Abstract

Most cystic fibrosis (CF) drug development has been based upon functional outcomes (e.g., FEV1) rather than structural changes. This functional approach has the limitation of being insensitive of early changes in lung disease. Computer tomography (CT) scanning affords the opportunity to establish a new paradigm to stage the illness (and target populations) based upon morphology. Using this concept, treatment regimens would be tested to prevent progression, reverse early changes, or stabilize established structural damage. In this setting, imaging biomarkers could play a key role. This article reviews the potential uses of CT scanning in the different phases of drug development (phase 1 to 4 studies). In early-phase studies (i.e., human pharmacology and therapeutic exploratory trials), CT could be used to provide preliminary data on mechanisms of action and efficacy. For large phase 3, therapeutic, confirmatory trials, CT scans are less likely to be the primary endpoint, but may play a supportive role in clinical efficacy measures and subset analyses (e.g., infants). For postmarketing therapeutic use trials, CT scans could play an important role in defining long-term efficacy in subpopulations, such as infants and children. Further steps need to be taken to optimize imaging biomarkers. These steps include establishing standard procedures across multiple research sites, centralized reading centers, and a common scoring system. To validate optimal CT parameter(s), the CF community must continue to collect CT data in phase 1 and 2 trials documenting response to therapeutic intervention. In addition, there is a need for additional longitudinal epidemiology studies to establish the association of CT changes with other outcome measures, such as pulmonary function tests, quality of life measures, and mortality.

Keywords: cystic fibrosis, lung imaging, clinical trials

Biomarkers are defined as “a characteristic that is objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of normal biologic process, pathogenic process, or pharmacologic responses to a therapeutic intervention” (1). Lung imaging measures, such as computer tomography (CT), have been validated as useful biomarkers in therapeutic trials involving other diseases (2), and validation in cystic fibrosis (CF) should be achievable (3). Although biomarkers and surrogate endpoints are often used interchangeably, surrogate status should be reserved for “laboratory measurement or physical sign that is used in a therapeutic trial as a substitute for a clinically meaningful endpoint” (4). To validate a surrogate endpoint, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires that the measure be biologically plausible, reflect clinical severity, improve rapidly with effective therapy, and correlate with a true outcome (5). FEV1 is the most well studied and validated surrogate in CF (6, 7).

Does CT fulfill these criteria in CF? CT is biologically plausible and closely reflects true pathologic changes in the lung (8). Airway morphology is distinct, even in infancy, between patients with CF and those without CF (9), and abnormalities in patients with CF demonstrate progression over time (10), reflecting clinical severity. Several studies have evaluated correlation of changes in CT with lung function parameters (11–13). In general, CT was found to be more sensitive to early changes in CF lung disease, often preceding any change in lung function (12–14). A recent study (15) demonstrated a correlation between CT score and frequency of pulmonary exacerbation, a true clinical outcome in CF. One criterion lacking in the validation process in CF is the coupling of a change in CT parameters (quantitative or qualitative) to an effective therapy. Several small studies of CT scanning before and after clinical interventions have been encouraging (16, 17), but verification in larger, multicenter studies is needed. Thus, for the purposes of this presentation, CT will be designated a biomarker with the future goal of achieving surrogate status.

The remainder of this article will focus on the therapeutic development process required for registration with the FDA and where imaging techniques may be most useful as biomarkers. A general overview of the phases of any clinical development plan is presented to set the stage for discussions of current and future uses of imaging outcomes. Subsequently, a new paradigm is proposed for staging illness based upon structure rather than function where imaging biomarkers will play a key role.

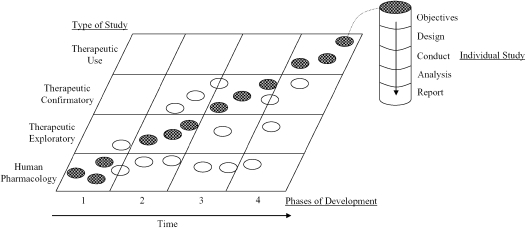

The clinical development plan for any new therapy progresses through three phases before drug approval, and a fourth phase after drug approval. Figure 1, reproduced from the International Committee on Harmonization Guidance document E8 (18), displays these developmental phases and the type of studies performed at each phase.

Figure 1.

Correlation between development phases and types of study. This matrix graph illustrates the relationship between the phases of development and types of study by objective that may be conducted during each clinical development of a new medicinal product. The shaded circles show the types of study usually conducted in a certain phase of development; the open circles show certain types of study that may be conducted in that phase of development but are less usual. Each circle represents an individual study. To illustrate the development of a single study, one circle is joined by a dotted line to an inset column that depicts the elements and sequence of an individual study. Reprinted from Reference 18.

The earliest clinical trials, phase 1 or human pharmacology, are designed to assess short-term drug tolerance and safety, as well as single- and multiple-dose pharmacokinetics. It may be judicious to conduct phase 1 trials in healthy volunteers before introduction of new agents in the CF population. The initial safety, toxicity, and pharmacokinetic profile of the drug or biologic can be better defined in a healthy volunteer population not confounded by the comorbidity of multiorgan disease and a wide range of concomitant medications common to the CF population. If a validated biomarker to measure the physiologic effect of the drug in humans is available, these early phase 1 studies may also be used to define the relationship of drug levels to this response (i.e., pharmacodynamics). For example, early studies of the inhaled antibiotic, tobramycin, in CF looked at dose versus bacterial killing in sputum (19). These phase 1 studies are of short duration (days) and small sample size. It is unlikely that imaging techniques, such as CT, will play a significant role in early pharmacologic studies in CF because the time frame required for a drug to alter airway morphology is much greater than days. A drug or biologic with very rapid onset of pharmacologic effect on airway surface liquid level or air trapping, however, could potentially impact CT findings in this time frame. For example, phase 1 studies of recombinant human DNase (pulmozyme) demonstrated changes in airway obstruction as measured by FEV1 within 1 week (20, 21). Recent studies with hypertonic saline also demonstrated relatively rapid effects on airway surface liquid level and mucociliary clearance (22). Another potential benefit for introducing imaging studies in phase 1 trials would be to collect baseline data and establish standard procedures across sites.

Trials in the next phase of development are referred to as phase 2 or therapeutic exploratory. These studies provide early evidence of therapeutic efficacy for the targeted indication of the drug or biologic product. Frequently, a combination of endpoints (e.g., clinical and pharmacologic) are measured to choose a “winner” (i.e., the optimal clinical outcome[s] to be used in confirmatory phase 3 trials). Drug companies are particularly interested in biomarkers or surrogates that can help them make “go–no-go” decisions for pursuing highly costly phase-3 trials. These endpoints may also yield important information about mechanisms of action (MOA) and pharmacodynamics. By the end of phase 2, the optimal dose regimen should be established. In general, these studies are of longer duration (weeks to months) and larger sample size than in phase 1. Imaging studies, such as CT, may play the greatest role at this therapeutic exploratory phase. The study duration may be sufficient to detect morphologic changes in the airway, and may be useful in defining early efficacy and MOA. For example, if a phase 2 study demonstrates improved FEV1, changes in air trapping or air wall thickening detected by CT may help define relevant structural changes in CF airways that may be contributing to improved air flow. These initial observations would likely need to be coupled with further studies of airway mechanics, such as resistance or compliance measures.

The largest, pivotal trials for the purposes of drug licensing are phase 3 or therapeutic confirmatory studies. The primary purpose of these studies is to demonstrate and confirm (in two separate trials) the clinical efficacy or tangible benefit of the drug or biologic product for the targeted indication. The safety profile of the product must be established to define the risk-to-benefit ratio for licensing purposes. In the CF population, phase 3 trials have had a minimum duration of 6 months and sample sizes of 250–750 subjects (23–25). No pivotal trial in CF used for FDA registration has used an imaging technique as a primary or secondary endpoint. It is unlikely that imaging studies will be used as primary outcomes in this setting, because they have not been validated as direct measures of clinical efficacy and are costly. CT may be an important secondary endpoint, however, to be collected at a subset of sites or selected subpopulations (e.g., children or subjects with normal lung function) to further define mechanism of action, time course of treatment effect, and possible dose response.

Postmarketing, phase 4, or therapeutic usage studies are very important trials in the setting of an orphan disease such as CF. Many companies developing drugs targeting CF indications receive both orphan disease (http://www.fda.gov/orphan/oda.htm) and fast-track (http://www.fda.gov/cber/gdlns/fsttrk.pdf) status in this population. As a result, drug approval is granted with a smaller study population required to define the safety profile, dose–response, and drug–drug interactions than permitted in other larger target populations. The FDA encourages (and may require) postmarketing studies to further define optimal doses regimens, safety, efficacy in special populations (especially infants and young children), and drug–drug interactions. These open-label, phase 4 trials may be months to years in duration and of variable size. Imaging may play a key role as an efficacy and safety measure in infants and young children who cannot perform lung functions or have minimal morphologic changes in CT at baseline (9). In studies lasting several years, long-term morphologic changes may be assessed.

Most CF-related clinical research and drug development for pulmonary indications has been based upon functional outcomes, such as FEV1, rather than structural changes in the lung (23–25). CT scanning and other imaging techniques afford the CF community the opportunity to establish a new research paradigm to stage the illness and define target populations based upon lung morphology rather than the functional status (i.e., FEV1) used in all previous pivotal studies. Using this concept, treatment regimens would be tested to prevent progression, reverse early changes, or stabilize established structural damage. To measure these outcomes, imaging biomarkers could play a key role.

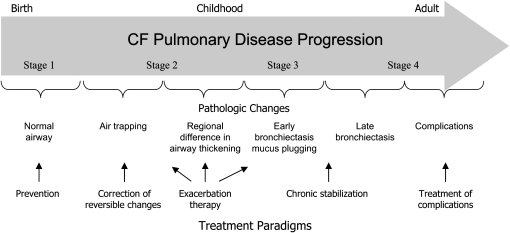

To further develop this concept, the following is a review of a hypothetical schema to stage progression of airway structural damage that occurs in patients with CF at some time between birth and adulthood (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Stages of morphologic damage. This diagram illustrates the usual progression of structural and pathologic changes that occur in the airways of patients with cystic fibrosis (CF) as they age. The time frame is highly variable among individuals with CF, but usually commences during the first decade of life. The stages are arbitrarily chosen to link with possible treatment approaches shown at the bottom of the figure and discussed in more detail in the text.

Pathologic studies in newborns demonstrate normal airway morphology, with the exception of some submucosal gland hypertrophy (26) (stage 1). Imaging studies in infants (9) have shown air trapping and airway thickening as early changes (stage 2), which are likely reversible. These changes are followed by early bronchiectasis and increased mucus plugging and peribronchial thickening (stage 3) (27), and, subsequently, late bronchiectasis and complications, such as bullae and regional atelectasis (stage 4) (28).

Staging disease progression based upon airway structural changes rather than function should encourage CF investigators (and industry partners) to develop new approach for targeting both therapeutic indications and optimal patient populations. This approach may be particularly useful in early lung disease (9, 29). To help illustrate how this staging scheme could be used in a clinical development plan, four potential therapeutic indications, the appropriate target population and clinical outcomes are described in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

POTENTIAL USE OF CHEST COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY AS A CLINICAL OUTCOME MEASURE FOR DIFFERENT TREATMENT STRATEGIES IN CYSTIC FIBROSIS

| Treatment Strategy | Target Population | Potential Therapies | Clinical Outcome Measures (References) | Time Frame |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevention of progression in structural airway disease | Patients with “normal” HRCT (stage 1) | CFTR corrector/potentiator | Chest CT | Months to years |

| Gene therapy | Time to onset of early changes | |||

| Antiinflammatory | Airway diameter (9) | |||

| Other clinical outcomes | ||||

| Growth | ||||

| QOL (31) | ||||

| LCI by multibreath washout (32) | ||||

| Raised volume iPFT (33) | ||||

| Correction of reversible structural changes: air trapping and mucus plugging | Patients with early changes (stage 2) | CFTR corrector/potentiator | Chest CT | Weeks to months |

| Antiinfective | Return of HRCT to stage 1 | |||

| Antiinflammatory | Regional changes | |||

| Mucolytic | Other clinical outcomes | |||

| Growth | ||||

| PFTs | ||||

| QOL (31) | ||||

| LCI (32) | ||||

| iPFT (33) | ||||

| Stabilization of chronic disease | Patients with established bronchiectasis (stage 3) | Antiinflammatory | Chest CT | Weeks to months |

| Mucolytic | Change in CT score(27) | |||

| Antibiotics | Change in CT/PFT composite score (36) | |||

| Other clinical outcomes | ||||

| PFTs | ||||

| PE | ||||

| Treatment of acute exacerbation or complications | Patients during exacerbation | Antibiotics | Chest CT | Weeks |

| Mucolytic | Change in CT score (27) | |||

| CT/PFT composite score (36) | ||||

| Other clinical outcomes | ||||

| PFTs | ||||

| QOL | ||||

| Time to next pulmonary exacerbation |

Definition of abbreviations: CF = cystic fibrosis; CFTR = cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator; CT = computer tomography; HRCT = high-resolution computer tomography; iPFT = infant pulmonary function test; LCI = lung clearance index; PE = pulmonary exacerbation; PFT = pulmonary function test; QOL = quality of life.

In the youngest and healthiest population with near-normal airway and parenchymal morphology (stage 1), the therapeutic goal would be prevention of early airway changes, such as air trapping, mucus plugging, and airway thickening, over a time period of months to years. Therapies targeted to correcting the abnormal CF transmembrane conductance regulator protein should slow disease progression and, therefore, would be ultimately tested in the healthiest patients. Studies have shown very early onset of airway inflammation before infection (30), indicating that early antiinflammatory therapies may also be efficacious in this young, healthy population. For prevention of structural damage, chest CT could be used to measure either airway diameter (9) or time to onset of air trapping and airway wall thickening (stage 2). These changes could be coupled with nonimaging outcomes, such as growth or quality of life measures (31), or other measures of early CF lung disease, such as lung clearance index (32) or infant pulmonary function testing (33).

Patients who demonstrate early changes (stage 2) on chest CT or chest radiograph may be excellent candidates for CF transmembrane conductance regulator correction, antiinflammatories, antiinfectives or mucolytics, and other therapies to improve airway clearance, such as hypertonic saline (34). These patients may be asymptomatic and have normal lung function. Imaging outcomes measured over weeks to months could potentially include a correction of reversible changes toward normality (stage 1) or regional improvements.

For patients with established structural changes (stages 3), the current CT scoring systems (3, 27, 35) have demonstrated reproducibility, and are most useful. In this population, antimicrobial, antiinflammatory, and mucolytic therapies may help stabilize disease progression or improve acute changes resulting from a pulmonary exacerbation. Changes in CT score have already been demonstrated in the setting of a pulmonary exacerbation (15), and could be compared with changes in pulmonary exacerbation and quality of life over several weeks.

This structural staging scheme was developed solely for purposes of discussion at the present conference. To further develop this approach will require consensus among experts in lung imaging techniques and CF clinical investigators in defining the stages of structural damage to the CF airway. In addition, the optimal imaging outcome measures at each stage must also be further defined.

As new CF therapies move toward prevention of disease progression, imaging studies capable of measuring structural changes preceding either respiratory symptoms or functional changes are becoming essential outcome measures. Thus, optimizing the validity of imaging biomarkers must be a priority for the CF research community. Several key steps must be completed to validate and ensure the proper use of imaging techniques, such as CT, as biomarkers. First, standard procedures must be established for conducting imaging studies at clinical sites as well as handling and transfer of the data generated. A centralized reading process should be established to review quality of images and provide scoring. A panel of experts should be convened to establish consensus on the best scoring systems to use in different target populations (e.g., mild versus severe disease, children versus adults), and to compare the role of scoring based upon an expert reviewer (27) versus computer-generated analyses (36).

An important initiative would be the establishment of a centralized clinical data repository for longitudinal collection of chest CT images and chest radiographs linked to the U.S. CF Foundation National Patient Registry. Chest radiographs are currently included in the standard-of-care guidelines. Although chest CT is not included, the usage for clinical management has increased in recent years. Availability of these data could help expand the knowledge base for natural history of structural changes in CF and their relationship to functional changes, growth, and microbiology. These baseline data will allow the CF research community to better assess the reproducibility, precision, and accuracy of repeated CT measurements (and scoring) in this population. This concept is further developed in a subsequent article in this issue of PATS by Dr. Emond, who compares the power of lung function and CT scores using existing databases from published clinical trials.

The final step should be the continued use of imaging studies in early-phase trials to document response to therapeutic interventions. These interventions may be well established therapies (pulmozyme, tobramycin for inhalation [TOBI]) with known MOA or new developing drugs. Over time, as more studies are completed, a profile should emerge for each imaging technique, defining the therapeutic indications and target populations where the technique will be most useful and likely to show change.

In summary, how imaging studies may play a key role in the drug development process in CF has been defined. CF investigators must begin to focus on structural as well as functional measures of disease status. There will continue to be some missing pieces in the puzzle until imaging techniques, such as chest CT, become validated biomarkers in this population; however, significant progress has been made in demonstrating the relationship of changes in CT to clinical outcomes, such as pulmonary exacerbations (15).

Supported by grants to the Cystic Fibrosis Therapeutics Development Network Coordinating Center from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutics, Inc., and the National Center for Research Resources (M01 RR 00037).

Conflict of Interest Statement: B.W.R. does not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.NIH Definitions Working Group. Biomarkers and surrogate endpoints in clinical research: definitions and conceptual model. In: Downing GJ, editor. Biomarkers and surrogate endpoints: clinical research and applications. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2000. pp. 1–9.

- 2.Smith JJ, Sorensen AG, Thrall JH. Biomarkers in imaging: realizing radiology's future. Radiology 2003;227:633–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aziz ZA, Davies JC, Alton EW, Wells AU, Geddes DM, Hansell DM. Computed tomography and cystic fibrosis: promises and problems. Thorax 2007;62:181–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.New drug, antibiotic and biological drug product regulations; accelerated approval: proposed rule. Fed Regist 1992;57:13234–13242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Temple RJ. A regulatory authority's opinion about surrogate endpoints. In: Nimmo WS, Tucker GT, editors. Clinical measurement in drug evaluation. New York: Wiley; 1995. pp. 3–22.

- 6.Liou TG, Adler FR, Fitzsimmons SC, Cahill BC, Hibbs JR, Marshall BC. Predictive 5-year survivorship model of cystic fibrosis. Am J Epidemiol 2001;153:345–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schluchter MD, Konstan MW, Drumm ML, Yankaskas JR, Knowles MR. Classifying severity of cystic fibrosis lung disease using longitudinal pulmonary function data. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;174:780–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang EY, Miller RR, Muller NL. Bronchiectasis: comparison of preoperative thin-section CT and pathologic findings in resected specimens. Radiology 1995;195:649–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Long FR, Williams RS, Castile RG. Structural airway abnormalities in infants and young children with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr 2004;144:154–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Jong PA, Nakano Y, Hop WC, Long FR, Coxson HO, Pare PD, Tiddens HA. Changes in airway dimensions on computed tomography scans of children with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;172:218–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Jong PA, Lindblad A, Rubin L, Hop WC, de Jongste JC, Brink M, Tiddens HA. Progression of lung disease on computed tomography and pulmonary function tests in children and adults with cystic fibrosis. Thorax 2006;61:80–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Jong PA, Nakano Y, Lequin MH, Mayo JR, Woods R, Pare PD, Tiddens HA. Progressive damage on high resolution computed tomography despite stable lung function in cystic fibrosis. Eur Respir J 2004;23:93–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brody AS, Klein JS, Molina PL, Quan J, Bean JA, Wilmott RW. High-resolution computed tomography in young patients with cystic fibrosis: distribution of abnormalities and correlation with pulmonary function tests. J Pediatr 2004;145:32–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Helbich TH, Heinz-Peer G, Fleischmann D, Wojnarowski C, Wunderbaldinger P, Huber S, Eichler I, Herold CJ. Evolution of CT findings in patients with cystic fibrosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1999;173:81–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brody AS, Sucharew H, Campbell JD, Millard SP, Molina PL, Klein JS, Quan J. Computed tomography correlates with pulmonary exacerbations in children with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;172:1128–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robinson TE, Goris ML, Zhu HJ, Chen X, Bhise P, Sheikh F, Moss RB. Dornase alfa reduces air trapping in children with mild cystic fibrosis lung disease: a quantitative analysis. Chest 2005;128:2327–2335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nasr SZ, Kuhns LR, Brown RW, Hurwitz ME, Sanders GM, Strouse PJ. Use of computerized tomography and chest X-rays in evaluating efficacy of aerosolized recombinant human DNase in cystic fibrosis patients younger than age 5 years: a preliminary study. Pediatr Pulmonol 2001;31:377–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Food and Drug Administration. E8 International Conference on Harmonisation. Guidance on general considerations for clinical trials. Fed Regist 1997;62:66113–66119. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith AL, Ramsey BW, Hedges DL, Hack B, Williams-Warren J, Weber A, Gore EJ, Redding GJ. Safety of aerosol tobramycin administration for 3 months to patients with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 1989;7:265–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hubbard RC, McElvaney NG, Birrer P, Shak S, Robinson WW, Jolley C, Wu M, Chernick MS, Crystal RG. A preliminary study of aerosolized recombinant human deoxyribonuclease I in the treatment of cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med 1992;326:812–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aitken ML, Burke W, McDonald G, Shak S, Montgomery AB, Smith A. Recombinant human DNase inhalation in normal subjects and patients with cystic fibrosis: a phase 1 study. JAMA 1992;267:1947–1951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Donaldson SH, Bennett WD, Zeman KL, Knowles MR, Tarran R, Boucher RC. Mucus clearance and lung function in cystic fibrosis with hypertonic saline. N Engl J Med 2006;354:241–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fuchs HJ, Borowitz DS, Christiansen DH, Morris EM, Nash ML, Ramsey BW, Rosenstein BJ, Smith AL, Wohl ME. Effect of aerosolized recombinant human DNase on exacerbations of respiratory symptoms and on pulmonary function in patients with cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med 1994;331:637–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramsey BW, Pepe MS, Quan JM, Otto KL, Montgomery AB, Williams-Warren J, Vasiljev KM, Borowitz D, Bowman CM, Marshall BC, et al. Intermittent administration of inhaled tobramycin in patients with cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med 1999;340:23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saiman L, Marshall BC, Mayer-Hamblett N, Burns JL, Quittner AL, Cibene DA, Coquillette S, Fieberg AY, Accurso FJ, Campbell PW III, et al. Azithromycin in patients with cystic fibrosis chronically infected with Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003;290:1749–1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strugess J, Imrie J. Quantitative evaluation of the development of tracheal submucosal glands in infants with cystic fibrosis and control infants. Am J Pathol 1982;106:303–311. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brody AS, Kosorok MR, Li Z, Broderick LS, Foster JL, Laxova A, Bandla H, Farrell PM. Reproducibility of a scoring system for computed tomography scanning in cystic fibrosis. J Thorac Imaging 2006;21:14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Jong PA, Ottink MD, Robben SG, Lequin MH, Hop WC, Hendriks JJ, Pare PD, Tiddens HA. Pulmonary disease assessment in cystic fibrosis: comparison of CT scoring systems and value of bronchial and arterial dimension measurements. Radiology 2004;231:434–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brody AS, Tiddens HA, Castile RG, Coxson HO, de Jong PA, Goldin J, Huda W, Long FR, McNitt-Gray M, Rock M, et al. Computed tomography in the evaluation of cystic fibrosis lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;172:1246–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khan TZ, Wagener JS, Bost T, Martinez J, Accurso FJ, Riches DW. Early pulmonary inflammation in infants with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995;151:1075–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quittner AL, Buu A, Messer MA, Modi AC, Watrous M. Development and validation of the cystic fibrosis questionnaire in the United States: a health-related quality-of-life measure for cystic fibrosis. Chest 2005;128:2347–2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aurora P, Bush A, Gustafsson P, Oliver C, Wallis C, Price J, Stroobant J, Carr S, Stocks J, London Cystic Fibrosis C. Multiple-breath washout as a marker of lung disease in preschool children with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:249–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.American Thoracic Society. ATS/ERS Statement: raised volume forced expirations in infants: guidelines for current practice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;172:1463–1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elkins MR, Robinson M, Rose BR, Harbour C, Moriarty CP, Marks GB, Belousova EG, Xuan W, Bye PT. National Hypertonic Saline in Cystic Fibrosis Study G: a controlled trial of long-term inhaled hypertonic saline in patients with cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2006;354:229–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Jong PA, Ottink MD, Robben SG, Lequin MH, Hop WC, Hendriks JJ, Pare PD, Tiddens HA. Pulmonary disease assessment in cystic fibrosis: comparison of CT scoring systems and value of bronchial and arterial dimension measurements. Radiology 2004;231:434–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robinson TE, Leung AN, Northway WH, Blankenberg FG, Chan FP, Bloch DA, Holmes TH, Moss RB. Composite spirometric-computed tomography outcome measure in early cystic fibrosis lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;168:588–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]