Abstract

IMP dehydrogenase (IMPDH) catalyzes two very different chemical transformations, a dehydrogenase reaction and a hydrolysis reaction. The enzyme toggles between the open conformation required for the dehydrogenase reaction and the closed conformation of the hydrolase reaction by moving a mobile flap into the NAD site. Despite these multiple functional constraints, the residues of the flap and NAD site are highly diverged, and the equilibrium between open and closed conformations (Kc) varies widely. In order to understand how differences in the dynamic properties of the flap influence the catalytic cycle, we have delineated the kinetic mechanism of IMPDH from the pathogenic protozoan parasite Cryptosporidium parvum (CpIMPDH), which was obtained from a bacterial source through horizontal gene transfer, and its host counterpart, human IMPDH type 2 (hIMPDH2). Interestingly, the intrinsic binding energy of NAD+ differentially distributes across the dinucleotide binding sites of these two enzymes as well as in the previously characterized IMPDH from Tritrichomonas foetus (TfIMPDH). Both the dehydrogenase and hydrolase reactions display significant differences in the host and parasite enzymes, in keeping with the phylogenetic and structural divergence of their active sites. Despite large differences in Kc, the catalytic power of both the dehydrogenase and hydrolase conformations are similar in CpIMPDH and TfIMPDH. This observation suggests that the closure of the flap simply sets the stage for catalysis rather than plays a more active role in the chemical transformation. This work provides the essential mechanistic framework for drug discovery.

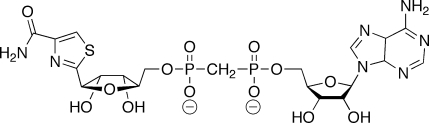

Inosine-5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH)1 catalyzes the penultimate step in guanine nucleotide biosynthesis, the NAD+-dependent conversion of inosine-5′-monophosphate (IMP) to xanthosine-5′-monophosphate (XMP). This reaction controls the size of the guanine nucleotide pool, which in turn controls proliferation (1). IMPDH inhibitors are used as immunosuppressive, anticancer, and antiviral agents (2,3). Recently, IMPDH has emerged as an attractive target for drugs against Cryptosporidium parvum, the intracellular eukaryotic parasite that is a major cause of diarrhea and malnutrition in the developing world and a serious pathogen of AIDS and other immunosuppressed patients in the industrialized world (4–6). The purine salvage pathway of C. parvum relies solely on adenosine; guanine nucleotides are produced by the consecutive actions of adenosine kinase, AMP deaminase, IMPDH, and GMP synthase (7–9). CpIMPDH appears to have been obtained from epsilon proteobacteria via horizontal gene transfer and thus is highly diverged from the human counterparts hIMPDH1 and hIMPDH2 (7,10,11). This situation contrasts with other Apicomplexan parasites such as Plasmodium and Toxoplasma, which have more complex purine salvage pathways and contain eukaryotic IMPDHs similar to the human enzymes (12). Presumably, the bacterial CpIMPDH confers an evolutionary advantage uniquely suited to the metabolic demands of Cryptosporidium.

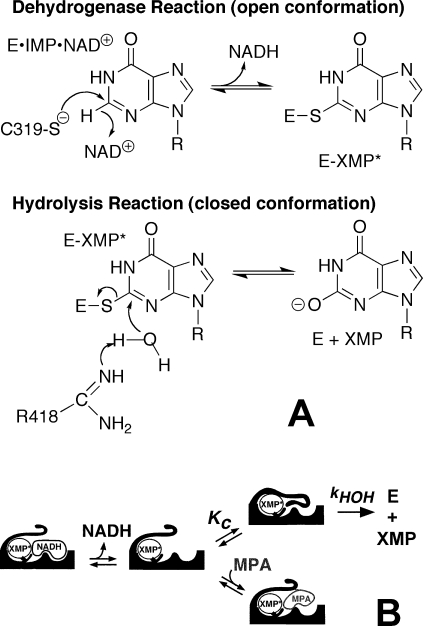

The IMPDH reaction requires two different chemical transformations, a redox step where Cys319 attacks IMP producing NADH and the covalent intermediate E-XMP* and a hydrolysis step that produces XMP (Figure 1; Tritrichomonas foetus IMPDH numbering) (13). When NADH departs, a mobile flap docks in the vacant dinucleotide site, carrying the catalytic base, Arg418, into the active site. Thus the flap toggles the enzyme between dehydrogenase (flap open, dinucleotide site exposed) and hydrolase conformations (flap closed, dinucleotide site occluded). Compounds such as mycophenolic acid inhibit IMPDH by competing with the flap for the vacant NAD+ site, thus trapping E-XMP* (Figure 1). Similarly, NAD+ inhibits by forming a nonproductive E-XMP*·NAD+ complex.

Figure 1.

The mechanism of the IMPDH reaction. (A) The chemical transformations. (B) The protein conformational changes highlighting the competition of the active site flap and inhibitors such as mycophenolic acid (MPA) for the dinucleotide site.

Despite such multiple functional constraints, the residues comprising the flap and NAD+ site vary widely among enzymes from different sources, as does the equilibrium between open and closed conformations (14–16). We have proposed that this divergence is a response to naturally occurring IMPDH inhibitors such as mycophenolic acid, which traps E-XMP*, and mizoribine monophosphate, which stabilizes the closed conformation. Indeed, a mutation that causes resistance to mycophenolic acid renders the enzyme hypersensitive to mizoribine, demonstrating how chemical warfare at the microbial level might drive evolution (17). IMPDHs that are resistant to mycophenolic acid have high values of kcat, which indicates that the equilibrium between open and closed conformations controls both inhibition and the catalytic cycle (13). For efficient catalysis, the affinity of the flap and NAD+ must be balanced so that the productive E·IMP·NAD+ complex can form but the nonproductive E-XMP*·NAD+ complex does not accumulate. Together, these observations pose an evolutionary conundrum: for catalytic success, a mutation must simultaneously increase (or simultaneously decrease) the affinity of both the flap and NAD+.

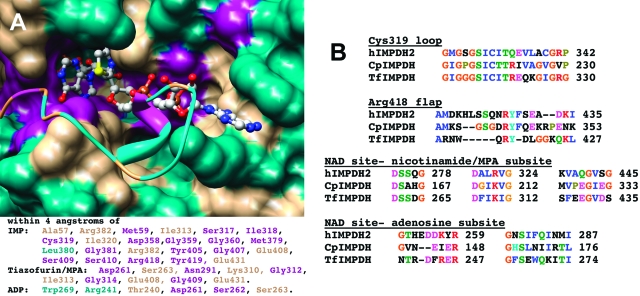

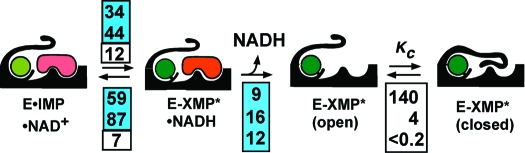

CpIMPDH provides a convenient system to test these ideas: while the active site of the hydrolase conformation of CpIMPDH is very similar to that of the well-characterized TfIMPDH (Figure 2), the equilibrium between open and closed conformations varies dramatically (4 for CpIMPDH, 140 for TfIMPDH, and ≤0.2 in hIMPDH2; (16,18)).

Figure 2.

The active site of IMPDH. (A) The open conformation from the X-ray crystal structure of E·IMP·β-Me-TAD (PDB accession number 1LRT) is shown in surface rendering while the flap from the closed conformation is depicted in ribbon (PDB accession number 1PVN). Note how the flap competes with β-Me-TAD. The active site is colored by conservation: magenta, conserved in all three enzymes; tan, conserved in two enzymes; cyan, different in all three enzymes. The residues within 4 Å of IMP and β-Me-TAD are listed using the same color scheme. Figure is rendered in Chimera (49). (B) Selected alignments of CpIMPDH, TfIMPDH, and hIMPDH2 shown in the Clustal X coloring scheme.

Here we delineate the kinetic mechanism of CpIMPDH and hIMPDH2 in order to investigate how differences in the dynamic properties of the flap influence the catalytic cycle and to identify functional differences that might explain why C. parvum discarded its eukaryotic IMPDH in favor of the bacterial version. These experiments demonstrate that, despite large differences in equilibrium between open and closed conformations, the catalytic power of the hydrolase conformation is similar among CpIMPDH and TfIMPDH. The kinetic mechanism derived in this work has already proven invaluable in inhibitor discovery (19).

Materials and Methods

Materials

IMP, XMP, GMP, 3-acetylpyridine adenine dinucleotide (APAD+), and NADH were purchased from Sigma. NAD+ was purchased from Roche. DTT was purchased from Research Organics, Inc. Tris, glycerol, EDTA, trichloroacetic acid, and KCl were purchased from Fisher Scientific. HA nitrocellulose filters were purchased from Millipore. [8-14C]IMP was obtained from Moravek Biochemicals, Inc. D2O and DCl were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc. EICARMP was a gift from A. Matsuda (Hokkaido University, Japan).

General

Free acid forms were used for all substrates, products, and ligands with the following exceptions. The sodium form of NADH was converted into a TrisH+ form by cation exchange using Dowex 50WX4 resin (Sigma). [8-14C]IMP was used as the ditriethylammonium salt.

Expression and Purification of CpIMPDH

CpIMPDH was expressed and purified as previously described (16). Purity was >95% as assessed by SDS−PAGE. The concentration of CpIMPDH was determined by Bio-Rad assay using IgG as a standard and by active site titration with the irreversible inactivator EICARMP (20) (data not shown). The Bio-Rad assay overestimates enzyme concentration by a factor of 2.6. This is comparable to the correction factors measured for the IMPDHs from Escherichia coli(20) and T. foetus(18).

Steady-State Kinetics

Standard IMPDH assays were performed in assay buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM KCl, and 1 mM DTT) at 25 °C. The production of NADH and reduced 3-acetylpyridine adenine dinucleotide (APADH) was monitored spectrophotometrically at 340 nm (ϵ = 6.22 mM−1 cm−1) and 363 nm (ϵ = 9.1 mM−1 cm−1), respectively. Steady-state parameters for the NAD+ reaction were determined by measuring initial velocities while varying both substrates. Initial velocities were fit by the Michaelis−Menten equation (eq 1) or an equation including uncompetitive inhibition (eq 2) using SigmaPlot (Systat Software, Inc.)

where v is the initial velocity, Vm is the maximal velocity, KM is the Michaelis constant for substrate (S), and Kii is the inhibition constant for S. Steady-state parameters with respect to NAD+ were determined by deriving the apparent Vm values from plots of initial velocity versus IMP concentration (eq 1). These were replotted versus NAD+ concentration, and the steady-state parameters were calculated from eq 2. Similarly, apparent Vm values from initial velocities versus NAD+ concentration (eq 2) were replotted versus IMP concentration, and the Michaelis constant for IMP was derived from eq 1. The apparent steady-state parameters for APAD+ were derived from initial velocity versus dinucleotide concentration at saturating IMP (500 μM) using eq 1.

Equilibrium Dissociation Constants (Kd)

Ligand was successively added to 0.1−0.15 μM CpIMPDH in assay buffer at 25 °C. The equilibrium protein fluorescence was measured with a Hitachi F-2000 fluorescence spectrophotometer. In order to minimize inner filter effects, excitation wavelengths of 290 nm for IMP and NADH and 295 nm for NAD+, XMP, and GMP were used. Emission was monitored at 344 nm for IMP, NAD+, XMP, and GMP and at 342 nm for NADH. Inner filter corrections were calculated by the formula

where Fc is the corrected fluorescence, Fo is the observed fluorescence, and Aex and Aem are the absorbencies at the excitation and emission wavelengths, respectively. Fc/Fo was less than 2 for all ligand concentrations used. Since purines are known fluorescent quenchers (21), nonspecific quenching was measured by titrating ligand against a solution of l-Trp and was described by the Stern−Volmer relation

where F0 is the unquenched fluorescence, F is the fluorescence at a given quencher (Q) concentration, and KQ is the quenching constant. The experimentally determined values of KQ with l-Trp were used to calculate correction factors (F0/F) that were applied to the binding data. The values of KQ−1 for IMP, XMP, GMP, NAD+, and NADH are 5.5, 0.53, 1.1, 4.3, and 0.24 mM, respectively. The corrected fluorescence due to binding (Fbind) was calculated using eq 5.

The program DynaFit (22) was used to describe Fbind versus ligand concentration with a simple one-step binding mechanism.

Solvent Deuterium Isotope Effects

Assay buffer was prepared in either H2O or D2O. The pH meter readings for the D2O solutions were adjusted by adding 0.4. Initial velocities were measured for varying dinucleotide concentrations in assay buffer with 500 and 400 μM IMP for CpIMPDH and hIMPDH2, respectively. Steady-state parameters for the CpIMPDH reaction were derived from eq 2 and eq 1 for NAD+ and APAD+, respectively, and eq 2 was used for hIMPDH2.

Ligand Binding Kinetics

The kinetics of XMP binding were measured with an Applied Photophysics SX.17MV stopped-flow spectrophotometer by monitoring the changes in protein fluorescence (excitation = 295 nm, 320 nm cutoff filter). Equal volumes of enzyme and XMP were combined at time 0 in assay buffer at 25 °C giving a final concentration of 0.4 μM enzyme and 30 or 120 μM XMP.

Pre-Steady-State Kinetics

Pre-steady-state experiments were performed monitoring either NADH absorbance (340 nm) or fluorescence (340 nm excitation, 420 nm cutoff filter). Enzyme and saturating IMP were preincubated and combined with an equal volume of NAD+ at time 0. For CpIMPDH, NAD+ was varied against a final concentration of 500 μM IMP and 2.7 and 1 μM enzyme for the absorbance and fluorescence experiments, respectively. Fluorescence experiments with hIMPDH2 used final concentrations of 20−200 μM NAD+ combined with 4.0 μM enzyme and 2 mM IMP. Absorbance experiments also used 2 mM IMP but with 1, 1.75, or 3.5 μM enzyme with 400 μM NAD+ or 3.5 μM enzyme with 1 mM NAD+.

Progress curves were fit using either a single (eq 6) or double (eq 7) exponential equation with a steady-state term.

St is the signal at time t, A1 and A2 are the amplitudes of the first and second phases respectively, kobs1 and kobs2 are the observed first-order rate constants for the first and second phases respectively, v is the steady-state rate, and b is a background term. The hyperbolic dependence of kobs on NAD+ concentration was described by

where kmax is the maximal value of kobs and Kapp is the concentration of [NAD+] at 1/2 kmax.

Labeling IMPDH with [8-14C]IMP

Accumulation of the covalent E-XMP* complex was measured from reactions with 100 μM [8-14C]IMP, 500 μM NAD+, and 1 μM CpIMPDH in assay buffer at 25 °C. Reactions were quenched during the steady state prior to 10% completion by precipitation with cold TCA to a final concentration of 10%. Enzyme was captured on 0.45 μm HA nitrocellulose filters (prewet with 10% TCA) and washed with cold 10% TCA. Radioactivity was measured by scintillation counting. Control reactions lacked either enzyme or NAD+.

Results

Steady-State Kinetic Parameters of CpIMPDH

We determined the steady-state parameters for CpIMPDH using active site titrated enzyme and varying both substrate concentrations (Table 1). These values are in good agreement with our previous report (16). Importantly, the values of kcat for NAD+ and APAD+ are comparable, suggesting that these two reactions share a common rate-limiting step, most likely the hydrolysis of E-XMP*. Solvent isotope effects on kcat of 2.6 and 3.3 were observed for the NAD+ and APAD+ reactions, respectively (Table 1), which further indicates that the hydrolysis of E-XMP* is rate-limiting.

Table 1. Steady-State Parameters for CpIMPDH and hIMPDH2a.

|

CpIMPDH |

hIMPDH2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| parameter | NAD+ | APAD+b | NAD+ |

| kcat (s−1) | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.04 | 0.39 ± 0.01c |

| KM IMP (μM) | 13 ± 3 | ndd | 4 ± 1c |

| KM dinucleotide (μM) | 140 ± 10 | 190 ± 9 | 6 ± 1c |

| Kii dinucleotide (mM)e | 4.9 ± 0.5 | naf | 0.59 ± 0.02c |

| kcat/KM IMP (M−1 s−1) | (2.0 ± 0.5) × 105 | ndd | (9.8 ± 1.4) × 104 c |

| kcat/KM dinucleotide (M−1 s−1) | (1.9 ± 0.2) × 104 | (1.6 ± 0.1) × 104 | (6.5 ± 0.5) × 104 c |

| D2Okcat | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 3.3 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.1 |

Experimental conditions: 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM KCl, and 1 mM DTT at 25 °C.

APAD+ varied at saturating IMP (500 μM).

Values from ref 24.

Not determined.

Intercept inhibition constant describing uncompetitive inhibition, nomenclature of Cleland (48).

Not applicable.

Ligand Binding to CpIMPDH

We measured the binding of substrates and products to CpIMPDH by monitoring changes in intrinsic protein fluorescence. CpIMPDH contains two Trp residues (Trp90 and Trp368). The corresponding residues in TfIMPDH (Phe99 and Gln470, respectively) are located ∼25 Å from the active site. Nevertheless, all ligands produce decreases in CpIMPDH fluorescence. Corrections for inner filter effects and nonspecific quenching were made as described in Materials and Methods. In all cases, the data are well described by a simple binding mechanism. The values of Kd for IMP, XMP, and GMP are similar (∼5 μM, Table 2, Figure S1; the notation “S” denotes figures, etc., in the Supporting Information). In contrast, NADH binds with greater affinity than NAD+ by a factor of 6 (Table 2). The values of Kd for both IMP and NAD+ are significantly lower than their respective KM values. This observation suggests that both substrates are “sticky”, i.e., react to form products faster than they are released from the enzyme.

Table 2. Dissociation Constants for CpIMPDH.

| ligand | Kd (μM)a |

|---|---|

| IMP | 4.7 ± 0.4 |

| XMP | 5.6 ± 0.6 |

| GMP | 4.8 ± 0.6 |

| NAD+ | 14 ± 1 |

| NADH | 2.3 ± 0.2 |

Binding reactions were done in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM KCl, and 1 mM DTT at 25 °C.

We also investigated the kinetics of XMP association and dissociation. Despite the fact that XMP quenches the intrinsic fluorescence of CpIMPDH, we were unable to observe a signal in the stopped-flow spectroscopy experiments. We conclude that the binding of XMP is too fast to measure (≥200 s−1).

The Pre-Steady-State Reaction of CpIMPDH.

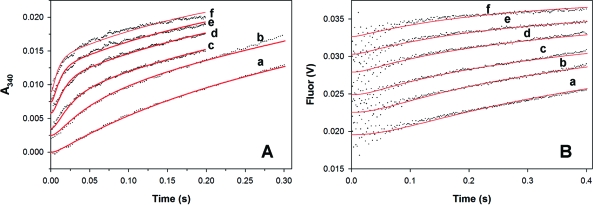

A pre-steady-state burst of NADH production is observed when the CpIMPDH reaction is monitored by absorbance (Figure 3A). The progress curve is well described by a single exponential phase followed by a linear steady state (Figure S2A). The value of kobs for the burst phase displays a hyperbolic dependence on NAD+ concentration (Figure S2B, Table 3). Since absorbance monitors both free and enzyme-bound NADH (23), the maximum value of kobs (kburst = 41 ± 2 s−1) is a composite rate constant including both hydride transfer and NADH release. Therefore, 41 s−1 serves as a lower limit for the rate of hydride transfer.

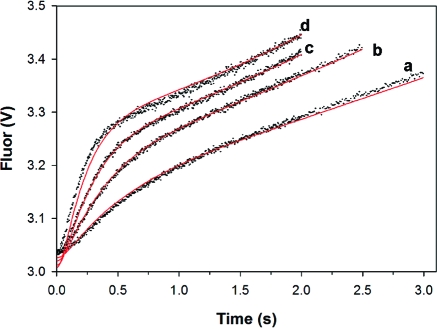

Figure 3.

Global fits of the pre-steady-state CpIMPDH reaction of E·IMP with NAD+. (A) Reaction of 2.7 μM enzyme and 500 μM IMP with NAD+ when monitored by absorbance. (B) Reaction of 1 μM enzyme and 500 μM IMP with NAD+ when monitored by fluorescence. The progress curves for (a) 0.3, (b) 0.6, (c) 1.25, (d) 2.5, (e) 5, and (f) 10 mM NAD+ have been offset for easier visualization. The global fits from using Dynafit (22) and the mechanism of Scheme S1 are in red.

Table 3. Kinetic Parameters for the Pre-Steady-State Reaction of CpIMPDHa.

| parameter | absorbance | fluorescence |

|---|---|---|

| kmax (s−1) | 41 ± 2 | 16 ± 1 |

| Kapp (μM) | 510 ± 90 | 290 ± 60 |

| kmax/Kapp (M−1 s−1) | 8.0 × 104 | 5.6 × 104 |

| [NADH]/[E]total | 0.43 ± 0.01 | ndb |

Experimental conditions: 1 μM CpIMPDH, 500 μM IMP, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM KCl, and 1 mM DTT at 25 °C. Progress curves exhibited a single exponential burst phase followed by a linear steady state and were fit by eq 6. Replots of kobs vs [NAD+] were fit by eq 8 to derive the above pre-steady-state parameters.

Not determined.

Fortuitously, purines are strong quenchers so that the fluorescence of NADH is quenched in the E-XMP*·NADH complex and is only observed when NADH is released from the enzyme (23). A burst of NADH production is also observed when the CpIMPDH reaction is monitored by fluorescence, and again the progress curve is well described by a single exponential burst phase followed by a linear steady state (Figures 3B and S3A). The value of kobs is hyperbolically dependent on NAD+ concentration with a maximum value of 16 s−1 (Figure S3B, Table 3).

Accumulation of E-XMP* in the CpIMPDH Reaction

The above experiments indicate that hydride transfer is fast and hydrolysis is rate-limiting in the CpIMPDH reaction, which predicts that E-XMP* will accumulate in the steady state. Therefore, we measured the incorporation of radioactivity into the protein during the reaction with [8-14C]IMP and NAD+ (500 μM). This NAD+ concentration was chosen to avoid formation of the nonproductive E-XMP*·NAD+ complex. No radioactivity is incorporated into protein if NAD+ is omitted from the reaction. Under these conditions, 25 ± 3% of the enzyme is trapped as E-XMP*, which is comparable to the burst amplitude of NADH produced at similar NAD+ concentrations (30 and 21% at 600 and 300 μM NAD+, respectively).

Global Fits of the CpIMPDH Reaction

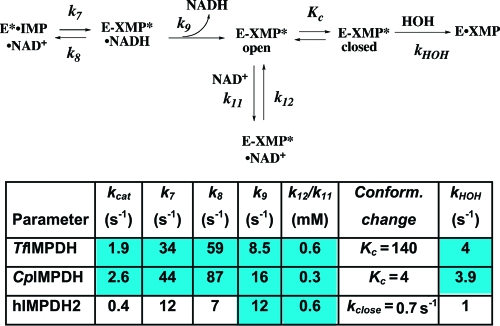

Values for the individual rate constants in the kinetic mechanism of CpIMPDH were derived by fitting the absorbance and fluorescence stopped-flow progress curves using the program DynaFit (22) as described in the Supporting Information. The individual rate constants are shown in Scheme 1. Signal response factors for the fluorescence data were calculated for each concentration of NAD+ to account for inner filter effects by normalizing the linear steady-state regions with the absorbance data. The rate constants for the association of NAD+ to E·IMP (Scheme S1, k5, k6), hydride transfer (k7, k8), and NADH release (k9) are well constrained. As noted above, the release of XMP is fast (≥200 s−1); the individual rate constants (kclose, kopen) describing the movement of the flap were chosen to be arbitrarily fast such that the value of Kc = 4 (16). The individual rate constants for NAD+ binding to E-XMP* (k11, k12) are not well determined, but the ratio k12/k11 is consistently 200−400 μM. Taking into account the competition with the flap, this value is in reasonable agreement with experiment (400 μM × 5 = 2 mM; Kii = 4.9 mM, Table 1). The results of the global fits are summarized in Figure 3, Table S1, and Scheme 1. Using these values, the calculated value of kcat is 1.8 s−1 (eq 11, Supporting Information), in agreement with the measured value of 2.6 s−1. The calculated value of KM NAD+ is 40 μM (eq 12, Supporting Information), similar to the measured value of 140 μM.

Scheme 1. Kinetic Alignment of the IMPDH Reaction.

The values for TfIMPDH are taken from ref (18). The values for the CpIMPDH and hIMPDH2 are from the global and local fit analyses described in the Supplementary Information.

The Kinetic Mechanism of hIMPDH2

Although hydrolysis is rate-limiting in the reaction of hIMPDH2 (24,25), the pre-steady-state reaction had not been characterized in detail. When the reaction was monitored by absorbance, the progress curves display a burst of NADH production and are well described by a single exponential with a linear steady state (Figures 4A and S4A). The amplitude of the burst phase is 0.9 ± 0.1 [NADH]/[E]. The value of kobs = 14 ± 1 s−1 at saturating substrate concentrations (Table S2), which is 35 times greater than the value of kcat (0.4 s−1).

Figure 4.

Global fits of the pre-steady-state hIMPDH2 reaction of E·IMP with NAD+. The fluorescence progress curves when 2.8 μM enzyme and 2 mM IMP are combined with (a) 20 μM NAD+, (b) 40 μM NAD+, (c) 80 μM NAD+, and (d) 200 μM NAD+. The fits of the data by the mechanism of Scheme S2 are shown in red.

When the reaction was monitored by fluorescence, the progress curve exhibits three phases, a lag followed by a burst and a linear steady state, which are well described by eq 7 (Figures 4 and S4A). Replots of the values of kobs1 and kobs2 versus [NAD+] are both hyperbolic, with maximum values of 23 ± 1 s−1 and 12 ± 1 s−1 for the lag and burst phases, respectively (Table 4).

Table 4. Kinetic Parameters for the Pre-Steady-State Reaction of hIMPDH2 Monitored by Intrinsic Protein Fluorescencea.

| parameter | lag phase | burst phase |

|---|---|---|

| kmax (s−1) | 23 ± 1 | 12 ± 1 |

| Kapp (μM) | 68 ± 1 | 86 ± 5 |

| kmax/Kapp (M−1 s−1) | 3.4 × 105 | 1.4 × 105 |

These observations suggest that the hydrolysis of E-XMP* is also rate-limiting in the reaction of hIMPDH2, which predicts that a solvent deuterium isotope effect will be observed on kcat; we do observe a solvent deuterium isotope effect of 1.8 ± 0.1, in contrast to a previous report from another laboratory (25). This discrepancy may result from the different reaction conditions (100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.7, and 10 mM KCl at 37 °C whereas our experiments use 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM KCl, and 1 mM DTT at 25 °C).

Global Fits of the hIMPDH2 Reaction. Values for the individual rate constants in the kinetic mechanism of hIMPDH2 were derived as described above and in the Supporting Information. The individual rate constants derived from the global and local fit analyses are shown in Scheme 1 and Table S1. The rate constants for the association of NAD+ to E·IMP (Scheme S2, k5, k6), hydride transfer (k7, k8), and NADH release (k9) are well constrained. As with CpIMPDH, the individual rate constants for NAD+ binding to E-XMP* (k11, k12) are not well determined; the values of k11 and k12 were set arbitrarily fast such that k12/k11 = Kii = 590 μM (24). Importantly, the magnitude of the solvent isotope effect indicates that hydrolysis is not solely rate-limiting in the hIMPDH2 reaction. Assuming the intrinsic isotope effect is 3, as observed in the reaction of CpIMPDH (as well as in the reaction of serine proteases (26)), then kHOH = 1 s−1 and k = 0.7 s−1 for the second rate-limiting step (27). Both hydride transfer and the release of NADH are much faster than 0.7 s−1. Unfortunately, hIMPDH2 does not contain any Trp residues, so the kinetics of ligand binding cannot be directly measured; nevertheless, given the low affinity of XMP (Kd = 140 μM (28)), the release of XMP is unlikely to be rate-limiting. Therefore, we propose that the second rate-limiting step is a conformational change. Since the open flap conformation is favored in hIMPDH2 (Kc ≤ 0.2) (14), we have provisionally assigned 0.7 s−1 to kclose.

Discussion

We have now characterized the kinetic mechanisms of TfIMPDH, CpIMPDH, and hIMPDH2; Scheme 1 displays a “kinetic alignment” of these enzymes. The interchange between open and closed conformations of the flap is the most divergent step in these catalytic cycles (Kc in Scheme 1). Since the flap competes with NAD+ for the dinucleotide site, the affinity of NAD+ must be balanced against that of the flap; otherwise nonproductive complexes such as E-XMP*·NAD+ will accumulate. When the fraction of enzyme in the open conformation is taken into account, the “intrinsic binding affinity” of compounds that bind in the NAD site can be considerably greater than the observed binding affinity (Table 5). TfIMPDH dramatically illustrates this principle: although the observed affinity of NAD+ is the lowest of the three enzymes, the intrinsic affinity is the highest. Similar results are observed for the intrinsic affinity of β-methylene-tiazofurin adenine dinucleotide (β-Me-TAD, Figure 5). Curiously, the intrinsic affinities of NAD analogues for CpIMPDH and hIMPDH2 are very similar despite the divergent structures of these dinucleotide sites. Interestingly, the intrinsic affinity of β-Me-TAD differentially distributes across the dinucleotide sites of these three enzymes. The intrinsic affinity of tiazofurin is similar in TfIMPDH and CpIMPDH, as expected given that the structures of the nicotinamide subsites are essentially identical. In contrast, the nicotinamide subsite of hIMPDH2 contains several substitutions, and the intrinsic affinity of tiazofurin is significantly lower. The opposite situation is observed at the adenosine subsite: the intrinsic affinity of ADP is much higher for TfIMPDH than CpIMPDH. This difference is likely to arise from interactions with the adenine ring of ADP, which is sandwiched between Arg241 and Trp269 in TfIMPDH. These residues are Asn144 and Asn171 in CpIMPDH. In hIMPDH2, the adenine is sandwiched between His253 and Phe282, and ADP displays an intrinsic affinity similar to CpIMPDH.

Table 5. Intrinsic Binding Energy of Ligands for the Dinucleotide Sitea.

| NAD+ (mM) |

β-Me-TAD (μM) |

Tz (mM) |

ADP (mM) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| enzyme | Kc | Kii | Kintr | Ki | Kintr | Ki | Kintr | Ki | Kintr |

| TfIMPDHb | 140 | 6.8 ± 1.8 | 0.07 | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 0.02 | 50 ± 10 | 0.3 | 31 ± 2 | 0.2 |

| CpIMPDHc | 4 | 4.9 ± 0.5 | 0.30 | 0.6 ± 0.04 | 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 0.3 | 42 ± 6 | 8 |

| hIMPDH2d | ≤0.2 | 0.59 ± 0.02 | 0.59 | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.06 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 1.3 | 8.8 ± 2.2 | 8.8 |

The intrinsic binding constant for NAD+ is derived from the global fits. The intrinsic binding constants for β-Me-TAD, tiazofurin (Tz), and ADP are calculated from Kintr = Ki (1/(1 + Kc)).

See refs 14 and 23.

See ref 16.

See ref 24. The intrinsic binding constant for NAD+ is derived from the global fits.

Figure 5.

The structure of β-Me-TAD.

Remarkably, despite large differences in the dynamics of the flap, the values of kHOH are identical for CpIMPDH and TfIMPDH. This observation suggests that the dynamics of the flap set the stage for the hydrolysis reaction but do not play an active role in the chemical transformation. The rate constants for hydride transfer are also similar for CpIMPDH and TfIMPDH. The residues in the immediate vicinity of the hypoxanthine and nicotinamide groups are virtually identical for these two enzymes, so this congruence is also not surprising. In fact, with the exception of the equilibrium between open and closed conformations and the binding of NAD+, the kinetic mechanisms of CpIMPDH and TfIMPDH are essentially identical. In contrast, both hydride transfer and hydrolysis are slower in hIMPDH2 than in either of the parasite enzymes. The equilibrium between the E·IMP·NAD+ and E-XMP*·NADH complexes also has changed, which indicates that the transition state for this reaction has also changed. Several substitutions can be found at the active site that may account for this behavior. The most intriguing of these is the substitution of Glu431 with Gln; we have proposed that Glu431 is part of a proton relay that activates water and might also function to activate Cys319 (L. Hedstrom and W. Yang, unpublished). The substitution of Glu431 with Gln does decrease the value of kcat as expected (29).

We are aware of four other enzyme systems where the detailed kinetic mechanisms have been determined for orthologues: triose-phosphate isomerase, dihydrofolate reductase, purine nucleoside phosphorylase, and adenosine deaminase. Product release is rate-limiting in the cases of dihydrofolate reductase and triose-phosphate isomerase, and the values of kcat are similar in orthologues (30–33). In contrast, the values of kcat vary by as much as 2 orders of magnitude, and the chemical transformations are rate-limiting in purine nucleoside phosphorylase and adenosine deaminase (34,35). Here the structures of the transition state change, as we envision the transition structure must change in hIMPDH2 versus CpIMPDH and TfIMPDH. Interestingly, substitutions quite remote from the active site contribute to these changes (36).

Why does C. parvum utilize a bacterial IMPDH? Interestingly, many eukaryotic pathogens, including Trypanomastids, Giardia lamblia, Entamoeba histolytica, and Trichomonas vaginalis, have remodeled and simplified their metabolic pathways while adopting bacterial genes, so this phenomenon is widespread (37–40). One simple hypothesis is that the higher values of kcat associated with bacterial IMPDHs promote greater flux through the guanine nucleotide biosynthetic pathways. Our experiments suggest that this is not the case: though the rate constants for individual steps in the reactions of CpIMPDH and hIMPDH2 are often significantly different, the flux through both enzymes will be comparable in vivo, assuming that the physiological concentrations of NAD+ and IMP in the parasite are similar to those of most organisms ([IMP] = 20−60 μM (41); [NAD+] = 0.3−2 mM (42)). Therefore, it seems unlikely that C. parvum chose the bacterial enzyme to increase the production of guanine nucleotides. Instead, a moonlighting function may have provided the impetus for the switch. Virtually all IMPDHs contain a subdomain. The subdomain is not required for enzymatic activity (43–45), and its function is currently under debate. CpIMPDH lacks the subdomain and, therefore, may be missing the moonlighting functions of the host enzyme. Intriguingly, the subdomain has recently been shown to regulate the distribution of purine nucleotides between the adenine and guanine nucleotide pools in E. coli(46), and it seems reasonable to expect this regulation would be different in C. parvum given its unusual purine salvage pathway. We have found that the subdomain mediates the association of IMPDH with single-stranded nucleic acids (47) and may well have an as yet unappreciated role in RNA metabolism that would also be different in C. parvum.

The kinetic mechanism derived herein has already proved invaluable in designing a high throughput screen to identify selective inhibitors of CpIMPDH (19). We used Scheme 1 to define assay conditions such that the dinucleotide site was empty in the predominant enzyme forms, thus selecting for inhibitors that bind to the most diverged site on the enzyme. These results demonstrate how a detailed understanding of enzyme kinetics can be important in drug discovery.

Supporting Information Available

Equilibrium fluorescence binding data as well as local and global fit analyses of the absorbance and fluorescence stopped-flow data for CpIMPDH and hIMPDH2. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Footnotes

Abbreviations: IMP, inosine 5′-monophosphate; XMP, xanthosine 5′-monophosphate; NAD+, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; NADH, reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; APAD+, acetylpyridine adenine dinucleotide; APADH, reduced acetylpyridine adenine dinucleotide; IMPDH, inosine-5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase; CpIMPDH, Cryptosporidium parvum IMPDH; hIMPDH1, human IMPDH type 1; hIMPDH2, human IMPDH type 2; TfIMPDH, Tritrichomonas foetus IMPDH; GMP, guanosine monophosphate; tiazofurin, 2-β-d-ribofuranosylthiazole-4-carboxamide; ADP, adenosine-5′-diphosphate; β-Me-TAD, β-methylene-tiazofurin adenine dinucleotide; MPA, mycophenolic acid; EICARMP, 5-ethynyl-1-β-d-ribofuranosylimidazole-4-carboxamide-5′-monophosphate; DTT, dithiothreitol.

Supplementary Material

References

- Jackson R.; Weber G.; Morris H. P. (1975) IMP dehydrogenase, an enzyme linked with proliferation and malignancy. Nature 256, 331–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pankiewicz K. W.; Lesiak-Watanabe K. B.; Watanabe K. A.; Patterson S. E.; Jayaram H. N.; Yalowitz JA M. M.; Seidman M.; Majumdar A.; Prehna G.; Goldstein B. M. (2002) Novel mycophenolic adenine bis(phosphonate) analogues as potential differentiation agents against human leukemia. J. Med. Chem. 45, 703–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair V.; Shu Q. (2007) Inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase as a probe in antiviral drug discovery. Antiviral Chem. Chemother. 18, 245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D. B.; Chappell C.; Okhuysen P. C. (2004) Cryptosporidiosis in children. Semin. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. 15, 253–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman D. S.; Lescano A. G.; Gilman R. H.; Lopez S. L.; Black M. M. (2002) Effects of stunting, diarrhoeal disease, and parasitic infection during infancy on cognition in late childhood: a follow-up study. Lancet 359, 564–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D. B.; White A. C. (2006) An updated review on Cryptosporidium and Giardia. Gastroenterol. Clin. North. Am. 35, 291–314, viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striepen B.; Pruijssers A. J.; Huang J.; Li C.; Gubbels M. J.; Umejiego N. N.; Hedstrom L.; Kissinger J. C. (2004) Gene transfer in the evolution of parasite nucleotide biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 3154–3159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrahamsen M. S.; Templeton T. J.; Enomoto S.; Abrahante J. E.; Zhu G.; Lancto C. A.; Deng M.; Liu C.; Widmer G.; Tzipori S.; Buck G. A.; Xu P.; Bankier A. T.; Dear P. H.; Konfortov B. A.; Spriggs H. F.; Iyer L.; Anantharaman V.; Aravind L.; Kapur V. (2004) Complete genome sequence of the apicomplexan, Cryptosporidium parvum. Science 304, 441–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P.; Widmer G.; Wang Y.; Ozaki L. S.; Alves J. M.; Serrano M. G.; Puiu D.; Manque P.; Akiyoshi D.; Mackey A. J.; Pearson W. R.; Dear P. H.; Bankier A. T.; Peterson D. L.; Abrahamsen M. S.; Kapur V.; Tzipori S.; Buck G. A. (2004) The genome of Cryptosporidium hominis. Nature 431, 1107–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striepen B.; White M. W.; Li C.; Guerini M. N.; Malik S. B.; Logsdon J. M. Jr.; Liu C.; Abrahamsen M. S. (2002) Genetic complementation in apicomplexan parasites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 6304–6309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J.; Mullapudi N.; Lancto C. A.; Scott M.; Abrahamsen M. S.; Kissinger J. C. (2004) Phylogenomic evidence supports past endosymbiosis, intracellular and horizontal gene transfer in Cryptosporidium parvum. Genome Biol. 5, R88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gherardi A.; Sarciron M. E. (2007) Molecules targeting the purine salvage pathway in Apicomplexan parasites. Trends Parasitol. 23, 384–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedstrom L.; Gan L. (2006) IMP dehydrogenase: structural schizophrenia and an unusual base. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 10, 520–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Digits J. A.; Hedstrom L. (2000) Drug selectivity is determined by coupling across the NAD+ site of IMP dehydrogenase. Biochemistry 39, 1771–1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan L.; Seyedsayamdost M. R.; Shuto S.; Matsuda A.; Petsko G. A.; Hedstrom L. (2003) The immunosuppressive agent mizoribine monophosphate forms a transition state analog complex with IMP dehydrogenase. Biochemistry 42, 857–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umejiego N. N.; Li C.; Riera T.; Hedstrom L.; Striepen B. (2004) Cryptosporidium parvum IMP dehydrogenase: Identification of functional, structural and dynamic properties that can be exploited for drug design. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 40320–40327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler G. A.; Gong X.; Bentink S.; Theiss S.; Pagani G. M.; Agabian N.; Hedstrom L. (2005) The functional basis of mycophenolic acid resistance in Candida albicans IMP dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 11295–11302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillén Schlippe Y. V.; Riera T. V.; Seyedsayamdost M. R.; Hedstrom L. (2004) Substitution of the conserved Arg-Tyr dyad selectively disrupts the hydrolysis phase of the IMP dehydrogenase reaction. Biochemistry 43, 4511–4521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umejiego N. N.; Gollapalli D.; Sharling L.; Volftsun A.; Lu J.; Benjamin N. N.; Stroupe A. H.; Riera T. V.; Striepen B.; Hedstrom L. (2008) Targeting a prokaryotic protein in a eukaryotic pathogen: identification of lead compounds against cryptosporidiosis. Chem. Biol. 15, 70–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W.; Papov V. V.; Minakawa N.; Matsuda A.; Biemann K.; Hedstrom L. (1996) Inactivation of inosine 5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase by the antiviral agent 5-ethynyl-1-β-d-ribofuranosylimidazole-4-carboxamide 5′-monophosphate. Biochemistry 35, 95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakowicz J. R. (1999) Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy, 2nd ed., Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzmic P. (1996) Program DYNAFIT for the analysis of enzyme kinetic data: application to HIV proteinase. Anal. Biochem. 237, 260–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Digits J. A.; Hedstrom L. (1999) Kinetic mechanism of Tritrichomonas foetus inosine-5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase. Biochemistry 38, 2295–2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W.; Hedstrom L. (1997) The kinetic mechanism of human inosine 5′-monophosphate type II: random addition of substrates, ordered release of products. Biochemistry 36, 8479–8483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang B.; Markham G. D. (1997) Probing the mechanism of inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase with kinetic isotope effects and NMR determination of the hydride transfer stereospecificity. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 348, 378–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedstrom L. (2002) Serine protease mechanism and specificity. Chem. Rev. 102, 4501–4524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northrop D. B. (1975) Steady-state analysis of kinetic isotope effects in enzymic reactions. Biochemistry 14, 2644–2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang B.; Markham G. D. (1996) The conformation of inosine-5′-monphosphate (IMP) bound to IMP dehydrogenase determined by transferred nuclear overhauser effect spectroscopy. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 27531–27535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Digits J. A.; Hedstrom L. (1999) Species-specific inhibition of inosine 5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase by mycophenolic acid. Biochemistry 38, 15388–15397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fierke C. A.; Johnson K. A.; Benkovic S. J. (1987) Construction and evaluation of the kinetic scheme associated with dihydrofolate reductase from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 26, 4085–4092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews J.; Fierke C. A.; Birdsall B.; Ostler G.; Feeney J.; Roberts G. C.; Benkovic S. J. (1989) A kinetic study of wild-type and mutant dihydrofolate reductases from Lactobacillus casei. Biochemistry 28, 5743–5750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thillet J.; Adams J. A.; Benkovic S. J. (1990) The kinetic mechanism of wild-type and mutant mouse dihydrofolate reductases. Biochemistry 29, 5195–5202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickbarg E. B.; Knowles J. R. (1988) Triosephosphate isomerase: energetics of the reaction catalyzed by the yeast enzyme expressed in Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 27, 5939–5947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo M.; Li L.; Schramm V. L. (2008) Remote mutations alter transition-state structure of human purine nucleoside phosphorylase. Biochemistry 47, 2565–2576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo M.; Singh V.; Taylor E. A.; Schramm V. L. (2007) Transition-state variation in human, bovine, and Plasmodium falciparum adenosine deaminases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 8008–8017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saen-Oon S.; Ghanem M.; Schramm V. L.; Schwartz S. D. (2008) Remote mutations and active site dynamics correlate with catalytic properties of purine nucleoside phosphorylase. Biophys. J. 94, 4078–4088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loftus B.; Anderson I.; Davies R.; Alsmark U. C.; Samuelson J.; Amedeo P.; Roncaglia P.; Berriman M.; Hirt R. P.; Mann B. J.; Nozaki T.; Suh B.; Pop M.; Duchene M.; Ackers J.; Tannich E.; Leippe M.; Hofer M.; Bruchhaus I.; Willhoeft U.; Bhattacharya A.; Chillingworth T.; Churcher C.; Hance Z.; Harris B.; Harris D.; Jagels K.; Moule S.; Mungall K.; Ormond D.; Squares R.; Whitehead S.; Quail M. A.; Rabbinowitsch E.; Norbertczak H.; Price C.; Wang Z.; Guillen N.; Gilchrist C.; Stroup S. E.; Bhattacharya S.; Lohia A.; Foster P. G.; Sicheritz-Ponten T.; Weber C.; Singh U.; Mukherjee C.; El-Sayed N. M.; Petri W. A. Jr.; Clark C. G.; Embley T. M.; Barrell B.; Fraser C. M.; Hall N. (2005) The genome of the protist parasite Entamoeba histolytica. Nature 433, 865–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison H. G.; McArthur A. G.; Gillin F. D.; Aley S. B.; Adam R. D.; Olsen G. J.; Best A. A.; Cande W. Z.; Chen F.; Cipriano M. J.; Davids B. J.; Dawson S. C.; Elmendorf H. G.; Hehl A. B.; Holder M. E.; Huse S. M.; Kim U. U.; Lasek-Nesselquist E.; Manning G.; Nigam A.; Nixon J. E.; Palm D.; Passamaneck N. E.; Prabhu A.; Reich C. I.; Reiner D. S.; Samuelson J.; Svard S. G.; Sogin M. L. (2007) Genomic minimalism in the early diverging intestinal parasite Giardia lamblia. Science 317, 1921–1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opperdoes F. R.; Michels P. A. (2007) Horizontal gene transfer in trypanosomatids. Trends Parasitol. 23, 470–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlton J. M.; Hirt R. P.; Silva J. C.; Delcher A. L.; Schatz M.; Zhao Q.; Wortman J. R.; Bidwell S. L.; Alsmark U. C.; Besteiro S.; Sicheritz-Ponten T.; Noel C. J.; Dacks J. B.; Foster P. G.; Simillion C.; Van de Peer Y.; Miranda-Saavedra D.; Barton G. J.; Westrop G. D.; Muller S.; Dessi D.; Fiori P. L.; Ren Q.; Paulsen I.; Zhang H.; Bastida-Corcuera F. D.; Simoes-Barbosa A.; Brown M. T.; Hayes R. D.; Mukherjee M.; Okumura C. Y.; Schneider R.; Smith A. J.; Vanacova S.; Villalvazo M.; Haas B. J.; Pertea M.; Feldblyum T. V.; Utterback T. R.; Shu C. L.; Osoegawa K.; de Jong P. J.; Hrdy I.; Horvathova L.; Zubacova Z.; Dolezal P.; Malik S. B.; Logsdon J. M. Jr.; Henze K.; Gupta A.; Wang C. C.; Dunne R. L.; Upcroft J. A.; Upcroft P.; White O.; Salzberg S. L.; Tang P.; Chiu C. H.; Lee Y. S.; Embley T. M.; Coombs G. H.; Mottram J. C.; Tachezy J.; Fraser-Liggett C. M.; Johnson P. J. (2007) Draft genome sequence of the sexually transmitted pathogen Trichomonas vaginalis. Science 315, 207–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traut T. W. (1994) Physiological concentrations of purines and pyrimidines. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 140, 1–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belenky P.; Bogan K. L.; Brenner C. (2007) NAD+ metabolism in health and disease. Trends Biochem. Sci. 32, 12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X.; Cahoon M.; Rosa P.; Hedstrom L. (1997) Expression, purification and charcterization of inosine-5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase from Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 21977–21981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimmesgern E.; Black J.; Futer O.; Fulghum J. R.; Chambers S. P.; Brummel C. L.; Raybuck S. A.; Sintchak M. D. (1999) Biochemical analysis of the modular enzyme inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase. Protein Expression Purif. 17, 282–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan L.; Petsko G. A.; Hedstrom L. (2002) Crystal structure of a ternary complex of Tritrichomonas foetus inosine 5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase: NAD+ orients the active site loop for catalysis. Biochemistry 41, 13309–13317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimkin M.; Markham G. D. (2008) The CBS subdomain of inosine 5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase regulates purine nucleotide turnover. Mol. Microbiol. 69, 342–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean J. E.; Hamaguchi N.; Belenky P.; Mortimer S. E.; Stanton M.; Hedstrom L. (2004) Inosine 5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase binds nucleic acids in vitro and in vivo. Biochem. J. 379, 243–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleland W. W. (1963) The kinetics of enzyme-catalyzed reactions with two or more substrates or products. I. Nomenclature and rate equations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 67, 104–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen E. F.; Goddard T. D.; Huang C. C.; Couch G. S.; Greenblatt D. M.; Meng E. C.; Ferrin T. E. (2004) UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.