Abstract

We tested the hypothesis that GnRH, PGE2 and db-cAMP act via the nitric oxide (NO)-cGMP and MAPK pathways to facilitate estrous behavior (lordosis and proceptivity) in estradiol-primed female rats. Estradiol-primed rats received intracerebroventricular (icv) infusions of pharmacological antagonists of NO synthase (L-NAME), NO-dependent soluble guanylyl cyclase (ODQ), protein kinase G (KT5823), or the ERK1/2 inhibitor PD98059 15 min before icv administration of 50 ng of GnRH, 1 μg of PGE2 or 1 μg of db-cAMP. Icv infusions of GnRH, PGE2 and db-cAMP enhanced estrous behavior at 1 and 2 hr after drug administration. Both L-NAME and ODQ blocked the estrous behavior induced by GnRH, PGE2 and db-cAMP at some of the times tested. The protein kinase G inhibitor KT5823 reduced PGE2 and db-cAMP facilitation of estrous behavior but did not affect the behavioral response to GnRH. In contrast, PD98059 blocked the estrous behavior induced by all three compounds. These data support the hypothesis that the NO-cGMP and ERK/MAPK pathways are involved in the lordosis and proceptive behaviors induced by GnRH, PGE2 and db-cAMP. However, cGMP mediation of GnRH-facilitated estrous behavior is independent of protein kinase G.

Keywords: NO, MAPK, Estrous behavior, GnRH, PGE2, cAMP

1. INTRODUCTION

A number of endogenous signaling molecules, including gonadotropin hormone releasing hormone (GnRH), prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and cyclic AMP (cAMP), can substitute for progesterone (P) to facilitate lordosis behavior in ovariectomized (OVX) rats primed with estradiol (E2) [1–9]. The cellular mechanism through which these compounds induce female sexual behavior in rats is unclear. The temporal characteristics of the responses induced by these agents, e.g., latency to display lordosis, are similar to those of P, suggesting a common mechanism of action [see 7, 8, 10, 11, 12]. There is also evidence that these agents facilitate estrous behavior (lordosis and proceptive behaviors) by activating the progestin receptor (PR), because administration of the PR antagonist RU486 blocks the lordosis and proceptivity induced by all of these agents [11].

A number of second messengers, including nitric oxide (NO), also play an important role in the activation of sexual behavior in female rats treated with E2 and P [13–16]. We recently found that the NO pathway participates in the induction of female sexual behavior by P, its ring A-reduced metabolites, and by vaginocervical stimulation [17, 18]. NO synthase (NOS) is expressed in diverse hypothalamic areas [19–21] and in the pituitary lobes [22–26] where it can be regulated by E2, raising the possibility that NO may act in both the brain and pituitary as a neuroendocrine regulator of reproductive function. For example, NO acts as a signal transducer in norepinephrine-induced PGE2 release from hypothalamic explants [27]. Both norepinephrine and PGE2 regulate the pulsatile release of GnRH and participate in the preovulatory GnRH/LH surge [27–29]. Thus the NO system may participate in the regulation of GnRH release as well as in female sexual behavior.

The second messenger cAMP has also been implicated in neuroendocrine control of reproductive function. GnRH acting on GnRH type 1 receptors and PGE2 acting on its receptors associate with Gαs, which activates the adenylyl cyclase-cAMP-protein kinase A (PKA) cascade [30–32]. Administration of cAMP systemically or directly into the brain facilitates lordosis behavior in E2-primed rats [10, 11, 33–38]. Mani et al. [36] also found that a PKA blocker decreased the facilitatory effect of P on lordosis behavior of OVX, E2-treated rats. Similarly, we reported recently that intracerebroventricular (icv) injections of Rp-cAMPS, a PKA inhibitor, significantly depressed both lordosis and proceptive responses induced by GnRH, PGE2 and db-cAMP [38]. Thus, these agents can also use the cAMP-PKA signaling pathway to elicit their stimulating effect on estrous behavior in rats.

Other intracellular signaling pathways, such as protein kinase G (PKG) [13, 15, 17, 34, 39, 40], mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) [40–42] and protein kinase C [43–45], have also been implicated in the expression of estrous behavior in OVX, E2-primed rats. For example, administration of KT5823, an inhibitor of PKG, or PD98059, an inhibitor of the extracellular signal regulated kinase (ERK) family of MAPKs, blocked estrous behavior induced by P and ring A-reduced progestins [17, 40] or by vaginocervical stimulation [46]. Interestingly, GnRH and PGE2 can activate several of these pathways in different cell lines [47, 48]. GnRH activates phospholipases D and A2 [49, 50], produces cGMP [51, 52] and under some circumstances, activates tyrosine kinases and the MAPK cascade [53, 54]. PGE2 also binds to distinct receptors to induce either activation of the MAPK pathway via Gαq or Gαi or to increase cAMP synthesis and subsequently activation of PKA [32, 55].

The goal of the present studies was to determine whether the NO, PKG and ERK/MAPK intracellular signaling pathways, which have been implicated in progestin facilitation of estrous behavior, also play a role in the facilitation of female reproductive behaviors by GnRH, PGE2 and cAMP. In the Experiment 1, we used inhibitors of NOS and soluble guanylyl cyclase to explore if the NO pathway is indispensable for GnRH, PGE2 and db-cAMP stimulation of estrous behavior. In Experiment 2, we assessed the possible role of PKG and ERK1/2 in the estrous-facilitating action of GnRH, PGE2 and cAMP by administering KT5823, a potent blocker of PKG, and PD98059, a potent blocker of ERK1/2.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Animals

A total of 171 animals were used in this study. Animals were sexually inexperienced female Sprague Dawley rats (240–280 g) bred in our colony. They were kept at 23 ± 2°C with a reversed light–dark cycle (14 h light, 10 h dark, lights on at 2300 h). They were fed with Purina rat chow and water ad libitum. Animal care and all the experimental procedures adhered to the Mexican Law for the Protection of Animals.

2.2. Surgical procedures

Females were bilaterally OVX under ether anesthesia, injected with penicillin (22,000 I.U./kg) and housed 4 females per cage. Two weeks later, they were anesthetized with xylazine (4 mg/kg) and ketamine (80 mg/kg) and placed in a Kopf stereotaxic instrument (Tujunga, CA). Females were implanted with a stainless steel cannula (22 gauge, 17 mm long) in the right lateral ventricle using the following coordinates: A/P +0.80 mm, M/L −1.5 mm, D/V −3.5 mm with respect to bregma [56]. A stainless steel screw was fixed to the skull, and both the cannula and screw were attached to the bone with dental cement. An insert cannula (30 gauge) provided with a cap was introduced into the guide cannula to prevent clogging and contamination.

2.3. Hormone and inhibitor treatment

One week after cannula implantation, all females received a sc injection of 5 μg of E2 benzoate (E2B; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). About 40 hr later, they received icv infusion of vehicle or one of the following inhibitors: the NOS inhibitor, NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME), the specific inhibitor of soluble guanylyl cyclase, 1H-[1, 2, 4] oxadiazolo[4, 3-a]quinoxalin-1-one (ODQ), the PKG inhibitor KT5823, or the ERK1/2 inhibitor, PD98059. Fifteen min after infusion of vehicle or inhibitors, vehicle, GnRH, PGE2 or db-cAMP were administered by icv infusion. GnRH, PGE2, db-cAMP and L-NAME were prepared in sterile saline; ODQ, KT5823 and PD98059 were prepared in 10% DMSO. All agents were infused in a volume of 1 μl into the right lateral ventricle through the guide cannula over 1 min, and another 1 min was allowed for drug diffusion before the removal of the infusion needle. L-NAME was purchased from RBI (Natick, MA). ODQ was obtained from Tocris Cookson (St. Louis, MO), and KT5823 and PD98059 were purchased from CalBiochem (La Jolla, CA). PGE2 and db-cAMP were purchased from Sigma, and GnRH was purchased from Peninsula Laboratories (Belmont, CA).

2.4. Experiment 1. Effect of icv infusion of GnRH, PGE2 and db-cAMP on estrous behavior in E2B-primed-female rats

E2B-primed animals were randomly assigned to receive an infusion of 50 ng of GnRH, 1 μg of PGE2 or 1 μg of db-cAMP. These doses were selected from dose response curves previously established by our laboratory [38]. Because different inhibitors were dissolved in different vehicles, separate control animals were primed with E2B and infused icv with one of these vehicles alone or vehicle followed 15 min later by drug. The numbers of animals in each of these groups were: saline (n= 8); 10% DMSO (n= 8); saline+GnRH (n= 9); 10% DMSO+GnRH (n= 9); saline+PGE2 (n= 9); 10% DMSO+PGE2 (n= 9); saline+db-cAMP (n= 8); 10% DMSO+db-cAMP (n= 9).

2.5. Experiment 2. Effect of NO pathway inhibitors on estrous behavior induced by GnRH, PGE2 or db-cAMP in E2B primed-female rats

E2B-primed female rats were infused icv with 500 μg of L-NAME or 22 μg of ODQ 15 min before infusion of GnRH, PGE2 or db-cAMP. The doses of these two inhibitors were selected on the basis of our previous work [13, 15, 17]. The numbers of animals in these groups were: L-NAME+GnRH (n= 8); L-NAME+PGE2 (n= 9); L-NAME+db-cAMP (n= 9); ODQ+GnRH (n= 9); ODQ+PGE2 (n= 8); ODQ+db-cAMP (n= 9). The vehicles that were tested in Experiment 1 are the vehicles used to dissolve the inhibitors in this experiment; thus, the controls included 9 females infused with 1 μl of 10% DMSO (the solvent used with ODQ) and 9 females infused with 1 μl saline (the solvent used with L-NAME). These two control treatments were combined for statistical analysis, because they did not differ significantly from each other with respect to either lordosis or proceptivity scores.

2.6. Experiment 3. Effect of PKG and ERK1/2 inhibitors on estrous behavior induced by GnRH, PGE2 or db-cAMP in E2-B-primed female rats

E2B-primed female rats were infused icv with 0.12 μg of KT5823 or 3.3 μg of PD98059 15 min before infusion of GnRH, PGE2 or db-cAMP. The doses of these inhibitors were selected on the basis of our previous work [40–42]. The numbers of animals in these groups were: KT5823+GnRH (n= 8); KT5823+PGE2 (n= 8); KT5823+db-cAMP (n= 8); PD98059+GnRH (n= 9); PD98059+PGE2 (n= 8); PD98059+db-cAMP (n= 9). The control group comprised 8 females (different from those used in Expt. 2) infused with 1 μl of 10% DMSO.

2.7. Behavioral testing

Behavioral testing was initiated 1 hr after icv infusion of GnRH, PGE2 or db-cAMP. Females were placed in a circular plexiglas arena (53 cm in diameter) with a vigorous male. Receptivity for each female was determined as a lordosis quotient [LQ=(number of lordosis/10 mounts)×100]. The intensity of lordosis was quantified according to the lordosis score (LS) proposed by Hardy and De Bold [32]. This scale ranged from 0 to 3 (0= no lordosis; 3= maximal lordosis posture) for each individual response and, consequently, from 0 to 30 for each female that received ten mounts from the male [43].

Proceptivity was evaluated by determining the incidence of hopping, darting, and ear-wiggling across the whole receptivity test [57]. We considered an animal proceptive when showing two of these behaviors during the testing period. This criterion was used because in our Sprague–Dawley rats, only a small proportion of animals will display all three proceptive behaviors together. This may be due to the fact that our Sprague–Dawley rats rarely (<10%) show darting in our testing conditions. Females were tested at 1, 2 and 4 hr after GnRH, PGE2 and db-cAMP infusions.

2.8. Histology

After the last behavioral test, the animals were anesthetized with halothane, and 1% methylene blue was administered through the cannula. The brain was removed and sectioned in the transverse plane to check the cannula position in the right lateral ventricle. Seven animals whose cannula was not in the ventricle were not included in the data analysis.

2.9. Data analysis

Individual rats were administered only one experimental drug, although they were tested repeatedly after icv infusions. Because our major interest was in the duration of behavioral inhibition in drug-treated compared to vehicle-treated animals at each time point rather than in the change over time, separate statistical comparisons were performed at each time point across groups. For example, comparisons in Experiment 1 were carried out separately at each post-infusion time between animals receiving drug and animals receiving the appropriate vehicle in the absence of the drug [e.g., DMSO+GnRH was compared to DMSO alone]. Animals infused only with different vehicles (saline and 10% DMSO) were also compared at each time, and no significant differences were found (see Table 1). Therefore, in later experiments, animals treated with the two vehicles were combined for statistical purposes. Because the distribution of LQ values in some groups was not normally distributed, a Wilcoxon-Mann Whitney U test rather than ANOVA was used to compare the control versus the different experimental groups at each time point. Fisher’s exact probability test was used to compare the proportion of proceptive females at each time interval [58, 59]. Differences were considered statistically significant if P < 0.05.

Table 1.

Effects of icv infusion of different vehicles alone and vehicles with GnRH, PGE2 and db-cAMP on sexual behavior (lordosis and proceptivity) in OVX rats primed with 5 μg of E2B.

| Test time | 1 hr | 2 hr | 4 hr | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | LQ Mean ± SE | % Proceptive Females | LQ Mean ± SE | % Proceptive Females | LQ Mean ± SE | % Proceptive Females | |

| Saline | 8 | 5 ± 2 | 0 | 4 ± 2 | 0 | 2 ± 1 | 0 |

| DMSO | 8 | 7 ± 5 | 0 | 7± 6 | 0 | 14 ± 6 | 0 |

| Saline+GnRH | 9 | 59 ± 8* | 33 | 82 ± 5** | 55+ | 92 ± 3** | 77* |

| DMSO + GnRH | 9 | 62 ± 6* | 22 | 71 ± 7** | 44 | 56 ± 11* | 11 |

| Saline+PGE2 | 9 | 58 ± 6* | 22 | 81 ± 8** | 55+ | 73 ± 6** | 22 |

| DMSO+PGE2 | 9 | 61 ± 12* | 44 | 73 ± 7* | 66* | 42 ± 12 | 11 |

| Saline+Db-cAMP | 8 | 61 ± 11** | 37 | 82 ± 4** | 50+ | 63 ± 9** | 37 |

| DMSO+Db-cAMP | 9 | 42 ± 12 | 22 | 68 ± 9* | 44 | 50 ± 10* | 33 |

P< 0.05;

P< 0.01;

P<0.001 vs animals receiving only saline or DMSO.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Experiment 1. Effects of LHRH, PGE2 and db-cAMP on estrous behavior of E2B-primed rats

Table 1 shows the LQ values and percentage of proceptive rats in OVX, E2B-primed females observed at 1, 2 and 4 hr following the infusion of vehicles alone or of vehicles plus GnRH, PGE2 or db cAMP. Neither saline nor DMSO alone induced any reproductive behaviors. All three test agents induced a significant facilitation of lordosis, which in nearly all cases was already present at the 1 hr test and reached its maximal value at 2 hr. Proceptive behavior was also displayed at the 1 hr test by same animals (none in vehicle groups) and was maximal at 2 hr.

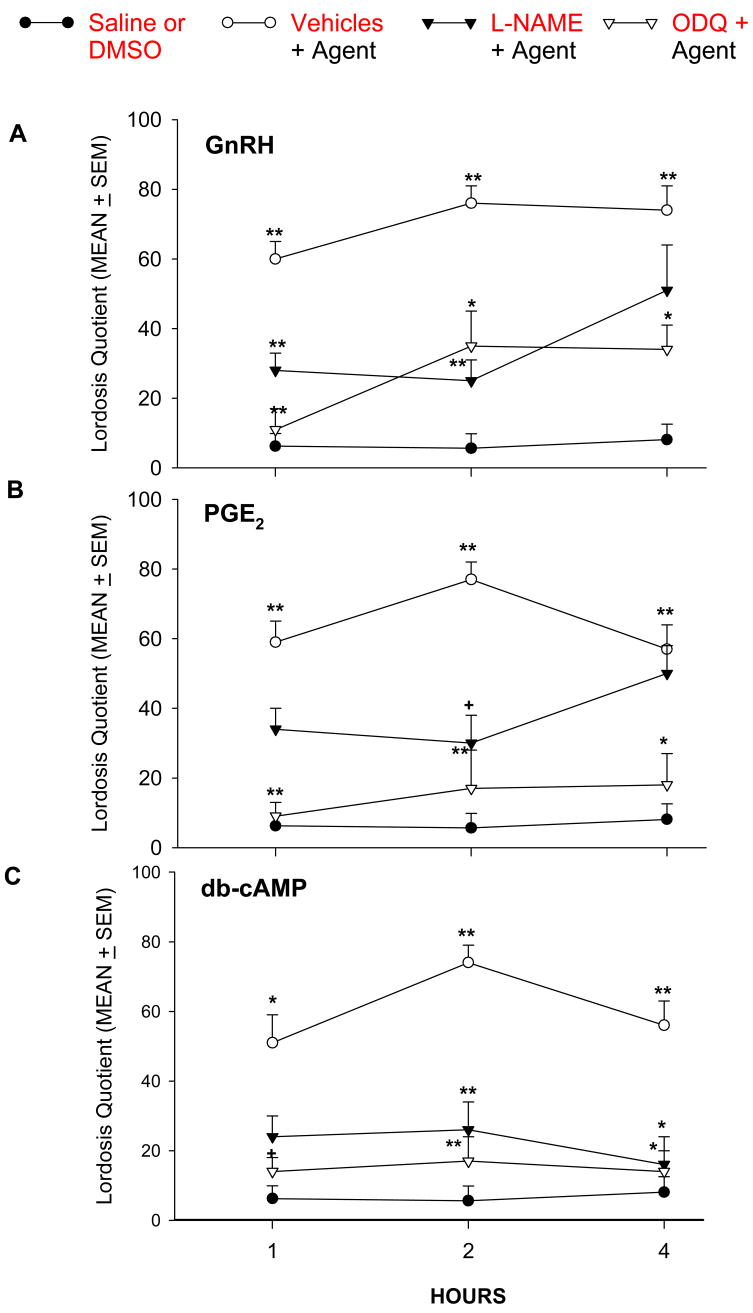

3.2. Experiment 2. Inhibitors of NOS and soluble guanylyl cyclase reduce sexual behavior induced by GnRH, PGE2, and dbcAMP in E2B-treated rats

Because the effect of the agents employed did not differ between the vehicles employed (saline or 10% DMSO), control data obtained with the two solvents was combined and compared with the estrous behavior observed in separate rats receiving GnRH, PGE2 or db-cAMP. As shown in Fig. 1, administration of the NOS inhibitor, L-NAME, and the specific inhibitor of soluble guanylyl cyclase, ODQ significantly attenuated GnRH-dependent increases in LQ at 1 and 2 hr; ODQ continued to inhibit GnRH-induced lordosis at 4 hr (Fig. 1A). LQ induced by PGE2 was inhibited significantly by L-NAME only at 2 hr (Fig. 1B). On the other hand, ODQ clearly reduced the LQ induced by PGE2 at all three times tested. The lordosis behavior induced by db-cAMP was blocked by L-NAME at 2 and 4 hr (Fig. 1C). As was the case for GnRH and PGE2, ODQ inhibited lordosis induced by db-cAMP at all three times tested.

Figure 1.

The facilitation of lordosis behavior in E2B-primed rats produced by (A) GnRH (50 ng); (B) PGE2 (1 μg); and (C) db-cAMP (1 μg) is antagonized by icv infusion of L-NAME (500 μg) and ODQ (22 μg). Drugs and vehicles were infused into the right lateral ventricle 15 min before application of GnRH, PGE2 or db-cAMP. Vehicle data from rats receiving saline or 10% DMSO were combined, because no significant differences were obtained with the two solvents (see Table 1). **P < 0.001; *P < 0.01; +P < 0.05 vs. corresponding group receiving vehicles alone (closed circle).

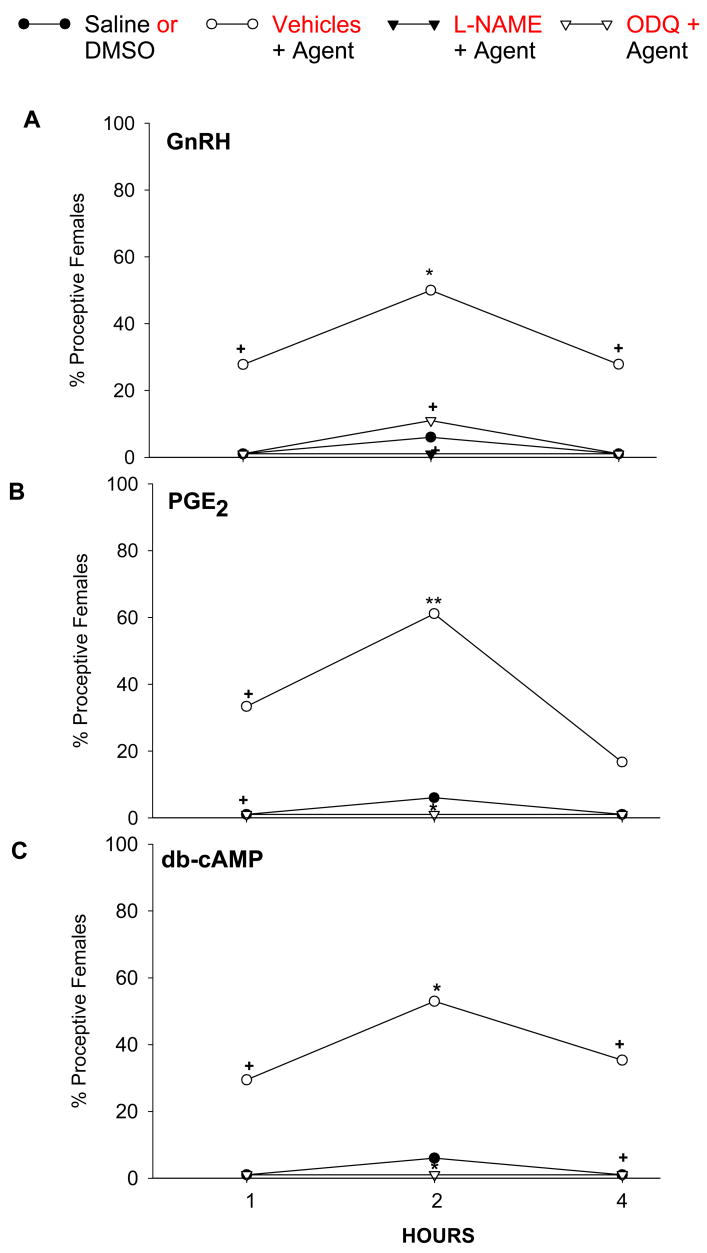

In addition, proceptive behavior induced by GnRH, PGE2, and db-cAMP was significantly suppressed by both inhibitors at 2 hr post-administration (Fig. 2). Both inhibitors continued blocking the proceptivity induced by GnRH and db-cAMP at 4 hr. We did not include control groups treated with L-NAME or ODQ alone, because previous studies showed that these compounds did not increase lordosis and proceptive behaviors [17].

Figure 2.

The facilitation of proceptive behaviors in E2B-primed rats produced by (A) GnRH (50 ng); (B) PGE2 (1 μg); and (C) db-cAMP (1 μg) is antagonized by icv infusion of L-NAME (500 μg) and ODQ (22 μg). Drugs and vehicles were infused into the right lateral ventricle 15 min before application of GnRH, PGE2 or db-cAMP. Vehicle data were combined (saline, 10% DMSO). *P < 0.01; +P < 0.05 vs. corresponding group receiving vehicles alone (closed circle).

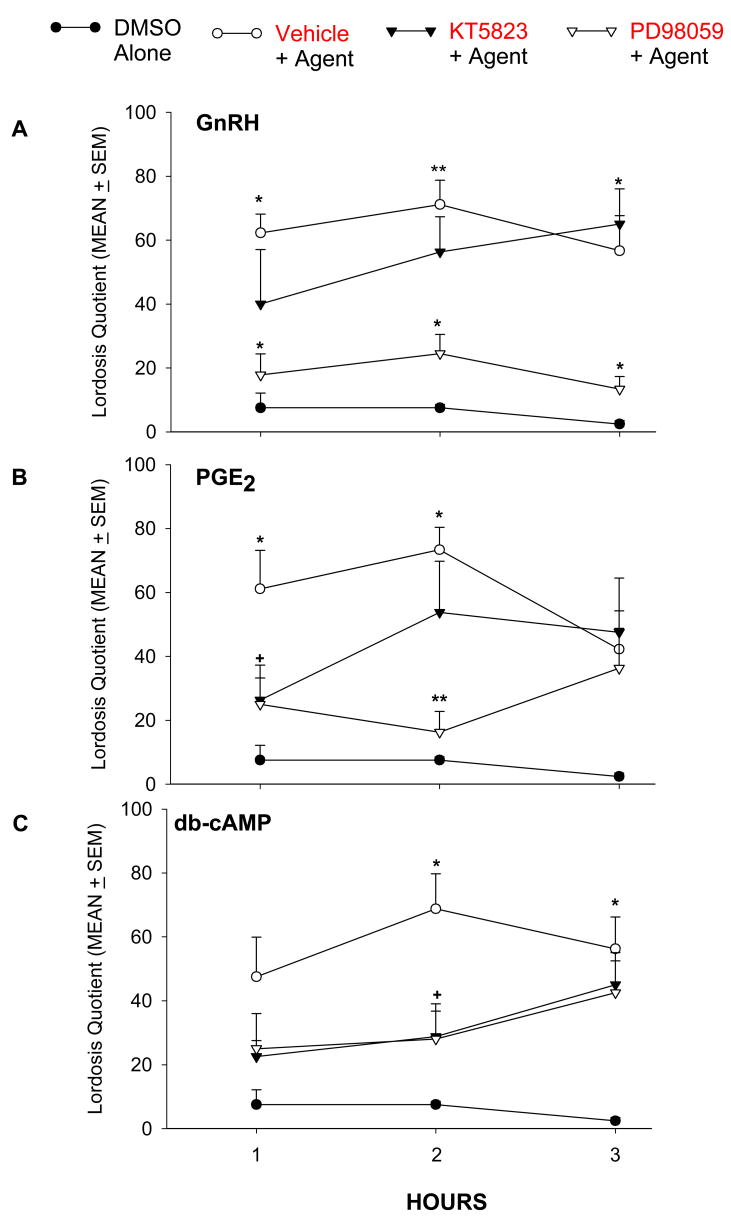

3.3. Experiment 3. Effects of KT5823 and PD98059 on estrous behavior induced by LHRH, PGE2, and dbcAMP in E2B-treated rats

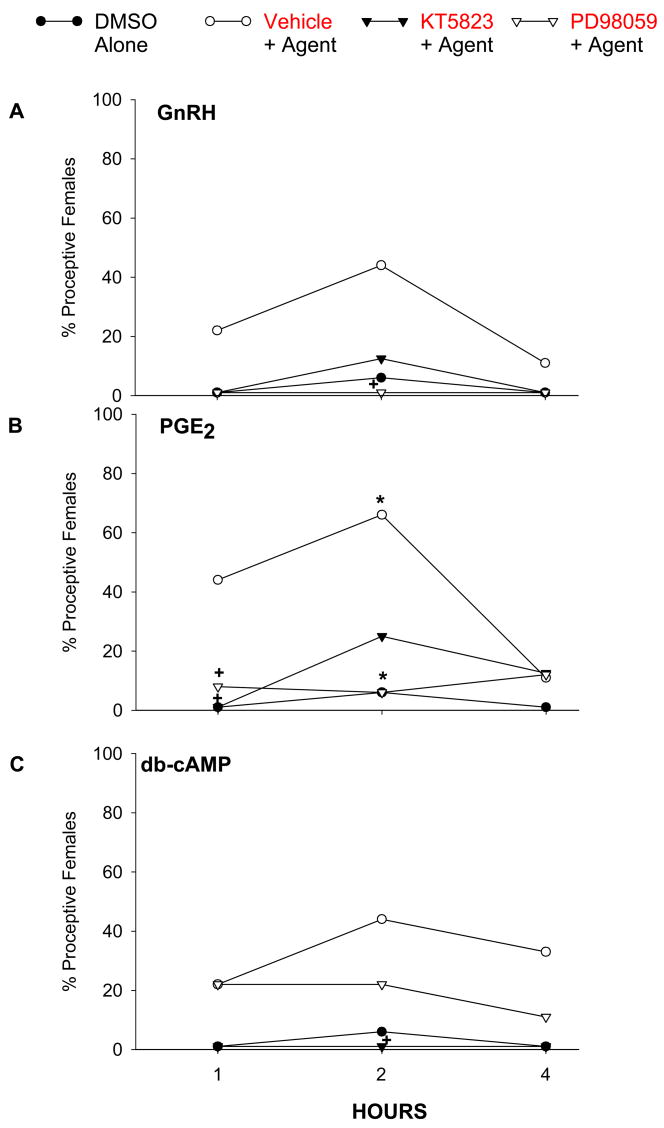

The PKG inhibitor KT5823 did not interfere with the stimulatory effect of GnRH on lordosis behavior at any time point, but it blocked the stimulatory effect of PGE2 at 1 hr and of db-cAMP at 2 hr (see Fig. 3). Similarly, KT5823 reduced the proceptivity induced by PGE2 at 1 hr and by db-cAMP at 2 hr.

Figure 3.

The facilitation of lordosis behavior in E2B-primed rats produced by (A) GnRH (50 ng); (B) PGE2 (1 μg); and (C) db-cAMP (1 μg) is antagonized by icv infusion of the PKG inhibitor KT5823 (0.12 μg) or the MAPK inhibitor PD98059 (3.3 μg). Drugs and 10% DMSO were infused into the right lateral ventricle 15 min before application of GnRH, PGE2 or db-cAMP. **P < 0.001; *P < 0.01; +P < 0.05 vs. 10% DMSO alone.

Administration of the ERK1/2 inhibitor PD98059 (Fig. 3) significantly decreased lordosis induced by GnRH and PGE2 at both 1 and 2 hr post injection, and this inhibition was still significant at 4 hr for GnRH-facilitated lordosis. PD98059 blocked db-cAMP-induced lordosis only at 2 hr. The time course of the inhibitory effect of PD98059 on proceptivity also varied with the chemical tested. PD98059 significantly suppressed proceptive behaviors induced by GnRH and PGE2 at 2 hr and by PGE2 at 1 hr. A decrease in the proportion of proceptive animals was also observed in females treated with db-cAMP, but this decrease did not reach statistical significance.

4. DISCUSSION

The present study shows that icv infusion of GnRH or PGE2 elicits lordosis and proceptive behaviors in E2B-primed rats with temporal characteristics similar to those obtained with icv infusion of db-cAMP. These results agree with previous experiments administering these chemicals both through intracerebral and sc routes [4, 7–9, 11, 33, 38, 60–64]. The data also show that the icv infusion of a NOS inhibitor, L-NAME, and an inhibitor of NO-stimulated guanylyl cyclase, ODQ, significantly attenuates the lordosis behavior induced by GnRH, PGE2 and db-cAMP, especially at the 1 and 2 hr tests. These findings support the hypothesis that the NO pathway is involved in the lordosis induced by these agents. Previous studies have shown that the NO system is important, if not essential, for the enhancement of estrous behavior in E2B-primed rats by progestins, adrenergic agonists and vaginocervical stimulation [13–17, 40, 65]. The NO pathway also modulates male sexual behavior [66] as well as the secretion of various hormones such as GnRH [25, 27, 67], corticotropin-releasing hormone [68], luteinizing hormone [24], and prolactin [69]. Brain NOergic activity, in turn, is regulated by a variety of stimuli affecting hormone secretion including gonadectomy [70], lactation [71], and stress [72]. These observations raise the possibility that NO-producing neurons are activated in female rats during mating and may help integrate the genitosensory stimulation that leads to neuroendocrine responses [65].

Our laboratories and others have shown that downstream kinases such as MAPK (specifically ERK) and PKG participate in the facilitation of estrous behavior in E2-primed rats by progestins, including 5α-reduced metabolites of P, and by vaginocervical stimulation [40–42, 73]. The present results strongly suggest that activation of the ERK family of MAPKs is involved in GnRH, PGE2 and db-cAMP-induced estrous behavior in E2-primed rats, because PD98059 interfered with the behavioral actions of all three agents. Both GnRH and PGE2 have been reported to activate the ERK/MAPK cascade in several tissues [55, 74–76]. For example, activation of distinct PGE2 receptor subtypes (EP1–EP4) can stimulate the MAPK pathway via Gαq or Gαi, or elevate cAMP via Gαs, leading to activation of PKA [55]. There is evidence that cAMP can stimulate MAPK signaling through mechanisms involving src, B-Raf, Rap1, Ras and various phosphatases (for review see [77, 78]). Finally, cAMP might also activate Ras and Rap1 through PKA-independent pathways involving guanine nucleotide exchange factors for Rap1 and Ras [77, 79].

It is interesting that administration of KT5823, a PKG inhibitor, failed to inhibit the effect of GnRH on lordosis behavior despite the fact that two NO pathway inhibitors, L-NAME and ODQ, significantly reduced GnRH-stimulated lordosis. This is unlikely to be a problem with the dose of KT5823 as this drug did inhibit lordosis induced by PGE2 and db-cAMP. Thus, the cGMP produced by GnRH may be acting independently of PKG, perhaps by cross-activating PKA or regulating phosphodiesterase (PDE) activity [80]. PDEs are the enzymes responsible for hydrolysis of cAMP and cGMP. Both a cGMP-activated PDE (type III) and cGMP-inhibited PDE (type II) are present in various cells, where they can decrease or increase cAMP levels, respectively, in response to cGMP [27, 33]. This mechanism is consistent with observations that administration of theophylline, a PDE inhibitor, enhances the behavioral effects of GnRH in E2-primed, OVX rats [33, 81, 82]. Icv injection of Antide, a GnRH-1 receptor antagonist, inhibits lordosis behavior in E2-primed rats infused with icv GnRH [9, 83]. The GnRH-1 receptor can be linked to Gαs, which activates the adenylyl cyclase-cAMP-PKA cascade [30, 31]. Indeed, we recently found that Rp-cAMPS, a potent inhibitor of PKA, blocked estrous behavior induced by GnRH, PGE2 and db-cAMP in E2-primed female rats [38]. Finally, cGMP can regulate cell function by interacting with cGMP receptor proteins other than PKG, such as cyclic nucleotide gated channels.

It is important to acknowledge that icv administration of drugs can influence both circumventricular organs and more distant regions throughout the brain. Therefore, each agent that we injected could be acting at different brains areas to elicit their effects. Similarly, NO is a highly diffusible signaling agent that can act not only in the cells in which it is generated but on neighboring cells as well (see [22]). Although the three agents used to induce lordosis (GnRH, PGE2 and dbcAMP) have been reported to act in or around the ventromedial hypothalamus [2, 7, 10], this fact does not rule out the possibility that the inhibitors used in this study acted on other brain structures that make up the efferent pathways mediating these behavioral responses or in brain regions modulating these responses. Infusion studies directed to specific brain areas are needed to identify their specific sites of action. It is possible that hypothalamic NO neurons implicated in lordosis could be a target for glutamate action in the hypothalamus [84–87]. Glutamate-induced GnRH release from hypothalamic fragments in vitro is blocked by a competitive inhibitor of NOS as well as by the NO scavenger hemoglobin [86]. Similar results were found in immortalized GnRH neurons [see 87]. However, infusion of glutamate and certain glutamate receptor agonists into the ventromedial hypothalamus inhibits lordosis [84], suggesting that the predominant site of NO action may be outside of this hypothalamic nucleus.

It is tempting to speculate that the PR is one of the molecules phosphorylated and activated by PKG and MAPK that leads to enhancement of estrous behavior, because the antiprogestin RU486 interferes with the facilitatory effect of GnRH and PGE2 on lordosis behavior [11]. However, the phosphorylation sites so far reported in PRs are exclusive targets of MAPK and not of PKG [83, 88]. However, PKG can activate MAPK [89–91], and we have shown that cGMP facilitation of lordosis is blocked by both RU486 and ERK/MAPK inhibitor PD98059 [13, 39]. Nonetheless, the participation of PKG and MAPK in the facilitation of estrous behavior likely involves molecules in addition to PRs.

In summary, the NO-cGMP pathway, via PKG-dependent and independent mechanisms, as well as the ERK/MAPK pathway, represent important mechanisms by which progestins and several neurotransmitters/neuromodulators, including GnRH and PGE2, can facilitate estrous behavior in estrogen-primed rodents. It is likely that the enhancement of female sexual behavior by different agents depends on the coordinate action of several signals acting at different brain sites and different cellular levels, for example, membrane receptors, generation of second messengers and activation of protein kinases. These multiple signals may in turn operate through a variety of molecules, including but not limited to PRs.

Figure 4.

The facilitation of proceptive behaviors in E2B-primed rats produced by (A) GnRH (50 ng); (B) PGE2 (1 μg); and (C) db-cAMP (1 μg) is antagonized by icv infusion of the PKG inhibitor KT5823 (0.12 μg) or the ERK1/2 inhibitor PD98059 (3.3 μg). Drugs and 10% DMSO were infused into the right lateral ventricle 15 min before application of GnRH, PGE2 or db-cAMP. *P < 0.01; +P < 0.05 vs. 10% DMSO alone.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the technical assistance of Guadalupe Domínguez López. This work was supported by PROMEP/103.5/04/1409 and CONACYT/61711 and R37 MH41414.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dudley CA, Moss RL. Facilitation of lordosis in the ray by prostaglandin E2. J Endocrinol. 1976;71:457–458. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0710457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foreman MM, Moss RL. Effects of subcutaneous injection and intrahypothalamic infusion of releasing hormones upon lordotic response to repetitive coital stimulation. Horm Behav. 1977;8:219–234. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(77)90039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gonzalez-Mariscal G, Beyer C. Blockade of LHRH-induced lordosis by alpha-and beta-adrenergic antagonists in ovariectomized, estrogen primed rats. Pharmacol. 1988;31:573–577. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(88)90232-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moss RL, McCann SM. Action of luteinizing hormone-releasing factor (lrf) in the initiation of lordosis behavior in the estrone-primed ovariectomized female rat. Neuroendocrinology. 1975;17:309–318. doi: 10.1159/000122369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riskind P, Moss RL. Effects of lesions of putative LHRH-containing pathways and midbrain nuclei on lordotic behavior and luteinizing hormone release in ovariectomized rats. Brain Res Bull. 1983;11:493–500. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(83)90120-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodriguez-Sierra JF, Komisaruk BR. Effects of prostaglandin E2 and indomethacin on sexual behavior in the female rat. Horm Behav. 1977;9:281–289. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(77)90063-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodríguez-Sierra JF, Komisaruk BR. Common hyphothalamic sites for activation of sexual receptivity in female rats by LHRH, PGE2 and progesterone. Neuroendocrinology. 1982;35:363–369. doi: 10.1159/000123408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakuma Y, Pfaff DW. LH-RH in the mesencephalic central grey can potentiate lordosis reflex of female rats. Nature. 1980;283:566–567. doi: 10.1038/283566a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu TJ, Glucksman MJ, Roberts JL, Mani SK. Facilitation of lordosis in rats by a metabolite of luteinizing hormone releasing hormone. Endocrinology. 2006;147:2544–2549. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beyer C, González-Mariscal G. Elevation in hypothalamic cyclic AMP as a common factor in the facilitation of lordosis in rodents: a working hypothesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1986;474:270–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1986.tb28018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beyer C, González-Flores O, González-Mariscal G. Progesterone receptor participates in the stimulatory effect of LHRH, prostaglandin E2 and cyclic AMP on lordosis and proceptive behavior in rats. J Neuroendocrinol. 1997;9:609–614. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1997.00617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beyer C, González-Flores O, García-Juárez M, González-Mariscal G. Non-ligand activation of estrous behavior in rodents: cross-talk at the progesterone receptor. Scand J Psychol. 2003 Jul;44(3):221–9. doi: 10.1111/1467-9450.00339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chu HP, Etgen AM. A potential role of cyclic GMP in the regulation of lordosis behavior of female rats. Horm Behav. 1997;32:125–132. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1997.1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chu HP, Morales JC, Etgen AM. Cyclic GMP may potentiate lordosis behaviour by progesterone receptor activation. J Neuroendocrinol. 1999;11:107–113. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1999.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chu HP, Etgen AM. Ovarian hormone dependence of alpha(1)-adrenoceptor activation of the nitric oxide-cGMP pathway: relevance for hormonal facilitation of lordosis behavior. J Neurosci. 1999;19:7191–7197. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-16-07191.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mani SK, Allen JM, Rettori V, McCann SM, O’Malley BW, Clark JH. Nitric oxide mediates sexual behavior in female rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:6468–6472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.González-Flores O, Etgen AM. The nitric oxide pathway participates in estrous behavior induced by progesterone and some of rig A-reduced metabolites. Horm Behav. 2004;45:50–57. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gonzalez-Flores O, Beyer C, Lima-Hernandez FJ, Gomora-Arrati P, Gomez-Camarillo MA, Hoffman K, Etgen AM. Facilitation of estrous behavior by vaginal cervical stimulation in female rats involves alpha1-adrenergic receptor activation of the nitric oxide pathway. Behav Brain Res. 2007;176:237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grossman AB, Rossmanith WG, Kabigting EB, Cadd G, Clifton D, Steiner RA. The distribution of hypothalamic nitric oxide synthase mRNA in relation to gonadotrophin-releasing hormone neurons. J Endocrinol. 1994;140:R5–8. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.140r005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodrigo J, Springall DR, Uttenthal O, Bentura ML, Abadia-Molina F, Riveros-Moreno V, Martinez-Murillo R, Polak JM, Moncada S. Localization of nitric oxide synthase in the adult rat brain. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1994;345:175–221. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1994.0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vernet D, Bonavera JJ, Swerdloff RS, Gonzalez-Cadavid NF, Wang C. Spontaneous expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase in the hypothalamus and other brain regions of aging rats. Endocrinology. 1998;139:3254–3261. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.7.6119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bredt DS, Hwang PM, Snyder SH. Localization of nitric oxide synthase indicating a neural role for nitric oxide. Nature. 1990;347:768–770. doi: 10.1038/347768a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prevot V, Bouret S, Stefano GB, Beauvillain J. Median eminence nitric oxide signaling. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2000;34:27–41. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(00)00035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ceccatelli S, Hulting AL, Zhang X, Gustafsson L, Villar M, Hokfelt T. Nitric oxide synthase in the rat anterior pituitary gland and the role of nitric oxide in regulation of luteinizing hormone secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:11292–11296. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rettori V, Canteros G, McCann SM. Interaction between NO and oxytocin: influence on LHRH release. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1997;30:453–457. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x1997000400004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vanhatalo S, Soinila S. Nitric oxide synthase in the hypothalamo-pituitary pathways. J Chem Neuroanat. 1995;8:165–173. doi: 10.1016/0891-0618(94)00043-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rettori V, Gimeno M, Lyson K, McCann SM. Nitric oxide mediates norepinephrine-induced prostaglandin E2 release from the hypothalamus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:11543–11546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.23.11543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Negro-Vilar A, Conte D, Valenca M. Transmembrane signals mediating neural peptide secretion: role of protein kinase C activators and arachidonic acid metabolites in luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone secretion. Endocrinology. 1986;119:2796–2802. doi: 10.1210/endo-119-6-2796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ojeda SR, Urbanski HF, Katz KH, Costa ME, Conn PM. Activation of two different but complementary biochemical pathways stimulates release of hypothalamic luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:4932–4936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.13.4932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arora KK, Krsmanovic LZ, Mores N, O’Farrell H, Catt KJ. Mediation of cyclic AMP signaling by the first intracellular loop of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:25581–25586. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.25581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ulloa-Aguirre A, Stanislaus D, Arora V, Vaananen J, Brothers S, Janovick JA, Conn PM. The third intracellular loop of the rat gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor couples the receptor to Gs- and G(q/11)-mediated signal transduction pathways: evidence from loop fragment transfection in GGH3 cells. Endocrinology. 1998;139:2472–2478. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.5.6022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jabbour HN, Sales KJ. Prostaglandin receptor signalling and function in human endometrial pathology. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2004;15:398–404. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beyer C, Canchola E, Larsson K. Facilitation of lordosis behavior in the ovariectomized estrogen primed rat by dibutyril cAMP. Physiol Behav. 1981;26:249–251. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(81)90019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beyer C, Fernández-Guasti A, Rodríguez-Manzo G. Induction of female sexual behavior by GTP in ovariectomized estrogen primed rats. Physiol Behav. 1982;28:1073–1076. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(82)90177-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.González-Flores O, Ramírez-Orduña JM, Lima-Hernandez FJ, Garcia-Juarez M, Beyer C. Differential effect of kinase A and C blockers on lordosis facilitation by progesterone and its metabolites in ovariectomized estrogen-primed rats. Horm Behav. 2006;49:398–404. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mani SK, Fienberg AA, O’Callaghan JP, Snyder GL, Allen PB, Dash P, Moore AN, Mitchell AJ, Bibb J, Greengard P, O’Malley BW. Requirement for DARPP-32 in progesterone -facilitated sexual receptivity in female rats and mice. Science. 2000;287:1053–1056. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5455.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petralia SM, Frye CA. In the ventral tegmental area, G-protein and cAMP mediate the neurosteroids 3α, 5α-THP’s actions at dopamine type I receptors for lordosis rats. Neuroendocrinology. 2004;80:233–243. doi: 10.1159/000082752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ramírez-Orduña JM, Lima-Hernandez FJ, Garcia-Juarez M, Gonzalez-Flores O, Beyer C. Lordosis facilitation by LHRH, PGE2 or db-cAMP requires activation of the kinase A pathway in estrogen primed rats. Pharmacol Bichem Behav. 2007;86:169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fernández-Guasti A, Rodríguez-Manzo G, Beyer C. Effect of guanine derivatives on lordosis behavior in estrogen primed rats. Physiol Behav. 1983;31:589–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.González-Flores O, Shu J, Camacho Arroyo I, Etgen AM. Regulation of lordosis by cyclic 3′, 5′-guanosina monophosphate, progesterone, and its 5α–reduced metabolites involves mitogen-activated protein kinase. Endocrinology. 2004;145:5560–5567. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Acosta-Martinez M, Gonzalez-Flores O, Etgen AM. The role of progestin receptors and the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in delta opioid receptor facilitation of female reproductive behaviors. Horm Behav. 2006;49:458–462. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Etgen AM, Acosta-Martínez M. Participation of growth factor signal transduction pathways in estradiol-facilitation of female reproductive behavior. Endocrinology. 2003;144:3828–3835. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frye CA, Walf AA. In the ventral tegmental area, the membrane-mediated actions of progestins for lordosis of hormone-primed hamsters involve phospholipase C and protein kinase C. J Neuroendocrinol. 2007;19:717–724. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2007.01580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kow L-M, Brown HE, Pfaff DW. Activation of protein kinase C in the hypothalamic ventromedial nucleus or the midbrain central gray facilitates lordosis. Brain Res. 1994;660:241–248. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91295-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mobbs CV, Rothfeld JM, Saluja R, Pfaff DW. Phorbol esters and forskolin infused into midbrain central gray facilitate lordosis. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1989;34:665–667. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(89)90572-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gonzalez-Flores O, Etgen AM, Komisaruk BK, Gómora-Arrati P, Macias-Jimenez A, Lima-Hernández FJ, Garcia-Juárez M, Beyer C. Antagonists of the protein kinase A and mitogen-activated protein kinase systems and of the progestin receptor block the ability of vaginocervical/flank-perineal stimulation to induce female rat sexual behaviour. J Neuroendocrinol. 2008;20:1361–1367. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Millar R, Lowe S, Conklin D, Pawson A, Maudsley S, Troskie B, Ott T, Millar M, Lincoln G, Sellar R, Faurholm B, Scobie G, Kuestner R, Terasawa E, Katz A. A novel mammalian receptor for the evolutionarily conserved type II GnRH. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:9636–9641. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141048498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Millar RP. GnRHs and GnRH receptors. Anim Reprod Sci. 2005;88:5–28. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2005.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Watanabe H, Tanaka S, Akino T, Hasegawa-Sasaki H. Evidence for coupling of different receptors for gonadotropin-releasing hormone to phospholipases C and A2 in cultured rat luteal cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;168:328–334. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)91712-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Poulin B, Rich N, Mitev Y, Gautron JP, Kordon C, Enjalbert A, Drouva SV. Differential involvement of calcium channels and protein kinase-C activity in GnRH-induced phospholipase-C, -A2 and -D activation in a gonadotrope cell line (alpha T3-1) Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1996;122:33–50. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(96)03868-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Naor Z, Fawcett CP, McCann SM. Involvement of cGMP in LHRH-stimulated gonadotropin release. Am J Physiol. 1978;235:E586–590. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1978.235.6.E586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Naor Z, Snyder G, Fawcett CP, McCann SM. Evidence for coupling of different receptors for gonadotropin-releasing hormone to phospholipases C and A2 in cultured rat luteal cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1978;4:475–486. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)91712-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mitchell R, McConnell SK, Sim P. Phospholipase C-dependent activation of tyrosine kinases by LHRH in alpha T3-1 cells, and its role in LHRH priming of inositol phosphate production. Biochem Soc Trans. 1995;23:143S. doi: 10.1042/bst023143s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sim PJ, Wolbers WB, Mitchell R. Activation of MAP kinase by the LHRH receptor through a dual mechanism involving protein kinase C and a pertussis toxin-sensitive G protein. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1995;112:257–263. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(95)03616-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bos CL, Richel DJ, Ritsema T, Peppelenbosch MP, Versteeg HH. Prostanoids and prostanoid receptors in signal transduction. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:1187–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Australia: Academic Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Madlafousek J, Hlinak K. Sexual behaviour of the female laboratory rat: inventory, pattering, and measurement. Behaviour. 1977;63:129–174. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bruning JL, Kintz BL. Computational handbook of statistics. Illinois, London: Scott, Foresman and Company, Glenview; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Siegel S, Castellan NJ. Estadística no paramétrica: aplicada a las ciencias de la conducta. México: Trillas; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 60.González-Mariscal G, Melo AI, Beyer C. Progesterone but not LHRH or prostaglandin E2, induces sequential inhibition of lordosis to various lordogenic agents. Neuroendocrinol. 1993;57:940–945. doi: 10.1159/000126457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hall NR, Luttge WG. Diencephalic sites responsive to prostaglandin E2 facilitation of sexual receptivity in estrogen-primed ovariectomized rats. Brain Res Bull. 1977;2:203–207. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(77)90039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hall NR, Luttge WG, Berry RB. Intracerebral prostaglandin E2: effects upon sexual behavior, open field activity and body temperature in ovariectomized female rats. Prostaglandins. 1975;10:877–888. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(75)90015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Moss RL, Foreman MM. Potentiation of lordosis behavior by intrahypothalamic infusion of synthetic luteinizing hormone releasing hormone. Neuroendocrinology. 1976;20:176–181. doi: 10.1159/000122481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rodríguez-Sierra JF, Komisaruk BR. Lordosis induction in the rat by prostaglandin E2 sistemically or intracranially in the absense of ovarian hormones. Prostaglandins. 1978;15:513–524. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(78)90135-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gonzalez-Flores O, Beyer C, Lima-Hernandez FJ, Gomora-Arrati P, Gomez-Camarillo MA, Hoffman K, Etgen AM. Facilitation of estrous behavior by vaginal cervical stimulation in female rats involves alpha1-adrenergic receptor activation of the nitric oxide pathway. Behav Brain Res. 2007;176:237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hull EM, Lumley LA, Matuszewich L, Dominguez J, Moses J, Lorrain DS. The roles of nitric oxide in sexual function of male rats. Neuropharmacology. 1994;33:1499–1504. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)90054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Moretto M, Lopez FJ, Negro-Vilar A. Nitric oxide regulates luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone secretion. Endocrinology. 1993;133:2399–2402. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.5.8104781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Costa A, Trainer P, Besser M, Grossman A. Nitric oxide modulates the release of corticotropin-releasing hormone from the rat hypothalamus in vitro. Brain Res. 1993;605:187–192. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91739-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Duvilanski BH, Zambruno C, Seilicovich A, Pisera D, Lasaga M, Diaz MC, Belova N, Rettori V, McCann SM. Role of nitric oxide in control of prolactin release by the adenohypophysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:170–174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.1.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Okamura H, Yokosuka M, Hayashi S. Estrogenic induction of NADPH-diaphorase activity in the preoptic neurons containing estrogen receptor immunoreactivity in the female rat. J Neuroendocrinol. 1994;6:597–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1994.tb00624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ceccatelli S, Eriksson M. The effect of lactation on nitric oxide synthase gene expression. Brain Res. 1993;625:177–179. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90153-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hatakeyama S, Kawai Y, Ueyama T, Senba E. Nitric oxide synthase-containing magnocellular neurons of the rat hypothalamus synthesize oxytocin and vasopressin and express Fos following stress stimuli. J Chem Neuroanat. 1996;11:243–256. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(96)00166-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mani SK, Allen JM, Clark JH, Blaustein JD, O’Malley BW. Convergent pathways for steroid hormone- and neurotransmitter-induced rat sexual behavior. Science. 1994;265:1246–1249. doi: 10.1126/science.7915049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ghayor C, Rey A, Caverzasio J. Prostaglandin-dependent activation of ERK mediates cell proliferation induced by transforming growth factor beta in mouse osteoblastic cells. Bone. 2005;36:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kang SK, Tai CJ, Cheng KW, Leung PC. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone activates mitogen-activated protein kinase in human ovarian and placental cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2000;170:143–151. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(00)00320-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Naor Z, Benard O, Seger R. Activation of MAPK cascades by G-protein-coupled receptors: the case of gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2000;11:91–99. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(99)00232-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dumaz N, Marais R. Integrating signals between cAMP and the RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK signalling pathways. Based on the anniversary prize of the Gesellschaft fur Biochemie und Molekularbiologie Lecture delivered on 5 July 2003 at the Special FEBS Meeting in Brussels. Febs J. 2005;272:3491–3504. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stork PJ, Schmitt JM. Crosstalk between cAMP and MAP kinase signaling in the regulation of cell proliferation. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:258–266. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)02294-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ciullo I, Diez-Roux G, Di Domenico M, Migliaccio A, Avvedimento EV. cAMP signaling selectively influences Ras effectors pathways. Oncogene. 2001;8(20):1186–1192. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vaandrager AB, de Jonge HR. Signalling by cGMP-dependent protein kinases. Mol Cell Biochem. 1996;157:23–30. doi: 10.1007/BF00227877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Beyer C, Canchola E. Facilitation of progesterone induced lordosis behavior by phosphodiesterase inhibitors in estrogen primed rats. Physiol Behav. 1981;27:731–733. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(81)90248-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Beyer C, Gomora P, Canchola E, Sandoval Y. Pharmacological evidence that LH-RH action on lordosis behavior is mediated throught a rise in cAMP. Horm Behav. 1982;16:107–112. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(82)90011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gomora-Arrati P, Beyer C, Lima-Hernandez FJ, Gracia ME, Etgen AM, Gonzalez-Flores O. GnRH mediates estrous behavior induced by ring A reduced progestins and vaginocervical stimulation. Behav Brain Res. 2008;187:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kow LM, Harlan RE, Shivers BD, Pfaff DW. Inhibition of the lordosis reflex in rats by intrahypothalamic infusion of neural excitatory agents: evidence that the hypothalamus contains separate inhibitory and facilitatory elements. Brain Res. 1985;19(341):26–34. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91468-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sandoval Y, Komisaruk B, Beyer C. Possible role of inhibitory glycinergic neurons in the regulation of lordosis behavior in the rat. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1988;29:303–307. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(88)90160-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bhat GK, Mahesh VB, Lamar CA, Ping L, Aguan K, Brann DW. Histochemical localization of nitric oxide neurons in the hypothalamus: association with gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons and co-localization with N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. Neuroendocrinology. 1995;62:187–197. doi: 10.1159/000127004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mahesh VB, Brann DW. Regulatory role of excitatory amino acids in reproduction. Endocrine. 2005;28:271–280. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:28:3:271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lange CA, Shen T, Horwitz KB. Phosphorylation of human progesterone receptors at serine-294 by mitogen-activated protein kinase signals their degradation by the 26s proteasome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:1032–1037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shen T, Horwitz KB, Lange CA. Transcriptional hyperactivity of human progesterone receptors is coupled to their ligand-dependent down-regulation by mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent phosphorylation of serine 294. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:6122–6131. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.18.6122-6131.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ho AK, Hashimoto K, Chik CL. 3′, 5′-cyclic guanosine monophosphate activates mitogen-activated protein kinase in rat pinealocytes. Neurochem. 1999;73:598–604. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0730598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Li Z, Zhang G, Feil R, Han J, Du X. Sequential activation of p38 and ERK pathways by cGMP-dependent protein kinase leading to activation of the platelet integrin alphaIIb beta3. Blood. 2006;107:965–972. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]