Abstract

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a common, functionally disabling disease with genetic and environmental contributors. It occurs in approximately 1% of the population and adversely affects quality of life, functional status, and survival. Beyond its impact on the joints, pulmonary involvement occurs regularly and is responsible for a significant portion of the morbidity and mortality. Although pulmonary infection and/or drug toxicity are frequent complications, lung disease directly associated with the underlying RA is more common. The airways, vasculature, parenchyma, and pleura can all be involved, with variable amounts of pathologic inflammation and fibrosis. The true adverse clinical impact of the most important of these directly associated disorders, RA-associated interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD), has only recently begun to reveal itself. Our knowledge of the underlying pathobiology and the impact of our current immunomodulatory and biologic therapies on the lung disease are less than incomplete. However, what is clear is the importance of progressive lung fibrosis in shortening survival and impairing quality of life in RA as well as in other connective tissue diseases. The impact of historically available and newer biologic therapies in altering the outcome of RA-ILD is unknown; translational studies focused on the pathobiology and clinical studies focused on the treatment of RA-ILD are needed.

Keywords: rheumatoid arthritis, interstitial lung disease

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a destructive, systemic, inflammatory disorder that is defined by its characteristic attack on diarthroidal joints. Over 2 million United States adults have RA, approximately 1% of the adult population. Its incidence ranges from 12 to 70 per 100,000 population in men and 25 to 130 per 100,000 population in women. Functional morbidity is high and mortality is increased; compared with the general population, the median survival is decreased by 10 to 11 years (1) and has not fundamentally changed over the last 40 years (2, 3). Financial costs are large; individual lifetime direct medical costs will approach $100,000, whereas total direct and indirect expenses associated with the disease in the United States are estimated to be over $3 billion annually (4).

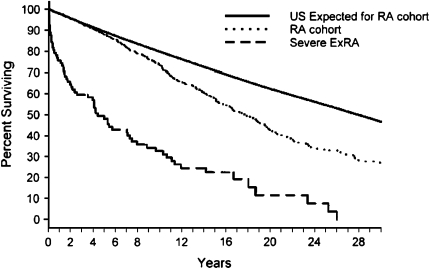

A major portion of RA's disease burden, including the excess mortality, appears to be due to its extraarticular manifestations (ExRA) (2, 5) (Figure 1). ExRA are common; the prevalence of clinically “severe” ExRA ranges up to 40% (6), with an incidence of 1 to 3 per 100 patient-years (7). Clinically, these manifestations are dominated by pulmonary, cardiac, and vascular changes.

Figure 1.

Survival in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and RA after first presentation of severe extraarticular disease manifestations (ExRA) compared with the expected survival from the general population. Reprinted by permission from Reference 5.

RA AND THE LUNG

Although cardiovascular disease is responsible for the majority of RA-related deaths (8), pulmonary complications are common and directly responsible for 10 to 20% of all mortality (1, 3, 9). When compared with control populations, patients with RA and with a respiratory disease have an estimated standardized mortality ratio that ranges from 2.5 to 5.0 (1, 3). The majority of lung disease occurs within the first 5 years after the initial diagnosis, and may be a presenting manifestation in 10 to 20% of patients.

Both pulmonary infection and drug-induced lung disease are frequent (10, 11). However, when the focus is on those disorders directly associated with RA, an additional large group of diseases appear. These can be approached both anatomically and mechanistically.

RA affects all of the anatomic compartments of the lung (Table 1). The prevalence of a particular complication varies based on the characteristics of the population studied, the definition of lung disease used, and the sensitivity of the clinical investigations employed. In unselected populations, up to a third of subjects describe important respiratory symptoms (12), but two-thirds or more may have significant radiographic abnormalities on high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) (12, 13), with 20% showing a pattern of fibrosing lung disease (14). Pulmonary physiologic abnormalities occur less frequently, but when present, are poor prognostic indicators (15–17).

TABLE 1.

PRIMARY AND SECONDARY PLEUROPARENCHYMAL COMPLICATIONS OF RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS

| Pleural disease |

| Pleural effusions |

| Pleural fibrosis |

| Airway disease |

| Cricoarytenoid arthritis |

| Bronchiectasis |

| Follicular bronchiolitis |

| Bronchiolitis obliterans |

| Diffuse panbronchiolitis |

| Interstitial lung disease |

| Usual interstitial pneumonia |

| Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia |

| Organizing pneumonia |

| Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia |

| Diffuse alveolar damage |

| Acute eosinophilic pneumonia |

| Apical fibrobullous disease |

| Amyloid |

| Rheumatoid nodules |

| Pulmonary vascular disease |

| Pulmonary hypertension |

| Vasculitis |

| Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage with capillaritis |

| Secondary pulmonary complications |

| Opportunistic infections |

| Pulmonary tuberculosis |

| Atypical mycobacterial infections |

| Nocardiosis |

| Aspergillosis |

| Pneumocystis jeroveci pneumonia |

| Cytomegalovirus pneumonitis |

| Drug toxicity |

| Methotrexate |

| Gold |

| d-penicillamine |

| Sulfasalazine |

AIRWAY COMPLICATIONS (CRICOARYTENOID ARTHRITIS, BRONCHIECTASIS, BRONCHIOLITIS)

RA can cause upper, lower, and small, distal airway disease (18–20). Cricoarytenoid arthritis may present with hoarseness, pain, change in voice, or globus. Upper airway complications, such as rheumatoid nodules and vocal cord paresis, also occur. There is a high incidence of radiographic bronchiectasis, up to 30% in some HRCT studies (21–23); however, clinically significant disease is much less frequent. Symptoms are identical to other causes of bronchiectasis and include cough, sputum production, frequent episodes of infection, and hemoptysis. Small airway disease with physiologic obstruction is common (20, 24, 25), and presents with exertional dyspnea, a nonproductive cough, or wheezing. HRCT is suggestive of small airway disease when it demonstrates centrilobular nodules, hyperinflation, and heterogenous airtrapping. Pathologically, both fibrosing (obliterative or constrictive bronchiolitis) and cellular (diffuse panbronchiolitis and follicular bronchiolitis) have been well described (22, 25, 26).

PLEURAL DISEASE (PLEURITIS, EFFUSIONS)

Pleurisy, pleuritis, and effusions occur in approximately 5% of patients (27). Effusions tend to be small, asymmetric, and to wax and wane. Pleural fluid analysis generally reveals a low glucose (< 50 mg/dl), low pH (< 7.30), high lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (> 1,000), and high rheumatoid factor titers (28). Effusions in patients with RA cannot be assumed to be RA associated; infections, empyema, sterile empyema, chylothorax, and congestive heart failure (CHF) are all seen. Fibrothorax and trapped lung are rare.

PULMONARY VASCULAR DISEASE

Isolated, pulmonary hypertension due to a primary vasculopathy, such as one sees in systemic lupus erythematosis (SLE) and limited scleroderma is exceedingly rare (29). Capillaritis/alveolar hemorrhage occurs and its clinical presentation overlaps with infectious pneumonia.

PARENCHYMAL LUNG DISEASE

Rheumatoid (necrobiotic) nodules are found in up to 20% of patients (30, 31). They are pathologically granulomatous, consisting of collections of macrophages, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes around a necrotic core (32). Nodules typically range from a millimeter to centimeters in size, and are usually asymptomatic. However, complications include pneumothorax, hydropneumothorax, sterile empyema, and hemoptysis. Nodules identified on HRCT must be distinguished from malignant and infectious lesions. Caplan's syndrome refers to conglomerations of nodules seen in patients with the combination of RA and pneumoconiosis (33). Aspiration pneumonitis and apical fibrobullous disease, such as that which occurs in ankylosing spondylitis, have been described.

RA–INTERSTITIAL LUNG DISEASE

The prevalence of interstitial lung disease (ILD) varies depending on the criteria used to establish the diagnosis. In retrospective studies, clinically significant ILD has been described in approximately 7% of subjects (6), whereas autopsy studies have described a prevalence of up to 35% (9). Prospective studies that use HRCT, the most sensitive technique for the detection of RA-related lung disease (12, 34), to specifically screen for disease have shown a much higher prevalence. In unselected populations, specific features of ILD will be seen in up to two-thirds of individuals (12, 13).

Unlike most other connective tissue diseases, the usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) pattern is more commonly seen on surgical lung biopsy than nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP). Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia (LIP) and organizing pneumonia (OP) have also been described (35, 36). Acute interstitial pneumonia (a.k.a. Haman-Rich syndrome), on the other hand, is quite uncommon, but presents with a rapid and aggressive course that frequently results in death.

PREDICTORS OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF RA-ILD

Clinical, genetic, and environmental factors have been used to predict the development of lung disease in RA. Sex influences both the risk as well as the pattern of organ involvement. Both rheumatoid nodules and RA-ILD are more commonly seen in men (37, 38). Active or previous tobacco smoking is an independent risk factor for the development of RA (39, 40), its severity, and its rheumatoid factor (RF) seropositivity (41, 42). A mechanistic connection has also been proposed for a relationship between tobacco smoke, the HLA-DRB1 “shared epitope” (SE), anticyclic citrullinated peptide antibody (anti-CCP), and the development of RA (43). The combination of a history of tobacco smoking and the presence of two copies of the HLA-DR SE genes increased the risk for RA 21-fold compared with the risk among nonsmokers carrying no SE genes. The relationship between tobacco smoke and the development of RA-ILD is unclear. Smoking has been independently associated with the development of radiographic and physiologic abnormalities consistent with ILD (odds ratio for ⩾ 25 pack-years, 3.76; 95% confidence interval, 1.59, 8.88) (42). However, more recent studies have not confirmed this association (34, 44) and the development of ILD clearly does not require smoke exposure (45).

Approximately half of patients with RA have specific serologic abnormalities a median of 4.5 years before the onset of joint symptoms. The finding of an elevated serum level of IgM- RF or anti-CCP in a healthy individual implies a high risk for the development of RA (46). Patients with anti-CCP antibodies or IgA and/or IgM RF autoantibodies represent a group at highest risk for the development of clinically significant articular and extraarticular RA (47, 48). High-titer RF has been associated with the presence of RA-ILD (49) and a decreased DlCO (50). The role of anti-CCP antibodies in the lung is unknown. However, in otherwise healthy smokers, up to 25% of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid cells express citrulline compared with no expression of citrulline in healthy nonsmokers (43), suggesting that besides the joint, another antigenic source for anti-CCP antibodies is the lung.

CLINICAL RELEVANCE OF ILD

Given the disconnect between the high prevalence of ILD as defined in radiographic screening studies and the less frequent mortality directly attributable to it, a variety of clinical phenotypes must exist. One approach to defining specific phenotypes is the pattern of disease seen on surgical lung biopsy. In RA-ILD, cellular inflammatory, fibrosing, and mixed changes are seen, and these pathologic patterns fully overlap with those seen in the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (IIPs) (35, 36, 51); UIP, fibrosing and cellular NSIP, OP and diffuse alveolar damage, LIP, and desquamative interstitial pneumonia (DIP) patterns have all been described.

THE IMPORTANCE OF FIBROTIC VERSUS CELLULAR LUNG DISEASE

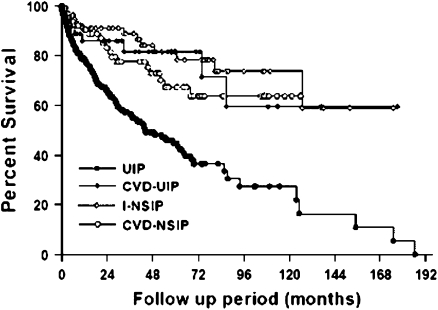

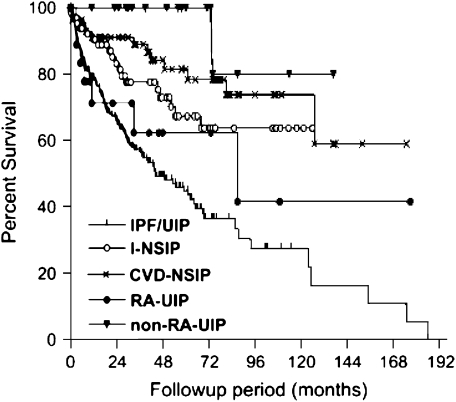

The information provided by these pathologic patterns is important; in the IIPs, the pattern seen on surgical lung biopsy is the most important predictor of early mortality, with patterns characterized by fibrosis (e.g., UIP, fibrosing NSIP) having a worse prognosis than those characterized by cellular disease (e.g., cellular NSIP). The pathologic patterns seen in RA-ILD may also have prognostic significance. Available data have suggested that the outcome of patients with RA-ILD ranges from marginally worse (52), to similar (17), or even better than that seen in the IIPs. A recent article by Park and colleagues contains the largest number of well-phenotyped subjects and supports the hypothesis that the prognosis of subjects with collagen vascular disease (CVD)–ILD, and particularly those with CVD-UIP, is better than that of patients with idiopathic UIP (idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis [IPF]) (Figure 2) (53). As a subgroup, the RA subjects with ILD also had a better prognosis than those with IPF. However, consistent with data from previous studies (35, 36, 54), those subjects with RA and with UIP pattern pathology had a survival similar to matched subjects with IPF (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Comparison of the survival curves of all subject groups. CVD-NSIP = nonspecific interstitial pneumonia associated with collagen vascular disease; CVD-UIP = usual interstitial pneumonia associated with collagen vascular disease; I-NSIP = idiopathic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia; UIP = usual interstitial pneumonia. Reprinted by permission from Reference 53.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the Kaplan-Meier survival curves between the subject groups and the UIP pattern associated with rheumatoid arthritis (RA-UIP). CVD-NSIP = nonspecific interstitial pneumonia associated with collagen vascular diseases; I-NSIP = idiopathic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia; IPF/UIP = idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis/usual interstitial pneumonia; non–RA-UIP = usual interstitial pneumonia in the patients with non–rheumatoid arthritis–collagen vascular diseases. The statistical significances between groups were as follows: RA-UIP versus non–RA-UIP, p = 0.015; RA-UIP versus CVD-NSIP, p = 0.043; RA-UIP versus I-NSIP, not significant; RA-UIP versus IPF/UIP, not significant. Reprinted by permission from Reference 53.

The pattern of radiographic abnormality seen on HRCT in RA has proved to be an excellent predictor of the underlying pathologic pattern. Four overall radiographic patterns have been described: UIP, NSIP, OP, and bronchiolitis. Three of the radiographic patterns, UIP, NSIP, and OP, conform to those seen in IIP, and strongly correlate with the underlying pathology (55, 56). Similar to the pathologic patterns, these radiographic patterns also appear to predict progression and outcome in both IIP (57) and RA-ILD (16).

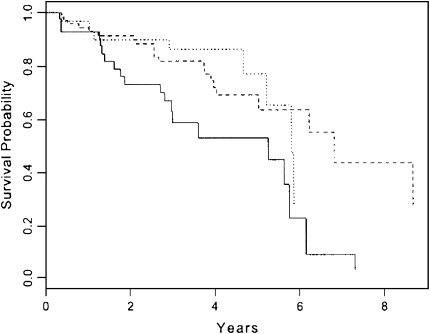

THE IMPORTANCE OF PROGRESSIVE FIBROSIS

A variety of clinical measures have been used to define disease progression in lung fibrosis, with most coming from studies of IPF. Although these same measures have not been studied in RA-ILD, the impact and similarity of the underlying pathologic patterns between RA and IIP suggest that this approach is defensible and clinically relevant. Progressive dyspnea as measured by a standardized questionnaire is a strong predictor of shortened survival (58) (Figure 4). The declining size of the lung as measured by plain chest radiographic study (59) as well as the extent of disease seen on HRCT (60) are powerful predictors, as are serial changes in pulmonary physiology with declines in forced vital capacity (57, 61, 62). These changes over time are stronger prognostic markers than baseline measures (58).

Figure 4.

Cox model–based survival estimates for patients across three levels of FVC percentage change adjusted for usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP), onset of symptoms, female sex, and positive smoking history. Average patient profiles for UIP, onset of symptoms, sex, and smoking were used in the estimates. Dotted line, at least 10% increase in FVC; solid line, at least 10% decrease in FVC; dashed line, less than 10% increase or decrease in FVC; p = 0.01. Reprinted by permission from Reference 57.

BIOLOGIC MECHANISMS PORTRAYED BY PATHOLOGY

One hypothesis for the development of lung fibrosis in RA is that a cellular inflammatory process is required for and initiates a secondary fibroproliferative process, and that the fibroproliferative process may become progressive and independent of its initiating cause. A similar paradigm has been hypothesized in patients with hypersensitivity pneumonitis. In these patients, reversible granulomatous inflammation is generally seen. However, once the fibroproliferative process begins, the clinical course and gene expression profile become similar to those of IPF, the prototypical fibrosing lung disease, and the disease becomes unresponsive to immunosuppression (63, 64).

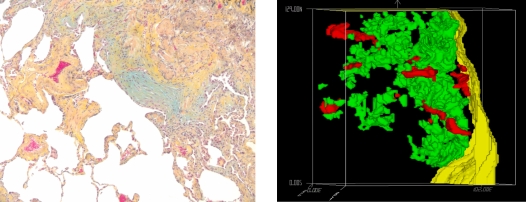

The importance of individual histopathologic features in predicting survival or response to therapy has been investigated in UIP pattern fibrosis. The presence and number of fibrotic foci (the proposed “leading edge” of fibrosis) have been shown to correlate with mortality. The UIP lung in the connective tissue diseases (CTD) has been suggested to have fewer fibroblast foci (65). Although these have been proposed as isolated sites of acute lung injury, recent data suggest that, in three dimensions, these individual foci are physically connected and form a growing reticulum (Figure 5) (66). The impact of a variety of specific pathologic features in patients with UIP pathologic pattern (in IPF) and their impact on the response to immunomodulatory therapy have also been investigated. The presence of areas of lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate is associated with physiologic improvement in response to cyclophosphamide and corticosteroid therapy, whereas fibroblast foci and areas of airspace organization were associated with a decline in function (67). However, it has been previously appreciated that treatment of IPF with cyclophosphamide and corticosteroids has no impact on survival (68), further evidence of the outcome distinction between cellular or fibrotic patterns of injury/repair.

Figure 5.

Fibroblast foci appear to be isolated accumulations of matrix and myofibroblasts in usual interstitial pneumonia (left); however, when reconstructed in three dimensions, they appear to be physically connected and forming a reticulum. Reprinted by permission from Reference 66.

CURRENT THERAPIES FOR RA-ILD

Given the diverse pathologic and clinical phenotypes of RA-ILD, it should be no surprise that there are few data on the efficacy of any specific therapy. However, what is clear is that effective treatment of the joint disease should not be used as a surrogate for beneficial or even adequate treatment of the ILD. Just as clinically important diffuse lung disease can precede the development of active joint disease in RA, progressive ILD can occur despite the absence of synovitis. This strongly argues for continued regular pulmonary follow-up of known lung disease in patients with even excellent control of their joint disease as well as early pulmonary referral when respiratory symptoms develop or progress in patients with RA, regardless of the activity of their joint disease.

There are few data about the response of RA-ILD to any of the standard regimens used to treat the articular disease. Case reports describe responses to almost all of the specific RA treatments; however, these are outnumbered by the case reports and series describing the development of drug-induced lung disease secondary to virtually the same drugs. Thirty percent of patients will have their joint disease controlled by methotrexate. Its efficacy in some patients with RA-ILD is supported by a handful of studies, although it is suggested to result in pulmonary toxicity in approximately 5% of patients (69). Some have questioned whether this pulmonary toxicity is actually a reflection of progressive lung injury due to RA (16, 70, 71).

Fifty percent or more of patients with RA will require a tumor necrosis factor-α antagonist within the first year or more of therapy to control their joint disease (5, 72). Although this therapy has been hinted to slow the progression of RA-related pulmonary fibrosis (73), it has also been associated with the development of fulminate respiratory failure (74). In several case reports, corticosteroids have been suggested as a treatment of the RA-ILD characterized by organizing pneumonia pathologic pattern (75, 76). Cyclosporine has been used to treat both acute pneumonitis and progressive pulmonary fibrosis with success in individual patients (5, 77–79). The use of rituximab and abatacept for the treatment of refractory RA synovitis is supported by current data, but their use in the treatment of the pulmonary manifestations of RA remains unclear (80–83). The use of immunosuppressant or biologic agents in the treatment of RA and RA-ILD is associated with an increase in the incidence of pulmonary infections (11). Given the clinical impact of RA-ILD, and the absence of definitive data on its treatment, prospective, controlled studies are necessary to guide the field.

Supported by NHLBI SCOR HL67671.

Conflict of Interest Statement: K.K.B. has served as a consultant for and a speaker for the following companies interested in IPF or autoimmune-mediated interstitial lung disease: Actelion, Amgen, Genzyme, Wyeth, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, and Lung Rx. He or his institution have received grants to support the performance of treatment trials in IPF or autoimmune-mediated lung disease from Actelion, Intermune, Biogen, and Genzyme.

References

- 1.Minaur NJ, Jacoby RK, Cosh JA, Taylor G, Rasker JJ. Outcome after 40 years with rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective study of function, disease activity, and mortality. J Rheumatol Suppl 2004;69:3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gabriel SE, Crowson CS, Kremers HM, Doran MF, Turesson C, O'Fallon WM, Matteson EL. Survival in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based analysis of trends over 40 years. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:54–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sihvonen S, Korpela M, Laippala P, Mustonen J, Pasternack A. Death rates and causes of death in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study. Scand J Rheumatol 2004;33:221–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Update: direct and indirect costs of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions: United States, 1997. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2004;53:388–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turesson C, Matteson EL. Management of extra-articular disease manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2004;16:206–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turesson C, O'Fallon WM, Crowson CS, Gabriel SE, Matteson EL. Extra-articular disease manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis: incidence trends and risk factors over 46 years. Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:722–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turesson C, Jacobsson LT. Epidemiology of extra-articular manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol 2004;33:65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maradit-Kremers H, Nicola PJ, Crowson CS, Ballman KV, Gabriel SE. Cardiovascular death in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:722–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suzuki A, Ohosone Y, Obana M, Mita S, Matsuoka Y, Irimajiri S, Fukuda J. Cause of death in 81 autopsied patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 1994;21:33–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolfe F, Caplan L, Michaud K. Treatment for rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of hospitalization for pneumonia: associations with prednisone, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, and anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:628–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winthrop KL. Serious infections with antirheumatic therapy: are biologicals worse? Ann Rheum Dis 2006;65:iii54–iii57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zrour SH, Touzi M, Bejia I, Golli M, Rouatbi N, Sakly N, Younes M, Tabka Z, Bergaoui N. Correlations between high-resolution computed tomography of the chest and clinical function in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: prospective study in 75 patients. Joint Bone Spine 2005;72:41–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bilgici A, Ulusoy H, Kuru O, Celenk C, Unsal M, Danaci M. Pulmonary involvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int 2005;25:429–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dawson JK, Fewins HE, Desmond J, Lynch MP, Graham DR. Fibrosing alveolitis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis as assessed by high resolution computed tomography, chest radiography and pulmonary function tests. Thorax 2001;56:622–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hakala M. Poor prognosis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis hospitalized for interstitial lung fibrosis. Chest 1988;93:114–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dawson JK, Graham DR, Desmond J, Fewins HE, Lynch MP. Investigation of the chronic pulmonary effects of low-dose oral methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective study incorporating HRCT scanning and pulmonary function tests. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2002;41:262–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kocheril SV, Appleton BE, Somers EC, Kazerooni EA, Flaherty KR, Martinez FJ, Gross BH, Crofford LJ. Comparison of disease progression and mortality of connective tissue disease-related interstitial lung disease and idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. Arthritis Rheum 2005;53:549–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vergnenegre A, Pugnere N, Antonini MT, Arnaud M, Melloni B, Treves R, Bonnaud F. Airway obstruction and rheumatoid arthritis. Eur Respir J 1997;10:1072–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geddes DM, Webley M, Emerson PA. Airways obstruction in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 1979;38:222–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perez T, Remy-Jardin M, Cortet B. Airways involvement in rheumatoid arthritis: clinical, functional and HRCT findings. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;157:1658–1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Remy-Jardin M, Remy J, Cortet B, Mauri F, Delcambre B. Lung changes in rheumatoid arthritis: CT findings. Radiology 1994;193:375–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayakawa H, Sato A, Imokawa S, Toyoshima M, Chida K, Iwata M. Bronchiolar disease in rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996;154:1531–1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shadick NA., Fanta CH, Weinblatt ME, O'Donnell W, Coblyn JS. Bronchiectasis: a late feature of severe rheumatoid arthritis. Medicine 1994;73:161–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Radoux V, Menard HA, Begin R, Decary F, Koopman WJ. Airways disease in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Rheum 1987;30:249–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwarz MI, Lynch DA, Tuder R. Bronchiolitis obliterans: the lone manifestation of rheumatoid arthritis. Eur Respir J 1994;7:817–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Homma S, Kawabata M, Kishi K, Tsuboi E, Narui K, Nakatani T, Uekusa T, Saiki S, Nakata K. Diffuse panbronchiolitis in rheumatoid arthritis. Eur Respir J 1998;12:444–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joseph J, Sahn SA. Connective tissue diseases and the pleura. Chest 1993;104:262–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Helmers R, Galvin J, Hunninghake GW. Pulmonary manifestations associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Chest 1991;100:235–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morikawa J, Kitamura K, Habuchi Y, Tsujimura Y, Minamikawa T, Takamatsu T. Pulmonary hypertension in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Chest 1988;93:876–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walters MN, Ojeda VJ. Pleuropulmonary necrobiotic rheumatoid nodules. A review and clinicopathological study of six patients. Med J Aust 1986;144:648–651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ziff M. The rheumatoid nodule. Arthritis Rheum 1990;33:761–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anaya JM, Diethelm L, Ortiz L, Gutierrez M, Citera G, Welsh RA, Espinoza LR. Pulmonary involvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1995;24:242–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Caplan A. Certain unusual radiographic appearances in the chest of coal-miners suffering from rheumatoid arthritis. Thorax 1953;8:19–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Biederer J, Schnabel A, Muhle C, Gross WL, Heller M, Reuter M. Correlation between HRCT findings, pulmonary function tests and bronchoalveolar lavage cytology in interstitial lung disease associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Eur Radiol 2004;14:272–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee HK, Kim DS, Yoo B, Seo JB, Rho JY, Colby TV, Kitaichi M. Histopathologic pattern and clinical features of rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease. Chest 2005;127:2019–2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yousem SA, Colby TV, Carrington CB. Lung biopsy in rheumatoid arthritis. Am Rev Respir Dis 1985;131:770–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weyand CM, Schmidt D, Wagner U, Goronzy JJ. The influence of sex on the phenotype of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1998;41:817–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gabbay E, Tarala R, Will R, Carroll G, Adler B, Cameron D, Lake FR. Interstitial lung disease in recent onset rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997;156:528–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vessey MP, Villard-Mackintosh L, Yeates D. Oral contraceptives, cigarette smoking and other factors in relation to arthritis. Contraception 1987;35:457–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Albano SA, Santana-Sahagun E, Weisman MH. Cigarette smoking and rheumatoid arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2001;31:146–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harrison BJ. Influence of cigarette smoking on disease outcome in rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2002;14:246–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saag KG, Kolluri S, Koehnke RK, Georgou TA, Rachow JW, Hunninghake GW, Schwartz DA. Rheumatoid arthritis lung disease. Determinants of radiographic and physiologic abnormalities. Arthritis Rheum 1996;39:1711–1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Klareskog L, Stolt P, Lundberg K, Kallberg H, Bengtsson C, Grunewald J, Ronnelid J, Harris HE, Ulfgren AK, Rantapaa-Dahlqvist S, et al. A new model for an etiology of rheumatoid arthritis: smoking may trigger HLA-DR (shared epitope)-restricted immune reactions to autoantigens modified by citrullination. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:38–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McDonagh J, Greaves M, Wright AR, Heycock C, Owen JP, Kelly C. High resolution computed tomography of the lungs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and interstitial lung disease. Br J Rheumatol 1994;33:118–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ayhan-Ardic FF, Oken O, Yorgancioglu ZR, Ustun N, Gokharman FD. Pulmonary involvement in lifelong non-smoking patients with rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis without respiratory symptoms. Clin Rheumatol 2006;25:213–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nielen MM, van Schaardenburg D, Reesink HW, van de Stadt RJ, van der Horst-Bruinsma IE, de Koning MH, Habibuw MR, Vandenbroucke JP, Dijkmans BA. Specific autoantibodies precede the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis: a study of serial measurements in blood donors. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:380–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Manfredsdottir VF, Vikingsdottir T, Jonsson T, Geirsson AJ, Kjartansson O, Heimisdottir M, Sigurdardottir SL, Valdimarsson H, Vikingsson A. The effects of tobacco smoking and rheumatoid factor seropositivity on disease activity and joint damage in early rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45:734–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Masdottir B, Jonsson T, Manfredsdottir V, Vikingsson A, Brekkan A, Valdimarsson H. Smoking, rheumatoid factor isotypes and severity of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2000;39:1202–1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sakaida H. IgG rheumatoid factor in rheumatoid arthritis with interstitial lung disease [Japanese]. Ryumachi 1995;35:671–677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Luukkainen R, Saltyshev M, Pakkasela R, Nordqvist E, Huhtala H, Hakala M. Relationship of rheumatoid factor to lung diffusion capacity in smoking and non-smoking patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol 1995;24:119–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society international multidisciplinary consensus classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;165:277–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hubbard R, Venn A. The impact of coexisting connective tissue disease on survival in patients with fibrosing alveolitis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2002;41:676–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Park JH, Kim DS, Park IN, Jang SJ, Kitaichi M, Nicholson AG, Colby TV. Prognosis of fibrotic interstitial pneumonia: idiopathic versus collagen vascular disease-related subtypes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;175:705–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hakala M, Paakko P, Huhti E, Tarkka M, Sutinen S. Open lung biopsy of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol 1990;9:452–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Akira M, Sakatani M, Hara H. Thin-section CT findings in rheumatoid arthritis-associated lung disease: CT patterns and their courses. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1999;23:941–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hunninghake GW, Lynch DA, Galvin JR, Gross BH, Muller N, Schwartz DA, King TE Jr, Lynch JP III, Hegele R, Waldron J, et al. Radiologic findings are strongly associated with a pathologic diagnosis of usual interstitial pneumonia. Chest 2003;124:1215–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Flaherty KR, Mumford JA, Murray S, Kazerooni EA, Gross BH, Colby TV, Travis WD, Flint A, Toews GB, Lynch IJ, et al. Prognostic implications of physiologic and radiographic changes in idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;28:28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Collard HR, King TE Jr, Bartelson BB, Vourlekis JS, Schwarz MI, Brown KK. Changes in clinical and physiologic variables predict survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;168:538–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kawabata H, Nagai S, Hayashi M, Nakamura H, Nagao T, Shigematsu M, Kitaichi M, Izumi T. Significance of lung shrinkage on CXR as a prognostic factor in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respirology 2003;8:351–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lynch DA, David Godwin J, Safrin S, Starko KM, Hormel P, Brown KK, Raghu G, King TE Jr, Bradford WZ, Schwartz DA, et al. High-resolution computed tomography in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: diagnosis and prognosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;172:488–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Martinez F, Safrin S, Weycker D, Starko KM, Bradford WZ, King TE Jr, Flaherty KR, Schwartz DA, Noble PW, Raghu G, et al. The clinical course of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:963–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Latsi PI, Du Bois RM, Nicholson AG, Colby TV, Bisirtzoglou D, Nikolakopoulou A, Veeraraghavan S, Hansell DM, Wells AU. Fibrotic idiopathic interstitial pneumonia: the prognostic value of longitudinal functional trends. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;5:5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Selman M, Pardo A, Barrera L, Estrada A, Watson SR, Wilson K, Aziz N, Kaminski N, Zlotnik A. Gene expression profiles distinguish idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis from hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;173:188–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vourlekis JS, Schwarz MI, Cherniack RM, Curran-Everett D, Cool CD, Tuder RM, King TE Jr, Brown KK. The effect of pulmonary fibrosis on survival in patients with hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Am J Med 2004;116:662–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Flaherty KR, Colby TV, Travis WD, Toews GB, Mumford J, Murray S, Thannickal VJ, Kazerooni EA, Gross BH, Lynch JP III, et al. Fibroblastic foci in usual interstitial pneumonia: idiopathic versus collagen vascular disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;167:1410–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cool CD, Groshong SD, Rai PR, Henson PM, Stewart JS, Brown KK. Fibroblast foci are not discrete sites of lung injury or repair: the fibroblast reticulum. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;174:654–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Collard HR, Cool CD, Leslie KO, Curran-Everett D, Groshong S, Brown KK. Organizing pneumonia and lymphoplasmacytic inflammation predict treatment response in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Histopathology 2007;50:258–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Collard HR, Ryu JH, Douglas WW, Schwarz MI, Curran-Everett D, King TE Jr, Brown KK. Combined corticosteroid and cyclophosphamide therapy does not alter survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 2004;125:2169–2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lateef O, Shakoor N, Balk RA. Methotrexate pulmonary toxicity. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2005;4:723–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Khadadah ME, Jayakrishnan B, Al-Gorair S, Al-Mutairi M, Al-Maradni N, Onadeko B, Malaviya AN. Effect of methotrexate on pulmonary function in patients with rheumatoid arthritis–a prospective study. Rheumatol Int 2002;22:204–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Beyeler C, Jordi B, Gerber NJ, Im Hof V. Pulmonary function in rheumatoid arthritis treated with low-dose methotrexate: a longitudinal study. Br J Rheumatol 1996;35:446–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.De Rycke L, Verhelst X, Kruithof E, Van den Bosch F, Hoffman IE, Veys EM, De Keyser F. Rheumatoid factor, but not anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies, is modulated by infliximab treatment in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:299–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vassallo R, Matteson E, Thomas CF Jr. Clinical response of rheumatoid arthritis-associated pulmonary fibrosis to tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibition. Chest 2002;122:1093–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Peno-Green L, Lluberas G, Kingsley T, Brantley S. Lung injury linked to etanercept therapy. Chest 2002;122:1858–1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Miyagawa Y, Nagata N, Nakanishi Y, Aizawa H, Satake M, Hayashi S, Yagawa Y. A case of steroid-responsive organizing pneumonia in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis showing migratory infiltration and normal glucose levels in pleural effusions. Br J Rheumatol 1993;32:829–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kondoh Y, Taki F, Ando M, Ikuta N, Matsumoto K, Tanaka H, Suzuki K, Suzuki R, Yamaki K, Takagi K, et al. A case of bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis who responded to corticosteroid and immunosuppressant therapy [in Japanese].Nihon Kyobu Shikkan Gakkai Zasshi 1992;30:1165–1170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chang HK, Park W, Ryu DS. Successful treatment of progressive rheumatoid interstitial lung disease with cyclosporine: a case report. J Korean Med Sci 2002;17:270–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Puttick MP, Klinkhoff AV, Chalmers A, Ostrow DN. Treatment of progressive rheumatoid interstitial lung disease with cyclosporine. J Rheumatol 1995;22:2163–2165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ogawa D, Hashimoto H, Wada J, Ueno A, Yamasaki Y, Yamamura M, Makino H. Successful use of cyclosporin A for the treatment of acute interstitial pneumonitis associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2000;39:1422–1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cambridge G, Stohl W, Leandro MJ, Migone TS, Hilbert DM, Edwards JC. Circulating levels of B lymphocyte stimulator in patients with rheumatoid arthritis following rituximab treatment: relationships with B cell depletion, circulating antibodies, and clinical relapse. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:723–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Higashida J, Wun T, Schmidt S, Naguwa SM, Tuscano JM. Safety and efficacy of rituximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis refractory to disease modifying antirheumatic drugs and anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha treatment. J Rheumatol 2005;32:2109–2115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Edwards JC, Szczepanski L, Szechinski J, Filipowicz-Sosnowska A, Emery P, Close DR, Stevens RM, Shaw T. Efficacy of B-cell-targeted therapy with rituximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2004;350:2572–2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Genovese MC, Becker JC, Schiff M, Luggen M, Sherrer Y, Kremer J, Birbara C, Box J, Natarajan K, Nuamah I, et al. Abatacept for rheumatoid arthritis refractory to tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibition. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1114–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]