of the LHβ gene, we performed both re-ChIP and EMSA with HA-Ub-transfected LβT2 cells. For re-ChIP, chromatin-DNA complexes were first immunoprecipitated with antibody for Egr-1 or SF-1 and then eluted with dithiothreitol before a second immunoprecipitation with HA antibody. After 20 min GnRH treatment, both SF-1 and Egr-1 occupancy of the endogenous LHβ gene was increased (Fig. 7B). Interestingly, ubiquitinated SF-1 and Egr-1 were capable of binding the promoter, as detected by re-ChIP with HA antibody, and this was enhanced by GnRH treatment. When no antibody was used for the first immunoprecipitation, the HA antibody did not bring down appreciable amounts of LHβ promoter DNA.

We also performed EMSA using nuclear extracts from GnRH-treated LβT2 cells transfected with HA-Ub to determine whether ubiquitinated proteins could associate with biotin-labeled oligonucleotide containing the proximal LHβ promoter Egr-1 and SF-1 binding sites. Nuclear extracts were incubated with the biotinylated DNA alone or in the presence of SF-1, Egr-1, or HA antibodies, and complexes were resolved by nondenaturing PAGE. We observed a protein-DNA complex when the HA-Ub-transfected LβT2 nuclear extract was incubated with the biotinylated probe (Fig. 7C, lane 2); the band was reduced by SF-1 antibody (lane 4). This was expected for SF-1 association with DNA, because this antibody binds the SF-1 DNA-binding domain, and a similar result has been reported by other investigators (33). Inclusion of Egr-1 antibody (lane 5) in the EMSA reaction resulted in a supershift. Importantly, the DNA-protein complex was supershifted by HA antibody (lane 3), indicating that a HA-Ub-tagged protein was part of the initial complex. The corroborating results of two different approaches, re-ChIP and EMSA, indicate that ubiquitinated transcription factors can bind the LHβ promoter after GnRH treatment. Thus, cycles of promoter occupancy, ubiquitination, and degradation of transcription factors appear to all play a role in GnRH stimulation of LHβ transcription.

Discussion

GnRH pulses stimulate a plethora of intracellular signals that converge on the nucleus to alter gene expression. One of the genes most dramatically regulated by GnRH is LHβ, which requires induction of Egr-1 protein synthesis for expression. The proximal region of the LHβ promoter, which contains two Egr-1 and SF-1 binding sites, is highly conserved among mammalian species (38), and elimination of Egr-1 or SF-1 in vivo results in loss of fertility due to an inability to produce LH (12,39). Although the requirement for pulsatile GnRH to stimulate LHβ production is well established, the temporal events at the chromatin level that are responsible for LHβ mRNA synthesis are not well understood.

We used ChIP assays to establish a time course of Egr-1 and SF-1 promoter occupancy during GnRH treatment in LβT2 cells. LHβ promoter occupancy is low and disorganized without hormone (Fig. 4A). In the presence of GnRH, we observed a cyclic and coincidental association of Egr-1 and SF-1 with the LHβ promoter, fitting with the close proximity of Egr-1 and SF-1 binding sites on this gene and evidence that Egr-1 and SF-1 can physically interact in vitro (13,40). Although SF-1 associations may occur with the LHβ promoter basally, our findings suggest SF-1 association is increased in the presence of GnRH, which stimulates intracellular signaling and Egr-1 levels. ATF3, an immediate early transcription factor that has no binding sites on LHβ, did not show any specific associations during GnRH treatment. Importantly, Egr-1 and SF-1 did not interact with an upstream distal region of the LHβ gene, demonstrating specificity of the assay.

The Egr-1/SF-1 complex associated with the LHβ promoter at approximately 30-min intervals in response to GnRH (Fig. 4B); this pattern does not seem to be inherent to the proteins themselves. For example, in response to ACTH, SF-1 occupancy of the melanocortin 2 receptor (Mc2r) gene had a much longer period, approximately 80 min (41). The striking dissimilarity in SF-1 occupancy cycles between the Mc2r gene and the LHβ gene is likely due to multiple factors. Differences in promoter element composition, signaling pathway activation, cofactor recruitment, or protein degradation likely all contribute to the binding cycle length of any given transcription factor. In the presence of estradiol, ERα has been shown to associate with the endogenous mouse LHβ gene, presumably through a tethered association with other factors, with a similar 30-min period to that of Egr-1 and SF-1 reported here (29). In comparison, ERα association with estrogen response element-containing genes has a different period, approximately 45 min or longer (20,21,42).

The ubiquitin-proteasome system is linked to transcriptional activation in many scenarios, particularly those involving hormone-sensitive genes (20,25,26,43). We have shown that regulation of the LHβ gene by GnRH is proteasome dependent using the inhibitors MG-132 and lactacystin. Both a transfected rat LHβ luciferase reporter and endogenous mouse LHβ PT were dependent on proteasome activity for GnRH responsiveness (Figs. 1 and 2), and overexpression of Egr-1 or SF-1 was not sufficient to rescue GnRH-stimulated LHβ reporter activity (Fig. 3). Thus, our work implicates protein degradation via the proteasome in GnRH-stimulated LHβ transcription.

Proteasome inhibition blocks LHβ transcription at least in part by preventing proper transcription factor associations with the promoter. Neither Egr-1 nor SF-1 demonstrated increased occupancy in response to GnRH during proteasome inhibition (Fig. 5, A and B). Promoter occupancy by phosphorylated RNA polymerase II was cyclically increased by GnRH, again with an approximate period of 30 min (Fig. 5C). However, MG-132 treatment prevented recruitment of the transcriptionally active form of the enzyme, corroborating the lack of transcription seen in luciferase reporter and PT assays with MG-132. Hence, the GnRH signal stimulates LHβ transcription via coordinated recruitment of transcription factors and RNA polymerase II.

Loss of transcription factor occupancy with perturbations of the ubiquitin-proteasome system, similar to what we have observed in gonadotropes, has been described by others. As mentioned earlier, ERα can cyclically associate with the LHβ promoter during estradiol treatment; however, this association is prevented when a specific ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme, ubc4, is knocked down with siRNA (29). Both E3 ubiquitin ligases and components of the proteasome itself are recruited along with ERα to an estrogen response element-containing promoter (20). With proteasome inhibition, ERα binding is drastically reduced in magnitude and has a greatly extended period (2 h as opposed to 45 min); these unproductive occupancy events preclude RNA polymerase II recruitment and gene expression (20). Studies of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) have shown that HIF-1α-dependent recruitment of p300 to the erythropoietin gene is also proteasome dependent (44). Thus, enzymatic regulation of ubiquitination, patterns of transcription factor recruitment, and proteasome-dependent interactions with coactivators may all be points of convergence between transcription and degradation.

Transcription is also affected by the association of corepressors with promoters. Interaction of corepressors with DNA-binding transcription factors can limit the ability of transcription factors to promote mRNA synthesis. Interestingly, corepressors are also targets of the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Degradation of the corepressor Ski is enhanced by TGF-β treatment, and this is dependent on its interaction with activated Smad transcription factors (45). Nuclear receptor corepressor (N-CoR) protein levels increase with proteasome inhibition, correlating with increased transcriptional repression (46). Furthermore, treatment with retinoic acid can lead to a decrease in N-CoR association and an increase in coactivator [CREB binding protein (CBP and SRC-1)] association with a retinoic acid receptor-regulated promoter (47). A component of the N-CoR repression complex, transducin beta-like protein-1-related protein (TBLR1), helps mediate this switch between repression and activation by recruiting ubiquitin-proteasome pathway components, leading to degradation of N-CoR (47,48). Expression of the LHβ gene can be decreased by the DNA-binding repressor Zfhx1, as well as the Egr-1 corepressors Nab1 and Nab2, and the SF-1 corepressor Dax-1 (32,49). Zhfx1 sites on the LHβ promoter do not overlap with Egr-1 and SF-1 binding sites, but other unknown DNA binding repressors may exist. A requirement for repressor or corepressor removal before stimulated transcription factor binding during GnRH treatment may account for the lack of Egr-1 and SF-1 occupancy observed here during proteasome inhibition. Further analysis of Zfhx1, Nab1, Nab2, and Dax-1 occupancy of the LHβ promoter and protein levels during proteasome inhibition may reveal dynamics similar to the activator/repressor exchange reported for nuclear receptor/N-CoR-regulated genes.

Proteasome inhibition may also affect signaling proteins upstream from the nucleus. Certain PKC isoforms as well as inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors have been reported to be targets of the proteasome in gonadotropes (50,51). In those studies, prolonged GnRH exposure down-regulated both PKC and 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors, desensitizing cells to the hormone; proteasome inhibitors prevented this GnRH-induced down-regulation. Thus, it is unlikely that the effects we observed on LHβ transcription in the presence of MG-132 are due to changes in degradation of either of these two signaling molecules, because both are increased during proteasome inhibition, but potential effects on other GnRH-stimulated intracellular pathways cannot be ruled out. However, GnRH intracellular signaling is generally intact during MG-132 treatment, because Egr-1 synthesis is not prevented. Although the induction of Egr-1 protein by GnRH is slightly delayed, it is still produced. MG-132 alone did not produce significant accumulation of Egr-1 when basal levels were low (not shown), confirming that GnRH was still capable of stimulating the Egr-1 gene and protein synthesis.

Our data show that Egr-1 is polyubiquitinated in LβT2 cells (Fig. 7). In our LHβ luciferase reporter and PT assays, cells treated with MG-132 plus GnRH for 6 h did not respond to the hormonal stimulus (Figs. 1A and 2). From immunoblot analysis, we also observed that after 6 h of MG-132 plus GnRH treatment, Egr-1 protein accumulates to high levels in LβT2 cells (Fig. 6B). Despite large amounts of endogenous Egr-1 in the cells, LHβ transcription could not be stimulated. Similarly, high levels of exogenous Egr-1 did not rescue GnRH stimulation during proteasome inhibition (Fig. 3A). Thus, the presence of Egr-1 alone is not sufficient to stimulate transcriptional activity, and Egr-1 degradation appears tightly linked to its transcriptional activation capacity. Activity of other transcriptional activators, such as c-myc, ERα, and yeast Gcn4, has also been shown to depend on proteasome degradation (20,52,53).

We have shown that SF-1 is polyubiquitinated in gonadotropes as well, although no significant changes were detected in total SF-1 protein levels after proteasome inhibition over a 6-h period (Figs. 7 and 6C). In an adrenal cell line, SF-1 levels were reported to increase with MG-132 treatment, and SF-1 polyubiquitination was increased by histone deacetylase inhibition (54). However, these experiments were performed with a much higher MG-132 dose (10 mm) for 12 h, as opposed to 50 μm MG-132 for 6 h in our study. Like the differences in SF-1 promoter occupancy in adrenal cells, it appears that the kinetics of SF-1 degradation may also be cell type specific.

In some instances, monoubiquitination may have a role in modifying protein activity separate from the ubiquitin signal for proteasome degradation. For example, monoubiquitination of FOXO4 enhances both its nuclear localization and its transcriptional activity (27). Although our immunoprecipitations of Egr-1 and SF-1 detected large amounts of polyubiquitinated protein, monoubiquitination of these proteins could also be important in GnRH signaling. Transient monoubiquitination has been shown to increase the activity of the transcriptional coactivator SRC-3; intriguingly, further extension of the ubiquitin chain and degradation of SRC-3 appear to be dependent on its transcriptional capability (28). We did not detect monoubiquitination of Egr-1 or SF-1 under our experimental conditions, but more thorough investigation into the kinetics of GnRH-stimulated ubiquitination of factors like Egr-1 and SF-1 may uncover yet another layer of regulatory signals induced by this hormone.

Work in recent years has highlighted the ubiquitin-proteasome system as an important regulatory target of GnRH signaling. The discovery of a GnRH-inducible ubc4 (29), which specifically promotes ERα ubiquitination suggests that this enzyme or others not yet discovered may also ubiquitinate transcriptional activators in gonadotropes. Similarly, the ubiquitin E3 ligase SNURF has been shown to act as a coactivator of LHβ transcription and directly interact with SF-1 and Sp1 (16). Although it is unclear whether SNURF or ubc4 are directly involved in Egr-1 or SF-1 degradation in response to GnRH, our work shows that Egr-1 and SF-1 ubiquitination is increased after GnRH treatment. Furthermore, re-ChIP and EMSA studies demonstrate that GnRH treatment may also increase the interaction of ubiquitinated Egr-1 and SF-1 with the LHβ promoter. Proteasome activity may be required to remove basal levels of bound SF-1 and Egr-1 as well as associated regulatory proteins or other DNA binding proteins to allow GnRH-stimulated levels of activator association and transcription.

Control of the GnRH signal is vital to the proper functioning of the entire hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. In gonadotropes, GnRH activates many self-limiting mechanisms to ensure this control. For example, GnRH receptor expression is regulated by GnRH and changes over the estrous cycle in rats (55,56). Also, GnRH enhances the expression of MAPK phosphatases 1 and 2, which can limit GnRH-stimulated MAPK activation in gonadotropes (57). The data presented here suggest that proteasomal degradation, along with stimulation and modification of proteins, is another internal mechanism gonadotropes use to retain sensitivity to GnRH stimuli. Limiting the lifetime of transcriptional activators like Egr-1 would allow changes in GnRH levels to be more quickly integrated into the LHβ transcriptional response. In vivo, this mechanism would be extremely beneficial during the estrous cycle, when GnRH pulse frequency increases and then decreases rapidly.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and treatment

Clonal mouse gonadotrope LβT2 cells were originally obtained from Dr. Pamela Mellon (University of California, San Diego) and were maintained in DMEM plus phenol red (Mediatech, Herndon, VA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY) and 1% antibiotic/antimycotic (GIBCO). For experiments, cells were plated in phenol red-free DMEM, with 5% charcoal-stripped newborn calf serum (SNCS; GIBCO) and 2% l-glutamine (GIBCO). Cells were treated with 100 nm GnRH and/or 50 μm MG-132 proteasome inhibitor (in ethanol; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for times indicated. Cells receiving MG-132 plus GnRH were pretreated with MG-132 for 1 h before addition of GnRH.

Transient transfection and siRNA delivery

LβT2 cells were plated using DMEM plus 5% SNCS at a concentration of 500,000 cells per 20-mm well. The following day, cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer’s protocol with a luciferase reporter construct driven by the rat LHβ promoter, −617 to +41 bp relative to the transcription start site (11). Some wells also received a CMV-β-galactosidase plasmid as a transfection control. Total plasmid DNA per well was 1 μg, except in overexpression studies, where 0.5 μg rat LHβ reporter was cotransfected with 1 μg CMV-driven expression vectors for Egr-1 or SF-1 (58) or empty vector pcDNA 3.1. The day after transfection, cells were treated with GnRH with or without MG-132 for 6 h. Cells were washed with PBS, collected in 1× Promega (Madison, WI) cell culture lysis reagent, and then assayed for luciferase activity using a Turner TD-20e luminometer (Turner Designs, Mountain View, CA). For normalization, total protein concentration was measured using Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA) protein dye. Data are expressed as arbitrary light units per 100 μg protein; in some cases, fold increases compared with vehicle control are presented. Statistical significance was determined using one- or two-way ANOVA. All transfections were performed in triplicate at least three times.

For siRNA experiments, Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO) siGENOME SMARTpool siRNA directed toward mouse Egr-1 or a nontargeting negative control siRNA (siCON number 1; Dharmacon) were transfected into LβT2 cells using nucleofection technology according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Amaxa Corp., Gaithersburg, MD). The rat LHβ luciferase reporter (1.5 μg/reaction) was also transfected with siRNA (1 μg/reaction) using Solution T and Program A-020. Each reaction contained 5 × 106 cells and was divided between three wells in a 35-mm plate containing 2 ml 5% SNCS. Cell lysates were collected for luciferase activity measurement and immunoblotting to confirm Egr-1 knockdown. Experiments were performed in triplicate three times.

mRNA and PT assay

PT were measured as described previously (59). Briefly, RNA was isolated from LβT2 cells using the QIAGEN (Valencia, CA) RNeasy kit and was treated with DNase (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) to eliminate DNA contamination. Using 1 μg total RNA, reverse transcription of mRNA was carried out using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). cDNA was used as template for quantitative real-time PCR. Primers spanned the first intron/exon border of the mouse LHβ gene to detect unspliced mRNA PT (forward primer sequence, 5′-AGAGGCTCCAGGTAAGATGGTA-3′; reverse primer sequence, 5′-CCACTCAGTATAATACAGAAAC-3′). LHβ PT was normalized to GAPDH mRNA levels. Reactions containing no reverse transcriptase during cDNA synthesis were performed as a negative control. Data are expressed as fold change vs. 0-min control without MG-132; statistical significance was determined using unpaired t test. Three separate samples were performed with triplicate samples in each treatment. Detection of Egr-1 mRNA levels was performed similarly to LHβ PT, using primers for Egr-1 mRNA (60).

Immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation

LβT2 cell lysates were collected in 2× gel loading buffer [100 mm Tris-HCL (pH 6.8), 4% SDS, 20% glycerol] plus protease inhibitors, and protein concentration was measured using the Pierce (Rockford, IL) BCA Kit. Lysates were heated for 5 min at 95 C before 8% SDS-PAGE using 20 μg lysate; gels were then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes at 35 V for 3 h. Membranes were blocked using 10% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline plus 1% Tween 20 (TBST) overnight at 4 C and then incubated with primary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes were washed three times with TBST and then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (donkey antirabbit from Amersham, Piscataway, NJ; sheep antimouse from Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA). Polyclonal antibodies to Egr-1 (sc-189; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and SF-1 (Upstate, Temecula, CA) were used. Membranes were reprobed with monoclonal anti-β-actin antibody (Sigma) as loading control. Band intensity was measured by densitometry and normalized for β-actin in the same samples. Three separate studies were performed.

For immunoprecipitation experiments, LβT2 cells were plated in 10-cm plates (107 cells per plate) using 5% SNCS. The next day, 4 μg HA-tagged ubiquitin expression vector (HA-Ub, a gift of Dr. Deborah Lannigan, University of Virginia) was transfected using Lipofectamine 2000. After treatment, cells were harvested in M-PER buffer (Pierce) and centrifuged, and supernatants were immunoprecipitated using either Egr-1 or SF-1 antibodies overnight at 4 C. After a 1-h incubation with Protein G PLUS agarose beads (Santa Cruz), complexes were eluted in buffer with bromophenol blue [0.25 m Tris (pH 6.8), 4% SDS, 20% glycerol, 10% β-mercaptoethanol] and separated by PAGE before transfer to nitrocellulose. Membranes were blotted with monoclonal HA antibody (University of Virginia Lymphocyte Culture Facility).

ChIP and re-ChIP

ChIP was performed as described previously with modifications (59). LβT2 cells were treated with 100 nm GnRH and collected at 10-min intervals to establish a time course. Before GnRH treatment, cells were incubated in medium containing 2.5 μm α-amanitin for 1 h to synchronize promoter occupancy (20). In some instances, cells were coincubated with 50 μm MG-132 and α-amanitin to incorporate a 1-h pretreatment with MG-132. Cells were washed twice with PBS after α-amanitin treatment, and media with or without GnRH was added for 10-min intervals for 120 min. To prepare samples for ChIP, cells were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min, and the reaction was stopped by addition of glycine. Cross-linked chromatin was sonicated using a cup horn sonicator (Misonix, Farmingdale, NY); average sheared DNA size was 1000 bp. Whole-cell extract was divided and diluted with sonication buffer plus protease inhibitors before incubation with and without primary antibody overnight. Antibodies for Egr-1 and ATF3 were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, SF-1 antibody was from Upstate, and RNA polymerase II antibody (CTD4H8) was from Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO). Protein G PLUS agarose beads were then added for 2 h. Beads were washed extensively with sonication buffer and Tris-EDTA buffer before DNA elution. Protein cross-links were reversed by incubation with NaCl at 65 C overnight. DNA was purified for quantitative real-time PCR using the QIAGEN PCR purification kit.

Re-ChIP studies were performed as previously described (21,41). Cross-linked chromatin from LβT2 cells transfected with HA-Ub was prepared and sonicated as above. Whole-cell extract was divided into three primary immunoprecipitations (Egr-1, SF-1, or no antibody) and incubated overnight at 4 C with antibody. After incubation with Protein G PLUS beads and washing with sonication buffer and Tris-EDTA, protein-DNA complexes were eluted with 10 mm dithiothreitol at 37 C for 30 min; samples were then centrifuged and the supernatant diluted 1:20 in re-ChIP buffer (1% Triton X-100; 2 mm EDTA; 150 mm NaCl; 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.1) plus protease inhibitors. A second immunoprecipitation was performed using HA antibody to detect HA-Ub, and after cross-link reversal, DNA was purified as above. Results were quantified using real-time PCR as described below, and statistical significance was determined using the Student’s t test.

Real-time PCR and ChIP quantification

Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using primers directed toward the proximal region (−102 to −1 bp) of the mouse LHβ promoter (forward, 5′-CTGTGTCTCGCCCCCAAAGAGATTA-3′; reverse, 5′-CCTGGCTTTATACCTGCGGGGTT-3′). A primer set directed toward a distal upstream region of the mouse LHβ gene (−3268 to −3107 bp) was also used as a negative control (19). Continuous monitoring of SYBR green incorporation for 40 cycles using a Bio-Rad iCycler iQ determined threshold fluorescence; the cycle number where each sample crossed this threshold (Ct) was used to quantify relative amounts of DNA. Percentage of input DNA was extrapolated from each Ct value using a standard curve, and this percentage was normalized to account for differences in starting amounts of DNA due to treatment using a 10% input of starting material. Data are expressed as a percentage of baseline with the −102 to −1 bp primer set, where the 0-min time point equals 100%. At least three separate experiments were performed for each study. To determine significant peaks of transcription factor association with the LHβ promoter over time, ChIP data were analyzed using the CLUSTER8 pulse detection algorithm (34). This program uses pooled t testing to identify both peaks and nadirs and determine mean peak interval. Significant peaks of transcription factor association were detected using a peak cluster size of 2.0, a nadir cluster size of 1.0, and minimum t-score of 2.0.

EMSA

Nuclear extracts were prepared as previously described (49) using LβT2 cells transfected with HA-Ub and treated with 100 nm GnRH for 1.5 h. Nonradioactive EMSA was performed using the Lightshift chemiluminescent EMSA kit (Pierce). Complementary oligonucleotides were biotinylated using the biotin 3′-end labeling kit (Pierce) and then annealed. The sense oligo sequence was 5′-CTTAGTGGCCTTGCCACCCCCACAACCC-3′ and includes the proximal Egr-1 and SF-1 binding sites of the mouse LHβ promoter. Nuclear extracts (8 μg) were incubated with 60 fmol biotinylated oligo, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1× binding buffer, and 1 μg poly(deoxyinosine-deoxycytosine) for 20 min at room temperature. For supershifts, 1 μl Egr-1, SF-1, or HA antibody was incubated with all reaction components except labeled DNA for 15 min, and then biotinylated oligo was added and incubation continued for 20 min. Complexes were resolved by nondenaturing PAGE (4% acrylamide gel containing 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA) at 100 V at 4 C for 1 h 15 min. Complexes were then transferred to a positively charged nylon membrane (Pierce) for 30 min at 0.38 A; membranes were cross-linked using FB-UVXL-1000 microprocessor-controlled UV cross-linker (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH) at an energy dosage of 120 mJ/cm2. DNA-protein complexes were visualized using Pierce detection reagents.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health through cooperative agreement (U54 HD28934) as part of the Specialized Cooperative Centers Program in Reproduction Research through both an individual research project (to M.A.S.) and the Molecular Core at the University of Virginia.

Disclosure Summary: M.A.S. has received royalties from Upstate Biotechnology (now Millipore Corp.).

First Published Online December 18, 2008

Abbreviations: ATF3, Activating transcription factor 3; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; CMV, cytomegalovirus; Egr-1, early growth response-1; ERα, estrogen receptor α; HA, hemagglutinin; HA-ub, HA-tagged ubiquitin expression vector; N-CoR, nuclear receptor corepressor; PKC, protein kinase C; pPol II, phosphorylated RNA polymerase II; PT, primary transcript; SF-1, steroidogenic factor-1; siRNA, small interfering RNA; SNCS, charcoal-stripped newborn calf serum; SNURF, small nuclear ring finger protein; SRC-3, steroid receptor coactivator-3; ubc, ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme.

References

- Ferris HA, Shupnik MA 2006 Mechanisms for pulsatile regulation of the gonadotropin subunit genes by GNRH1. Biol Reprod 74:993–998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haisenleder DJ, Dalkin AC, Ortolano GA, Marshall JC, Shupnik MA 1991 A pulsatile gonadotropin-releasing hormone stimulus is required to increase transcription of the gonadotropin subunit genes: evidence for differential regulation of transcription by pulse frequency in vivo. Endocrinology 128:509–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger LL, Dalkin AC, Aylor KW, Haisenleder DJ, Marshall JC 2002 GnRH pulse frequency modulation of gonadotropin subunit gene transcription in normal gonadotropes: assessment by primary transcript assay provides evidence for roles of GnRH and follistatin. Endocrinology 143:3243–3249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belchetz PE, Plant TM, Nakai Y, Keogh EJ, Knobil E 1978 Hypophysial responses to continuous and intermittent delivery of hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone. Science 202:631–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen JS, Quirk CC, Nilson JH 2004 Multiple and overlapping combinatorial codes orchestrate hormonal responsiveness and dictate cell-specific expression of the genes encoding luteinizing hormone. Endocr Rev 25:521–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haisenleder DJ, Burger LL, Walsh HE, Stevens J, Aylor KW, Shupnik MA, Marshall JC 2008 Pulsatile gonadotropin-releasing hormone stimulation of gonadotropin subunit transcription in rat pituitaries: evidence for the involvement of Jun N-terminal kinase but not p38. Endocrinology 149:139–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus S, Naor Z, Seger R 2001 Intracellular signaling pathways mediated by the gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) receptor. Arch Med Res 32:499–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haisenleder DJ, Ferris HA, Shupnik MA 2003 The calcium component of gonadotropin-releasing hormone-stimulated luteinizing hormone subunit gene transcription is mediated by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase type II. Endocrinology 144:2409–2416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan WR, Ito M, Park Y, Maizels ET, Hunzicker-Dunn M, Jameson JL 2002 GnRH regulates early growth response protein 1 transcription through multiple promoter elements. Mol Endocrinol 16:221–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halvorson LM, Kaiser UB, Chin WW 1999 The protein kinase C system acts through the early growth response protein 1 to increase LHβ gene expression in synergy with steroidogenic factor-1. Mol Endocrinol 13:106–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weck J, Anderson AC, Jenkins S, Fallest PC, Shupnik MA 2000 Divergent and composite gonadotropin-releasing hormone-responsive elements in the rat luteinizing hormone subunit genes. Mol Endocrinol 14:472–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SL, Sadovsky Y, Swirnoff AH, Polish JA, Goda P, Gavrilina G, Milbrandt J 1996 Luteinizing hormone deficiency and female infertility in mice lacking the transcription factor NGFI-A (Egr-1). Science 273:1219–1221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser UB, Halvorson LM, Chen MT 2000 Sp1, steroidogenic factor 1 (SF-1), and early growth response protein 1 (Egr-1) binding sites form a tripartite gonadotropin-releasing hormone response element in the rat luteinizing hormone-β gene promoter: an integral role for SF-1. Mol Endocrinol 14:1235–1245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay JJ, Drouin J 1999 Egr-1 is a downstream effector of GnRH and synergizes by direct interaction with Ptx1 and SF-1 to enhance luteinizing hormone β gene transcription. Mol Cell Biol 19:2567–2576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang QR, Jeong KH, Horton CD, Halvorson LM 2005 Pituitary homeobox 1 (Pitx1) stimulates rat LHβ gene expression via two functional DNA-regulatory regions. J Mol Endocrinol 35:145–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin D, Ferris HA, Hakli M, Gibson M, Janne OA, Palvimo JJ, Shupnik MA 2004 Small nuclear RING finger protein stimulates the rat luteinizing hormone-β promoter by interacting with Sp1 and steroidogenic factor-1 and protects from androgen suppression. Mol Endocrinol 18:1263–1276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouillet JF, Sonnenberg-Hirche C, Yan XM, Sadovsky Y 2004 p300 regulates the synergy of steroidogenic factor-1 and early growth response-1 in activating luteinizing hormone-β subunit gene. J Biol Chem 279:7832–7839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner S, Maudsley S, Millar RP, Pawson AJ 2007 Nuclear stabilization of β-catenin and inactivation of glycogen synthase kinase-3β by gonadotropin releasing hormone: targeting Wnt signaling in the pituitary gonadotrope. Mol Endocrinol 21:3028–3038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salisbury TB, Binder AK, Grammer JC, Nilson JH 2007 Maximal activity of the luteinizing hormone β-subunit gene requires β-catenin. Mol Endocrinol 21:963–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid G, Hubner MR, Metivier R, Brand H, Denger S, Manu D, Beaudouin J, Ellenberg J, Gannon F 2003 Cyclic, proteasome-mediated turnover of unliganded and liganded ERα on responsive promoters is an integral feature of estrogen signaling. Mol Cell 11:695–707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metivier R, Penot G, Hubner MR, Reid G, Brand H, Kos M, Gannon F 2003 Estrogen receptor-α directs ordered, cyclical, and combinatorial recruitment of cofactors on a natural target promoter. Cell 115:751–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XM, Odom DT, Koo SH, Conkright MD, Canettieri G, Best J, Chen HM, Jenner R, Herbolsheimer E, Jacobsen E, Kadam S, Ecker JR, Emerson B, Hogenesch JB, Unterman T, Young RA, Montminy M 2005 Genome-wide analysis of cAMP-response element binding protein occupancy, phosphorylation, and target gene activation in human tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:4459–4464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershko A, Ciechanover A 1998 The ubiquitin system. Annu Rev Biochem 67:425–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muratani M, Tansey WR 2003 How the ubiquitin-proteasome system controls transcription. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 4:192–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Z, Pirskanen A, Janne OA, Palvimo JJ 2002 Involvement of proteasome in the dynamic assembly of the androgen receptor transcription complex. J Biol Chem 277:48366–48371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dace A, Zhao L, Park KS, Furuno T, Takamura N, Nakanishi M, West BL, Hanover JA, Cheng SY 2000 Hormone binding induces rapid proteasome-mediated degradation of thyroid hormone receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 8985–8990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Horst A, Vries-Smits AM, Brenkman AB, van Triest MH, van den Broek N, Colland F, Maurice MM, Burgering BM 2006 FOXO4 transcriptional activity is regulated by monoubiquitination and USP7/HAUSP. Nat Cell Biol 8:1064–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu RC, Feng Q, Lonard DM, O'Malley BW 2007 SRC-3 coactivator functional lifetime is regulated by a phospho-dependent ubiquitin time clock. Cell 129:1125–1140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo M, Koh M, Feng J, Wu Q, Melamed P 2005 Cross talk in hormonally regulated gene transcription through induction of estrogen receptor ubiquitylation. Mol Cell Biol 25:7386–7398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DH, Goldberg AL 1998 Proteasome inhibitors: valuable new tools for cell biologists. Trends Cell Biol 8:397–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorn C, Ou QL, Svaren J, Crawford PA, Sadovsky Y 1999 Activation of luteinizing hormone β gene by gonadotropin-releasing hormone requires the synergy of early growth response-1 and steroidogenic factor-1. J Biol Chem 274:13870–13876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson MA, Tsutsumi R, Zhang H, Talukdar I, Butler BK, Santos SJ, Mellon PL, Webster NJ 2007 Pulse sensitivity of the luteinizing hormone β promoter is determined by a negative feedback loop involving early growth response-1 and Ngfi-A binding protein 1 and 2. Mol Endocrinol 21:1175–1191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe MW, Call GB 1999 Early growth response protein 1 binds to the luteinizing hormone-β promoter and mediates gonadotropin-releasing hormone-stimulated gene expression. Mol Endocrinol 13:752–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldhuis JD, Johnson ML 1986 Cluster analysis: a simple, versatile, and robust algorithm for endocrine pulse detection. Am J Physiol 250:E486–E493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phatnani HP, Greenleaf AL 2006 Phosphorylation and functions of the RNA polymerase IICTD. Genes Dev 20:2922–2936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haisenleder DJ, Yasin M, Dalkin AC, Gilrain J, Marshall JC 1996 GnRH regulates steroidogenic factor-1 (SF-1) gene expression in the rat pituitary. Endocrinology 137:5719–5722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrower JS, Hoffman L, Rechsteiner M, Pickart CM 2000 Recognition of the polyubiquitin proteolytic signal. EMBO J 19:94–102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Call GB, Wolfe MW 2002 Species differences in GnRH activation of the LH beta promoter: role of Egr1 and Sp1. Mol Cell Endocrinol 189:85–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao LP, Bakke M, Hanley NA, Majdic G, Stallings NR, Jeyasuria P, Parker KL 2004 Tissue-specific knockouts of steroidogenic factor 1. Mol Cell Endocrinol 215:89–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay JJ, Marcil A, Gauthier Y, Drouin J 1999 Ptx1 regulates SF-1 activity by an interaction that mimics the role of the ligand-binding domain. EMBO J 18:3431–3441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winnay JN, Hammer GD 2006 Adrenocorticotropic hormone-mediated signaling cascades coordinate a cyclic pattern of steroidogenic factor 1-dependent transcriptional activation. Mol Endocrinol 20:147–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang YF, Hu X, DiRenzo J, Lazar MA, Brown M 2000 Cofactor dynamics and sufficiency in estrogen receptor-regulated transcription. Cell 103:843–852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange CA, Shen TJ, Horwitz KB 2000 Phosphorylation of human progesterone receptors at serine-294 by mitogen-activated protein kinase signals their degradation by the 26S proteasome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:1032–1037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin DH, Li SH, Chun YS, Huang LE, Kim MS, Park JW 2008 CITED2 mediates the paradoxical responses of HIF-1α to proteasome inhibition. Oncogene 27:1939–1944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Scolan E, Zhu QW, Wang L, Bandyopadhyay A, Javelaud D, Mauviel M, Sun LZ, Luo KX 2008 Transforming growth factor-β suppresses the ability of ski to inhibit tumor metastasis by inducing its degradation. Cancer Res 68:3277–3285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JS, Guenther MG, Carthew RW, Lazar MA 1998 Proteasomal regulation of nuclear receptor corepressor-mediated repression. Genes Dev 12:1775–1780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perissi V, Aggarwal A, Glass CK, Rose DW, Rosenfeld MG 2004 A corepressor/coactivator exchange complex required for transcriptional activation by nuclear receptors and other regulated transcription factors. Cell 116:511–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perissi V, Scafoglio C, Zhang J, Ohgi KA, Rose DW, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG 2008 TBL1 and TBLR1 phosphorylation on regulated gene promoters overcomes dual CtBP and NCoR/SMRT transcriptional repression checkpoints. Mol Cell 29:755–766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowase T, Walsh HE, Darling DS, Shupnik MA 2007 Estrogen enhances gonadotropin-releasing hormone-stimulated transcription of the luteinizing hormone subunit promoters via altered expression of stimulatory and suppressive transcription factors. Endocrinology 148:6083–6091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junoy B, Maccario H, Mas JL, Enjalbert A, Drouva SV 2002 Proteasome implication in phorbol ester- and GnRH-induced selective down-regulation of PKC (α, ε, ξ) in αT3-1 and LβT2 gonadotrope cell lines. Endocrinology 143:1386–1403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojcikiewicz RJ, Xu Q, Webster JM, Alzayady K, Gao C 2003 Ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of endogenous and exogenous inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors in αT3-1 anterior pituitary cells. J Biol Chem 278:940–947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von der Lehr N, Johansson S, Wu S, Bahram F, Castell A, Cetinkaya C, Hydbring P, Weidung I, Nakayama K, Nakayama KI, Soderberg O, Kerppola TK, Larsson LG 2003 The F-Box protein Skp2 participates in c-Myc proteosomal degradation and acts as a cofactor for c-Myc-regulated transcription. Mol Cell 11:1189–1200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipford JR, Smith GT, Chi Y, Deshaies RJ 2005 A putative stimulatory role for activator turnover in gene expression. Nature 438:113–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WY, Weng JH, Huang CC, Chung BC 2007 Histone deacetylase inhibitors reduce steroidogenesis through SCF-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of steroidogenic factor 1 (NR5A1). Mol Cell Biol 27:7284–7290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savoy-Moore RT, Schwartz NB, Duncan JA, Marshall JC 1980 Pituitary gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptors during the rat estrous-cycle. Science 209:942–944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padmanabhan V, Dalkin A, Yasin M, Haisenleder DJ, Marshall JC, Landefeld TD 1995 Are immediate early genes involved in gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor gene regulation? Characterization of changes in GnRH receptor (Gnrh-R), C-Fos, and C-Jun messenger ribonucleic acids during the ovine estrous cycle. Biol Reprod 53:263–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T, Roberson MS 2006 Role of MAP kinase phosphatases in GnRH-dependent activation of MAP kinases. J Mol Endocrinol 36:41–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin D, Jenkins S, Farmer N, Anderson AC, Haisenleder DJ, Rissman E, Wilson EM, Shupnik MA 2001 Androgen suppression of GnRH-stimulated rat LHβ gene transcription occurs through Sp1 sites in the distal GnRH-responsive promoter region. Mol Endocrinol 15:1906–1917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferris HA, Walsh HE, Stevens J, Fallest PC, Shupnik MA 2007 Luteinizing hormone beta promoter stimulation by adenylyl cyclase and cooperation with gonadotropin-releasing hormone 1 in transgenic mice and LβT2 cells. Biol Reprod 77:1073–1080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buggs C, Weinberg F, Kim E, Wolfe A, Radovick S, Wondisford F 2006 Insulin augments GnRH-stimulated LHβ gene expression by Egr-1. Mol Cell Endocrinol 249:99–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]