Abstract

Objective

To describe a case regarding a woman with 2-level cervical disk herniation with radicular symptoms conservatively treated with chiropractic care including high-velocity, low-amplitude (HVLA) manipulation with complete resolution of her symptoms.

Clinical Features

A 40-year-old woman developed right finger paresthesia and neck pain. Results of electrodiagnostics were normal, but clinical examination revealed subtle findings of cervical radiculopathy. A subsequent magnetic resonance imaging revealed a large right posterolateral disk protrusion and spur impinging on the right hemicord with moderate to severe central canal and right neuroforaminal stenosis at C5-6 and C6-7. She was treated with HVLA manipulation to the cervical spine, as well as soft tissue techniques, traction, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and exercise.

Intervention and Outcome

Her clinical findings and symptoms resolved within 90 days of initiating care and did not return in 1 year. There were no untoward effects, including transient ones.

Conclusion

This case describes the clinical presentation and course of a patient with multilevel large herniated disks and associated radiculopathy who was treated with HVLA manipulation and other conservative approaches and appeared to have good outcomes.

Key indexing terms: Radiculopathy; Manipulation, Chiropractic; Cervical spine; Intervertebral disk displacement; Neck pain

Introduction

Neck pain is a common complaint, affecting approximately 13% to 18% of the general population; and doctors of chiropractic provide manipulative services approaching 200 million visits for neck-related complaints in the United States every year.1 One in 5 chiropractic visits is for neck pain.2 Up to 15% of women and 10% of men are affected by chronic neck pain.3 Various authors have reported that chiropractic manipulative therapy (CMT) is both safe and effective for cervical complaints as well as for cervical radiculopathy.1,4-8

There however remains controversy regarding the efficacy of manipulation for neck-related conditions. Vernon et al,3 after reviewing various clinical trials, concluded that “…the differential benefit of manual therapies compared with other non-manual therapies has been shown, at present, to not be consistently substantial, and that the inclusion of manual therapies among other therapies appears to produce optimal outcomes.” They did however feel that there was moderate- to high-quality evidence of efficacy for spinal manipulative therapy or mobilization for a subgroup of chronic neck pain patients.3

Rubenstein et al9 recently reported on a multicenter prospective cohort study involving 529 patients with neck pain, noting 56% of patients reported “adverse events” after 1 to 3 visits. Symptoms described as mild included increased pain, headaches, radiation of pain, as well as other symptoms such as dizziness, “tiredness,” nausea, or ringing in the ears. However, of 4891 treatments, only 1% reported being worse at the end of the treatment trial; half the cohort was recovered after 4 visits, and approximately two thirds were recovered at 3 and 12 months. The authors concluded that the benefits of chiropractic care outweighed the risks.9

Murphy et al10 recently reported on a series of 27 patients with cervical cord compression. They noted that the role of CMT in the treatment of radiculopathy was unclear and cited authors who felt that CMT was contraindicated in such patients based in part on reports of purported complications from the treatment. They felt that those conclusions were largely unsupportable based on serious design flaws and noted no serious complications and no increase in pain lasting more than 4 days in their series. Acknowledging that spinal cord or nerve root injury was possible from CMT and advising caution and consideration of non–high-velocity, low-amplitude (HVLA) approaches in some patients, Murphy et al nevertheless concluded that “Findings of cervical spinal cord encroachment on MRI [magnetic resonance imaging] should not be considered an absolute contraindication to cervical manipulation, provided the manipulation is applied by an appropriately trained and experienced practitioner, and is performed with the utmost care and skill.” He advocated using a provocative “premanipulative position” before manipulation, moving slowly to the “restrictive barrier”; and if “peripheralization” of symptoms is noted, another direction of manipulation is sought.10

Cervical radiculopathy has been defined as an abnormality of a nerve root that originates in the cervical spine11 resulting from compression and inflammation of nerve root or roots in proximity to the neuroforamen.12 It has an annual incidence of approximately 85 per 100 000,11,12 is more common in men than women, and has a peak incidence in the sixth decade of life.11

The most common cause of cervical radiculopathy is disk herniation, followed by spondylosis, with or without myelopathy. Less common causes include intraspinal or extraspinal tumors, nerve root avulsion secondary to trauma, meningeal or synovial cysts, arteritis, cerebral palsy, or vascular abnormalities.12,13 It can also occur with no apparent cause.11,13 The differential diagnoses includes idiopathic brachial plexopathy, local disorders of the shoulder, upper limb entrapment neuropathies, and, when accompanied by myelopathy, syringomyelia and motor neuron disease.13 Clinically, it most commonly presents with pain, often described as sharp, lancinating, achy, or burning, in the neck, shoulder, arm, or chest, depending on the root or roots involved, usually in a myotomal distribution. Arm pain is more common than neck pain.11-13 Sensory changes, such as paresthesias and numbness, are more common than loss of motor strength or reflex changes, although the sensory examination is less reliable because of dermatomal overlap12,13 Citing multiple authors, Ellenberg et al13 report that “ Eighty to 100% of patients will present with neck and arm pain with or without motor weakness or paresthesia, generally not preceded by trauma or other determinable precipitating cause.” The C7 root is most commonly affected, followed by C6.11-13

After a careful history and routine neurologic assessment, clinical evaluation should note sensory loss, tone, strength, and bulk of muscles and reflexes. Provocative maneuvers may be observed that stretch the nerve root, such as coughing, sneezing, Valsalva, cervical distraction, and the Spurling maneuver. Consideration of possible myelopathy should be given, particularly with cervical spondylosis; and symptoms of generalized sensory disturbances, limb stiffness, bladder or bowel incontinence, general clumsiness, or history of frequent falls warrants further evaluation. Possible examination findings of myelopathy include hyperreflexia, increased tone or spasticity, extensor toe signs, or other pathological reflexes suggestive of an upper motor neuron lesion.11 Plain films are useful in screening, particularly for spondylosis, although MRI is considered the criterion standard. Myelography and computed tomography are also frequently used.11,12,13 Electrodiagnostic testing, including nerve conduction velocities and needle electromyography (EMG), is frequently used, although its usefulness varies.11 Results of EMG may be normal in patients with mild radiculopathy or a mostly sensory disorder,11 and EMG studies should be delayed until at least 3 to 4 weeks after symptom onset.13

Most cases of radiculopathy, as much as 80% to 90%, resolve with conservative care, although the true nature of its natural history is not clear, owing largely to the lack of standardization in diagnostic criteria and lack of high-quality studies.11,13 Conservative treatment options generally include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication, activity modification, traction, epidural injections, and physical therapy modalities. There are currently no high-quality studies comparing outcomes between the various conservative approaches, or between surgical and nonsurgical approaches.11,13

This paper describes a case of MRI-documented multilevel herniation with encroachment treated with HVLA manipulation with no apparent untoward sequelae.

Case report

A 40-year-old right-handed accounting clerk for a water company had a 1-week history of right elbow pain and forearm pain with progressive right shoulder pain and increasing numbness of the right index finger, which she collectively rated 7 on a 0 to 10 numerical rating scale. The patient spent up to 40 hours a week doing data entry, a position she had held for 9 years. Frequently, she would spend hours turning checks over as she inputs them with a 10-key. Her symptoms began shortly after her workstation setup was altered. She initially specifically denied neck pain, but did note pain in the right upper trapezium extending to the right shoulder. She reported a prior history of forearm tendonitis 7 years previously, with complete resolution after conservative treatment. She also noted a history of a minor-impact rear-end motor vehicle accident approximately 3 months before the onset of symptoms. She denied any pain or treatment subsequent to that accident.

Active cervical range of motion (ROM) and shoulder ROM were grossly intact with the exception of pain on cervical right lateral flexion at end-range. Axial compression was essentially negative for localized pain and never produced radicular symptoms. Results of Spurling test, Valsalva, and Soto-Hall were negative. Cervical distraction aggravated her trapezius pain. Results of all orthopedic testing of the shoulder were normal. Grip strength in the right upper extremity was reduced by 40% compared with the left as measured by dynamometer; but the result of the neurologic examination, except for mild hypoesthesia and decreased vibratory and 2-point discrimination sense in a mostly C6 distribution on the right, was unremarkable. She denied any lower extremity symptoms or symptoms of myelopathy and exhibited normal gait.

Radiographic examination of the cervical spine including anteroposterior (AP) and lateral views revealed only mild to moderate midcervical degenerative changes. The neuroforamina were patent, the intervertebral disks appeared generally well preserved, and there was a loss of cervical lordosis. Her initial Bournemouth Neck Disability score was 21%.

The initial impression in this work-related case was of overuse syndrome with a mild cervical strain superimposed on mild to moderate cervical degeneration and myofascial involvement of the neck and right upper extremity. Conservative care included HVLA manipulation to T1 and C5-6 coupled with myofascial release techniques (ischemic compression, postisometric relation, and stretching) to the forearm and upper trapezius. She had improvement after treatment, but only modest improvement overall, initially. In view of her persistent finger numbness, negative results of clinical testing for carpal tunnel syndrome (results of Durkan, Tinel, and Phalen tests were normal), atypical trigger point referral trajectory, and potential cervical etiology, as well as the pattern of numbness and a high index of suspicion, she was referred for electrodiagnostic testing and neurologic consult and was seen within a month of the onset of symptoms.

Electrodiagnostic studies, including motor and sensory nerve conduction velocity studies of the median, ulnar, and radial nerves, and cervical paraspinal and extremity muscle EMG were interpreted as normal; but the neurologist's clinical examination revealed subtle signs suggesting possible “C5-6 radiculitis.” He appreciated some mild limitations in ROM of the neck, reduced sensation over the distal second digit, a possibly reduced triceps reflex, and positive foramenal compression on the right. He suspected a cervical radiculopathy and prescribed Tylenol (Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, NJ) with codeine as well as ibuprofen.

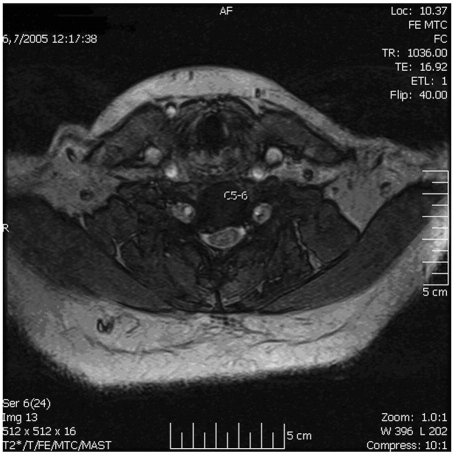

The MRI (Figs 1-3) revealed a large right posterolateral disk protrusion and spur impinging on the right hemicord without intrinsic cord signal. Severe stenosis of the entry zone to the right neuroforamen was noted at C5-6 with moderate central canal and right neuroforaminal stenosis. The left neuroforamen was also mildly narrowed at C5-6. At C6-7, there was a large right posterolateral disk protrusion and spur that compressed the right hemicord without intrinsic cord signal. There was moderate to severe central canal stenosis, compromise of the entry zone to the right neuroforamen, and moderate to severe right neuroforamenal stenosis. Bilateral uncovertebral hypertrophy was also noted. There was no evidence of cord edema or gliosis.

Fig 1.

T2-weighted sagittal image. Note disk herniation at C5-6 measuring 5 mm AP × 13 mm transverse.

Fig 2.

T1-weighted sagittal image. Disk herniation at C6-7 measures 5 mm AP × 14 mm transverse.

Fig 3.

Axial image demonstrating large cervical disk herniation.

Chiropractic treatment including HVLA (“diversified”) manipulation was applied to the T1 and C5-6 level, in conjunction with home cervical static traction. She noted immediate, although transient, improvement of her trapezius pain with manipulation, and steady resolution of her forearm myofascial complaints after myofascial ischemic compression and stripping, but no change initially in her finger paresthesia. Traction initially increased her arm symptoms but later was felt to be helpful. She was also instructed in specific stretching exercises (“chin-tucks,” upper trapezius stretches with postisometric relaxation, and gentle cervical ROM). She was placed on temporary disability.

After approximately 15 visits, she began to have noticeable improvement in her trapezius pain and finger paresthesia. After 20 treatments over an 8-week period, she noted resolution of her forearm pain and 70% improvement of her neck discomfort, as well as significant improvement of her finger paresthesia. In view of her prior symptoms and MRI findings, and at the request of the insurer (this was a worker's compensation case), a referral for neurosurgical consultation was made. The neurosurgeon saw her approximately 3 months after the onset of symptoms and reported that he thought that the patient had experienced a possible Lhermitte phenomena while she was watching television. He felt she had decreased reflexes, decreased grip and wrist extensor strength, and reduced C6-7 sensation. He recommended surgical decompression.

A second surgical opinion was sought, although the patient was rather adamantly opposed to any surgery. By 90 days after her initial presentation, she essentially denied any further subjective complaints. No neurologic deficits were appreciated. Her Bournemouth score was 0. Despite the negative result of the neurologic examination, the second surgeon who saw her 1 month later nevertheless reported she would likely require future surgery, which she also declined. The patient returned to work with ergonomic modifications and was seen in follow-up approximately 1 year later with no further complaints of neck pain or upper extremity symptoms.

Discussion

Despite symptomatic MRI-documented large cervical disk-osteophyte complexes with extremity radiculopathy, this patient's subjective complaints and neurologic findings completely resolved after a course of conservative manual therapy that included HVLA and soft tissue manipulation as well as home-based traction and mild nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

The clinical presentation of cervical radiculopathy will vary depending on a variety of factors, including the nerve root level involved and the extent of encroachment on the involved level.13 Although surgery remains one treatment option, various authors have suggested nonsurgical approaches, including cervical traction,11,13-17 and manual therapies, including HVLA manipulation, among others.10,18-20 The efficacy and safety of HVLA in the treatment of these patients are still controversial, and there are reported cases in the literature of serious sequelae from cervical spine manipulation.10

The present report describes a patient with documented cervical disk herniation and radicular findings who was deemed a surgical case by 2 respected neurosurgeons. Her reflex and motor strength loss was fairly subtle, although her sensory symptoms were fairly persistent. As noted, sensory complaints predominate in radiculopathies; and motor and reflex changes may not be present.12,13 Results of electrodiagnostic studies were normal, although, as Abbed and Coumans12 point out, fibrillation and positive sharp waves may not be evident early in the clinical course and EMG findings may be normal in a primarily sensory radiculopathy. It is possible that her negative electrodiagnostic results may in part be due to having her testing done so early in the course of her condition. Fortunately for this patient, she achieved complete clinical resolution of her symptoms without having to undergo more invasive care; and she remained asymptomatic more than 1 year in follow-up.

Despite admonitions to the contrary from some authors,13 manipulation has been used with apparent efficacy in cervical radiculopathy cases. Murphy et al,10 following a series of 27 patients with cervical cord encroachment treated with manipulation, suggested that spinal manipulation was not absolutely contraindicated, although cautious patient selection, clinical reasoning, and technique selection were recommended. Unfortunately, research is still not definitive on true complication and risk rates from manipulation with which to make informed comparisons to other treatment approaches. Likewise, definitive efficacy comparisons between conservative approaches and between surgery and nonsurgical methods are also lacking.11,13

However, a comparison of estimated serious complication rates from the various treatment approaches suggests that CMT is a reasonable option. Although mild or transient symptoms after CMT is fairly common,21 the risk of vertebral artery injury and potential for cerebrovascular insult has been estimated at between 1 in 500 000 to 1 in 1 million22 and 1 in 5.85 million.23 In contrast, Gabriel et al24 estimated the risk of serious gastrointestinal complications related to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory use to be as high as 8 in 100; and Graham25 found the risk for serious neurologic complications from posterior approach cervical surgery to be as high as 5.65 per 100. Death rates for CMT are estimated to be 1/100 to 1/400 for those who use nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and the death rate is estimated to be 1/700 for cervical surgery.26 Issues of efficacy aside, CMT clearly appears to be a much safer intervention.

This patient's clinical presentation held some diagnostic challenges. She initially denied neck pain, other than upper trapezius pain; and her forearm pain was subjectively and clinically consistent with a localized myofascial condition. In fact, the consulting neurologist also agreed that the forearm pain was a localized condition; and her forearm symptoms resolved after appropriate conservative local management including rest, ergonomic modifications, anti-inflammatory medication, and soft tissue techniques. Although subtle, this patient's symptoms were also consistent with radiculopathy, including a primary complaint of arm pain, upper trapezius pain, persistent numbness in the second digit, and subtle signs of motor weakness and reflex changes. Neck pain is not always present in radiculopathy and is not the most common symptom, and radiculopathy can be present even without motor or reflex changes.11-13 Presentation with arm pain as a primary complaint with paresthesia, even absent neck pain, is consistent with the literature. Abbed and Coumans,12 citing a large series by Henderson, noted the presence of arm pain in 99.4% of patients, compared with neck pain found in 79.7%.

This case does have a number of limitations. First, aside from her initial pain level, the symptoms were relatively mild and the clinical neurologic findings were subtle, with a normal nerve conduction and EMG study result. It is also possible that the herniations were not the cause of her symptoms at all. Nevertheless, the MRI findings were fairly impressive and sufficient, in combination with the physical examination findings, to convince 2 experienced neurosurgeons of the need for surgery, although that is not necessarily diagnostic validation. Second, the diagnostic workup could have been more complete. The lack of subjective complaints of lower extremity symptoms and normal gait led the author, the neurologist, and both neurosurgeons to essentially skip a more thorough examination to rule out myelopathy, including testing for extensor toe signs, lower extremity sensory or motor loss, or other signs or symptoms that might suggest myelopathy.

In addition, it is not possible to conclusively determine whether the patient's symptoms resolved as a consequence of natural history, the over-the-counter anti-inflammatory medication, the traction, the manipulation, or some combination thereof. Cervical radiculopathy generally improves with conservative care in most cases.11 The ibuprofen was low dose, in the range of 400 mg 2 to 3 times daily taken sporadically, and therefore unlikely to be the sole or primary therapeutic factor. The literature as noted demonstrates some efficacy for traction, but this patient failed to note improvement with an over-the-door unit and reported only modest relief from a Pronex supine static traction unit (Glacier Cross Inc., Kalispell, MT). There is no definitive evidence that the HVLA manipulation was the primary therapeutic agent either, although arguably it was the most aggressive of the therapeutic interventions the patient received and what the patient credited for her recovery. Certainly, bias cannot be eliminated in that regard.

The patient reported no untoward effects and no complaints of increased pain or worsening of clinical findings, even transiently, which would seem to provide additional evidence at least in this case that HVLA manipulation, even in the presence of multiple large disk herniations, is safe. In addition, as Polston11 notes, progressive neurologic deficits have been shown to improve with conservative care, suggesting that those alone may not be an indication for surgery; and he notes that a 2001 Cochrane Database of Systematic Review found no differences in outcome at 1 year between patients treated surgically versus those treated conservatively. Additional high-quality studies comparing relative risk rates and relative efficacy rates between CMT, other conservative care, and surgical intervention for cervical radiculopathy are needed. In addition, larger trials including CMT for cervical radiculopathy would do much to address both the efficacy and safety issues surrounding CMT and cervical radiculopathy.

Conclusion

This case describes the clinical presentation and course of a patient with multilevel large herniated disks and associated radiculopathy with apparent resolution of symptoms after treatment with HVLA manipulation and other conservative approaches. At 1 year follow-up, no untoward effects were noted.

Acknowledgment

The author thanks Kathleen M Flores-Dahms, MD, MRI medical director at Regents MRI, La Jolla, CA, for her assistance with the MRI images.

References

- 1.Haneline M.T. Chiropractic manipulation and acute neck pain: a review of the evidence. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005;28(7):520–525. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gay R.E., Madson T.J., Cieslak K.R. Comparison of the neck disability index and the neck Bournemouth questionnaire in a sample of patients with chronic uncomplicated neck pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2007;30(4):259–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vernon H., Humphreys K., Hagino C. Chronic mechanical neck pain in adults treated by manual therapy: a systematic review of change scores in randomized clinical trials. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2007;30(3):215–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alcantara J., Plaugher G., Thornton R.E., Salem C. Chiropractic care of a patient with vertebral subluxations and unsuccessful surgery of the cervical spine. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2001;24(7):477–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murphy D.R., Hurwitz E.L., Gregory A., Clary R. A nonsurgical approach to the management of patients with cervical radiculopathy; a prospective observational cohort study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29(4):279–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy D.R. Herniated disc with radiculopathy following cervical manipulation: nonsurgical management. Spine J. 2006;6(4):459–463. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2006.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tatarek N.E. Variation in the human cervical neural canal. Spine J. 2005;5(6):623–631. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.BenEliyahu D.J. Magnetic resonance imaging and clinical follow-up. Study of 27 patients receiving chiropractic care for cervical and lumbar disc herniation. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1996;19(9):597–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rubenstein S.M., Leboeuf-Yde C., Knol D.L., Koekkoek T.E., Pfeifle C.E., van Tulder M.W. The benefits outweigh the risks for patients undergoing chiropractic care for neck pain: a prospective, multicenter, cohort study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2007;30(6):408–418. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murphy D.R., Hurwitz E.L., Gregory A.A. Manipulation in the presence of cervical spinal cord compression: a case series. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29(3):236–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Polston D.W. Cervical radiculopathy. Neurol Clin. 2007;25(2):373–385. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abbed K.M., Coumans J.V. Cervical radiculopathy: pathophysiology, presentation, and clinical evaluation. Neurosurg. 2007;60(1):S1 28–S1 34. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000249223.51871.C2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellenberg M.R., Honet J.C., Treanor W.J. Cervical radiculopathy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1994;75(3):342–352. doi: 10.1016/0003-9993(94)90040-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Constantoyannis C., Konstantinou D., Kourtopoulos H., Papadakis N. Intermittent cervical traction for cervical radiculopathy caused by large-volume herniated disks. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2002;25(3):188–192. doi: 10.1067/mmt.2001.123356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brouillette D.L., Gurske D.T. Chiropractic treatment of cervical radiculopathy caused by a herniated cervical disc. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1994;17(2):119–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moeti P., Marchetti G. Clinical outcome from mechanical intermittent cervical traction for the treatment of cervical radiculopathy: a case series. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2001;31(4):207–213. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2001.31.4.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saal J.S., Saal J.A., Yurth E.F. Nonoperative management of cervical herniated intervertebral disc with radiculopathy. Spine. 1996;21(16):1877–1883. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199608150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kruse R.A., Imbarlina F., De Bono V.F. Treatment of cervical radiculopathy with flexion distraction. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2001;24(3):206–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pollard H., Hansen L., Hoskins W. Cervical stenosis in a professional rugby league football player: a case report. Chiropr Osteopat. 2005;13:15. doi: 10.1186/1746-1340-13-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dougherty P., Bajwa S., Burke J., Dishman J.D. Spinal manipulation postepidural injection for lumbar and cervical radiculopathy: a case series. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2004;27(7):449–456. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hurwitz E.L., Aker P.D., Adams A.H., Meeker W.C., Shekelle P.G. Manipulation and the mobilization of the cervical spine: a systematic review of the literature. Spine. 1996;21:1746–1760. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199608010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee K.P., Carlini W.G., McCormick G.F., Albers G.W. Neurologic complications following chiropractic manipulation: a survey of California neurologists. Neurology. 2005;45(6):1213–1215. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.6.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haldeman S., Carey P., Townsend M., Papadopoulos C. Arterial dissections following cervical manipulation: the chiropractic experience. CMAJ. 2001;165(7):905–906. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gabriel S.G., Jaakimainen L., Bombadier C. Risk for serious gastro-intestinal complications relative to use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. A meta-analysis. Ann Int Med. 1991;115(10):787–796. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-10-787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Graham J.J. Complications of cervical spine surgery—a five-year report on a survey of the membership of the Cervical Spine Research Society by the Morbidity and Mortality Committee. Spine. 1989;14(10):1046–1050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosner A.L. Adverse reactions to chiropractic care in the UCLA neck pain study: a response. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29(3):248–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]