Abstract

The hippocampal formation (HF) is involved in modulating learning related to drug abuse. While HF-dependent learning is regulated by both endogenous opioids and estrogen, the interaction between these two systems is not well understood. The mossy fiber (MF) pathway formed by dentate gyrus (DG) granule cell axons is involved in some aspects of learning and contains abundant amounts of the endogenous opioid peptide dynorphin (DYN). To examine the influence of ovarian steroids on DYN expression, we used quantitative light microscopic immunocytochemistry to measure DYN levels in normal cycling rats as well as in two established models of hormone-treated ovariectomized (OVX) rats. Rats in estrus had increased levels of DYN-immunoreactivity (ir) in the DG and certain CA3 lamina compared to rats in proestrus or diestrus. OVX rats exposed to estradiol for 24 hrs showed increased DYN-ir in the DG and CA3, while those with 72 hrs estradiol exposure showed increases only in the DG. Six hrs of estradiol exposure produced no change in DYN-ir. OVX rats chronically implanted with medroxyprogesterone also showed increased DYN-ir in the DG and CA3. Next, dual-labeling electron microscopy (EM) was used to evaluate the subcellular relationships of estrogen receptor (ER) α-, ERβ and progestin receptor (PR) with DYN-labeled MFs. ERβ-ir was in some DYN -labeled MF terminals and smaller terminals, and had a subcellular association with the plasmalemma and small synaptic vesicles. In contrast, ERα-ir was not in DYN-labeled terminals, although some DYN-labeled small terminals synapsed on ERα-labeled dendritic spines. PR labeling was mostly in CA3 axons, some of which were continuous with DYN-labeled terminals. These studies indicate that ovarian hormones can modulate DYN in the MF pathway in a time-dependent manner, and suggest that hormonal effects on the DYN-containing MF pathway may be directly mediated by ERβ and/or PR activation.

Keywords: dentate gyrus, CA3, estrogen, progestin, estrous cycle, opioid

INTRODUCTION

Ovarian hormones such as estrogen can enhance drug seeking behavior (Carroll et al., 2004), other forms of associative learning (Zurkovsky et al., 2007), and vulnerability to seizures (Woolley and Schwartzkroin, 1998) (Woolley, 2000; Scharfman and MacLusky, 2006). Since the hippocampal formation (HF) has been implicated in all of these processes (Berke and Hyman, 2000), it is important to better understand the role of ovarian hormones in this structure. One relevant hippocampal neuromodulator that may be influenced by ovarian hormones is the endogenous opioid peptide dynorphin (DYN). Rodent studies suggest a role for dynorphin in the regulation of several hippocampal processes. Specifically, endogenous DYN and kappa-opioid receptor agonists function to inhibit perforant path –granule cell excitation as well as recurrent excitation in the dentate gyrus and are, therefore, broadly thought to decrease excitability and inhibit LTP formation (Wagner et al., 1991; Caudle et al., 1991; Weisskopf et al., 1993; Terman et al., 2000). The precise role of DYN in HF physiology is more complex, however, as in some circumstances DYN demonstrates dual effects on CA3 excitatory synaptic currents, increasing currents at low DYN concentrations and decreasing currents at high DYN concentrations (Caudle et al., 1994). Behaviorally, spatial learning is impaired by administration of DYN or specific kappa-opioid receptor agonists into the hippocampus (McDaniel et al., 1990; Sandin et al., 1998). Prodynorphin knockout mice show a significantly reduced seizure threshold, which can be reversed by infusion of a specific kappa-opioid receptor agonist (Loacker et al., 2007). Moreover, dysphoria produced by common behavioral stressors is absent in prodynorphin knockout mice with a mechanism dependant on the kappa-opioid receptor (Land et al., 2008). Thus DYN effectively modulates LTP, seizure vulnerability, and drug seeking-associated learning behaviors in the hippocampus.

Both drugs of abuse and several forms of excitation influence hippocampal DYN. For example, cocaine exposure during the prenatal period affects striatal prodynorphin levels in female adolescent rats (Torres-Reveron et al., 2007). The increase in prodynorphin produced by cocaine can be prevented by the administration of estrogen or progesterone alone, but not in combination, to adult ovariectomized female rats (Jenab et al., 2002). Additionally, many reports have shown that seizure activity produces specific time-dependent effects on DYN peptide levels in the hippocampus (Gall, 1988; Simonato and Romualdi, 1996; de Lanerolle et al., 1997; Pierce et al., 1999). For example, 48 hrs after experimentally induced seizure, dynorphin-B immunoreactivity (ir) decreases in the dorsal but increases in the ventral mossy fiber pathway (Pierce et al., 1999).

Gonadal steroids modulate DYN levels in several brain areas, with some evidence for direct targeting of DYN-containing neurons. In the rat adenohypophysis, prodynorphin expression increases following ovariectomy and reverts to normal with estradiol replacement (Fullerton et al., 1988; Spampinato et al., 1995). In the neurohypophysis magnocellular system, estradiol administration increases DYN content only in vasopressin containing neurons (Levin and Sawchenko, 1993). In the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus of female rats in proestrus (the high-estrogen phase of the estrous cycle), nearly all prodynorphin immunoreactive neurons also have nuclei co-expressing estrogen receptor (ER) α (Burke et al., 2006). In the preoptic region, prodynorphin is lowest in rats in proestrus and highest during estrus, and prodynorphin containing neurons co-express mRNA for both ERs and progestin receptors (PRs) (50% and 85%, respectively; Simerly et al., 1996). Similarly, in the ewe, about 90 % of DYN neurons in the preoptic area, anterior hypothalamus, and arcuate nucleus also co-express PRs (Foradori et al., 2002). Although it is well known that DYN-containing cells in the hypothalamus play a key role in regulating the negative feedback of progesterone on several other hormones (Foradori et al., 2002; Goodman et al., 2004), regulatory interactions between progesterone and hippocampal DYN have not yet been studied. A recent study reported estrous cycle-dependent fluctuations in the cleavage of DYN peptide to smaller peptides in the rat HF, but unfortunately lacked regional specificity (Roman et al., 2006).

Most hippocampal DYN is found in the mossy fiber pathway in the hilus of the dentate gyrus (DG) and CA3 regions (McGinty et al., 1983; Drake et al., 2007). The α and β subtypes of ER show an extranuclear distribution that overlaps with the mossy fiber pathway in both the dentate hilus and CA3 region (Shughrue et al., 1997; Milner et al., 1999; Milner et al., 2005). Extranuclear PR-ir has been identified in bundles of presumed mossy fiber axons and in axon terminals in the stratum lucidum of the hippocampal CA3 region suggesting that PRs are in the DYN-containing mossy fiber pathway (Waters et al., 2008). This overlapping distribution suggests the possibility that ERs and PRs are positioned to directly influence the processing and/or release of DYN peptides. However, no study has yet examined the subcellular relationship of DYN with ERs and PRs within the mossy fiber pathway.

To test the hypothesis that DYN peptide activity can be modulated by ovarian steroids in the HF, the present study uses light and electron microscopic techniques to determine: 1) whether changes in ovarian steroids affect DYN peptide levels in the mossy fiber pathway in the dorsal DG and CA3, and 2) the subcellular relationship of DYN-containing mossy fibers with ERs (both α and β subtypes) and PRs. This study focuses on the dorsal hippocampus because estrogen-induced morphological changes have been most consistently reported in this region (Cooke and Woolley, 2005) and the dorsal hippocampus is closely associated with the development and persistence of addictive behaviors (Degoulet et al., 2007). Some of the data presented here have been previously published in an abstract (Torres-Reveron et al., 2006).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals and estrous cycle determination

Adult female Sprague Dawley rats (225–250 g at time of arrival; 2 – 3 months old; N = 15 from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) or Harlan-Sprague Dawley, Inc. (Indianapolis, IN;) were used. Rats were housed in pairs with ad libitum access to food and water and with 12:12 light/dark cycles (lights on 0600 – 1800). All procedures were approved by the Weill Cornell Medical College, Rockefeller University or Hunter College Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines. Rats were allowed to acclimate for one week after arrival prior to initiating vaginal smear cytology to determine estrous cycle stage (Turner and Bagnara, 1971). Only rats with regular, 4-day estrous cycles for 2 weeks were included in the study. Animals in either proestrus, estrus or diestrus 2 phases of the estrous cycle were analyzed. Diestrus 2 rather than diestrus 1 (i.e., metestrus) was chosen to be certain that animals were completely out of the estrus phase. For simplicity purposes, we will only use the term “diestrus”, referring specifically to diestrus 2 for the rest of the paper. Vaginal smear cytology was the main method used to determine estrous cycle phase. We further verified estrous cycle phase by determining uterine weight and measuring levels of estrogen and progestin from blood samples collected during the perfusion procedure. Plasma serum levels for progesterone and estradiol were determined by radioimmunoassay using Coat-A-Count kits from Diagnostics Products Corporation (Los Angeles, CA) available for estradiol and progesterone. Ovarian steroids values and uterine weight for each group have been previously published (Torres-Reveron et al., 2008).

Ovariectomy surgery and steroid replacement

Two groups of ovariectomized (OVX) rats with were used in this study. Rats received ovariectomy at either Weill Cornell Medical College or Hunter College following modified surgical guidelines previously published for ovariectomy surgery (Eddy, 1986). For the OVX procedure, rats were anesthetized with isoflurane (2–3% in oxygen) during which body temperature was monitored. The lumbar dorsum was shaved, cleaned and opened on each side. Each ovary and fat around the ovary was exposed, severed and removed. The muscle wall was closed with absorbable sutures. The skin was closed using stainless steel wound clips.

The first group of OVX rats were ovariectomized two weeks prior to administration of either estradiol or vehicle and were perfused after different time intervals of hormone exposure as the effects of estrogens are highly time-sensitive (Tanapat et al., 2005; Smith and McMahon, 2005). The 6 hrs and 24 hrs groups received a single injection of 10μg/0.2 mL of estradiol benzoate (E; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in sesame oil 6 or 24 hrs prior to perfusion. The 72 hrs group received 2 injections of E 24 hrs apart and was perfused 2 days after the last injection; this procedure has been previously shown to induce dendritic spine changes in CA1 (Woolley, 1998). The control or oil (O) group received an injection of sesame oil 24 hrs before perfusion. Blood estrogen levels for animals have been previously published (Torres-Reveron et al., 2008). The second group of OVX rats received ovariectomies on the same day they were implanted with Silastic capsules containing cholesterol or medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA, Sigma-Aldrich Corp (St. Louis, MO) that would remain for two weeks before brain removal. Capsules measurements were 0.058 in. internal diameter and a 0.077 in. outer diameter and contained 1 cm of the packed steroids (Dow Corning Silastic Brand Medical-Grade tubing, Dow Corning Corporation, Medical Products, Midland, MI).

Antisera

A rabbit polyclonal anti-DYN antibody used for the light microscopy study was a generous gift from Stanley Watson from the Mental Health Research Institute, Univ. of Michigan and has been previously characterized for specificity using both self-blocking and cross-blocking adsorption controls (Neal, Jr. and Newman, 1989). The antibody recognizes DYN-B 1–13 and has been previously used by our laboratory in immunohistochemical studies (Pierce et al., 1999). For the dual labeling electron microscopy experiments, we used a guinea pig polyclonal antibody against DYN purchased from Peninsula laboratories (Belmont, CA) and previously characterized and used in our laboratory (Svingos et al., 1999). The antibody used for the detection of ERα was a generous gift from S. Hayashi (Yokohama City University, Yokohama, Japan). This antibody is a rabbit polyclonal against the native rat ERα and recognizes amino acids 61 through the carboxyl terminus. The specificity of this antibody has been previously demonstrated (Okamura et al., 1992; Alves et al., 1998; Milner et al., 2001). The antibody used for the detection of ERβ was a rabbit polyclonal from Merck Research Laboratories (Rahway, NJ) against a conserved sequence of amino acids 64–82 in the N-terminus which is not present in the ERα receptor (Mitra et al., 2003). This antibody has been previously characterized by Western blot and preadsorption (Mitra et al., 2003) and immunolabeling with no primary antibody of forebrain sections (Milner et al., 2005). A rabbit polyclonal antibody against the DNA binding domain of the human PR was purchased from DAKO (A0098, Carpinteria, CA). It recognizes amino acids 533–547 of the N-terminus present in both the A and B isoforms of PR; the specificity of this antibody has been previously characterized (Traish and Wotiz, 1990; Kurita et al., 1998; Tibbetts et al., 1999; Molenda et al., 2002) and has been shown to recognize rat PR and other species by immunocytochemistry (Quadros et al., 2002).

Section preparation

Rats were deeply anesthetized with pentobarbital (150 mg/kg) on the morning of proestrus or diestrus (normal cycling groups) or following gonadal steroid treatment (OVX groups) and their brains fixed by aortic arch perfusion with: 1) 10 – 15 ml saline (0.9%) containing 1000 units of heparin; 2) 50 ml of 3.75% acrolein (Polysciences, Washington, PA) mixed in 2% paraformaldehyde in 0.1M phosphate buffer (PB; pH 7.6); and 3) 200 ml of 2% paraformaldehyde in PB (Milner and Veznedaroglu, 1992). During the perfusion, aortic blood was collected for estrogen and progesterone radioimmunoassay. After perfusion, the brains were removed from the skull, cut into 5 mm coronal blocks using a brain mold (Activational Systems, Inc., Warren, MI), and post-fixed for 30 minutes in the latter fixative. The block containing the hippocampal formation was sectioned (40 μm thick) on a Vibratome (VT1000S, Leica, Wein, Austria) and collected into PB. Sections then were stored in cryoprotectant (30% sucrose and 30% ethylene glycol in PB) until immunocytochemical processing. To insure identical labeling conditions during immunocytochemistry (Pierce at al., 1999), sections of each treatment group were rinsed in PB, coded with hole-punches in the cortex and pooled into single containers. Sections then were treated with 1% sodium borohydride in PB for 30 minutes to neutralize free aldehydes.

Light microscopy immunocytochemistry

For quantitative light microscopic localization of DYN, serial dilutions of the antibody were established and a linear function of antibody concentration against labeling intensity was obtained. A dilution of 1:30000 was chosen since this concentration produces slightly less than half-maximal labeling of DYN. This labeling intensity allows for variations in DYN in either direction that might be produced by the different treatment groups examined (Chang et al., 2000). The tissue was processed according to the avidin-biotin complex (ABC) method (Hsu et al., 1981). For this, tissue sections were rinsed in PB followed by Tris-buffered saline (TS; pH 7.6) and incubated; 1) in 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in TS, 30 min; 2) in 1:30000 dilution DYN antisera in 0.25% Triton X100 and 0.1% BSA/TS for 18–24 hours at room temperature and 24 hours at 4°C; 3) 1:400 dilution of biotinylated horse anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (IgG) (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA), 30 min; 4) ABC (at twice the recommended dilution to reduce background staining; Vector), 30 min; and 5) 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and H2O2 in TS for 6 minutes. All incubations were separated by washes in TS. Sections were mounted on gelatin coated slides, dehydrated in ascending concentrations of alcohols, and cover-slipped with D.P.X. neutral mounting medium (Sigma, St. Louis, MO).

For quantitative densitometry, images of regions of interest (R.O.I.) were captured using a Dage MTI CCD-72 camera and NIH Image 1.50 software on a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope. The mean gray value (of 256 gray levels) for each selected R.O.I. was determined. R.O.I. in the dentate gyrus and CA3 region of the hippocampus were outlined as previously published (Pierce et al., 1999). For this, pixel density linearly correlated with the density of dense core vesicles (average r= 0.92; Pierce et al., 1999), which is where most neuropeptides are stored (Thureson-Klein and Klein, 1990). To compensate for background staining and control for variations in illumination level between images, the average pixel density for 3 regions within the middle molecular layer, that has been shown to lack neuropeptide labeling (Gall et al., 1981) was subtracted. Tissue from control and experimental animals were processed together in the same crucibles. For each animal, a single best morphologically preserved hippocampal section was included in the analysis. Net optical density values obtained after subtracting background values were converted to a percentage scale of 256 preset gray values ranging from 0 to 100% using Image J. For statistical analyses, percentages were transformed by calculating the inverse sine of the proportion (Eisenhart and Hastay, 1947). Both normal cycling and ovariectomized animals were analyzed using a One Way ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc analyses using SPSS v. 11.0 for Windows.

Electron microscopy immunocytochemistry

For electron microscopic localization of DYN and ERs or PR, sections from proestrus rats were dually labeled for either ERα, ERβ or PR using immunoperoxidase and DYN using immunogold by methods described previously (Towart et al., 2002). Sections were incubated first in either ERα (1:3000 dilution), ERβ (1:2500 dilution) or PR (1:1000 dilution) in 0.1% BSA/TS for 4 days at 4°C, followed by incubation in DYN antibody (1:1500) for 24 hrs at 4°C in 0.1% BSA/TS with 0.025% Triton. ER- and PR-labeling was visualized using biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Vector) and the ABC immunoperoxidase technique described above. Following the DAB reaction step, sections were processed for DYN labeling using the silver-enhanced immunogold technique (Chan et al., 1990). For this, sections were rinsed in TS and incubated in a 1:50 dilution of goat anti-guinea pig IgG conjugated to 1-nm gold particles (Electron Microscopy Sciences, EMS, Washington, PA) in 0.001% gelatin and 0.08% BSA in PBS overnight at 4°C. Sections were rinsed in PBS, postfixed in 1.25% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 10 min, and rinsed again in PBS followed by 1.2% sodium citrate buffer, pH 7.4. The conjugated gold particles were enhanced by incubation in silver solution (IntenSE; Amersham, Piscataway, NJ) for 5–7 min. Sections were fixed 1 hr in 2% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated in ascending solutions of ethanol and propylene oxide, and embedded in EMBed 812 (EMS) between two sheets of aclar plastic (Honeywell, Pottsville, PA). Ultrathin sections (70–72 nm thick) through the midseptotemporal dentate gyrus (Swanson level 32 or 33) were cut on a Leica UCT ultratome. Sections were counterstained with Reynold’s lead citrate and uranyl acetate and examined with a FEI Tecnai Biotwin electron microscope equipped with an Advanced Microscopy Techniques digital camera (software version 3.2; Danvers, MA).

The subcellular relations of DYN profiles with ERs and PR in the mossy fiber pathway were analyzed in a total of 8 rats. At least 3 blocks were analyzed from 6 animals with the best labeling of both markers and morphological preservation. Labeled profiles were classified according to the nomenclature of Peters et al. (1991). Dendrite profiles were commonly postsynaptic to axon terminals and usually contained microtubular arrays. Unmyelinated axons had a small diameter (less than 0.2 μm) with a few small synaptic vesicles and synaptic junctions usually not present in the section. Terminal profiles contained numerous small synaptic vesicles, frequently had contacts with other neuronal profiles and had minimal diameters greater than 0.2 μm. Astrocytic profiles had no microtubules, contained glial filaments and usually conformed to the boundaries of surrounding profiles.

Both light and electron microscopic figures were prepared by adjusting levels, brightness and contrast in Adobe Photoshop 7.0.1 on a Dell computer. Final figures were assembled in Microsoft Power Point. Graphs were prepared with Graph Pad Prism 4.01 (Graph Pad Software, Inc., San Diego CA). Data was analyzed using SPSS 11.0 for Windows. Significance was considered at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Higher levels of DYN were detected in most regions of the mossy fiber pathway at estrus

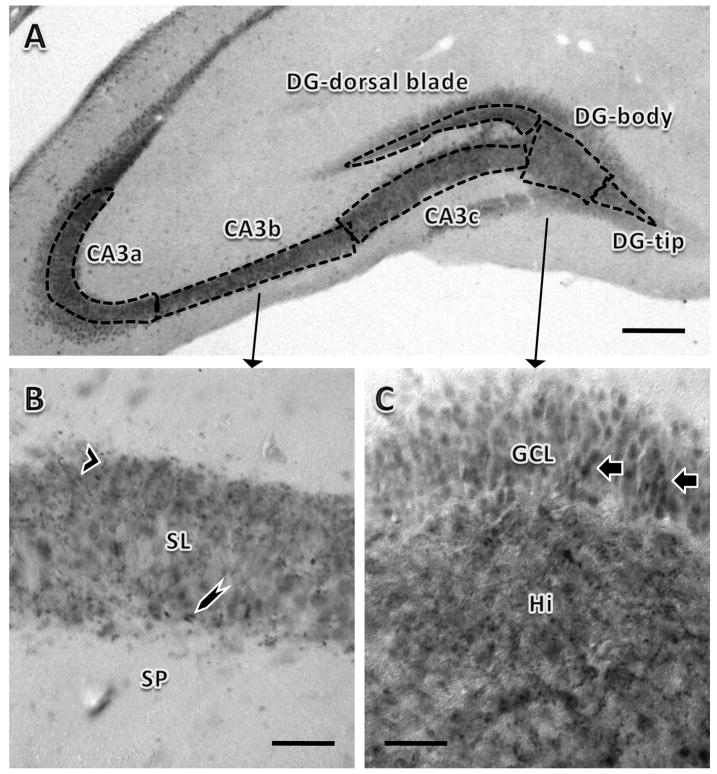

In agreement with previous studies (McLean et al., 1987; Nitsch and Riesenberg, 1990), DYN-ir was abundant in the mossy fiber pathway which spans the hilus of the DG and the stratum lucidum of the CA3 region (Fig. 1A). In both the hilus and stratum lucidum, DYN-ir was diffuse as well as in punctate varicosities (Fig. 1 B,C), consistent with reports that DYN is in both large mossy terminals and smaller collateral terminals (Pierce et al., 1999). Some DYN-labeling also was detected in the granule cell layer (Fig. 1C), consistent with reports that the majority of hippocampal DYN is made by dentate granule cells (Hoffman and Zamir, 1985; Chavkin et al., 1985; Drake et al., 2007). To determine whether changes were restricted to particular portions of the mossy fiber pathway, analysis was divided into 6 zones: 3 zones in the hilus of the DG and 3 zones in the CA3 stratum lucidum (see Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Distribution of DYN immunoreactivity in the rat hippocampal mossy fiber pathway. A: DYN-ir was found in the hilus of the dentate gyrus (DG) and stratum lucidum of the CA3 region. Three different zones of the dorsal DG (corresponding to levels between 3.80 and 4.30 caudal to Bregma, level 32) (Swanson, 1992) were analyzed: (1) the tip, (2) body or central region and (3) dorsal blade. The CA3 region also was divided into 3 zones: (1) CA3a, (2) CA3b and (3) CA3c based on the classical divisions of Lorente de Nó (Lorente de No, 1934). B: Both large (ling arrowhead) and small processes (short arrowhead) with DYN labeling are visible in stratum lucidum (SL) of CA3b. SP: Stratum pyramidale. C: In the body of the hilus (Hi), two types of DYN-immunoreactive processes were noticeable: some with punctate appearance and others larger and less dense. Many immunoreactive granule cells soma also were visible (arrows). GCL: Granule cell layer. Bar in A, 625 μm; bar in B and C, 125 μm. Pictures taken from a proestrus rat.

The pattern of DYN-ir in the mossy fiber pathway was compared between female rats in proestrus, diestrus and estrus (Figure 2, A–C). Quantitative results are shown in Table 1. A significant main effect of estrous cycle phase was found in all three subregions of the DG hilus (Tip: F(2, 14)= 16.42, p< 0.01; Body: F(2, 14)= 12.02, p< 0.01; Dorsal blade: F(2, 14)= 9.1, p< 0.01). Post-hoc analysis revealed that rats in the estrus phase of the cycle showed significantly higher DYN-ir in the tip, body and dorsal blade of the DG compared to rats in diestrus or proestrus (p< 0.05 for all comparisons). In addition, DYN-ir in the DG tip was significantly higher in proestrus rats than in diestrus rats (p< 0.05), and was significantly lower than in estrus rats (p< 0.05). When all three DG hilus subregions were averaged together (see Table 1), we found a significant main effect of estrous cycle (F(2, 14)= 13.47, p< 0.01) and post-hoc analysis revealed that DYN-ir in the estrus group was higher than in the proestrus (p< 0.05) or diestrus (p< 0.01) groups. Similar results were obtained in the CA3 stratum lucidum. A significant main effect of estrous cycle phase was observed for CA3b and CA3c (CA3b: F(2, 14)= 25.00, p< 0.01; CA3c: F(2, 14)= 9.69, p< 0.01) but not for CA3A (F(2, 14)= 1.93, p> 0.05). Post-hoc analysis revealed that in CA3b and CA3c, estrus rats had higher DYN-ir than rats in diestrus or proestrus (CA3b: p< 0.01 for both comparisons; CA3c: p< 0.05 for both comparisons). When all three subregions of CA3 were averaged together, there was a significant main effect of estrous cycle (F(2, 14)= 5.83, p< 0.05) revealing higher DYN-ir in the estrus group than in the proestrus or diestrus groups (p< 0.05 for both comparisons).

Figure 2.

Light microscopy images of DYN immunoreactivity from the dorsal DG hilus and part of CA3c. Images show representative immunoreactivity from rats in diestrus (A), proestrus (B) and estrus (C). Note that DYN-ir was only slightly darker in proestrus rats compared to diestrus but was much more intense in estrus rats compared to diestrus. Similar pattern was also observed in the rest of CA3. Bar in A, B and C, 1 mm.

Table 1.

Dynorphin levels in normal cycling rats shown as percent optical density above background

| Hilus | Diestrus | Proestrus | Estrus |

|---|---|---|---|

| DG-tip | 13.79 ± 0.59 | 16.73 ± 0.91* | 20.10 ± 0.84* |

| DG-body | 14.39 ± 0.86 | 16.59 ± 1.21 | 21.55 ± 1.06* |

| DG-dorsal bl. | 14.51 ± 0.90 | 16.34 ± 0.96 | 20.24 ± 1.01* |

| DG-whole | 14.23 ± 0.79 | 16.55 ± 1.02 | 20.63 ± 0.97* |

| Stratum lucidum | |||

| CA3a | 13.66 ± 0.53 | 15.57 ± 0.38 | 20.40 ± 1.12 |

| CA3b | 12.43 ± 0.62 | 13.25 ± 0.78 | 19.41 ± 0.83* |

| CA3c | 12.87 ± 0.54 | 14.15 ± 0.81 | 17.44 ± 0.87* |

| CA3-whole | 12.98 ± 0.56 | 14.32 ± 0.66 | 19.09 ± 0.94* |

represents significantly higher compared to diestrus group

Dynorphin levels in all subregions of the mossy fiber pathway were influenced by estradiol

Results from normal cycling rats suggest that DYN levels in the mossy fiber pathway may vary with hormonal level. Thus, the next set of experiments evaluated the effects of estradiol exposure period (6, 24 or 72 hrs) on DYN levels in the MF pathway. As shown in Table 2, ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of estradiol exposure for all three sub-regions of the DG (Tip: F(3, 16)= 14.44, p< 0.01; Body: F(3, 16)= 8.67, p< 0.01; Dorsal blade: F(3, 16)= 6.14, p< 0.01). Post-hoc analysis showed that in all three subregions of the DG, DYN-ir in the 24 hrs group was significantly higher than in the control or 6 hrs groups (p< 0.05 for all comparisons). The 72 hrs group had significantly higher DYN-ir than the control group in the tip of the DG (p< 0.05) and significantly higher DYN-ir than the 6 hrs group in both the tip and body of the DG (p< 0.05 for both comparisons). No significant differences in DYN-ir were observed between groups in the DG dorsal blade. When all three DG hilus subregions were averaged together, a significant main effect of estrous cycle was found (F(3, 16)= 9.04, p< 0.01). Post-hoc analysis confirmed that DYN-ir in the 24 hrs group was higher than the control and 6 hrs groups (p≤ 0.01 for both comparisons) while DYN-ir in the 72 hrs group only differed from that of the 6 hrs group (p< 0.05).

Table 2.

Dynorphin levels in ovariectomized rats exposed to estradiol for either 0, 6, 24 or 72 hrs shown as percent optical density above background

| Hilus | OVX + O | OVX+E 6hr | OVX+E 24hr | OVX+E 72hr |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DG-tip | 8.29 ± 0.25 | 7.91 ± 0.37 | 10.42 ± 0.41* | 10.07 ± 0.27* |

| DG-body | 8.45 ± 0.33 | 7.98 ± 0.37 | 10.71 ± 0.59* | 10.08 0.46^ |

| DG-dorsal bl. | 8.68 ± 0.33 | 8.07 ± 0.54 | 11.09 ± 0.83* | 9.80 ± 0.36 |

| DG-whole | 8.47 ± 0.30 | 7.99 ± 0.43 | 10.74 ± 0.61* | 9.98 ± 0.36^ |

| Stratum lucidum | ||||

| CA3a | 8.64 ± 0.27 | 8.32 ± 0.23 | 11.52 ± 1.34* | 9.60 ± 0.42 |

| CA3b | 8.68 ± 0.15 | 8.35 ± 0.29 | 10.89 ± 0.89* | 9.31 ± 0.26 |

| CA3c | 8.73 ± 0.17 | 8.46 ± 0.36 | 10.78 ± 0.72* | 9.68 ± 0.34 |

| CA3-whole | 8.64 ± 0.20 | 8.38 ± 0.30 | 11.06 ± 0.99* | 9.53 ± 0.34 |

represents significantly higher than OVX+O and OVX+E 6hr groups.

represents significantly higher than OVX+E 6hr group.

In the stratum lucidum of the CA3, we also found a significant main effect of estrogen exposure in all three subregions (CA3a: F(3, 16)= 4.39, p< 0.05; CA3b: F(3, 16)= 5.94, p< 0.01; CA3c: F(3, 16)= 6.31, p< 0.01). Post-hoc analysis revealed that the 24 hrs group had significantly higher DYN-ir than the control or 6 hrs groups (p< 0.05 for both comparisons). In contrast to results noted in the DG, DYN-ir in the 72 hrs group was not significantly different from any of the other groups in the CA3 region. When all three subregions of the CA3 were averaged together, we found a significant main effect of estrogen treatment (F(3, 16)= 5.8, p= 0.01) and post-hoc analysis revealed that DYN-ir in the 24 hrs group was significantly higher than in the control or 6 hrs groups (p< 0.05 for both comparisons) but no different from the 72 hrs group (p>0.05). In summary, 24 hrs of estrogen treatment produced an increase in DYN-ir in both the DG and CA3 regions of the dorsal hippocampus while 72 hrs of treatment produced a slight elevation only different from the control group at the tip of the DG.

Some reports have suggested that ovariectomy alone can either decrease (Foradori et al., 2002) or increase (Fullerton et al., 1988; Spampinato et al., 1995) the levels of prodynorphin mRNA or DYN peptide in the hypothalamus and pituitary. Hence, for comparison purposes, a subset of tissue from the aforementioned diestrus rats was processed with tissue from the control OVX animals in the same experiment. Average immunoreactivity between diestrus rats and ovariectomized rats was 95.3% similar in the DG hilus and 94.1% similar in the CA3 stratum lucidum (not shown). Statistical analysis confirmed that, indeed, DYN levels in diestrus rats and ovariectomized rats were similar (p> 0.05 for all comparisons on a Student t-test). Thus, the 2-week ovariectomy period used in our models did not decrease DYN levels in the mossy fiber pathway below diestrus levels.

Chronic medroxyprogesterone increases DYN-ir

Since fluctuations in both estrogens and progestins occur over the estrous cycle, the next set of studies evaluated the effects of progestins. Comparable to the effects of estradiol administration for 24 hrs, chronic administration of MPA significantly increased DYN-ir in all regions of the hilus and CA3 analyzed (Table 3). Specifically, statistical analyses revealed that DYN-ir in animals receiving MPA was significantly higher than in control animals in the tip (t(4)= 12.5, p< 0.001), body (t(4)= 4.64, p< 0.01) and dorsal blade (t(4)= 3.76, p< 0.05) of the DG. As a whole, DYN-ir in the DG hilus was significantly higher in MPA administered rats as compared to control rats (t(4)= 6.42, p< 0.01). Similarly, rats receiving MPA showed increased DYN-ir in the CA3b (t(4)= 5.32, p< 0.01) and CA3c (t(4)= 4.70, p< 0.01). No difference was observed in the CA3a sub-region (t(4)= 1.01, p> 0.05). When all CA3 regions were pooled together, MPA administered animals showed significantly higher DYN-ir compared to control animals (t(4)= 4.04, p< 0.05). In summary, chronic administration of MPA alone produced a significant increase in DYN-ir throughout the mossy fiber pathway.

Table 3.

Dynorphin levels in ovariectomized rats exposed to chronic medroxyprogesterone shown as percent optical density above background

| Hilus | OVX + O | OVX+MPA |

|---|---|---|

| DG-tip | 13.25 ± 0.14 | 18.61 ± 0.42* |

| DG-body | 14.44 ± 0.76 | 18.75 ± 0.47* |

| DG-dorsal bl. | 13.50 ± 1.07 | 17.83 ± 0.29* |

| DG-whole | 13.73 ± 0.66 | 18.40 ± 0.40* |

| Stratum lucidum | ||

| CA3a | 15.36 ± 1.25 | 16.81 ± 0.70 |

| CA3b | 13.20 ± 0.47 | 17.37 ± 0.65* |

| CA3c | 12.45 ± 0.80 | 16.65 ± 0.31* |

| CA3-whole | 13.67 ± 0.84 | 16.95 ± 0.55* |

represents significantly higher than OVX+O group.

By electron microscopy, DYN-containing profiles have direct and indirect relationships with ERs and PRs

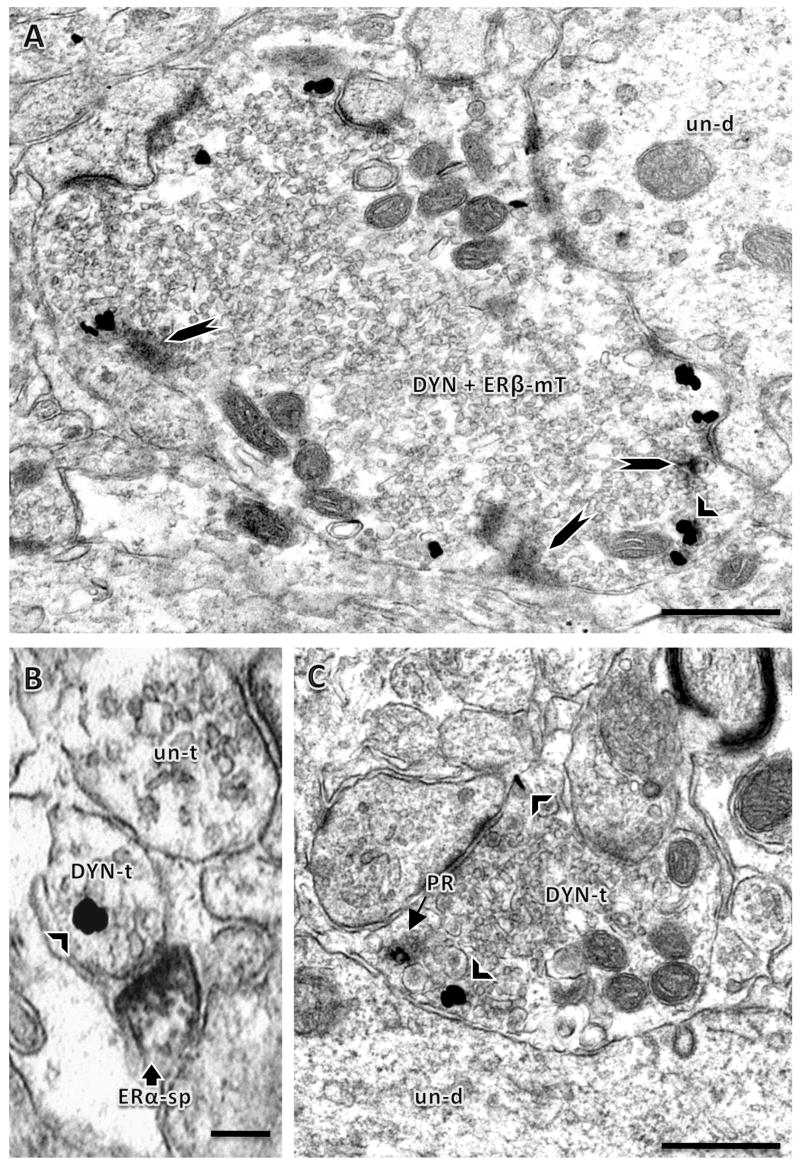

The light microscopic experiments suggested that estrogen and progestins affect DYN levels in the mossy fiber pathway. Thus, we next sought to evaluate the subcellular localization of ERs or PRs relative to DYN-containing profiles by electron microscopy (EM). Consistent with prior studies (Nitsch and Riesenberg, 1990; Pierce et al., 1999), most of the DYN-ir (identified using immunogold) was found in large mossy fiber terminals that ranged from 1.0 to 2.0 μm in size (Fig. 3A). DYN-ir also was found in smaller terminals ranging from 0.4 to1.0 μm (Fig. 3B and C). Frequently, the immunogold labeling for DYN within the terminals was found in clusters of 2 to 3 gold particles, many of which were seen associated with dense core vesicles (Fig. 3), the storage sites for these neuropeptides. Similar to our previous reports (Milner et al., 2001; Milner et al., 2005), extranuclear ERα-ir and ERβ-ir was found in dendrites, spines, axons and axon terminals. ERα-ir also was observed in glia and smaller terminals (Milner et al., 2001; Towart et al., 2003).

Figure 3.

Electron microscopic localization of DYN relative to ERs or PR in the mossy fiber pathway. A: A large mossy fiber terminal is dual labeled for DYN and ERβ (DYN+ ERβ-mT). Patches of ERβ-ir (long arrowheads) identified by peroxidase affiliated with a cluster of small synaptic vesicles (lower right). DYN-ir which is identified by immunogold-silver particles, was often clustered particularly near dense core vesicles (example, short arrowhead). B: A small terminal (DYN-t) with a cluster of DYN-immunogold-silver (black particles) contacts an ERα-immunoperoxidase labeled spine (sp). Other unlabeled terminals (un-t) were also in the field. C: A terminal with immunogold-silver for DYN (arrowhead) also contains PR-ir (arrow). A and B: central hilus; C: stratum lucidum of CA3. Bars A and C, 500 nm, B, 100 nm.

Colocalization was observed for ERβ and DYN, but not ERα and DYN. ERβ-ir was present in large (about 1.0 μm in diameter) DYN-labeled terminals with the morphological characteristics of mossy fibers (Commons and Milner, 1995; Milner et al., 2005) and located mostly in the central hilus of the DG and in stratum lucidum of CA3. Within these large DYN-labeled terminals, ERβ-ir was associated with clusters of small synaptic vesicles and was close to the plasma membrane (Fig. 3A). Some ERβ-labeled profiles lacked DYN immunoreactivity although immunoreagents were accessible as demonstrated by the presence of DYN-labeled profiles nearby (average distance of 0.55 ± 0.09 μm apart, not shown). Although ERα was not present in DYN-ir terminals in either the dentate gyrus or CA3, small (about 600 nm in diameter) DYN-labeled terminals synapsed with ERα-labeled dendritic spines in some cases (Fig. 3B). When ERα-immunoreactive profiles were located in the same field as DYN-labeled profiles, the average distance between profiles was 0.746 ± 0.12 μm (not shown).

Since our previous study showed that PR labeling in the DG is scarce (Waters et al., 2008), the present study examined the subcellular relationships of DYN-labeling with PR-labeled profiles in the CA3 field only. PR-ir was mostly observed in bundles of axons in stratum lucidum, consistent with localization to mossy fiber axons (Tabori et al., 2004; Waters et al., 2008). Rarely, PR-ir was found in pre-terminal axons that were continuous with DYN-labeled terminals (not shown). In some instances, PR-labeled terminals contained DYN-ir (Fig. 3C).

DISCUSSION

The current study shows fluctuations in mossy fiber pathway DYN immunoreactivity across the estrous cycle and with hormonal manipulation. Specifically, DYN-ir in the MF pathway was: 1) higher during estrus in normal cycling female rats, 2) elevated at 24 or 72 hrs but not 6 hrs after estradiol administration in OVX rats; and 3) elevated following chronic medroxyprogesterone administration in OVX rats. Ultrastructurally, DYN-ir colocalized with extranuclear ERβ and PR in mossy fiber terminals and axons, while ERα-ir was found in a separate population of processes.

Methodological considerations

OVX models with different hormonal replacement therapy regimens have been widely used, [for example: (McEwen, 2001; Cyr et al., 2001)]. Ideally hormone replacement models would closely mimic natural hormonal fluctuations while allowing identification of the role of each replaced hormone. However, complete replication of natural hormone fluctuations is hampered by many factors, including ovariectomy itself, which can alter the ratio of receptors and other hormonal profiles, as well as variability in dose, time of drug administration, administration route or dosing interval after OVX (Tanapat et al., 2005). In the present study, we first used normal cycling animals to examine whether any effect on DYN-ir was observed in the intact animal model. The three different hormone replacement paradigms used subsequently mimic some aspects of normal gonadal hormone fluctuation and, thereby, allow some comparison with previous studies. Given that some reports have shown alterations of prodynorphin mRNA and DYN itself after ovariectomy in other brain areas (Fullerton et al., 1988; Spampinato et al., 1995; Foradori et al., 2002), we performed a direct comparison between normal cycling animals in diestrus and control OVX animals. There were no differences between these groups, which were processed for immunocytochemistry together, suggesting that the modulatory effects of gonadal hormones on DYN in other brain areas are most likely different from those in the HF as basal levels of DYN 2 weeks post-ovariectomy were no different than levels in normal cycling diestrus animals.

The dual labeling electron microscopy studies were qualitative rather than quantitative for two reasons. First, the subcellular location of ERs, PRs and DYN is discrete and affiliated with different organelles in axons and axon terminals: ER- and PR-ir is found in small patches associated with the plasma membrane or small synaptic vesicles whereas DYN-ir is mostly associated with dense core vesicles. These distinct distributions of labeling create a low likelihood of finding both immunoreactivities (receptor and peptide) in a single section through a given terminal or axon. Second, optimal detection of ER (or PR) immunoreactivity and DYN immunoreactivity required different labeling conditions (e.g., DYN localization required small amounts of detergent whereas hormone receptor localization was best without detergent). For these reasons, quantification of profiles containing immunoreactivities for the ERs (or PRs) and DYN would have led to substantial underestimation of actual colocalization and perhaps misleading conclusions about the characteristics of DYN-positive and ER (PR)-containing terminals. The semi-quantitative data presented here provide evidence for direct influences of gonadal hormone receptors on the DYN-containing mossy fiber pathway and provide a rationale for future mechanistic experiments.

It is also important to note that the ERβ antibody used in this study has been shown to recognize the most abundant splice variant in HF: ERβ1δ4. ERβ1δ4 has an altered ligand-binding domain and lacks exon 4, which is necessary for nuclear localization (Price, Jr. et al., 2000). Consistent with a previous report (Milner et al., 2005), most of the observed ERβ1δ4 localization was extranuclear. While ERβ1δ4 is the most abundant, other variants such as the classic ERβ1, which heterodimerizes with ERβ1δ4 and restores its ligand activation capacity (Leung et al., 2006), are present in the HF and may contribute to the observed effects of estrogen.

Distinct regional effects of ovarian hormones on DYN-ir

In the present study, we observed that the magnitude of increase in DYN varies by subregion in the mossy fiber pathway. For example, in normal cycling rats and in OVX rats that received MPA, no significant changes in DYN were observed in CA3a as compared to controls while other subregions showed significant experimental differences. Such regional variation could be due to anatomical or neurochemical distinctions between different portions of the hilus and CA3. First, the anatomical distribution of axon collaterals that arise from granule cells differs depending on cell body location: the hilus receives extensive ramifications from axons arising from granule cells in the infrapyramidal blade while axons arising from granule cells near the tip of the suprapyramidal blade are more confined to the CA3c (Claiborne et al., 1986). Second, the distribution of DYN-ir varies by subcellular compartment within the mossy fibers pathway. In example, DYN-ir directly correlates with the number of labeled dense core vesicles in neuronal profiles and slightly more labeled dense core vesicles were found in axonal profiles than in mossy fiber terminals per μm of tissue examined (Pierce et al., 1999). Third, the distribution of ER-immunoreactive cells has been shown to be higher in the hilus of the DG than in the CA3 region (Weiland et al., 1997), suggesting that ER-initiated increases in DYN may be enhanced in the hilus as compared to CA3. Finally, differential projection of afferents containing neurotransmitters like acetylcholine (Towart et al., 2003) or norepinephrine (Milner and Bacon, 1989) to select MF pathway lamina would suggest varied innervation patterns across the MF pathway.

Potential mechanisms by which ovarian hormones increase DYN

A period of approximately 24 hrs following estradiol administration is necessary to observe an increase in DYN levels in the hilus and CA3 mossy fibers of both normal cycling and ovariectomized animals. Our findings are consistent with reports that the effects of estrogen require time to activate gene transcription (Vasudevan and Pfaff, 2007) and subsequently induce DYN expression. Estrogen-induced elevation of DYN may result from stimulation of an intermediary protein or, alternatively, increased translation or peptide processing. Indeed, the presence of ERβ/PR in conjunction with DYN in axons and terminals may locally affect DYN processing and/or release, since prodynorphin processing within hippocampal axons and terminals has been shown previously (Yakovleva et al., 2006).

Based on several published findings we propose that a possible intermediary by which estrogen modifies DYN expression in the MF pathway is brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). Indeed, there is an anatomical overlap of BDNF and DYN-ir in the mossy fiber pathway (Conner et al., 1997) as well as a functional overlap with estrogen effects on BDNF (Scharfman and MacLusky, 2005). Similar to DYN fluctuations across the estrous cycle, BDNF appears to be regulated by estrogen: mossy fiber BDNF-ir is high during the proestrus phase of the estrous cycle (Scharfman et al., 2003) and estrogen replacement in young ovariectomized rats restores hippocampal BDNF expression (Sohrabji and Lewis, 2006). In the dorsal striatum, DYN has been shown to be a downstream effector of BDNF through activation of MAP kinase (Logrip et al., 2008). Estrogen effects on BDNF are likely to be mediated through an ER (Sohrabji et al., 1995; Solum and Handa, 2001) and we have found ERs in DYN-containing profiles, thus estrogen may modify the levels of DYN in the mossy fiber pathway by initiating an ER-mediated rise in BDNF, followed by MAP kinase activation, and consequently increased DYN, similar to the mechanism reported for the dorsal striatum (Logrip et al., 2008).

Consequences of DYN regulation by ovarian hormones in the mossy fiber pathway

Rats in proestrus experience facilitated long-term potentiation (LTP) (Warren et al., 1995). Electrophysiological experiments have confirmed the role of estrogen in LTP regulation as OVX rats receiving estradiol 24 to 48 hours before assessment show increases in LTP (Smith and McMahon, 2005). At least part of the estradiol facilitation of HF LTP has been attributed to estradiol-induced increases in excitability at CA3 pyramidal cell synapses with CA1 pyramidal cells (Woolley and Schwartzkroin, 1998). Recent studies have begun to address the effect of estrogens on CA3 pyramidal cell activity (Scharfman et al, 2007), however, the consequences of estrogen administration on mossy fiber pathway excitability has not yet been specifically examined.

It is well documented that DYN reduces excitatory activity in both the DG and CA3 of the HF (Wagner et al., 1993) and that seizure activity results in decreased DYN in the mossy fiber pathway (Gall et al., 1990; Pierce et al., 1999) followed by increased prodynorphin in granule cells (Przewlocki et al., 1995). It has been proposed that DYN released during seizures functions to reduce excitatory activity and the subsequent increase in DYN mRNA restores depleted terminal stores (Romualdi et al., 1999a). As estrogen can increase seizure susceptibility, a corresponding estrogen-induced increase in DYN in the mossy fiber pathway may help to maintain homeostatic balance and prevent abnormal excitability during normal estrogen surges across the estrous cycle. We propose that one of the main roles of DYN would be reactive: limiting excitability in response to high-intensity stimuli. Indeed, studies show that the dense core vesicles storing neuropeptides like DYN require specific forms of high-intensity stimulation for release in the HF (Wagner et al., 1990; Wagner et al., 1991; Wagner et al., 1993; Drake et al., 1994).

Progesterone is also known to affect hippocampal physiology and behavior. Progesterone acts as an anticonvulsant by enhancing GABA-A receptor activity, via its metabolite allopregnalone (Belelli and Lambert, 2005) or through PR activation (Edwards et al., 2000). Its administration has been shown to attenuate estrogen-induced increases in CA1 spine density (Woolley and McEwen, 1993) and reverses estrogen-enhancement of spatial memory (Sandstrom and Williams, 2001). However, OVX rats receiving MPA showed enhanced performance on tasks of object recognition and object placement, which measure non-spatial and spatial memory, respectively, as compared to controls (Luine, Jacome and Mohan, unpublished observations). In support of this, progesterone alone can increases the time spent exploring a novel object in an object recognition task (Walf et al., 2006). In contrast to the aforementioned estrogen-opposing actions of progesterone, our data suggest that estrogen and progesterone work cooperatively, instead of antagonistically, to produce an increase in DYN expression in the mossy fiber pathway. While synergistic effects of estradiol and progesterone in the brain are scarce, in the pituitary, treatment with either hormone produce an equal effect in decreasing lutenizing hormone mRNA in ovariectomized rats (Corbani et al., 1990).

Clinical implications

Estrogen enhances excitability, LTP and seizure susceptibility in experimental models and, clinically, is associated with catamenial epilepsy. Estrogen and progesterone enhancement of DYN levels may make available a larger pool of DYN to act as a “brake” against excitability. Such elevations in DYN would be particularly relevant during the estrous or menstrual cycle and, additionally, relevant during pregnancy. In pregnant rats and a pseudopregnancy model, in which non-pregnant rats are administered the high estrogen and progesterone levels seen in pregnancy, the normally modest DYN-kappa opioid receptor analgesic system in the spinal cord becomes greatly amplified, providing an increased pain threshold in the days surrounding parturition (Medina et al., 1995; Dawson-Basoa and Gintzler, 1998). Although mossy fiber DYN has not been studied in the pregnant or pseudopregnant rat, it is possible that a similar DYN amplification occurs in the HF to promote a homeostatic function useful in late pregnancy/parturition.

In the brain, DYN levels respond to both acute and chronic exposure to drugs of abuse. The hippocampal DYN system appears to be more sensitive to opiates than to psychostimulants. A single morphine injection has been shown to decrease DYN in the HF (Nylander et al., 1995) while exogenous opioid agonists increase DYN (Kiraly et al., 2006). Morphine or synthetic opioid agonists decrease (Romualdi et al., 1991), increase, or produce no change (Kiraly et al., 2006) in prodynorphin mRNA. In contrast to morphine, psychostimulants such as methamphetamine or cocaine, which consistently produce increases in DYN in the hypothalamus and striatum (Kreek, 1996), produce no change in prodynorphin mRNA in the hippocampus (Romualdi et al., 1999b; Yuferov et al., 2001).

In animal models, estrogen can enhance drug seeking behavior and affect reward perception, withdrawal, and relapse (Carroll et al., 2004). Drug-seeking behavior is thought to involve hippocampal-dependent associative learning (Berke and Hyman, 2000). We show that estrogen also enhances DYN in the HF. Since DYN modulates hippocampal-dependent learning (Sandin et al., 1998) and estrogen modulates the hippocampal DYN system, the present study provides critical new evidence of ovarian steroid modulation of hippocampal DYN, which may ultimately affect drug-related associative learning.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the following grants: DA08259 (T.A.M. & C.T.D.), NS07080 (B.S.M.) and minority supplement to DA08259 (A.T.R.). We thank Ms. Nora Tabori, Mr. Scott Herrick and Dr. Russell Romeo (Barnard College) for technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- DYN

dynorphin

- DG

dentate gyrus

- EM

electron microscopy

- ER

estrogen receptor

- HF

hippocampal formation

- ir

immunoreactivity

- KOR

kappa opioid receptor

- LENK

leucine-enkephalin (Leu-enkephalin)

- LTP

long-term potentiation

- MF

mossy fiber

- MPA

medroxyprogesterone

- OVX

ovariectomized

- PR

progesterone receptor

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alves SE, Weiland NG, Hayashi S, McEwen BS. Immunocytochemical localization of nuclear estrogen receptors and progestin receptors within the rat dorsal raphe nucleus. J Comp Neurol. 1998;391:322–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belelli D, Lambert JJ. Neurosteroids: endogenous regulators of the GABA(A) receptor. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:565–575. doi: 10.1038/nrn1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berke JD, Hyman SE. Addiction, dopamine, and the molecular mechanisms of memory. Neuron. 2000;25:515–532. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81056-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke MC, Letts PA, Krajewski SJ, Rance NE. Coexpression of dynorphin and neurokinin B immunoreactivity in the rat hypothalamus: Morphologic evidence of interrelated function within the arcuate nucleus. J Comp Neurol. 2006;498:712–726. doi: 10.1002/cne.21086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll ME, Lynch WJ, Roth ME, Morgan AD, Cosgrove KP. Sex and estrogen influence drug abuse. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:273–279. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caudle RM, Chavkin C, Dubner R. Kappa2 opioid receptors inhibit NMDA receptor-mediated synaptic currents in guinea pig CA3 pyramidal cells. J Neurosci. 1994;14:5580–5589. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-09-05580.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caudle RM, Wagner JJ, Chavkin C. Endogenous opioids released from perforant path modulate norepinephrine actions and inhibitory postsynaptic potentials in guinea pig CA3 pyramidal cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1991;258:18–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang PC, Aicher SA, Drake CT. Kappa opioid receptors in rat spinal cord vary across the estrous cycle. Brain Res. 2000;861:168–172. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02461-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavkin C, Shoemaker WJ, McGinty JF, Bayon A, Bloom FE. Characterization of the prodynorphin and proenkephalin neuropeptide systems in rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1985;5:808–816. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-03-00808.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claiborne BJ, Amaral DG, Cowan WM. The light and electron microscopic analysis of the mossy fibers of the rat dentate gyrus. J Comp Neurol. 1986;246:435–458. doi: 10.1002/cne.902460403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commons KG, Milner TA. Ultrastructural heterogeneity of enkephalin-containing neurons in the rat hippocampal formation. J Comp Neurol. 1995;358:324–342. doi: 10.1002/cne.903580303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner JM, Lauterborn JC, Yan Q, Gall CM, Varon S. Distribution of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) protein and mRNA in the normal adult rat CNS: Evidence for anterograde axonal transport. J Neurosci. 1997;17:2295–2313. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-07-02295.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke BM, Woolley CS. Gonadal hormone modulation of dendrites in the mammalian CNS. J Neurobiol. 2005;64:34–46. doi: 10.1002/neu.20143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbani M, Counis R, Wolinska-Witort E, ngelo-Bernard G, Moumni M, Jutisz M. Synergistic effects of progesterone and oestradiol on rat LH subunit mRNA. J Mol Endocrinol. 1990;4:119–125. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0040119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyr M, Ghribi O, Thibault C, Morissette M, Landry M, Di Paolo T. Ovarian steroids and selective estrogen receptor modulators activity on rat brain NMDA and AMPA receptors. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2001;37:153–161. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson-Basoa M, Gintzler AR. Gestational and ovarian sex steroid antinociception: synergy between spinal kappa and delta opioid systems. Brain Res. 1998;794:61–67. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00192-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lanerolle NC, Williamson A, Meredith C, Kim JH, Tabuteau H, Spencer DD, Brines ML. Dynorphin and the kappa 1 ligand [3H]U69,593 binding in the human epileptogenic hippocampus. Epilepsy Res. 1997;28:189–205. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(97)00044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degoulet M, Rouillon C, Rostain JC, David HN, Abraini JH. Modulation by the dorsal, but not the ventral, hippocampus of the expression of behavioural sensitization to amphetamine. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007:1–12. doi: 10.1017/S146114570700822X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake CT, Chavkin C, Milner TA. Opioid systems in the dentate gyrus. Prog Brain Res. 2007;163C:245–814. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)63015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake CT, Terman GW, Simmons ML, Milner TA, Kunkel DD, Schwartzkroin PA, Chavkin C. Dynorphin opioids present in dentate granule cells may function as retrograde inhibitory neurotransmitters. J Neurosci. 1994;14:3736–3750. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-06-03736.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy CA. Experimental Surgery of the Genitalia System. In: Gay WI, Heavner JE, editors. Methods of Animal Experimentation. Vol. 7. Orlando, FL: Academic Press; 1986. p. 191. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards HE, Epps T, Carlen PL, MacLusky NJ. Progestin receptors mediate progesterone suppression of epileptiform activity in tetanized hippocampal slices in vitro. Neurosci. 2000;101:895–906. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00439-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhart C, Hastay MW. Techniques of Statistical Analysis. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Foradori CD, Coolen LM, Fitzgerald ME, Skinner DC, Goodman RL, Lehman MN. Colocalization of progesterone receptors in parvicellular dynorphin neurons of the ovine preoptic area and hypothalamus. Endocrinology. 2002;143:4366–4374. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullerton MJ, Smith AI, Funder JW. Immunoreactive dynorphin is regulated by estrogen in the rat anterior pituitary. Neuroendocrin. 1988;47:1–6. doi: 10.1159/000124882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gall C. Seizures induce dramatic and distinctly different changes in enkephalin, dynorphin, and CCK immunoreactivities in mouse hippocampal mossy fibers. J Neurosci. 1988;8:1852–1862. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-06-01852.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gall C, Brecha N, Karten HJ, Chang K-J. Localization of enkephalin-like immunoreactivity to identified axonal and neuronal populations of the rat hippocampus. J Comp Neurol. 1981;198:335–350. doi: 10.1002/cne.901980211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gall C, Lauterborn J, Isackson P, White J. Seizures, neuropeptide regulation, and mRNA expression in the hippocampus. Prog Brain Res. 1990;83:371–390. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)61263-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman RL, Coolen LM, Anderson GM, Hardy SL, Valent M, Connors JM, Fitzgerald ME, Lehman MN. Evidence that dynorphin plays a major role in mediating progesterone negative feedback on gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons in sheep. Endocrinology. 2004;145:2959–2967. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman DW, Zamir N. Localization and quantitation of proenkephalin-derived neuropeptides in the rat hippocampus. Neuropeptides. 1985;5:437–440. doi: 10.1016/0143-4179(85)90048-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenab S, Niyomchai T, Chin J, Festa ED, Russo SJ, Perrotti LI, Quinones-Jenab V. Effects of cocaine on c-fos and preprodynorphin mRNA levels in intact and ovariectomized Fischer rats. Brain Res Bull. 2002;58:295–299. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(02)00793-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiraly KP, Riba P, D’Addario C, Di BM, Landuzzi D, Candeletti S, Romualdi P, Furst S. Alterations in prodynorphin gene expression and dynorphin levels in different brain regions after chronic administration of 14-methoxymetopon and oxycodone-6-oxime. Brain Res Bull. 2006;70:233–239. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreek MJ. Cocaine, dopamine and the endogenous opioid system. J Addict Dis. 1996;15:73–96. doi: 10.1300/J069v15n04_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurita T, Young P, Brody JR, Lydon JP, O’Malley BW, Cunha GR. Stromal progesterone receptors mediate the inhibitory effects of progesterone on estrogen-induced uterine epithelial cell deoxyribonucleic acid synthesis. Endocrinology. 1998;139:4708–4713. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.11.6317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Land BB, Bruchas MR, Lemos JC, Xu M, Melief EJ, Chavkin C. The dysphoric component of stress is encoded by activation of the dynorphin kappa-opioid system. J Neurosci. 2008;28:407–414. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4458-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung YK, Mak P, Hassan S, Ho SM. Estrogen receptor (ER)-beta isoforms: a key to understanding ER-beta signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:13162–13167. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605676103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin MC, Sawchenko PE. Neuropeptide co-expression in the magnocellular neurosecretory system of the female rat: Evidence for differential modulation by estrogen. Neurosci. 1993;54:1001–1018. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90591-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loacker S, Sayyah M, Wittmann W, Herzog H, Schwarzer C. Endogenous dynorphin in epileptogenesis and epilepsy: anticonvulsant net effect via kappa opioid receptors. Brain. 2007;130:1017–1028. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logrip ML, Janak PH, Ron D. Dynorphin is a downstream effector of striatal BDNF regulation of ethanol intake. FASEB J. 2008 doi: 10.1096/fj.07-099135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorente de No R. Studies on the structure of the cerebral cortex-II. Continuation of the study of the ammonic system. J Psychol Neurol. 1934;46:113–117. [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel KL, Mundy WR, Tilsom HA. Microinjection of dynorphin into the hippocampal formation impairs spatial learning in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1990;35:429–435. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(90)90180-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. Invited review: Estrogens effects on the brain: multiple sites and molecular mechanisms. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91:2785–2801. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.6.2785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinty JF, Henriksen SJ, Goldstein A, Terenius L, Bloom FE. Dynorphin is contained within hippocampal mossy fibers: immunochemical alterations after kainic acid administration and colchicine-induced neurotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:589–593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.2.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean S, Rothman RB, Jacobson AE, Rice KC, Herkenham M. Distribution of opiate receptor subtypes and enkephalin and dynorphin immunoreactivity in the hippocampus of squirrel, guinea pig, rat, and hamster. J Comp Neurol. 1987;255:497–510. doi: 10.1002/cne.902550403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina VM, Gupta D, Gintzler AR. Spinal cord dynorphin precursor intermediates decline during late gestation. J Neurochem. 1995;65:1374–1380. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65031374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner TA, Ayoola K, Drake CT, Herrick SP, Tabori NE, McEwen BS, Warrier S, Alves SE. Ultrastructural localization of estrogen receptor beta immunoreactivity in the rat hippocampal formation. J Comp Neurol. 2005;491:81–95. doi: 10.1002/cne.20724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner TA, McEwen BS, Hayashi S, Alves SE. Ultrastructural evidence that hippocampal alpha estrogen receptors are located at extranuclear sites. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1999:25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner TA, McEwen BS, Hayashi S, Li CJ, Reagan LP, Alves SE. Ultrastructural evidence that hippocampal alpha estrogen receptors are located at extranuclear sites. J Comp Neurol. 2001;429:355–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner TA, Veznedaroglu E. Ultrastructural localization of neuropeptide Y-like immunoreactivity in the rat hippocampal formation. Hippocampus. 1992;2:107–126. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450020204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra SW, Hoskin E, Yudkovitz J, Pear L, Wilkinson HA, Hayashi S, Pfaff DW, Ogawa S, Rohrer SP, Schaeffer JM, McEwen BS, Alves SE. Immunolocalization of estrogen receptor beta in the mouse brain: comparison with estrogen receptor alpha. Endocrinology. 2003;144:2055–2067. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-221069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molenda HA, Griffin AL, Auger AP, McCarthy MM, Tetel MJ. Nuclear receptor coactivators modulate hormone-dependent gene expression in brain and female reproductive behavior in rats. Endocrinology. 2002;143:436–444. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.2.8659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal CR, Jr, Newman SW. Prodynorphin peptide distribution in the forebrain of the Syrian hamster and rat: A comparative study with antisera against dynorphin A, dynorphin B, and the C-terminus of the prodynorphin precursor molecule. J Comp Neurol. 1989;288:353–386. doi: 10.1002/cne.902880302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsch C, Riesenberg R. Ultrastructure of the dynorphin-immunoreactivity in rat brain hippocampal mossy fiber system. Acta Histochem (Jena) 1990;89(Suppl 38):167–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nylander I, Vlaskovska M, Terenius L. The effects of morphine treatment and morphine withdrawal on the dynorphin and enkephalin systems in Sprague-Dawley rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1995;118:391–400. doi: 10.1007/BF02245939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura H, Yamamoto K, Hayashi S, Kuroiwa A, Muramatsu M. A polyclonal antibody to the rat oestrogen receptor expressed in Escherichia coli: Characterization and application to immunohistochemistry. J Endocrinol. 1992;135:333–341. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1350333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce JP, Kurucz O, Milner TA. The morphometry of a peptidergic transmitter system before and after seizure. I. Dynorphin B-like immunoreactivity in the hippocampal mossy fiber system. Hippocampus. 1999;9:255–276. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1999)9:3<255::AID-HIPO6>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przewlocki R, Kaminska B, Lukasiuk K, Nowicka DZ, Przewlocka B, Kaczmarek L, Lason W. Seizure related changes in the regulation of opioid genes and transcription factors in the dentate gyrus of rat hippocampus. Neurosci. 1995;68:73–81. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00144-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quadros PS, Pfau JL, Goldstein AY, de Vries GJ, Wagner CK. Sex differences in progesterone receptor expression: a potential mechanism for estradiol-mediated sexual differentiation. Endocrinology. 2002;143:3727–3739. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-211438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman E, Ploj K, Gustafsson L, Meyerson BJ, Nylander I. Variations in opioid peptide levels during the estrous cycle in Sprague-Dawley rats. Neuropeptides. 2006;40:195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romualdi P, Bregola G, Donatini A, Capobianco A, Simonato M. Region-specific changes in prodynorphin mRNA and ir-dynorphin A levels after kindled seizures. J Mol Neurosci. 1999a;13:69–75. doi: 10.1385/JMN:13:1-2:69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romualdi P, Donatini A, Capobianco A, Ferri S. Methamphetamine alters prodynorphin gene expression and dynorphin A levels in rat hypothalamus. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999b;365:183–186. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00905-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romualdi P, Lesa G, Ferri S. Chronic opiate agonists down-regulate prodynorphin gene expression in rat brain. Brain Res. 1991;563:132–136. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91525-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandin J, Nylander I, Georgieva J, Schött PA, Ögren SO, Terenius L. Hippocampal dynorphin B injections impair spatial learning in rats: A kappa-opioid receptor-mediated effect. Neurosci. 1998;85:375–382. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00605-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandstrom NJ, Williams CL. Memory retention is modulated by acute estradiol and progesterone replacement. Behav Neurosci. 2001;115:384–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharfman HE, MacLusky NJ. Similarities between actions of estrogen and BDNF in the hippocampus: coincidence or clue? Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharfman HE, MacLusky NJ. The influence of gonadal hormones on neuronal excitability, seizures, and epilepsy in the female. Epilepsia. 2006;47:1423–1440. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00672.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharfman HE, Mercurio TC, Goodman JH, Wilson MA, MacLusky NJ. J Neurosci. 2003;23:11641–11652. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-37-11641.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shughrue PJ, Lane MV, Merchenthaler I. Comparative distribution of estrogen receptor-α and -β mRNA in the rat central nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 1997;388:507–525. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19971201)388:4<507::aid-cne1>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simerly RB, Young BJ, Carr AM. Co-expression of steroid hormone receptors in opioid peptide-containing neurons correlates with patterns of gene expression during the estrous cycle. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1996;40:275–284. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(96)00057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonato M, Romualdi P. Dynorphin and epilepsy. Prog Neurobiol. 1996;50:557–583. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(96)00045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CC, McMahon LL. Estrogen-induced increase in the magnitude of long-term potentiation occurs only when the ratio of NMDA transmission to AMPA transmission is increased. J Neurosci. 2005;25:7780–7791. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0762-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohrabji F, Lewis DK. Estrogen-BDNF interactions: implications for neurodegenerative diseases. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2006;27:404–414. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohrabji F, Miranda RC, Toran-Allerand CD. Identification of a putative estrogen response element in the gene encoding brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:11110–11114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solum DT, Handa RJ. Localization of estrogen receptor alpha (ER alpha) in pyramidal neurons of the developing rat hippocampus. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2001;128:165–175. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(01)00171-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spampinato S, Canossa M, Campana G, Carboni L, Bachetti T. Estrogen regulation of prodynorphin gene expression in the rat adenohypophysis: effect of the antiestrogen tamoxifen. Endocrinology. 1995;136:1589–1594. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.4.7895668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svingos AL, Colago EEO, Pickel VM. Cellular sites for dynorphin activation of kappa-opioid receptors in the rat nucleus accumbens shell. J Neurosci. 1999;19:1804–1813. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-05-01804.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson LW. Brain Maps: Structure of the Rat Brain. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Tabori NE, Stewart LS, Znamensky V, Romeo RD, Alves SE, McEwen BS, Milner TA. Ultrastructural evidence that androgen receptors are located at extranuclear sites in the rat hippocampal formation. Neurosci. 2004;130:151–163. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanapat P, Hastings NB, Gould E. Ovarian steroids influence cell proliferation in the dentate gyrus of the adult female rat in a dose- and time-dependent manner. J Comp Neurol. 2005;481:252–265. doi: 10.1002/cne.20385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terman GW, Drake CT, Simmons ML, Milner TA, Chavkin C. Opioid modulation of recurrent excitation in the hippocampal dentate gyrus. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4379–4388. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-12-04379.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thureson-Klein AK, Klein RL. Exocytosis from neuronal large dense-core vesicles. Int Rev Cytol. 1990;121:67–126. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)60659-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibbetts TA, DeMayo F, Rich S, Conneely OM, O’Malley BW. Progesterone receptors in the thymus are required for thymic involution during pregnancy and for normal fertility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:12021–12026. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.12021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Reveron A, Hurd YL, Dow-Edwards DL. Gender differences in prodynorphin but not proenkephalin mRNA expression in the striatum of adolescent rats exposed to prenatal cocaine. Neurosci Lett. 2007;421:213–217. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Reveron A, Khalid S, Drake CT, Milner TA. Neuroscience Meeting Planner. Atlanta GA: Society for Neuroscience; 2006. Enkephalin and dynorphin immunoreactivities increase in the dorsal hippocampus in response to estrogens and colocalize with estrogen receptor beta in mossy fiber terminals; p. 724.6. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Reveron A, Khalid S, Williams TJ, Waters EM, Drake CT, McEwen B, Milner TA. Ovarian steroids modulate leu-enkephalin levels and target leu-enkephalinergic profiles in the female hippocampal mossy fiber pathway. Brain Res. 2008;1232:70–84. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.07.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towart LA, Alves SE, Znamensky V, Hayashi S. Cholinergic terminals in rat hippocampal formation contain estrogen receptor α. Society for Neuroscience Abstracts. 2002:28. [Google Scholar]

- Towart LA, Alves SE, Znamensky V, Hayashi S, McEwen BS, Milner TA. Cellular relationships between cholinergic terminals and estrogen receptor alpha in the dorsal hippocampus. The Journal of Comparitive Neurology. 2003;463:390–401. doi: 10.1002/cne.10753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traish AM, Wotiz HH. Monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies to human progesterone receptor peptide-(533–547) recognize a specific site in unactivated (8S) and activated (4S) progesterone receptor and distinguish between intact and proteolyzed receptors. Endocrinology. 1990;127:1167–1175. doi: 10.1210/endo-127-3-1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner CD, Bagnara JT. General Endocrinology. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan N, Pfaff DW. Membrane-initiated actions of estrogens in neuroendocrinology: emerging principles. Endocr Rev. 2007;28:1–19. doi: 10.1210/er.2005-0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner JJ, Caudle RM, Neumaier JF, Chavkin C. Stimulation of endogenous opioid release displaces mu receptor binding in rat hippocampus. Neurosci. 1990;37:45–53. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90190-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner JJ, Evans CJ, Chavkin C. Focal stimulation of the mossy fibers releases endogenous dynorphins that bind kappa1-opioid receptors in guinea pig hippocampus. J Neurochem. 1991;57:333–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb02132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner JJ, Terman GW, Chavkin C. Endogenous dynorphins inhibit excitatory neurotransmission and block LTP induction in the hippocampus. Nature. 1993;363:451–454. doi: 10.1038/363451a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walf AA, Rhodes ME, Frye CA. Ovarian steroids enhance object recognition in naturally cycling and ovariectomized, hormone-primed rats. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2006;86:35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren SG, Humphreys AG, Juraska JM, Greenough WT. LTP varies across the estrous cycle: Enhanced synaptic plasticity in proestrus rats. Brain Res. 1995;703:26–30. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters EM, Torres-Reveron A, McEwen B, Milner TA. Ultrastructural localization of extranuclear progestin receptors in the rat hippocampal formation. J Comp Neurol. 2008;511(1):34–46. doi: 10.1002/cne.21826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiland NG, Orikasa C, Hayashi S, McEwen BS. Distribution and hormone regulation of estrogen receptor immunoreactive cells in the hippocampus of male and female rats. J Comp Neurol. 1997;388:603–612. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19971201)388:4<603::aid-cne8>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisskopf MG, Zalutsky RA, Nicoll RA. The opioid peptide dynorphin mediates heterosynaptic depression of hippocampal mossy fibre synapses and modulates long-term potentiation. Nature. 1993;362:423–427. doi: 10.1038/362423a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley CS. Estrogen-mediated structural and functional synaptic plasticity in the female rat hippocampus. Horm Behav. 1998;34:140–148. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1998.1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley CS. Estradiol facilitates kainic acid-induced, but not flurothyl-induced, behavioral seizure activity in adult female rats. Epilepsia. 2000;41:510–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb00203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley CS, McEwen BS. Roles of estradiol and progesterone in regulation of hippocampal dendritic spine density during the estrous cycle in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1993;336:293–306. doi: 10.1002/cne.903360210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley CS, Schwartzkroin PA. Hormonal effects on the brain. Epilepsia. 1998;39(Suppl 8):S2–8. S2–S8. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1998.tb02601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakovleva T, Bazov I, Cebers G, Marinova Z, Hara Y, Ahmed A, Vlaskovska M, Johansson B, Hochgeschwender U, Singh IN, Bruce-Keller AJ, Hurd YL, Kaneko T, Terenius L, Ekstrom TJ, Hauser KF, Pickel VM, Bakalkin G. Prodynorphin storage and processing in axon terminals and dendrites. FASEB J. 2006;20:2124–2126. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6174fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuferov V, Zhou Y, LaForge KS, Spangler R, Ho A, Kreek MJ. Elevation of guinea pig brain preprodynorphin mRNA expression and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity by “binge” pattern cocaine administration. Brain Res Bull. 2001;55:65–70. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00496-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurkovsky L, Brown SL, Boyd SE, Fell JA, Korol DL. Estrogen modulates learning in female rats by acting directly at distinct memory systems. Neuroscience. 2007;144:26–37. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]