Abstract

Ambient ozone (O3) is a commonly encountered environmental air pollutant with considerable impact on public health. Many other inhaled environmental toxicants can substantially affect pulmonary immune responses. Therefore, it is of considerable interest to better understand the complex interaction between environmental airway irritants and immunologically based human disease. The innate immune system represents the first line of defense against microbial pathogens. Intact innate immunity requires maintenance of an intact barrier to interface with the external environment, effective phagocytosis of microbial pathogens, and precise detection of pathogen-associated molecular patterns. We use ambient O3 as a model to highlight the importance of understanding the role of exposure to ubiquitous air toxins and regulation of basic immune function. Inhalation of O3 is associated with impaired antibacterial host defense, in part related to disruption of epithelial barrier and effective phagocytosis of pathogens. The functional response to ambient O3 seems to be dependent on many components of the innate immune signaling. In this article, we review the complex interaction between inhalation of O3 and pulmonary innate immunity.

Keywords: Toll-like receptor, tlr4, environmental airways injury, macrophage, epithelia

IMPACT OF AMBIENT OZONE ON PUBLIC HEALTH

Ozone (O3) is a commonly encountered urban air pollutant that significantly contributes to increased morbidity in human populations (1–4). Ambient O3 was highlighted as an important ambient air pollutant in human health in the Clean Air Act of 1970 by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). In 1997, the EPA reduced the O3 standard from 120 to 80 ppb based on evidence that supported detrimental health effects. Since that time, multiple epidemiologic studies have supported the health-related benefits of adherence to established regulatory standards. Environmental exposure to ambient O3 has a significant impact on human health, which can lead to a significant economic burden. It has been estimated that each year strict adherence to the established 8-hour O3 standard would result in reductions in the 800 premature deaths, 4,500 hospital admissions, 900,000 school absences, and more than 1 million restricted activity days with an estimated $5 billion annual economic burden (5). Children (6, 7) and adults older than 65 years of age (8) are particularly vulnerable to low levels of inhaled O3. However, population-based studies support a global impact on minimal increases in ambient levels of O3. One study found a 4% increase in mortality for each 25-ppb measured increase in the level of ambient O3 (9). Recent estimates suggest that, for each 10-ppb increase in 1-hour daily maximum of O3, there is an increase in mortality between 0.39 and 0.87% (2, 3, 10, 11). The association with increased mortality persists even at levels of ambient O3 of 15 ppb, which is well below the current EPA standard (12). Increased levels of O3 can lead to increased severity of respiratory illness, but it remains unclear whether this is secondary to primary alterations in airway mechanics or dysregulation of immune function (13). O3 can modify immune function (14). We speculate that altered morbidity and mortality associated with ambient O3 is, in part, dependent on a complex interaction with the innate immune system. In this article, we provide background and updated evidence that supports the relationship between exposure to ambient O3 and innate immune function.

O3 AND PULMONARY IMMUNITY

Many previous studies suggest that preexposure to O3 can reduce host antibacterial defense. Altered host vulnerability to live pathogens after O3 exposure is supported by multiple previous rodent studies that demonstrate impaired clearance of live microbial organisms, including Streptococcus zooepidemicus (15), Streptococcus pyogenes (16), Staphylococcus aureus (17), Klebsiella pneumonia (18), Mycobacterium tuberculosis (19), and Listeria monocytogenes (20). The mechanisms that alter host vulnerability to each of these bacterial pathogens remain poorly understood. O3 susceptibility seems, in part, dependent on genetic background in humans (21, 22) and mice (23–26). Current literature supports a complex interaction between O3 and host response (27, 28).

The immune system is broadly divided into two categories: the innate immune system and the adaptive immune system. The adaptive immune system relies on an antigen-specific response and activation of T and B lymphocytes. Previous studies of ambient O3 have primarily focused on the effects on adaptive immune function. O3 exposure has been associated with reduced lymphoid organ weights (29, 30) and suppressed T-lymphocyte–dependent immunologic response (31, 32). The overall effects on allergic asthma are variable and seem to depend on the timing, dose, and duration of exposure in rodents (33–36) and humans (37, 38). In contrast to the adaptive immune response, the innate immune response is a highly evolutionarily, conserved, first-line defense against microbial pathogens. The innate immunity broadly consists of structural barriers, microbial phagocytosis, and specific microbial pattern recognition. Since the sentinel discovery that Drosophila Toll receptors play a fundamental role in host detection of microbial pattern recognition (39), Toll-like receptors (TLRs) in mammalian species have been recognized to play a fundamental role in the detection of invasive pathogens and in many other inflammatory diseases. Disruption of any component of the innate immune response could have a profound impact on immune function and host antibacterial defense. We review the evidence suggesting that exposure to ambient O3 modifies epithelial barrier integrity and microbial phagocytosis. In addition, we review a growing body of evidence to suggest that pattern recognition receptors and their downstream signaling play a fundamental role in the biologic and physiologic response to O3.

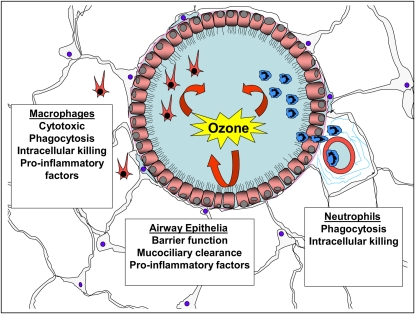

The lung is constantly exposed to a broad spectrum of environmental toxins, including microbiological pathogens, bacterial products, and ambient O3. Epidemiologic evidence and animal studies suggest that these inhaled environmental toxins can affect the severity of airways disease. A common feature of the host response to each of these inhaled toxins is neutrophilic inflammation, up-regulation of proinflammatory cytokines, and decrements in lung function (40–46). Although these responses help facilitate the clearance of pathogens, they can lead to tissue injury and compromised lung function. Accordingly, it is important to understand the molecular mechanisms that initiate and regulate neutrophilic inflammation and consequent tissue damage. Many cell types in the lung are involved in pulmonary innate immune response, including macrophages (47, 48), neutrophils (49), endothelia (50), and airway epithelia (51). Evidence suggests that the biologic function of many of these cell types can be modified by exposure to ambient O3 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Ozone (O3) modifies antibacterial defense in many cell types in the lung. O3 can disrupt epithelial tight junctions and mucociliary clearance and can induce production of proinflammatory factors. O3 is directly cytotoxic to macrophages. O3 can modify macrophage phagocytosis, intracellular killing, and levels of secreted factors. O3 can impair neutrophil phagocytosis and intracellular killing.

O3 DISRUPTS EPITHELIAL INTEGRITY

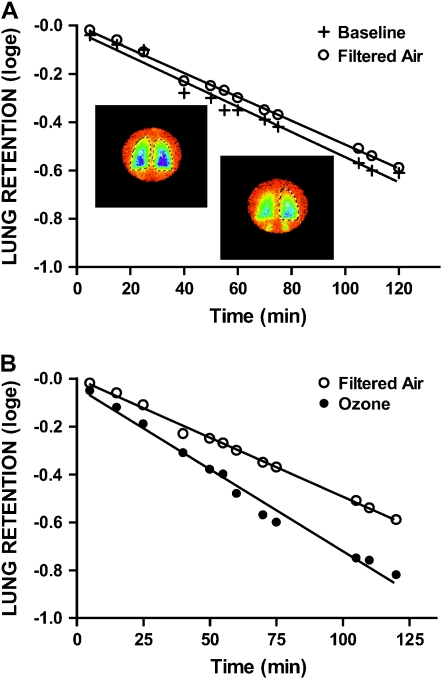

A primary innate immune defense mechanism is through maintenance of intact epithelial barrier. This is achieved by intact airway epithelia and effective mucociliary clearance. The presence of cellular and biochemical markers of inflammation in lung lavage fluids suggested that the integrity of respiratory epithelia is impaired by O3 (52, 53). Acute exposure to O3 causes damage to airway epithelial cells and alveoli. Human studies suggest that exercise in combination with exposure to moderate levels of O3 can increase airway epithelial permeability (43). Furthermore, exposure to ambient levels of O3 can impair selective permeability of the epithelium (46). The loss of epithelial integrity after O3 parallels the inflammatory changes in the lower respiratory tract (52), but they are not necessarily codependent. Inhalation of hydrophilic low-molecular-weight 99mTc-DTPA (MW 492, radius 0.57 nm) allows investigation of transepithelial transit via paracellular channels, which are primarily limited by structural pores. O3-induced hyperpermeability through paracellular pathways is of considerable clinical interest because impaired epithelial barrier function can facilitate access of xenobiotic molecules to basolateral surfaces of submucosal tissues and then subsequently the systemic circulation. O3-induced defects in airway epithelial barrier function could contribute to the increased severity of pulmonary infections observed after high levels of ambient O3 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Ozone disrupts epithelial barrier function to protein. Lung clearance of soluble radiolabeled albumin in a subject evaluated after exposure to filtered air (A) or ozone (B) when compared with baseline. Lung retention is expressed as natural log of activity level in right lung at time zero with retention points fitted to a linear regression. Data points represent lung retention of soluble marker at the indicated times. Lung retention is expressed as natural log of the fractional retention of the activity level of the radiomarker deposited at time zero. Superimposed color images represent scintigraphy scans of the lung acquired from the posterior aspect and demonstrate dynamics of the clearance process with color intensity equivalent to radiolabel activity levels: blue > green > yellow. As activity clears the lung from epithelial airway and alveolar surfaces by transport via paracellular pathways into the systemic and pulmonary vasculatures, bilateral accumulation is visualized below the diaphragms, representing cleared activity filtered by the kidneys. (Adapted by permission from Reference 46.)

Mucociliary clearance provides another first-line defense against pulmonary infections. This important aspect of epithelial barrier defense facilitates effective clearance of foreign material from the airways. Mucociliary clearance is dependent on the interplay among several factors, including mucin secretion, mediator release, epithelial permeability, and ciliary beat frequency. Acute exposure to O3 in humans demonstrated that the smaller peripheral bronchioles were more sensitive than lobar bronchi to ambient levels of O3 (54). Subsequent studies replicated these observations and suggest that the response to O3 is transient (55). Oxidant gases can also react with cross-linking bonds of mucus glycoprotein structures, resulting in lower viscosity of respiratory secretions and impaired mucociliary clearance (56). The effects of O3 on secretory cells in culture have not been well characterized; however, in vivo animal models have shown that O3 exposure can increase levels of tracheal glycoconjugates (57). Of interest is the rodent model of mucus cell hyperplasia developed by Fannuchi and Harkema in which mRNA levels of rMuc5ac (the major component of respiratory mucins) become elevated in transitional epithelium after exposure to ambient O3 levels followed by nasal instillation of endotoxin (58). In addition, loss of cilia in the terminal bronchioles is considered an early indicator of acute oxidant-induced injury (59). These data suggest that O3 can modify many components required for effective mucociliary clearance of foreign material or microbial pathogens.

In addition to defects in epithelial barrier and defects in mucociliary clearance, airway epithelial cells are functionally altered after exposure to O3. In vitro studies of airway epithelia cultured in liquid–air interface demonstrate that O3 exposure can induce the secretion of many proinflammatory factors (60). More recent murine studies demonstrate that exposures to O3 can attenuate the transcription of IL-1 mRNA in response to secondary endotoxin challenge (61). The later observation suggests that primary damage to airway epithelia, as a result of O3 exposure, can impair the subsequent response to TLR ligands.

IMPAIRED MACROPHAGE FUNCTION AFTER EXPOSURE TO O3

Macrophages play a critical role in orchestrating pulmonary innate immune response to inhaled endotoxin (47, 48). Substantial evidence suggests that inhalation of O3 can directly modify alveolar macrophage function. In vitro studies of O3 effects on human alveolar macrophages demonstrate impaired phagocytosis, superoxide production, and increased levels of secreted cytokines (62). Human alveolar macrophages seem to be more sensitive to the cytotoxic effects of ambient O3 when compared with cultured airway epithelia (60). Murine studies demonstrate that O3-induced impaired antibacterial defense to S. aureus and S. zooepidemicus was associated with impaired phagocytic capacity of alveolar macrophages (63, 64). Although O3 can impair macrophage phagocytosis and superoxide production in the lung, in vitro studies of peripheral human blood monocytes demonstrate that O3 can also directly stimulate the production of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and IFN-γ (65). Furthermore, preexposure to O3 can enhance pulmonary macrophage production of nitric oxide with subsequent in vitro treatment by endotoxin or IFN-γ (66). These findings demonstrate that O3 can directly impair antibacterial clearance through reduced phagocytosis and superoxide production. Furthermore, in vitro studies of coexposure suggest that O3 can prime some aspects of subsequent pulmonary innate immune response.

NEUTROPHILS AND ENVIRONMENTAL AIRWAY INJURY WITH O3

Similar to inhaled endotoxin, acute response to inhalation of O3 results in airway injury and neutrophil influx into the airspace. It remains unclear whether recruited neutrophils directly contribute to the biologic response to inhaled O3. Previous reports suggest that accumulation of neutrophils in the airways is critical to the physiologic response to O3 (67–69), whereas other similarly conducted studies have not substantiated this observation (70–72). It is possible that differences in O3 exposure protocols or techniques of neutrophil depletion used in these experiments contribute to the divergent observations. Regardless, recruited neutrophils maintain the capacity to generate proinflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen species, which can contribute to acute lung injury (73). Enhanced recruitment of neutrophils into the airspace conceptually would prove beneficial in rapid clearance of secondary exposure to bacterial pathogens. However, this was not observed with models of live pathogen challenge after preexposure to O3 and could be related to impaired function of recruited neutrophils. Early work by Peterson and colleagues demonstrates that human exposure to low levels of ambient O3 lead to defective neutrophil phagocytosis and intracellular killing (74). More recent in vitro studies indicate that O3 impaired the capacity of human neutrophils to produce superoxide radicals (75). These observations suggest that exposure to ambient levels of O3 can impair the functional ability of neutrophils to respond to bacterial pathogens and provide further evidence that O3 can modify the innate immune response.

SECRETED FACTORS AND BIOLOGIC RESPONSE TO O3

It has been well documented in animal models and human studies that exposure to O3 induces secretion of inflammatory factors into the lung. Analysis of alveolar lavage fluid reveals biochemical evidence of O3-induced inflammation with increases in many secreted factors, including fibronectin, elastase, plasminogen activator, tissue factor, factor VIII, C3a fragment of complement, prostaglandins, IL-1, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, and granulocyte-macrophage colony–stimulating factor (44, 60, 76). Many of these secreted factors are recognized downstream products of activation of the innate immune system. The critical role of downstream secreted factors in the biologic response to O3 was initially identified through a genome-wide linkage analysis study. In that study, a quantitative trait locus on chromosome 17 was identified, and fine mapping identified TNF-α as a candidate gene (23). The fundamental role of TNF-α in neutrophil recruitment and epithelial cell proliferation in response to O3 was confirmed with TNF-α–neutralizing antibodies. Subsequent studies have identified that TNF-α contributes to O3-induced airway hyperresponsiveness in mice (77, 78) and humans (79). Additional studies have identified that many of the up-regulated downstream proinflammatory factors play a role in the biologic response to inhaled O3, including neutrophil elastase (80), complement (70), IL-1 (81), and IL-6 (82). Additionally, the neutrophil chemokines, KC and macrophage inflammatory protein-2, are expressed in the lungs of mice after exposure to O3 (83). Studies demonstrate that the receptor for these chemokines (CXCR2) is essential for complete response to O3 (84). These data suggest that downstream activation of proinflammatory factors play an important role in response to ambient O3. The initial stimulus leading to activation of these proinflammatory factors remains poorly described.

SURFACE RECEPTORS AND RESPONSE TO O3

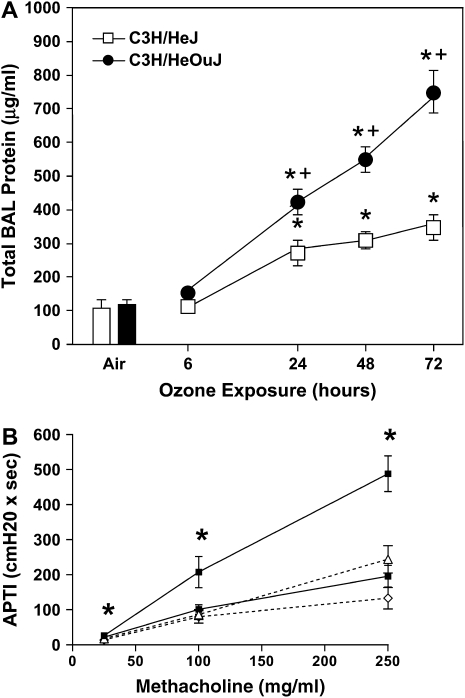

The innate immune system consists of epithelial barriers, phagosomes, and the recognition of pattern-associated molecular patterns. The discovery of surface receptors that immediately recognize foreign material has dramatically enhanced our understanding of host immunity. Mammalian TLRs play a critical role in detecting invading pathogens and triggering subsequent inflammatory and immune responses. The surface receptors bind pattern-associated molecular patterns and interact with intracellular adaptor molecules, resulting in activation of nuclear transcription regulators. This cascade results in the production of many proinflammatory factors associated with the immediate inflammatory response. The discovery that the LPS receptor tlr4 plays a role in airway injury in response to O3 was made through fine mapping of a quantitative trait locus and characterization of the C3H/HeJ mouse (24, 85) (Figure 3A). Subsequently, O3-induced airway hyperresponsiveness was identified to be dependent on intact tlr4 (86) (Figure 3B). Recent unpublished data presented at the 2006 American Thoracic Society International Conference suggest that O3-induced airway hyperresponsiveness is dependent on the downstream adaptor protein MyD88 (87). Furthermore, previous work suggests that the biologic response to O3 is, in part, dependent on the transcription regulator, nuclear factor (NF)-κβ p50 (88). Based on these observations, it is plausible that tlr4-dependent signaling can lead to MyD88-dependent activation of NF-κβ and transcription of downstream proinflammatory factors, leading to O3-induced airway hyperresponsiveness. Ozonolysis products (eicosanoid release and generation of peroxyl radicals) of epithelial membrane fatty acids can function as early transducers of O3 reactions at the epithelial surface (89). Lipid ozonation products (hydrogen peroxide and aldehydes) have been suggested to act as signal transduction molecules in the lung and in extrapulmonary tissues (90, 91). Recent evidence suggests that ozonation of low-density lipoprotein can inhibit NF-κβ and IL-1 receptor–associated kinase-1–associated signaling (92). These observations suggest that O3 could modify lipid products and modify subsequent systemic innate immune response. For this reason, host genetic factors related to oxidative stress/redox balance are of considerable interest, including glutathione S-transferase M1, glutathione S-transferase P1, nicotinamide adenosine dinucleotide (phosphate) reduced:quinine oxidoreductase, glutathione peroxidase-1, glutathione reductase, and superoxide dismutase-2. The mechanisms that link the biologic response to O3 and innate immunity remain poorly understood.

Figure 3.

Functional response to ozone is dependent on Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4). Mice were exposed to 300 ppb ozone (O3) for 72 hours. (A) Airway injury was determined by level of protein in the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid in the C3H/OuJ (tlr4-sufficient) and the C3H/HeJ (tlr4-deficient) over time. Statistical comparison: air versus O3 treatment groups (*p < 0.05); C3H/HeJ versus C3H/HeOuJ (†p < 0.05). (B) After completion of exposure to O3, physiologic response to intravenous methacholine in wild-type and tlr4 knockout mice were evaluated by direct measurements of tracheal pressures. Increased airway pressure–time index (APTI) values in O3 exposed C57BL/6 animals when compared with tlr4−/− were seen at all doses of intravenous methacholine, including 25 μg/ml (*p < 0.01), 100 μg/ml (*p = 0.02), 250 μg/ml (*p = 0.001). (B) TLR4+/+ O3, upper solid line, solid squares; TLR4−/− O3, dotted line, open triangles; TLR4+/+ air, lower solid line, solid squares; TLR4−/− air, dotted line, open diamonds. (Adapted by permission from References 24 and 86.)

To further elucidate the mechanism through which tlr4 modulates responsiveness to O3, Dahl and colleagues (93) used microarrays to determine gene expression profiles in the lungs of C3H/HeJ (Tlr4 mutant, O3–resistant) and C3H/HeOuJ (Tlr4 normal, O3–susceptible) mice after exposure to 0.3-ppm O3. Marco (macrophage receptor with collagenous structure) was highly up-regulated by O3 in the lungs of C3H/HeJ mice, whereas no changes were found in C3H/HeOuJ mice. Targeted disruption of Marco significantly enhanced O3-induced lung inflammation compared with wild-type mice, and inflammation induced by the instillation of β-epoxide and PON-GPC (surfactant-derived ozonation products) was significantly greater in Marco-deficient mice compared with wild-type mice. These results suggest an important role for scavenger receptors in decreasing inflammation after O3 by scavenging proinflammatory oxidized lipids (93). Additionally, recent human data suggest that O3 exposure can enhance surface expression of the tlr4 coreceptor CD14 on airway macrophages and monocytes (94). The role of TLR4 in the biologic response to O3 in humans has not been adequately examined. These data strongly suggest that the biologic response to O3 is dependent on a complex interaction with innate immune signaling.

CONCLUSIONS

The functional innate immune system consists of an intact epithelial barrier, effective phagocytosis of pathogens, and precise activation of innate immune signaling pathways. Exposure to ambient O3 can disrupt epithelial integrity and impair mucociliary clearance. O3 impairs effective phagocytosis of microbial pathogens in macrophages and neutrophils. The functional response to O3 is dependent on TLRs, likely the adaptor molecule MyD88, and many downstream proinflammatory secreted factors. Understanding the fundamental mechanisms that regulate the biologic response to commonly encountered inhaled environmental toxins will provide a better understanding of the increased morbidity and mortality associated with high levels of ambient air pollution. Furthermore, with improved understanding of the complex interaction between inhaled toxicants and innate immunity, we will be able to provide more effective therapeutic intervention for patients with environmental airways disease.

Supported by National Institute of Environmental Health Services grants ES12717, ES11961, and ES012496; by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant AI058161; and by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

Conflict of Interest Statement: None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Dockery DW, Pope CA, Xu X, Spengler JD, Ware JH, Fay ME, Ferris BG, Speizer FE. An association between air pollution and mortality in six U.S. cities. N Engl J Med 1993;329:1754–1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bell M, McDermott A, Zeger S, Samet J, Dominici F. Ozone and short-term mortality in 95 US urban communities, 1987–2000. JAMA 2004;292:2372–2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gryparis A, Forsberg B, Katsouyanni K, Analitis A, Touloumi G, Schwartz J, Samoli E, Medina S, Anderson HR, Niciu EM, et al. Acute effects of ozone on mortality from the “Air Pollution and Health: A European Approach” project. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004;28:28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katsouyanni K, Zmirou D, Spix C, Sunyer J, Schouten JP, Ponka A, Anderson HR, Le Moullec Y, Wojtyniak B, Vigotti MA, et al. Short-term effects of air pollution on health: a European approach using epidemiological time-series data. The APHEA project: background, objectives, design. Eur Respir J 1995;8:1030–1038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hubbell BJ, Hallberg A, McCubbin DR, Post E. Health-related benefits of attaining the 8-hr ozone standard. Environ Health Perspect 2005;113:73–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gent JF, Triche EW, Holford TR, Belanger K, Bracken MB, Beckett WS, Leaderer BP. Association of low-level ozone and fine particles with respiratory symptoms in children with asthma. JAMA 2003;290:1859–1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burnett RT, Smith-Doiron M, Stieb D, Raizenne ME, Brook JR, Dales RE, Leech JA, Cakmak S, Krewski D. Association between ozone and hospitalization for acute respiratory diseases in children less than 2 years of age. Am J Epidemiol 2001;153:444–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwartz J. Short term fluctuations in air pollution and hospital admissions of the elderly for respiratory disease. Thorax 1995;50:531–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parodi S, Vercelli M, Garrone E, Fontana V, Izzotti A. Ozone air pollution and daily mortality in Genoa, Italy between 1993 and 1996. Public Health 2005;119:844–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ito K, De Leon SF, Lippmann M. Associations between ozone and daily mortality: analysis and meta-analysis. Epidemiology 2005;16:446–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levy JI, Chemerynski SM, Sarnat JA. Ozone exposure and mortality: an empiric bayes metaregression analysis. Epidemiology 2005;16:458–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bell ML, Peng RD, Dominici F. The exposure-response curve for ozone and risk of mortality and the adequacy of current ozone regulations. Environ Health Perspect 2006;114:532–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Medina-Ramon M, Zanobetti A, Schwartz J. The effect of ozone and PM10 on hospital admissions for pneumonia and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a national multicity study. Am J Epidemiol 2006;163:579–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jakab GJ, Spannhake EW, Canning BJ, Kleeberger SR, Gilmour MI. The effects of ozone on immune function. Environ Health Perspect 1995;103:77–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilmour M, Park P, Doerfler D, Selgrade M. Factors that influence the suppression of pulmonary antibacterial defenses in mice exposed to ozone. Exp Lung Res 1993;19:299–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aranyi C, Vana S, Thomas P, Bradof J, Fenters J, Graham J, Miller F. Effects of subchronic exposure to a mixture of O3, SO2, and (NH4)2SO4 on host defenses of mice. J Toxicol Environ Health 1983;12:55–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldstein E, Tyler W, Hoeprich P, Eagle C. Ozone and the antibacterial defense mechanisms of the murine lung. Arch Intern Med 1971;127:1099–1102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller S, Ehrlich R. Susceptibility to respiratory infections of animals exposed to ozone. I: susceptibility to Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Infect Dis 1958;103:145–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas G, Fenters J, Ehrlich R, Gardner D. Effects of exposure to ozone on susceptibility to experimental tuberculosis. Toxicol Lett 1981;9:11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loveren HV, Rombout P, Wagenaar S, Walvoort H, Vos J. Effects of ozone on the defense to a respiratory Listeria monocytogenes infection in the rat: suppression of macrophage function and cellular immunity and aggravation of histopathology in lung and liver during infection. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 1988;94:374–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Balmes JR, Chen LL, Scannell C, Tager I, Christian D, Hearne PQ, Kelly T, Aris RM. Ozone-induced decrements in FEV1 and FVC do not correlate with measures of inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996;153:904–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weinmann GG, Bowes SM, Gerbase MW, Kimball AW, Frank R. Response to acute ozone exposure in healthy men: results of a screening procedure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995;151:33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kleeberger SR, Levitt RC, Zhang LY, Longphre M, Harkema J, Jedlicka A, Eleff SM, DiSilvestre D, Holroyd KJ. Linkage analysis of susceptibility to ozone-induced lung inflammation in inbred mice. Nat Genet 1997;17:475–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kleeberger SR, Reddy S, Zhang LY, Jedlicka AE. Genetic susceptibility to ozone-induced lung hyperpermeability: role of toll-like receptor 4. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2000;22:620–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prows DR, Shertzer HG, Daly MJ, Sidman CL, Leikauf GD. Genetic analysis of ozone-induced acute lung injury in sensitive and resistant strains of mice. Nat Genet 1997;17:471–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Savov JD, Whitehead GS, Wang J, Liao G, Usuka J, Peltz G, Foster WM, Schwartz DA. Ozone-induced acute pulmonary injury in inbred mouse strains. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2004;31:69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mudway IS, Kelly FJ. Ozone and the lung: a sensitive issue. Mol Aspects Med 2000;21:1–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhalla DK. Ozone-induced lung inflammation and mucosal barrier disruption: toxicology, mechanisms, and implications. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev 1999;2:31–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fujimaki H, Ozawa M, Imai T, Shimizu F. Effect of short-term exposure to O3 on antibody response in mice. Environ Res 1984;35:490–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dziedzic D, White HJ. Thymus and pulmonary lymph node response to acute and subchronic ozone inhalation in the mouse. Environ Res 1986;41:598–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fujimaki H, Shiraishi F, Ashikawa T, Murakami M. Changes in delayed hypersensitivity reaction in mice exposed to O3. Environ Res 1987;43:186–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Loveren H, Rombout PJ, Wagenaar SS, Walvoort HC, Vos JG. Effects of ozone on the defense to a respiratory Listeria monocytogenes infection in the rat: suppression of macrophage function and cellular immunity and aggravation of histopathology in lung and liver during infection. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 1988;94:374–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Last JA, Ward R, Temple L, Kenyon NJ. Ovalbumin-induced airway inflammation and fibrosis in mice also exposed to ozone. Inhal Toxicol 2004;16:33–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Depuydt PO, Lambrecht BN, Joos GF, Pauwels RA. Effect of ozone exposure on allergic sensitization and airway inflammation induced by dendritic cells. Clin Exp Allergy 2002;32:391–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wagner JG, Hotchkiss JA, Harkema JR. Enhancement of nasal inflammatory and epithelial responses after ozone and allergen coexposure in Brown Norway rats. Toxicol Sci 2002;67:284–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ozawa M, Fujimaki H, Imai T, Honda Y, Watanabe N. Suppression of IgE antibody production after exposure to ozone in mice. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol 1985;76:16–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jorres R, Nowak D, Magnussen H. The effect of ozone exposure on allergen responsiveness in subjects with asthma or rhinitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996;153:56–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kehrl, Peden D, Ball B, Folinsbee L, Horstman D. Increased specific airway reactivity of persons with mild allergic asthma after 7.6 hours of exposure to 0.16 ppm ozone. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1999;104:1198–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lemaitre B, Nicolas E, Michaut L, Reichhart JM, Hoffmann JA. The dorsoventral regulatory gene cassette spatzle/Toll/cactus controls the potent antifungal response in Drosophila adults. Cell 1996;86:973–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jagielo PJ, Thorne PS, Watt JL, Frees KL, Quinn TJ, Schwartz DA. Grain dust and endotoxin inhalation challenges produce similar inflammatory responses in normal subjects. Chest 1996;110:263–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O'Grady NP, Preas HL, Pugin J, Fiuza C, Tropea M, Reda D, Banks SM, Suffredini AF. Local inflammatory responses following bronchial endotoxin instillation in humans. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;163:1591–1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kline J, Cowden J, Hunninghake G, Schutte B, Watt J, Wohlford-Lenane C, Powers L, Jones M, Schwartz D. Variable airway responsiveness to inhaled lipopolysaccharide. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;160:297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kehrl HR, Vincent LM, Kowalsky RJ, Horstman DH, O'Neil JJ, McCartney WH, Bromberg PA. Ozone exposure increases respiratory epithelial permeability in humans. Am Rev Respir Dis 1987;135:1124–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koren HS, Devlin RB, Graham DE, Mann R, McGee MP, Horstman DH, Kozumbo WJ, Becker S, House DE, McDonnell WF, et al. Ozone-induced inflammation in the lower airways of human subjects. Am Rev Respir Dis 1989;139:407–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Foster WM, Brown RH, Macri K, Mitchell CS. Bronchial reactivity of healthy subjects: 18–20 h postexposure to ozone. J Appl Physiol 2000;89:1804–1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Foster WM, Stetkiewicz PT. Regional clearance of solute from the respiratory epithelia: 18–20 h postexposure to ozone. J Appl Physiol 1996;81:1143–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hollingsworth JW, Chen BJ, Brass DM, Berman K, Gunn MD, Cook DN, Schwartz DA. The critical role of hematopoietic cells in lipopolysaccharide-induced airway inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:806–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koay MA, Gao X, Washington MK, Parman KS, Sadikot RT, Blackwell TS, Christman JW. Macrophages are necessary for maximal nuclear factor-kappa B activation in response to endotoxin. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2002;26:572–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Savov JD, Gavett SH, Brass DM, Costa DL, Schwartz DA. Neutrophils play a critical role in development of LPS-induced airway disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2002;283:L952–L962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Andonegui G, Bonder CS, Green F, Mullaly SC, Zbytnuik L, Raharjo E, Kubes P. Endothelium-derived Toll-like receptor-4 is the key molecule in LPS-induced neutrophil sequestration into lungs. J Clin Invest 2003;111:1011–1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Skerrett SJ, Liggitt HD, Hajjar AM, Ernst RK, Miller SI, Wilson CB. Respiratory epithelial cells regulate lung inflammation in response to inhaled endotoxin. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2004;287:L143–L152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Devlin RB, McDonnell WF, Mann R, Becker S, House DE, Schreinemachers D, Koren HS. Exposure of humans to ambient levels of ozone for 6.6 hours causes cellular and biochemical changes in the lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1991;4:72–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seltzer J, Bigby BG, Stulbarg M, Holtzman MJ, Nadel JA, Ueki IF, Leikauf GD, Goetzl EJ, Boushey HA. O3-induced change in bronchial reactivity to methacholine and airway inflammation in humans. J Appl Physiol 1986;60:1321–1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Foster WM, Costa DL, Langenback EG. Ozone exposure alters tracheobronchial mucociliary function in humans. J Appl Physiol 1987;63:996–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gerrity TR, Bennett WD, Kehrl H, DeWitt PJ. Mucociliary clearance of inhaled particles measured at 2 h after ozone exposure in humans. J Appl Physiol 1993;74:2984–2989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Last JA. Mucus production and the ciliary escalator. In: Witschi H, Nettersheim P, series editors. Mechanisms in respiratory toxicology. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1982. p. 247.

- 57.Last JA, Jennings MD, Schwartz LW, Cross CE. Glycoprotein secretion by tracheal explants cultured from rats exposed to ozone. Am Rev Respir Dis 1977;116:695–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fanucchi MV, Hotchkiss JA, Harkema JR. Endotoxin potentiates ozone-induced mucous cell metaplasia in rat nasal epithelium. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 1998;152:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stephens RJ, Evans MJ, Sloan MF, Freeman G. A comprehensive ultrastructural study of pulmonary injury and repair in the rat resulting from exposures to less than one PPM ozone. Chest 1974;65:11S–13S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Devlin RB, McKinnon KP, Noah T, Becker S, Koren HS. Ozone-induced release of cytokines and fibronectin by alveolar macrophages and airway epithelial cells. Am J Physiol 1994;266:L612–L619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Johnston CJ, Holm BA, Finkelstein JN. Sequential exposures to ozone and lipopolysaccharide in postnatal lung enhance or inhibit cytokine responses. Exp Lung Res 2005;31:431–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Becker S, Madden MC, Newman SL, Devlin RB, Koren HS. Modulation of human alveolar macrophage properties by ozone exposure in vitro. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 1991;110:403–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gilmour M, Hmieleski R, Stafford E, Jakab G. Suppression and recovery of the alveolar macrophage phagocytic system during continuous exposure to 0.5 ppm ozone. Exp Lung Res 1991;17:547–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gilmour MI, Park P, Selgrade MK. Ozone-enhanced pulmonary infection with Streptococcus zooepidemicus in mice: the role of alveolar macrophage function and capsular virulence factors. Am Rev Respir Dis 1993;147:753–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Larini A, Bocci V. Effects of ozone on isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Toxicol In Vitro 2005;19:55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pendino KJ, Laskin JD, Shuler RL, Punjabi CJ, Laskin DL. Enhanced production of nitric oxide by rat alveolar macrophages after inhalation of a pulmonary irritant is associated with increased expression of nitric oxide synthase. J Immunol 1993;151:7196–7205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Holtzman MJ, Fabbri LM, O'Byrne PM, Gold BD, Aizawa H, Walters EH, Alpert SE, Nadel JA. Importance of airway inflammation for hyperresponsiveness induced by ozone. Am Rev Respir Dis 1983;127:686–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.O'Byrne PM, Walters EH, Gold BD, Aizawa HA, Fabbri LM, Alpert SE, Nadel JA, Holtzman MJ. Neutrophil depletion inhibits airway hyperresponsiveness induced by ozone exposure. Am Rev Respir Dis 1984;130:214–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.DeLorme MP, Yang H, Elbon-Copp C, Gao X, Barraclough-Mitchell H, Bassett DJ. Hyperresponsive airways correlate with lung tissue inflammatory cell changes in ozone-exposed rats. J Toxicol Environ Health A 2002;65:1453–1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Park JW, Taube C, Joetham A, Takeda K, Kodama T, Dakhama A, McConville G, Allen CB, Sfyroera G, Shultz LD, et al. Complement activation is critical to airway hyperresponsiveness after acute ozone exposure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004;169:726–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li Z, Daniel EE, Lane CG, Arnaout MA, O'Byrne PM. Effect of an anti-Mo1 MAb on ozone-induced airway inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness in dogs. Am J Physiol 1992;263:L723–L726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pino MV, Stovall MY, Levin JR, Devlin RB, Koren HS, Hyde DM. Acute ozone-induced lung injury in neutrophil-depleted rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 1992;114:268–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Abraham E. Neutrophils and acute lung injury. Crit Care Med 2003;31:S195–S199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Peterson ML, Harder S, Rummo N, House D. Effect of ozone on leukocyte function in exposed human subjects. Environ Res 1978;15:485–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Margalit M, Attias E, Attias D, Elstein D, Zimran A, Matzner Y. Effect of ozone on neutrophil function in vitro. Clin Lab Haematol 2001;23:243–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Aris RM, Christian D, Hearne PQ, Kerr K, Finkbeiner WE, Balmes JR. Ozone-induced airway inflammation in human subjects as determined by airway lavage and biopsy. Am Rev Respir Dis 1993;148:1363–1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cho HY, Zhang LY, Kleeberger SR. Ozone-induced lung inflammation and hyperreactivity are mediated via tumor necrosis factor-alpha receptors. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2001;280:L537–L546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shore SA, Schwartzman IN, Le Blanc B, Murthy GG, Doerschuk CM. Tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 contributes to ozone-induced airway hyperresponsiveness in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;164:602–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yang IA, Holz O, Jorres RA, Magnussen H, Barton SJ, Rodriguez S, Cakebread JA, Holloway JW, Holgate ST. Association of tumor necrosis factor-alpha polymorphisms and ozone-induced change in lung function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:171–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Matsumoto K, Aizawa H, Inoue H, Koto H, Nakano H, Hara N. Role of neutrophil elastase in ozone-induced airway responses in guinea-pigs. Eur Respir J 1999;14:1088–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Park JW, Taube C, Swasey C, Kodama T, Joetham A, Balhorn A, Takeda K, Miyahara N, Allen CB, Dakhama A, et al. IL-1 receptor antagonist attenuates airway hyperresponsiveness following exposure to ozone. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2004;30:830–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Johnston RA, Schwartzman IM, Flynt L, Shore SA. Role of interleukin-6 in murine airway responses to ozone. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2005;288:L390–L397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Driscoll KE, Simpson L, Carter J, Hassenbein D, Leikauf GD. Ozone inhalation stimulates expression of a neutrophil chemotactic protein, macrophage inflammatory protein 2. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 1993; 119:306–309. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 84.Johnston RA, Mizgerd JP, Shore SA. CXCR2 is essential for maximal neutrophil recruitment and methacholine responsiveness after ozone exposure. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2005;288:L61–L67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kleeberger SR, Reddy SP, Zhang LY, Cho HY, Jedlicka AE. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates ozone-induced murine lung hyperpermeability via inducible nitric oxide synthase. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2001;280:L326–L333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hollingsworth JW, Cook DN, Brass DM, Walker JK, Morgan DL, Foster WM, Schwartz DA. The role of toll-like receptor 4 in environmental airway injury in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004;170:126–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Williams AS, Adcock IM, Mitchell JA, Chung KF. Airways hyperresponsiveness and inflammation in tlr2−/−, tlr4−/−, and Myd88−/− mice exposed to ozone [abstract]. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2006;3:A549. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fakhrzadeh L, Laskin JD, Laskin DL. Ozone-induced production of nitric oxide and TNF-alpha and tissue injury are dependent on NF-kappaB p50. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2004;287:L279–L285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Leikauf GD, Zhao Q, Zhou S, Santrock J. Activation of eicosanoid metabolism in human airway epithelial cells by ozonolysis products of membrane fatty acids. Res Rep Health Eff Inst 1995;71:1–15 (discussion: 19–26). [PubMed]

- 90.Pryor WA, Das B, Church DF. The ozonation of unsaturated fatty acids: aldehydes and hydrogen peroxide as products and possible mediators of ozone toxicity. Chem Res Toxicol 1991;4:341–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pryor WA, Squadrito GL, Friedman M. The cascade mechanism to explain ozone toxicity: the role of lipid ozonation products. Free Radic Biol Med 1995;19:935–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cappello C, Saugel B, Huth KC, Zwergal A, Krautkramer M, Furman C, Rouis M, Wieser B, Schneider HW, Neumeier D, et al. Ozonized low density lipoprotein (ozLDL) inhibits NF-kappaB and IRAK-1-associated signaling. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2007;27:226–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dahl M, Bauer A, Arredouani M, Soininen R, Tryggvason K, Kleeberger S, Kobzik L. Protection against inhaled oxidants through scavenging of oxidized lipids by macrophage receptors MARCO and SR-AI/II. J Clin Invest 2007;117:757–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Alexis NE, Becker S, Bromberg PA, Devlin R, Peden DB. Circulating CD11b expression correlates with the neutrophil response and airway mCD14 expression is enhanced following ozone exposure in humans. Clin Immunol 2004;111:126–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]