Abstract

Background: Loss of control (LOC) eating in youth predicts excessive weight gain. However, few studies have measured the actual energy intake of children reporting LOC eating.

Objective: The objective was to characterize the energy intake and macronutrient composition of “normal” and “binge” laboratory meals in nonoverweight and overweight boys and girls with LOC eating.

Design: Children aged 8–17 y (n = 177) consumed 2 lunchtime meals ad libitum from a multi-item food array after being instructed to either binge eat (binge meal) or to eat normally (normal meal). Prior LOC eating was determined with a semistructured clinical interview.

Results: Participants consumed more energy at the binge meal than at the normal meal (P = 0.001). Compared with youth with no LOC episodes (n = 127), those reporting LOC (n = 50) did not consume more energy at either meal. However, at both meals, youth with LOC consumed a greater percentage of calories from carbohydrates and a smaller percentage from protein than did those without LOC (P < 0.05). Children with LOC ate more snack and dessert-type foods and less meats and dairy (P < 0.05). LOC participants also reported greater increases in postmeal negative affect at both meals than did those without LOC (P ≤ 0.05). Secondary analyses restricted to overweight and obese girls found that those with LOC consumed more energy at the binge meal (P = 0.025).

Conclusions: When presented with an array of foods, youth with LOC consumed more high-calorie snack and dessert-type foods than did those without LOC. Further research is required to determine whether habitual consumption of such foods may promote overweight. This trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov as NCT00320177.

INTRODUCTION

Binge eating disorder (BED), presently a form of “eating disorder not otherwise specified” listed in the appendix of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV–Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) (1), is characterized by recurrent episodes of binge eating without regular compensatory behaviors. A binge-eating episode is defined as the consumption of a large amount of food during which a sense of loss of control (LOC) over eating is experienced. To meet the criteria for BED, individuals must engage in an average of ≥2 episodes of binge eating per month for ≥6 mo (1). BED is common among obese adults. Few children meet criteria for BED. However, youth commonly report binge eating episodes with less frequency than required to meet the criteria for BED (2). One laboratory meal study conducted by Mirch et al (3) investigated binge eating behavior in children. Sixty overweight boys and girls aged 6–12 y, who had agreed to participate in a weight-loss study, self-reported on a questionnaire whether they had engaged in binge eating at least once in the past 6 mo. Children ate ad libitum from a 9835-kcal buffet meal on 2 separate occasions: after an overnight fast and after a standardized breakfast. At both meals, binge eating children (n = 10) consumed >400 kcal more in energy than did children with no binge eating episodes (n = 50). To our knowledge, no studies have examined binge eating behavior in the laboratory among both overweight and nonoverweight youth.

LOC eating—defined as the experience of loss of control while eating, regardless of whether the reported amount of food consumed is unambiguously large—is common in youth (2). LOC eating includes both binge episodes and eating episodes during which the amount consumed may be less clearly considered large. Most of the literature on pediatric LOC eating describes children who report at least one episode in the month before assessment (2). LOC eating is associated with elevated eating-related and psychological distress (4–6), with overweight, and with high body fat mass (7, 8). Both reported binge (9–11) and LOC (12) eating in youth predict excessive body weight gain in longitudinal studies of children and adolescents of all weight strata. Thus, it is possible that reported LOC eating is an important construct among all children who report such episodes because, regardless of weight status, the behaviors may have an adverse impact on outcome.

We therefore carried out a laboratory feeding paradigm to extend Mirch et al's (3) study by including male and female children and adolescents aged 8–18 y with a broad range of body weights and studying the impact of reported LOC eating, as opposed to binge eating exclusively, on actual food intake. The study protocol was modeled after adult paradigms (13) in which participants completed 2 separate meals: one where they were told to eat normally and another where they were instructed to binge eat. On the basis of prior literature (3, 13), we hypothesized that after accounting for the contribution of body composition, compared with participants without LOC eating, those reporting LOC would consume more energy during the binge meal. Given that youth frequently report a negative affect after meals that involve the experience of LOC (14), we also studied the affect of participants immediately after eating. We expected that those with LOC would report greater increases in negative emotions after the binge meal.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Participants

Participants were healthy volunteers recruited for this study through flyers posted on public bulletin boards at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and at local libraries, supermarkets, and school parent E-mail listservs in the Washington, DC, greater metropolitan area. The study was also advertised in a local newspaper and posted on free websites (eg, Craig's List and Backfence). The flyer and advertisement explained that the study was investigating eating behaviors in youth and that no treatment would be provided. Children and adolescents were financially compensated for their participation. Boys and girls of any race or ethnicity who had a BMI ≥ 5th percentile for age and sex (15) were eligible for participation. Individuals were excluded if they had a significant medical condition; had abnormal hepatic, renal, or thyroid function; were taking medication known to affect body weight; or had a psychiatric disorder that might impede protocol compliance. Pregnant girls were not eligible for the study, nor were children who had lost >5 lb (2.3 kg) in the past 3 mo or who were undergoing weight-loss treatment. Individuals were excluded if they reported disliking >50% of the foods to be offered on the test meal buffet or if they were unable to acclimate to laboratory conditions, by virtue of being unable to consume at least half of a high-calorie shake. Youth provided written assent and parents gave written consent for participation in the study. This study was approved by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Institutional Review Board. Data were collected between February 2004 and June 2008.

Procedures

Each subject participated in 3 visits on 3 separate days at the Hatfield Clinical Research Center at the NIH.

Visit 1: screening

At the first visit, children were screened for eligibility after fasting overnight. Participants and their parent or guardian were informed that the study was to better understand eating behaviors in children. Each participant's weight and height were measured by using calibrated electronic instruments as described previously (16). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (in kg) divided by the square of height (in m). BMI SD scores (BMI z scores) were calculated according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2000 growth charts (17). Body composition was measured as previously described (16, 18) via air-displacement plethysmography (Life Measurement Inc, Concord, CA) to determine fat-free mass and fat mass. All participants underwent a medical history and a physical examination performed by an endocrinologist or a trained nurse practitioner. Breast and pubertal hair development were assigned according to the stages of Tanner (19, 20), and testicular volume was measured (in mL) according to Prader (21).

To acclimate children to the test meal condition, each participant was placed in a private room in the pediatric clinic, provided with a high-calorie shake (787 kcal; 52% of energy as carbohydrate, 11% as protein, and 37% as fat; Axcan Pharma Inc, Birmingham, AL), and given the tape-recorded instruction to “eat as much as you would at a normal meal.” If a child was unable to consume ≥50% of the shake under these conditions, they were considered unable to acclimate and were deemed ineligible.

The Eating Disorder Examination (EDE), version 12OD/C.2 (22), or the EDE adapted for children (23) was administered to each participant to determine the presence or absence of LOC eating as described previously (8, 14). The child version of the EDE differs from the adult version only in that its script has been edited to make it more accessible to children aged 8–14 y. On the basis of their responses to the EDE, participants were categorized as engaging in objective binge episodes (overeating with LOC), subjective binge episodes (LOC without objective overeating as assessed by the interviewer, but viewed as excessive by the interviewee), objective overeating (overeating without LOC), or no episode (a normal meal involving neither LOC nor overeating) over the 28 d before assessment. Eating episodes were assessed by asking children to describe the largest amount of food consumed in the past month. A book of photographed food portions in various sizes and types (24) was used during every interview to assist participants in determining the amount and variety of food consumed during the episode. At weekly meetings, team members discussed the amount of food eaten and came to a unanimous consensus regarding whether the amount was unambiguously large (eg, 8 slices of pizza) or subjectively large (eg, 2 slices of pizza) given the circumstances for the child's age. If one or more team members disagreed with the rest of the group, an outside team proficient at administering both the EDE and the child version was contacted for further input. If, in the final analysis, an episode size was still questionable, it was coded conservatively as not unambiguously large. For the purposes of the current study, participants reporting at least one instance of an objective or a subjective binge episode in the past month were categorized as those with LOC eating. Children with objective overeating or no episodes over the month before assessment were categorized as those without LOC eating.

The EDE has good interrater reliability for all episode types (Spearman correlation coefficients: ≥0.70) (25). Tests of the EDE adapted for children have shown good interrater reliability (Spearman rank correlations from 0.91 to 1.00) and discriminant validity in eating disordered samples and matched control subjects aged 8–14 y (26). Among nonoverweight and overweight 6–13-y-olds, the child version of the EDE showed excellent interrater reliability with a Cohen's kappa for presence of the different eating episode categories of 1.00 (P < 0.001) (8).

To ensure that participants found the foods offered at the buffet test meals to be acceptable, participants completed a food preference questionnaire on which they rated how much they liked 57 foods that children commonly consume (27) (including the 28 foods offered on our buffet) using 10-point Likert scales (28).

Visits 2 and 3: buffet test meals

Participants were asked to consume their lunch ad libitum from a multiple-item buffet test meal on 2 separate days, scheduled ≥2 d apart. Children were randomly assigned to complete either the “normal” meal (at which they were told to “eat as much as you would at a normal meal”) or the “binge” meal (during which they were instructed to “let yourself go and eat as much as you want”) first. Participants were instructed to adhere to an overnight fast initiated at 2200 the night before each test meal visit. At each test meal day, participants were instructed to consume an entire standard breakfast consisting of 288 kcal (240 mL apple juice, 1 English muffin, and 6 g butter) at 0840. After the breakfast, each subject remained at the NIH, participating in sedentary activities (eg, playing computer games, reading, and doing arts and crafts), and was observed to ensure that there was no food intake until the afternoon test meal.

At 1430, each child was presented with a 9835-kcal buffet test meal (3) with individual items that varied in macronutrient composition (12% protein, 51% carbohydrate, and 37% fat across all foods) and contained a wide assortment of foods (Table 1). When each child entered the room containing the buffet, the following tape-recorded instruction was played for the normal meal: “Eat as much as you would at a normal meal”; for the binge meal, the following tape-recorded instruction was played: “Let yourself go and eat as much as you want.” Participants were then left alone in the room containing the buffet to eat ad libitum. During the test meals, children viewed pretaped episodes of a television show with commercials removed. Episodes were previewed so that none involved food-, eating-, shape-, or weight-related topics. Participants were instructed to open the room door when they were finished eating. Time spent eating was measured from the time the investigator left the room to the time the participant opened the door after eating. The amount of each food and beverage consumed was measured by using the differences in weight of each food item before and after the meal. Energy content and nutrient composition for each food were determined according to a metabolic diet study management system that uses the US Department of Agriculture Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, release 16 (Viocare Technologies Inc, Princeton, NJ), as well as nutrient information supplied by food manufacturers.

TABLE 1.

Energy content of meal items by food groups presented at the buffet test meals

| Item | Energy |

| kcal | |

| Dairy | |

| 240 g American cheese | 901.1 |

| 850 g 2% milk | 422.2 |

| Desserts and snacks | |

| 12 Sandwich cookies1 | 566.4 |

| 12 Vanilla wafer cookies | 206.3 |

| 120 g Tortilla chips | 601.2 |

| 150 g Pretzels | 571.5 |

| 120 g Jellybeans | 440.4 |

| 120 g Chocolate candy2 | 590.4 |

| Meats | |

| 180 g Ham | 216.0 |

| 180 g Turkey | 282.6 |

| 200 g Chicken nuggets | 550.8 |

| Vegetables | |

| 200 g Tomatoes | 42.0 |

| 50 g Lettuce | 6.0 |

| 200 g Baby carrots | 76.0 |

| Fruit | |

| 3 Medium bananas | 325.7 |

| 250 g Grapes | 177.5 |

| 3 Medium oranges | 184.7 |

| Bread | |

| 12 Slices white bread | 801.0 |

| Condiments | |

| 120 g Peanut butter | 711.6 |

| 120 g Grape jelly | 339.6 |

| 90 g Mayonnaise | 645.1 |

| 90 g Mustard | 59.4 |

| 90 g Light ranch dressing | 240.0 |

| 90 g Barbeque sauce | 67.5 |

| 250 g Mild salsa | 70.0 |

| Drinks | |

| 850 g Bottled water | 0.0 |

| 850 g Apple juice | 400.0 |

| 850 g Lemonade | 340.0 |

| Total | 9835 |

Oreos (Kraft Foods, Northfield, IL).

M&M's (Mars Inc, Hackettstown, NJ).

Immediately before, and again after, each test meal, participants completed the psychometrically sound State Form of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (29), which measures anxiety “right now, at this very moment.” They also completed the well-validated Brunel Mood Scale (30), which measures present mood state and generates 6 subscales pertaining to anger, confusion, depression, fatigue, tension, and vigor.

Statistical methods

All analyses were performed with SPSS 14.0 (31). Data were screened for univariate and multivariate normality. There were no influential outliers. Logarithmic transformations were made for total energy intake and fat-free mass, and arcsine transformations were conducted for the percentage of macronutrient content (fat, protein, and carbohydrate) intake. Pre- and postmeal mood states, as assessed by the Brunel Mood Scale, were mean rank transformed to achieve normality.

Primary hypotheses were examined with a series of linear mixed models with repeated measures. The dependent variables were total energy intake (kcal), percentage of energy intake from protein, carbohydrate, and fat, food groups (dairy, desserts/snacks, meats, vegetables, fruit, bread, condiments, and drinks), duration of eating (in min), postmeal state anxiety, and postmeal state anger, confusion, depression, fatigue, tension, and vigor. The fixed-factor main effects in the model were LOC (presence or absence of at least one episode in the month preceding assessment) and meal type (normal, binge). We also tested the 2-factor interaction between LOC and meal type to determine whether any observed effects of LOC significantly varied between the normal meal and the binge meal. Each model included sex, age, race (coded non-Hispanic white and all other racial-ethnic minorities), fat-free mass, and percentage fat mass as covariates. For the models predicting duration of eating and postmeal state anxiety and mood, total energy intake also was included as a covariate. Pretest meal anxiety or mood state was included in the models predicting posttest meal anxiety and mood states. Randomization order was also considered as a covariate in all analyses, but was removed because it did not significantly contribute to any model. Reported means ± SEs were adjusted for all variables included in each model. Differences were considered significant when P values were ≤0.05, and all tests were 2-tailed.

RESULTS

One hundred ninety-eight children and adolescents attended a screening appointment. A total of 19 children did not complete all of the study procedures for the following reasons: 9 were unable to consume ≥50% of the high-calorie shake and were excluded, 4 did not schedule their test meal visits within 6 mo of the screening appointment, 2 scheduled test meal appointments but did not attend, and 4 children decided not to continue the study but did not provide a reason. Of the 179 participants who completed both test meals, the data from 2 children were excluded because one child did not eat at the test meals and the other did not follow study procedures. Compared with children who did not complete the study in its entirety, completers were significantly older (13.9 ± 2.6 compared with 12.1 ± 3.1 y; P = 0.005) and of a higher socioeconomic status according to the Hollingshead Index (32) (median: 3 compared with 2; P = 0.01); the 2 groups did not differ with regard to sex, race, any measure of body composition, or LOC status. The final sample consisted of 177 participants, 48% of whom were boys (Table 2). Fifty participants reported at least one episode of LOC eating in the month before assessment. Participants with LOC had significantly greater BMI and fat mass values and were more likely to be female than were those without LOC (Table 2; P ≤ 0.01). Thirty of those with LOC eating also met criteria for objective binge episodes in the past month; 2 participants met proposed DSM-IV-TR research criteria for BED (1). The number of episodes reported in the prior month ranged from 1 to 28 (median: 2 episodes/mo).

TABLE 2.

Demographics of the participants

| Loss of control (n = 50) | No loss of control (n = 127) | P value1 | |

| Age (y) | 13.3 ± 2.72 | 13.6 ± 2.8 | 0.378 |

| Female sex (%) | 64.0 | 41.7 | 0.007 |

| Race (%) | 0.461 | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 60.0 | 59.2 | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 28.0 | 31.7 | |

| Other | 12.0 | 9.1 | |

| Median socioeconomic status | 2 | 2 | 0.165 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.7 ± 9.9 | 23.4 ± 7.3 | 0.005 |

| BMI z score | 1.46 ± 1.97 | 0.80 ± 1.09 | <0.001 |

| Fat mass (kg) | 26.5 ± 12.3 | 16.2 ± 14.5 | 0.002 |

| Fat-free mass (kg) | 45.3 ± 16.9 | 43.3 ± 14.1 | 0.512 |

Independent t tests were used to analyze continuous dependent variables, and chi-square tests were used to analyze categorical dependent variables.

Mean ± SD (all such values).

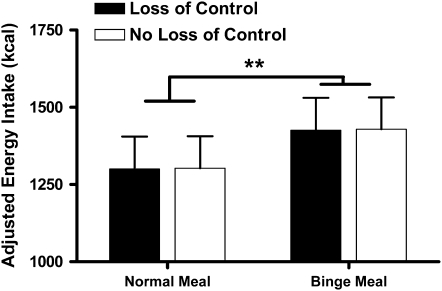

Energy intake

After all other variables in the model were controlled for, there was a main effect for meal type (P = 0.001). On average, participants consumed an adjusted 1301.2 ± 103.0 kcal at the normal meal compared with an adjusted 1428.9 ± 105.2 kcal at the binge meal (Figure 1). Race, sex, and fat-free mass (all P <0.01) and percentage fat mass (P = 0.05) each independently contributed to the model. Compared with white children, nonwhite children consumed more energy, boys ate more than girls, and there were positive relations between energy intake and both fat-free mass and fat mass. However, there was no main effect of age or LOC eating status, and the interaction of LOC by the type of meal instruction was not significant (Table 3). The findings remained nonsignificant when the number of LOC episodes was examined as a continuous variable (P = 0.63) or when youth were categorized by the presence of classic objective binge eating episodes (P = 0.50), as opposed to LOC eating. The association between LOC eating and energy intake was not significant (P = 0.64) in a model defining LOC eating episodes according to a self-report questionnaire (33) instead of by the EDE interview. Last, findings did not change when only those children who reported after the meals that they had experienced a sense of LOC while eating (61% of children who endorsed LOC eating during the EDE interview) were examined.

FIGURE 1.

Adjusted, back-transformed geometric mean (±SE) energy intakes for all participants at the 2 meals. **Energy intake was significantly greater at the binge meal than at the normal meal (linear mixed models with repeated measures, meal type). n = 177.

TABLE 3.

Results of a linear mixed model predicting energy intake (kcal)1

| Predictor variables | Adjusted estimates in model | SE | df | 95% CI | P value |

| Age | −0.0004 | 0.006 | 168.47 | (−0.012, 0.011) | 0.94 |

| Female sex | 0.124 | 0.022 | 169.21 | (0.081, 0.167) | <0.0001 |

| White race | 0.063 | 0.022 | 169.36 | (0.020, 0.105) | 0.004 |

| Fat mass (%) | 0.171 | 0.087 | 168.89 | (0.00001, 0.342) | 0.05 |

| log10 Fat-free mass (kg) | 0.590 | 0.111 | 168.76 | (0.370, 0.810) | <0.0001 |

| Meal type, binge | −0.040 | 0.020 | 172.73 | (−0.079, −0.002) | 0.001 |

| Loss of control | 0.0004 | 0.026 | 245.54 | (−0.051, 0.052) | 0.974 |

| Meal type × loss of control | 0.0006 | 0.023 | 172.65 | (−0.045, 0.046) | 0.978 |

n = 177. Energy intake (kcal) was log transformed. The reference groups for race, sex, meal type, and loss of control eating for race were the nonwhite category (0), the male category (0), the normal category (0), and the never category (0), respectively. Fat-free mass was log transformed.

Intake categorized according to macronutrient composition and food group

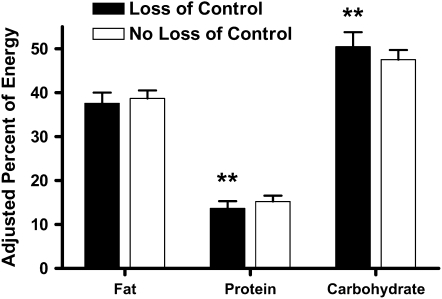

There was a main effect of LOC status in predicting the percentage of energy intake from protein. Regardless of meal type, participants with LOC consumed a smaller percentage of energy from protein than did those without LOC (P = 0.005; Figure 2). A main effect of LOC status was also found with regard to percentage intake from carbohydrate. Across both meals, participants with LOC ate a greater percentage of energy from carbohydrate than did those without LOC (P = 0.02; Figure 2). No other model variable significantly predicted the consumption of energy from protein or carbohydrate. There were no main or interactional effects of LOC or meal type for percentage of energy from fat consumed.

FIGURE 2.

Adjusted, back-transformed mean (±SE) macronutrient contents of the meals. **Significantly different from participants with no loss of control, P ≤ 0.01 (linear mixed models with repeated measures). n = 176.

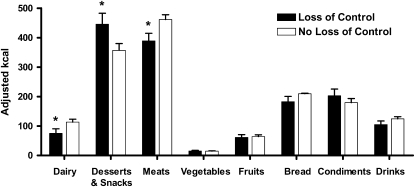

In an examination of intake classified by food group, compared with children without LOC, those with LOC consumed significantly less dairy products (P = 0.04) and meats (P = 0.02), but more snack and dessert-type foods (P = 0.05) across both meals (Figure 3). A comparison of intake at the binge meal with that at the normal meal among all participants showed that the youth ate more snack and dessert-type foods (422.4 ± 23.4 compared with 380.2 ± 23.5 kcal; P = 0.02), meats (444.5 ± 16.2 compared with 406.0 ± 16. 2 kcal; P = 0.001), fruit (67.6 ± 6.1 compared with 57.7 ± 6.1 kcal; P = 0.04), and drinks (120.7 ± 7.7 compared with 108.5 ± 7.7 kcal; P = 0.05).

FIGURE 3.

Mean (±SE) energy intakes from the different food types consumed at the 2 meals. *Significantly different from participants with no loss of control, P ≤ 0.05 (linear mixed models with repeated measures). Means were adjusted for sex, age, race, fat-free mass, and percentage fat mass. n = 172.

Time spent eating

After total energy intake was accounted for (P < 0.001), there was an effect of meal type (P = 0.02), such that participants, overall, took longer to complete their meal when asked to binge eat. Furthermore, there was a main effect of LOC eating status, such that youth with LOC took longer to indicate that they had finished their meals (29.8 ± 1.3 min) than did youth with no LOC eating (26.2 ± 0.8 min; P = 0.02). Fat-free mass also significantly contributed to the model (P < 0.001), such that fat-free mass was positively associated with duration of eating. Girls also ate more slowly than boys across both meals (P = 0.02). No other variables in the model predicted time spent eating.

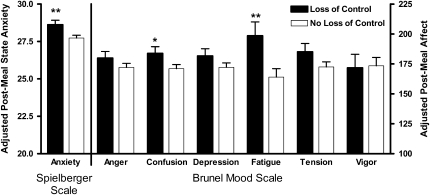

Changes in affect

After premeal state anxiety (P < 0.001) and all other variables in the model were controlled for, age (P = 0.05), LOC status (P = 0.01), and fat mass (P = 0.03) were positively associated with postmeal anxiety (Figure 4). Similarly, after the respective premeal state affect was accounted for (P < 0.001), LOC status was positively associated with postmeal state confusion (P = 0.05) and fatigue (P = 0.01) for both the normal and binge meals (Figure 4). There were no significant differences according to LOC status in postmeal state anger, depression, tension, or vigor based on LOC status; no significant effects of meal type; and no significant interactions between meal type and LOC status for any postmeal state affect measure.

FIGURE 4.

Mean (±SE) scores for postmeal state affect. *, **Significantly different from participants with no loss of control (linear mixed models): *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01. Means were adjusted for sex, age, race, fat-free mass, percentage fat mass, total energy intake, and respective pretest meal mood state. n = 176.

Post hoc analyses of energy intake by sex in overweight and obese youth

Because of the significant effect of sex observed in our model predicting energy intake, we conducted post hoc analyses to determine whether LOC status differentially affected girls compared with boys with regard to energy consumption. Furthermore, because prior laboratory studies of binge eating have generally included only overweight or obese participants (3, 13), we particularly studied only those youth with a BMI greater than or equal to the 85th percentile for age and sex (15) in these post hoc analyses. When all covariates were accounted for, a main effect of LOC status among girls at the binge meal, but not at the normal meal, was shown. Compared with overweight or obese girls without LOC (n = 23), overweight or obese girls with LOC (n = 22) consumed significantly more energy (adjusted mean ± SE) at the binge meal (no LOC: 1288.3 ± 105.4; LOC: 1548.8 ± 105.4 kcal; P = 0.025), but not at the normal meal (no LOC: 1174.9 ± 107.4; LOC: 1349.0 ± 107.9 kcal; P = 0.22). For overweight or obese boys with (n = 10) and without LOC (n = 35), there were no significant differences at either the binge meal (no LOC: 1737.8 ± 105.2; LOC: 1621.8 ± 110.2 kcal; P = 0.54) or the normal meal (mo LOC: 1592.2 ± 105.7; LOC: 1566.7 ± 110.9 kcal; P = 0.89).

DISCUSSION

We found that children and adolescents consumed more energy when instructed to binge eat than when instructed to eat normally. This finding suggests that participants were able to follow meal instructions in our paradigm. We also found that endorsement of loss of control eating was associated with the consumption of less energy from protein and more from carbohydrate, regardless of meal instructions. Post hoc analyses found among overweight girls, but not boys, that reported LOC eating was associated with greater energy intake at the binge meal than at the normal meal. At both meals, participants who reported LOC eating consumed more snack and dessert-type foods and less dairy products and meats. LOC eating was also predictive of a longer duration of eating and of greater postmeal anxiety, confusion, and fatigue.

Unexpectedly, there were no differences in energy intake on the basis of LOC status at the 2 laboratory meals. LOC was examined as a discrete construct in our analysis; however, no relation was identified with energy intake when LOC was examined on the basis of the number of LOC episodes as the independent variable. It is possible that, in contradistinction to adult binge episodes, the construct of reported LOC eating during youth is behaviorally manifested as a specific style of eating for which the number of episodes reported is not particularly illuminating. Participants reporting LOC eating were distinguished from those without LOC by the macronutrient composition and types of foods consumed at both meals. If the composition of these test meals reflect typical food intake, youth with LOC may habitually consume meals (normal and binge) composed of less protein and more snack and dessert-type, high-energy-density foods. Although the causal relation between a high carbohydrate intake and overweight is unclear, a lower protein consumption has been shown to be associated with lesser postmeal satiety, which may conceivably increase overall energy intake (34–36). Furthermore, high-calorie-snack and dessert-type foods may serve as “comfort” food that individuals with LOC may consume in large quantities at times outside of the laboratory setting in response to negative affect (37). Indeed, participants with LOC reported greater negative affect both before and after the meals. Interestingly, those with LOC consumed less dairy products and meats than did youth without LOC. In contrast with children without disordered eating behaviors, those with LOC opted to eat foods that were less representative of a typical lunch meal. Taken together, if the observed style of eating promotes overeating outside of the laboratory setting, our findings may explain why binge (9–11) and LOC (12) eating predict excess weight gain over time.

Notably, those with LOC did not consume more energy from fat at either meal than did those without LOC. This finding is in contrast with adult laboratory data (38) but is consistent with another study of self-reported food intakes of children that found no difference in the percentage of energy from fat consumed in episodes with and without LOC (39). Our findings regarding macronutrient consumption may differ from those in adults, due, in part, to the inclusion of different foods on our array compared with those used for buffets in the prior adult studies. Our array included several dessert-type foods high in carbohydrate but low in fat (eg, jellybeans) rather than just high-fat dessert options (eg, ice cream) as included in adult studies (13).

Compared with youth without LOC eating, those with LOC eating reported greater increases in state anxiety, confusion, and fatigue after both meals. These findings are consistent with the results from a multisite study of the self-reported emotional experiences among youth who describe experiencing LOC eating (14). These affective patterns are in concert with adult data insofar as binge episodes are reported to be followed by increases in negative mood (40). However, these findings differ from the adult literature in that youth with LOC showed an increase in negative affect after both normal and binge meals. Notably, after eating, youth with LOC did not report increases in other types of negative affect, namely, feelings of anger, depression, or tension. Compared with these affective states, it is possible that anxiety, confusion, and fatigue are constructs more closely aligned with the experience of “numbing” while eating, which has been reported by children and adolescents with LOC (14) and adults with binge eating (41).

In contrast with some findings from adult laboratory studies that included both a normal and a binge meal (13), our child and adolescent participants with LOC did not distinguish between meal type in terms of macronutrient intake or their affect before and after the meals. Unlike adult studies that included individuals with full-syndrome BED, the children in our sample did not report extensive disordered eating. Only 2 participants in our study met the research criteria for BED (1). Therefore, because our participants were not engaging in chronic and routine binge episodes, they may have not yet established a distinct set of behaviors that differentiated normal meals from binge meals. Furthermore, it is possible that LOC eating during youth represents a somewhat different construct than does binge eating in adults. For example, the presence of a large buffet of palatable foods when hungry may cause children with LOC to consume typical adult “binge” foods even if the children are instructed to eat normally.

In post hoc analyses of participants with a BMI greater than or equal to the 85th percentile, however, we found that girls, but not boys, with LOC consumed more energy at the binge meal than at the normal meal. Although this finding should be interpreted with caution because the 3-factor interaction of LOC by sex by weight status was not significant (P = 0.15), this pattern suggests that heavier girls with LOC may behave differently at a binge meal. The excessive energy intake associated with LOC eating may further clarify, at least for overweight girls, a mechanism whereby youth who report LOC eating are heavier (7, 8) and are at greater risk of excess weight gain over time (10–12). Consistent with the data from the one adult laboratory study that included obese men with BED (42), we found no difference between heavy boys with and without LOC eating in terms of energy intake at either meal. These findings differ from those of a previous study conducted in our laboratory using a similar feeding paradigm (3). Mirch et al (3) studied a younger sample, all of whom had elevated insulin and were seeking treatment of severe overweight, and the buffet was offered at an earlier time of day. Although our method for determining the presence of LOC differed from that of Mirch et al's (3) assessment of binge eating, our findings did not change when we used a self-report measure to determine the presence of LOC eating. It is possible that the differences in sample characteristics or the exact methods used may have contributed to the lack of consistency in findings across these 2 studies.

The strengths of this study included the large sample size, the use of both a normal meal and a binge meal, and the inclusion of boys and girls who were not seeking weight-loss treatment and had a broad range of ages and weights. Furthermore, we used a semistructured clinical interview to assess the presence of LOC eating. Limitations include that all participants were provided the same standardized breakfast before each test meal, regardless of body weight. It is possible that heavier youth required substantially more energy than what was provided for breakfast to have equal satiety, which thereby potentially masked some differences between groups with regard to LOC or meal type. However, we accounted for body composition in all analyses. A large buffet, although effectively used in prior studies (3, 13), may have affected the participants’ consumption. Preliminary data suggest that when greater amounts of food are presented, the amount of food eaten generally increases (43). Examination of the energy intake and macronutrient composition of meals that children with and without LOC consume in their natural environment over the course of an extended time period will be an important next research step. Finally, although consistent methods were used throughout data collection, they varied slightly from some of the directions given in adult studies in that the language for the meal instructions were more child-accessible and the time of the buffet meals was earlier. Further research should focus on the standardization of procedures across studies.

In conclusion, children and adolescents who report LOC eating may be at particular risk of consuming foods that promote overweight when they are offered large quantities of palatable foods. Future studies are needed to examine methods that may help children and adolescents with LOC eating modify their choices and prevent excessive weight gain.

Acknowledgments

We thank the families who participated in these studies and the staff of the metabolic kitchen at the NIH Clinical Center.

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—MT-K, JRM, SZY, and JAY: primarily responsible for developing the study design and conceived the hypothesis for this study; MT-K and JAY: supervised the data collection; MT-K, LBS, and JAY: conducted the data analysis. and MK, NAS, and CS: contributed to the data collection and provided critical input on the data analyses and on different versions of the manuscript. All authors participated in the interpretation of the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. The funding organization played no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation or review of the manuscript. None of the authors had any conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders DSM-IV-TR. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanofsky-Kraff M. Binge eating among children and adolescents. Jelalian E, Steele R. Handbook of child and adolescent obesity New York, NY: Springer, 2008:41–57 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mirch MC, McDuffie JR, Yanovski SZ, et al. Effects of binge eating on satiation, satiety, and energy intake of overweight children. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;84:732–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Decaluwe V, Braet C. Prevalence of binge-eating disorder in obese children and adolescents seeking weight-loss treatment. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2003;27:404–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Faden D, Yanovski SZ, Wilfley DE, Yanovski JA. The perceived onset of dieting and loss of control eating behaviors in overweight children. Int J Eat Disord 2005;38:112–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glasofer DR, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Eddy KT, et al. Binge eating in overweight treatment-seeking adolescents. J Pediatr Psychol 2007;32:95–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morgan CM, Yanovski S, Nguyen T, et al. Loss of control over eating, adiposity, and psychopathology in overweight children. Int J Eat Disord 2002;31:430–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Yanovski SZ, Wilfley DE, Marmarosh C, Morgan CM, Yanovski JA. Eating disordered behaviors, body fat, and psychopathology in overweight and normal weight children. J Consult Clin Psychol 2004;72:53–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Field AE, Austin SB, Taylor CB, et al. Relation between dieting and weight change among preadolescents and adolescents. Pediatrics 2003;112:900–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stice E, Cameron RP, Killen JD, Hayward C, Taylor CB. Naturalistic weight-reduction efforts prospectively predict growth in relative weight and onset of obesity among female adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol 1999;67:967–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Cohen ML, Yanovski SZ, et al. A prospective study of psychological predictors of body fat gain among children at high risk for adult obesity. Pediatrics 2006;117:1203–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Yanovski SZ, Schvey NA, Olsen CH, Gustafson J, Yanovski JA. A prospective study of loss of control (LOC) eating for body weight gain in children at high-risk for adult obesity. Int J Eat Disord 2009;42:26–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walsh BT, Boudreau G. Laboratory studies of binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord 2003;34(suppl):S30–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Goossens L, Eddy KT, et al. A multisite investigation of binge eating behaviors in children and adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol 2007;75:901–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, et al. CDC growth charts for the United States: methods and development. Vital Health Stat 11 2000;2002:1–190 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Russell DL, Keil MF, Bonat SH, et al. The relation between skeletal maturation and adiposity in African American and Caucasian children. J Pediatr 2001;139:844–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, et al. CDC growth charts: United States. Adv Data 2000;314:1–27 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dempster P, Aitkens S. A new air displacement method for the determination of human body composition. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1995;27:1692–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Arch Dis Child 1969;44:291–303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in the pattern of pubertal changes in boys. Arch Dis Child 1970;45:13–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanner JM. Growth and maturation during adolescence. Nutr Rev 1981;39:43–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fairburn C, Cooper Z. The Eating Disorder Examination. Fairburn CF, Wilson GT. Binge eating, nature, assessment and treatment. 12th ed New York, NY: Guilford, 1993:317–60 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bryant-Waugh RJ, Cooper PJ, Taylor CL, Lask BD. The use of the eating disorder examination with children: a pilot study. Int J Eat Disord 1996;19:391–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hess MA. Portion photos of popular foods. Madison, WI: Center for Nutrition Education, University of Wisconsin-Stout, 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rizvi SL, Peterson CB, Crow SJ, Agras WS. Test-retest reliability of the eating disorder examination. Int J Eat Disord 2000;28:311–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Christie D, Watkins B, Lask B. Assessment. Lask B, Bryant-Waugh RJ. Anorexia nervosa and related eating disorders in childhood and adolescence. 2nd ed East Essex, United Kingdom: Psychology Press, 2000:105–25 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Block G, Norris JC, Mandel RM, DiSogra C. Sources of energy and six nutrients in diets of low-income Hispanic-American women and their children: quantitative data from HHANES, 1982-1984. J Am Diet Assoc 1995;95:195–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hetherington MRB. Methods of investigating human behavior. In: Toates FRN, ed Feeding and drinking. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier Science Publishers BV, 1987:77–109 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spielberger C, Lushene G, Vagg P, Jacobs G. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologist Press, 1983 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Terry PC, Lane AM, Lane HJ, Keohane L. Development and validation of a mood measure for adolescents. J Sports Sci 1999;17:861–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.SPSS SPSS 14.0. Chicago, IL: SPSS Inc, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hollingshead A. Four factor index of social status. New Haven, CT: Yale University, 1975 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson WG, Grieve FG, Adams CD, Sandy J. Measuring binge eating in adolescents: adolescent and parent versions of the questionnaire of eating and weight patterns. Int J Eat Disord 1999;26:301–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paddon-Jones D, Westman E, Mattes RD, Wolfe RR, Astrup A, Westerterp-Plantenga M. Protein, weight management, and satiety. Am J Clin Nutr 2008;87:1558S–61S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schoeller DA, Buchholz AC. Energetics of obesity and weight control: does diet composition matter? J Am Diet Assoc 2005;105:S24–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Westerterp-Plantenga MS. The significance of protein in food intake and body weight regulation. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2003;6:635–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gibson EL. Emotional influences on food choice: sensory, physiological and psychological pathways. Physiol Behav 2006;89:53–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yanovski SZ, Leet M, Yanovski JA, et al. Food selection and intake of obese women with binge-eating disorder. Am J Clin Nutr 1992;56:975–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Theim KR, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Salaita CG, et al. Children's descriptions of the foods consumed during loss of control eating episodes. Eat Behav 2007;8:258–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stein RI, Kenardy J, Wiseman CV, Dounchis JZ, Arnow BA, Wilfley DE. What's driving the binge in binge eating disorder? A prospective examination of precursors and consequences. Int J Eat Disord 2007;40:195–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pinaquy S, Chabrol H, Simon C, Louvet JP, Barbe P. Emotional eating, alexithymia, and binge-eating disorder in obese women. Obes Res 2003;11:195–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Geliebter A, Hassid G, Hashim SA. Test meal intake in obese binge eaters in relation to mood and gender. Int J Eat Disord 2001;29:488–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gosnell BA, Mitchell JE, Lancaster KL, Burgard MA, Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD. Food presentation and energy intake in a feeding laboratory study of subjects with binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord 2001;30:441–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]