Abstract

The structure of the protein complex CysM−CysO from a new cysteine biosynthetic pathway found in the H37Rv strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis has been determined at 1.53 Å resolution. CysM (Rv1336) is a PLP-containing β-replacement enzyme and CysO (Rv1335) is a sulfur carrier protein with a ubiquitin-like fold. CysM catalyzes the replacement of the acetyl group of O-acetylserine by CysO thiocarboxylate to generate a protein-bound cysteine that is released in a subsequent proteolysis reaction. The protein complex in the crystal structure is asymmetric with one CysO protomer binding to one end of a CysM dimer. Additionally, the structures of CysM and CysO were determined individually at 2.8 and 2.7 Å resolution, respectively. Sequence alignments with homologues and structural comparisons with CysK, a cysteine synthase that does not utilize a sulfur carrier protein, revealed high conservation of active site residues; however, residues in CysM responsible for CysO binding are not conserved. Comparison of the CysM−CysO binding interface with other sulfur carrier protein complexes revealed a similarity in secondary structural elements that contribute to complex formation in the ThiF−ThiS and MoeB−MoaD systems, despite major differences in overall folds. Comparison of CysM with and without bound CysO revealed conformational changes associated with CysO binding.

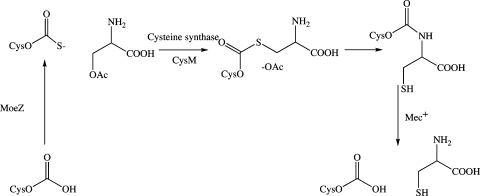

CysM (Rv1336) and CysO (Rv1335) are two proteins that participate in a recently discovered cysteine biosynthesis pathway in Mycobacterium tuberculosis(1). In this pathway CysO thiocarboxylate displaces the acetyl group of O-acetylserine in a reaction catalyzed by the pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP)1 dependent CysM protein. An N−S acyl shift, followed by Mec+ (Rv1334) catalyzed hydrolysis generates cysteine (Figure 1). This pathway stands in contrast to the widely used sulfide-dependent cysteine biosynthesis pathway also present in M. tuberculosis (CysK) and may be of importance in the oxidizing environment of the macrophage (2−6) because thiocarboxylates are much more resistant to oxidation than sulfide. Consistent with this, the genes for CysM and CysO are upregulated when the organism is exposed to oxidative stress (7).

Figure 1.

The new cysteine biosynthetic pathway in M. tuberculosis. All early intermediates are bound to the CysM−CysO complex; however, it is possible that the CysO−thioester adduct is released from CysM before the S−N acyl shift occurs to generate cysteinylated CysO.

Sulfur carrier proteins are structurally homologous to ubiquitin (8) and have now been identified in the biosynthetic pathways for cysteine (1), thiamin (9), molybdopterin (10), and thioquinolobactin (11). Like ubiquitin, the sulfur carrier protein is adenylated at a diglycyl C-terminus by a specific activating protein. The adenylated C-terminus is subsequently converted to a thiocarboxylate, which serves as the sulfide source. Members of the sulfur carrier protein family have diverse binding partners and show little sequence similarity. ThiS is the sulfur carrier protein in thiamin biosynthesis and is activated by ThiF (12). Thiocarboxylated ThiS, deoxy-d-xylulose 5-phosphate, and glycine imine serve as substrates for ThiG in the synthesis of the thiazole moiety of thiamin (13). The sulfur carrier protein MoaD is found in the molybdopterin biosynthetic pathway, and its activating protein is MoeB (14). Crystal structures for the ThiF−ThiS (15), ThiG−ThiS (16), MoeB−MoaD (17), and MoaE−MoaD (10) complexes have been reported. An interesting variation of a sulfur carrier protein is found in the biosynthetic pathway of thioquinolobactin (18). In this system QbsE is the sulfur carrier protein and QbsC is the adenylating protein. QbsE has a diglycyl sequence followed by cysteine and phenylalanine at its C-terminus. Clustered with the genes for these two proteins is a gene for QbsD, a metal-dependent hydrolase, which cleaves the final two amino acids from QbsE generating the diglycyl C-terminus found in all of the other sulfur carrier proteins.

We report here the X-ray crystal structure of the CysM−CysO complex of the cysteine biosynthetic pathway refined to 1.53 Å resolution, the structure of CysM alone at 2.8 Å resolution, and the structure of CysO alone at 2.7 Å resolution. The CysM−CysO complex is asymmetric with one molecule of CysO binding to one end of a CysM dimer. Conformational changes in CysM that occur upon complex formation are described. The CysM−CysO interface is compared to the binding interfaces for ThiF-ThiS, ThiG-ThiS, MoeB-MoaD, MoaE-MoaD, and ubiquitin in complex with the E1-like protein MMS2.

Materials and Methods

Gene Cloning, Overexpression, and Purification

M. tuberculosis DNA was a gift from Clifton Barry at the National Institutes of Health. pET-16b and pET-28a plasmids were purchased from Novagen. All plasmid DNA was purified with a DNA miniprep kit from Promega. A Perkin-Elmer GeneAmp PCR system 2400 and Platinum Pfx DNA polymerase (Gibco Life Technologies) were used for PCR. Primers were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies. Oligonucleotides were prepared using M. tuberculosis DNA as a template for PCR, and sequencing was performed by the Bioresource Center at Cornell University. DNA fragments were purified by agarose gel electrophoresis followed by a QIAquick gel extraction kit from Qiagen. T4 DNA ligase was purchased from New England Biolabs. Escherichia coli strain DH5α was used as a recipient for transformation, propagation, and storage. Primers for the CysM plasmid were engineered to introduce NdeI and BamHI restriction sites at the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively. The forward primer was 5′-GGG TGA GCG GAG CAT ATG ACA CGA TAC GAC-3′. The reverse primer was 5′-TTC GGA TCC GGC GGA TCC TCA TGC CCA TAG-3′. Primers for the CysO plasmid were engineered to introduce NdeI and XhoI restriction sites at the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively. The forward primer was 5′-CCG AGA AAG GCC CAT ATG AAC GTC ACC GTA-3′. The reverse primer was 5′-TCG TGT CAT GTG CTC GAG TCA CCC ACC GGC-3′.

The CysM construct was transformed into B834(DE3) methionine auxotrophic E. coli (Novagen) for overexpression. Minimal media used for overexpression of B834(DE3) cells were prepared by dissolving 11.28 g of M9 salts along with 40 mg/L of each amino acid excluding methionine, which was replaced by selenomethionine at 50 mg/L. The final media also contained 0.4% (w/v%) glucose, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 2 mM MgSO4, 25 mg/mL FeSO4, 100 mg/L ampicillin, and 10 mL of 100× MEM vitamin solution (Invitrogen). Starter cultures were prepared by growing cells in 20 mL of LB media and then spinning the cells at 4800g for 5 min. The LB supernatant was decanted and the cell pellet resuspended with 20 mL of minimal media to inoculate 1 L of minimal media. Cells were grown at 37 °C until an OD600 of 1.0 was reached, followed by induction using 1 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside for 16−18 h at 18 °C. Cell pellets were collected by centrifugation at 6400g for 7 min and placed into a beaker containing 50 mL of a lysis buffer composed of 5 mM imidazole, 0.5 M NaCl, and 20 mM Tris at pH 7.9 to be lysed using sonication. Cell lysate was separated from the insoluble cell particles by centrifugation at 58000g at 4 °C for 20 min. The supernatant was run over a Ni-NTA affinity column equilibrated with lysis buffer. The column was washed with lysis buffer containing 60 mM imidazole and eluted with lysis buffer containing 1 M imidazole. The eluate was buffer exchanged into 20 mM pH 7.9 Tris and 5 mM 1,4-dithiothreitol (DTT) using size exclusion chromatography columns (Bio-Rad DG) with a molecular mass cutoff of 6 kDa. A centrifugal filter (Amicon Ultra) with a molecular mass cutoff of 10 kDa was used to concentrate the solution by spinning at 5000g at 4 °C. The final protein concentration was 10−20 mg/mL as measured using the Bradford assay (19). SDS−PAGE analysis showed a purity of greater than 95%. Native CysM and CysO were transformed into BL21(DE3) cells, overexpressed in LB media, and purified as described above, without the use of DTT.

In an attempt to improve crystallization of CysM alone, a putative surface residue in CysM (Lys204) was mutated to alanine using site-directed mutagenesis. Previous studies have shown that mutation of flexible surface residues can lead to reduced surface entropy and improvement in crystal quality (20). A standard PCR protocol using PfuTurbo DNA polymerase per the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen) and DpnI (New England Biolabs) to digest the methylated parental DNA prior to transformation was used. The forward primer was 5′-GCA CGT TGC CAA CGT CGC GAT CGT GGC GGC CGA ACC CCG C-3′, and the reverse primer was 5′-GCG GGG TTC GGC CGC CAC GAT CGC GAC GTT GGC AAC GTG C-3′. Clones were screened by restriction digest for the introduction of a PvuI site. A representative clone with the correct restriction pattern was sequenced by the Bioresource Center at Cornell University.

Protein Crystallization and Cryoprotection

A solution of native CysM−CysO was prepared by mixing separate 15 mg/mL solutions each of CysO and CysM in a 2:1 volumetric ratio. This solution was screened using the hanging drop vapor diffusion method. Individual crystals grew in a range of 7−10% PEG 4000 (w/v %), 0.1 M sodium citrate, pH 5.8, and 0.2 M ammonium acetate at 22 °C. Selenomethionine crystals grew in the same conditions with 5 mM DTT. Crystals were green in color and grew to 150 × 150 × 50 μm3 within 2−4 weeks. The K204 mutant was also screened using the hanging drop method with a 10 mg/mL protein solution. Crystals of the K204A mutant grew to approximately 100 × 40 × 20 μm3 in 2−4 weeks using the hanging drop method in 0.1 M HEPES, pH 7.1, and 0.64 M Li2SO4 at 22 °C. Crystals of CysO were grown using the hanging drop method in the presence of the activating protein MoeZ (Rv3206). MoeZ was purified as described previously (1). A solution of native MoeZ−CysO was prepared by mixing separate 10 mg/mL solutions each of MoeZ and CysO in a 1:1 volumetric ratio. Crystals appeared in 0.2 M NaNO3 and 20% (w/v %) PEG 3350 after approximately 6 months as colorless thick plates with dimensions of 200 × 40 × 40 μm3. Preliminary analysis of the X-ray diffraction data showed that these crystals contained only CysO.

Cryoprotection of the CysM−CysO complex and CysM K204A mutant crystals was carried out through sequential dipping into well solutions with increasing concentrations of ethylene glycol. The cryosolution for the selenomethionine derivative and native CysM−CysO crystals contained 9% PEG 4000, 0.1 M sodium citrate, pH 5.8, 0.2 M ammonium acetate, 1 mM DTT, and either 5% or 25% ethylene glycol by volume. Crystals were first looped out of the mother liquor and then placed in the 5% ethylene glycol solution for approximately 10 s, followed by dipping into the 25% ethylene glycol solution for another 10 s. The crystal was then looped out of the 25% solution and plunged into liquid nitrogen for storage. Cryoprotection of the K204A CysM mutant was also done using sequentially increasing concentrations of ethylene glycol. CysM crystals were first dipped into a solution with 5% ethylene glycol, 0.64 M Li2SO4, and 0.1 M HEPES, pH 7.1, followed by dipping into the same cryosolution with 25% ethylene glycol for approximately 10 s each. Crystals of CysO were cryoprotected by dipping into a solution of 0.2 NaNO3, 20% PEG 3350, and 25% PEG 400 for approximately 10 s before plunging into liquid nitrogen.

X-ray Data Collection

Data for the selenomethionine derivative CysM−CysO crystal were collected at the 24-ID-C beamline at the Advanced Photon Source to 2.1 Å resolution. The energy was calibrated with Se foil, and an X-ray fluorescence scan was done on the CysM−CysO crystal to determine the absorption edge. Images were taken using a Quantum ADSC Q315 detector (Area Detectors Systems Corp.) for 720 frames with 1° oscillations in 10° wedges. Native data for the CysM K204A and CysM−CysO complex crystals were collected at the 8-BM beamline at APS using 1° oscillations for 140° and 300°, respectively, using a Quantum ADSC Q315 detector. Data for the CysO crystals were collected using a Rigaku RTP 300 RC rotating copper anode generator operating at 50 kV and 100 mA. A Rigaku RAXIS IV++ image plate detector was used for image detection. Data collection was done in 1° oscillations for a total of 215°. Data collection statistics for all data sets are summarized in Table 1. Integration and scaling of all data was done using the HKL2000 suite of programs (21).

Table 1. Data Collection Statistics.

| sample | SeMet CysOM | native CysOMa | K204A CysM | native CysO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| source | APS 24-ID-C | APS 8-BM | APS 8-BM | home |

| wavelength (Å) | 0.97950 | 0.97949 | 0.94980 | 1.54178 |

| resolution (Å) | 2.10 | 1.53 | 2.80 | 2.70 |

| space group | P21 | P21 | P212121 | C2 |

| unit cell parameters | ||||

| a (Å) | 56.2 | 55.8 | 72.4 | 87.9 |

| b (Å) | 80.6 | 80.4 | 85.4 | 62.9 |

| c (Å) | 91.5 | 89.6 | 98.9 | 36.5 |

| β (deg) | 106.8 | 105.8 | 90 | 114.6 |

| no. of reflections | 650381 | 334177 | 875722 | 20088 |

| no. of unique reflections | 45147 | 110648 | 15513 | 5022 |

| redundancy | 14.4 (12.0) | 3.0 (2.5) | 5.5 (5.3) | 4.0 (3.0) |

| completeness | 98.9 (92.5) | 96.3 (81.6) | 99.6 (96.2) | 99.2 (95.4) |

| Rsymb (%) | 7.8 (30.9) | 4.6 (21.9) | 8.0 (24.7) | 14.5 (39.2) |

| I/σ(I) | 40.1 (6.6) | 26.2 (4.0) | 18.6 (4.1) | 14.5 (3.5) |

Merged with low-resolution data from the SeMet crystal.

Rsym = ∑∑i|Ii − ⟨I⟩|/∑⟨I⟩, where ⟨I⟩ is the mean intensity of the N reflections with intensities Ii and common indices hkl.

Structure Determination and Refinement

Selenium sites in the selenomethionine derivative CysM−CysO crystal were found using SOLVE (22), with 11 of the 14 possible selenium peaks located. Density modification (23) and automated model building (24) were done using RESOLVE. The remainder of the model was built using the graphics programs O (25) and Coot (26). Refinement was carried out using the CCP4 (27) and CNS (28) suite of programs. The selenomethionine derivative structure was then refined against the higher resolution native CysM−CysO data. The native CysM−CysO data set had low completeness in the resolution range of 6 Å and below due to intensity overloads. To account for this, the native CysM−CysO data set was merged with data corresponding to a resolution of 6 Å and below from the selenomethionine derivative crystal in Scalepack (21) for refinement and map calculations. In the final stages of refinement, the high-resolution data alone were used to refine the model. All residues in all three molecules were modeled into the electron density with the exception of the N-terminal methionine residue of CysO and residues 126−129 in the CysM chain that does not interact with CysO (CysMB). Six residues were modeled in alternate conformations: Leu169 from the CysM molecule that interacts with CysO (CysMA), Cys99, Met190, Thr257, and Leu270 from CysMB, and Thr9 from CysO.

The structure of CysMA was used as an initial model to refine against the K204A CysM data. Residues 212−226 and 315−323 from chain A and 313−326 from chain B were not modeled due to disorder in the electron density maps. The refined structure of CysO from the CysM−CysO complex was used as an initial model to refine the CysO only data. All but residues 91−93 were built into the model. The final refinement statistics for all data sets and the geometries and distances of all final models as evaluated by PROCHECK (29) are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Refinement Statistics.

| sample | SeMet CysOM | native CysOM | K204A CysM | native CysO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| no. of non-H atoms | 5529 | 6512 | 4648 | 1290 |

| no. of protein atoms | 5150 | 5454 | 4443 | 1266 |

| no. of water atoms | 349 | 1028 | 160 | 24 |

| no. of ligand atoms | 30 | 30 | 45 | 0 |

| Rworking (%)a | 19.2 | 17.6 | 19.0 | 19.5 |

| Rfree (%)b | 24.3 | 21.7 | 25.6 | 25.2 |

| Ramachandran plot | ||||

| most favored region (%) | 89.7 | 91.7 | 89.4 | 89.0 |

| additionally allowed regions (%) | 7.5 | 7.9 | 8.6 | 11.0 |

| generously allowed region (%) | 1.9 | 0.3 | 1.6 | 0.0 |

| disallowed region (%) | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.0 |

| rms deviations from ideal | ||||

| bonds (Å) | 0.021 | 0.026 | 0.021 | 0.019 |

| angles (deg) | 2.0 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

Rworking = Σ||Fo| − K|Fc||/Σhkl|Fo|, where Fo and Fc are the observed and calculated structure factors, respectively.

Rfree was calculated using 5% of all reflections that were excluded at all stages of refinement.

Molecular Modeling of Intermediates

The program MacroModel, version 9.1 (30,31) was used to model both the O-acetylserine (OAS)−PLP adduct 3, the α-aminoacrylate intermediate 5, and intermediate 6. All water molecules were removed from the structure, and the C-terminus of CysO was converted to a thiocarboxylate and manually adjusted to point toward the active site. Hydrogen atoms were added where appropriate. The initial position of each intermediate was approximated by overlaying the structure of Oacetylserine sulfhydrylase from Salmonella typhimurium containing an external aldimine linkage to methionine (32) with CysM and superimposing their respective aldimine Cα and carboxylate atoms. Modeling was carried out using a 20 Å shell surrounding the OAS moiety of the adduct, with residues within a 6 Å shell allowed to move and the remaining residues frozen. Some of the key residues in the conformational search included 91-AGG-93 from CysO and 184-GTTGT-188, Lys51, Ser265, and 322-WA-323 from CysM. Torsional rotation was allowed between all atoms within the PLP−OAS adduct connected by a single bond in the conformational search parameters. Modeling was done using the AMBER* force field (33,34) and a distance-dependent electrostatic treatment with a dielectic constant of 4.0. The TNCG minimization method was used for the energy minimization of structures generated by conformational search (35). Conformational searching with the αaminoacrylate intermediate was done in the same way. The final models were manually adjusted to optimize the expected reaction geometry.

Figure Preparation

All figures of protein molecules and residues were generated in PyMOL (36).

Results

CysM Structure

The CysM molecule is composed of eight α-helices, five 310-helices, and nine β-strands (Figure 2A,B). The protomer has a large and a small domain, each with an αβα sandwich fold. The large domain has a mixed β-sheet with β1↑β2↓β9↓β6↓β7↓β8↓ topology, while the smaller domain consists of a three-stranded parallel β-sheet comprised of strands β3, β4, and β5. This topology is consistent with other β-elimination enzymes (37). The interface between CysM molecules consists of loop regions with 60% of the residues being hydrophobic at the dimer interface. Other interactions include a salt bridge between Arg3 and Glu175 and a series of hydrogen-bonding pairs that are listed in Table 3.

Figure 2.

Structures of CysM and CysO. (A) CysM ribbon diagram. (B) CysM topology. (C) CysO ribbon diagram. (D) CysO topology diagram. (E) Ribbon diagram of the CysM−CysO complex. CysM bound to CysO (CysMA) is color coded with red helices, yellow strands, and green loops. CysO and CysM not bound to CysO (CysMB) are color coded with cyan helices, magenta strands, and salmon loops.

Table 3. Dimeric Interactions.

| A chain | B chain | H-bond atoms |

|---|---|---|

| Thr2 | Asp172 | OH−Oδ |

| Tyr4 | Leu16 | NH−O |

| Tyr4 | Gly18 | O−NH |

| Asp5 | Gln20 | O−NHϵ |

| Leu92 | Arg21 | O−NH1 |

| Gln111 | Leu301 | NHϵ−O |

| Leu115 | His256 | O−NHϵ |

| Tyr116 | Gly259 | OH−O |

| Asp172 | Arg3 | O−NH1 |

| Glu175 | Arg3 | Oϵ−NH1 |

| His256 | Arg91 | O−Nϵ |

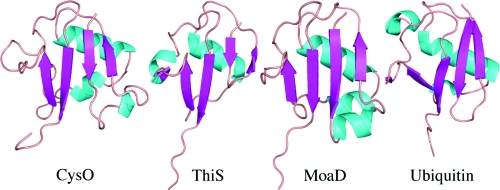

CysO Structure

The CysO monomer is 93 residues in length and 9.6 kDa in mass. The secondary structure consists of two 310 helices, a mixed four-stranded β-sheet with a β3↑β4↓β1↓β2↑ topology, and one α-helix inserted between β2 and β3 (Figure 2C,D). This topology describes the β-grasp fold that is seen in the sulfur carrier proteins ThiS (15) and MoaD (17) as well as ubiquitin (38).

CysM−CysO Complex

The asymmetric CysM−CysO complex consists of a CysM dimer with a CysO molecule bound to one end (CysMA denotes the protomer interacting with CysO, and CysMB denotes the unbound protomer) (Figure 2E). It is unclear whether or not the asymmetric complex is an artifact of crystallization. Native analytical gel analysis was inconclusive, and attempts to purify the complex suggest that CysO is weakly bound to CysM (unpublished data). The CysMA and CysMB protomers show two main differences. First, the loop region spanning residues 211−237 in CysMA contains three 310-helices and extends away from the core of the structure to accommodate CysO binding. CysMB adopts a more compact structure with an α-helix spanning residues 217−222 and a single 310-helix spanning residues 228−231. Second, the smaller domain comprising strands β3, β4, and β5 and helix α4 is shifted away from the core of the complex structure. Only the conformation of the CysO binding loop in CysMA allows for hydrogen bonds to form between the region connecting β5 and α4 in the smaller domain. The hydrogen bonds that contribute to this shift in CysMA are between the carboxylic acid side chain from Glu126 and the carbonyl oxygen atom of Ala218 and between the amide nitrogen atom of Gly217 and the carbonyl oxygen atom of Val216.

The comparison between CysO molecules from the complex structure and the CysO alone structure shows that the overall structure remains the same, with a root-mean-square deviation (rmsd) between 89 Cα carbon atoms of 0.5 Å. One main difference is that the C-terminus of CysO in the complex is well ordered through several hydrogen bonds with CysM. The absence of CysM binding leads to disorder in the final three residues of CysO alone, which were not modeled into the structure. Twenty-five percent of the accessible surface of CysO is buried in the complex as calculated by the protein−protein interaction server (39). Key hydrogen bonds between CysO and CysM are listed in Table 4. The side chain oxygen atom of Asp65CysO is hydrogen bonded to His271A through a bridging water molecule (subscripts CysO and A refer to CysO and CysMA, respectively). A bridging water molecule is found donating hydrogen bonds to the carbonyl oxygen atoms of both Gly92CysO and Leu183A, and two bridging water molecules form a hydrogen-bonding network connecting the carbonyl oxygen atoms of Val90CysO and Phe226A. Two salt bridges also occur at the protein−protein interface between Arg12CysO and Glu214A and between Asp65CysO and Arg211A.

Table 4. CysM−CysO Hydrogen Bonds.

| CysM | CysO | H-bond atoms |

|---|---|---|

| Asn130 | Ala89 | NHδ−O |

| Asn130 | Ala91 | Oϵ−HN |

| Glu209 | Tyr62 | Oϵ−HO |

| Tyr217 | Gly93 | OH−O |

| Phe226 | Ala89 | NH−O |

| Arg239 | Asp67 | O−HN |

| Ser241 | Asp65 | OH−Oδ |

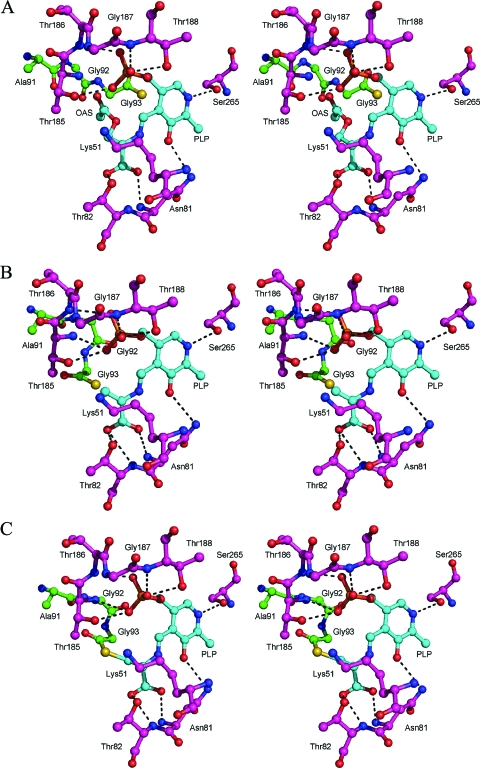

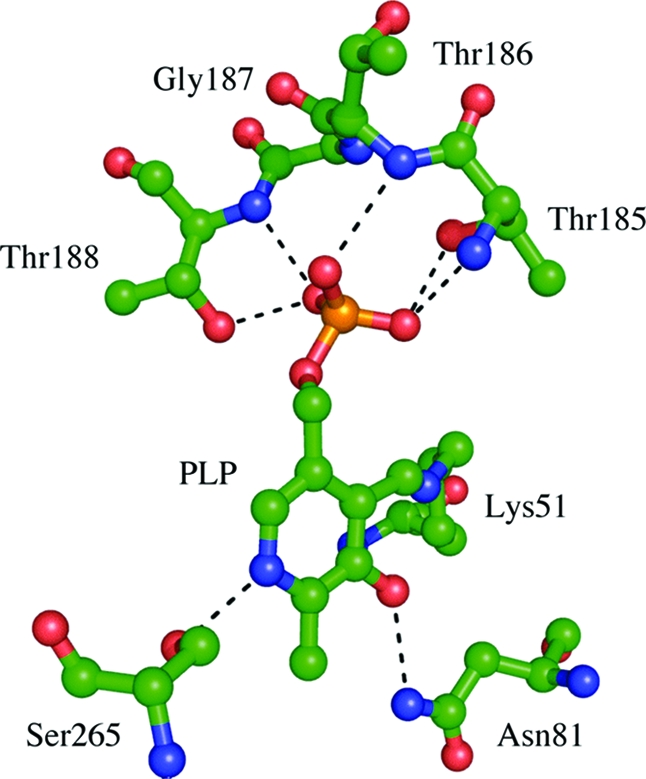

Active Site

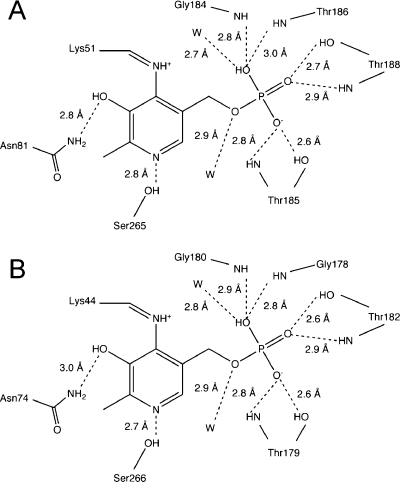

A PLP cofactor is found in each protomer of CysM covalently attached to Lys51 through a Schiff base linkage. Figure 3 illustrates key interactions between CysM and PLP. A glycine- and threonine-rich sequence binds the phosphate group and is characteristic of PLP binding proteins (40). A large area of open space occupied only by water molecules spans the distance between Gly93 of CysO and the PLP molecule. The distance from the Schiff base forming carbon atom of PLP to the closest C-terminal oxygen atom of CysO is 11.3 Å.

Figure 3.

CysM active site with PLP coordinating residues labeled with green carbon atoms.

Discussion

CysM and Structural Homologues

Structural homologues were identified using the DALI server (www.ebi.ac.uk/dali), and the top hits were selected for comparison (Table 5). The closest structural homologues are β-elimination enzymes, which use OAS or phosphoserine as a substrate to make cysteine. CysK, the sulfide-dependent cysteine synthase, has rmsd values of 2.4 Å for 281 Cα carbon atoms from CysMA and 1.8 Å for 278 Cα carbon atoms from CysMB. S. typhimuriumO-acetylserine sulfhydrylase (OASS) has rmsd values of 2.5 Å for 287 Cα carbon atoms from CysMA and 1.9 Å for 283 Cα carbon atoms from CysMB. The conformation of the CysO binding loop of CysM is the most significant difference between the structural homologues, which do not bind a sulfur carrier protein. The conformation of the binding loop in CysMB is more similar to the structural homologues than in CysMA, which results in the lower rmsd values. Another structural difference is that the C-terminal tail of CysM encompassing residues 300−323 contains two 310-helices and points directly into the active site. Both the CysK and OASS structures lack this N-terminal extension.

Table 5. CysM Structural Homologues.

| PDB code | Z-score | aligned Cα atoms | rmsd | annotation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2Q3B | 34.8 | 281 | 2.4 | cysteine synthase |

| 1OAS | 34.2 | 287 | 2.5 | O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase |

| 1WKV | 32.7 | 278 | 2.0 | O-phosphoserine sulfhydrylase |

| 2TYS | 27.9 | 274 | 2.7 | tryptophan synthase |

| 1TDJ | 25.9 | 271 | 2.9 | threonine deaminase |

| 1V71 | 24.7 | 267 | 3.2 | serine racemase |

| 1PWE | 23.9 | 264 | 3.4 | serine dehydratase |

| 1F2D | 22.9 | 262 | 2.7 | 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate deaminase |

| 1E5X | 21.7 | 269 | 3.6 | threonine synthase |

| 1KL7 | 20.7 | 269 | 3.5 | threonine synthase |

CysM and CysK Active Sites

The PLP binding geometries of CysM and CysK are very similar (Figure 4). The final two residues of CysM, Trp322 and Ala323, point toward the active site of the protein. A π-stacking interaction between Trp322 and Tyr212 helps to position the C-terminus. Residues 218−222, rather than the C-terminus, occupy this region in CysK. These residues correspond to the CysO binding loop of CysM based on sequence alignment. Additionally, there is a molecule of 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol in CysK corresponding to the region of CysM spanning the C-terminus of CysO and the PLP cofactor. The C-terminus of the CysM K204A mutant also does not point to the active site. However, the CysO binding loop of one of the K204A protomers is seen ordered and has the same conformation as the corresponding residues in CysK.

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of CysM (A) and CysK (B) binding interactions with the PLP cofactor.

CysO and Structural Homologues

Structural homologues were identified using the DALI server and selecting the top hits for comparison (Table 6). The β-grasp proteins complexed with a binding partner were also used for comparison. This included ThiS, MoaD, and ubiquitin, which were compared to CysO through structural superposition. Each possesses the same topology, with most structural differences found in loop regions rather than secondary structural elements (Figure 5). CysO has insertions spanning residues 7−19 and 48−55, which are absent in the homologues. The exception is MoaD, which aligns well with residues 7−19 in CysO. Both CysO and MoaD form a key binding interaction with their respective binding partner in this region. The rmsd values between Cα positions in CysO are 2.6 Å for ThiS for 58 Cα carbon atoms, 2.8 Å for MoaD for 77 Cα carbon atoms, and 2.6 Å for ubiquitin for 62 Cα carbon atoms.

Table 6. CysO Structural Homologues.

| PDB code | Z-score | aligned Cα atoms | rmsd | annotation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1V8C | 14.9 | 86 | 1.8 | Thermus thermophilus MoaD |

| 1FMA | 9.5 | 78 | 2.3 | MoaD from MoaE−MoaD complex |

| 1JW9 | 8.9 | 77 | 2.8 | MoaD from MoeB−MoaD complex |

| 2GLE | 8.9 | 82 | 2.9 | neurabin SAM domain |

| 1XO3 | 8.1 | 80 | 2.9 | Mus musculus Urm1 |

| 2BB5 | 7.9 | 78 | 2.6 | transcobalamin II |

| 1C1Y | 5.4 | 63 | 2.5 | Ras-binding domain of c-Raf1 |

| 1ZUD | 5.1 | 58 | 2.6 | ThiS from ThiF−ThiS complex |

| 1TYG | 4.7 | 59 | 3.2 | ThiS from ThiG−ThiS complex |

| 1ZGU | 4.4 | 62 | 2.6 | ubiquitin from MMS2−Ub complex |

Figure 5.

Ribbon diagrams of all structurally characterized sulfur carrier proteins and ubiquitin.

CysM−CysO Interactions and Conserved Residues

The features required for interactions with CysO come from three main sections of the CysM molecule. First is the CysO binding loop encompassing residues 211−237, which contributes the majority of CysO binding interactions. Second is helix α4, which is part of the smaller domain of the CysM molecule. Asn130 from this helix forms one of the key hydrogen bonds that stabilize the C-terminal region of CysO. Third, strand β8 forms hydrogen bonds with the loop that proceeds from the β3 strand of CysO.

In order to determine key CysM residues, sequence alignments were performed using both homologues that utilize sulfur carrier proteins and ones that incorporate sulfur directly from sulfide. Residues Asn81 and Ser265 that bind the PLP cofactor are exclusively conserved in both types. The glycine- and threonine-rich sequence that binds the phosphate group of the cofactor varies slightly in the position of glycine and threonine or serine residues, but overall the motif is conserved. A sequence alignment of 200 nonredundant CysM sequences shows that none of the residues on the CysM surface involved with CysO binding are conserved. When the alignment is restricted to the organisms Mycobacterium vanbaalenii, Mycobacterium smegmatis, Mycobacterium ulcerans, and Mycobacterium flavescens, all of which have both CysO and CysM genes, the CysO binding residues are exclusively conserved. Conservation of the CysM−CysO binding interface is maintained within the Mycobacterium genus but shows greater variation, especially in CysM, for other species.

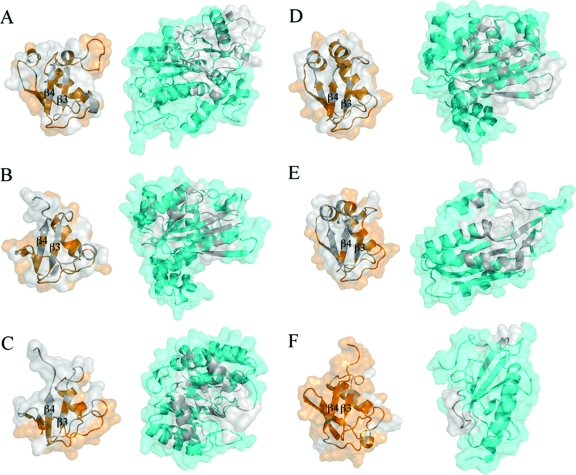

Comparison of the CysM−CysO Interface with Other β-Grasp Protein Complexes

In order to determine if regions of CysM and CysO involved in protein−protein interactions are similar to other β-grasp protein complexes, the structures ThiF−ThiS (15) ThiG−ThiS (16), MoeB−MoaD (17), MoaE−MoaD (10), and ubiquitin in complex with the E2-like protein MMS2 (41) were compared in Figure 6. Table 7 lists several properties of the sulfur carrier proteins and ubiquitin at the protein−protein interface. The percent of hydrophobic residues at the interface ranges from 61% to 72% for the sulfur carrier protein examples, while the ubiquitin−MMS2 structure falls below this range at 58%. The number of hydrogen bonds between sulfur carrier proteins and their binding partners ranges from 9 to 11, but the ubiquitin−MMS2 structure has only 5. This is due to ubiquitin having much less of its accessible surface area in close contact with its binding partner. In the sulfur carrier protein examples, 20−25% of the accessible surface area is in close contact with each binding partner. In ubiquitin, only 13% of the surface makes up the binding interface with MMS2.

Figure 6.

Ribbon and surface interface diagrams of CysO homologues in complexes with their binding partners. (A) ThiF−ThiS complex. (B) ThiG−ThiS complex. (C) MoeB−MoaD complex. (D) MoaE−MoaD complex. (E) Ubiquitin−MMS2 complex. (F) CysM−CysO complex. The sulfur carrier proteins are colored orange, and their respective binding partners are colored light blue. The silver colored regions in each pair indicate the binding interface. Strands β3 and β4 are labeled for each sulfur carrier protein, which are all in the same orientation. The comparison shows the diversity of binding partners that interact with the sulfur carrier protein fold.

Table 7. Protein−Protein Interface Comparisons.

| protein interface parameter | CysO−CysM | ThiS−ThiF | ThiS−ThiG | MoaD−MoaB | MoaD−MoaE | Ub−MMS2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| interface accessible surface area (Å2) | 1213.6 | 1045.9 | 1194.2 | 1113.2 | 985.1 | 632.4 |

| % interface accessible surface area | 24.6 | 22.7 | 24.2 | 23.5 | 19.7 | 13.4 |

| % polar atoms in interface | 35.1 | 38.2 | 28.2 | 35.4 | 39.3 | 42.2 |

| % nonpolar atoms in interface | 64.8 | 61.7 | 71.7 | 64.6 | 60.6 | 57.8 |

| hydrogen bonds | 11 | 14 | 11 | 9 | 13 | 5 |

| salt bridges | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

Structural alignments were made by superimposing each sulfur carrier protein or ubiquitin complex using only CysO as the template. No structural similarities between CysM, ThiG, MoaE, or MMS2 are observed. However, two β-strands common to CysM, ThiF, and MoeB align when each sulfur carrier protein is overlaid. The strands β7 and β8 in CysM align with strands β6 and β7 in ThiF and MoeB despite the fact that CysM has a different fold. The regions in the sulfur carrier proteins and ubiquitin that make up most of the binding interface come from strands β3 and β4 and the residues following β4 to the C-terminus. The ubiquitin complex structure has the smallest interface with only residue 42 from strand β3 and residue 68 from β4 contributing to hydrogen bonds at the interface.

Mechanistic Implications

A mechanistic proposal for the CysO−CysM-catalyzed reaction, based on the extensive mechanistic characterization of the sulfide-dependent cysteine synthase (42), is outlined in Scheme 1. In this proposal, O-acetylserine forms an imine with PLP which then undergoes a deprotonation to give 4. Acetate elimination followed by thiocarboxylate addition to the resulting aminoacrylate gives 6. The reaction is completed by a tautomerization to 7 followed by a transimination reaction to give thioester 8, which then undergoes an N/S acyl shift to give cysteinyl-CysO 9.

Scheme 1.

Molecular modeling simulations using conformational searching followed by molecular mechanics based energy minimization, followed by manual optimization, were carried out using MacroModel for both the PLP−OAS adduct 3 and the α-aminoacrylate intermediate 5 in the active site. In the PLP−OAS model (Figure 7A), the carboxylate moiety of OAS accepts a hydrogen bond from the backbone nitrogen atom of Asn81. One oxygen atom of the acetate moiety accepts a hydrogen bond from the hydroxyl group of Tyr212 while the other accepts a hydrogen bond from the amide nitrogen atom of Ala323. In the α-aminoacrylate model (Figure 7B), the carboxylate moiety accepts hydrogen bonds from the hydroxyl group of Tyr212 and the amide nitrogen atom of Ala323. The conformation of the C-terminus of CysO shows the sulfur atom at a distance of 3.7 Å from the β-carbon α-aminoacrylate intermediate 5. Using the aminoacrylate as a starting point, a model for the subsequent intermediate 6 in which the carbon−sulfur bond has formed was generated (Figure 7C).

Figure 7.

Stereoviews of the active site models. (A) The PLP−OAS adduct 3. (B) α-Aminoacrylate intermediate 5. (C) Intermediate 6 in which the C−S bond has formed. CysM residues are labeled with magenta carbon atoms, CysO residues are labeled with green carbon atoms and PLP and OAS or aminoacrylate moieties with cyan carbon atoms.

The structural and modeling studies are consistent with the mechanistic proposal in Scheme 1. PLP is bound at the active site via an imine with Lys51. The model of the enzyme O-acetylserine (OAS) complex (Figure 7A) shows Lys51 displaced by the amino group of OAS and that Lys51 could serve as the base involved in the Cα deprotonation. The resulting carbanion is stabilized by delocalization into the PLP cofactor as well as by delocalization into the OAS carboxylate which forms multiple hydrogen-bonding interactions with the enzyme (backbone amides of Asn81 and Thr82, OH of Thr82). The acetate of OAS is reasonably positioned for departure, after planarization of Cα following deprotonation, with the scissile C−O bond perpendicular to the plane of the delocalized π system. This suggests an E1cB mechanism rather than an E2 mechanism for this elimination reaction, which occurs with trans stereochemistry. Acetate is also activated as a leaving group by hydrogen bonding of its carbonyl oxygen to the amide NH of threonine 185 (nonoptimal orientation in the model because Cα is not yet planarized). The thiocarboxylate sulfur is located 5.21 Å from the carbon to which it will add. This large separation suggests that, after acetate departs, the thiocarboxylate group of CysO occupies the acetate binding site and that thiocarboxylate addition is the microscopic reverse of acetate departure. This predicts that the Cβ substitution reaction is occurring with overall retention of stereochemistry.

The model of the aminoacrylate intermediate (Figure 7B) shows the thiocarboxylate in position to add to the Cβ of the aminoacrylate (Cβ−S distance = 2.48 Å). The thiocarboxylate occupies the acetate binding site but is not hydrogen bonded to the amide NH of Thr185. This model also predicts that the Cα carbanion, generated after thiocarboxylate addition, is stabilized by delocalization into the cofactor as well as by delocalization into the Cβ carboxylate, which forms hydrogen bonds with the amide NH and the side chain OH of Thr82 and with the backbone nitrogen atom of Asn81. Lys51 is reasonably positioned to protonate this carbanion (Cα−N distance = 4.08 Å).

In the enzyme thioester model (Figure 7C), Lys51 is reasonably positioned to mediate the transimination required for product release. There are no hydrogen-bonding interactions to the thioester carbonyl group whose carbon is held 4.89 Å from the cysteinyl amino group. This suggests that the final N/S acyl shift is not enzyme catalyzed and occurs after dissociation of the thioester from CysM.

Conclusions

The structure of CysM−CysO is an example of a β-elimination enzyme in complex with a sulfur carrier protein used to generate the amino acid cysteine. CysM is able to bind CysO using a binding loop that is ordered differently in structural comparators and when CysO is unbound. The binding loop contains residues that are only conserved among other species within the Mycobacterium genus that also utilize a sulfur carrier protein for cysteine biosynthesis. The overall fold of CysO is similar to that of other sulfur carrier proteins and ubiquitin. Two β-strands at the interface of CysO and CysM are structurally aligned when compared to the E1-like adenyltransferase proteins ThiF and MoaD. Modeling studies show that the C-terminus of CysO is able to reach the β-carbon of the α-aminoacrylate intermediate in a conformation favorable for nucleophilic addition and that cysteine formation proceeds by a mechanism that is similar to that used by the sulfide-dependent cysteine synthase.

Acknowledgments

We thank Leslie Kinsland for help in the preparation of the manuscript and Dr. Igor Kourinov and the rest of the NE-CAT staff at the APS beamlines 24-ID-C and 8-BM for receiving crystal samples and collecting several CysM−CysO data sets. We thank Drs. Angela Toms and Erika Soriano for collecting the native CysM−CysO and K204A CysM mutant data sets.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Footnotes

Abbreviations: PLP, pyridoxal 5′-phosphate; DTT, 1,4-dithiothreitol; rmsd, root-mean-square deviation; OAS, O-acetylserine; OASS, O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase.

References

- Burns K. E.; Baumgart S.; Dorrestein P. C.; Zhai H.; McLafferty F. W.; Begley T. P. (2005) Reconstitution of a new cysteine biosynthetic pathway in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 11602–11603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusner D. J. (2005) Mechanisms of mycobacterial persistence in tuberculosis. Clin. Immunol. 114, 239–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z.; Kelley C.; Collins F.; Rouse D.; Morris S. (1998) Expression of katG in Mycobacterium tuberculosis is associated with its growth and persistence in mice and guinea pigs. J. Infect. Dis. 177, 1030–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell D. G. (2003) Phagosomes, fatty acids and tuberculosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 5, 776–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vachula M.; Holzer T. J.; Andersen B. R. (1989) Suppression of monocyte oxidative response by phenolic glycolipid I of Mycobacterium leprae. J. Immunol. 142, 1696–1701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergne I.; Chua J.; Singh S. B.; Deretic V. (2004) Cell biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis phagosome. Annu. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 20, 367–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manganelli R.; Voskuil M. I.; Schoolnik G. K.; Dubnau E.; Gomez M.; Smith I. (2002) Role of the extracytoplasmic-function sigma factor sigma(H) in Mycobacterium tuberculosis global gene expression. Mol. Microbiol. 45, 365–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijay-Kumar S.; Bugg C. E.; Wilkinson K. D.; Cook W. J. (1985) Three-dimensional structure of ubiquitin at 2.8 Å resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 82, 3582–3585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S. V.; Kelleher N. L.; Kinsland C.; Chiu H. J.; Costello C. A.; Backstrom A. D.; McLafferty F. W.; Begley T. P. (1998) Thiamin biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. Identification of this thiocarboxylate as the immediate sulfur donor in the thiazole formation. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 16555–16560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph M. J.; Wuebbens M. M.; Rajagopalan K. V.; Schindelin H. (2001) Crystal structure of molybdopterin synthase and its evolutionary relationship to ubiquitin activation. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8, 42–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godert A. M.; Jin M.; McLafferty F. W.; Begley T. P. (2007) Biosynthesis of the thioquinolobactin siderophore: an interesting variation on sulfur transfer. J. Bacteriol. 189, 2941–2944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi J.; Ge Y.; Kinsland C.; McLafferty F. W.; Begley T. P. (2001) Biosynthesis of the thiazole moiety of thiamin in Escherichia coli: identification of an acyldisulfide-linked protein-protein conjugate that is functionally analogous to the ubiquitin/E1 complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 8513–8518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begley T. P.; Downs D. M.; Ealick S. E.; McLafferty F. W.; Van Loon A. P.; Taylor S.; Campobasso N.; Chiu H. J.; Kinsland C.; Reddick J. J.; Xi J. (1999) Thiamin biosynthesis in prokaryotes. Arch. Microbiol. 171, 293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leimkuhler S.; Wuebbens M. M.; Rajagopalan K. V. (2001) Characterization of Escherichia coli MoeB and its involvement in the activation of molybdopterin synthase for the biosynthesis of the molybdenum cofactor. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 34695–34701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann C.; Begley T. P.; Ealick S. E. (2006) Structure of the Escherichia coli ThiS-ThiF complex, a key component of the sulfur transfer system in thiamin biosynthesis. Biochemistry 45, 11–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settembre E. C.; Dorrestein P. C.; Zhai H.; Chatterjee A.; McLafferty F. W.; Begley T. P.; Ealick S. E. (2004) Thiamin biosynthesis in Bacillus subtilis: structure of the thiazole synthase/sulfur carrier protein complex. Biochemistry 43, 11647–11657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lake M. W.; Wuebbens M. M.; Rajagopalan K. V.; Schindelin H. (2001) Mechanism of ubiquitin activation revealed by the structure of a bacterial MoeB-MoaD complex. Nature 414, 325–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godert A. M.; Jin M.; McLafferty F. W.; Begley T. P. (2007) Biosynthesis of the thioquinolobactin siderophore: an interesting variation on sulfur transfer. J. Bacteriol. 189, 2941–2944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford M. M. (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derewenda Z. S. (2004) Rational protein crystallization by mutational surface engineering. Structure 12, 529–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z.; Minor W. (1997) Processing of x-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwilliger T. C.; Berendzen J. (1999) Automated structure solution for MIR and MAD. Acta Crystallogr. D 55, 849–861(http://www.solve.lanl.gov). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwilliger T. C. (2000) Maximum likelihood density modification. Acta Crystallogr. D 56, 965–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwilliger T. C. (2003) Automated main-chain model building by template matching and iterative fragment extension. Acta Crystallogr. D 59, 38–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones T. A.; Zou J.-Y.; Cowan S. W.; Kjeldgaard M. (1991) Improved methods for the building of protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr. A 47, 110–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P.; Cowtan K. (2004) Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D 60, 2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collaborative Computational Project-Number 4 (1994) The CCP-4 suite: programs for protein crystallography, Acta Crystallogr. D. 50, 760−763. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Brünger A. T.; Adams P. D.; Clore G. M.; DeLano W. L.; Gros P.; Grosse-Kunstleve R. W.; Jiang J. S.; Kuszewski J.; Nilges M.; Pannu N. S.; Read R. J.; Rice L. M.; Simonson T.; Warren G. L. (1998) Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D 54, 905–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski R. A.; MacArthur M. W.; Moss D. S.; Thornton J. M. (1993) PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26, 283–291. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamadi F.; Richards N. G. J.; Guida W. C.; Liskamp R.; Lipton M.; Caufield C.; Chang G.; Hendrickson T.; Still W. C. (1990) MacroModel—An Integrated Software System for Modeling Organic and Bioorganic Molecules Using Molecular Mechanics. J. Comput. Chem. 11, 460–467. [Google Scholar]

- MacroModel, v. (2005) Schrodinger, LLC, New York, NY.

- Burkhard P.; Tai C. H.; Ristroph C. M.; Cook P. F.; Jansonius J. N. (1999) Ligand binding induces a large conformational change in O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase from Salmonella typhimurium. J. Mol. Biol. 291, 941–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner S. J.; Kollman P. A.; Case D. A.; Singh U. C.; Ghio C.; Alagona G.; Profeta S. Jr.; Weiner P. (1984) A new force field for molecular mechanical simulation of nucleic acids and proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 106, 765–784. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner S. J.; Kollman P. A.; Nguyen D. T.; Case D. A. (1986) An all atom force field for simulations of proteins and nucleic acids. J. Comput. Chem. 7, 230–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponder J. W.; Richards F. M. (1987) An efficient Newton-like method for molecular mechanics energy minimization of large molecules. J. Comput. Chem. 8, 1016–1024. [Google Scholar]

- DeLano W. L. (2002) The PyMOL User’s Manual.

- Burkhard P.; Rao G. S.; Hohenester E.; Schnackerz K. D.; Cook P. F.; Jansonius J. N. (1998) Three-dimensional structure of O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase from Salmonella typhimurium. J. Mol. Biol. 283, 121–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijay-Kumar S.; Bugg C. E.; Wilkinson K. D.; Cook W. J. (1985) Three-dimensional structure of ubiquitin at 2.8 Å resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 82, 3582–3585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S.; Thornton J. M. (1995) Protein-protein interactions: a review of protein dimer structures. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 63, 31–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momany C.; Ghosh R.; Hackert M. L. (1995) Structural motifs for pyridoxal-5′-phosphate binding in decarboxylases: an analysis based on the crystal structure of the Lactobacillus 30a ornithine decarboxylase. Protein Sci. 4, 849–854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M. J.; Saltibus L. F.; Hau D. D.; Xiao W.; Spyracopoulos L. (2006) Structural basis for non-covalent interaction between ubiquitin and the ubiquitin conjugating enzyme variant human MMS2. J. Biomol. NMR 34, 89–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai C. H.; Cook P. F. (2001) Pyridoxal 5′-phosphate-dependent alpha,beta-elimination reactions: mechanism of O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase. Acc. Chem. Res. 34, 49–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]