Abstract

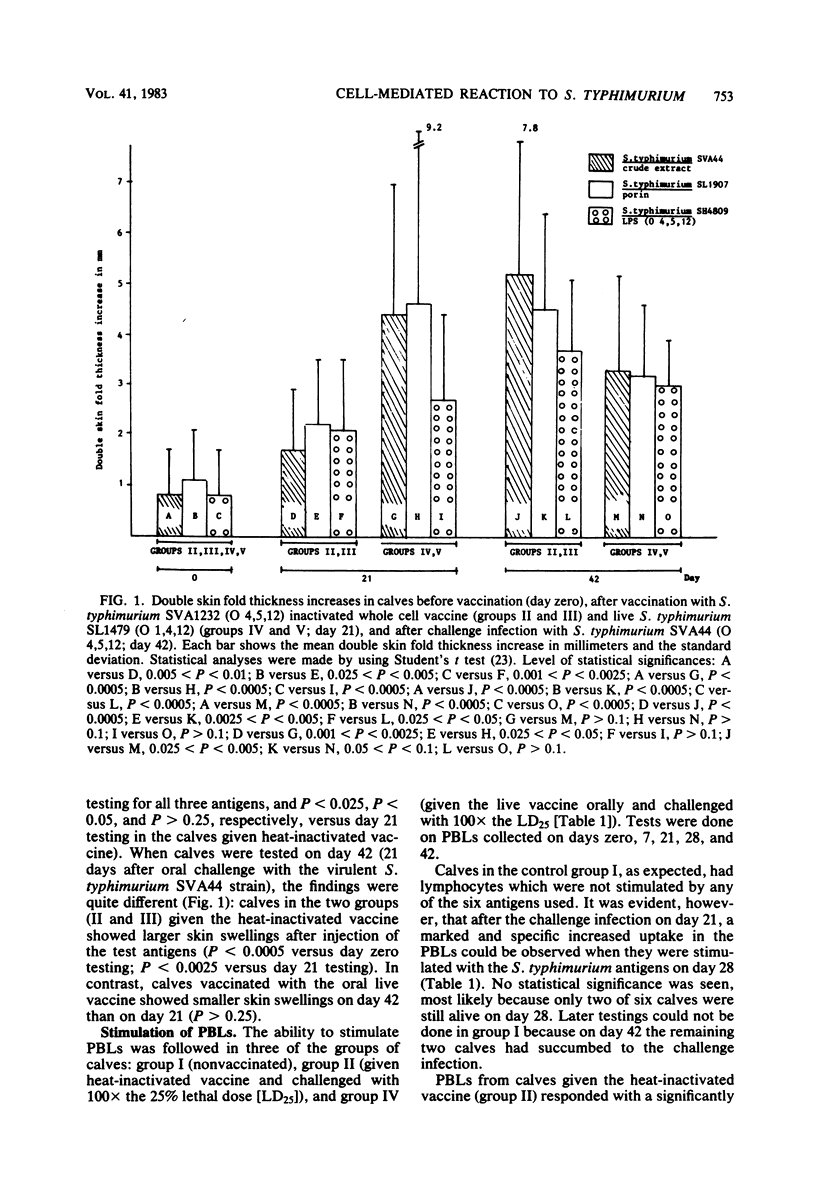

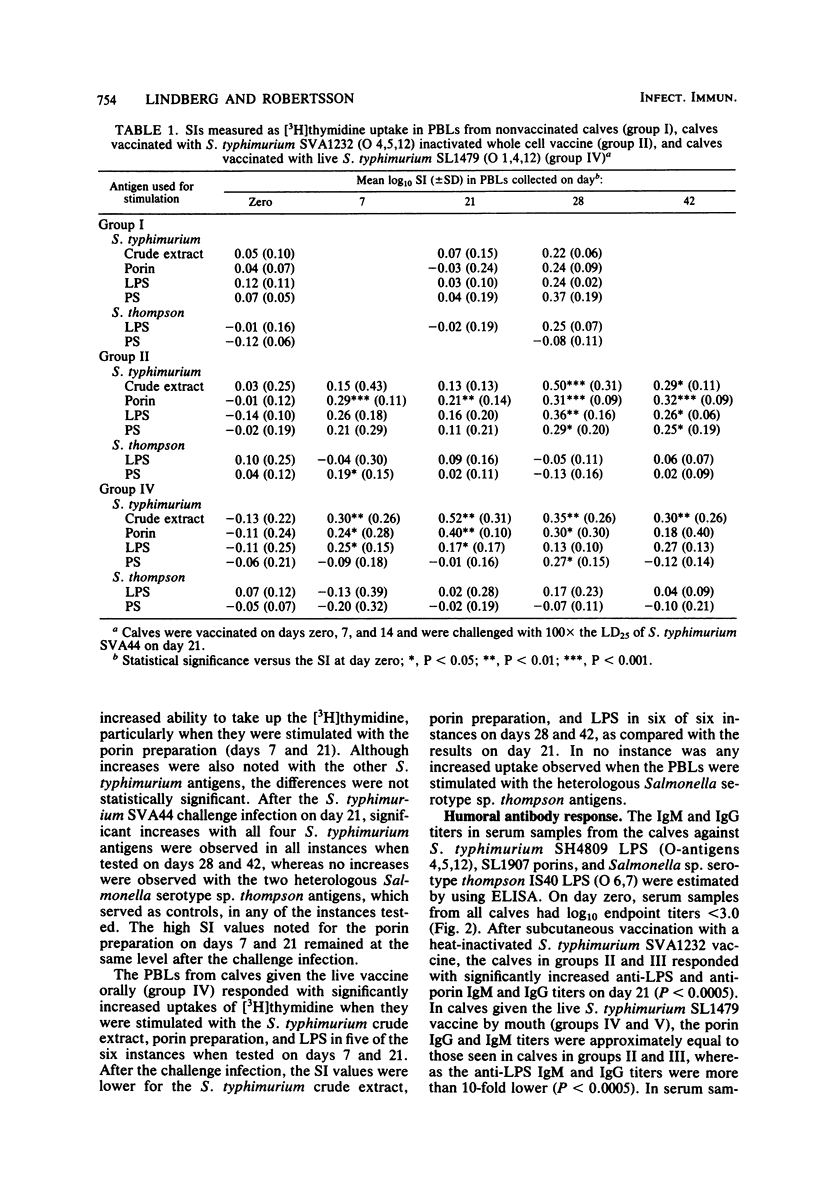

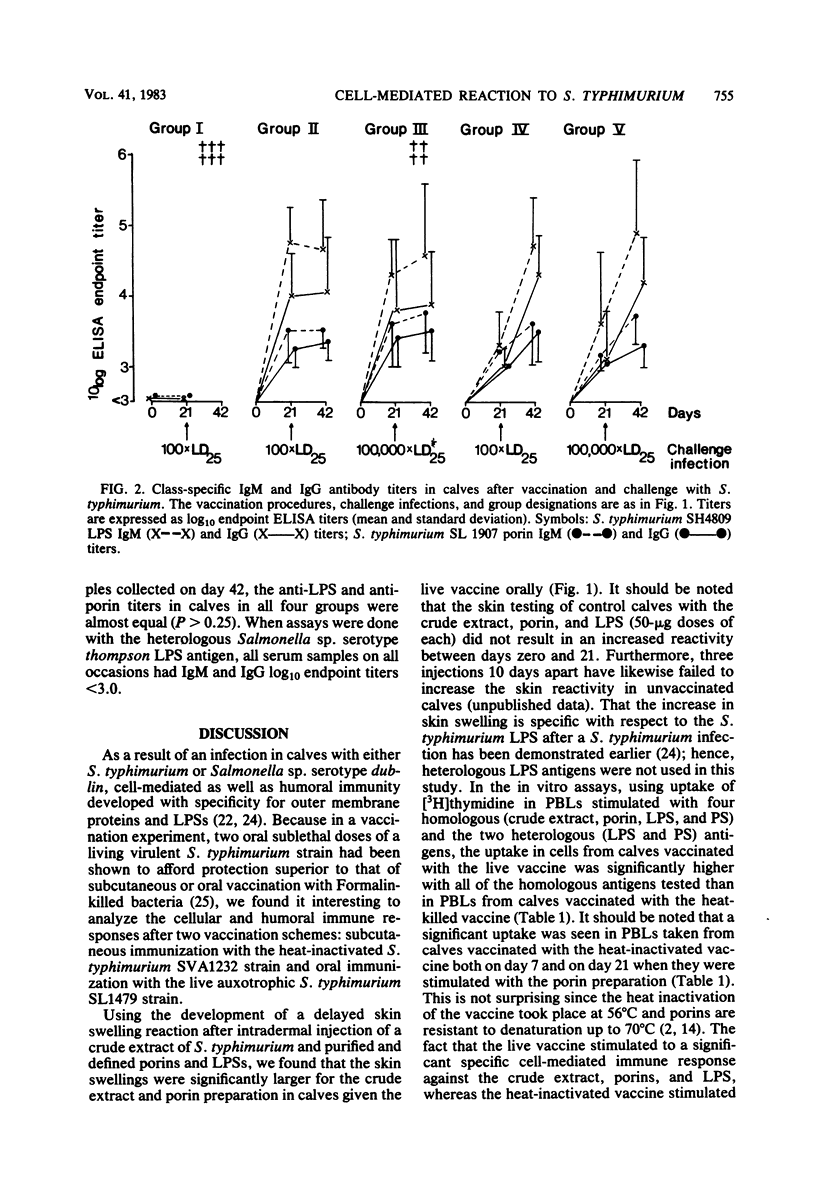

Groups of six calves, 4 to 5 weeks old, were vaccinated either orally with a live auxotrophic Salmonella typhimurium (O-antigen 1,4,12) SL1479 vaccine (10(8) bacteria on day zero, 10(10) bacteria on days 7 and 14) or subcutaneously with a heat-inactivated (56 degrees C, 30 min) S. typhimurium SVA1232 vaccine (10(10) bacteria suspended in 30% [vol/vol] aluminum hydroxide on days zero, 7, and 14). The calves were then orally challenged with either 10(6) (approximately 100 X the 25% lethal dose) or 10(9) (approximately 100,000 X the 25% lethal dose) live bacteria of the calf-virulent S. typhimurium SVA44 strain. The immune reactivity of these calves and of nonvaccinated control calves was followed before and after the challenge infection up to 42 days by (i) intradermal injection of S. typhimurium crude extract, outer membrane protein preparation (porins), and lipopolysaccharide (LPS), (ii) in vitro stimulation of peripheral blood lymphocytes estimated by using uptake of [3H]thymidine, with S. typhimurium crude extract, porins, LPS, and polysaccharide (O-antigenic polysaccharide chain free of lipid A), and Salmonella sp. serotype thompson (O-antigen 6,7) strain IS40 LPS and polysaccharide, and (iii) estimation of the class-specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgM antibody responses against S. typhimurium LPS and porins, and Salmonella sp. serotype thompson LPS. The immune studies showed that in calves given the live vaccine orally, the skin test reactivity and lymphocyte stimulation indices were significantly higher (P values ranging from less than 0.025 to less than 0.0005) against homologous, but not heterologous, antigens than those seen in calves given the heat-inactivated vaccine subcutaneously. In contrast, the IgG and IgM antibody titers against homologous LPS and porins were significantly higher (P less than 0.0005) in sera collected on day 21 from calves given the heat-inactivated vaccine than in calves given the live vaccine. After the oral challenge, calves given the live vaccine showed reduced cell-mediated immune reactions, in agreement with the observation that the host defense could eradicate the challenge organism, whereas calves given the heat-inactivated vaccine showed significantly increased cell-mediated immune reactions (P values ranging from less than 0.025 to less than 0.005), in agreement with the observation that in these calves, the challenge strain caused enteritis as well as systemic invasion. The increased cell-mediated immune reactivity in calves given the live vaccine correlated well with the excellent protection against challenge infection seen in these animals.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Aitken M. M., Jones P. W., Brown G. T. Protection of cattle against experimentally induced salmonellosis by intradermal injection of heat-killed Salmonella dublin. Res Vet Sci. 1982 May;32(3):368–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ames G. F., Spudich E. N., Nikaido H. Protein composition of the outer membrane of Salmonella typhimurium: effect of lipopolysaccharide mutations. J Bacteriol. 1974 Feb;117(2):406–416. doi: 10.1128/jb.117.2.406-416.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bairey M. H. Immunization of calves against salmonellosis. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1978 Sep 1;173(5 Pt 2):610–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi G. C., Sharma V. K. Cell-mediated immunoprotection in calves immunized with rough Salmonella dublin. Br Vet J. 1981 Jul-Aug;137(4):421–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins F. M., Carter P. B. Comparative immunogenicity of heat-killed and living oral Salmonella vaccines. Infect Immun. 1972 Oct;6(4):451–458. doi: 10.1128/iai.6.4.451-458.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins F. M. Vaccines and cell-mediated immunity. Bacteriol Rev. 1974 Dec;38(4):371–402. doi: 10.1128/br.38.4.371-402.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrman J. A., Cebra J. J. Special features of the priming process for a secretory IgA response. B cell priming with cholera toxin. J Exp Med. 1981 Mar 1;153(3):534–544. doi: 10.1084/jem.153.3.534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germanier R. Immunity in experimental salmonellosis. 3. Comparative immunization with viable and heat-inactivated cells of Salmonella typhimurium. Infect Immun. 1972 May;5(5):792–797. doi: 10.1128/iai.5.5.792-797.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman R. H., Hornick R. B., Woodard W. E., DuPont H. L., Snyder M. J., Levine M. M., Libonati J. P. Evaluation of a UDP-glucose-4-epimeraseless mutant of Salmonella typhi as a liver oral vaccine. J Infect Dis. 1977 Dec;136(6):717–723. doi: 10.1093/infdis/136.6.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoiseth S. K., Stocker B. A. Aromatic-dependent Salmonella typhimurium are non-virulent and effective as live vaccines. Nature. 1981 May 21;291(5812):238–239. doi: 10.1038/291238a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornick R. B., Greisman S. E., Woodward T. E., DuPont H. L., Dawkins A. T., Snyder M. J. Typhoid fever: pathogenesis and immunologic control. 2. N Engl J Med. 1970 Oct 1;283(14):739–746. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197010012831406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackaness G. B. Resistance to intracellular infection. J Infect Dis. 1971 Apr;123(4):439–445. doi: 10.1093/infdis/123.4.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemlander A., Soots A., von Willebrand E., Husberg B., Hayry P. Redistribution of renal allograft-responding leukocytes during rejection. II. Kinetics and specificity. J Exp Med. 1982 Oct 1;156(4):1087–1100. doi: 10.1084/jem.156.4.1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien A. D., Metcalf E. S., Rosenstreich D. L. Defect in macrophage effector function confers Salmonella typhimurium susceptibility on C3H/HeJ mice. Cell Immunol. 1982 Mar 1;67(2):325–333. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(82)90224-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien A. D., Scher I., Formal S. B. Effect of silica on the innate resistance of inbred mice to Salmonella typhimurium infection. Infect Immun. 1979 Aug;25(2):513–520. doi: 10.1128/iai.25.2.513-520.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce N. F., Cray W. C., Jr Determinants of the localization, magnitude, and duration of a specific mucosal IgA plasma cell response in enterically immunized rats. J Immunol. 1982 Mar;128(3):1311–1315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce N. F. The role of antigen form and function in the primary and secondary intestinal immune responses to cholera toxin and toxoid in rats. J Exp Med. 1978 Jul 1;148(1):195–206. doi: 10.1084/jem.148.1.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin J. D., Taylor R. J., Newman G. The protection of calves against infection with Salmonella typhimurium by means of a vaccine prepared from Salmonella dublin (strain 51). Vet Rec. 1967 Jun 24;80(25):720–726. doi: 10.1136/vr.80.25.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richman L. K., Graeff A. S., Yarchoan R., Strober W. Simultaneous induction of antigen-specific IgA helper T cells and IgG suppressor T cells in the murine Peyer's patch after protein feeding. J Immunol. 1981 Jun;126(6):2079–2083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertsson J. A., Fossum C., Svenson S. B., Lindberg A. A. Salmonella typhimurium infection in calves: specific immune reactivity against O-antigenic polysaccharide detectable in in vitro assays. Infect Immun. 1982 Aug;37(2):728–736. doi: 10.1128/iai.37.2.728-736.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertsson J. A., Lindberg A. A., Hoiseth S., Stocker B. A. Salmonella typhimurium infection in calves: protection and survival of virulent challenge bacteria after immunization with live or inactivated vaccines. Infect Immun. 1983 Aug;41(2):742–750. doi: 10.1128/iai.41.2.742-750.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertsson J. A., Svenson S. B., Lindberg A. A. Salmonella typhimurium infection in calves: delayed specific skin reactions directed against the O-antigenic polysaccharide chain. Infect Immun. 1982 Aug;37(2):737–748. doi: 10.1128/iai.37.2.737-748.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith B. P., Habasha F. G., Reina-Guierra M., Hardy A. J. Immunization of calves against salmonellosis. Am J Vet Res. 1980 Dec;41(12):1947–1951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welliver R. C., Ogra P. L. Importance of local immunity in enteric infection. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1978 Sep 1;173(5 Pt 2):560–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray C., Sojka W. J., Morris J. A., Brinley Morgan W. J. The immunization of mice and calves with gal E mutants of Salmonella typhimurium. J Hyg (Lond) 1977 Aug;79(1):17–24. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400052803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]