Abstract

Objective

Association of mirror movements with special kinds of neural tube defects, particularly cranial dermal sinus and cervical myelomeningocele, is extremely rare. We have tried to explain the probable pathophysiology underlying this rare condition.

Clinical presentation

Two cases are presented. Case 1: A right-handed 3-year-old boy brought to the outpatient clinic for evaluation of mirror movement had been operated on at 10 days of age to repair a cervical myelomeningocele. At examination, mirror movements were observed on both sides. Case 2: A right-handed 7-year-old boy referred for vertigo and occasional vomiting since 3 months of age. The mirror movements were present in the upper extremities, and reportedly had existed since early childhood. Brain magnetic resonance imaging disclosed the dermal sinus, tract, and midline dermoid tumor.

Conclusion

To describe a meaningful association between mirror movements and congenital abnormalities in 2 cases reported here, we propose development of an abnormality in the cervical spinal cord (case 1) and cervicomedullary junction (case 2) associated with gross anomalies in the affected areas.

Keywords: cervical myelomeningocele, mirror movement, occipital dermal sinus

Introduction

Mirror movements are involuntary, non-suppressible movements of the contralateral upper limb, which occur during unilaterally intended voluntary movement. This pathological condition is seen in the great majority of the X-linked form of Kallmann’s syndrome, occasionally in the Klippel–Feil syndrome, and in the agenesis of the corpus callosum (Royal et al 2000; Erdincler 2002; Erol et al 2004; Tubbs et al 2004). However, association of mirror movements with special kinds of neural tube defects, particularly cranial dermal sinus and cervical myelomeningocele, is extremely rare. Here we try to explain the probable pathophysiology underlying this rare condition. These two cases could provide further evidence of other etiological causes of mirror movements.

Case reports

Case 1

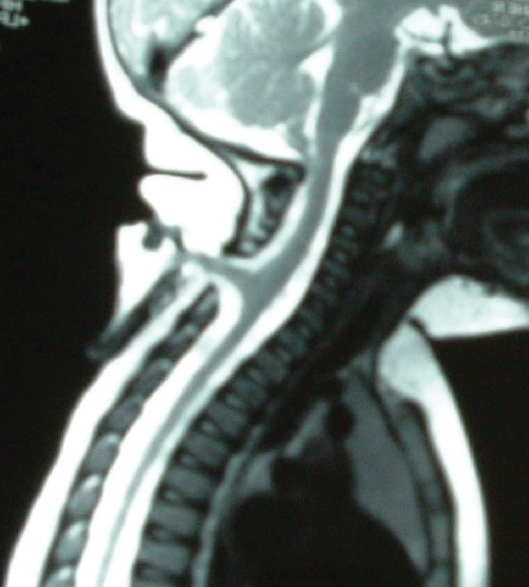

A right-handed 3-year-old boy was brought to the outpatient clinic for evaluation of mirror movement. He has been operated on at 10 days of age in our hospital to repair a cervical myelomeningocele with a neurofibrovascular stalk extending from dorsal aspect of cervical cord to the top of the sac (Figure 1). The operation was uneventful.

Figure 1.

Spinal magnetic resonance imaging of patient (case 1) before operation shows cervical myelomeningocele in which the neurofibrovascular stalk extends from the dorsal aspect of the cervical cord to the top of sac.

At examination, we observed mirror movements on both sides, including the involuntary reproduction of the contralateral motor activities, which involved only the distal parts of the upper limbs. Whenever he was asked to move his hand or finger on one side he showed marked involuntary movement on the opposite side. His mother claimed that he had mirror movements limited to the upper extremities since early childhood.

Physical examination revealed that he was in good health. He was continent of both bowel and bladder without long tract signs and sensory problems. Further neurologic exam was normal except for the vivid mirror movements. Now he is 6 years old and mirror movement is persistent without major disturbance in his daily life.

Case 2

The patient was a right-handed 7-year-old boy referred for vertigo and occasional vomiting since 3 months of age. Careful evaluation disclosed a small hairy dimple at the occipital area. The mirror movements were present in the upper extremities, produced with involuntary movements of the contralateral upper extremity with ipsilateral volitional movement. His neurologic exam was normal except for right sixth nerve paresis. Mirror movement reportedly existed since early childhood.

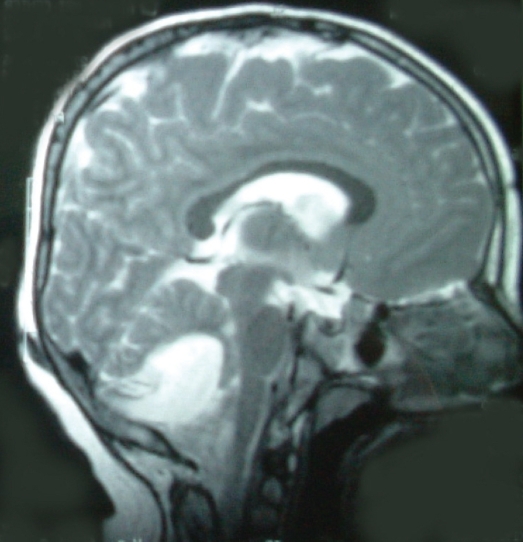

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) disclosed the dermal sinus, tract, and midline dermoid tumor (Figure 2). There were no other abnormalities on the cranial MRI. A suboccipital craniectomy was performed: a dermal sinus tract was followed until its end and excised along with the midline dermoid tumor. The postoperative course was uneventful. Pathological examination confirmed preoperative diagnosis. The symptoms of vertigo and vomiting were immediately improved, but his mirror movements persisted postoperatively.

Figure 2.

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (T2 weighted image, sagittal view) of case 2 demonstrates the occipital dermal sinus, inracranial sinus tract, and midline posterior fossa cystic mass.

Discussion

Mirror movements are defined as associated or synkinetic movements executed involuntarily on one side of the body in response to an intentionally performed movement in the corresponding contralateral muscle group or limb. Mirror movements have been observed in normal children up to 10 years of age and tend to affect the hands, although the entire upper extremity and, rarely, even the legs can be involved. They tend to affect homologous specific muscles, although isolated reports of index finger flexion causing contralateral triceps movement and arm motion affecting the opposite arm and both legs have been presented (Royal et al 2000; Tubbs et al 2004).

Mirror movements have been classified into three general categories: a physiologic form often present at birth, which rapidly disappears with myelination and neurologic maturation, not thought to persist beyond 10 years; a hereditary form, predominantly autosomal dominant, although sporadic and recessive forms have been reported (usually milder but otherwise clinically indistinguishable from other forms); and a pathologic form, associated with various entities including agenesis of the corpus callosum, basilar invagination of the skull, spina bifida occulta, Friedrich’s ataxia, Kallmann’s syndrome, Usher’s syndrome, phenylketonuria, congenital hemiparesis, diabetes insipidus, mental retardation, schizophrenia, and extrapyramidal system disease (Tubbs et al 2004). However, very rarely mirror movements have been found associated with the cervical meningocele and dermal sinus. Erdincler (2002) and Erol and colleagues (2004) have reported an association between the cervical dermal sinus tract and mirror movements. Royal and colleagues (2000) reported a strong association between cervicomedullary neuroschisis and mirror movements in cases of Kilppel Fiel syndrome. They showed mirror movements occurred only when fusion involved more than one vertebral level and, more commonly, when there was extensive vertebral fusion (Royal et al 2000).

In a comprehensive MEDLINE search from 1970 to April 2007, we found only two cases reporting direct association between cervical meningocele and mirror movements (Odabasi et al 1998; Erdincler 2002). To the best of our knowledge, no association between occipital dermal sinus and mirror movement has been reported.

In cervical myelomeningocele a band of tissue extends from the posterior part of the cervical cord to the dura mater and lamina. There is usually a single band, extending in the midline to the base of the sac (Erol et al 2004). Patients experience progressive neurological deterioration due to untreated tethered cervical cord. The ensuing neurological deficits are disabling, and affect mainly the fine motor functions of the hands (Habibi et al 2006).

Occipital dermal sinuses are rare dysraphic lesions that result from defective separation of the ectoderm and neuro-ectoderm during the 3rd to 5th weeks of gestation (Farmer 2005). These benign lesions are usually discovered along with recurrent meningitis, cerebellar abscess, or a cutaneous opening infection and are treated soon after diagnosis because of potentially life-threatening complications (Ansari et al 2006). Abnormalities that coexist with dermal sinus tracts include intradural dermoid tumors, meningocele, and myelomeningocele, besides various kinds of associated skin lesions (Erol et al 2004).

Many hypotheses concerning the cause of mirror movements have been described. The hypothesis related to spinal origin for mirror movements varied from activity in the ipsilateral corticospinal tract (Mayston et al 1997) to deficiency in the pyramidal decussation causing development of alternative, less specific pathways (Krams et al 1999), abnormal ipsilateral and bilateral fast conducting corticospinal projections with abnormal common presynaptic input (Farmer et al 1990; Farmer 2005; Marcelo et al 2006), and a loss of inhibition of contralateral crossed projections, rather than from a loss of inhibition of the ipsilateral uncrossed pathway (Nass 1985; Aranyi and Rosler 2002; Marcelo et al 2006).

To describe a meaningful association between mirror movements and congenital abnormalities in the two cases reported here, we propose development of an abnormality in the cervical spinal cord (case 1) and the cervicomedullary junction (for case 2), associated with gross anomalies in the affected areas. Associated with an abnormal neuro fibrovascular bundle extending from the cervical cord to the dome of the myelomeningocele sac in case one, some abnormal neural pathways between the corticospinal tract and motor neuron may have existed that contributed to mirror movement. Abnormal organization of motor pathways at the cervicomedullary junction causing anomalous pyramidal decussation can be an acceptable mechanism for case 2.

Conclusion

A very rare association of mirror movement with cervical myelomeningocele and occipital dermal sinus has been presented. Development of an abnormality in the cervical spinal cord and cervicomedullary junction associated with gross anomalies in the affected areas is thought to have caused this abnormal movement. Some abnormal neural pathways between the corticospinal tract and motor neuron may have existed that contributed to mirror movement in the cervical myelomeningocele case. Abnormal organization of motor pathways at the cervicomedullary junction causing anomalous pyramidal decussation can explain mirror movement in the patient with occipital dermal sinus.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Ansari S, Dadmehr M, Nejat F. Possible genetic correlation of an occipital dermal sinus in a mother and son. J Neurosurg Pediatrics. 2006;105:326–8. doi: 10.3171/ped.2006.105.4.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aranyi Z, Rosler KM. Effort-induced mirror movements, a study of transcallosal inhibition in humans. Exp Brain Res. 2002;145:76–82. doi: 10.1007/s00221-002-1101-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdincler P. Cervical cord tethering and congenital mirror movements: is it an association rather than a coincidence? Br J Neurosurg. 2002;16:519–22. doi: 10.1080/026886902320909196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erol FS, Topsakal C, Ozveren MF, et al. Meningocele with cervical dermoid sinus tract presenting with congenital mirror movement and recurrent meningitis. Yonsei Medical Journal. 2004;45:568–72. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2004.45.3.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer SF, Ingram DA, Stephens JA. Mirror movements studies in a patient with Klippel-Feil syndrome. J Physiol. 1990;428:467–84. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer SF. Mirror movements in neurology. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:1330. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.069625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habibi Z, Nejat F, Tajik P, et al. Cervical myelomeningocele. Neurosurgery. 2006;58:1168–75. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000215955.18762.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krams M, Quinton R, Ashburner J, et al. Kallmann’s syndrome: mirror movements associated with bilateral corticospinal tract hypertrophy. Neurology. 1999;52:816–22. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.4.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcelo M, Carpintiero S, Meli F, et al. Bilateral mirror writing movements (mirror dystonia) in a patient with writer’s cramp: functional correlates. Mov Disord. 2006;21:683–9. doi: 10.1002/mds.20736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayston MJ, Harrison LM, Quinton R, et al. Mirror movements in X-linked Kallmann’s syndrome.1. A neurophysiological study. Brain. 1997;120:1199–16. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.7.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nass R. Mirror movement asymmetries in congenital hemiparesis: the inhibition hypothesis revisited. Neurology. 1985;35:1059–62. doi: 10.1212/wnl.35.7.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odabasi Z, Gökçil Z, Kütükçü Y, et al. Mirror movements associated with cervical meningocele: case report. Minim Invas Neurosurg. 1998;41:99–100. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1052026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royal SA, Tubbs S, D’Antonio MG, et al. Investigation into the association between cervicomedullary neuroschisis and with mirror movements in patients with Klippel-Feil syndrome. Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;23:724–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tubbs RS, Smyth MD, Dure LS, et al. Exclusive lower extremity mirror movements and diastematomyelia. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2004;40:132–5. doi: 10.1159/000079856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]