Abstract

Comparative modelling is utilized to predict the 3-dimensional conformation of a given protein (target) based on its sequence alignment to experimentally determined protein structure (template). The use of such technique is already rewarding and increasingly widespread in biological research and drug development. The accuracy of the predictions as commonly accepted depends on the score of sequence identity of the target protein to the template. To assess the relationship between sequence identity and model quality, we carried out an analysis of a set of 4753 sequence and structure alignments. Throughout this research, the model accuracy was measured by root mean square deviations of Cα atoms of the target-template structures. Surprisingly, the results show that sequence identity of the target protein to the template is not a good descriptor to predict the accuracy of the 3-D structure model. However, in a large number of cases, comparative modelling with lower sequence identity of target to template proteins led to more accurate 3-D structure model. As a consequence of this study, we suggest new tips for improving the quality of omparative models, particularly for models whose target-template sequence identity is below 50%.

Keywords: comparative modelling, homology modelling, model refinement

Background

The 3D structure determination of a certain protein greatly helps unravelling its function and binding mechanisms. Such structural information can also aids in designing experiments in mutagenesis and even utilized for structure-guided drug development or virtual screening [1–2]. Since experimental structures are available only for a small number of sequenced proteins, alternative strategies are required to predict reliable models for protein structures when X-ray diffraction or NMR are not yet available[3]. Among the different strategies currently used for constructing 3-D structures of certain proteins, we shall find the comparative modelling (termed also as homology modelling) as the most accurate method among the computational methods, yielding reliable models [4–5].

Another approach termed “ab-initio” modelling is not practical yet for the construction of reliable models [6]. Usually, in comparative modelling the template is chosen by virtue of having the highest level of sequence similarity with the target, and similar secondary and tertiary structure (belongs to the same “fold”). Baker and Sali [7] have shown that a comparative model for a protein at medium size at least and with sequence identity of less than 30% to the template crystal structure is unreliable. The rule of sequence identity score exceeding 30% does not specify how identity should be distributed along a sequence. The quality of the models is assessed by comparing predicted structures to X-ray solved structures via superimposition and atomic root mean square deviation assessment (RMSD). A model can be considered ’accurate‘ or ’reliable‘ model when its RMSD is less than 3‐4 Å.

The comparative modelling procedure for protein structure prediction is built generally from few steps: after identification of the homologous protein with known 3-D structure, sequence alignment (based on score of identity or similarity) is performed. Usually, the structurally conserved regions (SCRs) are identified and coordinates for the core of the models are generated. Following the core generation, one predicts the conformations of the structurally variable regions (termed loops)[8] and adds the side chains [9]. Some approaches, align multiple known structures firstly, then, identifying structurally conserved regions to construct an average structure, for modelling these regions of the inquiry protein. The optimal homology-based model is obtained when the correct template is chosen and each residue pair correctly aligned in the target-template sequence alignment[10].

In this communication, we carried out an analysis of a large set of 4753 sequence and structure alignments and tried to answer few questions: (1) Can we predict the accuracy of the modelled structure based on sequence identity score? (2) Is it always justified to select the protein with highest identity score as a template for comparative modelling? (3) How can we improve accuracy of homology-based models?

Methodology

We downloaded about 124 unique proteins which belong to serine protease family from the Brookhaven Protein Databank (PDB) [11–12]. Then, IMSA - Intelligent Multiple Sequence Alignment[13] (in-house software based on the Intelligent Learning Engine (ILE) optimization technology) was utilized to optimally align the whole set of all sequences. Accurate multiple sequence alignment (MSA) is important step that may improve the accuracy of pairwise sequence alignments, minimize misalignments and generate more accurate 3-D models[14–16]. Sequence identity score was calculated for each pair of sequences. All residues from the multiple sequence alignment were found only on 98 proteins (Table 1, see supplementary material). Other twenty eight proteins lack coordinates of one residue at least in their 3-D experimentally determined structures. The alpha carbons (Cα) for residues of selected proteins were extracted from the PDB structures and structurally superimposed.

The quality of the models was assessed via superimposition of the predicted homology-based model (target protein) and the X-ray structure of the protein and then, measurement of the Cα root mean square deviation (Cα RMSD). We have defined ’highly accurate‘ model as the one having ≦2 Å RMSD from the experimentally determined structure, while models having Cα RMSD above this threshold and ≦4 Å were termed “reliable” models. Such reliable models could fit for designing mutagenesis experiments but not for drug design and binding affinity tests. BioLib software was used for performing structural alignment and for computing the Cα RMSD (BioLib is an open-environment developing toolkit developed by BioLog Technologies Ltd.).

The multiple sequence alignment matrix obtained from running our in-house software on the selected database of serine proteases, was processed as described below, in order to specify which parts of the whole set of sequences to select for comparative modelling. We use a “voting” approach, in which each amino acid contributes to the conservation at a sequence position according to its frequency in that particular position (equation 1, under supplementary material). These frequencies are measured in all sequences of the database.

Discussion

In this study, we aim to assess models obtained by comparative modelling by analyzing a large set of sequence/structure alignments that belong to the same family of proteins (adopt the same “fold”). The pair-wise sequence alignments in our database produced sequence identity that ranges between 28% and 100% (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Spread of sequence identities in the database (4753 protein pairs in total)

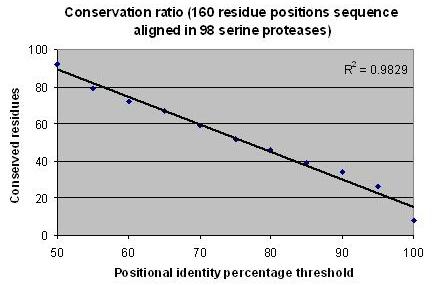

The sequence analysis of the indicated database revealed highly conserved amino acid residues distributed along the protein chain (Figure 2, for number of amino acids found above certain conservation thresholds). We postulate that the orientation of such residues within their spatial coordinates play an important role in the protein function and/or in stabilizing the protein folding (or conformation). Thus, the inter-residue distance matrix should be somehow similar in each protein. This could be assessed qualitatively by extracting those residues from the X-ray structures of the proteins and then performing pair-wise superposition. As depicted in Table 2 (under supplementary material), the Cα RMS deviation is very low in general and correlates well with the Positional Conservation Threshold (PCT). These findings reveal the correctness of the multiple sequence alignment and could be utilized in refinement of models.

Figure 2.

Analysis of positional conservations in the sequences of 98 unique serine proteases. Each protein has 160 residues and the multiple sequence alignment was performed without gaps

4753 models of proteins have been generated and assessed (Figure 3). Models of proteins that were built based on templates that share a certain degree of sequence identity (> 28%) with the target are mostly accurate (≫2 Å RMSD). Such models seem to be useful for drug design and docking experiments. However, when the degree of sequence identity is below 50%, the best template to thread on is not always the one with the highest identity score. To choose the best template for comparative modelling, other protein structures with lower sequence identity should be evaluated.

Figure 3.

This plot describes the sequence identity between target and template sequences and the relative mean square deviation of the models from their corresponding experimental control structure (taking into account only secondary structure segments, based on 1a0j18).

In comparative modelling, two important issues should be taken into consideration in order to avoid inaccuracy in model generation. First, choosing the proper modelling template, as most high deviations between model and experimental control structures can be traced back to the selected modelling templates. Second, conducting the right sequence alignment between the target and template. Any error introduced by the alignment algorithm will have profound effects on the model. Obtaining higher percentage of accuracy highly depends on choosing the correct protein as a template, performing the correct alignment, and choosing the correct stretches to remodel. Position conservation threshold may be used for further refinement of the model via applying molecular dynamics (MD), simulated annealing (SA), iterative stochastic elimination8,17 (ISE) or other optimization approaches.

Conclusion

We present sequence and structural analysis of 4753 pairs of proteins and raise few questions regarding the comparative modelling procedure. We may inquire the justification of the common accepted rule of choosing templates having the highest sequence similarity with the target for comparative modelling. Our findings show that sequence identity of the target to the template is not always a reliable descriptor to predict the accuracy of the 3-D structure model. In a large number of cases, comparative modelling with lower sequence identity of targets to templates led to better 3-D structure models. It is seen clearly when the sequence identity is below 50%. Employing position conservation threshold - PCT (data shown in Table 2, under supplementary material) to refine models is currently under evaluation in our lab. Preliminary results show that such usage is recommended as better homology-based models could be obtained.

Supplementary material

Acknowledgments

I gratefully acknowledge Rand Biotechnologies LTD for supporting this research.

Footnotes

Citation:Rayan, Bioinformation 3(6): 263-267 (2009)

References

- 1.Patny A, et al. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2006;13:1667. doi: 10.2174/092986706777442002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrara P, Jacoby E. J Mol Model. 2007;13:897. doi: 10.1007/s00894-007-0207-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eszter H, Zsolt B. Journal of Structural Biology. Vol. 162. 2008. p. 63. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Furnham N, et al. BMC Struct Biol. 2008;8:89. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-8-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanchez R, Sali A. PNAS. 1998;95:13597. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hardin C, et al. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2002;12:176. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00306-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baker D, Sali A. Science. 2001;294:93. doi: 10.1126/science.1065659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rayan A, et al. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2004;11:675. doi: 10.2174/0929867043455701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glick M, et al. PNAS. 2002;99:703. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roland L, Dunbrack Jr. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 2006;16:374. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berman HM, et al. Nucleic Acids Research. 2000;28:235. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henrick K, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D426. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rayan AM, Raiyn JA. Intelligent Learning Engine (ILE) Optimization Technology, Provisional Patent. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chakravaty S, et al. BMC Structural Biology. 2008;8:31. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-8-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang MS, Benner SA. J Mol Bio. 2004;341:617. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wrabl JO, Grishin NV. Proteins. 2004;54:71. doi: 10.1002/prot.10508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rayan A, et al. J Mol Graph Model. 2004;22:319. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2003.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schroder HK, et al. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54:780. doi: 10.1107/s0907444997018611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.