Abstract

Objective

The objective of this review is to determine how frequently likelihood ratios (LRs) have been used or described in the chiropractic literature and to depict their appropriate use in the clinical setting.

Methods

A literature search was conducted of the MEDLINE, Manual Alternative and Natural Therapy Index System, and Index to Chiropractic Literature databases, with search years encompassing 1966 through June 2006. Citations in the English language that addressed the following search terms were retrieved: likelihood ratio in combination with manipulation and chiropractic.

Results

The searches netted a total of 64 citations: 10 in MEDLINE, 34 in the Manual Alternative and Natural Therapy Index System, and 20 in the Index to Chiropractic Literature. After eliminating articles from journals that were not focused specifically on chiropractic, duplicates, and those that did not involve LRs, 3 articles remained and were reviewed. None of the reviewed articles provided a description of LRs, and only 2 used them in a clinical context.

Conclusions

The use of LRs can be very helpful in patient management; however, LRs are rarely reported in the chiropractic literature. Accordingly, chiropractic practitioners are most likely uninformed on the subject and may not have the capacity to use them in formulating diagnoses. It is suggested that researchers increase the reporting of LRs and that chiropractic clinicians begin to make use of them in day-to-day practice.

Key indexing terms: Chiropractic, Likelihood function, Sensitivity, Specificity, Nomogram

Introduction

The use and importance of likelihood ratios (LRs) as an aid in clinical decision making have often been described in the medical and physical therapy literature1-6; however, it is unknown to what extent the topic has been portrayed in the chiropractic literature. The use of LRs in clinical practice can be very helpful because they enable a practitioner to estimate the probability of a patient having a condition after a relevant test has been performed.6

Doctors of chiropractic are in general interested in using clinical tests that have high sensitivity (the ability of a test to correctly identify people who have the target disorder) and high specificity (the ability of a test to correctly identify people who do not have the target disorder). Sensitivity and specificity are expressed as a percentage, with 0% corresponding to the absence of and 100% to perfect sensitivity or specificity.7 When a given test has low sensitivity, people with the target disorder will be missed because of a high number of false negatives; and when a test has low specificity, people who do not actually have the target disorder will be identified as having it because of a high number of false positives. Unfortunately, there is no general agreement about what represents an acceptable level of sensitivity or specificity for a given diagnostic test. Furthermore, what constitutes an acceptable value for sensitivity or specificity is variable, depending upon the clinical situation.6 For instance, acceptable values may be different when the intent of the test or the setting of the test changes, when the prevalence of the condition is dissimilar in the group being tested, or when alternate methods of testing are available.

The LR uses information about sensitivity and specificity to help practitioners choose the best test for a given clinical circumstance. An LR is the probability that the results of a diagnostic test would be expected in a patient with the condition of interest (the test's sensitivity) compared with the expected results of the same test in a patient without the condition (the test's specificity). Thus, the LR is a single index that merges the benefits of both sensitivity and specificity1 and tells the practitioner how much the results of a test will increase or decrease the pretest probability of the condition under consideration.5 Likelihood ratios, together with pretest probabilities, allow one to estimate the probability that a patient will have a condition after the test has been carried out. Information about sensitivity and specificity is important; however, it only describes the capacity of a test to predict whether the patient has a particular condition.

The LR of a positive test (LR+) .is represented by sensitivity/(1 − specificity), and the LR of a negative test (LR−) is (1 − sensitivity)/specificity. In other words, LR+ is a ratio of the probability of a positive test in a person with the condition compared with the probability of a positive test in a person without the condition; and LR− is a ratio of the probability of a negative test in a person with the condition compared with the probability of a negative test in a person without the condition. These ratios can easily be calculated using values for sensitivity and specificity that are often provided in journal articles. The Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM) at the University of Toronto provides a free Stats Calculator online that can be used to calculate sensitivity, specificity, and LRs using data presented in journal articles at http://www.cebm.utoronto.ca/practise/ca/statscal/.8

Because the extent that LRs have been portrayed in the chiropractic literature is unknown, the objective of this review was to determine how frequently they have been used or described in this literature. In addition, an educational update on LRs and a depiction of their appropriate use in the clinical chiropractic setting are provided.

Methods

A literature search was conducted of the PubMed/MEDLINE, Manual Alternative and Natural Therapy Index System (MANTIS), and Index to Chiropractic Literature (ICL) databases, with search years encompassing 1966 through June 2006. Citations in the English language that addressed the following search terms were retrieved: likelihood ratio in combination with manipulation and chiropractic. The search strategy used in PubMed was as follows: likelihood ratio AND (manipulation OR chiropractic). The MANTIS and ICL databases were searched using likelihood ratio, without manipulation or chiropractic. Filters were set in MANTIS and ICL to only retrieve peer-reviewed articles. Full-text articles were obtained and reviewed if they were derived from a chiropractic-focused publication (eg, Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics [JMPT], Chiropractic and Osteopathy, Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association) and in some way used or discussed the LR.

Results

The searches netted a total of 64 citations: 10 from MEDLINE, 34 from MANTIS, and 20 from ICL. After eliminating articles from journals that were not focused specifically on chiropractic, duplicates, and those that did not involve LRs, 3 articles remained and were reviewed.9-11 None of the articles in the chiropractic-specific literature provided a description of LRs, and only 2 articles used them in a clinical context.9,10 Osterbauer et al9 used the LR to describe the ability of 3-dimensional head kinematics and range of motion to distinguish between people with whiplash syndrome and asymptomatic controls. Another article that used the LR was by Humphreys et al,10 who reported on the ability of a Hoffman reflex/maximum muscle activation wave ratio greater than or equal to 0.6 to correctly identify patients with idiopathic low back pain. The third article that used the LR used it in a nonclinical context to describe the probability of finding articles from the JMPT when searching MEDLINE using Medical Subject Headings terms (Table 1).11

Table 1.

Features of articles in the chiropractic literature that have reported LRs

| Author | Objective | Study Design | Results | Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osterbauer et al9 | To Create a Statistical Model Using 3-Dimensional Head Kinematics and Range of Motion to Distinguish Between Whiplash Patients and Asymptomatic Controls | Cross-sectional Study Involving 30 Whiplash Patients and 51 Matched Asymptomatic Controls. Unblinded Comparisons Were Made on Both Outcome Measures. | Biomechanical Abnormalities: | The Biomechanical and Range of Motion Scores Were, for the Most Part, Capable of Differentiating Whiplash Patients From Controls. |

| Sensitivity = 77% | ||||

| Specificity = 82% | ||||

| LR+ = 4.5 | ||||

| Range of Motion: | ||||

| Sensitivity = 77% | ||||

| Specificity = 84% | ||||

| LR+ = 3.9 | ||||

| Humphreys et al10 | To Compare Hoffman Reflexes and Muscle Activation Waves Between Low Back Pain Patients and Healthy Volunteers | Comparative Observational Study of 13 Low Back and/or Leg Pain Patients Compared With 29 Healthy Volunteers | Sensitivity = 2.29 | The Authors Suggest That an H/Mmax* Ratio ≥0.6 Will Correctly Identify 2 of 3 Patients With Idiopathic Low Back Pain. |

| LR+ = 3.04 | ||||

| Perle11 | To Investigate the Accuracy of Indexing of Chiropractic-Generated or -Related Research in MEDLINE Using Articles Published in JMPT as the Sample | Literature Search | Specificity = 82.93% | The Indexing of Chiropractic Research in MEDLINE for Articles Published in JMPT Was Not Accurate, Making It Difficult to Identify Appropriate Chiropractic Literature in Searches. |

| Sensitivity = 58.45% | ||||

| LR+ = 3.423 | ||||

| LR- = 0.501. |

Hoffman reflex/maximum muscle activation wave.

Discussion

Likelihood ratios can be used in combination with pretest probabilities to improve the probability that the proper test is used for a specific patient. The pretest probability of a patient having a suspected condition is usually estimated by the practitioner after the patient's initial assessment. It represents how likely it is that the patient has the target disorder before performing the test. Pretest probability is based on the clinician's experience, the prevalence of the condition, and sometimes the published literature. It may be modified up or down for a given patient in the presence of risk factors.5 One should keep in mind, however, that there is little scientific evidence supporting the clinical application of this approach and that there is wide variability in practitioners' pretest probability estimates.12,13

The pretest probability can be combined with the LR to generate a posttest probability, such that a high pretest probability coupled with a high LR will generate a very high posttest probability. Hence, a practitioner who was reasonably confident about a correct diagnosis before the test would be much more confident after obtaining the positive results of a test that had a high LR. The opposite of this scenario would occur if a low pretest probability and low LR were involved.

Given a positive test, when the calculated LR is greater than 1, the probability that the condition is present is increased; when the LR is less than 1, the probability that the condition is present is decreased; and when the LR is equal to 1, the probability that the condition is present vs not being present is the same.14 Jaeschke et al15 categorized the ranges of possible LR values and described the implications for each category as follows:

-

•LR >10 or <0.1

- Generates large and conclusive changes in the probability of a given diagnosis.

-

•LR in the range of 5 to 10 or 0.1 to 0.2

- Generates a moderate and usually important change in the probability of a given diagnosis.

-

•LR in the range of 2 to 5 or 0.5 to 0.2

- Generates a small but sometimes important change in the probability of a given diagnosis.

-

•LR in the range of 1 to 2 or 0.5 to 1

- Changes the probability of a given diagnosis to a small and rarely important degree.

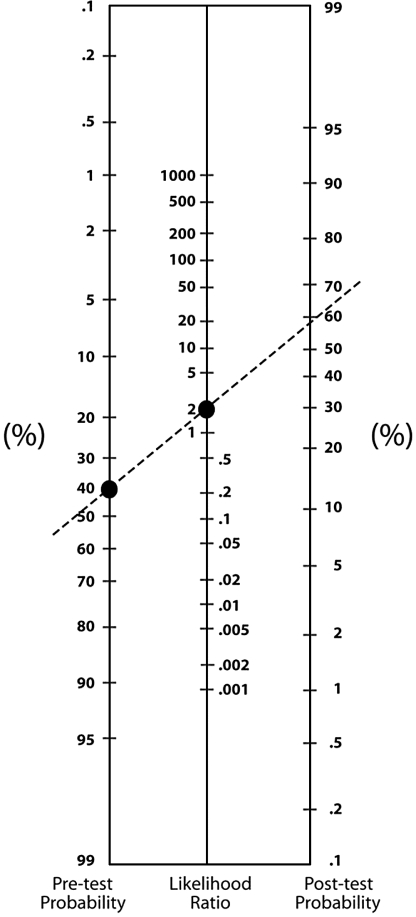

Fagan16 devised a nomogram that can be used to quickly convert pretest probabilities to posttest probabilities using LRs (Fig 1). To use the nomogram, first locate the patient's pretest probability on the left side of the nomogram; then locate the test's LR on the middle line. Draw a line between the located pretest probability and LR, and then extend this line until it passes through the posttest probability on the right side of the nomogram. This point becomes the new estimate of the probability that the patient has the condition. An online interactive nomogram is available at the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine http://www.cebm.net/nomogram.asp.17

Fig 1.

Nomogram showing that a pretest probability of 40% and an LR of 2 result in a posttest probability of 58%. Copyright 1975, Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved. With permission.

Fig 1 also illustrates an example of how to use a nomogram. In this hypothetical case, with a pretest probability of 40% and an LR of 2, the broken line extending through these points passes through the posttest probability at approximately 58%. Accordingly, the test provides some useful information that makes the clinician a little more confident that the diagnosis is correct; but another test is needed to confirm it.

Likelihood ratios have been referred to as the most useful single indicator of the diagnostic strength of a test.18 They can be used by clinicians to help make decisions about the necessity of further testing and when to begin appropriate treatment. Moreover, if the posttest probability of a test is very high, it is very likely that the condition is present and treatment should be initiated. On the other hand, if the posttest probability is very low, the condition may be ruled out and no further diagnostic or therapeutic action would be necessary. Likelihood ratios can also be used in sequence so that the posttest probability derived from one diagnostic test can be used as the pretest probability for the next.5

Information derived from performing a test should be beneficial to the patient and have the potential to result in a change in the way his or her condition is managed.19 When the pretest probability is not changed after considering a test's LR, the new test would likely be unnecessary and should not be administered. In another patient with a different case presentation, however, the same test might be useful.

As an example, there is a fair chance that a patient with lower back pain radiating to the posterior thigh may have S-1 radiculopathy. Before examination, a practitioner may estimate the pretest probability for such a patient as 30%. On examination, the straight leg raise (SLR) test is positive; but how confident can one be that this finding is predictive of radiculopathy in this case? A study by Vroomen et al20 investigated the relationship between the SLR test and lumbosacral nerve root compression causing sciatica as determined by magnetic resonance imaging. Out of 274 patients with leg pain, a positive SLR was present in 97 of those with nerve root compression and 53 without; also, a negative SLR was present in 55 with nerve root compression and 69 without. These values were plugged into the online CEBM calculator mentioned above to derive the following statistics and 95% confidence intervals in parenthesis:

-

•

Sensitivity = 0.638 (0.559-0.71)

-

•

Specificity = 0.566 (0.477-0.65)

-

•

LR+ = 1.469 (1.161-1.859)

-

•

LR− = 0.64 (0.492-0.832)

The calculated LR+ of 1.5 does not change the probability of the diagnosis very much. In fact, using this LR with the Fagan nomogram, the pretest probability of 30% is only raised to about 40% posttest. Additional testing is therefore indicated, but now using a pretest probability of 40%. The presence of paresis was the most specific reported predictor of nerve root compression in the study of Vroomen et al, with an LR+ of 4.1. Thus, if this same patient exhibited paresis, the resulting posttest probability would be approximately 75%. One would be highly suspicious of nerve root compression at this point, but further testing would be necessary to confirm the diagnosis (eg, magnetic resonance imaging or electromyography). If, in addition, the patient's knee or ankle tendon reflex was absent, which has a reported LR+ of 2.2, the new posttest probability would be nearly 90% (Fig 2).

Fig 2.

Lines on a nomogram representing serial pretest-posttest probabilities of lumbar nerve root compression that consider (A) a positive SLR test, (B) the presence of paresis, and (C) an absent tendon reflex. Each successive posttest probability becomes the next pretest probability.

The use of pretest probabilities and LRs is not that difficult, yet can be very helpful in patient management. However, based on this literature review, it is apparent that LRs are rarely reported in the chiropractic literature. Consequently, practitioners are most likely uninformed on the subject and do not have the capacity to use them in formulating diagnoses. It is suggested that researchers increase the reporting of LRs and that chiropractic clinicians begin to make use of them in day-to-day practice. One should keep in mind that not all databases were searched and only English-language journals were considered in this review. As a result, some relevant chiropractic studies that involved LRs may have been overlooked.

References

- 1.Davidson M. The interpretation of diagnostic test: a primer for physiotherapists. Aust J Physiother. 2002;48:227–232. doi: 10.1016/s0004-9514(14)60228-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giard R.W., Hermans J. Interpretation of diagnostic cytology with likelihood ratios. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1990;114:852–854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Radack K.L., Rouan G., Hedges J. The likelihood ratio. An improved measure for reporting and evaluating diagnostic test results. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1986;110:689–693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gallagher E.J. Clinical utility of likelihood ratios. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;31:391–397. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(98)70352-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaeschke R., Guyatt G.H., Sackett D.L. Users' guides to the medical literature. III. How to use an article about a diagnostic test. B. What are the results and will they help me in caring for my patients? The Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1994;271:703–707. doi: 10.1001/jama.271.9.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riddle D., Stratford P. Interpreting validity indexes for diagnostic tests: an illustration using the Berg balance test. Phys Ther. 1999;79:939–948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sackett D.L. The rational clinical examination. A primer on the precision and accuracy of the clinical examination. JAMA. 1992;267:2638–2644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. [home page on the Internet]. Toronto: The Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, c2004. Stats calculator. [1 screen]. Available from: http://www.cebm.utoronto.ca/practise/ca/statscal/.

- 9.Osterbauer P.J., Long K., Ribaudo T.A. Three-dimensional head kinematics and cervical range of motion in the diagnosis of patients with neck trauma. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1996;19:231–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Humphreys C.R., Triano J.J., Brandl M.J. Sensitivity study of H-reflex alterations in idiopathic low back pain patients vs. a healthy population. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1989;12:71–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perle S. Searching for chiropractic literature: a study of MEDLINE indexing of the Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics. J Chiropr Educ. 2006;20:88. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Phelps M.A., Levitt M.A. Pretest probability estimates: a pitfall to the clinical utility of evidence-based medicine? Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:692–694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Attia J.R., Balakrishnan R.N., Sibbritt D.W. Generating pre-test probabilities: a neglected area in clinical decision making. Med J Aust. 2004;180:449–454. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2004.tb06020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strauss S.E. Evidence-based medicine: how to practice and teach EBM. 3rd ed. Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone; Edinburgh: 2005. pp. 84–87. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaeschke R.Z., Meade M.O., Guyatt G.H., Keenan S.P., Cook D.J. How to use diagnostic test articles in the intensive care unit: diagnosing weanability using f/Vt. Crit Care Med. 1997;25:1514–1521. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199709000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fagan T.J. Letter: nomogram for Bayes theorem. N Engl J Med. 1975;293:257. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197507312930513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. [home page on the Internet]. Oxford: The Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, c2006. Nomogram for using likelihood ratios. [1 screen]. Available from: http://www.cebm.net/nomogram.asp.

- 18.Worster A., Innes G., Abu-Laban R. Diagnostic testing: an emergency medicine perspective. Can J Emerg Med. 2002;4:348–354. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500007764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haynes B., Sox H. Quantitative aspects of clinical decision making: medical decision analysis. ACP medicine. Vol. 2006. WebMD Professional Publishing; Danbury (CT): 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vroomen P.C.A.J., de Krom M.C.T.F.M., Wilmink J.T., Kester A.D.M., Knottnerus J.A. Diagnostic value of history and physical examination in patients suspected of lumbosacral nerve root compression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;72:630–634. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.72.5.630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]