Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Appendicitis is the most common cause of the acute abdomen and can affect all age groups. Most patients recover quickly but a minority can suffer postoperative complications. This case-note review was undertaken to assess the frequency of these complications.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Adult patients (> 16 years) undergoing an emergency appendicectomy at a University teaching hospital between February 2004 and January 2005 were identified from pathology records. Details of operative procedure, histology and postoperative complications were noted from the hospital case notes

RESULTS

A total of 199 patients with a median age of 31 years (range, 16–89 years) were identified. Of these, 58 (29%) patients experienced a postoperative complication. Eight (4%) patients were admitted to the surgical high dependency unit or intensive care unit postoperatively and there was one death (0.5%). Re-operation for a postoperative complication was required in 9 (4.5%) patients and there was a 13% re-admission rate (26 patients). Comparison between patients with histologically proven appendicitis (164 patients; 82%) and those patients having a negative appendicectomy (35 patients; 18%) showed no significant difference in the rate of complications as defined (43 of 164, 26% versus 15 of 35, 43%; P = 0.08). However, patients with positive histology were more likely to experience a septic complication (29 of 164, 18% versus 1 of 35, 3%; P = 0.028) and all re-operations came from this group. Despite this, patients with a negative appendicectomy were more likely to be re-admitted (12 of 35, 34% versus 14 of 164, 8.5%; P = 0.0002), predominantly with persistent abdominal pain.

CONCLUSIONS

Appendicectomy is associated with a significant morbidity. Patients with an inflamed appendix were more likely to experience a septic complication but re-admission was more common in patients with a histologically normal appendix because of unresolved abdominal pain.

Keywords: Acute appendicitis, Appendicectomy, Complications, Outcome

Appendicitis is the most common abdominal surgical emergency and there are approximately 40,000 cases in the UK per annum.1 The treatment of choice is appendicectomy and trials have suggested that, although the laparoscopic approach may have some advantages, there is no clear benefit of this over the open approach.2 As a consequence, the method of appendicectomy is often dictated by operator experience and facilities available. The majority of recent studies on the management of patients having an appendicectomy are from within the confines of a clinical trial and, due to selection criteria, do not reflect the whole patient case load undergoing the procedure. Most patients recover quickly from appendicectomy but a minority can suffer postoperative complications. This review of case notes was undertaken to assess the frequency of these complications in unselected patients.

Patients and Methods

Adult patients (> 16 years of age) undergoing an emergency appendicectomy in the 12-month period between 1 February 2004 and 31 January 2005 were identified from a key word search of ‘appendix’ from pathology and theatre record databases. Details of presenting symptoms, time to operation, operative procedure, histology and postoperative complications were obtained from the patients' case notes. A complicated recovery was assumed to have occurred if a patient did not recover in the conventional manner. This was defined by the presence of a complication which prolonged the postoperative stay for > 4 days, admission to a critical care area and/or the need for re-operation or re-admission. Complications were divided into septic (i.e. infective) or non-septic depending on the nature and aetiology.

Data were collected and entered into a Microsoft Access database and statistical analysis performed using SPSS for Windows v.9.0. Data are expressed as median (range) and interquartile range (IQR) where specified.

Results

A total of 199 patients were identified and all the case notes were reviewed. The median age of the patients was 31 years (range, 16–89 years) and 110 (55%) were male. Fifty-eight patients (29%) experienced a postoperative complication. Eight (4%) patients were admitted to the surgical high dependency unit or intensive care unit postoperatively and there was one death (0.5%). Re-operation for a postoperative complication was required in 9 (4.5%) patients and there was a 13% re-admission rate (26 patients). The median length of stay for all patients was 3 days (range, 1–44 days; IQR, 2.25–5).

Of the 199 patients, 164 (82.4%) had acute appendicitis proven on histological examination and 35 (17.6%) had a histologically normal appendix. Of the inflamed group, 23% (37/164) were found to be perforated, either intra-operatively or histologically. There was no statistically significant difference in the complication rate between patients with an inflamed appendix (43 of 164, 26.2%) compared with those with a normal appendix (15 of 35, 42.9%; P = 0.78 chi-squared test with Yates' correction). However, patients with positive histology were more likely to experience a septic complication than those who had normal histology (29 of 164, 17.7% versus 1 of 35, 2.9%; P = 0.028, Fisher's exact test) and all re-operations came from the former group. The most common septic complication was wound infection (Table 1) and half these came from patients with a perforated appendix. The only septic complication from the uninflamed group was persistent pyrexia in a patient who subsequently grew Pseudomonas spp. from an interoperative peritoneal aspirate.

Table 1.

Septic complications in the inflamed group

| Complication | Patients (n) |

|---|---|

| Wound infection | 11 |

| Generalised sepsis | 7 |

| Intra-abdominal collection | 4 |

| Chest infection | 4 |

| Diarrhoea | 2 |

| Orchitis | 1 |

Non-septic complications from the inflamed group are shown in Table 2. Thirteen cases of continued abdominal pain and one subsequent diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease account for the non-septic complications from the uninflamed group.

Table 2.

Non-septic complications in the inflamed group

| Complication | Patients (n) |

|---|---|

| Pain | 3 |

| Prolonged ileus | 3 |

| Left ventricular failure | 2 |

| Constipation | 2 |

| Urinary retention | 2 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1 |

| Wound haematoma | 1 |

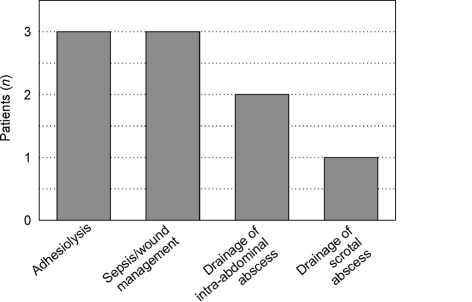

Re-operation for a postoperative complication was required in 9 of 199 (4.5%) patients and there was a 13% re-admission rate (26 of 199 patients). In total, there were 17 additional procedures performed on 9 patients all of whom were found to have a perforated appendix with pus in the peritoneal cavity at their initial operation. The reasons for re-operation are shown in Figure 1. The repeat procedures were performed on two patients for intra-abdominal sepsis and wound management, one of whom required skin grafting.

Figure 1.

Re-operations.

When categorised into 12-h periods for the first 4 days and for 24-h periods thereafter, the median duration from onset of symptoms to admission was 12–24 h (IQR 0–6 to 42–48 h). There was no observed statistical relationship between the duration of symptoms and occurrence of a postoperative complication (P = 0.62, chi-squared test).

With respect to pre-operative investigations, 78% patients with histologically proven appendicitis had a raised white cell count (> 11 × 109 cells/l) compared with only 19% of patients with normal histology (P < 0.0001, chi-squared test with Yates' correction). The C-reactive protein was raised (> 10 mg/l) in 84% and 9%, respectively (P < 0.0001, chi-squared test with Yates' correction). Pre-operative imaging (other than a plain abdominal radiograph) was used in 54 (27.1%) patients (47 abdominal and pelvic ultra-sound scans and 7 abdominal CT scans). For patients who were found to have histologically positive diagnosis of appendicitis, pre-operative ultrasonography was positive in only 7 cases (20.6%) and had positively ruled out appendicitis in 2 of 36 (5.5%). CT scan findings were suggestive of appendicitis in all 7 cases.

The median duration of time from admission to the operating theatre was 17.5 h (IQR, 11.9 – 25.2 h). A total of 175 (88%) appendicetomies were performed within 40 h of admission and these accounted for 54 (93%) of the complications. When the duration of time from admission to operation was categorised into 8-h periods, there were 12 complications out of 27 appendicetomies for the first 8 h, 23 of 63 for 8–16 h, 14 of 59 for 16–24 h, none of 19 for 24–32 h and 5 of 8 for 32–40 h (P = 0.04, chi-squared analysis).

Operatively, 66% (131) of cases were undertaken laparoscopically initially, although 1 in 6 (22) of these were converted to an open procedure, predominantly due to technical difficulties. Some 27% (54) were done as a primary open procedure using a traditional grid-iron or Lanz incision and 5% (10) underwent mid-line laparotomy. Only 2% (4) had an initial diagnostic laparoscopy followed by an open appendicectomy. Three patients required right hemicolectomy for phlegmonous masses and five incidental carcinoid tumours were noted. There was no significant difference in complication rate between open (28 of 90, 31.1%) and laparoscopic (30 of 109, 27.5%) surgery (P = 0.57, chi-squared test). All patients noted to have an inflamed appendix intra-operatively had at least one dose of intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Only 4% (8 of 199) patients were admitted to the surgical high dependency unit or intensive care unit postoperatively. The median age of patients admitted to ITU/HDU was 39.5 years (range, 18–61 years) and their median pre-operative ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists) classification was 1E (range 1E–3E). Their median stay in a critical care area was 10.5 days (range, 4–44 days). The primary reason for admission in three patients was systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), the remainder were admitted for ventilatory support. The predominant feature in all these patients was a perforated appendix with free pus in the peritoneal cavity. Multi-organ failure secondary to SIRS/MODS (multi-organ dysfunction syndrome) led to the death of one 44-year-old patient from this group (mortality 0.5%).

Patients with a histologically normal appendix were more likely to be re-admitted (12 of 35, 34.2% versus 14 of 164, 8.5%; P < 0.0002, Fisher's exact test), predominantly with persistent abdominal pain (see Table 3). The median time to re-admission within this group was 14 days (range, 7–70 days) and the median duration of the second admission was 4 days (range, 2–9 days).

Table 3.

Reasons for re-admission

| Reason | Inflamed group (n) | Uninflamed group (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Wound infection | 6 | |

| Persistent pain | 3 | 11 |

| Intra-abdominal abscess | 2 | |

| Ileus | 1 | |

| Shortness of breath | 1 | |

| Constipation | 1 | |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 1 |

Discussion

This case-note review demonstrates that emergency appendicectomy for suspected appendicitis is associated with a significant complication rate. Predictably, patients with positive histology were more likely to experience a septic complication but re-admission is more common in patients with negative findings.

Although the incidence of appendicitis is thought to be falling,3 almost 200 adult appendicectomies were performed over the 12-month period at our institution which serves a population of 350,000. It can be seen that it is a condition that can affect all ages but is most common in patients aged less than 30 years.

Nearly a third of patients in our review had a complicated postoperative recovery. The type of complication was influenced by the operative findings and severity of disease. Patients with a positive histology were predictably more likely to experience a septic complication and, furthermore, those with free pus in the peritoneal cavity or a gangrenous appendix were more likely to run a more unpredictable postoperative course. Indeed, all patients admitted to the critical care beds postoperatively had such findings which was often associated with a longer history and greatly increased inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein > 200 mg/l) and the age range of this group (30–60 years) indicates that it not only the elderly who suffer significant morbidity from this condition.

The diagnosis of appendicitis is primarily a clinical one but can be supported by the presence of a raised white cell count (in particular a raised neutrophil count) and C-reactive protein,4 as over 80% of people with positive histology had levels above the normal range.

Computed tomography has a high sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis.5 However, as the investigation requires significant radiation exposure, it should be used with caution and is rarely required to make a diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Ultrasonography, by contrast, is more operator dependent and less accurate in the diagnosis of appendicitis.6 This is clearly demonstrated in our study as it only provided a positive diagnosis in 20% of inflamed cases and was falsely negative in 5%.

There was a significant relationship between the duration of time from admission to operation and complications. Most complications occurred in patients undergoing operation within the first 24 h but this is likely just a reflection of the finding that most appendectomies were done during this time with our median time to theatre of 17.5 h. It should be acknowledged that correlating waiting times for theatre and complications can be inaccurate in retrospective studies as the urgency for theatre is based on individual clinical need, the sickest patients quite understandably being taken to the operating theatre the soonest. However, we would recommend that once a diagnosis of appendicitis is made, appendicectomy should be performed without any unnecessary delays.

The majority of appendicectomies were performed laparoscopically and mostly by trainees who were deemed capable of performing the procedure independently. Although the primary aim of this uncontrolled review was not to compare laparoscopic versus open appendicectomy, we found no significant difference in complication rates between the two procedures. We can see the difficulty in performing trials in this area as stratification is needed to control for the disease process.

We would anticipate that the number of laparoscopic cases to increase as experience in the procedure increases. Although studies have also found that laparoscopic surgery increased postoperative intra-abdominal abscesses compared with open surgery, several other randomised controlled trials provided evidence that laparoscopic appendicectomy in adults reduces wound infections, postoperative pain, duration of hospital stay, and time taken to return to work compared with open surgery.2 Laparoscopy also has the benefit of being able to visualise other intra-abdominal organs if there is diagnostic doubt and the investigation of non-specific abdominal pain with diagnostic laparoscopy has been shown to be beneficial in certain group of patients.7

Furthermore, the use of laparoscopy as a diagnostic test is likely to decrease the number of negative appendicectomies. Historically, during open appendicectomies, surgical trainees have been taught to remove a normal appendix to eliminate any diagnostic difficulties at a later date. Our data show that only 4 of 35 patients fell into this category compared with the historical figures of between 20–25%. There is some support, however, for removing the grossly normal appendix in people with recurrent right iliac fossa pain as studies have suggested that there may be subtle alterations in the enteric nerves in such appendices which may underlie the symptoms.8 The finding that there was on-going pain in many people with a normal histology tends to suggest that it is not wholly beneficial although the study does demonstrate the low incidence of operative complications following removal of a grossly normal appendix and it also removes appendicitis from the list of possible future diagnoses if patients are re-admitted.

The re-admission rate for the uninflamed group is significantly higher and represents a considerable workload. One in three patients were re-admitted compared with 1 in 11 for the inflamed group and re-admission occurred within 3 weeks of discharge in all but one patient. This group is typically represented by young females and, during re-admission, no organic cause for the symptoms were found in any patient despite repeated investigation in many cases. It is difficult to advocate a management plan for these patients as they can represent a significant diagnostic challenge but it may be beneficial to offer early out-patient follow-up postoperatively to reduce the re-admission rate.

This review does not make recommendations for the management of appendicitis, but does raise the issue that this is a common condition and operative intervention does carry a significant degree of morbidity and, indeed, mortality. There is a wide spectrum of complications that patients experience and, arguably, the complications that the patients experience are a reflection of the extent of initial appendicitis rather than the result of having an appendicectomy. Our review does highlight particular factors which can be important in predicting the type of complication that patients experience.

Conclusions

Appendicectomy is associated with a significant complication rate. Predictably, patients with positive histology were more likely to experience a septic complication but re-admission because of unresolved abdominal pain is more common in patients with negative findings.

References

- 1.<http://www.hesonline.org.uk/Ease/servlet/ContentServer?siteID=1937&categoryID=204>

- 2.Simpson J, Speake W. Appendicitis. Clin Evidence. 2005:529–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kang JY, Hoare J, Majeed A, Williamson RC, Maxwell JD. Decline in admission rates for acute appendicitis in England. Br J Surg. 2003;90:1586–92. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersson RE. Meta-analysis of the clinical and laboratory diagnosis of appendicitis. Br J Surg. 2004;91:28–37. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pinto Leite N, Pereira JM, Cunha R, Pinto P, Sirlin C. CT evaluation of appendicitis and its complications: imaging techniques and key diagnostic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:406–17. doi: 10.2214/ajr.185.2.01850406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Terasawa T, Blackmore CC, Bent S, Kohlwes RJ. Systematic review: computed tomography and ultrasonography to detect acute appendicitis in adults and adolescents. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:537–46. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-7-200410050-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Decadt B, Sussman L, Lewis MP, Secker A, Cohen L, Rogers C, et al. Randomized clinical trial of early laparoscopy in the management of acute non-specific abdominal pain. Br J Surg. 1999;86:1383–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1999.01239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Di Sebastiano P, Fink T, di Mola FF, Weihe E, Innocenti P, Friess H, et al. Neuroimmune appendicitis. Lancet. 1999;354:461–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10463-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]