Abstract

Centrilobular emphysema caused by chronic cigarette smoking is a heterogeneous disease with a predominance of upper lobe involvement. It is presumed that this heterogeneity indicates a particular susceptibility to cigarette smoke or the fact that the inhaled smoke distributes preferentially to upper lung zones. The less involved areas might therefore retain the capacity for lung regeneration and gain of pulmonary function in terminally ill patients. We propose that the interplay between molecular and cellular switches involved in the lung response to environmental injuries determines the heterogeneous pattern of emphysema due to cigarette smoke. Regional activation of alveolar destruction by apoptosis and oxidative stress coupled with regional failure of defense mechanisms may account for the irregular pattern of lung destruction in cigarette smoke–induced emphysema. Protection afforded by the key antioxidant transcription factor Nrf-2 and the antiproteolytic and antiapoptotic actions of α1-antitrypsin is central to maintain lung homeostasis and lung structure. As the lung is injured by environmental pollutants, including cigarette smoke, molecular sensors of cellular stress, such as the mTOR/protein translation regulator RTP-801, may engage both inflammation and alveolar cell apoptosis. As injury prevails during the course of this chronic disease, it leads to a more homogeneous pattern of lung disease.

Keywords: aging, apoptosis, emphysema, inflammation, oxidative stress

Centrilobular emphysema consists of a heterogeneous pattern of alveolar enlargement, evident at gross, microscopic, cellular, and molecular levels. Macroscopically, the disease predominates in the upper lung areas as compared with the relatively spared lower lung zones. Microscopically, the destruction caused by cigarette smoke targets the centrilobular region—that is, the functional unit made up of a respiratory bronchiole, alveolar duct, and adjacent alveolar structures. In α1-antitrypsin (A1AT)–deficient patients, emphysema occurs in a more global pattern, affecting all lobes, and involving microscopically most of the primary lobule—that is, both the centrilobular and the peripheral components of the alveolar units connected to the respiratory bronchiole.

Lung homeostasis relies on cell and molecular maintenance programs involving alveolar structural cells, blood vessels, inflammatory cells, and extracellular matrix (1). As the lung faces constant challenges from the environment, such as pathogens or toxins, molecular master switches afford protection against cellular damage resulting from oxidative stress, pathologic lung cell apoptosis (both initiation of apoptosis and apoptotic cell clearance), and excessive extracellular matrix proteolysis. The integrated action of these protective mechanisms efficiently counteracts environmental challenges and maintains the lung's ability to repair. Preferential distribution of the inhaled smoke provides a logical explanation for the upper lung zone predominance of cigarette smoke–induced emphysema. However, the disease is often patchy, sparing wide regions while irreversibly damaging alveolar structures, with eventual progression to global lung destruction. This article frames the issue of heterogeneity of lung destruction in emphysema as the result of the interplay of injury caused by cigarette smoke and protective mechanisms involved in lung homeostasis. This conceptual framework considers the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) beyond that of a linear interaction among cigarette smoke (or environmental pollutants), inflammation, and excessive lung proteolysis.

As detailed below, we provide evidence of the following: (1) a lung maintenance program based on vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling, the antioxidant master transcription factor nuclear factor 2 erythroid–related factor-2 (Nrf-2), and a novel antiapoptotic function for A1AT; and (2) a cellular stress response system that, if inappropriately activated, may overcome the lung maintenance program and cause alveolar wall destruction. We describe two components of a harmful exaggerated response to stress: the RTP-801, which may engage both an inflammatory and an apoptotic response, and ceramide, which may trigger both alveolar cell apoptosis and oxidative stress in response to VEGF receptor blockade or cigarette smoke inhalation.

Some of the studies presented herein have been previously reported in the form of abstracts (2, 3).

LUNG HETEROGENEITY DURING HOMEOSTASIS AND EMPHYSEMA

The alveolar septum appears as a relatively simple anatomic structure, designed to maximize gas exchange by interposing a minimal tissue interface between air and the capillary bed. Conceptually, this architectural design optimizes gas exchange surface area while minimizing potential shunting (due to imbalances of capillary and air surface matching). The physical and physiologic interaction between air and blood conduits starts soon after lung formation and persists throughout lung development and the mature lung (4, 5). Four different cells come together to organize the alveolar septum (i.e., type I and II epithelial cells, endothelial cells, and the myofibroblasts). The physical interconnectivity of these cells was revealed by the work of Sirianni and colleagues, who demonstrated that myofibroblasts physically link endothelial and epithelial cells, creating virtual synapses potentially allowing for the creation of a functional multicellular syncytium (6). Indeed, alveolar septal cells can respond in a synchronized manner to signaling initiated on either the airspace or the capillary side (7, 8). Although our understanding of the molecular interdependence among alveolar septal cells remains rudimentary, we know that epithelial and endothelial cells respond to similar trophic and growth factors, such as VEGF via VEGF receptor 2 (VEGF-R2) (9, 10). This interdependence is further illustrated by the finding that type II cells and macrophages produce VEGF (10), which then acts on type II cells themselves (11) and on endothelial cells. The integrated protection allowed by septal cells, the extracellular matrix, and resident inflammatory cells underlies a lung maintenance program (12).

Biological systems evolved based on their ability to fend off injury promoted by the environment or infectious agents, thus increasing the chances of successful procreation of the species. A current line of thought in evolutionary biology proposes that aging results from the stochastic interaction among organismal injuries caused by the environment, and that the biological price of protecting against these injuries is the “wear and tear” related to aging (also known as the disposable soma hypothesis [13]). Multiple attacks against organismal maintenance by environmental agents promote organ and cell dysfunction, leading to age-related diseases, many of them with secondary inflammation caused by the cellular damage. We have recently related this evolutionary concept to age-related alteration in lung structure and function, and how cigarette smoke–induced emphysema might share pathogenetic mechanisms related to aging (14). The recent report of enhanced cigarette smoke–induced emphysema in mice lacking senescence-associated marker 30 (SMP-30), an antiaging calcium binding protein, supports that aging and cigarette smoke might interact and synergistically enhance alveolar destruction (15, 16).

LUNG MAINTENANCE: ROLE OF VEGF

The requirement for proper extracellular matrix renewal for maintenance of alveolar structural integrity may extend beyond lung development, and be required throughout the lifetime of the organ. The concept of homeostatic alveolar maintenance was initially documented by a study showing the requirement of proper extracellular matrix maintenance, which found inhibition of extracellular matrix deposition led to experimental emphysema (1). Furthermore, abnormalities of elastin fiber deposition lead to developmental lung arrest and an overall simplification of alveolar structure with airspace enlargement (17).

The contributions of growth/trophic factors to organ maintenance may be the basis of structural and functional lung heterogeneity and homeostatic lung function. We have previously demonstrated that VEGF fulfils this premise, because VEGF-R blockade (12), genetic deletion of VEGF (18), or generation of antiendothelial cell antibodies (including antibodies against VEGF-R2) (19) cause airspace enlargement. Cigarette smoke causes significant decreases in VEGF and VEGF-R expression in rodent models of emphysema (20, 21), a finding validated by numerous studies in human emphysematous lungs (22). As VEGF signaling is interrupted, the ensuing alveolar enlargement is apoptosis dependent in rats (12), a finding that highlights the role of alveolar cell apoptosis in experimental and human emphysema (22, 23) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of positive interaction among apoptosis, protease/antiprotease imbalance, and oxidative stress in emphysema.

Because oxidative stress is a critical process in COPD (24), we hypothesized that experimental emphysema caused by VEGF-R blockade involved a mutual positive feedback interaction between apoptosis and oxidative stress (25) (Figures 2 and 3). These findings led us to propose that alveolar destruction in emphysema involved feedback interactive loops among apoptosis, oxidative stress, and excessive lung extracellular matrix proteolysis (26) (Figure 1), thus expanding the long-held belief that lung destruction in emphysema occurs solely due to excessive alveolar matrix proteolysis (27). We noted that alveolar structures near alveolar ducts were more often involved by oxidative stress and apoptosis as compared with alveoli located more peripherally in the primary lobule. This finding suggested that alveolar structures do not have a homogeneous reliance on VEGF. The “interactive loop of alveolar destruction” has been further expanded with the recent demonstration that emphysema caused by cigarette smoke or lung IFN-γ overexpression requires cathepsin-S–dependent alveolar cell apoptosis (28), and that alveolar cell apoptosis is associated with enhanced susceptibility to emphysema in mice deficient of Nrf-2 (thus unable to up-regulate antioxidant defenses) (29).

Figure 2.

Evidence of a positive feedback loop between apoptosis and oxidative stress in lungs with emphysematous enlargement after vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor blockade. A and B show the coexpression of a macromolecular of oxidative stress, 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-HG; red signal) and apoptosis (black nuclear signal). In A, there is intense 8-HG expression in centrilobular areas (CL; arrows) with colocalization with active caspase-3. In B, the perilobular areas (PL) show less evidence of oxidative stress (arrows) and apoptosis (arrowheads). C shows the correlation between 8-HG intensity and caspase-3–positive cells. The graph illustrates the interactive loops between oxidative stress and apoptosis. Blockade of oxidative stress with an superoxide dismutase (SOD) mimetic led to significant decrease of oxidative stress, apoptosis, and alveolar enlargement (reproduced by permission from Reference 25).

Figure 3.

(A–C) Coexpression of markers of apoptosis and lung oxidative stress in experimental emphysema. The increased 8-HG expression in lungs with VEGF receptor blockade (A) is normalized in lungs cotreated with a broad-spectrum caspase inhibitor (B; normal lungs in C) (12, 25). The intensity of lung expression in the three groups is plotted in D. The graph illustrates that caspase inhibition leads to decrease in apoptosis, oxidative stress, and alveolar enlargement (reproduced by permission from Reference 25).

A central question remaining to be addressed is which alveolar septal cell drives the alveolar enlargement in emphysema. Type II cell injury is commonly followed by repair. However, in experimental emphysema caused by lung overexpression of IFN-γ or interleukin-13, apoptosis of type II cells predominates over other alveolar septal cells (28). Our data suggest that alveolar capillary endothelial cells, due to their limited regeneration, might play a direct role toward irreversible alveolar destruction (14). Endothelial cell apoptosis predominates over other cells in cigarette smoke–induced emphysema in the Nrf-2 null mice (29). Myofibroblasts may play central roles in controlling alveolar repair and elastin synthesis, because deletion of platelet-derived growth factor receptor α causes fetal alveolar enlargement, associated with failure to form alveolar myofibroblasts (30).

FAILURE OF LUNG PROTECTION AGAINST OXIDATIVE STRESS IN CIGARETTE SMOKE–INDUCED EMPHYSEMA: ROLE FOR Nrf-2

According to the disposable soma hypothesis of aging, protection afforded by nutrients or antioxidants counterbalances the injury imposed by environmental agents (13). This hypothesis of oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction remains one of the most attractive hypotheses of aging (31). Nrf-2 was initially found in screening of genes involved in erythrocyte development (32) and then discovered to bind to antioxidant response elements (33) of several phase 2 antioxidant genes, leading ultimately to direct or indirect up-regulation of more than 100 gene products. The first link between Nrf-2 and oxidative stress–related lung diseases was determined by linkage analysis in mouse strains susceptible to hyperoxic injury (34). The studies by Rangasamy and coworkers of wild-type and Nrf-2–deficient mice exposed to cigarette smoke provided evidence of a clear link between defects in the lung antioxidant defense regulated by Nrf-2 and excessive oxidative stress, increased apoptosis, inflammation, and exacerbated emphysema (29). Nrf-2–deficient mice exposed to cigarette smoke for 6 mo develop emphysema associated with more pronounced bronchoalveolar inflammation, enhanced alveolar expression of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2′-deoxyguanosine, a marker of oxidative stress, and with an increased number of apoptotic alveolar septal cells, predominantly endothelial and type II epithelial cells, when compared with wild-type littermates. As described earlier, microarray analysis has identified the expression of nearly 50 Nrf-2–dependent antioxidant and cytoprotective genes in the lungs that may work in concert to counteract cigarette smoke–induced oxidative stress and inflammation (29). The responsiveness of the Nrf-2–dependent genes may be a major determinant of resistance to tobacco smoke–induced emphysema, because of their ability to up-regulate antioxidant defenses and decrease lung inflammation and alveolar cell apoptosis. Increased emphysema in Nrf-2–deficient mice after direct administration of elastase to lungs also supports a role of Nrf-2 in maintaining the balance between proteases and antiproteinases (2). Additional protective actions of Nrf-2 were documented in interstitial damage by instilled bleomycin (35) and asthma (36). More recently, a critical novel function of Nrf-2 in modulating inflammatory responses to bacterial endotoxin was uncovered (37). During sepsis, Nrf-2 modulated tumor necrosis factor, chemokine, and nuclear factor (NF)-κB levels, which were highly expressed in mice null for Nrf-2. The Nrf-2 paradigm linking susceptibility to bacterial infection and emphysema is in line with our recent proposition that cigarette smoke does not induce a specific inflammatory response but rather triggers inflammation secondary to organ damage, potentially involving mediators of the innate immunity (14). The hypothesis that the age-dependent decline of Nrf-2 transcriptional activity might represent a critical determinant of the age dependency of emphysema and the emphysematous lung pattern in aged individuals needs to be tested.

A1AT DEFICIENCY AND PANLOBULAR EMPHYSEMA: MORE THAN JUST LOSS OF ANTIELASTASE ACTIVITY

Although emphysema due to cigarette smoke has a centrilobular pattern of alveolar destruction, A1AT deficiency is associated with a panlobular injury pattern. Clinically and physiologically, both groups of patients behave similarly and share cigarette smoke as a common critical etiologic factor. The nature of the widespread alveolar destruction in A1AT-deficient patients remains unclear. With the increasing understanding that emphysematous lung destruction involves excessive proteolysis, apoptosis, and oxidative stress, the association of A1AT deficiency with panlobular destruction may be explained if all three elements of this pathologic triad synergistically and simultaneously operate in the lung destruction in A1AT-deficient patients (Figure 4). Indeed, levels of A1AT inversely correlate with susceptibility to experimental emphysema caused by cigarette smoke and oxidant stress (38). Furthermore, polymers of A1AT in patients harboring the ZZ variant of A1AT stimulate inflammation and thus oxidative stress (39).

Figure 4.

Pathogenesis of α1-antitrypsin (A1AT) deficiency. A1AT deficiency (ZZ variant) may lead to a more global alveolar destruction since it causes (1) oxidative stress via its proinflammatory properties when polymerized, (2) loss of the antiprotease shield, and (3) loss of anti–active caspase-3 activity (3, 43).

In light of the finding that A1AT was able to prevent HIV proliferation and cell death in human lymphocytes (40), and the evidence that linked A1AT to protection against apoptotic liver injury (41) and against ischemic kidney injury (42), we investigated whether A1AT might have also an antiapoptotic function in addition to its antielastase properties. Indeed, we have recently documented that A1AT protects against experimental emphysema caused by VEGF-R blockade (43) or intratracheal instillation of active caspase-3 (44). The protection afforded by A1AT expression may be directly linked to the apoptotic machinery, because A1AT binds and inactivates active caspase-3 (44). Interestingly, A1AT's reactive loop, which is involved in the irreversible inhibition of trypsin and elastase, appears to also mediate the anti–caspase-3 activity of A1AT. These data revealed a novel role for A1AT, and suggested potentially novel intracellular actions of this extracellular protease inhibitor.

In addition to this antiapoptotic action, A1AT has been also implicated in regulating inflammation, because human A1AT supplementation suppresses NF-κB in mice treated with intratracheal silica instillation (45). A novel function in immune regulation was recently uncovered that might explain the protection of recombinant human A1AT against islet cell injury in the nonobese diabetic (NOD) mouse model. Human A1AT transduction using viral vectors leads to markedly reduced insulitis, protection against overt diabetes, and significant alteration of the T-cell receptor repertoire when compared with control NOD mice (46).

Of note, our experimental approach relied on in vivo supplementation with human A1AT transduced in skeletal muscle, with accumulation of the protein in alveolar septal cells in vivo and in microvascular endothelial cells in vitro. These findings lead to questions of whether extracellular A1AT (1) binds to cell receptors or (2) becomes internalized to reduce caspase-3 or NF-κB activation, and whether (3) intracellularly synthesized A1AT might exert similar functions in liver and nonliver cells (i.e., alveolar and bronchial cells), whereas ZZ variants might have lost their antiinflammatory and antiapoptotic functions.

The identification of an antiapoptotic role for A1AT provides further evidence for the mutual interaction between apoptosis and matrix proteolysis in the triad involved in alveolar destruction (26). Consistent with this interaction are the findings that caspase-3 instillation into rodent lungs triggers enhances elastolytic activity of apoptotic epithelial cells retrieved from bronchoalveolar lavage from affected mice (47) and active caspase-3 can degrade elastin fragments in vitro (48).

AMPLIFICATION OF ALVEOLAR DESTRUCTION: ROLE OF ENDOGENOUS MEDIATORS OF ALVEOLAR DESTRUCTION

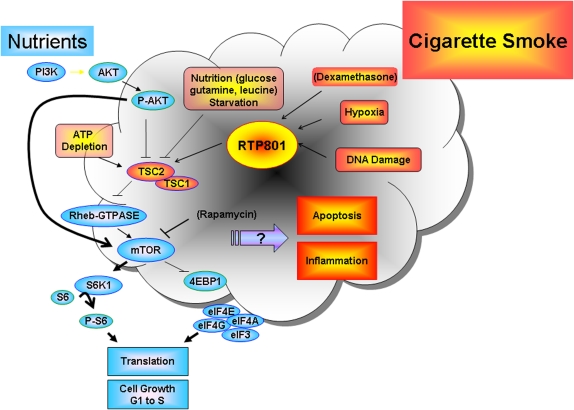

As discussed previously, the environment imposes continuous biological selection, with consequences related to aging, as macromolecular damage accumulates and progressively overwhelms organ defenses. Organisms developed molecular sensors to respond acutely to environmental stresses, such as those imposed by hypoxia or nutrient deprivation. RTP-801 (or REDD1 for REgulated in Development and DNA Damage responses), a repressor of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), was initially discovered as a hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α–inducible protein, whose expression is modulated by oxidative stress and capable of inducing apoptosis when overexpressed in lungs of mice (49, 50) (Figure 5). RTP-801 is also activated during glucose deprivation and inhibits growth signals originated by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI 3-kinase)/protein kinase B (Akt)/mTOR pathway via the activation of the tubersclerosis complex (TSC) protein hamartin or TSC-1 and tuberin or TSC-2 (51). We have recently observed that mice exposed to cigarette smoke show acute lung up-regulation of RTP-801. Interestingly, TSC-2 down-regulates VEGF both dependently and independently of its inhibitory effects on mTOR (52). The inhibition of mTOR decreases S6 kinase phosphorylation, causing its inactivation, and stabilizes 4eBP1 (an inhibitor of the ribosomal machinery), both leading to decreased protein translation. RTP-801–deficient mice exposed to acute cigarette smoke exposure have attenuated alveolar inflammation and alveolar cell apoptosis, when compared with wild-type mice. RTP-801–null mice have preservation of alveolar diameters when subjected to chronic inhalation of cigarette smoke, as compared with wild-type mice (53). These findings suggest that the cellular stress triggered by cigarette smoke activates molecular sensors that modulate inflammation, alveolar apoptosis, and potentially oxidative stress (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

RTP-801 and growth or inhibitory cell signaling in cells exposed to nutrients or environmental stresses, respectively. RTP-801 activates tubersclerosis complex hamartin and tuberin proteins (TSC1 and TSC2, respectively), which via inhibition of Rheb kinase lead to mTOR inhibition and suppression of protein translation. mTOR is usually activated under conditions favoring cell growth during abundance of nutrients or due to insulin signaling. The activation of RTP-801 is targeted for cell protection during stress; however, given the nature of the environmental stress, overexpression of RTP801 may cause apoptosis, oxidative stress, or excessive inflammation. AKT = protein kinase B; P-AKT = phosphorylated AKT; PI3K = phosphotidylinositol 3-kinase; RHEB-GTP = RHEB-GTPase.

The activation of endogenous molecular stress responses might explain why COPD follows a relentless course, even when smokers quit. We have recently reported that VEGF-R inhibition activates ceramide, which accounts for apoptosis and oxidative stress seen in this model of rodent emphysema (54). Amplification loops are generated, with subsequent activation of enzymes involved in the recycling of cell membrane sphingolipids into ceramide (via acid sphingomyelinase activation). Ceramide might act in a paracrine manner to further increase lung ceramide levels. This action is localized upstream in the apoptosis process, because ceramide increases were observed in mice treated with caspase inhibitors (53). The central elements of this paradigm have been recently extended to mice exposed to cigarette smoke inhalation (I. Petrache and colleagues, unpublished observations).

CONCLUSIONS

Lung heterogeneity in emphysema might reflect residual elements of homeostasis in the injured lung. Lung injury and emphysema caused by cigarette smoke contain pathogenetic elements beyond those predicated by the inflammation protease–antiprotease imbalance. We have learned that peripheral blood cells of patients with COPD have decreased telomerase activity (54), and lung cells exhibit markers of senescence when exposed to cigarette smoke (55), which supports the hypothesis that the lung injury caused by cigarette smoke shares some of the pathobiology common to aging. The injured regions develop in a setting of failure of alveolar structural and cellular maintenance, with decreased levels of survival factors such as VEGF and alterations of extracellular matrix. Activation of the destructive processes of apoptosis, matrix proteolysis, and oxidative stress, and their mediators such as ceramide or RTP-801, might represent potential targets for therapies. Furthermore, the collapse of protective molecular processes, such as the antioxidant system (via Nrf-2) or A1AT, may be critical in extending the destructive process to more preserved lung regions. Indeed, A1AT deficiency might compromise antielastolytic, antiapoptotic, and antiinflammatory defenses, which, in combination, contribute to a more homogeneous pattern of emphysema, compared with the one present in the aged lung. It follows that therapeutic approaches have to be aimed at increasing the overall protection of the lung against subsequent injury, thus allowing for re-engagement of alveolar repair. A potential candidate is sphingosine-1 phosphate, a downstream metabolite of the ceramide pathway, which opposes the destructive effects of ceramide, and affords lung protection against apoptosis and oxidative stress caused by VEGF-R blockade (54). The therapeutic interference with processes involved in organ damage and targeted up-regulation of protective mechanisms might be critical for the success of future cell-based therapies.

Supported by the Alpha 1 Foundation Research Fund, NIH RO1HL66554, and a Quark Biotech research grant (to R.M.T.); NIH RO1HL081205, P50 CA058184, and the Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute (to S.B.); NIH K08 HL04396-04, an ATS/Alpha One Foundation research grant, and an American Lung Association research grant (to I.P.).

Conflict of Interest Statement: None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Tuder RM, McGrath S, Neptune E. The pathobiological mechanisms of emphysema models: what do they have in common? Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2003;16:67–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoshida T, Rangasamy T, Biswal S, Petrache I, Mett I, Feinstein E, Tuder RM. Role of RTP801, a suppressor of the mTOR pathway, in cigarette smoke-induced pulmonary injury in mice. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2006;3:551–552. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petrache I, Fijalkowska I, Zhen L, Medler TR, Skirball J, Tuder RM. α1-Antitrypsin treatment inhibits alveolar cell apoptosis and lung destruction in a model of noninflammatory emphysema. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2006;3:A174. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Healy AM, Morgenthau L, Zhu XH, Farber HW, Cardoso WV. VEGF is deposited in the subepithelial matrix at the leading edge of branching airways and stimulates neovascularization in the murine embryonic lung. Dev Dyn 2000;219:341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gebb SA, Shannon JM. Tissue interactions mediate early events in pulmonary vasculogenesis. Dev Dyn 2000;217:159–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sirianni FE, Chu FSF, Walker DC. Human alveolar wall fibroblasts directly link epithelial type 2 cells to capillary endothelium. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;168:1532–1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuebler WM, Parthasarathi K, Wang PM, Bhattacharya J. A novel signaling mechanism between gas and blood compartments of the lung. J Clin Invest 2000;105:905–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ichimura H, Parthasarathi K, Quadri S, Issekutz AC, Bhattacharya J. Mechano-oxidative coupling by mitochondria induces proinflammatory responses in lung venular capillaries. J Clin Invest 2003;111:691–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tuder RM, Flook BE, Voelkel NF. Increased gene expression for VEGF and the VEGF receptors KDR/Flk and Flt in lungs exposed to acute or to chronic hypoxia: Modulation of gene expression by nitric oxide. J Clin Invest 1995;95:1798–1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Acarregui MJ, Penisten ST, Gross KL, Ramirez K, Snyder JM. Vascular endothelial growth factor gene expression in human fetal lung in vivo. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1999;20:14–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Compernolle V, Brusselmans K, Acker T, Hoet P, Tjwa M, Beck H, Plaisance S, Dor Y, Keshet E, Lupu F, et al. Loss of HIF-2alpha and inhibition of VEGF impair fetal lung maturation, whereas treatment with VEGF prevents fatal respiratory distress in premature mice. Nat Med 2002;8:702–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kasahara Y, Tuder RM, Taraseviciene-Stewart L, Le Cras TD, Abman SH, Hirth P, Waltenberger J, Voelkel NF. Inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors causes lung cell apoptosis and emphysema. J Clin Invest 2000;106:1311–1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirkwood TBL. Understanding the odd science of aging. Cell 2005; 120:437–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tuder RM, Yoshida T, Arap W, Pasqualini R, Petrache I. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of alveolar destruction in emphysema: an evolutionary perspective. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2006;3:506–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sato T, Seyama K, Sato Y, Mori H, Souma S, Akiyoshi T, Kodama Y, Mori T, Goto S, Takahashi K, et al. Senescence marker protein-30 protects mice lungs from oxidative stress, aging, and smoking. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;174:530–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tuder RM. Aging and cigarette smoke: fueling the fire. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;174:490–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wendel DP, Taylor DG, Albertine KH, Keating MT, Li DY. Impaired distal airway development in mice lacking elastin. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2000;23:320–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang K, Rossiter HB, Wagner PD, Breen EC. Lung-targeted VEGF inactivation leads to an emphysema phenotype in mice. J Appl Physiol 2004;97:1559–1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taraseviciene-Stewart L, Scerbavicius R, Choe KH, Moore M, Sullivan A, Nicolls MR, Fontenot AP, Tuder RM, Voelkel NF. An animal model of autoimmune emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:734–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bartalesi B, Cavarra E, Fineschi S, Lucattelli M, Lunghi B, Martorana PA, Lungarella G. Different lung responses to cigarette smoke in two strains of mice sensitive to oxidants. Eur Respir J 2005;25:15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marwick JA, Stevenson CS, Giddings J, MacNee W, Butler K, Rahman I, Kirkham PA. Cigarette smoke disrupts VEGF165-VEGFR-2 receptor signaling complex in rat lungs and patients with COPD: morphological impact of VEGFR-2 inhibition. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2006;290:L897–L908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kasahara Y, Tuder RM, Cool CD, Lynch DA, Flores SC, Voelkel NF. Endothelial cell death and decreased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 in emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;163:737–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Segura-Valdez L, Pardo A, Gaxiola M, Uhal BD, Becerril C, Selman M. Upregulation of gelatinases A and B, collagenases 1 and 2, and increased parenchymal cell death in COPD. Chest 2000;117:684–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacNee W, Rahman I. Is oxidative stress central to the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Trends Mol Med 2001;7:55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tuder RM, Zhen L, Cho CY, Taraseviciene-Stewart L, Kasahara Y, Salvemini D, Voelkel NF, Flores SC. Oxidative stress and apoptosis interact and cause emphysema due to vascular endothelial growth factor receptor blockade. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2003;29:88–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tuder RM, Petrache I, Elias JA, Voelkel NF, Henson PM. Apoptosis and emphysema: the missing link. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2003;28: 551–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shapiro SD. The pathogenesis of emphysema: the elastase:antielastase hypothesis 30 years later. Proc Assoc Am Physicians 1995;107:346–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zheng T, Kang MJ, Crothers K, Zhu Z, Liu W, Lee CG, Rabach LA, Chapman HA, Homer RJ, Aldous D, et al. Role of cathepsin S-dependent epithelial cell apoptosis in IFN-γ-induced alveolar remodeling and pulmonary emphysema. J Immunol 2005;174:8106–8115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rangasamy T, Cho CY, Thimmulappa RK, Zhen L, Srisuma SS, Kensler TW, Yamamoto M, Petrache I, Tuder RM, Biswal S. Genetic ablation of Nrf2 enhances susceptibility to cigarette smoke-induced emphysema in mice. J Clin Invest 2004;114:1248–1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bostrom H, Willetts K, Pekny M, Leveen P, Lindahl P, Hedstrand H, Pekna M, Hellstrom M, Gebre-Medhin S, Schalling M, et al. PDGF-A signaling is a critical event in lung alveolar myofibroblast development and alveogenesis. Cell 1996;85:863–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Balaban RS, Nemoto S, Finkel T. Mitochondria, oxidants, and aging. Cell 2005;120:483–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chan JY, Han X, Kan YW. Cloning of Nrf1, an NF-E2-related transcription factor, by genetic selection in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1993;90:11371–11375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Itoh K, Chiba T, Takahashi S, Ishii T, Igarashi K, Katoh Y, Oyake T, Hayashi N, Satoh K, Hatayama I, et al. An Nrf2/small Maf heterodimer mediates the induction of phase II detoxifying enzyme genes through antioxidant response elements. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1997; 236:313–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cho HY, Jedlicka AE, Reddy SPM, Kensler TW, Yamamoto M, Zhang LY, Kleeberger SR. Role of NRF2 in protection against hyperoxic lung injury in mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2002;26:175–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cho HY, Reddy SP, Kleeberger SR. Nrf2 defends the lung from oxidative stress. Antioxid Redox Signal 2006;8:76–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rangasamy T, Guo J, Mitzner WA, Roman J, Singh A, Fryer AD, Yamamoto M, Kensler TW, Tuder RM, Georas SN, et al. Disruption of Nrf2 enhances susceptibility to severe airway inflammation and asthma in mice. J Exp Med 2005;202:47–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thimmulappa RK, Lee H, Rangasamy T, Reddy SP, Yamamoto M, Kensler TW, Biswal S. Nrf2 is a critical regulator of the innate immune response and survival during experimental sepsis. J Clin Invest 2006; 116:984–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cavarra E, Bartalesi B, Lucattelli M, Fineschi S, Lunghi B, Gambelli F, Ortiz LA, Martorana PA, Lungarella G. Effects of cigarette smoke in mice with different levels of α(1)-proteinase inhibitor and sensitivity to oxidants. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;164:886–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mahadeva R, Atkinson C, Li Z, Stewart S, Janciauskiene S, Kelley DG, Parmar J, Pitman R, Shapiro SD, Lomas DA. Polymers of Z α1-antitrypsin co-localize with neutrophils in emphysematous alveoli and are chemotactic in vivo. Am J Pathol 2005;166:377–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shapiro L, Pott GB, Ralston AH. Alpha-1-antitrypsin inhibits human immunodeficiency virus type 1. FASEB J 2001;15:115–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ikebe N, Akaike T, Miyamoto Y, Hayashida K, Yoshitake J, Ogawa M, Maeda H. Protective effect of S-nitrosylated alpha(1)-protease inhibitor on hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2000;295:904–911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Daemen MA, Heemskerk VH, van't VC, Denecker G, Wolfs TG, Vandenabeele P, Buurman WA. Functional protection by acute phase proteins alpha(1)-acid glycoprotein and alpha(1)-antitrypsin against ischemia/reperfusion injury by preventing apoptosis and inflammation. Circulation 2000;102:1420–1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Petrache I, Fijalkowska I, Zhen L, Medler TR, Brown E, Cruz P, Choe KH, Taraseviciene-Stewart L, Scerbavicius R, Shapiro L, et al. A novel anti-apoptotic role for alpha-1 antitrypsin in the prevention of pulmonary emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;173:1222–1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Petrache I, Fijalkowska I, Medler TR, Skirball J, Cruz P, Zhen L, Petrache HI, Flotte T, Tuder RM. Alpha-1 antitrypsin inhibits caspase-3 activity, preventing lung endothelial cell apoptosis. Am J Pathol (In press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Churg A, Dai J, Zay K, Karsan A, Hendricks R, Yee C, Martin R, MacKenzie R, Xie C, Zhang L, et al. Alpha-1-antitrypsin and a broad spectrum metalloprotease inhibitor, RS113456, have similar acute anti-inflammatory effects. Lab Invest 2001;81:1119–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lu Y, Tang M, Wasserfall C, Kou Z, Campbell-Thompson M, Gardemann T, Crawford J, Atkinson M, Song S. α(1)-Antitrypsin gene therapy modulates cellular immunity and efficiently prevents type 1 diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice. Hum Gene Ther 2006;17:625–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aoshiba K, Yokohori N, Nagai A. Alveolar wall apoptosis causes lung destruction and emphysematous changes. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2003;28:555–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cowan KN, Leung WCY, Mar C, Bhattacharjee R, Zhu YH, Rabinovitch M. Caspases from apoptotic myocytes degrade extracellular matrix: a novel remodeling paradigm. FASEB J 2005;19:U81–U91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shoshani T, Faerman A, Mett I, Zelin E, Tenne T, Gorodin S, Moshel Y, Elbaz S, Budanov A, Chajut A, et al. Identification of a novel hypoxia-inducible factor 1-responsive gene, RTP801, involved in apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol 2002;22:2283–2293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ellisen LW, Ramsayer KD, Johannessen CM, Yang A, Beppu H, Minda K, Oliner JD, McKeon F, Haber DA. REDD1, a developmentally regulated transcriptional target of p63 and p53, links p63 to regulation of reactive oxygen species. Mol Cell 2002;10:995–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brugarolas J, Lei K, Hurley RL, Manning BD, Reiling JH, Hafen E, Witters LA, Ellisen LW, Kaelin WG Jr. Regulation of mTOR function in response to hypoxia by REDD1 and the TSC1/TSC2 tumor suppressor complex. Genes Dev 2004;18:2893–2904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brugarolas JB, Vazquez F, Reddy A, Sellers WR, Kaelin WG Jr. TSC2 regulates VEGF through mTOR-dependent and -independent pathways. Cancer Cell 2003;4:147–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Petrache I, Natarajan V, Zhen L, Medler TR, Richter AT, Cho C, Hubbard WC, Berdyshev EV, Tuder RM. Ceramide upregulation causes pulmonary cell apoptosis and emphysema-like disease in mice. Nat Med 2005;11:491–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morla M, Busquets X, Pons J, Sauleda J, MacNee W, Agusti AG. Telomere shortening in smokers with and without COPD. Eur Respir J 2006;27:525–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tsuji T, Aoshiba K, Nagai A. Cigarette smoke induces senescence in alveolar epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2004;31:643–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]