Abstract

Purpose

We report local control outcomes, as assessed by posttreatment biopsies in patients who underwent 3-dimensional conformal radiotherapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. In addition, we report the influence of local tumor control on long-term distant metastases and cause specific survival outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Posttreatment prostate biopsies were performed in 339 patients who underwent 3-dimensional conformal radiotherapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. The histological outcome of prostate biopsy was classified as positive—prostatic adenocarcinoma without typical radiation induced changes or negative—no evidence of carcinoma or severe treatment effect. Median followup in this group of 339 patients was 10 years after the completion of treatment and 6.25 years after posttreatment biopsy.

Results

Overall biopsy outcomes in these patients were positive in 32%, severe treatment effect in 21% and negative in 47%. A higher radiation dose in the intermediate and high risk subgroups was associated with a lower incidence of positive biopsy. Of patients at intermediate risk who received a dose of 75.6 or greater 24% had a positive biopsy compared to 42% who received 70.2 Gy or less (p = 0.03). In the high risk group positive treatment biopsies were noted in 51% of patients who received 70.2 Gy or less, 33% of those who received 75.6 Gy and 15% of those who received 81 Gy or greater (70.2 or less vs 75.6 Gy p = 0.07 and 75.6 vs 81 Gy or greater p = 0.05). Short course neoadjuvant androgen deprivation therapy before 3-dimensional conformal radiotherapy had a significant impact on the posttreatment biopsy outcome. Of patients who did not receive androgen deprivation therapy 42% had a positive biopsy compared to 16% who received androgen deprivation therapy (p <0.0001). Patients with negative and severe treatment effect biopsies had similar 10-year prostate specific antigen relapse-free survival outcomes that were markedly different from outcomes in those with positive treatment biopsies. Multivariate analysis indicated that the strongest predictor of biochemical failure was posttreatment biopsy status (positive vs severe treatment effect or negative p <0.001), followed by pretreatment prostate specific antigen (p = 0.05) and clinical T stage (p = 0.09). Similarly multivariate analysis revealed that a positive posttreatment biopsy was one of the strongest predictors of distant metastasis and prostate cancer death in this cohort of patients.

Conclusions

As assessed by posttreatment prostate biopsies, local control is improved with higher radiation doses. Long-term biochemical outcomes in patients with posttreatment biopsies demonstrating severe treatment effect changes were not different than those in patients with negative biopsies. We also noted that local tumor control was associated with a decrease in distant metastases and prostate cancer mortality, further highlighting the importance of achieving optimal tumor control in patients with clinically localized disease.

Keywords: prostate, biopsy, mortality, radiotherapy, neoplasm metastasis

Several randomized trials have now demonstrated improved outcomes when higher external beam radiation doses are used to treat patients with prostate cancer compared to lower dose levels.1–4 In these studies dose levels of 78 Gy or higher were associated with improved PSA relapse-free survival outcomes for patients at favorable, intermediate and high risk. We have previously hypothesized that improved outcomes can be directly attributable to more effective eradication of intraprostatic disease with high dose therapy, which in turn should lead to a decrease in distant metastases. We have previously reported that higher radiation dose levels were associated with improved local tumor control based on posttreatment biopsies obtained 2.5 years or more after RT.5

There remain several unanswered questions regarding the significance of posttreatment biopsy status as a predictor of subsequent outcome in patients treated with definitive RT. While retrospective reports have suggested a correlation between local tumor control after prostate RT and the development of distant metastases, local control was often not rigorously evaluated in these studies with sextant or more biopsies at least 2 years after treatment.6,7 The recognized pathological entities of severe treatment effect and post-therapy changes have added substantial complexity to the pathological evaluation of these biopsy specimens.8,9 Furthermore, there has been controversy as to the clinical significance of the treatment effect in the biopsy and whether such findings are consistent with viable or nonviable prostate cancer.10

At our institution we have followed closely a cohort of patients who have undergone posttreatment biopsies after high dose conformal external beam RT. Using strict criteria for pathological evaluation biopsies were categorized as positive, negative or containing only treatment effect changes. In this study we correlated posttreatment biopsy status with 10-year clinical outcomes. Our results indicate that patients with biopsies consistent with a treatment effect have clinical outcomes similar to those in patients with negative biopsies. In addition, patients with positive biopsies are at increased risk for distant metastases, establishing additional evidence that the local control of prostate cancer is associated with a decrease in the distant dissemination of disease and prostate cancer mortality.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A total of 1,773 patients with stages T1c–T3 were treated with 3-dimensional conformal RT or intensity modulated RT between April 1989 and June 2001. Cases were staged according to the 2005 American Joint Committee on cancer staging classification system. All patients had biopsy proven adenocarcinoma that was classified according to the Gleason grading system.

Details of treatment technique, planning and delivery have been described in prior publications.11,12 The prescribed radiation dose represented the minimum dose to the planning target volume but portions of the target, including the iso-center (International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements prescription point), received up to 10% higher dose levels. To assess the local response of the tumor to treatment transrectal ultrasound guided biopsies (minimum of 6 cores) were performed. All patients with a minimum followup of 2.5 years after the completion of RT were encouraged to undergo posttreatment biopsy independent of PSA at the time. In general elderly patients (80 years or older), those with medical contraindications and those who refused were excluded. A total of 339 patients underwent posttreatment biopsy. Table 1 compares the clinical characteristics of these patients with the characteristics of those who did not undergo posttreatment biopsy. Of patients who underwent posttreatment biopsy there was a greater percent with pretreatment PSA more than 10 ng/ml, a lower incidence of NAAD and age younger than 65 years (table 1). Median time from the completion of RT to posttreatment biopsy was 38 months. Median time from the completion of RT to posttreatment biopsy in the different dose groups was similar, that is 38.5, 38 and 37 months for 70.2, 75.6 and 81 Gy, respectively.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients with vs without post-RT biopsies

| Pt Characteristics | No. Biopsy (%) | No. No Biopsy (%) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. pts | 339 | 1,434 | |

| T stage: | |||

| T1c | 81 (24) | 541 (38) | <0.001 |

| T2a–c | 183 (54) | 654 (47) | 0.10 |

| T3a–c | 75 (22) | 238 (17) | 0.05 |

| T4 | 0 | 1 (less than 1) | 0.43 |

| Gleason: | |||

| 6 or Less | 153 (45) | 738 (51) | 0.22 |

| Greater than 6 | 186 (55) | 696 (49) | 0.23 |

| Pretreatment PSA (ng/ml): | |||

| 10 or Less | 164 (48) | 1,009 (70) | 0.002 |

| Greater than 10 | 175 (52) | 425 (30) | 0.00 |

| NCCN risk group: | |||

| Low | 47 (14) | 342 (24) | 0.009 |

| Intermediate | 149 (44) | 598 (42) | 0.63 |

| High | 143 (42) | 494 (34) | 0.07 |

| Age: | |||

| 65 or Younger | 126 (37) | 409 (29) | 0.025 |

| Older than 65 | 213 (63) | 1,025 (71) | 0.18 |

| NAAD: | |||

| No | 206 (61) | 762 (53) | 0.18 |

| Yes | 133 (39) | 672 (47) | 0.11 |

| Dose (Gy): | |||

| Less than 75.6 | 95 (28) | 273 (19) | 0.002 |

| 75.6 or Greater | 244 (72) | 1,154 (81) | 0.23 |

| PSA failure: | |||

| No | 159 (47) | 1,082 (76) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 180 (53) | 345 (24) | 0.00 |

| Post-RT biopsy outcome: | Not applicable | ||

| Pos | 107 (32) | ||

| Treatment effect | 71 (21) | ||

| Neg | 161 (47) | ||

In general pretreatment ADT was used in patients with high Gleason score stage T3 cancer or for a pretreatment volume decrease in patients with an enlarged prostate gland. When ADT was used, it was initiated 3 months before RT and continued during the 2.5-month course of treatment. ADT was routinely discontinued at the completion of RT.

The histological outcome of the posttreatment prostate biopsy was classified as positive—prostatic adenocarcinoma showing at least some component typical radiation induced changes or negative—no evidence of carcinoma or severe treatment effect. This latter category was histologically characterized by residual, isolated tumor cells or poorly formed glands with abundant clear or vacuolated cytoplasm. Immunohistochemical staining with antibodies to high molecular weight cytokeratin (34BE12, Dako, Carpenteria, California) or to PSA (Biogenex, San Ramon, California) was performed in selected patients when hematoxylin and eosin stains did not clearly distinguish among a treatment effect, treatment related changes in benign glands or a positive diagnosis for active cancer. All positive biopsies were assigned a Gleason grade.

Followup evaluations and PSA measurements after treatment were performed at intervals of 3 to 6 months. Disease status was determined at the time of analysis in July 2007. Median followup in this group of 339 patients was 10 years (range 2 to 18), calculated from the completion of treatment. Median followup in this group of 339 patients was 6.25 years (range 2 to 14), calculated from the completion of posttreatment biopsy. PSA relapse was defined according to the Phoenix consensus definition as an absolute nadir PSA plus 2 ng/ml dated at the call.13 None of the patients received post-irradiation ADT or other anticancer therapy before documentation of a PSA relapse. In patients who had a documented PSA relapse and underwent posttreatment biopsy a complete metastatic evaluation was performed, including bone scan and pelvic magnetic resonance imaging.

Patients were classified into recurrence risk groups according to NCCN guidelines recurrence risk groups (www.nccn.org). The 47 patients at low risk with a median followup of 95 months included those with clinical stages T1–T2a, a Gleason score of 6 or less and pretreatment PSA less than 10 ng/ml. The 149 patients with a median followup of 117 months who had clinical stage T2b or T2c, a Gleason score of 7 or pretreatment PSA 10 to 20 ng/ml were classified as having intermediate risk disease. The 143 patients with a median followup of 113 months who had clinical stage T3a or higher, a Gleason score of 8 or greater, or pretreatment PSA more than 20 ng/ml were classified as having high risk disease.

To determine PSA relapse-free survival, DMFS and cause specific survival outcomes analyses were restricted to 305 patients who did not have evidence of metastatic disease on imaging performed at posttreatment biopsy. For cause specific survival analysis patients with documentation of biochemical or metastatic relapsing disease who subsequently died were scored as a death due to prostate cancer. Distributions of PSA relapse-free survival times were calculated according to the product-limit (Kaplan-Meier) method. Differences between time adjusted incidence rates were evaluated using the Mantel log rank test for censored data. A stepwise Cox-proportional hazards regression model was used to determine the relative impact of covariates affecting time adjusted outcomes.

RESULTS

Overall biopsy outcomes in these 339 patients were positive in 107 (32%), severe treatment effect in 71 (21%) and negative in 161 (47%). The incidence of a positive biopsy according to the prescribed radiation dose level was 65% for less than 70.2 Gy, 38% for 70.2 Gy, 27% for 75.6 Gy and 25% for 81 Gy or greater (table 2). Higher radiation dose levels in the intermediate and high risk groups had a significant influence on the incidence of a positive treatment biopsy. Of patients at intermediate risk who received dose levels of 70.2 Gy or less 21 of 50 (42%) had a positive biopsy compared to 24 of 99 (24%) who received 75.6 Gy or greater (p = 0.03). In the high risk group positive treatment biopsies were noted in 18 of 35 patients (51%) who received 70.2 Gy or less, in 25 of 75 (33%) who received 75.6 Gy and in 5 of 33 (15%) who received 81 Gy or greater (70.2 or less vs 75.6 Gy p = 0.07 and 75.6 vs 81 Gy or greater p = 0.05).

Table 2.

Post-RT prostate biopsy incidence according to various clinical characteristics

| No. Outcome (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group Characteristic | Pos | Treatment Effect | Neg | Totals |

| No. pts | 107 | 71 | 161 | 339 |

| Dose (Gy): | ||||

| 81 or Greater | 26 (25) | 23 (23) | 53 (52) | 102 |

| 75.6 | 38 (27) | 38 (27) | 66 (46) | 142 |

| 70.2 | 26 (38) | 7 (10) | 36 (52) | 69 |

| Less than 70.2 Gy | 17 (65) | 3 (12) | 6 (23) | 26 |

| NCCN risk group: | ||||

| Low | 14 (30) | 9 (19) | 24 (51) | 47 |

| Intermediate | 45 (30) | 27 (18) | 77 (52) | 149 |

| High | 48 (34) | 35 (24) | 60 (42) | 143 |

| NAAD: | ||||

| No | 86 (42) | 40 (19) | 80 (39) | 206 |

| Yes | 21 (16) | 31 (23) | 81 (61) | 133 |

| Biochemical failure: | ||||

| No | 86 (42) | 40 (19) | 80 (39) | 206 |

| Yes | 21 (16) | 31 (23) | 81 (61) | 133 |

Short course NAAD had a significant impact on the post-treatment biopsy outcome. Of patients who did not receive ADT 86 of 206 (42%) had a positive biopsy compared to 21 of 133 (16%) who received ADT (p <0.0001). Table 3 shows the combined influence of the radiation dose level and ADT on posttreatment biopsy outcome. Of patients who received dose levels of 70.2 or less and 75.6 Gy significantly higher positive biopsy rates were observed in those treated with RT alone compared to those treated with RT and ADT (p = 0.05 and 0.0002, respectively). In patients who received 81 Gy or greater biopsy outcomes between those treated with or without ADT were not significant at the p = 0.05 level. Logistic regression analysis identified certain variables predicting for biopsy status, including NAAD (p <0.001) and radiation dose (p = 0.04).

Table 3.

Positive biopsy frequency based on combined influence of radiation dose and ADT

| No. Pos/Total No. (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Dose (Gy) | No NAAD | NAAD | p Value |

| 70.2 or Less | 39/78 (50) | 4/17 (24) | 0.05 |

| 75.6 | 30/76 (39) | 8/66 (12) | 0.0002 |

| 81 or Greater | 17/52 (33) | 9/50 (18) | 0.09 |

Long-Term Outcome According to Posttreatment Biopsy Status

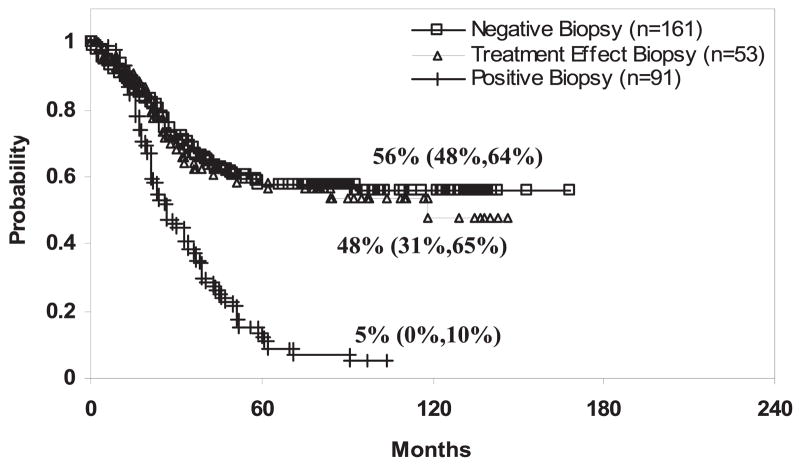

Patients with negative and severe treatment effect biopsies had similar 10-year PSA relapse-free survival outcomes that were markedly different from the outcome of patients with positive treatment biopsies. Ten-year PSA relapse-free survival rates in patients with negative and severe treatment effect biopsy outcomes were 59% (CI 49–68) and 49% (CI 30–68), respectively, while in patients with positive biopsy outcomes the corresponding outcome was 3% (CI −3–9) (each p <0.001, fig. 1). Multivariate analysis indicated that the strongest predictor of biochemical failure was posttreatment biopsy status (positive vs severe treatment effect or negative p <0.001) followed by pretreatment PSA (p = 0.05) and clinical T stage (p = 0.09, table 4).

Fig. 1.

Negative vs positive biopsy p <0.001 and positive vs treatment effect biopsy p <0.001.

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis of biochemical relapse predictors

| Variable | p Value | HR |

|---|---|---|

| Gleason (less than 7 vs 7 or greater) | 0.001 | 1.60 |

| Pretreatment PSA (less than 10 ng/ml vs 10 or greater) | NS | NS |

| Clinical T stage (T1, T2 vs T3) | NS | NS |

| Post-RT biopsy result (neg/treatment effect vs pos) | <0.001 | 2.44 |

| Dose (7,560 Gy or greater vs less than 7,560) | 0.042 | 1.43 |

| Hormones (no vs yes) | NS | NS |

| Age (younger than 65 vs 65 or older) | NS | NS |

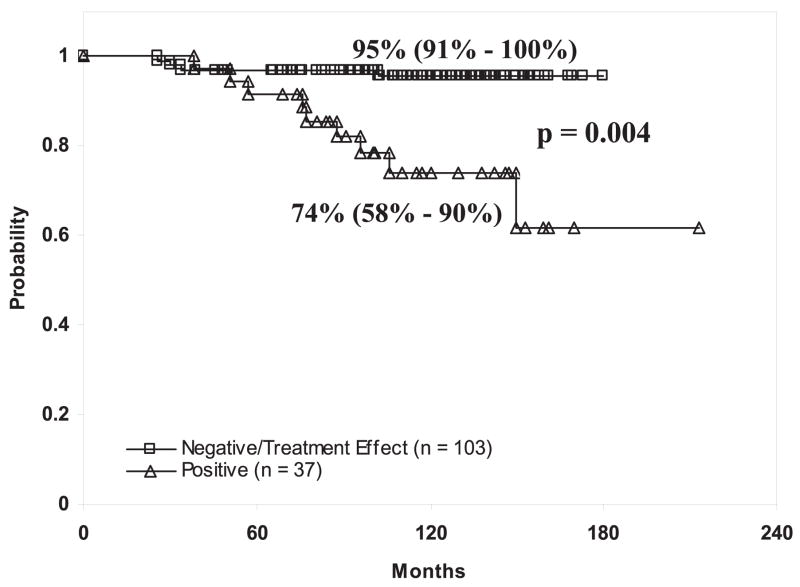

Based on these findings survival outcomes of patients with negative biopsies or severe treatment effect were compared to those of patients with positive biopsies. The 10-year DMFS rate in patients with negative/severe treatment effect biopsy outcomes was 90% (CI 86–95) and the corresponding outcome in patients with positive treatment biopsy outcomes was 69% (CI 58–80, p = 0.0004). These differences appeared most pronounced in patients at intermediate risk. Ten-year DMFS rates in patients at intermediate risk with a negative/severe treatment effect and positive biopsy outcomes were 95% (CI 91–100) and 74% (CI 58–90), respectively (p = 0.0004, fig. 2). In patients at high risk a trend toward increased distant metastasis development was observed in those with positive biopsies. Ten-year DMFS rates in patients with negative/severe treatment effect biopsy outcomes were 80% (CI 70–91) and 57% (CI 40–75) in patients with positive treatment biopsy outcomes (p = 0.08). Multivariate analysis demonstrated that the strongest predictor of distant metastases was the Gleason score (p <0.001), followed by posttreatment biopsy status (severe treatment effect or negative vs positive p = 0.003, table 5).

Fig. 2.

Table 5.

Multivariate analysis of distant Metastasis predictors

| Variable | p Value | HR |

|---|---|---|

| Gleason (less than 7 vs 7 or greater) | <0.001 | 3.99 |

| Pretreatment PSA (less than 10 ng/ml vs 10 or greater) | NS | NS |

| Clinical T stage (T1, T2 vs T3) | NS | NS |

| Post-RT biopsy result (neg/treatment effect vs pos) | 0.003 | 2.39 |

| Dose (7,560 Gy or greater vs less than 7,560) | NS | NS |

| Hormones (no vs yes) | NS | NS |

| Age (younger than 65 vs 65 or older) | NS | NS |

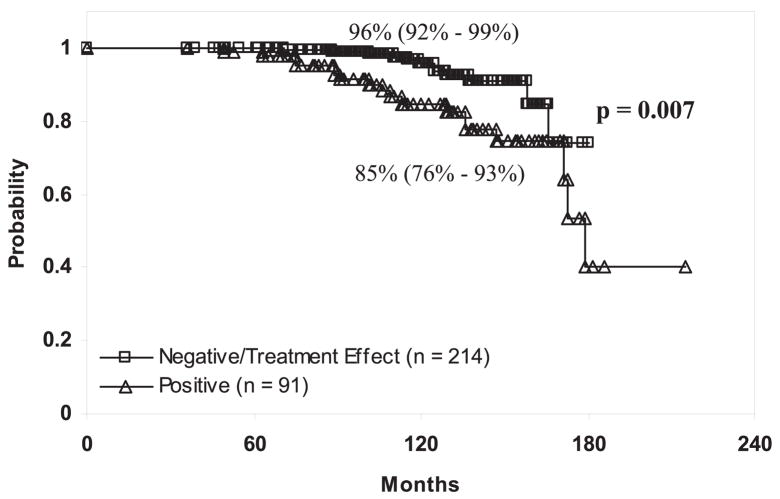

Posttreatment biopsy status was also associated with an increased risk of prostate cancer death. Ten-year cause specific survival rates in patients with negative/severe treatment effect biopsy outcomes were 96% (CI 92–99) and 85% (CI 76–93) in patients with positive treatment biopsy outcomes (p = 0.007, fig. 3). Multivariate analysis demonstrated that the strongest predictor of prostate cancer specific death was the Gleason score (p = 0.001), followed by posttreatment biopsy status (severe treatment effect or negative vs positive p = 0.014) and lastly the radiation dose (p = 0.029, table 6).

Fig. 3.

Table 6.

Multivariate predictors of prostate cancer specific death

| Variable | p Value | HR |

|---|---|---|

| Gleason (less than 7 vs 7 or greater) | 0.001 | 3.70 |

| Pretreatment PSA (less than 10 ng/ml vs 10 or greater) | NS | NS |

| Clinical T stage (T1, T2 vs T3) | NS | NS |

| Post-RT biopsy result (neg/treatment effect vs pos) | 0.014 | 3.30 |

| Dose (7,560 Gy or greater vs less than 7,560) | 0.029 | 0.38 |

| Hormones (no vs yes) | NS | NS |

| Age (younger than 65 vs 65 or older) | NS | NS |

DISCUSSION

Our findings correlating posttreatment biopsy results with 10-year outcomes after external beam RT indicate that local control of prostate cancer had a significant influence on the subsequent risk of distant metastases and prostate cancer related death. In these patients positive biopsy was associated with an almost 3-fold increased risk of distant metastases and a 3.3-fold increased risk of prostate cancer related death. These data lend further support to aggressive local therapeutic interventions for clinically confined prostatic disease. Others have also observed the important association between local tumor control and distant metastasis development. A recent randomized trial comparing patients with clinically localized prostate cancer treated with expectant management and radical prostatectomy demonstrated a significant decrease in distant metastases and a survival advantage in those treated with a definitive local intervention.14

Our data also indicate that the impact of local tumor control was most significant in patients with intermediate and select high risk disease. The implication of these findings is that in patients with low risk, indolent disease a local treatment intervention would not be expected to dramatically influence prostate cancer related mortality because of the inherently low metastatic potential of the disease. In addition, in those with high risk disease who may already harbor micrometastases at diagnosis the impact of local therapy on prostate cancer mortality would be expected to be less pronounced. Our findings in this report are consistent with these observations. In patients at intermediate risk and to a lesser degree patients at high risk a positive biopsy significantly impacted the likelihood of DMFS and prostate cancer related death, while in patients at favorable risk we could not find that a positive biopsy influenced 10-year survival outcomes.

In this report we observed that short course NAAD was associated with a significantly decreased risk of a positive posttreatment biopsy. In patients treated with ADT the incidence of a positive posttreatment biopsy was 15% compared to 41% in those treated with RT alone (p <0.001). Nevertheless, in our report ADT was not an independent variable for improved biochemical and DMFS outcomes. These findings suggest that ADT acts as a radiosensitizer to enhance intraprostatic cell kill and improve local tumor control, which is a notion consistent with other reports.14–16 Biopsy status appears to be a much stronger predictor of outcomes and, when entered into multivariate analysis, it appears to overwhelm ADT as a predictive variable. On the other hand, we agree that it is possible to speculate that ADT may confound posttreatment biopsy results since there may not have been a sufficient duration of exposure for recovered testosterone to stimulate the growth of residual viable cells.

An important finding in this report is that the subsequent clinical outcome in patients with a biopsy finding of adenocarcinoma with a severe treatment effect was similar to that in patients with negative biopsies. In our report all post-treatment biopsies were carefully reviewed and the mentioned stringent criteria were applied to classify positive, negative and treatment effect. Ten-year biochemical control rates in patients with negative biopsies and those with a severe treatment effect overlapped each other and were markedly different than rates in those with positive biopsies. These long-term data are consistent with those in previous reports indicating that more than 80% of patients with posttreatment biopsies demonstrating a severe treatment effect were subsequently negative for tumor on repeated biopsies.9 Based on these data patients with adenocarcinoma with a severe treatment effect in a posttreatment biopsy should not be considered as having residual viable prostate cancer and they should not undergo salvage local therapies.

The relationship of the disease-free survival outcome and biopsy status has also been observed by others. Pollack et al reported that 5-year freedom from relapse in patients with negative biopsies was 84% compared to 60% in those with positive biopsies (p = 0.0002).10 However, these investigators were not able to note that higher doses of 78 Gy were associated with an improved biopsy outcome. Furthermore, in contrast to our findings, they also observed that clinical behavior in patients with adenocarcinoma with a treatment effect was similar to that in patients with positive rather than negative biopsies. However, our findings were based on a larger cohort of patients with 10-year followup observations whose biopsy specimens were evaluated by 1 pathologist in consistent fashion. In addition, it should be noted that of all patients in the current report those with failure documented before the planned prostate period underwent the sextant posttreatment biopsy to assess local tumor control. Nevertheless, efforts were made during followup to perform posttreatment biopsies in all eligible patients who completed treatment 2.5 years previously irregardless of PSA status at the time. Notwithstanding such efforts, since this was not a prospective study, it is likely that there was selection bias to a degree for performing posttreatment biopsy in our patients. We noted differences in the characteristics of patients who underwent posttreatment biopsy compared to the characteristics of those who did not undergo this procedure (table 1). Finally, it is recognized that even sextant biopsies may not always represent adequate sampling of the gland to assess local tumor control. Notwithstanding these limitations these data provide evidence for the fundamental rationale for dose escalation in the treatment of clinically localized prostate cancer, namely that effective local treatment can decrease metastases and cancer related deaths.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ADT

androgen deprivation therapy

- DMFS

distant metastases-free survival

- NAAD

neoadjuvant ADT

- NCCN

National Comprehensive Cancer Network

- NS

not significant

- PSA

prostate specific antigen

- RT

radiotherapy

References

- 1.Pollack A, Zagars GK, Starkschall G, Antolak JA, Lee JJ, Huang E, et al. Prostate cancer radiation dose response: results of the M. D. Anderson phase III randomized trial. Int J Rad Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;53:1097. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02829-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zietman AL, DeSilivio ML, Slater JD, Rossi CJ, Jr, Miller DW, Adams JA, et al. Comparison of conventional dose vs high-dose conformal radiation therapy in clinically localized adenocarcinoma of the prostate: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;294:1233. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.10.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peeters STH, Heembergen WD, Koper PC, van Putten WL, Slot A, Dielwart MF, et al. Dose-response in radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer: results of the Dutch multi-center randomized phase III trial comparing 68 Gy of radiotherapy with 78 Gy. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:19190. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dearnaley DP, Sydes MR, Graham JD, Aird EG, Bottomley D, Cowan RA, et al. Escalated-dose versus standard-dose conformal radiotherapy in prostate cancer: first results from the MRC RT01 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:475. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zelefsky MJ, Fuks Z, Hunt M, Lee HJ, Lombardi D, Ling CC, et al. High dose radiation delivered by intensity modulated conformal radiotherapy improves the outcome of localized prostate cancer. J Urol. 2001;166:2321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuban DA, el-Mahdi AM, Schellhammer PF. Effect of local tumor control on distant metastasis and survival in prostatic adenocarcinoma. Urology. 1987;30:420. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(87)90372-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuks Z, Leibel SA, Wallner KE, Begg CB, Fair WR, Anderson LL, et al. The effect of local control on metastatic dissemination in carcinoma of the prostate: long-term results in patients treated with 125-I implantation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991;21:537. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(91)90668-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crook JM, Perry GA, Robertson S, Esche BA. Routine prostate biopsies following radiotherapy for prostate cancer: results for 226 patients. Urology. 1995;45:624. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(99)80054-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaudin PB, Zelefsky MJ, Leibel SA, Fuks Z, Reuter VE. Histopathologic effects of three-dimensional conformal external beam radiation therapy on benign and malignant prostate tissues. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:1021. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199909000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pollack A, Zagars GK, Antolak JA, Kuban DA, Rosen II. Prostate biopsy status and PSA nadir level as early surrogates for treatment failure: analysis of a prostate cancer randomized radiation dose escalation trial. Int J Rad Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;54:677. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02977-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zelefsky MJ, Leibel SA, Gaudin PB, Kutcher GJ, Fleshner NE, Venkatraman ES, et al. Dose escalation with three dimensional conformal radiation therapy affects the outcome in prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;41:491. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00091-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burman CM, Chui CS, Kutcher GJ, Leibel SA, Zelefsky MJ, LoSasso TJ, et al. Planning, delivery, and quality assurance of intensity-modulated radiotherapy using dynamic multileaf collimator: a strategy for large-scale implementation for the treatment of carcinoma of the prostate. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;39:863. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(97)00458-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Consensus statement: guidelines for PSA following radiation therapy. American Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology Panel. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;37:1035. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zietman AL, Nakfoor BM, Prince EA, Gerweck LE. The effect of androgen deprivation and radiation therapy on an androgen-sensitive murine tumor: an in vitro and in vivo study. Cancer J Sci Am. 1997;3:31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Granfors T, Damber JE, Bergh A, Landstrom M, Lofroth PO, Widmark A. Combined castration and fractionated radiotherapy in an experimental prostatic adenocarcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;39:1031. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(97)00559-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laverdiere J, Gomez JL, Cusan L, Suburu ER, Diamond P, Lemay M. Beneficial effect of combination hormonal therapy administered prior and following external beam radiation therapy in localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;37:247. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(96)00513-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]