Abstract

DJ-1 is a dimeric protein of unknown function in vivo. A mutation in the human DJ-1 gene causing substitution of proline for leucine at residue 166 (L166P) has been linked to early-onset Parkinson’s disease. Lack of structural stability has precluded experimental determination of atomic-resolution structures of the L166P DJ-1 polymorph. We have performed multiple molecular dynamics (MD) simulations (∼1/3 μs) of the wild-type and L166P DJ-1 polymorph at physiological temperature to predict specific structural effects of the L166P substitution. L166P disrupted helices α1, α5, α6 and α8 with α8 undergoing particularly severe disruption. Secondary structural elements critical for protein stability and dimerization were significantly disrupted across the entire dimer interface, as were extended hydrophobic surfaces involved in dimer formation. Relative to wild-type DJ-1, L166P DJ-1 populated a broader ensemble of structures, many of which corresponded to distorted conformations. In a L166P dimer model the substitution significantly destabilized the dimer interface, interrupting >100 intermolecular contacts that are important for dimer formation. The L166P substitution also led to major perturbations in the region of a highly conserved cysteine residue (Cys-106) that participates in dimerization and that is critical for a proposed chaperone function of DJ-1. Cys-106 is located ∼16 Å from the substitution site, demonstrating that structural disruptions propagate throughout the whole protein. Furthermore, L166P DJ-1 showed a significant increase in hydrophobic surface area relative to wild-type protein, possibly explaining the tendency of the mutant protein to aggregate. These simulations provide details about specific structural disturbances throughout L166P DJ-1 that previous studies have not revealed.

Thirteen genetic loci, PARK1-PARK13, have been proposed to play a role in rare forms of Parkinson’s disease (PD), including autosomal dominant and autosomal recessive PD (1). Genes of PARK1, PARK2 and PARK 5 encode α-synuclein (SNC A) (2), the E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase parkin (Parkin) (3, 4) and ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCHL1) (5), respectively. PARK6, PARK8 and PARK9 genes encode PTEN-induced kinase 1 (PINK1) (6), leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) (7) and a lysosomal type 5 P-type ATPase (ATP13A2) (8). Mutations in these genes have been identified in familial forms of PD (9).

Mutations of DJ-1 in the PARK7 locus are linked to an autosomal recessive form of familial early-onset PD (10). DJ-1 encodes a protein that is ubiquitously expressed in body tissues and brain areas, including those that are affected in PD (10). The function of the DJ-1 protein in vivo remains controversial and several functions have been proposed. The DJ-1 gene was first identified as an oncogene with transforming activity (11) and DJ-1 has been observed as a circulating tumor antigen in breast cancer (12). It has been demonstrated that DJ-1 acts as a regulatory subunit of a ∼400-kDa RNA-binding protein complex (13), as a transcription factor regulating expression of p53, androgen receptor and PTEN (14-18), as a scavenger of mitochondrial H2O2 (19) and may function as a protease (20). Moreover, DJ-1 has been proposed to have a chaperone function both by structural analogy to Hsp31 (21, 22) and by observations that it prevents aggregation of citrate synthase and luciferase in vitro (21). The ability of DJ-1 to inhibit α-synuclein aggregation (23, 24) and the presence of hydrophobic patches on the protein surface that contain chemical and geometrical features suitable for interaction with non-native proteins (21) further support the proposed chaperone activity of DJ-1.

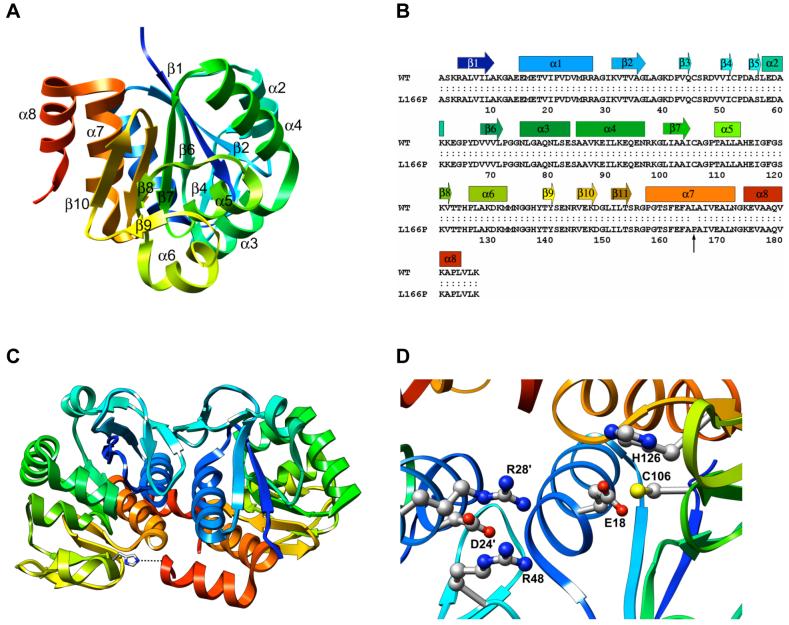

DJ-1 is an evolutionarily conserved, ∼20-kDa, 189-residue protein containing eight α-helices (α1-α8) and eleven β-strands (β1-β11) (Figure 1A-B). Crystal structures reveal that it has a flavodoxin-like Rossmann fold and adopts a helix-strand-helix sandwich structure (25-27). A parallel β-sheet forms a central core, flanked by α-helices other than α8. α8 occurs at the C-terminus of the protein and projects away from the remainder of the structure, forming mainly hydrophobic interactions with α1 and α7. α7 and α8 pack particularly tightly. Wild-type (wt) DJ-1 occurs as a homodimer and the dimer interface is formed mainly by α1, α7, α8 and β4, with the α1 helices of the two subunits running parallel to one another and coming into close contact (Figure 1C). These α-helices interact mainly through hydrophobic contacts, but a hydrogen bond and ionic interactions also participate in their interaction. The β3-β4 hairpins of the subunits are situated at one end of the dimer interface, forming a four-stranded anti-parallel α-sheet. The other end of the interface features the β11-α7 loop interacting with residues near the C-terminus of α8 in the opposite subunit. This interaction is assisted by a hydrogen bond between the Nε atom of His-126 and the backbone carbonyl oxygen atom of Pro-184 in the opposite subunit. Met-17 and Phe-162 form the core of hydrophobic interactions and are critical for dimer formation (25). Dimer formation is also mediated by interaction of Met-17 with Asp-24′ and Arg-28′ (primed residues indicate residues of opposite subunit).

Figure 1.

DJ-1 structure. (A) Ribbon diagram of human DJ-1 (1PDV, ref. 26). The structure is colored from blue (N-terminus) to red (C-terminus). (B) Sequence of human wt DJ-1 and L166P polymorph. α-helices and α-strands are indicated by bars and arrows, respectively, and are colored to match the ribbon representation of DJ-1. The site of the L166P substitution is indicated by a vertical arrow. (C) Ribbon diagram of human DJ-1 dimer (1UCF, ref. 25). A hydrogen bond critical for dimer formation is formed by His-126 and the backbone carbonyl oxygen atom of Pro-184 of the opposite subunit (represented as a dotted line at the bottom of the figure). (D) The side chain of highly conserved Cys-106 is located near the side chains of His-126 and buried Glu-18. Residues Asp-24′ and Arg-28′ from the opposite subunit contribute to stabilizing interactions across the subunit-subunit interface in the dimer.

DJ-1 is a member of the DJ-1/ThiJ/PfpI superfamily of proteins, which are conserved in a wide variety of organisms (26). DJ-1 is most structurally similar to several proteins that belong to the Class I glutamine amidotransferase-like (GAT) superfamily having ThiJ domains (28). Like the GAT superfamily members, human DJ-1 has a highly conserved cysteine at residue position 106 that is situated in a distinctive strand-turn-helix motif and in a major surface depression. The side chains of Glu-18 and His-126 are both located in close proximity to the Cys-106 side chain (Figure 1D). Glu-18, highly conserved among all of the DJ-1/ThiJ/PfpI proteins and present in Hsp31 (26), has its side chain buried in the structure, suggesting that it plays a significant role in the functions of these proteins. The oxidation state of the Cys-106 side chain appears to have an important role in the chaperone activity of DJ-1. Native (unoxidized) DJ-1 does not prevent fibrillation of α-synuclein. Oxidative conditions induce formation of the sulfinic acid of Cys-106, the most sensitive cysteine residue to oxidative stress (19, 29), by addition of two oxygen atoms to its side chain, making DJ-1 effective in preventing α-synuclein fibrillation (24). Further oxidation, however, causes partial loss of secondary structure and loss of inhibition of α-synuclein fibrillation (24). The particular sensitivity of Cys-106 to oxidative stress suggests that the chaperone ability of DJ-1 is regulated by the oxidation state of Cys-106 (29).

One of the most extensively investigated and deleterious DJ-1 polymorphs is L166P, which results from a homozygous missense mutation in DJ-1 and is associated with early-onset PD. Studies using circular dichroism (CD) and NMR have shown that the L166P substitution, occurring near the middle of α7, causes DJ-1 to lose α-helical content and leads to global destabilization of the protein structure (30, 31). The structural perturbation of DJ-1 induced by the L166P substitution causes the protein to be ubiquitinated and destroyed by the 26S proteasome (20, 32), significantly reducing the half-life of the protein in vivo (30). The L166P polymorph of DJ-1 is incapable of forming a stable homodimer with itself and a heterodimer with wt DJ-1 (20). Since helices α7 and α8 are known to help mediate dimerization (27), the failure to form a dimer in solution is consistent with the observation that L166P perturbs the structure of one or both of these helices. L166P DJ-1 forms high molecular-weight complexes containing DJ-1 oligomers or aggregates with other proteins (10, 20, 33, 34). Furthermore, L166P has been shown to abrogate DJ-1 chaperone activity as a consequence of defective dimerization and reduced stability (23).

Despite the experimental characterization of many functional effects of the L166P substitution in DJ-1, atomic-resolution structures of the L166P polymorph and a detailed molecular framework for its destabilization and loss of function are lacking. Comprehensive details at atomic resolution about the structural perturbations induced by the L166P substitution thus remain elusive. For this reason we have performed multiple MD simulations of both wt and L166P DJ-1 monomers and dimers at 310 K for a total simulation time of ∼1/3 μs. The simulations of L166P DJ-1 monomers showed several significant structural disruptions throughout the protein that were not observed in control simulations of the wt monomer, including a drastic loss of α-helicity in the C-terminal portion of α8 and α6. The substitution also induced severe distortion of structural elements across the entire dimer interface, including the region around the side chain of the highly conserved Cys-106 located ∼16 Å from residue 166 and the N-terminal region of α1, a key mediator of dimer formation. We have also performed multiple MD simulations of the wt homodimer and of a homodimer model containing the L166P substitution in both subunits. L166P DJ-1 is reported to exist only as a monomer in equilibrium with aggregated species in solution. Consequently, introducing the L166P substitution in both subunits of the WT dimer would be expected to destabilize the dimer, and simulations can elucidate which structural elements in the protein are most susceptible to destabilization. Simulations of the mutant homodimer model are consistent with this destabilization, showing great instability at the interface between the two subunits. The global structure of the subunits becomes more diffuse, losing a significant amount of intramolecular packing. Structural disruptions are associated with a large increase in the total hydrophobic surface area exposed to solvent and enhanced exposure of certain lysine residues to solvent, both of which may lead to the aggregation of L166P observed experimentally. Together, these results indicate that the structural effects of the L166P substitution in DJ-1 are not confined to the vicinity of the substitution, but propagate rapidly throughout the protein. These structural disruptions are consistent with the inability to observe L166P DJ-1 dimer formation and function in vitro and in vivo.

METHODS

Molecular Dynamics Simulations and Analysis

The starting model for wt DJ-1 monomer was the 1.80 Å resolution crystal structure of human DJ-1 at pH 8.0 [PDB entry 1PDV (26)]. Although wt DJ-1 does not exist as a stable monomer in solution or in crystals, the asymmetric unit of the 1PDV structure contains only a single chain and the dimer is generated by a crystallographic two-fold symmetry operator. The biological molecule reported in the PDB is dimeric and thus the structure of the monomer in the asymmetric unit does not differ from the structure of each subunit in the dimer. All water molecules were removed from the crystal structure. The L166P polymorph was created by replacing Leu-166 by a Pro residue and minimizing the torsional, electrostatic and van der Waals interactions of the resulting mutant structure in vacuo using the ENCAD simulation package (35). The starting model for the wt DJ-1 dimer was the 1.95 Å resolution crystal structure of human DJ-1 at pH 7.5 [PDB entry 1UCF (25)]. The asymmetric unit of 1UCF contains the full dimeric structure. The L166P dimer polymorph was prepared using the same method as for the monomer, and the amino acid substitution was introduced in both subunits of the dimer structure. In the monomer simulations all His residues were protonated at ND1. In the dimer simulations His-138 was protonated at ND1 in both subunits and all other His residues in the protein structure were protonated at Nε2. Tautomer assignments for His were based on investigation of likely hydrogen bonds in the crystal structure. No cysteine disulfide bonds were present in the crystal structures or simulations. All simulations were conducted at neutral pH.

Starting protein structures were minimized in vacuo for 1000 steps of steepest descent minimization. Atomic partial charges and the potential energy function were taken from Levitt et al (36). The minimized structures were then solvated in a rectangular box of flexible three-center (F3C) waters (37) with walls located ≥10Å from any protein atom. The solvent density of the box was preequilibrated to 0.993 g/mL, the experimental water density for 310 K and 1 atm pressure (38). The solvent was minimized for 1000 steps. This minimization was followed by 1 ps of dynamics of the solvent only and then by an additional 500 steps of solvent minimization. Solvent minimization was followed by 500 steps of minimization of the entire system. After completion of this solvation process, the whole system was heated to 310 K.

MD simulations were performed at 310 K in the microcanonical (NVE) ensemble using the in lucem molecular mechanics (ilmm) program (39). Multiple (n = 3) ∼25 ns simulations for both the wt and L166P monomer were performed and multiple (n = 3) >25 ns simulations were performed for the wt and L166P dimers. For both the wt and the L166P dimer structures, one of the three simulations was 50 ns in length. Protocols and the potential energy function have been described previously (36, 40). The simulations included all hydrogen atoms, which were added by ilmm to the crystal structures. A force-shifted nonbonded cutoff of 10 Å was used and the nonbonded interaction pair list was updated every three steps. A time step of 2 fs was applied in all simulations and structures were saved every 1 ps for analysis.

Analysis of MD simulations was performed using ilmm. Cα root-mean-square deviations (Cα-RMSDs), Cα root-mean-square fluctuations about the mean (Cα-RMSFs), contact distances, solvent accessible surface areas (SASA), and secondary structure assignments were calculated. An atomic contact was defined as occurring when an interresidue C-C atom distance was ≤5.4 Å or a heavy-atom (C, O, N, S) distance was ≤4.6 Å in two nonadjacent residues. Residues were considered to be in contact if any interresidue pair of atoms formed a contact. A contact was counted as a hydrogen bond if the donor-acceptor angle was >135° and the hydrogen-acceptor distance was ≤2.6 Å. SASAs were calculated using the NACCESS algorithm (41) and secondary structure assignments were performed using the DSSP algorithm (42). Protein images were produced using Chimera (43).

RESULTS

Effects of L166P substitution on DJ-1 monomer global structure

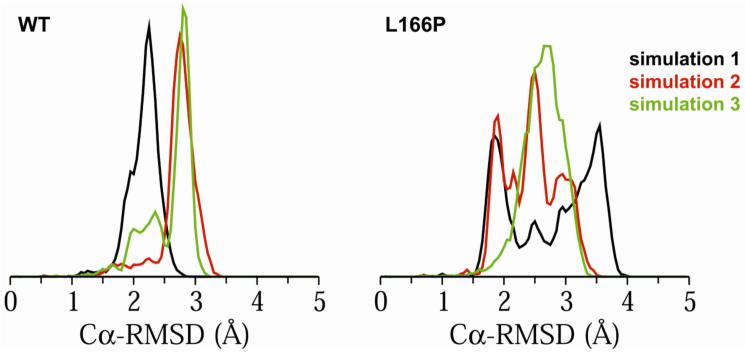

Simulations of wt and L166P monomeric DJ-1 protein with lengths of ∼25 ns were conducted at 310 K in triplicate. Although wt DJ-1 exists only as a dimer, simulations of wt monomer were performed in order to serve as a control for simulations of L166P monomer. The root-mean-square deviations of Cα atoms (Cα-RMSD) from their positions in the starting structure for each separate simulation were calculated as a measure of the overall stability of wt and L166P structures. The wt structure is stable throughout all three trajectories and has an average Cα-RMSD of 2.7 ± 0.3 Å for the last 5 ns of each simulation. The Cα-RMSD of the L166P protein is 3.1 ± 0.5 Å. Figure 2 shows that the Cα-RMSD values for the wt simulations remain relatively tightly clustered between 2 Å and 3 Å. The L166P simulations, in contrast, show a broader distribution of conformations and a wider Cα-RMSD distribution. In L166P simulation 1, a significant proportion (∼20%) of simulated structures have Cα-RMSDs >3.5 Å, while ∼50% of structures’ Cα-RMSDs are >3.0 Å. Cumulatively, ∼24% of all structures from the three L166P simulations have Cα-RMSDs >3.0 Å. None of the structures from the three wt simulations have Cα-RMSDs >3.5 Å and only ∼1% of structures have Cα-RMSDs >3.0 Å.

Figure 2.

Distributions of Cα-RMS deviations (in Å) during the last 10 ns of DJ-1 wt and L166P monomer simulations. Simulations 1, 2 and 3 are indicated by black, red and green, respectively.

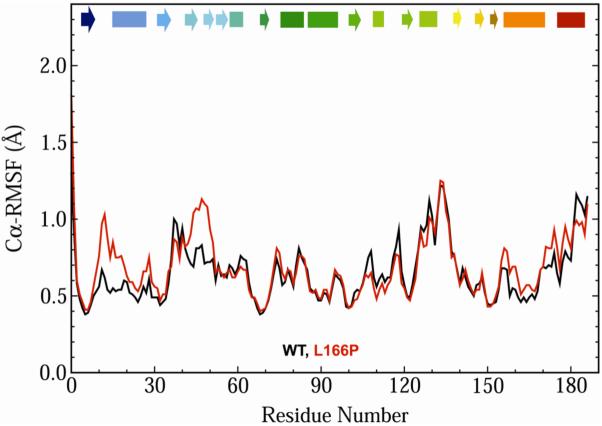

The average root-mean-square fluctuations of wt and L166P protein Cα atom coordinates (Cα-RMSF) about their average simulation structures are nearly equal for residues 1-10, 30-41, 50-105, 116-126, 131-155, 167-170, 181-182 and 186-187 (Figure 3). The L166P Cα-RMSF is greater than that of wt simulations for residues 11-29, 42-49, 156-166 and 171-180, while the wt Cα-RMSF exceeds that of L166P for residues 106-115, 127-130 and 183-185. The most pronounced Cα-RMSF differences occur for residues 11-18, which correspond to the turn between β1 and α1 and the N-terminal portion of α1 itself, and for residues 43-50, which correspond to β3, β4 and their connecting turn. In these regions the L166P C α-RMSF is ∼1.3 times greater than that of wt.

Figure 3.

Average Cα-RMS fluctuations (in Å) per residue for the three wt (black) and three L166P (red) simulations of DJ-1 monomer. C α-RMSFs were calculated relative to the average structure over the last 10 ns of all three wt and all three L166P simulations. Secondary structural elements are indicated at the top of the plot and colored to match the ribbon representations of DJ-1 in Figure 1. Key: box, α-helix; arrow, β-strand.

The L166P substitution is also associated with an overall expansion of the DJ-1 structure. The average total SASA values for the wt and L166P simulations are 9480 Å2 and 9650 Å2, respectively.

Effects of L166P substitution on DJ-1 monomer α-helical structures

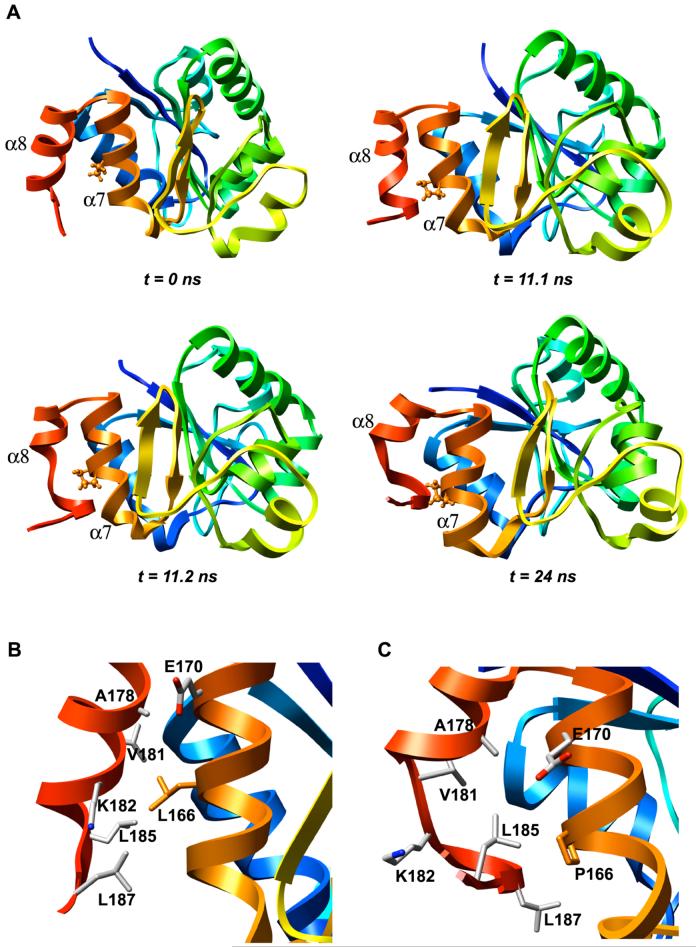

Our MD simulations show that the L166P substitution causes a significant loss of α-helical content in α8. The structure of α8 is stable for the first 8-15 ns of the simulations of mutant DJ-1 but the C-terminal end of the helix subsequently loses its helicity (Figure 4A). In simulation 1 residues 181-184 lose their helicity permanently after 11.2 ns. The same residues lose their helicity after ∼8 ns in simulation 2 and the α-helix is briefly reformed and quickly lost intermittently throughout the remainder of the trajectory. Simulation 3 shows occasional, brief losses of α-helical structure for residues 181-184.

Figure 4.

L166P DJ-1 simulations show significant loss of helical content in α8. (A) Time sequence of loss of helical structure of L166P DJ-1 residues 181-184 at C-terminal end of helix α8. Pro-166 is displayed in ball-and-stick format. Structures shown are taken from the indicated time points of L166P simulation 1. (B) In the wt DJ-1 simulations Leu-166 retains 67 of the 69 interresidue atomic contacts with helices α7 and α8 that are observed in the wt DJ-1 monomer crystal structure. The side chains of the residues contacted by Leu-166 are displayed in stick format and colored by atom type. The Leu-166 side chain is shown in orange. (C) The L166P DJ-1 simulations show an average of only 52 interresidue atomic contacts between Pro-166 and α7 and α8. The side chains of the residues that are contacted by Leu-166 in the wt simulations are displayed in stick format and colored by atom type. The Pro-166 residue is shown in orange.

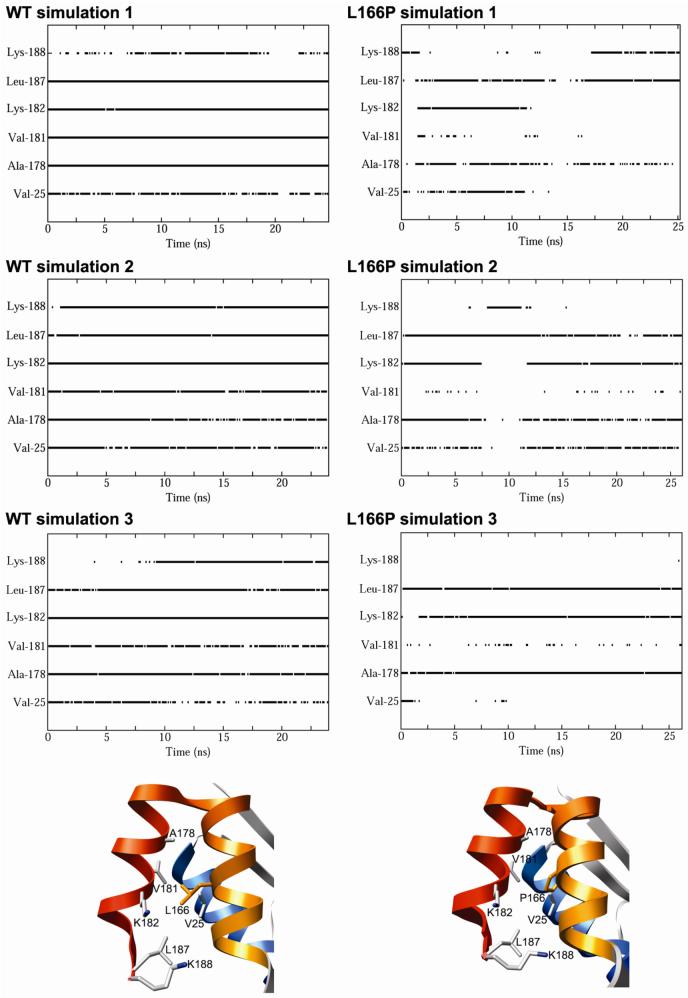

The destabilization of α8 in L166P simulation 1 is associated with the loss of ∼17 atomic contacts between Pro-166 and residues in close spatial proximity. In the starting structure of wt DJ-1, Leu-166 makes a total of 69 contacts with residues in α7 and α8, including Ile-168, Val-169, Glu-170, Ala-178, Val-181, Lys-182, Leu-185 and Leu-187 (Figure 4B). Structures from the simulations of wt DJ-1 have an average of 67 contacts involving Leu-166, showing good conservation of those contacts observed in the starting structure. In contrast, the L166P simulation structures have an average of only 52 contacts formed by Pro-166 (Figure 4C). All four of the contacts between Val-181 and Pro-166 and 11 of the 14 contacts between Lys-182 and Pro-166 in the starting structure are lost in the L166P simulations. This ∼25% reduction in the number of interresidue atomic contacts that Pro-166 forms relative to the Leu-166 structure appears to have a critical role in the destabilization of the C-terminal end of α8. In addition to the loss of contacts with Val-181 and Lys-182, Pro-166 loses all interresidue atomic contacts with Val-25 (located in α1) and Ala-178 for significant portions of the L166P trajectories, whereas these contacts are maintained for most of the wt trajectories (Figure 5). Contacts are also formed between Leu-166 and Lys-188 for the majority of the wt trajectories but are seldom found for the Pro-166 residue in the L166P simulations. Furthermore, although the total number of interresidue atomic contacts that Pro-166 forms with Phe-162, Glu-163, Phe-164, Ile-168, Val-169 and Glu-170 decreases relative to the starting structure, at least one atomic contact for each of these residues is maintained for the duration of the L166P simulations.

Figure 5.

(A) Contacts formed by residue 166 as a function of time for DJ-1 wt (left) and L166P (right) monomer simulations. The residues with which residue 166 forms atomic contacts are specified on the vertical axis. A solid line indicates that at least one intermolecular atomic contact occurs between the specific residue on the vertical axis and residue 166 at the given time. Gaps in lines signify that no intermolecular contacts with the specific residue occur at the given time. (B) Contacts with Leu-166 and (C) Pro-166 monitored in part A. Relevant amino acid side chains are represented by sticks. The structures depicted in (A) and (B) are the starting structures of the wt and L166P simulations, respectively.

Despite the loss of the helical content of residues 181-184, the Cα-RMS fluctuations of these residues are not significantly greater than those in the wt 310 K simulation (Figure 3). The fluctuations per residue follow the same trend for the whole wt and L166P DJ-1 structures. It is interesting to note that even in the wt DJ-1 simulations the residues corresponding to α8 exhibit larger Ca-RMSF values (∼1 Å) than those in the rest of the protein, with the exception of residues 15-21, 36-39 and 125-135. It is possible that the pre-existing relative instability of α8 facilitates the disruption of the helix at its C-terminal end.

In L166P simulation 1 the total SASA of Pro-166 remains ∼15 Å2 for the first ∼11.2 ns with the exception of two brief spikes of <300 ps duration at 1 ns and 5.4 ns. However, the Pro-166 SASA increases rapidly to ∼70 Å2 at approximately the same time that α8 loses its helical content (∼11.2 ns) and remains high for the remainder of the trajectory (data not shown).

The L166P substitution in the DJ-1 monomer leads to a structural distortion of α7 itself. The average distance between the Cα atoms of Phe-162 and residue 166 for the three L166P simulations is 7.1 ± 0.2 Å, while for the three wt simulations this distance is 6.2 ± 0.1 Å. This increase corresponds to a stretching of the central portion of the α7 backbone. However, the amino acid substitution does not perturb the main chain structure of the C-terminal end of α7.

Helical structure is also lost elsewhere in the L166P DJ-1 structure. The N-terminal end of α1, comprising residues 15-21, loses its α-helicity in all three L166P simulations and abruptly moves away from the central β-sheet (Figure 6A). The α1 disruption precedes the disruption of α8 by ∼3 ns. Since residue 166 forms no contacts with the N-terminal end of α1, the helical loss in the latter appears to result from breaking of contacts with the N-terminal end of α7, which is itself distorted by the substitution. The N-terminal end of α1 reforms only occasionally and for brief intervals after its initial disruption.

Figure 6.

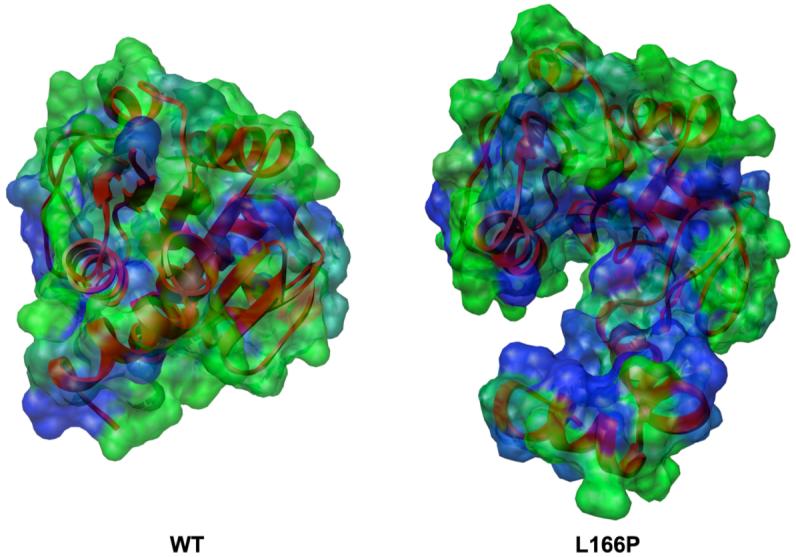

Structural distortion of region around conserved Cys-106 in L166P DJ-1 and disruption of dimer interface. (A) The N-terminal end of α1 loses its helicity in the L166P simulation and the helix moves away from the central β-sheet. (B) In the wt crystal structure the side chain of Glu-18 is buried in the protein structure. The distance between atom Sγ of the Cys-106 side chain and the Cα atom of the Glu-18 side chain is 3.9 Å. In the L166P simulations the side chain of Glu-18 loses its buried position and swings outward into solution. At the end of L166P simulation 1 (24 ns), the distance between atom Sγ of the Cys-106 side chain and the Cδ atom of the Glu-18 side chain is 15.2 Å. (C) In L166P simulations 2 and 3, the displaced Glu-18 side chain is stabilized by forming hydrogen bonds (indicated by black lines) with the side chain of Ser-161 and with backbone amide hydrogen atoms of Gly-159, Thr-160 and Ser-161. The side chain of Thr-160 is not shown. (D) Surface representation of DJ-1 wt and L166P monomers colored according to hydrophobicity. Each subunit of the DJ-1 dimer contains a large hydrophobic surface (extended blue patch). In L166P simulations this surface is divided in two by repositioning of the hydrophilic Asp-24 and Arg-27 residues. Colors range continuously from green (most hydrophilic) to blue (most hydrophobic). Hydrophobicity values were calculated by Chimera using the algorithm of Kyte and Doolittle (47).

Structural changes affect even α-helices that are distant from the α1-α7-α8 three-helix bundle. In L166P simulation 1 the N-terminal end of α6 (residues 126-130) loses its helical content at 11.2 ns, the time at which the disruption of α8 occurs. This timing suggests the presence of a mechanism by which the effect of the L166P substitution is able to be rapidly transferred to α6, which is located 19-23 Å away from the substitution site. The L166P substitution initially perturbs the β11-loop-α7 motif, which begins to lose its packing with the C-terminal end of the loop joining α5 and α6 at ∼10 ns. At 10.8 ns, presumably as a result of this lost packing, the backbone of Pro-127 at the N-terminus of α6 undergoes an abrupt transition from a right-handed α-helix conformation to a permanent β-sheet conformation. In L166P simulations 2 and 3 the N-terminal end of α6 alternates between a α-helix and a 3/10 helix and occasionally exists as a random coil for brief time intervals. Similarly to α8, the Cα-RMSF of α6 in the wt exceeds that of the rest of the protein, possibly predisposing it to disruption in the L166P polymorph.

Disruption of DJ-1 monomer structure near highly conserved Cys-106 residue induced by L166P

The Cys-106 and Glu-18 residues of DJ-1 are highly conserved among members of the GAT and DJ-1/ThiJ/PfpI superfamilies. Cys-106 adopts a strained backbone conformation (ϕ = 77°, ψ = -101°) in DJ-1 and in every other protein of known structure in the DJ-1/ThiJ/PfpI superfamily, which may help to confer its unusual reactivity (27). Thus, although the function of DJ-1 in vivo is unknown, it is likely that Cys-106 and Glu-18 play essential roles in its function. It has been proposed, for example, that Cys-106 acts as a sensor for oxidative stress in DJ-1 that enables the protein to function as a chaperone.

The close proximity of the side chains of Cys-106 and Glu-18 is important for the dimerization of DJ-1. In the wt protein a hydrogen bond is formed between the Sγ atom of the Cys-106 side chain and the carboxylate group of the Glu-18 side chain. This hydrogen bond stabilizes the N-terminus of α1, which is a critical mediator of dimer formation and accounts for a large number of interactions across the dimer interface. Destabilization of α1 could thus compromise the strength of the DJ-1 dimer.

The strained backbone conformation of Cys-106 is relieved in all L166P simulations, adopting a left-handed α-helix conformation (ϕ = 56°, ψ = 72°). L166P also causes a major structural distortion of the region around Cys-106 despite the fact that Cys-106 is located ∼16 Å away from residue 166. As a consequence of the loss of helicity in the N-terminal portion of α1, the Glu-18 side chain pulls far away from the strand-turn-helix motif in which Cys-106 is situated (Figure 6B). The distance between the Cδ atom of the Glu-18 side chain and the Sγ atom of the Cys-106 side chain increases from 3.9 Å in the crystal structure to an average of 11 Å over the last 10 ns of each of the three L166P simulations. In L166P simulation 1, this distance increases to 17 Å within 8 ns. The Glu-18 side chain swings out into solution and its SASA increases from zero in the starting structure to an average of ∼80 Å2 in the three L166P simulations. In two of the three L166P simulations, once the Glu-18 side chain pulls out of its initial buried position within the protein, it is stabilized in an alternative conformation by multiple hydrogen bonds between its carboxylate group and the backbone amide hydrogen atoms of Gly-159, Thr-160 and Ser-161 and with the H α hydrogen atom of the side chain of Ser-161 (Figure 6C).

As shown in Figure 6D, the dimer interface formed by each subunit in the wt structure consists of a large hydrophobic surface. The disruption of α8 in the L166P simulations induces α1 to lose its tight packing with α7 and α8. The hydrophilic Asp-24 and Arg-27 residues located in the C-terminal region of α1 become more solvent exposed, dividing the large hydrophobic surface into two separate surfaces interrupted by a hydrophilic patch.

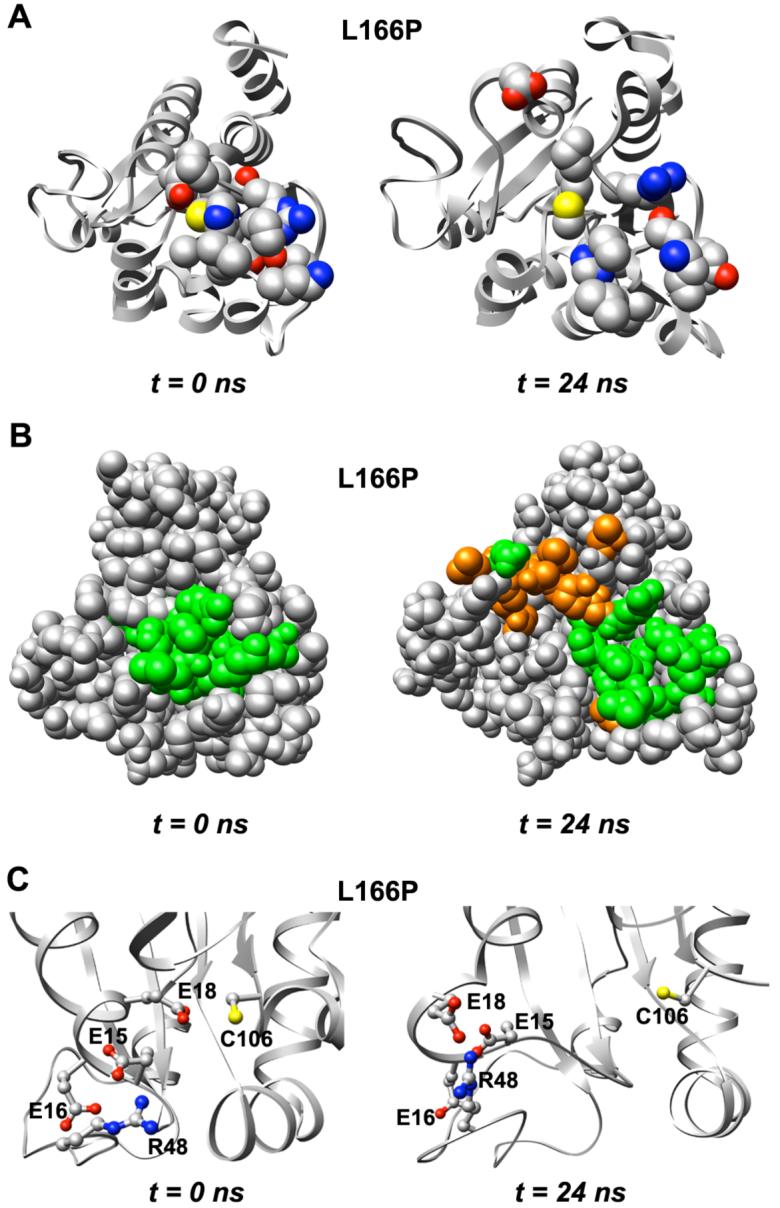

In the wt simulations the distance between the C δ atom of the Glu-18 side chain and the Sγ atom of the Cys-106 side chain increases to an average of only ∼7 Å. Although both wt and L166P simulations show structural distortion of the region around Cys-106, the distortion is more significant in the L166P simulations. The region shows an overall expansion in the L166P simulations, with several tightly packed residues becoming separated (Figure 7A). Many residues near Cys-106 have buried side chains in the starting structure that become exposed to solvent as a result of the expansion, including Ala-14, Glu-15, Thr-19, Ile-21, Gly-75, Gly-157 and Ser-161 (Figure 7B). In addition to Glu-18, the other two acidic residues that are near the Cys-106 side chain in the DJ-1 monomer, Glu-15 and Glu-16, and a basic residue, Arg-48, likewise move away from Cys-106 (Figure 7C).

Figure 7.

Expansion of structure around conserved Cys-106 in L166P DJ-1. (A) Residues that have atoms located within 4 Å of Cys-106 (shown with yellow sulfur atom) or His-126 in the starting structure (left) are displayed in CPK format. (B) Space-filling view of L166P DJ-1 and expansion of structure around Cys-106. Residues displayed in CPK format in part A are colored green (left). Residues other than those depicted in CPK format in part A and that experience increased solvent exposure as a result of the structural expansion are shown in orange for the structure at 24 ns (right). (C) Two acidic residues near the Glu-18 side chain, Glu-15 and Glu-16, as well as the basic residue Arg-48, move away from Cys-106.

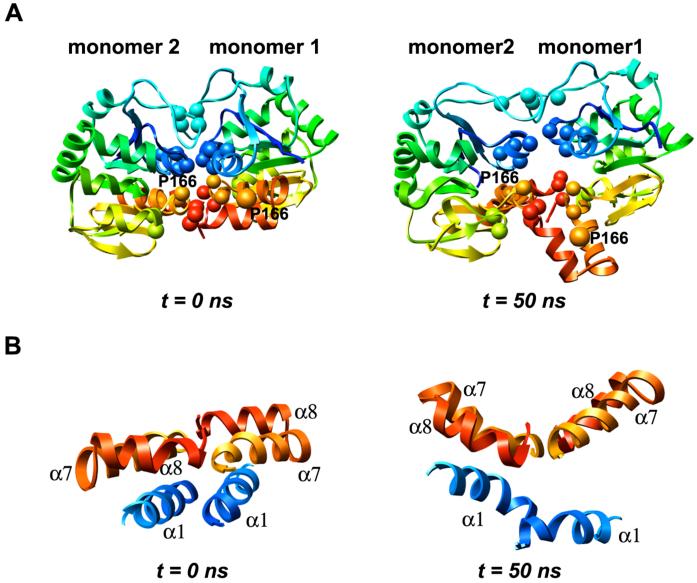

Effects of L166P substitution on global DJ-1 dimer structure

Although the L166P DJ-1 polymorph is not observed as a dimer experimentally, we undertook to predict the structural effects that would arise if both subunits of the wt dimer were subjected to the L166P substitution. The structural effects of the substitution in both subunits on the dimer interface may help to elucidate further the reasons for the failure of L166P DJ-1 to form a dimer. The substitution was introduced into both subunits of the wt dimer. In contrast to the L166P monomer simulations, the average Cα-RMS fluctuations of the three wt and the three L166P dimer simulations are equal throughout most of the structure. The Cα-RMSF of the L166P dimer exceeds that of the wt dimer only in α7 of each subunit. In the wt dimer, the average Cα-RMS deviations of subunit 1 and subunit 2 relative to the starting structure are 2.6 Å and 2.5 Å, respectively. In the L166P dimer, subunit 1 and subunit 2 have average Cα-RMS deviations of 2.9 Å and 2.5 Å, respectively, indicating that subunit 1 experiences a more pronounced structural distortion due to the amino acid substitution than subunit 2.

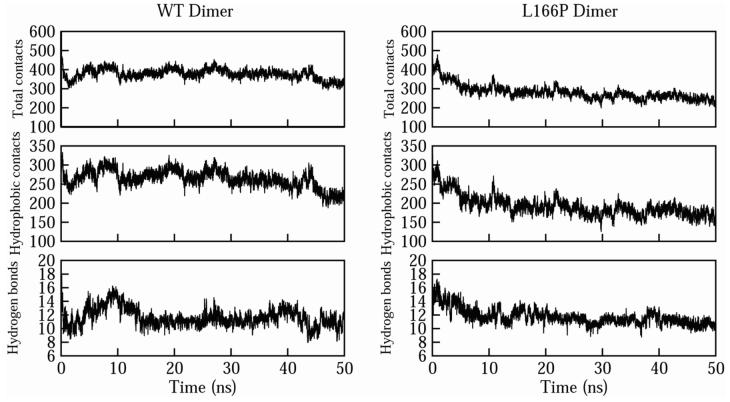

Effect of L166P substitution on DJ-1 dimer interface

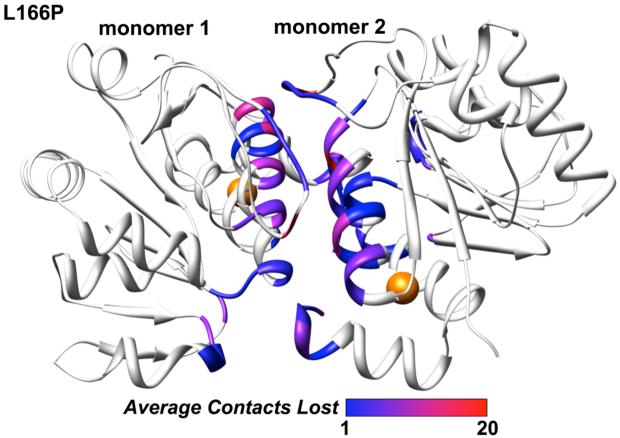

Replacement of Leu by Pro at residue 166 in both subunits of the wt dimer led to severe disruption of the dimer interface (Figures 8 and 9). In the wt structure there is tight packing between the two subunits at the interface and ∼500 total intermolecular atomic contacts are formed. Many hydrophobic interactions are formed across the wt interface, mediated mainly by Met-17, Val-20, Ile-21, Val-23, Val-50, Ile-52, His-126, Pro-127, Pro-158, Phe-162, Pro-184, Leu-185 and Val-186. The tight packing across the interface in the starting structure for the L166P simulation is significantly interrupted within 50 ns as these hydrophobic residues pull apart, leaving a greater distance between the two subunits’ interacting surfaces (Figure 8A). In the wt simulations the numbers of total intermolecular contacts and intermolecular hydrophobic contacts remain roughly constant at ∼375 and ∼275, respectively, after the first 5-10 ns (Figure 9). In contrast, these numbers decrease quickly in the L166P simulations, reaching ∼250 and ∼150 within 50 ns. Despite the decrease in intermolecular contacts, the number of hydrogen bonds maintained across the dimer interface does not differ considerably between the wt and L166P simulations. The parallel α1 helices in each subunit lose the largest number of contacts among secondary structural elements in all three L166P simulations (Figure 10). Met-17 and Arg-48 of subunit 1, located in α1 and in the turn between β3 and β4, respectively, have the largest average decrease in total number of intermolecular contacts, each losing 19 atomic contacts. Asp-24 and Arg-27 of subunit 2, located in α1, lose an average of 14 and 13 total intermolecular atomic contacts, respectively, while Arg-48 of subunit 2 loses 15 total intermolecular atomic contacts. Table 1 lists the largest average intermolecular residue-residue contact losses for the mutant dimer interface.

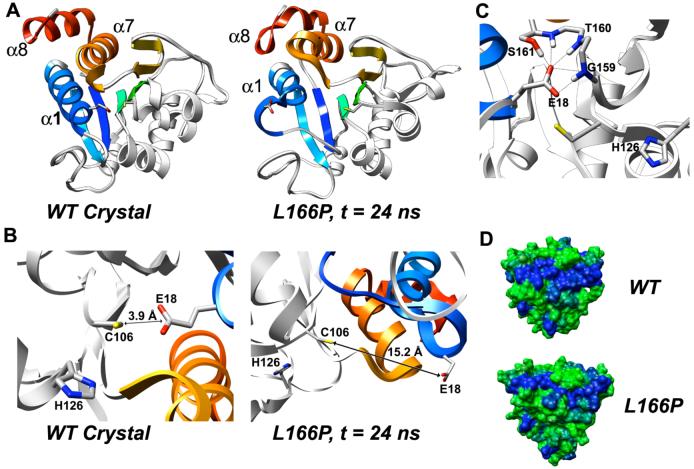

Figure 8.

Perturbations in the DJ-1 dimer interface following L166P substitution in each subunit. (A) Loss of intermolecular contacts that mediate DJ-1 dimerization after 50 ns. Key hydrophobic interactions across the interface are formed by Met-17, Val-20, Ile-21, Val-23, Val-50, Ile-52, His-126, Pro-127, Pro-158, Phe-162, Pro-184, Leu-185 and Val-186, which are represented by spheres in both subunits. Residue 166 positions are indicated by orange spheres. (B) Helices α7 and α8 from both subunits are roughly coplanar in the wt simulations and in the starting structure for L166P simulations (left). During the L166P simulations the α7-turn-α8 motif in subunit 1 loses packing with α1 and moves out of the plane of the opposite α7-turn-α8 motif, undergoing a dynamic swinging motion that creates a V-shape with the opposite motif (right).

Figure 9.

Effects of L166P substitution on intermolecular contacts across the DJ-1 dimer interface. The average numbers of total intermolecular contacts (top), hydrophobic contacts (center), and hydrogen bonds (bottom) are plotted for the wt simulations (left) and L166P simulations (right).

Figure 10.

Loss of atomic intermolecular contacts across L166P DJ-1 dimer interface. The color for each residue corresponds to the average number of total contacts lost by that residue across the interface during the course of the three L166P simulations. The color scale spans the range from 1 (blue) to 20 (red). Residues that do not constitute the interface are not colored. Positions of residue 166 are indicated by orange spheres.

Table 1.

Principal residue-residue contact losses for L166P DJ-1 dimer simulations. The right-hand column lists the average numbers of total atomic contacts lost in L166P simulations relative to wt simulations between the two indicated residues

| Subunit 1 residue | Subunit 2 residue | Lost intermolecular atomic contacts relative to wt |

|---|---|---|

| Lys-188 | Lys-188 | 10 |

| Arg-48 | Arg-27 | 8 |

| Arg-27 | Arg-48 | 8 |

| Arg-48 | Arg-28 | 7 |

| Asp-24 | Arg-48 | 7 |

| Met-17 | Asp-24 | 6 |

| Arg-28 | Glu-15 | 6 |

| Pro-184 | His-126 | 6 |

| Asp-49 | Arg-27 | 6 |

| Glu-16 | Asp-24 | 5 |

| His-126 | Pro-184 | 5 |

Dimerization of wt DJ-1 is mediated in part by interactions between the β11-α7 loop in one subunit and residues near the C-terminus of α8 in the opposite subunit. Among these interactions is a critical hydrogen bond formed between the Nε atom of His-126 and the backbone carbonyl oxygen atom of the Pro-184 residue of the opposite subunit. This hydrogen bond is found at both ends of the dimer interface. In two of the three wt simulations this hydrogen bond is conserved at both ends of the interface for the duration of the trajectories. In the L166P simulations, however, the hydrogen bond is easily disrupted. In L166P simulation 1, the β11-α7 loop of subunit 1 pulls away from the C-terminal end of α8 of subunit 2, permanently breaking the hydrogen bond. The corresponding hydrogen bond at the other end of the interface is not disrupted. In L166P simulations 2 and 3, the β11-α7 loops at both ends of the interface pull away from their respective opposite α8 helices, breaking the hydrogen bond at both interface ends and interrupting several other interresidue atomic contacts. The disruption of these hydrogen bonds is associated with a loss of stability of the coplanar arrangement of the α7-turn-α8 motifs of the two subunits. The substitution causes α1 and α7 in subunit 1 to lose their tight packing with one another, which frees the α7-turn-α8 motif of subunit 1 to protrude outward into solution, forming a V-shape with the α7-turn-α8 motif of subunit 2 (Figure 8B).

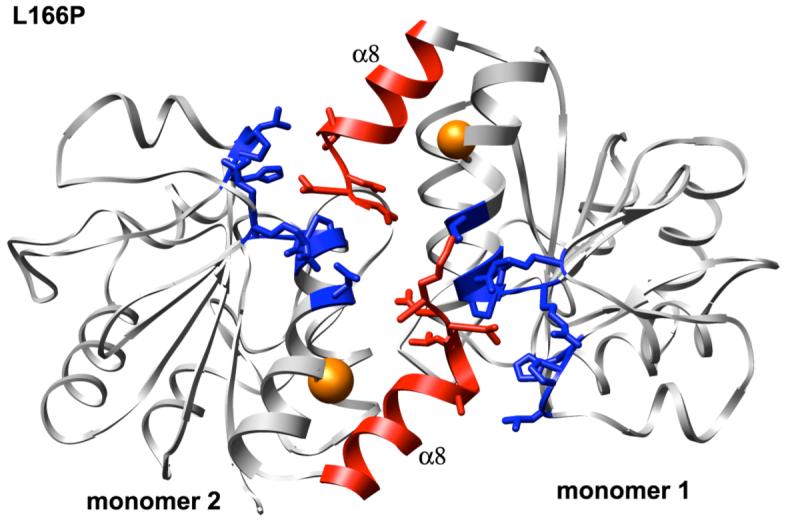

L166P substitution influence on DJ-1 dimer secondary structure

The dimeric DJ-1 structure is highly prone to lose α-helical content after introduction of the L166P substitution. As in the wt monomer simulations α1 and α6 lose their helical structure along with α5. Unlike the L166P monomer simulations, however, the dimer simulations show no loss of helical content in α8. The relative stability of α8 in the dimer is potentially attributable to the intermolecular contacts that its C-terminal end forms with the β11-loop-α7, β8-loop-α6 and β9-loop-β10 motifs of the opposite subunit (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Intermolecular contacts formed by the C-terminal ends of helices α8 in each subunit of L166P DJ-1 dimer structure. Side chains of amino acid residues in α8 (red) and in the opposite subunit (blue) that form contacts across the dimer interface are shown in stick format. Positions of residue 166 are indicated by orange spheres.

Disruption of DJ-1 dimer structure near highly conserved Cys-106 residue induced by L166P

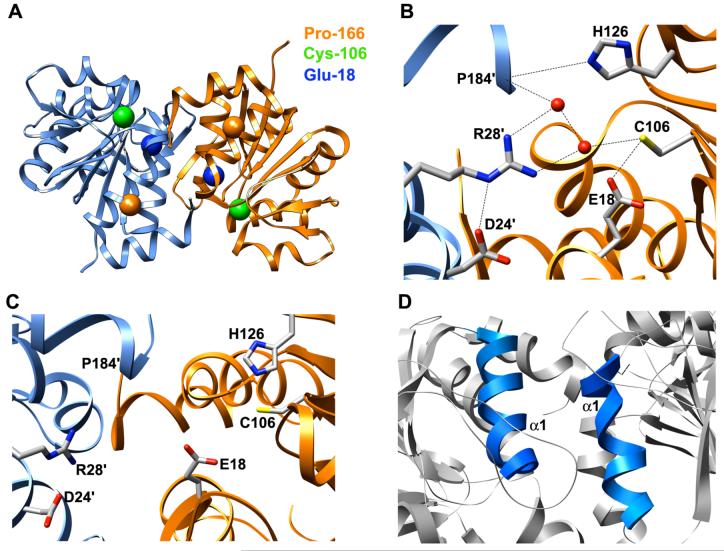

The conserved Cys-106 and Glu-18 residues of DJ-1 are located near the dimer interface (Figure 12A). The side chains of both residues make important contributions to wt DJ-1 dimer stability by participating in a network of intramolecular and intermolecular hydrogen bonds (Figure 12B). The wt Cys-106 side chain forms a water-mediated hydrogen bond with the Nη2 atom of the side chain guanidinium group of Arg-28′ in the opposite subunit. The Nη1 atom of the Arg-28′ guanidinium group forms a water-mediated hydrogen bond with the backbone carbonyl oxygen atom of Pro-184′, which itself interacts with the His-126 side chain across the dimer interface. The Asp-24′ side chain carbonyl group forms a direct hydrogen bond with the Nε atom of Arg-28′. Cys-106 also forms a hydrogen bond with the Glu-18 side chain, stabilizing the N-terminal portion of α1. This network of hydrogen bonds contributes to dimer formation. Likewise, since α1 is also an essential mediator of dimer formation, it is important that α1 secondary structure remain stable.

Figure 12.

Disruption of structure around conserved Cys-106 in L166P DJ-1 dimer simulations. (A) L166P DJ-1 dimer starting structure showing positions of Pro-166 (orange spheres), Cys-106 (green spheres) and Glu-18 (blue spheres). Subunits 1 and 2 are colored orange and blue, respectively. (B) Hydrogen bonding network involving conserved Cys-106 side chain in DJ-1 wt dimer crystal structure. Oxygen atoms of waters participating in hydrogen bonds are represented as red spheres. Hydrogen bonds are denoted by dotted lines. (C) Disruption of hydrogen bonding network shown in part B caused by L166P substitution in DJ-1 dimer. (D) Distortion of α-helical structure of N-terminal end of α1.

The positions of the side chains of Cys-106, Glu-18, His-126, Arg-28′, Asp-24′ and Pro-184′ that participate in this hydrogen bond network are not perturbed in the wt simulations and the overall structure of this region is well maintained. In contrast, the L166P dimer simulations indicate that the substitution causes a significant reorientation of the side chains involved in the hydrogen bond network such that all of the hydrogen bonds are interrupted (Figure 12C). The His-126 residue changes its orientation so that its side chain no longer forms a hydrogen bond with Pro-184′ in the C-terminal end of α8 of the opposite subunit, forming instead contacts with the strand-turn-helix motif formed by β7 and α5. The Cys-106 side chain also rotates so that it becomes buried in the loop between β11 and α7 and loses hydrogen bonds with water and Glu-18. Similarly to the L166P monomer simulations, the Glu-18 side chain becomes increasingly separated from the Cys-106 side chain. The average distance between the Oε1 atom of the Glu-18 side chain and the Cys-106 side chain Sγ atom is ∼7 Å in the L166P dimer simulations but only ∼4 Å in the wt dimer simulations. This increased separation between Cys-106 and Glu-18 is accompanied by a disruption of helical structure in the N-terminal end of α1 (Figure 12D). In addition, the Asp-24′ and Arg-28′ side chains, which participate in water-mediated hydrogen bonds between the two subunits in the wt structure, lose an average of thirteen intermolecular atomic contacts with the opposite subunit.

Similarly to the L166P monomer simulations, the strained backbone conformation of Cys-106 is relieved in the L166P dimer simulations. The side chains of Glu-15, Glu-16 and Arg-48 become increasingly separated from the Cys-106 side chain, as do the Asp-24′ and Arg-28′ side chains of the opposite subunit (Figure 12C).

Hydrophobic surface area increase in L166P DJ-1

The L166P substitution causes the α7-turn-α8 motif to pull away from the central β-sheet (Figure 8). This separation partially exposes the β-sheet to solvent, increasing the SASA of the hydrophobic residues of three of the β-strands (β1, β6 and β7). The total SASA values of β1, β6 and β7 increase from 1Å2, 3 Å2 and 12 Å2 in the starting structure to 11 Å2, 46 Å2 and 91 Å2, respectively, corresponding to a nine-fold increase in surface area of this portion of the β-sheet. Increases in solvent exposure of the β-sheet and the hydrophobic residues of α7 and α8 enlarge the total hydrophobic surface area of L166P DJ-1 by 30% relative to wt simulations (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Increase in hydrophobic SASA of L166P DJ-1 (right) relative to wt (left). Molecular surface is colored by residue from least hydrophobic (green) to most hydrophobic (blue). Ribbons are colored red for entire protein structure. Both structures have been aligned by C α-RMSD.

DISCUSSION

The absence of atomic-resolution structures of L166P DJ-1 in solution has prevented detailed characterization of the specific structural disruptions that result from this mutation. A previous MD study (44) of wt DJ-1 and several polymorphs focused on the structural effects of the oxidation state of wt DJ-1 and of the M26I and R98Q substitutions. Although the study addressed the L166P substitution, detailed information about the substitution’s effects on DJ-1 secondary structure distant from the L166P substitution site, overall helical content, global destabilization, specific residue-residue contact losses beyond the region of the substitution site, and hydrophobic SASA was not presented. The simulations in the present work thus complement the insight gained from the previous study to provide a more comprehensive view of the molecular framework for DJ-1 structural destabilization and loss of function.

MD simulations of both wt and L166P DJ-1 were performed for monomeric and dimeric protein at physiological temperature, providing a total simulation time of ∼350 ns. Simulations of wt DJ-1 show particularly high backbone mobility in the loop between β2 and β3, in agreement with NMR studies (31), as well as in α6 and α8. The L166P substitution causes increased backbone mobility in several regions of the protein, particularly in the β1-turn-α1 motif and in the turn between β3 and β4, which are adjacent to one another. L166P simulations demonstrated a much wider distribution of Cα-RMS fluctuations than the wt simulations, indicating overall destabilization of the mutant protein structure.

The mutant protein undergoes a major loss of helicity in the C-terminal portion of α8 within 15 ns. This loss appears to result from the disruption by Pro-166 of 17 hydrophobic contacts that are formed in the wt structure between Leu-166 and nearby residues in α1, α7 and α8. α1 is also disrupted at its N-terminal end ∼3 ns before α8 disruption and α6 loses helicity shortly after α8. The pronounced backbone mobility increase in the β1-turn-α1 motif observed for the mutant protein relative to wt is consistent with the loss of helical stability in the N-terminal portion of α1. Contacts between the β1-turn-α1 motif and the turn between β3 and β4 are interrupted as a result of the α1 helical loss, subsequently destabilizing the turn and also increasing its backbone mobility. The decrease in overall α-helical content observed in the simulations agrees with CD spectra that show relatively little α-helical structure in L166P DJ-1 (20). Despite the large decrease in α-helical content throughout the protein, the central β-sheet is not disturbed by the L166P substitution and total β-strand content remains steady. The mutant protein thus appears to be most highly susceptible to secondary structure disruption in its α-helices.

Helical loss in the N-terminal end of α1 breaks a hydrogen bond between the highly conserved Cys-106 side chain and Glu-18. This hydrogen bond interruption is associated not only with α1 helicity loss but also with an increased separation of α1 from the central β-sheet. Helicity loss in α8 reduces the tight packing of α1 with α7 and α8, permitting Asp-24 and Arg-27 in the C-terminal region of α1 to become more exposed to solvent. The large hydrophobic surface that mediates dimer formation thus becomes divided into two separate hydrophobic surfaces interrupted by a small hydrophilic patch. This hydrophobic surface, along with all of α1, the C-terminus of α8 and the Cys-106 hydrogen bond with Glu-18, is essential for the DJ-1 dimer. The disruption of these structures likely abrogates the necessary stabilizing interactions between the dimer subunits and therefore would be expected to abolish dimer formation for the L166P polymorph.

Disruption of the dimer interface was also observed after substitution of Pro-166 for Leu-166 in each subunit of the WT DJ-1 dimer. Since a stable L166P DJ-1 dimer is not observed experimentally, it would be expected that introducing the mutation into each subunit of a pre-formed WT dimer would destabilize the dimer. Simulations of the mutant dimer supported this expectation. Within 50 ns the two interacting faces of the subunits begin to separate, losing ∼125 intermolecular contacts, 33% of the total number of contacts, with the parallel α1 helices undergoing the largest number of contact losses. α1, α5 and α6 are disrupted in the mutant dimer. However, within the timescale of the dimer simulations, α8 does not lose helical content, presumably due to a hydrogen bond formed between its C-terminus and the β11-loop-α7 motif of the opposite subunit. Thus, as also observed for the DJ-1 monomer, it seems that α8 destabilization is not a necessary precondition for α1 helical loss. Subtle distortions introduced into the N-terminal portion of α7 by the mutation are sufficient to break stabilizing interactions with and hence helical loss in the N-terminal portion of α1, which appears to be a key reason for the failure of L166P DJ-1 to form a stable dimer.

The putative chaperone function of DJ-1 relies on its sensing of oxidative stress by Cys-106 toward reactive oxygen species (19, 29). The particular reactivity of Cys-106 may result from its strained backbone conformation or the proximity of a cluster of four acidic residues (Glu-15, Glu-16, Glu-18, Asp-24′) and two basic residues (Arg-48, Arg-28′) (19). The side chains of these residues move away from Cys-106 in the L166P DJ-1 monomer and dimer simulations, leaving the Cys-106 side chain surrounded by different chemical and electrostatic environments devoid of several hydrogen bonding, charge and dipolar interactions. These interactions, along with the backbone conformation of Cys-106, can have a significant effect on the pKa of the Cys-106 side chain thiol (45). The changed chemical environment and relief of the strained backbone may thus perturb the reactivity of Cys-106, altering the ability of DJ-1 to sense oxidative stress conditions.

Several groups have reported that L166P DJ-1 forms oligomers and/or aggregates in vivo (10, 20, 33, 34). Simulations of mutant protein suggested that the L166P substitution significantly increases the exposure of hydrophobic residues to solvent, namely those of α7 and α8 in the vicinity of the substitution and β1, β6 and β7 of the central β-sheet. The total hydrophobic SASA increases by an average of ∼30% relative to wt DJ-1, potentially reducing the protein’s solubility and enhancing its tendency to form oligomers or aggregates. It has also been reported that proper conjugation of SUMO-1 to Lys-130 is necessary in order for wt DJ-1 to perform various activities in vivo, including ras-dependent transformation and cell growth promotion (46). L166P DJ-1 was shown to be improperly sumoylated and made insoluble, possibly due to easier accessibility and subsequent sumoylation of multiple lysine residues (46). The MD simulations show that the Lys-132 side chain, following the helical loss of α6, loses its packing with side chains of α3 and α5 and becomes considerably more exposed to solvent. Similarly, Lys-63 and Lys-93 lose their packing with side chains of α2 and the α5-loop-α6 motif, respectively, becoming highly exposed to solvent. Thus, it is possible that the side chains of Lys-63, Lys-93 and Lys-132 may serve as accessible sites for improper sumoylation and consequent loss of DJ-1 solubility.

Introduction of a compensatory mutation may potentially stabilize the DJ-1 L166P structure and restore its function. The simulations reveal that one of the most prominent structural changes associated with the L166P substitution is the separation of the side chains of Glu-18 and Cys-106, which form a hydrogen bond in the wt structure. Separation of these two residues facilitates the partial loss of helical structure observed in α1 and is thus linked to the major perturbations of structure near the conserved Cys-106. Since α1 structural integrity and the interaction between Glu-18 and Cys-106 are important for dimer formation, reinforcing the latter could prevent destabilization of the dimer interface. The mutation I105C appears to allow both oxygen atoms of the Glu-18 side chain carboxylate group to form hydrogen bonds. One of the Glu-18 Oε side chain atoms could continue to accept a hydrogen bond from the Cys-106 Sγ side chain atom, while the second Oε atom could accept a hydrogen bond from Cys-105. In the wt structure Glu-18 forms only a single hydrogen bond with Cys-106, whose side chain conformation quickly changes in the L166P simulations, breaking the hydrogen bond. It is conceivable that by inducing the Glu-18 side chain to maintain an extra hydrogen bond through its side chain, it would be stabilized even if its hydrogen bond with Cys-106 were eventually disrupted. The potentially compensatory I105C mutation may then serve to lock Cys-106 in place and to prevent the N-terminal end of α1 from losing its helical structure.

CONCLUSIONS

The MD simulations presented here provide insight into the structural, dynamic and destabilizing effects of the L166P substitution in both the DJ-1 monomer and dimer at physiological temperature. Within the time scale of the monomer simulations (∼25 ns), a significant amount of α-helical content is lost throughout the L166P DJ-1 structure. The most pronounced α-helix disruptions occur at the C-terminal portion of α8 and in the N-terminal portions of α1 and α6. It is likely that destabilization of α1 and α8 contributes to the inability of L166P DJ-1 to form a dimer in vitro, as both helices are crucial mediators of dimer formation. The L166P substitution also destabilizes the overall DJ-1 structure, which exists in a broader range of conformational states than the wt structure. Structural changes associated with the L166P substitution are able to propagate to the highly conserved Cys-106 and Glu-18 residues, situated ∼16 Å away from residue 166, significantly disordering and opening up the major surface depression in which Cys-106 is situated so that it is exposed to solvent. The Cys-106 and Glu-18 side chains increase their separation and the hydrogen bond stabilizing their interaction is disrupted, which is associated with the loss of helicity in the N-terminal portion of α1. The observed disturbance of the chemical and electrostatic environments of the Cys-106 side chain may interfere with its ability to function as a sensor of oxidative stress and as an activator of DJ-1 chaperone function. Introduction of the substitution into the wt dimer structure likewise perturbs the region around Cys-106, separating it from side chains contributed by the opposite subunit. The substitution also causes disruption of contacts across the dimer interface that are required for dimer formation, most notably those between α1 of both subunits. A large increase in solvent-exposed hydrophobic surface area in the L166P polymorph may contribute to its tendency to form aggregates or oligomers.

These results are in general agreement with experimental observations that L166P DJ-1 loses α-helical content in L166P DJ-1, fails to form a dimer and cannot function as a chaperone. Our MD simulations thus provide detailed information at atomic resolution that cannot be obtained experimentally due to the inherent instability of L166P DJ-1.

Abbreviations

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- wt

wild-type

- CD

circular dichroism

- MD

molecular dynamics

- ilmm

in lucem Molecular Mechanics

- RMSD

root-mean-square deviation

- RMSF

root-mean-square fluctuation

- SASA

solvent-accessible surface area

Footnotes

Financial support for this work was provided by National Institutes of Health Grant NLM #T15 LM07442 (to P.A.). We are grateful for support from Microsoft Research through Technical Computing @ Microsoft (www.microsoft.com/science). This study is a part of our on-going Dynameomics project (www.dynameomics.org).

REFERENCES

- 1.Farrer MJ. Genetics of Parkinson disease: paradigm shifts and future prospects. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2006;7:306–318. doi: 10.1038/nrg1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spillantini MG, Schmidt ML, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Jakes R, Goedert M. Alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature. 1997;388:839–840. doi: 10.1038/42166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kitada T, Asakawa S, Hattori N, Matsumine H, Yamamura Y, Minoshima S, Yokochi M, Mizuno Y, Shimizu N. Mutations in the parkin gene cause autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism. Nature. 1998;392:605–608. doi: 10.1038/33416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimura H, Hattori N, Kubo S, Mizuno Y, Asakawa S, Minoshima S, Shimizu N, Iwai K, Chiba T, Tanaka K, Suzuki T. Familial Parkinson disease gene product, parkin, is a ubiquitin-protein ligase. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:302–305. doi: 10.1038/77060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leroy E, Boyer R, Auburger G, Leube B, Ulm G, Mezey E, Harta G, Brownstein MJ, Jonnalagada S, Chernova T, Dehejia A, Lavedan C, Gasser T, Steinbach PJ, Wilkinson KD, Polymeropoulos MH. The ubiquitin pathway in Parkinson’s disease. Nature. 1998;395:451–452. doi: 10.1038/26652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valente EM, Abou-Sleiman PM, Caputo V, Muqit MMK, Harvey K, Gispert S, Ali Z, Del Turco D, Bentivoglio AR, Healy DG, Albanese A, Nussbaum R, Gonzalez-Maldonado R, Deller T, Salvi S, Cortelli P, Gilks WP, Latchman DS, Harvey RJ, Dallapiccola B, Auburger G, Wood NW. Hereditary early-onset Parkinson’s disease caused by mutations in PINK1. Science. 2004;304:1158–1160. doi: 10.1126/science.1096284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zimprich A, Biskup S, Leitner P, Lichtner P, Farrer M, Lincoln SJ, Kachergus JM, Hulihan MM, Uitti RJ, Calne DB, Stoessl AJ, Pfeiffer RF, Patenge N, Carballo Carbajal I, Vieregge P, Asmus F, Mueller-Myhsok B, Dickson DW, Meitinger T, Gasser T. Mutations in a large multifunctional protein (LRRK2) cause autosomal dominant parkinsonism with pleiomorphic α-synuclein and tau-pathology (PARK8) Neuron. 2004;44:601–607. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramirez A, Heimbach A, Grundemann J, Stiller B, Hampshire D, Pablo LP, Goebel I, Mubaidin AF, Wriekat AL, Roeber J, Al-Din A, Hillmer AM, Karsak M, Liss B, Woods CG, Behrens MI, Kubisch C. Hereditary parkinsonism with dementia is caused by mutations in ATP13A2, encoding a lysosomal type 5 P-type ATPase. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:1184–1191. doi: 10.1038/ng1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belin AC, Westerlund M. Parkinson’s disease: a genetic perspective. FEBS J. 2008;275:1377–1383. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonifati V, Rizzu P, van Baren Marijke J, Schaap O, Breedveld Guido J, Krieger E, Dekker Marieke CJ, Squitieri F, Ibanez P, Joosse M, van Dongen Jeroen W, Vanacore N, van Swieten John C, Brice A, Meco G, van Duijn Cornelia M, Oostra Ben A, Heutink P. Mutations in the DJ-1 gene associated with autosomal recessive early-onset parkinsonism. Science. 2003;299:256–259. doi: 10.1126/science.1077209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagakubo D, Taira T, Kitaura H, Ikeda M, Tamai K, Iguchi-Ariga SMM, Ariga H. DJ-1, a novel oncogene which transforms mouse NIH3T3 cells in cooperation with ras. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;231:509–513. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Le Naour F, Misek DE, Krause MC, Deneux L, Giordano TJ, Scholl S, Hanash SM. Proteomics-based identification of RS/DJ-1 as a novel circulating tumor antigen in breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2001;7:3328–3335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hod Y, Pentyala SN, Whyard TC, El-Maghrabi MR. Identification and characterization of a novel protein that regulates RNA-protein interaction. J. Cell. Biochem. 1999;72:435–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim RH, Peters M, Jang Y, Shi W, Pintilie M, Fletcher GC, DeLuca C, Liepa J, Zhou L, Snow B, Binari RC, Manoukian AS, Bray MR, Liu FF, Tsao MS, Mak TW. DJ-1, a novel regulator of the tumor suppressor PTEN. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:263–273. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niki T, Takahashi-Niki K, Taira T, Iguchi-Ariga SMM, Ariga H. DJBP: A novel DJ-1-binding protein, negatively regulates the androgen receptor by recruiting histone deacetylase complex, and DJ-1 antagonizes this inhibition by abrogation of this complex. Mol. Cancer Res. 2003;1:247–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shinbo Y, Taira T, Niki T, Iguchi-Ariga SM, Ariga H. DJ-1 restores p53 transcription activity inhibited by Topors/p53BP3. Int. J. Oncol. 2005;26:641–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takahashi K, Taira T, Niki T, Seino C, Iguchi-Ariga SMM, Ariga H. DJ-1 positively regulates the androgen receptor by impairing the binding of PIASxalpha to the receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:37556–37563. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101730200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu J, Zhong N, Wang H, Elias JE, Kim CY, Woldman I, Pifl C, Gygi SP, Geula C, Yankner BA. The Parkinson’s disease-associated DJ-1 protein is a transcriptional co-activator that protects against neuronal apoptosis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005;14:1231–1241. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andres-Mateos E, Perier C, Zhang L, Blanchard-Fillion B, Greco TM, Thomas B, Ko HS, Sasaki M, Ischiropoulos H, Przedborski S, Dawson TM, Dawson VL. DJ-1 gene deletion reveals that DJ-1 is an atypical peroxiredoxin-like peroxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:14807–14812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703219104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olzmann JA, Brown K, Wilkinson KD, Rees HD, Huai Q, Ke H, Levey AI, Li L, Chin L-S. Familial Parkinson’s disease-associated L166P mutation disrupts DJ-1 protein folding and function. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:8506–8515. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311017200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee S-J, Kim SJ, Kim I-K, Ko J, Jeong C-S, Kim G-H, Park C, Kang S-O, Suh P-G, Lee H-S, Cha S-S. Crystal structures of human DJ-1 and Escherichia coli Hsp31, which share an evolutionarily conserved domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:44552–44559. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304517200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilson MA, St. Amour CV, Collins JL, Ringe D, Petsko GA. The 1.8-A resolution crystal structure of YDR533Cp from Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a member of the DJ-1/ThiJ/PfpI superfamily. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:1531–1536. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308089100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shendelman S, Jonason A, Martinat C, Leete T, Abeliovich A. DJ-1 is a redox-dependent molecular chaperone that inhibits alpha-synuclein aggregate formation. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:1764–1773. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou W, Zhu M, Wilson MA, Petsko GA, Fink AL. The oxidation state of DJ-1 regulates its chaperone activity toward alpha-synuclein. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;356:1036–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Honbou K, Suzuki NN, Horiuchi M, Niki T, Taira T, Ariga H, Inagaki F. The crystal structure of DJ-1, a protein related to male fertility and Parkinson’s disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:31380–31384. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305878200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tao X, Tong L. Crystal structure of human DJ-1, a protein associated with early onset Parkinson’s disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:31372–31379. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304221200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilson MA, Collins JL, Hod Y, Ringe D, Petsko GA. The 1.1-A resolution crystal structure of DJ-1, the protein mutated in autosomal recessive early onset Parkinson’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:9256–9261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1133288100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horvath MM, Grishin NV. The C-terminal domain of HPII catalase is a member of the type I glutamine amidotransferase superfamily. Proteins. 2001;42:230–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kinumi T, Kimata J, Taira T, Ariga H, Niki E. Cysteine-106 of DJ-1 is the most sensitive cysteine residue to hydrogen peroxide-mediated oxidation in vivo in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;317:722–728. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.03.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goerner K, Holtorf E, Odoy S, Nuscher B, Yamamoto A, Regula JT, Beyer K, Haass C, Kahle PJ. Differential effects of Parkinson’s Disease-associated mutations on stability and folding of DJ-1. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:6943–6951. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309204200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malgieri G, Eliezer D. Structural effects of Parkinson’s disease linked DJ-1 mutations. Protein Sci. 2008;17:855–868. doi: 10.1110/ps.073411608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller DW, Ahmad R, Hague S, Baptista MJ, Canet-Aviles R, McLendon C, Carter DM, Zhu P-P, Stadler J, Chandran J, Klinefelter GR, Blackstone C, Cookson MR. L166P Mutant DJ-1, Causative for Recessive Parkinson’s Disease, Is Degraded through the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:36588–36595. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304272200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baulac S, LaVoie MJ, Strahle J, Schlossmacher MG, Xia W. Dimerization of Parkinson’s disease-causing DJ-1 and formation of high molecular weight complexes in human brain. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2004;27:236–246. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Macedo MG, Anar B, Bronner IF, Cannella M, Squitieri F, Bonifati V, Hoogeveen A, Heutink P, Rizzu P. The DJ-1L166P mutant protein associated with early onset Parkinson’s disease is unstable and forms higher-order protein complexes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003;12:2807–2816. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levitt M. ENCAD, Energy Calculations and Dynamics. Stanford University; Palo Alto, CA: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levitt M, Hirshberg R, Sharon R, Daggett V. Potential energy function and parameters for simulations of the molecular dynamics of proteins and nucleic acids in solution. Comput. Phys. Commun. 1995;91:215–231. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levitt M, Hirshberg R, Sharon R, Laidig KE, Daggett V. Calibration and testing of a water model for simulation of the molecular dynamics of proteins and nucleic acids in solution. J. Phys. Chem. 1997;101:5051–5061. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kell GS. Precise representation of volume properties of water at one atmosphere. J. Chem. Eng. Data. 1967;12:66–69. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beck DAC, Alonso DOV, Daggett V. ilmm, in lucem Molecular Mechanics. University of Washington; Seattle, WA: 20002008. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beck DAC, Daggett V. Methods for the molecular dynamics simulations of protein folding/unfolding in solution. Methods. 2004;34:112–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hubbard SJ, Thornton JM. University College; London: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kabsch W, Sander C. Dictionary of protein secondary structure: pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers. 1983;22:2577–2637. doi: 10.1002/bip.360221211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. UCSF Chimera-a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Herrera F, Zucchelli S, Jezierska A, Lavina ZS, Gustincich S, Carloni P. On the oligomeric state of DJ-1 protein and its mutants associated with Parkinson’s disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:24905–24914. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701013200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salisbury FR, Jr., Knutson ST, Poole LB, Fetrow JS. Functional site profiling and electrostatic analysis of cysteines modifiable to cysteine sulfenic acid. Protein Sci. 2008;17:299–312. doi: 10.1110/ps.073096508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shinbo Y, Niki T, Taira T, Ooe H, Takahashi-Niki K, Maita C, Seino C, Iguchi-Ariga SM, Ariga H. Proper SUMO-1 conjugation is essential to DJ-1 to exert its full activities. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:96–108. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kyte J, Doolittle RF. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J. Mol. Biol. 1982;157:105–132. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]