Abstract

Gamma-protocadherins (Pcdh-γs) are good candidates to mediate specificity in synaptogenesis but their role in cell-cell interactions is a matter of debate. We proposed that Pcdh-γs modify preformed synapses via trafficking of Pcdh-γs-containing organelles, insertion into synaptic membranes and homophilic transcellular interaction. Here we provide evidence in support of this model. We show for the first time that Pcdh-γs have homophilic properties and that they accumulate at dendrodendritic and axo-dendritic interfaces during neuronal development. Pcdh-γs are maintained in a substantial mobile intracellular pool in dendrites and cytoplasmic deletion shifts the molecule to the surface and reduces the number and velocity of the mobile packets. We monitored Pcdh-γ temporal and spatial dynamics in transport organelles. Pcdh-γ organelles bud and fuse with stationary clusters near synapses. These results suggest that Pcdh-γ-mediated cell-cell interactions in synapse development or maintenance are tightly regulated by control of intracellular trafficking via the cytoplasmic domain.

Keywords: Adhesion, synaptogenesis, cadherin, live-cell imaging, FRAP, trafficking

Introduction

The clustered protocadherins (Pcdhs) comprise three families of putative neural receptors, termed α/CNR, β, and γ (Kohmura et al., 1998; Wu and Maniatis, 1999), that have been proposed to mediate highly specific adhesion and recognition between neurons in synaptogenesis (Frank and Kemler, 2002; Kohmura et al., 1998; Shapiro and Colman, 1999; Wu and Maniatis, 1999). These proteins have been ideal candidates to mediate cell-specific synapse formation because of the large number of isoforms, their cell autonomous differential expression, their presence at some synapses, and their similarity to the classical cadherins (Esumi et al., 2005; Frank et al., 2005; Jontes and Phillips, 2006; Kohmura et al., 1998; Wang et al., 2002a; Wang et al., 2002b).

Initial studies suggested synaptic roles for both Pcdh-αs and Pcdh-γs: a synaptic distribution has been reported for Pcdh-αs (Kohmura et al., 1998) and gene disruption demonstrated Pcdh-γs to be essential for synaptic development as knockout or Pcdh-γ hypomorph animals exhibited reduced numbers of synapses that were smaller than those found in wild-type animals (Wang et al., 2002b; Weiner et al., 2005). Moreover, neurons cultured from these animals displayed reduced amplitude of induced and spontaneous postsynaptic responses (Weiner et al., 2005). Biochemically, Pcdh-γs are enriched in Triton X-100 insoluble synaptic material (Phillips et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2002b). However, light and electron microscopic localization has shown that Pcdh-γs are present at only a subset of synapses in cultured neurons (Phillips et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2002b). Furthermore, Pcdh-αs (Morishita et al., 2006) and Pcdh-γs (Obata et al., 1995) lack adhesive activity in conventional cell aggregation assays although more sensitive assays have detected adhesion for Pcdh-γs (Frank et al., 2005; Reiss et al., 2006). A variety of genetic manipulations involving conditional or complete Pcdh-γ disruption showed that the molecules participate in neuronal survival (Lefebvre et al., 2008; Prasad et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2002b; Weiner et al., 2005). Whether Pcdhs function as genuine adhesion proteins, synaptic or otherwise, that mediate homophilic recognition between neurons is therefore still a topic of debate (Jontes and Phillips, 2006; Morishita and Yagi, 2007; Wang et al., 2002b) and it is possible that some of the functions attributable to the Pcdhs may be mediated by a cytoplasmic cleavage product that has been found to travel to the nucleus (Bonn et al., 2007; Haas et al., 2005). Regardless, the potential extracellular recognition activity of the Pcdhs, suggested by their cadherin extracellular domains, has been unaddressed in neurons.

Here we find that Pcdh-γs accumulate at dendro-dendritic and axo-dendritic contacts in neurons from a substantial intracellular dendritic pool. Deletion of the cytoplasmic domain reduces the intracellular pool and enhances targeting to cell-cell interfaces. Pcdh-γ mediated cell-cell interactions were found to be homophilic. Finally, we find that overexpression of a single isoform of Pcdh-γ in adult cells has effects on synaptic development in cultured cells. Our results suggest that cell-cell interactions are a major biological activity of the Pcdh-γs in neurons. Modulation of Pcdh-γ surface localization by the cytoplasmic domain may be important for neuronal and synaptic development.

Results

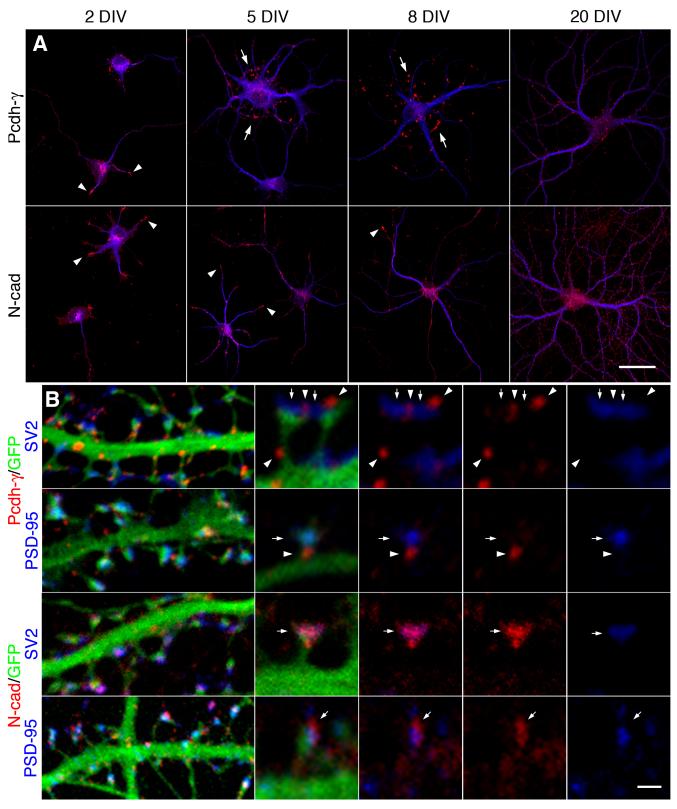

Pcdh-γs are retargeted during early differentiation in neurons

It had initially been hypothesized (Frank and Kemler, 2002; Kohmura et al., 1998; Shapiro and Colman, 1999) that Pcdhs operate in the same way as the classical cadherins, which adhere preand postsynaptic membranes together selectively through homophilic adhesion. However, Pcdh-γs lack adhesive activity in cells where classical cadherin adhesion is robust (Obata et al., 1995). Because of this, as well as the effect of Pcdh-γ deletion on neuronal survival, others have suggested the possibility of a non-adhesive role as the primary mode of action for the Pcdh-γs (Wang et al., 2002b). To determine if the distribution of Pcdh-γs is consistent with a role in adhesion or recognition in neurons, we compared the Pcdh-γs to N-cadherin (N-cad) by immunostaining in cultured hippocampal neurons during development in vitro. After 2 days in vitro (DIV), both Pcdh-γs and N-cad (red channel Fig. 1A) had essentially the same distribution along dendrites, identified by MAP2 immunostaining (Fig. 1A, blue channel), with a higher concentration in growth cones (arrowheads). However, by 5-8 DIV, Pcdh-γs acquired a dramatically different distribution than N-cad. Large Pcdh-γ puncta (arrows) accumulated at sites surrounding the soma that appeared to be associated with fine processes and was absent from growth cones. In contrast, by 5-8 DIV, finer N-cad puncta were distributed along the dendritic length with continued enrichment in growth cones (arrowheads). High power images of Pcdh-γ or N-cad and MAP2 double stained neurons are shown in Supplemental Fig. 1A. By 20 DIV, the Pcdh-γs were found along the dendritic length as puncta, which were larger and sparser than those of N-cad (right panel Fig. 1A). In mature neurons, Pcdh-γs and N-cad were differentially targeted in pre- and post-synaptic compartments (Fig. 1B). N-cad colocalized with both synaptic markers and its pattern was relatively diffuse in the membrane (Fig. 1B, lower two rows), while Pcdh-γ localized mostly adjacent to synaptic markers with a more tightly clustered distribution (Fig. 1B, upper two rows). These results suggest that Pcdh-γs and N-cad participate in distinct processes.

Figure 1. Pcdh-γs are retargeted to juxtasomatic regions during early neural differentiation.

(A) Neurons were immunostained for Pcdh-γs and N-cad (red channel) and MAP2 (blue channel) at the indicated developmental stages. Arrowheads show growth cones and arrows show Pcdh-γ juxtasomatic clusters. Bar = 25 μm. (B) High magnification images of EGFP-transfected dendrites immunolabeled at 20 DIV for Pcdh-γs or N-cad (red channel) together with synaptic markers PSD-95 (postsynaptic) or SV2 (presynaptic) (blue channels). Pcdh-γs (arrowheads, top two panels) were found to be adjacent to synaptic specializations (arrows) while N-cad localized precisely to synapses. Bar = 2 μm (left panels) or 0.75 μm.

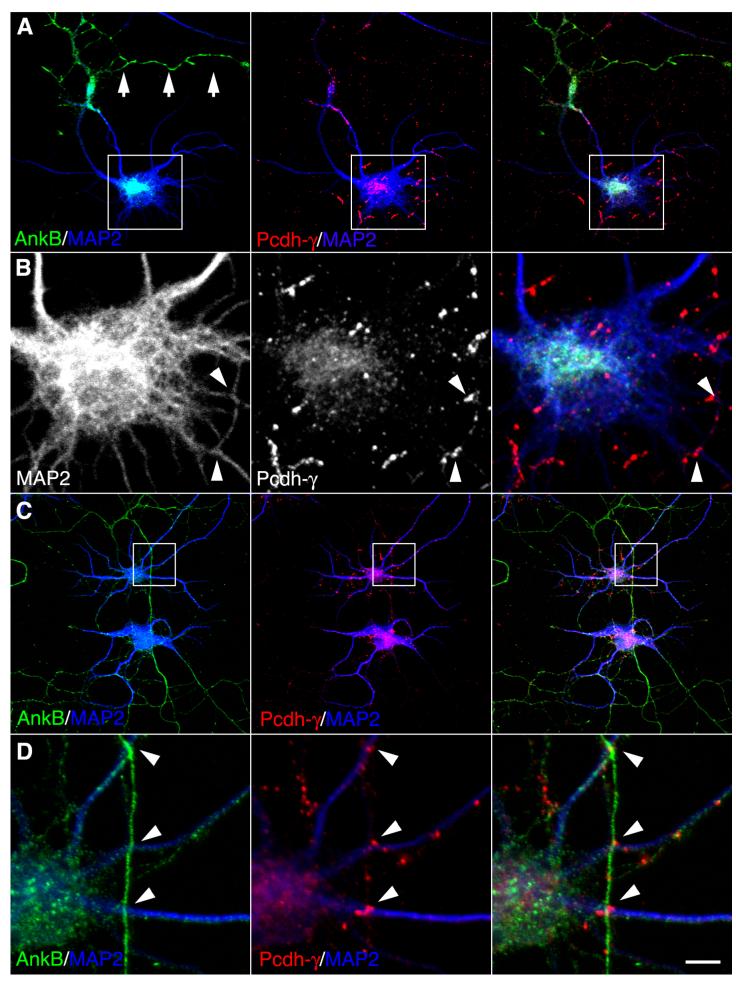

Pcdh-γs accumulate specifically at sites of dendro-dendritic and axo-dendritic interactions during development

In young cells, we observed that clustered Pcdh-γ accumulates at neurite contacts. Most of the Pcdh-γ positive processes appeared to emanate from dendrites in GFP filled neurons (Supplemental Fig. 1B) but it remained possible that they could be axons contacting dendrites and/or cell bodies. To examine this, neurons at 8 DIV were immunostained with MAP2 (blue channel, Fig. 2) and ankyrin B (green channel, Fig. 2) to identify dendrites and axons respectively along with anti-Pcdh-γ (red channel, Fig. 2). Pcdh-γ clusters were present on both axons and somatodendritic compartments. In some neurons, axons (arrows, Fig. 2A) completely avoided the cell body and in these cases Pcdh-γs accumulated at sites of MAP2 positive dendro-dendritic contacts (arrowheads, Fig. 2B). In other instances (Fig. 2C), axons did contact the cell body and Pcdh-γs accumulated at axon-dendritic contact points (Fig. 2D, arrowheads). Some clusters found on processes that were neither MAP2 nor ankryin B positive likely correspond to fine dendrites that bridge larger dendrites as seen in Pcdh-γ labeled GFP filled neurons (see Supplemental Fig. 1B).

Figure 2. Juxtasomatic Pcdh-γ puncta correspond to dendrodendritic and axodendritic contact points.

(A) Neurons at 8 DIV were immunolabeled with anti-ankyrin-B (green channel) anti-MAP2 (blue channel) and anti-Pcdh-γs (red channel). Axons (arrows in A) do not contact somatodendritic surfaces of the neuron. (B) High magnification of boxed region in A. Pcdh-γs accumulate at points of dendro-dendritic contact (arrowheads in B). (C) Same labeling as in A. Axons (green channel) make contact with somatodendritic surfaces. (D) High magnification of boxed region in C. Axo-dendritic contact points (arrowheads in D) show accumulation of Pcdh-γs. Bar = 20 μm in A, C and 5 μm in B, and 2.5 μm in D.

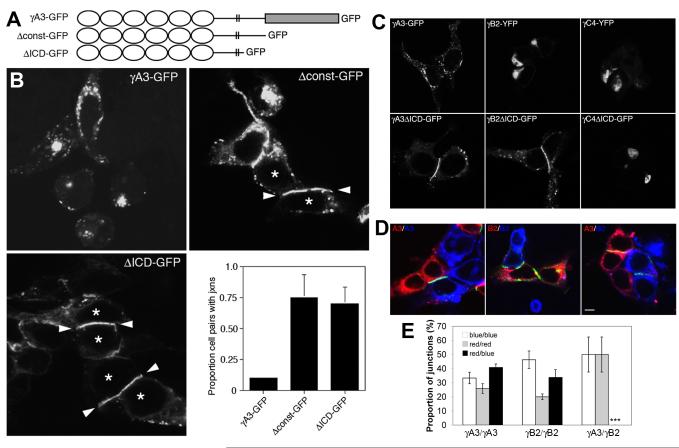

Pcdh-γ cytoplasmic domain affects accumulation at cell-cell interfaces in cell lines

Currently, the role of the Pcdh-γ intracellular domain in Pcdh-γ function is not understood. We deleted either the constant portion of the Pcdh-γ cytoplasmic domain from Pcdh-γA3-GFP or the constant and most of the variable cytoplasmic domain (Δconst-GFP and ΔICD-GFP, respectively; Fig. 3A) to determine the effect of these deletions on their distribution within the cells. Initially, these constructs were expressed in HEK293 cells. Wild type γA3-GFP exhibited a punctate distribution with little accumulation at cell-cell contacts consistent with their weak adhesive activity observed previously in non-neural cells (Frank et al., 2005; Obata et al., 1995) (Fig. 3B). However, when either the constant domain or the entire cytoplasmic domain was deleted, a dramatic accumulation was observed at the interface (arrowheads) between two transfected cells (asterisks). Quantification revealed that ∼70-75% of all cell pairs accumulated Δconst-GFP or ΔICD-GFP at their interfaces while only ∼10% of the cell pairs accumulated full-length γA3-GFP at cell-cell junctions (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3. Cytoplasmic deletion of Pcdh-γs promotes recruitment to cell junctions and unmasks the homophilic properties of Pcdh-γs.

(A) Constructs of Pcdh-γA3. Ovals are cadherin repeats, rectangle is the Pcdh-γ constant cytoplasmic domain and double lines are the plasma membrane. (B) HEK 293 cells transfected with Pcdh-γA3-GFP (left upper panel) show a punctate distribution of the protein with little accumulation at cell-cell contacts. Deletion of the constant domain (right upper panel) or the majority of the cytoplasmic domain (left lower panel) of Pcdh-γA3 enriched the protein at cell-cell junctions (arrowheads) between two transfected HEK293 cells (asterisks). Histogram shows quantification of the proportion of transfected cell pairs that displayed an observable cell-cell junction. Error bars denote S.E.M. (C) HEK 293 cells transfected with full-length Pcdh-γA3-GFP, -γB2-YFP and -γC4-YFP constructs (top panels). Intracellular domain deletions (ΔICD) of -γA3 and -γB2, but not -γC4 isoform accumulate at cell-cell contacts (bottom panels). (D) DiI (red channel) or DiD (blue channel) labeled cells were transfected with γA3ΔICDGFP or γB2ΔICD-GFP and then mixed. DiI labeled γA3ΔICD-GFP transfected cells never formed Pcdh-γ cell-cell junctions with DiD labeled γB2ΔICD-GFP (right panel). Bar = 10 μm. (E) Quantification of red-red, blue-blue and red-blue cell pairs exhibiting a GFP labeled cell junction for the three conditions. At least 20 junctions were counted in each of three independent experiments (***p<0.005). Error bars denote S.E.M.

Pcdh-γ interaction at cell contacts has homophilic properties

Pcdh-γA3, -γB2 and γC4, full length and cytoplasmic deletions fused to GFP or YFP, were compared for their ability to accumulate at cell-cell interfaces in HEK293 cells. γB2-YFP was also found in intracellular accumulations (Fig. 3C, top). When the cytoplasmic domain of γB2-YFP was deleted (γB2ΔICD-GFP) the construct targeted precisely to cell-cell interfaces (Fig. 3C, bottom) similar to γA3ΔICD-GFP. In contrast, γC4-YFP, full length or intracellular domain deleted (Fig. 3C, top and bottom, respectively), was never efficiently transported to cell-cell junctions.

We took advantage of the ability of Pcdh-γA3 and -γB2 cytoplasmic deletions to accumulate at cell-cell interfaces to evaluate whether these two Pcdh-γs exhibit homophilic or heterophilic cell-cell interactions. To establish the assay, HEK293 cells were labeled with lipophilic dyes DiI or DiD (Fig. 3D, red or blue channel, respectively) and transfected with γA3ΔICD-GFP or γB2ΔICD-GFP. The separately transfected DiI and DiD labeled cells were then mixed and cultured overnight. Both γA3ΔICD-GFP and γB2ΔICD-GFP accumulated at interfaces between red (DiI labeled) and blue (DiD labeled) cells (Fig. 3D, left and middle panels). This demonstrates that cells transfected separately with either γA3ΔICD-GFP or γB2ΔICD-GFP can effectively associate and accumulate these constructs at the interface de novo via cell-cell interaction. In contrast, when DiI labeled γA3ΔICD-GFP transfected cells were mixed and cultured with DiD labeled γB2ΔICD-GFP transfected cells (Fig. 3D, right), GFP accumulations were never observed between red and blue cells. The proportion of junctions between red-red, blue-blue and red-blue cell pairs was quantified as shown in Fig. 3E. These results demonstrate that the extracellular domains of Pcdh-γAs and -γBs mediate cell-cell interaction with homophilic properties.

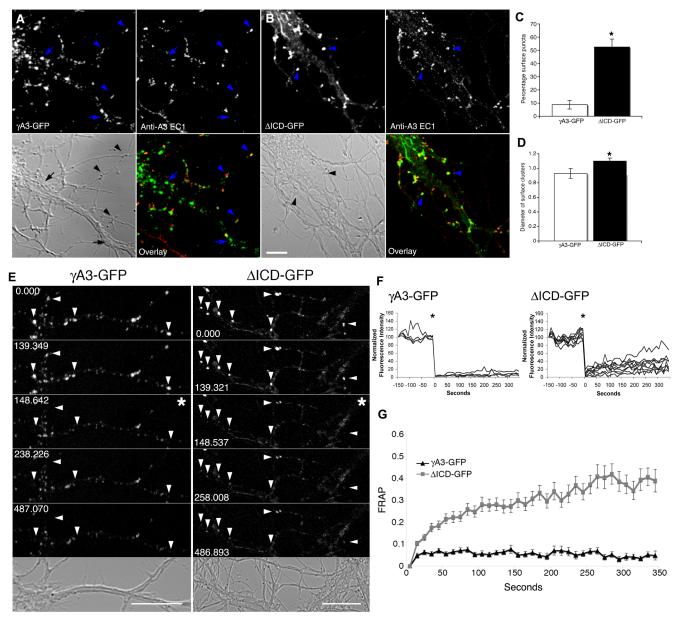

The Pcdh-γ cytoplasmic domain controls surface delivery and trafficking in neurons

We used two approaches to detect the surface accumulation of exogenously expressed Pcdh-γ constructs in transfected neurons. We first detected surface γA3-GFP by using an antibody generated against the first extracellular domain (EC1) of Pcdh-γA3 (anti-γA3-EC1). Isoform-specificity of our antibody was determined by immunofluorescence and immunoblotting (Supplemental Fig. 2). Without permeabilization, the antibody only recognized a subset of puncta (Fig. 4A arrowheads) many of which were located at neurite contact points. Puncta in the somatic and dendritic interior (arrows, Fig. 4A) were unlabeled by the antibody. In contrast, when neurons were permeabilized, almost all γA3-GFP puncta were labeled with anti-γA3 EC1 (Supplemental Fig. 2A, C).

Figure 4. The Pcdh-γ cytoplasmic domain controls delivery of the protein to the membrane.

Neurons were transfected with γA3-GFP (A) or ΔICD-GFP (B) at 14 DIV, fixed and immunolabeled with anti-Pcdh-γA3 EC1 antibody under non-permeabilizing conditions. Immunolabeling with anti-Pcdh-γA3 EC1 in unpermeabilized cells detected some puncta at contact points (arrowheads). Other puncta in the dendritic interior were unlabeled (arrows) indicating an intracellular location. (C) Comparison of the percentage of GFP puncta detected by the extracellular antibody for both constructs. ΔICD-GFP puncta were over 5 times as likely to be on the surface as full-length γA3-GFP (*p<0.001). (D) Comparison of the size of surface GFP puncta for both constructs. ΔICDGFP puncta were 1.2 times larger than full-length γA3-GFP puncta (*p<0.05). Error bars denote S.E.M. (E) Cells were transfected at 14 DIV with the indicated construct and subjected to FRAP analysis. Frames in which puncta were bleached are denoted by an asterisk. Arrowheads denote bleached puncta. (F) Plot of normalized fluorescence intensities of the individual puncta shown in E. (G) Comparison of γA3-GFP and ΔICD-GFP FRAP. ΔICD-GFP puncta recovered to ∼40% of their original fluorescence intensity between 5 and 6 minutes of imaging while γA3-GFP never recovered during this time. Data show average of at least three independent experiments. Error bars denote S.E.M. Bar = 5 μm in A and B. Bar=10 μm in E.

In neurons transfected with ΔICD-GFP, there was a striking reduction in the intracellular pool in dendrites (Fig. 4B). In this case, the majority of dendritic ΔICD-GFP clusters were accessible to anti-γA3-EC1 in unpermeabilized cells and these were frequently found at contact points (arrowheads). Quantification revealed that 52.5 ± 6.0% of the ΔICD-GFP clusters were labeled with anti-γA3-EC1 while only 8.7 ± 3.3% of the full length γA3-GFP puncta were labeled with the external antibody in unpermeabilized cells (Fig. 4C). ΔICD-GFP surface puncta were also larger (1.1 ± 0.04 μm) when compared to surface γA3-GFP puncta (0.9 ± 0.06 μm; p<0.05) (Figure 4D) suggesting that more of the molecule may be stabilized within each punctum.

As a second method to distinguish between full length and intracellular deleted Pcdh-γs, we used fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP). Intracellular organellar profiles, when individually bleached, lack the ability to recover gradually by diffusion, while proteins on the surface are accessible to diffusing molecules within the plane of the plasma membrane and would thus exhibit a gradual recovery of fluorescence after bleaching (Reits and Neefjes, 2001). Neurons were transfected with γA3-GFP or ΔICD-GFP at 14 DIV and analyzed by FRAP at 15 DIV. Multiple stationary puncta for each molecule per neuron were bleached (arrows, Fig. 4E) and recovery of fluorescence was monitored for 5-6 minutes. Representative images and their normalized fluorescence of each construct before and after bleaching are shown in Fig. 4E and F (bleached times are indicated by an asterisk). We found that γA3-GFP never recovered after bleaching while, in contrast, ΔICD-GFP exhibited approximately 40% of recovery during this period (Fig. 4G). Altogether, these results suggest that Pcdh-γ cytoplasmic interactions have the ability to restrict the delivery of the protein to the membrane from an intracellular pool in dendrites.

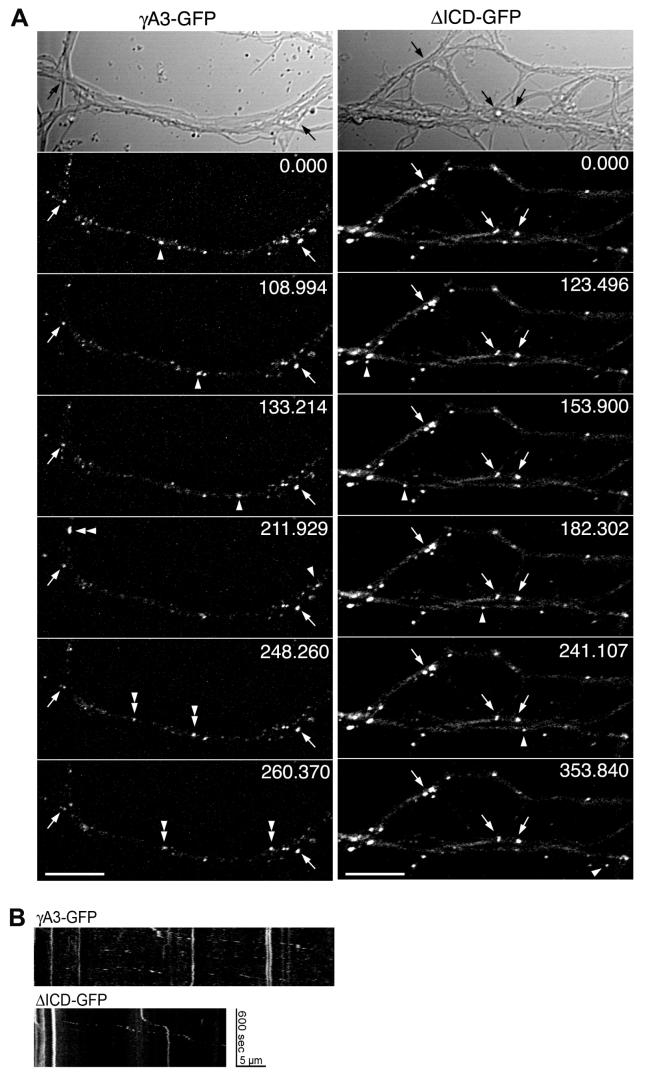

Next we compared the trafficking of γA3-GFP and ΔICD-GFP using time-lapse microscopy in transfected neurons at 15 DIV. In dendritic segments, there were stationary (arrows) and mobile (arrowheads, Fig. 5) Pcdh-γ clusters. The stationary Pcdh-γ clusters were primarily at contact points (arrows). In some cases, γA3-GFP mobile clusters divided or fused (Fig. 5A, double arrowheads; see Movie 1). In contrast, ΔICD-GFP mobile clusters were less abundant and slower (0.58 ± 0.03 μm/s) that those of γA3-GFP (0.72 ± 0.03 μm/s) (p<0.05) (See Movie 2). Kymographs tracking the stationary and mobile clusters of both constructs are shown in Fig. 5B.

Figure 5. Cytoplasmic domain of Pcdh-γ controls intracellular trafficking.

(A) Time lapse imaging of γA3-GFP (left panel) and ΔICD-GFP (right panel) transfected neurons at 15 DIV. Arrowheads denote mobile puncta along the dendrites and arrows show stationary clusters. Velocities of the mobile clusters were determined using the ImageJ Manual Tracking Plug-in (see Materials and Methods). Double arrowhead in left panel denotes a mobile cluster that splits in two mobile clusters. (B) Kymographs of trafficking in dendrites shown in A. Bar = 10 μm.

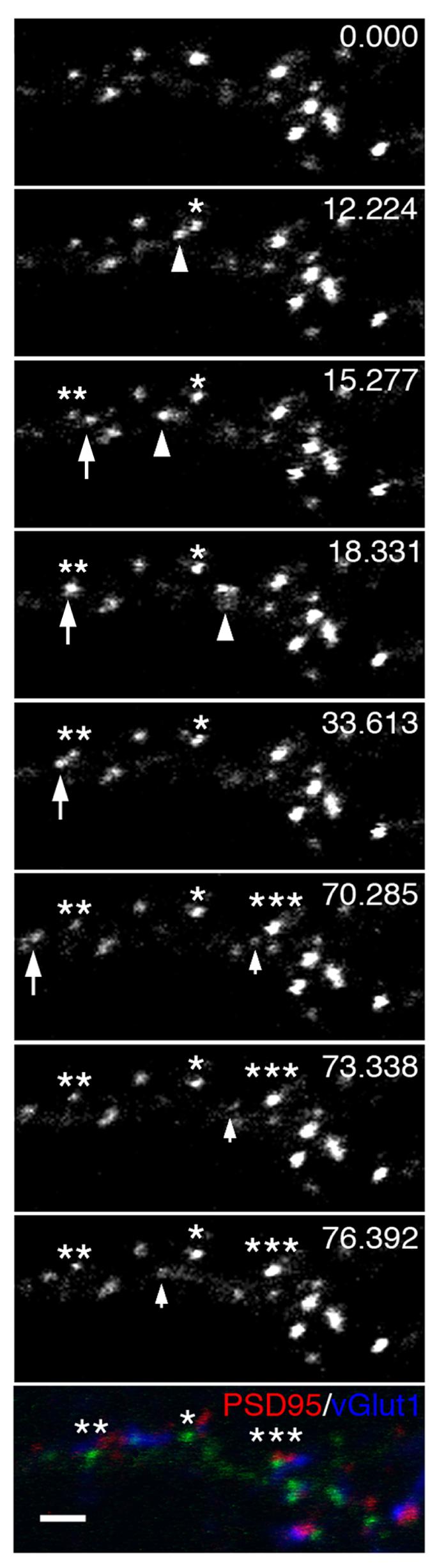

Mobile Pcdh-γ containing organelles bud from and fuse with stationary Pcdh-γ clusters near synapses

We suspected that the intracellular pool of Pcdh-γs must be the route by which Pcdh-γs arrive at their sites at the plasma membrane. This pool partially colocalizes with different markers of transport organelles such as endosomes, Golgi, and endoplasmic reticulum (data not shown). To identify synaptic sites and their relationship to stationary and mobile Pcdh-γ clusters, neurons were fixed after live imaging and immunostained with pre- and postsynaptic markers to identify synaptic sites and their relationship to stationary and mobile Pcdh-γ clusters (Fig. 6). We identified several immobile γA3-GFP clusters (single, double and triple asterisks) adjacent to vGlut1 and PSD-95 positive sites (bottom panel, Fig. 6). In this series, three γA3-GFP positive packets budded off or fused with these synaptic associated puncta. In the first case, a transport packet (arrowhead) originated from a stationary cluster (single asterisk; 12.224 seconds), moved in an anterograde direction (15.277 seconds) and then reversed direction (18.331 seconds) and left the field. In the second case, a mobile packet (arrow) fused with a stationary site (double asterisk, 18.331 seconds), remained for approximately 15 seconds, and then budded off the stationary site (33.613 seconds). In the third case, a mobile packet (small arrow) budded off another stationary site (triple asterisk, 70.285 seconds). The movie is attached as supplemental data (Movie 3).

Figure 6. Mobile Pcdh-γ puncta exchange with stationary sites near synaptic specializations.

Time lapse imaging of γA3-GFP at 15 DIV followed by retrospective immunostaining (bottom panel) for PSD-95 (red channel) and vGlut1 (blue channel). A mobile punctum (arrowhead) separates from a stationary site (asterisk) and moves along the dendrite. A separate mobile punctum (large arrow) pauses on or near another stationary punctum (double asterisk) before leaving this site (large arrow). Another mobile punctum separates from an additional stationary site (triple asterisks). The relationship of the three stationary sites that receive or emit mobile Pcdh-γ containing punctum and synaptic markers is shown in the bottom panel. Bar = 2 μm.

Post-fixation and permeabilization immunostaining with PSD-95 (red channel) and vGlut1 (blue channel) antibodies showed that the three stationary clusters were associated with synaptic sites. Thus our results suggest that Pcdh-γs, highly clustered on the dendrite, arrive at clusters and move from cluster to cluster via intracellular transport organelles.

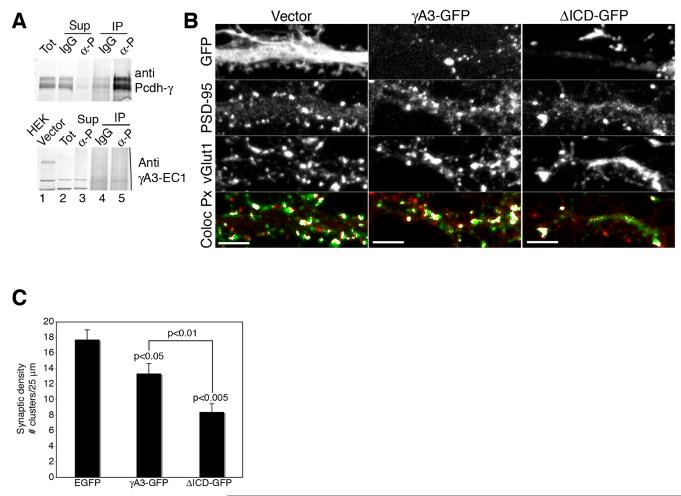

A single Pcdh-γ isoform affects synaptic development

Pcdh-γs have been thought to function as synaptic adhesion or recognition proteins that, through their differential regulation in individual cells, specify synaptic connections (Frank and Kemler, 2002; Shapiro and Colman, 1999). We first determined if cultured hippocampal neurons express endogenous Pcdh-γA3 by using immunoprecipitation with the antibody against the Pcdh-γ constant domain. The antibody pulls down almost the entire pool of Pcdh-γ present in the cells as shown by immunoblotting of these immunoprecipitates and their supernatants with the Pcdh-γ antibody (upper panel, Fig. 7A). However, immunoblot for Pcdh-γA3 showed undetectable levels of this isoform in the immunoprecipitate (lower panel, Fig. 7A). We expressed γA3-GFP and ΔICDGFP constructs in hippocampal neurons during advanced synaptogenesis stages (15 DIV plus 3 DIV after transfection). The neurons were then fixed and immunolabeled for pre- and postsynaptic markers (Fig. 7B) and the number of excitatory synaptic specializations was quantified (Fig. 7C). When γA3-GFP was expressed in neurons, the number of synapses per 25 μm segment of dendrite was decreased by 24% relative to the EGFP transfected control (Fig. 7C). When ΔICD-GFP was expressed, a more dramatic reduction in the number of synapses was observed (56%) relative to the EGFP transfected control.

Figure 7. Overexpression of Pcdh-γA3 or its cytoplasmic deleted version reduces synaptic density.

(A) Cultured hippocampal neurons were lysed and subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with an antibody against the constant domain of Pcdh-γs (α-P) or control IgGs (IgG) followed by immunoblot with the same antibody (upper panel) or an antibody specific for the Pcdh-γA3 extracellular domain (γA3-EC1, lower panel). Total lysates (Tot) or HEK293 cells transfected with Pcdh-γA3 (HEK vector) were used as positive controls for the immunoblot (lane 1, upper and lower panel, respectively). (Upper panel) Almost all Pcdh-γs were immunoprecipitated as indicated by the absence of signal in the supernatant (Sup, lane 3). Pcdh-γA3 is undetectable in the immunoprecipitates (lower panel, lane 5) even though Pcdh-γs are highly enriched in this fraction (upper panel, lane 5). (B) Neurons were transfected at 15 DIV with EGFP as control, γA3-GFP or ΔICD-GFP, fixed after 3 days in culture and immunolabeled for PSD-95 and vGlut1. Representative images are shown. PSD-95/vGlut1 colocalized pixels (in white) indicate excitatory synaptic specializations. Bars = 5 μm. (C) Quantification of number of juxtaposed pre- and postsynaptic specializations per 25 μm dendritic segment. At least 9 cells were for each transfection and 2-5 dendrites per cell were quantified. Error bars denote S.E.M.

Discussion

Synaptic adhesion molecules are presumed to function primarily by adhering pre- and postsynaptic membranes together and anchoring other synaptic proteins through cytoplasmic interactions. These molecules could also mediate synaptic specificity through homophilic binding. The Pcdhs in particular have been good candidates to fit this model because of their large number of isoforms, their differential expression within otherwise similar neuronal populations (Wang et al., 2002b) and their obvious similarities to the classical cadherins (Kohmura et al., 1998; Wu and Maniatis, 1999), which are known to exhibit strong and specific homophilic binding. However, since their discovery, the cell biological activity of the Pcdhs in neural cells has proven elusive as their adhesive activity is difficult to detect in conventional assays (Morishita et al., 2006; Obata et al., 1995) and the binding partners of their cytosolic domains, particularly for the Pcdh-γs, are relatively unknown. In the present work, we shed new light on these discrepancies. We show that Pcdh-γs accumulate specifically during development at axonal and dendritic cell contacts in neurons consistent with a role in cell-cell interactions. We further demonstrated for the first time their homophilic properties. We reveal here the first indication that the cytoplasmic domain tightly controls intracellular trafficking and delivery of Pcdh-γs to the plasma membrane. Based on our observations, we speculate that the role of Pcdh-γs in cell-cell interactions may be more regulated than that or other adhesion molecules such as classical cadherins; their action may be of a transient nature at specific points in development.

Pcdh-γ adhesive activity has been difficult to detect using assays that are the standard for evaluating activity of putative adhesion molecules and, because of this, there have been reservations about the role of Pcdh-γs as recognition/adhesion molecules (Jontes and Phillips, 2006; Morishita and Yagi, 2007; Wang et al., 2002b). The earliest studies of Pcdh-γ activity noted that Pcdh-γC4 lacked adhesive activity but when the cytoplasmic domain of this Pcdh was replaced with that of N-cad, adhesive activity was detectable (Obata et al., 1995). More recently, Pcdh-γ adhesive activity was detectable using HEK 293 and K562 cells although to a lesser extent than N-cad and lacking the extensive accumulation at cell-cell contacts that is a hallmark of adhesive molecules (Frank et al., 2005; Reiss et al., 2006). We suspected that the lack of adhesive activity of the Pcdh-γs might be due to the extensive intracellular accumulation of the protein in these cellular models. We removed the intracellular domain of the Pcdh-γs and found a robust accumulation at cell-cell contacts. Taking advantage of this approach we performed co-culture assays that allowed us to demonstrate their homophilic properties. These results suggest that Pcdh-γs probably function as mediators of cell-cell interactions in neurons and that the cytoplasmic domain, which may mediate the sequestration of Pcdh-γs intracellularly, tightly regulates this activity.

We previously proposed a model in which preformed synapses are specifically selected via trafficking of recognition molecule-containing organelles (Jontes and Phillips, 2006). It is unlikely that Pcdh-γs are involved in generating an adhesive linkage between pre- and postsynaptic membranes or other adhesive sites on neurons in a structural sense. Loss or reduction of Pcdh-γ activity in vivo results in fewer numbers of synapses and in reduced amplitude of spontaneous synaptic transmission (Wang et al., 2002b; Weiner et al., 2005), and cell death (Lefebvre et al., 2008; Prasad et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2002b; Weiner et al., 2005) but synaptogenesis still occurs in these mice indicating Pcdh-γs might participate in a late event in synapse development rather than the initial formation of synaptic junctions. Their abundance within intracellular compartments and pattern of transport within dendrites is more consistent with the idea that Pcdh-γs randomly assemble at points of existing contact generated by other adhesive mechanisms and perhaps modify these sites upon appropriate cell-cell interaction.

We observed differences in velocity and abundance of Pcdh-γ trafficking organelles when we deleted the cytoplasmic domain. These differences in velocity and abundance between the full-length and cytoplasmic deleted mobile clusters might be due to a defect in one of the steps in the trafficking pathway between the ER, Golgi and membrane, which is known to be active in dendrites (Aridor et al., 2004; Horton and Ehlers, 2003). It is possible that the effects of deleting the intracellular domain might be a result of loss of an organelle retention signal located in the cytoplasmic domain of the protein and/or a decrease in endocytosis of the protein accumulated in the membrane. These possibilities are currently being addressed. Regardless of the exact mechanism of intracellular transport, our findings suggest that intracellular trafficking is a prominent feature of Pcdh-γs and is directly tied to how their cell surface function is regulated.

Finally, we show that over-expression of a single isoform of Pcdh-γs had a significant effect on synapse density. These results can be interpreted from a dominant-negative point of view. Our cultures of hippocampal neurons do not express detectable levels of the γA3 isoform. Thus, the over-expression of this Pcdh-γ isoform in neurons may interfere with the expression, trafficking, or function of endogenous Pcdh-γ isoforms. This might reduce synapse density if Pcdh-γs are involved in maintenance of synaptic contacts. The fact that the surface targeted ΔICD-GFP construct had the greatest effect implicates cell surface interaction as the mode behind the synaptic effect of Pcdh-γ over-expression. Our results would then be consistent with those previously published (Wang et al., 2002b; Weiner et al., 2005) in which synapse density and function was reduced in spinal cord and in cultured spinal cord neurons (Weiner et al., 2005). However, more recently, conditional knockouts suggest that Pcdh-γs may not be necessary for development of normal synapse numbers in the retina (Lefebvre et al., 2008). It remains to be determined if the phenotypes observed in the genetic deletion studies are attributable to the cell-cell interaction activity of Pcdh-γs reported here or to another unidentified function of these molecules.

Experimental Methods

Antibodies

The polyclonal affinity purified rabbit antibody that recognizes the constant domain of mouse and rat Pcdh-γs was described previously (Phillips et al., 2003). Affinity purified antibodies to the intracellular domain of mouse N-cadherin have also been described (Tanaka et al., 2000). For recognition of the extracellular moiety of Pcdh-γA3, an antibody was generated to a peptide in the first extracellular cadherin repeat (EC1) of mouse Pcdh-γA3. The peptide sequence was EDKLKIFEVEVDISDIND. Peptide synthesis, antisera production and affinity purification was performed by Open Biosystems, Inc. Antibodies recognizing the extracellular domains of Pcdh-γB2 and Pcdh-γC4 were generously provided by Dr. Joshua Weiner (Department of Biological Sciences, University of Iowa). The following antibodies were obtained commercially, MAP2 (Covance), ankyrin B (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), vGlut1 (Millipore/Chemicon), PSD-95 (Affinity Bioreagents). Fluorescent secondary antibodies were obtained from Invitrogen/Molecular Probes and Jackson Labs.

cDNA constructs

Mouse Pcdh-γA3 in pEGFP-N1 was described previously (Phillips et al., 2003). The XbaI site at 1313 base pairs from the translation start site was mutated without changing the amino acid sequence rendering the other XbaI site at 2357 base pairs unique. To produce intracellular deleted Pcdh-γA3 (ΔICD-GFP), the plasmid was digested with XbaI, blunted with mung bean nuclease, digested next with AgeI, blunted with Klenow, and then ligated. To produce the constant domain deletion of Pcdh-γA3 (Δconst-GFP), the variable intracellular domain of Pcdh-γA3 was amplified by PCR including XbaI and AgeI sites for subcloning into the XbaI and AgeI sites of Pcdh-γA3-GFP. Pcdh-γB2-YFP and Pcdh-γC4-YFP were generously provided by Dr. Joshua Weiner (Department of Biological Sciences, University of Iowa). Intracellular deletion of these were generated by amplifying sequences corresponding to the signal sequence/extracellular domain, the transmembrane domain, and the first 26 amino acids of the intracellular domain by PCR using primers for subcloning in frame into the Xho1 and EcoRI sites in pEGFP-N1.

Neuronal cultures

Hippocampi were dissected from E18 rat embryos and cells dissociated with trypsin as described (Banker and Goslin, 1991). Neurons were plated at 0.9-1.0 x 104 cells/cm2 onto poly-L-lysine–coated coverslips or 35 mm glass bottomed Petri dishes (MatTek Corporation) and cultured in Neurobasal medium including B27 supplements (Invitrogen) for periods ranging from 2 days in vitro (DIV) to 21 DIV. Cells were maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

Transfection

HEK293 cells were grown in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum. Cells were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the recommended protocol. Cells were then grown for 1-2 days posttransfection, fixed and mounted for fluorescent microscopy. Primary neurons were transfected at the indicated DIV using calcium phosphate precipitation as described (Okamura et al., 2004).

Immunostaining

Neurons were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/4% sucrose in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), blocked in 3% normal goat serum and 3% bovine serum albumin in PBS. For immunostaining with permeabilization, 0.1% Triton X-100 was included in blocking, incubation and wash solutions.

Imaging

Images were obtained with a Zeiss LSM510 META confocal microscope. Double and triple label images were acquired in multi-track mode at 4 times line averaging with a 63x/1.4 oil DIC objective. For time-lapse microscopy, cells transfected with GFP fusion constructs in a glass bottom 35 mm dishes were placed in live imaging buffer (in mM: 146 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 0.6 MgSO4, 1.6 NaHCO3, 0.15 NaH2PO4, 8 Glucose. 20 Hepes, pH=7.4) and held at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in the live imaging chamber mounted on the Zeiss LSM510 META. Simultaneous DIC images were collected. Movies were analyzed in Zeiss AIM software and ImageJ. In some cases, cells were fixed after live imaging and immunostained with antibodies to synaptic markers.

For Fluorescence Recovery After Photobeaching (FRAP), at least 10 puncta of approximately 1.5-2 μm of diameter were selected within a dendritic segment. Cells were imaged before bleaching every 10 seconds for 15 frames (prebleaching). After bleaching with 15 iterations of laser pulses at maximum power, regions were imaged every 10 seconds for approximately 5 minutes. Signal intensities in the bleached regions were measured with the LSM510 AIM software and normalized to a non-bleached region and the background. The amount of recovery (FRAP) was calculated as the ratio of the measured fluorescence in the bleached area (Ft) minus the fluorescence of the same field immediately after bleaching (F0), divided by the difference between the initial intensity of the field (Fi) before photobleaching and F0 (FRAPt = Ft-F0/Fi-F0).

Image analysis

Comparison of the percentage and size of surface puncta for γA3-GFP and ΔICD-GFP was done as follows: 5 neurons transfected at DIV 12 with each construct were immunostained with anti-Pcdh-γA3 EC1 antibodies and anti-rabbit Alexa 568 conjugated secondary antibodies without permeabilization. Images of the red and green channels were opened in ImageJ, converted to 8 bit grayscale and thresholded to eliminate background and obtain defined puncta. A GFP punctum was considered labeled with anti-γA3-EC1 if three continuous pixels of label overlapped with the GFP signal. The numbers and sizes of surface puncta were determined blindly. Only dendritic puncta were considered. Puncta size was determined by measuring the longest diameter of the punctum.

Density of synapses in transfected neurons were determined using ImageJ with the Colocalization Finder plug-in (Christophe Laummonerie, Jerome Mutterer, Institut de Biologie Moleculaire des Plantes, Strasbourg, France) to identify the functional synapses. Only colocalized pixels between the postsynaptic marker PSD-95 and the presynaptic excitatory marker vGlut1 were counted and measured.

Velocity of mobile clusters was determined using the ImageJ plug-in Manual Tracking (Fabrice P. Cordelieres, Institute Curie, Orsay, France). Clusters covering distances along dendrites were tracked frame by frame. Only velocities of clusters moving distances of more than 2 μm between frames were averaged.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Deanna Benson, James Jontes, Joshua Weiner, Hidekazu Tanaka, Tatiana Boiko, Marcus Frank, Ingrid Haas and Bill Janssen for valuable comments and suggestions and Joshua Weiner, Marcus Frank, and Hidekazu Tanaka for providing reagents. Supported by NS051238 and an Irma T. Hirschl Research Award to GRP.

References

- Aridor M, Guzik AK, Bielli A, Fish KN. Endoplasmic reticulum export site formation and function in dendrites. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3770–3776. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4775-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banker G, Goslin K. Culturing nerve cells. The MIT Press; London: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bonn S, Seeburg PH, Schwarz MK. Combinatorial expression of alpha- and gamma-protocadherins alters their presenilin-dependent processing. Molecular and cellular biology. 2007;27:4121–4132. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01708-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esumi S, Kakazu N, Taguchi Y, Hirayama T, Sasaki A, Hirabayashi T, Koide T, Kitsukawa T, Hamada S, Yagi T. Monoallelic yet combinatorial expression of variable exons of the protocadherin-alpha gene cluster in single neurons. Nature genetics. 2005;37:171–176. doi: 10.1038/ng1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank M, Ebert M, Shan W, Phillips GR, Arndt K, Colman DR, Kemler R. Differential expression of individual gamma-protocadherins during mouse brain development. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005;29:603–616. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank M, Kemler R. Protocadherins. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14:557–562. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00365-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas IG, Frank M, Veron N, Kemler R. Presenilin-dependent processing and nuclear function of gamma-protocadherins. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:9313–9319. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412909200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton AC, Ehlers MD. Dual modes of endoplasmic reticulum-to-Golgi transport in dendrites revealed by live-cell imaging. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6188–6199. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-15-06188.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jontes JD, Phillips GR. Selective stabilization and synaptic specificity: a new cell-biological model. Trends in neurosciences. 2006;29:186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohmura N, Senzaki K, Hamada S, Kai N, Yasuda R, Watanabe M, Ishii H, Yasuda M, Mishina M, Yagi T. Diversity revealed by a novel family of cadherins expressed in neurons at a synaptic complex. Neuron. 1998;20:1137–1151. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80495-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre JL, Zhang Y, Meister M, Wang X, Sanes JR. {gamma}-Protocadherins regulate neuronal survival but are dispensable for circuit formation in retina. Development (Cambridge, England) 2008;135:4141–4151. doi: 10.1242/dev.027912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishita H, Umitsu M, Murata Y, Shibata N, Udaka K, Higuchi Y, Akutsu H, Yamaguchi T, Yagi T, Ikegami T. Structure of the cadherin-related neuronal receptor/protocadherin-alpha first extracellular cadherin domain reveals diversity across cadherin families. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:33650–33663. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603298200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishita H, Yagi T. Protocadherin family: diversity, structure, and function. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obata S, Sago H, Mori N, Rochelle JM, Seldin MF, Davidson M, John T, Taketani S, Suzuki ST. Protocadherin Pcdh2 shows properties similar to, but distinct from, those of classical cadherins. J Cell Sci. 1995;108:3765–3773. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.12.3765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura K, Tanaka H, Yagita Y, Saeki Y, Taguchi A, Hiraoka Y, Zeng LH, Colman DR, Miki N. Cadherin activity is required for activity-induced spine remodeling. The Journal of cell biology. 2004;167:961–972. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200406030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips GR, Huang JK, Wang Y, Tanaka H, Shapiro L, Zhang W, Shan WS, Arndt K, Frank M, Gordon RE, Gawinowicz MA, Zhao Y, Colman DR. The presynaptic particle web: ultrastructure, composition, dissolution, and reconstitution. Neuron. 2001;32:63–77. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00450-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips GR, Tanaka H, Frank M, Elste A, Fidler L, Benson DL, Colman DR. Gamma-protocadherins are targeted to subsets of synapses and intracellular organelles in neurons. J Neurosci. 2003;23:5096–5104. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-12-05096.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad T, Wang X, Gray PA, Weiner JA. A differential developmental pattern of spinal interneuron apoptosis during synaptogenesis: insights from genetic analyses of the protocadherin-{gamma} gene cluster. Development (Cambridge, England) 2008;135:4153–4164. doi: 10.1242/dev.026807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss K, Maretzky T, Haas IG, Schulte M, Ludwig A, Frank M, Saftig P. Regulated ADAM10-dependent ectodomain shedding of gamma-protocadherin C3 modulates cell-cell adhesion. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:21735–21744. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602663200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reits EA, Neefjes JJ. From fixed to FRAP: measuring protein mobility and activity in living cells. Nature cell biology. 2001;3:E145–147. doi: 10.1038/35078615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro L, Colman DR. The diversity of cadherins and implications for a synaptic adhesive code in the CNS. Neuron. 1999;23:427–430. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80796-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H, Shan W, Phillips GR, Arndt K, Bozdagi O, Shapiro L, Huntley GW, Benson DL, Colman DR. Molecular modification of N-cadherin in response to synaptic activity. Neuron. 2000;25:93–107. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80874-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Su H, Bradley A. Molecular mechanisms governing Pcdh-gamma gene expression: Evidence for a multiple promoter and cis-alternative splicing model. Genes Dev. 2002a;16:1890–1905. doi: 10.1101/gad.1004802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Weiner JA, Levi S, Craig AM, Bradley A, Sanes JR. Gamma protocadherins are required for survival of spinal interneurons. Neuron. 2002b;36:843–854. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01090-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner JA, Wang X, Tapia JC, Sanes JR. Gamma protocadherins are required for synaptic development in the spinal cord. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:8–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407931101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, Maniatis T. A striking organization of a large family of human neural cadherin-like cell adhesion genes. Cell. 1999;97:779–790. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80789-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.