Abstract

FoxO (mammalian forkhead subclass O) proteins are transcription factors acting downstream of the PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10) tumor suppressor. Their activity is negatively regulated by AKT-mediated phosphorylation. Our previous studies showed that the transcriptional activity of the androgen receptor (AR) was inhibited by PTEN in an AKT-sensitive manner. Here, we report the repression of the activity of the full-length AR and its N-terminal domain by FoxO1 and the participation of FoxO1 in AR inhibition by PTEN. Ectopic expression of active FoxO1 decreased the transcriptional activity of AR as well as androgen-induced cell proliferation and production of prostate-specific antigen. FoxO1 knock down by RNA interference increased the transcriptional activity of the AR in PTEN-intact cells and relieved its inhibition by ectopic PTEN in PTEN-null cells. Mutational analysis revealed that FoxO1 fragment 150–655, which contains the forkhead box and C-terminal activation domain, was required for AR inhibition. Mammalian two-hybrid and glutathione-S-transferase pull-down assays demonstrated that the inhibition of AR activity by PTEN through FoxO1 involved the interference of androgen-induced interaction of the N- and C-termini of the AR and the recruitment of the p160 coactivators to its N terminus and to the androgen response elements of natural AR target genes. These studies reveal new mechanisms for the inhibition of AR activity by PTEN-FoxO axis and establish FoxO proteins as important nuclear factors that mediate the mutual antagonism between AR and PTEN tumor suppressor in prostate cancer cells.

The studies establish nuclear FoxO factors as mediators of the inhibition of AR N/C interaction and coactivator recruitment by the PTEN tumor suppressor.

Androgens drive the growth and development of the prostate gland. In addition, androgens and the androgen receptor (AR) are also implicated in multiple pathological processes of the gland, including prostate cancer (PCa), a leading cause of cancer deaths in American men (1). The AR is a member of steroid/thyroid hormone receptor superfamily. It is a transcription factor activated by androgens such as testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT) (2). Similar to other steroid receptors, the AR is composed of an N-terminal domain (NTD) containing a major activation function, AF-1, a DNA-binding domain (DBD) with two C2C2 zinc fingers, a hinge region, and a C-terminal ligand-binding domain (LBD), which contains a weak activation function, AF-2 (3). Androgens induce an interaction between the N- and C-termini of the AR, namely N/C interaction that involves the 23FXXLF27 motif and its flanking sequence in the NTD and a hydrophobic cleft in the LBD (4), an event that is critical for the biological actions of the receptor (5,6). The transcriptional activity of the AR is modulated by an array of coregulators, including common coactivators and steroid receptor coactivators (SRCs) as well as AR-selective coactivators (7). They convey the effect of the AR on androgen response element (ARE)-mediated transcription by directly remodeling the chromatin structure through the acetylation of core histones.

Phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN) is a tumor suppressor gene frequently deleted in a variety of advanced human cancers, including cancers of the prostate (8,9). PTEN mutations have been identified in 10–15% of all prostate tumors and in up to 60% of advanced PCa and PCa cell lines (9). PTEN encodes a protein/lipid dual phosphatase the main in vivo substrate of which is phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-triphosphate, the product of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K). Growth factor-stimulated production of phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-triphosphate results in activation of AKT, allowing cell survival and proliferation. PTEN suppresses tumor growth by inhibiting the PI3K-AKT signal pathway (8).

The mammalian forkhead subclass O (FoxO) family of transcriptional factors includes FoxO1, FoxO3a, FoxO4, and FoxO6. Except for FoxO6, each of them becomes a direct AKT substrate after cellular stimulation by growth factors or insulin, which inactivates FoxO by promoting their nuclear export, binding to 14-3-3, and degradation. Inactivation of FoxO proteins perturbs the critical balance between cell proliferation and death and contributes to tumorigenesis by promoting cell growth and cell survival (10). Because PTEN suppresses AKT activity, it is expected that some aspects of PTEN action are mediated through FoxO factors. Consistently, genetic and biochemical analyses have shown that PTEN acts through FoxO factors to control oocyte activation (11) and cancer cell growth (10).

Previous work from our laboratory showed a mutual repression between PTEN and the AR in the growth and the apoptosis of PCa cells (12). We have also reported an AR-dependent repression of FoxO1 and FoxO3a functions by androgens (13). The present study aims to clarify whether FoxO factors play a role in the inhibition of the AR by PTEN. We show that FoxO1 disrupts the binding of p160 SRCs to AR NTD and suppresses the N/C interaction of the AR. Moreover, PTEN inhibits AR N/C interaction and AIB1 recruitment to AR NTD, which is relieved by FoxO1 small interfering RNA (siRNA).

Results

FoxO factors inhibit AR transcriptional activity and mediate the AR suppression by PTEN

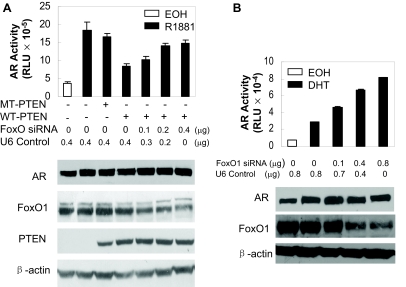

To test the involvement of FoxO1 in the suppression of AR activity by PTEN, the effect of active PTEN on AR activity was assayed in the presence or absence of a FoxO siRNA (14) that was effective in knocking down FoxO1, FoxO3a, and FoxO4 in mammalian cells (Fig. 1 and data not shown). Ectopic expression of the active PTEN in PTEN-null PC3 cells (15) decreased AR activity on a synthetic ARE-based reporter relative to phosphatase-inactive PTEN. Cotransfection of FoxO siRNA relieved the suppression by PTEN in a dose-dependent manner. In PTEN-intact RWPE-1 cells, the FoxO siRNA increased AR activity in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1B). This siRNA decreased the expression of endogenous FoxO1 without altering the level of AR, PTEN, and β-actin (Fig. 1, A and B). These experiments show that endogenous FoxO factors decrease the transcriptional activity of the AR and mediate AR inhibition by PTEN. It is important to note that RWPE-1 is a nonneoplastic human prostate epithelial cell line immortalized by the human papilloma virus, HPV-18. This cell line was described as AR positive and androgen sensitive for growth (16). In our hands, however, the cell expresses low basal levels of AR protein and is androgen insensitive. Androgen-induced transcriptional activity was only detectable when ectopic AR was expressed (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Knockdown of FoxO factors relieves AR inhibition by PTEN in prostate cells. A, PC3 cells were transfected with 0.5 μg AREe1bLuc, 0.1 μg pCMVβ, 0.1 μg pCMVhAR, 0.05 μg wild-type (WT-PTEN) or G129R mutant (MT-PTEN) PTEN together with the indicated amounts of FoxO siRNA or U6 control; 48 h later, cells were treated for 24 h with ethanol (EOH) as vehicle control or 10 nm R1881. Luciferase activity was determined and normalized to cognate β-galactosidase (β-gal) activity. Cell extracts from parallel transfections were immunoblotted with antibodies against AR, FoxO1, PTEN (HA11), or β-actin. B, RWPE-1 cells were transfected as in panel A but without PTEN. Cells were treated and reporter assays and immunoblotting analyses were similarly performed and presented. RLU, Relative luciferase units.

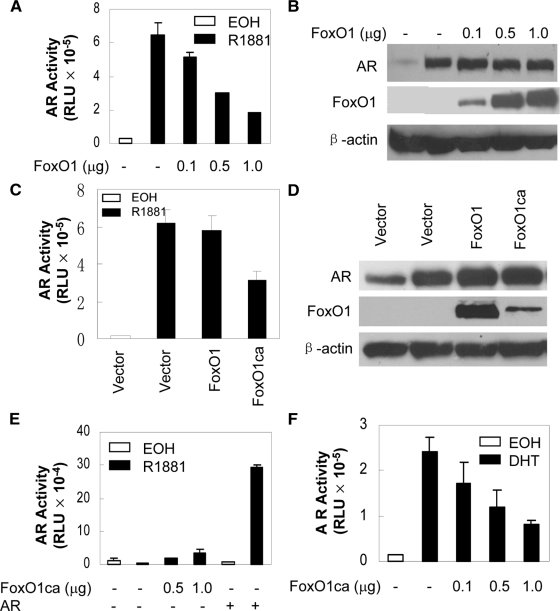

We next tested whether ectopic expression of FoxO1 inhibited AR transcriptional activity. In PTEN intact COS-7 cells, wild-type FoxO1 decreased ectopic AR activity in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A) but not the level of AR protein expression (Fig. 2B). In PC3 cells that contain low levels of nuclear FoxO factors, due to loss of PTEN and the increase in the kinase activity of AKT, a nuclear FoxO1, FoxO1ca, in which all three AKT phosphorylation sites were mutated to alanines (13), decreased androgen-induced AR activity whereas wild-type FoxO1 had little effect (Fig. 2C). Parallel immunoblotting analyses showed that wild-type FoxO1 was expressed to a level higher than FoxO1ca (Fig. 2D), showing that the lack of an effect of wild-type FoxO1 on AR was not due to its insufficient expression. Furthermore, in the absence of AR, FoxO1ca did not decrease the activity of the basal AR reporter, demonstrating that the inhibition is AR specific (Fig. 2E).

Figure 2.

Dose-dependent inhibition of AR activity by FoxO1. A, COS-7 cells were transfected with 0.5 μg AREe1bluc, 50 ng pCMVβ, 50 ng pCMVhAR, and the indicated amounts of Flag-FoxO1 and treated for 24 h with EOH or 10 nm R1881. Reporter activity was determined as in Fig. 1A. B, Lysates of COS-7 cells transfected as in panel A were immunoblotted with antibodies against AR, Flag, or β-actin. C, PC3 cells were transfected with 0.5 μg AREe1bluc, 50 ng pCMVβ, 50 ng pCMVhAR, 1 μg Flag-FoxO1, or HA-FoxO1ca. Transfected cells were treated for 24 h with EOH or 10 nm R1881. Reporter activity was determined as in Fig. 1A. D, Lysates of PC3 cells transfected as in panel C were immunoblotted with antibodies against AR, FoxO1, and β-actin. E, PC3 cells were transfected with the indicated amounts of HA-FoxO1ca with or without AR, and reporter activity was determined after treatment with EOH or 10 nm R1881. F, LNCaP cells were transfected with 0.5 μg p(−286/+28)PBLuc, 0.1 μg pCMVβ, and the indicated amounts of HA-FOXO1ca. Transfected cells were treated with EOH or 100 nm DHT, and the activity of endogenous AR was normalized with β-gal. RLU, Relative luciferase units.

To determine whether FoxO1 also represses the activity of endogenous AR on the promoter of natural androgen target genes, we transfected FoxO1ca into PTEN-null, AR-positive LNCaP cells (15) and examined its effect on the activity of endogenous AR on p(−286/+28)PBLuc reporter in which the expression of firefly luciferase gene is under the control of the rat probasin gene promoter (17). As shown in Fig. 2F, the transcriptional activity of endogenous AR was stimulated by its natural ligand DHT, and FoxO1ca inhibited the activity in a dose- dependent manner. These data suggest that the inhibition by active FoxO1 is not limited to ectopic AR or synthetic AREs.

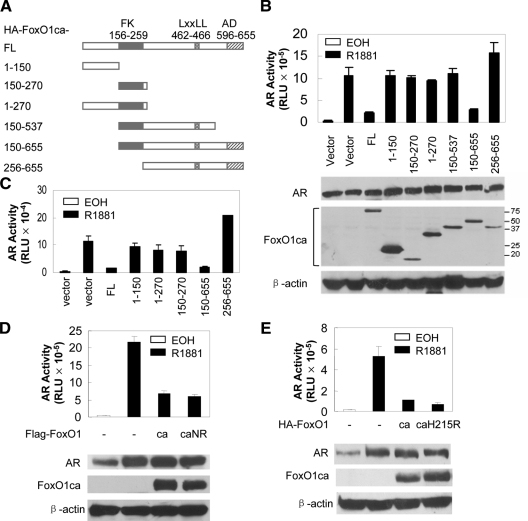

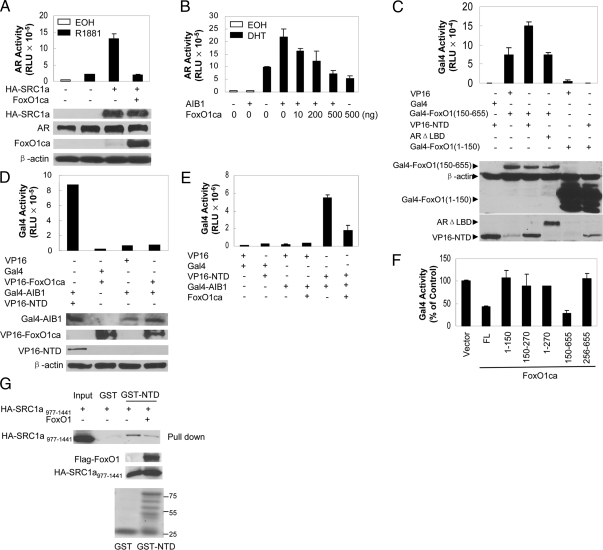

Defining FoxO1 domains involved in AR repression

FoxO1 is a 655-amino acid protein with a short N terminus, a highly conserved forkhead box necessary for DNA binding, a LXXLL motif, and a proline-, acidic residue-, and serine/threonine-rich activation domain (AD) (18). To define the FoxO1 domain involved in AR repression, we generated a set of plasmids expressing different regions of FoxO1ca (Fig. 3A) and tested their ability to inhibit the activity of the AR ectopically expressed in PC3 cells on ARR3TKLuc, a reporter gene in which the expression of the firefly luciferase gene is under the control of three copies of the complex ARE present in the proximal region of the rat probasin gene and the promoter of the thymidine kinase gene (19). In these assays, FoxO1ca [amino acids (aa) 150–655] decreased AR activity to a similar degree as full-length FoxO1ca whereas FoxO1ca (aa 1–150), FoxO1ca (aa 150–270), FoxO1ca (aa 1–270), FoxO1ca (aa 150–537), and FoxO1ca (aa 256–655) did not decrease AR activity (Fig. 3B). Parallel immunoblotting analyses showed that the FoxO1ca fragments were expressed to a level either comparable with or higher than that of full-length FoxO1ca, showing that the lack of inhibition by the FoxO1 fragments was not due to their insufficient expression (Fig. 3B). Similar results were obtained with endogenous AR on p(−286/+28)PBLuc reporter in LNCaP cells (Fig. 3C). These analyses demonstrate that the inhibition of AR activity by FoxO1 requires the forkhead box and the C-terminal activation domain whereas the N-terminal 150 amino acids are nonessential.

Figure 3.

Mapping FoxO1 domains required for AR inhibition. A, A diagram of human FoxO1 fragments. Different fragments corresponding to the indicated amino acids were amplified by PCR and inserted into the pCDNA3.1-HA vector to make a subset of FoxO1ca subclones. FK, Forkhead box; AD, activation domain; FL, full length. B, Upper panel , PC3 cells were transfected with 0.5 μg ARR3TKLuc, 50 ng pCMVβ, 50 ng AR, and different amounts of the FoxO1ca fragments. Transfected cells were treated and reporter activity was determined as in Fig. 1A. B, Lower panels, Lysates of PC3 cells transfected with the plasmids as in the upper panel were immunoblotted with antibodies against AR, HA, and β-actin. C, FoxO1ca fragments were transfected into LNCaP cells together with 0.5 μg p(−286/+28)PBLuc and treated with EOH or 10 nm R1881. The activity of endogenous AR was measured as in Fig. 2F. D and E, FoxO1ca (CA), FoxO1ca with mutations in the NR box (CaNRmut), or FoxO1ca with mutation in the forkhead box (CaH215R) was transfected together with AR and AREe1bLuc into PC3 cells and treated as in Fig. 2C. Reporter activity was determined as in Fig. 1A. Immunoblotting analyses were performed with anti-AR and M2 (panel D) or HA (panel E) antibody.

SRC proteins interact with nuclear receptors via short motifs called “nuclear receptor box” (NR box) consisting of the amino acid sequence LXXLL, where X can be any amino acid. The presence of a putative NR box sequence 462LKELL466, close to the C-terminal AD of FoxO1, prompted us to test whether this motif is involved in the AR repression by FoxO1. We generated a mutant FoxO1, FoxO1CaNR, in which the LKELL motif was mutated to WKEWL, and assessed its ability to inhibit AR in PC3 cell. As shown in Fig. 3D, the mutant FoxO1 inhibited the AR activity to the same degree as FoxO1ca. Parallel immunoblotting analyses showed that the FoxO1caNR was expressed to a comparable level as FoxO1ca and did not have an effect on AR expression. These analyses suggest that mutations of the putative NR box do not affect the ability of FoxO1ca to inhibit AR.

Because AR inhibition by FoxO1 requires the DBD, it is possible that a FoxO1 target gene mediates it. Although there are multiple ways for FoxO factors to regulate gene expression (20), the primary mechanism is through the binding of forkhead box to insulin-response sequences (IRS). To test whether the AR inhibition depends on the ability of FoxO1 to bind IRS elements, we generated a FoxO1 mutant, FoxO1caH215R, in which a conserved histidine in helix 3 of the forkhead box was mutated to arginine to abrogate its ability to bind IRS (20) and tested its ability to inhibit AR. As shown in Fig. 3E, FoxO1caH215R inhibited AR activity to the same degree as FoxO1ca. Parallel immunoblotting analyses showed that the FoxO1caH215R was expressed to a comparable level as FoxO1ca and did not have an effect on AR expression.

These analyses show that the forkhead box and the AD in the C terminus are required for AR inhibition, but the inhibition occurs independently of the putative NR box and the ability of FoxO1 to bind IRS.

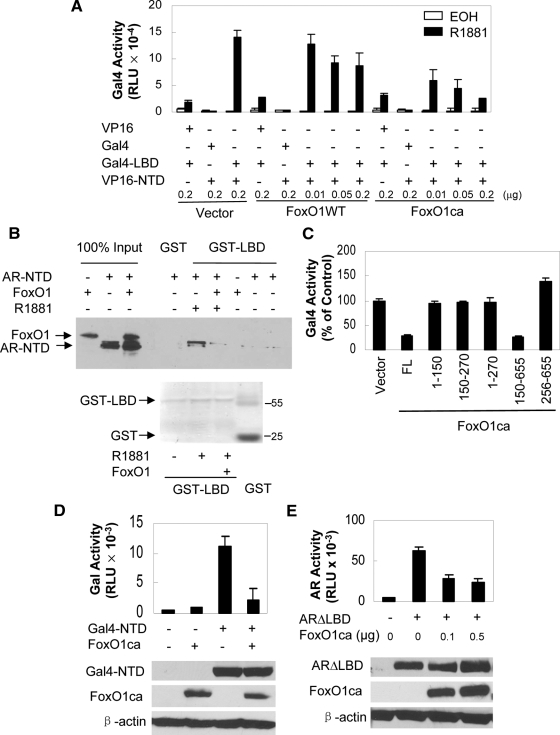

FoxO1 inhibits AR N/C interaction and negates the positive effect of p160 SRCs on AR transcriptional activity by blocking their recruitment to AR NTD

Our previous studies showed that FoxO1 interacted with both the NTD and LBD of the AR (13), raising the possibility that FoxO1 may inhibit AR activity by disrupting the N/C interaction. Accordingly, we tested the effect of FoxO1 on AR N/C interaction in a mammalian two-hybrid assay. As shown in Fig. 4A, cotransfection of AR LBD fused to Gal4 DBD (Gal4-LBD) and AR NTD fused to the VP16 AD (VP16-NT) allowed a strong androgen-induced activation of the cotransfected Gal4 reporter gene in PC3 cells, which was inhibited slightly by wild-type FoxO1 and strongly by FoxO1ca in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4A). Wild-type FoxO1 or FoxO1ca did not decrease the activity of the Gal4 reporter in cells expressing VP16-NT or Gal4-LBD alone or in cells expressing both but treated with vehicle (Fig. 4A). In agreement with the two-hybrid data, glutathione-S-transferase (GST) pull-down assays showed that the ability of androgen-bound GST-LBD to precipitate the in vitro-translated AR-NTD protein in test tube reactions was suppressed by FoxO1 (Fig. 4B). These data suggest that one mechanism by which active FoxO1 inhibits the transcriptional activity of AR is to disrupt the androgen-induced N/C interaction. Consistent with this idea, the ability of FoxO1 to inhibit AR N/C interaction depended on the protein region aa 150-655 that contains both the forkhead box and the C-terminal AD (Fig. 4C), which both were shown earlier to be required to inhibit AR activity.

Figure 4.

FoxO1 suppresses AR N/C interaction and AR activity associated with the NTD, but not the LBD. A, PC3 cells were transfected with 0.3 μg GalLuc, 0.1 μg pCMVβ, 0.1 μg VP16, PM, PMLBD, or VPARNT together with the indicated amounts of wild-type FoxO1 or FoxO1ca and treated with EOH or R1881 for 24 h. Luciferase activity was normalized with β-gal. B, Magnetic bead-bound GST or GST-ARLBD was incubated in the presence or absence of 10 nm DHT with AR NTD and Flag-FoxO1 proteins produced by in vitro translation. Bound proteins were immunoblotted with antibody against ARNT and reblotted with M2 antibody. Immunoblot of 100% input and Coomassie blue staining of the purified GST-ARLBD and GST recombinant protein were shown as controls. C, PC3 cells were transfected as in panel A but with FoxO1ca fragments as indicated. Cells were treated with R1881 and reporter activity was determined. D, PC3 cells were transfected with 0.3 μg GalARNT, 0.3 μg Galluc, 0.1 μg pCMVβ, and 0.5 μg HA-FoxO1ca (+) or vector (−) as indicated. Luciferase activity was determined 24 h later and normalized with β-gal. The expression of GalARNT, FoxO1ca, and β-actin was detected by immunoblotting with antibodies against ARNT, HA, and β-actin, respectively. E, PC3 cells were transfected with 0.3 μg ARΔLBD, 0.5 μg AREe1bluc, 0.1 μg pCMVβ, and 0.5 μg HA-FoxO1ca (+) or vector (−) as indicated. Reporter activity and protein expressions were determined 24 h later as in panel D. RLU, Relative luciferase units.

The fact that FoxO1 interacted with both NTD and LBD regions of the AR (13) raises the possibility that FoxO1 may inhibit N/C interaction through its action on either the NTD or the LBD. We found that the activity of Gal4-LBD on Gal4 reporter induced by androgens was not decreased by FoxO1ca (Fig. 4A), suggesting that FoxO1 is likely to work through its effect on the NTD to inhibit AR. Consistently, the transcriptional activity, not the level of expression, of the NTD fused to either the Gal4 (Fig. 4D) or its own DBD (Fig. 4E) was inhibited by FoxO1ca. Furthermore, in in vitro GST pull-down assays, androgen-bound GST-LBD did not coprecipitate a detectable amount of FoxO1 protein in the presence of AR NTD (Fig. 4B), indicating that the ability of FoxO1 to bind AR NTD is likely to dominate over its binding to AR-LBD.

It is known that the AF-1 in AR NTD is the predominant interface for the binding of p160 SRCs in the presence of androgens (21,22). If FoxO1 acts through NTD, it is likely to exert a negative effect on the ability of SRCs to increase AR activity. Indeed, ectopic SRC1 expression in 293 cells significantly increased androgen-stimulated transcriptional activity of the AR, which was suppressed by the coexpression of FoxO1ca (Fig. 5A). Parallel Western analyses showed that FoxO1ca decreased the expression of neither SRC1 nor AR (Fig. 5A). These analyses suggest a specific suppressive effect of FoxO1ca on the ability of SRC1 to stimulate AR activity. Similarly, when AIB1 was transfected into LNCaP cells, it increased the transcriptional activity of endogenous AR induced by DHT as expected, which was negated by FoxO1ca in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5B). Studies with transcriptional intermediary factor 2 (data not shown) also yielded similar results as with SRC1.

Figure 5.

FoxO1 antagonizes the positive effect of the p160 coactivators on AR by inhibiting their binding to AR NTD. A, COS-7 cells were transfected with 50 ng AR, 0.5 μg AREe1bluc, and 0.1 μg pSG5-HA-SRC1a together with 0.5 μg HA-FoxO1ca or control vector and treated with EOH or 10 nm R1881. Luciferase activity was determined and normalized with β-gal. The expression of indicated proteins was determined by immunoblotting with antibodies against HA (for SRC1 and FoxO1), AR, or β-actin. B, LNCaP cells were transfected with 0.5 μg p(−286/+28)PBLuc, 0.1 μg pCMVβ, 0.1 μg AIB1, and HA-FoxO1ca at indicated amounts and treated with EOH or 10 nm DHT. Endogenous AR activity was measured. C, COS-7 cells were transfected with 0.3 μg Galluc, 0.1 μg pCMVβ, and 0.1 μg VP16, PM, GalFoxO1ca (aa 150–655), VP16ARNT, ARΔLBD, or GalFoxO1 (aa 1–150) as indicated. Luciferase activity was determined and normalized with β-gal. The expression of indicated proteins was determined by immunoblotting with antibodies against Gal4, ARNT, or β-actin. D, COS-7 cells were transfected with 0.3 μg GalLuc, 0.1 μg pCMVβ, 0.1 μg VP16, PBIND, PBINDAIB1, VPARNT, or VPFoxO1ca, as indicated. Luciferase activity was determined and normalized with β-gal. The expression of indicated proteins was determined by immunoblotting with antibodies against Gal4, FoxO1, ARNT, and β-actin, respectively. E, COS-7 cells were transfected with 0.3 μg GalLuc, 0.1 μg pCMVβ, 0.1 μg VP16, PM, PBINDAIB1, VPARNT, or HA-FoxO1ca as indicated. Luciferase activity was determined and normalized with cognate β-gal activity. F, COS-7 cells were transfected as in panel E but with different FoxO1ca fragments. Luciferase activity was determined and normalized to measure the effect of FoxO1 fragments on the AR-AIB1 interaction. G, Purified GST or GST-ARNT was incubated with in vitro translated HA-SRC1a977-1441 in the presence or absence of Flag-FoxO1. Bound proteins were immunoblotted with anti-HA antibody. Immunoblots of reticulocytic lysates with M2 and HA11 and a picture of Coomassie blue-stained recombinant GST-ARNT and GST were shown as quality controls. RLU, Relative luciferase units.

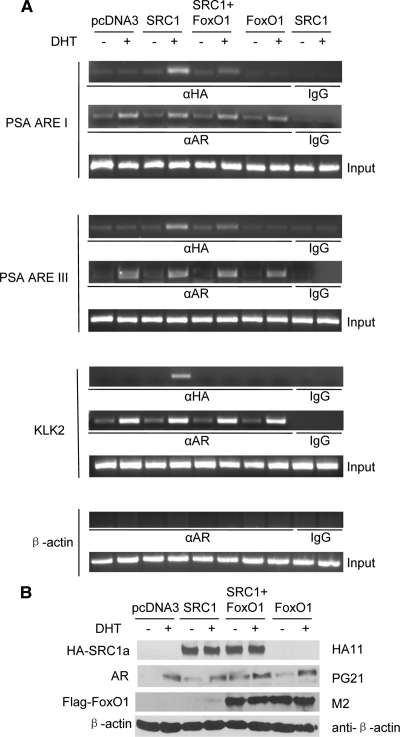

Mammalian two-hybrid assays showed an interaction of the AR NTD with FoxO1ca (aa 150–655) but not with FoxO1 (aa 1–150) that was expressed to a level higher than FoxO1ca (aa 150–655) (Fig. 5C). The increase in GalLuc reporter activity was not due to the enhancement of GalFoxO1ca (aa 150–655) transactivation by AR NTD because ARΔLBD, which contains the NTD but is not fused to VP16, did not increase the reporter activity. Similar two-hybrid assays showed that FoxO1ca did not interact with AIB1 (Fig. 5D) but suppressed its interaction with the AR NTD (Fig. 5E). In agreement with the results from AR transcriptional assays (Fig. 3, B and C) and the N/C interaction studies (Fig. 4A), FoxO1ca (aa 150–655), not other fragments, inhibited the interaction between AIB1 and AR NTD to the same degree as full-length FoxO1ca (Fig. 5F). More importantly, FoxO1 inhibited the ability of in vitro-translated SRC1 to bind to the GST-AR-NTD in test tube reactions (Fig. 5G) and the recruitment of SRC1 to the AREs in the promoter and enhancer of two androgen target genes (Fig. 6A), prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and kallikrein-related peptidase 2 (KLK2), without an effect on the level of the AR or SRC1 expression (Fig. 6B). These data suggest that the suppression of SRC binding to AR NTD, in addition to the suppression of AR N/C interaction, represents a new mechanism for AR inhibition by FoxO1.

Figure 6.

Effect of FoxO1 on the recruitment of SRC1 to the AREs in the promoter and the enhancer regions of AR target genes. A, LNCaP cells were transfected with 3.5 μg HA-SRC1a and 1.5 μg Flag-FoxO1ca and treated with EOH or 10 nm DHT for 2 h. The recruitment of HA-SRC1a and AR to the promoter (ARE I) and the enhancer (ARE III) of the PSA, the promoter of the KLK2 gene, and the promoter of the β-actin were analyzed in ChIP assays with indicated antibodies. B, Cells were transfected as in panel A, and Western blotting analyses were performed with indicated antibodies.

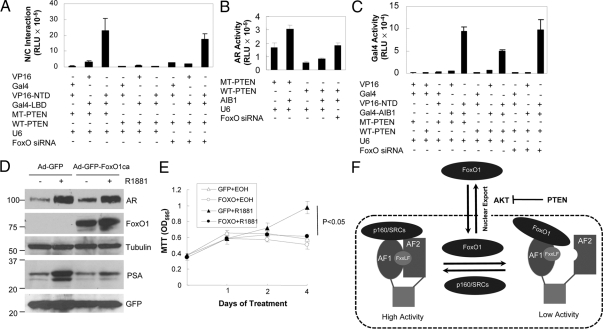

FoxO1 mediates the negative effect of the PTEN on AR N/C interaction and SRC1 binding and suppresses androgen-induced proliferation and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) expression in PCa cells

So far, we have demonstrated that FoxO1 mediated the negative effect of PTEN on AR transcriptional activity and interfered with AR N/C interaction as well as the binding of the p160 coactivators to AR NTD. The next question is whether PTEN inhibits AR activity through the same mechanisms. As shown in Fig. 7A, wild-type PTEN significantly decreased AR N/C interaction induced by androgen treatment in PC3 cells as compared with phosphatase-inactive PTEN. More importantly, FoxO siRNA negated the majority of the suppressive effect exerted by PTEN. Similar to the AR N/C interaction, the ability of AIB1 to increase AR transcriptional activity (Fig. 7B) and the interaction between AIB1 and AR NTD (Fig. 7C) was suppressed by wild-type PTEN, which was partially relieved by FoxO siRNA. At the same dose, PTEN did not decrease basal GalLuc activity or the transcriptional activity of Gal4-AIB1. These data show that PTEN inhibits AR N/C interaction and AIB1 recruitment through FoxO factors.

Figure 7.

Participation of endogenous FoxO factors in PTEN-induced suppression of AR N/C interaction and coactivator recruitment and suppression of AR biological activities in PCa Cells by nuclear FoxO1. A, PC3 cells were transfected with 0.3 μg GalLuc, 0.1 μg pCMVβ, 0.1 μg VP16, PM, PMLBD, or VPARNT, and 0.05 μg WT-PTEN or MT-PTEN together with the indicated amounts of FoxO siRNA or U6 control and treated with 10 nm R1881. AR N/C interaction was determined by measuring the reporter activity. B, PC3 cells were transfected with 0.1 μg pCMVAR, 0.5 μg AREe1bluc, 0.1 μg AIB1, and 0.05 μg MT-PTEN or WT-PTEN together with FoxO siRNA or U6 control. Cells were then treated with 10 nm R1881, and AR activity was determined. C, COS-7 cells were transfected as in panel A except that PMLBD was replaced with PBINDAIB1. The interaction between ARNT and AIB1 was determined as in panel A for AR N/C interaction. D, LNCaP cells were infected for 24 h with 100 multiplicity of infection of Ad-GFP-FoxO1ca or Ad-GFP and treated with EOH or 10 nm R1881 for 24 h. Proteins were detected by immunoblotting with the cognate antibody. E, LNCaP cells were infected and treated for the indicated times as in panel D. Cell growth was determined by the MTT colorimetric assay. Eight samples were analyzed for each data point, and the data were reproduced three times. Statistical analyses were performed with standard Student’s t test. Differences in androgen-induced cell growth between cells infected with control and FoxO1ca virus reached statistical significance (P < 0.05). F, A model depicting the role of FoxO1 in PTEN-induced AR inhibition in prostate cancer cells and its suppression by AKT. The model projects that in prostatic cells a function of nuclear FoxO factors is to suppress the AR N/C interaction and to limit AR activation by p160 coactivators. The negative and positive effects of the coactivators and FoxO factors provide a balance that keeps AR action in check. During prostatic tumorigenesis, loss of PTEN causes cytoplasmic localization of FoxO factors due to increased activity of AKT that phosphorylates FoxO factors. This permits unopposed AR to drive uncontrolled prostate epithelial growth. The model also projects that increased expression or activity of AIB1 or AKT, two known prostatic oncogenes, or reduced expression level or nuclear activity of FoxO factors themselves will have a similar consequence as the loss of PTEN. MT-PTEN, Mutant PTEN; RLU, relative luciferase units; WT-PTEN, wild-type PTEN.

If FoxO1 mediates the inhibition of AR activity and interferes with AR N/C interaction and coactivator recruitment, restoring the expression of active FoxO1 in PTEN-null cells in which endogenous FoxO factors are mainly dislocated to cytosol and degraded should exert a negative effect on the biological activity of endogenous AR. When PTEN-null LNCaP cells were infected, as a control, with a recombinant adenovirus expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) (Ad-GFP), PSA expression was significantly induced by treatment with R1881. In a parallel experiment, infection with a recombinant adenovirus expressing both GFP and FoxO1ca (Ad-GFP-FoxO1ca) significantly decreased androgen induction of PSA expression (Fig. 7D). This inhibition was not due to a decrease in the level of AR protein expression (Fig. 7D). The comparable expression of the GFP proteins in all the lanes shows that the same number of viral particles was used in the studies. Similar to PSA expression, treatment of LNCaP cells infected with control GFP virus with R1881 induced an increase in cell numbers as measured in 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assays. The induction was significantly suppressed (P = 0.0017) in cells infected with Ad-GFP-FoxO1ca (Fig. 7E). These analyses demonstrate that, in PCa cells, the repression of AR transcriptional activity by FoxO1 can be translated into the impaired biological actions of androgens through endogenous AR.

Discussion

As discussed earlier, loss of the PTEN tumor suppressor is an important event during human prostatic tumorigenesis. Our previous studies identified PTEN protein as an AR suppressor that opposes androgen actions in prostate cells through AKT inhibition (12). The present studies provide multiple lines of evidence to support the mechanism (Fig. 7F) that PTEN acts through nuclear FoxO factors to disrupt AR N/C interaction and coactivator recruitment to AR NTD, resulting in decreased transcriptional activity of the AR and the suppression of androgen action. First, FoxO1 siRNA relieved the inhibition of AR activity by ectopic PTEN in PTEN-null cells and increased AR activity in PTEN-intact cells. Second, the constitutively nuclear FoxO1 inhibited AR activity in a dose-dependent manner in PTEN-null cells whereas wild-type FoxO1 had little effect. Along with our observation that wild-type FoxO1, FOXO3a, and FOXO4 inhibited AR activity in PTEN-intact cells (data not shown), these data suggest that it is the nuclear FoxO factors that inhibit AR activity. Third, nuclear FoxO1 inhibited AR N/C interaction and SRC recruitment to AR NTD and to the AREs of androgen target genes. PTEN exerted a similar effect, which was relieved by FoxO siRNA, suggesting that endogenous FoxO factors inhibit N/C interaction and SRC binding in a manner sensitive to PTEN status. Finally, adenovirus-mediated delivery of nuclear FoxO1 into PTEN-null LNCaP cells suppressed androgen-induced PSA production and cell growth, indicating that the inhibition of the transcriptional activity is likely translatable into suppression of the biological actions of androgens by PTEN and FoxO factors. The model shown in Fig. 7F implies that increased expression or activity of AIB1 or AKT, two known prostatic oncogenes, or decreased expression or nuclear activity of FoxO factors themselves will have a similar consequence on androgen actions in prostate cells as the loss of PTEN. They all expose prostate cells to increased growth stimulation by androgens.

During our investigations, two groups reported the inhibition of AR activity by FoxO1 (23,24). Dong et al. (23) showed the inhibition without describing the underlying mechanism. Fan et al. (24) showed that FoxO1 inhibited AR nuclear localization, subnuclear distribution, and DNA binding and yet detected FoxO1 on the promoter of PSA gene together with the AR. Different from our previous finding that FoxO1 interacted with both AR NTD and the LBD (13), Fan et al. confirmed the androgen-induced interaction with LBD but reported that FoxO1 did not interact with AR NTD, leading to their assumption that the AR inhibition by FoxO1 was due to interaction with AR LBD. It is important to point out that, in their two-hybrid assays, Fan et al. used AR NTD fused to Gal4 DBD as one of the hybrid molecules to show a lack of FoxO1 interaction. Because AR NTD fused to Gal4 DBD strongly activated GalLuc reporter by itself (Fig. 4D), it is difficult to measure protein-protein interactions with this construct in mammalian two-hybrid assays. More importantly, the two-hybrid assays based on AR NTD fused to Gal4 DBD could not separate two opposing activities of FoxO1: the binding that increases the Gal4 reporter activity and the inhibitory effect of FoxO1 on the transcriptional activity associated with AR NTD, which decreases the reporter activity. Using FoxO1ca (aa 150–655) fused to Gal4 DBD and AR NTD fused to VP16 activation domain, we detected a measurable interaction between FoxO1 and AR NTD. Furthermore, we found that transcriptional activity of AR NTD with its own DBD or Gal4 DBD was inhibited by FoxO1ca, whereas the activity of AR LBD fused to Gal4 was neither inhibited by FoxO1ca (Fig. 4A) nor increased by FoxO siRNA (data not shown). In addition to the inhibition of AR activity by FoxO1, our earlier studies showed that androgens inhibited FoxO activity through the AR (13). It remains to be determined whether the FoxO1 interaction with AR LBD is important for the suppression of AR activity by FoxO1 or the suppression of FoxO1 activity by androgens.

Unlike other members of the nuclear hormone receptor family, which usually contain a strong AF-2 in their LBD, the recruitment of p160 SRCs to AR is mediated primarily by the AF-1 domain in the NTD (21,22). The AF-1 is known to exhibit strong constitutive activity, and deletion of the LBD creates a molecule that activates androgen target genes to the same extent as the full-length receptor in the presence of ligand (3,22). Consistent with this scheme, our analyses showed that FoxO1 inhibited p160 SRC recruitment to the AR NTD. Two possible ways could be envisioned for FoxO1 to attenuate the interaction between AR NTD and coactivators. One would involve competition of FoxO1 and SRCs for the AR NTD. Alternatively, FoxO1 squelches the limited coactivators from AR, because both AR and FoxO1 are transcription factors. The observations that FoxO1 did not bind to SRCs, that both FoxO1 and SRCs bound to AR NTD, and that FoxO1 inhibited the binding of SRCs to NTD (Figs. 5 and 6) support the competition instead of the squelching mechanism of action. Our mapping analyses showed that the FoxO1 fragment deleted of the forkhead box lost whereas the DNA-binding deficient FoxO1 mutant retained the ability to inhibit AR (Fig. 3), suggesting that the AR inhibition requires the forkhead box but not the ability of FoxO1 to bind DNA. This is consistent with the competition mechanism. In addition to the forkhead box, the ability of FoxO1 to inhibit AR also requires the C-terminal AD because FoxO1ca (aa 150–537), which contains an intact forkhead box but lacks the AD, inhibited neither AR activity in PC3 cells (Fig. 3B) nor the interaction of AR NTD with SRCs (data not shown). Clearly, neither the N-terminal 1–150 amino acids of FoxO1 nor the putative NR box is required for AR inhibition. Although the exact mechanism underlying the disruption of the interaction between AR NTD and p160 coactivators by FoxO1 remains to be defined, it is interesting to note that FoxO1 has recently been reported to bind core histones in nucleosomes and cause chromatin opening (25). It will be interesting to find out whether the ability of FoxO1 to open chromatin plays any role in the displacement of p160 SRCs from AR target gene promoters.

The AR N/C interaction makes a major contribution to AR transcriptional activity. It influences receptor dimerization and slows down the dissociation of ligand from LBD as well as AR degradation. Mutations that disrupt AR N/C interactions have been linked to androgen-insensitive syndrome (26,27). In addition to the competition with coactivator recruitment to NTD, our data suggest that the disruption of AR N/C interaction is another mechanism underlying the AR inhibition by the PTEN-FoxO axis. It is important to note that coactivator recruitment and N/C interaction are two closely related events. SRC proteins have been reported to interact with both the NTD and the LBD to bridge the N/C interaction (6,28,29), and the efficient recruitment of certain coactivators to the NTD of native AR appears also to require N/C interaction (22). Consistent with the association of the two events, FoxO domains necessary for inhibition of N/C interaction were also required for the interference with coactivator binding. Nevertheless, AR N/C interaction was found not to be always required for the transcriptional activity of the AR because ligands that do not support the interaction still activate AR when used at sufficiently high concentrations, and peptides that block the N/C interaction do not necessarily inhibit AR transcriptional activity (30,31). Mutation in the NTD (I182A/L183A) interfered with the AR N/C interaction and dramatically impaired the activity of full-length AR but had little effect on the intrinsic transcriptional activity associated with the NTD (22). In Fig. 5, we showed that FoxO1 inhibited the activity of AR NTD, which is clearly free of N/C interaction. The data suggest that the effect of FoxO1 on coactivator recruitment does not depend on N/C interaction.

Because PTEN inhibits AKT activity, the function of all AKT substrates is expected to be regulated by PTEN. However, FoxO factors are arguably the best AKT substrates the role of which in mediating PTEN actions has been consistently demonstrated by both genetic and biochemical analyses. Genetic analyses in Caenorrhabitis elegans have shown that Daf-16, the sole worm FoxO factor, acts downstream of PTEN to regulate stress response and longevity (32,33). Similarly, genetic analysis in mice has placed FoxO3a downstream of PTEN in controlling the premature follicular activation (34). Our conclusion that nuclear FoxO proteins serve as the mediator for the suppressive effect of PTEN on the AR is consistent with the observation that AKT is involved in AR inhibition by PTEN (12) but does not directly increase AR activity through receptor phosphorylation at putative AKT sites (35,36). The conclusion is also consistent with the demonstrated synergy between AR and AKT in PCa progression (37).

Based on our initial observation that PTEN inhibited AR activity, we predicted that PTEN deletion would induce prostate tumorigenesis through unopposed action of the AR and contribute to resistance of PCa to androgen ablation therapy (38). This prediction was supported by studies with prostate-specific genetic deletion of PTEN in mice (39) and cell lines (40). The current study argues that the depletion of FoxO factors would have a similar effect on androgen-independent growth of PCa cells. Unlike PTEN expression, which is frequently lost in advanced PCa, multiple FoxO factors are redundantly expressed in PCa cells (41). Therefore, restoring the expression of FoxO factors back to the nucleus through targeted inhibition of PI3K-AKT pathway would offer a possible approach to oppose androgen-AR action and to sensitize PCa to androgen ablation therapy.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids

AREe1bLuc was described in the literature as pPRE/GRE.E1b.LUC (42). pCMVhAR (12), GalLuc (12), Gal-VP16 (12), pSG5L-HA-PTEN:WT (12), pSG5L-HA-PTEN:G129R (12), pCMVβ (13) Flag-FoxO1WT (13), GST (13), GST-ARLBD (13) FoxO siRNA (14) p(−286/+28)PBLuc (17), ARR3TKLuc (19), VP16 rAR (5-538) (43), PMLBD (43), GalARNT (described as pAR4G) (44), ARΔLBD (described as pAR5) (44), PBINDAIB1 (45), GST-ARNT (described as pGEX-2TKARNT) (21) pSG5-HA-SRC1a (21), and pSG5-HA-SRC1a977-1441 (21) have also been described. VP16 and PM vectors are from CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc. (Mountain View, CA). pcDNA3-ARNT was constructed by inserting the BamHI/HindIII AR NTD fragment from GST-ARNT (13) into pcDNA3.1. HA-FoxO1ca was constructed by inserting the BamH1/XbaI fragment from Flag-FoxOca (transcriptional start site) (13) into pcDNA3-HA (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). To construct HA-FoxO1ca (1–150), FoxOca cDNA fragment encoding N-terminal 150 amino acids was amplified by PCR. The sequence is 5′-CGGGGGTCACCGGATCCATGGCCGAGGC-3′ for the upstream primer and 5′-GCGGCGGGACGATCTAGACTAGCGCGGCTGC-3′ for the downstream primer, which generate BamHI and XbaI sites at the 5′- and 3′-ends of the DNA fragment, respectively. The amplified FoxO1 (aa 1–150) fragment was cloned into the BamHI and XbaI sites of pcDNA3.1 hemagglutinin (HA) vector (Invitrogen). HA-FoxO1ca (aa 150–270), HA-FoxO1ca (aa 1–270), HA-FoxO1ca (aa 150–655), HA-FoxO1ca (aa 150–537), HA-FoxO1ca (aa 256–655) were constructed similarly. The sequence of the upstream primer is 5′-CTCGCGGGGCAGGGATCCAAGAGCAGCTCG-3′ for FoxO1ca (aa 150–270), FoxO1ca (aa 150–537), and FoxO1ca (aa 150–655) and 5′-GGAGAAGAGCTGGATCCATGGACAACAAC-3′ for FoxO1ca (aa 256–655). The sequence of the downstream primer is 5′-CTTGGCTCTAGAAGCTCGGCTTCGGCTCTTAG-3′ for FoxO1ca (aa 1–270) and FoxO1ca (aa 150–270), 5′-CGGGCCCTCTAGATCAGCCTGACACC-3′ for FoxO1ca (aa 150–655) and FoxO1ca (aa 256–655) and 5′-CAGGGGTCTAGAACGCCCGTTAACTGCAGATG-3′ for FoxO1ca (aa 150–537). pcDNA3.1-Flag-FoxO1ca-NRmut and HA-FoxO1ca-H215R were generated by site-directed mutagenesis using the QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and confirmed by direct sequencing. FLAG-FoxOca and HA-FoxO1 were used as the templates for mutagenesis. The sequence of primers is 5′-GGACTCTTGAAGGAGTGGCCGACTTCTGACTCTC-3′ (upstream) and 5′-GAGAGTCAGAAGTCGGCCACTCCTTCAAGAGTCC-3′ (downstream) to mutate Leu-462; 5′-CTCTGGAAGGAGTGGCTGACTTCTGACTCTC-3′ (upstream) and 5′-GAGAGTCAGAAGTCAGCCACTCCTTCCAGAG-3′ (downstream) to mutate Leu-465; and 5′-GGAAGAATTCAATTCGTCGTAATCTGTCCCTACAC-3′ (upstream) and 5′-GTGTAGGGACAGATTACGACGAATTGAATTCTTCC- 3′ (downstream) to mutate His-215 in the forkhead box.

Cell culture, transient transfections, and reporter assays

PC3 and COS-7 cells were maintained in DMEM (Life Technologies, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Hyclone Laboratories, Inc., Logan, UT). LNCaP cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies) containing 10% FBS. RWPE-1 cells were maintained in Keratinocyte serum-free medium supplemented with 5 ng/ml human recombinant epidermal growth factor and 0.05 mg/ml bovine pituitary extract (Life Technologies).

For reporter and mammalian two-hybrid assays, cells were plated in six-well plates in medium supplemented with 5% charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum (sFBS) (Hyclone). Cells were transfected 24 h later by Lipofectamine-plus following the Invitrogen protocol. Transfected cells were treated for 24 h with EOH, DHT (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), or R1881 (NEN Life Science Products, Boston, MA) in medium containing 1% sFBS and washed with PBS. Cell lysate was prepared as described elsewhere (12), and luciferase activity was determined using the assay systems from Promega Corp. (Madison, WI) following the company’s protocol. β-Gal activity was determined as previously described (12). Results represent at least three independent experiments performed in duplicate, and error bars show sd values.

Immunoblotting analysis

To determine protein expression, cells transfected in parallel with cells prepared for reporter assays or infected with adenovirus were lysed in modified radioimmune precipitation assay buffer containing 50 mm Tris (pH. 7.4), 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1 mm Na3VO4, 1 mm NaF, and protease inhibitor mixture (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA). The lysate was separated on an 8% or 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was probed with antibodies for AR (PG21; Upstate Biotechnology, Inc., Billerica, MA), ARNT (sc-7305; Santa Cruz Biotechnolog, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA), FoxO1 (H-128, Santa Cruz), Gal4 DBD (Santa Cruz), PTEN (Santa Cruz), HA (HA11; Berkeley Antibody Laboratories, Berkeley, CA), Flag (M2, Sigma), β-actin (Sigma), PSA (Santa Cruz), and GFP (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), and bands were visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence as described (12).

GST pull-down assays

AR NTD and HA-SRC1aΔ protein were produced by in vitro transcription-coupled translation from pcDNA3-ARNT or pSG5.HA-SRC1a977-1441 with the TNT T7-coupled reticulocyte lysate system (Promega Corp.) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. GST and its fusion proteins were purified (13), and GST pull-down assays were performed (21) as previously described. Bound proteins were extracted from washed beads with hot sodium dodecyl sulfate sample buffer, resolved in an 8% SDS-PAGE gel, and probed with specific antibodies.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays

For ChIP assays, LNCaP cells were starved in RPMI medium supplemented with 5% sFBS for 3 d and transfected with plasmids using Nucleofector Kit (Amaxa, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD), following the vendor’s protocol.

Next, the cells were treated with 10 nm DHT or EOH for 2 h. ChIP assays were performed using a ChIP assay kit (Upstate) as described by Shang et al. (46). Briefly, the cells were treated with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature and sonicated four times for 10 sec each with the power input of the sonicator (Digital Sonifier, model 450; Branson Ultrasonics Corp., Danbury, CT) set at 30%. Immunoprecipitations were performed overnight at 4 C with specific antibodies, followed by incubation with 60 μl of salmon sperm DNA/Protein A agarose slurry for 1 h. Eluted DNA fragments were purified with the QIAquick Spin Kit (QIAGEN, Chatsworth, CA) and amplified by PCR for 35 cycles with primers for AREI (46), AREIII (47), KLK2 (48), and β-actin (46).

Adenovirus infection and colorimetric MTT assay

Recombinant adenovirus expressing GFP-FoxO1TSSA (GFP-FoxO1ca) and GFP control vector were gifts from Dr. J. Milbrandt (49). The recombinant virus was purified on a cesium chloride gradient, titrated, aliquoted, and stored at −80 C. For infections, purified adenovirus was added to LNCaP cells at a 100 multiplicity of infection in RPMI media containing 5% sFBS for 24 h. Infected cells were washed with medium and cultured for 24 h in the same medium containing ethanol or 10 nm R1881 before cell extracts were prepared for immunoblotting analyses.

For MTT assays, LNCaP cells were plated in RPMI 1640 in 96-well plates containing 10% FBS at 5 × 104 cells per well and infected with recombinant adenovirus as described above. Cells were treated with EOH or R1881, and MTT assays were performed as previously described (12). Absorbance at 595 nm (OD595) was determined with a MRX microplate reader (DYNEX Technologies, Chantilly, VA). For each data point, eight samples were analyzed in parallel. The analyses were repeated two times. Statistical analysis was performed using the independent sample t test.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Z. Yuan and A. Bonni for the FoxO siRNA vector; Dr. M. Stallcup for pGEX-2TKARNT, pSG5-HA-SRC1a, and pSG5-HA-SRC1a977–1441; Dr. R. J. Matusik for probasin promoter-based p(−286/+28)PBLuc and ARR3TKLuc AR reporter genes; Dr. C. L. Smith for the AREe1bLuc and pBINDAIB1 vector; Dr. C. Bai for AR mammalian two-hybrid vectors; and Dr. J. Milbrandt for the recombinant FoxO1 adenovirus. The authors also thank Dr. John Tsibris for proofreading the manuscript. Sequence analyses were performed at the Molecular Biology Core Facility of the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Public Health Service Grants CA93666 and CA111334 (to W.B.), Department of Defense Prostate Cancer Grant DAMD17-02-1-0140 (to W.B.), and Grant 06BCBG1 from the Bankhead-Coley Cancer Research Program of the Florida Department of Health (to W.B.).

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online December 12, 2008

Abbreviations: aa, Amino acid; AD, activation domain; Ad-GFP, adenovirus expressing green fluorescent protein; AF-1, activation function 1; AR, androgen receptor; ARE, androgen response element; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; DBD, DNA-binding domain; DHT, dihydrotestosterone; FBS, fetal bovine serum; FoxO, mammalian forkhead subclass O; GST, glutathione-S-transferase; HA, hemagglutinin; LBD, ligand-binding domain; MTT, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide; NTD, N-terminal domain; PCa, prostate cancer; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10; sFBS, charcoal-stripped FBS; siRNA, small interfering RNA; SRC, steroid receptor coactivator.

References

- Boring CC, Squires TS, Tong T 1993 Cancer statistics, 1993. CA Cancer J Clin 43:7–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai MJ, O'Malley BW 1994 Molecular mechanisms of action of steroid/thyroid receptor superfamily members. Annu Rev Biochem 63:451–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenster G, van der Korput HA, van Vroonhoven C, van der Kwast TH, Trapman J, Brinkmann AO 1991 Domains of the human androgen receptor involved in steroid binding, transcriptional activation, and subcellular localization. Mol Endocrinol 5:1396–1404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He B, Kemppainen JA, Wilson EM 2000 FXXLF and WXXLF sequences mediate the NH2-terminal interaction with the ligand binding domain of the androgen receptor. J Biol Chem 275:22986–22994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley E, Zhou ZX, Wilson EM 1995 Evidence for an anti-parallel orientation of the ligand-activated human androgen receptor dimer. J Biol Chem 270:29983–29990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikonen T, Palvimo JJ, Janne OA 1997 Interaction between the amino- and carboxyl-terminal regions of the rat androgen receptor modulates transcriptional activity and is influenced by nuclear receptor coactivators. J Biol Chem 272:29821–29828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HJ, Chang C 2003 Recent advances in androgen receptor action. Cell Mol Life Sci 60:1613–1622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stambolic V, Mak TW, Woodgett JR 1999 Modulation of cellular apoptotic potential: contributions to oncogenesis. Oncogene 18:6094–6103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali IU, Schriml LM, Dean M 1999 Mutational spectra of PTEN/MMAC1 gene: a tumor suppressor with lipid phosphatase activity. J Natl Cancer Inst 91:1922–1932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer EL, Brunet A 2005 FOXO transcription factors at the interface between longevity and tumor suppression. Oncogene 24:7410–7425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy P, Liu L, Adhikari D, Jagarlamudi K, Rajareddy S, Shen Y, Du C, Tang W, Hamalainen T, Peng SL, Lan ZJ, Cooney AJ, Huhtaniemi I, Liu K 2008 Oocyte-specific deletion of Pten causes premature activation of the primordial follicle pool. Science 319:611–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Nicosia SV, Bai W 2001 Antagonism between PTEN/MMAC1/TEP-1 and androgen receptor in growth and apoptosis of prostatic cancer cells. J Biol Chem 276:20444–20450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Lee H, Guo S, Unterman TG, Jenster G, Bai W 2003 AKT-independent protection of prostate cancer cells from apoptosis mediated through complex formation between the androgen receptor and FKHR. Mol Cell Biol 23:104–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehtinen MK, Yuan Z, Boag PR, Yang Y, Villen J, Becker EB, DiBacco S, de la Iglesia N, Gygi S, Blackwell TK, Bonni A 2006 A conserved MST-FOXO signaling pathway mediates oxidative-stress responses and extends life span. Cell 125:987–1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramaswamy S, Nakamura N, Vazquez F, Batt DB, Perera S, Roberts TM, Sellers WR 1999 Regulation of G1 progression by the PTEN tumor suppressor protein is linked to inhibition of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:2110–2115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bello D, Webber MM, Kleinman HK, Wartinger DD, Rhim JS 1997 Androgen responsive adult human prostatic epithelial cell lines immortalized by human papillomavirus 18. Carcinogenesis 18:1215–1223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Gao N, Kasper S, Reid K, Nelson C, Matusik RJ 2004 An androgen-dependent upstream enhancer is essential for high levels of probasin gene expression. Endocrinology 145:134–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao HH, Herrera RE, Coronado-Heinsohn E, Yang MC, Ludes-Meyers JH, Seybold-Tilson KJ, Nawaz Z, Yee D, Barr FG, Diab SG, Brown PH, Fuqua SA, Osborne CK 2001 Forkhead homologue in rhabdomyosarcoma functions as a bifunctional nuclear receptor-interacting protein with both coactivator and corepressor functions. J Biol Chem 276:27907–27912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper S, Rennie PS, Bruchovsky N, Lin L, Cheng H, Snoek R, Dahlman-Wright K, Gustafsson JA, Shiu RP, Sheppard PC, Matusik RJ 1999 Selective activation of the probasin androgen-responsive region by steroid hormones. J Mol Endocrinol 22:313–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramaswamy S, Nakamura N, Sansal I, Bergeron L, Sellers WR 2002 A novel mechanism of gene regulation and tumor suppression by the transcription factor FKHR. Cancer Cell 2:81–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H, Hong H, Huang SM, Irvine RA, Webb P, Kushner PJ, Coetzee GA, Stallcup MR 1999 Multiple signal input and output domains of the 160-kilodalton nuclear receptor coactivator proteins. Mol Cell Biol 19:6164–6173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alen P, Claessens F, Verhoeven G, Rombauts W, Peeters B 1999 The androgen receptor amino-terminal domain plays a key role in p160 coactivator-stimulated gene transcription. Mol Cell Biol 19:6085–6097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong XY, Chen C, Sun X, Guo P, Vessella RL, Wang RX, Chung LW, Zhou W, Dong JT 2006 FOXO1A is a candidate for the 13q14 tumor suppressor gene inhibiting androgen receptor signaling in prostate cancer. Cancer Res 66:6998–7006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan W, Yanase T, Morinaga H, Okabe T, Nomura M, Daitoku H, Fukamizu A, Kato S, Takayanagi R, Nawata H 2007 Insulin-like growth factor 1/insulin signaling activates androgen signaling through direct interactions of Foxo1 with androgen receptor. J Biol Chem 282:7329–7338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatta M, Cirillo LA 2007 Chromatin opening and stable perturbation of core histone:DNA contacts by FoxO1. J Biol Chem 282:35583–35593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J, Saatcioglu F, Janne OA, Palvimo JJ 2001 Disrupted amino- and carboxyl-terminal interactions of the androgen receptor are linked to androgen insensitivity. Mol Endocrinol 15:923–935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghali SA, Gottlieb B, Lumbroso R, Beitel LK, Elhaji Y, Wu J, Pinsky L, Trifiro MA 2003 The use of androgen receptor amino/carboxyl-terminal interaction assays to investigate androgen receptor gene mutations in subjects with varying degrees of androgen insensitivity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88:2185–2193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen HC, Buchanan G, Butler LM, Prescott J, Henderson M, Tilley WD, Coetzee GA 2005 GRIP1 mediates the interaction between the amino- and carboxyl-termini of the androgen receptor. Biol Chem 386:69–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu CL, Chen YL, Ting HJ, Lin WJ, Yang Z, Zhang Y, Wang L, Wu CT, Chang HC, Yeh S, Pimplikar SW, Chang C 2005 Androgen receptor (AR) NH2- and COOH-terminal interactions result in the differential influences on the AR-mediated transactivation and cell growth. Mol Endocrinol 19:350–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CY, McDonnell DP 2002 Evaluation of ligand-dependent changes in AR structure using peptide probes. Mol Endocrinol 16:647–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemppainen JA, Langley E, Wong CI, Bobseine K, Kelce WR, Wilson EM 1999 Distinguishing androgen receptor agonists and antagonists: distinct mechanisms of activation by medroxyprogesterone acetate and dihydrotestosterone. Mol Endocrinol 13:440–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen PL, Albert PS, Riddle DL 1995 Genes that regulate both development and longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 139:1567–1583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogg S, Ruvkun G 1998 The C. elegans PTEN homolog, DAF-18, acts in the insulin receptor-like metabolic signaling pathway. Mol Cell 2:887–893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castrillon DH, Miao L, Kollipara R, Horner JW, DePinho RA 2003 Suppression of ovarian follicle activation in mice by the transcription factor Foxo3a. Science 301:215–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nan B, Snabboon T, Unni E, Yuan XJ, Whang YE, Marcelli M 2003 The PTEN tumor suppressor is a negative modulator of androgen receptor transcriptional activity. J Mol Endocrinol 31:169–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gioeli D, Ficarro SB, Kwiek JJ, Aaronson D, Hancock M, Catling AD, White FM, Christian RE, Settlage RE, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Weber MJ 2002 Androgen receptor phosphorylation. Regulation and identification of the phosphorylation sites. J Biol Chem 277:29304–29314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin L, Teitell MA, Lawson DA, Kwon A, Mellinghoff IK, Witte ON 2006 Progression of prostate cancer by synergy of AKT with genotropic and nongenotropic actions of the androgen receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:7789–7794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taplin ME, Balk SP 2004 Androgen receptor: a key molecule in the progression of prostate cancer to hormone independence. J Cell Biochem 91:483–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Gao J, Lei Q, Rozengurt N, Pritchard C, Jiao J, Thomas GV, Li G, Roy-Burman P, Nelson PS, Liu X, Wu H 2003 Prostate-specific deletion of the murine Pten tumor suppressor gene leads to metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer Cell 4:209–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao J, Wang S, Qiao R, Vivanco I, Watson PA, Sawyers CL, Wu H 2007 Murine cell lines derived from Pten null prostate cancer show the critical role of PTEN in hormone refractory prostate cancer development. Cancer Res 67:6083–6091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paik JH, Kollipara R, Chu G, Ji H, Xiao Y, Ding Z, Miao L, Tothova Z, Horner JW, Carrasco DR, Jiang S, Gilliland DG, Chin L, Wong WH, Castrillon DH, DePinho RA 2007 FoxOs are lineage-restricted redundant tumor suppressors and regulate endothelial cell homeostasis. Cell 128:309–323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawaz Z, Lonard DM, Smith CL, Lev-Lehman E, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ, O'Malley BW 1999 The Angelman syndrome-associated protein, E6-AP, is a coactivator for the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily. Mol Cell Biol 19:1182–1189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powzaniuk M, McElwee-Witmer S, Vogel RL, Hayami T, Rutledge SJ, Chen F, Harada S, Schmidt A, Rodan GA, Freedman LP, Bai C 2004 The LATS2/KPM tumor suppressor is a negative regulator of the androgen receptor. Mol Endocrinol 18:2011–2023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenster G, van der Korput HA, Trapman J, Brinkmann AO 1995 Identification of two transcription activation units in the N-terminal domain of the human androgen receptor. J Biol Chem 270:7341–7346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutertre M, Smith CL 2003 Ligand-independent interactions of p160/steroid receptor coactivators and CREB-binding protein (CBP) with estrogen receptor-α: regulation by phosphorylation sites in the A/B region depends on other receptor domains. Mol Endocrinol 17:1296–1314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang Y, Myers M, Brown M 2002 Formation of the androgen receptor transcription complex. Mol Cell 9:601–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louie MC, Yang HQ, Ma AH, Xu W, Zou JX, Kung HJ, Chen HW 2003 Androgen-induced recruitment of RNA polymerase II to a nuclear receptor-p160 coactivator complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:2226–2230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wissmann M, Yin N, Muller JM, Greschik H, Fodor BD, Jenuwein T, Vogler C, Schneider R, Gunther T, Buettner R, Metzger E, Schule R 2007 Cooperative demethylation by JMJD2C and LSD1 promotes androgen receptor- dependent gene expression. Nat Cell Biol 9:347–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modur V, Nagarajan R, Evers BM, Milbrandt J 2002 FOXO proteins regulate tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis inducing ligand expression. Implications for PTEN mutation in prostate cancer. J Biol Chem 277:47928–47937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]